- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Applied Linguistics

- Biology of Language

- Cognitive Science

- Computational Linguistics

- Historical Linguistics

- History of Linguistics

- Language Families/Areas/Contact

- Linguistic Theories

- Neurolinguistics

- Phonetics/Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sign Languages

- Sociolinguistics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Language shift.

- Lenore A. Grenoble Lenore A. Grenoble The University of Chicago, Department of Linguistics

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.347

- Published online: 25 March 2021

Language shift occurs when a community of users replaces one language by another, or “shifts” to that other language. Although language shift can and does occur at the level of the individual speaker, it is shift at the level of an entire community that is associated with widespread language replacement and loss. Shift is a particular kind of language loss, and differs from language attrition, which involves the loss of a language over an individual’s lifetime, often the result of aging or of language replacement (as in shift). Both language shift and attrition are in contrast to language maintenance, the continuing use of a language. Language maintenance and revitalization programs are responses to language shift, and are undertaken by communites who perceive that their language is threatened by a decrease in usage and under threat of loss.

Language shift is widespread and can be found with majority- or minority-language populations. It is often associated with immigrant groups who take up the majority language of their new territory, leaving behind the language of their homeland. For minority-language speaker communities, language shift is generally the result of a combination of factors, in particular colonization. A nexus of factors—historical, political, social, and economic—often provides the impetus for a community to ceasing speaking their ancestral language, replacing it with the language of the majority, and usually politically dominant, group. Language shift is thus a social issue, and often coupled with other indicators of social distress.

Language endangerment is the result of language shift, and in fact shift is its most widespread cause.Since the 1960s there has been ever-increasing interest across speaker communities and linguists to work to provide opportunities to learn and use minority languages to offset shift, and to document speakers in communities under the threat of shift.

- contact linguistics

- linguistic diversity

- language endangerment

- documentation

- revitalization

- historical linguistics

- heritage languages

- ecological linguistics

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Linguistics. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 17 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.41]

- 185.80.151.41

Character limit 500 /500

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Language Shift

Introduction, general theory and background.

- Diversity in Itself

- Language Spread

- Difference of the Modern Era from the Past

- Special Effects of Empires

- Pre-Historic

- Deliberate Replacement

- Attempted Reversal

- Practical Revitalization

- Language Documentation

- Aspects of Language Endangerment

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Comparative-Historical Linguistics

- Critical Applied Linguistics

- Cross-Cultural Pragmatics

- Endangered Languages

- First Language Attrition

- Formulaic Language

- Francoprovençal

- Language Contact

- Language Geography

- Language Ideologies and Language Attitudes

- Language Maintenance

- Language Nests

- Language Policy and Planning

- Language Revitalization

- Language Standardization

- Linguistic Landscapes

- Old English

- Positive Discourse Analysis

- Second-Language Reading

- Semantic-Pragmatic Change

- Sentence Processing in Monolingual and Bilingual Speakers

- Structural Borrowing

- Variationist Sociolinguistics

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Cognitive Grammar

- Edward Sapir

- Teaching Pragmatics

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Language Shift by Nicholas Ostler LAST REVIEWED: 30 August 2022 LAST MODIFIED: 29 May 2014 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0193

In this article, “language shift” means the process, or the event, in which a population changes from using one language to another. As such, recognition of it depends on being able to see the prior and subsequent language as distinct; and therefore the term excludes language change which can be seen as evolution, the transition from older to newer forms of the same language. (For this latter topic, seek references in “Historical, or Diachronic, Linguistics.”) Language shift is a social phenomenon, whereby one language replaces another in a given (continuing) society. It is due to underlying changes in the composition and aspirations of the society, which goes from speaking the old to the new language. By definition, it is not a structural change caused by the dynamics of the old language as a system. The new language is adopted as a result of contact with another language community, and so it is usually possible to identify the new language as “the same” as, that is, a descendant of, a language spoken somewhere else, even if the new language has some new, perhaps unprecedented, properties on the lips of the population that is adopting it. Language shift results in the spread of the new language that is adopted, and may result in the endangerment or loss of the old language, some or all of whose speakers are changing their allegiance. As a result, some readings on language spread and endangerment are relevant to language shift. Language shift may be an object of conscious policy; but equally it may be a phenomenon which is unplanned, and often unexplained. Consequently, readings in language policy (especially those on status planning) often relate to it. The conditions of imperial relations between societies, and the special links mediated nowadays by technological inventions, often worldwide and at a particularly rapid pace, are thought by some to require special theories.

Language shift is a dynamic phenomenon of social change, and is therefore a topic of sociolinguistics. There is no general theory of its causation that is universally accepted. Ostler 2011 sets it within a general framework of change in language-using populations. Wendel and Heinrich 2012 gives a framework for kinds of shift, as well as a useful bibliography of past seminal works. Thomason and Kaufman 1988 considers the effects on the corpus of a language that may result from shift, among other language-contact phenomena. Mackey 2001 begins the search for universals that apply in the relative propensity and speed of languages to shift. Barreña, et al. 2007 discusses possible criteria that may indicate impending shift. Bonfil Batalla 1996 outlines a theory of cultural control which bids to explain the linguistic transition. Mufwene 2008 places language shift (as well as language competition and globalization) within a more general context of language ecology.

Barreña, A., E. Amorrortu, A. Ortega, B. Uranga, E. Izagirre, and I. Idiazabal. 2007. Does the number of speakers of a language determine its fate? International Journal of the Sociology of Language 186:125–139.

The authors show that the number of speakers cannot be considered the most important criterion in trying to anticipate language survival or death. Instead, natural transmission and intergenerational use are indicated.

Bonfil Batalla, G. 1996. La teoría del control cultural en el estudio de los procesos étnicos. Acta sociológica 18:11–54.

The background to language shift is theorized in terms of a theory of cultural control, whereby a social group becomes alienated and accepting of external institutions.

Mackey, W. F. 2001. The ecology of language shift. In The ecolinguistics reader: Language, ecology, and environment . Edited by Alwin Fill and Peter Mühlhäusler, 67–74. London and New York: Continuum.

Offers some recent evidence (e.g., in Quebec) for languages more closely related genetically to yield to one another, but different genetic types to act as a buffer on shift.

Mufwene, Salikoko. 2008. Language evolution: Contact, competition and change . London and New York: Continuum.

A general view of the dynamic relation of languages, changing and expanding at one another’s expense among human populations.

Ostler, Nicholas. 2011. Language maintenance, shift and endangerment. In Cambridge handbook of sociolinguistics . Edited by Raj Mesthrie and Walt Wolfram, 315–334. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511997068

There are three major issues addressed: how a new language can come on the scene; how the rising generation can come to learn it; and what determines when the result is language replacement, and when bilingualism.

Thomason, Sarah, and Terrence Kaufman. 1988. Language contact, creolization, and genetic linguistics . Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

The effects of shift (where a whole language has been replaced, with various degrees of imperfect learning of the new language) are principally compared with those of borrowing (where only new lexis, morphology, or constructions are absorbed into the old language).

Wendel, J., and P. Heinrich. 2012. A framework for language endangerment dynamics: The effects of contact and social change on language ecologies and language diversity. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 218:145–166.

This framework distinguishes replacement (which involves elimination of a distinct community) from shift (which involves long-term language change, typically with smaller languages giving place to larger ones).

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Linguistics »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Acceptability Judgments

- Acquisition, Second Language, and Bilingualism, Psycholin...

- Adpositions

- African Linguistics

- Afroasiatic Languages

- Algonquian Linguistics

- Altaic Languages

- Ambiguity, Lexical

- Analogy in Language and Linguistics

- Animal Communication

- Applicatives

- Applied Linguistics, Critical

- Arawak Languages

- Argument Structure

- Artificial Languages

- Australian Languages

- Austronesian Linguistics

- Auxiliaries

- Balkans, The Languages of the

- Baudouin de Courtenay, Jan

- Berber Languages and Linguistics

- Bilingualism and Multilingualism

- Biology of Language

- Borrowing, Structural

- Caddoan Languages

- Caucasian Languages

- Celtic Languages

- Celtic Mutations

- Chomsky, Noam

- Chumashan Languages

- Classifiers

- Clauses, Relative

- Clinical Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Colonial Place Names

- Comparative Reconstruction in Linguistics

- Complementation

- Complexity, Linguistic

- Compositionality

- Compounding

- Computational Linguistics

- Conditionals

- Conjunctions

- Connectionism

- Consonant Epenthesis

- Constructions, Verb-Particle

- Contrastive Analysis in Linguistics

- Conversation Analysis

- Conversation, Maxims of

- Conversational Implicature

- Cooperative Principle

- Coordination

- Creoles, Grammatical Categories in

- Critical Periods

- Cross-Language Speech Perception and Production

- Cyberpragmatics

- Default Semantics

- Definiteness

- Dementia and Language

- Dene (Athabaskan) Languages

- Dené-Yeniseian Hypothesis, The

- Dependencies

- Dependencies, Long Distance

- Derivational Morphology

- Determiners

- Dialectology

- Distinctive Features

- Dravidian Languages

- English as a Lingua Franca

- English, Early Modern

- English, Old

- Eskimo-Aleut

- Euphemisms and Dysphemisms

- Evidentials

- Exemplar-Based Models in Linguistics

- Existential

- Existential Wh-Constructions

- Experimental Linguistics

- Fieldwork, Sociolinguistic

- Finite State Languages

- French Grammars

- Gabelentz, Georg von der

- Genealogical Classification

- Generative Syntax

- Genetics and Language

- Grammar, Categorial

- Grammar, Construction

- Grammar, Descriptive

- Grammar, Functional Discourse

- Grammars, Phrase Structure

- Grammaticalization

- Harris, Zellig

- Heritage Languages

- History of Linguistics

- History of the English Language

- Hmong-Mien Languages

- Hokan Languages

- Humor in Language

- Hungarian Vowel Harmony

- Idiom and Phraseology

- Imperatives

- Indefiniteness

- Indo-European Etymology

- Inflected Infinitives

- Information Structure

- Interface Between Phonology and Phonetics

- Interjections

- Iroquoian Languages

- Isolates, Language

- Jakobson, Roman

- Japanese Word Accent

- Jones, Daniel

- Juncture and Boundary

- Khoisan Languages

- Kiowa-Tanoan Languages

- Kra-Dai Languages

- Labov, William

- Language Acquisition

- Language and Law

- Language, Embodiment and

- Language for Specific Purposes/Specialized Communication

- Language, Gender, and Sexuality

- Language in Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Language Shift

- Language, Synesthesia and

- Languages of Africa

- Languages of the Americas, Indigenous

- Languages of the World

- Learnability

- Lexical Access, Cognitive Mechanisms for

- Lexical Semantics

- Lexical-Functional Grammar

- Lexicography

- Lexicography, Bilingual

- Linguistic Accommodation

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Areas

- Linguistic Prescriptivism

- Linguistic Profiling and Language-Based Discrimination

- Linguistic Relativity

- Linguistics, Educational

- Listening, Second Language

- Literature and Linguistics

- Machine Translation

- Maintenance, Language

- Mande Languages

- Mass-Count Distinction

- Mathematical Linguistics

- Mayan Languages

- Mental Health Disorders, Language in

- Mental Lexicon, The

- Mesoamerican Languages

- Minority Languages

- Mixed Languages

- Mixe-Zoquean Languages

- Modification

- Mon-Khmer Languages

- Morphological Change

- Morphology, Blending in

- Morphology, Subtractive

- Munda Languages

- Muskogean Languages

- Nasals and Nasalization

- Niger-Congo Languages

- Non-Pama-Nyungan Languages

- Northeast Caucasian Languages

- Oceanic Languages

- Papuan Languages

- Penutian Languages

- Philosophy of Language

- Phonetics, Acoustic

- Phonetics, Articulatory

- Phonological Research, Psycholinguistic Methodology in

- Phonology, Computational

- Phonology, Early Child

- Policy and Planning, Language

- Politeness in Language

- Possessives, Acquisition of

- Pragmatics, Acquisition of

- Pragmatics, Cognitive

- Pragmatics, Computational

- Pragmatics, Cross-Cultural

- Pragmatics, Developmental

- Pragmatics, Experimental

- Pragmatics, Game Theory in

- Pragmatics, Historical

- Pragmatics, Institutional

- Pragmatics, Second Language

- Prague Linguistic Circle, The

- Presupposition

- Psycholinguistics

- Quechuan and Aymaran Languages

- Reading, Second-Language

- Reciprocals

- Reduplication

- Reflexives and Reflexivity

- Register and Register Variation

- Relevance Theory

- Representation and Processing of Multi-Word Expressions in...

- Salish Languages

- Sapir, Edward

- Saussure, Ferdinand de

- Second Language Acquisition, Anaphora Resolution in

- Semantic Maps

- Semantic Roles

- Semantics, Cognitive

- Sign Language Linguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociolinguistics, Variationist

- Sociopragmatics

- Sound Change

- South American Indian Languages

- Specific Language Impairment

- Speech, Deceptive

- Speech Perception

- Speech Production

- Speech Synthesis

- Switch-Reference

- Syntactic Change

- Syntactic Knowledge, Children’s Acquisition of

- Tense, Aspect, and Mood

- Text Mining

- Tone Sandhi

- Transcription

- Transitivity and Voice

- Translanguaging

- Translation

- Trubetzkoy, Nikolai

- Tucanoan Languages

- Tupian Languages

- Usage-Based Linguistics

- Uto-Aztecan Languages

- Valency Theory

- Verbs, Serial

- Vocabulary, Second Language

- Voice and Voice Quality

- Vowel Harmony

- Whitney, William Dwight

- Word Classes

- Word Formation in Japanese

- Word Recognition, Spoken

- Word Recognition, Visual

- Word Stress

- Writing, Second Language

- Writing Systems

- Zapotecan Languages

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.41]

- 185.80.151.41

- Open access

- Published: 22 August 2018

Language shift: analysing language use in multilingual classroom interactions

- Harni Kartika-Ningsih ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3658-7558 1 , 2 &

- David Rose 3

Functional Linguistics volume 5 , Article number: 9 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

9 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper offers a framework and set of tools for analysing the use of language shift in multilingual classroom discourse. The term language shift refers to the use of multiple languages in all types of interactions, including teaching and learning. The analysis was developed in the context of an action research project in Indonesian schools. It includes three components: a framework for mapping teaching approaches in multilingual classrooms; an analysis of pedagogic interactions, showing the structures of language shift within and between speaker roles; and an analysis of the pedagogic functions of language shift, as lessons and teacher/learner interactions unfold. The theoretical foundation for the analysis is the model of language as text-in-context developed in systemic functional linguistics.

Multilingualism in communities and schools

In multilingual communities, switching from one language to another takes place on a daily basis, so members are likely to speak more than one language. In Indonesia, three major language sectors are part of everyday life for many speakers, including the national language, Bahasa Indonesia, regional languages, such as Javanese or Sundanese, and foreign languages, such as English and Arabic (Sneddon, 2003 ; Montolalu & Suryadinata, 2007 ). A Sundanese speaker, for example, who resides in Bandung, a Sundanese speaking area in West Java, speaks Sundanese with their peers. If a peer speaks Indonesian, Bahasa Indonesia can also be a part in the conversation. Additionally, if both of them speak English, that may also be a part of the conversation.

Author Harni Kartika-Ningsih is an example of such multilingualism. As a Javanese heritage speaker who was born and raised in Bandung, Harni learnt to speak both Javanese and Sundanese in family and community settings. From her schooling experience, she learned to speak Indonesian and English. She often uses Javanese and Indonesian with family members. When she talks to school friends who are Sundanese, they are likely to speak in Indonesian and Sundanese at the same time, with a few lexical items of English as well. In general, the more languages that interlocutors share in Indonesia, the more languages will be deployed in the exchange, regardless of their ethnic background. Such free code-switching or mixing of languages occurs in many multilingual societies where languages are in contact.

In multilingual communities, language mixing is also a common practice in more formal institutional settings such as classrooms. In Indonesian classrooms, teachers and students regularly actualize their multilingual repertoire during teaching and learning. However, despite being the norm in everyday life of multilingual communities, and studies showing its benefits and functions in teaching and learning, code-switching in language learning classrooms remains a hotly debated topic worldwide.

Aim and structure of this paper

To help inform this debate, this paper offers a model for analysing the structures and functions of language use in multilingual classrooms. Multilingual interactions in classroom discourse are described here as language shift. Footnote 1 Language shift is the process of meaning making realized in two or more languages. This includes ‘translating’ or bringing equivalence from L1 to L2, as well as ‘code-switching/mixing’, or using two or more languages in spoken discourse.

The analysis in this paper can be applied to empirically describe precisely how and why language shift is used in pedagogic settings. The aim of the analysis is to develop a set of systematic principles towards design of effective bilingual teaching and learning. The language shift analysis model includes three major components. The first component is a framework for identifying types of L2 language teaching approaches along two axes: the degree to which they favour L2 or L1 as the language of instruction, and their focus on language or curriculum content as the primary learning goal. This is a topological framework on which various approaches can be located and compared (following Bernstein, 2000 ; Martin & Rose, 2008 ; Maton, 2013 ). The second is a description of the structuring of language shift in teaching/learning interactions. Pedagogic interactions are analysed in terms of the roles of speakers, and the moves they make in exchanges. This analysis deploys the tools of exchange structure theory (Martin, 1992 ; Martin & Rose 2007 ). We show that language shift may occur from role to role, from move to move, and within moves. The third component is an analysis of the pedagogic functions of such language shift in multilingual classrooms. For example, L1 may be used by teachers to scaffold learning tasks, or to engage students in the learning activity. The use of L1 for such functions may give way to L2 as students’ L2 knowledge and confidence grows. This analysis uses the tools of pedagogic register analysis (Rose, 2014 , 2018a ; Rose & Martin, 2012 ).

Research method

The analysis model was developed in the context of an action research project in Indonesian schools (Kartika-Ningsih, 2016 ). The project was interventionist in nature in that it sought to develop an ideal model of bilingual teaching practices. It used the genre-based literacy methodology known as Reading to Learn (R2L) (Rose, 2018b ; Rose & Martin, 2012 , 2014 ), which was adapted and extended to suit Indonesian multilingual classrooms. The R2L methodology is a system of teaching strategies that guide learners to read and learn from reading, and then use what they have learnt from reading in their writing. However, the aim of this paper is not to describe this pedagogic model, but rather the language shift analysis that was developed from the research.

The research project involved classes from two secondary schools, representing common types of multilingual classrooms in Indonesia. One school was more economically advantaged than the other, but both schools shared similar linguistic backgrounds. Most teachers and students in both schools spoke Bahasa Indonesia as well as Sundanese as the regional language. English as a foreign language was a major subject in the school curriculum, and was thus a familiar language for students and teachers in the area.

The students included boys and girls in Year 8 (13–15 years old). At the time of intervention, English and biology were learned within an integrated literacy program. The curriculum goal for English was to write descriptive reports; the goal for biology was to study endangered species. The intervention program was designed for students to write descriptive reports in English about endangered Indonesian birds.

Briefly, the intervention involved jointly reading descriptive reports in detail, making notes on the board from these texts, and writing new texts on the board from the notes. In the R2L methodology, these activities are known as Detailed Reading, Note-making, and Joint Construction (Rose & Martin, 2012 ). This sequence was repeated three times with each class. In the first two iterations, an L1 (Indonesian) text was read, notes were made in L1 and translated into L2 (English), and an L2 text was written from the notes. In the third iteration, an L2 text was read, and notes and a new text were written in L2. Students then independently researched, made notes and wrote their own texts in L2. Results included significant improvements in all students’ L2 writing (Kartika-Ningsih, 2016 ).

Data were collected in the form of video and audio recordings of classes during the intervention. The analysis focuses on the teaching learning activities and the interactions between teachers and students.

Mapping the focus of multilingual teaching practices

Debate on l1 use in l2 learning.

It has been argued for many years that L2 teaching should take place only in the target language, as using L1 in the classroom is an obstacle for L2 learning (Howatt, 1984 ; Lambert, 1984 ; Yu, 2000 in Cummins, 2014 ). One reason often given is that L1 is a source of interference and hence errors in students’ L2 speech and writing production. Another is that an L2 only classroom may be the only environment where students living in a non-L2 community can be immersed in the target language.

Conversely, the L2 only position has been criticised as oriented to monolingualism and native-speakerism, rather than the reality of multilingual environments (Lin, 2013 ). Studies of code-switching argue for the benefits of L1 use in L2 learning (Canagarajah, 2011 ; Levine, 2011 ; Lin, 2015 ). The term translanguaging has been proposed to distinguish effective code-switching from random practices (Garcia and Wei, 2014 ). There have been a number of studies describing code-switching practices (Creese & Blackledge, 2010 ; Lin, 2015 ). However, these studies have generally not provided pedagogical frameworks or models which can be applied by teachers in multilingual environments. Identifying effective language shift practices remains a challenge.

A particular concern for identifying effective practices is the focus on either language or content discrimination in various L2 teaching programs. Language-focused programs often emphasize knowledge about language, privileging particular ‘language skills’ as building blocks towards L2 competence. Types of language focus commonly found in teaching methods offered for EFL education include grammatical knowledge, L1 to L2 translation, or communication purposes. On the other hand, content-focused approaches may attempt to integrate language with subject discipline knowledge. For example, CLIL programs involve the teaching of subjects such as biology or mathematics in L2 (e.g. Coyle et al., 2010 ; Cenoz et al., 2014 ). However there is ‘no single pedagogy’ for CLIL programs (Coyle et al., 2010 , p.86). While they share a common focus on subject content, there is no standardization of implementation, including the use of L1 and L2 in the classroom.

A framework for mapping multilingual teaching focus

A systematic analysis of the use of L1 and L2 in multilingual classrooms must consider both the extent of L1 and L2 use, and the teaching focus on language or content. For this purpose, we will introduce the terms ‘enveloping’ for teaching practices favouring L2 use, as learners are ‘enveloped’ in the target language, and ‘enfolding’ for practices favouring L1 use, as the target language is ‘enfolded’ in the use of L1 (Kartika-Ningsih, 2016 ). These neutral terms are preferred to value-laden metaphors like ‘immersion’, which invoke quasi-religious inferences such as revelation by baptism, in place of empirical analysis of pedagogic practice.

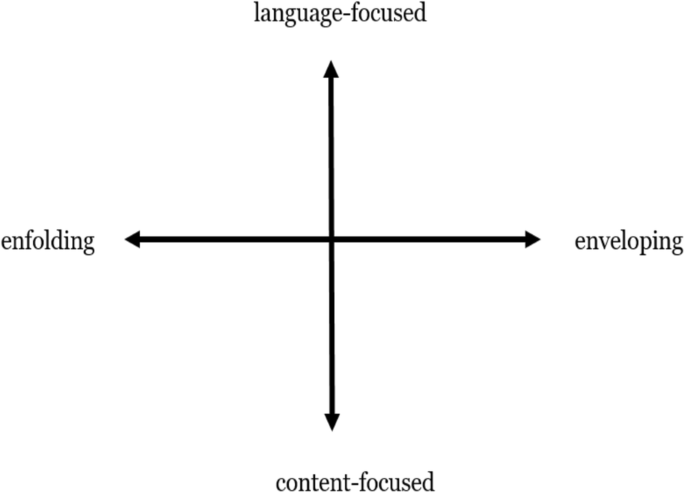

In Fig. 1 , variations in language use and teaching focus in L2 teaching are mapped as a topology, with two axes. One axis is language use in L2 classrooms. At one pole of this axis, L2 only practice is termed ‘enveloping’. At the other pole, mixed L1 and L2 use are termed ‘enfolding’. The other axis is the teaching focus, on either content or language. At one pole, language is the primary focus of the L2 teaching method. At the other pole, content is the primary focus in subject discipline teaching in L2. This creates four quadrants which allow placement of various teaching approaches, depending on their language use and teaching focus.

Topology of bilingual education programs. The topology of bilingual education programs consists of two intersecting axes. The vertical axis reveals language learning on two poles: language-focused at the top end and content-focused at the bottom end. The horizontal axis represents language use which involves enfolding as a cline with L1 as transitional and enveloping at the other one as L2 only use

The aim of this topology is not to prioritize one teaching method over another, nor to suggest keeping L2 learners in enfolding or enveloping practices. The critical point is to consider how L2 teaching and learning involves L1 and L2 use, and how language and content are taken into account. To this end, it is essential to carefully describe the structures and functions of language shift in pedagogic practices.

The sequence of pedagogic activities in the intervention can be positioned in this framework, as follows. Firstly, the primary curriculum goal was language-focused, for students to write a descriptive report in L2 (English). However, this language focus was embedded in a content-focused curriculum goal, to learn about a scientific field, biological classification and description. These goals were integrated by studying L1 and L2 texts about bird species, and using note-making and joint construction to write L2 texts on this topic. Secondly, the language of instruction varied with the activities. In the early stages of the teaching sequence, enfolding practices predominated, to support students to gain control of the curriculum field enfolded in L1 use. As students’ control of the field and language skills developed, reading and writing in L2 became enveloped in L2 use.

Re-examining multilingual classrooms

Two dimensions of multilingual classrooms need to be considered in analyses. One is multilingualism, where two or more languages may be deployed in interactions. The other is the structuring of teacher/student relations in the institutional setting of the classroom. To this end, the SFL model of text-in-context is drawn on to describe the structuring of teacher/learner interactions, and the functions of language shift in these interactions.

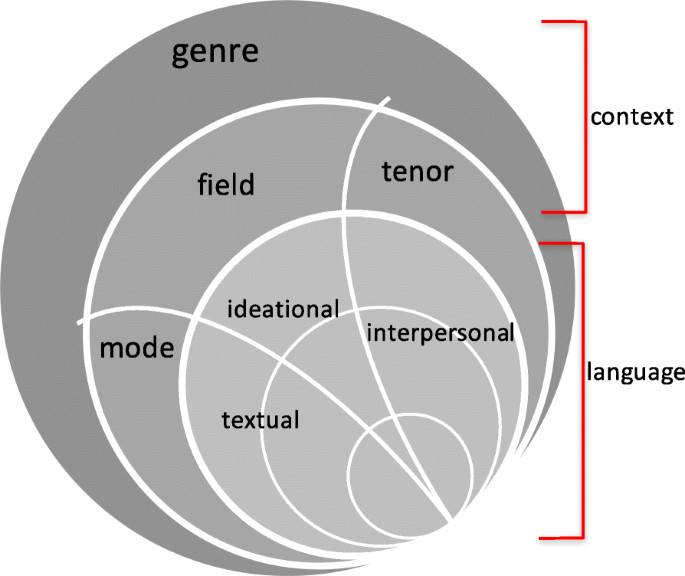

Text-in-context model: Theoretical framework

The systemic functional (SFL) model of language as text-in-context identifies three broad dimensions of social contexts, including the tenor of social relations between interactants, the field of their activities, and the mode of meaning making, as spoken or written language or other modalities (Halliday, 1978 ). These are variables in the contextual stratum of register. They are configured together at the level of genre, that is, a genre is a configuration of variations in field, tenor and mode (Martin, 1992 ; Martin & Rose, 2007 , 2008 ). Field, tenor and mode are realised by distinct metafunctions in language, including ideational, interpersonal and textual metafunctions. Language is also stratified in three strata, as discourse semantics, lexicogrammar and phonology/graphology. This model of language in context is set out in Fig. 2 .

The SFL model of language in social context. Language model in genre pedagogy adopts language in social contexts, represented as a layered circle. Context consists of genre, mode, field, and tenor. Genre or text type is positioned on top of the co-tangential circles. Mode, field and tenor are within the top of the co-tangential circles. Language consists of textual, ideational and interpersonal metafunctions. Textual metafunction corresponds to mode, ideational to field and tenor to interpersonal

This model is useful to investigate multilingual interactions in classroom settings, because it allows us to choose certain dimensions to focus on that are relevant for the study. Starting at the top, the genre of classroom lessons is known as a curriculum genre (Christie, 2002 ; Rose & Martin, 2012 ). Curriculum genres configure two registers together. One is a pedagogic register that includes pedagogic activities (field), teacher/learner relations (tenor) and the spoken, written, visual and other modalities they use (mode). Through these pedagogic activities, relations and modalities, teachers and learners exchange knowledge and values which are known as a curriculum register (Rose, 2014 , 2018a ).

Curriculum genres can be contrasted with knowledge genres, which include the written genres of the school, such as stories, chronicles, explanations, reports, procedures, arguments and text responses (Martin & Rose, 2008 ). Knowledge genres configure the fields of curriculum subjects, such as history, science, mathematics, literature. Students learn to read and write these knowledge genres, at the same time as learning the curriculum content, by participating in the curriculum genres of the classroom. While curriculum content is taught explicitly, its knowledge genres are usually left implicit, but can be made explicit (Rose & Martin, 2012 ). For example, in the lessons reported here students learnt to read and write scientific reports at the same time as learning about bird species. Understanding that language realises both genre and register enables explicit language teaching to be embedded in subject teaching.

Structures of pedagogic exchanges

Pedagogic activities and relations are enacted in language by exchanges between teachers and learners. The structures of exchanges, and speakers’ roles in them, are options in the discourse semantic system of negotiation . Speakers take up roles such as giving or demanding goods, services or information, and these roles may initiate an exchange or respond to preceding roles.

An exchange may negotiate either knowledge or action, and speakers may take a primary or secondary role in either. In an action exchange, the role that performs the action is the primary actor (A1), and the role that demands the action is a secondary actor (A2). In a knowledge exchange, the role that that provides the knowledge is the primary knower (K1), and the role that demands the knowledge is a secondary knower (K2).

If an exchange is initiated by a primary A1 or K1 role, it may constitute the whole exchange, simply by performing the action or providing knowledge. For example, teachers commonly present knowledge in single K1 roles that constitute the whole exchange.

An exchange may be initiated by a secondary A2 or K2 role, which demands action or knowledge and is followed by an A1 or K1 role, performing the action or providing the knowledge. Table 1 shows an example. In addition, the secondary knower follows up with thanks, labelled K2 f.

If an exchange is initiated by a primary actor or knower, it may also anticipate an A2 or K2 response. In this case the initiating role is a delayed primary role (dA1 or dK1). For example, dA1 May I leave? - A2 Yes you may - A1 [leaves]. In a very common pattern in curriculum genres, the teacher initiates with a question, a learner responds, and the teacher evaluates the response. Although the learner displays knowledge, the teacher is the primary knower with the authority to evaluate the learner’s knowledge. An example is Table 2 , in which a class is reviewing knowledge about the text type procedure .

This excerpt includes two numbered exchanges, each initiated by the teacher as dK1. In exchange 1, the teacher initiates by leaving the end of her sentence empty (...), which invites learners to supply the missing element. Several students respond by supplying the missing word ‘procedure’, and the teacher affirms by approving and repeating their response. In exchange 2, the teacher extends with a further question, one student responds and the teacher affirms by repeating the response.

Language shift in classroom interactions

Types of language use.

In multilingual classrooms, language shift takes part during learner/teachers interactions. There are four general patterns of language use in such classrooms, including:

L1, L2, and L3.

These four language use options are illustrated here in examples from Indonesian classes, in which students are learning English as a foreign language (EFL), in other words as L2. Table 1 was an example of an L2 only interaction, as it is conducted entirely in English in an Indonesian classroom.

Table 3 exemplifies L1 only dialogue in Indonesian. Each move is translated below in italics. The teacher and students are discussing the word ‘beaker’ and the reason it is named beaker. The Indonesian word for beaker is borrowed from English, along with the English spelling. The teacher initiates by leaving the end of her sentence empty, and two students attempt to supply the missing word. However, this is not the answer the teacher wants, and she provides the word herself (claiming it is called ‘beaker’ because its spout resembles a bird’s beak or paruh in Indonesian.)

Table 4 exemplifies both L1 and L2 used in the same dialogue. This time the teacher and the students are talking about conjunctions that are used in procedure texts. English wordings are included in the Indonesian discussion. The teacher initiates in Indonesian, in which the word class ‘temporal conjunction’ and example ‘first’ are in English. A student responds with another English example ‘then’, and the teacher affirms in Indonesian. English words are underlined.

Table 5 exemplifies language interplay where three languages are involved, Indonesian, English and Sundanese. The teacher initiates by asking the English name for Indonesian pinset ‘tweezers’. One student guesses the English word ‘princess’ from the sounds, another proposes the Sundanese word cocolok ‘skewer’, and the Sundanese word panyapit ‘tongs’. The teacher ignores all these incorrect answers and writes the English word ‘tweezers’ on the board. (The Indonesian word pinset is actually borrowed from Dutch for ‘tweezers’.)

These four examples of different patterns of language use portray typical interactions in multilingual classrooms. In Indonesian classrooms, L1 is used pervasively as it is part of the students’ everyday life, despite teachers’ efforts to use more L2. Teachers often use L2 for the goals of language knowledge, but use L1 to manage classrooms.

Structures of language shift in exchanges

Tables 4 and 5 illustrated language shift, occuring between roles in an exchange, from dK1 to K2 and K1 roles. Language shift can also occur within roles, between and within moves.

Each role in an exchange includes one or more moves, that are realized in grammar by a major or minor clause (Martin, 1992 ; Martin & Rose, 2007 ). Hence the structures of exchanges consist of three ranks: the whole exchange, the roles of speakers, and the moves they make in the exchange. A role consists of one or more moves, an exchange consists of one or more roles, and there may be a series of exchanges in an interaction.

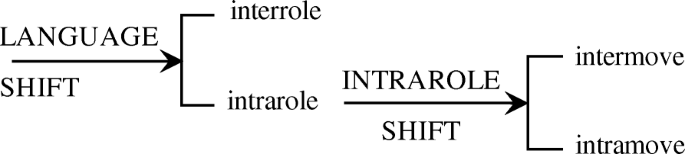

In the structures of exchanges, three types of language shift are possible: between roles, or ‘interrole’; between moves within roles, or ‘intermove’; and within moves, or ‘intramove’. These three types are described as follows.

In interrole language shift, a teacher may use one language in the initiating roles of an exchange and another language in the closing roles, while students may use either language. Table 6 illustrates interrole language shift between teacher and students. In the first two roles, labeled as K1 and dK1, the teacher uses L1 (Bahasa Indonesia) to ask for the Latin name of a bird. A student responds with the Latin name, and the teacher affirms in L2 (English).

Intermove language shift occurs when a teacher uses both L1 and L2 in the initiating and/or closing roles of an exchange. In Table 7 , two examples of intermove shift are shown. In the first role (A1) the teacher directs students’ attention to the text in L2. In the following K1 roles, she refers to the sentence in L1 in one move, then reads in L2 in the next move. (Note that, while reading, she also glosses the L2 words ‘soft’ and ‘tail’ as L1 words). In the following dK1 role, the teacher uses L2. A student then responds in L1 in one move, but then identifies the wording in L2. The teacher then affirms in L2 in two moves.

Intramove language shift is perhaps the most common type of language shift found in both daily life and multilingual classroom settings. In Table 8 , the teacher and students are jointly constructing a new sentence from notes written in L2. In the first K1 move, the teacher uses L1 to refer to the sentence on the board, but then reads it in L2. In the next K1 move, she uses L1 to refer to the next sentence to be written, but names its topic in L2. In the following dK1 move she asks a question in L1, but with an L2 topic, and clarifies in L2 but reads from the notes in L2. A student then responds in L2 and the teacher affirms in L2.

Figure 3 displays the options for language shift in exchanges as a system network. The first choice is between interrole and intrarole (between or within exchange roles). Intrarole then has a further option of intermove and intramove (between or within exchange moves).

Options for language shift in exchanges. Language shift system consists of two options: interrrole and intrarole. Intrarole has a further option: intermove and intramove

The language shift system provides an explicit framework for analysing code-switching in multilingual classroom interactions. It addresses common patterns of language interplay such as translating, or bringing equivalence from L1 to L2 or vice versa, as well as ‘code-switching’ or using two or more languages in the interactions. This analysis offers the possibility of measuring effectiveness of multilingual teaching and learning.

Pedagogic functions of language shift

As language functions in social contexts, identifying the pedagogic functions of language shift involves a step up from the discourse structures of exchanges to the contextual stratum of register. In terms of pedagogic register, language shift may function to scaffold the teaching/learning activity, to enact teacher/learner relations, or to present the sources of meanings. In order to show the functions of language shifts, this section introduces analyses of these three dimensions of pedagogic register. Values in pedagogic register that are applied in the analyses here are set out as tables in the Appendix to this chapter.

Structures of pedagogic activity

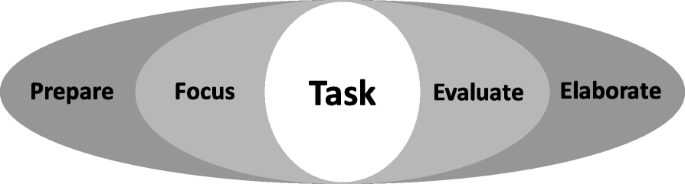

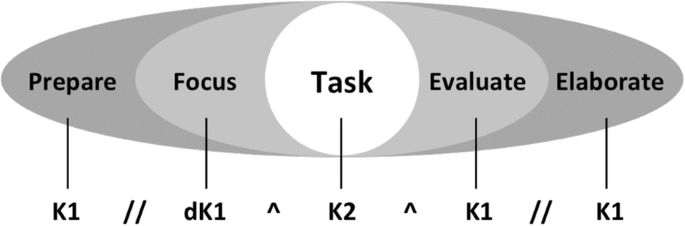

Pedagogic activities are structured in hierarchies of lesson stages composed of one or more lesson activities , that are composed of one or more learning cycles at the level of teacher/learner exchanges. Activities at each of these three ranks are centred on a learning task, through which knowledge is construed by learners; macro-tasks at the level of lesson stages, and micro-tasks at the level of learning cycles. Learning tasks are typically focused (specified) and then evaluated by a teacher. In addition, teachers may first prepare learners to succeed with the task, and the knowledge they construe through the task may then be elaborated. These five structural elements are termed Prepare, Focus, Task, Evaluate and Elaborate phases (Martin & Rose, 2007 ; Rose & Martin 2012 ). The orbital structuring of pedagogic activities as nuclear and marginal phases is diagrammed in Fig. 4 .

Nuclear and marginal phases of learning cycles. Learning cycles are orbital with nuclear and marginal phases. The nuclear phase consists of Focus – Task – Evaluate, Task being the core phase of the cycles. The marginal cycles are Prepare and Elaborate

At the rank of learning cycles, each of these phases may be enacted by a single exchange role. At this level, a common task of learners is to respond to teachers. This task is typically focused with a question or command, and then evaluated by affirming or rejecting. The Focus is typically a dK1 role, the Task is K2 and Evaluate is K1. Prepare and elaborate phases are additional exchanges that may be single K1 roles. The mapping of these elements on exchange structures is exemplified in Fig. 5 . This is an exchange series, as the Prepare and Elaborate phases are additional exchanges consisting of a single K1 role. Double slashes indicate boundaries between exchanges in series.

Phases of pedagogic activities enacted by exchange roles. The orbital structures of learning exchange correspond to exchange roles in pedagogic activities. At the nuclear cycles, Focus is realized as dK1, Task as K2 and Evaluate as K1. In marginal cycles, Prepare is realized as K1 and Elaborate as K1

Table 9 illustrates the phases of a learning cycle, along with the matter that each phase is concerned with. The class is reading an L1 (Indonesian) factual text in detail, identifying and discussing wordings in each sentence. In this learning cycle, the students’ task is to identify a wording in the sentence, the Latin name for a bird species, Nisaetus bartelsi . The teacher prepares this task in two K1 moves, using L1. First, she gives the wording she is after, within the statement it’s about names of Nisaetus bartelsi. Then she gives a further clue, one name which is mentioned as the Latin name . The dK1 Focus then asks students to identify this, What’s the Latin name, again in L1. Students identify the wording in the sentence, and the teacher affirms in L2, OK, good , and repeats the answer. A dotted line marks exchanges within this learning cycle.

In this cycle, the functions of L1 use are apparently to prepare and focus the task of identifying wordings in an L1 text. Language shift occurs in the evaluating phase. As evaluation is a feature of pedagogic relations, this analysis is added in Table 10 .

Pedagogic relations: Acts and interacts

Pedagogic relations include the roles of teachers and learners, termed interacts , and the pedagogic acts that they negotiate. For teachers, these roles include presenting knowledge, evaluating learners and directing the activity. Learners may display knowledge and both learners and teachers may solicit acts from each other. Acts include pedagogic behaviours and acts of consciousness, illustrated in Table 11 . Realisations of acts and interacts are underlined in transcripts, where possible.

Table 10 re-analyses the same interaction as Table 9 , in terms of acts and interacts. By starting the first Prepare move with the L1 words So now it’s about, the teacher invites students’ anticipation of what will follow in the text [invite anticipation]. The second L1 move then invites their perception of the text There’s this one name [invite perception] . The L1 Focus question then directs students to display what they perceive [direct display], and students display their perception by saying the wording, Nisaetus bartelsi [display perception]. Footnote 2 The function of the language shift to L2 is to affirm the students’ display [approve display]. While L1 was used in the Prepare and Focus phases to facilitate the acts of anticipating, perceiving and identifying wordings in the L1 text, L2 is used here to amplify the value of affirmation for the students, in the context of a lesson whose goal is L2 learning.

Pedagogic modalities: Sources and sourcing

Inviting anticipation and perception are interpersonal aspects of guiding learning. As the task is to identify wordings in a text, another aspect is to guide learners towards the wordings, by locating them in the text and describing them. These are features of pedagogic modalities. Pedagogic modalities are the sources of meanings in the learning discourse, and the means of sourcing them into the discourse. Sources of meanings include the environment, spoken knowledge of teachers and learners, and records such as written texts, graphic images and video recordings. Each of these source types has a set of options for sourcing them into the discourse. Options for sourcing from recorded texts are illustrated in Table 12 .

In Table 13 the source of meanings is the text that the class is reading in detail. The first Prepare move locates the meanings in the text with the pronoun now it’s about, which refers to the text. The second Prepare move describes the meanings, as the Latin name . The Focus question repeats this What’s the Latin name , and students identify the wording by reading the text.

Sourcing and interacts work together to prepare and focus the task for students. The first Prepare move invites anticipation at the same time as locating the target meaning in the text. The second move both invites perception and describes the meaning. The Focus facilitates the students’ display by repeating the preceding move. These cycle phases are presented in L1 to reduce the students’ semiotic labour, when reading an L1 text.

Functions of language shift in a multilingual literacy lesson

The detailed reading interaction in Table 9 is an excerpt from the early stages of a lesson sequence, which is ultimately aimed at learning to read and write L2 texts. In a later stage of this lesson sequence, the class is guided to write an L2 text from notes on the board that are also written in L2. At this stage, L1 is used more sparingly. Tables 14 and 15 are a longer excerpt from this later lesson stage, comprising a lesson activity. This excerpt illustrates functions of each type of language shift: interrole, intermove and intramove.

The function of this lesson activity is to write a sentence in L2 (English), that describes the female of a bird species, using notes written on the class board in L2. The teacher’s goals are to expose students to multiple options for structuring the L2 sentence, to make it coherent in the contexts of the text and the topic. This is achieved by reading the notes, asking students for ideas, and rephrasing them in various wordings. The students’ tasks are to perceive the notes and text on the board, to propose ideas for the new sentence, and to follow the teacher’s proposals for structuring it.

This activity consists of a task and elaborate phase, comprising three learning cycles each. In the task phase (Table 14 ), the teacher invites students to reason about an L2 sentence using the notes. In the elaborate phase (Table 15 ), she models how to reason about the sentence structure, and finally directs one student to scribe the sentence on the board. In the transcript, L1 is marked in bold to make language shifts clear, and types of language shift are labelled in the matter column.

In cycle 1 of the task phase (Table 14 ), the teacher first directs students’ attention in L1, Listen to this . She then prepares the task in two moves involving intramove language shift. She first uses L1 to invite perception of the preceding sentence The sentence has started with , and reads it in L2. She then uses a mix of L1 and L2 to direct the writing activity The next sentence will explain the female. She focuses the task in L1 and L2 by asking students to perceive the note describing the female bird. Student 1 then proposes a whole L2 sentence, which displays her reasoning about an appropriate L2 sentence structure. The teacher praises her in L2 and repeats the sentence to the class, still using an L1 word, S1 bilang ‘S1 said’.

In cycle 2, the teacher solicits ideas from other students. She uses intermove language shift to focus the task, first in L2, Any other sentences? and repeats the question in L1. Student 2 proposes an L2 sentence, and the teacher praises in L2. Cycle 3 is then entirely in L2. The teacher again asks for other possible sentence structures, Student 3 proposes an incoherent L2 wording, which the teacher rephrases in L2. In terms of evaluation, this rejects S3’s proposal, but it also prepares the task, so that S3 repeats it as an L2 sentence beginning. S3 pauses and other students propose a further wording to complete the sentence, which the teacher praises in L2.

Elaboration phase

In cycle 4 (Table 15 ), the teacher elaborates on the students’ sentence structure proposals in three steps, using intermove and intramove language shift. First, she models a choice between two L2 sentence structures. She invites the choice, using L1 only. She then states the L2 options, but frames the choice in L1 words, ada ‘there’s’ and atau ‘or’ (intramove shift). In the second step, she uses L1 to invite perception of the preceding sentence, then reads it in L2, but frames it in L1, tadi dibilangnya ‘it was mentioned’ (intramove). In the third step, she models reasoning about the appropriate L2 structure to follow this sentence, and uses L1 to frame each step in the reasoning (intramove). Finally she states the L2 sentence.

In cycles 5–6 a student scribes the sentence with the teacher’s guidance. In 5, this task is labelled as propose spelling, as the student makes a spelling error which the teacher rejects by saying the correct L2 pronunciation and pointing at the word in the notes, which prepares the student to correct the spelling. In 6, the teacher focuses on punctuation with an L1 question, reminding the student to write a period, which the teacher affirms by naming it and praising her.

In sum, there are two phases in this activity. In both phases, there is an overall trend from more L1 when preparing and focusing to more L2 as tasks are evaluated and elaborated. Technically speaking, preparing and focusing tend to be enfolded in L1, while evaluating and elaborating tend towards enveloping in L2.

Within each learning cycle, the teacher tends to use L1 in the first moves for directing attention, directing the activity, and asking students to reason, perceive or remember. As the activity is concerned with L2 text, the following moves tend to mix L1 and L2. L1 is used for framing the tasks, for example, for modelling reasoning about L2 sentence structures. On the other hand, the students’ tasks are to propose L2 wordings, and the teacher consistently affirms them in L2. Thus the overall trend in each phase is from L1 only in teacher’s initial moves, to intramove language shift within following moves, to L2 only in students’ tasks and teacher’s affirmation.

This paper has offered a brief illustration of language shift analysis in multilingual pedagogic practice. Language shift was defined as the process of meaning making realized in two or more languages, incorporating popular concepts such as ‘code-switching’ and ‘translanguaging’.

The analysis included three components. The first was a topology of multilingual teaching approaches, to map the curriculum focus on language or content, and the pedagogic use of L1 or L2, using the terms ‘enfolding’ in L1 and ‘enveloping’ in L2. The second was an exchange structure analysis of pedagogic interactions, to show the structures of language shift beween speaker roles (interrole), between moves within each role (intermove), and within moves (intramove). The third was an analysis of the pedagogic functions of language shift, at the contextual level of register. It was found that language shift varied with phases in learning cycles, and with sequences of learning cycles and lesson stages. L2 learning tended to be enfolded in L1 use at the start of sequences, and increasingly enveloped in L2 use towards the end of sequences. Within learning cycles, teachers tended to use language shift of each type in preparing L2 learning tasks, and in elaborating meanings, while students tended to respond in L2, and teachers evaluated responses in L2.

We should emphasise that this is a preliminary study, designed to develop the language shift analysis tools and test their application. In this case, the tools were developed and applied to analysing patterns of language shift in a designed intervention in an action research project. This intervention was deliberately designed as a scaffolded language development sequence, from reading and writing in L1 to reading and writing in L2. Furthermore, within the first two iterations of this teaching sequence, reading texts and writing notes in L1 provided a foundation for writing notes and texts in L2. Hence, L2 development was deliberately enfolded in L1 use in early stages, and enveloped in L2 use in later stages. The language shift analysis tools developed in this context need to be tested, refined and extended in a variety of other multilingual classroom settings.

In our view, the aim of further developing and applying the language shift analysis is to identify and design language teaching practices that are effective for all learners. A benefit of this approach is that decisions about language use in multilingual classrooms can be based on empirical evidence of efficacy, rather than ideological commitments to one practice or another. The action research project here used language shift carefully to scaffold students’ L2 language development, with significant results. These improvements were achieved, not by favouring L1 or L2 use, or focusing on either language or content. Rather it embedded language development in curriculum content, and enfolded in L1 or enveloped in L2 where appropriate. The trend at each rank of lesson stage, lesson activity and learning cycle is from enfolding in L1, to intramove language shift, to enveloping in L2 as students’ skills and confidence grows. As multilingualism grows across the globe, we hope that the tools developed here will help researchers design increasingly effective and inclusive language pedagogy practices.

The term language shift here is to refer to the system of code-switching, not to be confused with the same term used in sociolinguistics.

The term [display] is used, as learners display for teacher evaluation.

Abbreviations

Primary actor

Primary actor follow-up

Secondary actor

Secondary actor follow-up

Delayed primary actor

Delayed primary knower

Primary knower

Primary knower follow up

Secondary knower follow up

Secondary knower

Bernstein, B. 1990. Class. Codes and control IV: The structuring of pedagogic discourse . London: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: theory, research, critique . London & Bristol, PA: Taylor & Francis (revised edition Lanham, Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield.).

Google Scholar

Canagarajah, A. 2011. Translanguaging in the classroom: Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. Applied Linguistics Review 2: 1–28.

Cenoz, J., F. Genesee, and D. Gorter. 2014. Critical analysis of CLIL: Taking stock and looking forward. Applied Linguistics 35 (3): 243–262.

Article Google Scholar

Christie, F. 2002. Classroom discourse analysis . London, New York: Continuum.

Coyle, D., P. Hood, and D. Marsh. 2010. CLIL: Content and language integrated learning . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Creese, A., and A. Blackledge. 2010. Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: A pedagogy for learning and teaching? The Modern Language Journal 94 (1): 103–115.

Cummins, J. 2014. Rethinking pedagogical assumptions in Canadian French immersion programs. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 2 (1): 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.2.1.01cum .

Garcia, O., and Li Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education . London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Halliday, M.A.K. 1978. Language as a social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning . London: Arnold.

Howatt, A. 1984. A history of English language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kartika-Ningsih, H. 2016. Multilingual re-instantiation: Genre pedagogy in Indonesian classrooms . PhD thesis: Sydney University http://www.isfla.org/Systemics/Print/Theses/HKartika-Ningsih_thesis.pdf .

Lambert, W.E. 1984. An overview of issues in immersion education. In California State Department of Education (Ed.), Studies on immersion education: A collection for United States educators (pp. 8–30). Sacramento: California State Department of Education.

Levine, G.S. 2011. Code choice in the language classrooms . Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Lin, A. 2013. Classroom code-switching: Three decades of research. Applied Linguistics Review 4 (1): 195–218 http://hdl.handle.net/10722/184270 .

Lin, A. 2015. Conceptualising the potential role of L1 in CLIL. Language, Culture and Curriculum 28 (1): 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2014.1000926 .

Martin, J. 1992. English text: System and structure . Philadephia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Martin, J.R., and D. Rose. 2007. Working with discourse: Meaning beyond the clause . London: Continuum.

Martin, J.R., and D. Rose. 2008. Genre relations: Mapping culture . London: Equinox.

Maton, K. 2013. Knowledge and knowers: Towards a realist sociology of education . London: Routledge.

Montolalu, L.R., and L. Suryadinata. 2007. National language and nation-building: The case of Bahasa Indonesia. In Language nation and development , ed. L.H. Guan and L. Suryadinata, 39–50. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Rose, D. 2014. Analysing pedagogic discourse: an approach from genre and register. Functional Linguistics, 1:11, http://www.functionallinguistics.com/content/1/1/11, https://functionallinguistics.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40554-014-0011-4

Rose, D. 2018a. Pedagogic register analysis: Mapping choices in teaching and learning. Functional Linguistics 5: 3 Springer Open Access, http://rdcu.be/HD9G .

Rose, D. 2018b. Reading to Learn: Accelerating learning and closing the gap , Teacher training books and DVDs. Sydney: Reading to Learn http://www.readingtolearn.com.au .

Rose, D., and J. Martin. 2014. Intervening in contexts of schooling. In Discourse in Context: Contemporary Applied Linguistics , ed. J. Flowerdew and Li Wei, vol. 3, 273–300. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Rose, D., and J.R. Martin. 2012. Learning to write, reading to learn: Genre, knowledge and pedagogy in the Sydney school . South Yorkshire/Bristol: Equinox Publishing.

Sneddon, J.N. 2003. The Indonesian language: Its history and role in modern society . Sydney NSW: University of New South Wales Ltd.

Yu, W. 2000. Direct method. In M. Byram (Ed.), Routledge encyclopedia of language teaching and learning (pp. 176-178). New York: Routledge.

Download references

Availability of data and materials

Please contact authors for data requests.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Faculty of Education, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Ma Liu Shui, Hong Kong

Harni Kartika-Ningsih

Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR

Department of Linguistics, University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HK carried out the project, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. DR analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Harni Kartika-Ningsih .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Pedagogic Register Analysis

Tables 16-20 set out the values in pedagogic activities, modalities and relations that are applied in analyses above. See Rose ( 2018a ) for further discussion.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kartika-Ningsih, H., Rose, D. Language shift: analysing language use in multilingual classroom interactions. Functional Linguist. 5 , 9 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40554-018-0061-0

Download citation

Received : 24 April 2018

Accepted : 02 August 2018

Published : 22 August 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40554-018-0061-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Code-switching

- Language shift

- Multilingual classrooms

- Classroom discourse

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Language Maintenance and Shift

2018, Handbook of pragmatics

Related Papers

Thorold (Thor) May

This short informal paper stems from reflection on an address by Ken Hale, doyen of minority languages (and now sadly deceased). It looks at the role of linguists themselves in the dynamic of language maintenance and the twin phenomena of language loss and language birth. The uniqueness of each language is weighed against the costs and benefits of language homogenization. It is recognized that the majority of speakers are ultimately pragmatists about language choice, yet an argument remains for offering some minority language support to groups struggling with their ethnic identity. Finally, it is asked whether language maintenance or revival can actually pose other risks under certain conditions.

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation

Nasiba Alyami

Based on the fact that our social and national identities are usually communicated and interpreted through language (Abdelhadi (2017), Sacic (2018)), and the scholarly belief that a shift in one’s language, from his/her mother tongue to a more dominant language, can contribute to an unintentional cultural merge or loss of original identity (Fishman (1991), Nowak (2020)), the current paper aims to shed light on the research concerned with the language shift (LS) phenomenon, with more focus on the historical development of the concept, the factors affecting it, the domains and stages of LS, and types of LS research. The paper also reviews some relevant concepts to LS, such as the relationship between language and identity, and the theory of ethno-linguistic vitality (EV) and language attitudes. In addition, a review of recent studies on LS in general, i.e. internationally, and in the Arab world more specifically is also provided.

Salvatore Callesano

Sekarlangit Tjitrosoediro

The existence of language surely cannot be separated from our daily life. Through language, the interaction among tribes and religions can be delivered smoothly. As a system of communication, language also helps humans to complete all of their activities without facing the scarcity in understanding of one’s another language. That is under the condition they share the same knowledge of a certain language and utter it as the medium of communication. They also share the same understanding in all of their vernacular aspects, like the grammatical, structure, and the choice of words (either it is formal or not). And they should have agreed about some puns and slangs that are allowed to use in the middle of conversation. But how about people from different ethnic groups or tribes understanding what people from out of their groups say? Are they going to face difficulties as the result of not having clear mind about the dominant language they find in society?

Kamal Sridhar

Mark Sicoli

While the macro variables of language shift are well understood, e.g., economic pressures and standard language ideology, we question if reference to generalized factors is explanatory? We argue that explanatory adequacy in a science of language shift can only be achieved through ethnographic engagement with the particular histories and interpretive practices of linguistic communities to understand what changing patterns of language use mean for the people in question. We show through comparing and contrasting ethnographic accounts that language shift occurs at the interface between languages and culturally-elaborated meanings, beliefs, and habits that guide people’s linguistic interpretations, actions, and choices.

International Journal of the Sociology of Language

Vivian Klerk

University of Wisconsin - Madison dissertation

Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism

Oksana Laleko , Olesya Kisselev

The urgent need to understand the processes of language shift in endangered language communities has spurred a renewed focus on the long-standing problem of accounting for linguistic variation, easily observable in monolingual settings but amplified to much greater proportions in contexts where multiple languages coexist in a shared space, either within a broader society or in the minds of individual speakers. At the heart of this issue lies the difficulty of selecting a point of comparison against which the extent of linguistic variation could be established. These concerns have echoed through multiple areas of language study over the last few decades, from 'the comparative fallacy' in second-language research (Bley-Vroman, 1983), the 'comparability problem' in linguistic typology (Evans, 2020), 'the lack of linguistic benchmarks' issue in traditional dialectology (Tillery & Bailey, 2003), to 'the baseline challenge' in heritage linguistics (D' Alessandro et al., 2021). It is these vital problems of variability and comparability that Grenoble and Osipov (2023) bring forth in their timely and much-needed account of language shift ecologies in indigenous language contexts. While establishing a baseline is important in our efforts to identify the linguistic effects of language contact and diachronic change, in endangered shift ecologies an idealized baseline may be unattainable, as Grenoble and Osipov (2023) readily acknowledge. Much of this problem stems from the general vulnerability of such ecologies on the sociodemographic axis: a vanishingly small number-if any at all-of monolingual minority language speakers, rapidly decreasing communities of practice, and drastically reduced opportunities for naturalistic language use all make the researchers' empirical quest for the 'golden standard' of the shifting language elusive. Published resources are not always helpful either: an important aspect of establishing the baseline lies in the intrinsic variation in the language itself and situating the benchmark in the so-called 'standard variety' of the minority language-often based on

Language Crisis in the Ryukyus

Mark Anderson

This book chapter is a diachronic study of the process of language shift in Okinawa. I demonstrate how a language shift profile in the form of a timeline can be constructed retrospectively using qualitative synchronic data. These data comprise field recordings of natural conversation between Okinawans of different age cohorts in combination with parameters such as child-bearing age, life expectancy and the age at which people enter the workforce. As shown throughout the discussion, the results can then be triangulated with other researchers’ accounts of the historical context of each phase of shift. The timeline drawn in this chapter illustrates how new subgroups of people with different linguistic behaviours have emerged in the Naha/Shuri community as language shift has progressed. It therefore enables us not only to see how language use has changed over the years, but also to make predictions as to the future course of shift, i.e. when the Okinawan language (Uchinaaguchi) is likely to reach various stages of decay, and finally, extinction. This method of visually representing language shift will be useful not only for scholars interested in the Ryukyuan situation but also for those involved in the study of other endangered languages. APA citation: Anderson, Mark (2014). Language shift and language loss. In Mark Anderson and Patrick Heinrich (Eds.), Language Crisis in the Ryukyus (pp. 103-139). Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology

Philip Kendall

The Astronomical Journal

Rene Mendez

Maria Craig

Marcos Crispino

Merkuria Karyantina

Analéctica. Revista y Casa Editorial

Luiza Saraiva

Deborah NOLAN

Silvana Hrelia

Kirsten Nielsen

Software Engineering and Applications/ 831: Advances in Power and Energy Systems

Abdullah Abuhussein

International journal of engineering research and technology

Pratiwi Mutiara

Jean-Bernard Edel

European Journal of Social Work

Gregory Neocleous

Sociedad Y Economia

EDGAR ALEJANDRO QUIÑONEZ GARCIA

Souvenir Payung Bandung

toif tusongwawa

Scientia Agricola

Marcos Ventura Faria

Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences. 1999. HICSS-32. Abstracts and CD-ROM of Full Papers

AMIT KUMAR RUDRA

Journal of Protein Chemistry

Juan Ferrer

Bertha Lucia Avendano Prieto

arXiv (Cornell University)

Dentomaxillofacial Radiology

Claudio Leles

Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly

Whitney McIntyre Miller

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity