- Website Inauguration Function.

- Vocational Placement Cell Inauguration

- Media Coverage.

- Certificate & Recommendations

- Privacy Policy

- Science Project Metric

- Social Studies 8 Class

- Computer Fundamentals

- Introduction to C++

- Programming Methodology

- Programming in C++

- Data structures

- Boolean Algebra

- Object Oriented Concepts

- Database Management Systems

- Open Source Software

- Operating System

- PHP Tutorials

- Earth Science

- Physical Science

- Sets & Functions

- Coordinate Geometry

- Mathematical Reasoning

- Statics and Probability

- Accountancy

- Business Studies

- Political Science

- English (Sr. Secondary)

Hindi (Sr. Secondary)

- Punjab (Sr. Secondary)

- Accountancy and Auditing

- Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Technology

- Automobile Technology

- Electrical Technology

- Electronics Technology

- Hotel Management and Catering Technology

- IT Application

- Marketing and Salesmanship

- Office Secretaryship

- Stenography

- Hindi Essays

- English Essays

Letter Writing

- Shorthand Dictation

Essay on “Problems of Working Women” Complete Essay for Class 10, Class 12 and Graduation and other classes.

Problems of Working Women

The liberated woman has come to the face today. The term chiefly implies a woman who is independent economically. For other things a woman still needs her husband and family. She cannot be liberated in matters of marriages and family otherwise she will not be accepted by society. When we consider the problems of a working woman in our society, her domestic life comes to mind immediately. What is a modern working woman like?

A working woman of today may belong to the middle, lower or higher echelons of society. Working women of middle or lower class have the work for economic reasons while those belonging to the higher class work to pass time. The woman who works for financial reasons has to face many problems. They have to work in an office or organization, full-time. Often she is sniggered at; people make passes at her and criticize her work just because she is a woman. However hard working she might be in her work, there are people ready to find faults in her work in order to harass her if she does not submit to their lewd advances. And the poor woman cannot report against these people for fear of losing her job or her reputation in the eyes of colleagues, family or society. She, indeed, has to keep walking on a razors edge all the time.

Her domestic life is also not smooth. She does not get any reprieve from household work because of her office job. She has to get up early in the morning to finish her household chores, get the children ready for school, prepare breakfast and lunch for her husband and school going children, clean the house before she is ready to go to office. The western concept of the husband helping in household chores has not taken roof in our country yet. When she comes back in the evening she has to help her children with their studies, prepare evening meals and try and look pleasant in front of family members and guests. Nobody bothers to find out her requirement to be fulfilled. Nobody shows any consideration for the poor working woman. She is sandwiched between two worlds and reduced to a virtual robot, trying to perform her functions and duties to the best of her abilities. Woe betides her if she falters even once from the set path.

The concept of working woman, leading a blissful domestic life, has not yet been accepted bye out society. It is time to give some attention to the poor, harassed working woman who also bears the burden of domesticity. It lies with her husband and her immediate family to help lighter burden and assist her in leading a normal happy life.

Essay No. 02

Inequality between Men and Women in Workplace

Problems Faced by Women in Workplace

In this century, a woman actively participates in workplace. Many women desire a career and a place in this world. They want to stand on their own two feet, to become self-independent individuals, independent and free from other individuals. One thing that is clear is that women in all careers are striving to gain equality in the work force today. Through their determination, women now have the ability to break out of the gender roles that were created for them by society. One of the issues that have affected women in the workplace is that of stereotyping of women. Throughout history women have taken the role of housewife, mother, and nurturer. Women are stereotyped to stay at home and take care of the house and children. It has been their job to cook the meals, do the laundry, and manage the children’s school activities. Even today, motherhood is still considered to be the primary role for women. Women who do not take on this role are still thought of as selfish. Women that look to establish careers outside the home, for years, were thought of as being selfish and self-centered. Because women were viewed as homemakers they were often given jobs that were meaningless, and they were not thought of as managers or professionals. Even today, women are not treated the same as men. One i area that clearly shows this oppression is the area of equal pay for equal jobs. Another area in which women are at a disadvantage in the workplace is through discrimination. Discrimination can be an uncomfortable situation for the women involved. There are two types of discrimination, indirect and direct. Indirect discrimination might be a women being overlooked for a promotion, or an employee displaying inappropriate sexual material in the workplace. Direct discrimination may include a women being discharged from her employment because she is pregnant, or being excluded from after work group events. Another major area were women have been affected in the workplace is sexual harassment. Sexual harassment is closely linked to sex discrimination. Sexual discrimination forces women into lower paying jobs, and sexual harassment helps keep them there. One thing is clear, whether the problem is sexual harassment or sexual discrimination the problem continues to exist in the workplace, creating tension that make their jobs more difficult. In the last decade, companies have turned their attention to some of these issues. There has been more training and education about women’s issues. Even though there is more corporate training for these issues, this training may not work, but start educating people. Women need to overcome the image that they are sensitive People, which let their emotions control their mind. They need to, prove that they can think with their minds and not their hearts when it comes to business. Most people want to correct the unequal treatment of women in the workplace. One method that can be used to support equality would be to introduce legislation to guarantee equal pay for equal work. The logistical problems associated with this solution would be great. How would people measure the value of one person’s work another’s? ‘Who would decide this and how would it be implemented?

Our attitudes toward women in the workplace are slowly starting to change. More opportunities are appearing for women workers today than ever before. The unequal treatment of working women will take years to change, but change is occurring. This topic will remain until people treat and pay women equally, based upon their abilities. There have been many remedies introduced into the workplace that have tried to address the injustice toward women in the workplace.

Although there have been many improvements for women in the workplace but there are still many inequalities for women when compared to men. Remedies are needed to secure a fair and equal role in the workplace. This change can only fully occur when we change the attitudes of every individual toward women. When we accomplish that then we can finally achieve gender equality in the workplace.

About evirtualguru_ajaygour

commentscomments

Well portrayed!! What are the laws for sexual harassment at workplace?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Quick Links

Popular Tags

Visitors question & answer.

- Md shoaib sarker on Short Story ” The Lion and The Mouse” Complete Story for Class 10, Class 12 and other classes.

- Bhavika on Essay on “A Model Village” Complete Essay for Class 10, Class 12 and Graduation and other classes.

- slide on 10 Comprehension Passages Practice examples with Question and Answers for Class 9, 10, 12 and Bachelors Classes

- अभिषेक राय on Hindi Essay on “Yadi mein Shikshak Hota” , ”यदि मैं शिक्षक होता” Complete Hindi Essay for Class 10, Class 12 and Graduation and other classes.

Download Our Educational Android Apps

Latest Desk

- Samkaleen Bhartiya Mahilaye “समकालीन भारतीय महिलाएं” Hindi Essay, Nibandh 1000 Words for Class 10, 12 Students.

- Nijikarn – Gun evm Dosh “निजीकरण: गुण एवं दोष” Hindi Essay, Nibandh 1200 Words for Class 10, 12 Students.

- Bharat mein Mahilaon ke Rajnitik Adhikar “भारत में महिलाओं के राजनीतिक अधिकार” Hindi Essay, Nibandh 700 Words for Class 10, 12 Students.

- Bharat mein Jativad aur Chunavi Rajniti “भारत में जातिवाद और चुनावी राजनीति” Hindi Essay, Nibandh 1000 Words for Class 10, 12 Students.

- Example Letter regarding election victory.

- Example Letter regarding the award of a Ph.D.

- Example Letter regarding the birth of a child.

- Example Letter regarding going abroad.

- Letter regarding the publishing of a Novel.

Vocational Edu.

- English Shorthand Dictation “East and Dwellings” 80 and 100 wpm Legal Matters Dictation 500 Words with Outlines.

- English Shorthand Dictation “Haryana General Sales Tax Act” 80 and 100 wpm Legal Matters Dictation 500 Words with Outlines meaning.

- English Shorthand Dictation “Deal with Export of Goods” 80 and 100 wpm Legal Matters Dictation 500 Words with Outlines meaning.

- English Shorthand Dictation “Interpreting a State Law” 80 and 100 wpm Legal Matters Dictation 500 Words with Outlines meaning.

Essay on Working Mothers

Students are often asked to write an essay on Working Mothers in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Working Mothers

The importance of working mothers.

Working mothers play a pivotal role in our society. They not only contribute to the family’s income but also serve as role models for their children. They teach important values like hard work, independence, and resilience.

Challenges Faced by Working Mothers

Balancing work and family life can be challenging for working mothers. They often juggle multiple responsibilities like professional tasks, child care, and household chores. Despite these challenges, they strive to excel in both domains.

The Impact on Children

Children of working mothers learn to be independent and responsible from an early age. They get inspired to pursue their dreams and ambitions, seeing their mothers’ dedication and commitment.

Also check:

- 10 Lines on Working Mothers

250 Words Essay on Working Mothers

Introduction.

The concept of ‘working mothers’ has evolved significantly over the years, shifting from a socio-economic necessity to an emblem of women’s empowerment. This phenomenon has not only transformed the structure of the family but also influenced societal norms and perceptions.

The Evolution of Working Mothers

Historically, mothers were confined to the domestic sphere, responsible for nurturing the family. The feminist movement, however, challenged this traditional view, advocating for women’s rights to work and contribute economically. The rise of working mothers since then represents a significant shift in societal structures.

Impact on Family Dynamics

Working mothers have redefined family dynamics. They have proven that it is possible to raise children while pursuing a career, thereby debunking the myth of the ‘ideal’ mother being confined to the home. This shift has also led to a more equitable distribution of household chores, promoting gender equality.

Economic Implications

Working mothers contribute significantly to the economy. They not only support their families financially but also add to the national income. This economic independence further empowers them, allowing them to make decisions about their lives and families.

Challenges and Solutions

Despite the progress, working mothers face numerous challenges, including societal judgment, work-life balance issues, and lack of support. Addressing these issues requires societal change, flexible work policies, and robust support systems.

In conclusion, working mothers are a testament to the evolving roles of women in society. They symbolize resilience, strength, and the ability to balance multiple roles, thereby challenging traditional norms and contributing to societal progress.

500 Words Essay on Working Mothers

Working mothers are an integral part of society, demonstrating the epitome of multitasking by juggling personal and professional responsibilities. They are the pillars of their households and workplaces, contributing significantly to the economy while shaping the future generation.

Historically, societal norms and expectations confined women to domestic roles. However, the rise of feminism and women’s rights movements in the 20th century led to a paradigm shift, encouraging women to step out of their homes and pursue careers. Today, working mothers are prevalent across various sectors, from science and technology to arts and humanities.

The Balancing Act

The life of a working mother is a delicate balance between work and home. They often face the “double burden” of managing household chores and professional tasks, leading to a phenomenon known as “time poverty.” Despite these challenges, many working mothers successfully navigate this complex terrain through effective time management, family support, and flexible work arrangements.

Impact on Children and Society

The impact of working mothers on children and society is multifaceted. Children of working mothers often grow up to be independent, resilient, and empathetic, having witnessed their mothers’ hard work and dedication. Moreover, working mothers contribute to the economy, help reduce gender wage gaps, and challenge traditional gender roles, fostering a more equitable society.

The Role of Employers and Policy Makers

Employers and policy makers play a crucial role in facilitating the journey of working mothers. Workplaces need to offer flexible hours, remote work options, and family-friendly policies. On the policy front, governments should ensure equal pay, provide affordable childcare, and enforce maternity and paternity leave laws.

Working mothers are the backbone of a progressive society. They not only contribute to their family’s well-being and the economy, but also inspire the next generation to challenge societal norms and strive for equality. The journey of a working mother is challenging yet rewarding, filled with hurdles and triumphs. By acknowledging their efforts and providing them with the necessary support, we can create a society where both men and women can thrive in their personal and professional lives.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Problems of Working Mothers

- Essay on Shoes

- Essay on My Favourite Shoes

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

What research says about the kids of working moms

We spotlight research on working moms. Overall, the research suggests maternal employment has little impact on kid's behavior and academic achievement over the short term and may have long-term benefits.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Denise-Marie Ordway, The Journalist's Resource August 6, 2018

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/economics/working-mother-employment-research/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

Most American moms work outside the home. Nearly 70 percent of women with children under age 18 were in the labor force in 2015, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

In recent decades, as more mothers take paid positions, families, policymakers and scholars have wondered how the trend may impact children, especially during their early years. Many women, single parents in particular, must work because they either can’t afford to stay at home to raise their kids or the government agencies they rely on for assistance require them to be employed.

Work is also a choice for a lot of women. As more women in the United States complete college degrees — the percentage of women earning bachelor’s degrees skyrocketed between 1967 and 2015 — many have opted to leave their youngsters with a family member or daycare provider while they pursue careers and other professional interests.

Is this trend good or bad? Are kids with working moms different from kids whose moms are unemployed? Do they have more or fewer behavioral problems? Are their academic skills stronger or weaker? Let’s look at what the research says.

The good news: Overall, maternal employment seems to have a limited impact on children’s behavior and academic achievement over the short term. And there appear to be benefits in the long-term. A study published in 2018 finds that daughters raised by working moms are more likely to be employed as adults and have higher incomes.

Below, we’ve gathered a sampling of the academic research published or released on this topic in recent years. If you’re looking for workforce trend data, check out the U.S. Department of Labor’s website , which offers a variety of reports on women at work. A May 2018 report from the Pew Research Center, “7 Facts about U.S. Moms,” provides some useful context.

———–

“When Does Time Matter? Maternal Employment, Children’s Time With Parents, and Child Development” Hsin, Amy; Felfe, Christina. Demography , October 2014. DOI: 10.1007/s13524-014-0334-5.

Do working moms spend less time with their children? And if they do, does that hurt kids’ cognitive development? Amy Hsin from Queens College-City University of New York and Christina Felfe of the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland teamed up to investigate.

The gist of what they found: Mothers who work full-time do spend less time with their children, but they tend to trade quantity of time for better quality time. “On average, maternal work has no effect on time in activities that positively influence children’s development, but it reduces time in types of activities that may be detrimental to children’s development,” Hsin and Felfe explain. Each week, kids whose mothers work full-time spend 3.2 fewer hours engaged in “unstructured activities” — activities that don’t require children and parents to be actively engaged and speaking to one another — compared to kids whose moms are unemployed.

The researchers also find that children with college-educated mothers spend more time on educational activities as well as “structured” activities, which require kids to be actively engaged with their parents. “For example, college-educated mothers and their partners spend 4.9 hours and 2.5 hours per week, respectively, engaged in educational activities with their children; by comparison, mothers with less than [a] high school diploma and their partners spend only 3.3 hours and 1.7 hours per week in educational activities, respectively,” according to the study.

Maternal employment, generally speaking, appears to have a positive effect on children’s cognitive development. “When comparing the effect of maternal employment on child outcomes between stay-at-home mothers and mothers who work full-time, we see that the reduction in unstructured time resulting from full-time employment amounts to an improvement in children’s cognitive development of 0.03 to 0.04 SD [standard deviation],” the authors write. For children under age 6, the improvement is larger.

“Learning from Mum: Cross-National Evidence Linking Maternal Employment and Adult Children’s Outcomes” McGinn, Kathleen L.; Castro, Mayra Ruiz; Lingo, Elizabeth Long. Work, Employment and Society , April 2018. DOI: 10.1177/0950017018760167.

These researchers analyzed data from two surveys conducted across 29 countries to examine how men and women had been influenced by their mother’s work status. The main takeaway: Daughters raised by working mothers are more likely to have jobs as adults — and those who have jobs are more likely to supervise others, work longer hours and earn higher incomes.

There doesn’t appear to be a link between maternal employment and employment for sons, according to the study. However, men whose mothers worked while they were growing up spend about 50 minutes more caring for family members each week than men whose moms didn’t work.

The study, led by Kathleen L. McGinn of Harvard Business School , notes that these outcomes are “due at least in part to employed mothers’ conveyance of egalitarian gender attitudes and life skills for managing employment and domestic responsibilities simultaneously. Family-of-origin social class matters: women’s likelihood of employment rises with maternal employment across the socio-economic spectrum, but higher incomes and supervisory responsibility accrue primarily to women raised by mothers with more education and higher skill jobs.”

“Increasing Maternal Employment Influences Child Overweight/Obesity Among Ethnically Diverse Families” Ettinger, Anna K.; Riley, Anne W.; Price, Carmel E. Journal of Family Issues , July 2018. DOI: 10.1177/0192513X18760968.

This study looks at how maternal employment affects the weight status of Black and Latino children from low-income families in Boston, Chicago and San Antonio. The researchers find that an increase in a mother’s “work intensity” — for example, when a mother transitions from being unemployed to working or switches from part-time to full-time work — increases the odds that her child will be overweight or obese.

Kids whose mothers increased their work schedules during the children’s first few years of life were more likely to have a weight problem. “Children of mothers who increased their employment status during children’s preschool years had over 2.6 times the odds of being overweight/obese at 7 to 11 years of age compared with children of nonworking mothers,” the authors write. They also write that their results “suggest that changing work schedules and increasing work hours over time may be more disruptive to family environments and child weight than maintaining constant levels of employment over time (whether that is not working at all or working full-time).”

The researchers note that within their sample of 602 children, having consistent family routines such as mealtimes and bedtimes were associated with a 61 percent reduction in the odds of being overweight or obese. They also note that youth whose parents live together, whether married or not, tended to have lower odds of being overweight or obese than children living with single mothers.

“The Effect of Maternal Employment on Children’s Academic Performance” Dunifon, Rachel; Hansen, Anne Toft; Nicholson, Sean; Nielsen, Lisbeth Palmhøj. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 19364, August 2013.

Rachel Dunifon , the interim dean of Cornell University’s College of Human Ecology, led this study, which explores whether maternal employment improves children’s academic achievement. Dunifon and her colleagues analyze a data set for 135,000 children who were born in Denmark between 1987 and 1992 and followed through the ninth grade.

A key finding: Danish children whose mothers worked during their childhood had higher grade-point averages at age 15 than children whose mothers did not work. And children whose mothers worked between 10 and 19 hours a week had better grades than kids whose mothers worked full-time or only a few hours per week. “The child of a woman who worked between 10 and 19 hours per week while her child was under the age of four is predicted to have a GPA that is 2.6 percent higher than an otherwise similar child whose mother did not work at all,” the authors write.

The researchers suggest their paper “presents evidence of a positive causal linkage between maternal work hours and the GPA of Danish teens. These associations are strongest when mothers work part-time, and among more advantaged mothers, and are not accounted for by mothers’ earnings.”

“Maternal Work Early in the Lives of Children and Its Distal Associations with Achievement and Behavior Problems: A Meta-Analysis” Lucas-Thompson, Rachel G.; Goldberg, Wendy A.; Prause, JoAnn. Psychological Bulletin , November 2010. DOI: 10.1037/a0020875.

This is an analysis of 69 studies that, over the span of five decades, look at the relationship between maternal employment during children’s early years and children’s behavior and academic performance later in life. Overall, the analysis suggests that early maternal employment is not commonly associated with lower academic performance or behavior problems.

The analysis did, however, find differences when comparing different types of families. Early maternal employment was associated with “positive outcomes (i.e., increased achievement and decreased behavior problems) for majority one-parent samples,” explain the three researchers, Rachel G. Lucas-Thompson , now an assistant professor at Colorado State University, and Wendy A. Goldberg and JoAnn Prause of the University of California, Irvine. Early maternal employment was associated with lower achievement within two-parent families and increased behavior problems among study samples comprised of a mix of one- and two-parent families.

The researchers offer this explanation: “The results of this meta-analysis suggest that early maternal employment in sole-provider families may bolster children’s achievement and buffer against problem behaviors, perhaps because of the added financial security and health benefits that accompany employment, as well as improved food, clothing, and shelter because of increased income and the psychological importance of having a role model for achievement and responsible behavior. In contrast, early maternal employment may be detrimental for the behavior of children in two-parent families if the increases in family income do not offset the challenges introduced by maternal employment during children’s early years of life.”

There were differences based on household income as well. For families receiving welfare, the researchers found a link between maternal employment and increased student achievement. For middle- and upper-class families, maternal employment was associated with lower achievement.

The researchers note that they tried to gauge how child-care quality might influence these results. But there weren’t enough studies to allow for a detailed analysis.

Family separation: How does it affect children?

Maternity leave and children’s cognitive and behavioral development

How to tell good research from flawed research: 13 questions journalists should ask

About The Author

Denise-Marie Ordway

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

The Harried Life of the Working Mother

Women now make up almost half of the U.S. labor force, up from 38% in 1970. This nearly forty-year trend has been fueled by a broad public consensus about the changing role of women in society. A solid majority of Americans (75%) reject the idea that women should return to their traditional roles in society, and most believe that both husband and wife should contribute to the family income.

But in spite of these long-term changes in behaviors and attitudes, many women remain conflicted about the competing roles they play at work and at home. Working mothers in particular are ambivalent about whether full-time work is the best thing for them or their children; they feel the tug of family much more acutely than do working fathers. As a result, most working mothers find themselves in a situation that they say is less than ideal.

They’re also more likely than either at-home moms or working dads to feel as if there just isn’t enough time in the day. Four-in-ten say they always feel rushed, compared with a quarter of the other two groups. But despite these pressures and conflicts, working moms, overall, are as likely as at-home moms and working dads to say they’re happy with their lives.

Whether women work outside the home or not, family responsibilities have a clear impact on the key life choices they make. Roughly three-in-ten women who are not currently employed (27%) say family duties keep them from working. And family appears to be one of the key reasons that many do not break through the “glass ceiling” to the top ranks of management — that’s the view, anyway, of about a third of the public.

Working Mothers

According to data collected by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 59% of women now work or are actively seeking employment. An even higher percentage of women with children ages 17 or younger (66%) work either full or part time. Among those working mothers, most (74%) work full time while 26% work part time.

A survey taken this summer by the Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project asked working mothers whether they would prefer to work full time or part time . A strong majority of all working mothers (62%) say they would prefer to work part time. Only 37% of working moms would prefer to work full time. Working fathers have a much different perspective. An overwhelming majority (79%) say they prefer full-time work. Only one-in-five say they would choose part-time work.

These findings echo the results of a 2007 Pew Research Center survey in which a majority of working mothers (60%) said the ideal situation for them would be to work part time . This represented a significant increase from 10 years earlier when only 48% of working mothers had said the same.

Women’s Growing Presence in the Workforce

The percentage of women working or actively seeking employment grew steadily from the 1950s onward, peaking in 2000. As an overall share of the labor force, women today comprise 47%. 1 The growth in the share of women in the workforce has leveled off in recent years, just as women’s participation rate stopped climbing. Nonetheless, the fact remains that women have transformed the American workplace over the past 50 years, and in so doing have created a series of conflicts and challenges for today’s working women that have proven to be difficult to resolve.

Public Views on the Changing Role of Women

As women have taken a more active role in the labor force, public opinion has become increasingly supportive of this new reality. The Pew Research Center for the People & the Press has been tracking public attitudes on social and political values , including the changing role of women, for the past 20 years. In 1987, 30% of Americans said women should return to their traditional roles in society, while 66% disagreed with this statement. Today, only 19% agree that women should return to their traditional roles while 75% disagree.

Women and men are equally likely to reject the notion that women should return to their traditional roles. Young people are among the most progressive on this issue. Among those under age 30, 84% disagree with the idea that women should go back to a more traditional role.

Further evidence of the changing attitudes about family and the role of women can be seen in another item included in the Pew Research Center’s values surveys. Seven-in-ten Americans (71%) agree with the statement “I have old-fashioned values about family and marriage.” While still a strong majority, this is down significantly from 87% who held this view in 1987. Again men and women are in agreement on this issue, and young people express the least conservative views: 61% of those under age 30 say they have old-fashioned values about family and marriage.

Looking more specifically at the question of women and the workplace, data from the General Social Survey shows how attitudes changed from the late 1980s to the turn of the century. When asked whether they agreed or disagreed that both the husband and the wife should contribute to the household income, the percent of Americans who strongly agreed grew steadily from 1988 to 2002. In 1988 only 15% strongly agreed that both spouses should contribute to the household income, by 2002 29% strongly agreed (another 28% agreed but not strongly).

Even as society has become more accepting of women’s role in the workforce, attitudes about a special class of female workers — namely mothers of young children — have changed very little. In 1994 and again in 2002 the General Social Survey asked whether women should work outside the home under certain circumstances. In both years, strong majorities said a woman who is married but has not yet had children should work full time.

However, only 10% in 1994 and 11% in 2002 said a woman with a young child should work full time. Respondents were more accepting of full-time work for a woman whose youngest child had started school. However, even then pluralities in 1994 and 2002 said part-time work would be preferable under those circumstances.

Pew Research Center data shows that strong concern over the impact of day care on the nation’s children has persisted over time. In 1987, 68% of the public agreed that too many children are being raised in day care centers these days. In 2003, 72% agreed with this statement.

Mothers themselves are particularly concerned about this issue. In the 2003 Pew Research Center survey 50% of mothers with children under age 5 completely agreed that too many children are being raised in day care centers today. This compared with 36% among the general public.

The Challenges of Today’s Reality

Herein lies the dilemma: women are a permanent part of the workforce, society has endorsed this historic change, but public opinion hasn’t yet fully come to terms with the tradeoffs inherent in working and raising young children. Large majorities of Americans believe that the ideal situation for both mother and child is that a mother with young children does not hold a full-time job. Only 12% of the public says what’s best for a young child is that their mother works full time. Four-in-ten say the ideal situation for a young child is a mother who works part time, and 42% say what’s best is if the mother doesn’t work at all.

When it comes to what’s best for the mother, the results are strikingly similar: 12% say the ideal situation for mothers with young children is to work full time, 44% say part-time work is ideal and 38% say it’s best if the mother doesn’t work at all. In perhaps the most powerful evidence of the cross-pressures that many working mothers feel every day, only 13% of moms who work full time say having a mother who works full time is the ideal situation for a young child.

Men and women agree that a full-time working mother is not what’s best for a young child. However, while most dads (54%) say the ideal situation for a child is to have a mom who doesn’t work at all, a plurality of moms (49%) say having a mom who works part time is what would benefit a child most.

Why Some Women Don’t Work?

Roughly four-in-ten women, including 34% of women with children age 17 or younger, do not work outside the home. According to a 2007 Pew Research Center survey, these at-home moms are slightly younger, on average, than moms who work full or part time. They have less formal education and lower household incomes than working mothers. Only 21% of at-home moms are college graduates, compared with 34% of working moms. And, while 37% of at-home moms report an annual household income of less than $30,000, only 20% of working moms fall into this income category. 2

In addition, at-home moms are more likely than working moms to be Hispanic. In the 2007 survey, 27% of the at-home moms surveyed were Hispanic. This compares with 13% of working moms. African American women are more heavily concentrated among working mothers: 18% of mothers who work full or part time are black, while only 9% of those who don’t work are black.

When asked about the impact the rise in working mothers has had on society, at-home moms have a more critical view than do working moms. A plurality of at-home moms (44%) say the increase in working mothers with young children has been bad for society. Only 22% think this trend has been good for society, and 31% say it hasn’t made much difference. Working mothers are more evenly split on this question: 34% say the trend toward more mothers with young children working has been good for society, 34% say it has been bad for society and 31% say it hasn’t had much of an impact.

At-home moms and working moms also differ in their self-evaluations. When asked to rate the job they are doing as parents on a scale of 0 to 10 (with 10 being the highest), 43% of at-home moms give themselves either a 9 or a 10. Moms who work either full time or part time are harder on themselves — only 33% give themselves a 9 or 10.

The reasons women don’t work are somewhat different from the reasons men don’t work, and for women family is a much more important factor. Among those who are not working and not retired, the most important reasons men give for being unemployed are that they’ve looked and can’t find a job (51% say this is a “big reason”) or that they’ve been laid off or lost their job (37%).

Women who are not working and are not retired are less likely than men to say that being unable to find a job or losing a job are major reasons why they are not working. While 34% of women who are not employed say they are not working because they can’t find a job, more than a quarter (27%) say family or childcare responsibilities is a major reason why they are not working. Only 3% of men who are not employed say this is a major reason they are not working. In addition, women are more than four times as likely as men to say they are not working because their spouse or family doesn’t want them to work (14% vs. 3%).

The Glass Ceiling: Is Family a Factor?

A 2008 Pew Research Center survey explored the reasons why, in spite of their growing presence in the labor force, so few women have risen to the top ranks of American business and politics . Respondents were asked to evaluate a series of potential reasons why there are not more women in top level business positions and high political offices. With regard to business, what’s holding women back, according to the public, are the “old-boy network” and the fact that women haven’t had access to corporate America long enough to rise to the top. Many respondents also said that women’s family responsibilities don’t leave time for running a major corporation. Women themselves were somewhat more likely than men to say this is a major reason why so few top level business positions are held by women (37% vs. 32%).

When asked why there are not more women in high political offices, more than a quarter of the public (27%) said a major reason for this is that women’s responsibilities to family don’t leave time for politics. Other important reasons included that Americans simply aren’t ready to elect a woman to higher office (51% said this is a major reason), women who are active in party politics are held back by men (43%), and women are discriminated against in all areas of life including politics (38%). It’s worth noting that for both business and politics, very few people said that a lack of ability, toughness or experience were major reasons why more women haven’t gotten ahead in these fields.

The Day-to-Day Lives of Working Moms and Dads

What sort of impact does working and raising a family have on the day-to-day lives of mothers? And do working fathers experience the same stresses and strains?

One thing is quite clear — working mothers feel rushed. In a 2005 Pew Research Center survey, respondents were asked how they felt about their time — did they always feel rushed, only sometimes feel rushed or almost never feel rushed. Overall, 24% of the public said they always feel rushed. But working mothers’ lives are much more harried than the average American’s. Four-in-ten working mothers with children under age 18 said they always feel rushed, and another 52% said they sometimes feel rushed. By comparison, 26% of mothers who don’t work outside of the home said they always feel rushed as did 25% of working fathers. Whether mothers worked part time or full time didn’t make a difference: 41% of moms who work full time and 40% of those who work part time said they are constantly feeling rushed.

The 2008 Pew Research Center survey cited above included a question about the level of stress people experience in their daily lives. Relatively few Americans are immune from stress. Nearly three quarters say they experience stress sometimes (36%) or frequently (36%). Another 21% rarely experience stress and 5% say they never do. Women report experiencing somewhat more stress than men, and mothers have higher stress levels than fathers. For mothers, working outside the home does not seem to be correlated with stress. Mothers who stay at home are about as likely to say they frequently feel stressed as those who work full or part time. Working fathers are less likely than working mothers to feel stressed. In fact, 26% of fathers who work either full or part time and have children under age 18 say they rarely or never feel stressed. This compares with only 14% of working mothers.

The good news for working moms is that, although their lives may be chaotic, they are just as happy overall as at-home moms and working dads. In the 2008 Pew Research Center survey, 36% of working moms said they were very happy with their lives. An equal proportion of at-home moms said they were very happy, and 38% of working dads said the same. Similarly, working moms are just as likely as moms who don’t work outside the home to say they are very satisfied with their family life (78% of working moms vs. 75% of at-home moms).

One group of women who are less happy and less satisfied with their family lives is single moms with children under age 18. Only 27% say they are very happy compared with 41% of married moms, and 63% are very satisfied with their family life vs. 85% of moms who are married.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Undoubtedly working mothers will continue to juggle their many responsibilities at work and at home. Most would prefer to work part time but the reality is that relatively few actually have the opportunity to do so. Furthermore, the demands of a tighter labor market may make it even more difficult for women to find jobs that allow for part-time work or flexible schedules.

Working fathers are also juggling more these days than they did in the past. As women have gone into the labor force in greater numbers, men have assumed more responsibilities at home. Research shows that married fathers now spend roughly twice as much time caring for children and doing housework as they did in the 1960s. Women are now spending less time on housework than they were in the 1960s, however they still bear much more of the burden for both housework and child care than do fathers. 3

For their part, most fathers are content to work full time and few seem to feel conflicted over their competing roles at work and at home. Working women are left to wrestle with the competing demands of work and family.

- This figure is based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Current Population Survey, a household survey which is designed to reflect the entire civilian noninstitutional population. An alternative data source is the BLS Establishment Survey, a survey of employers from private nonfarm businesses as well as federal, state, and local government entities. According to the BLS Establishment Survey, women comprise 49% of the private, nonfarm labor force. ↩

- For purposes of this analysis, “at-home moms” are women who have children under age 18 and do not work. This is slightly different from the Census designation which defines “stay at home” as a mother who has a child under age 15 and stays out of the labor force to care for home and family while her spouse works. ↩

- See Suzanne Bianchi, John Robinson and Melissa Milkie, “Changing Rhythms of American Family Life,” New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2006. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Business & Workplace

- Economics, Work & Gender

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Gender & Work

- Gender Roles

- Household Structure & Family Roles

Half of Latinas Say Hispanic Women’s Situation Has Improved in the Past Decade and Expect More Gains

A majority of latinas feel pressure to support their families or to succeed at work, a look at small businesses in the u.s., majorities of adults see decline of union membership as bad for the u.s. and working people, a look at black-owned businesses in the u.s., most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

- Becoming A Confident Parent

They do it all: Working moms share 10 real-time eternal struggles and how they try to overcome them

Working mothers live with the constant guilt of not being available for their little ones and make every effort to balance work and home. Here are some real struggles faced by most moms who go to work

A PR professional working in a multinational company and a mother to a three-year-old, Mansi has a lot on her plate. She sometimes feels like she's in a race that never seems to end. She leaves early after preparing the meals for the day and drops her daughter at her parent's home. Her profession demands her to be available to clients most of the day; there are times when she's to work late and her heart aches to come home and see her daughter already asleep.

Mothers who are employed full-time always grapple with the guilt that they are not giving enough time to their children. Being a mother is one of the hardest yet fulfilling jobs and when coupled with a full-fledged professional life, a working mom has a daunting task to fulfill. Managing the kids, taking care of the family and juggling the responsibilities of the home along with a career, work commitments and deadlines put a lot of pressure on the working mom.

However, working mothers have the advantage of having a life outside the confines of their homes and a chance to build their dreams and careers. According to a study conducted by Kathleen L McGinn at the Harvard Business School along with Mayra Ruiz Castro and Elizabeth Long Lingo, having a working mother improves children's prospects. Seeing mothers work both inside and outside the home allows children to understand that contributions at home and work are equally valuable, the study says.

Nonetheless, the struggles of a working mom are very real.

Here's taking a look.

1. The morning rush: Mornings can be extremely crazy for working moms. As a teacher who leaves behind her young kid at home, Shalini laments,

"The hardest part of my day is to wake my daughter early so that I can stick to my schedule and not be late for work. Getting ready for work while preparing breakfast, doing other household chores and getting the child ready for daycare/school is a formidable task."

2. Leaving behind an unwell child: There is nothing more heart-wrenching than to leave a sick child at home and go to work. I remember a friend breaking down at work because she had left her son, who was down with fever, at home. The guilt is just unbearable, and very often mothers of sick children take leave from work so that they can care for the little one. What this does is that it makes it difficult for the working mom to take an off when she is in need of rest.

3. Finding quality time: There are times when all you want to do is spend some quiet time bonding with your little one, maybe playing a board game or baking cookies together, or just listening to her talk about her day. Unfortunately, for a working mother, this is a luxury that takes a lot of effort and planning – even weekends are busy with sorting household chores and on weeknights, she may too tired or distracted to spend quality time with the child.

4. Having to make difficult choices: You put extra effort and time into that presentation so that your meeting goes off well the next morning. And to your horror, your child's school diary shows that there's a PTA meeting scheduled at the same time. You cannot ask your spouse because he is traveling. Prioritizing and choosing between work and child can be one of the unending dilemmas for mothers. Is attending the conference more important or helping the child learn for exams? This persistent, daily sorting of priorities can make life tough for even the most hardened time managers.

5. The elusive me-time: In the pursuit to handle everything, working moms often neglect taking care of themselves. They skip breakfast, eat unhealthy lunches, don't pay too much attention to grooming. They don't take time out for themselves because of the guilt of leaving their child behind. An uninterrupted movie, reading a book or a quiet evening spent just relaxing on the beach are things she may not be able to do. As Meenakshi, a working mom puts it,

"Sometimes, the pressure is so much that I wish I could just run off to an island, but then I realize that is being just outright mean and selfish."

6. Missing out on important milestones: "I missed seeing my little one take her first step. What I would have given to be there," says an HR manager and mother of a 13-month- old. Missing out on the little joys of watching your baby grow and reach important milestones makes the working mom feel miserable. It's worse when you have to hear it from others, while they describe the precise moment when your bundle of joy pulled herself up and started to wobble towards her first step.

7. Running on limited energy: You come home from work and are totally exhausted. That's when your children demand attention since they haven't seen you all day. They want to do something constructive with you, while you are still thinking about the dinner you can cook up in a jiffy! Sound familiar? It's an eternal struggle for working moms. You could read them a story or play checkers before going to bed, but seriously, who has the energy?

8. Daycare dilemma: Leave in a daycare center or get a nanny? Drop-in at grandma's home or enroll in a creche? For a mom with a small child, making the right decision is hard. While a nanny ensures the child is in familiar surroundings, a working mom will always be distracted about how the nanny is looking after her precious one. A creche means worrying about the quality of care.

9. Struggling to make it to playdates: This is a complaint that children with two working parents may have, and it is usually the mother who blames herself for not being available. It's worse when all your children's friends go for playdates, and your little ones are irritated that they never get to go. Between finishing deadlines, preparing meals for the family and helping with homework, where's the time?

10. Mommy guilt: The biggest challenge is to deal with the guilt that every working mother has. The guilt of leaving the child behind, spending less time with her and missing out on many moments of mothering. This underlying guilt always makes the working mother put herself last in the scheme of things.

Working moms are role models for not only the other women but also for their children and the younger generation. It's important to understand that it may get tough trying to make all things work and there'll be days when you feel like a messed-up underperformer. But be kind to yourself and believe that, in the long run, it'll all work out.

Anonymous Oct 18, 2021

Comment Flag

Abusive content

Inappropriate content

Cancel Update

Related Topics See All

More for you.

Explore more articles and videos on parenting

Pre-teen to Parent • 4 Mins Read • 7K Views

This is how you can be open about menstrual hygiene with your teenage daughter

It is high time we broke the silence around menstruation, which denies many young girls access to menstrual health and hygiene. Parents, let's reassure your daughter that she has nothing to be ashamed of

Parent • 8 Mins Read • 5K Views

Why Self-Care Is Critical For A Parent's Well-Being. Time To Get Some Me Time

Parenting can be challenging and channelise all your energy. But caring for your children doesn't mean you neglect your own well-being. That can be harmful in the long run, says Dr Jamuna Rajeswaran

Parent • 13 Mins Read • 665 Views

Has parenting taken the ‘life’ out of your love life? Here is what you can do to rekindle the magic

Hey parent, are you still in love? Did this question get you thinking? Well, read on to know why your spouse needs all your attention while you bask in your parenting glory

- Communities

Join a community to interact with like-minded parents and share your thoughts on parenting

2.5K members • 53 Discussions

Curiosity, tantrums and what not!

1.9K members • 37 Discussions

The Active and Enthusiastic Middle Years

11-18 Years

1.8K members • 62 Discussions

From Self-consciousness to Self-confidence

Just for Parents

4K members • 152 Discussions

A 'ME' space to just BE!

Discussions Topics

Share your thoughts, parenting tips, activity ideas and more

Hobbies and Entertainment

New member introduction.

Family Fun Challenges and Activities

- Gadget Free Hour

- Discussions

Share your thoughts, tips, activity ideas and more on parenting

Mothers Day Contest - One Habit I Got From Mom | May 2024

Joy of celebration, corporal punishment, best schools in ahmedabad, could someone recommend the top preschool in mumbai's borivali west area.

A compilation of the most-read, liked and commented stories on parenting

Beat The Crazy Morning Rush By Making A Few Small Changes And Take Control Of Your Day

12 Mins Read • 24.4K Views

How to Become a More Organised Parent

7 Mins Read • 2.8K Views

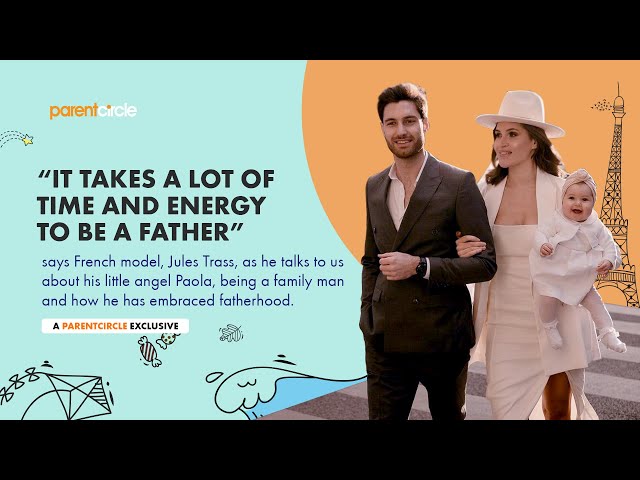

'It takes a lot of time and energy to be a father': French model Jules Trass shares his parenting journey

8.17 Mins • 738 Views

Parental Burnout: How To Cope With It

9 Mins Read • 5K Views

Is It Time To Stop Bashing The Working Mother?

12 Mins Read • 13.7K Views

How I Helped My Child Cope With My Injury

9 Mins Read • 2.9K Views

Top Searches

- Notifications

- Saved Stories

- Parents of India

- Ask The Expert

- Community New

- Community Guideline

- Community Help

- The Dot Learning Circle

- Press Releases

- Terms of use

- Sign In Sign UP

We use cookies to allow us to better understand how the site is used. By continuing to use this site, you consent to this policy. Click to learn more

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

An Exploratory Study of Challenges Faced by Working Mothers in India and Their Expectations from Organizations

2019, Global Business Review

Working mothers worldwide find it hard to deal with expectations about their maternal responsibilities and work. The challenges faced by women across nations are perceived to be similar in nature. However, the known diversity in terms of culture, political scenario, educational framework, economic situation, legal policies and employment guidelines are unavoidable factors which may directly impact the challenges faced by women in their respective workplace. This research, therefore, attempts to identify the challenges faced by working mothers in India in their careers including different industrial sectors in the present scenario. A mix of qualitative and quantitative techniques is used for data collection. On the basis of in-depth interviews, grounded theory approach and exploratory factor analysis, three broad categories of challenges faced by working Indian mothers are identified. Post the empirical identification of perceived career barriers for working mothers, organizational i...

Related Papers

Sudhansubala Sahu

Motherhood in India has been understood primarily by placing mothers in the domestic space. A mother is constructed as a protector and the complete caregiver of her children. But there have been significant changes in the status of Indian women recently. In the 21st century, with suitable qualifications and employment opportunities, women have the choice to be economically independent and career-driven, which has a profound impact on their roles and responsibilities as protectors and caregivers in the home. It is essential to study and document how women in this generation have started to redefine their roles and negotiate what a mother's duties are at home. This study aims to make a systematic inquiry to understand the issues and challenges faced by employed mothers in everyday life and how they balance their career and childcare activities. Researchers investigate this through a qualitative study on mothers employed in different types of professions in the city of Kolkata. Dat...

International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health

Background: Females contribute to 48.5% of population of India. Shouldering dual responsibilities of house and work can eventually take toll on women’s physical and mental health. The work and family commitments are likely to be influenced by parity, duration of breastfeeding, work environment and social support. This study is conducted to assess the stress levels among working professional mothers and their associated risk factors.Methods: It was a cross sectional study conducted in working professional mothers of India. Data was collected using structured questionnaire and perceived stress scale (PSS-4) for assessing stress. The form was made available on internet so as to approach wide spectrum of professionally working mothers.Results: Moderate to severe stress was perceived by 63.04% women. Severity of stress increases with shift duties (p=0.05), lack of family support (p=0.08) and inability to exclusively breastfeed child for 6 months (p=0.09). Only 1/3rd (31.88%) working moth...

Mehrdad Azarbarzin

Sanghamitra Buddhapriya

anju dusseja

International Journal of Applied Research

Sivakumar I.

The research has investigated working mothers' roles within the context of work-family and has reported on such inter-role conflict between women's health issues and parenting through secondary data. Studies on the impact of employed mothers on their children have yielded conflicting results, some positive and some negative. It observed that the children of working mothers are socially more participative than children of non-working mothers. The study found children of working mothers to be less stable, get easily upset and affected by feelings. The study also says employed mothers as careless and slightly emotionally unstable in the early years but independent during later years as compared to the children of unemployed mothers. In all these worries the woman has no time left to look after her health. A large number of working mothers complain of frequent headaches, back pain, circulatory disorders, fatigue, emotional and mental disorders.

Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers

A broad review of existing literature on barriers to women's career advancement suggests that one of the most important reasons inhibiting women's rise to the top positions in management is the work-life conflict that women professionals experience because of their strong commitment to family responsibilities. The primary objective of this study is to understand the impact of family responsibilities on the career decisions of women professionals and also to find out the type of work-life support they would require from their employers to balance their work and life in a better manner. The study is conducted with 121 women professionals working in government services, public sector, private sector, and in NGOs across different levels. The perception of women professionals regarding the barriers against their career advancement is studied. The impact of demographic factors like managerial level, marital status, and family structure on all the above-mentioned issues are also an...

Trends in Psychology

Cesar Augusto Piccinini

We aimed to investigate the experience of primiparous mothers with established careers in relation to motherhood and their work, from pregnancy to the end of maternity leave. Three public employees participated, answering interviews. Qualitative content analysis showed that the experiences of participants were similar in several aspects. Repercussions of work in the experience of motherhood were identifi ed from pregnancy, considering concerns regarding changes and reconciliation of maternal and professional demands. Feelings of insecurity and ambivalence were also present when babies entered daycare center and women returned to work. Since the pregnancy, changes aiming at managing the demands of work and motherhood were identifi ed. Family, social and organizational support received by the participants contributed to this management. Nevertheless, a sense of overload by the accumulation of activities after the baby’s entrance in daycare center and the mother’s return to work were evidenced, which corroborates literature on the subject.

Editor IJIRMF

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities

Sucharita Sarkar

Situated in the context of the coronavirus pandemic, this paper begins by looking at the recent advertisement by Amul praising mothers who are ‘working from home’ and ‘working for home’ during the lockdown, with an accompanying cartoon visualizing the iconic Amul girl sitting beside her mother who is working on her laptop while keeping an eye on her daughter; in a juxtaposed cartoon, the mother is cooking in the kitchen while simultaneously scrolling through her smartphone. Amongst my groups of women friends, the advertisement elicited strong and contradictory responses: ranging from approval of the appreciation for maternal work to disapproval at the missing father. In order to critique this advertisement, I would use the lens of Motherhood Studies, an emerging area of scholarship that is inherently interdisciplinary. Reading the advertisement as a cultural text, I will attempt to locate the maternal stereotypes embedded in it: the merging of the stay-at-home mother and the working...

RELATED PAPERS

Nahuel Zalazar MUSICA

Revista Digital Hilario, 26

Irina Podgorny

Madeleine Akrich

Thierry Meynard

Parametric study of the thermal performance of a typical administrative building in the six thermal zones according to the RTCM, using TRNSYS

abdelghafour lamrani

University of Torbat Heydarieh

Saffron Agronomy and Technology journal

Tatiane de Souza Lélis Siqueira

Earth and Planetary Science Letters

Paul Glover

2008 6th International Symposium on Modeling and Optimization in Mobile, Ad Hoc, and Wireless Networks and Workshops

Özlem Durmaz Incel

Physical Review B

American Journal of Industrial and Business Management

mujahid hussain

British journal of …

Luis Henrique Pereira Martins

International Journal of Technology and Design Education

Helen Brink

African Journal of Food Science

Ekpeno Ukpong

Maß&Gewicht Zeitschrift für Metrologie

Ludwig Ramacher

Laura estela arias ortiz

Food Research International

Dominika A Maison

Taller. Revista de Sociedad, Cultura y Politica (1996-2006)

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution

Paul Skelton

Flora Ferati

Zeitschrift f�r Physik A Atomic Nuclei

Thomas Massey

Veterinary Record

Kathy Gross

Tropical journal of obstetrics and gynaecology

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- relationships

Common challenges faced by working mothers and ways to overcome them

Visual Stories

- Isaac E. Sabat 3 ,

- Alex P. Lindsey 3 ,

- Eden B. King 3 &

- Kristen P. Jones 3

2204 Accesses

8 Citations

Working mothers face different sets of challenges with regards to social identity, stigmatization, and discrimination within each stage of the employment cycle, from differential hiring practices, unequal career advancement opportunities, ineffective retention efforts, and inaccessible work-family supportive policies (Jones et al. in The Psychology for Business Success. Praeger, Westport, CT, 2013 ). Not only do these inequalities have negative effects on women, but they can also have a detrimental impact on organizations as a whole. In this chapter, we review several theoretical and empirical studies pertaining to the challenges faced by women throughout their work-motherhood transitions. We then offer strategies that organizations, mothers, and allies can use to effectively improve the workplace experiences of pregnant women and mothers. This chapter will specifically contribute to the existing literature by drawing on identity management and ally research from other domains to suggest additional strategies that female targets and supportive coworkers can engage into help remediate these negative workplace outcomes. Finally, we highlight future research directions aimed at testing the effectiveness of these and other remediation strategies, as well as the methodological challenges and solutions to those challenges associated with this important research domain. We call upon researchers to develop more theory-driven, empirically tested intervention strategies that utilize all participants in this fight to end gender inequality in the workplace.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Women of Color in the Workplace: Supports, Barriers, and Interventions

Exploring the Double Jeopardy Effect: The Importance of Gender and Race in Work–Family Research

Unfinished Business: Advancing Workplace Gender Equity Through Complex Systems Strategies Supporting Work/Family Dynamics

Allen, T. D. (2001). Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58 , 414–435. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2000.1774

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, D. J., Binder, M., & Krause, K. (2003). The motherhood wage penalty revisited: Experience, heterogeneity, work effort, and work-schedule flexibility. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 56 , 273–294.

Aronson, E., Wilson, T. D., & Akert, R. M. (2010). Social psychology (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Asch, S. E. (1946). Forming impressions of personality. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 41 , 258–290. doi: 10.1037/h0055756

Ashburn-Nardo, L., Morris, K. A., & Goodwin, S. A. (2008). The Confronting Prejudiced Responses (CPR) Model: Applying CPR in organizations. Academy of Management: Learning and Education, 7 , 332–342. doi: 10.5465/AMLE.2008.34251671

Bailyn, L. (1993). Breaking the mold: Women, men, and time in the new corporate world . New York: Free Press.

Berger, J., Fisek, H., Norman, R., & Zelditch, M, Jr. (1977). Status characteristics and social interaction . New York: Elsevier.

Biernat, M., Crosby, F., & Williams, J. (Eds.) (2004). The maternal wall. Research and policy perspectives on discrimination against mothers [Special Issue]. Journal of Social Issues, 60 .

Brooks, A. K., & Edwards, K. (2009). Allies in the workplace: Including LGBT in HRD. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 11 , 136–149. doi: 10.1177/1523422308328500

Buck, D. M., & Plant, E. A. (2011). Interorientation interactions and impressions: Does the timing of disclosure of sexual orientation matter? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47 , 333–342.

Budig, M. J., & England, P. (2001). The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review, 66 , 204–225.

Butts, M. M., Casper, W. J., & Yang, T. S. (2012). How important are work–family support policies? A meta-analytic investigation of their effects on employee outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98 , 1–25. doi: 10.1037/a0030389

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Catalyst (2008). Advancing women leaders: The connection between women board directors and women corporate officers . New York: Catalyst.

Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112 , 1297–1338.

Crittenden, A. (2001). The price of motherhood: Why the most important job in the world is still the least valued . New York: Metropolitan Books.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2004). When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn’t cut the ice. Journal of Social Issues, 60 , 701–718. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00381.x

Czopp, A. M., Monteith, M. J., & Mark, A. Y. (2006). Standing up for a change: Reducing bias through interpersonal confrontation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90 , 784–803. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.784

Dovidio, J. F., & Hebl, M. R. (2005). Discrimination at the level of the individual: Cognitive and affective factors. Discrimination at work: The psychological and organizational bases, 11–35.

Eagly, A. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation . Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Eagly, A. H. (1997). Sex differences in social behavior: Comparing social role theory and evolutionary psychology. American Psychologist, 52 , 1380–1383. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1380.b

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (1991). Gender and the emergence of leaders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60 , 685–710. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.5.685

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109 , 573–598. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., & Diekman, A. B. (2000). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. The developmental social psychology of gender, 123–174.

Epstein, C., Seron, C., Oglensky, B., & Saute, R. (1999). The part time paradox: Time norms, professional lives, family and gender . New York: Routledge.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2011). Charge statistics FY 1997 through FY 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2016, from http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/charges.cfm .

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fiedler, K., Messner, C., & Bluemke, M. (2006). Unresolved problems with the “I”, the “A”, and the “T”: A logical and psychometric critique of the Implicit Association Test (IAT). European Review of Social Psychology, 17 , 74–147. doi: 10.1080/10463280600681248

Firth, M. (1982). Sex discrimination in job opportunities for women. Sex Roles, 8 , 891–901.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82 , 878–902.

Fiske, S. T., Lin, M., & Neuberg, S. L. (1999). The continuum model. Dual-process theories in social psychology, 321–254.

Fiske, S. T., & Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A continum of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: Influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 23 , 1–74.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56 (2), 109–118.

Good, J. J., Moss-Racusin, C. A., & Sanchez, D. T. (2012). When do we confront? Perceptions of costs and benefits predict confronting discrimination on behalf of the self and others. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36 , 210–226.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Greenberg, D., Ladge, J., & Clair, J. (2009). Negotiating pregnancy at work: public and private conflicts. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 2 , 42–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-4716.2008.00027.x

Hebl, M. R., King, E. B., Glick, P., Singletary, S. L., & Kazama, S. (2007). Hostile and benevolent reactions toward pregnant women: Complementary interpersonal punishments and rewards that maintain traditional roles. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92 , 1499–1511. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1499

Hebl, M. R., & Skorinko, J. (2005). Acknowledging one’s physical disability in the interview: Does “when” make a difference? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35 , 2477–2492.

Heilman, M. E., & Okimoto, T. G. (2007). Why are women penalized for success at male tasks? The implied communality deficit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92 , 81–92.

Heilman, M. E., & Okimoto, T. G. (2008). Motherhood: A potential source of bias in employment decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93 , 189–198.

Hoobler, J. M., Wayne, S. J., & Lemmon, G. (2009). Bosses’ perceptions of family–work conflict and women’s promotability: Glass ceiling effects. Academy of Management Journal, 5 , 939–957.

Jones, E. E., Farina, A., Hastorf, A. H., Markus, H., Miller, D. T., Scott, R. A., & French, R. S. (1984). Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships . New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Jones, K. P., Botsford Morgan, W., Walker, S. S., & King, E. B. (2013). Bias in promoting employed mothers. In M. Paludi (Ed.), The Psychology for Business Success . Westport, CT: Praeger.

Jones, K. P., & King, E. B. (2013). Managing concealable stigmas at work a review and multilevel model. Journal of Management, . doi: 10.1177/0149206313515518

Kalev, A., Dobbin, F., & Kelly, E. (2006). Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. American Sociological Review, 71 , 589–617.

Kalinoski, Z. T., Steele-Johnson, D., Peyton, E. J., Leas, K. A., Steinke, J., & Bowling, N. A. (2013). A meta-analytic evaluation of diversity training outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34 , 1076–1104.

Kanter, R. M. (1977). Some effects of proportions on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to token women. American Journal of Sociology, 82 , 965–990.

King, E. B. (2008). The effect of bias on the advancement of working mothers: Disentangling legitimate concerns from inaccurate stereotypes as predictors of advancement in academe. Human Relations, 61 , 1677–1711. doi: 10.1177/0018726708098082

King, E. B., & Botsford, W. E. (2009). Managing pregnancy disclosures: Understanding and overcoming the challenges of expectant motherhood at work. Human Resource Management Review, 19 , 314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.03.003

King, E. B., Hebl, M. R., George, J. M., & Matusik, S. F. (2010). Understanding tokenism: Antecedents and consequences of a psychological climate of gender inequity. Journal of Management, 36 , 482–510.