A series of writings throughout my cosmic journey…

Persepolis: An Analysis of the Role of Identity During the Iranian Revolution

Although cinema is often seen as entertainment rather than a work of art, Marjane Satrapi’s film Persepolis beautifully captures the rhetoric of the Iranian revolution in an artistic demeanour. Her comic-inspired film follows the life of Marjan, a young girl struggling for truth during an era where the lines between human sincerity and strict government policy are blurred. The aim of the movie, however, can be argued to be the unification of the Western and Eastern public ideology regarding Iran – based on the fundamental issues of assimilation. Members of the Iranian diaspora can deeply resonate with Persepolis as a whole, but more specifically relate with Marjan’s personal endeavour for meaning in a binary world of culture. In addition to this, the movie drew a deep parallel with Marjan’s struggle with truth, and the journey for the entire nation of Iran in a society of deeply rooted political conflict. Although a wide variety of the film’s themes and ideas are solely rooted from Marjan’s personal identity, it should also be noted that a wide variety of the sub themes follow the socio-political conditions in Iran, such as women’s issues, social constructs and Western intervention. Therefore, this essay aims to explore Marjan’s emphasis on self identity, in addition to the storytelling of Iranian history and conflict. I will use Saparti’s choice of animation as aid for my thesis with an emphasis on imagery juxtaposition.

Firstly, I will trace the origins of the root of the title and meaning behind Saparti’s choice to call the film Persepolis. Beginning with the analysis of the film title, the world Persepolis quite literally means the ancient land of the Persians. The Persian Empire was found by Cyrus the Great and was renown at the time for its strong reign.[1] Once Alexander the Great took over the capital, the people were left impoverished and their country in ruins.[2] I argue that Satrapi chose the title Persepolis as a parallel to the events that occurred during the era. The merciless overthrow of the government combined with the excruciating torture that many Iranians felt at the time are both parallels with the film. Before the war in both circumstances, it can be argued that Iran was prosperous and free-spirited. Saparti aimed to show how dictatorship can dangerously harm a society that was once so well reputable. Throughout Persepolis it was evident that the political strain can affect nearly all interpersonal levels of Iranians throughout the revolution. This is evident in the way the Iranian revolution shaped the path of Marjane’s life; from her personal relationships to her drive for life. Furthermore, the powerful state before the war was a symbol for the utopia that the Iranians thought they were going to have. For many Iranians, the revolution was meant to be an event that altered their state for the better; to free them from the chains of totalitarian regime. However, this was clearly not the case.

I will lay out the framework to further prove that using animation in Persepolis was a tool for Saparti in order to create an artistic portrayal. The use of animation meant an acceptance of the impossibility of perfect representation of such traumatic events. In other words, it became an accessible means of dealing with difficult content of Saparti’s life. The issues that Saparti aims to explore are often ‘grey’ and not black-and-white. This allows surplus room for the viewer to self-interpret the complex emotion that Saparti aims to express. Although it can be counter argued that animation lacks a particular element of realism, it immerses the viewer in narrative and aesthetic art. In this way, the use of animation offers a medium where memory, dream, and fantasy can be intertwined; without the burden of realist depiction. In a way, the lack of clarity and realism leaves furthermore to the imagination, which allows the viewer to grapple with meaning to the point of resolution.

Saparti monochromatic palette beautifully uses the juxtaposition of light and dark in her film. The contrast aims to represent the innate emotions and experience of each character within the film, whilst outlining their inner motivations. The gloomy silhouettes represented the lives of sorrow that the Iranian people felt, while the bright lights aimed to signify the sense of hope they felt as they clung onto the memory of freedom. A beautiful example is when Marjane learns that her Uncle Anoosh was re-arrested by the regime troops, and she is seen in front of a texture-less background with no sense of depth. The outline of her black hair and clothing contrast within frame as her figure is seen hovering through a vacant, black void. This image, although animated, depicts the sense of deep isolation and resentment Marjane faced towards the revolution. Furthermore, the use of dense black frames is used during the scene of the bombing occurring in Iran. The dark silhouette of the stairs combined with the black empty screen during the bombing ignite a sense of fear and mystery within the viewer. This is used many times throughout the film, most notably when depicting the false dream that the Iranian government sold to young men embarking off to the war. Saparti was able to, once again, draw a parallel between the young men of Iran fighting in the Iraqi war (often promised the “key to paradise”), causing the viewer to ask if these young men are any different than the youth of the American wars. In this way, Saparti uses universalization to appeal to both Iranian and Western viewers.

As the film commences, it is evident from the very opening scene that Marjane is dissatisfied with her contrasting cultures. This scene was one of the very few in colour; further punctuating the film. Marjane is seen in solitude waiting at the Paris airport in a familiar flashback. She shines a look of disapproval upon putting on a head scarf before her arrival in Tehran whilst smoking a cigarette. Immediately, we see that the complex and deeply rooted themes of identity, exile and return emerge in the introduction. Throughout the movie, the recurring theme of solitude and identity emerge as thousands of Iranians left Iran during the revolution. The relocation to another country left colossal gaps in the streams of identity amongst those individuals. Furthermore, Persepolis captures the sense of loss when Marjane’s family members dwell on the question of whether they too should leave or stay behind. In this way, the film depicts the struggles of those individuals that choose to stay, whilst placing emphasis on the severed ties with those that choose to stay behind. An example is Marjan’s Uncle Anoosh, where the theme of exile is embodied in his character’s decisions. His exile to Russia and attempt to sneak into his homeland signified his deeply rooted ties to his Iranian identity. Although he was a revolutionary that fought against the ordeals of the Shah, Uncle Anoosh served as a role model for Marjane; embodying hope, strength, and passion. He shares his stories of imprisonment with Marjan, which serve as a medium for inspiration. In addition, the toy swans carved out of the prison bread serve as a symbol for hope. Upon Anoosh’s execution, the white swans are surrounded by black water – once again the use of dark and light to represent Marjan’s deep feelings of loss and hopelessness. In this way, the perceptive genius used by Saparti illustrates the anguish Marjane faces as she is also ‘exiled’ to Vienna during her youth.

Upon moving to Vienna, we see a stark contrast with the quaint depiction of Tehran. Although in Western eyes, Iran is often seen as the foregin ‘other’; in this turn around of events, Vienna was depicted in the light of “otherness”, with Viennese tams and sidewalk cafes, along with ringing church bells. In this way, the viewer was placed directly in Marjane’s perspective; engulfed in a sense of wonder and foreignism. An overarching scene in which consumerism and Western industrialism is well depicted in one where Marjane is in the bounds of a modern-day grocery store – shining with branded product. This generates a stark contrast with the poverty that many Iranians faced during the revolution, and due to this a fundamental and underlying guilt is developed in Marjane. While her family is faced with the darkness of war, Marjane is blessed with the Western opportunities and frivolous life. Unable to live with the guilt and lack of external support from her friends in Vienna, Marjane is later diagnosed with depression. There is uneasiness with her friends’ ease of philosophy and the dark realities of war that Marjane faced. This internal struggle aims to show how the revolution creates deeply embedded memories in the Iranian diaspora, in which it is carried with them throughout all their experiences. The internal struggle within Marjan also runs parallel with the struggles of Iranian across the globe, which further attributes to the universality of the film. In addition to her struggle into assimilation, Marjan also experiences various romantic relationships that also contribute to her shaping of her adolescent identity.

As the attempts to find understanding and sympathy in her friendships, the same is apparent in her strive for love. As she strives to find meaning in these relationships, Marjane loses a piece of herself. In a scene where she lies about being French from fear of being seen as a “barbaric” Iranian, Marjane imagines her grandmother following her trail and catching her in her lie. Through the act of dishonesty, it is clear that Marjane still possesses an innate dissatisfaction with her identity. Upon her return to Tehran, she also sees the socio-political effects that the revolution had on the people. As her grandmother famously quoted that “fear lulls us to sleep,” Marjane sees fear manifesting in the actions of her fellow Iranians. In a way, the revolution had normalized people to be savage and this is evident in the distinct scenes of her mother at the grocery store or swearing at other drivers. Furthermore, her decision to turn in an innocent man also shows how fear had caused everyone in Iran to resort to a “survival” and “state of nature” instinct. The Iranians became stripped of their pride, nationalism and meaning, therefore the country had evolved into a cold society, where all individuals only possessed the will to survive.

It is evident that Saparti effectively used animation as a means of portraying the harsh realities of the Iranian revolution. Saparti was able to beautifully capture the binary world of Iranian and Western culture, and the deeply rooted conflict that many individuals like Marjan felt during this era. It is also evident, however, that the Iranian diaspora today also feel disconnect when approaching the fragile world of cultural clash. Furthermore, Saparti was able to go beyond the physical bounds of Iran and travel beyond into the universal world, where her film can be applied to individuals of nearly all cultures. That is the beauty of universality that lies in the fundamental roots of Persepolis. No matter what culture one may originate from, the internal conflict with the “traditional” and modern will always persist. The outcome, however, will not always be positive. Although Marjane was able to undergo multiple external identity alterations, in the end, she was still the carefree and curious soul. Her drive for justice is evident at a young age and is manifested later in her life. This is evident when she is seen standing up for her classmates in university regarding dress code. Marjane’s early life and her exposure to her parents’ activism instilled determination for justice and a desire for freedom.

Through the use of animation and contrasting depictions of dark and light, Saparti is able to tell the story of Marjane’s coming of age during the violent birth of the Iranian revolution. Through this, Saparti also universalizes the ideology of binary culture and sheds light on the day-to-day victims of the Iranian revolution that are often ignored in Western portrayal. Persepolis acts as a beacon of hope where cross-cultured individuals can reconnect with meaning, and a desire to discover identity through Saparti’s rich, inky black and white illustrations. Marjan’s dissatisfaction with revolutionary promise for freedom, and with totalitarian rule is manifested in her acts of defiance throughout the film. In conclusion, Saparti’s story-telling monochrome palette reveal throughout Persepolis that the deep socio-political issues it highlights are anything but black and white.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Spam prevention powered by Akismet

English and Comparative Literary Studies

Persepolis: a close reading, reading repression.

Marjane Satrapi’s episodic graphic novel tells the story of herself as a young girl growing up in post-revolutionary Iran. However, rather than a simple coming-of-age story Satrapi inserts the difficulties of

the political, religious, and economic strife that shaped her childhood and adolescence” (Tensuan, 956).

as major factors affecting her development. The comics explore the effects and responses to the ideological implementations of the Islamic theocracy, both through their narrative and their form. Satrapi’s graphics mirror the repression dealt with in her narrative. Persepolis has been highly acclaimed by critics, an interesting review by Andrew D. Arnold in Time Magazine described Satrapi’s work

It has the strange quality of a note in a bottle written by a shipwrecked islander. That Satrapi chose to tell her remarkable story as a gorgeous comic-book makes Persepolis totally unique and indispensable” (Arnold, Time Magazine).

Arnold's strange analogy is fitting to Persepolis as Satrapi conveys a world many Westerners have only experienced from a Western perseptive. She senstively and truthfully illustrates her development into a woman amongst the trauma of revolution, war and repression - redefining the importance of the graphic novel as historically and autobiographically informing.

The relationship between narrative and graphics.

Satrapi’s black and white illustrations, for example, mirror the very repression that Marji and her friends and family face. For example, the veil is an extensively repeated image throughout Persepolis; and with it the illustrations seem to change. Whenever the children are depicted wearing the veil Satrapi’s graphics become plainer and unassuming – mirroring the uniformity of the girls.

Escaping repression.

Yet, as much as these characters and their freedom of expression are repressed, Satrapi’s graphics show exactly how the Iranians escaped and rebelled against such repression.As Theresa Tensuan states:

Satrapi’s comics highlight the ways in which figures resist, subvert and capitulate to forces of social coercion and normative visions” (Tensuan, 954).

And so, having shown how the Iranians are forced to surrender to the Islamist theocracy, it is worthwhile exploring how they rebel against it. For example, the juxtaposition of the two images below perfectly exemplifies the expected and actual responses to the introduction of the veil.

sartorial censorship” (Tarlo, 9)

imposed by her government. However, as she grows up and returns to Iran from Austria rebellion through fashion had become more subtle and harder to detect. For example, women would style their hair differently under the veil so their veils would have different appearances and shapes:

The Movement of repression.

This is clearly a child’s image of fiery death, but it is also one that haunts the text because of its incommensurability – and yet its expressionistic consonance – with what we are provoked to imagine is the visual reality of this brutal murder. (Chute, 100)

She cowardly accuses a stranger of a graver crime than her own rather than face the consequences of her rebellion. Hence, now Marjane becomes the unjust agent of repression – resembling those that she protests against.

Yet, in the end, Marjane and Reza became fed up that they could not publically show their relationship –unmarried couples could not display their affections, as pre-marital affairs were illegal. Consequently, in an attempt to escape the repression of their relationship, Marjane and Reza marry. Yet, Marjane’s regret seems almost instant; she abruptly recognises her mistake. She feels caged by their dwindling communication and eventually feels trapped by that which was meant to free them. She is depicted as litterally caged:

Ultimately Satrapi’s journey, at all stages, is affected by repression. She and fellow Iranians suffer political oppression – repressing their personal freedoms; she experiences self-inflicted persecution as an outcast in Vienna; she momentarily becomes a similar agent of repression to those she hates and finally enters a marriage where she feels isolated and imprisoned. Therefore, Satrapi not only effectively and historically illustrates the trauma of war and political oppression but shows the personal (and sometimes unexpected) consequences of trying to escape repression. Her illustrations, often artistically reflecting her narrative, are charming and engaging – her novel is a testament for the power of the graphic novel in representing political and personal turmoil.

Marianne Matusz

Works cited:.

Arnold, Andrew D. “An Iranian Girlhood” Time Magazine. 16/05/2003. Web. 19 May 2013.

Chute, Hillary. "The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis" WSQ: Women's Studies Quarterly 36.1 (2008): 92-110. Web. 16 May 2013.

Tarlo, Emma. "Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis: A Sartorial Review." Fashion Theory 11.2-3 (2007): 347-356. Web. 18 May 2013.

Tensuan, Theresa M. "Comic visions and revisions in the work of Lynda Barry and Marjane Satrapi." MFS Modern Fiction Studies 52.4 (2006): 947-964.

Works Consulted:

Davis, Rocío G. "A Graphic Self: Comics as Autobiography in Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis." Prose Studies 27.3 (2005): 264-279.

Ellis, Samantha. “Less of Your Lipgloss” The Observer. 7/11/2004. Web. 19 May 2013

Whitlock, Gillian. "Autographics: The Seeing" I" of the Comics." MFS Modern Fiction Studies 52.4 (2006): 965-979. Web. 16 May 2013.

Naghibi, Nima, and Andrew O'Malley. "Estranging the Familiar: East and West in Satrapi's Persepolis." ESC: English Studies in Canada 1.2 (2005): 223-247.

Identity in the “Persepolis” Novel by Marjane Satrapi Essay

A distinctive feature of modern society – its differences in national, social, demographic, class, gender, religious, material, and other characteristics – has given rise to social inequality and oppression. Marjane Satrapi’s novel Persepolis provides an autobiographical account of experiencing systemic political oppression, telling a story of futile resistance and realization of perpetuity of oppression. It is popular to believe in the superiority of peaceful and lawful political resistance to other approaches; however, Satrapi’s story proves that diplomacy does not always secure successful peacemaking. In fact, her story reveals that oppression cannot always be eradicated neither by violence nor peaceful protesting, and the best course for action for the persecuted is fleeing while possible. Nevertheless, one thing that is invaluable regardless the successfulness of resistance is education. Throughout the novel, Satrapi illustrates the importance of education in resisting political oppression through the experiences of herself and the people around her.

One of the key themes of Marjane Satrapi’s novel Persepolis is the importance of education in resisting oppression. Satrapi’s own story is a testament to the transformative power of education. Despite living under a repressive regime in Iran, Satrapi was able to pursue her education and gain a deep understanding of her country’s history, politics, and culture. This knowledge allowed her to better understand the roots of the oppression she experienced and to develop strategies for resisting it.

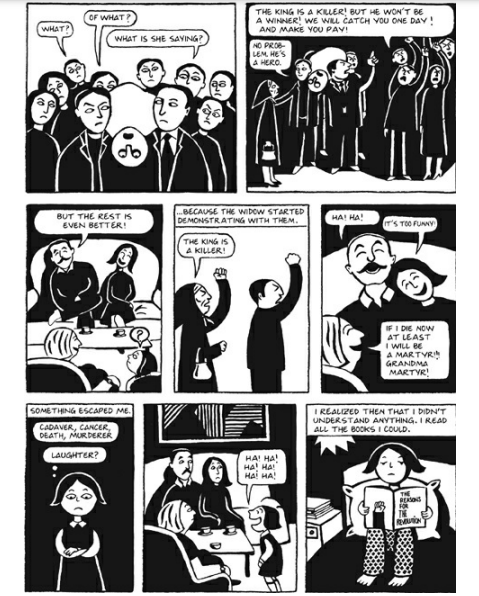

Throughout the novel, she engages in critical thinking and intellectual pursuits, reading books, attending university, and engaging in debates and discussions with her peers. She recalls a scene from her childhood when she tried to engage in a politics conversation with her parents but fell short of understanding. As she writes in her visual novel, “I realized then that I didn’t understand anything; I read all the books I could” (Satrapi 36).

This education not only helps her to better understand the complex issues facing her society, but also gives her the knowledge and skills to resist oppression in a more effective and informed way.

Additionally, Satrapi’s education allows her to connect with others who share her values and beliefs. Through her studies, she meets like-minded individuals who are also committed to opposing the oppressive regime in Iran. Together, they form a community of resistance and support, using their education as a tool to inspire and empower each other to fight for change.

In addition to providing individuals with the tools to understand and challenge oppression, education also has the power to build solidarity and foster social change. Through education, people can learn about the struggles and experiences of others and come together to work towards common goals. This sense of community and shared purpose can be a powerful force for change, as it allows people to work together to challenge systems of oppression and create a more just society.

Finally, education also helps Satrapi to develop the resilience and resilience she needs to endure the challenges and hardships she faces. Through her studies, she learns how to cope with difficult circumstances and find meaning and purpose in her struggles. This resilience ultimately helps her to not only survive, but also to thrive despite the oppressive conditions in which she lives.

Education is the most effective tool people have to resist oppression. This may seem counterintuitive, as education is often seen as a passive pursuit that lacks the immediacy of more direct forms of resistance such as protests or acts of civil disobedience. However, education has the unique ability to empower individuals with the knowledge and skills they need to understand and challenge systems of oppression, as well as to advocate for their own rights and the rights of others. While education is not a panacea for oppression, it is a crucial tool that can help individuals to better understand and resist systems of oppression. Whether through formal schooling or self-education, gaining knowledge and understanding is an essential step towards creating a more equitable and just world.

Satrapi, Marjane. Persepolis . Pantheon Books, 2004.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 9). Identity in the "Persepolis" Novel by Marjane Satrapi. https://ivypanda.com/essays/identity-in-the-persepolis-novel-by-marjane-satrapi/

"Identity in the "Persepolis" Novel by Marjane Satrapi." IvyPanda , 9 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/identity-in-the-persepolis-novel-by-marjane-satrapi/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Identity in the "Persepolis" Novel by Marjane Satrapi'. 9 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Identity in the "Persepolis" Novel by Marjane Satrapi." January 9, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/identity-in-the-persepolis-novel-by-marjane-satrapi/.

1. IvyPanda . "Identity in the "Persepolis" Novel by Marjane Satrapi." January 9, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/identity-in-the-persepolis-novel-by-marjane-satrapi/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Identity in the "Persepolis" Novel by Marjane Satrapi." January 9, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/identity-in-the-persepolis-novel-by-marjane-satrapi/.

- Literature - Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood by Marjane Satrapi

- Review: “Persepolis” by Marjane Satrapi

- A Fine Work of Art: "Persepolis" by Marjane Satrapi

- Images in Satrapi's "Persepolis" Graphic Novel

- Comparison: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by S. Alexie and Persepolis by M. Satrapi

- The Importance of Stories in the Person’s Life according to Persepolis

- Satrapi's "The Complete Persepolis": Understanding Comics

- “Osama" , The Kite Runner, and Persepolis Links

- "Persepolis" Film: Events in Iran

- Art Creation and Reflection on “Persepolis” Movie

- The American Minorities Studies Course Reflection

- Personal Identity Under the Influence of Community

- The Concept of Self: Ideal, Aught and Actual Domains

- Family Counseling: Resolving Conflict and Promoting Wellness

- McPherson and Shelby on African American Identity

Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return

Marjane satrapi, everything you need for every book you read..

Marjane leaves her home country of Iran for Austria to escape the oppression that women suffer under Iran’s Islamic fundamentalist regime—yet she finds that she faces some level of sexism everywhere she goes. While the particulars of how Marjane experiences sexism differ from country to country and culture to culture, some elements remain the same. Namely, Marjane recognizes that no matter the culture, women are harassed and policed —and that this treatment prevents them from living fulfilling lives or reaching their full potential.

In theory, Marjane leaves Tehran for Vienna specifically to escape persecution because of her sex—but she soon discovers that sexism isn’t unique to Iran. Marjane arrives in Europe believing that she’ll be safe from having her femininity and her outspoken nature policed by the Guardians of the Revolution. These are the men and women who patrol cities in Iran to scold and punish people—mostly women—who violate the country’s laws about behavior, dress, and interactions with the opposite sex. But instead of the Guardians, Marjane encounters many European men who sexually harass her—such as when she gets a job at a cafe and has to put up with male patrons pinching her bottom. Others, mostly women, accuse her of prostitution or general sexual deviancy. Marjane faces a unique form of discrimination as both a woman and a racial minority in Austria. Her white, European female friends don’t experience the same type of insults or assumptions about their sexual activities—even though Marjane knows that her friends are far more promiscuous and sexually liberated than she is. Rather, what Marjane experiences in Vienna is a combination of sexism and prejudice because she’s Iranian. In the eyes of many, she’s an uncivilized, promiscuous foreigner. But while the sexism, catcalling, and shaming that Marjane experiences in Vienna are awful and dehumanizing, these experiences don’t come with the same threat of violence or imprisonment that being stopped by the Guardians of the Revolution does. Rather, sexist people in Vienna insult and alienate Marjane for the imagined offenses of being female and Iranian. While the danger of state-sanctioned violence is unique to Iran, leaving the country doesn’t guarantee fair treatment.

Upon Marjane’s return to Tehran at age 18, she recognizes that in addition to formally policing women through the Guardians of the Revolution, Iran has also created a culture of fear in which civilian women police one another—and themselves. Especially once Marjane begins studying art at the Islamic Azad University, she finds herself among other young women who have spent their entire lives in Iran. They police Marjane’s private life in a way that the Guardians of the Revolution cannot, as they’re her friends with whom she shares personal things. For instance, they express horror when Marjane admits that she takes birth control because she and her boyfriend have sex. The guardians of the Revolution would have no way of knowing this (though they do, at many points, demand entry to private homes to break up illegal mixed-gender parties). But the organization’s sexist agenda is bolstered by civilians, as women socially shame their peers who have premarital sex.

Though Marjane finds herself at odds with her classmates in this regard, she does find common ground with them when it comes to the university uniforms that they all dislike. The uniforms—which include a long veil and unfashionable pants that are tripping hazards—make it hard for the women to move around easily and create the artwork that they’re ostensibly there to make. But Marjane recognizes that these uniforms—and the wider societal pressure for women to dress a certain way—have a purpose beyond just controlling what women look like. She notes at one point that “The regime had understood that one person leaving her house while asking herself: ‘Are my trousers long enough? Is my veil in place?’ [...] No longer asks herself: ‘Where is my freedom of thought? Where is my freedom of speech?’” Essentially, policing women’s clothing is an effective way to keep them in a constant state of fear, thereby distracting them from asking questions that might threaten the regime’s authority. It also distracts them from their schoolwork, preventing them from fully immersing themselves in their passions and fulfilling their potential.

Marjane offers few remedies for the issues that women face in Iran. At the end of the memoir, she leaves Iran for Europe once again—this time, permanently. This implies that at least for an outspoken, independent woman like Marjane, it’s impossible to find safety or fulfillment in a country that systematically oppresses women and makes them fear for their lives. Persepolis 2 makes it abundantly clear to readers that in some form or another, the oppression of women exists everywhere. But through speaking out and educating others—and in particular, by writing firsthand accounts like Persepolis and Persepolis 2 —it’s possible to raise awareness about the issues women face and make subtler forms of oppression easier to identify and call out.

Gender and Oppression ThemeTracker

Gender and Oppression Quotes in Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return

In every religion, you find the same extremists.

That night, I really understood the meaning of “the sexual revolution.” It was my first big step toward assimilating into Western culture.

“Whatever! Existence is not absurd. There are people who believe in it and who give their lives for values like liberty.”

“What rubbish! Even that, it’s a distraction from boredom.”

“So my uncle died to distract himself?”

For Momo, death was the only domain where my knowledge exceeded his. On this subject, I always had the last word.

I’d already heard this threatening word yelled at me in the metro. It was an old man who said “dirty foreigner, get out!” I had heard it another time on the street. But I tried to make light of it. I thought that it was just the reaction of a nasty old man.

But this, this was different. It was neither an old man destroyed by the war, nor a young idiot. It was my boyfriend’s mother who attacked me. She was saying that I was taking advantage of Markus and his situation to obtain an Austrian passport, that I was a witch.

I had known a revolution that had made me lose part of my family.

I had survived a war that had distanced me from my country and my parents...

...And it’s a banal story of love that almost carried me away.

“What do you mean? You’ve done the deed with many people?”

“Well, I mean...I’ve had a few experiences.”

“So what’s the difference between you and a whore???”

Underneath their outward appearance of being modern women, my friends were real traditionalists.

They were overrun by hormones and frustration, which explained their aggressiveness toward me. To them, I had become a decadent Western woman.

But as soon as the effect of the pills wore off, I once again became conscious. My calamity could be summarized in one sentence: I was nothing. I was a Westerner in Iran, an Iranian in the West. I had no identity. I didn’t even know anymore why I was living.

I applied myself. Designing the “model” that would please both the administration and the interested parties wasn’t easy. I made dozens of sketches.

This was the result of my research. Though subtle, these differences meant a lot to us.

This little rebellion reconciled my grandmother and me. [...] And this is how I recovered my self-esteem and my dignity. For the first time in a long time, I was happy with myself.

The regime had understood that one person leaving herself while asking herself: Are my trousers long enough? Is my veil in place? Can my makeup be seen? Are they going to whip me?

No longer asks herself: Where is my freedom of thought? Where is my freedom of speech? My life, is it livable? What’s going on in the political prisons?

I didn’t say everything I could have: that she was frustrated because she was still a virgin at twenty-seven! That she was forbidding me what was forbidden to her! That to marry someone that you don’t know, for his money, is prostitution. That despite her locks of hair and her lipstick, she was acting like the state.

When the apartment door closed, I had a bizarre feeling. I was already sorry! I had suddenly become “a married woman.” I had conformed to society, while I had always wanted to remain in the margins. In my mind, “a married woman” wasn’t like me. It required too many compromises. I couldn’t accept it, but it was too late.

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Literature Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood

The Voice of the Oppressed in Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- American Poetry

- A Valediction Forbidding Mourning

- The Haunting of Hill House

- Crime and Punishment

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

- 0 Shopping Cart

The Complete Persepolis: Visualizing Exile in a Transnational Narrative

Leila Sadegh Beigi received her PhD in English literature from the University of Arkansas, where she is an instructor of literature. Her writing focuses on the intersection of gender, exile, and translation in contemporary Iranian women’s literature. Her recent publications include “Simin Daneshvar and Shahrnush Parsipur in Translation: The Risk of Erasure of Domestic Violence in Iranian Women’s Fiction” in the Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies (Duke University Press, 2020) and “Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Embroideries : A Graphic Novelization of Sexual Revolution across Three Generations of Iranian Women” in the International Journal of Comic Art (John Lent, 2019).

Contemporary Iranian women writers create a voice of resistance in fiction by questioning and redefining gender roles, which are defined by culture, tradition, and state law in Iran. They narrate their stories of resistance in a state of exile, a condition rooted in marginalization independent of geographical location. In this article, I will examine and analyze The Complete Persepolis , written by Iranian writer, artist, and filmmaker Marjane Satrapi, as a transnational narrative written in exile. A transnational perspective challenges the binary division between the Eurocentric “First World/Third World” framework of modern global feminist analyses. [1] Satrapi’s narrative in The Complete Persepolis focuses on a gendered and discursive manifestation of women, culture, and identity, problematizing “a purely locational politics of global-local or core-periphery in favor of viewing the lines cutting across these locations.” [2] I argue that The Complete Persepolis expands the notion of exile through the visual representations of the author’s concerns about the status of women in exile at home and abroad. The portrayal of internal exile, or exile at home, relies on images of women struggling with gender discrimination, sexism, and censorship, all of which limit and marginalize them as female citizens. In the portrayal of external exile, or exile abroad, Satrapi offers images of women experiencing racism, stereotyping, and marginalization in the West.

The graphic representation of human emotions through the perspective of a young girl experiencing gender discrimination at home and racial discrimination abroad creates a space of empathy and understanding for readers. As Scott McCloud argues, “The wall of ignorance that prevents so many human beings from seeing each other clearly [can] only be breached by communication.” [3] Satrapi breaks the “wall of ignorance” through strong visual imagery unveiling the identity of Iranian women. As a transnational hero, the protagonist, Marji, breaks cultural, ideological, and geographical barriers, and calls for global solidarity, understanding, and equality for immigrants in exile. Of course, not all immigrants are exiled subjects. What lies at the heart of exile is the lack of choice. Edward Said writes: “Exile is not, after all, a matter of choice: you are born into it, or it happens to you.” [4] Exile, banishment, and stigmatization are described by Said as distinguishing factors and specific characteristics of exile. [5]

My argument is in line with two critical debates on the neccessity of reshaping transnationl feminism. The first is Chandra Mohanty’s model of transnational feminism in her articles “‘Under Western Eyes’ Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles” (2003) and “Transnational Feminist Crossings: On Neoliberalism and Radical Critique” (2013). In “Under Western Eyes Revisited,” Mohanty suggests that “a transnational feminist practice depends on building feminist solidarities across the divisions of place, identity, class, work, belief, and so on.” [6] Mohanty calls for individual and conscious effort to use these differences to connect; “Under Western Eyes Revisited” focuses on “decolonizing feminism, a politics of difference and commonality, and specifying, historicizing, and connecting feminist struggles.” [7] A decade later, in “Transnational Feminist Crossings,” Mohanty emphasizes the importance of “re-commit[ting] to insurgent knowledges and the complex politics of antiracist, anti-imperialist feminisms.” [8] Mohanty writes: “I believe we need to return to the radical feminist politics of the contextual as both local and structural and to the collectivity that is being defined out of existence by privatization projects.” [9] She emphasizes the significance of a systematic analysis of power which depoliticizes the resistance and the social movements by the privatization of organizations and feminist antiracism in the neoliberal academic landscape. This is not about the risk of homogenization and stereotyping of differences of women in the Global South, which Mohanty discusses in an earlier article, “Under Western Eyes” (1986); this is a critique of the institutionalization of radical feminist antiracism, which aims to erase the race and class divisions which unite the voices of women locally and globally to preserve power.

The second critical debate, Nima Naghibi’s articulation of transnational feminism, discusses cross-cultural feminist misunderstandings in her book Rethinking Global Sisterhood: Western Feminism and Iran. Naghibi writes: “The problem of sisterhood remains, however, the inherent inequality between ‘sisters.’ Often using the veil as a marker of Persian women’s backwardness, Western and (unveiled) elite Iranian women represented themselves as enlightened and advanced.” [10] Like Mohanty, Naghibi calls for destabilizing and reinterrogating transnational feminism’s elimination of race and class divisions between “the civilized nations” and “rogue nations.” [11]

Satrapi’s Persepolis contributes to these debates on transnational feminism by portraying Iranian women’s struggle to manifest the powerful and thriving feminist voices of the nation. Satrapi’s discursive approach to diversity, oppression, and resistance is interwoven with culture and politics of local and global feminist discourse calling for unity and solidarity. The narrative criticizes gender discrimination in Iran, but it also questions racial discrimination in the West. Persepolis examines the visual representation of discrimination against women and gender-based violence in Iran, and it problematizes the demonized representation of Iran and Iranians in the West resulting in global marginalization of Iranian women. While the visual medium influences the writer’s ability and effort to push the boundaries of Iran’s traditional society in the narrative’s demands for a democratic space to include women, the medium also offers an antiracist reading of women from the Global South in the West.

The concept of exile is significant in understanding Persepolis as a transnational narrative because exile encapsulates the space for a transnational exchange of culture. Exiled subjects leave their homeland, and they build a diaspora community in their new country, operating as transnational identities to represent their homeland, culture, and literature. While both Iranian women and men in diaspora have contributed to the Iranian literary tradition, “women writers have been largely responsible for making Iran and the postrevolutionary immigrant experience visible in literature. Women writers of the Iranian diaspora especially appear to have comfortably left behind any concerns about adhering to the tradition of Iranian letters and have instead made writing one of the most important media for representing their particular experiences of exile, immigration, and identity.” [12] Although both diaspora and exiled writers inform transnational and intellectual identities, the exiles are particularly grounded in the notion of punishment due to their radical political views. Drawing on Said’s discussion of exile, I prefer to use the term exile in this article because exile is not always defined as the state of being away from home; rather, in the case of contemporary Iranian women writers, exile could also be defined as the state of being marginalized and alienated from the public in their own country due to their capabilities of writing about women’s limitations.

In the case of Satrapi, exile has provided a condition for her to visualize her memories, practicing her radical criticism of the political landscape locally and globally, which resonates with Said’s definition of intellectuals in exile who have obtained a “sharpened vision.” [13] For example, Satrapi problematizes Western media as representing Muslims as “terrorist[s],” and Iran’s media as “making anti-Western propaganda.” [14] This is an example of her fairness in criticizing both governments in their policies. Satrapi’s laser sharp focus on cultural and political representation in Persepolis perfectly illustrates that her narrative, as Said puts it, “provides a different set of lenses” to read her homeland. [15] Persepolis not only represents her sharp critical vision in exile, but it also provides an alternative lens through which to view Iranian women. Analyzing Persepolis as the first graphic novel in the Middle East written by an Iranian intellectual woman in exile offers a feminist version of exile challenging the conventional understanding of intellectual exile discussed by Said.

The subversive potential of female heroes in Iranian culture and literature is not censored or erased in Persepolis. Nevertheless, Satrapi’s commentary on the lack of freedom of artistic expression in Iran draws attention to one of the most important aspects of exile at home: artistic productions being subject to censorship under Islamic law. Despite her success in obtaining an art degree at the graphic school in Tehran, Satrapi suffers from a lack of freedom, this time as an artist in Iran. Censorship in art makes Satrapi ask herself, “where is my freedom of thought? Where is my freedom of speech? My life, is it livable?” [16] There are limitations for presenting women’s bodies not only in painting, but also in any other art form. To do so, an artist is required to obtain consent from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Marji resists these oppressive conditions in her brave objection to the female students’ dress code at the university. In a scene where the university has organized a lecture on the theme of “moral and religious conduct,” Marji opposes the lecturer’s views on the female dress code, saying that “you don’t hesitate to comment on us, but our brothers present here have all shapes and sizes of haircuts and clothes. Sometimes, they wear clothes so tight that we can see everything.” [17] She also questions the lack of freedom in drawing faces and bodies in the art studios (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 299. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

She finally faces her double exile by leaving Iran for France to build her identity as a successful writer and artist in a country where she does not face restrictions or censorship in producing art and publishing her stories. Inspired by Satrapi’s living in exile, her performance in The Complete Persepolis is the embodiment of a discursive manifestation of women and culture.

Crossing the borders and breaking the barriers of thoughts and ideas enables writers in exile to see with a “different set of lenses” using “exile’s situation to practice criticism.” [18] While Satrapi’s graphic novel fits Said’s definition of being able to see problems in the West as well as in her own country, it also uses a gendered lens to show women intellectuals in exile. Satrapi is critical of the Eurocentric behavior she witnesses in Vienna at several points in the novel. For example, in a scene in the religious school she attends, Marji is punished for eating in the TV room. A nun tells her, “it’s true what they say about Iranians. They have no education.” [19]

Satrapi rediscovers her new Iranian identity in the West by acknowledging Third World–women’s struggle to survive, and she depicts women’s resistance, subversion, and rebellion to confront the restrictions on their appearance and behavior in public (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 302. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Persepolis captures the nuances of Iranian society by depicting Iran as a dynamic nation and underscoring the significance of women’s resistance. While Satrapi’s approach to depicting women in Iran celebrates the vibrancy and power of Iranian women, her storytelling in Persepolis is inclusive, with its multi-perspective lens on culture, class, politics, faith, and gender in Iran.

The distance from home poses challenges for exiled writers, who risk creating “single story” narratives about their home country; [20] however, Satrapi’s inclusive narrative does not reflect a “single story” narrative about Iran. The Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Adichie discusses how culture is composed of multiple stories and the authenticity of depictions of culture depends on the representation of the multiple stories about it. [21] It is not possible to know in totality a culture without engaging with all possible stories about those people or places. Adichie observes that “the single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are not true, but that they are incomplete.” [22] Although it is not the job of one writer to represent a culture in its totality, it is the responsibility of a writer not to distort or misrepresent the culture. In this article, I discuss the multilayered representation of culture and women in Persepolis , highlighting its subversive narrative, which circulates to transnational audiences multiple representations of women’s resistance.

Satrapi responds to the political tensions between Iran and the West by creating Marji, her transnational hero. Marji narrates her observations of Iran, which has been less known to the West and Western audiences since the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Diego Maggi argues that Satrapi’s Persepolis “complicate[s] and challenge[s] binary divisions commonly related to the tensions amid the Occident and the Orient, such as East-West, Self-Other, civilized-barbarian and feminism-antifeminism.” [23] My argument in this article builds on Maggi’s argument about how Satrapi pushes the boundaries to bridge the gap between worlds. For example, Satrapi depicts the political turbulence through her childhood memories by opening the novel when she is only ten, and as a result of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, she is wearing the hijab while sitting in a sex-segregated school (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 3. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS: THE STORY OF A CHILDHOOD by Marjane Satrapi, translation copyright © 2003 by L’Association, Paris, France. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

In another scene, she reveals the ordinary life of people trying to survive under the strict Islamic regime, a difficulty which has become compounded by the country’s new restrictions on ordinary activities like dancing and throwing parties (Figure 4). She writes: “In spite of all the dangers, the parties went on. ‘Without them it wouldn’t be psychologically bearable,’ some said.” [24] Revealing a new version of reality through the portrayal of the private and public in her narrative, Satrapi tells the story of ordinary people, reminding Western readers that people are people, with common interests and ideas despite the cross-border differences in cultures.

Figure 4. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 106. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS: THE STORY OF A CHILDHOOD by Marjane Satrapi, translation copyright © 2003 by L’Association, Paris, France. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Satrapi offers an understanding of the cultural and political complexities of Iranian society, and as an intellectual in exile, she consciously uses these differences to connect to the struggle of women globally. In her book, Women, Art, and Literature in the Iranian Diaspora , Mehraneh Ebrahimi discusses the creation of visual arts as well as graphic novels by diaspora writers and artists in the humanities as an essential factor to inform a global community and to combat xenophobia. By showing women’s struggle for freedom and peace in a local and global context, Persepolis decolonizes the narrative about Iran as evil Other and Iranian women as victims. Marji’s experience traveling across borders accounts for her hybrid identity and resists projecting a stereotypical representation of Iran and Iranian women as “Other.” For example, Marji draws attention to cross-cultural behaviors and attitudes when it comes to religious extremists, who exist in all societies. As mentioned earlier, there is a scene where Marji carries her food to the TV room to enjoy while watching a show in the religious school in Vienna (Figure 5). When she is told to watch her behavior by “the mother superior,” Marji says, “but here, everyone eats while watching TV.” The mother gets angry and says, “it’s true what they say about Iranians. They have no education.” [25] After this confrontation, the nuns decide to expel Marji from school, and Marji thinks, “in every religion, you find the same extremists.” [26]

Figure 5. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 177. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Race, class, and gender differences rooted in sociocultural and political aspects are historicized in Persepolis for a Western audience. The narrative combats the West’s binary understanding of Iran and the West as black and white and instead offers an alternative image. The visual imagery in Persepolis unveils the culture and history of Iran and the identity of Iranian women for the Western audience. As an intellectual Iranian woman writer, Satrapi captures the key events from pre-revolution, post-revolution, and wartime, and their social problems to perfectly communicate with the audience through her privileged position as an elite. Although she tells the audience what life was like for a girl of her generation, class, and family background, her narrative does not suggest the life story of “all” Iranian girls during the years the book is set. For example, the stories of the girls who were terrified and traumatized by war and were forced to come to Tehran because their houses were destroyed are not included in Persepolis . These girls were misplaced in the schools in Tehran. While they had already faced the trauma of war in their hometowns, the atmosphere of the metropolitan capital intensified their repression. They faced struggles because of their accent, different skin color, and different appearance, but they still had to obey the strict rules for hijab at schools and in public.

A full and accurate representation of Iranian women requires a multilayered narrative that gives equal voice to women with different experiences and backgrounds. Many scholars discuss Satrapi’s narrative as being close to the facts in its portrayal of Iran and Iranian women . For example, Farzaneh Milani writes: “Marjane Satrapi celebrates the Iranian people’s history of resistance, subversion, and rebellion as much as she bears witness to the miseries and injustices caused by political and religious dogmatism.” [27] Women’s struggle of resistance is not lost in Persepolis ; instead, the traumatic experience of the years after the Iranian Revolution and the Iran–Iraq War is part of the focus. Indeed, Satrapi responds to Iranian women’s literary tradition as a contributor to that tradition. Persepolis depicts three generations of female characters: Marji, her mother, and her grandmother are portrayed as women conscious of their rights and their identity in fighting back against oppression. These characters bring their unique perspectives on the sociocultural issues that affect women’s everyday life in Iran. For example, Marji’s mom joins the demonstration against compulsory veiling, Marji shouts at the two guardians of the revolution who stop her in the street and warn her not to run, and the grandma removes the stigma around divorce when Marji is full of fear and hesitation after her divorce. [28]

By expressing their sexual experiences, adventures, and concerns through the portrayal of their personal lives, these characters represent strong women with activist perspectives as active agents during the years the novel is set. The narrative provides the Western audience with a glimpse into the joy and pleasure in the lives of women amidst their constant struggle for peace and equality, creating empathy and understanding that transcends borders.

Satrapi’s Persepolis attempts to reflect the voices of Iranian women as being in resistance to oppression rather than as being submissive . The high rate of readership of this graphic novel among Western readers is due to Satrapi’s success in showing a compelling and alternative image of Iranian women. Women writers exiled abroad risk telling a “single story” narrative about Iran, but they may take a similar risk in representing their homeland by catering to Western preconceptions about it. Hamid Dabashi discusses this risk in his book Brown Skin, White Masks , demonstrating “how intellectuals who migrate to the Western side of their colonized imagination are prone to employment by the imperial power to inform on their home countries in a manner that confirms conclusions already drawn.” [29] Because Satrapi’s narrative is critical of both Iran and the places she lived in the West, I don’t find it problematic that Persepolis is written for a Western audience. Indeed, the dual nature of women’s resistance to the oppression is portrayed through the author’s double critique of Iranian fundamentalism and Western imperialism. While Persepolis depicts the conflict between democracy and dictatorship in the shah’s regime, it simultaneously problematizes democracy and fundamentalism under the Islamic Republic. In fact, by criticizing the pro-American shah, Satrapi criticizes imperialism and American and British interference in Iran . [30]

As a very popular form of storytelling in the West, the graphic novel integrates text with imagery. While the use of visuals helps to interpret the author’s imagination, those images are also open to readers’ interpretation. In Persepolis, Satrapi remembers her past through a “process of visualization,” which indicates the multiplicity of ways her culture can be interpreted. [31] It also speaks about her exilic perspective, providing her with a hybrid identity with multitudes of lenses. Satrapi’s combination of dialogue, interior monologue, and image promotes myriad ways to understand Iranian culture. Satrapi presents Iranian culture as complex and filled with strong female figures, including the protagonist herself.

Women’s common struggle connects Satrapi to the struggle of other Iranian women writers, her foremothers despite their differences in time, language, and genre. Iranian women writers have depicted women’s struggles against the patriarchal system, traditional gender roles, and limitations for women under the Pahlavi regime and Islamic Republic. The struggle of women through different historical periods in Iran reflects the type of struggle the female protagonists face in novels written by Iranian women. Marji’s radical thoughts and her criticism of the sociopolitical discourse of Iran, particularly in the 1990s, represents the evolving generation of women performing an alternative role as the symbol of change and innovation.

Satrapi contextualizes sisterhood in her narrative and brings migrant women to visibility by showing her observation of discrimination and marginalization as an immigrant woman in Vienna. In Persepolis , Satrapi fairly represents the disciplinary nature of fundamentalism and oppression for women both in Iran and in the West. For example, she represents two “Guardians of the Revolution” in the streets of Tehran, whose jobs were “to arrest women who were improperly veiled,” such as herself (Figure 6). Later, the nuns in the Viennese religious school try to control the girls’ behavior in public (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 133, 177. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS: THE STORY OF A CHILDHOOD by Marjane Satrapi, translation copyright © 2003 by L’Association, Paris, France. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

By juxtaposing the visual imagery of Iranian and Austrian fundamentalists who are dressed in similar fashion, with head coverings and concealing clothing, Satrapi points out the similarities of religious fundamentalism, which oppresses women cross-culturally. This juxtaposition highlights the fact that while religious-based oppression occurs in Iran, similar oppression occurs in the West, though those living in the West often overlook the latter. This resonates with what Mohanty believes to be the importance of “cross-border feminist solidarities,” which are based on women’s struggles for emancipation in various parts of the world. [32] Though the religions are different, their power to oppress and subordinate women is grounds for alliance.

Satrapi’s struggle as a woman living in exile is portrayed through the moments that Marji faces racial discrimination in Vienna based on the stereotypes of women from the Global South. For example, Satrapi depicts her bitter experience when her Austrian boyfriend’s mom accuses Marji of “taking advantage” of her son; in Marji’s words, “She was saying that I was taking advantage of Markus and his situation to obtain an Austrian passport, that I was a witch” (Figure 7). When Marji is forced to leave her boyfriend’s house, she goes home and surprisingly finds similar aggression at her own house when her landlady calls her a prostitute (Figure 7). Later, her landlady accuses Marji of stealing her jewelry, saying that “I lost my brooch. I’m sure that you’re the one who took it.” [33] The narrative criticizes the condition of women in exile abroad in the West and the West’s treatment of immigrant women.

Figure 7. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 220, 221. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Persepolis is not aimed at vengeance for the author’s traumatic experience in the West; it is aimed at questioning the very idea of sisterhood through the book’s critical approach to women’s oppression in exile. Satrapi’s portrayal of racism resonates with Naghibi’s call for destabilizing and reinterrogating transnational feminism to eliminate race and class divisions between “the civilized nations” and “rogue nations.” [34] Persepolis calls for reconsideration both of sisterhood and of race as the foundation of transnational feminism, and urges its audience to not overlook the significance of an antiracist feminism anchored around women’s common force of resistance across the globe. Satrapi’s diverse and discursive manifestation of racial and cultural diversity through the black-and-white panels in Persepolis is in itself commentary on the reductive Western division of the world into black and white.

Iranian women’s unequal status at home, rooted in gender discrimination, and their marginalization in the West, rooted in Islamophobia and racial discrimination, is central to Satrapi’s model for change and reformation. Her critique of the representation of Iran and Iranian women in the West underscores how these misrepresentations create inequality between women of different cultures, which in turn problematizes sisterhood. Female bonding and friendship, which is portrayed at multiple points in her narrative both in Iran and in Vienna, is a direct reference to the significance of solidarity. Satrapi’s demand for inclusion and equality in Persepolis resonates with Naghibi’s argument on the significance of an “alternative model to sisterhood.” [35]

The power and importance of sisterhood in making peace and sharing pains and sorrows to resist oppression is portrayed at several points in Persepolis. For example, during the Iran–Iraq War (1980–88), Marji’s family host and support Mali’s family after their house is bombed during Iraq’s attack on the south of Iran. When Mali, a family friend, with her husband and two kids, knocks on the door of Marji’s family home in the middle of the night to seek shelter, Marji’s mom hugs Mali and says, “hey, it’ll be OK, calm down…you did the right thing to come here.” [36] They laugh and cry together to get through the devastation of wartime and to get Mali’s family back on their feet. [37] Later in Vienna, Marji’s classmate Julie introduces Marji to new friends with whom Marji feels loved and gains a sense of belonging, making her life more bearable. [38] Marji’s roommate, Lucia, noticing Marji’s loneliness before Christmas break, takes Marji to stay with her family in Tyrol for Christmas. After this trip, Marji loves Lucia like a sister (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis, 172. Graphic Novel Excerpt from PERSEPOLIS 2: THE STORY OF A RETURN by Marjane Satrapi, translated by Anjali Singh, translation copyright © 2004 by Anjali Singh. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

My own perspective as an immigrant scholar who has experienced life and work in Iran and the United States has been shaped by Eurocentric behavior aimed at marginalizing me and people like me. With the presidency of Donald Trump and the growth of Islamophobia after he called Iran a “terrorist nation,” the situation grew worse. At that time, I was teaching Persepolis in my World Literature class at the University of Arkansas and observed firsthand the power of Persepolis to transcend borders. Persepolis was welcomed by the students, who were accustomed to hearing and thinking about Iran as a land of horror and evil. As my students experienced, Persepolis opens the audience’s eyes to the differences that are historically and politically constructed. Indeed, Satrapi problematizes both Western and Iranian media in using political frames to portray the enemy by demonizing and dehumanizing the whole nation. [39] This is an example of her fairness in criticizing both governments in their policies, a criticism that points to the politics of differences in a global context. Her narrative doesn’t promote Islamophobia and hatred; it questions the political framework between Iran and the West in representing the other side as evil.

The transnational circulation of people’s lives, ideas, events, and culture through the eyes of Marji plays a significant role in facilitating for the Western audience an understanding of Iran and what it means to be an Iranian woman. As Amy Malek argues, “ Persepolis is an exemplary model of both memoir and Iranian exile culture in that it pushes the boundaries of both and that Satrapi’s position of liminality allows her to use a third space position from which to complete her cultural translation, in which she addresses issues of identity, exile and return.” [40] Mobilizing popular culture from the Middle East in the West for the first time, Persepolis draws attention to the relationship between the regions. This is in line with Mohanty’s argument on the necessity of uniting the voices of women in resistance around the world regardless of the divisions of race and class. Persepolis is a vivid picture of the Iranian sociocultural context concerning women’s issues during and after the Iranian Revolution.

The alternative representation of Iran that Satrapi provides without censorship invites the audience to rethink stereotypes of Muslim women as passive victims and of Iran as a backward and barbarian nation. The narrative is free from censorship and has not been co-opted to help the West to advance their agenda in the Middle East. Indeed, the transnational hero, Marji, breaks the barrier of ignorance and misunderstanding about the Middle East as Evil Other. By sharing her observation of events, women, and culture through images and words that communicate to the Western audience without the interference of governments, Marji enters the hearts and minds of readers around the globe. The oppression and struggle of Iranian women for equity and peace is a different struggle based on the specific sociopolitical atmosphere in Iran. However, what makes the narrative in Persepolis transnational and cross-border is its representation of women’s resistance and power during the political upheavals and wartime in Iran. Persepolis has great potential to shift the focus from understanding Iranian women as lacking agency, as they are presented in Western media or books like the bestseller Reading Lolita in Tehran . Persepolis marks the first time that Iran has been represented through images in a graphic novel created by a woman from the Middle East, and signifies the need for renewal and reshaping cultural exchange.

In conclusion, Persepolis ’s representation of contemporary Iran offers interdisciplinary ways to know Iran for the new generation. It opens the space for discussion on how gender, religion, and politics work in Iran. The narrative shows that to find solidarity in sisterhood, we need to understand our differences and appreciate our commonalities. The divisions between class, race, religion, culture, and ethnicity as shown in the narrative point to, as Mohanty discusses, the “politics of difference and commonality, and specifying, historicizing, and connecting feminist struggles.” [41] Persepolis educates the Western audience on Iran as a different civilization to explore. Satrapi stresses the significance of self-education at several points in the novel, saying that “one must educate oneself.” [42] In the transnational world we live in, education is the key to expanding our vision across geographical boarders. Persepolis offers hope that the progress of women’s rights can be made through mutual understanding and support in solidarity with sisters across the world.

What lies beyond the race, class, and culture divisions in my argument is the significance of storytelling that reflects resistance in exile. I believe that Satrapi’s experience of exile at home and abroad, the traumatic condition of marginalization, provides a sharp focus in the creation of her narratives that question the status quo and depict women’s nuanced resistance to oppression. The cost of Satrapi’s resistance appears in the author’s exile. While throughout history exiles share similar “cross-cultural and transnational visions,” as Said argues, [43] Satrapi’s Persepolis is a byproduct of the West’s imperialism and Islamophobia alongside religious fundamentalism in the twenty-first century, and stresses the common force of oppression. Persepolis represents the author’s observation of the disciplinary nature of fundamentalism and oppression against women both in Iran and in the West, contributing to Valentine Moghadam’s argument in her book Globalization and Social Movements: The Populist Challenge and Democratic Alternatives . Moghadam argues that the mobilizing forces of uniting women at the “macro level” and “micro level” create a “collective identity” to overcome the differences across the globe. [44]

The visualization of the estrangement, alienation, and homelessness through the exiled hero, Marji, cultivates the imagination to move beyond the self and differences. Drawing on cross-continental conversations amongst people and in particular women from around the world, Persepolis focuses on solidarity in exile. The contemporary themes of emigration, Otherness, exile, and identity connect Satrapi’s transnational narrative to the stories written by women from other cultures like The Distance Between Us: A Memoir by the acclaimed Mexican writer Reyna Grande and Americanah by Adichie. The global intersections and parallels in exile literature connect human experience cross-culturally, and manipulate transcultural visions in storytelling which connects women and culture to find solidarity and seek healing and collaboration. Persepolis is a provocative account of the Iranian people’s everyday life and concerns, much like those of many other people in the world, who struggle with their belief systems and those of their governments. Persepolis suggests that in order to maintain collective identity, we need to subscribe to women’s emancipation and gender equality in all cultures and nations. Persepolis provides a stellar example of the creativity and power of Iranian women writers’ storytelling abilities.

[1] Susan A. Mann, Doing Feminist Theory : From Modernity to Postmodernity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 362.

[2] Mann, Doing Feminist Theory , 363.

[3] Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York: William Morrow, 1994), 198.

[4] Edward W. Said, Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 184.

[5] On the differences between exile, refugees, expatriates, and émigrés, see Said’s discussion in Reflections on Exile , 181: “Although it is true that anyone prevented from returning home is an exile, some distinctions can be made among exiles, refugees, expatriates, and émigrés. Exile originated in the age-old practice of banishment. Once banished, the exile lives an anomalous and miserable life, with the stigma of being an outsider. Refugees, on the other hand, are a creation of the twentieth-century state. The word ‘refugee’ has become a political one, suggesting large herds of innocent and bewildered people requiring urgent international assistance, whereas ‘exile’ carries with it, I think, a touch of solitude and spirituality. Expatriates voluntarily live in an alien country, usually for personal or social reasons. Hemingway and Fitzgerald were not forced to live in France. Expatriates may share in the solitude and estrangement of exile, but they do not suffer under its rigid proscriptions. Émigrés enjoy an ambiguous status. Technically an émigré is anyone who emigrates to a new country. Choice in the matter is certainly a possibility. Colonial officials, missionaries, technical experts, mercenaries, and military advisers on loan may in a sense live in exile, but they have not been banished. White settlers in Africa, parts of Asia and Australia may have been exiles, but as pioneers and nation-builders, they lost the label ‘exile.’”

[6] Chandra Talpade Mohanty, “‘Under Western Eyes’ Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles,” Signs 28 (2003): 499–535. Quote on p. 530.

[7] Chandra Talpade Mohanty, “Transnational Feminist Crossings: On Neoliberalism and Radical Critique,” Signs 38 (2013): 967–91. Quote on p. 977.

[8] Mohanty, “Transnational Feminist,” 987.

[9] Mohanty, “Transnational Feminist,” 987.

[10] Nima Naghibi, Rethinking Global Sisterhood: Western Feminism and Iran (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), xvii.

[11] Naghibi, Rethinking Global , 141–46.

[12] Persis M. Karim, “Reflections on Literature after the 1979 Revolution in Iran and in the Diaspora,” Radical History Review 105 (2009): 151–55. Quote on p. 152.

[13] Said, Reflections on Exile , xxxv.

[14] Marjane Satrapi, The Complete Persepolis (New York: Pantheon, 2004), 322.

[15] Said, Reflections on Exile , xxxv.

[16] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 302.

[17] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 297.

[18] Said, Reflections on Exile , xxxv.

[19] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 177.

[20] Chimamanda N. Adichie, “The Danger of a Single Story,” July 2009, Oxford, UK, TED, transcript, 18:33, www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.

[21] Adichie, “Danger of.”

[22] Adichie, “Danger of.”

[23] Diego Maggi, “Orientalism, Gender, and Nation Defied by an Iranian Woman: Feminist Orientalism and National Identity in Satrapi’s Persepolis and Persepolis 2,” Journal of International Women’s Studies , no. 1 (2020): 89–105. Quote on p. 89.

[24] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 106.

[25] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 177.

[26] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 178.

[27] Farzaneh Milani, Words Not Swords: Iranian Women Writers and the Freedom of Movement (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2011), 231.

[28] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 5, 301, 333.

[29] Hamid Dabashi, Brown Skin, White Masks (London: Pluto, 2011), 23.

[30] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 19, 20.

[31] Nima Naghibi, Women Write Iran: Nostalgia and Human Rights from the Diaspora (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 107.

[32] Mohanty, “Transnational Feminist,” 987.

[33] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 233.

[34] Naghibi, Rethinking Global , 141–46.

[35] Naghibi, Rethinking Global , 109.

[36] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 90.

[37] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 91, 92.

[38] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 166, 167.

[39] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 322.

[40] Amy Malek, “Memoir as Iranian Exile Cultural Production: A Case Study of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis Series,” Iranian Studies 39 (2006): 353–80. Quote on p. 369.

[41] Mohanty, “Transnational Feminist,” 977.

[42] Satrapi, Complete Persepolis , 327.

[43] Said, Reflections , 174.

[44] Valentine M. Moghadam, Globalization and Social Movements: The Populist Challenge and Democratic Alternatives (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2020), 164.

Latest News

- Editorial & Advisory Board

- Iran Namag Book

- Editorial Advisory Boards

Subscribe | Login

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Is This the End of Academic Freedom?

By Paula Chakravartty and Vasuki Nesiah

Dr. Chakravartty is a professor of media, communication and culture at New York University, where Dr. Nesiah is a professor of practice in human rights and international law.

At New York University, the spring semester began with a poetry reading. Students and faculty gathered in the atrium of Bobst Library. At that time, about 26,000 Palestinians had already been killed in Israel’s horrific war on Gaza; the reading was a collective act of bearing witness.

The last poem read aloud was titled “If I Must Die.” It was written, hauntingly, by a Palestinian poet and academic named Refaat Alareer who was killed weeks earlier by an Israeli airstrike. The poem ends: “If I must die, let it bring hope — let it be a tale.”

Soon after those lines were recited, the university administration shut the reading down . Afterward, we learned that students and faculty members were called into disciplinary meetings for participating in this apparently “disruptive” act; written warnings were issued.