Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 10, Issue 12

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and well-being of communities: an exploratory qualitative study protocol

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0180-0213 Anam Shahil Feroz 1 , 2 ,

- Naureen Akber Ali 3 ,

- Noshaba Akber Ali 1 ,

- Ridah Feroz 4 ,

- Salima Nazim Meghani 1 ,

- Sarah Saleem 1

- 1 Community Health Sciences , Aga Khan University , Karachi , Pakistan

- 2 Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation , University of Toronto , Toronto , Ontario , Canada

- 3 School of Nursing and Midwifery , Aga Khan University , Karachi , Pakistan

- 4 Aga Khan University Institute for Educational Development , Karachi , Pakistan

- Correspondence to Ms Anam Shahil Feroz; anam.sahyl{at}gmail.com

Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly resulted in an increased level of anxiety and fear in communities in terms of disease management and infection spread. Due to fear and social stigma linked with COVID-19, many individuals in the community hide their disease and do not access healthcare facilities in a timely manner. In addition, with the widespread use of social media, rumours, myths and inaccurate information about the virus are spreading rapidly, leading to intensified irritability, fearfulness, insomnia, oppositional behaviours and somatic complaints. Considering the relevance of all these factors, we aim to explore the perceptions and attitudes of community members towards COVID-19 and its impact on their daily lives and mental well-being.

Methods and analysis This formative research will employ an exploratory qualitative research design using semistructured interviews and a purposive sampling approach. The data collection methods for this formative research will include indepth interviews with community members. The study will be conducted in the Karimabad Federal B Area and in the Garden (East and West) community settings in Karachi, Pakistan. The community members of these areas have been selected purposively for the interview. Study data will be analysed thematically using NVivo V.12 Plus software.

Ethics and dissemination Ethical approval for this study has been obtained from the Aga Khan University Ethical Review Committee (2020-4825-10599). The results of the study will be disseminated to the scientific community and to the research subjects participating in the study. The findings will help us explore the perceptions and attitudes of different community members towards the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on their daily lives and mental well-being.

- mental health

- public health

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041641

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to last much longer than the physical health impact, and this study is positioned well to explore the perceptions and attitudes of community members towards the pandemic and its impact on their daily lives and mental well-being.

This study will guide the development of context-specific innovative mental health programmes to support communities in the future.

One limitation is that to minimise the risk of infection all study respondents will be interviewed online over Zoom and hence the authors will not have the opportunity to build rapport with the respondents or obtain non-verbal cues during interviews.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected almost 180 countries since it was first detected in Wuhan, China in December 2019. 1 2 The COVID-19 outbreak has been declared a public health emergency of international concern by the WHO. 3 The WHO estimates the global mortality to be about 3.4% 4 ; however, death rates vary between countries and across age groups. 5 In Pakistan, a total of 10 880 cases and 228 deaths due to COVID-19 infection have been reported to date. 6

The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has not only incurred massive challenges to the global supply chains and healthcare systems but also has a detrimental effect on the overall health of individuals. 7 The pandemic has led to lockdowns and has created destructive impact on the societies at large. Most company employees, including daily wage workers, have been prohibited from going to their workplaces or have been asked to work from home, which has caused job-related insecurities and financial crises in the communities. 8 Educational institutions and training centres have also been closed, which resulted in children losing their routine of going to schools, studying and socialising with their peers. Delay in examinations is likewise a huge stressor for students. 8 Alongside this, parents have been struggling with creating a structured milieu for their children. 9 COVID-19 has hindered the normal routine life of every individual, be it children, teenagers, adults or the elderly. The crisis is engendering burden throughout populations and communities, particularly in developing countries such as Pakistan which face major challenges due to fragile healthcare systems and poor economic structures. 10

The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly resulted in an increased level of anxiety and fear in communities in terms of disease management and infection spread. 8 Further, the highly contagious nature of COVID-19 has also escalated confusion, fear and panic among community residents. Moreover, social distancing is often an unpleasant experience for community members and for patients as it adds to mental suffering, particularly in the local setting where get-togethers with friends and families are a major source of entertainment. 9 Recent studies also showed that individuals who are following social distancing rules experience loneliness, causing a substantial level of distress in the form of anxiety, stress, anger, misperception and post-traumatic stress symptoms. 8 11 Separation from family members, loss of autonomy, insecurity over disease status, inadequate supplies, inadequate information, financial loss, frustration, stigma and boredom are all major stressors that can create drastic impact on an individual’s life. 11 Due to fear and social stigma linked with COVID-19, many individuals in the community hide their disease and do not access healthcare facilities in a timely manner. 12 With the widespread use of social media, 13 rumours, myths and inaccurate information about COVID-19 are also spreading rapidly, not only among adults but are also carried on to children, leading to intensified irritability, fearfulness, insomnia, oppositional behaviours and somatic complaints. 9 The psychological symptoms associated with COVID-19 at the community level are also manifested as anxiety-driven panic buying, resulting in exhaustion of resources from the market. 14 Some level of panic also dwells in the community due to the unavailability of essential protective equipment, particularly masks and sanitisers. 15 Similarly, mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, panic attacks, psychotic symptoms and even suicide, were reported during the early severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. 16 17 COVID-19 is likely posing a similar risk throughout the world. 12

The fear of transmitting the disease or a family member falling ill is a probable mental function of human nature, but at some point the psychological fear of the disease generates more anxiety than the disease itself. Therefore, mental health problems are likely to increase among community residents during an epidemic situation. Considering the relevance of all these factors, we aim to explore the perceptions and attitudes towards COVID-19 among community residents and the impact of these perceptions and attitude on their daily lives and mental well-being.

Methods and analysis

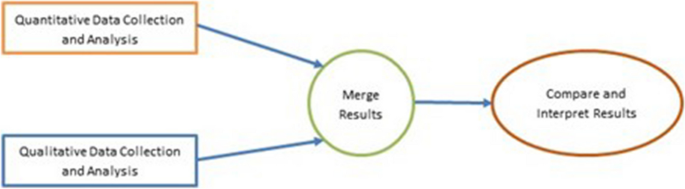

Study design.

This study will employ an exploratory qualitative research design using semistructured interviews and a purposive sampling approach. The data collection methods for this formative research will include indepth interviews (IDIs) with community members. The IDIs aim to explore perceptions of community members towards COVID-19 and its impact on their mental well-being.

Study setting and study participants

The study will be conducted in two communities in Karachi City: Karimabad Federal B Area Block 3 Gulberg Town, and Garden East and Garden West. Karimabad is a neighbourhood in the Karachi Central District of Karachi, Pakistan, situated in the south of Gulberg Town bordering Liaquatabad, Gharibabad and Federal B Area. The population of this neighbourhood is predominantly Ismailis. People living here belong mostly to the middle class to the lower middle class. It is also known for its wholesale market of sports goods and stationery. Garden is an upmarket neighbourhood in the Karachi South District of Karachi, Pakistan, subdivided into two neighbourhoods: Garden East and Garden West. It is the residential area around the Karachi Zoological Gardens; hence, it is popularly known as the ‘Garden’ area. The population of Garden used to be primarily Ismailis and Goan Catholics but has seen an increasing number of Memons, Pashtuns and Baloch. These areas have been selected purposively because the few members of these communities are already known to one of the coinvestigators. The coinvestigator will serve as a gatekeeper for providing entrance to the community for the purpose of this study. Adult community members of different ages and both genders will be interviewed from both sites, as mentioned in table 1 . Interview participants will be selected following the eligibility criteria.

- View inline

Study participants for indepth interviews

IDIs with community members

We will conduct IDIs with community members to explore the perceptions and attitudes of community members towards COVID-19 and its effects on their daily lives and mental well-being. IDI participants will be identified via the community WhatsApp group, and will be invited for an interview via a WhatsApp message or email. Consent will be taken over email or WhatsApp before the interview begins, where they will agree that the interview can be audio-recorded and that written notes can be taken. The interviews will be conducted either in Urdu or in English language, and each interview will last around 40–50 min. Study participants will be assured that their information will remain confidential and that no identifying features will be mentioned on the transcript. The major themes will include a general discussion about participants’ knowledge and perceptions about the COVID-19 pandemic, perceptions on safety measures, and perceived challenges in the current situation and its impact on their mental well-being. We anticipate that 24–30 interviews will be conducted, but we will cease interviews once data saturation has been achieved. Data saturation is the point when no new themes emerge from the additional interviews. Data collection will occur concurrently with data analysis to determine data saturation point. The audio recordings will be transcribed by a transcriptionist within 24 hours of the interviews.

An interview guide for IDIs is shown in online supplemental annex 1 .

Supplemental material

Eligibility criteria.

The following are the criteria for inclusion and exclusion of study participants:

Inclusion criteria

Residents of Garden (East and West) and Karimabad Federal B Area of Karachi who have not contracted the disease.

Exclusion criteria

Those who refuse to participate in the study.

Those who have experienced COVID-19 and are undergoing treatment.

Those who are suspected for COVID-19 and have been isolated/quarantined.

Family members of COVID-19-positive cases.

Data collection procedure

A semistructured interview guide has been developed for community members. The initial questions on the guide will help to explore participants’ perceptions and attitudes towards COVID-19. Additional questions on the guide will assess the impact of these perceptions and attitude on the daily lives and mental health and well-being of community residents. All semistructured interviews will be conducted online via Zoom or WhatsApp. Interviews will be scheduled at the participant’s convenient day and time. Interviews are anticipated to begin on 1 December 2020.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved.

Data analysis

We will transcribe and translate collected data into English language by listening to the audio recordings in order to conduct a thematic analysis. NVivo V.12 Plus software will be used to import, organise and explore data for analysis. Two independent researchers will read the transcripts at various times to develop familiarity and clarification with the data. We will employ an iterative process which will help us to label data and generate new categories to identify emergent themes. The recorded text will be divided into shortened units and labelled as a ‘code’ without losing the main essence of the research study. Subsequently, codes will be analysed and merged into comparable categories. Lastly, the same categories will be grouped into subthemes and final themes. To ensure inter-rater reliability, two independent investigators will perform the coding, category creation and thematic analyses. Discrepancies between the two investigators will be resolved through consensus meetings to reduce researcher bias.

Ethics and dissemination

Study participants will be asked to provide informed, written consent prior to participation in the study. The informed consent form can be submitted by the participant via WhatsApp or email. Participants who are unable to write their names will be asked to provide a thumbprint to symbolise their consent to participate. Ethical approval for this study has been obtained from the Aga Khan University Ethical Review Committee (2020-4825-10599). The study results will be disseminated to the scientific community and to the research subjects participating in the study. The findings will help us explore the perceptions and attitudes of different community members towards the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on their daily lives and mental well-being.

The findings of this study will help us to explore the perceptions and attitudes towards the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the daily lives and mental well-being of individuals in the community. Besides, an indepth understanding of the needs of the community will be identified, which will help us develop context-specific innovative mental health programmes to support communities in the future. The study will provide insights into how communities are managing their lives under such a difficult situation.

- World Health Organization

- Nielsen-Saines K , et al

- Worldometer

- Ebrahim SH ,

- Gozzer E , et al

- Snoswell CL ,

- Harding LE , et al

- Nargis Asad

- van Weel C ,

- Qidwai W , et al

- Brooks SK ,

- Webster RK ,

- Smith LE , et al

- Tripathy S ,

- Kar SK , et al

- Schwartz J ,

- Maunder R ,

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

ASF and NAA are joint first authors.

Contributors ASF and NAA conceived the study. ASF, NAA, RF, NA, SNM and SS contributed to the development of the study design and final protocols for sample selection and interviews. ASF and NAA contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 11 February 2021

Methodological quality of COVID-19 clinical research

- Richard G. Jung ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8570-6736 1 , 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Pietro Di Santo 1 , 2 , 4 , 5 na1 ,

- Cole Clifford 6 ,

- Graeme Prosperi-Porta 7 ,

- Stephanie Skanes 6 ,

- Annie Hung 8 ,

- Simon Parlow 4 ,

- Sarah Visintini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6966-1753 9 ,

- F. Daniel Ramirez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4350-1652 1 , 4 , 10 , 11 ,

- Trevor Simard 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 12 &

- Benjamin Hibbert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0906-1363 2 , 3 , 4

Nature Communications volume 12 , Article number: 943 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

93 Citations

238 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Infectious diseases

- Public health

The COVID-19 pandemic began in early 2020 with major health consequences. While a need to disseminate information to the medical community and general public was paramount, concerns have been raised regarding the scientific rigor in published reports. We performed a systematic review to evaluate the methodological quality of currently available COVID-19 studies compared to historical controls. A total of 9895 titles and abstracts were screened and 686 COVID-19 articles were included in the final analysis. Comparative analysis of COVID-19 to historical articles reveals a shorter time to acceptance (13.0[IQR, 5.0–25.0] days vs. 110.0[IQR, 71.0–156.0] days in COVID-19 and control articles, respectively; p < 0.0001). Furthermore, methodological quality scores are lower in COVID-19 articles across all study designs. COVID-19 clinical studies have a shorter time to publication and have lower methodological quality scores than control studies in the same journal. These studies should be revisited with the emergence of stronger evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Clinical presentations, laboratory and radiological findings, and treatments for 11,028 COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Improving clinical paediatric research and learning from COVID-19: recommendations by the Conect4Children expert advice group

The effect of influenza vaccine in reducing the severity of clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic spread globally in early 2020 with substantial health and economic consequences. This was associated with an exponential increase in scientific publications related to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in order to rapidly elucidate the natural history and identify diagnostic and therapeutic tools 1 .

While a need to rapidly disseminate information to the medical community, governmental agencies, and general public was paramount—major concerns have been raised regarding the scientific rigor in the literature 2 . Poorly conducted studies may originate from failure at any of the four consecutive research stages: (1) choice of research question relevant to patient care, (2) quality of research design 3 , (3) adequacy of publication, and (4) quality of research reports. Furthermore, evidence-based medicine relies on a hierarchy of evidence, ranging from the highest level of randomized controlled trials (RCT) to the lowest level of case series and case reports 4 .

Given the implications for clinical care, policy decision making, and concerns regarding methodological and peer-review standards for COVID-19 research 5 , we performed a formal evaluation of the methodological quality of published COVID-19 literature. Specifically, we undertook a systematic review to identify COVID-19 clinical literature and matched them to historical controls to formally evaluate the following: (1) the methodological quality of COVID-19 studies using established quality tools and checklists, (2) the methodological quality of COVID-19 studies, stratified by median time to acceptance, geographical regions, and journal impact factor and (3) a comparison of COVID-19 methodological quality to matched controls.

Herein, we show that COVID-19 articles are associated with lower methodological quality scores. Moreover, in a matched cohort analysis with control articles from the same journal, we reveal that COVID-19 articles are associated with lower quality scores and shorter time from submission to acceptance. Ultimately, COVID-19 clinical studies should be revisited with the emergence of stronger evidence.

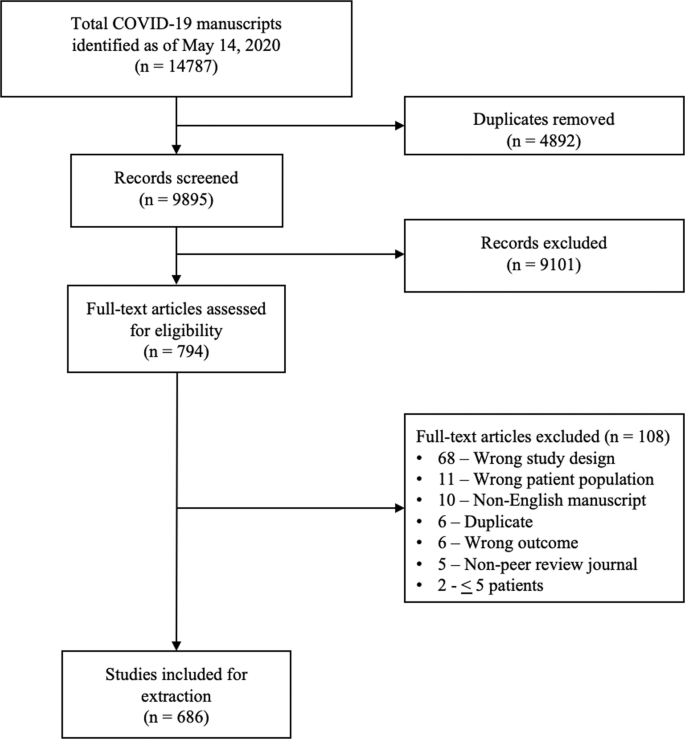

Article selection

A total of 14787 COVID-19 papers were identified as of May 14, 2020 and 4892 duplicate articles were removed. In total, 9895 titles and abstracts were screened, and 9101 articles were excluded due to the study being pre-clinical in nature, case report, case series <5 patients, in a language other than English, reviews (including systematic reviews), study protocols or methods, and other coronavirus variants with an overall inter-rater study inclusion agreement of 96.7% ( κ = 0.81; 95% CI, 0.79–0.83). A total number of 794 full texts were reviewed for eligibility. Over 108 articles were excluded for ineligible study design or publication type (such as letter to the editors, editorials, case reports or case series <5 patients), wrong patient population, non-English language, duplicate articles, wrong outcomes and publication in a non-peer-reviewed journal. Ultimately, 686 articles were identified with an inter-rater agreement of 86.5% ( κ = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.67–0.70) (Fig. 1 ).

A total of 14787 articles were identified and 4892 duplicate articles were removed. Overall, 9895 articles were screened by title and abstract leaving 794 articles for full-text screening. Over 108 articles were excluded, leaving a total of 686 articles that underwent methodological quality assessment.

COVID-19 literature methodological quality

Most studies originated from Asia/Oceania with 469 (68.4%) studies followed by Europe with 139 (20.3%) studies, and the Americas with 78 (11.4%) studies. Of included studies, 380 (55.4%) were case series, 199 (29.0%) were cohort, 63 (9.2%) were diagnostic, 38 (5.5%) were case–control, and 6 (0.9%) were RCTs. Most studies (590, 86.0%) were retrospective in nature, 620 (90.4%) reported the sex of patients, and 7 (2.3%) studies excluding case series calculated their sample size a priori. The method of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis was reported in 558 studies (81.3%) and ethics approval was obtained in 556 studies (81.0%). Finally, journal impact factor of COVID-19 manuscripts was 4.7 (IQR, 2.9–7.6) with a time to acceptance of 13.0 (IQR, 5.0–25.0) days (Table 1 ).

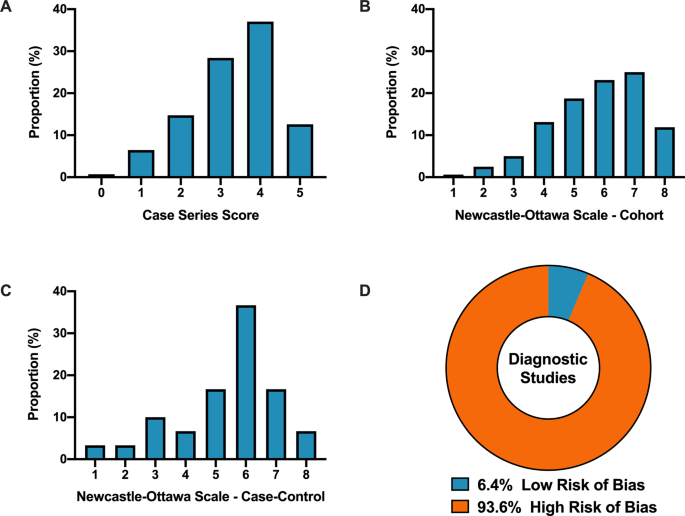

Overall, when COVID-19 articles were stratified by study design, a mean case series score (out of 5) (SD) of 3.3 (1.1), mean NOS cohort study score (out of 8) of 5.8 (1.5), mean NOS case–control study score (out of 8) of 5.5 (1.9), and low bias present in 4 (6.4%) diagnostic studies was observed (Table 2 and Fig. 2 ). Furthermore, in the 6 RCTs in the COVID-19 literature, there was a high risk of bias with little consideration for sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting (Table 2 ).

A Distribution of COVID-19 case series studies scored using the Murad tool ( n = 380). B Distribution of COVID-19 cohort studies scored using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale ( n = 199). C Distribution of COVID-19 case–control studies scored using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale ( n = 38). D Distribution of COVID-19 diagnostic studies scored using the QUADAS-2 tool ( n = 63). In panel D , blue represents low risk of bias and orange represents high risk of bias.

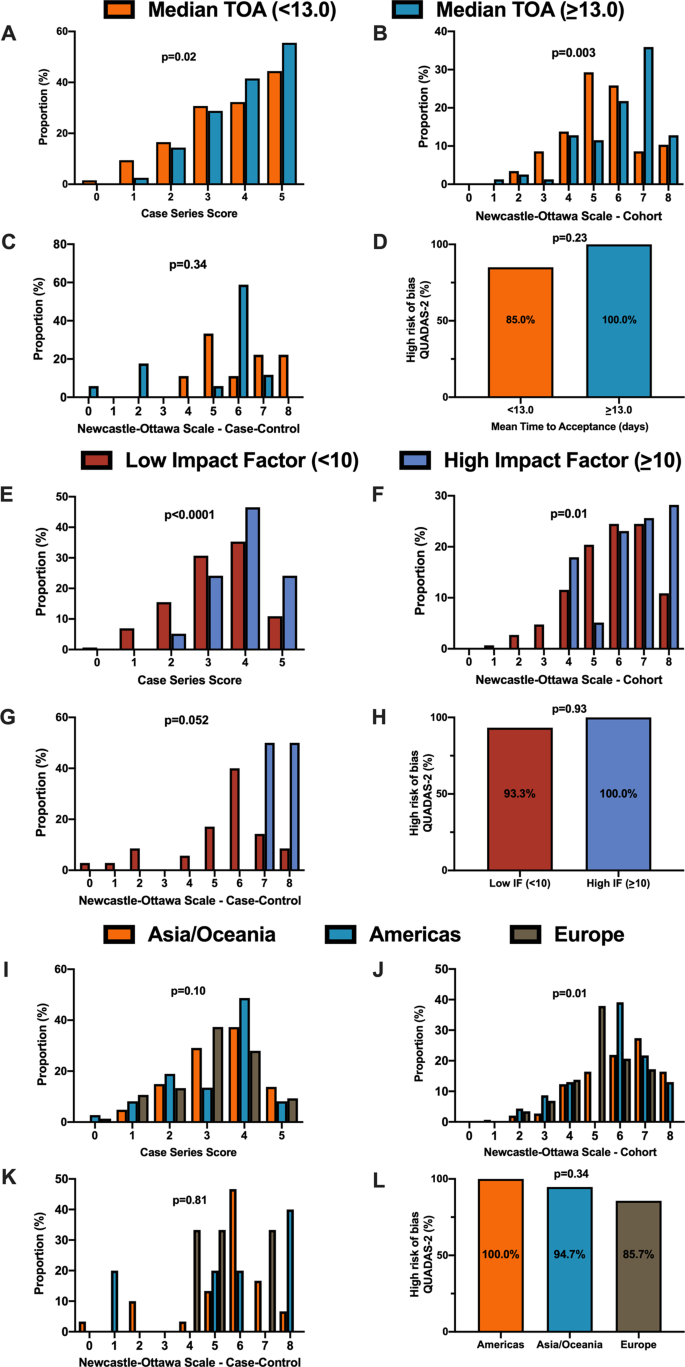

For secondary outcomes, rapid time from submission to acceptance (stratified by median time of acceptance of <13.0 days) was associated with lower methodological quality scores for case series and cohort study designs but not for case–control nor diagnostic studies (Fig. 3A–D ). Low journal impact factor (<10) was associated with lower methodological quality scores for case series, cohort, and case–control designs (Fig. 3E–H ). Finally, studies originating from different geographical regions had no differences in methodological quality scores with the exception of cohort studies (Fig. 3I–L ). When dichotomized by high vs. low methodological quality scores, a similar trend was observed with rapid time from submission to acceptance (34.4% vs. 46.3%, p = 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 1B ), low impact factor journals (<10) was associated with lower methodological quality score (38.8% vs. 68.0%, p < 0.0001, Supplementary Fig. 1C ). Finally, studies originating in either Americas or Asia/Oceania was associated with higher methodological quality scores than Europe (Supplementary Fig. 1D ).

A When stratified by time of acceptance (13.0 days), increased time of acceptance was associated with higher case series score ( n = 186 for <13 days and n = 193 for >=13 days; p = 0.02). B Increased time of acceptance was associated with higher NOS cohort score ( n = 112 for <13 days and n = 144 for >=13 days; p = 0.003). C No difference in time of acceptance and case–control score was observed ( n = 18 for <13 days and n = 27 for >=13 days; p = 0.34). D No difference in time of acceptance and diagnostic risk of bias (QUADAS-2) was observed ( n = 43 for <13 days and n = 33 for >=13 days; p = 0.23). E When stratified by impact factor (IF ≥10), high IF was associated with higher case series score ( n = 466 for low IF and n = 60 for high IF; p < 0.0001). F High IF was associated with higher NOS cohort score ( n = 262 for low IF and n = 68 for high IF; p = 0.01). G No difference in IF and case–control score was observed ( n = 62 for low IF and n = 2 for high IF; p = 0.052). H No difference in IF and QUADAS-2 was observed ( n = 101 for low IF and n = 2 for high IF; p = 0.93). I When stratified by geographical region, no difference in geographical region and case series score was observed ( n = 276 Asia/Oceania, n = 135 Americas, and n = 143 Europe/Africa; p = 0.10). J Geographical region was associated with differences in cohort score ( n = 177 Asia/Oceania, n = 81 Americas, and n = 89 Europe/Africa; p = 0.01). K No difference in geographical region and case–control score was observed ( n = 37 Asia/Oceania, n = 13 Americas, and n = 14 Europe/Africa; p = 0.81). L No difference in geographical region and QUADAS-2 was observed ( n = 49 Asia/Oceania, n = 28 Americas, and n = 28 Europe/Africa; p = 0.34). In panels A – D , orange represents lower median time of acceptance and blue represents high median time of acceptance. In panels E – H , red is low impact factor and blue is high impact factor. In panels I – L , orange represents Asia/Oceania, blue represents Americas, and brown represents Europe. Differences in distributions were analysed by two-sided Kruskal–Wallis test. Differences in diagnostic risk of bias were quantified by Chi-squares test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

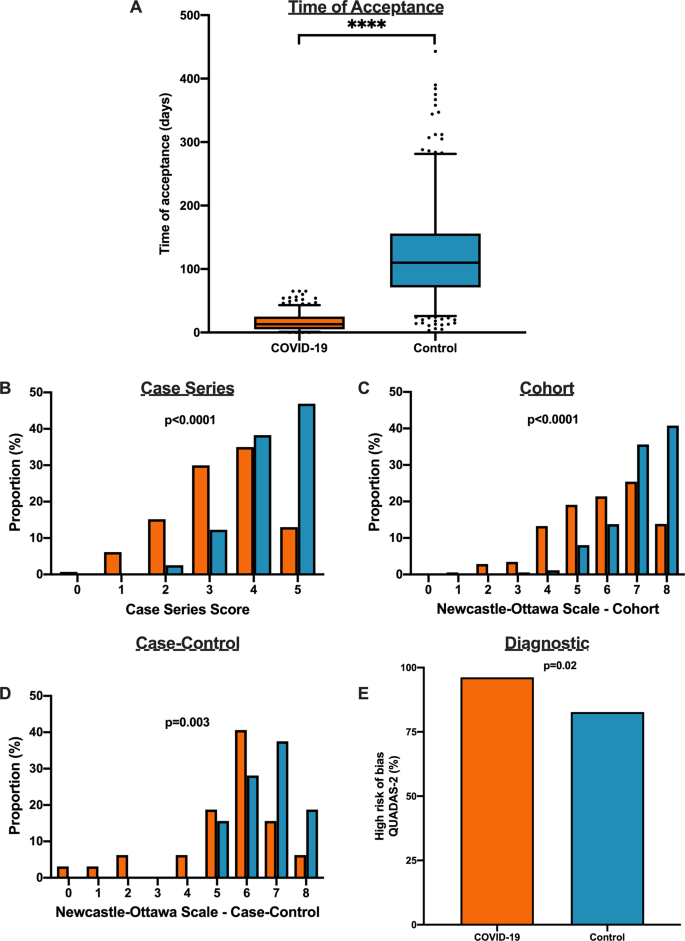

Methodological quality score differences in COVID-19 versus historical control

We matched 539 historical control articles to COVID-19 articles from the same journal with identical study designs in the previous year for a final analysis of 1078 articles (Table 1 ). Overall, 554 (51.4%) case series, 348 (32.3%) cohort, 64 (5.9%) case–control, 106 (9.8%) diagnostic and 6 (0.6%) RCTs were identified from the 1078 total articles. Differences exist between COVID-19 and historical control articles in geographical region of publication, retrospective study design, and sample size calculation (Table 1 ). Time of acceptance was 13.0 (IQR, 5.0–25.0) days in COVID-19 articles vs. 110.0 (IQR, 71.0–156.0) days in control articles (Table 1 and Fig. 4A , p < 0.0001). Case-series methodological quality score was lower in COVID-19 articles compared to the historical control (3.3 (1.1) vs. 4.3 (0.8); n = 554; p < 0.0001; Table 2 and Fig. 4B ). Furthermore, NOS score was lower in COVID-19 cohort studies (5.8 (1.6) vs. 7.1 (1.0); n = 348; p < 0.0001; Table 2 and Fig. 4C ) and case–control studies (5.4 (1.9) vs. 6.6 (1.0); n = 64; p = 0.003; Table 2 and Fig. 4D ). Finally, lower risk of bias in diagnostic studies was in 12 COVID-19 articles (23%; n = 53) compared to 24 control articles (45%; n = 53; p = 0.02; Table 2 and Fig. 4E ). A similar trend was observed between COVID-19 and historical control articles when dichotomized by good vs. low methodological quality scores (Supplementary Fig. 2 ).

A Time to acceptance was reduced in COVID-19 articles compared to control articles (13.0 [IQR, 5.0–25.0] days vs. 110.0 [IQR, 71.0–156.0] days, n = 347 for COVID-19 and n = 414 for controls; p < 0.0001). B When compared to historical control articles, COVID-19 articles were associated with lower case series score ( n = 277 for COVID-19 and n = 277 for controls; p < 0.0001). C COVID-19 articles were associated with lower NOS cohort score compared to historical control articles ( n = 174 for COVID-19 and n = 174 for controls; p < 0.0001). D COVID-19 articles were associated with lower NOS case–control score compared to historical control articles ( n = 32 for COVID-19 and n = 32 for controls; p = 0.003). E COVID-19 articles were associated with higher diagnostic risk of bias (QUADAS-2) compared to historical control articles ( n = 53 for COVID-19 and n = 53 for controls; p = 0.02). For panel A , boxplot captures 5, 25, 50, 75 and 95% from the first to last whisker. Orange represents COVID-19 articles and blue represents control articles. Two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test was conducted to evaluate differences in time to acceptance between COVID-19 and control articles. Differences in study quality scores were evaluated by two-sided Kruskal–Wallis test. Differences in diagnostic risk of bias were quantified by Chi-squares test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In this systematic evaluation of methodological quality, COVID-19 clinical research was primarily observational in nature with modest methodological quality scores. Not only were the study designs low in the hierarchy of scientific evidence, we found that COVID-19 articles were associated with a lower methodological quality scores when published with a shorter time of publication and in lower impact factor journals. Furthermore, in a matched cohort analysis with historical control articles identified from the same journal of the same study design, we demonstrated that COVID-19 articles were associated with lower quality scores and shorter time from submission to acceptance.

The present study demonstrates comparative differences in methodological quality scores between COVID-19 literature and historical control articles. Overall, the accelerated publication of COVID-19 research was associated with lower study quality scores compared to previously published historical control studies. Our research highlights major differences in study quality between COVID-19 and control articles, possibly driven in part by a combination of more thorough editorial and/or peer-review process as suggested by the time to publication, and robust study design with questions which are pertinent for clinicians and patient management 3 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 .

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, we speculate that an urgent need for scientific data to inform clinical, social and economic decisions led to shorter time to publication and explosion in publication of COVID-19 studies in both traditional peer-reviewed journals and preprint servers 1 , 12 . The accelerated scientific process in the COVID-19 pandemic allowed a rapid understanding of natural history of COVID-19 symptomology and prognosis, identification of tools including RT-PCR to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 13 , and identification of potential therapeutic options such as tocilizumab and convalescent plasma which laid the foundation for future RCTs 14 , 15 , 16 . A delay in publication of COVID-19 articles due to a slower peer-review process may potentially delay dissemination of pertinent information against the pandemic. Despite concerns of slow peer review, major landmark trials (i.e. RECOVERY and ACTT-1 trial) 17 , 18 published their findings in preprint servers and media releases to allow for rapid dissemination. Importantly, the data obtained in these initial studies should be revisited as stronger data emerges as lower quality studies may fundamentally risk patient safety, resource allocation and future scientific research 19 .

Unfortunately, poor evidence begets poor clinical decisions 20 . Furthermore, lower quality scientific evidence potentially undermines the public’s trust in science during this time and has been evident through misleading information and high-profile retractions 12 , 21 , 22 , 23 . For example, the benefits of hydroxychloroquine, which were touted early in the pandemic based on limited data, have subsequently failed to be replicated in multiple observational studies and RCTs 5 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 . One poorly designed study combined with rapid publication led to considerable investment of both the scientific and medical community—akin to quinine being sold to the public as a miracle drug during the 1918 Spanish Influenza 31 , 32 . Moreover, as of June 30, 2020, ClinicalTrials.gov listed an astonishing 230 COVID-19 trials with hydroxychloroquine/plaquenil, and a recent living systematic review of observational studies and RCTs of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for COVID-19 demonstrated no evidence of benefit nor harm with concerns of severe methodological flaws in the included studies 33 .

Our study has important limitations. We evaluated the methodological quality of existing studies using established checklists and tools. While it is tempting to associate methodological quality scores with reproducibility or causal inferences of the intervention, it is not possible to ascertain the impact on the study design and conduct of research nor results or conclusions in the identified reports 34 . Second, although the methodological quality scales and checklists used for the manuscript are commonly used for quality assessment in systematic reviews and meta-analyses 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , they can only assess the methodology without consideration for causal language and are prone to limitations 39 , 40 . Other tools such as the ROBINS-I and GRADE exist to evaluate methodological quality of identified manuscripts, although no consensus currently exists for critical appraisal of non-randomized studies 41 , 42 , 43 . Furthermore, other considerations of quality such as sample size calculation, sex reporting or ethics approval are not considered in these quality scores. As such, the quality scores measured using these checklists only reflect the patient selection, comparability, diagnostic reference standard and methods to ascertain the outcome of the study. Third, the 1:1 ratio to identify our historical control articles may affect the precision estimates of our findings. Interestingly, a simulation of an increase from 1:1 to 1:4 control ratio tightened the precision estimates but did not significantly alter the point estimate 44 . Furthermore, the decision for 1:1 ratio in our study exists due to limitations of available historical control articles from the identical journal in the restricted time period combined with a large effect size and sample size in the analysis. Finally, our analysis includes early publications on COVID-19 and there is likely to be an improvement in quality of related studies and study design as the field matures and higher-quality studies. Accordingly, our findings are limited to the early body of research as it pertains to the pandemic and it is likely that over time research quality will improve over time.

In summary, the early body of peer-reviewed COVID-19 literature was composed primarily of observational studies that underwent shorter peer-review evaluation and were associated with lower methodological quality scores than comparable studies. COVID-19 clinical studies should be revisited with the emergence of stronger evidence.

A systematic literature search was conducted on May 14, 2020 (registered on June 3, 2020 at PROSPERO: CRD42020187318) and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Furthermore, the cohort study was reported according to the Strengthening The Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist. The data supporting the findings of this study is available as Supplementary Data 1 – 2 .

Data sources and searches

The search was created in MEDLINE by a medical librarian with expertise in systematic reviews (S.V.) using a combination of key terms and index headings related to COVID-19 and translated to the remaining bibliographic databases (Supplementary Tables 1 – 3 ). The searches were conducted in MEDLINE (Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL 1946–), Embase (Ovid Embase Classic + Embase 1947–) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (from inception). Search results were limited to English-only publications, and a publication date limit of January 1, 2019 to present was applied. In addition, a Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health search filter was applied in MEDLINE and Embase to remove animal studies, and commentary, newspaper article, editorial, letter and note publication types were also eliminated. Search results were exported to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) and duplicates were eliminated using the platform’s duplicate identification feature.

Study selection, data extraction and methodological quality assessment

We included all types of COVID-19 clinical studies, including case series, observational studies, diagnostic studies and RCTs. For diagnostic studies, the reference standard for COVID-19 diagnosis was defined as a nasopharyngeal swab followed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction in order to detect SARS-CoV-2. We excluded studies that were exploratory or pre-clinical in nature (i.e. in vitro or animal studies), case reports or case series of <5 patients, studies published in a language other than English, reviews, methods or protocols, and other coronavirus variants such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome.

The review team consisted of trained research staff with expertise in systematic reviews and one trainee. Title and abstracts were evaluated by two independent reviewers using Covidence and all discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Articles that were selected for full review were independently evaluated by two reviewers for quality assessment using a standardized case report form following the completion of a training period where all reviewers were trained with the original manuscripts which derived the tools or checklists along with examples for what were deemed high scores 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 . Following this, reviewers completed thirty full-text extractions and the two reviewers had to reach consensus and the process was repeated for the remaining manuscripts independently. When two independent reviewers were not able reach consensus, a third reviewer (principal investigator) provided oversight in the process to resolve the conflicted scores.

First and corresponding author names, date of publication, title of manuscript and journal of publication were collected for all included full-text articles. Journal impact factor was obtained from the 2018 InCites Journal Citation Reports from Clarivate Analytics. Submission and acceptance dates were collected in manuscripts when available. Other information such as study type, prospective or retrospective study, sex reporting, sample size calculation, method of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and ethics approval was collected by the authors. Methodological quality assessment was conducted using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for case–control and cohort studies 37 , QUADAS-2 tool for diagnostic studies 38 , Cochrane risk of bias for RCTs 35 and a score derived by Murad et al. for case series studies 36 .

Identification of historical control from identified COVID-19 articles

Following the completion of full-text extraction of COVID-19 articles, we obtained a historical control group by identifying reports matched in a 1:1 fashion. From the eligible COVID-19 article, historical controls were identified by searching the same journal in a systematic fashion by matching the same study design (“case series”, “cohort”, “case control” or “diagnostic”) starting in the journal edition 12 months prior to the COVID-19 article publication on the publisher website (i.e. COVID-19 article published on April 2020, going backwards to April 2019) and proceeding forward (or backward if a specific article type was not identified) in a temporal fashion until the first matched study was identified following abstract screening by two independent reviewers. If no comparison article was found by either reviewers, the corresponding COVID-19 article was excluded from the comparison analysis. Following the identification of the historical control, data extraction and quality assessment was conducted on the identified articles using the standardized case report forms by two independent reviewers and conflicts resolved by consensus. The full dataset has been made available as Supplementary Data 1 – 2 .

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean (SD) or median (IQR) as appropriate, and categorical variables were reported as proportions (%). Continuous variables were compared using Student t -test or Mann–Whitney U-test and categorical variables including quality scores were compared by χ 2 , Fisher’s exact test, or Kruskal–Wallis test.

The primary outcome of interest was to evaluate the methodological quality of COVID-19 clinical literature by study design using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for case–control and cohort studies, QUADAS-2 tool for diagnostic studies 38 , Cochrane risk of bias for RCTs 35 , and a score derived by Murad et al. for case series studies 36 . Pre-specified secondary outcomes were comparison of methodological quality scores of COVID-19 articles by (i) median time to acceptance, (ii) impact factor, (iii) geographical region and (iv) historical comparator. Time of acceptance was defined as the time between submission to acceptance which captures peer review and editorial decisions. Geographical region was stratified into continents including Asia/Oceania, Europe/Africa and Americas (North and South America). Post hoc comparison analysis between COVID-19 and historical control article quality scores were evaluated using Kruskal–Wallis test. Furthermore, good quality of NOS was defined as 3+ on selection and 1+ on comparability, and 2+ on outcome/exposure domains and high-quality case series scores was defined as a score ≥3.5. Due to a small sample size of identified RCTs, they were not included in the comparison analysis.

The finalized dataset was collected on Microsoft Excel v16.44. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. All figures were generated using GraphPad Prism v8 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors can confirm that all relevant data are included in the paper and in Supplementary Data 1 – 2 . The original search was conducted on MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials.

Chen, Q., Allot, A. & Lu, Z. Keep up with the latest coronavirus research. Nature 579 , 193 (2020).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Mahase, E. Covid-19: 146 researchers raise concerns over chloroquine study that halted WHO trial. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2197 (2020).

Chalmers, I. & Glasziou, P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 374 , 86–89 (2009).

Article Google Scholar

Burns, P. B., Rohrich, R. J. & Chung, K. C. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 128 , 305–310 (2011).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Alexander, P. E. et al. COVID-19 coronavirus research has overall low methodological quality thus far: case in point for chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 123 , 120–126 (2020).

Barakat, A. F., Shokr, M., Ibrahim, J., Mandrola, J. & Elgendy, I. Y. Timeline from receipt to online publication of COVID-19 original research articles. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.22.20137653 (2020).

Chan, A.-W. et al. Increasing value and reducing waste: addressing inaccessible research. Lancet 383 , 257–266 (2014).

Ioannidis, J. P. A. et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet 383 , 166–175 (2014).

Chalmers, I. et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet 383 , 156–165 (2014).

Salman, R. A.-S. et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research regulation and management. Lancet 383 , 176–185 (2014).

Glasziou, P. et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet 383 , 267–276 (2014).

Bauchner, H. The rush to publication: an editorial and scientific mistake. JAMA 318 , 1109–1110 (2017).

He, X. et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26 , 672–675 (2020).

Guaraldi, G. et al. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2 , e474–e484 (2020).

Duan, K. et al. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 9490–9496 (2020).

Shen, C. et al. Treatment of 5 critically Ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA 323 , 1582–1589 (2020).

Beigel, J. H. et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19—final report. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 , 1813–1826 (2020).

Group, R. C. et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 (2020).

Ramirez, F. D. et al. Methodological rigor in preclinical cardiovascular studies: targets to enhance reproducibility and promote research translation. Circ. Res 120 , 1916–1926 (2017).

Heneghan, C. et al. Evidence based medicine manifesto for better healthcare. BMJ 357 , j2973 (2017).

Mehra, M. R., Desai, S. S., Ruschitzka, F. & Patel, A. N. RETRACTED: hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without a macrolide for treatment of COVID-19: a multinational registry analysis. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31180-6 (2020).

Servick, K. & Enserink, M. The pandemic’s first major research scandal erupts. Science 368 , 1041–1042 (2020).

Mehra, M. R., Desai, S. S., Kuy, S., Henry, T. D. & Patel, A. N. Retraction: Cardiovascular disease, drug therapy, and mortality in Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 382 , 2582–2582, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2007621. (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Boulware, D. R. et al. A randomized trial of hydroxychloroquine as postexposure prophylaxis for Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 , 517–525 (2020).

Gautret, P. et al. Clinical and microbiological effect of a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in 80 COVID-19 patients with at least a six-day follow up: a pilot observational study. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 34 , 101663–101663 (2020).

Geleris, J. et al. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 382 , 2411–2418 (2020).

Borba, M. G. S. et al. Effect of high vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 3 , e208857–e208857 (2020).

Mercuro, N. J. et al. Risk of QT interval prolongation associated with use of hydroxychloroquine with or without concomitant azithromycin among hospitalized patients testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 5 , 1036–1041 (2020).

Molina, J. M. et al. No evidence of rapid antiviral clearance or clinical benefit with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with severe COVID-19 infection. Médecine et. Maladies Infectieuses 50 , 384 (2020).

Group, R. C. et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med . 383, 2030–2040 (2020).

Shors, T. & McFadden, S. H. 1918 influenza: a Winnebago County, Wisconsin perspective. Clin. Med. Res. 7 , 147–156 (2009).

Stolberg, S. A Mad Scramble to Stock Millions of Malaria Pills, Likely for Nothing (The New York Times, 2020).

Hernandez, A. V., Roman, Y. M., Pasupuleti, V., Barboza, J. J. & White, C. M. Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for treatment or prophylaxis of COVID-19: a living systematic review. Ann. Int. Med. 173 , 287–296 (2020).

Glasziou, P. & Chalmers, I. Research waste is still a scandal—an essay by Paul Glasziou and Iain Chalmers. BMJ 363 , k4645 (2018).

Higgins, J. P. T. et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343 , d5928 (2011).

Murad, M. H., Sultan, S., Haffar, S. & Bazerbachi, F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 23 , 60–63 (2018).

Wells, G. S. B. et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analysis. http://wwwohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxfordasp (2004).

Whiting, P. F. et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 155 , 529–536 (2011).

Sanderson, S., Tatt, I. D. & Higgins, J. P. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int. J. Epidemiol. 36 , 666–676 (2007).

Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25 , 603–605 (2010).

Guyatt, G. et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64 , 383–394 (2011).

Quigley, J. M., Thompson, J. C., Halfpenny, N. J. & Scott, D. A. Critical appraisal of nonrandomized studies-A review of recommended and commonly used tools. J. Evaluation Clin. Pract. 25 , 44–52 (2019).

Sterne, J. A. et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355 , i4919 (2016).

Hamajima, N. et al. Case-control studies: matched controls or all available controls? J. Clin. Epidemiol. 47 , 971–975 (1994).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study received no specific funding or grant from any agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. R.G.J. was supported by the Vanier CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship. F.D.R. was supported by a CIHR Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship and a Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada Detweiler Travelling Fellowship. The funder/sponsor(s) had no role in design and conduct of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Richard G. Jung, Pietro Di Santo.

Authors and Affiliations

CAPITAL Research Group, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Richard G. Jung, Pietro Di Santo, F. Daniel Ramirez & Trevor Simard

Vascular Biology and Experimental Medicine Laboratory, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Richard G. Jung, Pietro Di Santo, Trevor Simard & Benjamin Hibbert

Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Richard G. Jung, Trevor Simard & Benjamin Hibbert

Division of Cardiology, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Pietro Di Santo, Simon Parlow, F. Daniel Ramirez, Trevor Simard & Benjamin Hibbert

School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Pietro Di Santo

Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Cole Clifford & Stephanie Skanes

Department of Medicine, Cumming School of Medicine, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Graeme Prosperi-Porta

Division of Internal Medicine, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Berkman Library, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Sarah Visintini

Hôpital Cardiologique du Haut-Lévêque, CHU Bordeaux, Bordeaux-Pessac, France

F. Daniel Ramirez

L’Institut de Rythmologie et Modélisation Cardiaque (LIRYC), University of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France

Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Trevor Simard

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

R.G.J., P.D.S., S.V., F.D.R., T.S. and B.H. participated in the study conception and design. Data acquisition, analysis and interpretation were performed by R.G.J., P.D.S., C.C., G.P.P., S.P., S.S., A.H., F.D.R., T.S. and B.H. Statistical analysis was performed by R.G.J., P.D.S. and B.H. The manuscript was drafted by R.G.J., P.D.S., F.D.R., T.S. and B.H. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable to all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Benjamin Hibbert .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

B.H. reports funding as a clinical trial investigator from Abbott, Boston Scientific and Edwards Lifesciences outside of the submitted work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications Ian White and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, peer review file, description of additional supplementary files, supplementary data 1, supplementary data 2, reporting summary, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Jung, R.G., Di Santo, P., Clifford, C. et al. Methodological quality of COVID-19 clinical research. Nat Commun 12 , 943 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21220-5

Download citation

Received : 16 July 2020

Accepted : 13 January 2021

Published : 11 February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21220-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Exploring covid-19 research credibility among spanish scientists.

- Eduardo Garcia-Garzon

- Ariadna Angulo-Brunet

- Guido Corradi

Current Psychology (2024)

Primary health care research in COVID-19: analysis of the protocols reviewed by the ethics committee of IDIAPJGol, Catalonia

- Anna Moleras-Serra

- Rosa Morros-Pedros

- Ainhoa Gómez-Lumbreras

BMC Primary Care (2023)

Identifying patterns of reported findings on long-term cardiac complications of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Chenya Zhao

BMC Medicine (2023)

Implications for implementation and adoption of telehealth in developing countries: a systematic review of China’s practices and experiences

- Jiancheng Ye

- Molly Beestrum

npj Digital Medicine (2023)

Neuropsychological deficits in patients with persistent COVID-19 symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Saioa Sobrino-Relaño

- Yolanda Balboa-Bandeira

- Natalia Ojeda

Scientific Reports (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Public decisions about COVID-19 vaccines: A UK-based qualitative study

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations School of Psychology, Swansea University, Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom, Department of Medical Social Sciences, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Manchester Centre for Health Psychology, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, Manchester, United Kingdom, NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations School of Psychology, Swansea University, Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom, Manchester Centre for Health Psychology, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation University of Sussex, School of Psychology, Falmer, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Independent Researcher, Kassel, Germany

- Simon N. Williams,

- Christopher J. Armitage,

- Kimberly Dienes,

- John Drury,

- Published: March 6, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277360

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

To explore UK public decisions around whether or not to get COVID-19 vaccines, and the facilitators and barriers behind participants’ decisions.

This qualitative study consisted of six online focus groups conducted between 15 th March and 22 nd April 2021. Data were analysed using a framework approach.

Focus groups took place via online videoconferencing (Zoom).

Participants

Participants (n = 29) were a diverse group (by ethnicity, age and gender) UK residents aged 18 years and older.

We used the World Health Organization’s vaccine hesitancy continuum model to look for, and explore, three main types of decisions related to COVID-19 vaccines: vaccine acceptance, vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy (or vaccine delay). Two reasons for vaccine delay were identified: delay due to a perceived need for more information and delay until vaccine was “required” in the future. Nine themes were identified: three main facilitators (Vaccination as a social norm; Vaccination as a necessity; Trust in science) and six main barriers (Preference for “natural immunity”; Concerns over possible side effects; Perceived lack of information; Distrust in government;; Conspiracy theories; “Covid echo chambers”) to vaccine uptake.

In order to address vaccine uptake and vaccine hesitancy, it is useful to understand the reasons behind people’s decisions to accept or refuse an offer of a vaccine, and to listen to them and engage with, rather than dismiss, these reasons. Those working in public health or health communication around vaccines, including COVID-19 vaccines, in and beyond the UK, might benefit from incorporating the facilitators and barriers found in this study.

Citation: Williams SN, Armitage CJ, Dienes K, Drury J, Tampe T (2023) Public decisions about COVID-19 vaccines: A UK-based qualitative study. PLoS ONE 18(3): e0277360. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277360

Editor: Mohamed F. Jalloh, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, UNITED STATES

Received: March 22, 2022; Accepted: October 26, 2022; Published: March 6, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Williams et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Ethics was approved by Swansea University’s Department of Psychology Ethics Committee. As part of the ethics review process, participant confidentiality restrictions prohibit the authors from making the data set publicly available. During the consent process, participants were explicitly guaranteed that the data would only be seen my members of the study team. For any discussions about the data set please contact Swansea University’s Research Governance: [email protected] .

Funding: This research was supported by the Manchester Centre for Health Psychology based at the University of Manchester (£2000) and Swansea University’s ‘Greatest Need Fund’ (£3000). This research was supported by the Manchester Centre for Health Psychology based at the University of Manchester (£2000) and Swansea University’s ‘Greatest Need Fund’ (£3000). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: CJA is supported by NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre and NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials. JD sits on SAGE SPI-B subgroup, and Independent Sage. TT currently works for the World Health Organization, but contributed to this paper as an independent researcher. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.” (as detailed online in our guide for authors http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/competing-interests The authors have no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy is a complex and multifaceted problem, and one that is influenced by a range of contextual (e.g. historical, institutional, political) factors, as well as individual-level and vaccine specific factors (e.g. costs or design of a given vaccination program) [ 1 ]. Individual-level factors, include health-system and providers, knowledge and beliefs about health and prevention, personal perceptions about risk versus benefit and personal and family experiences with vaccination (including pain and side effects from past vaccines) [ 1 , 2 ]. Although they are shaped by contextual factors, this research is primarily interested in individual perceptions of UK residents around the decision to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

Vaccine hesitancy can be defined as “the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services” [ 2 ]. In this paper, we draw on The World Health Organization’s (WHO) SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy’s ‘continuum of vaccine hesitancy’ model, which sees vaccine views to be set on a continuum between full acceptance of vaccines with no doubts, through to complete refusal with no doubts [ 1 , 2 ]. Vaccine hesitancy is seen as a heterogenous group in-between these diametric positions, including those who “delay” acceptance (i.e. do not get it when first offered or according to schedule).

Although the WHO continuum of vaccine hesitancy is a simple and useful heuristic to categorise individuals, especially in relation to individual-level perceptions or attitudes, it is important to acknowledge that these attitudes do not occur in a vacuum but are shaped and influenced by many social and contextual factors. Intentions and decisions around vaccine acceptance or refusal, and the reasons behind them, can also be understood in terms of the ‘5 C’s’ model of vaccine hesitancy. This model suggests that vaccine hesitancy is influenced by: Complacency —for example where the perceived risk of harm from the disease is low; convenience —for example where there are practical or logistical barriers to access vaccination; confidence —for example where there is a lack of trust in the safety or efficacy of the vaccine; communication –for example where misinformation can create distrust or confusion; and, context –for example certain social groups, including some ethnic minority communities might encounter additional barriers, including structural racism, which might affect vaccine uptake [ 1 , 3 ]. Another theoretical framework is the Behavioural and Social Drivers (BeSD) of vaccine uptake [ 4 ]. The BEsD framework suggests four main drivers of vaccination uptake: (1) people’s mental and emotional responses to vaccines ( thinking and feeling ); (2) social or group norms around vaccinations ( social processes ); (3) people’s willingness and intentions, or hesitancy, to get vaccinated ( motivation ); (4) contextual or structural barriers related to e.g costs or access ( practical issues ) [ 4 ]. It is important to note the inter-relatedness of the many drivers of vaccine acceptance or hesitancy. As such, a focus on individual level decisions or intentions around vaccines, as is the case in this study, needs to acknowledge the ways in which individual feelings, beliefs and motivations, are shaped by (and serve to shape) contextual and practical issues.

In terms of the reasons behind vaccine intentions and decisions, survey data on COVID-19 vaccine intentions and decisions suggests that most common reasons for vaccine hesitancy include: worries over side effects, worries over long term effects on health, as well as concerns over its efficacy [ 5 ]. Qualitative research on public views on COVID-19 vaccines is emerging. One study, from the UK, found that vaccine hesitancy was associated with three main factors: safety concerns, negative stories and personal knowledge, with those who were most confused, worried and mistrusting being the most hesitant [ 6 ]. Another study, from Canada, on overall attitudes to public health measures to reduce COVID-19 transmission found that many participants felt that vaccines were a means to “get back to normal life” while some were hesitant due to a lack of confidence in the potential efficacy of the vaccine and concerns over side-effects [ 7 ]. A study from Australia, with hesitant health or social care workers or clinically vulnerable adults, found that participants saw vaccination as beneficial for both individual and community protection, but also expressed safety concerns that made them feel like “guinea pigs” [ 8 ].

Ongoing research into vaccine hesitancy is needed to follow how attitudes and decisions around COVID-19 vaccines may be changing as the pandemic continues. Also, qualitative data can explore, in depth, the reasons behind why people are deciding to get vaccinated or not. In this paper, we explore participants’ decisions on COVID-19 vaccines in the UK during March and April 2021. For context, during this period the UK was experiencing a rapid roll out of COVID-19 vaccines (Astra Zeneca and Pfizer-BioNTech) via the National Health Service, with between January and 22nd April 2021, administered approximately 35 million total doses, with approximately 60% of the total population aged 16 and over having received at least one dose with doses being prioritised amongst older adults and those with certain underlying health conditions (clinically vulnerable and clinically extremely vulnerable adults) [ 9 ].

This paper explores participants’ intentions and decisions around whether or not to get vaccinated, and specifically the reasons behind them, thereby contributing to our understanding of the facilitators and barriers to vaccine uptake.

Materials and methods

Participants and data collection.

Data from this study came from the COVID Public Views (PVCOVID) study–a mixed-methods study using panel focus groups and surveys during the pandemic (commenced March 2020) [ 10 , 11 ]. Participants for the PVCOVID study were initially recruited to the study from March-July 2020, with a total of 53 participants initially enrolling into the study. Participants were all UK-based adults aged 18 years or older. Recruitment for the study took place primarily via non-probability, opportunity sampling. Recruitment included using social media advertising (Facebook ads and via posting ads on Twitter), other online advertising (e.g. online ‘free-ads’ such as Gumtree), as well as snowball sampling (e.g. asking participants who had taken part in a focus group to distribute the study ad to others they felt might be interested in participating). Recruitment sought as diverse a range of ages, genders, race/ethnicities, UK locations, and social backgrounds as possible (e.g. advertisements encouraged expressions of interest from individuals from Black and Asian Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds; social media ads were designed to targeted users from across the UK and a wide age range). Although the study had a low number of individuals from older age groups (over 50 years of age) the over-representation of younger adults could be seen as beneficial because of their lower vaccination coverage [ 9 ].

Here we report on data from six online focus groups with 29 participants from within the overall PVCOVID study. Focus groups were not arranged according to any pre-existing views or decisions around vaccinations (i.e. we did not purposefully put those who were not intending on getting vaccinated in the same group for example). This was largely because of the longitudinal nature of the overall study, and our initial decision to try to keep the membership of each focus group the same over time in order to build rapport, familiarity and openness within the groups (we did not collect data on vaccine views during the initial recruitment and group allocation in March 2020). Each group contained a mixture of those who had already received at least one vaccine (n = 15) and those who had either already refused a vaccine or who were delaying their decision to get a vaccine (n = 14). One potential limitation of this focus group composition was that those who were refusing or delaying vaccination might have felt less comfortable expressing their opinion (since, generally getting vaccinated was seen by many as a social norm—see below). However, the focus group facilitator sought to ensure that all participants felt comfortable expressing their views, and that dialogue within the group was not hostile and as respectful and open as possible. Also, questions were phrased in non-leading, non-judgemental a way as possible.

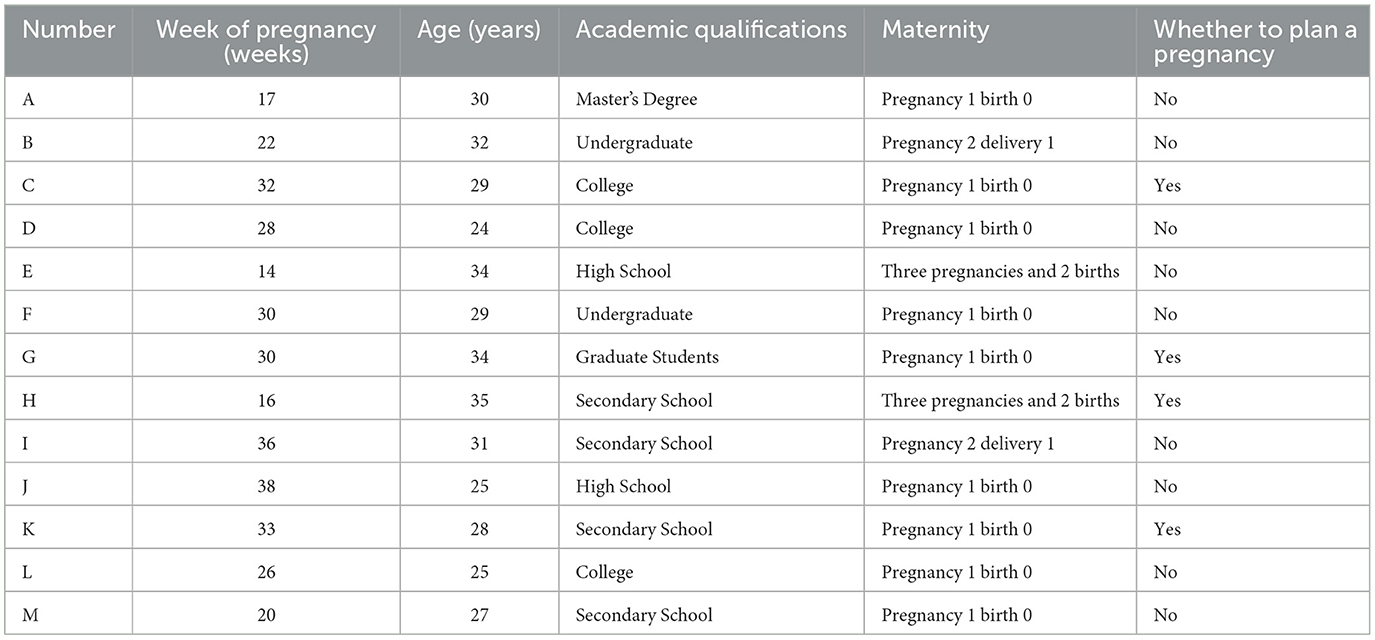

In March 2021, participants were invited to take part in a rapid round of focus groups on the topic of vaccines. Participants took part in focus groups conducted between 15th March and 22nd April 2021. Further information about the participants discussed in the present paper are presented in Table 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277360.t001

Online focus groups were necessary due to COVID-19 social distancing regulations, but have been seen to have benefits in general, as a means of eliciting public views from diverse and geographically dispersed participants [ 12 , 13 ]. Each focus group (of 4–6 participants) met virtually via the videoconferencing platform Zoom for approximately one hour. All focus groups discussed in the present paper were moderated by SW. Focus groups were recoded and transcribed. The topic guide for the focus groups (Appendix 1) was initially developed using existing literature on vaccination public attitudes and vaccine hesitancy discussed above, as well as rapidly emerging surveys on public attitudes to COVID-19 public attitudes.

Ethical approval was received by Swansea University’s School of Management Research Ethics Committee and Swansea University’s Department of Psychology Ethics Committee (Ref: 2020-4952-3957). All participants gave informed consent, both written and verbal. All data were kept securely and confidentially in line with ethical requirements, and where data is presented below, all quotes are anonymised to protect participants’ identities.

Data were analysed in accordance with a Framework Analysis (FA) approach [ 14 ]. FA is a flexible approach that is not aligned with a particular epistemological, philosophical or theoretical tradition. It can be either primarily inductive or deductive (or a combination thereof) and can be adapted with many qualitative approaches with the main aim being to generate themes [ 14 ]. Our use of FA combined elements of both induction and deduction in an abductive approach [ 15 , 16 ], whereby the researchers inductively coded for emergent facilitators and barriers to vaccine uptake as they emerged. The coding process was also broadly informed deductively by existing literature, including the WHO’s ‘continuum of vaccine hesitancy’ framework. Using the vaccine hesitancy continuum model [ 1 ], we analysed data to look for, and explore, three main types of vaccine decisions in the data: those who had accepted, or were planning on accepting, the vaccine; those who had refused, or were planning on refusing, the vaccine; and those who had not yet decided, or were delaying the decision of, whether or not to get the vaccine. As such, each participant was coded into one of these three main categories based on their decision or intention (e.g. statements that indicated they were not sure if they wanted a vaccine were coded into three main categories: accept, delay, refuse. Sub-coding sought to bring out the nuances within these simplified intention/decision types (e.g. “accept but unsure”). Inductive analysis was used to explore facilitators and barriers to vaccine acceptance (i.e. the reasons why people were getting or intending on accepting or refusing a vaccine or why they were unsure of or delaying their decision).