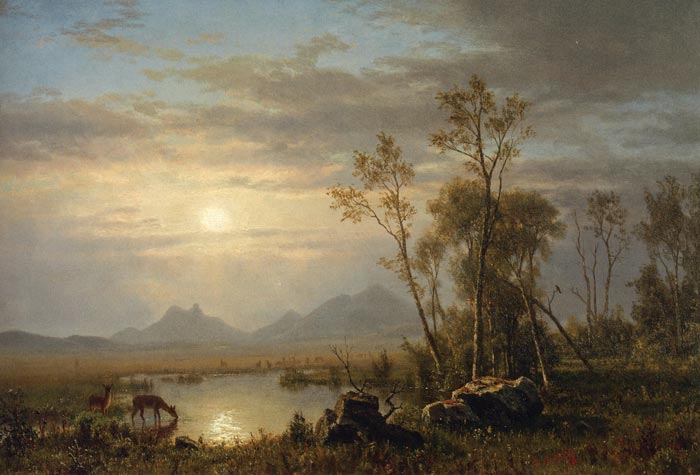

The Iranian king Bahram Gur fights the horned wolf; illustrated folio from a manuscript of the Great Il-Khanid Shahnama (Book of Kings), unidentified artist, c 1330-40, Tabriz. Courtesy Harvard Art Museums

The Asian world order

Before modern europe existed there was a grand, interconnected political world, rich in scientific and artistic exchange.

by Ayşe Zarakol + BIO

The process that gave rise to Eurocentrism in social sciences and history is somewhat comparable to the follies of youth. Little children have difficulty believing that their parents existed before their birth. Teenagers often think that they are the first ones to have the experiences they are having as they make their way into adulthood. Young people usually think of previous generations as stodgy and old-fashioned, and of themselves as uniquely special and innovative. And they imagine they will be forever so, as if time will stop moving after them.

Part of growing up, however, is gradually breaking out of such narcissistic naiveté. As we get older, we start realising that others before us had many experiences that resemble ours, even if they enjoyed different fashions and lacked certain technologies. Then the cycle repeats with the next generation. It is perhaps not particularly surprising that our social sciences, which came of age in the 19th and early 20th centuries – ie, ‘the youth’ of European/Western hegemony – also had a similar naiveté about world history. Europe/the West mattered the most at that moment, so it must have always been so. And perhaps it is a sign we are now nearing the twilight years of this hegemony that critiques (and self-critiques) of Eurocentrism have become so commonplace in most social sciences as to be banal.

But while it has been easy to level critiques of Eurocentrism against the social sciences – a low-hanging fruit if there ever was one – it has proven much harder to find solutions to it. There is always the danger that, in attempts to get away from Eurocentrism, we replace one kind of self-regarding history with another. It is also naive to think that only Europeans produce/have produced self-centred and whiggish narratives of history. A Sinocentric or Russocentric world history is no solution – it would just repeat the cycle.

So how do we do it?

I n international relations, too, until recently, students were taught that there was no international order (and thus no international relations) until the 17th century, until Europeans created a regional order via the Westphalian Peace in 1648 and then expanded that around the world. The rest of the world was assumed to be disconnected, stuck in their regional silos, uninterested in the wider world, until European actors connected them first to Europe, and then to each other.

In such textbook accounts, ‘international order’ is usually defined as referring to the system of rules, norms and institutions that govern relations among states and other international actors. The principles and norms that underpin the modern international order are considered to include sovereignty, territorial integrity, human rights, non-interference in internal affairs, peaceful settlement of disputes, multilateralism and the rule of law. Westphalia is considered the origin point because of its supposed introduction of the non-interference principle.

There is plenty of international relations material in history outside of Europe and before modernity

The ‘Westphalian myth’ in international relations has come under considerable criticism in recent years, but given the way international order is traditionally defined, it is not particularly surprising that experts maintain that there were no comparable international orders before our modern one (though it is also questionable how long such an order has existed even in modernity). The problem stems from the fact that our terminology grabs some features of world politics that have existed only in modernity (eg, the concept of human rights, international organisations, or even territorial integrity) and builds them into the definition with other features that have arguably been around much longer (eg, sovereignty or mechanisms for peaceful settlement of disputes). Even the term international order is misleading because it presumes nation-states, which are a relatively late feature of human politics.

But if we relax the assumption that only orders created by nation-states are worth studying, then there is plenty of international relations material in history outside of Europe and before modernity that we can investigate. This is why I prefer to speak of ‘world orders’ instead of ‘international orders’, defined as the (man-made) rules, understandings and institutions that govern (and pattern) relations between the primary actors of world politics (but those actors can change over time: nation-states, aristocratic houses, city-states, etc). A ‘world order’ also has a universalising ambition at its core and is expansive in its vision.

When we think of it that way, it is not hard to see that there certainly were world orders before Westphalia and the 17th century: ‘the East’ too has been home to world orders (and world orderers). By looking at Asian world orders that came before European hegemony, we can learn a great deal.

T here was a ‘Chinggisid’ world order as created by Genghis (Chinggis) Khan and members of his house (13th-14th centuries), followed by the ‘post-Chinggisid’ world order of the Timurids and the early Ming (14th-15th centuries) and, finally, a globalising world with its core position occupied by three post-Timurid (and, therefore, Chinggisid) empires (15th-17th centuries): the Ottomans, the Safavids and the Mughals (along with the Habsburgs). These orders were also linked to each other just as our contemporary order is linked to the 19th-century international order – there was a continuity in their shared norms. In each of these periods, the world was dominated and ordered by great houses who justified their sovereignty along Chinggisid lines.

‘Chinggisid’ sovereignty means the following: in the 13th century, Genghis Khan reintroduced to Eurasia a type of all-powerful sacred kingship we associate more with antiquity but one that had disappeared from much of this space after the advent of monotheistic religions and transcendental belief systems that checked the earthly power of political rulers by pointing to an all-powerful moral code that applied to all humans. As such religions gained more power from late antiquity onwards, the power of kingship was greatly diminished throughout Eurasia. Kings could no longer make laws as they had to share their authority with the written religious canon and its interpreters. Genghis Khan and the Mongols broke this pattern of constrained kingship (others had attempted to do so before as well, but never so successfully). The adjective Chinggisid is more apt than Mongol to describe the worlds thus created because these orders were orders of great houses (dynasties) rather than nations.

Such absolute rulers always chased world empire and ended up ordering the world

Genghis Khan claimed law-making power above and beyond that of religious (and other) actors. He made himself the lawgiver but did not claim to be a prophet. Nor did he claim to be merely verbalising divine laws. He made the law and still expected people to obey, even if they already had their own religious rules and laws. Such centralisation of supreme authority in one person requires robust legitimation. The claim to have such awesome authority could be justified only by a mandate for universal sovereignty over the world, as corroborated and manifested by world conquest and world empire. And because Genghis Khan succeeded in creating a nearly universal empire, he also diffused this particular understanding of sovereignty across Eurasia.

The story of Genghis Khan as a world-conqueror and lawgiver lived on for centuries (as inflected by the example of Timur/Tamerlane later), legitimising a certain type of political rule throughout this space and strengthening the hands of rulers desiring to claim centralising political authority, even in places where religious authority (eg, the Islamic jurists) posed a challenge to absolute kingship. And such rulers always chased world empire and ended up ordering the world (often violently and brutally but also at times productively) in their competition for this mantle. The Asian world orders between the 13th and 17th centuries constitute an important history of powerful and influential world orders outside of European hegemony. And insofar as political centralisation is an essential component of modern sovereignty, it may be argued that similar Asian understandings and practices of sovereignty both predate and may have even influenced the European trajectory.

F irst was the original ‘world order’ created by Genghis Khan (and his house) in the 13th century. If there is indeed an ‘East’ that is distinct from the ‘West’, one of the points of separation can be placed here. After all, Genghis Khan’s empire was primarily an ‘Asian’ one, spanning the distance from the Pacific Ocean in the East to the Mediterranean in the West. Actors of (and within) this order interacted with the Indian subcontinent to their South and the European/Mediterranean regional orders to their West (and influenced developments therein and vice versa) but, for the most part, polities in those regions were not incorporated into this order and retained their own logics of power, legitimation, warfare, etc.

In this ‘Asian’ order, people living in the geographies that we now call ‘Russia’, ‘China’, ‘Iran’ and ‘Central Asia’ – basically, most of continental Asia – shared the same sovereign for the first time and then were ruled/dominated by dynasties (the Golden Horde/Jochid, the Yuan, the Ilkhanate and the Chagatai) that directly inherited Chinggisid norms, ie, ambitions of universal sovereignty and dynastic legitimacy based on world conquest, high degrees of political centralisation around the supreme authority of the Great Khan. They were also significantly connected to each other through overland and naval routes that spanned the entire continent, as well as the Indian Ocean.

The existence of such trade routes – the ‘silk roads’ – predated the Chinggisid Empire. After their conquests, however, the Mongols strengthened these connections through the postal ( yām ) system and homogenised the points of contact throughout by their presence in the major spheres of influence within the continent. Thus, late 13th-century Eurasia was as connected as it had ever been (and even more so than some subsequent periods). Famous explorers of the 14th century – eg, Marco Polo or Ibn Battuta – could thus make their way from Europe or North Africa to China with relative ease, causing hardly any more commotion than some curiosity among hosts (who must have been accustomed to travellers along these routes) and facing not much more than some demand for updated information about cities and rulers encountered along the way.

The spread of the Black Death from the East in the mid-14th century spelled the end of that status quo

Yet others travelled in the opposite direction from China to West Asia, and started new lives in Europe or what is now called Iran, under new rulers. A mostly forgotten aspect of this order is the facilitation of epistemic exchange of all sorts, most notably between ‘Iran’ and ‘China’: in the 13th and 14th centuries, bureaucrats, scientists, artists, craftsmen and engineers could be born on one side of Asia and finish their careers on the opposite side, with profound implications for artistic, cultural and scientific standards of both societies. The best (but not only) example of this cultural exchange is the fundamental transformation of Islamic art from the 13th century onwards under Chinese influences, producing among other things the blue-and-white ceramics that are now so closely associated with the Middle East. This process is sometimes called the ‘Chinggisid exchange’ by historians of the Mongol Empire, similar to the Columbian exchange in terms of its world-historical impact.

After holding most of Asia under the same sovereign for more than half a century – which would be no small feat even today, let alone in the 13th century – the world empire/khanate ruled by the Great House of Genghis Khan fragmented into four smaller khanates, each based in territories originally given to different branches of his descendants to govern. Once autonomous, rival khanates went through a brief period of intense fighting to reclaim the mantle of universal sovereignty, but none managed to dominate the others. Eventually they settled into a ‘balance-of-power’ type equilibrium in the early 14th century. This period was particularly good for overland trade across Eurasia, extending the period known as Pax Mongolica.

The spread of the Black Death from the East (or Central Asia) to the West in the mid-14th century spelled the end of that status quo, however, as all but one of the khanates fell apart. The Golden Horde continued to rule the north-western steppes of Asia (present-day Russia), but the Chagatai Khanate (Central Asia) and the Ilkhanate (the Middle East) disintegrated, eventually giving way by the end of the 14th century to the Timurid Empire originating from Transoxiana, and the Yuan were overthrown by the Ming dynasty in 1366. Thus ended the first would-be world order organised by Chinggisid sovereignty.

T he next world order that succeeded Genghis Khan’s and its successor khanates brought more diversity, and a competition between two great powers. From the last third of the 14th century to the middle of the 15th century, the Great Houses of Timur (Tamerlane) and Zhu Yuanzhang (Hongwu), ie, the Ming dynasty, competed to succeed the Great House of Genghis Khan from the two sides of Asia.

As long as the Ming and the Timurids competed, they ordered the world in post-Chinggisid ways. They were post-Chinggisid because neither the Timurids nor the Ming were directly linked to the house of Genghis Khan but were nevertheless very much influenced by the order of their predecessors. They had different views about the Chinggisids but, just as in our modern world, one cannot escape an institutional legacy only by rejecting its creators.

The post-Chinggisid influence is easy to demonstrate in the case of the Timurids because Timur, as a Turco-Mongol ruler himself, did his best to play up any connections. He married a Chinggisid princess. He ruled through a puppet khan from a Chinggisid lineage, never taking the title for himself (he was called amir himself). Still, in all ways that mattered, he deliberately fashioned himself after the model of Genghis Khan and died on the way to attempting to conquer China, just like Genghis. He centralised authority in the Chinggisid mould, seeking world conquest and recognition. He even found a novel way to reconcile the tension between Chinggisid sovereignty and Islam via the title of sahibkıran (Lord of Conjunction), as astronomy/astrology was a bridge between the Chinggisid and Islamic ways of seeing the world.

By contrast, the Ming, who were Han, ostensibly rejected any Chinggisid influences after they overthrew the Yuan dynasty. Still, the preoccupation of the early Ming emperors Hongwu and Yongle with world recognition also demonstrably derived from Chinggisid ideals and thus can be considered post-Chinggisid. In 1403, the Ming emperor ordered the construction of 137 ocean-going ships; later, he ordered the construction of 1,180 more. He put Zheng He in charge of these expeditions which went as far as the Indian Ocean. Modern-day China’s power-projection ambitions have reintroduced these so-called ‘Ming treasure voyages’ to the popular imagination.

Overland trade brought Ming wares to West Asia (which then sold them to the Middle East and Europe)

However, what is often missed in contemporary discussion is the larger context and historical antecedents of these voyages. The maritime envoys were only part of the story – Yongle also sent overland envoys, including to Herat, the Timurid capital. Even experts in the growing field of China’s historical international relations often overlook the degree to which the goal of external recognition drove the early Ming and how that ideal derived from their Yuan (Chinggisid) predecessors and was shared by Central Asian rivals. Much of international relations scholarship, with its bias for a 20th-century world, still imagines inner Asia to be peripheral to world politics in history. But in the 15th century, it was the centre of a world ordered by the Timurids on the one side and the Ming on the other.

Timur failed to conquer China and eventually he had to settle into something like mutual recognition with the early Ming dynasty. A continent of lesser houses connected the great houses of Timur and Yuan or Ming. Some had their own Chinggisid-style world-empire aspirations, and others, the Joseon dynasty in Korea, for example, operated at a minimum with an understanding of the same Chinggisid legacy. Material connections were also part of the legacy of the Chinggisid world order, across Asia. Overland trade brought Ming wares to West Asia (which then sold them to the Middle East and Europe) and silver to the East. Both the Timurid and the Ming also sponsored great works of art and craftsmanship in this period.

Some may object that direct contact between these two Great Houses on the two sides of Asia was infrequent and therefore not enough to constitute a world order. But there is a resemblance between the order of the Timurids and the Ming in the late 14th/early 15th century, on the one hand, and that created by the rivalry of the US and the USSR after the Second World War, on the other. In both orders, one pole downplayed or even ostensibly rejected the legacy of the former world order whereas the other embraced it. But both were products of a shared historical experience and in fact had a lot in common in how they saw the world. Even when the Timur and Ming dynasties did not directly interact, they competed with each other symbolically and in so doing reinforced the normative fabric of the 14th- to 15th-century world order in Asia.

Also like the Cold War order, the Timurid-Ming rivalry was not around for very long. In the middle of the 15th century, a bullion famine, a shortage of money, hit Eurasia and precipitated a period of structural crisis by contracting overland trade. The Timurid dynasty of West Asia was particularly hard hit. The Timurids lost control over their territories. In the second half of the 15th century, Chinggisid influences on the Ming also faded, and neo-Confucianism took over. The neo-Confucian movement empowered bureaucrats and officials and constrained the power and authority of the Ming rulers, checking centralisation. The Ming realm turned more inward-looking, or isolationist. The ‘bipolar’ world order of the Timurid and the Ming Great Houses fragmented before it had the opportunity to congeal into something more institutionalised.

T he next fertile ground for world-ordering projects based on Chinggisid sovereignty norms came from the southwestern corner of Asia. In the 15th century, the region had been dominated by the Timurid Empire/khanate, and Chinggisid sovereignty norms had merged with existing Persian notions of kingship, millennial expectations, astrology and other occult sciences, as well as folk practices of Islam within this region. This fusion of Chinggisid, Persian and Islamic political cultures gave rise to at least three great houses with some of the more ambitious universal sovereignty claims in history: the Ottomans, the Safavids and the Mughals.

By the 16th century, these three Great Houses together claimed sovereignty over more than a third of the human population of the world. They also controlled the core of the world economy. Though often called Islamicate empires, the Ottomans, the Safavids and the Mughals shared more than Islam (and at times contravened prior Islamic practice). As with the previous examples discussed, they too subscribed to the same sovereignty model (at least in the 16th century): a type of sacred kingship, a fused form of vertical political centralisation achieved by the unification of political and religious authority in the same person, made possible by the Chinggisid-Timurid legacies they inherited. Following Timur, the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal claim to greatness was based on the claim of the rulers from these houses to be sahibkıran , universal sovereigns marked by signs from the heavens, living in the end of days, delivering on millennial expectations. Astrology and other occult sciences supported the universal sovereignty projects of these would-be world empires. Thus, in the 16th century, it was primarily the post-Chinggisid and post-Timurid ‘millennial sovereigns’ in Southwest Asia who ordered an increasingly globalising world, not yet the Europeans.

Scholars of international relations tend to see the 16th century as holding the seeds of a world order based on European hegemony. It is undeniable that the 16th century was a period of growth and expansion for Europe (especially for Habsburg Spain), but Europe was growing from a position of greater deprivation than Asia. If we do not read the ending of the story back into the historical narrative, in the 16th century it was still not at all obvious that European actors would come to dominate the world. Almost all histories of this period within international relations treat the Habsburgs’ eastern relations as relatively insignificant, but that is also a projection of the standards of a later time to the 16th century. Especially in the first two-thirds of the 16th century, the main rival of the Habsburgs were the Ottomans, who were themselves engaged in a simultaneous rivalry with the Safavids, from whose orbit the Mughals were trying to break. Smaller European houses had aspirations, to be sure, but their time in the sun had not really come yet, and they initially had to rely on Eastern alliances as well as trade with Asia to get on an upward trajectory.

No region is ‘destined’ to order the world; outcomes are not just path-dependent but also contingent and variable

All of this is to say that we must scrap the traditional narrative lurking in the background of the Westphalian origin myth of international relations, ie, the narrative of an ascendant European order in the 16th century with non-European hangers-on looking in, such as the Ottomans on its periphery (or the Russians). The real picture is just the opposite: the 16th-century world had a core of post-Timurid empires in (south-)West Asia animated by an intense competition focused on universal sovereignty, and European actors such as the Habsburgs were trying to challenge the dominance of that core (while other European players linked into it through trade networks and other alliances). The Ming still had to contend with Mongol warriors on their frontiers, motivated by these same notions; in the northwest, Muscovy had been remade in the image of the Golden Horde. The various peoples of Inner Asia also mostly operated with Chinggisid sovereignty norms still, even if the expectations around centralisation and world empire remained only aspirational. The 16th-century world was thus still very much ordered from the East. It is important to realise this because it disrupts our teleological thinking about the inevitability of European hegemony. No region is ‘destined’ to order the world; outcomes are not just path-dependent but also contingent and variable.

The expansion of this Eastern world order was stopped in its tracks not by destiny or European greatness, but rather by the unpredictable developments of the late 16th to mid-17th century, a politically tumultuous period throughout Eurasia. Some historians label this period ‘the 17th-century general crisis’, a period of prolonged rebellions, civil wars and demographic decline throughout the northern hemisphere. Historians have given different explanations as to what ushered in this upheaval: some suggesting financial causes (eg, the global repercussions of the Spanish ‘price revolution’ – inflation – due to the influx of surplus silver from the New World), whereas others point to demographic contraction. Others now link the chaos of this period to the Little Ice Age : the peak moment of a cooler period in the Northern Hemisphere that extended from the 13th to the 19th century. Prolonged periods of cooler temperatures and storms may indeed have been responsible for all the other factors we associate with the period: crop failures, disruption of overland trade, demographic collapse in hinterlands, rebellions and civil wars.

Whatever the cause, the continued disorder of the 17th century caused the irreversible fragmentation of the 16th-century world order. This was the turning point for the East because, while aspects of the Chinggisid sovereignty norms survived the 17th century and motivated particular rulers (eg, Nader Shah of Persia), no new ‘world orders’ organised around those norms were successfully created after the 17th century . A global perception set in the 19th century that Asia had been irreversibly declining for centuries, even though most Asian and Eurasian states had materially recovered from the crises of the 17th century, and had, in some cases, even gone on to territorially expand in the 18th century (eg, Russia, China). These two developments – the loss of ‘world orders’ originating in the East, on the one hand, and the perception of decline despite continued durability of Eastern states, on the other – are linked.

O ne of the greatest benefits of moving beyond Eurocentrism and thus having more examples outside of European history to think with about our present challenges is that such examples expand our imagination as to what is possible. Until recently, international relations scholars had imagined that international orders do not change very much in terms of their building blocks – it was assumed that only the number or the identity of great powers changed. Until recently, international relations also did not allow for the possibility that the liberal international order may unravel or be replaced by an entirely alien order (in a similar vein to the ‘End of History’ thesis of the 1990s). Such conclusions are somewhat inevitable if one looks at the world only post- 17th century. But world history teaches us different lessons.

When we study the trajectory of Eastern world orders, we see that structural crises punctuate the end of each order (even if the exact chain of causality is hard to ascertain). The fragmentation of each Eastern world order seems to at least correlate with a ‘general crisis’ that affected large areas of the Northern Hemisphere. The original Chinggisid world order fragmented at a time when the plague was spreading across Asia (and then Europe) and came to an end during a period that some historians label ‘the 14th-century crisis’; the post-Chinggisid world order fragmented during a period some historians call ‘the 15th-century crisis’, the effects of which seem to have been felt especially in west Asia and Europe.

The 17th-century crisis period of fragmentation lasted the longest and spelled the end of Eastern world orders

Longue durée hindsight allows us to see that political turmoil during these crises (and during the ensuing fragmentation of the existing order) was not really caused by specific great house rivalries or ‘power transition’ (ie, the things international relations most worries about as being corrosive to order), but rather structural dynamics such as climate change, epidemics, demographic decline, monetary problems etc: ie, the things international relations has not worried about at all until recently. Contrary to the assumptions of the international relations literature about great powers, this history suggests that rivalries by great houses that shared the same understanding of ‘greatness’ in fact strengthened and reinforced the existing world order (even when those rivalries turned violent).

A similar observation can be made about great power competition in the 19th century or the Cold War. Rivalry is constitutive of order (almost as much as trade and cooperation); order decline almost always originates from elsewhere. A final observation is that world orders were not immediately replaced after fragmentation; there were periods without ‘world order’-ers around (or, even if they were around, their presence was not felt by other actors). The 17th-century crisis period of fragmentation lasted the longest and perhaps for that reason spelled the end of Eastern world orders.

Unfortunately, there are enough reasons to suspect that we may be in for a similar period of turbulence and disorder in the 21st century. All the factors that were at play in the 17th century – climate change, demographic unpredictability, economic volatility, internal chaos – that took the attention of world orderers from maintaining world order are also present today.

This Essay is based on the chapter ‘What Is the East?’ of the author’s book Before the West (2022) published by Cambridge University Press.

Human rights and justice

My elusive pain

The lives of North Africans in France are shaped by a harrowing struggle to belong, marked by postcolonial trauma

Farah Abdessamad

Conscientious unbelievers

How, a century ago, radical freethinkers quietly and persistently subverted Scotland’s Christian establishment

Felicity Loughlin

History of technology

Why America fell for guns

The US today has extraordinary levels of gun ownership. But to see this as a venerable tradition is to misread history

The scourge of lookism

It is time to take seriously the painful consequences of appearance discrimination in the workplace

Andrew Mason

Economic history

The southern gap

In the American South, an oligarchy of planters enriched itself through slavery. Pervasive underdevelopment is their legacy

Keri Leigh Merritt

Thinkers and theories

Our tools shape our selves

For Bernard Stiegler, a visionary philosopher of our digital age, technics is the defining feature of human experience

Bryan Norton

- Help & FAQ

Why the liberal world order will survive

- Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

Research output : Contribution to journal › Review article › peer-review

The crisis of the American-led international order would seem to open up new opportunities for rising states-led by China, India, and other non-Western developing countries - To reshape the global order. As their capacities and influence grow, will these states rise up and integrate into the existing order or will they seek to overturn and reorganize it? The realist hegemonic perspective expects today's power transition to lead to growing struggles between the West and the rest over global rules and institutions. In contrast, this essay argues that although America's hegemonic position may be declining, the liberal international characteristics of order - openness, rules, and multilateralism - Are deeply rooted and likely to persist. And even as China seeks in various ways to build rival regional institutions, there are stubborn limits on what it can do.

All Science Journal Classification (ASJC) codes

- Political Science and International Relations

- American power

- Liberal international order

- Liberal internationalism

- Multilateralism

- Power transitions

- Rising states

Access to Document

- 10.1017/S0892679418000072

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- world order Social Sciences 100%

- global rules Social Sciences 67%

- Multilateralism Arts & Humanities 64%

- China Arts & Humanities 60%

- multilateralism Social Sciences 54%

- Developing Countries Arts & Humanities 47%

- Openness Arts & Humanities 41%

- Realist Arts & Humanities 38%

T1 - Why the liberal world order will survive

AU - Ikenberry, G. John

N1 - Publisher Copyright: © Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs 2018.

PY - 2018/3/1

Y1 - 2018/3/1

N2 - The crisis of the American-led international order would seem to open up new opportunities for rising states-led by China, India, and other non-Western developing countries - To reshape the global order. As their capacities and influence grow, will these states rise up and integrate into the existing order or will they seek to overturn and reorganize it? The realist hegemonic perspective expects today's power transition to lead to growing struggles between the West and the rest over global rules and institutions. In contrast, this essay argues that although America's hegemonic position may be declining, the liberal international characteristics of order - openness, rules, and multilateralism - Are deeply rooted and likely to persist. And even as China seeks in various ways to build rival regional institutions, there are stubborn limits on what it can do.

AB - The crisis of the American-led international order would seem to open up new opportunities for rising states-led by China, India, and other non-Western developing countries - To reshape the global order. As their capacities and influence grow, will these states rise up and integrate into the existing order or will they seek to overturn and reorganize it? The realist hegemonic perspective expects today's power transition to lead to growing struggles between the West and the rest over global rules and institutions. In contrast, this essay argues that although America's hegemonic position may be declining, the liberal international characteristics of order - openness, rules, and multilateralism - Are deeply rooted and likely to persist. And even as China seeks in various ways to build rival regional institutions, there are stubborn limits on what it can do.

KW - American power

KW - Hegemony

KW - Liberal international order

KW - Liberal internationalism

KW - Multilateralism

KW - Power transitions

KW - Rising states

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85052550248&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=85052550248&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1017/S0892679418000072

DO - 10.1017/S0892679418000072

M3 - Review article

AN - SCOPUS:85052550248

SN - 0892-6794

JO - Ethics and International Affairs

JF - Ethics and International Affairs

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, 2024 global development forum, 2024 global development forum: keynote remarks and fireside discussion with representative mike gallagher (r-wi), unpacking the 2024 south korean elections: capital cable #92, 2024 global development forum: balancing economic growth, energy security, and decarbonization.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

- China Power Project

- Chinese Business and Economics

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

- Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Critical Minerals Security

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation Project

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Transnational Threats Project

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

World Order after Covid-19

Photo: Adobe Stock

Commentary by Seth G. Jones , Todd Harrison, Rebecca Hersman, Kathleen H. Hicks, and Samuel Brannen

Published May 28, 2020

The Covid-19 pandemic is reshaping geopolitics. Escalating tensions between the United States and China are the clearest immediate-term outcome. But what about the long-term impact?

CSIS Risk and Foresight Group Director Sam Brannen asked four of his International Security Program colleagues to take the long view on how Covid-19 could affect geopolitics out to 2025-2030 and beyond.

- Covid-19 has accelerated the transition to a more fragmented world order in which the future organizing principles of the international system are unclear.

- Neither China nor the United States is positioned to emerge from Covid-19 as a “winner” in a way that would dramatically shift the balance of world power in its favor.

- The economic effects of Covid-19 will increase downward pressure on U.S. and likely others’ defense budgets, which could affect the pace of force modernization.

- The “Great Power Competition” paradigm in the most recent National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy inaccurately describes this new geopolitical environment.

- In the new geopolitical environment, it is increasingly difficult for any single country to exercise its will, and multiple poles compete and cooperate.

- U.S. alliances hold in this world, though allies more selectively choose where to align with the United States versus choosing their own paths.

Kathleen Hicks

Senior Vice President Henry A. Kissinger Chair Director, International Security Program

Current U.S. debates over “great power competition” obscure the true state of international affairs that is evolving. Military and economic rivalry among the United States, China, and Russia is important to geopolitics, but so is the degree to which other “great powers,” some with nuclear weapons, seek alternative paths, potentially together. France, Germany, India, and Japan are powers in their own right, for example. This is why alliances and economic partnerships are so important in a world of increasing multipolarity.

Moreover, the United States and China will likely emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic having taken significant damage to their prestige and soft power. Neither country has distinguished itself or aided the international community significantly in responding.

Harold Brown Chair Director, Transnational Threats Project Senior Adviser, International Security Program

By 2025-2030, there will be multipolarity between different parties, with the United States, China, Russia, and the European Union representing different poles. But at the macro level, these poles may align around regime type, with the democratic United States and Europe aligned against Russia and China.

Regarding the United States, its alliance system may remain robust by 2025-2030 based on two assumptions. First, multipolarity increases incentives to cleave to parties with shared interests. Several rising poles in the new global order are authoritarian, with skeptical views of democracy, free press, and open markets. As global competition increases, there are structural and institutional incentives for democratic U.S. allies to band together to advance shared views and push back on regimes attempting to revise the international order.

The second assumption is that the United States could experience a change in political leadership. Future U.S. administrations, whether Republican or Democrat, are likely to favor a stronger alliance framework. While there are increasing domestic pressures for a foreign policy of restraint today, the United States will likely be cautious in actually implementing a more restrained foreign policy. A U.S. withdrawal from global affairs is complicated by existing, entangling relationships, including in institutions such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). While some in the United States might wish to play less of a global leadership role and pull back, other actors, such as Iran, Russia, China, and the Islamic State, also get a “vote.”

Rebecca Hersman

Director, Project on Nuclear Issues Senior Adviser, International Security Program

U.S. alliances, and with them the United States’ global leadership position, will likely weaken in this time frame as Europeans seek less dependence on the United States and hedge against unpredictable U.S. leadership. There is uncertainty in Asia as well. It is possible that the United States can recover its diminished position in the region, but the failure to negotiate basing agreements with the Republic of Korea and Japan and the extortionist approach taken by the current administration in these negotiations will be difficult to overcome. All of these factors are exacerbated by the competitive, zero-sum dynamics unleashed in this pandemic.

The outcome of the geopolitical competition will hinge to a large degree on the relative economic recovery of the United States and China from Covid-19 and the ability of other states, especially in Europe and Asia, to recover and coalesce around shared values and interests. Their ability to create counterweights rather than perpetuate a steady fragmentation of power will determine to a large degree how future U.S. influence looks particularly in Northeast and Southeast Asia relative to China.

An important note: The conditions of great power competition coupled with the economic pressures of Covid-19 can create opportunities for arms control based solely on strategic state interests. Arms control presents opportunities to reduce arms racing, stabilize competition, and manage conflict, which can further incentivize nonproliferation. These factors may be more galvanizing to states as incentivizes to encourage arms control than would Post-Cold War cooperation. It is plausible, perhaps even likely, that the United States, China, and Russia resort to arms control tools to manage great power competition.

Todd Harrison

Director, Defense Budget Analysis Director, Aerospace Security Project Senior Fellow, International Security Program

Russia is declining in relative power due to economics and demographics. It is a poor, crumbling state with limited capacity that happens to have a large nuclear arsenal. China’s economic trajectory is unlikely to continue as in the past, and though it continues to develop significant power, its domestic political stability presents an ongoing challenge for the Chinese Communist Party.

Any great power conflict in this decade would likely first manifest itself in space. Such a conflict could be non-kinetic and not publicly visible, relying on jamming, lazing, and cyber-based weaponry, and would be aimed at signaling seriousness and intent to adversaries. Space-based conflict provides an avenue to deter adversary involvement by preemptively denying space-based capabilities, making terrestrial action more expensive or difficult for an adversary that needs to operate globally over long distances. For example, prior to an invasion of the Baltic States, Russia could signal its will and the cost of intervention to the United States and NATO by launching reversible attacks against space-based assets that NATO forces rely on, slowing operations and raising the potential cost of intervention.

Sam Brannen leads the Risk and Foresight Group and is a senior fellow in the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

Commentary is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2020 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

Seth G. Jones

Kathleen H. Hicks

Samuel brannen, programs & projects.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Democracies and World Order

Introduction, general overviews.

- Wilsonianism

- The Cold War

- The First Bush Administration

- The Clinton Era

- The Second Bush Administration

- Democracy in an Era of American Retrenchment

- Human Rights

- Inequalities

- The (Neo)Institutionalists

- The Democratic Peace Theory and its Critics

- Economic Liberalism, International Regimes, and Trade

- The Liberal Internationalist Order

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Democracy and Conflict

- Global Civil Society

- Global Justice, Western Perspectives

- US–UK Special Relationship

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Crisis Bargaining

- History of Brazilian Foreign Policy (1808 to 1945)

- Indian Foreign Policy

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Democracies and World Order by Gabriela Marin Thornton LAST REVIEWED: 24 February 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 30 June 2014 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199743292-0067

What do we mean by world order? How can world order be defined, and what is the relationship between democracies and world order? Are democracies important pillars of world order? Furthermore, in what kind of world order can human aspirations best be fulfilled? Scholars of international relations (IR) have been wrestling with these questions since the inception of the IR disciple in the aftermath of World War I. It should be stated that from the beginning there has been no consensus in IR over the meaning of the term “world order.” The definition of democracy is also contested among political scientists. The link between democracies and various types of world orders is a matter of dispute, too. Moreover, the literature that defines both democracy and world order is voluminous. Realist scholars tend to conceptualize world order as a system of states in which the distribution of hard power creates various types of orders such as multipolar, bipolar, or unipolar. International political economy and Marxist scholars mostly equate world order with the capitalist global economy. In general, realists, international political economists, and Marxists scholars see the world order as an arrangement of actors such as great powers or economic classes. On the other hand, liberals, constructivists, and globalists view the world order as a process in which states or dominant classes are not the only actors. Various transnational institutions, norms, and values transcend borders and continuously shape world politics. This article is structured as follows: First, it maps out resources that exemplify the link between democracies and world order from President Woodrow Wilson to President George W. Bush. Second, the article provides resources that explore the link between democracy and globalization: a concept that mostly displaced that of world order in the mid-1990s. Third, the article analyzes the link between democracies and various forms of liberal orders. This article devotes considerable space to the world order created by the United States because the United States has been the only great power that has created a world order in which democracy and its promotion has played a central role.

The annotated sources in this section are ground breaking works on world order. Represented here are works coming from: (i) the English School of international relations, such as Bull 1977 ; (ii) the critical/historical materialist school, such as Cox 1987 ; (iii) various schools of liberal thought, including Ikenberry 2009 and Slaughter 2004 ; (iv) the globalization school, such as Held 1995 ; and (v) the Marxist and deconstructivist school, such as Hardt and Negri 2000 . Huntington’s crucial work The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order Huntington 1996 ) and Peter J. Katzenstein’s A World of Regions: Asia and Europe in the American Imperium ( Katzenstein 2005 ) are also discussed. Bull 1977 argues for a world order that supersedes the anarchical Hobbsian realist system and even supersedes the concept of international society initially advanced by the English School. Bull argues that order should take precedent over justice. Cox 1987 presents us with a different conceptualization of the world order: a world order whose main characteristic is change fueled by the transformation of the global economic system. The connection between the world order and democracy appears superfluous in both works. By contrast, the liberals and the globalists play this connection strongly, albeit in different ways. Ikenberry 2009 sees democracies as an important part of the world order. Slaughter 2004 argues that government networks are the key feature of the world order in the 21st century. Held 1995 goes from classical democracy (within the state) to cosmopolitan democracy (beyond the state), and argues that the meaning of democracy should be rethought in an international society in which the state lost considerable power. Hardt and Negri 2000 define world order as empire. Empire is a specific regime of global relations of (neo)Marxist origins. Democracy is something the empire grows from within. Huntington 1996 , contradicting both the realist and the liberal theses, presents us with a vision of post-Cold War order in which wars will be fought not among states but among civilizations. According to Huntington the world order is an order of civilizations. Huntington argues strongly against US efforts to spread democracy. Katzenstein 2005 envisions a world order formed of regions tied to the “American Imperium” and whose cultures play an important role in world politics. Students and scholars of IR will benefit from the works presented in this section.

Bull, Hedley. The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics . New York: Columbia University Press, 1977.

Written by one of the most notable IR theorist, the book defines order in world politics, presents order in the contemporary international system as well as alternatives paths to world order. For Bull, the world order is formed from patterns or dispositions of human activity directed toward clearly defined goals.

Cox, Robert W. Production, Power, and World Order: Social Forces in the Making of History . New York: Columbia University Press, 1987.

Brilliant analysis of the liberal order, the era of rival imperialisms, and the Pax Americana, defined as a hegemonic order. Democracy is not viewed as an important factor of this order. The hallmark of Cox’s world order is transformational change brought about by the capitalist system.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. Empire . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

In this very provocative book the world order is conceptualized as empire—meaning a specific regime of capitalist global relations. Empire creates potential for resistance and revolution. The multitudes, which represents a global movement with democratic characteristics, will rise against the empire.

Held, David. Democracy and the Global Order: From the Modern State to Cosmopolitan Governance . Stanford, CA: Sanford University Press, 1995.

Notable work analyzes models of democracy and the formation and displacement of the modern state and introduces the concept of cosmopolitan democracy. The need for cosmopolitan democracy arises from a new international order characterized by multiple and overlapping networks of power that challenge the power of the state.

Huntington, Samuel P. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order . New York: Simon & Shuster, 1996.

Preeminent scholar presented a powerful vision of the post-Cold War order in which new wars would be fought not among states but among civilizations. The world order would be based on civilizations. The civilizational order would require the West to abandon the spreading of democracy and strengthen itself culturally.

Ikenberry, G. John. “Liberal Internationalism 3.0: America and the Dilemmas of Liberal Order.” Perspectives on Politics 7.1 (March 2009): 71–87.

DOI: 10.1017/S1537592709090112

Preeminent liberal argues that the liberal international order is not a fixed order. It encompasses among other factors open markets, cooperative security, international institutions and the democratic community. It differentiates among liberal internationalism: 1.0 Woodrow Wilson; 2.0 Cold War; and 3.0 post-hegemonic liberal internationalism whose tenants are not clear yet.

Katzenstein, Peter J. A World of Regions: Asia and Europe in the American Imperium . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005.

Katzenstein’s world order is an order dominated by the American Imperium in which regions interact closely. The cultural aspect of world regions is very important in the shaping of the world order as exemplified by Europe and Asia.

Slaughter, Anne-Marie. A New World Order . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Slaughter’s main claim is that government networks are the key feature of the world order in the 21st century. Those networks bolster the power of the state. Slaughter’s new world order requires a new conception of democracy in which uncertainty and unintended consequences should be accepted as facts of life.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About International Relations »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Theories of International Relations Since 1945

- Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb

- Arab-Israeli Wars

- Arab-Israeli Wars, 1967-1973, The

- Armed Conflicts/Violence against Civilians Data Sets

- Arms Control

- Asylum Policies

- Audience Costs and the Credibility of Commitments

- Authoritarian Regimes

- Balance of Power Theory

- Bargaining Theory of War

- Brazilian Foreign Policy, The Politics of

- Canadian Foreign Policy

- Case Study Methods in International Relations

- Casualties and Politics

- Causation in International Relations

- Central Europe

- Challenge of Communism, The

- China and Japan

- China's Defense Policy

- China’s Foreign Policy

- Chinese Approaches to Strategy

- Cities and International Relations

- Civil Resistance

- Civil Society in the European Union

- Cold War, The

- Colonialism

- Comparative Foreign Policy Security Interests

- Comparative Regionalism

- Complex Systems Approaches to Global Politics

- Conflict Behavior and the Prevention of War

- Conflict Management

- Conflict Management in the Middle East

- Constructivism

- Contemporary Shia–Sunni Sectarian Violence

- Counterinsurgency

- Countermeasures in International Law

- Coups and Mutinies

- Criminal Law, International

- Critical Theory of International Relations

- Cuban Missile Crisis, The

- Cultural Diplomacy

- Cyber Security

- Cyber Warfare

- Decision-Making, Poliheuristic Theory of

- Demobilization, Post World War I

- Democracies and World Order

- Democracy in World Politics

- Deterrence Theory

- Development

- Digital Diplomacy

- Diplomacy, Gender and

- Diplomacy, History of

- Diplomacy in the ASEAN

- Diplomacy, Public

- Disaster Diplomacy

- Diversionary Theory of War

- Drone Warfare

- Eastern Front (World War I)

- Economic Coercion and Sanctions

- Economics, International

- Embedded Liberalism

- Emerging Powers and BRICS

- Empirical Testing of Formal Models

- Energy and International Security

- Environmental Peacebuilding

- Epidemic Diseases and their Effects on History

- Ethics and Morality in International Relations

- Ethnicity in International Relations

- European Migration Policy

- European Security and Defense Policy, The

- European Union as an International Actor

- European Union, International Relations of the

- Experiments

- Face-to-Face Diplomacy

- Fascism, The Challenge of

- Feminist Methodologies in International Relations

- Feminist Security Studies

- Food Security

- Forecasting in International Relations

- Foreign Aid and Assistance

- Foreign Direct Investment

- Foreign Policy Decision-Making

- Foreign Policy of Non-democratic Regimes

- Foreign Policy of Saudi Arabia

- Foreign Policy, Theories of

- French Empire, 20th-Century

- From Club to Network Diplomacy

- Future of NATO

- Game Theory and Interstate Conflict

- Gender and Terrorism

- Genocide, Politicide, and Mass Atrocities Against Civilian...

- Genocides, 20th Century

- Geopolitics and Geostrategy

- Germany in World War II

- Global Citizenship

- Global Constitutionalism

- Global Environmental Politics

- Global Ethic of Care

- Global Governance

- Globalization

- Governance of the Arctic

- Grand Strategy

- Greater Middle East, The

- Greek Crisis

- Hague Conferences (1899, 1907)

- Hierarchies in International Relations

- History and International Relations

- Human Nature in International Relations

- Human Rights and Humanitarian Diplomacy

- Human Rights, Feminism and

- Human Rights Law

- Human Security

- Hybrid Warfare

- Ideal Diplomat, The

- Identity and Foreign Policy

- Ideology, Values, and Foreign Policy

- Illicit Trade and Smuggling

- Imperialism

- Indian Perspectives on International Relations, War, and C...

- Indigenous Rights

- Industrialization

- Intelligence

- Intelligence Oversight

- Internal Displacement

- International Conflict Settlements, The Durability of

- International Criminal Court, The

- International Economic Organizations (IMF and World Bank)

- International Health Governance

- International Justice, Theories of

- International Law, Feminist Perspectives on

- International Monetary Relations, History of

- International Negotiation and Conflict Resolution

- International Nongovernmental Organizations

- International Norms for Cultural Preservation and Cooperat...

- International Organizations

- International Relations, Aesthetic Turn in

- International Relations as a Social Science

- International Relations, Practice Turn in

- International Relations, Research Ethics in

- International Relations Theory

- International Security

- International Society

- International Society, Theorizing

- International Support For Nonstate Armed Groups

- Internet Law

- Interstate Cooperation Theory and International Institutio...

- Intervention and Use of Force

- Interviews and Focus Groups

- Iran, Politics and Foreign Policy

- Iraq: Past and Present

- Japanese Foreign Policy

- Just War Theory

- Kurdistan and Kurdish Politics

- Law of the Sea

- Laws of War

- Leadership in International Affairs

- Leadership Personality Characteristics and Foreign Policy

- League of Nations

- Lean Forward and Pull Back Options for US Grand Strategy

- Mediation and Civil Wars

- Mediation in International Conflicts

- Mediation via International Organizations

- Memory and World Politics

- Mercantilism

- Middle East, The Contemporary

- Middle Powers and Regional Powers

- Military Science

- Minorities in the Middle East

- Minority Rights

- Morality in Foreign Policy

- Multilateralism (1992–), Return to

- National Liberation, International Law and Wars of

- National Security Act of 1947, The

- Nation-Building

- Nations and Nationalism

- NATO, Europe, and Russia: Security Issues and the Border R...

- Natural Resources, Energy Politics, and Environmental Cons...

- New Multilateralism in the Early 21st Century

- Nonproliferation and Counterproliferation

- Nonviolent Resistance Datasets

- Normative Aspects of International Peacekeeping

- Normative Power Beyond the Eurocentric Frame

- Nuclear Proliferation

- Peace Education in Post-Conflict Zones

- Peace of Utrecht

- Peacebuilding, Post-Conflict

- Peacekeeping

- Political Demography

- Political Economy of National Security

- Political Extremism in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Political Learning and Socialization

- Political Psychology

- Politics and Islam in Turkey

- Politics and Nationalism in Cyprus

- Politics of Extraction: Theories and New Concepts for Crit...

- Politics of Resilience

- Popuism and Global Politics

- Popular Culture and International Relations

- Post-Civil War State

- Post-Conflict and Transitional Justice

- Post-Conflict Reconciliation in the Middle East and North ...

- Power Transition Theory

- Preventive War and Preemption

- Prisoners, Treatment of

- Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs)

- Process Tracing Methods

- Pro-Government Militias

- Proliferation

- Prospect Theory in International Relations

- Psychoanalysis in Global Politics and International Relati...

- Psychology and Foreign Policy

- Public Opinion and Foreign Policy

- Public Opinion and the European Union

- Quantum Social Science

- Race and International Relations

- Rebel Governance

- Reconciliation

- Reflexivity and International Relations

- Religion and International Relations

- Religiously Motivated Violence

- Reputation in International Relations

- Responsibility to Protect

- Rising Powers in World Politics

- Role Theory in International Relations

- Russian Foreign Policy

- Russian Revolutions and Civil War, 1917–1921

- Sanctions in International Law

- Science Diplomacy

- Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), The

- Secrecy and Diplomacy

- Securitization

- Self-Determination

- Shining Path

- Sinophone and Japanese International Relations Theory

- Small State Diplomacy

- Social Scientific Theories of Imperialism

- Sovereignty

- Soviet Union in World War II

- Space Strategy, Policy, and Power

- Spatial Dependencies and International Mediation

- State Theory in International Relations

- Status in International Relations

- Strategic Air Power

- Strategic and Net Assessments

- Sub-Saharan Africa, Conflict Formations in

- Sustainable Development

- Systems Theory

- Teaching International Relations

- Territorial Disputes

- Terrorism and Poverty

- Terrorism, Geography of

- Terrorist Financing

- Terrorist Group Strategies

- The Changing Nature of Diplomacy

- The Politics and Diplomacy of Neutrality

- The Politics and Diplomacy of the First World War

- The Queer in/of International Relations

- the Twenty-First Century, Alliance Commitments in

- The Vienna Conventions on Diplomatic and Consular Relation...

- Theories of International Relations, Feminist

- Theory, Chinese International Relations

- Time Series Approaches to International Affairs

- Transnational Actors

- Transnational Law

- Transnational Social Movements

- Tribunals, War Crimes and

- Trust and International Relations

- UN Security Council

- United Nations, The

- United States and Asia, The

- Uppsala Conflict Data Program

- US and Africa

- Voluntary International Migration

- War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714)

- Weapons of Mass Destruction

- Western Balkans

- Western Front (World War I)

- Westphalia, Peace of (1648)

- Women and Peacemaking Peacekeeping

- World Economy 1919-1939

- World Polity School

- World War II Diplomacy and Political Relations

- World-System Theory

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|193.7.198.129]

- 193.7.198.129

A New World Order?

The war in Ukraine. The rise of China. The weakening of democratic norms. We asked BC experts about the future of the liberal world order.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the largest attack in Europe since World War II, has set off waves of speculation about whether the international order that has regulated the planet for three-quarters of a century is beginning to crumble. An ascendent China is challenging America for global primacy. The West’s commitment to democratic norms seems more fragile than at any time in memory. And Russia, long recognized as one of the world’s superpowers, is suddenly looking more like a paper tiger. What does all of this mean for the future of the world order? We asked a number of BC experts, and ahead we present their thoughts on the future of everything from the United States and China to Russia, NATO, and nuclear nonproliferation.

On the World after Ukraine

By James E. Cronin, research professor in history For three-quarters of a century, the international order has persevered. Now it suddenly finds itself challenged by Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine. The order has now suffered a serious rupture that will not be quickly or easily repaired. Read the entire essay.

By Paul T. Christensen, political science professor of the practice Putin and his elite allies who currently rule Russia never believed that the cold war ended, and they never accepted the loss of a significant proportion of “Russia’s” territory, population, and influence that the dissolution of the Soviet Union entailed. Read the entire essay.

A Q&A with Robert S. Ross, political science professor China is a major international trading partner, a major market for the world. The question is, will it rival the United States as a great power around the world? I think that, beyond East Asia, it’s going to be simply a global presence, not a global power. Read the entire Q&A.

By Seth Jacobs, history professor NATO has become obsolete. Indeed, Washington’s whole Europe-first orientation is anachronistic, a wasteful, expensive holdover from the cold war that ought to have been abandoned years ago and that distracts us from the true dangers we face abroad. Read the entire essay.

On Arms Control

A Q&A with Jennifer L. Erickson, political science associate professor There’s always the potential for unintended consequences with arm sales, however justified they are. A basic problem for countries that sell weapons is that once you sell them you’ve given up practical control of them. Read the entire Q&A.

On the Middle East

By Ali Banuazizi, research professor of political science Despite economic hardships and diplomatic pressures, Middle Eastern leaders, while expressing sympathy for the Ukrainian victims of the war, have refrained from condemning Russia’s aggression. Read the entire essay.

More Stories

Children and Natural Disasters

Kids and disasters.

As catastrophic events become more frequent, BC's Betty Lai is researching how to promote recovery and resilience in children.

Guy Beiner

The new Sullivan Chair in Irish Studies on how we remember our past, and why it matters.

A Gallery-Worthy Gift

Peter Lynch ’65 has donated more than $20 million in art from his private collection to the McMullen Museum of Art at BC.

Nicholas Burns '78 Is the New Ambassador to China

Nicholas burns is the new ambassador to china .

The BC alum tweeted that he’s looking forward to doing “vital work for our country.”

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, the new world order and global public administration: a critical essay.

Comparative Public Administration

ISBN : 978-0-76231-359-4 , eISBN : 978-1-84950-453-9

Publication date: 22 December 2006

The concept of a New World Order is a rhetorical device that is not new. In fact, it is as old as the notion of empire building in ancient times. When Cyrus the Great conquered virtually the entire known world and expanded his “World-State” Persian Achaemenid Empire, his vision was to create a synthesis of civilization and to unite all peoples of the world under the universal Persian rule with a global world order characterized by peace, stability, economic prosperity, and religious and cultural tolerance. For two centuries that world order was maintained by both military might and Persian gold: Whenever the military force was not applicable, the gold did the job; and in most cases both the military and the gold functioned together (Frye, 1963, 1975; Farazmand, 1991a). Similarly, Alexander the Great also established a New World Order. The Romans and the following mighty empires had the same concept in mind. The concept was also very fashionable after World Wars I and II. The world order of the twentieth century was until recently a shared one, dominated by the two superpowers of the United States and the USSR.

Farazmand, A. (2006), "The New World Order and Global Public Administration: A Critical Essay", Otenyo, E.E. and Lind, N.S. (Ed.) Comparative Public Administration ( Research in Public Policy Analysis and Management, Vol. 15 ), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. 701-728. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0732-1317(06)15031-9

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2006, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Intro to Modern World History

11 Three World Order

Shelley Rose and Mark Cole

World War II destroyed the European-centered world that had emerged in the nineteenth century. In place of European world leadership and European empires, a three-world order emerged. The United States and the Soviet Union headed, respectively, the First and Second Worlds. Both of the super powers whole-heartedly believed in the universal applicability of their respective ideologies. The United States espoused liberal capitalism while the USSR did the same for communism. Soon after World War II, these two camps became engaged in a “cold war” to expand and counter each other’s global influence. The Third World consisted of formerly colonized and semicolonized nations, caught between the two superpowers’ rival ideological blocs. While most countries were able to free themselves of colonial rule, they were unable to overcome deep-rooted problems of poverty and underdevelopment. Moreover, Third World nations often became the staging ground for cold war conflicts. By the 1960s and 1970s, stresses appeared in this three-world order. Unrest and discontent boiled to the surface in all three worlds in different forms. New sources of power, multinational corporations, nongovernmental organizations, and oil-rich states shifted the balance of economic wealth and posed new problems.

Objectives:

After completing Module 11 you will be able to:

- Explain the relationship between World War II and the three-world order.

- Analyze the extent to which World War II was a global war.

- Assess the roles that the United States and the Soviet Union played in the Cold War.

- Identify the goals of Third World states in this period, and evaluate the degree to which these goals were achieved.

- Compare the civil rights issues in the first, second, and third worlds, and assess the ways each “world” addressed these and other basic rights.

Section 1: Cold War and Revolutions of 1989

- Read Making the History of 1989

- Create a narrative in the app of your (or your instructor’s) choice from the perspective of one of the historical figures in these documents. Present their arguments in the first-person .

- Post the link to your on the course discussion board.

Global Interconnections: Modern World History 1300-present by Shelley Rose and Mark Cole is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

There Is No Liberal World Order

Unless democracies defend themselves, the forces of autocracy will destroy them.

I n February 1994 , in the grand ballroom of the town hall in Hamburg, Germany, the president of Estonia gave a remarkable speech . Standing before an audience in evening dress, Lennart Meri praised the values of the democratic world that Estonia then aspired to join. “The freedom of every individual, the freedom of the economy and trade, as well as the freedom of the mind, of culture and science, are inseparably interconnected,” he told the burghers of Hamburg. “They form the prerequisite of a viable democracy.” His country, having regained its independence from the Soviet Union three years earlier, believed in these values: “The Estonian people never abandoned their faith in this freedom during the decades of totalitarian oppression.”

But Meri had also come to deliver a warning: Freedom in Estonia, and in Europe, could soon be under threat. Russian President Boris Yeltsin and the circles around him were returning to the language of imperialism, speaking of Russia as primus inter pares —the first among equals—in the former Soviet empire. In 1994, Moscow was already seething with the language of resentment, aggression, and imperial nostalgia; the Russian state was developing an illiberal vision of the world, and even then was preparing to enforce it. Meri called on the democratic world to push back: The West should “make it emphatically clear to the Russian leadership that another imperialist expansion will not stand a chance.”

At that, the deputy mayor of St. Petersburg, Vladimir Putin, got up and walked out of the hall .

Explore the May 2022 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Meri’s fears were at that time shared in all of the formerly captive nations of Central and Eastern Europe, and they were strong enough to persuade governments in Estonia, Poland, and elsewhere to campaign for admission to NATO. They succeeded because nobody in Washington, London, or Berlin believed that the new members mattered. The Soviet Union was gone, the deputy mayor of St. Petersburg was not an important person, and Estonia would never need to be defended. That was why neither Bill Clinton nor George W. Bush made much attempt to arm or reinforce the new NATO members. Only in 2014 did the Obama administration finally place a small number of American troops in the region, largely in an effort to reassure allies after the first Russian invasion of Ukraine.