An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Recent advances in understanding anorexia nervosa

Guido k.w. frank.

1 Department of Psychiatry, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, 80045, USA

2 Neuroscience Program, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, 80045, USA

Megan E. Shott

Marisa c. deguzman.

Anorexia nervosa is a complex psychiatric illness associated with food restriction and high mortality. Recent brain research in adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa has used larger sample sizes compared with earlier studies and tasks that test specific brain circuits. Those studies have produced more robust results and advanced our knowledge of underlying biological mechanisms that may contribute to the development and maintenance of anorexia nervosa. It is now recognized that malnutrition and dehydration lead to dynamic changes in brain structure across the brain, which normalize with weight restoration. Some structural alterations could be trait factors but require replication. Functional brain imaging and behavioral studies have implicated learning-related brain circuits that may contribute to food restriction in anorexia nervosa. Most notably, those circuits involve striatal, insular, and frontal cortical regions that drive learning from reward and punishment, as well as habit learning. Disturbances in those circuits may lead to a vicious cycle that hampers recovery. Other studies have started to explore the neurobiology of interoception or social interaction and whether the connectivity between brain regions is altered in anorexia nervosa. All together, these studies build upon earlier research that indicated neurotransmitter abnormalities in anorexia nervosa and help us develop models of a distinct neurobiology that underlies anorexia nervosa.

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is characterized by a persistent restriction of energy intake and leads to a body weight that is significantly lower than what is expected for height and age 1 . There is either an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat or persistent behavior that interferes with weight gain (even though at significantly low weight). Individuals with AN experience a disturbance in the way one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body shape and weight on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight. A restricting type has been distinguished from a binge eating/purging type; individuals in the latter group may intermittently have binge eating episodes or may use self-induced vomiting to avoid weight gain. AN shows a complex interplay between neurobiological, psychological, and environmental factors 2 and is a chronic disorder with frequent relapse, high treatment costs, and severe disease burden 3 , 4 . AN has a mortality rate 12 times higher than the death rate for all causes of death for females 15 to 24 years old 5 – 7 . Treatment success is modest, and no medication has been approved for AN treatment 8 .

Various psychological or psychodynamic theories have been developed in the past to explain the causes of AN but their underlying theories have been difficult to test 9 . On the contrary, neurobiological research using techniques such as human brain imaging leads to more directly testable hypotheses and holds promise to help us tease apart mechanisms that contribute to the onset of the illness, maintenance of AN behavior, and recovery from AN. This article will review recent advances in our understanding of the neurobiology of AN. Neurobiology is a branch of the life sciences, which deals with the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the nervous system 10 . Neurobiology is closely associated with the field of neuroscience, a branch of biology, which tries to understand brain function, from gross anatomy to neural circuits and cells that comprise them 11 . The goal of neurobiological research in AN is to develop a medical model perspective to reduce stigma and help develop better treatments 12 . At the earlier stages of brain research in AN, study samples tended to be quite small, which made replication difficult 13 . Most frequently, altered serotonin function was associated with AN and anxiety in the disorder 14 . More recent brain research has built upon those studies and increased sample sizes in structural studies and introduced studying brain function in relation to specific tasks that are thought be related to food restriction, anxiety, and body image distortion. Most studies have been carried out in adults, although there is a growing body of literature that investigated youth with AN.

The most frequently applied brain imaging study design in the past studied brain volume in AN, and more recent research now allows cortical thickness of the brain to be investigated. For a long time, there was the notion that gray matter volume and cortical thickness are lower in patients with AN (when ill and after recovery) than in controls. This research was pioneered by Katzman et al . in adolescents with AN 15 , 16 . However, recent research by Bernardoni et al . 17 and King et al . 18 in adolescents and young adults indicated that such abnormalities are rather short-lived and that both lower volume and cortical thickness normalize with weight recovery. Animal studies suggest that those changes may be due to the effects of malnutrition and dehydration on astrocytes within the brain connective tissue 19 . Two studies from our group have found larger orbitofrontal cortex and insula volume in adults and adolescents with AN after 1 to 2 weeks of normalization of food intake or in individuals after recovery, and orbitofrontal cortex volume was related to taste pleasantness 20 , 21 . Those results were intriguing as they implicated taste perception in relation to brain volume but they need replication. New data from our group in healthy first-degree relatives of patients with AN also show larger orbitofrontal cortex volume, supporting a trait abnormality (unpublished data). Studies by Bernardoni et al . in young adults have found abnormalities in gray matter gyrification in AN, and nutritional rehabilitation seems to normalize altered cortical folding 22 . A valuable lesson from those studies is that food intake can have dramatic effects on brain structure. Whether lower or higher brain volume in AN has implications on illness behavior or is instead an effect of malnutrition without effects on behavior is still unclear and needs further research 23 , 24 .

Functional brain imaging provides the opportunity to tie behavior to brain activation and thus to distinct brain neurobiology, which could become a treatment target. Several aspects of behavior in AN stand out. One is the ability to restrict food intake to the point of emaciation while the typical mechanisms to maintain a healthy body weight are inefficient. Another is how the body can maintain this behavior even when AN patients in therapy are trying to break that behavior pattern.

Relevant to food avoidance behavior is the brain reward system, which processes the motivation to eat and hedonic experience after food intake, and also calculates and updates how valuable a specific food is to us 25 . This circuitry includes the insula, which contains the primary taste cortex, the ventral striatum that comprises dopamine terminals to drive food approach, and the orbitofrontal cortex that calculates a value, while the hypothalamus integrates body signals on hunger and satiety for higher-order decision making and food approach. Many studies have used visual food cues but it has been difficult to draw conclusions on the pathophysiology of AN from those studies 26 .

Several studies from our group using sugar taste stimuli have found that brain activation in adolescent and adult AN was elevated compared with controls in response to unexpected receipt or omission of sweet taste in the insula and striatum 27 , 28 . This so-called “prediction error” response has been associated with brain dopamine circuitry and serves as a learning signal to drive approach or avoidance of salient stimuli in the environment in the future. In addition, orbitofrontal cortex prediction error response correlated positively with anxiety measures in AN 28 , 29 . We found a similar pattern of elevated brain activation in AN to unexpected receipt or omission of monetary stimuli, suggesting a food-independent alteration of brain dopamine circuitry. Importantly, those studies have also shown that brain response was predictive of weight gain during treatment and that brain dopamine function could have an important role in weight recovery in AN. This was supported by a retrospective chart review in adolescents with AN that suggested that the dopamine D 2 receptor partial agonist aripiprazole was associated with higher weight gain in a structured treatment program in comparison with patients not on that medication 30 . Mechanistically, it was hypothesized that dopamine D 2 receptor stimulation might be desensitizing those receptors and normalize behavior response. This, however, is speculative and controlled studies are lacking.

Other lines of research on the pathophysiology of AN are directed toward feedback learning, and several studies have found that AN is associated with alterations, behaviorally or in brain response. A study by Foerde and Steinglass, who investigated learning using a picture association task in patients with AN before and after weight restoration, indicated deficits in feedback learning and generalization of learned information in comparison with controls 31 . Such alterations could translate directly into difficulties in behavior modification toward recovery. Studies from Ehrlich’s group found normal feedback learning in ill, but reduced performance on reversal learning in recovered AN, which made the impact of learning in ill AN less clear 32 , 33 . Furthermore, Bernardoni et al ., using a different study design, found that individuals with AN had an increased learning rate and elevated medial frontal cortex response following punishment 34 . That result supports previous findings of elevated sensitivity to punishment in AN as a possible biological trait 35 . Another very interesting study by Foerde et al . tested brain response to food choice presenting images of food and that research implicated the dorsal striatum in this process in AN 36 . The authors also found that the strength of connectivity between striatum and frontal cortex activation correlated inversely with actual caloric food intake in a test meal after the brain scan. The authors interpreted the findings to mean that this frontostriatal involvement in AN could contribute to habit formation of food restriction behavior. Behavioral research has provided evidence that habit formation or habit strength could be necessary for the perpetuation of AN behaviors and this concept is important to study further 37 – 39 .

The self-perception of being fat despite being underweight is another aspect of AN that the field continues to struggle with in finding its underlying pathophysiology. Some studies have found a specific brain response related to altered processing of visual information or tasks that tested interoception. For instance, Kerr et al . 40 found elevated insula activation during an abdomen perception task, and Xu et al . 41 found that a frontal and cingulate cortex response during a social evaluation task correlated with body shape concerns. A study by Hagman et al ., however, indicated a strong cognitive and emotional influence on body image distortion, and the intersection between altered perception and fear-driven self-perception needs further study 42 . Social interaction and its brain biology constitute another area that was hypothesized to be related to AN behaviors and some research is emerging on this topic. For instance, a study by McAdams et al . showed that the quality of the social relationship or social reciprocity tested in a trust game showed lower occipito-parietal brain response in patients with AN in comparison with a control group 43 . This research suggests altered reward experience from interpersonal contact in AN, which could impact emotional well-being and interfere with recovery. Oxytocin, a peptide hormone related to social behavior, could play a role but this requires more detailed research 44 .

Studies on brain connectivity can test either what brain regions work in concert during a specific task (functional connectivity) or what the hierarchical organization is between areas in the brain (that is, what region drives another) (effective connectivity). Several studies in the past have shown that resting-state functional connectivity is altered in patients with AN compared with control groups. Those studies repeatedly found altered connectivity that involved the insula, a region associated with taste perception, prediction error processing, and integration of body perception, as reviewed by Gaudio et al . 45 . More recent studies found higher or lower resting-state activation in AN across various networks and during rest or task conditions 39 , 46 – 49 . Longitudinal studies will need to test what might be the best resting-state network to focus on to predict, for instance, illness outcome or whether functional connectivity during specific tasks such as taste processing could be more informative. One study by Boehm et al . found normalization of functional connectivity in the default mode but continued abnormal frontoparietal network connectivity in recovered AN 50 . It remains to be seen whether functional connectivity will normalize with recovery or can identify long-lasting or maybe trait alterations.

Effective connectivity studies indicated that while viewing fearful faces, a group with AN had deficits of brain connectivity between prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, which correlated with measures for anxiety and eating behaviors in a study by Rangaprakash et al . 51 . Studies from our group that assessed effective connectivity during the tasting of sucrose solution found that, whereas in controls the hypothalamus drove ventral striatum response, in patients with AN, effective connectivity was directed from the ventral striatum to the hypothalamus 28 , 52 . Previously, a dopamine-dependent pathway from the ventral striatum to the hypothalamus that mediates fear was described and we hypothesized that this circuitry might be activated in AN to override appetitive hypothalamic signals 53 .

In summary, brain research has started to make inroads into the pathophysiology of AN. We have learned that malnutrition has significant effects on brain structure, changes that can recover with weight restoration, but whether those alterations have an impact on illness behavior remains unclear 23 . Research into the function of brain circuits has implicated reward pathways and malnutrition-driven alterations of dopamine responsiveness together with neuroendocrine changes, and high anxiety may interfere with normal mechanisms that drive eating behavior 54 . Habit learning and associated striatal-frontal brain connectivity could provide another mechanism of how brain function and interaction of cortical and sub-cortical regions may perpetuate illness behavior that is difficult to overcome. Those advances are promising to establish that AN is associated with a distinct brain pathophysiology. This will help researchers develop effective biological treatments that improve recovery and help prevent relapse. A significant challenge to overcome will be to integrate the differing brain research studies and develop a unified model 13 . Critical in this effort will be well-powered and comparable study designs across research groups, which take into account confounding factors such as comorbidity and medication use and which use rigorous standards for data analysis.

[version 1; peer review: 2 approved]

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants MH096777 and MH103436 (both to GKWF) and by T32HD041697 (University of Colorado Neuroscience Program) and National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Colorado Clinical and Translational Science Awards grant TL1 TR001081 (both to MCD).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

- Carrie J McAdams , Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas at Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA No competing interests were disclosed.

- Janet Treasure , Section of Eating Disorders, Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College London, London, UK No competing interests were disclosed.

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Eating Disorders: Current Knowledge and Treatment Update

- B. Timothy Walsh , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

Although relatively uncommon, eating disorders remain an important concern for clinicians and researchers as well as the general public, as highlighted by the recent depiction of Princess Diana’s struggles with bulimia in “The Crown.” This brief review will examine recent findings regarding the diagnosis, epidemiology, neurobiology, and treatment of eating disorders.

Eight years ago, DSM-5 made major changes to the diagnostic criteria for eating disorders. A major problem in DSM-IV ’s criteria was that only two eating disorders, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, were officially recognized. Therefore, many patients presenting for treatment received the nonspecific diagnostic label of eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS), which provided little information about the nature of the patient’s difficulties. This problem was addressed in several ways in DSM-5 (see DSM-5 Feeding and Eating Disorder list). The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were slightly expanded to capture a few more patients in each category. But two other changes had a greater impact in reducing the use of nonspecific diagnoses.

The first of these was the addition of binge eating disorder (BED), which had previously been described in an appendix of DSM-IV . BED is the most common eating disorder in the United States, so its official recognition in DSM-5 led to a substantial reduction in the need for nonspecific diagnoses.

DSM-5 Feeding and Eating Disorder

Rumination Disorder

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder

Anorexia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa

Binge-eating disorder

Other specified feeding or eating disorder

Unspecified feeding or eating disorder

The second important change was the combination of the DSM-IV section titled “Feeding and Eating Disorders of Infancy or Early Childhood” with “Eating Disorders” to form an expanded section, “Feeding and Eating Disorders.” This change thereby included three diagnostic categories: pica, rumination disorder, and feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood. Pica and rumination disorder are infrequently diagnosed.

The other category, feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood, was rarely used and had been the subject of virtually no research since its inclusion in DSM-IV . The Eating Disorders Work Group responsible for reviewing the criteria for eating disorders for DSM-5 realized that there was a substantial number of individuals, many of them children, who severely restricted their food intake but did not have anorexia nervosa. For example, after a severe bout of vomiting after eating, some individuals attempt to prevent a recurrence by no longer eating at all, leading to potentially serious nutritional disturbances. No diagnostic category in DSM-IV existed for such individuals. Therefore, the DSM-IV category, feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood, was expanded and retitled “avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder” (ARFID). Combined, these changes led to a substantial reduction in the need for nonspecific diagnostic categories for eating disorders.

In the course of assessing the impact of the recommended changes in the diagnostic criteria for eating disorders, the Eating Disorders Work Group became aware of another group of individuals presenting for clinical care whose symptoms did not quite fit any of the existing or proposed categories. These were individuals, many of them previously overweight or obese, who had lost a substantial amount of weight and developed many of the signs and symptoms characteristic of anorexia nervosa. However, at the time of presentation, their weights remained within or above the normal range, therefore not satisfying the first diagnostic criterion for anorexia nervosa. The work group recommended that a brief description of such individuals be included in the DSM-5 diagnostic category that replaced DSM-IV ’s EDNOS: “other specified feeding and eating disorders” (OSFED); this description was labeled atypical anorexia nervosa. The degree to which the symptoms, complications, and course of individuals with atypical anorexia nervosa resemble and differ from those of individuals with typical anorexia nervosa remains an important focus of current research.

Epidemiology

Although eating disorders contribute significantly to the global burden of disease, they remain relatively uncommon. A study published in September 2018 by Tomoko Udo, Ph.D., and Carlos M. Grilo, Ph.D., in Biological Psychiatry examined data from a large, nationally representative sample of over 36,000 U.S. adults 18 years of age and older surveyed using a lay-administered diagnostic interview in 2012-2013. The 12-month prevalence estimates for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and BED were 0.05%, 0.14%, and 0.44%, respectively. Although the relative frequencies of these disorders were similar to those described in prior studies, the absolute estimates were somewhat lower for unclear reasons. Consistent with clinical experience and prior reports, the eating disorders, especially anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, were more prevalent among women (though men are also affected). Although eating disorders occurred across all ethnic and racial groups, there were fewer cases of anorexia nervosa among non-Hispanic and Hispanic Black respondents than among non-Hispanic White respondents. Consistent with long-standing clinical impression, individuals with lifetime anorexia nervosa reported higher incomes.

Finally, when BED was under consideration for official recognition in DSM-5 , some critics suggested that, since virtually everyone occasionally overeats, BED was an example of the misguided tendency of DSM to pathologize normal behavior. The low prevalence of BED reported in the study by Udo and Grilo documents that, when carefully assessed, BED affects only a minority of individuals and is therefore distinct from normality.

A subject of some debate and substantial uncertainty is whether the incidence of eating disorders (the number of new cases a year) is increasing. Some studies, such as that of Udo and Grilo, have found that the lifetime rates of eating disorders among older individuals are lower than those among younger individuals, suggesting that the frequency of eating disorders may be increasing. However, this might also reflect more recent awareness and knowledge of eating disorders. Other studies that conducted multiple examinations of the frequency of eating disorders in the same settings over time appear to suggest that, in the last several decades, the incidence of anorexia nervosa has remained roughly stable, whereas the incidence of bulimia nervosa has decreased. Presumably, this reflects changes in the sociocultural environment such as an increased acceptance of being overweight and reduced pressure to engage in inappropriate compensatory measures such as self-induced vomiting after binge eating.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted virtually every facet of life across the world and has produced severe financial, medical, and psychological stresses. Preliminary research suggests that such stresses have exacerbated the symptoms of individuals with preexisting eating disorders and have led to increased binge eating in the general population. Hopefully, these trends will improve with successful control of the pandemic.

Neurobiology

Much recent research on the mechanisms underlying the development and persistence of eating disorders has focused on the processing of rewarding and nonrewarding/punishing stimuli. Several studies have suggested that individuals with anorexia nervosa are less able to distinguish among stimuli with varying probabilities of obtaining a reward. Other studies suggest that, when viewing images of food during MRI scanning, individuals with anorexia nervosa tend to show less activation of brain reward areas than do controls. Such deficits may be related to disturbances in dopamine function in areas of the brain known to be involved in reward processing. Research based on emerging methods in computational psychiatry suggests that individuals with anorexia nervosa may be particularly sensitive to learning from punishment; for example, they may be very quick to learn what stimuli lead to a decrease in the amount of a reward. Conceivably, they may learn that eating high-fat foods prevents weight loss and produces undesirable weight gain, and they begin to avoid such foods. These studies, and a range of others, focus on probing basic brain mechanisms and how they may be disrupted in anorexia nervosa. A challenge for this “bottom-up” approach is to determine how exactly disturbances in such mechanisms are related to the eating disturbances characteristic of anorexia nervosa.

Other recent studies take a “top-down” approach, focusing on the neural circuitry underlying the persistent maladaptive choices made by individuals with anorexia nervosa when they decide what foods to eat. Such research successfully captures the well-established avoidance of high-fat foods by individuals with anorexia nervosa and has documented that such individuals utilize different neural circuits in making decisions about what to eat than do healthy individuals. These results are consistent with suggestions that the impressive persistence of anorexia nervosa in many individuals may be due to the establishment of automatic, stereotyped, and habitual behavior surrounding food choice. A challenge for such top-down research strategies is to determine how these maladaptive patterns develop so rapidly and become so ingrained.

Research on the neurobiology underlying bulimia nervosa is broadly similar. Although the results are complex, individuals with bulimia nervosa appear to find food stimuli more rewarding, and there are indications of disturbances in reward responsiveness to sweet tastes. Several studies have documented impairments in impulse control assessed using behavioral paradigms such as the Stroop Task. In this task, individuals are presented with a word naming a color (for example, “red”) but asked to name the color of the letters spelling the word (for example, the letters r, e, and d are green). Increased difficulties in performing such tasks have been described in individuals with bulimia nervosa and linked to reduced prefrontal cortical thickness.

It has long been known that eating disorders tend to run in families, and there has been strong evidence that this in part reflects the genes that individuals inherit from their parents. In recent decades, it has become clear that the risk of developing most complex human diseases, including obesity, hypertension, and eating disorders is related to many genes, each one of which contributes a small amount to the risk. Because the contribution of a single gene is so small, the DNA from a very large number of individuals with and without the disorder needs to be examined. For instance, genomewide association studies (GWAS) in schizophrenia have examined tens of thousands of individuals with schizophrenia and over 100,000 controls and identified well over 100 genetic loci that contribute to the risk of developing schizophrenia.

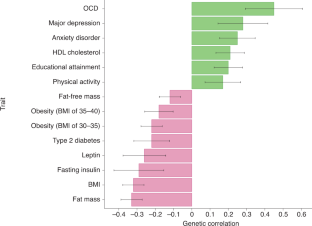

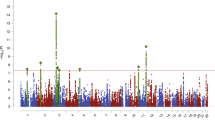

GWAS examining the genetic risk for eating disorders are under way but to date have focused primarily on anorexia nervosa. The Psychiatric Genetics Consortium has collected information from 10,000 to 20,000 individuals with anorexia nervosa and over 50,000 controls and has, so far, identified eight loci that contribute to the genetic risk for this disorder. In addition, this work has identified genetic correlations between anorexia nervosa and a range of other disorders known to be comorbid with anorexia nervosa such as anxiety disorders as well as a negative genetic correlation with obesity. These data suggest that the genetic risk for anorexia nervosa is based on a complex interplay between loci associated with a range of psychological and metabolic/anthropometric traits.

Although there have been no dramatic developments in our knowledge of how best to treat individuals with eating disorders, there have been some significant and useful advances in recent years.

For anorexia nervosa, arguably the most significant advance in treatment in the last quarter century has been family-based treatment for adolescents. In this approach, sometimes referred to as the “Maudsley method,” the family, guided by the therapist, becomes the primary agent of change and responsible for ensuring that eating behavior normalizes and weight increases. This approach differs markedly from prior treatment strategies that assumed parental involvement was not helpful or even detrimental. Family-based treatment is now widely viewed as a treatment of first choice for adolescents with anorexia nervosa and has also been adapted to treat bulimia nervosa.

Family-based treatment can be quite challenging for parents. The entire family is asked to attend treatment sessions, and one session early in treatment includes a family meal during which the parents are charged with the difficult task of persuading the adolescent to consume more food than he/she had intended. An alternative but related model, termed “parent-focused treatment,” has recently been explored in a few studies. In this approach, parents meet with a therapist without the affected adolescent or other members of the family and receive guidance regarding how to help the adolescent to alter his or her behavior following techniques virtually identical to those provided in traditional family-based treatment. Several small studies have examined this approach, and results suggest similar effectiveness. Although more research is needed, these findings suggest that parent-focused treatment may be an attractive alternative to family-based treatment for many parents and practitioners.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a dramatic acceleration in the provision of psychiatric care remotely, including family-based treatment. Work on providing family-based treatment via videoconference had begun prior to the arrival of COVID-19, as this specialized form of care is not widely available, and its provision via HIPAA-compliant video links would offer a substantial increase in accessibility. Several small studies suggested that remote provision of family-based treatment is feasible and likely to be efficacious. The restrictions imposed by COVID-19 on face-to-face contact have accelerated the remote delivery of family-based treatment; hopefully, new research will document its effectiveness. It should be noted, however, that, in most cases, local contact with a medical professional who can directly measure weight and oversee the patient’s physical state is required.

The treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa, who typically developed the disorder as teenagers and have been ill for five or more years, remains challenging. Structured behavioral interventions, such as those available in specialized inpatient, day program, or residential centers, typically lead to significant weight restoration and psychological and physiological improvement. However, the rate of relapse following acute care remains substantial. Furthermore, most adult patients with anorexia nervosa are very reluctant to accept treatment in such structured programs. A recent helpful development is evidence that olanzapine, at a dose of 5 mg/day to 10 mg/day, assists modestly with weight gain in adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa and is associated with few significant side effects. Unfortunately, it does not address core psychological symptoms and must be viewed as adjunctive to standard care.

There have been fewer recent developments in the treatment of patients with bulimia nervosa and of BED. For bulimia nervosa, cognitive-behavioral therapy remains the mainstay psychological treatment, and SSRIs continue to be the first-choice class of medication. For BED, multiple forms of psychological treatment are associated with substantial improvement in binge eating, and, in 2015, the FDA approved the use of the stimulant lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) for individuals with BED. Unlike most psychological treatments, lisdexamfetamine is associated with modest weight loss but has effects on pulse and blood pressure that may be of concern, especially for older individuals.

Also noteworthy are the development and application of new forms of psychological treatment for individuals with eating disorders. These include dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT). Although only a few controlled studies have examined the effectiveness of these treatments, anecdotal information and the results of these studies suggest that such methods may be useful alternatives to more established interventions.

Conclusions

Eating disorders remain uncommon but clinically important problems characterized by persistent disturbances in eating or eating-related behavior. Cutting-edge research focuses on neurobiology and genetics, utilizing novel and rapidly evolving methodology. There have been modest advances in treatment approaches, including the COVID-19 pandemic’s acceleration of treatment delivery via video-link. Future studies will hopefully clarify the nature of ARFID and of atypical anorexia nervosa and lead to the development of more effective interventions, especially for individuals with long-standing eating disorders. ■

Additional Resources

Walsh BT. Diagnostic Categories for Eating Disorders: Current Status and What Lies Ahead. Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2019; 42(1):1-10.

Udo T, Grilo CM. Prevalence and Correlates of DSM-5 -Defined Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Biol Psychiatry . 2018; 84(5):345-354.

Van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Review of the Burden of Eating Disorders: Mortality, Disability, Costs, Quality of Life, and Family Burden. Curr Opin Psychiatry . 2020; 33(6):521-527.

Bernardoni F, Geisler D, King JA, et al. Altered Medial Frontal Feedback Learning Signals in Anorexia Nervosa. Biol Psychiatry . 2018; 83(3):235-243.

Frank GKW, Shott ME, DeGuzman MC. The Neurobiology of Eating Disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am . 2019; 28(4):629-640.

Steinglass JE, Berner LA, Attia E. Cognitive Neuroscience of Eating Disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2019; 42(1):75-91.

Bulik CM, Blake L, Austin J. Genetics of Eating Disorders: What the Clinician Needs to Know. Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2019; 42(1):59-73.

Attia E, Steinglass JE, Walsh BT, et al. Olanzapine Versus Placebo in Adult Outpatients With Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Psychiatry . 2019; 176(6):449-456.

Le Grange D, Hughes EK, Court A, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Parent-Focused Treatment and Family-Based Treatment for Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2016; 55(8):683-92.

Pisetsky EM, Schaefer LM, Wonderlich SA, et al. Emerging Psychological Treatments in Eating Disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2019; 42:219-229.

B. Timothy Walsh, M.D., is a professor of psychiatry at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center and the founding director of the Columbia Center for Eating Disorders at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. He is the co-editor of the Handbook of Assessment and Treatment of Eating Disorders from APA Publishing.

Dr. Walsh reports receiving royalties or honoraria from UpToDate, McGraw-Hill, the Oxford University Press, the British Medical Journal, the Johns Hopkins Press, and Guidepoint Global

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 06 May 2022

Genetics and neurobiology of eating disorders

- Cynthia M. Bulik ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7772-3264 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Jonathan R. I. Coleman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6759-0944 4 , 5 ,

- J. Andrew Hardaway 6 ,

- Lauren Breithaupt 7 , 8 ,

- Hunna J. Watson 1 , 9 , 10 ,

- Camron D. Bryant ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4505-5809 11 &

- Gerome Breen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2053-1792 4 , 5

Nature Neuroscience volume 25 , pages 543–554 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

9649 Accesses

27 Citations

56 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Feeding behaviour

- Psychiatric disorders

Eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder) are a heterogeneous class of complex illnesses marked by weight and appetite dysregulation coupled with distinctive behavioral and psychological features. Our understanding of their genetics and neurobiology is evolving thanks to global cooperation on genome-wide association studies, neuroimaging, and animal models. Until now, however, these approaches have advanced the field in parallel, with inadequate cross-talk. This review covers overlapping advances in these key domains and encourages greater integration of hypotheses and findings to create a more unified science of eating disorders. We highlight ongoing and future work designed to identify implicated biological pathways that will inform staging models based on biology as well as targeted prevention and tailored intervention, and will galvanize interest in the development of pharmacologic agents that target the core biology of the illnesses, for which we currently have few effective pharmacotherapeutics.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

What next for eating disorder genetics? Replacing myths with facts to sharpen our understanding

Laura M. Huckins, Rebecca Signer, … Cynthia M. Bulik

Assessing a multivariate model of brain-mediated genetic influences on disordered eating in the ABCD cohort

Margaret L. Westwater, Travis T. Mallard, … Monique Ernst

Genome-wide association study identifies eight risk loci and implicates metabo-psychiatric origins for anorexia nervosa

Hunna J. Watson, Zeynep Yilmaz, … Cynthia M. Bulik

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edn) (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

Erskine, H. E., Whiteford, H. A. & Pike, K. M. The global burden of eating disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 29 , 346–353 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Santomauro, D. F. et al. The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 320–328 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schaumberg, K. et al. Patterns of diagnostic flux in eating disorders: a longitudinal population study in Sweden. Psychol. Med. 49 , 432–450 (2019).

Article Google Scholar

Southern, J. et al. Multi-scale computational modelling in biology and physiology. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 96 , 60–89 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Yilmaz, Z., Hardaway, J. & Bulik, C. Genetics and epigenetics of eating disorders. Adv. Genomics Genet. 5 , 131–150 (2015).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dellava, J. E., Thornton, L. M., Lichtenstein, P., Pedersen, N. L. & Bulik, C. M. Impact of broadening definitions of anorexia nervosa on sample characteristics. J. Psychiatr. Res. 45 , 691–698 (2011).

Watson, H. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight risk loci and implicates metabo-psychiatric origins for anorexia nervosa. Nat. Genet. 51 , 1207–1214 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Duncan, L. et al. Significant locus and metabolic genetic correlations revealed in genome-wide association study of anorexia nervosa. Am. J. Psychiatry 174 , 850–858 (2017).

Thornton, L. et al. The Anorexia Nervosa Genetics Initiative: overview and methods. Contemp. Clin. Trials 74 , 61–69 (2018).

Song, W., Wang, W., Yu, S. & Lin, G. N. Dissection of the genetic association between anorexia nervosa and obsessive–compulsive disorder at the network and cellular levels. Genes 12 , 491 (2021).

Munn-Chernoff, M. A. et al. Shared genetic risk between eating disorder- and substance-use-related phenotypes: evidence from genome-wide association studies. Addict. Biol. 26 , e12880 (2021).

Kaye, W. et al. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am. J. Psychiatry 161 , 2215–2221 (2004).

Cederlöf, M. et al. Etiological overlap between obsessive–compulsive disorder and anorexia nervosa: a longitudinal cohort, family and twin study. World Psychiatry 14 , 333–338 (2015).

Thornton, L. M., Welch, E., Munn-Chernoff, M. A., Lichtenstein, P. & Bulik, C. M. Anorexia nervosa, major depression, and suicide attempts: shared genetic factors. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 46 , 525–534 (2016).

Dellava, J., Kendler, K. & Neale, M. Generalized anxiety disorder and anorexia nervosa: evidence of shared genetic variation. Depress. Anxiety 28 , 728–733 (2011).

Bulik-Sullivan, B. et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat. Genet. 47 , 1236–1241 (2015).

Watson, H. J. et al. Common genetic variation and age at onset of anorexia nervosa. Biol. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.09.001 (2021).

Solmi, F., Mascarell, M. C., Zammit, S., Kirkbride, J. B. & Lewis, G. Polygenic risk for schizophrenia, disordered eating behaviours and body mass index in adolescents. Br. J. Psychiatry 215 , 428–433 (2019).

Yilmaz, Z., Gottfredson, N., Zerwas, S., Bulik, C. & Micali, N. Developmental premorbid body mass index trajectories of adolescents with eating disorders in a longitudinal population cohort. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 58 , 191–199 (2019).

Abdulkadir, M. et al. Polygenic score for body mass index is associated with disordered eating in a general population cohort. J. Clin. Med. 9 , 1187 (2020).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hübel, C. et al. One size does not fit all. Genomics differentiates among anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54 , 785–793 (2021).

Murray, G. K. et al. Could polygenic risk scores be useful in psychiatry?: a review. JAMA Psychiatry 78 , 210–219 (2020).

Wray, N. et al. Research review: polygenic methods and their application to psychiatric traits. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 55 , 1068–1087 (2014).

Lee, P. H. et al. Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell 179 , 1469–1482 (2019).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Lee, J. E., Namkoong, K. & Jung, Y.-C. Impaired prefrontal cognitive control over interference by food images in binge-eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. Neurosci. Lett. 651 , 95–101 (2017).

Yilmaz, Z. et al. Examination of the shared genetic basis of anorexia nervosa and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 25 , 2036–2046 (2020).

Reed, Z. E., Micali, N., Bulik, C. M., Davey Smith, G. & Wade, K. H. Assessing the causal role of adiposity on disordered eating in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood: a Mendelian randomization analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 106 , 764–772 (2017).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tyrrell, J. et al. Genetic evidence for causal relationships between maternal obesity-related traits and birth weight. JAMA 315 , 1129–1140 (2016).

Adams, D. M., Reay, W. R., Geaghan, M. P. & Cairns, M. J. Investigating the effect of glycaemic traits on the risk of psychiatric illness using Mendelian randomisation. Neuropsychopharmacology 46 , 1093–1102 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Huckins, L. M. et al. Investigation of common, low-frequency and rare genome-wide variation in anorexia nervosa. Mol. Psychiatry 23 , 1169–1180 (2018).

PubMed Google Scholar

Scott-Van Zeeland, A. A. et al. Evidence for the role of EPHX2 gene variants in anorexia nervosa. Mol. Psychiatry 19 , 724–732 (2013).

Lutter, M. et al. Novel and ultra-rare damaging variants in neuropeptide signaling are associated with disordered eating behaviors. PLoS ONE 12 , e0181556 (2017).

Cui, H. et al. Eating disorder predisposition is associated with ESRRA and HDAC4 mutations. J. Clin. Invest. 123 , 4706–4713 (2013).

Lombardi, L. et al. Anorexia nervosa is associated with Neuronatin variants. Psychiatr. Genet. 29 , 103–110 (2019).

Wang, K. et al. A genome-wide association study on common SNPs and rare CNVs in anorexia nervosa. Mol. Psychiatry 16 , 949–959 (2011).

Yilmaz, Z. et al. Exploration of large, rare CNVs associated with psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders in individuals with anorexia nervosa. Psychiatr. Genet 27 , 152–158 (2017).

Boraska, V. et al. A genome-wide association study of anorexia nervosa. Mol. Psychiatry 19 , 1085–1094 (2014).

Chang, X. et al. Microduplications at the 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 locus are enriched in patients with anorexia nervosa. J. Psychiatr. Res. 113 , 34–38 (2019).

Bulik, C. M. et al. The Eating Disorders Genetics Initiative (EDGI): study protocol. BMC Psychiatry 21 , 234 (2021).

Co, M., Anderson, A. G. & Konopka, G. FOXP transcription factors in vertebrate brain development, function, and disorders. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 9 , e375 (2020).

Yengo, L. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in ∼ 700,000 individuals of European ancestry. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27 , 3641–3649 (2018).

Zhang, M. et al. Axonogenesis is coordinated by neuron-specific alternative splicing programming and splicing regulator PTBP2. Neuron 101 , 690–706 (2019).

Arends, R. M. et al. Associations between the CADM2 gene, substance use, risky sexual behavior and self-control: a phenome-wide association study. Addict. Biol. 26 , e13015 (2021).

Rathjen, T. et al. Regulation of body weight and energy homeostasis by neuronal cell adhesion molecule 1. Nat. Neurosci. 20 , 1096–1103 (2017).

Gerson, S. L. MGMT: its role in cancer aetiology and cancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4 , 296–307 (2004).

Reid, D. A. et al. Incorporation of a nucleoside analog maps genome repair sites in postmitotic human neurons. Science 372 , 91–94 (2021).

Wu, W. et al. Neuronal enhancers are hotspots for DNA single-strand break repair. Nature 593 , 440–444 (2021).

Finucane, H. et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat. Genet. 47 , 1228–1235 (2015).

Skene, N. G. et al. Genetic identification of brain cell types underlying schizophrenia. Nat. Genet. 50 , 825–833 (2018).

Chowdhury, T. G. et al. Voluntary wheel running exercise evoked by food-restriction stress exacerbates weight loss of adolescent female rats but also promotes resilience by enhancing GABAergic inhibition of pyramidal neurons in the dorsal hippocampus. Cereb. Cortex 29 , 4035–4049 (2019).

Klenowski, P. M. et al. Prolonged consumption of sucrose in a binge-like manner, alters the morphology of medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens shell. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10 , 54 (2016).

Wang, D. et al. Comprehensive functional genomic resource and integrative model for the human brain. Science 362 , eaat8464 (2018).

Rossi, M. A. & Stuber, G. D. Overlapping brain circuits for homeostatic and hedonic feeding. Cell Metab. 27 , 42–56 (2018).

Frank, G. K., Shott, M. E. & DeGuzman, M. C. Recent advances in understanding anorexia nervosa. F1000Res. 8 , 504 (2019).

Kaye, W. H., Wagner, A., Fudge, J. L. & Paulus, M. Neurocircuity of eating disorders. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 6 , 37–57 (2010).

Lammel, S., Lim, B. K. & Malenka, R. C. Reward and aversion in a heterogeneous midbrain dopamine system. Neuropharmacol 76 , 351–359 (2014).

Cowdrey, F. A., Park, R. J., Harmer, C. J. & McCabe, C. Increased neural processing of rewarding and aversive food stimuli in recovered anorexia nervosa. Biol. Psychiatry 70 , 736–743 (2011).

Kaye, W. H. et al. Neural insensitivity to the effects of hunger in women remitted from anorexia nervosa. Am. J. Psychiatry 177 , 601–610 (2020).

Bohon, C. & Stice, E. Reward abnormalities among women with full and subthreshold bulimia nervosa: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 44 , 585–595 (2011).

Simon, J. J. et al. Neural signature of food reward processing in bulimic-type eating disorders. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 11 , 1393–1401 (2016).

Bailer, U. F. et al. Exaggerated 5-HT 1A but normal 5-HT 2 A receptor activity in individuals ill with anorexia nervosa. Biol. Psychiatry 61 , 1090–1099 (2007).

Broft, A. et al. Striatal dopamine type 2 receptor availability in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 233 , 380–387 (2015).

Bailer, U. F. et al. Amphetamine induced dopamine release increases anxiety in individuals recovered from anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 45 , 263–271 (2012).

Broft, A. et al. Striatal dopamine in bulimia nervosa: a PET imaging study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 45 , 648–656 (2012).

Mihov, Y. et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in bulimia nervosa. Sci. Rep. 10 , 1–10 (2020).

Frank, G. K., Shott, M. E., Hagman, J. O. & Mittal, V. A. Alterations in brain structures related to taste reward circuitry in ill and recovered anorexia nervosa and in bulimia nervosa. Am. J. Psychiatry 170 , 1152–1160 (2013).

Craig, A. D. & Craig, A. How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10 , 59–70 (2009).

Kerr, K. L. et al. Altered insula activity during visceral interoception in weight-restored patients with anorexia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology 41 , 521–528 (2016).

Zucker, N. L. et al. The clinical significance of posterior insular volume in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Psychosom. Med. 79 , 1025–1035 (2017).

Berner, L. A. et al. Altered anticipation and processing of aversive interoceptive experience among women remitted from bulimia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology 44 , 1265–1273 (2019).

Ting, J. T. & Feng, G. Neurobiology of obsessive–compulsive disorder: insights into neural circuitry dysfunction through mouse genetics. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 21 , 842–848 (2011).

Marsh, R. et al. An fMRI study of self-regulatory control and conflict resolution in adolescents with bulimia nervosa. Am. J. Psychiatry 168 , 1210–1220 (2011).

Skunde, M. et al. Neural signature of behavioural inhibition in women with bulimia nervosa. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 41 , E69–E78 (2016).

Wierenga, C. et al. Altered BOLD response during inhibitory and error processing in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. PLoS ONE 9 , e92017 (2014).

Oberndorfer, T. A., Kaye, W. H., Simmons, A. N., Strigo, I. A. & Matthews, S. C. Demand‐specific alteration of medial prefrontal cortex response during an inhibition task in recovered anorexic women. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 44 , 1–8 (2011).

Finch, J. E., Palumbo, I. M., Tobin, K. E. & Latzman, R. D. Structural brain correlates of eating pathology symptom dimensions: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 317 , 111379 (2021).

Geisler, D. et al. Altered white matter connectivity in young acutely underweight patients with anorexia nervosa. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 61 , 331–340 (2022).

Goodkind, M. et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry 72 , 305–315 (2015).

McTeague, L. M. et al. Identification of common neural circuit disruptions in emotional processing across psychiatric disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 177 , 411–421 (2020).

Shanmugan, S. et al. Common and dissociable mechanisms of executive system dysfunction across psychiatric disorders in youth. Am. J. Psychiatry 173 , 517–526 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. Neurobiological commonalities and distinctions among 3 major psychiatric disorders: a graph theoretical analysis of the structural connectome. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 45 , 15–22 (2020).

Xia, M. et al. Shared and distinct functional architectures of brain networks across psychiatric disorders. Schizophr Bull. 45 , 450–463 (2019).

Hudson, J. I., Hiripi, E., Pope, H. G. Jr. & Kessler, R. C. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol. Psychiatry 61 , 348–358 (2007).

Frank, G. K., Favaro, A., Marsh, R., Ehrlich, S. & Lawson, E. A. Toward valid and reliable brain imaging results in eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 51 , 250–261 (2018).

Kaufmann, L.-K. et al. Fornix under water? Ventricular enlargement biases forniceal diffusion magnetic resonance imaging indices in anorexia nervosa. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2 , 430–437 (2017).

Gaudio, S., Carducci, F., Piervincenzi, C., Olivo, G. & Schiöth, H. B. Altered thalamo–cortical and occipital–parietal–temporal–frontal white matter connections in patients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa: a systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 44 , 324–339 (2019).

Thompson, P. M. et al. ENIGMA and global neuroscience: a decade of large-scale studies of the brain in health and disease across more than 40 countries. Transl. Psychiatry 10 , 100 (2020).

Gelegen, C. et al. Difference in susceptibility to activity-based anorexia in two inbred strains of mice. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 17 , 199–205 (2007).

Gelegen, C. et al. Chromosomal mapping of excessive physical activity in mice in response to a restricted feeding schedule. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 20 , 317–326 (2010).

Pjetri, E. et al. Identifying predictors of activity based anorexia susceptibility in diverse genetic rodent populations. PLoS ONE 7 , e50453 (2012).

Babbs, R. K. et al. Genetic differences in the behavioral organization of binge eating, conditioned food reward, and compulsive-like eating in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J strains. Physiol. Behav. 197 , 51–66 (2018).

Newmyer, B. A., Whindleton, C. M., Srinivasa, N., Jones, M. K. & Scott, M. M. Genetic variation affects binge feeding behavior in female inbred mouse strains. Sci. Rep. 9 , 1–10 (2019).

Kirkpatrick, S. L. et al. Cytoplasmic FMR1-interacting protein 2 is a major genetic factor underlying binge eating. Biol. Psychiatry 81 , 757–769 (2017).

Babbs, R. K. et al. Cyfip1 haploinsufficiency increases compulsive-like behavior and modulates palatable food intake in mice: dependence on Cyfip2 genetic background, parent of origin and sex. G3 9 , 3009–3022 (2019).

Farrell, M. et al. Treatment-resistant psychotic symptoms and the 15q11.2 BP1–BP2 (Burnside–Butler) deletion syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Transl. Psychiatry 10 , 1–8 (2020).

Yao, E. J. et al. Systems genetic analysis of binge-like eating in a C57BL/6J × DBA/2J-F2 cross. Genes Brain Behav. e12751 (2021).

Nobis, S. et al. Alterations of proteome, mitochondrial dynamic and autophagy in the hypothalamus during activity-based anorexia. Sci. Rep. 8 , 1–15 (2018).

Nobis, S. et al. Colonic mucosal proteome signature reveals reduced energy metabolism and protein synthesis but activated autophagy during anorexia‐induced malnutrition in mice. Proteomics 18 , 1700395 (2018).

Breton, J. et al. Proteome modifications of gut microbiota in mice with activity-based anorexia and starvation: role in ATP production. Nutrition 67 , 110557 (2019).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Schroeder, M. et al. Placental miR-340 mediates vulnerability to activity based anorexia in mice. Nat. Commun. 9 , 1–15 (2018).

He, X., Stefan, M., Terranova, K., Steinglass, J. & Marsh, R. Altered white matter microstructure in adolescents and adults with bulimia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology 41 , 1841–1848 (2015).

Kaakoush, N. O. et al. Alternating or continuous exposure to cafeteria diet leads to similar shifts in gut microbiota compared to chow diet. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 61 , 1500815 (2017).

Sweeney, P. & Yang, Y. Neural circuit mechanisms underlying emotional regulation of homeostatic feeding. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 28 , 437–448 (2017).

Webber, E. S., Bonci, A. & Krashes, M. J. The elegance of energy balance: insight from circuit‐level manipulations. Synapse 69 , 461–474 (2015).

Andermann, M. L. & Lowell, B. B. Toward a wiring diagram understanding of appetite control. Neuron 95 , 757–778 (2017).

Welch, A. C. et al. Dopamine D2 receptor overexpression in the nucleus accumbens core induces robust weight loss during scheduled fasting selectively in female mice. Mol. Psychiatry 26 , 3765–3777 (2019).

Milton, L. K. et al. Suppression of corticostriatal circuit activity improves cognitive flexibility and prevents body weight loss in activity-based anorexia in rats. Biol. Psychiatry 90 , 819–828 (2021).

Zhang, J. & Dulawa, S. C. The utility of animal models for studying the metabo-psychiatric origins of anorexia nervosa. Front. Psychiatry 12 , 711181 (2021).

Foldi, C. J., Milton, L. K. & Oldfield, B. J. The role of mesolimbic reward neurocircuitry in prevention and rescue of the activity-based anorexia phenotype in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 42 , 2292–2300 (2017).

Hebebrand, J., Muller, T., Holtkamp, K. & Herpertz-Dahlmann, B. The role of leptin in anorexia nervosa: clinical implications. Mol. Psychiatry 12 , 23–35 (2007).

Verhagen, L. A., Luijendijk, M. C. & Adan, R. A. Leptin reduces hyperactivity in an animal model for anorexia nervosa via the ventral tegmental area. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21 , 274–281 (2011).

Antel, J. et al. Rapid amelioration of anorexia nervosa in a male adolescent during metreleptin treatment including recovery from hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01778-7 (2021).

Burghardt, P. R. et al. Leptin regulates dopamine responses to sustained stress in humans. J. Neurosci. 32 , 15369–15376 (2012).

Wu, Q., Han, Y. & Tong, Q. in Neural Regulation of Metabolism (eds. Wu, Q. & Zheng, R.) 211–233 (Springer, 2018).

Xu, P. et al. Activation of serotonin 2C receptors in dopamine neurons inhibits binge-like eating in mice. Biol. Psychiatry 81 , 737–747 (2017).

Marino, R. A. M. et al. Control of food approach and eating by a GABAergic projection from lateral hypothalamus to dorsal pons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 8611–8615 (2020).

Wu, H. et al. Closing the loop on impulsivity via nucleus accumbens delta-band activity in mice and man. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115 , 192–197 (2018).

Halpern, C. H. et al. Amelioration of binge eating by nucleus accumbens shell deep brain stimulation in mice involves D2 receptor modulation. J. Neurosci. 33 , 7122–7129 (2013).

London, T. D. et al. Coordinated ramping of dorsal striatal pathways preceding food approach and consumption. J. Neurosci. 38 , 3547–3558 (2018).

Livneh, Y. et al. Homeostatic circuits selectively gate food cue responses in insular cortex. Nature 546 , 611–616 (2017).

Kusumoto-Yoshida, I., Liu, H., Chen, B. T., Fontanini, A. & Bonci, A. Central role for the insular cortex in mediating conditioned responses to anticipatory cues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 1190–1195 (2015).

Price, A. E., Stutz, S. J., Hommel, J. D., Anastasio, N. C. & Cunningham, K. A. Anterior insula activity regulates the associated behaviors of high fat food binge intake and cue reactivity in male rats. Appetite 133 , 231–239 (2019).

Wu, Y. et al. The anterior insular cortex unilaterally controls feeding in response to aversive visceral stimuli in mice. Nat. Commun. 11 , 640 (2020).

Spierling, S. et al. Insula to ventral striatal projections mediate compulsive eating produced by intermittent access to palatable food. Neuropsychopharmacology 45 , 579–588 (2020).

Anastasio, N. C. et al. Convergent neural connectivity in motor impulsivity and high-fat food binge-like eating in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 44 , 1752–1761 (2019).

Newmyer, B. A. et al. VIPergic neurons of the infralimbic and prelimbic cortices control palatable food intake through separate cognitive pathways. JCI Insight 5 , e126283 (2019).

Mathis, A. et al. DeepLabCut: markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat. Neurosci. 21 , 1281–1289 (2018).

Maussion, G., Demirova, I., Gorwood, P. & Ramoz, N. Induced pluripotent stem cells: new tools for investigating molecular mechanisms in anorexia nervosa. Front. Nutr. 6 , 118 (2019).

Breen, G. et al. Translating genome-wide association findings into new therapeutics for psychiatry. Nat. Neurosci. 19 , 1392–1396 (2016).

Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G. & Tavolacci, M. P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109 , 1402–1413 (2019).

Papadopoulos, F., Ekbom, A., Brandt, L. & Ekselius, L. Excess mortality, causes of death and prognostic factors in anorexia nervosa. Br. J. Psychiatry 194 , 10–17 (2009).

Yao, S. et al. Familial liability for eating disorders and suicide attempts: evidence from a population registry in Sweden. JAMA Psychiatry 73 , 284–291 (2016).

Fichter, M. M., Quadflieg, N., Crosby, R. D. & Koch, S. Long-term outcome of anorexia nervosa: results from a large clinical longitudinal study. Int J. Eat. Disord. 50 , 1018–1030 (2017).

Berkman, N. et al. Management of eating disorders. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. 135 , 1–166 (2006).

Keski-Rahkonen, A. et al. Epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community. Am. J. Psychiatry 164 , 1259–1265 (2007).

Brownley, K. et al. Binge-eating disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 165 , 409–420 (2016).

Fornaro, M. et al. Lisdexamfetamine in the treatment of moderate-to-severe binge eating disorder in adults: systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis of publicly available placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 12 , 1827–1836 (2016).

Hall, J. F., Smith, K., Schnitzer, S. B. & Hanford, P. V. Elevation of activity level in the rat following transition from ad libitum to restricted feeding. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 46 , 429–433 (1953).

Schalla, M. A. & Stengel, A. Activity based anorexia as an animal model for anorexia nervosa—a systematic review. Front Nutr. 6 , 69 (2019).

Novelle, M. G. & Diéguez, C. Food addiction and binge eating: lessons learned from animal models. Nutrients 10 , 71 (2018).

Article PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Corwin, R. L. & Babbs, R. K. Rodent models of binge eating: are they models of addiction? ILAR J. 53 , 23–34 (2012).

Moore, C. F., Sabino, V., Koob, G. F. & Cottone, P. Pathological overeating: emerging evidence for a compulsivity construct. Neuropsychopharmacology 42 , 1375–1389 (2017).

Rospond, B., Szpigiel, J., Sadakierska-Chudy, A. & Filip, M. Binge eating in preclinical models. Pharmacol. Rep. 67 , 504–512 (2015).

Cottone, P., Sabino, V., Steardo, L. & Zorrilla, E. P. Intermittent access to preferred food reduces the reinforcing efficacy of chow in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 295 , R1066–R1076 (2008).

Hardaway, J. A. et al. Nociceptin receptor antagonist SB 612111 decreases high-fat diet binge eating. Behav. Brain Res. 307 , 25–34 (2016).

Download references

Acknowledgements

C.M.B. is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH120170, R01MH124871, R01MH119084, R01MH118278 and R01MH124871), a Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Distinguished Investigator grant, the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, award no. 538-2013-8864), and the Lundbeck Foundation (grant no. R276-2018-4581). J.R.I.C. and G.B. acknowledge that the paper represents independent research part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. J.A.H. is supported by K01DK115902. C.D.B. is supported by U01DA050243 and U01DA055299. L.B. is supported by T32MH112485, a Harvard Medical School Livingston Fellowship and the International OCD Foundation. G.B. is also supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MR/V012878/1, MR/V03605X/1 and MR/R024804/1) and Charlotte’s Helix.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Cynthia M. Bulik & Hunna J. Watson

Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Cynthia M. Bulik

Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK

Jonathan R. I. Coleman & Gerome Breen

National Institute of Health Research Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre, South London and Maudsley National Health Service Trust, London, UK

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

J. Andrew Hardaway

Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Lauren Breithaupt

Eating Disorders Clinical and Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

School of Psychology, Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia, Australia

Hunna J. Watson

Division of Paediatrics, School of Medicine, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia

Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics and Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA

Camron D. Bryant

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

C.M.B., J.R.I.C., J.A.H., L.B., C.D.B., H.W. and G.B. all substantially contributed to the writing of the manuscript, approved the submitted version, are personally accountable for their own contribution, and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cynthia M. Bulik .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

C.M.B. reports the following competing interests: Shire (grant recipient, Scientific Advisory Board member); Idorsia (consultant); Pearson (author, royalty recipient); Equip Health (Clinical Advisory Board Member). G.B. reports the following competing interests: Otsuka Pharma (advisory board); Illumina (grant recipient, conference sponsorship). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Neuroscience thanks Roger Adan, Sandra Sanchez-Roige, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bulik, C.M., Coleman, J.R.I., Hardaway, J.A. et al. Genetics and neurobiology of eating disorders. Nat Neurosci 25 , 543–554 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-022-01071-z

Download citation

Received : 03 May 2020

Accepted : 01 April 2022

Published : 06 May 2022

Issue Date : May 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-022-01071-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Unexpected identification of obesity-associated mutations in lep and mc4r genes in patients with anorexia nervosa.

- Luisa Sophie Rajcsanyi

- Yiran Zheng

- Anke Hinney

Scientific Reports (2024)

The multisensory mind: a systematic review of multisensory integration processing in Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa

- Giulia Brizzi

- Maria Sansoni

- Giuseppe Riva

Journal of Eating Disorders (2023)

Psilocybin for the treatment of anorexia nervosa

- Tomislav Majić

- Stefan Ehrlich

Nature Medicine (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Translational Research newsletter — top stories in biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma.

Advertisement

Anorexia nervosa and familial risk factors: a systematic review of the literature

- Open access

- Published: 25 August 2022

- Volume 42 , pages 25476–25484, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Antonio Del Casale ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2427-6944 1 ,

- Barbara Adriani 2 ,

- Martina Nicole Modesti 2 ,

- Serena Virzì 2 ,

- Giovanna Parmigiani 1 ,

- Alessandro Emiliano Vento 1 &

- Anna Maria Speranza 1

5913 Accesses

1 Altmetric

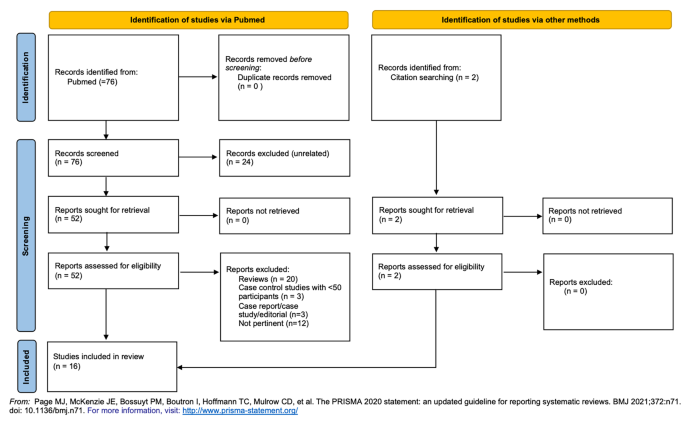

Explore all metrics

Anorexia Nervosa (AN) is a psychological disorder involving body manipulation, self-inflicted hunger, and fear of gaining weight.We performed an overview of the existing literature in the field of AN, highlighting the main intrafamilial risk factors for anorexia. We searched the PubMed database by using keywords such as “anorexia” and “risk factors” and “family”. After appropriate selection, 16 scientific articles were identified. The main intrafamilial risk factors for AN identified include: increased family food intake, higher parental demands, emotional reactivity, sexual family taboos, low familial involvement, family discord, negative family history for Eating Disorders (ED), family history of psychiatric disorders, alcohol and drug abuse, having a sibling with AN, relational trauma. Some other risk factors identified relate to the mother: lack of maternal caresses, dysfunctional interaction during feeding (for IA), attachment insecurity, dependence. Further studies are needed, to identify better personalized intervention strategies for patients suffering from AN.

Highlights:

This systematic review aims at identifying the main intrafamilial risk factors for anorexia nervosa, including maternal ones.

Intrafamilial risk factors identified mostly regard family environment and relational issues, as well as family history of psychiatric diseases.

Family risk factors identified may interact with genetic, environmental, and personal risk factors.

These findings may help develop tailored diagnostic procedures and therapeutic interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Factors predicting long-term weight maintenance in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review

Lydia Maurel, Molly MacKean & J. Hubert Lacey

An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Jie Qian, Ying Wu, … Dehua Yu

The Relationship Between Body Image Concerns, Eating Disorders and Internet Use, Part I: A Review of Empirical Support

Rachel F. Rodgers & Tiffany Melioli

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eating behavior encompasses all responses associated with the act of eating and is influenced by social conditions, individual perception, previous experiences, and nutritional status. Additional influencing factors include mass media and idealization of thinness. Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a psychological disorder concerning body manipulation, including fear of becoming fat and self-inflicted hunger. This disorder is interpreted as a response to the social context and a woman’s rejection of fat to deny mature sexuality (Gonçalves et al., 2013 ; Korb, 1994 ) and it was once supposed to have “hysterical” causes (Valente, 2016 ). The current definition of AN provided by the DSM-5 describes it as “a restriction of energy intake relative to requirements such as to lead to a significantly low body weight […]; intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, or persistence in behaviors that interfere with weight gain […]; alteration in the way weight or body shape are experienced […]” (Cuzzolaro, 2014 ). The lifetime prevalence of AN is estimated being of 1.4% (0.1–3.6%) in women and 0.2% (0-0.3%) in men (Galmiche et al., 2019 ). The lifetime prevalence rates of anorexia nervosa might be up to 4% among females and 0.3% among males (Van Eeden et al., 2021 ). AN finds its roots in biological, psychological, social, and familial risk factors.

More precisely, heritable risk factors for AN can be found in 48–74% of cases (Baker et al., 2017 ): for example, it has a higher prevalence in female relatives of individuals with AN (Bulik et al., 2019 ). The presence of genetic correlations between AN and metabolic and anthropometric traits may explain why people with AN achieve very low BMIs and may even maintain and relapse to low body weight despite clinical improvement (Bulik et al., 2019 ). On the other hand, psychological risk factors include excessive concerns about weight and figure, low self-esteem, and depression; while social risk factors are related to peer diet, peer criticism, and poor social support (Haynos et al., 2016 ). As far as family is concerned, it has been observed that anorexic girls’ families are often characterized by poor communication with one another, overprotection, conflicts, and hostility (Emanuelli et al., 2003 ; Horesh et al., 2015 ; Sim et al., 2009 ).

Overall, the puzzle of AN risk factors is still obscure and needs deeper investigations as far as some predisposing aspects are concerned, such as intrafamilial risk factors, which have been extensively analyzed but not properly clarified for clinical applications. Because of the multifactorial etiology of AN, intrafamilial risk factors identification can help to establish preventive interventions in at-risk individuals, and to provide tailored treatments from the earliest stages of the disorder. Our main hypothesis is that intrafamilial as well as maternal risk factors play an essential role in the development of the disease.