Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

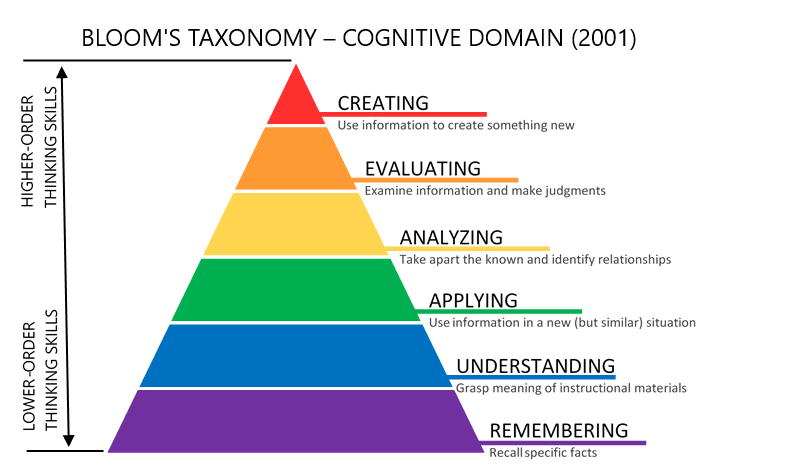

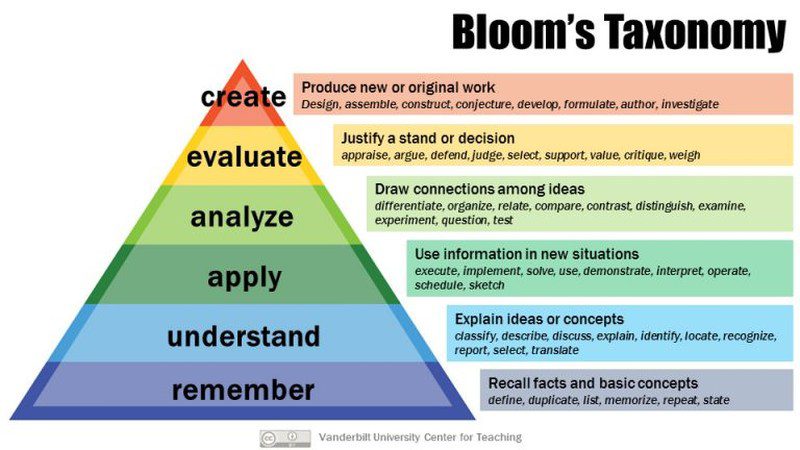

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

- Members Newsfeed

20 Critical Thinking Activities for Middle Schoolers

- Middle School Education

Introduction:

Critical thinking is vital for middle school students, as it helps them develop problem-solving skills, make informed decisions, and understand different perspectives. Integrating critical thinking activities into classroom learning experiences can greatly enhance students’ cognitive abilities. The following are 20 engaging critical thinking activities designed for middle school students.

1. Brain Teasers: Use age-appropriate puzzles to challenge students’ cognitive abilities and encourage them to find creative solutions.

2. Socratic Circles: Divide the class into groups and encourage them to participate in a philosophical discussion on a given topic, asking questions that stimulate critical thinking and deeper understanding.

3. Compare and Contrast: Assign two similar but different texts for students to compare and contrast, analyzing similarities and differences between each author’s perspective.

4. What-If Questions: Encourage children to think critically about hypothetical scenarios by asking what-if questions, such as “What if the internet didn’t exist?”

5. Debate Club: Organize a debate club where students are encouraged to research and defend differing viewpoints on a topic.

6. Mind Mapping: Teach students how to create a mind map – a visual representation of their thoughts – to help them brainstorm complex issues effectively.

7. Mystery Bag: In small groups, give students a bag containing several random objects and ask them to invent an innovative product or story using all items in the bag.

8. Critical Thinking Journal: Have students maintain journals where they analyze their thought processes after completing activities, promoting self-reflection and metacognition.

9. Moral Dilemmas: Present students with moral dilemmas, requiring them to weigh pros and cons before making ethical decisions.

10. Fact or Opinion?: Give students various statements and ask them to differentiate between fact or opinion, helping them build critical thinking skills when handling information.

11. Research Projects: Assign project topics that require deep research from multiple sources, developing students’ abilities to sift through information and synthesize their findings.

12. Think-Pair-Share: Have students think individually about a complex question, then pair up to discuss their thoughts, and finally share with the class.

13. Art Interpretation: Display an artwork and ask students to interpret its meaning, theme, or message, pushing them to look beyond the surface.

14. Reverse Role Play: Assign roles for a scenario where students exchange positions (e.g., teacher-student, parent-child), fostering empathetic understanding and critical thinking skills.

15. Critical Evaluation of Media: Analyze news articles, commercials, or social media posts by asking questions about their purpose, target audience, and accuracy.

16. Six Thinking Hats: Teach students Edward de Bono’s “Six Thinking Hats” technique to improve critical thinking by exploring diverse perspectives when solving problems.

17. Analogy Building: Encourage students to create analogies from one concept to another, enhancing abstract thinking and problem-solving abilities.

18. Current Events Analysis: Keep track of current events and have students critically evaluate news stories or blog posts to encourage informed decision-making in real-world contexts.

19. Brainstorming Sessions: Hold group brainstorming sessions where students invent solutions for complex problems while practicing active listening and critical thinking.

20. Reflection Activities: Use reflective writing prompts at the end of lessons or activities to foster metacognition, self-awareness, and the development of critical thinking skills.

Conclusion:

Critical thinking activities are vital for middle schoolers as they foster intellectual growth and prepare them for future learning experiences. By incorporating these 20 activities into your classroom curriculum, you can help students develop essential critical thinking skills that will serve them throughout their academic careers and beyond.

Related Articles

Starting at a new school can be an exciting yet nerve-wracking experience…

Introduction: As middle schoolers transition into more independence, it's crucial that they…

1. Unpredictable Growth Spurts: Middle school teachers witness students entering their classrooms…

Pedagogue is a social media network where educators can learn and grow. It's a safe space where they can share advice, strategies, tools, hacks, resources, etc., and work together to improve their teaching skills and the academic performance of the students in their charge.

If you want to collaborate with educators from around the globe, facilitate remote learning, etc., sign up for a free account today and start making connections.

Pedagogue is Free Now, and Free Forever!

- New? Start Here

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Registration

Don't you have an account? Register Now! it's really simple and you can start enjoying all the benefits!

We just sent you an Email. Please Open it up to activate your account.

I allow this website to collect and store submitted data.

- Our Mission

Boosting Critical Thinking Across the Curriculum

Visible thinking routines that encourage students to document and share their ideas can have a profound effect on their learning.

In my coaching work with schools, I am often requested to model strategies that help learners think deeply and critically across multiple disciplines and content areas. Many teachers are looking to adapt research-based methods to help students think about content in meaningful ways by making connections to previous learning, asking relevant questions, displaying understanding through learning artifacts , and identifying their challenges with the material.

Educator Alfred Mander said, “Thinking is skilled work. It is not true that we are naturally endowed with the ability to think clearly and logically—without learning how and without practicing.”

Visible thinking routines can be an excellent and simple way to start using systematic but flexible approaches to teaching thinking dispositions to young people at any grade level. Focusing on thinking types, powerful routines can strengthen learners’ ability to analyze, synthesize (design), and question effectively. Classroom teachers want these skills to become habits, making students the most informed stakeholder in their own learning.

Not to be confused with visible learning research by John Hattie , Visible Thinking is a research-based initiative by Harvard’s Project Zero with more than 30 routines aimed at making learning the consequence of good thinking dispositions . Students begin to comprehend content through thinking routines composed of short questions or a series of steps. During routines, their learning becomes visible because their ideas are documented, voiced, discussed with others, and reflected on.

For example, the routine See, Think, Wonder can be used to get students to analyze and interpret graphs, text, infographics, or video during the entry event of project-based learning units or daily lessons. Guiding students to have rich and lively discussions about their thoughts, interpretations, and wonderings (questions) can help teachers decide on appropriate lessons and next steps.

Another effective visible thinking routine is Connect, Extend, Challenge (CEC). Learners can use CEC to organize, clarify, and simplify complex information on graphic organizers. The graphic organizer becomes a kinesthetic activity for creating an informational artifact that students can refer to as the lesson or unit progresses.

Here are some creative but simple ways to carry out these two routines across multiple classrooms.

See, Think, Wonder

See, Think, Wonder can be leveraged as a thinking routine to launch engagement and inquiry in daily lessons by introducing an interesting object (graphic, artifact, etc.). The idea is for students to think carefully about why the object looks or is a certain way. Teachers introduce the following question prompts to guide students’ thinking:

- What do you see?

- What do you think about that?

- What does it make you wonder?

When the routine is new, sometimes young children may not know where to begin expressing themselves—this is where converting the above question prompts into sentence stems, “I see…,” “I think…,” and “I wonder…,” comes into play. For students struggling with analytical skills, it’s empowering for them to accept themselves where they currently are—learning how to analyze critically can be achieved over time and with practice. Teachers can help them build confidence with positive reinforcement .

Adapt the routine to meet the needs of your kids, which may be to have them work individually or to engage with classmates. I use it frequently—especially when introducing emotionally compelling graphics to students learning about environmental issues (e.g., the UN’s Goals for Sustainable Development) and social issues . This is useful in helping them better understand how to interpret graphs, infographics, and what’s happening in text and visuals. Furthermore, it also promotes interpretations, analysis, and questioning.

Content teachers can use See, Think, Wonder to get learners thinking critically by introducing graphics that reinforce essential academic information and follow up the routine with lessons and scaffolds to support students’ ideas and interpretations.

Connect, Extend, Challenge

CEC is a powerful visible learning routine to help students connect previous learning to new learning and identify where they are struggling in various educational concepts. Taking stock of where they are stuck in the material is as vital as articulating their connections and extensions. Again, they might struggle initially, but here’s where front-loading vocabulary and giving them time to talk through challenges can help.

A good place to introduce CEC is after students have analyzed or observed something new. This works as a natural next step to have them dig deeper with reflection and use what they learned in the analysis process to create their own synthesis of ideas. I also like to use CEC after engaging them in the See, Think, Wonder routine and at the end of a unit.

Again, learners can work individually or in small groups. Teachers can also have them move into the routine after reading an article or some form of targeted informational text where the learning is critical to moving forward (e.g., proportional relationships, measurement, unit conversion). Regardless of your approach, Project Zero suggests having learners reflect on the following question prompts:

- How is the _____ connected to something you already know?

- What new ideas or impressions do you have that extended your thinking in new directions?

- What is challenging or confusing? What do you need to improve your understanding?

I like to have learners in small groups answer a version of the question prompts in a simple three-column graphic organizer. The graphic organizer can also become a road map for prioritizing the next steps in learning for students of all ages. Here are some visual examples of how I used the activity with educators in a professional development session targeting emotional intelligence skills.

More Visible Thinking Resources

- Project Zero’s Thinking Routine Toolbox : Access to core thinking routines

- Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for All Learners , by Ron Ritchhart, Mark Church, and Karin Morrison

- Creating Cultures of Thinking: The 8 Forces We Must Master to Truly Transform Our Schools , by Ron Ritchhart

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, teaching critical thinking skills.

The pervasiveness of social media has significantly changed how people receive and understand information. By steering people to content that’s similar to what they have already read, algorithms create echo chambers that can hinder critical thinking. Consequently, the person may not develop critical thinking skills or be able to refine the abilities they already possess.

Teachers can act as the antidote to the algorithms by strengthening their focus on teaching students to think critically. The following discusses how to teach critical thinking skills and provides resources for teachers to help their students.

What is critical thinking?

Oxford: Learner’s Dictionaries defines critical thinking as “the process of analyzing information in order to make a logical decision about the extent to which you believe something to be true or false.” A critical thinker only forms an opinion on a subject after first understanding the available information and then refining their understanding through:

- Comparisons with other sources of information

A person who is capable of critical thought relies entirely on scientific evidence, rather than guesswork or preconceived notions.

Key critical thinking skills

There isn’t a definitive list of key critical thinking skills, but Bloom’s Taxonomy is often used as a guide and illustration. It starts with base skills, such as remembering and understanding, and rises to optimal skills that include evaluating and creating.

- Remembering: Recalling specific facts

- Understanding: Grasping the information’s meaning

- Applying: Using the information in a new but similar situation

- Analyzing: Identifying connections between different source materials

- Evaluating: Examining the information and making judgments

- Creating: Using the information to create something new

Promoting critical thinking in the classroom

A Stanford Medicine study from 2022 finds that one quarter of children aged 10.7 years have mobile phones. This figure rises to 75% by age 12.6 and almost 100% by age 15. Consequently, children are routinely exposed to powerful algorithms that can dull their critical thinking abilities from a very young age.

Teaching critical thinking skills to elementary students can help them develop a way of thinking that can temper the social media biases they inevitably encounter.

At the core of teaching critical thinking skills is encouraging students to ask questions. This can challenge some educators, who may be tempted to respond to the umpteenth question on a single subject with “it just is.” Although that’s a human response when exasperated, it undermines the teacher’s previous good work.

After all, there’s likely little that promotes critical thinking more than feeling safe to ask a question and being encouraged to explore and investigate a subject. Dismissing a question without explanation risks alienating the student and those witnessing the exchange.

How to teach critical thinking skills

Teaching critical thinking skills takes patience and time alongside a combination of instruction and practice. It’s important to routinely create opportunities for children to engage in critical thinking and to guide them through challenges while providing helpful, age-appropriate feedback.

The following covers several of the most common ways of teaching critical thinking skills to elementary students. Teachers should use an array of resources suitable for middle school and high school students.

Encourage curiosity

It’s normal for teachers to ask a question and then pick one of the first hands that rise. But waiting a few moments often sees more hands raised, which helps foster an environment where children are comfortable asking questions. It also encourages them to be more curious when engaging with a subject simply because there’s a greater probability of being asked to answer a question.

It’s important to reward students who demonstrate curiosity and a desire to learn. This not only encourages the student but also shows others the benefits of becoming more involved. Some may be happy to learn whatever is put before them, while others may need a subject in which they already have an interest. Using real-world examples develops curiosity as well because children can connect these with existing experiences.

Model critical thinking

We know children model much of their behavior on what they see and hear in adults. So, one of the best tools in an educator’s toolbox is modeling critical thinking. Sharing their own thoughts as they work through a problem is a good way for teachers to help children see a workable thought process they can mimic. In time, as their confidence and experience grow, they will develop their own strategies.

Encourage debate and discussion

Debating and discussing in a safe space is one of the most effective ways to develop critical thinking skills. Assigning age-appropriate topics, and getting each student to develop arguments for and against a position on that topic, exposes them to different perspectives.

Breaking classes into small groups where students are encouraged to discuss the topic is also helpful, as small groups often make it easier for shy children to give their opinions. The “think-pair-share” method is another strategy that helps encourage students hiding out in class to come out of their shells.

Provide problem-solving opportunities

Creating tailored problem-solving opportunities helps children discover solutions rather than become frustrated by problems they don’t yet understand. Splitting classes into groups and assigning each an age-appropriate real-world problem they can analyze and solve is a good way of developing critical thinking and team working skills. Role-playing and simulation activities are engaging and fun because the children can pretend to be different people and act out scenarios in a safe environment.

Teach children how to ask the right questions

Learning how to ask the right questions is a vital critical-thinking skill. Questions should be open-ended and thought-provoking. Students should be taught different question stems, such as:

- “What if …?”

- “Can you explain …?”

- “What would happen if …?”

- “What do you think about …?”

Teachers should be aware of students who don’t use these stems. A gentle reminder of how to phrase a question can impact the answer received.

Encourage independent thinking

Critical and independent thinking are partners that are more effective together than either can be apart. To encourage independent thinking, teachers should allow children to pick some of their own topics of study, research, and projects .

Helping students identify and select different ways to complete an assignment can build their confidence. They should be persuaded to think of as many solutions to problems as possible, as this can open their minds to a wider scope of opportunities.

Provide feedback

Constructive feedback is a crucial part of the learning process. The following list summarizes key strategies that teachers can apply to encourage students through feedback:

- Identify what the child did well and what needs improving.

- Provide feedback as soon as possible after the task or assignment.

- Use positive and encouraging language devoid of criticism or negative language.

- Offer specific suggestions for improvement.

- Provide positive and negative feedback and focus on how to progress without dwelling on mistakes.

- Ensure the feedback is easy to understand and give examples if necessary.

- Be consistent with feedback for all students to avoid being seen as having favorites.

- Listen to the student’s responses to feedback and be open to their perspective.

A mind muscle

Finally, critical thinking is a mind muscle. If it is not exercised, it gets weak, and intellectual laziness takes its place. Teachers might consider asking students to present instances of how they used critical thinking outside of the classroom, which provides practice and reminds the students that these skills aren’t only for the classroom.

You may also like to read

- Critical Thinking Resources for Middle School Teachers

- Critical Thinking Resources for High School Teachers

- Teaching Critical Thinking Through Debate

- Build Critical Thinking Skills With Believing and Doubting Games

- Try These Tips to Improve Students' Critical Thinking Skills

- Teaching Styles That Require Abstract Thinking

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

- PhD Programs for Education

- Online & Campus Master's in Special Education

- Certificates in Special Education

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Family Life

- Teaching Children Skills

How to Teach Critical Thinking

Last Updated: September 28, 2023 Approved

This article was co-authored by Jai Flicker . Jai Flicker is an Academic Tutor and the CEO and Founder of Lifeworks Learning Center, a San Francisco Bay Area-based business focused on providing tutoring, parental support, test preparation, college essay writing help, and psychoeducational evaluations to help students transform their attitude toward learning. Jai has over 20 years of experience in the education management industry. He holds a BA in Philosophy from the University of California, San Diego. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article received 11 testimonials and 100% of readers who voted found it helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 293,486 times.

If you want to teach your students critical thinking, give them opportunities to brainstorm and analyze things. Classroom discussions are a great way to encourage open-mindedness and creativity. Teach students to ask "why?" as much as possible and recognize patterns. An important part of critical thinking is also recognizing good and bad sources of information.

Encouraging Students to Have an Open Mind

- For example, ask students an open-ended question like, "What would be a good way to get more people to recycle in the school?"

- Whether or not it's realistic, offer praise for an inventive answer like, "we could start to make a giant sculpture out of recyclable things in the middle of the school. Everyone will want to add to it, and at the end of the year we can take pictures and then break it down to bring to the recycling plant."

- Try including a brief creative exercise in the beginning of class to help get their minds working. For example, you could ask students to identify 5 uses for a shoe besides wearing it.

- For instance, make columns to name the good things about both a camping trip and a city excursion, then have students think about a happy medium between the two.

Helping Students Make Connections

- For instance, environmental themes may come up in science, history, literature, and art lessons.

- If you are teaching geometry, then you might ask if they have ever seen a building that resembles the shapes you are teaching about. You could even show them some images yourself.

- Explain to your students how the clues and their own personal influences form their final conclusions about the picture.

- For instance, show students a picture of a man and woman shaking hands in front of a home with a "For Sale" sign in front of it. Have students explain what they think is happening in the picture, and slowly break down the things that made them reach that conclusion.

- "To take a train."

- "To get to the city."

- "To meet his friend."

- "Because he missed him."

- "Because he was lonely."

- On a more advanced level, students will benefit from interrogating their research and work to determine its relevance.

Teaching Students About Reliable Information

- For instance, if a student says that there are fewer libraries than there used to be, have them provide some actual statistics about libraries to support their statement.

- Encourage students to ask the simple question, "Who is sharing this information, and why?"

- For instance, an advertisement for a low calorie food product may be disguised as a special interest television segment about how to lose weight on a budget.

- The date it was published, whether or not it has been updated, and how current the information is. Tell students where to find this information on the website.

- What the author's qualifications are. For instance, a medical article should be written by a doctor or other medical professional.

- If there is supporting evidence to back up what the writer says. Sources should always have information to back them up, especially when the source is something your students find on the internet.

- For example, if your students are reviewing the political viewpoint of a senator in the USA, ask your students to look up donations provided to that senator from any special interest groups. This may provide your students with insight into the reasons for the senator’s views.

How Do You Improve Critical Thinking Skills?

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.scholastic.com/parents/resources/article/thinking-skills-learning-styles/think-about-it-critical-thinking

- ↑ Jai Flicker. Academic Tutor. Expert Interview. 20 May 2020.

- ↑ https://www.weareteachers.com/10-tips-for-teaching-kids-to-be-awesome-critical-thinkers/

- ↑ https://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/2016/11/06/three-tools-for-teaching-critical-thinking-and-problem-solving-skills/

- ↑ http://www.pbs.org/now/classroom/lessonplan-07.html

- ↑ http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/11/23/503129818/study-finds-students-have-dismaying-inability-to-tell-fake-news-from-real

- ↑ http://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/ptn/2017/05/fake-news.aspx

About This Article

To teach critical thinking, start class discussions by asking open-ended questions, like "What does the author mean?" Alternatively, have your students make lists of pros and cons so they can see that two conflicting ideas can both have merit. You can also encourage your students to think more deeply about their own reasoning by asking them “Why?” 5 times as they explain an answer to you. Finally, teach students to figure out whether information, especially from online sources, is reliable by checking to see if it comes from a trusted source and is backed by evidence. For more from our reviewer on how to help students make connections that lead to more critical thinking, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Linda Mercado de Martell

Jul 24, 2017

Did this article help you?

Saeful Basri

Dec 21, 2016

Jan 23, 2017

Liebe Brand

Jul 23, 2016

Dec 14, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

How to teach Critical Thinking: Lesson plans for teachers

Knowing how to teach critical thinking is not always clear. These critical thinking lesson plans will help teachers build the critical thinking skills that their students need to become better engaged and informed global citizens.

The plans were developed in collaboration with psychology and brain researchers at Indiana University and with teachers across the country. All of our lesson plans are free to download, use and share. Primarily for middle schools, the topics range from cognitive biases to common logical fallacies, to subject-specific lessons in math, sciences, and social studies.

We invite you to check out our library of lessons, to share any thoughts and feedback that you might have

Teaching about control groups

Teaching about the confirmation bias

Teaching about the cognitive bias called overgeneralization

Using Unit Rates and Math to teach critical thinking

Critical Thinking and Statistics

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills

Social Media and the Confirmation Bias

Experimenter Bias in Science

Critical Thinking About Science News

Common Logical Fallacies in Science (Grades 6-8)

Common Logical Fallacies in Math (Grades 6-8)

Using Questions to Foster Critical Thinking in Science (Grades 6-8)

Teaching About Common Biases & Fallacies Using Social Studies (Grade 6)

TEACHING ABOUT COMMON BIASES & FALLACIES USING MATH (Grade 6)

TEACHING ABOUT COMMON BIASES & FALLACIES USING MATH (Grade 5)

Teaching About Common Biases & Fallacies Using Social Studies (Grade 4)

Teaching About Common Biases & Fallacies Using Math (Grade 4)

Privacy overview.

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

FREE Poetry Worksheet Bundle! Perfect for National Poetry Month.

5 Critical Thinking Skills Every Kid Needs To Learn (And How To Teach Them)

Teach them to thoughtfully question the world around them.

Little kids love to ask questions. “Why is the sky blue?” “Where does the sun go at night?” Their innate curiosity helps them learn more about the world, and it’s key to their development. As they grow older, it’s important to encourage them to keep asking questions and to teach them the right kinds of questions to ask. We call these “critical thinking skills,” and they help kids become thoughtful adults who are able to make informed decisions as they grow older.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking allows us to examine a subject and develop an informed opinion about it. First, we need to be able to simply understand the information, then we build on that by analyzing, comparing, evaluating, reflecting, and more. Critical thinking is about asking questions, then looking closely at the answers to form conclusions that are backed by provable facts, not just “gut feelings” and opinion.

Critical thinkers tend to question everything, and that can drive teachers and parents a little crazy. The temptation to reply, “Because I said so!” is strong, but when you can, try to provide the reasons behind your answers. We want to raise children who take an active role in the world around them and who nurture curiosity throughout their entire lives.

Key Critical Thinking Skills

So, what are critical thinking skills? There’s no official list, but many people use Bloom’s Taxonomy to help lay out the skills kids should develop as they grow up.

Source: Vanderbilt University

Bloom’s Taxonomy is laid out as a pyramid, with foundational skills at the bottom providing a base for more advanced skills higher up. The lowest phase, “Remember,” doesn’t require much critical thinking. These are the skills kids use when they memorize math facts or world capitals or practice their spelling words. Critical thinking doesn’t begin to creep in until the next steps.

Understanding requires more than memorization. It’s the difference between a child reciting by rote “one times four is four, two times four is eight, three times four is twelve,” versus recognizing that multiplication is the same as adding a number to itself a certain number of times. Schools focus more these days on understanding concepts than they used to; pure memorization has its place, but when a student understands the concept behind something, they can then move on to the next phase.

Application opens up whole worlds to students. Once you realize you can use a concept you’ve already mastered and apply it to other examples, you’ve expanded your learning exponentially. It’s easy to see this in math or science, but it works in all subjects. Kids may memorize sight words to speed up their reading mastery, but it’s learning to apply phonics and other reading skills that allows them to tackle any new word that comes their way.

Analysis is the real leap into advanced critical thinking for most kids. When we analyze something, we don’t take it at face value. Analysis requires us to find facts that stand up to inquiry, even if we don’t like what those facts might mean. We put aside personal feelings or beliefs and explore, examine, research, compare and contrast, draw correlations, organize, experiment, and so much more. We learn to identify primary sources for information, and check into the validity of those sources. Analysis is a skill successful adults must use every day, so it’s something we must help kids learn as early as possible.

Almost at the top of Bloom’s pyramid, evaluation skills let us synthesize all the information we’ve learned, understood, applied, and analyzed, and to use it to support our opinions and decisions. Now we can reflect on the data we’ve gathered and use it to make choices, cast votes, or offer informed opinions. We can evaluate the statements of others too, using these same skills. True evaluation requires us to put aside our own biases and accept that there may be other valid points of view, even if we don’t necessarily agree with them.

In the final phase, we use every one of those previous skills to create something new. This could be a proposal, an essay, a theory, a plan—anything a person assembles that’s unique.

Note: Bloom’s original taxonomy included “synthesis” as opposed to “create,” and it was located between “apply” and “evaluate.” When you synthesize, you put various parts of different ideas together to form a new whole. In 2001, a group of cognitive psychologists removed that term from the taxonomy , replacing it with “create,” but it’s part of the same concept.

How To Teach Critical Thinking

Using critical thinking in your own life is vital, but passing it along to the next generation is just as important. Be sure to focus on analyzing and evaluating, two multifaceted sets of skills that take lots and lots of practice. Start with these 10 Tips for Teaching Kids To Be Awesome Critical Thinkers . Then try these critical thinking activities and games. Finally, try to incorporate some of these 100+ Critical Thinking Questions for Students into your lessons. They’ll help your students develop the skills they need to navigate a world full of conflicting facts and provocative opinions.

One of These Things Is Not Like the Other

This classic Sesame Street activity is terrific for introducing the ideas of classifying, sorting, and finding relationships. All you need are several different objects (or pictures of objects). Lay them out in front of students, and ask them to decide which one doesn’t belong to the group. Let them be creative: The answer they come up with might not be the one you envisioned, and that’s OK!

The Answer Is …

Post an “answer” and ask kids to come up with the question. For instance, if you’re reading the book Charlotte’s Web , the answer might be “Templeton.” Students could say, “Who helped save Wilbur even though he didn’t really like him?” or “What’s the name of the rat that lived in the barn?” Backwards thinking encourages creativity and requires a good understanding of the subject matter.

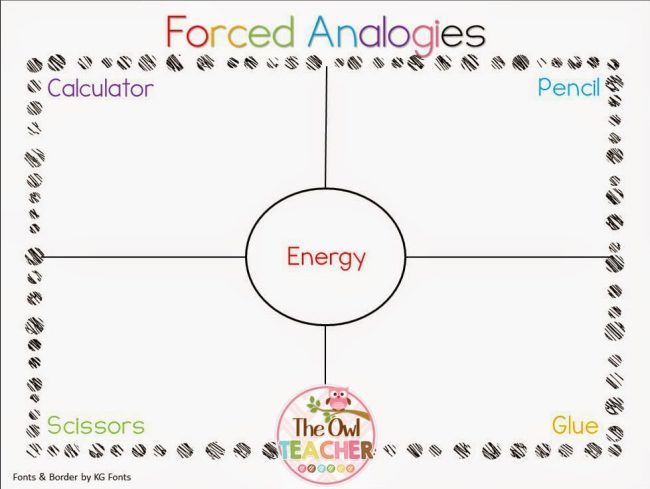

Forced Analogies

Practice making connections and seeing relationships with this fun game. Kids write four random words in the corners of a Frayer Model and one more in the middle. The challenge? To link the center word to one of the others by making an analogy. The more far out the analogies, the better!

Learn more: Forced Analogies at The Owl Teacher

Primary Sources

Tired of hearing “I found it on Wikipedia!” when you ask kids where they got their answer? It’s time to take a closer look at primary sources. Show students how to follow a fact back to its original source, whether online or in print. We’ve got 10 terrific American history–based primary source activities to try here.

Science Experiments

Hands-on science experiments and STEM challenges are a surefire way to engage students, and they involve all sorts of critical thinking skills. We’ve got hundreds of experiment ideas for all ages on our STEM pages , starting with 50 Stem Activities To Help Kids Think Outside the Box .

Not the Answer

Multiple-choice questions can be a great way to work on critical thinking. Turn the questions into discussions, asking kids to eliminate wrong answers one by one. This gives them practice analyzing and evaluating, allowing them to make considered choices.

Learn more: Teaching in the Fast Lane

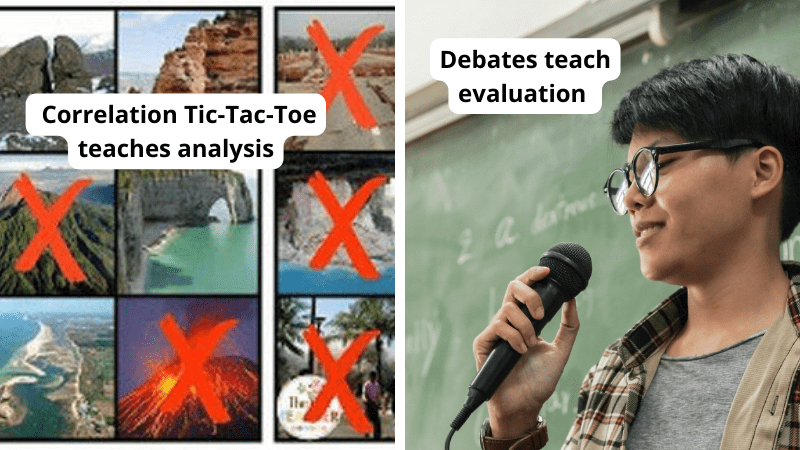

Correlation Tic-Tac-Toe

Here’s a fun way to work on correlation, which is a part of analysis. Show kids a 3 x 3 grid with nine pictures, and ask them to find a way to link three in a row together to get tic-tac-toe. For instance, in the pictures above, you might link together the cracked ground, the landslide, and the tsunami as things that might happen after an earthquake. Take things a step further and discuss the fact that there are other ways those things might have happened (a landslide can be caused by heavy rain, for instance), so correlation doesn’t necessarily prove causation.

Learn more: Critical Thinking Tic-Tac-Toe at The Owl Teacher

Inventions That Changed the World

Explore the chain of cause and effect with this fun thought exercise. Start it off by asking one student to name an invention they believe changed the world. Each student then follows by explaining an effect that invention had on the world and their own lives. Challenge each student to come up with something different.

Learn more: Teaching With a Mountain View

Critical Thinking Games

There are so many board games that help kids learn to question, analyze, examine, make judgments, and more. In fact, pretty much any game that doesn’t leave things entirely up to chance (Sorry, Candy Land) requires players to use critical thinking skills. See one teacher’s favorites at the link below.

Learn more: Miss DeCarbo

This is one of those classic critical thinking activities that really prepares kids for the real world. Assign a topic (or let them choose one). Then give kids time to do some research to find good sources that support their point of view. Finally, let the debate begin! Check out 100 Middle School Debate Topics , 100 High School Debate Topics , and 60 Funny Debate Topics for Kids of All Ages .

How do you teach critical thinking skills in your classroom? Come share your ideas and ask for advice in the WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook .

Plus, check out 38 simple ways to integrate social-emotional learning throughout the day ..

You Might Also Like

10 Tips for Teaching Kids To Be Awesome Critical Thinkers

Help students dig deeper! Continue Reading

Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

- Skip to content

- Skip to search

- Staff portal (Inside the department)

- Student portal

- Key links for students

Other users

- Forgot password

Notifications

{{item.title}}, my essentials, ask for help, contact edconnect, directory a to z, how to guides, education for a changing world, how to teach critical thinking.

Daniel Willingham is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Virginia. His paper explores the ongoing debate over how critical thinking skills are developed and taught. He also outlines a plan for teaching specific critical thinking skills.

Willingham argues that while there is plenty of evidence to support explicit instruction of critical thinking skills, the evidence for how well critical thinking skills transfer from one problem to another is mixed.

Published: 2019.

Download the paper

How to teach critical thinking (PDF 373KB)

Other resources

- Peter Ellerton, Thinking critically for an AI world (Edspresso episode 3)

- Sandra Lynch, Teaching critical thinking through philosoph y (Edspresso episode 4)

- Peter Ellerton, On critical thinking and collaborative inquiry

- Learning First, Teaching critical thinking: Implications for stages 4 and 5 Science and History teaching

- Teaching and learning

Business Unit:

- Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Teaching Expertise

- Classroom Ideas

- Teacher’s Life

- Deals & Shopping

- Privacy Policy

Developing Critical Thinking: 80 Contemplative Journal Prompts For Middle School Students

August 8, 2023 // by Lauren Du Plessis

In a world focused on the daily hustle and bustle, your middle schoolers need opportunities to slow down and think critically about the deeper things in life. When learners engage in high-order thinking, their focus narrows as they analyze information from a variety of personal background experiences and sources. Not only do our journal prompts aim to enhance your students’ complex reasoning abilities, but they also strive to provide character growth opportunities as well! Use our collection as a critical-thinking springboard for your middle schoolers!

1. If you could change one rule at school, what would it be and why?

2. What is one thing you wish adults understood about being a middle school student today?

3. If you could spend a day with any historical figure, who would it be and why?

4. Write about a time when you felt truly proud of yourself. What happened, and why did it make you feel this way?

5. If you could invent a new subject that would be taught in schools, what would it be? Explain why it’s important.

6. What are the three most important qualities a leader should have? Provide examples of leaders who embody these qualities.

7. Is there a difference between making a mistake and failing? Explain your thoughts.

8. If you could solve one world problem, what would it be and why?

9. What would you do if you were president for a day?

10. How does the music we listen to influence us?

11. How can you show more empathy towards people who are different from you?

12. What is your definition of success?

13. What does it mean to be a good friend?

14. How does social media influence our perception of reality?

15. How would you feel if money didn’t exist? How would the world change?

16. What does courage look like to you?

17. Describe a difficult decision you had to make. How did you decide what to do?

18. Is it more important to be a good listener or a good speaker?

19. If you could give any piece of advice to your younger self, what would it be?

20. How can one person make a difference in the world?

21. What is something you believe in that others might not agree with?

22. What does it mean to be a global citizen?

23. If you could time travel, where would you go and why?

24. How does nature impact our well-being?

25. What is the purpose of art in society?

26. How does our environment shape our behavior?

27. Do you believe in fate or free will? Explain your stance.

28. What would you do if you were not afraid of failure?

29. What do you value most in your friendships and why?

30. What does honesty mean to you? Is it always better to tell the truth?

31. Can you judge a book by its cover? When is it fair to judge someone or something?

32. How does technology affect our relationships with others?

33. What does equality mean to you?

34. How would life be different if humans could communicate telepathically?

35. How would the world change if animals could talk?

36. What is the purpose of school and education?

37. Is there such a thing as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ emotions?

38. What would a perfect society look like?

39. How important is the first impression? Do they accurately represent individuals?

40. What is the role of dreams in our lives?

41. How important are our choices in shaping our lives?

42. Is it better to work in a team or alone?

43. What are the most important qualities of a teacher?

44. How does learning about the past impact our future?

45. What makes a book or movie good?

46. Can someone be happy without money?

47. How does learning a new language change a person?

48. Is it more important to enjoy your job or to earn a high salary?

49. What does it mean to be a hero? Who are some heroes in real life?

50. How does the place where we grow up shape our identity?

51. Should animals have rights? Why or why not?

52. How does advertising influence what people buy?

53. What is the biggest challenge young people face today?

54. Is there such a thing as true altruism?

55. What does ‘home’ mean to you?

56. What role does fear play in your life?

57. How does fiction reveal the truth about real life?

58. Why do we dream? What purpose does it serve?

59. What is the value of solitude?

60. How does physical activity affect our mental health?

61. How do your surroundings impact your creativity?

62. Can a person change who they are, or are we predestined to stay the same?

63. What is the role of ‘play’ in learning?

64. How does one’s appearance affect their personality or how they’re treated?

65. What does it mean to be rich? Is wealth more than just money?

66. How does our culture shape our identity?

67. Why is it important to learn about other cultures?

68. How does the news shape our understanding of the world?

69. What role do hobbies play in people’s lives?

70. What is the value of silence in a world full of noise?

71. How does prejudice arise? How can we combat it?

72. How does travel broaden our perspective?

73. What is the impact of climate change on our future?

74. How do different generations view the world differently?

75. Is knowledge always a good thing, or can it be dangerous?

76. What makes people want to follow a leader?

77. How do the books we read influence our lives?

78. How does society define beauty?

79. What is the value of expressing gratitude?

80. How important is the quest for truth? Is it always objective?

How To Teach Your Kids Critical-Thinking Skills

Your kids are learning math and reading skills, but are they learning critical-thinking skills? In a recent study commissioned by MindEdge Learning, only 36 percent of millennials surveyed said they were “well-trained” in these skills. As many as 37 percent of the 1,000 young people surveyed admitted they were sharing information on their social media networks that was likely inaccurate news. And more than half of them used social media for their main source of news.

Frank Connolly, senior editor at MindEdge, notes, “By 2020, the World Economic Forum anticipates critical thinking will be the second most important skill to exhibit, second only to complex problem-solving.”

Kids need to learn critical-thinking skills to become successful adults. But how can parents and educators ensure kids learn to be critical thinkers? Here are four simple ways to communicate better with your child, while teaching them how to think for themselves, when it comes to dissecting and sharing news and information.

1. Teach Your Child to Question What They Read or Hear

Brainstorming is always a great skill that helps teach creativity. And parents can use many types of news to start a brainstorming session—a new bit of juicy gossip, something that sounds scary, or something exciting are all an open door for exploration and discussion. Teach your children to ask questions and even find out who is spreading such information. Is it a reliable news source? A tabloid? A fellow classmate who has only heard it from someone else? The right questions can lead to discussions about the state of the world or other relevant topics.

2. Make Thinking a Family Affair

In today’s world, where so many kids are glued to their digital devices , how can you start discussions that foster critical thinking? Use the times that you are together as a family—around the dinner table, during long car rides , or while on a weekend picnic—to bring up topics that encourage questions and problem-solving techniques. “What do you think of such-and-such?” Or, “What is your opinion on ____?” Leave the floor open for discussion, and always be open-minded yourself during these conversations.

3. Go Deeper

Encourage your kids to read books on similar topics, watch movies related to the topic , or visit the local library together to study and keep the conversation going. Don’t be afraid to let them explore a topic of interest. If they are showing some critical-thinking skills in the realm of politics, for example, you can study world history or watch relevant documentaries on the subject.

4. Teach Them to Be Socially Responsible

Talk about their social network “news” and why it may or may not be a good idea to share certain stories. During your discussions, bring up the point about their social networks being a public platform, which can either be used for good or have negative repercussions and even be a place for “ fake news .” Teach them to pause and check in with themselves before automatically sharing something on the internet.

Remember, critical thinking is more than just being rational. It’s about the ability to think independently. When your children are able to draw their own conclusions and make up their own minds on matters, without being “swayed” by peers or even other adults, then they will be true critical thinkers!

Related Articles

How am I Going to Pay for College?

April 16 2024

5 Major Benefits of Summer School

April 12 2024

Inspiring an Appreciation for Poetry in Kids

April 9 2024

A Parent’s Guide to Tough Conversations

April 2 2024

The Importance of Reading to Children and Its Enhancements to Their Development

March 26 2024

5 Steps to Master College-Level Reading

March 19 2024

10 Timeless Stories to Inspire Your Reader: Elementary, Middle, and High Schoolers

March 15 2024

From Books to Tech: Why Libraries Are Still Important in the Digital Age

March 13 2024

The Evolution of Learning: How Education is Transforming for Future Generations

March 11 2024

The Ultimate Guide to Reading Month: 4 Top Reading Activities for Kids

March 1 2024

Make Learning Fun: The 10 Best Educational YouTube Channels for Kids

February 27 2024

The Value of Soft Skills for Students in the Age of AI

February 20 2024

Why Arts Education is Important in School

February 14 2024

30 Questions to Ask at Your Next Parent-Teacher Conference

February 6 2024

Smart Classrooms, Smart Kids: How AI is Changing Education

January 31 2024

Four Life Skills to Teach Teenagers for Strong Resumes

January 25 2024

Exploring the Social Side of Online School: Fun Activities and Social Opportunities Await

January 9 2024

Six Ways Online Schools Can Support Military Families

Is Your Child Ready for Advanced Learning? Discover Your Options.

January 8 2024

Online School Reviews: What People Are Saying About Online School

January 5 2024

Your Ultimate Guide to Holiday Fun and Activities

December 18 2023

Free Printable Holiday Coloring Pages to Inspire Your Child’s Inner Artist

December 12 2023

Five Reasons to Switch Schools Midyear

December 5 2023

A Parent’s Guide to Switching Schools Midyear

November 29 2023

Building Strong Study Habits: Back-to-School Edition

November 17 2023

Turn Up the Music: The Benefits of Music in Classrooms

November 7 2023

A Parent’s Guide to Robotics for Kids

November 6 2023

Six Ways Online Learning Transforms the Academic Journey

October 31 2023

How to Get Ahead of Cyberbullying

October 30 2023

Bullying’s Effect on Students and How to Help

October 25 2023

Can You Spot the Warning Signs of Bullying?

October 16 2023

Could the Online Classroom Be the Solution to Bullying?

October 11 2023

Bullying Prevention Starts With Parents

October 9 2023

How to Teach Kids Manners

April 7 2016

Is Year-Round School Better for Kids?

July 12 2016

Video: What Kids Say Makes Their School Awesome!

June 10 2015

Join our community

Sign up to participate in America’s premier community focused on helping students reach their full potential.

Welcome! Join Learning Liftoff to participate in America’s premier community focused on helping students reach their full potential.

Join Pilot Waitlist

Home » Blog » General » The Importance of Teaching Critical Thinking in Middle School: A Comprehensive Guide

The Importance of Teaching Critical Thinking in Middle School: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction.

Why is critical thinking important in today’s world? In a rapidly changing society, it is crucial for students to develop the skills necessary to think critically and solve complex problems. The Discovery stage of middle school is a pivotal time for students to begin honing their critical thinking abilities. This comprehensive guide will explore the importance of teaching critical thinking in middle school and provide practical strategies for educators to implement in their classrooms.

Understanding Critical Thinking

Critical thinking can be defined as the ability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information in order to make informed decisions and solve problems. It involves a combination of skills such as logical reasoning, creative thinking, and effective communication. Developing critical thinking skills in middle school students is essential as it lays the foundation for their academic success and prepares them for the challenges they will face in the future.