Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

The People Power Revolution, Philippines 1986

- Mark John Sanchez

For a moment, everything seemed possible. From February 22 to 25, 1986, hundreds of thousands of Filipinos gathered on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue to protest President Ferdinand Marcos and his claim that he had won re-election over Corazon Aquino.

Soon, Marcos and his family were forced to abdicate power and leave the Philippines . Many were optimistic that the Philippines, finally rid of the dictator, would adopt policies to address the economic and social inequalities that had only increased under Marcos’s twenty-year rule. This People Power Revolution surprised and inspired anti-authoritarian activists around the world.

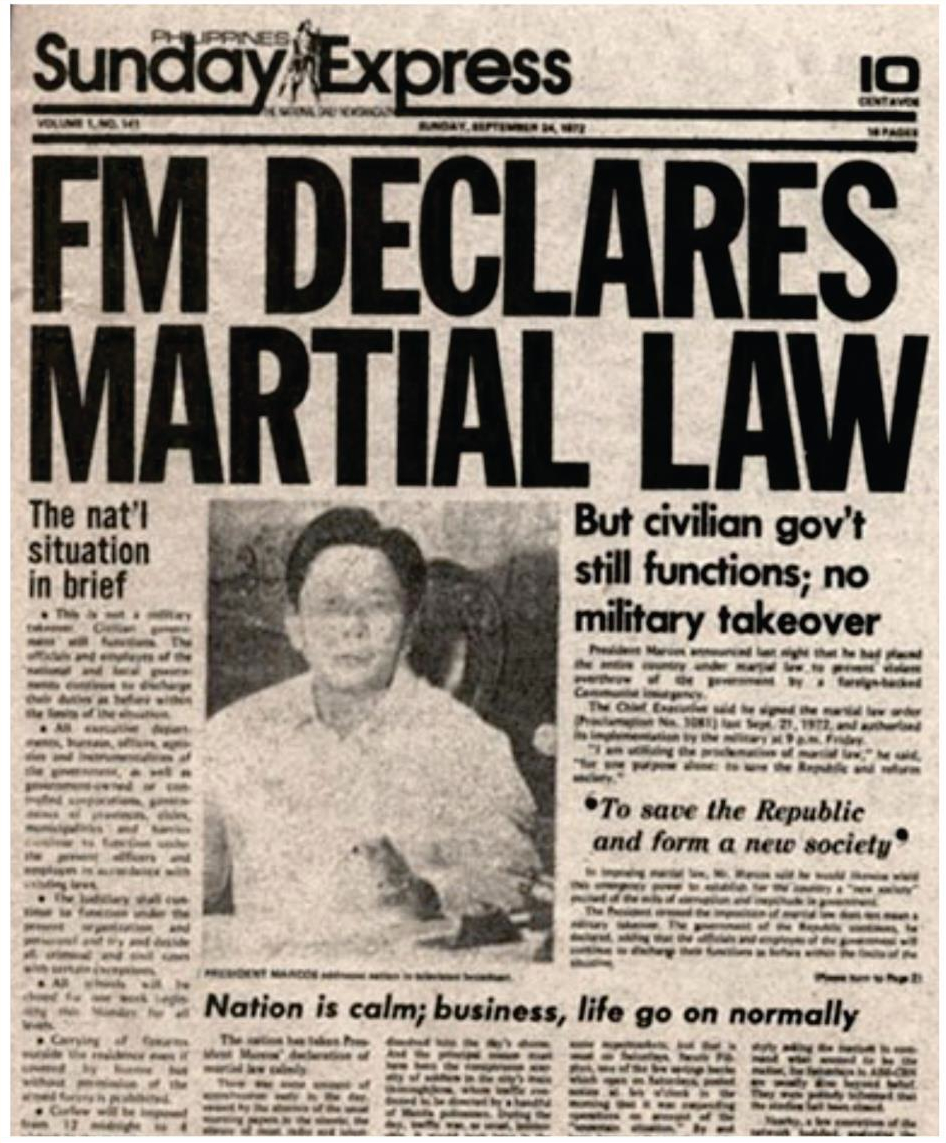

Ferdinand Marcos had been president of the Philippines since 1965. After declaring martial law in 1972, he suspended and eventually rewrote the Philippine constitution, curtailed civil liberties, and concentrated power in the executive branch and among his closest allies. Marcos had tens of thousands of opponents arrested and thousands tortured, killed, or disappeared.

The Sunday Express headline from September 24, 1972 shortly after Marcos declared martial law.

For two decades, Filipinos lived under authoritarian rule while Marcos and his allies enriched themselves through ownership of Philippine press and industry outlets and through the siphoning of funds from U.S., World Bank , and International Monetary Fund loans.

The People Power movement had been building since well before Marcos’s declaration of martial law. Committed activists who organized underground in the Philippines, in exile, and in the diaspora worked tirelessly to broadcast news of the Marcoses’ human rights violations and ill-gotten wealth globally.

For many years, however, much of the world—the U.S. government in particular—was perfectly willing to overlook the corruption of the Marcoses in exchange for an anti-Communist bulwark in Southeast Asia.

By the mid-1980s, however, foreign policy calculations had shifted against Marcos in crucial ways.

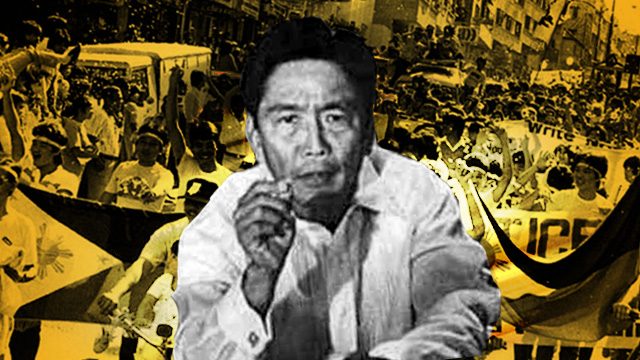

Senator Benigno Aquino in an interview with Pat Robertson before his assassination in 1983.

The August 1983 assassination of Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. was seen by many around the world as a particularly brazen act of political retribution. Furthermore, rumors about Marcos’s health (he was suffering from lupus and regularly undergoing dialysis at the time) led many of his allies in the Philippines and beyond to begin speculating about the dictator’s successors.

When Ferdinand Marcos boldly called for a “snap election” in a 1985 interview with David Brinkley, Marcos’s opponents weighed whether this was an opportunity or a trap. Many times before, Marcos had tipped the electoral balances in his favor, through a rewriting of laws, outright violence, and other forms of manipulation and intimidation.

Much of the Philippine Left decided to boycott the election, fearful that participation would only serve to further legitimize the regime. The remainder of the opposition movement eventually coalesced around the widow of Senator Aquino, Corazon “Cory” Aquino.

Just as many feared, Marcos claimed victory in the election. This time, though, Filipinos refused to accept this lie. On February 22, citizens took to the streets on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA). Cardinal Jaime Sin, the Archbishop of Manila, called upon Filipinos to support the peaceful protests.

Cardinal Jaime Sin pictured in 1988.

Marcos ordered the military to repress the mass action. However, a faction of military officers refused to clamp down on the protestors and chose instead to defect. This group included soldiers who had grown frustrated with corruption in the military and the Marcos regime and had earlier formed the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM).

When Marcos ordered the military to arrest detractors, Cardinal Sin called upon the people to shield them. The Catholic radio organ, Radio Veritas , became a major control center for protest communications during the People Power movement.

Close Marcos ally President Ronald Reagan eventually sent word through Senator Paul Laxalt that it was time to “cut, and cut cleanly,” signaling that Marcos no longer had the backing of his most powerful ally. On the evening of February 25, the U.S. government facilitated Marcos’s escape to Hawaii, where he would remain until his death in 1989.

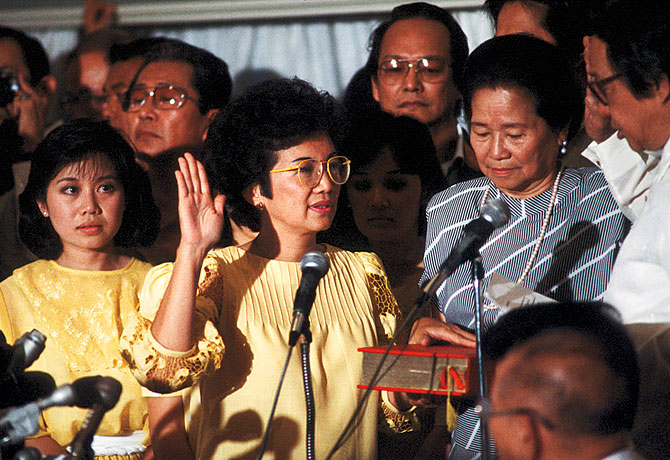

Later that same night, protestors stormed Malacañang Palace, exposing the opulent wealth that the Marcos family had amassed during their time in power. As Corazon Aquino was sworn in as President, Filipinos were hailed around the world as an example of peaceful revolution and the restoration of democracy.

Corazon Aquino was inaugurated as the 11th president of the Philippines on February 25, 1986 at Sampaguita Hall.

The road ahead would not be so simple, however. In the years since 1986, the legacy of the People Power Revolution has remained uncertain. Aquino faced several coup attempts during her time in power, many of them led by the very same RAM that had helped facilitate her rise to power.

The agricultural and economic reform that many Filipinos hoped for in a post-Marcos world did not come. Peace talks with the Communist Party of the Philippines dissolved and leftists continued to be maligned, attacked, and hunted.

Many Filipinos expressed nostalgia for the very dictator that had been overthrown. And there have been ongoing projects of historical revisionism in the Philippines that sanitized the Marcos years.

The Marcos family have returned to the Philippines and to positions of political prominence: Ferdinand Marcos’s widow Imelda became a congresswoman and his daughter Imee a governor. Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the dictator’s son and evident successor to his father’s legacy, ran for vice president in 2016 and finished a close second. Bongbong refused to concede and, to this day, continues his legal challenges to the election.

President Rodrigo Duterte talks to Imee Marcos at a wedding ceremony in Manila, September, 2016.

The most concerning outcome of the 2016 Philippine elections, however, was the election of Rodrigo Duterte as president. A close ally of the Marcoses, Duterte has drawn upon Marcos’s script for authoritarian power. He has arrested prominent opponents, curtailed civil liberties, and claimed that discipline is what is most needed for the Philippine nation.

Most infamously, Duterte launched a campaign that has resulted in tens of thousands of extrajudicial murders committed by police and military forces.

The People Power Movement offers several lessons. We can see the courageous solidarities and coalitions that might mobilize against authoritarian restrictions on civil liberties. But we must also look at the importance of finding ways to build anew and address the grievances and injustices that have made such authoritarians so popular in the first place.

The EDSA protests in 1986 were a remarkable moment in Philippine history, a moment filled with the sense of unlimited hope and possibility. And for those with democratic dreams, it provides both a lesson and a warning for the battles ahead.

- Agri-Commodities

- Asean Economic Community

- Banking & Finance

- Business Sense

- Entrepreneur

- Executive Views

- Export Unlimited

- Harvard Management Update

- Monday Morning

- Mutual Funds

- Stock Market Outlook

- The Integrity Initiative

- Editorial cartoon

- Design&Space

- Digital Life

- 360° Review

- Biodiversity

- Environment

- Envoys & Expats

- Health & Fitness

- Mission: PHL

- Perspective

- Today in History

- Tony&Nick

- When I Was 25

- Wine & Dine

- Live & In Quarantine

- Bulletin Board

- Public Service

- The Broader Look

Today’s front page, Saturday, April 20, 2024

The 1986 Edsa Revolution: Lessons learned, then and now

- Joel C. Paredes

- February 20, 2022

- 11 minute read

Table of Contents Hide

Us connection, ‘disempowered’ people, euphoria, reality check, killings go on, post-edsa, ‘new direction’, the other side of the story, a fragile democracy.

SILVESTRE Afable, until now, remains awestruck with the “mercurial emotions” of over a million people who took to the streets for a four-day vigil to protect military rebels during the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution.

As the Ministry of National Defense (MND) information service chief, he was the only civilian in that hurriedly organized meeting on February 22, 1986, when then Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and Gen. Fidel Ramos, then chief of the Philippine Constabulary-Integrated National Police (PC-INP), declared they were withdrawing support from then President Ferdinand E. Marcos.

Afable confided that, at first, it was really only a matter of their survival after Malacañang uncovered a coup plot which, Afable said, was initially hatched by a group of disgruntled military officers led by then Col. Gregorio “Gringo” Honasan, who called themselves the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM).

Afable recalled phoning his family, telling them he might die at any moment, if the government troops loyal to the President moved in to quell the military uprising.

The strongman had just been proclaimed winner of the February 7 snap elections against popular opposition candidate Corazon Aquino, widow of Benigno ”Ninoy” Aquino Jr., who was gunned down on August 21, 1983, upon returning from a three-year US exile.

AFABLE admitted that the military rebels had “strategically” linked with US authorities as early as September, even before Marcos called for a presidential election amid pressure from Washington.

“At that point in time, the coordination with US elements was already very active with the rebel groups,” he said. That was also the time when the RAM’s “planning became a serious effort,” according to Afable.

Meanwhile, crowds had just been drawn to Edsa, outside Camps Aguinaldo and Crame, by a call from influential Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin, as droves of officers, lawmakers and high-profile government officials started abandoning the Marcos camp after his pyrrhic victory. The “revolution of the people,” General Ramos called it, after what began as a military uprising drew civilians pledged to protect the rebel soldiers.

“That was the first time that I realized that Filipinos were really crazy if you awaken their emotions. They will not sleep. They will not go home,” he said. “It’s really hair-raising to look at a million people around you. It gives you an insight on what kind of people we were [then],” Afable said.

And yet, Afable believes that while he finds the 1986 People Power Revolution that ousted Marcos after 21 years in power remains to be relevant today, it might not happen again for different reasons.

IN Afable’s view, the Edsa revolt “was more of the middle class. These are people who had lots of aspirations.”

“[But] people now are very disempowered economically,” he said. “Today, people are totally different. They’re so hard up. It’s very hard to awaken any political ideals.”

He was also hardly surprised that Enrile and Honasan have since mended ties with the Marcoses, throwing their support behind the strongman’s son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., in his bid this May 9 to regain the presidency his father lost.

“JPE [Enrile] is really a pure pragmatist. He makes decisions on the parameter of pragmatic things,” Afable said. He also painted Honasan as, “such a congenial person with a lot of patriotism,” adding he is one who “would not just shoot a person.”

Saying that “he [Honasan] took it as a matter of political expediency,” Afable insisted that Honasan remains allied to his Philippine Military Academy classmate Ping Lacson, another presidential hopeful, and “had simply accepted the support of BBM [Bongbong Marcos].”

Honasan was named part of the Senate slate of Marcos Jr., who framed his choices as in line with his UniTeam’s consistent vision of national unity for progress.

Meanwhile, Afable noted how, under liberal democracy, “we have not moved upwards” despite the promises of leaders in the post-Marcos era. “We never really broke the cycle of corruption even if we had brought him [Marcos] down,” said Afable, who ironically started as a social activist of the left-wing Movement for the Advancement of Nationalism (MAN) at the University of the Philippines. After Edsa, Afable continued to serve the government in various capacities, and, before returning home to Baguio, was part of President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo’s cabinet.

THOUGH they were caught up in the euphoria of the “1986 People Power,” Dr. Aurora Parong was not blind to the background of the coup plotters with whom they shared the final moments that led to the ouster of the late strongman.

“These are the people who ordered the [political dissidents’] arrest. [Juan Ponce] Enrile and [Fidel] Ramos, they knew the torturers of the martial law regime,” said Parong, a member the Medical Action Group (MAG), which provided medical assistance to Edsa protesters.

She had been active with the MAG following her release in 1984 from over a year in detention for charges of inciting to rebellion, a case that stemmed from her choice to practice medicine in her hometown of Bayombong in Nueva Vizcaya.

“I kept asking myself, ‘Was it right to support them, just to oust Marcos?’” Parong recalled.

Still, Parong noted that she eventually considered the Edsa uprising as part of a continuing struggle against the dictatorship, since her student days at the University of the Philippines. Her idealism, she pointed out, was also what prompted her to return to the barrio and set up her own clinic after graduation.

On the second day at Edsa, Parong already had a hint that there won’t be any violence. Their vigil, she recalled, had included parents and their children, along with people who never really had any political involvement.

“It was already like a picnic. Still, we maintained our vigilance since you really don’t know what will happen later,” she said.

ON those four historic days, student leader Leandro Alejandro and his wife Lidy were manning the Bayan secretariat after left-wing militants joined Corazon Aquino’s call for civil disobedience.

“We went to Edsa and helped mobilize people, not just in support of the mutineers but because it was an uprising against the dictatorship,” said Lidy. “ S’yempre, merong pag-aalinlangan dahil nandiyan na yung mga elite ume-eksena . Meron kasi tayong kasabihan: ikaw ang nagtanim, nag-ani at nagluto, pero iba ang kakain [Of course there was hesitation, because the elite were starting to project themselves. We have a saying: you plant the seeds, harvest and cook, but someone else eats].”

Worse, they were accused of being “outsiders” during the uprising because a big segment of the militant movement joined the boycott of the “sham” snap elections.

No less than Bayan chair, the late Sen. Lorenzo Tañada, the “grand old man of the Philippine opposition,” went on leave from the alliance, which was trying to build a wide anti-dictatorship network, and decided to campaign for Mrs. Aquino.

“So, Cory lost [the election]. She was cheated. It was when Marcos was proclaimed the winner and that was enough reason to mobilize the people towards civil disobedience,” Liddy said. Then, when Corazon Aquino was finally swept to power, the militants were largely marginalized.

Meanwhile, Parong volunteered in the new government community health program, with then DSWD Secretary Mita Pardo de Tavera. She saw the bright prospects of a new government anchored and the accompanying democratic space, when Mrs. Aquino ordered the release of all political prisoners and convened a commission to draft a new Constitution under a “revolutionary government.”

On November 13, 1986, however, tragedy struck: Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU) leader Rolando Olalia and his driver Leonor Alay-ay were found dead in Antipolo, Rizal—their bodies mutilated.

Ka Lando, as he was known in the Labor movement, was one of the handfuls of militants who opened a dialogue with the new President, particularly in the labor sector, after joining a unity rally during the May 1 Labor Day celebration that year.

A National Bureau of Investigation report said the killings were a prelude to the staging of “God Save the Queen,” a coup plot blamed on the RAM to rid the Aquino Cabinet of left-wing members. After three decades, the Antipolo Regional Trial Court found three RAM members guilty of two counts of murder and meted with the penalty of up to 40 years imprisonment. Nine other accused remain at large, and the brains behind the killings remained a mystery.

On January 22, 1987, the farmers’ march calling for comprehensive land reforms ended in violence when anti-riot personnel, including lawmen in plain clothes, opened fire on unarmed protesters, killing at least 12 and injuring 51 protesters near Mendiola Bridge leading to Malacañang Palace.

A month later, a platoon of government troops killed 17 farmers and their families, including six children, in Sitio Padlao in Lupao, Nueva Ecija, in retaliation for the death of their commanding officer who was sniped by New People’s Army (NPA) guerrillas.

After the “Lupao Massacre,” Mrs. Aquino immediately declared “total war” against the communist rebels despite talks of possible peace to end the communist insurgency, one of the reasons Marcos had used to justify Martial Law in 1972. At least 24 soldiers of the 14th Infantry Battalion were tried before a military court but were all acquitted.

Parong, who was then already a member of the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines, recalled that Sister Mariani Dimaranan, the TFD chair, along with Sen. Jose Diokno, resigned from the Presidential Human Rights Commission to protest of the new government’s “total war” policy.

On September 19, 1987, Lean Alejandro was on his way to the Bayan office in Quezon City when a van cut into the path of his vehicle; a gunman rolled down the driver’s window and fatally shot him in the back and face with a single bullet. He had just announced at a National Press Club news conference the militants’ plans for a nationwide strike against the military’s role in government.

Lidy, his widow, said she was never approached by any investigator on the case and the official probe was suddenly stopped two weeks later. No suspect was charged in court.

Before Mrs. Aquino’s term ended in 1992, a group of non-government organizations tagged some 50 right-wing vigilante groups as being backed by the military, citing a wave of human-rights abuses that resulted in the deaths of 1,064 people, mostly farmers and workers, the disappearance of 830 others and 135 cases of massacre.

“The insurgency continued because the changes that they were expecting never happened,” Parong said. Reforms that were integrated in government, she noted, “had not really changed the mindset of the military and police related to human rights.”

Nonetheless, Parong said Edsa remains relevant, not just because it continued to inspire nonviolent regime change, as seen in East Germany and many other former Soviet bloc countries at the end of the Cold War era in 1989.

The struggle never ended, in her view.

“For several years, there were struggles against the dictatorship and there were struggles for economic change, but Edsa would not have happened unless several sectors organized themselves, and they had been struggling for sectoral changes,” she said.

She also cited how the succeeding governments recognized there were, indeed, political prisoners, although human-rights abuses continue to hound the country.

Parong participated in seeking reparations from the Marcoses, who merely offered a “compromise settlement” of $150 million, while they were exiled in Hawaii. The negotiations failed because the Marcoses’ proposed settlement was considered to be a “mere donation” when the class suit involved nearly $2 billion.

In 2014, Parong, who had worked for Amnesty International, was appointed to the Human Rights Victims Claims Board by then President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino, which led to the indemnification of 11,103 martial law victims from the alleged P10 billion in ill-gotten wealth recovered in Swiss banks.

FORMER Rep. Jonathan dela Cruz concedes that people were already looking for a “new direction” amid the public outrage triggered by the 1983 Aquino assassination.

The snowballing protest movement was also compounded by the global economic crisis, its headwinds lashing the Philippine economy which contracted by 7.3 percent for two consecutive years starting 1984. Mr. Marcos’s critics blamed the economic nosedive on the country’s “deb-driven” growth, along with the mismanagement of “crony-monopolized” sectors.

Dela Cruz, then the country’s ambassador-at-large in the Middle East—the leading destination of overseas Filipino workers—said that while there was a continuing clamor for change, “there was also a continuing effort of the old oligarchy to get back at Marcos.”

These problems, he said, were compounded by the US factor, since Mr. Marcos “was trying to stir away from the handshake of the big powers like America.” He added, but did not elaborate, that the continuing US pressure from Congress and media which fueled articles against the regime “was a campaign started a long time ago by certain forces in the US.”

IN the meantime, Dela Cruz said Mr. Marcos was trying to get ahead with “liberalizing efforts” following years of martial law, which he lifted in 1981 while retaining many of his powers.

At the height of the Edsa revolution, Dela Cruz claimed that the majority in the armed forces actually remained loyal to the President “until the last minute.”

“So, if you are talking about crushing the anti-Marcos protests, he could have done it, but he decided to go into exile to prevent any bloodshed,” Dela Cruz added.

He admitted that a “big factor” in Marcos’ downfall was also the internal rift within the corridors of power. “Everybody knew that the President was sick. There were a lot of groups within the Marcos camp that was already struggling or competing for influence and power,” he said.

Despite the President’s ouster, Dela Cruz believes that Marcos can still be remembered for his vision of nation-building for the country “being more modernized and participatory” in development.

This partly explains the growing popularity of his son Bongbong, the consistent survey frontrunner among presidential aspirants in the May elections. The Marcos forces have also remained intact, including their political and economic forces.

Finally, he pointed to the sense that, for all the political and economic reforms of the past 35 years, people had “this failed expectation” from 1986 to the present.

“Our lives were never really uplifted. We essentially remain a divided country, with continuing corruption and human rights violations among other ills and problems,” he explained. “So, because of the demonization of the Marcos administration, people are now asking, ‘What really happened?’ People became curious. Kasi ang mga magulang nila, sabi ‘ayos naman kami noon [because their parents were saying, ‘we were fine then’].”

NOW retired Supreme Court Associate Justice Adolf Azcuna asserts that the gains at Edsa need not be taken for granted. With the restoration of democratic institutions lost during martial law, including regular elections, the people can now choose the leaders that they want, he stressed.

Even Bongbong Marcos, according to Azcuna, has benefited from the democratic institutions, now that he is guaranteed regular and free election, although “everything is really up to the people.”

“That’s what democracy means. If you want to choose certain candidates [who] have links with the previous dictator, that’s up to them,” he said.

Still, he stressed, people should not forget the principle of accountability, enshrined in the 1987 Constitution which he helped write as a member of the constitutional commission. That Charter affirmed that “public service is a public trust” and that “public officials must at all times be accountable to the people.”

Azcuna underscored the need to be vigilant 36 years after Edsa, noting the “possibility that we can lose it [democracy].”

“We should always remember that the guardrails of democracy are free speech, free media, political opposition, and regular and fair elections. Pag ’yan ay inalis o ginawang ineffective, mag-ingat tayo at mawawala yung tunay na demokrasya natin [if we remove or make those ineffective, we should be wary as we will lose genuine democracy],” said Azcuna.

“Now, do we want to go back to the past because it is the future that some of our people want? Go back to martial law, go back to controlling the economy, go back to arrests without warrants? Kill? If that is what they want, then so be it. This is a free country,” Azcuna said.

Meanwhile, on the campaign trail, it’s interesting that all presidential aspirants promise reforms and a better life. Bongbong Marcos pushes unity, saying the country will never progress if it keeps dividing itself between past and present. Isko Moreno offers himself as an alternative to the Marcos versus Aquino narrative as represented, he said, by Marcos Jr. and Vice President Leni Robredo. The Lacson-Sotto tandem promises to fix government so as to make better lives possible. The Pacquiao-Atienza duo offers similar hopes. Leody de Guzman and Walden Bello offer more radical reforms. All of them and the rest of the standard bearers—Ernesto Abella, Norberto Gonzales, Faisal Mangondatu and Jose Montemayor—promise to fight corruption. Yet if anything has survived in 35 years of reforms since Edsa, it’s corruption, morphing across regimes. It’s anyone’s guess whether the next regime change will spell real change.

* Veteran journalist Joel C. Paredes is a former director-general of the Philippine Information Agency (PIA) and holds an A.B. History degree from the University of the Philippines.

Related Topics

Red-tagged doctor detained in agusan sur – pnp.

- BusinessMirror

- February 19, 2022

Queen Elizabeth II tests positive for COVID; mild symptoms

- The Associated Press

‘Keys Muna’: Imminent hotel room shortage—and resulting higher room rates—could derail PHL’s ambition to lure more visitors

- Ma. Stella F. Arnaldo

- April 20, 2024

- Climate Change

Climate change to cause $38 trillion a year in damages by 2049, says PIK

- Laura Millan | Bloomberg

- International Relations

Oil erases advance after Iranian media downplays Israel’s attack

- Bloomberg News

- April 19, 2024

India delivers BrahMos supersonic missiles to PHL — report

- Malou Talosig-Bartolome

BOP surplus hits 14-month high in March–BSP

- Cai U. Ordinario

‘Manila, Washington must bolster defense interoperability’

- Rex Anthony Naval

Manila Water unit to acquire EHI shares

- Transportation

MMDA to conduct info campaign on e-bike, e-trike ban

- Claudeth Mocon-Ciriaco

Palawan-based Wescom to host ‘Balikatan’ drills

Harnessing Filipino talent for global businesses

Rhian Ramos, 30 other Filipinos stranded in Dubai as chaos mars airport

City of Sto. Tomas, Batangas Mayor starts the ball rolling for NJLA-LGU English Proficiency through Literature project

First lady says she and pbbm to focus on projects that will ‘outlive’ his term, admits falling out with vp sara.

Oil surges on concerns of escalating conflict in the Middle East

Stock market today (April 19, 2024): Asian markets sink, with Japan’s Nikkei down 3.5%, as Mideast tensions flare

- Zimo Zhong / The Associated Press

Iran releases Indian woman crew of MSC Aries

DMW: 3 Filipinos dead in UAE flooding

- Samuel Medenilla

China: We had ‘internal understanding’ with Marcos administration on managing Ayungin Shoal dispute

Geopolitics may hurt bid to tame inflation

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Reflecting on Edsa

In the history of every modern-day democracy, the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution stands out as the most astonishing, not only because it removed without bloodshed a cruel dictator in Ferdinand Marcos, but also because, all intents and purposes taken together, it has at least healed the malignancy of the Filipino nation’s broken soul.

But the wound of disunity threatens us again. Three decades later, Filipinos are still wanting in terms of the things they deserve from their own government. Edsa should have taught us how to elect the right persons for public office. But across the many regions of the country, we can only agonize in disbelief as we witness overlords in absolute control of our beloved land.

It is wrong, however, to put the blame on the ordinary Filipino. The majority did not benefit from Edsa. In fact, whole families still roam our busy streets, scavenging for soiled food. While towering edifices rise in the metropolis, thousands of children have remained hungry and without a home. As a society left behind by the modernity of the Western way of life, we can only indict our leaders, past and present, who exploited Edsa and abused its spirit and memory. Indeed, we have many cunning politicians who shamelessly invoke the concept of human welfare, or even the pursuit of happiness, in order to justify and brandish their particular style of tyranny.

History tells us that an autocrat who rules by means of some populist agenda is not impaired as to his knowledge of the timeless relevance of the principles of justice. But he distorts and uses the same in order to advance his vested interests. In the desire to destroy his enemies, a dictator only has one marching order to his docile and willing accomplices: to follow him without question. This type of loyalty is perhaps the most dangerous there is. It is the same kind of blind obedience that has caused honorable men to kill in the name of their god!

When President Corazon Aquino came to power in 1986, we believed then that it is not really intellectual brilliance but human virtue that legitimizes political leadership. And yet, in reality, it is the dictator who actually foregoes the advice of academics, as he will do things as he sees fit. He is so afraid of the wisdom of old. He fears engaging the titans of history. Edmund Burke elaborates: “What is the use of discussing a man’s abstract right to food or to medicine? … In this deliberation I shall always advise to call in the aid of the farmer and the physician, rather than the professor.”

Edsa gave the world a new way of looking at things. We stand firm that, as a people, we cannot allow those who hold positions of power to take advantage of us. Any form of violent counterrevolution can only mean that oppression has been maintained, although the oppressors may have changed the color of their skin. Burke says it well: “Kings, in one sense, are undoubtedly the servants of the people, because their power has no other rational end than that of the general welfare; but it is not true that they are, in the ordinary sense anything like servants.”

The raison d’être of Edsa is not Aquino or Marcos. Edsa is the story of the Filipino as a freedom-loving people. Burke appears precise: “A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation.”

It is every generation’s principal right to overthrow any ruthless despot. Freedom, ultimately, is an instrument for societal transformation. Unless we prevent ourselves from degenerating into a country that treats justice and the rights of people as some sort of a commodity that only the affluent can enjoy, the potent force of the radical change that was Edsa will continue to elude us.

Christopher Ryan Maboloc is assistant professor of philosophy at Ateneo de Davao University. He has a master’s degree in applied ethics from Linkoping University in Sweden. He was trained in democracy and governance at the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung in Bonn and Berlin, Germany.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Subscribe to our opinion columns

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

- Subscribe Now

The essence of EDSA: Change begins with us

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This was delivered at the Relevance of the 1986 EDSA People Power Today Forum, at the School of Economics Auditorium in UP Diliman on February 24, 2017.

It has been 31 years since our people took to the streets in peaceful revolt. I still remember those days. I was a shy and impressionable probinsiyana , and my time as a university student here at the School of Economics was of self-discovery and a growing awareness of the problems of our country. After all, one of UP’s many strengths is the way it exposes you to the realities of the world, of the social and political issues that shape those realities. In those final years of the Marcos dictatorship, all was not well. Resistance against Martial Law was gaining momentum. The people had awakened to the wholesale plunder and human rights abuses of the Marcos family, and they were ready to fight back. I had gotten a hold of a white paper written by our professors on our country’s economic troubles . It was a bold and fearless document, debunking the lies that the Marcoses had peddled on the state of our economy. You see, for a long time, Marcos maintained that the Philippine economy was in good shape. But the white paper showed us that this was far from the truth . Inflation had spiked to the double digits, and the prices of consumer goods were extremely high. Marcos borrowed huge sums domestically and overseas, but we found that the borrowings did not go to public infrastructure. Instead, the paper showed – factually and without doubt – that the funds were funneled away into the Marcoses’ ambitions of wealth, state control, and total power. As we know now, the assassination of Ninoy Aquino catalyzed the People Power Revolution. Enough was enough, the Filipino people said. For 3 days in February 1986, thousands of ordinary citizens peacefully marched to EDSA despite the risks: military tanks stood at attention and soldiers held their ready rifles, but they could not stop us. We wanted a government that would take care of the people, not destroy it. We wanted our freedoms restored under a democracy that was rightly ours. We wanted change, and we rose together to make that change possible.

Never forget Exactly 31 years since we got our freedom back, our fragile democracy has yet to get to its feet. We see the reemergence of Marcos heirs who today still try to convince our young that the sins of the past do not matter . They seek to revise our history using money stolen from the millions of tax payers wallets. From your parents’ savings meant for you.

Some leaders would like us to forget the atrocities of Martial Law. Some leaders are too happy to glorify the dictatorship of Marcos, to revise the history so that he is remembered a hero, and not the thief and murdered that he was. Some leaders want to raise the fist of authoritarianism, to sow fear and discord among ourselves, to divide us with lies, violence, and bloodshed. It has begun.

The brave senator In a surprise move, a warrant of arrest was issued against Senator Leila de Lima on Thursday, even after agreement has already been made for her to surrender herslf to the police on Friday morning. Was she to be taken under cover of darkness and to what end the rush, we do not know. The brave Senator who dared begin a probe into the President’s drug war prepared herself and said she will continue to fight . So on Friday, the nation woke up to a worrying scene; a senator and a staunch critic of the president was escorted into police custody. The message was loud and clear: anyone who dares speak dissent is not safe.

Our history as a nation is marred by instances where government officials use the processes of criminal justice to cow, silence, eliminate critics.

We cannot and we must not stand by and let this happen again. We must make sure that our government institutions remain uncorrupted and independent of each other, particularly when it comes to checks and balances in pursuit of accountability.

We believe that those who are accused of any crime must have their day in court, and have the right to a fair and unbiased trial. We exhort the people to follow and scrutinize this case religiously; fight for the right to speak dissent, which is the foundation of our strength as a free and democratic nation.

Change begins with us We hear the grumbling of some Filipinos. Democracy has failed because it hasn’t solved poverty. Is that really true? Or is it us who have failed democracy? Perhaps it is time for us to look at what we have contributed to democracy instead of the other way around. Perhaps it is us who need to remember the lives lost and the sacrifices made so that our society today will be free and enjoy the liberties we take for granted.

The real success of EDSA was that it proved the power of the people: that when our citizens come together in courage and in hope, we can be the change that we aspire for our country.

The strength of democracy, at its core, is the ability of each one of us to be part of nation-building. Do we keep our faith in our individual goodness, or should we opt to follow larger-than-life, self-proclaimed saviors, who promise to remove our suffering in 6 months?

No, we don’t need false prophets of change who claim that they are the people’s last hope. The change that we so desire begins with us – in the way we live our lives, in the way we protect the rights and liberties that EDSA restored, in the way we continue the unfinished work of the revolution.

Is it time to junk the 1987 Constitution and replace our system of government? We can’t and we must not. EDSA was exactly what we needed. Not just because its impact rang far beyond our shores. Not only because it conquered a greedy and brutal dictator. The real success of EDSA was that it proved the power of the people: that when our citizens come together in courage and in hope, we can be the change that we aspire for our country.

Therein lies the problem. After we reclaimed our democracy in 1986, our contributions ended. We started looking for saviors to save us again. We forgot that the Constitution and our democracy’s real foot soldiers are the people themselves. For us who are now in positions of leadership – whether as representatives of the Filipino youth, as politicians, or movers in civil society – the challenge of our time is to counter the cynicism that has marked public discourse. These days, what is dominant is the rhetoric of fear and doom. The public is made to believe that the Philippines is in complete dysfunction, and that only the most bloody measures can cure our country of its ills. We are made to believe that those who protest and oppose are traitors to the nation and its people.

Reject the lies As we celebrate the anniversary of the EDSA Revolution, we are called upon to reject these lies. Not all is lost in the Philippines. The People Power Revolution asks us to remember that there is cause for hope. I myself have seen these reasons – every day – in the work that I do. I see reason for hope in the men and women who continue to fight for justice and equality in this country. I see that reason for hope in the faces of even the poorest Filipinos, whose dreams for a better life persist despite the odds.

Mr President, we call you to task. In behalf of the Filipino people, whose daily struggles are escalating, we ask you to focus on the war that really matters: the war on poverty. Our people are hungry, jobless and poor.

Our country cannot afford to be derailed by political noise. While we bicker and fight, 95 children die of hunger every day. Our people need jobs to feed their family with nutritious food. Our farmers and fisherfolk need help in protecting their source of livelihood. More than 5 million families lack decent dwellings and are living in danger zones or deplorable conditions. Our business sector deserves a level playing field and lower costs and higher efficiency in doing business. Poverty is the real problem, but we are distracted by political agenda and division.

Please use your leadership to point the nation towards respect for rule of law, instead of disregard for it; to uphold the basic human rights enshrined in the institution, instead of encouraging its abuse. Be the leader you promised to be, and stop the lies that are distorting the truth in our society today. And to you each of you, the Filipino people, we all must defy these brazen incursions on our rights. We have fought so hard and so long for our freedoms. We have come so far since our country’s darkest days. Never forget that liberty rightfully belongs to our nation and its people. Never forget that together, we can make a stand for every Filipino who suffers injustice, for those who have been betrayed and neglected, and for those who continue to aspire for progress in our country. Never forget. Thank you very much, at mabuhay ang ating demokrasya! – Rappler.com

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}.

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

travel and street photographer

Documentaries About the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution in the Philippines

On the 25th of February each year, the Philippines marks the anniversary of the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution . This momentous occasion represents the restoration of democracy in the Philippines after the dark period of the Marcos Regime.

Although many Millennials and Gen Zs were not yet born during this historic event, it remains relevant to this day. As responsible citizens, it is crucial for all Filipinos to understand the significance of what took place during that time and how it continues to impact our country today. Let us take the time to educate ourselves about this crucial moment in our history and reflect on how we can make sense of it in the present.

But before that, here is a music video of the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution in the Philippines by Virna Lisa:

The 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution in the Philippines Theme Song: Magkaisa

“Magkaisa” is a Filipino song composed by National Artist for Music Ryan Cayabyab with lyrics by Jose Javier Reyes. It was first performed by the popular singer and actress Virna Lisa during the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution, which saw the overthrow of the Marcos regime in the Philippines.

The song’s title “Magkaisa” means “unite” in English, and it is a call for the Filipino people to come together as one and work towards a common goal. The lyrics convey a message of hope and unity, emphasizing the importance of standing together and supporting each other through difficult times.

With its uplifting melody and powerful lyrics, “Magkaisa” quickly became an anthem for the Filipino people during the EDSA Revolution and continues to be a symbol of hope and unity for the country. It is often performed during patriotic events and has become an enduring part of Filipino culture.

As someone who is passionate about documentaries, I have curated a selection of seven insightful films that delve into the intricacies of the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution . These documentaries, which I discovered online, offer a wealth of information and perspectives on this historic event.

EDSA 20 ‘ISANG LARAWAN’ (2016)

This informative 50-minute documentary was brought to you by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, a prominent national newspaper network in the Philippines.

According to the description provided on YouTube, this documentary was specially produced in 2006 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the EDSA People Power Revolution . The documentary features fresh perspectives from voices that were previously unheard of, offering unique insights into this historic event.

EDSA 30 (2016)

This 20-minute documentary serves as a continuation of Inquirer.Net’s previous EDSA 20 documentary.

COUP D’ETAT: THE PHILIPPINES REVOLT 1986 (2017)

This documentary, spanning an hour in length, was brought to life by an Australian television network. It offers a vivid depiction of the four-day nonviolent military uprising that led to the removal of President Ferdinand Marcos from power in the Philippines. Through insightful narration, the documentary sheds light on the people who participated in the revolution, and the reasons behind its ultimate success. Its valuable commentary helps to provide a comprehensive understanding of this significant event in Philippine history.

1986 PEOPLE POWER EDSA HISTORY (2013)

In 2013, the Philippine Department of National Defense created a concise 25-minute documentary.

BIYAHENG EDSA (2006)

This half-hour documentary was created by GMA News and Public Affairs, a prominent national TV network based in the Philippines. The program follows broadcast journalist Howie Severino as he journeys along Epifanio delos Santos Avenue, commonly referred to as EDSA, to delve into the transformations that have taken place in the Philippines over the two decades since the People Power Revolution. Originally aired in February 2006, this compelling documentary is being re-shared online in anticipation of the upcoming 25th Anniversary of People Power , taking place from February 21 to 25, 2011.

BATAS MILITAR (1997)

The Foundation for Worldwide People Power (FWWPP) produced a 2-hour documentary that sheds light on one of the darkest moments in Philippine history. This acclaimed film covers the period when the entire nation endured the ruthless oppression of the Marcos authoritarian regime. The FWWPP, which also produced the widely praised “Beyond Conspiracy: 25 Years after the Aquino Assassination,” presents this compelling documentary to give a voice to those who suffered under the oppressive regime.

In conclusion, the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution in the Philippines remains an important and significant event in the country’s history. Despite the fact that many of today’s Millennials and Gen Zs were not yet born during this time, it still holds relevance to the present day. As responsible citizens, it is our duty to educate ourselves on this pivotal moment in our history and to reflect on how it continues to impact our society today. By doing so, we can unite as a nation and work towards a brighter future that upholds the values of democracy and unity. Let us remember and honor the bravery of those who fought for our freedoms during the EDSA Revolution, and strive towards building a better Philippines for generations to come.

4 thoughts on “Documentaries About the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution in the Philippines”

I am lucky to have witnessed the EDSA revolution when I was on my second year high school in Tondo. Though I am not physically present, the feelings are intense that time. I remember those videos and photos. Thank you for comemorating that special event.

I was with the UP Manila contingent in EDSA at that time. I don’t remember, which day it was. I remember there was no tension so we were able to sleep, but the nice thing then was we woke up to the sound of Walk of Life by the Dire Straits, a blues-rock song with a good-vibe riff for an intro. It must have been 5 or 6 in the morning. The sun was already up and I saw Prof. Randy David nearby sweeping to keep the area clean. We were better than those in Woodstock in that regard

I was with the UP Manila contingent in EDSA at that time. I don’t remember, which day it was. I remember there was no tension so we were able to sleep, but the nice thing then was we woke up to the sound of Walk of Life by the Dire Straits, a blues-rock song with a good-vibe riff for an intro. It must have been 5 or 6 in the morning. The sun was already up and I saw Prof. Randy David nearby sweeping to keep the area clean. We were better than those in Woodstock in that regard

February 1986, I was 15 turning 16 years old, a graduating HS student of Rizal High School Pasig. It was a mixed emotion, sad and worried because graduation rites might be postponed or cancelled. Our family was listening to Radio Veritas, I personally and actually heard all the happenings in EDSA. Those documentaries are legit. I salute to all the people who responded for their bravery and courage. At home, we joined by praying the rosary, with the intention to… bless all the people in EDSA, to justice be revived. Praying that no one will be hurt and die. Being a Legion of Mary, I tearfully prayed that Mama Mary will intercede to end the injustice and corruption of Marcos government. I hope that our Filipino youth will not be corrupted by false narratives of the Marcos funded fake historians to distort this momentous historical event that made every Filipino proud. The bloodless revolution that overthrown a corrupt dictator.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

EDSA People Power Revolution. The Philippines was praised worldwide in 1986, when the so-called bloodless revolution erupted, called EDSA People Power's Revolution. February 25, 1986 marked a significant national event that has been engraved in the hearts and minds of every Filipino. This part of Philippine history gives us a strong sense of ...

From February 22 to 25, 1986, hundreds of thousands of Filipinos gathered on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue to protest President Ferdinand Marcos and his claim that he had won re-election over Corazon Aquino. Soon, Marcos and his family were forced to abdicate power and leave the Philippines. Many were optimistic that the Philippines, finally ...

The EDSA Revolution Anniversary is a special public holiday in the Philippines. Since 2002, the holiday has been declared a special non-working holiday. ... "From the ashes: The rebirth of the Philippine revolution—a review essay." Third World Quarterly 8.1 (1986): 258-276. online; Crisostomo, Isabelo T. (1987). Cory: Profile of a President.

Joel C. Paredes. February 20, 2022. 11 minute read. The People Power Monument gets cleaned in preparation for the 36th anniversary of the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution, the bloodless revolt ...

2016 marks the 30th anniversary of the People Power Revolution. During those momentous four days of February 1986, millions of Filipinos, along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) in Metro Manila, and in cities all over the country, showed exemplary courage and stood against, and peacefully overthrew, the dictatorial regime of President Ferdinand E. Marcos.

12:24 AM February 27, 2017. In the history of every modern-day democracy, the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution stands out as the most astonishing, not only because it removed without bloodshed a cruel dictator in Ferdinand Marcos, but also because, all intents and purposes taken together, it has at least healed the malignancy of the Filipino ...

The Edsa Revolution. The Philippines was praised worldwide in 1986, when the so-called bloodless revolution erupted, called EDSA People Power's Revolution. February 25, 1986 marked a significant national event that has been engraved in the hearts and minds of every Filipino. This part of Philippine history gives us a strong sense of pride ...

Basahin sa Filipino [This essay was originally published on this website to commemorate the 27th anniversary of EDSA, February 25, 2013]This year marks the 27th anniversary of the 1986 People Power Revolution. During these momentous four days in February, Filipinos showed exemplary courage and stood united against a dictator.

The 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution was a successful social movement in the Philippines that overthrew the regime of President Ferdinand E. Marcos who had oppressively been in power for 20 years. Towards the end of his last term, President Marcos declared Martial Law in late 1972 because there were groups of students and militants who had ...

To start EDSA revolution essay: 'Media is a tool of communication which comes from different sources such as tabloid, magazines, television, cellphones, etc.' It is where we get information regarding the current issues in the society. Talking about history, in the Philippines in particular, there are many instances wherein media is used in the ...

The great success of the EDSA bloodless revolution by nonviolent, passive resistance and the accession to the presidency of Corazon C. Aquino was that it was a mass movement and relatively bloodless. It was a protest movement against the dictatorship showing that huge numbers can change the political status quo. The middle class was motivated ...

Feb 25, 2021 5:03 PM PHT. John Sitchon. Cebuano writer Emmanuel Mongaya brings us back to the core of activism in the days of EDSA 1. Decades after ousting a dictatorship, civil resistance and ...

The EDSA Revolution is a testament to ordinary people's power to effect extraordinary change through nonviolent means. A moment of unity, courage, and resilience ended a dictatorship and inspired similar movements for democracy worldwide. The revolution's legacy in the Philippines reminds us of the importance of democracy, good governance ...

That monumental event changed the course of the Philippine's history forever. Today, the 36-year-old EDSA People Power Revolution is still greatly admired and respected by global leaders for giving that spark of hope and pride that a successful revolution does not need bloodshed. Instead, it is the spirit of the people and their love for the ...

Feb 25, 2017 8:00 AM PHT. Vice President Leni Robredo. We don't need false prophets of change who claim that they are the people's last hope. The change that we so desire begins with us. This was ...

PDF | On Jan 1, 2013, R. Curaming and others published (Re)Assessing the EDSA "people power" (1986) as a critical conjuncture | Find, read and cite all the research you need on ResearchGate

The 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution made a very significant mark in the Philippine history. It was a four-day series of a peaceful rally against the Presidency of Ferdinand Marcos. This rally brought down Marcos from Malacanang and was then by replaced by Corazon Aquino. The revolution lasted for four days, from February 22 to 25, 1986.

Essay About Edsa Revolution. 941 Words4 Pages. The deliverance of Israelites from slavery in Egypt started when Moses was born. When the pharaoh ordered the killing of the male babies, God saved Moses' life through his mother. Moses' mother put him in a basket when he was a baby; a princess found him and adopted him.

Watch on. "Magkaisa" is a Filipino song composed by National Artist for Music Ryan Cayabyab with lyrics by Jose Javier Reyes. It was first performed by the popular singer and actress Virna Lisa during the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution, which saw the overthrow of the Marcos regime in the Philippines. The song's title "Magkaisa ...

The revolution is also known as the Peaceful Revolution because there was no bloodshed. Prayer was the only weapon. On February 25 1986, the Filipino people marched Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) in the People Power Revolution. The revolt came from President Marcos not treating his people properly.

Research paper, Pages 7 (1523 words) Views. 13818. The Philippines was praised worldwide in 1986, when the so-called bloodless revolution erupted, called EDSA People Power's Revolution. February 25, 1986 marked a significant national event that has been engraved in the hearts and minds of every Filipino. This part of Philippine history gives ...

EDSA. The People Power Revolution (also known as the EDSA Revolution, the Philippine Revolution of 1986, and the Yellow Revolution) was a series of popular demonstrations in the Philippines that began in 1983 and culminated in 1986. The methods used amounted to a sustained campaign of civil resistance against regime violence and electoral fraud.

Order custom essay Impact of EDSA Revolution with free plagiarism report 450+ experts on 30 subjects Starting from 3 hours delivery Get Essay Help. EDSA Revolution. I was able to get my mother's side of the story on what happened during the EDSA Revolution. I started to ask where she was during the EDSA Revolution (Febrauary 22-25) and said ...