Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research

About the Journal

FQS is a peer-reviewed multilingual online journal for qualitative research. FQS issues are published three times a year. Selected single contributions and contributions to the journal's regular features FQS Reviews, FQS Debates, FQS Conferences and FQS Interviews are part of each issue. Additionally, thematic issues are published according to prior agreement with the FQS Editors .

FQS is an open-access journal, so all articles are available free of charge and published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- Current Issue: Current

- Back Issues: Archives

Please register if you are interested to receive our newsletter, distributed three times per year to inform about new publications and other news, important for qualitative researchers.

Current Issue

Single contributions, the spirit of fieldwork navigating alcohol consumption, abstinence and religious positionalities in social sciences research, participatory research with young people concerning sexuality, violence, and protection in (international) youth work: methodological reflections.

- HTML (Deutsch)

- PDF (Deutsch)

Doorways of Understanding: A Generative Metaphor Analysis

Subjectification of highly qualified professionals in the cuban realm of work: analyzing a two-sided process, symbolic boundaries and stigma management of alg ii recipients, transformative social research: a call for empirical engagement, being a foreigner during the covid-19 pandemic: researcher positionality in online interviews, racial matching in qualitative interviews: integrating ontological, ethical, and methodological arguments, multiple ways of seeing. reflections on an image-based q study on reconciliation in colombia, making sense of data interrelations in qualitative longitudinal and multi-perspective analysis, automatic transcription of english and german qualitative interviews, fqs debate: teaching and learning qualitative methods, current transformations of teaching and learning qualitative research: a discussion, fqs conferences, conference report: methodological education in social sciences and its value for professional practice, conference essay: exploring spaces of opportunity for everyday creativity, fqs reviews, review essay: about metaphors and monsters, review: louise ryan (2023). social networks and migration—relocations, relationships and resources.

Make a Submission

Information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Usage Statistics Information

We log anonymous usage statistics. Please read the privacy information for details.

Developed By

2000-2024 Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research (ISSN 1438-5627) Institut für Qualitative Forschung , Internationale Akademie Berlin gGmbH

Hosting: Center for Digital Systems , Freie Universität Berlin Funding 2023-2025 by the KOALA project

Privacy Statement Accessibility Statement

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

76k Accesses

28 Citations

72 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research

Patrik Aspers & Ugo Corte

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: what is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice?

Malin Eriksson, Mehdi Ghazinour & Anne Hammarström

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

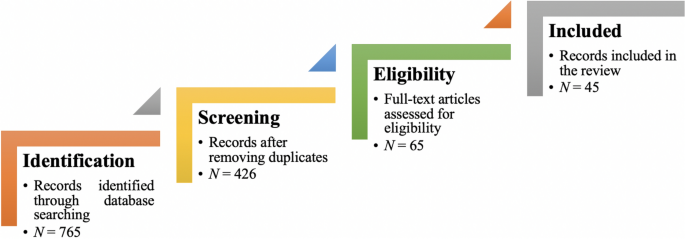

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

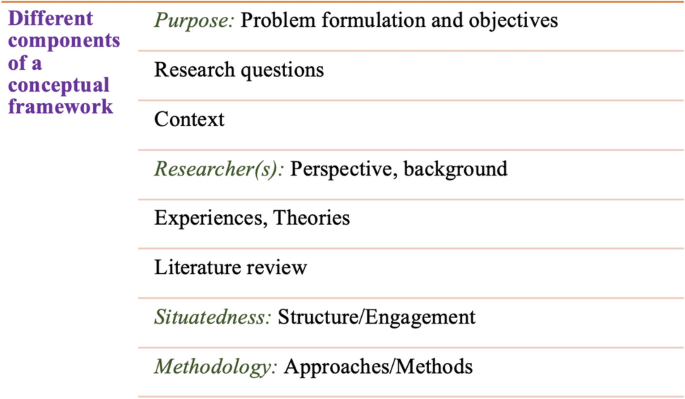

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 28 March 2022

The data revolution in social science needs qualitative research

- Nikolitsa Grigoropoulou 1 &

- Mario L. Small ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0601-1045 2

Nature Human Behaviour volume 6 , pages 904–906 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4637 Accesses

18 Citations

306 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

- Social sciences

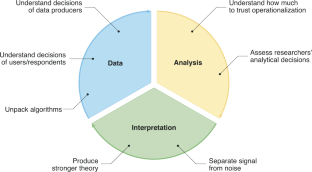

Although large-scale data are increasingly used to study human behaviour, researchers now recognize their limits for producing sound social science. Qualitative research can prevent some of these problems. Such methods can help to understand data quality, inform design and analysis decisions and guide interpretation of results.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Small, M. L., Akhavan, A., Torres, M. & Wang, Q. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 1622–1628 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Boyd, D. & Crawford, K. Inf. Commun. Soc. 15 , 662–679 (2012).

Lazer, D., Kennedy, R., King, G. & Vespignani, A. Science 343 , 1203–1205 (2014).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Alba, D. Tracking viral misinformation. The New York Times , https://go.nature.com/3Kszjyw (15 September 2021).

Strong, D. M., Lee, Y. W. & Wang, R. Y. Commun. ACM 40 , 103–110 (1997).

Ruths, D. & Pfeffer, J. Science 346 , 1063–1064 (2014).

Christin, A. Am. J. Sociol. 123 , 1382–1415 (2018).

AlShebli, B., Makovi, K. & Rahwan, T. Nat. Commun. 11 , 5855 (2020).

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D. & Simonsohn, U. Psychol. Sci. 22 , 1359–1366 (2011).

Breznau, N. et al. Observing many researchers using the same data and hypothesis reveals a hidden universe of uncertainty. Preprint at MetaArXiv, https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/cd5j9 (2021).

Salganik, M. J. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 8398–8403 (2020).

Salganik, M. J., Maffeo, L. & Rudin, C. Harv. Data Sci. Rev . 2.3 , https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.eecdfa4e (2020).

Blok, A. et al. Big Data Soc . 4 , https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717736337 (2017).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the University of Bremen Excellence Chairs programme for support.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

SOCIUM Research Center on Inequality and Social Policy, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

Nikolitsa Grigoropoulou

Department of Sociology, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Mario L. Small

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mario L. Small .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Grigoropoulou, N., Small, M.L. The data revolution in social science needs qualitative research. Nat Hum Behav 6 , 904–906 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01333-7

Download citation

Published : 28 March 2022

Issue Date : July 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01333-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Community teens’ covid-19 experience: implications for engagement moving forward.

- Colleen Stiles-Shields

- Karen M. Reyes

- Madeleine U. Shalowitz

Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Find My Rep

You are here

Qualitative Social Research Contemporary Methods for the Digital Age

- Vivienne Waller - Swinburne University of Technology, Australia

- Karen Farquharson - Swinburne University of Technology, Australia

- Deborah Dempsey - Swinburne University of Technology, Australia

- Description

Qualitative Social Research employs an accessible approach to present the multiple ways in which criticism enhances research practice. Packed full of relevant, 'real world' examples, it showcases the strengths and pitfalls of each research method, integrating the philosophical groundings of qualitative research with thoughtful overviews of a range of commonly used methods.

This book is ideal for students and prospective researchers and explains what makes qualitative sociological research practical, useful and ethical. It’s an essential guide to how to undertake research, use an appropriate research design and work with a range of qualitative data collection methods, and includes:

- detailed discussions of ethical issues

- references to new technologies in each chapter

- explanations of how to integrate online and visual methods with traditional data collection methods

- exercises to enhance learning

The authors use their many years’ experience in using a range of qualitative methods to conduct and teach research to demonstrate the value of critical thinking skills at all stages of the research process.

Qualitative Social Research provides a comprehensive and practical overview of qualitative research methodologies and I have no hesitation in recommending it as essential reading for students

Preview this book

Sample materials & chapters.

Qualitative Social Research: The aims of qualitative research

For instructors

Please select a format:

Select a Purchasing Option

- Electronic Order Options VitalSource Amazon Kindle Google Play eBooks.com Kobo

Related Products

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Engaging Crystallization in Qualitative Research An Introduction

- Laura L. Ellingson - Santa Clara University, USA

- Description

"This is the best book I have read in quite some time. Professor Ellingson writes clearly yet artfully and in a scholarly voice that is accessible to students and faculty alike. The weaving between description and illustrative case studies takes readers through the step-by-step journey of crystallization (as experienced and offered by Ellingson). The book is clearly grounded in philosophies of knowing and methods— yet, it offers practical strategies, questions, and choices for researchers." — Lynn M. Harter, Ohio University Engaging Crystallization in Qualitative Research , the first "how to" book to both explain and demonstrate crystallization methodology, offers a framework for blending grounded theory and other social scientific analyses with creative representations of data, such as narratives, poetry, and film. Author Laura L. Ellingson explores relevant epistemological questions that arise when crossing methodological boundaries, provides detailed steps for design and planning, offers guidelines for improving both social scientific and creative/artistic writing, and suggests strategies for targeting publication outlets for multigenre representations. Features

- Articulates the principles of crystallization and how it enables researchers to both represent multiple perspectives on a phenomenon and highlight the partial nature of all claims of truth

- Breaks down the qualitative research barriers between the grounded theorists and those who favor artistic, interpretive, and creative approaches, exemplifying the possibilities for all

- Demonstrates the rich possibilities for blending social scientific, creative/artistic, and critical approaches to research

- Provides hands-on strategies that help practitioners and students collect, analyze, and represent qualitative data through crystallization

- Explores ethical challenges, the political nature of research findings, and the need for social justice activism among researchers

- Illustrates concepts with exemplars, featuring cutting-edge research in social sciences, education, and allied health

Suitable for experienced practitioners and advanced students of qualitative methods, Engaging Crystallization in Qualitative Research is ideal for such courses as Intermediate/Advanced Qualitative Research, Ethnographic Methods, Grounded Theory, Field Research Methods, and Qualitative Inquiry.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

" [ This ] book emphasizes effective communication and how to articulate complex information to an audience. Although the book is intended primarily for qualitative researchers, I believe it may be an equally important work for quantitative researchers. In reading this book, I have gained a deeper appreciation for qualitative research in general and a better understanding of how different methods can be applied toward understanding truth."

"The book's key strength is its informed style and uplifting optimism about the future not only of qualitative research but of research at large...the book offers many ideas for researchers to play with and is a thorough and illuminating introduction to the theories, procedures, and politics of qualitative inquiry and publishing."

Did not meet the needs for dissertation research design, however I am considering the book for my advanced qualitative methods course.

- The first "how do" book that explains and demonstrates crystallization methodology.

- Breaks down the qualititative research barriers between the grounded theory "camp" and those who favor artistic, interpretive, creative approaches—exposing the fertile ground found between these two poles and exemplifying the possibilities for all.

- Extending upon the work presented in her multi-award-winning book, Communicating in the Clinic —wherein Ellingson modeled crystallization by alternating between grounded theory, ethnographic storytelling, and autoethnography—in this book she teaches others how to do it, providing practical guidance for researchers' and students' implementation, thereby de-mystifying the process.

Sample Materials & Chapters

Ch. 1 - Introduction to Crystallization

Ch. 4 - Strategies for Design

Ch. 8 - Publishing and Promoting Crystallization

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Qualitative social research in addictions publishing: Creating an enabling journal environment

a Centre for Research on Drugs and Health Behaviour, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of London, UK

Gerry V. Stimson

David moore.

b National Drugs Research Institute, Curtin University, Melbourne Office, Australia

Philippe Bourgois

c Richard Perry University Professor of Anthropology and Family and Community Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, USA

In 2005, the journal Addiction , one of the highest-ranking addiction journals, published a review of qualitative methods in addictions research ( Neale, Allen, & Coombes, 2005 ). This review noted that Addiction had published only three qualitative research papers in the previous year; around 2% of the research papers it had published in 2004. Accepting that “such marginality prompts uncomfortable questions”, the authors posed the possibility that some addiction journals might “directly or indirectly militate against the publication of qualitative research” (p. 1584). To begin to remedy this situation, the authors emphasised two challenges. First, they argued that qualitative researchers “should have confidence in the scientific rigor and value of their methods” and thus, should “not hesitate in writing up their data for any journal that will reach their target audience”. And second, they called upon addiction journals to “adopt policies and practices that will potentially encourage more qualitative submissions” (p. 1591).

Of course, the extent to which qualitative research is published in any particular journal is shaped by a variety of factors, including: the rate at which such papers are submitted; the scientific quality of submissions; the amount of research funding available to qualitative researchers; the scientific capital and impact accorded such work in any given addiction research culture; as well as how journal policy and disciplinary leanings shape reviewing and editorial decisions.

Interested to see how a selection of addiction journals compared, and taking a single year (2009), we estimated the proportion of published original research papers that employed qualitative methods ( Table 1 ). We selected the top eight ranked journals in the ‘social science’ category of the Thomson ISI impact factor (IF) ratings, supplemented by journals of relative high impact in the field of drug use or known to attract social research submissions. Accepting the limits of such a snapshot exercise, what we found overall is probably of little surprise: Qualitative research – at 7% (100/1338) of papers published – is a minority output of addiction journal publication. The proportion would have been even lower if we had sampled addiction journals outside the ‘social science’ category.

Qualitative research in addiction journals, 2009.

We also found that some journals publish more qualitative work than others. The addiction journal publishing the highest proportion of qualitative research papers – at 57% in 2009 – is the International Journal of Drug Policy ( Table 1 ), followed by Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy (36%) and the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs (34%). The addiction journals contributing least – at 1% or less – to qualitative research are Psychology of Addictive Behaviours , Addictive Behaviors , Addiction , and Drug and Alcohol Dependence . With the exception of the International Journal of Drug Policy , which has an IF of 2.5, the proportion of qualitative research published in any given journal is roughly inversely proportional to that journal’s IF. With the exception of one, all journals with an IF of over 2 published 3% or less research articles reporting qualitative data.

The marginality of qualitative research in addiction journals

The field of drug use and addiction has an established tradition in generating ground-breaking qualitative and ethnographic research that has crossed over into wider fields to inform social science methods and theories (for example, Agar, 1973 ; Becker, 1953 ; Lindesmith, 1938 ; Weinberg, 2005 ). Clearly, not all addiction journals are the same, and some are deliberately or otherwise more open to the publication of qualitative research. Different fields of addiction study – such as policy, health and harm – may orientate themselves better to qualitative and social research. But Table 1 implies that the potential outlets for the publication of qualitative research in addiction journals are limited, especially when the journal is influential in the field (with an IF above 2). Where else then is qualitative research on drug use and addiction being published?

It is our sense, especially when considering journals of record, that much original qualitative research – perhaps most – is submitted to generic social science, health and policy journals (for instance, Fraser & Treloar, 2006 ; Shannon et al., 2008 ; Weinberg, 2000 ). We know this too as authors (for instance, Bourgois, Prince, & Moss, 2004 ; Moore, 2009 ; Rhodes, Bernays, & Houmoller, 2010 ). We submit to social science journals by default as well as by desire. Addiction journals are often beyond our immediate consideration when submitting empirical qualitative research because they may not seem ‘social science’ enough or, conversely, our work may appear too theoretical, too critical, too reflexive, too subtle and complicated, or just too long. It is obviously important for social scientists to publish in social science journals but it is equally important, and arguably more so for addiction science, for social scientists to be publishing in addiction journals. The field of addiction science reflects the theoretical and methodological parochialism of the biological and laboratory sciences. It is in danger of developing outside the orbit of dramatic theoretical advances in critical approaches to understanding power relations and subjectivity formation occurring in the humanities and qualitative social sciences over the past decade (for example, Butler, 1997 ; Keane, 2002 ; Peterson & Bunton, 1997 ; Rose, 1996 ; Valverde, 1998 ).

As a consequence, not only are most addiction journals publishing little qualitative research ( Table 1 ), but they may be marginalising more theoretically grounded and methods-driven qualitative research. Most importantly, they may be failing to capture cutting edge work on the social inequity and structural forces shaping addiction. Surely, addiction journals wish to encourage rather than marginalise qualitative research that engages with current developments in social and cultural theory and methodology? For this, amongst other things, is what distinguishes the quality in qualitative research ( Seale, 1999 ).

These questions touch upon recurring debates on multi-disciplinary addictions research (for example, Bourgois, 1999 , 2002 ; Moore, 2002 ; Rhodes & Coomber, 2010 ), including those in Addiction ( McKeganey, 1995 ; Neale et al., 2005 ), and captured by journal ‘special issues’ specific to qualitative research (for instance, Moore & Maher, 2002 ; Rhodes & Moore, 2001 ). A critical point in these discussions concerns the ‘epistemology of method’. By epistemology, we refer to the ways in which we come to know things as well as how we demonstrate the legitimacy of that knowledge. In multidisciplinary debates, two positions tend to dominate: the representation of ‘interpretative’ qualitative research as paradigmatically distinct from, even incompatible with, ‘positivist’ quantitative research ( Guba & Lincoln, 1994 ), and a call for ‘pragmatism’ ( Hammersley, 1992 ; Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004 ). Pragmatism usually proffers a ‘horses for courses’ approach, wherein a plurality of methods are envisaged as a kind of ‘tool box’, selected according to what is fit for purpose ( Creswell, 2003 ; Hammersley, 1992 ; Miller, Strang, & Miller, 2010 ; Silverman, 1997 ). The pragmatist position, which sits comfortably inside narratives of evidence-based medicine, implies that differences in the epistemology of method are exaggerated as well as unhelpful. McKeganey, for example, has argued for reconciling differences between quantitative and qualitative methods in addictions research, suggesting that “divides” are “unhelpful”, and that “methodological identity” should not be preserved at “the cost of greater understanding” ( 1995 ). Neale et al. (2005) largely side-step questions of epistemology, instead positioning the challenge of mainstreaming qualitative methods as a problem of practice and technique rather than of the credibility and legitimacy afforded to different ways of knowing in addictions science.

Differences in the epistemology of method can make truly interdisciplinary research challenging, and perhaps even painful ( Bryman, 2007 ; Curtis, 2002 ; Mason, 2006 ; Moore, 2002 ). But differences are helpful too. There are many good examples of mixed-method research projects which embrace epistemological differences, including as a way of critiquing the methods they use and the evidence they produce ( Barbour, 1999 ; Mason, 2006 ). Embracing difference creates new flows between epistemology and method ( Bryman, 2001 ; Mason, 2006 ). There is increasing acceptance of post-positivism in quantitative research, as well as recognition of straight-forward realism in much applied qualitative research, and a growing respect for the need to reflect on how research questions and methods relate to epistemological assumptions. Collaborations between ethnography, epidemiology and mathematical modelling provide examples ( Agar, 2003 ; Bourgois et al., 2006 ; Ciccarone & Bourgois, 2003 ; Moore et al., 2009 ).

In our view, pragmatism alone is not enough. Social constructionist approaches are at once a commitment to illuminating how power, context and objectification shape knowledge, including in relation to addiction ( Bourgois, 1999 ). Fundamentally, and rather obviously, epistemological assumptions informing research cannot be masked by simply ignoring them ( Bryman, 2001 ; Hammersley, 1992 ). For instance, it makes no sense for pragmatists to imply, as some do, that ‘giving-up’ critical realism for the ‘pretence’ of realism is a necessary condition for fruitful multidisciplinary collaboration. We cannot simply choose to avoid epistemological differences or methodological identities. Quantitative realists may believe they capture objective truths about addiction, and qualitative researchers may wish for mainstream acceptance of social constructionist work, but it should be axiomatic that addiction journal publishing does not contribute to the marginalisation of constructionist critiques of addiction and addiction science. The mainstreaming of qualitative methods into specialist journals cannot, and should not, rest upon qualitative researchers suspending their attachment to social constructionist theory, writing in epistemological disguise or ‘dumbing down’ their analyses. We see addiction and addiction science as quintessentially social and historical constructions ( Courtwright, 2001 ; Reinarman, 1995 ), and a key role of qualitative research, through theoretically informed, systematic and grounded analyses, is to explore and demonstrate how particular assemblages of knowledge, practice and subjectivity come to be taken as ‘real’.

Addiction journal practices

Despite our comments above on how the epistemology of method unavoidably pervades addiction science (and all research), there may be a tendency to separate out such issues from the day-to-day practices of journal publishing. If research “does not exist in a bubble” ( Bryman, 2001 ), then neither does addiction research. If “methods are not simply neutral tools” ( Bryman, 2001 ), then neither are journal publishing practices. How might the nuts and bolts of addiction journal publishing shape opportunities to publish qualitative research?

Perhaps the single most important factor here is journal policy limiting article length. Text and documentary analyses require more words than quantitative analyses. Reliability in the reporting of qualitative research is accomplished through combining ‘low inference description’ with the display of data, to demonstrate systematic comparison and concept generation as well as to illustrate ideal, typical and negative cases ( Seale, 1999 ). Whilst coding is a method of reduction and concept organisation, the corpus of data is large. The need to demonstrate through critical and reflexive engagement with data how analyses were performed, and how grounded theories or concepts were generated, is fundamental to good analytical practice ( Charmaz, 2006 ; Seale, 1999 ). Narrative and discourse analyses, with their explicit focus on language and form, can demand even closer attention to textual data than thematic analyses. The danger, otherwise, is that the qualitative extract is reduced to no more than supplementary illustration, with qualitative analytical practices such as induction and iteration becoming opaque. This arguably feeds a common charge, especially amongst sceptics, that qualitative research appears under-analysed, even anecdotal, as well as beyond critical appraisal regarding its reliability and credibility.

Journal policy on article length may therefore not only act to limit qualitative research submissions, but crucially, the type and quality of work accepted. Obviously, it is not impossible to produce concise qualitative research reports, as illustrated by journals such as the British Medical Journal . But longer critical analyses are also necessary. There are multiple audiences for qualitative analyses—policy makers, practitioners, biomedical and laboratory scientists, as well as social scientists and social theorists. A diversity and flexibility in addiction journal publishing practices is required. The word guidance for research submissions issued by the addiction journals listed in Table 1 clusters around 3000–4000. Some journals – those tending to publish the least qualitative research – suggest maximum word lengths as low as 2000 ( Addictive Behaviors ) or 3500 ( Addiction ). It is difficult to see how such policies encourage varied forms of qualitative submission, or other forms of discursive historical and policy analyses. Only one journal we reviewed ( Contemporary Drug Problems ) sets no upper word limit.

Our own journal, the International Journal of Drug Policy , has been working to a guide of up to 5000, and “exceptionally”, 7000 words. We have recently revised our guide to authors to emphasise that we will consider submissions to a maximum of 8000 words, on a par with most social science journals, noting our openness to considering work from a diversity of social and other sciences. We now allow unstructured as well as structured abstracts. Our qualitative research submissions are reviewed by applied experts in qualitative, ethnographic and social science research. We reinforce our interest in considering submissions that are qualitative or ethnographic, as well as critical (such as those informed by science and technology studies), including narrative, historical and discourse-based analyses. We wish to open up opportunities for diversifying the qualitative research published in addiction journals.

In their review of qualitative addictions research, Neale et al. (2005) noted the need for addiction journals to publish statements welcoming qualitative research submissions, alongside adopting flexible policies regarding the structure and length of papers, and having qualitative research reviewed by appropriate social science experts. We endorse these recommendations, and encourage other addiction journals to do likewise. If multidisciplinary addiction journals are to better enable the publication of qualitative research (as well as other forms of discursive analysis), it is critical that editorial policies, practices and systems are supportive. A journal architecture is required that embraces such work, and this includes the sufficient incorporation of social science and qualitative expertise into editorial boards as well as reviewing and decision processes.

Neale and colleagues also ponder whether journals should set a per annum quota of journal space for qualitative research publication. This is difficult given that no addiction journal is the same, and each probably envisages its methodological leanings and scientific identity differently. But if journals claim a multidisciplinary ethos, perhaps a minimum publication quota expectation for different forms of research could be set, including for quantitative and qualitative analyses and for systematic reviews. If roughly 7% of research papers in addiction journals are qualitative ( Table 1 ), perhaps this could be taken as a minimum target for every journal publishing multidisciplinary addiction research.

Addiction science is dominated by biomedical and psychological approaches ( Miller et al., 2010 ). Despite a rich heritage, the social science of addiction, and qualitative research in particular, remains a peripheral voice in addiction journal publishing. Patterns of drug effect, use and dependency, as well as the effects of drug policies and interventions, do not obey universal laws, but are shaped by the social and cultural contexts in which they occur and help to produce. We need qualitative research to capture how drug use and addiction is lived and represented according to time and place. We need social constructionist research not only to understand the social bases of addiction but also of addiction science. We call upon addiction journal editors to reflect upon their practices of addiction journal publishing. We call upon addiction journals to develop editorial policies supportive of the publication of qualitative social research, and to facilitate active engagement with social theories informing our knowledge in the field of addiction studies. At the International Journal of Drug Policy , we wish to strengthen our ethos of multidisciplinarity whilst continuing to build our publication as a primary avenue for qualitative and social science research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rachael Parker for her help compiling Table 1 , and to the following for their comments on an earlier draft: Joanne Neale; Carla Treloar; Magdalena Harris; and Adam Fletcher.

Philippe Bourgois acknowledges funding support from NIH grants DA 10164, DA 027204, DA 027689 and CRP ID08-SF-049. Tim Rhodes acknowledges funding support from the Department of Health to the Centre for Research on Drugs and Health Behaviour at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare a vested interest in the International Journal of Drug Policy , as Editors-In-Chief (Tim Rhodes, Gerry Stimson), and as Associate Editors (David Moore, Philippe Bourgois). David Moore also declares his role as Editor at Contemporary Drug Problems , where Philippe Bourgois and Tim Rhodes serve on the editorial board.

- Agar M. Ripping and Running: A Formal Ethnography of Urban Heroin Users. New York: Academic Press; 1973. [ Google Scholar ]

- Agar M. Qualitative epidemiology. Qualitative Health Research. 2003; 13 :974–986. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barbour RS. The case of combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in health services research. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 1999; 4 :39–42. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Becker H. Becoming a marijuana user. American Journal of Sociology. 1953; 59 :235–242. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourgois P. Theory, method and power in drug and HIV prevention research: A participant’-observer’s critique. Substance Use and Misuse. 1999; 33 :2323–2351. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourgois P. Anthropology and epidemiology on drugs: The challenges of cross-methodological and theoretical dialogue. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002; 13 :259–269. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourgois P, Prince B, Moss A. The everyday violence of hepatitis C among young women who inject drugs in San Francisco. Human Organization. 2004; 63 :253–264. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourgois P, Martinez A, Kral A, Edlin B, Schonberg J, Ciccarone D. Reinterpreting ethnic patterns among white and African American men who inject heroin: A social science of medicine approach. PLoS Medicine. 2006; 3 :e452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030452. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bryman A. Quantity and quality in social research. London: Unwin Hyman; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bryman A. Barriers to integrating quantitative and qualitative research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007; 1 :8–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- Butler J. The psychic life of power. San Francisco: Stanford University Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage; 2006. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ciccarone D, Bourgois P. Explaining the geographical variation of HIV among injection drug users in the United States. Substance Use and Misuse. 2003; 38 :2049–2063. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Courtwright DT. Forces of habit: Drugs and the making of the modern world. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell J. Research designs: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. London: Sage; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Curtis R. Coexisting in the real world: The problems, surprises and delights of being an ethnographer on a multidisciplinary research project. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002; 13 :297–310. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fraser S, Treloar C. “Spoiled identity” in hepatitis C infection: The binary logic of despair. Critical Public Health. 2006; 16 :99–110. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. London: Sage; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hammersley M. What’s wrong with ethnography? London: Routledge; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson R, Onwuegbuzie A. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher. 2004; 33 :14–26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keane H. What’s wrong with addiction? Melbourne: Melbourne University Press; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lindesmith A. A sociological theory of drug addiction. American Journal of Sociology. 1938; 43 :593–609. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mason J. Mixing methods in a qualitatively-driven way. Qualitative Research. 2006; 6 :9–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- McKeganey N. Quantitative and qualitative research in the addictions: An unhelpful divide. Addiction. 1995; 90 :749–751. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller PG, Strang J, Miller PM. Introduction. In: Miller PG, Strang J, Miller PM, editors. Addiction research methods. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore D. Ethnography and the Australian drug field: Emaciation, appropriation and multidisciplinary myopia. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002; 13 :271–284. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore D. ‘Workers’, ‘clients’ and the struggle over needs: Understanding encounters between service providers and injecting drug users in an Australian city. Social Science and Medicine. 2009; 68 :1161–1168. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore D, Maher L. Ethnography and multidisciplinarity in the drug field. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002; 13 :245–247. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore D, Dray A, Green R, Hudson S, Jenkinson R, Siokou C, et al. Extending drug ethno-epidemiology using agent-based modelling. Addiction. 2009; 104 (12):1991–1997. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Neale J, Allen D, Coombes L. Qualitative research methods within the addictions. Addiction. 2005; 100 :1584–1593. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peterson A, Bunton R, editors. Foucault, health and medicine. London: Routledge; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reinarman C. Addiction as accomplishment: The discursive construction of disease. Addiction Research and Theory. 1995; 13 :307–320. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rhodes T, Coomber R. Qualitative methods and theory in addictions research. In: Miller G, Strang J, Miller P, editors. Addiction research methods. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 59–78. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rhodes T, Moore D. On the qualitative in drugs research. Addiction Research and Theory. 2001; 9 :279–299. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rhodes T, Bernays S, Houmoller K. Parents who use drugs: Accounting for damage and its limitation. Social Science and Medicine. 2010; 71 :1489–1497. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rose N. Inventing ourselves: Psychology, power and personhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Seale C. Quality in qualitative research. London: Sage; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Bright V, Allinot S, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social Science and Medicine. 2008; 66 :911–921. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Silverman D. The logics of qualitative research. In: Miller G, Dingwall R, editors. Context and method in qualitative research. London: Sage; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Valverde M. Diseases of the will. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weinberg D. ‘Out there’: The ecology of addiction in drug abuse treatment discourse. Social Problems. 2000; 47 :606–621. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weinberg D. Of others inside: Insanity, addiction and belonging in America. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

COMMENTS

Qualitative Social Work provides a forum for those interested in qualitative research and evaluation and in qualitative approaches to practice. The journal facilitates interactive dialogue and integration between those interested in qualitative … | View full journal description. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics ...

Qualitative Research is a peer-reviewed international journal that has been leading debates about qualitative methods for over 20 years. The journal provides a forum for the discussion and development of qualitative methods across disciplines, publishing high quality articles that contribute to the ways in which we think about and practice the craft of qualitative research.

The journal Qualitative Sociology is dedicated to the qualitative interpretation and analysis of social life. The journal offers both theoretical and analytical research, and publishes manuscripts based on research methods such as interviewing, participant observation, ethnography, historical analysis, content analysis and others which do not rely primarily on numerical data.

About the Journal. FQS is a peer-reviewed multilingual online journal for qualitative research.FQS issues are published three times a year. Selected single contributions and contributions to the journal's regular features FQS Reviews, FQS Debates, FQS Conferences and FQS Interviews are part of each issue. Additionally, thematic issues are published according to prior agreement with the FQS ...

The International Journal of Qualitative Methods is the peer-reviewed interdisciplinary open access journal of the International Institute for Qualitative Methodology (IIQM) at the University of Alberta, Canada. The journal, established in 2002, is an eclectic international forum for insights, innovations and advances in methods and study designs using qualitative or mixed methods research.

While many books and articles guide various qualitative research methods and analyses, there is currently no concise resource that explains and differentiates among the most common qualitative approaches. We believe novice qualitative researchers, students planning the design of a qualitative study or taking an introductory qualitative research course, and faculty teaching such courses can ...

A peer-reviewed, open access journal in qualitative research methods, methodology, mixed methods, visual research methods, narrative research methods & data analysis. This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience. ... Social Sciences: Social sciences (General)

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then ...

Qualitative Research was established in 2001 by Sara Delamont and Paul Atkinson. The journal was founded to offer a critical and reflective gaze on methodological approaches, understandings and engagements, and worked to counter tendencies that imagined qualitative research could become a taken for granted set of precepts and procedures.

1. Beyond sole or primary method, there are a few instances of qualitative surveys being used in multi-method qualitative designs - essentially as a 'substitute' for, or to extend the reach of, interviews or focus groups as the primary data collection technique (e.g., Clarke & Demetriou, Citation 2016; Coyle & Rafalin, Citation 2001; Whelan, Citation 2007).

Qualitative Social Work provides a forum for those interested in qualitative research and evaluation and in qualitative approaches to practice. The journal includes the following regular special features: Responses to previous articles in the journal or contributions that initiate discussion of current research and practice issues.

SSM - Qualitative Research in Health is a peer-reviewed, open access journal that publishes international and interdisciplinary qualitative research, methodological, and theoretical contributions related to medical care, illness, disease, health, and wellbeing from across the globe. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health is edited by Stefan Timmermans, a Senior Editor at Social Science & Medicine.