- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

Editor's Choice

- Information for authors

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Why publish with the journal

- About DNA Research

- About the Kazusa DNA Research Institute

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Editor-in-Chief

Satoshi Tabata

About the journal

DNA Research is an internationally peer-reviewed journal which aims at publishing papers of highest quality in broad aspects of DNA and genome-related research …

Latest Articles

High-Impact Research Collection

Explore a collection of freely available high-impact research from 2020 and 2021 published in DNA Research .

Browse the collection

DNA Research is the official journal of Kazusa DNA Research Institute, published by Oxford University Press and supported by funding from Chiba Prefecture, Japan.

Why publish in DNA Research?

Growing Impact Factor, fully open access journal, low open access charges, and more.

Volume 26, Issue 6: TASUKE+: a web-based platform for exploring GWAS results and large-scale resequencing data

Read the Executive Editor’s commentary

Resource Articles: Genomes Explored

Email alerts

Register to receive table of contents email alerts as soon as new issues of DNA Research are published online.

Recommend to your library

Fill out our simple online form to recommend DNA Research to your library.

Recommend now

Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

publicationethics.org

PubMed Central

This journal enables compliance with the NIH Public Access Policy Read more

- Open access

Open access options for authors.

Accepting high quality papers on broad aspects of DNA and genome-related research.

Related Titles

- Author Guidelines

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1756-1663

- Copyright © 2024 Kazusa DNA Research Institute

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Recombinant DNA technology and DNA sequencing

Affiliation.

- 1 Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, United Kingdon.

- PMID: 31652313

- DOI: 10.1042/EBC20180039

DNA present in all our cells acts as a template by which cells are built. The human genome project, reading the code of the DNA within our cells, completed in 2003, is undoubtedly one of the great achievements of modern bioscience. Our ability to achieve this and to further understand and manipulate DNA has been tightly linked to our understanding of the bacterial and viral world. Outside of the science, the ability to understand and manipulate this code has far-reaching implications for society. In this article, we explore some of the basic techniques that enable us to read, copy and manipulate DNA sequences alongside a brief consideration of some of the implications for society.

Keywords: CRISPR; DNA sequencing; biochemical techniques and resources.

© 2019 The Author(s).

Publication types

- Cloning, Molecular / methods

- DNA / genetics*

- DNA / isolation & purification

- DNA, Recombinant / genetics*

- Electrophoresis, Agar Gel / methods

- Genetic Testing*

- Genetic Vectors / genetics

- Plants, Genetically Modified / genetics*

- Polymerase Chain Reaction / methods

- DNA, Recombinant

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Mini review article, past, present, and future of dna typing for analyzing human and non-human forensic samples.

- 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL, United States

- 2 International Forensic Research Institute, Florida International University, Miami, FL, United States

Forensic DNA analysis has vastly evolved since the first forensic samples were evaluated by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). Methodologies advanced from gel electrophoresis techniques to capillary electrophoresis and now to next generation sequencing (NGS). Capillary electrophoresis was and still is the standard method used in forensic analysis. However, dependent upon the information needed, there are several different techniques that can be used to type a DNA fragment. Short tandem repeat (STR) fragment analysis, Sanger sequencing, SNapShot, and capillary electrophoresis-single strand conformation polymorphism (CE-SSCP) are a few of the techniques that have been used for the genetic analysis of DNA samples. NGS is the newest and most revolutionary technology and has the potential to be the next standard for genetic analysis. This review briefly encompasses many of the techniques and applications that have been utilized for the analysis of human and nonhuman DNA samples.

Introduction

Forensic genetics applies genetic tools and scientific methodology to solve criminal and civil litigations ( Editorial, 2007 ). Locard’s Exchange Principle states that every contact leaves a trace, making any evidence a key component in forensic analysis. Biological evidence can comprise of cellular material or cell-free DNA from crime scenes, and as technologies improved, genetic methodologies were expanded to include human and non-human forensic analyses. Although these methodologies can be used for any genome, the prevalence of databases and standard guidelines has allowed human DNA typing to become the gold standard. This review will discuss the historical progression of DNA analysis techniques, strengths and limitations, and their possible forensic applications applied to human and non-human genetics.

Methodologies to Detect Genetic Differences in Humans Is the “Gold Standard”

“dna fingerprinting”: the beginning of human forensic dna typing.

“DNA fingerprinting” was serendipitously discovered in 1984 ( Jeffreys, 2013 ). What they found propelled DNA “fingerprinting,” or DNA typing, to the forefront in legal cases to become the “gold standard” for forensic genetics in a court of law. Jeffreys first used restriction enzymes to fragment DNA, a method in which restriction endonucleases (RE) enzymes fragment the genomic DNA, producing restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP) patterns. Since each RE recognizes specific DNA sequences to enzymatically cut the DNA, then inherent differences between gene sequences, due to evolutionary changes, will produce different fragment lengths. If the enzyme site is present in one individual but has changed in a different individual, the fragment lengths, once separated and visualized, will differ. While this technique was useful for some studies, Jeffreys did not find it useful for his particular genetic studies. Subsequently when working with the myoglobin gene in seals, he discovered that a short section of that gene – a minisatellite – was conserved and when isolated and cloned could be used to detect inherited genetic lineages as well as individualize a subject. Fragment length separation by electrophoresis, followed by transfer to Southern blot membranes, hybridized with a specific or non-specific complementary isotopic DNA probe, allowed for DNA fragments visualization ( Jeffreys et al., 1985b ). Upon careful analysis, Jeffreys determined that the fragments represented different combinations of DNA repetitive elements, unique to each individual, and could be used to better identify individuals or kinship lineages ( Jeffreys et al., 1985b ). Jeffreys’ technology was used in several subsequent paternity, immigration, and forensic genetics cases ( Gill et al., 1985 ; Jeffreys et al., 1985a ; Evans, 2007 ). This was just the beginning of a whole new era in DNA typing.

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) Analysis: The Past

After Jeffreys’ discoveries, many DNA analyses methods involving electrophoretic fragment separation were discovered. Many were based on RFLP principles ( Botstein et al., 1980 ), e.g., amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) ( Vos et al., 1995 ), and terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (TRFLP) ( Liu et al., 1997 ). Others like length heterogeneity- polymerase chain reaction (LH-PCR) ( Suzuki et al., 1998 ) were based on intrinsic insertions and deletions of bases within specific genetic markers. Sanger sequencing ( Sanger and Coulson, 1975 ), and single-strand conformational polymorphism (SSCP) analysis ( Orita et al., 1989 ), while separated by electrophoresis, are theoretically based on single base sequence changes rather than insertions, deletions or RE site differences. While Jeffrey’s DNA fingerprinting method provided a very high power of discrimination, the main limitations were it was very time-consuming and required at least 10–25 ng of DNA to be successful ( Wyman and White, 1980 ). With these limitations, RFLP was not always feasible for forensic cases.

Short Tandem Repeat (STR) Analysis: The Present

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was discovered by Kary Mullis in 1985 and helped transform all DNA analyses ( Mullis et al., 1986 ). The current standard for human DNA typing is short tandem repeat (STR) analysis ( McCord et al., 2019 ). This method amplifies highly polymorphic, repetitive DNA regions by PCR and separates them by amplicon length using capillary electrophoresis. These inheritable markers are a series of 2–7 bases tandemly repeated at a specific locus, often in non-coding genetic regions. Forensic STRs are commonly tetranucleotide repeats ( Goodwin et al., 2011 ), chosen because of their technical robustness and high variation among individuals ( Kim et al., 2015 ). The combined DNA index system (CODIS) uses 20 core STR loci, expanded in 2017, and several commercial kits are available that contain these STRs ( Oostdik et al., 2014 ; Ludeman et al., 2018 ). After amplification, different fluorochromes on each primer set allow for visualization of STRs after deconvolution, creating a STR profile consisting of a combination of genotypes ( Gill et al., 2015 ). This method has become the gold standard for human forensics. Its greatest strength is the standardization of loci used by all laboratories and an extremely large searchable database of genetic profiles. However, some limitations and challenges are faced when dealing with highly degraded or low template DNA samples. To overcome these technical challenges, standardized mini-STR kits have been developed which use shorter versions of the core STRs and can be used in the same manner for forensic cases ( Butler et al., 2007 ; Constantinescu et al., 2012 ). Keep in mind, DNA typing of humans – a single species – is the gold standard because of (a) the concerted scientific effort to standardize loci to analyze, (b) the development of commercial kits that can produce the same results regardless of instrumentation or laboratory performing the work, (c) a compatible and very large database that provides allelic frequencies for all sub-populations of humans, (d) standardized statistical methods used to report the results and (e) many court cases that have accepted human DNA typing evidence in a court of law – setting the precedent for future cases to use DNA typing results.

Methodologies to Detect Genetic Differences in Non-Humans: Past and Present

Amplified fragment length polymorphism (aflp) analysis.

It was not long before scientists realized that non-human DNA could provide informative genetic evidence in forensic cases. Applications include bioterrorism, wildlife crimes, human identification through skin microorganisms, and so much more ( Arenas et al., 2017 ). Since large quantities of biological materials are frequently not found at crime scenes, successful RFLP analyses were unlikely. Combining restriction enzymes and PCR technology, a process known as AFLP analysis ( Vos et al., 1995 ), became a method for DNA fingerprinting using minute amounts of unknown sourced DNA. REs digest genomic DNA, then ligation of a constructed adapter sequence to the ends of all fragments allows the annealing of primers designed to recognize the adaptor sequences. Subsequent amplification generates many amplicons ranging in length when separated and visualized in an electropherogram or on a gel ( Vos et al., 1995 ; Butler, 2012 ). AFLP markers for plant forensic DNA typing have been used because it provides high discrimination, requires only small amounts of DNA and the method is reproducible, all forensically important characteristics ( Datwyler and Weiblen, 2006 ). For example, since most cannabis is clonally propagated, subsequent generations will have identical genetic profiles as seen with AFLP ( Miller Coyle et al., 2003 ), providing useful intelligence links back to the source population. But there are significant variation between cultivars and within populations, so not having a standard database representing the species’ diversity for statistical comparisons greatly limits the method’s applicability. Another forensic example of its use is differentiating between marijuana and hemp, two morphologically and genetically similar plants, one an illicit drug while the other is not. In this study, three populations of hemp and one population of marijuana were analyzed with AFLP producing 18 bands that were specific to hemp samples. Additionally, 51.9% of molecular variance occurred within populations indicating these polymorphisms were useful for forensic individualization ( Datwyler and Weiblen, 2006 ).

Terminal Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (TRFLP) Analysis

As a result of the anthrax letter attacks of 2001, microbial forensics came to the forefront ( Schmedes et al., 2016 ), a discipline that combines multiple scientific specialties – microbiology, genetics, forensic science, and analytical chemistry. One method used to compare microbial communities is TRFLP ( Liu et al., 1997 ; Osborn et al., 2000 ; Butler, 2012 ). With this method, the DNA is amplified using “universal,” highly conserved primer sequences shared across all organisms of interest, i.e., the 16S rRNA genes in bacteria and Archaea, and then uses REs to fragment the PCR products ( Table 1 ). Separated by capillary electrophoresis, only the fluorescently tagged terminal restricted fragments are visualized ( Mrkonjic Fuka et al., 2007 ), reducing the profile complexity and providing high discrimination. TRFLP has been used to characterize complex microbial communities for forensic applications by linking the similarity of the amplicon patterns generated from the intrinsic soil communities to the evidence from a crime scene ( Meyers and Foran, 2008 ; Habtom et al., 2017 ). This method does provide a distinct pattern reflective of the microbial community, useful for forensic genetics but the method does not provide any sequence information. Another limitation is no standardization of which primer pairs or REs are used, making direct comparisons between studies difficult. This lack of standardization also hinders the development of a database for species identification. Additionally, the method is time-consuming due to the additional step of restriction digestion and the possibility of incomplete enzymatic digestion can complicate the interpretation of results ( Osborn et al., 2000 ; Moreno et al., 2006 ).

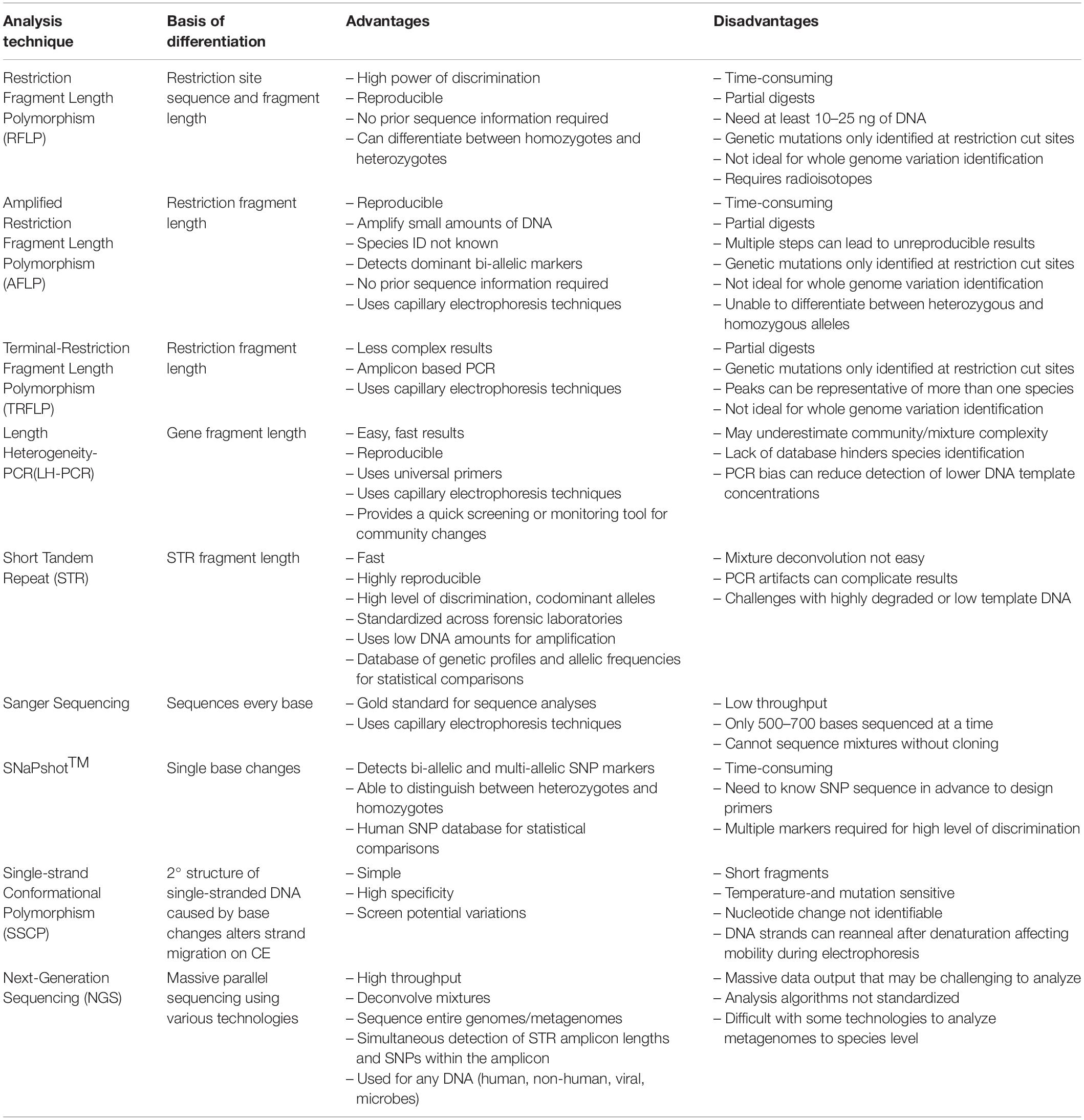

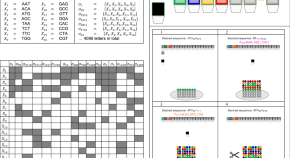

Table 1. The basis of differentiation, advantages, and disadvantages of past and current technologies.

Length Heterogeneity-Polymerase Chain Reaction (LH-PCR)

Another methodology has been used to characterize microbial communities is length heterogeneity- polymerase chain reaction (LH-PCR) ( Suzuki et al., 1998 ). Universal primers complementary to highly conserved domains within genomes are used to amplify hypervariable sequences within specific sequence domains. The 16S/18S rRNA genes, the chloroplast genes or Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) regions are commonly used. This technique is based on the natural sequence length variation due to insertions and deletions of bases that occur within a domain ( Moreno et al., 2006 ). It has been used to characterize microbial communities for forensic soil applications where a correlation between geographic location and microbial profiles has proven to be more discriminating than elemental soil analysis ( Moreno et al., 2006 , 2011 ; Damaso et al., 2018 ). With LH-PCR, metagenomic DNA extracted from the soil is amplified using fluorescently labeled universal primers with amplicon peaks within the electropherogram representing the minimum diversity within the community. However, specific sequence information is not known as many peaks of the same size could represent more than one species, thereby masking the community’s actual taxonomic diversity. A recent study showed the intrinsic diversity of a microbial mat, masked by LH-PCR, could be further resolved by the inherent sequence differences using capillary electrophoresis-single strand conformational polymorphism (CE-SSCP) analysis ( Damaso et al., 2014 ) and confirmed by sequencing. The advantage of LH-PCR is it is a fast and reproducible method that can correlate geographical areas to microbial patterns with bioinformatics ( Damaso et al., 2018 ); but a soil database would need to be developed to be useful beyond specific geographical areas.

Methodologies to Detect Intersequence Variation: The Past and Present

Sanger sequencing and single nucleotide polymorphism (snp) variation.

The basis of genomic differentiation is the intrinsic order of base pairs within a region that can be evaluated by sequencing. Sanger sequencing has been the gold standard since the 1970s ( Sanger and Coulson, 1975 ). Sanger sequencing was termed the gold standard because of the ability for single base pair resolution allowing for full sequence information to be determined. Robust and extensive databases are also readily available for comparison, i.e., GenBank, to identify an organism. However, it does have some limitations such as the short length (<500–700 bp) and it cannot sequence mixtures of organisms, for example, without cloning, so it would not be useful for sequencing complex microbial communities without intense time, effort and cost.

Other approaches use the ability to identify intrinsic single base sequence variation using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within four forensically relevant SNP classes: identity-testing, ancestry informative, phenotype informative, and lineage informative. SNPs are particularly useful when typing degraded DNA or increasing the amount of genetic information retrieved from a sample ( Budowle and van Daal, 2008 ; Goodwin et al., 2011 ). SNaPshot TM is a commercially available SNP kit that can identify known SNPs using single base extension (SBE) technology ( Daniel et al., 2015 ; Fondevila et al., 2017 ). Wildlife forensics has used SNaPshot TM to identify endangered or trafficked species that are illegally poached to support criminal prosecutions. Elephant species identification from ivory and ivory products ( Kitpipit et al., 2017 ) or differentiating wolf species from dog subspecies ( Jiang et al., 2020 ) are both examples of SNaPshot TM assays developed for wildlife forensics. By using species-specific SNPs, the samples could be identified. But yet again, the limitation becomes the need for species-specific reference databases and the monumental task of developing a robust database for each species. Human SNPs databases with allele frequencies, as seen in dbSNP, however, are available making their forensic application more feasible in some cases.

Next-Generation Sequencing: The Present

Massively parallel sequencing (MPS) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) allows for mixtures of genomes of any species to be sequenced in one analysis ( Ansorge, 2009 ). This technology can sequence thousands of genomic regions simultaneously, allowing for whole-genome, metagenomic sequencing or targeted amplicon sequencing ( Gettings et al., 2016 ). Various NGS technologies are available each using slightly different technologies to sequence DNA ( Heather and Chain, 2016 ). Verogen has developed kits explicitly for human forensic genomics using Illumina’s MiSeq FGx system ( Guo et al., 2017 ; Moreno et al., 2018 ). The FBI recently approved DNA profiles generated by Verogen forensic technology to be uploaded into the National DNA Index System (NDIS) ( SWGDAM, 2019 ), making it the first NGS technology approved for NDIS.

Short tandem repeat mixture deconvolution, degraded, low template samples, and even microbial community samples are just a few of the potential NGS applications for forensic genomics and metagenomics ( Borsting and Morling, 2015 ). In human STR analyses, the greatest challenge is mixture deconvolution. NGS technology presents an increased power of discrimination of STR alleles using the intrinsic SNPs genetic microhaplotypes – a combination of 2–4 closely linked SNPs within an allele ( Kidd et al., 2014 ; Pang et al., 2020 ). However, the acceptance of analyses programs to deconvolve mixtures has not been standardized to the same level as it has for STRs.

Microbes are the first responders to changes in any environment because they are rapidly affected by the availability of nutrients and their intrinsic habitats. This makes them excellent indicators for studies investigating post-mortem interval (PMI) or as an indicator of soil geographical provenance ( Giampaoli et al., 2014 ; Finley et al., 2015 ). In decaying organisms, shifts in epinecrotic communities or the thanatomicrobiome are becoming increasingly critical components in investigating PMI ( Javan et al., 2016 ). Sequencing of the thanatomicrobiome revealed the Clostridium spp. varied during different stages human decomposition, the “Postmortem Clostridium Effect” (PCE), providing a time signature of the thanatomicrobiome, which could only have been uncovered through NGS ( Javan et al., 2017 ). However, the lack of consensus in analyses techniques must be addressed before NGS methodologies can be introduced into the justice system ( Table 1 ).

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

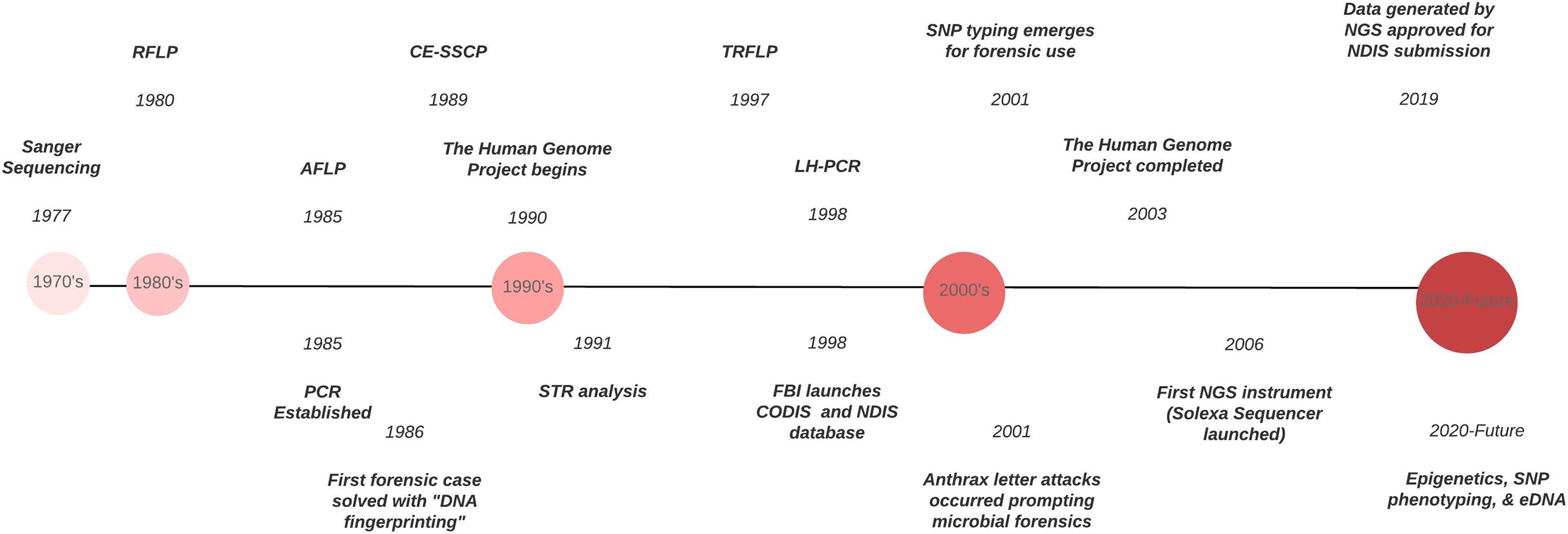

Forensic DNA typing has progressed quickly within a short timeframe ( Figure 1 ), which can be attributed to the many advancements in molecular biology technologies. As these techniques advance, forensic scientists will analyze more atypical forms of evidence to answer questions deemed unresolvable with traditional DNA analyses. For example, epigenetics and DNA methylation markers have been proposed to estimate age, determine the tissue type, and even differentiate between monozygotic twins ( Vidaki and Kayser, 2018 ). However, since epigenetic patterns are also influenced by environmental factors, they can be dynamic, and a number of confounding factors have the potential to affect predictions and must be taken into account when preparing prediction models (i.e., age estimation). Additionally, phenotype informative SNPs across the genome can infer physical characteristics like eye, hair, and skin color, even age, from an unknown source of DNA retrieved from a crime scene. But this technology could pose an “implicit bias” toward minorities, especially in “societies where racism and xenophobia are now on the rise” ( Schneider et al., 2019 ) if not ethically and judicially implemented. With the increased sensitivity of NGS, low biomass samples from environmental DNA (eDNA) – DNA from soil, water, air – can complement and enhance intelligence gathering or provenance in criminal cases. Pollen and dust are two types of eDNA recently explored for their future forensic potential ( Alotaibi et al., 2020 ; Young and Linacre, 2021 ). However, if used in criminal investigations where the eDNA collected has had interaction with other environments, there must be some protocol or quality control established to account for variability that is likely to occur. This makes the prudent validation of this type of DNA analysis, essential. Limitations also arise due to lack of a database for comparison of samples and statistical analyses to evaluate the strength of a match like in the analysis of human STR profiles.

Figure 1. Timeline of the evolution of DNA typing technologies from the 1970’s to the present.

DNA has long been the gold standard in human forensic analysis because of the standardization of DNA markers, databases and statistical analyses. It has laid the foundation for these promising new technologies that will significantly enhance intelligence gathering and species identification – human and non-human – in forensic cases. In order for these methodologies to be useful in criminal investigations, they must adhere to the legal standards such as the Frye or Daubert Standards which determines if an expert testimony or evidence is admissible in court. A method can be deemed acceptable if it follows forensic guidelines set by organizations such as NIST’s Organization Scientific Area Committees (OSAC), Society for Wildlife Forensic Sciences (SWFS), Scientific Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods (SWGDAM), and the International Society for Forensic Genetics (ISFG) ( Linacre et al., 2011 ) just to name a few. These committees provide the guidelines for validation, interpretation, and quality assurance, all necessary components for DNA analysis. The US Fish and Wildlife forensic laboratory has standardized protocols for crimes against federally endangered or threatened species 1 . However, the more common limiting factors in the development of standard guidelines of non-human forensic genetic analyses across different state laboratories are the lack of consensus in methodologies, supporting allelic databases and standardized statistical analyses. Addressing those issues could lay the foundation for non-human analyses to be on par with human analyses.

Author Contributions

DJ designed and wrote the manuscript. DM edited and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the invitation by the editors to contribute to this special edition. DJ was supported by the Florida Education Fund’s McKnight Doctoral Fellowship.

- ^ https://www.fws.gov/lab/about.php

Alotaibi, S. S., Sayed, S. M., Alosaimi, M., Alharthi, R., Banjar, A., Abdulqader, N., et al. (2020). Pollen molecular biology: Applications in the forensic palynology and future prospects: A review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 1185–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.02.019

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ansorge, W. J. (2009). Next-generation DNA sequencing techniques. N. Biotechnol. 25, 195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2008.12.009

Arenas, M., Pereira, F., Oliveira, M., Pinto, N., Lopes, A. M., Gomes, V., et al. (2017). Forensic genetics and genomics: Much more than just a human affair. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006960

Borsting, C., and Morling, N. (2015). Next generation sequencing and its applications in forensic genetics. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 18, 78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2015.02.002

Botstein, D., White, R. L., Skolnick, M., and Davis, R. W. (1980). Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 32, 314–331.

Google Scholar

Budowle, B., and van Daal, A. (2008). Forensically relevant SNP classes. Biotechniques 60:610. doi: 10.2144/000112806

Butler, J. M. (2012). “Non-human DNA,” in Advanced Topics in Forensic DNA Typing , ed. J. M. Butler (San Diego: Academic Press), 473–495.

Butler, J. M., Coble, M. D., and Vallone, P. M. (2007). STRs vs. SNPs: thoughts on the future of forensic DNA testing. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 3, 200–205. doi: 10.1007/s12024-007-0018-1

Constantinescu, C. M., Barbarii, L. E., Iancu, C. B., Constantinescu, A., Iancu, D., and Girbea, G. (2012). Challenging DNA samples solved with MiniSTR analysis. Brief overview. Rom. J. Leg. Med. 20, 51–56. doi: 10.4323/rjlm.2012.51

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Damaso, N., Martin, L., Kushwaha, P., and Mills, D. (2014). F-108 polymer and capillary electrophoresis easily resolves complex environmental DNA mixtures and SNPs. Electrophoresis 35, 3208–3211. doi: 10.1002/elps.201400069

Damaso, N., Mendel, J., Mendoza, M., von Wettberg, E. J., Narasimhan, G., and Mills, D. (2018). Bioinformatics Approach to Assess the Biogeographical Patterns of Soil Communities: The Utility for Soil Provenance. J. Forensic. Sci. 63, 1033–1042. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13741

Daniel, R., Santos, C., Phillips, C., Fondevila, M., van Oorschot, R. A., Carracedo, A., et al. (2015). A SNaPshot of next generation sequencing for forensic SNP analysis. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 14, 50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2014.08.013

Datwyler, S. L., and Weiblen, G. D. (2006). Genetic variation in hemp and marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) according to amplified fragment length polymorphisms. J. Forensic Sci. 51, 371–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00061.x

Editorial. (2007). Launching Forensic Science International daughter journal in 2007: Forensic Science International: Genetics. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 1, 1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2006.10.001

Evans, C. (2007). The Casebook of Forensic Detection: How Science Solved 100 of the World’s Most Baffling Crimes. New York, NY: Berkley Books.

Finley, S. J., Benbow, M. E., and Javan, G. T. (2015). Potential applications of soil microbial ecology and next-generation sequencing in criminal investigations. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 88, 69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2015.01.001

Fondevila, M., Borsting, C., Phillips, C., de la Puente, M., Consortium, E. N., Carracedo, A., et al. (2017). Forensic SNP genotyping with SNaPshot: Technical considerations for the development and optimization of multiplexed SNP assays. Forensic Sci. Rev. 29, 57–76.

Gettings, K. B., Kiesler, K. M., Faith, S. A., Montano, E., Baker, C. H., Young, B. A., et al. (2016). Sequence variation of 22 autosomal STR loci detected by next generation sequencing. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 21, 15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2015.11.005

Giampaoli, S., Berti, A., Di Maggio, R. M., Pilli, E., Valentini, A., Valeriani, F., et al. (2014). The environmental biological signature: NGS profiling for forensic comparison of soils. Forensic Sci. Int. 240, 41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.02.028

Gill, P., Haned, H., Bleka, O., Hansson, O., Dorum, G., and Egeland, T. (2015). Genotyping and interpretation of STR-DNA: Low-template, mixtures and database matches-Twenty years of research and development. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 18, 100–117. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2015.03.014

Gill, P., Jeffreys, A. J., and Werrett, D. J. (1985). Forensic application of DNA ‘fingerprints’. Nature 318, 577–579. doi: 10.1038/318577a0

Goodwin, W., Linacre, A., and Hadi, S. (2011). “An introduction to forensic genetics.” 2nd ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 53–62.

Guo, F., Yu, J., Zhang, L., and Li, J. (2017). Massively parallel sequencing of forensic STRs and SNPs using the Illumina((R)) ForenSeq DNA Signature Prep Kit on the MiSeq FGx Forensic Genomics System. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 31, 135–148. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2017.09.003

Habtom, H., Demaneche, S., Dawson, L., Azulay, C., Matan, O., Robe, P., et al. (2017). Soil characterisation by bacterial community analysis for forensic applications: A quantitative comparison of environmental technologies. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 26, 21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2016.10.005

Heather, J. M., and Chain, B. (2016). The sequence of sequencers: The history of sequencing DNA. Genomics 107, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2015.11.003

Javan, G. T., Finley, S. J., Abidin, Z., and Mulle, J. G. (2016). The Thanatomicrobiome: A Missing Piece of the Microbial Puzzle of Death. Front. Microbiol. 7:225. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00225

Javan, G. T., Finley, S. J., Smith, T., Miller, J., and Wilkinson, J. E. (2017). Cadaver Thanatomicrobiome Signatures: The Ubiquitous Nature of Clostridium Species in Human Decomposition. Front. Microbiol. 8:2096. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02096

Jeffreys, A. J. (2013). The man behind the DNA fingerprints: an interview with Professor Sir Alec Jeffreys. Investig. Genet. 4:21. doi: 10.1186/2041-2223-4-21

Jeffreys, A. J., Brookfield, J. F., and Semeonoff, R. (1985a). Positive identification of an immigration test-case using human DNA fingerprints. Nature 317, 818–819. doi: 10.1038/317818a0

Jeffreys, A. J., Wilson, V., and Thein, S. L. (1985b). Hypervariable ‘minisatellite’ regions in human DNA. Nature 314, 67–73. doi: 10.1038/314067a0

Jiang, H. H., Li, B., Ma, Y., Bai, S. Y., Dahmer, T. D., Linacre, A., et al. (2020). Forensic validation of a panel of 12 SNPs for identification of Mongolian wolf and dog. Sci. Rep. 10:13249. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70225-5

Kidd, K. K., Pakstis, A. J., Speed, W. C., Lagace, R., Chang, J., Wootton, S., et al. (2014). Current sequencing technology makes microhaplotypes a powerful new type of genetic marker for forensics. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 12, 215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2014.06.014

Kim, Y. T., Heo, H. Y., Oh, S. H., Lee, S. H., Kim, D. H., and Seo, T. S. (2015). Microchip-based forensic short tandem repeat genotyping. Electrophoresis 36, 1728–1737. doi: 10.1002/elps.201400477

Kitpipit, T., Thongjued, K., Penchart, K., Ouithavon, K., and Chotigeat, W. (2017). Mini-SNaPshot multiplex assays authenticate elephant ivory and simultaneously identify the species origin. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 27, 106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2016.12.007

Linacre, A., Gusmão, L., Hecht, W., Hellmann, A. P., Mayr, W. R., Parson, W., et al. (2011). ISFG: Recommendations regarding the use of non-human (animal) DNA in forensic genetic investigations. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 5, 501–505. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2010.10.017

Liu, W. T., Marsh, T. L., Cheng, H., and Forney, L. J. (1997). Characterization of microbial diversity by determining terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 4516–4522. doi: 10.1128/AEM.63.11.4516-4522.1997

Ludeman, M. J., Zhong, C., Mulero, J. J., Lagace, R. E., Hennessy, L. K., Short, M. L., et al. (2018). Developmental validation of GlobalFiler PCR amplification kit: a 6-dye multiplex assay designed for amplification of casework samples. Int. J. Legal. Med. 132, 1555–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00414-018-1817-5

McCord, B. R., Gauthier, Q., Cho, S., Roig, M. N., Gibson-Daw, G. C., Young, B., et al. (2019). Forensic DNA Analysis. Anal. Chem. 91, 673–688. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05318

Meyers, M. S., and Foran, D. R. (2008). Spatial and temporal influences on bacterial profiling of forensic soil samples. J. Forensic Sci. 53, 652–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00728.x

Miller Coyle, H., Palmbach, T., Juliano, N., Ladd, C., and Lee, H. C. (2003). An overview of DNA methods for the identification and individualization of marijuana. Croat Med. J. 44, 315–321.

Moreno, L. I., Galusha, M. B., and Just, R. (2018). A closer look at Verogen’s Forenseq DNA Signature Prep kit autosomal and Y-STR data for streamlined analysis of routine reference samples. Electrophoresis 39, 2685–2693. doi: 10.1002/elps.201800087

Moreno, L. I., Mills, D. K., Entry, J., Sautter, R. T., and Mathee, K. (2006). Microbial metagenome profiling using amplicon length heterogeneity-polymerase chain reaction proves more effective than elemental analysis in discriminating soil specimens. J. Forensic Sci. 51, 1315–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00264.x

Moreno, L. I., Mills, D., Fetscher, J., John-Williams, K., Meadows-Jantz, L., and McCord, B. (2011). The application of amplicon length heterogeneity PCR (LH-PCR) for monitoring the dynamics of soil microbial communities associated with cadaver decomposition. J. Microbiol. Methods 84, 388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.11.023

Mrkonjic Fuka, M., Gesche Braker, S. H., and Philippot, L. (2007). “Molecular Tools to Assess the Diversity and Density of Denitrifying Bacteria in Their Habitats,” in Biology of the Nitrogen Cycle , eds H. Bothe, S. J. Ferguson, and W. E. Newton (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 313–330.

Mullis, K., Faloona, F., Scharf, S., Saiki, R., Horn, G., and Erlich, H. (1986). Specific enzymatic amplification of DNA in vitro: the polymerase chain reaction. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1, 263–273. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1986.051.01.032

Oostdik, K., Lenz, K., Nye, J., Schelling, K., Yet, D., Bruski, S., et al. (2014). Developmental validation of the PowerPlex((R)) Fusion System for analysis of casework and reference samples: A 24-locus multiplex for new database standards. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 12, 69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2014.04.013

Orita, M., Iwahana, H., Kanazawa, H., Hayashi, K., and Sekiya, T. (1989). Detection of polymorphisms of human DNA by gel electrophoresis as single-strand conformation polymorphisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 86, 2766–2770.

Osborn, A. M., Moore, E. R., and Timmis, K. N. (2000). An evaluation of terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis for the study of microbial community structure and dynamics. Environ. Microbiol. 2, 39–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00081.x

Pang, J. B., Rao, M., Chen, Q. F., Ji, A. Q., Zhang, C., Kang, K. L., et al. (2020). A 124-plex Microhaplotype Panel Based on Next-generation Sequencing Developed for Forensic Applications. Sci. Rep. 10:1945. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58980-x

Sanger, F., and Coulson, A. R. (1975). A rapid method for determining sequences in DNA by primed synthesis with DNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 94, 441–448. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90213-2

Schmedes, S. E., Sajantila, A., and Budowle, B. (2016). Expansion of Microbial Forensics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54, 1964–1974. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00046-16

Schneider, P. M., Prainsack, B., and Kayser, M. (2019). The Use of Forensic DNA Phenotyping in Predicting Appearance and Biogeographic Ancestry. Dtsch Arztebl. Int. 52, 873–880. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0873

Suzuki, M., Rappe, M. S., and Giovannoni, S. J. (1998). Kinetic bias in estimates of coastal picoplankton community structure obtained by measurements of small-subunit rRNA gene PCR amplicon length heterogeneity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 4522–4529.

SWGDAM (2019). Addendum to SWGDAM Autosomal Interpretation Guidelines for NGS.Swgdam. Available online at: https://www.swgdam.org/publications

Vidaki, A., and Kayser, M. (2018). Recent progress, methods and perspectives in forensic epigenetics. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 37, 180–195. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2018.08.008

Vos, P., Hogers, R., Bleeker, M., Reijans, M., van de Lee, T., Hornes, M., et al. (1995). AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407

Wyman, A. R., and White, R. (1980). A highly polymorphic locus in human DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 77, 6754–6758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6754

Young, J. M., and Linacre, A. (2021). Massively parallel sequencing is unlocking the potential of environmental trace evidence. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 50:102393. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2020.102393

Keywords : forensic genetics, DNA typing, metabarcoding, soil, microbes, minisatellites, next-generation sequencing

Citation: Jordan D and Mills D (2021) Past, Present, and Future of DNA Typing for Analyzing Human and Non-Human Forensic Samples. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9:646130. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.646130

Received: 25 December 2020; Accepted: 02 March 2021; Published: 22 March 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Jordan and Mills. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: DeEtta Mills, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Life and Death: New Perspectives and Applications in Forensic Science

recombinant dna technology Recently Published Documents

Total documents.

- Latest Documents

- Most Cited Documents

- Contributed Authors

- Related Sources

- Related Keywords

Pharmacological profile, clinical efficacy, and safety of Follitropin Delta produced by recombinant DNA technology in a human cell line (REKOVELLE® PEN for S.C. Injection 12 μg, 36 μg, 72 μg)

Genetic engineering technique in virus-like particle vaccine construction.

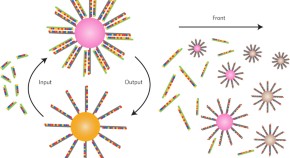

Vaccine becomes a very effective strategy to deal with various infectious diseases even to the point of eradication as in the smalpox virus. At present many conventional vaccines such as inactivated and live-attenuated vaccines. However, these vaccine methods have side effects on the population. Viral-like particle (VLP) is an alternative vaccine based on recombinant DNA technology that is safe with the same immunogenicity as conventional viruses. This vaccine has been shown to induce humoral immune responses mediated by antibodies and cellular immune responses mediated by cytotoxic T cells. With these advantages, currently various types of vaccines have only been developed on a VLP basis. VLP can be produced from a variety of recombinant gene expression systems including bacterial cell expression systems, yeast cells, insect cells, mammalian cells, plant cells, and cell-free systems.

Structural and Functional Characterization of a Novel Recombinant Antimicrobial Peptide from Hermetia illucens

Antibiotics are commonly used to treat pathogenic bacteria, but their prolonged use contributes to the development and spread of drug-resistant microorganisms raising the challenge to find new alternative drugs. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are small/medium molecules ranging 10–100 residues synthesized by all living organisms and playing important roles in the defense systems. These features, together with the inability of microorganisms to develop resistance against the majority of AMPs, suggest that these molecules might represent effective alternatives to classical antibiotics. Because of their high biodiversity, with over one million described species, and their ability to live in hostile environments, insects represent the largest source of these molecules. However, production of insect AMPs in native forms is challenging. In this work we investigate a defensin-like antimicrobial peptide identified in the Hermetia illucens insect through a combination of transcriptomics and bioinformatics approaches. The C-15867 AMP was produced by recombinant DNA technology as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion peptide and purified by affinity chromatography. The free peptide was then obtained by thrombin proteolysis and structurally characterized by mass spectrometry and circular dichroism analyses. The antibacterial activity of the C-15867 peptide was evaluated in vivo by determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). Finally, crystal violet assays and SEM analyses suggested disruption of the cell membrane architecture and pore formation with leaking of cytosolic material.

Nursing Skill and Responsibility in Administration of Injection Actilyse

Actilyse can break blood clots that form in the heart, blood arteries, or lungs during a heart attack. This medication is also given to stroke patients to improve recovery and reduce the likelihood of impairment. Recombinant DNA technology was used to create Activase, a tissue plasminogen activator. It is a sterile, purified glycoprotein of 527 amino acids. It is made by combining complementary DNA (cDNA) from a human melanoma cell line with the natural human tissue-type plasminogen activator. After reconstitution with Sterile Water for Injection, USP, Activase is a sterile, white to off-white lyophilized powder for intravenous injection.

Towards the development of a chemical lure to improve the management of invading rat populations

<p>Introduced species, such as Rattus norvegicus and Rattus rattus,have contributed to the extinction of many native animals and plants in New Zealand(NZ). Current strategies exist to monitor, manage and eradicate pest species. However, these haven’t always been completely successful and tools to detect small or invading densities remain to be developed. One possible new method to address this problem is the application of chemical attractants (lures). Recently, a major urinary protein (MUP) has been shown in male miceto act as a sexual attractant. MUPs modulate the release of volatile attractants and have potential to act as attractants themselves. Our aim was to determine if a similar MUP(s) and associated volatiles are present in the urine of rats, with the prospect of creating a chemical lure to use in rat detection and eradication. Using Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, potential volatiles in rat urine have been identified. Analysis of rat urine by gel electrophoresis has shown MUPs present in both sexes. A 22.4 kDa MUP in Rattus norvegicushas been synthesised and expressed in E.coliusing recombinant DNA technology. Preliminary steps have been made towards the production of a MUP based on ship rat DNA sequence. Future behavioral trials are needed to investigate whether the synthesised protein, in the presence or absence of the urinary-derived volatiles, is a sexual attractant.</p>

If Not Now, When? Nonserotype Pneumococcal Protein Vaccines

Abstract The sudden emergence and global spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have greatly accelerated the adoption of novel vaccine strategies, which otherwise would have likely languished for years. In this light, vaccines for certain other pathogens could certainly benefit from reconsideration. One such pathogen is Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), an encapsulated bacterium that can express >100 antigenically distinct serotypes. Current pneumococcal vaccines are based exclusively on capsular polysaccharide—either purified alone or conjugated to protein. Since the introduction of conjugate vaccines, the valence of pneumococcal vaccines has steadily increased, as has the associated complexity and cost of production. There are many pneumococcal proteins invariantly expressed across all serotypes, which have been shown to induce robust immune responses in animal models. These proteins could be readily produced using recombinant DNA technology or by mRNA technology currently used in SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. A door may be opening to new opportunities in affordable and broadly protective vaccines.

A comprehensive comparison between camelid nanobodies and single chain variable fragments

AbstractBy the emergence of recombinant DNA technology, many antibody fragments have been developed devoid of undesired properties of natural immunoglobulins. Among them, camelid heavy-chain variable domains (VHHs) and single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) are the most favored ones. While scFv is used widely in various applications, camelid antibodies (VHHs) can serve as an alternative because of their superior chemical and physical properties such as higher solubility, stability, smaller size, and lower production cost. Here, these two counterparts are compared in structure and properties to identify which one is more suitable for each of their various therapeutic, diagnosis, and research applications.

RISPR-Cas9: a weapon against COVID-19

In current pandemic circumstances, novel coronavirus is a salutary challenge for all over the world and coronavirus used the host cell for replication. Coronavirus usually use the host cellular products to perform their basic functions. Various specific target sites also present in coronavirus proteins for target-specific therapy such as small inhibitor molecule for viral polymerase or prevent the attachment of viruses to the receptor sites for vaccination purpose. The virus attaches to ACE2 receptors and uses enzyme to cleave translated products which encodes for various enzymes like RNA polymerase, helicase etc. The system needs some processes which lead for the disturbance and make the virus unable to replicate. The recombinant DNA technology makes a great advancement in every field of life with a number of importance in agriculture, industries, and clinics. It is used to manipulate the genetic material of living organism for the purpose of producing desirable products such as disease resistant crops, treatment of cancer, genetic disease and viral disease. Thus, for the purpose of antiviral strategies, the specific technique called CRISPR/Cas9 is used, and this technique has the capability to target specific nucleotide sequence inside the genome of coronavirus.

Recombinant DNA Technology

Export citation format, share document.

More From Forbes

Gene therapy, dna's past, rna's future: a new wave of hope.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Artist representation of gene therapy

This story is part of a series on the current progression in Regenerative Medicine. In 1999, I defined regenerative medicine as the collection of interventions that restore tissues and organs damaged by disease, injured by trauma, or worn by time to normal function. I include a full spectrum of chemical, gene, and protein-based medicines, cell-based therapies, and biomechanical interventions that achieve that goal.

In this subseries, we focus specifically on gene therapies. We explore the current treatments and examine the advances poised to transform healthcare. Each article in this collection delves into a different aspect of gene therapy's role within the larger narrative of Regenerative Medicine.

Gene therapy represents the frontier of hope in combating genetic disorders, promising to rewrite the rulebook on how we address some of the most persistent and challenging diseases known to humankind. Over the last ten years, we have witnessed a transformation from speculative science to a reality where genetic disorders are treated not just in theory but in patients' lives.

A New Wave of Gene Therapy Trials and Approvals

Gene therapy made significant strides throughout the 2010s, culminating in multiple regulatory trial approvals for gene therapy products across 38 countries . The work done in these trials led to formal regulatory approval for the use of gene therapies in a variety of countries, some of the most significant of these were from 2012 to 2017.

Apple Confirms Major iPhone Changes With New App Features Enabled

Aew dynamite results winners and grades as cm punk destroys jack perry, chiefs rashee rice hit with 8 criminal charges in connection to multi car crash.

Number of gene therapy clinical trials approved worldwide 1989-2017

In 2012, Glybera became the first-ever gene therapy approved in the European Union . This therapy treats lipoprotein lipase deficiency by compensating for the missing or ineffective enzyme. Similarly, Strimvelis, approved in 2016 , has been used to treat ADA-SCID. This rare genetic disorder severely compromises the immune system in children. This therapy corrects the gene responsible for the disease.

In 2017, three FDA approvals were game-changers for the medical field. The first was Kymriah , a new way of treating acute lymphoblastic leukemia by genetically modifying the patient's T-cells to attack cancer cells. The second approval was for Luxturna , which treats a genetic form of blindness by directly providing a standard copy of the RPE65 gene to the eye. Lastly, the FDA approved Yescarta , the first CAR T-cell therapy, in 2017 to treat large B-cell lymphoma.

Zolgensma, approved in 2019 , is a gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), which causes muscle wasting. This therapy introduces a new, functional copy of the human SMN gene into a patient's motor neuron cells, providing a one-time treatment for this lifelong disease. Gene therapies like Zolgensma offer hope for people who have genetic disorders that have been difficult or impossible to treat until recently.

While these approvals were happening, CRISPR-Cas9 became synonymous with a new era in gene editing.

The CRISPR Revolution

During the mid-2010s, the genetic research and therapy field experienced a seismic shift with the introduction of the CRISPR-Cas9 system . This tool has dramatically changed gene editing, allowing for precise and efficient modification of genes in living organisms. Unlike traditional gene-editing methods, the CRISPR system enables accurate targeting of specific genes with unprecedented speed and precision .

Diagram of CRISPR for patients with cancer-tested T cells modified to better "see" and kill cancer. ... [+] In this example, CRISPR removed three genes: two that can interfere with the NY-ESO-1 receptor and another that limits the cells’ cancer-killing abilities.

Technology development has significantly reduced the barriers to entry for genetic research and therapy, making it more accessible and affordable. With the capability to customize treatments with unprecedented specificity, new therapies can be tested and developed with greater accuracy and efficiency. This has paved the way for more effective genetic research and treatment, potentially leading to cures for previously thought untreatable diseases.

Every Challenge is an Open Door

While gene therapy has seen notable successes and approvals, there have also been setbacks in recent years. In science, every challenge is an open door, and gene therapy has walked through many of these, with more to open. The biggest challenges in the field have been the complexities in delivering treatments, persistent safety concerns, and daunting immune responses.

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are one of the most commonly used gene therapy vectors . However, high doses of AAVs can cause potential side effects, such as inflammation and liver damage . While these side effects are usually manageable, they can lead to more severe complications.

The immune system may recognize AAVs as foreign particles and launch a full attack against them, resulting in a reduced therapeutic effect or a system-wide immune response. In some cases, this immune response is so severe it has even resulted in death, such was the case in the untimely passing of Terry Horgan, a 27-year-old man with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, following an investigational CRISPR-based treatment.

A Death in a Gene Therapy Trial

Terry Horgan's story is both brave and tragic. In October 2022, he was the only participant in an early-stage safety trial . He was given a high dosage of gene-editing therapy tailored to his unique condition. This trial used an adeno-associated virus as the vector to introduce the CRISPR tool into his body.

In Horgan's case, the viral vector precipitated an unexpected and severe immune response , leading to organ failure and, ultimately, his death. This incident has thrust the use of these vectors into the limelight, prompting intense scrutiny from the medical community and invigorating the discourse on gene therapy safety.

Drawing parallels with the 1999 case of Jesse Gelsinger , the first person publicly identified to have died in a clinical trial for gene therapy, Horgan's experience emerges both familiar and foreboding. Similarities can be seen in the unexpected immune reactions elicited by gene therapy vectors, underlying the need for revamped vigilance in early trials. Yet, the divergence lies in the progress made over the two decades separating these tragedies, a period marked by leaps in genetic understanding and technological advances.

Charting a Course for Transformation

Gene therapy has transitioned from the margins to the epicenter of medical science. The innovations of the early 21st century are now yielding concrete treatments for diseases once considered incurable. Conditions such as inherited blindness, spinal muscular atrophy, and various forms of blood cancer now benefit from FDA-approved gene therapies.

Now is an opportune moment for the medical community and others to delve into the vast potential of gene therapy. After all, we are not just the products of our genes but the architects of our genetic health.

To learn more about regenerative medicine, read more stories at www.williamhaseltine.com

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Please enable JavaScript or use a Browser that supports JavaScript

- Advanced Search

- Browse by Analyte

- Browse by Pre-analytical Factor

- Search SOPs

- SOP Compendiums

- Suggest a New Paper

- Submit an SOP

- Curator Home

- Back Office

Analysis of quality metrics in comprehensive cancer genomic profiling using a dual DNA-RNA panel.

Author(s): Watanabe K, Kohsaka S, Tatsuno K, Shinozaki-Ushiku A, Isago H, Kage H, Ushiku T, Aburatani H, Mano H, Oda K

Publication: Pract Lab Med , 2024, Vol. 39 , Page e00368

PubMed ID: 38404525 PubMed Review Paper? No

Purpose of Paper

This paper compared two DNA integrity markers (Q-value and ddCq) and one RNA integrity metric (DV200) using DNA and RNA extracted from 585 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks that had been stored for <1, 1-2, 2-3, 3-5 y or approximately 5 years before extraction. The authors investigated the predictive performance of these metrics for four next-generation sequencing quality metrics. Potential effects associated with the hospital of collection/processing and cancer type on the DNA/RNA quality metrics evaluated were also examined.

Conclusion of Paper

The duration of FFPE block storage had a deleterious effect on DNA and RNA integrity, with a higher ratio of short to long real-time PCR products (ddCq), a lower ratio of PCR-amplified DNA to double-stranded DNA (Q-value), and a lower percentage of RNA fragments >200 bp (DV200) noted with progressive storage. While ddCq was weakly to modestly negatively correlated with the percentage on-target reads, and mean and target exon coverage, Q-value was weakly to modestly positively correlated with the percentage of on-target reads and coverage uniformity and DV200 were weakly positively correlated with coverage of housekeeping genes. A ddCq ≤5.36 was highly predictive of a mean depth >500 but less predictive of coverage uniformity or target exon coverage. A Q-value ≥0.928 was predictive of a mean depth >500, coverage uniformity ≥99%, and target exon coverage ≥99%. The predictive power of a DV200 >41 for coverage of housekeeping genes that was ≥70% was 92.1%. ddCq and Q-values displayed significant differences among hospitals even after correcting for tumor type, but DV200 was not affected by hospital. Q-values were lowest and DV200 highest in lung tumors.

Study Purpose

This study compared two DNA integrity markers (Q-value and ddCq) and one RNA integrity metric (DV200) using DNA and RNA extracted from 585 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks that had been stored for <1, 1-2, 2-3, 3-5 y or approximately 5 years before extraction. The authors investigated the predictive performance of these metrics for four next-generation sequencing quality metrics. Potential effects associated with the hospital of collection/processing and cancer type on the DNA/RNA quality metrics were also examined. A total of 585 tissues that included 114 lung, 90 bowel, 58 ovarian/fallopian tube, 51 uterus, 38 soft tissue, 31 cervix, and 203 specimens of types representing <5% of the total were collected (further details were not provided) and fixed in 10-20% neutral buffered formalin for 24-72 h before paraffin embedding. The specimens were contributed from multiple hospitals, with six hospitals providing >10 specimens. DNA (582 specimens) and RNA (572 specimens) were extracted using the GeneRead DNA FFPE Kit and the RNeasy FFPE Kit, respectively. Double stranded DNA was quantified by Qubit and amplifiable DNA was quantified using the TaqMan Copy Number Reference Assay Human RNase P. The Q value was then calculated as the percentage of dsDNA that was amplifiable. NA quantity was defined as the amount of double-stranded DNA when the Q-value was >1 and as the amount of amplifiable DNA when the Q-Value was ≥1. The ddCq value was calculated based on the ratio of two real-time PCR amplicons in the FFPE DNA QC Assay version 2 Kit. The percentage of RNA fragments >200 bp (DV200) was assessed using a 2200 TapeStation. DNA and the RNA libraries were prepared using a SureSelectXT Custom Kit and the SureSelect RNA Capture Kit, respectively, and sequenced on a Next-seq Instrument.

Summary of Findings:

The duration of FFPE block storage had a deleterious effect on DNA integrity, with significantly higher ddCq values and lower Q-values noted with progressive storage. ddCq values were higher in specimens stored for >1 year compared to those stored for approximately 1 year (P<0.001, all), stored >3 years compared to 1-2 years (P<0.001, both), or stored approximately 5 years compared to those stored 2-3 or 3-5 years (P<0.001, both). Q-values were lower in specimens that were stored for 5 years than 3-5 years (P<0.01), 2-3 years (P<0.001), 1-2 years (P<0.001), or approximately 1 year (P<0.001), or stored for 3-5 years compared to those stored 1-2 years (P<0.01) or approximately 1 year (P<0.01) but were not significantly different in specimens stored <3 years when compared to those stored for approximately 1 year. ddCq was negatively correlated with the percentage on-target reads (r=-0.47, P<0.001), mean depth (r=-0664, P<0.001), and target exon coverage (r=-0.362, P<0.001); Q-value was correlated with the percentage on-target reads (r=0.353, P<0.001) and coverage uniformity (r=0.411, P<0.001). In a generalized linear model, the percentage of on-target reads was associated with ddCq, but mean depth was associated with ddCq and Q-value. The predictive power of a ddCq ≤5.36 for a mean depth >500 was 91.6%, but the same cut-off was less predictive of coverage uniformity ≥99% (55.1%) or target exon coverage ≥99% (60.6%). The predictive power of a Q-value ≥0.928 for a mean depth >500, coverage uniformity ≥99%, and target exon coverage ≥99% was 79.9%, 81.5%, and 83.1% respectively. For specimens with a low ddCq (≤5.36) but unacceptable Q-values, the on-target read percentage and mean depth were still generally acceptable but uniformity and target exon coverage were <99%. ddCq and Q-values displayed significant differences among hospitals even after correcting for tumor type. Q-values were lowest in lung tumors.

Similarly, DNA and RNA integrity were adversely affected by block storage. The percentage of RNA fragments >200 nt (DV200) decreased progressively with FFPE block storage duration, with significantly lower DV200 values from specimens that were stored >2 years than those stored approximately 1 year (P<0.001 all) or those stored for 3-5 years or approximately 5 years compared to those stored approximately 1 year (P<0.01, both). DV200 was weakly positively correlated with the coverage of housekeeping genes (r=0.369, P<0.001). The predictive power of a DV200 >41 for a coverage of housekeeping genes ≥70% was 92.1%. DV200 was not significantly different among hospitals but was significantly higher in lung cancer specimens than in bowel or ovarian/fallopian cancer specimens.

Please enable JavaScript or use a Browser that supports JavaScript for more on this study.

Biospecimens

- Tissue - Colorectal

- Tissue - Lung

- Tissue - Other

- Tissue - Uterus

- Tissue - Cervix

- Tissue - Ovary

Preservative Types

- Neoplastic - Carcinoma

- Not specified

- Neoplastic - Not specified

Pre-analytical Factors:

You recently viewed , news and announcements.

- Most Popular SOPs in March 2024

- New SOPs Available

- Most Downloaded SOPs in January and February of 2024

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- National Institutes of Health

- National Cancer Institute

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Don't Miss a Post! Subscribe

- Guest Posts

- Educational AI

- Edtech Tools

- Edtech Apps

- Teacher Resources

- Special Education

- Edtech for Kids

- Buying Guides for Teachers

Educators Technology

Innovative EdTech for teachers, educators, parents, and students

10 Great AI Tools for Researchers

By Med Kharbach, PhD | Last Update: April 8, 2024

Today, I want to talk about some really cool AI tools that are changing the way we do research. This is just a small preview of what I’m putting together in an eBook full of AI tools for researchers like us. If you don’t want to miss out on the full thing, be sure to sign up for our email updates.

There’s a lot of talk about AI in universities, and not everyone agrees about using it. But, like it or not, AI is becoming a big part of research, and it’s here to stay. I believe we should use AI the right way. It’s not about just copying and pasting stuff; that’s not real research. You still have to do the hard work of reading and writing yourself. But, AI can be a huge help, kind of like having an extra assistant who’s always there when you need it. I’m all for using AI to make our research better, as long as we keep doing the important parts ourselves.

AI Tools for Researchers

Here are are some good AI Tools I recommend for student researchers and academics:

Litmaps is a tool for research students that makes finding papers and authors on a topic easy and quick. Instead of spending lots of time reading through hundreds of papers, you can use Litmaps to find the important ones in seconds. It helps you find papers you might miss otherwise and keeps you updated on new research without getting overwhelmed. You can see which papers are connected and important for your work through visual maps, making it simple to keep track of your literature review.

Jenni is an AI-powered writing tool that helps you write, edit, and reference your work easily. It’s like having a helpful friend who’s always there to get you past writer’s block, suggest ways to say things differently, and make sure your citations are in order. More specifically, Jenni can:

- Suggest words and sentences as you write to help you keep going.

- Help you cite sources correctly in styles like APA, MLA, and others, using your own PDFs or research.

- Let you change the wording of any text to match the tone you need.

- Turn your research papers into written content by analyzing and summarizing them.

- Chat with your PDFs to quickly understand and summarize them.

- Import a bunch of sources at once if you have them saved.

- Export your work to LaTeX, Word, or HTML without messing up your formatting.

- Create an outline for your paper just from a prompt you provide.

- Work in multiple languages, including English (US and British), Spanish, German, French, and Chinese.

- Keep all your research organized in one place for easy citing in any document.

- Offer suggestions and help expand notes into full paragraphs, so you’re never stuck staring at a blank page.

3. Paperpa l

Paperpal is a handy tool for anyone who writes academic texts like essays, theses, dissertations, or research papers. It checks your writing for grammar mistakes and makes sure you’re using the right language for academic work. With the help of generative AI, Paperpal can also create outlines, abstracts, and titles for your papers. This tool makes it easy to paraphrase your work for clarity .You can also check your work for plagiarism with detailed reports, get help generating various parts of your academic text, and even translate text from over 25 languages to English.

Related: 6 Best Text to Video AI Tools

4. Unriddle

Unriddle is a cool tool that changes how students and researchers work with documents. It gives you an AI helper for any document you’re looking at, making it super quick to find info, sum up tricky topics, and take notes easily. Unriddle is all about making your research easier and faster, so you don’t have to read every single word to find what you need.

Unriddle also helps you write and reference sources the right way. It can point out the most important sources when you highlight text, so your references are spot-on. It works in over 90 languages and has some cool extra features like a Chrome extension to summarize online articles, settings you can change to fit your needs, and the ability to work with many documents at once.

5. Connected Papers

Connected Papers helps you discover recent important works without needing to maintain extensive lists. It is a visual tool for research students and academics who are diving into a new field or ensuring their research is comprehensive. It starts with a paper you’re interested in and creates a graph showing similar papers in that field. This visual approach helps you understand the trends and main contributors quickly. It’s especially useful in fast-moving fields where new studies are constantly published.

With Connected Papers, you can also build a bibliography for your thesis more efficiently. By starting with a few key references, it finds additional relevant papers, helping you to fill in the gaps. It offers views for finding significant prior works or the latest reviews and state-of-the-art papers following your chosen study.

6. Scite Assistant

Scite Assistant is like a research companion powered by large language models (LLMs), designed to make your research process smoother and more insightful. You can ask scite Assistant any research-related question and you will get insights and explanations for its responses, helping you understand the reasoning behind its conclusions.

scite Assistant offers customizable settings to tailor the tool to your specific research needs. You can control whether you want references included, filter your searches by year, topics, or journals, and even specify the sources the Assistant should use, like your own dashboard collection or preferred journals. This level of customization ensures that the responses and sources are relevant to your specific research questions and preferences, making it an invaluable tool for academics and researchers seeking detailed and reliable information.

7. DocAnalyzer

DocAnalyzer.ai makes talking to your documents easy and smart. You can upload one or many documents and start chatting right away, getting answers to your questions in real time. This tool is great because it understands the context of your documents, making it super helpful for finding exactly what you need without any confusion. What makes docAnalyzer.ai special is how simple and smart it is to use. You can ask your PDFs questions and get back clear, detailed answers quickly. You can even share your document chats with others, making teamwork easier.

8. SciSummary

SciSummary is all about making it easier to get the gist of scientific articles fast. You can email or upload a document, and in minutes, you’ll get a summary sent right back to you. This is perfect for scientists, students, and anyone who’s busy but needs to stay on top of the latest research without reading long articles.

SciSummary uses advanced AI, like a super smart robot that can summarize any scientific article. The AI gets better over time, learning from summaries that experts check. This means you can quickly understand new discoveries and research without spending hours reading. SciSummary offers a free option for summarizing articles, and if you need more, there are affordable plans with more features.

9. Explainpaper

Explainpaper is like having a smart friend that helps you understand research papers quickly. You just upload a paper, highlight the parts you find confusing, and get an explanation. This tool is perfect for diving into complex topics and for speeding up your review process. With Explainpaper, you’re not alone when facing intimidating jargon or complex concepts.

10. SciSpace

SciSpace aims to make finding and understanding research papers a breeze. It’s an all-in-one platform where you can read papers, get straightforward explanations from AI, and explore related research. SciSpace is designed to cut down on the time researchers spend looking for information and dealing with the hassle of formatting papers. With access to metadata for over 200 million papers and more than 50 million full-text PDFs, SciSpace provides tools like a citation generator, AI detector, and paraphraser to make your research process smoother and more productive. It’s a dedicated workspace for researchers, publishers, and institutions to collaborate and discover information effortlessly.

Final thoughts

As I mentioned, these tools are just a part of the bigger picture I’m assembling in the upcoming eBook. The AI tools we explored today are stepping stones towards a more efficient, insightful, and innovative research process. But remember, they’re tools to aid us, not to replace the foundational skills of rigorous research. Embracing AI in our work, when used ethically and wisely, opens up new horizons for discovery and understanding. Stay tuned for the full eBook release, and let’s navigate this promising future of research together.

Join our mailing list

Never miss an EdTech beat! Subscribe now for exclusive insights and resources .

Meet Med Kharbach, PhD

Dr. Med Kharbach is an influential voice in the global educational technology landscape, with an extensive background in educational studies and a decade-long experience as a K-12 teacher. Holding a Ph.D. from Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax, Canada, he brings a unique perspective to the educational world by integrating his profound academic knowledge with his hands-on teaching experience. Dr. Kharbach's academic pursuits encompass curriculum studies, discourse analysis, language learning/teaching, language and identity, emerging literacies, educational technology, and research methodologies. His work has been presented at numerous national and international conferences and published in various esteemed academic journals.

Join our email list for exclusive EdTech content.

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

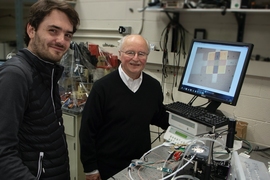

A new way to detect radiation involving cheap ceramics

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

The radiation detectors used today for applications like inspecting cargo ships for smuggled nuclear materials are expensive and cannot operate in harsh environments, among other disadvantages. Now, in work funded largely by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security with early support from the U.S. Department of Energy, MIT engineers have demonstrated a fundamentally new way to detect radiation that could allow much cheaper detectors and a plethora of new applications.

They are working with Radiation Monitoring Devices , a company in Watertown, Massachusetts, to transfer the research as quickly as possible into detector products.

In a 2022 paper in Nature Materials , many of the same engineers reported for the first time how ultraviolet light can significantly improve the performance of fuel cells and other devices based on the movement of charged atoms, rather than those atoms’ constituent electrons.

In the current work, published recently in Advanced Materials , the team shows that the same concept can be extended to a new application: the detection of gamma rays emitted by the radioactive decay of nuclear materials.

“Our approach involves materials and mechanisms very different than those in presently used detectors, with potentially enormous benefits in terms of reduced cost, ability to operate under harsh conditions, and simplified processing,” says Harry L. Tuller, the R.P. Simmons Professor of Ceramics and Electronic Materials in MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering (DMSE).

Tuller leads the work with key collaborators Jennifer L. M. Rupp, a former associate professor of materials science and engineering at MIT who is now a professor of electrochemical materials at Technical University Munich in Germany, and Ju Li, the Battelle Energy Alliance Professor in Nuclear Engineering and a professor of materials science and engineering. All are also affiliated with MIT’s Materials Research Laboratory

“After learning the Nature Materials work, I realized the same underlying principle should work for gamma-ray detection — in fact, may work even better than [UV] light because gamma rays are more penetrating — and proposed some experiments to Harry and Jennifer,” says Li.