An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Acta Biomed

- v.93(3); 2022

Factors associated with eating disorders in adolescents: a systematic review

Candy laurine suarez-albor.

1 Faculty of Nursing, Universidad Popular del Cesar, Valledupar, Colombia

Maura Galletta

2 Department of Medical Sciences and Public Health, University of Cagliari, Monserrato, Italy

Edna Margarita Gómez-Bustamante

3 Faculty of Nursing, University of Cartagena, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia

Background and aim:

The World Health Organization has placed eating disorders among the priority mental illnesses for children and adolescents given the risk they imply for their health. Recognizing the risk factors associated with this problem can serve as the basis for the design of timely and effective interventions. The objective of the study was to identify the factors associated with eating behavior in adolescents through a systematic review.

Systematic review. Search of the literature in the bibliographic sources CINAHL, CUIDEN, Pubmed, Dialnet, SCIELO and Science Direct. The search was conducted in October and November 2020. The search terms were Eating Disorders, Food Intake, and Adolescents. The evaluation of the methodological quality was carried out using a specific guide for observational epidemiological studies. A narrative synthesis of the findings was made. Additionally, the vote counting and sign test technique was applied.

25 studies were selected. The associated factors were body dissatisfaction, female gender, depression, low self-esteem, higher BMI that increases the risk of eating disorders.

Conclusions:

a high impact of psychological factors was observed. These should be considered in the design of effective interventions to prevent this disease, although the search needs to be broadened to identify larger and more complex studies that allow for a more comprehensive review. ( www.actabiomedica.it )

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are complex and multifactorial pathologies that affect physical and mental health and are life threatening. They are characterized by an excessive preoccupation with the weight and shape of the body or a frank deviation of the body image, accompanied by voluntary restriction of the intake or the presence of episodes of binge eating that cause great suffering, impairment of health and quality of life ( 1 ). The prevalence of eating disorders is variable; in the last two decades several studies have been carried out, especially by the National Institute of Mental Health of the United States, which has compiled cases even from European countries. The countries with the highest cases are Switzerland 12%, Chile 8.3% and Spain 6.2% ( 2 ); Colombia is followed by 4.5% ( 3 ), the United Kingdom 3.7% ( 2 ) and Portugal 3.06% ( 2 ). Countries such as the United States, Italy, Costa Rica, Mexico, Honduras, Venezuela, have numbers between 0.5% -1.5% ( 4 , 5 ). Most of these disorders are more common in women and begin in adolescence, a stage of change where body image is consolidated. This in turn generates numerous crises of identity, physical appearance, friendly or sexual requirements and a struggle for autonomy, traits of perfectionism and self-demand that can lead to low self-esteem, dependence on the environment, difficulty in expressing emotions or expressing aggressiveness ( 6 , 7 ).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has placed eating disorders among the priority mental illnesses for children and adolescents given the risk they imply for their health and the great psychiatric comorbidity ( 8 ). Among the most frequent, depressive disorders 23.3%, anxiety disorders 10%, adaptive disorders 3.3% and negative perception of family relationships 43.3%, which aggravate the problem and cause important complications in the state of health ( 7 , 9 ). For this reason, EDs have become more relevant for the interest in the clinic, research and epidemiology ( 9 ). Various factors intervene in the occurrence of eating disorders and show a higher attributable risk such as biological, psychological, family and sociocultural ( 2 - 7 ). Thus, scientific evidence is abundant when addressing various aspects of eating disorders, however the state of the art revealed that in the last five years no literature review have been published on the subject, which is relevant to design or guide effective interventions that allow professionals to prevent these events. In this sense, the aim of this work was to carry out an exhaustive review of the published evidence about the factors associated with eating behaviour in adolescents.

A systematic review was carried out according to the guidelines of the PRISMA ( 10 ) statement, in the bibliographic sources LILACS, CUIDEN, Pubmed, Dialnet, SCIELO and Science Direct and MEDES. The search was carried out in October and November 2020. The search terms to be used were consulted in the DECS and MESH libraries, to guarantee their standardization, in English and Spanish, they were conjugated in search equations with the Boolean operators AND and OR thus: AND factors (Eating Disorders OR Food Intake OR Eating Behavior) AND adolescent.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were selected from cohort, cross-sectional, and case control studies about factors associated with EDs in adolescents. The inclusion criteria were (a) free access articles in full text, (b) primary studies published between 2009 and 2020 to ensure that as many necessary and relevant studies as possible have been included in the review, (c) studies with a sample of adolescents aged from 10 to 19 years, according to the classification provided by the WHO ( 9 ). Dissertation, meta-analysis, review, experimental, intervention, or treatment studies were excluded, as well as studies with a mixed sample (children, adolescents, adults), and investigations without statistical information of association.

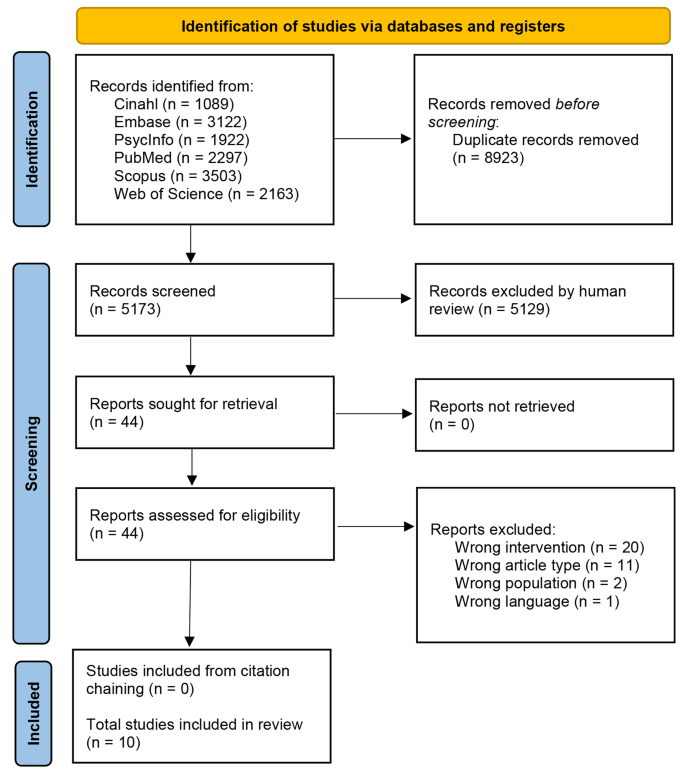

Article selection and evaluation of methodological quality

The selection of the articles was carried out in 4 phases. First, title and abstract were read to determine the suitability of the study and elimination of duplicates. Second, full text was read and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Third, a reverse and forward search was performed on the included studies to locate as many documents as possible. Fourth, the risk of bias was assessed through critical reading based on the Critical Reading Guide for Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( 11 , 12 ). A guide to assess cross-sectional studies was used ( 11 ). This instrument included 31 items that allow for minimizing biases and the confounding effect of internal validity. It was evaluated qualitatively using MB: very good, B: good, A: regular, and NI: does not report. A second guide was used to assess cohort studies and case-control studies ( 12 ). The instrument included 21 items and evaluated qualitatively the followings aspects: selection of subjects, validation of question, evaluation of the final outcomes, confounding factors, statistical analysis, general evaluation of the study, and description of the study, using A: adequately, B: partially, C: improperly, and D: I don’t know. This process was carried out by the first author and was audited by the other authors.

Data extraction

The data were consolidated through a structured booklet in Excel based on two types of information: (i) information about articles’ characteristics such as study sample, main author, year of publication, language, country, design; (ii) information about eating disorder risk factors such as biological, psychological, sociocultural, and family factors.

Data analysis

The information was treated qualitatively and analysed in a narrative way. The results were organized in tables and figures according to the PRISMA statement. Additionally, the found results exceeded the number of 20 articles, so the vote counting technique was applied. Such a technique consisted in granting a positive vote for studies with a statistically significant relationship between a risk factor and EDs, and a negative vote when there was no significant association. Subsequently, the sign test ( 13 , 14 ) was applied to determine if the difference in the number of positive studies was significantly greater than the opposite result. A significance value was established to be less than 0.05. It is important to notice that these techniques are limited but they can help to guide the results of the review in the absence of meta-analysis ( 14 ).

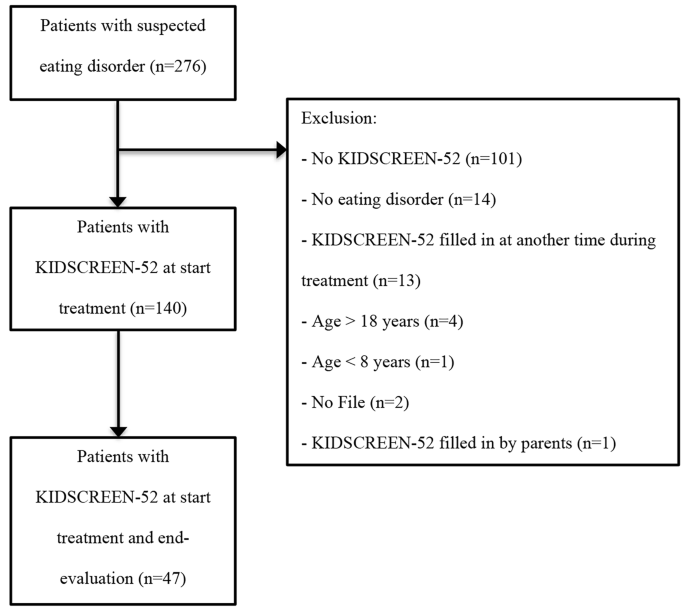

General diagram of the study

Methodological quality assessment

About the cross-sectional studies, 54.5% (n = 12) obtained high methodological quality, 27.2% (n = 7) medium quality, and 4.6% (n = 1) low methodological quality. This study was excluded by the revision. With regard to the cohort studies, it was assumed that studies with adequate rating in 23-26 items were considered to be of high methodological level; medium level was attributed to studies with adequate rating in 19-22 items, and low methodological level was attributed to studies with adequate rating in 18 items or less. In this sense, 100% (n = 3) of the cohort studies obtained a medium methodological quality ( Tab. 1 and Tab. 2 ).

Critical reading and assessment of methodological quality for cross-sectional studies.

Note . Internal validity. It defines whether the study design allows minimizing biases and the confounding effect ( 12 ).

The Items used were:

2. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of participants are indicated, as well as the sources and selection methods.

3. The selection criteria are adequate to answer the question or the objective of the study.

4. The study population, defined by the selection criteria, contains an adequate spectrum of the population of interest.

5. An estimate was made of the size, the level of confidence or the statistical power of the sample to estimate the measures of frequency or association that the study intended to obtain.

6. The number of potentially eligible people is reported, those initially selected, those who accept and those who finally participate or respond; fifteen. Statistical analysis was determined from the beginning of the study.

16. The statistical tests used are specified and appropriate

17. Participant losses, lost data or others were correctly treated

18. The main possible confounding elements were taken into account in the design and in the analysis.

Assessment: MB=very good; B=good; R=regular; NA=not applicable; NI=no information.

Critical reading and assessment of methodological quality for cohort studies.

Note . Cohort studies allow a direct determination of relative risk and allow calculation of the interval between exposure or risk factor and overall study disease ( 12 ). It was scored according to the validity of the question, selection of subjects, evaluation, confounding factors, statistical analysis, general assessment and description of the study. Rating: according to the author, the items were rated as follows: A: adequately; B: partially; C: improperly; D: I don’t know. For the purposes of this review, it was assumed that studies with adequate rating in 23-26 items were considered to be of high methodological level; medium level was attributed to studies with adequate rating in 19-22 items, and low methodological level was attributed to studies with adequate rating in 18 items or less.

Characteristics of the studies

Among the selected studies, 86.4% (n = 19) were cross-sectional design (15─33), 13.6% (n = 3) were cohort studies (34─36). Fifty-percent (n = 11) of the studies were conducted in Latin America (18, 20─22, 24─27, 31─33), 31.8% (n = 7) in Europe (15, 19, 23, 29, 30, 33, 34), 9% (n = 2) in Asia ( 16 , 34 ) 4.6% (n = 1) in Africa ( 17 ), and 4,6% (n = 1) in North America ( 28 ) ( Tab. 3 ).

Synthesis of the studies included in the review.

Factors associated with eating disorders

Different instruments were used to measure the factors associated with eating disorders. In 14.2% (n = 7) of the analysed studies, authors used the Eating Attitude Test (EAT-26) ( 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 25 , 30 , 31 ), 11% (n = 5) the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) ( 21 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 31 ), and 9.5% (n = 4) the Sociocultural Attitudes Questionnaire towards appearance-3 (SATAQ-3) ( 20 , 28 , 32 , 36 ). About 93% (n = 14) of the studies analysed risk factors and about 7% (n = 1) analysed correct self-image and hours of practiced sport as protective factors (B = 0.11; p = 0.047) ( 30 ). Regarding the risk factors, psychological risks were the most frequently analysed by the studies (71%). They included dissatisfaction with body image, low self-esteem, high depression, high perfectionism, stress, impulsivity, personal and interpersonal insecurity, emotional dysregulation, and ineffectiveness. About 14% of the studies analysed sociocultural factors such as alcohol use-related problematics, internalization of the thinness ideal, influence of media, ridicule related to weight, and being an immigrant adolescent. Also, 7.1% of the studies analysed family factors such as authoritarian family style, family functioning, poor communication, and family care. Lastly, 7.1% of the studies analysed biological factors such as being female. The complete description of the factors is summarized in Tab. 3 .

Analysis of vote counting and sign test

It was found that there was a greater number of studies that reported statistically significant relationships between factors such as body dissatisfaction, female gender, depression, low self-esteem, and higher body mass index (BMI) with eating disorders ( Tab. 4 ). In this sense, adolescents with those risk factors are more likely developing eating disorders.

Analysis by vote counting and sign test.

In the present review, the results show that the main factors associated with eating disorders were psychological-type with a prevalence of the factor inherent the dissatisfaction with body image ( 16 ─ 18 , 21 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 35 ). Literature refers that dissatisfaction with body image increases significantly in adolescence due to environmental pressures like media (e.g., television, social networks, virtual and written press) ( 20 , 28 ). They represent channels of transmission of the current body aesthetic model and have a positive or negative impact on an adolescent’s body image. This is more common in women, as it was the biological factor reported in this review. However, the findings are consistent with other studies where dissatisfaction with body image occurs more frequently in females and is positively associated with BMI as a predictor of eating disorders. ( 37 , 38 ). Similarly, BMI appears directly related to dissatisfaction with one’s own body, namely the higher the BMI, the higher the body dissatisfaction ( 25 , 31 ─ 33 , 36 ). This association is more recurrent in female gender ( 17 , 22 , 26 , 28 , 30 ) as girls generally show greater instability of self-image, lower self-esteem and general dissatisfaction with their body, if compared to boys. In most studies, the sample studied was female ( 29 , 33 , 34 , 36 ). Other psychological factors were emerged from the review. They were: appearance orientation ( 28 ), high level of perfectionism ( 23 , 29 ), low self-esteem ( 18 , 29 , 33 , 34 , 36 ), impulsivity ( 22 ), stress, suicidal idea and depression ( 22 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 34 ), eat in the absence of hunger ( 28 ), concern about being overweight, submission ( 24 ), personal and interpersonal insecurity ( 29 , 36 ), and emotional dysregulation ( 33 ). A teenager with low self-esteem shows a negative attitude and evaluation towards himself. In fact, low self-esteem has been repeatedly considered as a relevant factor of vulnerability for the development of EDs. This evidence is supported by a previous review ( 39 ). It is also important to identify depressive and anxiety manifestations that have an impact on food restriction and concerns about figure and weight. The number of studies that supported the relationship between psychological factors and eating disorders was statistically significant according to the sign test.

Socio-cultural factors were analysed in 14.2% of the selected studies ( 15 , 16 , 20 , 24 , 26 , 32 , 36 ). The most frequently revealed were the internalization of the thin ideal followed by the influence of media, weight-related bullying , and immigrant adolescents. These sociocultural factors and the desire to conform to body aesthetic models promoted by media and advertising have a greater likelihood to developing perceptions of body dissatisfaction. Moreno ( 40 ) showed a very high relationship between the influence of the media and the presence of eating disorders in the adolescent population. This is a cultural problem that comes from long ago where the idea that a perfect body is thin and that this it is accepted by society. The media are very important agents in the transmission of messages about the desire for thinness that is constantly present in eating disorders; the media channel social pressure to be thin is obviously stronger on females than males ( 40 ).

A few studies analysed the relationship between family factors and eating disorders ( 19 , 21 , 34 ). However, family functioning, poor communication, family care, and authoritarian styles are factors described in the literature as predisposing to eating disorders by impacting the way adolescents worry about the amount of calories in food and obsessed with food and weight gain. In this sense, parents can play a protective role, but they can also represent a risk factor for their children’s eating behaviour, as adolescents regulate their behaviour according to their parental model from early childhood ( 40 , 41 ).

In this review, we found only one research that addressed protective factors related to physical exercise and correct ideas about body image. This could be due to the fact that research in the last two decades has focused on mitigating or controlling risk factors as the sole basis for interventions to prevent eating disorders in adolescents. However, protective factors make adolescents less vulnerable to the development of eating disorders and facilitate the achievement of physical and mental health, the quality of life of adolescents, the development of healthy habits and social welfare. Protective factors are susceptible to being modified and intensified and do not necessarily occur spontaneously or at random. In this sense, interventions focused on strengthening those factors could be effective to prevent eating disorders behaviours. This requires the development of research that identifies and analyses the protective factors that can be strengthened in adolescents ( 42 ─ 44 ).

Most of the studies included in this systematic review are cross-sectional and in a lower percentage are cohort studies. Spain is the country that has done the most research on the factors associated with eating disorders in adolescents, thus showing a particular interest in this topic. However, this review has shown that there is a plurality of studies in the scientific community from different sociocultural contexts. This can explain why there is variability of risk factors for eating behaviour, although body dissatisfaction is the most common factor emerged from the revision.

The limitations of the review reflect the heterogeneity of the study that does not allow to carry out a meta-analysis and statistic associations between factors. Although the vote count and the sign test allow giving an additional value to the narrative synthesis of the results, they are limited procedures to establish reliable statistical associations with data. In this sense, reviews around the subject with quantitative analysis procedures would be necessary.

Conclusions

Psychological factors were found to be the main risk factors directly related to eating disorders in adolescents. The most common were: dissatisfaction with body image, depression, low self-esteem and higher BMI. Being a woman was also identified as the most reported biological factor associated with eating disorders. These risk factors become relevant when guiding the creation of mental health promotion programs for adolescents and the prevention and early detection of the eating disorders in adolescents.

Conflict of Interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Eating disorders: A problem that goes beyond food. 2018 [ Google Scholar ]

- Sánchez A. Prevalence of eating disorders in six European countries. Metas Enferm. 2017 Jun; 20 (5):66–73. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.35667/MetasEnf.2019.20.1003081094. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fajardo E, Méndez C, Jauregui A. Prevalence of risk of eating disorders in a population of secondary school students, Bogotá Colombia. Revista Med. 2017; 25 (1):46–57. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.18359/rmed.2917. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smink F, Daphne V, Hans H. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders; Incidence, prevalence and Mortality Rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012; 14 :406–14. doi: 10.1007 / s11920-012-0282-y. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Medina M, et al. In: The Mental Health Survey in Adolescents in Mexico. Epidemiology of mental disorders in Latin America and the Caribbean. Rodríguez J, Kohn R, Aguilar S, editors. Washington: Pan American Health Organization; 2009. pp. 107–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ortiz Cuquejo LM, Aguiar C, Samudio Domínguez GC, et al. Eating disorders in adolescents: a growing pathology? Pediatr (Asunción) 2017 Apr; 44 (1):37–42. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.18004/ped.2017.abril.37-42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaete P V, López C C. Eating disorders in adolescents. A comprehensive approach. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2020 Oct; 91 (5):784–93. Spanish. doi: 10.32641/rchped.vi91i5.1534. PMID: 33399645. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization. Mental health in adolescents. 2020 [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Adolescent Development. 2019 [ Google Scholar ]

- Urrutia G, Bonfill X. PRISMA statement: a proposal to improve the publication for systematic reviews and meta-analyzes: Rev. Medicina Clínica. 2010; 1 :507–511. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ciapponi A. Guide to critical reading of observational studies in epidemiology (first part)] Evid Actual Práct Ambul. 2010 Oct-Dec; 13 (1):135–40. Spanish. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ciapponi A. Critical reading guide of observational studies in epidemiology (second part) Evid Actual Práct Ambul. 2011 Mar; 14 :7–14. Spanish. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pino R, Frías A, Palomino P. The quantitative systematic review in nursing. RIDEC. 2014 Jan; 7 :24–40. Spanish. [ Google Scholar ]

- Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011 [ Google Scholar ]

- Esteban L, Veiga O, Gómez S, et al. Length of residence and risk of eating disorders in immigrant adolescents living in madrid. The AFINOS study. Nutr Hosp. 2014; 29 (5):1047–53. doi: 10.3305/nh.2014.29.5.7387. PMID: 24951984. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shahyad S, Pakdaman S, Shokri O, et al. The Role of Individual and Social Variables in Predicting Body Dissatisfaction and Eating Disorder Symptoms among Iranian Adolescent Girls: An Expanding of the Tripartite Influence Mode. Eur J Transl Myol. 2018; 28 (1):72–7. doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2018.7277. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yirga B, Assefa Y, Derso T, et al. Disordered eating attitude and associated factors among high school adolescents aged 12-19 years in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2016; 9 (1):503. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2318-6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Altamirano Martínez MB, Vizmanos Lamotte B, Unikel Santoncini C. Continuum of risky eating behaviors in Mexican adolescents. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2011 Nov; 30 (5):401–7. Spanish. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892011001100001. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuentes MC, García O. Influence of family socialization on satisfaction with body image in Spanish adolescents. Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria. 2015; 22 :2403–25. Spanish. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lazo Y, Quenaya A, Tristán P. Mass media influence and risk of developing eating disorders in female students from Lima, Peru. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2015; 113 (6):519–525. Spanish. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Londoño-Pérez C, Moreno Ruge AM. Family and personal predictors of eating disorders in young people. Anal Psicol. 2017; 33 (2):235–42. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.2.236781. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nuño-Gutiérrez BL, Celis-de la Rosa A, Unikel-Santoncini C. Prevalence and associated factors related to disordered eating in student adolescents of Guadalajara across sex. Rev Invest Clin. 2009; 61 (4):286–93. Spanish. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pamies L, Quiles Y. Perfectionism and risk factors for the development of eating disorders in Spanish adolescents of both genders. Anal Psicol. 2014; 30 (2):620–26. Spanish. https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.2.158441. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silva C, Millán B, González K. Gender role and eating attitudes in adolescents from two different socio-cultural contexts: Traditional vs. non-traditional. Rev Mex de Trastor Aliment. 2017; 8 (1):40–8. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmta.2016.12.002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fortes Lde S, Cipriani FM, Ferreira ME. Risk behaviors for eating disorder: factors associated in adolescent students. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2013; 35 (4):279–86. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2012-0055. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cogollo Z, Gómez E. Risk of eating behavior disorders in adolescents from Cartagena, Colombia. Invest Educ Enferm. 2013; 31 (3):450–6. Spanish. [ Google Scholar ]

- Caldera I, Martin P, Caldera J, et al. Predictors of risk eating behaviors in high school students. Rev Mex Trastor Aliment. 2019; 10 (1):22–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/fesi.20071523e.2019.1.519. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reina SA, Shomaker LB, Mooreville M, et al. Sociocultural pressures and adolescent eating in the absence of hunger. Body Image. 2013; 10 (2):182–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.12.004. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Laporta I, Delgado M, Reboyar S, et al. Perfectionism in adolescents with eating disorders. Eur J Health Research. 2020; 6 :97–107. Spanish. doi: 10.30552/ejhr.v6i1.205. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rod E, Pons R, Lajara F, et al. Influence of the habits of the adolescent population on self-image and the risk of eating disorder. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2011; 13 (51):387–96. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Sousa L, De Sousa S, Caputo E. Influence of psychological, anthropometric and sociodemographic factors on the symptoms of eating disorders in young athletes. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto) 2014; 24 :21–7. Spanish. doi: 10.1590/1982-43272457201404. [ Google Scholar ]

- Castaño J, Giraldo D, Guevara J, et al. Prevalence of risk of eating disorders in a female population of high school students, Manizales, Colombia, 2011. Rev. Colomb. Obstet. Ginecol. 2012; 63 (1):46–56. Spanish. doi: https://doi.org/10.18597/rcog.202. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rutsztein G, Scappatura L, Murawski B. Perfectionism and low self-esteem across the continuum of eating disorders in adolescent girls from Buenos Aires. Rev Mex Trastor Aliment. 2014; 5 (1):39–49. Spanish. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2007-1523(14)70375-1. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haynos AF, Watts AW, Loth KA, et al. Factors Predicting an Escalation of Restrictive Eating During Adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2016; 59 (4):391–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.011. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maezono J, Hamada S, Sillanmäki L, et al. Cross-cultural, population-based study on adolescent body image and eating distress in Japan and Finland. Scand J Psychol. 2019; 60 (1):67–76. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12485. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Batista M, Žigić Antić L, Žaja O, et al. Predictors of eating disorder risk in anorexia nervosa adolescents. Acta Clin Croat. 2018; 57 (3):399–410. doi: 10.20471/acc.2018.57.03.01. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jiménez Flores P, Jiménez Cruz A, Bacardi Gascón M. Body-image dissatisfaction in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Nutr Hosp. 2017; 34 (2):479–89. Spanish. doi: 10.20960/nh.455. PMID: 28421808. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mancilla A, Vásquez R, Mantilla J, et al. Body dissatisfaction in children and preadolescents: A systematic review. Rev Mex Trastor Aliment. 2012; 3 (1):62–79. Spanish. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Outcomes of eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2007; 40 (4):293–309. doi: 10.1002/eat.20369. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moreno J, Torres C. Revisión sistemática de los determinantes socioculturales asociados a los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en adolescentes latinoamericanos entre 2004 y 2014. Bogotá: UCA publication; University Applied and Environmental Sciences. 2015 [ Google Scholar ]

- Ruíz A, Vázquez R, Mancilla J, et al. Family factors associated with Eating Disorders: a review. Rev Mex Trastor Aliment. 2013; 4 (1):45–57. Spanish. [ Google Scholar ]

- Góngora VC. Satisfaction with life, well-being, and meaning in life as protective factors of eating disorder symptoms and body dissatisfaction in adolescents. Eat Disord. 2014; 22 (5):435–49. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2014.931765. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levine MP, Smolak L. The role of protective factors in the prevention of negative body image and disordered eating. Eat Disord. 2016; 24 (1):39–46. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2015.1113826. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haines J, Kleinman KP, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Examination of shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010; 164 (4):336–43. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.19. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Eating Disorders in Adolescents Essay

Eating disorder as a severe health condition that can be manifested in many different ways may tackle a person of any age, gender, and socio-cultural background. However, adolescents, especially when it comes to female teenagers, are considered to be the most vulnerable in terms of developing this condition (Izydorczyk & Sitnik-Warchulska, 2018). According to the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP, 2018), 10 in 100 young women struggle with an eating disorder. Thus, the purpose of the present paper is to dwell on the specifics of external factors causing the disorder as well as the ways to deal with this issue.

To begin with, it is necessary to define which diseases are meant under the notion of an eating disorder. Generally, eating disorders encompass such conditions as anorexia nervosa, bulimia, binge eating, and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) (AACAP, 2018). Although these conditions have different manifestations in the context of eating patterns, all of them affect teenager’s nutrition patterns and average weight. According to the researchers, there exist common external stressors that lead to an eating disorder, such as:

- Socio-cultural appearance standards. For the most part, modern culture and mass media promote certain body images as a generally accepted ideal, which causes many teenage girls to doubt their appearance and follow the mass trends.

- Biological factors. Some teenagers might have a genetic predisposition for certain disorders if anyone in the family struggled with the disease at some point in the past.

- Emotional factors. Children, who are at risk of being affected by such mental disorders as anxiety and depression, are likely to disrupt their nutrition patterns.

- Peer pressure. Similar to socio-cultural standards, peer pressure dictates certain criteria for the teenagers’ body image, eventually impacting their perception of food and nutrition (Izydorczyk & Sitnik-Warchulska, 2018).

With such a variety of potential stressors, it is imperative for both medical professionals and caregivers to pay close attention to the teenager’s eating habits. Thus, in order to assess the issue, any medical screening should include weight and height measurements. In such a way, medical professionals are able to define any discrepancies in the measurements over time and bring this issue up with a patient. When working with adolescents, it is of paramount importance to establish a trusting relationship with a patient, as teenagers are extremely vulnerable at this age. After identifying any issue related to weight and body image, nurses and physicians need to ask the patient whether they have any problems with eating. In case they are not willing to talk on the matter, it is necessary to emphasize that their response will not be shared with caregivers unless they want it. It is also necessary to ask questions regarding the child’s relationship with peers carefully, as they may easily become an emotional trigger.

In order to avoid such complications as eating disorders, it is vital for caregivers to talk with their children on the topic of the aforementioned stressors. Firstly, they need to promote healthy eating patterns by explaining why it is important for one’s body instead of giving orders to the child. For additional support, they may ask a medical professional to justify this information. Secondly, the caregivers need to dedicate time to explain the inappropriateness of body standards promoted by the mass media and promote diversity and positive body image within the family. Lastly, caregivers are to secure a safe environment for the teenager’s fragile self-esteem and self-actualization in order for them to feel more confident among peers (Boberová & Husárová, 2021). These steps, although frequently undermined, contribute beneficially in terms of dealing with eating disorders external stressors among adolescents.

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry [AACAP]. (2018). Eating disorders in teens. Web.

Boberová, Z., & Husárová, D. (2021). What role does body image in relationship between level of health literacy and symptoms of eating disorders in adolescents?. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 18 (7), 3482.

Izydorczyk, B., & Sitnik-Warchulska, K. (2018). Socio-cultural appearance standards and risk factors for eating disorders in adolescents and women of various ages. Frontiers in psychology , 9 , 429.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, June 23). Eating Disorders in Adolescents. https://ivypanda.com/essays/eating-disorders-in-adolescents/

"Eating Disorders in Adolescents." IvyPanda , 23 June 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/eating-disorders-in-adolescents/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Eating Disorders in Adolescents'. 23 June.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Eating Disorders in Adolescents." June 23, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/eating-disorders-in-adolescents/.

1. IvyPanda . "Eating Disorders in Adolescents." June 23, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/eating-disorders-in-adolescents/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Eating Disorders in Adolescents." June 23, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/eating-disorders-in-adolescents/.

- External Stressors in Adolescents

- Eating Disorders in Adolescent Girls

- Influence of Modelling in Teenager’s Eating Disorders

- Socio-Cultural Approach of Humanity Examination

- Eating and Mood Disorders Among Adolescents

- Stressors in Nursing Workplace

- Environmental Stressors

- Organizational Stressors, Their Results and Types

- Eating Disorders in Male Adolescents as Health Topic

- The Socialization of the Caregivers

- Discussion Board Post: Distinction between the Public and Private

- Cyberbullying: Definition, Forms, Groups of Risk

- Human Trafficking and Healthcare Organizations

- The Politics of Abortion in Modern Day Jamaica

- Challenges of Prisoner Re-Entry Into Society

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Adolescence

Eating Disorders in Teens Have ‘Exploded’ in the Pandemic

Here’s what parents need to know.

By Lisa Damour

As a psychologist who cares for adolescents I am well aware of the prevalence of eating disorders among teenagers . Even still, I am stunned by how much worse the situation has become in the pandemic.

According to the psychologist Erin Accurso, the clinical director of the eating disorders program at the University of California, San Francisco, “our inpatient unit has exploded in the past year,” taking in more than twice as many adolescent patients as it did before the pandemic. Dr. Accurso explained that outpatient services are similarly overwhelmed: “Providers aren’t taking new clients, or have wait-lists up to six months.”

The demand for eating disorder treatment “is way outstretching the capacity to address it,” said the epidemiologist S. Bryn Austin, a professor at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health and research scientist in the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital. “I’m hearing this from colleagues all across the country.” Even hotlines are swamped. The National Eating Disorders Association helpline has had a 40 percent jump in overall call volume since March 2020. Among callers who shared their age over the last year, 35 percent were 13 to 17 years old, up from 30 percent in the year before the pandemic.

What has changed in the pandemic?

There are several possible explanations for this tsunami of eating concerns in teenagers. When adolescents lost the familiar rhythm of the school day and were distanced from the support of their friends, “many of the things that structured a teenager’s life evaporated in one fell swoop,” said Dr. Walter Kaye, a psychiatrist and the founder and executive director of the eating disorders program at the University of California, San Diego. “People who end up with eating disorders tend to be anxious and stress sensitive — they don’t do well with uncertainty.”

Further, eating disorders have long been linked with high achievement . Driven adolescents who might have normally poured their energy into their academic, athletic or extracurricular pursuits suddenly had too much time on their hands. “Some kids turned their attention toward physical health or appearance as a way to cope with anxiety or feel productive,” Dr. Accurso said. “Their goals around ‘healthy’ eating or getting ‘in shape’ got out of hand” and quickly caused significant weight loss.

For some, an increase in emotional eating in the pandemic has been part of the problem. Attending school from a home where food is constantly available may lead some young people to eat more than usual as a way to manage pandemic-related boredom or stress . “Being at school presents a barrier to using food as a coping mechanism; at home, we don’t have that barrier,” noted Kelly Bhatnagar, psychologist and co-founder of the Center for Emotional Wellness in Beachwood, Ohio, a practice specializing in the treatment of eating disorders.

In many households the pandemic has heightened food insecurity and its attendant anxieties, which can increase the risk of eating disorders. Research shows that, compared to teenagers whose families have enough food, those in homes where food is scarce are more likely to fast, to skip meals, and to abuse laxatives and diuretics with the aim of controlling their weight.

The Instagram influence

What teens see on their screens is also a factor. During the pandemic, teenagers have spent more time than usual on social media . While that can be a source of much needed connection and comfort , scrutinizing images of peers and influencers on highly visual social media has been implicated in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating . Dr. Austin noted that teenagers can be prone to comparing their own bodies to the images they see online. “That comparison creates a downward spiral in terms of body image and self-esteem. It makes them more likely to adopt unhealthy weight control behaviors.”

When adolescents take an interest in managing their weight, they often go looking for guidance online. Indeed, a new Common Sense Media survey found that among teenagers who sought health information online between September and November of 2020, searches on fitness and exercise information came second only to searches for content related to Covid-19 — and ahead of searches on anxiety, stress and depression.

What young people find when they go looking for fitness information can be highly problematic. They are likely to come across harmful “thinspiration” and “fitspiration” posts celebrating slim or sculpted bodies, or even sites that encourage eating disordered behavior . Worse, algorithms record online search information and are “deliberately designed to feed harmful weight loss content to users who are already struggling with body image,” such as advertisements for dangerous diet supplements, Dr. Austin said.

When to worry

With so many forces contributing to teenagers’ body dissatisfaction and eating disordered behavior, how do parents know when to worry?

Parents should be alarmed, Dr. Kaye said, “if your child suddenly loses 10 to 20 pounds, becomes secretive about eating, or if you are seeing food disappear,” as becoming furtive about what, how and when one eats is a common occurrence in anorexia, bulimia and other eating disorders.

Experts agree that adults should be on the lookout for behaviors that veer from previous norms, such as suddenly skipping family meals or refusing to eat food from entire categories, such as carbohydrates or processed foods. Worth concern, too, is the teenager who develops fixations such as carefully counting calories, exercising obsessively or hoarding food, which may be a sign of a binge eating disorder. Parents should also pay close attention, said Dr. Accurso, if adolescents express a lot of guilt or anxiety around food or eating, or feel unhappy or uncomfortable with their bodies.

According to Dr. Bhatnagar, the view of eating disorders as a “white girls’ illness” can keep teens who are not white girls from seeking help or being properly screened for eating disorders by health professionals, even though eating disorders regularly occur across both sexes and all ethnic groups .

“Boys are having the same troubles,” said Dr. Bhatnagar, “but heterosexual boys may talk about body image a little differently. They tend to talk in terms of getting fit, getting lean or being muscular.”

Dr. Austin also noted that it is common to see elevated rates of eating disorders in lesbian, gay and bisexual youth of all genders as well as transgender and gender diverse young people.

“Eating disorders,” Dr. Accurso said, “don’t discriminate.”

How to help

Research shows that early identification and intervention play a key role in the successful treatment of eating disorders. Accordingly, parents who have questions about their teen’s relationship with eating, weight or exercise should not hesitate to seek an evaluation from their pediatrician or family health provider. Trustworthy eating disorder information, screening tools and support can also be found online. And when necessary, online resources can provide guidance and support to those on treatment waiting lists. “It may not be ideal for many,” Dr. Kaye said, “but it’s the reality of the situation we’re in.”

Parents can also take steps to reduce the likelihood that an eating disorder will take hold in the first place. Experts encourage adults to model a balanced approach to eating and to create enjoyable opportunities for being physically active while steering clear of negative comments about their teenager’s body or their own. Parents should also openly address the dangers of a ubiquitous diet culture that emphasizes appearance over well-being, creates stigma and shame around weight and links body size to character and worth. As Dr. Accurso noted, “We are not defined by a number on a scale.”

Where to find help

The National Eating Disorders Association , or NEDA, is a good starting place. It supports individuals and families affected by eating disorders.

F.E.A.S.T. is an international nonprofit organization run by caregivers of those suffering from eating disorders, meant to help others.

Maudsley Parents was created by parents who helped their children recover with family-based treatment , to offer hope and help to other families confronting eating disorders.

The Academy for Eating Disorders offers many resources, as do the Eating Disorders Center for Treatment and Research at University of California, San Diego, and the Eating Disorders Program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Lisa Damour is a psychologist and the author of the New York Times best sellers “Untangled” and “Under Pressure.” Dr. Damour also co-hosts the podcast “Ask Lisa: The Psychology of Parenting.” More about Lisa Damour

How to Communicate Better With the Teens in Your Life

Simple strategies can go a long way toward building a stronger, more open relationship..

Active listening is an essential skill when seeking to engage any family member in conversation — teens included. Here is how to get better at it .

There are many reasons why a teen might not be opening up to you. These are the most common explanations for their silence .

Is your kid dismissing your solutions to their problems as irritating or irrelevant? It is usually because they’re not looking for you solve their problems.

Developing a healthy relationship with social media can be tricky. Here is how to talk to teens about it .

If your teen is surly or standoffish, these strategies can help you reconnect .

Are you worried that your kid might be struggling with his or her mental health? Understand the warning signs and make sure to approach the issue with the utmost sensitivity.

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

INTRODUCTION

Definitions, epidemiology, screening for eating disorders, assessment of children and adolescents with suspected eating disorders, laboratory evaluation, medical complications in patients with eating disorders, psychological and neurologic effects, dermatologic effects, dental and/or oral effects, cardiovascular effects, gastrointestinal tract effects, renal and electrolyte effects, endocrine effects, treatment principles across the eating disorder spectrum, the pediatrician’s role in care, financial considerations, pediatrician’s role in prevention and advocacy, guidance for pediatricians, lead authors, committee on adolescence, 2018–2019, identification and management of eating disorders in children and adolescents.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Laurie L. Hornberger , Margo A. Lane , THE COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE , Laurie L. Hornberger , Margo Lane , Cora C. Breuner , Elizabeth M. Alderman , Laura K. Grubb , Makia Powers , Krishna Kumari Upadhya , Stephenie B. Wallace , Laurie L. Hornberger , Margo Lane , MD FRCPC , Meredith Loveless , Seema Menon , Lauren Zapata , Liwei Hua , Karen Smith , James Baumberger; Identification and Management of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics January 2021; 147 (1): e2020040279. 10.1542/peds.2020-040279

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Eating disorders are serious, potentially life-threatening illnesses afflicting individuals through the life span, with a particular impact on both the physical and psychological development of children and adolescents. Because care for children and adolescents with eating disorders can be complex and resources for the treatment of eating disorders are often limited, pediatricians may be called on to not only provide medical supervision for their patients with diagnosed eating disorders but also coordinate care and advocate for appropriate services. This clinical report includes a review of common eating disorders diagnosed in children and adolescents, outlines the medical evaluation of patients suspected of having an eating disorder, presents an overview of treatment strategies, and highlights opportunities for advocacy.

Although the earliest medical account of an adolescent patient with an eating disorder was more than 300 years ago, 1 a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology and psychobiology of eating disorders remains elusive today. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition ( DSM-5 ) includes the latest effort to describe and categorize eating disorders, 2 placing greater emphasis on behavioral rather than physical and cognitive criteria, thereby clarifying these conditions in those children who do not express body or weight distortion. DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for several of the eating disorders commonly seen in children and adolescents are presented in Table 1 .

Diagnostic Features of Eating Disorders Commonly Seen in Children and Adolescents

Adapted from the DSM-5 , American Psychiatric Association, 2013. 2

Notable changes in DSM-5 since the previous edition include the elimination of amenorrhea and specific weight percentiles in the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (AN) and a reduction in the frequency of binge eating and compensatory behaviors required for the diagnosis of bulimia nervosa (BN). The diagnosis “eating disorder not otherwise specified” has been eliminated, and several diagnoses have been added, including binge-eating disorder (BED) and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). 3 – 5 The diagnosis of ARFID encompasses feeding behaviors previously categorized in the fourth edition ( DSM-IV ) as “feeding disorder of infancy and early childhood” and expands these into adolescence and adulthood. Individuals with ARFID intentionally limit intake for reasons other than for concern for body weight, such as the sensory properties of food, a lack of interest in eating, or a fear of adverse consequences with eating (eg, choking or vomiting). As a result, they may experience weight loss or failure to achieve expected weight gain, malnutrition, dependence on nutritional supplementation, and/or interference with psychosocial functioning. 6 – 9 The category “other specified feeding and/or eating disorder” is now applied to patients whose symptoms do not meet the full criteria for an eating disorder despite causing significant distress or impairment. Among these disorders is atypical AN in which diminished self-worth, nutritional restriction, and weight loss mirrors that seen with AN, although body weight at presentation is in the normal or above-normal range. Efforts are ongoing to further categorize abnormal eating behaviors and refine diagnoses. 10

Prevalence data for eating disorders vary according to study populations and the criteria used to define an eating disorder. 11 A systematic review of prevalence studies published between 1994 and 2013 found widely varied estimates in the lifetime prevalence of eating disorders, with a range from 1.0% to 22.7% for female individuals and 0.3% to 0.6% for male indnividuals. 12 A 2011 cross-sectional survey of more than 10 000 nationally representative US adolescents 13 to 18 years of age estimated prevalence rates of AN, BN, and BED at 0.3%, 0.9%, and 1.6%, respectively. Behaviors suggestive of AN and BED but not meeting diagnostic thresholds were identified in another 0.8% and 2.5%, respectively. The mean age of onset for each of these disorders was 12.5 years. 13 Several studies have suggested higher BED prevalence rates of 2% to 4%, with a more equal distribution between girls and boys, making it perhaps the most common eating disorder among adolescents. 14 In contrast, the diagnoses seen in treatment may belie the relative prevalence of these disorders. In a review of 6 US adolescent eating disorder treatment programs, the distribution of diagnoses was 32% AN, 30% atypical AN, 9% BN, 19% ARFID, 6% purging disorder, and 4% others. 15 This may reflect the underrecognition and/or undertreatment of disorders such as BED.

Although previously mischaracterized as diseases of non-Hispanic white, affluent adolescent girls, eating disorder behaviors are increasingly recognized across all racial and ethnic groups 16 – 20 and in lower socioeconomic classes, 21 preadolescent children, 22 males, and children and adolescents perceived as having an average or increased body size.

Preteens with eating disorders are more likely than older adolescents to have premorbid psychopathology (depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or other anxiety disorders) and less likely to have binge and purge behaviors. There is a more equal distribution of illness by sex among younger patients and, frequently, more rapid weight loss, leading to earlier presentation to health care providers. 23

Although diagnosis in males may increase with the more inclusive DSM-5 criteria, 24 , 25 it is often delayed because of the misperception of health care providers that eating disorders are female disorders. 26 In addition, disordered eating attitudes may differ in male individuals, 27 focusing on leanness, weight control, and muscularity. Purging, use of muscle-building supplements, substance abuse, and comorbid depression are common in males. 28 – 30

Eating disorders can occur in individuals with various body habitus, and their presence in those of larger body habitus is increasingly apparent. 31 – 34 Weight stigma (the undervaluation or negative stereotyping of individuals because they have overweight or obesity) seems to play a role. Adolescents with larger body habitus are exposed to weight stigma through the media, their families, peers, and teachers, and health care professionals, resulting in depression, anxiety, poor body image, social isolation, unhealthy eating behaviors, and worsening obesity. 35 When presenting with significant weight loss but a BMI still classified in the “healthy,” overweight, or obese ranges, patients with eating disorders such as atypical AN may be overlooked by health care providers 36 , 37 but may experience the same severe medical complications as those who are severely underweight. 38 – 40

Increased rates of disordered eating may be found in sexual minority youth. 41 – 43 Analysis of Youth Risk Behavior Survey data reveals lesbian, gay, and bisexual high school students have significantly higher rates of unhealthy and disordered weight-control behaviors than their heterosexual peers. 44 , 45 Transgender youth may be at particular risk. 46 , 47 In a survey of nearly 300 000 college students, transgender students had the highest rates of self-reported eating disorder diagnoses and compensatory behaviors (ie, use of diet pills or laxatives or vomiting) compared with all cisgender groups. Nearly 16% of transgender respondents reported having been diagnosed with an eating disorder, as compared with 1.85% of cisgender heterosexual women. 48

Adolescents with chronic health conditions requiring dietary control (eg, diabetes, cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and celiac disease) may also be at increased risk of disordered eating. 49 – 51 Among teenagers with type 1 diabetes mellitus, at least one-third may engage in binge eating, self-induced vomiting, insulin omission for weight loss, and excessive exercise, 52 , 53 resulting in poorer glycemic control. 54

Many adolescents engage in dietary practices that may overlap with or disguise eating disorders. The lay term "orthorexia" describes the behavior of individuals who become increasingly restrictive in their food consumption, not based on concerns for quantity of food but the quality of food (eg, specific nutritional content or organically produced). The desire to improve one’s health through optimal nutrition and food quality is the initial focus of the patient, and weight loss and/or malnutrition may ensue as various foods are eliminated from the diet. Individuals with orthorexia may spend excessive amounts of time in meal planning and experience extreme guilt or frustration when their food-related practices are interrupted. 55 , 56 Psychologically, this behavior appears to be related to AN and obsessive-compulsive disorder 57 and is considered by some to be a subset within the restrictive eating disorders. Vegetarianism is a lifestyle choice adopted by many adolescents and young adults that may sometimes signal underlying eating pathology. 58 , 59 In a comparison of adolescent and young adult females with and without a history of eating disorders, those with eating disorders were more likely to report ever having been vegetarian. Many of these young women acknowledged that their decision to become vegetarian was primarily motivated by their desire for weight loss, and most reported that they had done so at least a year after first developing eating disorder symptoms. 60

In an attempt to improve performance or achieve a desired physique, adolescent athletes may engage in unhealthy weight-control behaviors. 61 The term “female athlete triad” has historically referred to (1) low energy availability that may or may not be related to disordered eating; (2) menstrual dysfunction; and (3) low bone mineral density (BMD) in physically active females. 62 – 65 Inadequate caloric intake in comparison to energy expenditure is the catalyst for endocrine changes and leads to decreased bone density and menstrual irregularities. Body weight may be stable. This energy imbalance may result from a lack of knowledge regarding nutritional needs in the athlete or from intentional intake restriction associated with disordered eating.

Hormonal disruption and low BMD can occur in undernourished male athletes as well. 66 Increased recognition of the role of energy deficiency in disrupting overall physiologic function in both male and female individuals led a 2014 International Olympic Committee consensus group to recommend replacing the term female athlete triad to the more inclusive term, “relative energy deficiency in sport.” 67 , 68 Athletes participating in sports involving endurance, weight requirements, or idealized body shapes may be at particular risk of relative energy deficiency in sport. Signs and symptoms of relative energy deficiency, such as amenorrhea, bradycardia, or stress fractures, may alert pediatricians to this condition.

Pediatricians are in a unique position to detect eating disorders early and interrupt their progression. Annual health supervision visits and preparticipation sports examinations offer opportunities to screen for eating disorders. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents , fourth edition, offers sample screening questions about eating patterns and body image. 69 Reported dieting, body image dissatisfaction, experiences of weight-based stigma, or changes in eating or exercise patterns invite further exploration. Positive responses on a standard review of symptoms may need further probing. For example, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea (either primary or secondary) may indicate energy deficiency. 70 Serial weight and height measurements plotted on growth charts are invaluable. Weight loss or the failure to make expected weight gain may be more obvious when documented on a graph. Similarly, weight fluctuations or rapid weight gain may cue a health care provider to question binge eating or BN symptoms. Recognizing that many patients who present to eating disorder treatment programs have or previously had elevated weight according to criteria from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 71 it is worthwhile to carefully inquire about eating and exercise patterns when weight loss is noted in any child or adolescent. Screening for unhealthy and extreme weight-control measures before praising desirable weight loss can avoid inadvertently reinforcing these practices.

A comprehensive assessment of a child or adolescent suspected of having an eating disorder includes a thorough medical, nutritional, and psychiatric history, followed by a detailed physical examination. A useful web resource for assessment is published in multiple languages by the Academy for Eating Disorders. 72 Relevant interview questions are listed in Table 2 . A collateral history from a parent may reveal abnormal eating-related behaviors that were denied or minimized by the child or adolescent.

Example Questions to Ask Adolescents With a Possible Eating Disorder

Adapted from Rome and Strandjord. 89 LMP, last menstrual period.

A full psychosocial assessment, including a home, education, activities, drugs/diet, sexuality, suicidality/depression (HEADSS) assessment is vital. This evaluation includes screening for physical or sexual abuse by using the principles of trauma-informed care and responding according to American Academy of Pediatrics guidance on suspected physical or sexual abuse or sexual assault 73 – 75 as well as state laws. Vital to the HEADSS assessment is an evaluation for symptoms of other potential psychiatric diagnoses, including suicidal thinking, which may have been unrecognized previously.

A comprehensive physical examination, including close attention to growth parameters and vital signs, allows the pediatrician to assess for signs of medical compromise and for signs and symptoms of eating disorder behaviors; findings may be subtle and, thus, overlooked without careful notice. For accuracy, weights are best obtained after the patient has voided and in an examination gown without shoes. Weight, height, and BMI can be evaluated by using appropriate growth charts. Low body temperature, resting blood pressure (BP), or resting heart rate (HR) for age may suggest energy restriction. Because a HR of 50 beats per minute or less is unusual even in college-aged athletes, 76 the finding of a low HR may be a sign of restrictive eating. Orthostatic vital signs (HR and BP, obtained after 5 minutes of supine rest and repeated after 3 minutes of standing) 77 , 78 revealing a systolic BP drop greater than 20 mm Hg, a diastolic BP drop greater than 10 mm Hg, or tachycardia may suggest volume depletion from restricted fluid intake or purging or a compromised cardiovascular system.

Pertinent physical findings in children and adolescents with eating disorders are summarized in Table 3 . A differential diagnosis for the signs and symptoms of an eating disorder is found in Table 4 , and selected medical complications of eating disorders are provided in Table 5 .

Notable Physical Examination Features in Children and Adolescents With Eating Disorders

Adapted from Rosen; American Academy of Pediatrics. 208

Selected Differential Diagnosis for Eating Disorders According to Presentation

Adapted from Rome and Strandjord 89 and Rosen; American Academy of Pediatrics. 208

Selected Medical Complications Resulting From Eating Disorders

Initial laboratory evaluation is performed to screen for medical complications of eating disorders or to rule out alternate diagnoses ( Tables 4 and 5 ). Typical initial laboratory testing includes a complete blood cell count; serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and glucose; liver transaminases; urinalysis; and thyroid-stimulating hormone concentration. 72 Screening for specific vitamin and mineral deficiencies (eg, vitamin B 12 , vitamin D, iron, and zinc) may be indicated on the basis of the nutritional history of the patient. Laboratory investigations are often normal in patients with eating disorders; normal results do not exclude the presence of serious illness with an eating disorder or the need for hospitalization for medical stabilization. An electrocardiogram is important for those with significant weight loss, abnormal cardiovascular signs (such as orthostasis or bradycardia), or an electrolyte abnormality. A urine pregnancy test and serum gonadotropin and prolactin levels may be indicated for girls with amenorrhea; a serum estradiol concentration may serve as a baseline for reassessment during recovery. 79 Similarly, serum gonadotropin and testosterone levels can be useful to assess and monitor for central hypogonadism in boys with restrictive eating. Bone densitometry, by using dual radiograph absorptiometry analyzed with age-appropriate software, may be considered for those with amenorrhea for more than 6 to 12 months. 80 , 81 If there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, other studies including inflammatory markers, serological testing for celiac disease, serum cortisol concentrations, testing stool for parasites, or radiographic imaging of the brain or gastrointestinal tract may be considered. In the occasional patient, both an eating disorder and an organic illness, such as celiac disease, may be discovered. 82

Eating disorders can affect every organ system 83 , 84 with potentially serious medical complications that develop as a consequence of malnutrition, weight changes, or purging. Details of complications are described in reviews 85 – 89 and are summarized in Table 5 . Most medical complications resolve with weight normalization and/or resolution of purging. Complications of BED can include those of obesity; these are summarized in other reports and not reiterated here. 84 , 90

Psychological symptoms can be primary to the eating disorder, a feature of a comorbid psychiatric disorder, or secondary to starvation. Initial symptoms of depression and anxiety may abate with refeeding. 91 Rumination about body weight and size is a core feature of AN, whereas rumination about food decreases as starvation reverses. 92 Difficulty in emotion regulation occurs across the spectrum of eating disorders but is more severe in those who binge eat or purge. 93 Cognitive function studies in a large population-based sample of adolescents revealed eating disorder participants had deficits in executive functioning, including global processing and cognitive flexibility but performed better than control participants on measures of visual attention and vigilance. 94

Structural brain imaging studies to date have yielded inconsistent results, likely explained, at least in part, by methodologic differences and the need to control for many variables, including nutritional state, hydration, medication use, and comorbid illness. 95 A longitudinal study revealed that global cortical thinning in acutely ill adolescents and young adults with AN normalized with weight restoration over a period of approximately 3 months. 96

Common skin changes in underweight patients include lanugo, hair thinning, dry scaly skin, and yellow discoloration related to carotenemia. Brittle nails and angular cheilitis may also be observed. Acrocyanosis can be observed in underweight patients and may be a protective mechanism against heat loss. Abrasions and calluses over the knuckles can occur from cutting the skin on incisors while self-inducing emesis. 97

Patients with eating disorders experience higher rates of dental erosion and caries. This occurs more frequently in those who self-induce emesis but can also be observed in those who do not. 98 Normal dental findings do not preclude the possibility that purging is occurring. 99 Hypertrophy of the parotid and other salivary glands, accompanied by elevations in serum amylase concentrations with normal lipase concentrations, may be a clue to vomiting. 99 Xerostomia, from either salivary gland dysfunction or psychiatric medication side effect, can reduce the oral pH, which can lead to increased growth of cariogenic oral bacteria. 98 , 100

Reports of cardiac complications in eating disorders are focused predominantly on restrictive eating disorders. Common cardiovascular signs include low HR, orthostasis, and poor peripheral perfusion. Orthostatic intolerance symptoms (eg, lightheadedness) and vital sign findings may resemble those of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome 101 , 102 and may contribute to a delay in referral to appropriate care if eating disorder behaviors are not disclosed or appreciated.

Cardiac structural changes include decreased left ventricular (LV) mass, LV end diastolic and LV end systolic volumes, functional mitral valve prolapse, pericardial effusion, and myocardial fibrosis (noted in adults). 103 – 105 Electrocardiographic abnormalities, including sinus bradycardia, and lower amplitude LV forces are more common in AN than in nonrestrictive eating disorders. 106 One study reported a nearly 10% prevalence of prolonged (>440 milliseconds) QTc interval in hospitalized adolescents and young adults with a restrictive eating disorder. 107 Repolarization abnormalities, a potential precipitant to lethal arrhythmia, 108 may prompt clinicians to also consider other factors, such as medication use or electrolyte abnormalities, that may affect cardiac conduction. 107 , 109

Gastrointestinal complaints are common and sometimes precede the diagnosis of the eating disorder. Delayed gastric emptying and slow intestinal transit time often contribute to reported sensations of nausea, bloating, and postprandial fullness 110 and may be a presenting feature of restrictive eating. Constipation is a frequent experience for patients and multifactorial in etiology. 111 Esophageal mucosal damage from self-induced vomiting, including scratches, and bleeding secondary to Mallory-Weiss tears can occur. 99 Superior mesenteric artery syndrome may develop in the setting of severe weight loss. 111 Hepatic transaminase concentrations and coagulation times can be elevated as a consequence of malnutrition and, typically, normalize with appropriate nutrition. 110

Fluid and electrolyte abnormalities may occur as a result of purging or cachexia. 99 , 112 Dehydration can be present in any patient with an eating disorder. Disordered osmotic regulation can present in many patterns (central and renal diabetes insipidus, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone). 112 Patients who vomit may have a hypokalemic, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis resulting from loss of gastric hydrochloric acid, chronic dehydration, and the subsequent increase in aldosterone that promotes sodium reabsorption in exchange for potassium and acid at the distal tubule level. 113 Patients who abuse laxatives may experience a variety of electrolyte and acid-base derangements. 113 Dilutional hyponatremia can be observed in patients who intentionally water load to induce satiety or to misrepresent their weight at clinic visits. Abrupt cessation of laxative use may be associated with peripheral edema and, therefore, motivate further laxative 114 or diuretic misuse.

Restrictive eating disorders commonly cause endocrine dysfunction. 80 , 115 Euthyroid sick syndrome (low triiodothyronine, elevated reverse triiodothyronine, or normal or low thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone) is the most common thyroid abnormality. 116 Functioning as an adaptive mechanism to starvation, supplemental thyroid hormone is not indicated when this pattern is noted. 116 Hypercortisolemia may be seen in AN. 81 , 116 Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis suppression may be attributable to weight loss, physical overactivity, or stress. Female individuals with AN may have amenorrhea, and male individuals can have small testicular volumes 117 and low testosterone concentrations. 118

Growth retardation, short stature, and pubertal delay may all be observed in prepubertal and peripubertal children and adolescents with eating disorders. 115 AN is associated with low levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 and growth hormone resistance. 119 Catch-up growth has been inconsistently reported in the literature; younger patients may have greater and more permanent effects on growth. 120 , 121 Adolescent boys may be at an even greater risk for height deficits than girls; because boys typically enter puberty later than girls and experience their peak growth at a later sexual maturity stage, they are less likely to have completed their growth if an eating disorder develops in the middle teenage years. 119

Low BMD is a frequent complication of eating disorders in both male and female patients 117 and is a risk in both AN and BN. 122 Low BMD is worrisome not only because of the increased risk of fractures in the short-term 123 but, also, because of the potential to irreversibly compromise skeletal health in adulthood. 124

The ultimate goals of care in eating disorders are that children and adolescents are nourished back to their full healthy weight and growth trajectory, that their eating patterns and behaviors are normalized, and that they establish a healthy relationship with food and their body weight, shape, and size as well as a healthy sense of self. Independent of a specific DSM diagnosis, treatment is focused on nutritional repletion and psychological therapy. Psychotropic medication can be a useful adjunct in select circumstances.

After diagnosing an eating disorder, the pediatrician arranges appropriate care. Patients who are medically unstable may require urgent referral to a hospital ( Table 6 ). Patients with mild nutritional, medical, and psychological dysfunction may be managed in the pediatrician’s office in collaboration with outpatient nutrition and mental health professionals with specific expertise in eating disorders. Because an early response to treatment may be associated with better outcomes, 125 , 126 timely referral to a specialized multidisciplinary team is preferred, when available. If resources do not exist locally, pediatricians may need to partner with health experts who are farther away for care. For patients who do not improve promptly with outpatient care, more intensive programming (eg, day-treatment programs or residential settings) may be indicated.

Indications Supporting Hospitalization in an Adolescent With an Eating Disorder

Reprinted with permission from the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. 85 ECG, electrocardiogram.

Often, an early task of the pediatrician is to identify a treatment goal weight. This goal weight may be determined in collaboration with a registered dietitian. Pediatricians who are planning to refer the patient to a specialized treatment team may opt to defer the task to the team. Acknowledging that body weights naturally fluctuate, the treatment goal weight is often expressed as a goal range. Individualized treatment goal weights are formulated on the basis of age, height, premorbid growth trajectory, pubertal stage, and menstrual history. 87 , 127 In a study of adolescent girls with AN, of those who resumed menses during treatment, this occurred, on average, at 95% of the treatment goal weight. 128 Health care providers may be pressured by patients, their patients’ parents, or other health care providers to target a treatment goal weight that is lower than the previous growth trajectory or other clinical indicators would suggest is appropriate. If a treatment goal weight is inappropriately low, there is an inherent risk of offering only partial weight restoration and insufficient treatment. 129 The treatment goal weight is reassessed at regular intervals (eg, every 3–6 months) to account for changes in physical growth and development (in particular, age, height, and sexual maturity). 87 , 127

An important role for the pediatrician is to offer guidance regarding eating and to manage the physical aspects of the illnesses. For all classifications of eating disorders, reestablishing regular eating patterns is a fundamental early step. Meals and snacks are reintroduced or improved in a stepwise manner, with 3 meals and frequent snacks per day. Giving the message that “food is the medicine that is required for recovery” and promoting adherence to taking that medicine at scheduled intervals often helps patients and families get on track. 130 A multivitamin with minerals can help ensure that deficits in micronutrients are addressed. To optimize bone health, calcium and vitamin D supplements can be dosed to target recommended daily amounts (elemental calcium: 1000 mg for patients 4–8 years of age, or 1300 mg for patients 9–18 years of age; vitamin D: 600 IU for patients 4–18 years of age). 87 , 131 Patients can be reassured that the bloating discomfort caused by slow gastric emptying improves with regular eating. When constipation is troubling, nutritional strategies, including weight restoration, are the treatments of choice. 111 When these interventions are inadequate to alleviate constipation, osmotic (eg, polyethylene glycol 3350) or bulk-forming laxatives are preferred over stimulant laxatives. The use of nonstimulant laxatives decreases the risks of electrolyte derangement and avoids the potential hazard of “cathartic colon syndrome” that may be associated with abuse of stimulant cathartics (senna, cascara, bisacodyl, phenolphthalein, anthraquinones). 99 , 114

To optimize dental outcomes, patients can be encouraged to disclose their illness to their dentist. Current dental hygiene recommendations for patients who vomit include the use of topical fluoride, applied in the dental office or home, or use of a prescription fluoride (5000 ppm) toothpaste. Because brushing teeth immediately after vomiting may accelerate enamel erosion, patients can be advised to instead rinse with water, followed by using a sodium fluoride rinse whenever possible. 132

Collaborative Outpatient Care