News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Research methods--quantitative, qualitative, and more: overview.

- Quantitative Research

- Qualitative Research

- Data Science Methods (Machine Learning, AI, Big Data)

- Text Mining and Computational Text Analysis

- Evidence Synthesis/Systematic Reviews

- Get Data, Get Help!

About Research Methods

This guide provides an overview of research methods, how to choose and use them, and supports and resources at UC Berkeley.

As Patten and Newhart note in the book Understanding Research Methods , "Research methods are the building blocks of the scientific enterprise. They are the "how" for building systematic knowledge. The accumulation of knowledge through research is by its nature a collective endeavor. Each well-designed study provides evidence that may support, amend, refute, or deepen the understanding of existing knowledge...Decisions are important throughout the practice of research and are designed to help researchers collect evidence that includes the full spectrum of the phenomenon under study, to maintain logical rules, and to mitigate or account for possible sources of bias. In many ways, learning research methods is learning how to see and make these decisions."

The choice of methods varies by discipline, by the kind of phenomenon being studied and the data being used to study it, by the technology available, and more. This guide is an introduction, but if you don't see what you need here, always contact your subject librarian, and/or take a look to see if there's a library research guide that will answer your question.

Suggestions for changes and additions to this guide are welcome!

START HERE: SAGE Research Methods

Without question, the most comprehensive resource available from the library is SAGE Research Methods. HERE IS THE ONLINE GUIDE to this one-stop shopping collection, and some helpful links are below:

- SAGE Research Methods

- Little Green Books (Quantitative Methods)

- Little Blue Books (Qualitative Methods)

- Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

- Case studies of real research projects

- Sample datasets for hands-on practice

- Streaming video--see methods come to life

- Methodspace- -a community for researchers

- SAGE Research Methods Course Mapping

Library Data Services at UC Berkeley

Library Data Services Program and Digital Scholarship Services

The LDSP offers a variety of services and tools ! From this link, check out pages for each of the following topics: discovering data, managing data, collecting data, GIS data, text data mining, publishing data, digital scholarship, open science, and the Research Data Management Program.

Be sure also to check out the visual guide to where to seek assistance on campus with any research question you may have!

Library GIS Services

Other Data Services at Berkeley

D-Lab Supports Berkeley faculty, staff, and graduate students with research in data intensive social science, including a wide range of training and workshop offerings Dryad Dryad is a simple self-service tool for researchers to use in publishing their datasets. It provides tools for the effective publication of and access to research data. Geospatial Innovation Facility (GIF) Provides leadership and training across a broad array of integrated mapping technologies on campu Research Data Management A UC Berkeley guide and consulting service for research data management issues

General Research Methods Resources

Here are some general resources for assistance:

- Assistance from ICPSR (must create an account to access): Getting Help with Data , and Resources for Students

- Wiley Stats Ref for background information on statistics topics

- Survey Documentation and Analysis (SDA) . Program for easy web-based analysis of survey data.

Consultants

- D-Lab/Data Science Discovery Consultants Request help with your research project from peer consultants.

- Research data (RDM) consulting Meet with RDM consultants before designing the data security, storage, and sharing aspects of your qualitative project.

- Statistics Department Consulting Services A service in which advanced graduate students, under faculty supervision, are available to consult during specified hours in the Fall and Spring semesters.

Related Resourcex

- IRB / CPHS Qualitative research projects with human subjects often require that you go through an ethics review.

- OURS (Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholarships) OURS supports undergraduates who want to embark on research projects and assistantships. In particular, check out their "Getting Started in Research" workshops

- Sponsored Projects Sponsored projects works with researchers applying for major external grants.

- Next: Quantitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 11:09 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/researchmethods

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

Related Resources

- —Identifying the Inquiry and Stating the Problem

PRACTICAL RESEARCH 2 – Choosing Research Topic View Download

Activity Sheets | DOC

Curriculum Information

Copyright information, technical information.

Research Methods

Chapter 2 introduction.

Maybe you have already gained some experience in doing research, for example in your bachelor studies, or as part of your work.

The challenge in conducting academic research at masters level, is that it is multi-faceted.

The types of activities are:

- Finding and reviewing literature on your research topic;

- Designing a research project that will answer your research questions;

- Collecting relevant data from one or more sources;

- Analyzing the data, statistically or otherwise, and

- Writing up and presenting your findings.

Some researchers are strong on some parts but weak on others.

We do not require perfection. But we do require high quality.

Going through all stages of the research project, with the guidance of your supervisor, is a learning process.

The journey is hard at times, but in the end your thesis is considered an academic publication, and we want you to be proud of what you have achieved!

Probably the biggest challenge is, where to begin?

- What will be your topic?

- And once you have selected a topic, what are the questions that you want to answer, and how?

In the first chapter of the book, you will find several views on the nature and scope of business research.

Since a study in business administration derives its relevance from its application to real-life situations, an MBA typically falls in the grey area between applied research and basic research.

The focus of applied research is on finding solutions to problems, and on improving (y)our understanding of existing theories of management.

Applied research that makes use of existing theories, often leads to amendments or refinements of these theories. That is, the applied research feeds back to basic research.

In the early stages of your research, you will feel like you are running around in circles.

You start with an idea for a research topic. Then, after reading literature on the topic, you will revise or refine your idea. And start reading again with a clearer focus ...

A thesis research/project typically consists of two main stages.

The first stage is the research proposal .

Once the research proposal has been approved, you can start with the data collection, analysis and write-up (including conclusions and recommendations).

Stage 1, the research proposal consists of he first three chapters of the commonly used five-chapter structure :

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- An introduction to the topic.

- The research questions that you want to answer (and/or hypotheses that you want to test).

- A note on why the research is of academic and/or professional relevance.

- Chapter 2: Literature

- A review of relevant literature on the topic.

- Chapter 3: Methodology

The methodology is at the core of your research. Here, you define how you are going to do the research. What data will be collected, and how?

Your data should allow you to answer your research questions. In the research proposal, you will also provide answers to the questions when and how much . Is it feasible to conduct the research within the given time-frame (say, 3-6 months for a typical master thesis)? And do you have the resources to collect and analyze the data?

In stage 2 you collect and analyze the data, and write the conclusions.

- Chapter 4: Data Analysis and Findings

- Chapter 5: Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

This video gives a nice overview of the elements of writing a thesis.

Chapter 2. Research Design

Getting started.

When I teach undergraduates qualitative research methods, the final product of the course is a “research proposal” that incorporates all they have learned and enlists the knowledge they have learned about qualitative research methods in an original design that addresses a particular research question. I highly recommend you think about designing your own research study as you progress through this textbook. Even if you don’t have a study in mind yet, it can be a helpful exercise as you progress through the course. But how to start? How can one design a research study before they even know what research looks like? This chapter will serve as a brief overview of the research design process to orient you to what will be coming in later chapters. Think of it as a “skeleton” of what you will read in more detail in later chapters. Ideally, you will read this chapter both now (in sequence) and later during your reading of the remainder of the text. Do not worry if you have questions the first time you read this chapter. Many things will become clearer as the text advances and as you gain a deeper understanding of all the components of good qualitative research. This is just a preliminary map to get you on the right road.

Research Design Steps

Before you even get started, you will need to have a broad topic of interest in mind. [1] . In my experience, students can confuse this broad topic with the actual research question, so it is important to clearly distinguish the two. And the place to start is the broad topic. It might be, as was the case with me, working-class college students. But what about working-class college students? What’s it like to be one? Why are there so few compared to others? How do colleges assist (or fail to assist) them? What interested me was something I could barely articulate at first and went something like this: “Why was it so difficult and lonely to be me?” And by extension, “Did others share this experience?”

Once you have a general topic, reflect on why this is important to you. Sometimes we connect with a topic and we don’t really know why. Even if you are not willing to share the real underlying reason you are interested in a topic, it is important that you know the deeper reasons that motivate you. Otherwise, it is quite possible that at some point during the research, you will find yourself turned around facing the wrong direction. I have seen it happen many times. The reason is that the research question is not the same thing as the general topic of interest, and if you don’t know the reasons for your interest, you are likely to design a study answering a research question that is beside the point—to you, at least. And this means you will be much less motivated to carry your research to completion.

Researcher Note

Why do you employ qualitative research methods in your area of study? What are the advantages of qualitative research methods for studying mentorship?

Qualitative research methods are a huge opportunity to increase access, equity, inclusion, and social justice. Qualitative research allows us to engage and examine the uniquenesses/nuances within minoritized and dominant identities and our experiences with these identities. Qualitative research allows us to explore a specific topic, and through that exploration, we can link history to experiences and look for patterns or offer up a unique phenomenon. There’s such beauty in being able to tell a particular story, and qualitative research is a great mode for that! For our work, we examined the relationships we typically use the term mentorship for but didn’t feel that was quite the right word. Qualitative research allowed us to pick apart what we did and how we engaged in our relationships, which then allowed us to more accurately describe what was unique about our mentorship relationships, which we ultimately named liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021) . Qualitative research gave us the means to explore, process, and name our experiences; what a powerful tool!

How do you come up with ideas for what to study (and how to study it)? Where did you get the idea for studying mentorship?

Coming up with ideas for research, for me, is kind of like Googling a question I have, not finding enough information, and then deciding to dig a little deeper to get the answer. The idea to study mentorship actually came up in conversation with my mentorship triad. We were talking in one of our meetings about our relationship—kind of meta, huh? We discussed how we felt that mentorship was not quite the right term for the relationships we had built. One of us asked what was different about our relationships and mentorship. This all happened when I was taking an ethnography course. During the next session of class, we were discussing auto- and duoethnography, and it hit me—let’s explore our version of mentorship, which we later went on to name liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021 ). The idea and questions came out of being curious and wanting to find an answer. As I continue to research, I see opportunities in questions I have about my work or during conversations that, in our search for answers, end up exposing gaps in the literature. If I can’t find the answer already out there, I can study it.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

When you have a better idea of why you are interested in what it is that interests you, you may be surprised to learn that the obvious approaches to the topic are not the only ones. For example, let’s say you think you are interested in preserving coastal wildlife. And as a social scientist, you are interested in policies and practices that affect the long-term viability of coastal wildlife, especially around fishing communities. It would be natural then to consider designing a research study around fishing communities and how they manage their ecosystems. But when you really think about it, you realize that what interests you the most is how people whose livelihoods depend on a particular resource act in ways that deplete that resource. Or, even deeper, you contemplate the puzzle, “How do people justify actions that damage their surroundings?” Now, there are many ways to design a study that gets at that broader question, and not all of them are about fishing communities, although that is certainly one way to go. Maybe you could design an interview-based study that includes and compares loggers, fishers, and desert golfers (those who golf in arid lands that require a great deal of wasteful irrigation). Or design a case study around one particular example where resources were completely used up by a community. Without knowing what it is you are really interested in, what motivates your interest in a surface phenomenon, you are unlikely to come up with the appropriate research design.

These first stages of research design are often the most difficult, but have patience . Taking the time to consider why you are going to go through a lot of trouble to get answers will prevent a lot of wasted energy in the future.

There are distinct reasons for pursuing particular research questions, and it is helpful to distinguish between them. First, you may be personally motivated. This is probably the most important and the most often overlooked. What is it about the social world that sparks your curiosity? What bothers you? What answers do you need in order to keep living? For me, I knew I needed to get a handle on what higher education was for before I kept going at it. I needed to understand why I felt so different from my peers and whether this whole “higher education” thing was “for the likes of me” before I could complete my degree. That is the personal motivation question. Your personal motivation might also be political in nature, in that you want to change the world in a particular way. It’s all right to acknowledge this. In fact, it is better to acknowledge it than to hide it.

There are also academic and professional motivations for a particular study. If you are an absolute beginner, these may be difficult to find. We’ll talk more about this when we discuss reviewing the literature. Simply put, you are probably not the only person in the world to have thought about this question or issue and those related to it. So how does your interest area fit into what others have studied? Perhaps there is a good study out there of fishing communities, but no one has quite asked the “justification” question. You are motivated to address this to “fill the gap” in our collective knowledge. And maybe you are really not at all sure of what interests you, but you do know that [insert your topic] interests a lot of people, so you would like to work in this area too. You want to be involved in the academic conversation. That is a professional motivation and a very important one to articulate.

Practical and strategic motivations are a third kind. Perhaps you want to encourage people to take better care of the natural resources around them. If this is also part of your motivation, you will want to design your research project in a way that might have an impact on how people behave in the future. There are many ways to do this, one of which is using qualitative research methods rather than quantitative research methods, as the findings of qualitative research are often easier to communicate to a broader audience than the results of quantitative research. You might even be able to engage the community you are studying in the collecting and analyzing of data, something taboo in quantitative research but actively embraced and encouraged by qualitative researchers. But there are other practical reasons, such as getting “done” with your research in a certain amount of time or having access (or no access) to certain information. There is nothing wrong with considering constraints and opportunities when designing your study. Or maybe one of the practical or strategic goals is about learning competence in this area so that you can demonstrate the ability to conduct interviews and focus groups with future employers. Keeping that in mind will help shape your study and prevent you from getting sidetracked using a technique that you are less invested in learning about.

STOP HERE for a moment

I recommend you write a paragraph (at least) explaining your aims and goals. Include a sentence about each of the following: personal/political goals, practical or professional/academic goals, and practical/strategic goals. Think through how all of the goals are related and can be achieved by this particular research study . If they can’t, have a rethink. Perhaps this is not the best way to go about it.

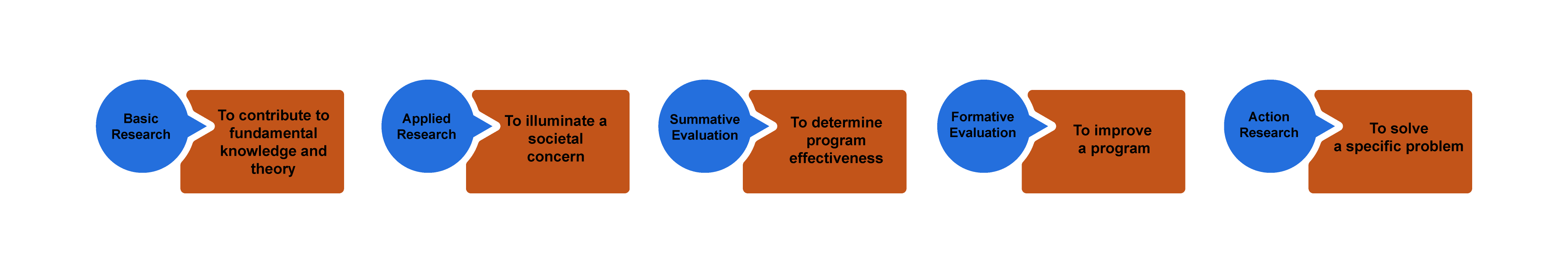

You will also want to be clear about the purpose of your study. “Wait, didn’t we just do this?” you might ask. No! Your goals are not the same as the purpose of the study, although they are related. You can think about purpose lying on a continuum from “ theory ” to “action” (figure 2.1). Sometimes you are doing research to discover new knowledge about the world, while other times you are doing a study because you want to measure an impact or make a difference in the world.

Basic research involves research that is done for the sake of “pure” knowledge—that is, knowledge that, at least at this moment in time, may not have any apparent use or application. Often, and this is very important, knowledge of this kind is later found to be extremely helpful in solving problems. So one way of thinking about basic research is that it is knowledge for which no use is yet known but will probably one day prove to be extremely useful. If you are doing basic research, you do not need to argue its usefulness, as the whole point is that we just don’t know yet what this might be.

Researchers engaged in basic research want to understand how the world operates. They are interested in investigating a phenomenon to get at the nature of reality with regard to that phenomenon. The basic researcher’s purpose is to understand and explain ( Patton 2002:215 ).

Basic research is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works. Grounded Theory is one approach to qualitative research methods that exemplifies basic research (see chapter 4). Most academic journal articles publish basic research findings. If you are working in academia (e.g., writing your dissertation), the default expectation is that you are conducting basic research.

Applied research in the social sciences is research that addresses human and social problems. Unlike basic research, the researcher has expectations that the research will help contribute to resolving a problem, if only by identifying its contours, history, or context. From my experience, most students have this as their baseline assumption about research. Why do a study if not to make things better? But this is a common mistake. Students and their committee members are often working with default assumptions here—the former thinking about applied research as their purpose, the latter thinking about basic research: “The purpose of applied research is to contribute knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment. While in basic research the source of questions is the tradition within a scholarly discipline, in applied research the source of questions is in the problems and concerns experienced by people and by policymakers” ( Patton 2002:217 ).

Applied research is less geared toward theory in two ways. First, its questions do not derive from previous literature. For this reason, applied research studies have much more limited literature reviews than those found in basic research (although they make up for this by having much more “background” about the problem). Second, it does not generate theory in the same way as basic research does. The findings of an applied research project may not be generalizable beyond the boundaries of this particular problem or context. The findings are more limited. They are useful now but may be less useful later. This is why basic research remains the default “gold standard” of academic research.

Evaluation research is research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. We already know the problems, and someone has already come up with solutions. There might be a program, say, for first-generation college students on your campus. Does this program work? Are first-generation students who participate in the program more likely to graduate than those who do not? These are the types of questions addressed by evaluation research. There are two types of research within this broader frame; however, one more action-oriented than the next. In summative evaluation , an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made. Should we continue our first-gen program? Is it a good model for other campuses? Because the purpose of such summative evaluation is to measure success and to determine whether this success is scalable (capable of being generalized beyond the specific case), quantitative data is more often used than qualitative data. In our example, we might have “outcomes” data for thousands of students, and we might run various tests to determine if the better outcomes of those in the program are statistically significant so that we can generalize the findings and recommend similar programs elsewhere. Qualitative data in the form of focus groups or interviews can then be used for illustrative purposes, providing more depth to the quantitative analyses. In contrast, formative evaluation attempts to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness). Formative evaluations rely more heavily on qualitative data—case studies, interviews, focus groups. The findings are meant not to generalize beyond the particular but to improve this program. If you are a student seeking to improve your qualitative research skills and you do not care about generating basic research, formative evaluation studies might be an attractive option for you to pursue, as there are always local programs that need evaluation and suggestions for improvement. Again, be very clear about your purpose when talking through your research proposal with your committee.

Action research takes a further step beyond evaluation, even formative evaluation, to being part of the solution itself. This is about as far from basic research as one could get and definitely falls beyond the scope of “science,” as conventionally defined. The distinction between action and research is blurry, the research methods are often in constant flux, and the only “findings” are specific to the problem or case at hand and often are findings about the process of intervention itself. Rather than evaluate a program as a whole, action research often seeks to change and improve some particular aspect that may not be working—maybe there is not enough diversity in an organization or maybe women’s voices are muted during meetings and the organization wonders why and would like to change this. In a further step, participatory action research , those women would become part of the research team, attempting to amplify their voices in the organization through participation in the action research. As action research employs methods that involve people in the process, focus groups are quite common.

If you are working on a thesis or dissertation, chances are your committee will expect you to be contributing to fundamental knowledge and theory ( basic research ). If your interests lie more toward the action end of the continuum, however, it is helpful to talk to your committee about this before you get started. Knowing your purpose in advance will help avoid misunderstandings during the later stages of the research process!

The Research Question

Once you have written your paragraph and clarified your purpose and truly know that this study is the best study for you to be doing right now , you are ready to write and refine your actual research question. Know that research questions are often moving targets in qualitative research, that they can be refined up to the very end of data collection and analysis. But you do have to have a working research question at all stages. This is your “anchor” when you get lost in the data. What are you addressing? What are you looking at and why? Your research question guides you through the thicket. It is common to have a whole host of questions about a phenomenon or case, both at the outset and throughout the study, but you should be able to pare it down to no more than two or three sentences when asked. These sentences should both clarify the intent of the research and explain why this is an important question to answer. More on refining your research question can be found in chapter 4.

Chances are, you will have already done some prior reading before coming up with your interest and your questions, but you may not have conducted a systematic literature review. This is the next crucial stage to be completed before venturing further. You don’t want to start collecting data and then realize that someone has already beaten you to the punch. A review of the literature that is already out there will let you know (1) if others have already done the study you are envisioning; (2) if others have done similar studies, which can help you out; and (3) what ideas or concepts are out there that can help you frame your study and make sense of your findings. More on literature reviews can be found in chapter 9.

In addition to reviewing the literature for similar studies to what you are proposing, it can be extremely helpful to find a study that inspires you. This may have absolutely nothing to do with the topic you are interested in but is written so beautifully or organized so interestingly or otherwise speaks to you in such a way that you want to post it somewhere to remind you of what you want to be doing. You might not understand this in the early stages—why would you find a study that has nothing to do with the one you are doing helpful? But trust me, when you are deep into analysis and writing, having an inspirational model in view can help you push through. If you are motivated to do something that might change the world, you probably have read something somewhere that inspired you. Go back to that original inspiration and read it carefully and see how they managed to convey the passion that you so appreciate.

At this stage, you are still just getting started. There are a lot of things to do before setting forth to collect data! You’ll want to consider and choose a research tradition and a set of data-collection techniques that both help you answer your research question and match all your aims and goals. For example, if you really want to help migrant workers speak for themselves, you might draw on feminist theory and participatory action research models. Chapters 3 and 4 will provide you with more information on epistemologies and approaches.

Next, you have to clarify your “units of analysis.” What is the level at which you are focusing your study? Often, the unit in qualitative research methods is individual people, or “human subjects.” But your units of analysis could just as well be organizations (colleges, hospitals) or programs or even whole nations. Think about what it is you want to be saying at the end of your study—are the insights you are hoping to make about people or about organizations or about something else entirely? A unit of analysis can even be a historical period! Every unit of analysis will call for a different kind of data collection and analysis and will produce different kinds of “findings” at the conclusion of your study. [2]

Regardless of what unit of analysis you select, you will probably have to consider the “human subjects” involved in your research. [3] Who are they? What interactions will you have with them—that is, what kind of data will you be collecting? Before answering these questions, define your population of interest and your research setting. Use your research question to help guide you.

Let’s use an example from a real study. In Geographies of Campus Inequality , Benson and Lee ( 2020 ) list three related research questions: “(1) What are the different ways that first-generation students organize their social, extracurricular, and academic activities at selective and highly selective colleges? (2) how do first-generation students sort themselves and get sorted into these different types of campus lives; and (3) how do these different patterns of campus engagement prepare first-generation students for their post-college lives?” (3).

Note that we are jumping into this a bit late, after Benson and Lee have described previous studies (the literature review) and what is known about first-generation college students and what is not known. They want to know about differences within this group, and they are interested in ones attending certain kinds of colleges because those colleges will be sites where academic and extracurricular pressures compete. That is the context for their three related research questions. What is the population of interest here? First-generation college students . What is the research setting? Selective and highly selective colleges . But a host of questions remain. Which students in the real world, which colleges? What about gender, race, and other identity markers? Will the students be asked questions? Are the students still in college, or will they be asked about what college was like for them? Will they be observed? Will they be shadowed? Will they be surveyed? Will they be asked to keep diaries of their time in college? How many students? How many colleges? For how long will they be observed?

Recommendation

Take a moment and write down suggestions for Benson and Lee before continuing on to what they actually did.

Have you written down your own suggestions? Good. Now let’s compare those with what they actually did. Benson and Lee drew on two sources of data: in-depth interviews with sixty-four first-generation students and survey data from a preexisting national survey of students at twenty-eight selective colleges. Let’s ignore the survey for our purposes here and focus on those interviews. The interviews were conducted between 2014 and 2016 at a single selective college, “Hilltop” (a pseudonym ). They employed a “purposive” sampling strategy to ensure an equal number of male-identifying and female-identifying students as well as equal numbers of White, Black, and Latinx students. Each student was interviewed once. Hilltop is a selective liberal arts college in the northeast that enrolls about three thousand students.

How did your suggestions match up to those actually used by the researchers in this study? It is possible your suggestions were too ambitious? Beginning qualitative researchers can often make that mistake. You want a research design that is both effective (it matches your question and goals) and doable. You will never be able to collect data from your entire population of interest (unless your research question is really so narrow to be relevant to very few people!), so you will need to come up with a good sample. Define the criteria for this sample, as Benson and Lee did when deciding to interview an equal number of students by gender and race categories. Define the criteria for your sample setting too. Hilltop is typical for selective colleges. That was a research choice made by Benson and Lee. For more on sampling and sampling choices, see chapter 5.

Benson and Lee chose to employ interviews. If you also would like to include interviews, you have to think about what will be asked in them. Most interview-based research involves an interview guide, a set of questions or question areas that will be asked of each participant. The research question helps you create a relevant interview guide. You want to ask questions whose answers will provide insight into your research question. Again, your research question is the anchor you will continually come back to as you plan for and conduct your study. It may be that once you begin interviewing, you find that people are telling you something totally unexpected, and this makes you rethink your research question. That is fine. Then you have a new anchor. But you always have an anchor. More on interviewing can be found in chapter 11.

Let’s imagine Benson and Lee also observed college students as they went about doing the things college students do, both in the classroom and in the clubs and social activities in which they participate. They would have needed a plan for this. Would they sit in on classes? Which ones and how many? Would they attend club meetings and sports events? Which ones and how many? Would they participate themselves? How would they record their observations? More on observation techniques can be found in both chapters 13 and 14.

At this point, the design is almost complete. You know why you are doing this study, you have a clear research question to guide you, you have identified your population of interest and research setting, and you have a reasonable sample of each. You also have put together a plan for data collection, which might include drafting an interview guide or making plans for observations. And so you know exactly what you will be doing for the next several months (or years!). To put the project into action, there are a few more things necessary before actually going into the field.

First, you will need to make sure you have any necessary supplies, including recording technology. These days, many researchers use their phones to record interviews. Second, you will need to draft a few documents for your participants. These include informed consent forms and recruiting materials, such as posters or email texts, that explain what this study is in clear language. Third, you will draft a research protocol to submit to your institutional review board (IRB) ; this research protocol will include the interview guide (if you are using one), the consent form template, and all examples of recruiting material. Depending on your institution and the details of your study design, it may take weeks or even, in some unfortunate cases, months before you secure IRB approval. Make sure you plan on this time in your project timeline. While you wait, you can continue to review the literature and possibly begin drafting a section on the literature review for your eventual presentation/publication. More on IRB procedures can be found in chapter 8 and more general ethical considerations in chapter 7.

Once you have approval, you can begin!

Research Design Checklist

Before data collection begins, do the following:

- Write a paragraph explaining your aims and goals (personal/political, practical/strategic, professional/academic).

- Define your research question; write two to three sentences that clarify the intent of the research and why this is an important question to answer.

- Review the literature for similar studies that address your research question or similar research questions; think laterally about some literature that might be helpful or illuminating but is not exactly about the same topic.

- Find a written study that inspires you—it may or may not be on the research question you have chosen.

- Consider and choose a research tradition and set of data-collection techniques that (1) help answer your research question and (2) match your aims and goals.

- Define your population of interest and your research setting.

- Define the criteria for your sample (How many? Why these? How will you find them, gain access, and acquire consent?).

- If you are conducting interviews, draft an interview guide.

- If you are making observations, create a plan for observations (sites, times, recording, access).

- Acquire any necessary technology (recording devices/software).

- Draft consent forms that clearly identify the research focus and selection process.

- Create recruiting materials (posters, email, texts).

- Apply for IRB approval (proposal plus consent form plus recruiting materials).

- Block out time for collecting data.

- At the end of the chapter, you will find a " Research Design Checklist " that summarizes the main recommendations made here ↵

- For example, if your focus is society and culture , you might collect data through observation or a case study. If your focus is individual lived experience , you are probably going to be interviewing some people. And if your focus is language and communication , you will probably be analyzing text (written or visual). ( Marshall and Rossman 2016:16 ). ↵

- You may not have any "live" human subjects. There are qualitative research methods that do not require interactions with live human beings - see chapter 16 , "Archival and Historical Sources." But for the most part, you are probably reading this textbook because you are interested in doing research with people. The rest of the chapter will assume this is the case. ↵

One of the primary methodological traditions of inquiry in qualitative research, ethnography is the study of a group or group culture, largely through observational fieldwork supplemented by interviews. It is a form of fieldwork that may include participant-observation data collection. See chapter 14 for a discussion of deep ethnography.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and research design that focuses on an individual case (e.g., setting, institution, or sometimes an individual) in order to explore its complexity, history, and interactive parts. As an approach, it is particularly useful for obtaining a deep appreciation of an issue, event, or phenomenon of interest in its particular context.

The controlling force in research; can be understood as lying on a continuum from basic research (knowledge production) to action research (effecting change).

In its most basic sense, a theory is a story we tell about how the world works that can be tested with empirical evidence. In qualitative research, we use the term in a variety of ways, many of which are different from how they are used by quantitative researchers. Although some qualitative research can be described as “testing theory,” it is more common to “build theory” from the data using inductive reasoning , as done in Grounded Theory . There are so-called “grand theories” that seek to integrate a whole series of findings and stories into an overarching paradigm about how the world works, and much smaller theories or concepts about particular processes and relationships. Theory can even be used to explain particular methodological perspectives or approaches, as in Institutional Ethnography , which is both a way of doing research and a theory about how the world works.

Research that is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and approach to analyzing qualitative data in which theories emerge from a rigorous and systematic process of induction. This approach was pioneered by the sociologists Glaser and Strauss (1967). The elements of theory generated from comparative analysis of data are, first, conceptual categories and their properties and, second, hypotheses or generalized relations among the categories and their properties – “The constant comparing of many groups draws the [researcher’s] attention to their many similarities and differences. Considering these leads [the researcher] to generate abstract categories and their properties, which, since they emerge from the data, will clearly be important to a theory explaining the kind of behavior under observation.” (36).

An approach to research that is “multimethod in focus, involving an interpretative, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research involves the studied use and collection of a variety of empirical materials – case study, personal experience, introspective, life story, interview, observational, historical, interactional, and visual texts – that describe routine and problematic moments and meanings in individuals’ lives." ( Denzin and Lincoln 2005:2 ). Contrast with quantitative research .

Research that contributes knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment.

Research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. There are two kinds: summative and formative .

Research in which an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made, often for the purpose of generalizing to other cases or programs. Generally uses qualitative research as a supplement to primary quantitative data analyses. Contrast formative evaluation research .

Research designed to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness); relies heavily on qualitative research methods. Contrast summative evaluation research

Research carried out at a particular organizational or community site with the intention of affecting change; often involves research subjects as participants of the study. See also participatory action research .

Research in which both researchers and participants work together to understand a problematic situation and change it for the better.

The level of the focus of analysis (e.g., individual people, organizations, programs, neighborhoods).

The large group of interest to the researcher. Although it will likely be impossible to design a study that incorporates or reaches all members of the population of interest, this should be clearly defined at the outset of a study so that a reasonable sample of the population can be taken. For example, if one is studying working-class college students, the sample may include twenty such students attending a particular college, while the population is “working-class college students.” In quantitative research, clearly defining the general population of interest is a necessary step in generalizing results from a sample. In qualitative research, defining the population is conceptually important for clarity.

A fictional name assigned to give anonymity to a person, group, or place. Pseudonyms are important ways of protecting the identity of research participants while still providing a “human element” in the presentation of qualitative data. There are ethical considerations to be made in selecting pseudonyms; some researchers allow research participants to choose their own.

A requirement for research involving human participants; the documentation of informed consent. In some cases, oral consent or assent may be sufficient, but the default standard is a single-page easy-to-understand form that both the researcher and the participant sign and date. Under federal guidelines, all researchers "shall seek such consent only under circumstances that provide the prospective subject or the representative sufficient opportunity to consider whether or not to participate and that minimize the possibility of coercion or undue influence. The information that is given to the subject or the representative shall be in language understandable to the subject or the representative. No informed consent, whether oral or written, may include any exculpatory language through which the subject or the representative is made to waive or appear to waive any of the subject's rights or releases or appears to release the investigator, the sponsor, the institution, or its agents from liability for negligence" (21 CFR 50.20). Your IRB office will be able to provide a template for use in your study .

An administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities conducted under the auspices of the institution with which it is affiliated. The IRB is charged with the responsibility of reviewing all research involving human participants. The IRB is concerned with protecting the welfare, rights, and privacy of human subjects. The IRB has the authority to approve, disapprove, monitor, and require modifications in all research activities that fall within its jurisdiction as specified by both the federal regulations and institutional policy.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

Types of Research – Explained with Examples

- By DiscoverPhDs

- October 2, 2020

Types of Research

Research is about using established methods to investigate a problem or question in detail with the aim of generating new knowledge about it.

It is a vital tool for scientific advancement because it allows researchers to prove or refute hypotheses based on clearly defined parameters, environments and assumptions. Due to this, it enables us to confidently contribute to knowledge as it allows research to be verified and replicated.

Knowing the types of research and what each of them focuses on will allow you to better plan your project, utilises the most appropriate methodologies and techniques and better communicate your findings to other researchers and supervisors.

Classification of Types of Research

There are various types of research that are classified according to their objective, depth of study, analysed data, time required to study the phenomenon and other factors. It’s important to note that a research project will not be limited to one type of research, but will likely use several.

According to its Purpose

Theoretical research.

Theoretical research, also referred to as pure or basic research, focuses on generating knowledge , regardless of its practical application. Here, data collection is used to generate new general concepts for a better understanding of a particular field or to answer a theoretical research question.

Results of this kind are usually oriented towards the formulation of theories and are usually based on documentary analysis, the development of mathematical formulas and the reflection of high-level researchers.

Applied Research

Here, the goal is to find strategies that can be used to address a specific research problem. Applied research draws on theory to generate practical scientific knowledge, and its use is very common in STEM fields such as engineering, computer science and medicine.

This type of research is subdivided into two types:

- Technological applied research : looks towards improving efficiency in a particular productive sector through the improvement of processes or machinery related to said productive processes.

- Scientific applied research : has predictive purposes. Through this type of research design, we can measure certain variables to predict behaviours useful to the goods and services sector, such as consumption patterns and viability of commercial projects.

According to your Depth of Scope

Exploratory research.

Exploratory research is used for the preliminary investigation of a subject that is not yet well understood or sufficiently researched. It serves to establish a frame of reference and a hypothesis from which an in-depth study can be developed that will enable conclusive results to be generated.

Because exploratory research is based on the study of little-studied phenomena, it relies less on theory and more on the collection of data to identify patterns that explain these phenomena.

Descriptive Research

The primary objective of descriptive research is to define the characteristics of a particular phenomenon without necessarily investigating the causes that produce it.

In this type of research, the researcher must take particular care not to intervene in the observed object or phenomenon, as its behaviour may change if an external factor is involved.

Explanatory Research

Explanatory research is the most common type of research method and is responsible for establishing cause-and-effect relationships that allow generalisations to be extended to similar realities. It is closely related to descriptive research, although it provides additional information about the observed object and its interactions with the environment.

Correlational Research

The purpose of this type of scientific research is to identify the relationship between two or more variables. A correlational study aims to determine whether a variable changes, how much the other elements of the observed system change.

According to the Type of Data Used

Qualitative research.

Qualitative methods are often used in the social sciences to collect, compare and interpret information, has a linguistic-semiotic basis and is used in techniques such as discourse analysis, interviews, surveys, records and participant observations.

In order to use statistical methods to validate their results, the observations collected must be evaluated numerically. Qualitative research, however, tends to be subjective, since not all data can be fully controlled. Therefore, this type of research design is better suited to extracting meaning from an event or phenomenon (the ‘why’) than its cause (the ‘how’).

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research study delves into a phenomena through quantitative data collection and using mathematical, statistical and computer-aided tools to measure them . This allows generalised conclusions to be projected over time.

According to the Degree of Manipulation of Variables

Experimental research.

It is about designing or replicating a phenomenon whose variables are manipulated under strictly controlled conditions in order to identify or discover its effect on another independent variable or object. The phenomenon to be studied is measured through study and control groups, and according to the guidelines of the scientific method.

Non-Experimental Research

Also known as an observational study, it focuses on the analysis of a phenomenon in its natural context. As such, the researcher does not intervene directly, but limits their involvement to measuring the variables required for the study. Due to its observational nature, it is often used in descriptive research.

Quasi-Experimental Research

It controls only some variables of the phenomenon under investigation and is therefore not entirely experimental. In this case, the study and the focus group cannot be randomly selected, but are chosen from existing groups or populations . This is to ensure the collected data is relevant and that the knowledge, perspectives and opinions of the population can be incorporated into the study.

According to the Type of Inference

Deductive investigation.

In this type of research, reality is explained by general laws that point to certain conclusions; conclusions are expected to be part of the premise of the research problem and considered correct if the premise is valid and the inductive method is applied correctly.

Inductive Research

In this type of research, knowledge is generated from an observation to achieve a generalisation. It is based on the collection of specific data to develop new theories.

Hypothetical-Deductive Investigation

It is based on observing reality to make a hypothesis, then use deduction to obtain a conclusion and finally verify or reject it through experience.

According to the Time in Which it is Carried Out

Longitudinal study (also referred to as diachronic research).

It is the monitoring of the same event, individual or group over a defined period of time. It aims to track changes in a number of variables and see how they evolve over time. It is often used in medical, psychological and social areas .

Cross-Sectional Study (also referred to as Synchronous Research)

Cross-sectional research design is used to observe phenomena, an individual or a group of research subjects at a given time.

According to The Sources of Information

Primary research.

This fundamental research type is defined by the fact that the data is collected directly from the source, that is, it consists of primary, first-hand information.

Secondary research

Unlike primary research, secondary research is developed with information from secondary sources, which are generally based on scientific literature and other documents compiled by another researcher.

According to How the Data is Obtained

Documentary (cabinet).

Documentary research, or secondary sources, is based on a systematic review of existing sources of information on a particular subject. This type of scientific research is commonly used when undertaking literature reviews or producing a case study.

Field research study involves the direct collection of information at the location where the observed phenomenon occurs.

From Laboratory

Laboratory research is carried out in a controlled environment in order to isolate a dependent variable and establish its relationship with other variables through scientific methods.

Mixed-Method: Documentary, Field and/or Laboratory

Mixed research methodologies combine results from both secondary (documentary) sources and primary sources through field or laboratory research.

Thinking about applying to a PhD? Then don’t miss out on these 4 tips on how to best prepare your application.

Impostor Syndrome is a common phenomenon amongst PhD students, leading to self-doubt and fear of being exposed as a “fraud”. How can we overcome these feelings?

Learn about defining your workspace, having a list of daily tasks and using technology to stay connected, all whilst working from home as a research student.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

The term monotonic relationship is a statistical definition that is used to describe the link between two variables.

An abstract and introduction are the first two sections of your paper or thesis. This guide explains the differences between them and how to write them.

Dr Young gained his PhD in Neuroscience from the University of Cambridge. He is now a a Senior Lecturer at the University of Portsmouth, Deputy Director for the Institute of Biological and Biomedical Sciences and more!

Raluca is a final year PhD student at Queen Mary University of London. Her research is on exploring the algorithms of rolling horizon evolutionary algorithms for general video game playing.

Join Thousands of Students

Practical Research 2 Module: Nature of Inquiry and Research

This Senior High School Practical Research 2 Self-Learning Module (SLM) is prepared so that you, our dear learners, can continue your studies and learn while at home. Activities, questions, directions, exercises, and discussions are carefully stated for you to understand each lesson.

At the end of this module, you should be able to:

1. Describe the characteristics, strengths, weaknesses, and kinds of quantitative research (CS_RS12-Ia-c-1) ;

2. Illustrate the importance of quantitative research across field (CS_RS12-Iac-2) ;

3. Differentiate the kinds of variables and their uses (CS_RS12-Ia-c-3) .

Senior High School Quarter 1 Self-Learning Module Practical Research 2 – Nature of Inquiry and Research

Can't find what you're looking for.

We are here to help - please use the search box below.

3 thoughts on “Practical Research 2 Module: Nature of Inquiry and Research”

Meron po ba kayong Practical Research 2 Quarter 2 Module 2-10? Baka naman…

Why can’t I download Module 1 of Practical Research 2?

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Office of Research

Research how 2.

Welcome to Office of Research’s integrated and functional portal designed to support University of Cincinnati’s faculty, staff and students. We believe connecting “how to’s” to the “why’s” is important, and key to establishing connections that build and extend knowledge with simple intuitive actions. With this in mind, we have introduced three key features in our newly upgraded website.

“Smart search” makes it easy to look for a specific document related to Office of Research’s work stream. Plug in search key words and the search engine queries all of our research resources to give you fast and relevance based results that support UC’s research excellence.

“Dynamic document filtering” functionality makes it easy to focus on select areas of interest and narrow down results as necessary. While working with specific offices, use the ”browse by office“ navigation and find a process driven search on the page. The dynamic filtering should give you results that connect forms to policies and provide you with the right tools such as procedures, training and resources.

“Pinned and Saved” will enhance the user experience by unlocking additional features that can customize the experience leveraging modern web technology. All our users, and power users in particular, are strongly recommend to enable browser cookies.

Launch “Application Tour” for stepping through these features.

Your feedback has brought us this far, help us in enhancing your experience! Please email us [email protected] with your feedback and ideas.

We Welcome Your Feedback

I'm sorry but you have too many items pinned for HRPP. You must unpin items if you want to pin any additional items.

Part 1. Overview Information

National Institutes of Health ( NIH )

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ( NHLBI )

National Institute on Aging ( NIA )

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism ( NIAAA )

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases ( NIAID )

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases ( NIAMS )

February 14, 2024 - Participation Added ( N0T-HD-24-007 ) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development ( NICHD )

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders ( NIDCD )

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research ( NIDCR )

National Institute on Drug Abuse ( NIDA )

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences ( NIEHS )

National Institute of General Medical Sciences ( NIGMS )

National Institute of Mental Health ( NIMH )

National Institute of Nursing Research ( NINR )

National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences ( NCATS )

National Center of Complementary and Integrative Health ( NCCIH )

All applications to this funding opportunity announcement should fall within the mission of the Institutes/Centers. The following NIH Offices may co-fund applications assigned to those Institutes/Centers.

Division of Program Coordination, Planning and Strategic Initiatives, Office of Disease Prevention ( ODP )

Office of Research on Women's Health ( ORWH )

UC2 High Impact Research and Research Infrastructure Cooperative Agreement Programs

- March 20, 2024 - Notice of Informational Webinar for PAR-23-144, STrengthening Research Opportunities for NIH Grants (STRONG): Structured Institutional Needs Assessment and Action Plan Development for Resource Limited Institutions (RLIs) (UC2 - Clinical Trial Not Allowed). See Notice NOT-MD-24-011

- February 14, 2024 - Notice of NICHD Participation in PAR-23-144 "Strengthening Research Opportunities for NIH Grants (STRONG): Structured Institutional Needs Assessment and Action Plan Development for Resource Limited Institutions"). See Notice NOT-HD-24-007

- August 31, 2023 - Notice of Correction to Eligibility Criteria of PAR-23-144, STrengthening Research Opportunities for NIH Grants (STRONG): Structured Institutional Needs Assessment and Action Plan Development for Resource Limited Institutions (RLIs) (UC2). See Notice NOT-MD-23-018

- May 12, 2023 - Notice of Participation of the NIAAA in PAR-23-144. See Notice NOT-AA-23-012 .

- April 25, 2023 - Notice of NCCIH Participation in PAR-23-144, "STrengthening Research Opportunities for NIH Grants (STRONG): Structured Institutional Needs Assessment and Action Plan Development for Resource Limited Institutions (RLIs) (UC2 - Clinical Trial Not Allowed). See Notice NOT-AT-24-004

- August 5, 2022 - Implementation Details for the NIH Data Management and Sharing Policy - see Notice NOT-OD-22-189 .

- August 8, 2022 - New NIH "FORMS-H" Grant Application Forms and Instructions Coming for Due Dates on or after January 25, 2023 - See Notice NOT-OD-22-195 .

- August 31, 2022 - Implementation Changes for Genomic Data Sharing Plans Included with Applications Due on or after January 25, 2023 - See Notice NOT-OD-22-198 .

See Section III. 3. Additional Information on Eligibility .

The STrengthening Research Opportunities for NIH Grants (STRONG): The STRONG-RLI program will support research capacity needs assessments by eligible Resource-Limited Institutions (RLIs). The program will also support the recipient institutions to use the results of the assessments to develop action plans for how to meet the identified needs.

RLIs are defined as institutions with a mission to serve historically underrepresented populations in biomedical research that award degrees in the health professions (and in STEM fields and social and behavioral sciences) and have received an average of $0 to $25 million per year (total costs) of NIH Research Project Grant (RPG) support for the past three fiscal years.

August 18, 2023

All applications are due by 5:00 PM local time of applicant organization.

Applicants are encouraged to apply early to allow adequate time to make any corrections to errors found in the application during the submission process by the due date.

Not Applicable

It is critical that applicants follow the instructions in the Research (R) Instructions in the SF424 (R&R) Application Guide , except where instructed to do otherwise (in this NOFO or in a Notice from NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts).

Conformance to all requirements (both in the Application Guide and the NOFO) is required and strictly enforced. Applicants must read and follow all application instructions in the Application Guide as well as any program-specific instructions noted in Section IV . When the program-specific instructions deviate from those in the Application Guide, follow the program-specific instructions.

Applications that do not comply with these instructions may be delayed or not accepted for review.

There are several options available to submit your application through Grants.gov to NIH and Department of Health and Human Services partners. You must use one of these submission options to access the application forms for this opportunity.

- Use the NIH ASSIST system to prepare, submit and track your application online.

- Use an institutional system-to-system (S2S) solution to prepare and submit your application to Grants.gov and eRA Commons to track your application. Check with your institutional officials regarding availability.

- Use Grants.gov Workspace to prepare and submit your application and eRA Commons to track your application.

Part 2. Full Text of Announcement

Section i. notice of funding opportunity description.

Purpose: The purpose of the STRONG-RLI Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) is to invite applications to conduct biomedical research capacity needs assessments by Resource-Limited Institutions (RLIs) and then to use the results of the assessments to create action plans for meeting identified needs. The program’s goal is to increase competitiveness in the biomedical research enterprise and foster institutional environments conducive to research career development. Awards are intended to support RLIs in analyzing their institutional research capacity needs and strengths. Resource-Limited Institutions (RLIs) are defined for this NOFO as institutions with a mission to serve historically underrepresented populations in biomedical research that award degrees in the health professions or the sciences related to health, in STEM fields including social and behavioral sciences, and have received an average of $0 to $25 million (total costs) per year of NIH research project grant (RPG) support for the past three fiscal years (as defined in Section III -Eligibility).

Background:

NIH’s ability to help ensure that the nation remains a global leader in scientific discovery and innovation is dependent upon a pool of highly talented scientists from diverse backgrounds who will help to further NIH's mission (see NOT-OD-20-031 ). NIH recognizes the importance of diversity in biomedical, clinical, behavioral, and social sciences (collectively termed "biomedical") research. This includes the diversification of NIH-funded institutions, where researchers with a wide range of skill sets and viewpoints can bring different perspectives, creativity, and individual enterprise to address complex scientific problems.

RLIs, as defined below, play an important role in supporting scientific research, particularly on diseases or conditions that disproportionately impact racial ethnic minority groups and other U.S. populations that experience health disparities. Although these institutions are uniquely positioned to engage underserved populations in research and in the translation of research advances into culturally competent, measurable and sustained improvements in health outcomes, they may benefit from enhancing their capacity to conduct and sustain cutting-edge health-related research.

NIH is committed to assisting RLIs in building institutional research capacity. Scientists at RLIs are critical to advancing knowledge in the biomedical research enterprise. NIH has many programs designed to support researchers at RLIs and broaden the participation of researchers through inclusive excellence across regions, institutions, and demographic groups. The role of RLIs in the nation’s overall competitiveness in research is integrally related to current resources, departmental and disciplinary strengths and capabilities, and campus research support systems and infrastructure. It is critical that RLIs recognize and utilize their research and organizational capabilities so they can leverage existing strengths and develop strategic approaches in areas that require additional attention. Structured needs assessments to examine research and organizational capabilities can offer metrics for short-term/long-term action plans. These assessments will enable institutions to develop benchmarks and action items to increase their competitiveness for NIH, Federal, and other funding opportunities.

RLIs face unique challenges depending on the institution type, resources, infrastructure, and policies as they seek to acquire NIH or other federal agency funding. The areas at RLIs that need to be identified and addressed to reduce the barriers to scientific advancement and increase independent research funding can best be determined by the institution itself. A fundamental principle for organizational development and change is the use of a structured assessment to understand these barriers.

This Funding Opportunity will provide resources to the institutions to 1) conduct the assessment of research infrastructure and other requirements that will enhance administrative and research resources, institutional policies, and expanded opportunities for faculty and students in the biomedical research enterprise; and 2) Use the results of these institutional assessments to develop action plans that will support the conduct of high-quality biomedical research.

Program Objectives:

The purpose of this NIH-wide initiative, STRONG-RLI, is to support research active RLIs to;1. conduct rigorous research capacity needs assessments.2. use the results of the assessments to develop action plans for how to meet the identified needs.

Because of the significant variability in the types of RLIs, two separate categories have been created for this initiative. Please refer to Section III for eligibility criteria for RLIs.

The two categories of research active RLIs are defined in Section III of the NOFO:

1) Low Research Active (LRA) : An RLI that is an undergraduate or graduate degree granting institution and has had less than six million dollars (total costs) in NIH research project grant (RPG) support per year in three of the last five years. In addition, undergraduate granting institutions must have at least 35% of undergraduate students supported by Pell grants.

2) High Research Active (HRA) : An RLI that grants doctoral degrees and has had between six million and 25 million dollars (total costs) in NIH RPG support per year in three of the last five years.

Both LRA and HRA RLIs must have a historical mission to support underrepresented groups in biomedical sciences. Each institution should describe the specific category into which they fit and provide documentation to verify those requirements.

Each RLI will provide details on how they plan to conduct their needs assessments and create/use/adapt/ instruments to study research capacity at the institution. Please note that institutional climate or culture assessment is not a priority for this funding announcement.

As part of the funding announcement , the recipient institutions are expected to use the results of needs assessments to develop action plans for short term and long term goals, to meet the identified needs . Applicants are encouraged to provide detailed approaches for conducting the needs assessment and action plan development. The action plan should include identification of possible sources of funding for increasing research capacity. The implementation of the action plan is beyond the scope of this funding opportunity.

A. Institutional Needs-Assessment for research capacity

NIH recognizes and values the heterogeneity in institutional settings and the students they serve. Applicants must describe their distinctive biomedical research and research training environment and the current services to support them.

Applicants for this needs assessment can use any available tools, or adapt existing tools, to fit their context and needs.

B. Development of Institutional Action Plans

- After completion of the needs assessment, the recipient institutions are expected to develop an action plan. The Institutional Action Plan for research capacity is intended to serve as a roadmap for enhancing the infrastructure and capacity at the applicant institution.

- The outcomes of the needs assessment should determine the capacity building interventions that the institution can undertake to strengthen the institutional framework and research capacity. The Institutional Action Plan that will be developed is expected to be supported by an institutional leader, e.g., the Provost or President (see Letters of Support).

C. Needs assessment topics may include (but are not limited to):

The institution will determine the needs assessment foci but may include broad categories such as administrative/research/student/faculty.

Administrative topics may include -

- Establishing or enhancing the Office of Sponsored Programs (OSP), examining efficiencies and staffing requirements and personnel needs for administrative support

- Available resources for effective business practices, automation, information dissemination, documentation and tracking progress for research activities,

- Process management and process improvement for grant application, grant award, and grant administration.

Research topics may include-

- Research infrastructure may include physical research facilities, lab equipment, and computing resources, core facility for technology, support staff, professional development, laboratories. Appropriate physical research facilities and skilled research support to enable competitiveness.

- Research readiness in areas, such as basic, behavioral or clinical research, grantsmanship support, seminars and workshops for grant writing, for sharing research ideas to enhance knowledge in the field. Potential and current scientific research areas of interest.

- Capacity to conduct Human Subjects Research

- Capacity for Community Engagement research

- Partnerships/ collaboration with other academic institutions, the public sector, and community-based organizations that are sustainable and equitable

Student and faculty topics may include-

- Training needs, Mentoring/Sponsorship, faculty development.

- Student resources for research, support for research experiences, and for post-bac and graduate career progression in biomedical research and in STEM topics

- Research staff recruitment and benefits packages, retention bonuses,

- Faculty teaching workloads that allow time for research pursuits, and department/college-based research staff and administrative support

- Institutional policies for assessment of teaching versus research assignments and support

- Tenure evaluations of faculty services for research, committee, community engagement, etc., protected time for research program development

Technical Assistance Webinar:

NIH will conduct a Technical Assistance Webinar for prospective applicants on July 21st from 2-3.30pm EST. Please join the webinar using the link below:

Join Zoom Meeting https://nih.zoomgov.com/j/1614627302?pwd=RmVXc0RjWjV2WTZsUzd1WmFSWU1NZz09&from=addon Meeting ID: 161 462 7302 Passcode: 919936 One tap mobile +16692545252,,1614627302#,,,,*919936# US (San Jose) +16468287666,,1614627302#,,,,*919936# US (New York)

See Section VIII. Other Information for award authorities and regulations.

Section II. Award Information

Cooperative Agreement: A support mechanism used when there will be substantial Federal scientific or programmatic involvement. Substantial involvement means that, after award, NIH scientific or program staff will assist, guide, coordinate, or participate in project activities. See Section VI.2 for additional information about the substantial involvement for this FOA.

The OER Glossary and the SF424 (R&R) Application Guide provide details on these application types. Only those application types listed here are allowed for this NOFO.

Not Allowed: Only accepting applications that do not propose clinical trials.

Need help determining whether you are doing a clinical trial?

The number of awards is contingent upon NIH appropriations and the submission of a sufficient number of meritorious applications.

Application budgets for direct costs should not exceed $250,000/year.

The scope of the proposed project should determine the project period. The maximum project period is three years

NIH grants policies as described in the NIH Grants Policy Statement will apply to the applications submitted and awards made from this NOFO.

Section III. Eligibility Information

1. Eligible Applicants

Higher Education Institutions

- Public/State Controlled Institutions of Higher Education