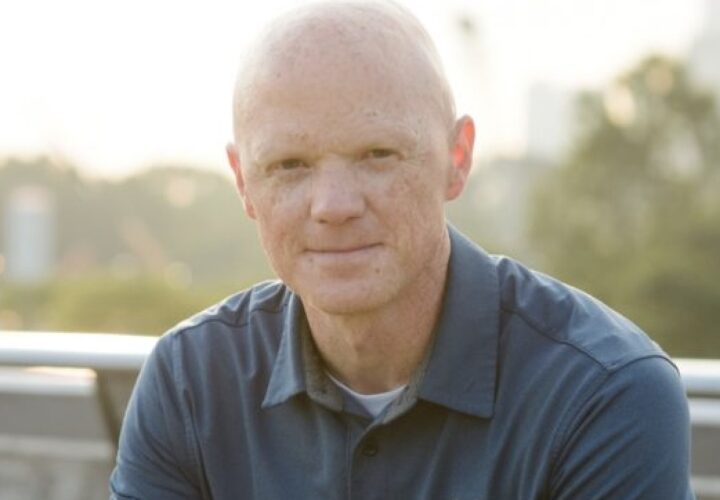

Mattson, Expert on Brain Aging, Science of Fasting, Retires

Dr. Mark Mattson recently retired from NIH after almost 20 years.

Photo: Ernie Branson

Dr. Mark Mattson, renowned for his research on brain aging, Alzheimer’s disease and the health benefits of calorie restriction and intermittent fasting, retired from the National Institute on Aging recently. During his distinguished career, Mattson inspired peers and lab teammates with his diligent work ethic and research productivity. He remains recognized as one of the world’s most highly cited neuroscientists, with a long track record of achievements and numerous awards.

In June, an international symposium drew dozens of Mattson’s current and past colleagues and mentees to Johns Hopkins’ Mountcastle Auditorium to celebrate his contributions to science. Throughout the day-long symposium, speakers recalled Mattson as a mentor who led by example.

“I do not have enough words to express my gratitude to Mark for his excellent contribution to the science, for his collaborative and generous spirit toward other scientists, and for being such a good colleague, friend and mentor,” said Dr. Luigi Ferrucci, NIA scientific director. “His life is an inspiration and an example to all, and I am certain that his next journey will be adventurous and successful.”

During his almost 20 years at NIA, Mattson led the Neuroscience Research Laboratory, which focused on understanding what goes wrong in the brain in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases and stroke. His team made numerous discoveries that revealed the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which intermittent metabolic challenges—exercise and intermittent fasting—enhance cognition and protect the brain against age-related dysfunction and degeneration.

Using mouse models, Mattson and his team found that both dietary energy restriction and intermittent fasting play a significant role in delaying and slowing the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. These findings resulted in several novel therapeutic approaches and, more recently, early-stage clinical trials testing calorie restriction and fasting diets in humans.

A native of Minnesota, Mattson received his Ph.D. in biology from the University of Iowa and then began his career at the Sanders-Brown Research Center on Aging at the University of Kentucky Medical Center. In 2000, he became chief of NIA’s Laboratory of Neurosciences with a joint appointment at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Dr. Jonathan Geiger, Chester Fritz distinguished professor at the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences, recalled being impressed with Mattson’s productivity while they were colleagues at Kentucky. “Once I made the mistake of asking Mark what his secret to success was,” Geiger said. “He made it clear to me that there is no secret, no trick, to being successful—it takes dedication and hard work!”

Past colleagues and mentees honored Mattson (front row, 7th from left) at a symposium in his honor on June 3.

Photo: Chip Rose

Mattson is looking forward to continuing his teaching at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine’s graduate neuroscience program. His future projects also include writing books based on his research and helping plan future studies on intermittent fasting in patients with chronic diseases.

“I deeply appreciated the opportunity to visit with former lab members and collaborators who enriched my life during the past four decades,” Mattson said. “It was wonderful to reminisce about our collective contributions to the fields of neuroscience and aging, and to contemplate our future directions in life and science. This was a highly fulfilling segment of my life and I will always have fond memories of my experiences with the many colleagues and friends that I had the great fortune of working with at NIA.”

Home » Latest Stories: Alzheimer’s, Dementia and Brain Health » Article » Neuroscientist Mark Mattson: Intermittent Fasting and Brain Health

Text to speech

Neuroscientist Mark Mattson: Intermittent Fasting and Brain Health

Johns Hopkins neuroscientist Mark Mattson, PhD, shares his insights on what we know so far — and the questions still to be answered — about intermittent fasting and brain health.

Some cases of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia are inevitable, thanks to genetics and other factors yet unknown. But one thing scientists have established: A staggering two out of five cases of dementia should be preventable through addressing a number of risk factors, most of which are within our control. In the wake of this finding, the research community is increasingly focused on understanding what lifestyle changes are most effective when it comes to boosting brain health and lowering Alzheimer’s risk. Among those changes, the neuroscience community is exploring diet, and in particular, intermittent fasting.

This particular eating pattern — which involves switching back and forth between fasting and eating on a regular schedule — has shown promising benefits in animal studies for a host of health conditions, including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and even neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s. Of course, animal studies do not always translate to human health, and more research is certainly needed to determine the effects of intermittent fasting on brain health. But today, animal studies are paving the way for clinical research in humans.

Mark Mattson, , PhD, a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University and the author of The Intermittent Fasting Revolution: The Science of Optimizing Health and Enhancing Performance (Feb. 2022), sat down with Being Patient Editor in Chief Deborah Kan to talk about the biological mechanisms that underpin this eating habit’s potential in boosting brain function — and health at large.

Mattson also discusses the questions that scientists still have yet to answer about the impacts of intermittent fasting on brain health. Watch a recording of the talk below, or scroll for a transcript of the conservation.

Being Patient: What do we know about intermittent fasting, and why, if at all, is it beneficial for health?

Mark Mattson: We know a lot about intermittent fasting from the perspective of helping people get their weight down and improve their glucose regulation.

Many studies in humans compare three meals a day plus snacks to restricted eating — or another approach we’ve used with a group in England a long time ago [that’s] now called 5:2 intermittent fasting (two days a week eating only one moderate-sized meal each day) — [show that] those [two latter] eating patterns have sufficient time with no food to cause a metabolic switch from using glucose in the liver to using ketones, which come from fats.

Ketones are a good fuel for neurons. We know that for sure. We also know that ketogenic diets and also fasting can suppress epileptic seizures. In fact, ketogenic diets are still used for some patients who don’t respond well to epilepsy drugs. Work in my lab in animals [has] shown what’s going on in the brain to explain that beneficial effect of ketones.

Being Patient: What about for brain health, specifically?

Mark Mattson: I have to get in briefly to a little neuroscience. If I were to ask your listeners or viewers what neurotransmitters they have heard of, they might say dopamine or serotonin. But it turns out the most abundant and important neurotransmitter in the brain is glutamate. It’s an amino acid — an excitatory transmitter — and over 90 percent of the neurons throughout the brain use glutamate. Those glutamatergic neurons degenerate in Alzheimer’s disease.

Actually, it turns out that Alzheimer’s patients have increased incidence of seizures, like 20- to 30-fold over age-matched people without Alzheimer’s. There’s this hyper-excitability — unconstrained, improperly regulated activity in those excitatory circuits. What intermittent fasting does is it quiets those neurons by actually increasing the activity of inhibitory neurons. They use the neurotransmitter GABA.

A lot of studies in animals have shown that compared to ad libitum feeding, intermittent fasting can enhance learning and memory, and even has an anti-anxiety effect once the animals are adapted to the new intermittent fasting eating pattern.

Being Patient: Glucose is the normal fuel of our brains, but we can switch energy sources to ketones. So, is changing energy sources better for our brains, or is it that ketones are a better source of fuel for our brains?

Mark Mattson: Both are true: those aren’t mutually exclusive. You said that our brain cells normally use glucose. That’s true if we’re eating diets that have carbs in them. If we’re eating a ketogenic diet, or if we’re fasting, the neurons switch from using glucose to ketones. That’s been clearly demonstrated in humans by Steve Cunnane where he had people switch to ketogenic diet and he measured both glucose and ketone utilization and showed there’s that switch.

With Alzheimer’s, neurons have problems using glucose. That’s been known for decades and decades. Based on Dr. Cunnnane’s work and some of our’s in animals, we think that neurons are still able to use ketones even in humans and animals that are symptomatic with Alzheimer’s disease.

Being Patient: The idea is that by keeping our brains well fed, we create an environment where things are less likely to go wrong, such as the build-up of beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles; if we have a healthy level of energy source, then perhaps it will be harder to reach that tipping point where the neurodegenerative process or pathology begins. Is that correct?

Mark Mattson: Very well said. Experimentally, one can show that if you compromise the energy levels in neurons, and this is in animal studies or neurons in a dish, then they produce more amyloid beta peptide and they’re more vulnerable to being damaged by the amyloid. They’re also more vulnerable to hyperexcitability and what we call excitotoxic damage.

Being Patient: What is the state of the research in intermittent fasting?

Mark Mattson: I’m really excited about all this because just in the last five to seven years, there has been an exponential increase in the number of human studies.

I was invited with a colleague of mine to write an article for the New England Journal of Medicine a few years ago. They had two reasons for inviting us to do it. One was there’s not enough data from humans, particularly people with obesity or insulin resistance, to merit a review article. But also, a lot of physicians hadn’t heard of intermittent fasting or they had no idea that there’s actually a lot of science, including an increasing number of clinical trials.

Now, if you go on ClinicalTrials.gov , which is where you go to find all the ongoing trials, and if you put in the words intermittent fasting, there’s like 150 trials ongoing, ranging from various cancers, diabetes, obesity. mild cognitive impairment and some inflammatory neurological disorders like multiple sclerosis.

What happened was that the animal research really didn’t start till the late ’80s, early ’90s. It took a couple of decades to get a lot of animal data. Then, human studies started and they’re taking off now.

Being Patient: Looking ahead, what more do we need to know about intermittent fasting?

Mark Mattson: For normal people who don’t have Alzheimer’s disease, we don’t know much at all, except that they can undergo this metabolic switch from glucose to ketones in terms of neurons in their brain using them.

We have a trial that’s almost done at the National Institute on Aging, where we took people between the ages of 55 and 70 with obesity. They’re also insulin resistant. We put them on either 5:2 intermittent fasting or [a] control eating pattern, which [are] breakfast, lunch and dinner. Before we started them in the study and then at the end of two months, we did a bunch of cognitive tests and other psychological tests. We’re doing functional magnetic resonance imaging to look at neural network activity in their brains. And we’re doing some other things, for example, analyzing their cerebrospinal fluid to see if some of the things we saw change in the brain in animals with intermittent fasting also change in humans. I can’t say anything about it yet — because the study’s not done, we haven’t published it — except that it’s looking encouraging.

But, more study is needed. There needs to be studies focusing on the brain and humans. There are a lot of anecdotal things where people will say they skip breakfast and it’s been a couple months now; in the morning hours, they feel like they’re really productive and they’re able to think clearly and so on. But from humans, it’s a lot of anecdotal things and not any true scientific data.

Being Patient: Without fasting, can we use ketones supplements like beta-hydroxybutyrate as an energy source for the brain?

Mark Mattson: The beta-hydroxybutyrate ester, a colleague of mine at NIH (National Institutes of Health) developed that ketone ester. This was when I was a lab chief at NIH. I was a lab chief there for 20 years and then I retired, and now I’m on the faculty at Hopkins. We tested that ketone ester in our mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. It had beneficial effects.

Then, it’s now being tested by Steve Cunnane in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and also a neurologist that I mentored is going to test it in patients with mild cognitive impairment or early Alzheimer’s disease.

Being Patient: In the meantime, what is your advice for improving one’s brain health?

Mark Mattson: Number one: physical exercise. [Then, there’s] cognitive exercise — particularly what you and I are doing now, engaging in intellectually challenging things — and moderation in calorie intake and eating a healthy diet.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at [email protected]

Please help support our mission.

More articles like this....

Can Ketones Fight Alzheimer’s? The Keto Diet and Brain Health

Ben Bikman: Understanding Metabolism For Better Brain Health

Does Sugar Fuel Alzheimer’s? Brain Glucose Linked to Memory Loss

Leave a reply cancel reply.

We are glad you have chosen to leave a comment. Please keep in mind that comments are moderated according to our comment policy .

Privacy Overview

Sign up now for our free weekly email with in-depth reporting on topics important to patients and caregivers of Alzheimer's & other dementias.

- First Name First

- Relationship with disease Relationship with disease Patient Professional caregiver Family caregiver Relative or friend of patient Medical professional Genetic carrier Other

- Consent Yes, also sign me up to the Being Patient Registry to learn more about upcoming research studies on brain health and dementia.

- History and Mission

- Structure and Cores

- Annual Report

- Media Guide

- Guiding Principles for Diversity

- Land Acknowledgement

- Volunteer for a study

- Open Studies

- Brain Donation

- Classes and Series

- Precious Memories Choir

- Mind Readers Book Club

- What is Alzheimer's disease?

- COVID-19 Brain Health Resource Guide

- Resources for People with Dementia and Care Partners

- How to get a diagnosis

- Raising awareness of Alzheimer’s disease in Wisconsin’s Indian Country

- Dementia Matters

- Dementia Matters COVID-19 Special Series

- Biomarker videos

- Request a Talk

- Professional Education

- Black Leaders for Brain Health

- Research Services and Resources

- Apply for Resources

- Data Dictionary

- Developmental Projects

- Acknowledging the Center

- IEA Innovation Fund

- Funded Pilot Grants, 2006-2019

- Internal Center Links

- Referring Patients to Research

- Updates in Dementia Care E-newsletter

- Dr. Daniel I. Kaufer Lecture

- How to join a research lab

- REC Scholar Program

- Research Day 2024

- Junior Fellowship

- Professional Development Award

- Lightning Funding Award

- Health Reporting Internship

Intermittent Fasting and Its Effects on the Brain

As intermittent fasting has risen in popularity over the last decade, researchers have been exploring its long-term effects on physical health. Dr. Mark Mattson joins to discuss his research on metabolic switching, caloric restrictions, and the cognitive benefits from intermittent fasting. Guest: Mark P. Mattson, PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Department of Neurology

Note: It is best to talk with your healthcare provider before engaging in intermittent fasting. Episode Topics:

- Defining Intermittent fasting: 1:08

- How long does it take for a metabolic switch? 2:02

- How is this process different from normal dietary recommendations? 3:44

- What did you find in your research on the effects of intermittent fasting on health? 5:36

- Are there cognitive benefits to intermittent fasting? 8:12

- Can intermittent fasting and caloric restrictions improve the brain’s health? 9:49

- How does our modern lifestyles affect our brain and overall health? 16:07

- Is there any evidence that one way of intermittent fasting is better?17:54

- Are there any long-term consequences of intermittent fasting? 20:30

- What do you do in your life to improve your brain health? 22:39

Subscribe to this podcast through Apple Podcasts , Spotify , Podbean , or Stitcher , or wherever you get your podcasts.

The New York Times interviewed Dr. Mattson for the article "The Benefits of Intermittent Fasting," which was published online on February 17, 2020.

Read "Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease" published December 26, 2019, in The New England Journal of Medicine. (Free account required.)

Intro: I'm Dr. Nathaniel Chin, and you’re listening to Dementia Matters , a podcast about Alzheimer's disease. Dementia Matters is a production of the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center. Our goal is to educate listeners on the latest news in Alzheimer's disease research and caregiver strategies. Thanks for joining us.

Dr. Nathaniel Chin: Our guest today is Dr. Mark Mattson, a neuroscientist at John Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. Dr. Mattson studies the molecular and biochemical causes of degenerative brain diseases, like Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease, as well as healthy brain aging at the cellular and molecular levels. Dr. Mattson has done extensive research into intermittent fasting and how it affects brain aging and cognition. The mainstream health media has definitely made intermittent fasting trendy in the last few years, and I'm excited to hear from a scientist if the data supports the hype. Thank you Dr. Mattson for taking the time to join me on Dementia Matters .

Dr. Mark Mattson: Glad to be here, Nathaniel.

Chin: So can you start out by defining intermittent fasting and explain what happens in the body when someone follows an intermittent fasting lifestyle?

Mattson: Intermittent fasting is an eating pattern in which the individual frequently goes for extended periods of time with no energy intake, periods of time that are sufficient to deplete liver energy stores which is glucose and then switch to using fats and the ketones derived from the fats in your fat cells. The typical American eating pattern is three meals a day plus an evening snack in many cases, and with that eating pattern there's not any time interval between meals sufficient to cause this metabolic switch from glucose to fats and ketones.

Chin: And so that's one of the main concepts is that instead of our body utilizing glucose, in this intermittent fasting you'd be using fats and triglycerides is that right?

Mattson: Yes.

Chin: And how long does it take to make that switch when you mention metabolic switching. How long does one need to go to make it?

Mattson: In a person who's just not exercising and kind of normal daily activities, it takes ten, twelve hours to have that metabolic switch occur. If they, for example, get up in the morning and go running after having slept for eight hours, then probably gonna have the metabolic switch very soon after they begin running.

Chin: I see, and that's a really good point. So it's not really just about the duration in which you're not eating, but it's your other behaviors and lifestyle factors that may influence the actual switch.

Mattson: Yeah and with exercise, if there's glucose in the liver available, that's preferentially used by your muscle cells and then during fasting your muscle cells will switch to using triglycerides and ketones. From an evolutionary perspective, this allows animals to go extended time periods of many days to even weeks with no food intake. And undoubtedly individuals, animals evolved so that their bodies and brains were able to function very well, perhaps optimally in a food deprived state. Otherwise, they wouldn't have been successful in acquiring food.

Chin: And so you mentioned two key words there. You mentioned fasting and calorie restriction as well as ketones, and so I'm wondering how is this process of intermittent fasting different than our general caloric restriction and this ketogenic diet that we hear about in the news?

Mattson: Yeah, it's possible to have a calorie restricted diet without any metabolic switching occurring. So, for example, if you say you're overweight and you're taking in 2,400 calories a day. If you cut back to 2,000 but you still eat breakfast, lunch, dinner, a snack, then you're not going to deplete the liver glucose stores because every time you eat - if there's carbohydrates that you're eating - then you replenish the liver store. So it's possible to have chloric restriction without the metabolic switch occurring. We think this metabolic switch is important and we can go into more detail on that. Not from just the standpoint of ketones themselves being used as an energy source by ourselves but also there's numerous signaling pathways that are activated that we think, many of them are independent of ketones.

Chin: And so intermittent fasting is different though than a ketogenic diet, is that right?

Mattson: Yes, of course. Ketogenic diet: ketones are elevated, blood glucose remains low, and so cells are using - including brain cells - use a lot of ketones on a ketogenic diet. But some of the signaling pathways, for example, in the brain that we study may be independent of ketone elevation.

Chin: Okay, and so actually late last year the New England Journal of Medicine published an article in which you offered this extensive review of the scientific literature relating to the effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease. I know you were just alluding to this and so I'm wondering, what did you find in regards to intermittent fasting and its effect specifically on brain health and cognition?

Mattson: Well, as is usually the case, there's many more studies being done in animals than humans and the New England Journal, of course, focuses on humans. So from the human perspective there's solid evidence that in people who are obese or overweight that switching their eating pattern to an intermittent fasting eating pattern can enable them to lose weight and particularly lose fat and improve their glucose regulation, improve insulin sensitivity. So there's been now dozens of studies in overweight or obese humans. There have been fewer studies in normal weight humans, and the studies that have been done actually focused on resistance training and whether people who do weight lifting can build muscle mass well on an intermittent fasting eating pattern. The answer is yes. And then - but as far as human diseases, some clinical trials have been done in certain disorders; asthma, multiple sclerosis, which are inflammatory disorders as are a lot of diseases. There's also numerous trials going on in cancer. there's a lot of evidence from animal studies and just knowledge of cancer cells and their energy requirements that suggest that drugs that people are given in their chemotherapeutic treatments or radiation treatments - the vulnerability of cancer cells to those toxic treatments can be enhanced if the person is in a fasting state or an intermittent fasting eating regimen so yeah. And then also in human studies, there's pretty strong evidence of - let's say solid evidence - that cardiovascular risk factors, blood pressure and blood lipid profiles, can be improved by switching from normal eating pattern to intermittent fasting.

Chin: And in your paper in the New England Journal, you mentioned that there have been some studies to show cognitive benefits of people who are doing intermittent fasting and that their performance on some memory tests like verbal memory actually improved during the intermittent fast.

Mattson: Yeah, the studies are limited. There's one study in Germany, which I think the one that I cited in the New England Journal article. There's other studies ongoing, including one that my colleague Dimitrios Kapogiannis at the National Institute on Aging is heading, where what we're doing is - it turns out that overeating and diabetes and insulin resistance are risk factors for cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. So in the study we're doing at the NIA, we're taking subjects at risk for cognitive impairment and A.D. because of their age - they're between 55 and 70 years old - and their metabolic status - they’re obese and insulin resistant - and then we randomly assign them to either Control, arm which is advice for a healthy eating, or intermittent fasting arm, which is two days a week, eating only 500 calories on those two days which is not near enough to keep the liver glucose stores supplied. And so there's two days a week they're in a ketogenic state. Study’s almost done, but we can't really say anything about the results yet.

Chin: You do mention in your paper that there is evidence, as far as neurodegenerative disorders, that intermittent fasting and caloric restriction can improve sort of brain resilience or can improve the brain's health. Could you speak to some of those mechanisms of how intermittent fasting could actually help the brain?

Mattson: Yes, and this is based on animal studies and animal models of A.D. and Parkinson's so there's multiple mechanisms. One is that intermittent fasting can enhance neurotrophic factor signaling particularly brain derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF, which is known to be important for cognition and - actually it's important also because it has kind of an antidepressant effect. The most commonly used antidepressant drugs are mediated by BDNF so that's one mechanism. BDNF is known to enhance the resistance of neurons to stress and to promote the formation and maintenance of synapses. Okay, so then another mechanism is that the intermittent fasting... what it does - during the fasting period nerve cells in the brain, they reduce their overall uptake of proteins and production of new proteins. They go into kind of “conserve resources” mode where they're not actually growing during the fasting period but they're reducing protein synthesis by suppressing a pathway called the MTOR pathway. And then at the same time they're increasing a process called autophagy, which is a mechanism whereby the nerve cells recycle molecules in the cells or even mitochondria, the energy producing compartment of the cells. Then during the feeding period, the cell goes into a growth mode. We think from the animal studies that that's when actually new synapses are formed and the nerve cells grow and enhance connections so forth. A third mechanism is to enhance DNA repair. There's some evidence that - well there's a lot of evidence - during aging, there's increased accumulation of damaged DNA in our genome. This is why cancer risk increases during aging, at least part of the reason why that there's increased mutations in cells that aren't repaired and therefore there's increased chances of a cell becoming cancerous. We found intermittent fasting and exercise enhanced DNA repair in the brain as well.

Chin: So it seems that intermittent fasting not only helps the whole body by improving insulin sensitivity, helping with weight loss, reducing blood pressure and risk for diabetes, but then there are some very specific effects that can happen within the brain.

Mattson: One thing we found is really interesting. Very recently, we had a paper in a journal called Nature Communications where we found that intermittent fasting - well this is very important for the people listening - it takes people several weeks to a month to adapt to an intermittent fasting eating pattern so that they are no longer hungry and irritable during the time period with their previous eating pattern that they would have been eating. For example, if someone wants to adopt an intermittent fasting eating pattern where they skip breakfast and eat all their food between noon and six or seven PM each day so that they're fasting for 16-17 hours a day, then when they first start that skipping breakfast they're going to be very hungry in the morning and irritable, maybe not even - having maybe having trouble concentrating. But by two weeks to a month, those initial side effects if you will, or adaptations, will disappear. We found by looking at the brains of mice that, with the same time course, there's an enhancement of activity of an inhibitory neurotransmitter called GABA, which has an anti-anxiety effect. It turns out in Alzheimer's disease - and really my lab was the the first one way back in the late ‘80s early ‘90s to provide evidence for that - and Alzheimer's disease, there's a problem with nerve cell networks in the brain controlling their excitability so that certain circuits become uncontrollably excited, hyper-excited, and in fact patients with Alzheimer's disease, they have a greatly increased incidence of epileptic seizures compared to age-match control subjects. And that's because we think there's impairment in GABA, the inhibitory neurotransmitter, signaling or even death of the neurons - they use GABAs and neurotransmitters. So intermittent fasting will constrain excitability within normal limits and protect neurons against what we call excitotoxicity, which gets a little more complicated. But in the brain and Alzheimer's, of course, a lot of focus is on the Amyloid-Beta peptide, which forms the plaques and intracellular TAU tangles. My own opinion is that A-Beta and certainly TAU are downstream. That is, occur after other important changes that contribute to the increased accumulation of the amyloid. But once the amyloid starts to accumulate then it makes neurons even more vulnerable to hyperexcitability and what we call excitotoxicity. In fact one of the one of the drugs that's used to treat Alzheimer's patients is a drug that blocks a certain type of excitatory glutamate receptor. That's a drug called memantine.

Chin: And you know, you mentioned that this first month of an intermittent fast is difficult for people. I notice that you put that in your paper as well as far as practical considerations. But you also speak to the research referencing brain evolution and how this practice of intermittent fasting is meant to optimize our brain function. However the modern lifestyle kind of gets in the way of that, and so what is it about our modern lifestyles that make it difficult to do intermittent fasting or actually negatively impact our brain?

Mattson: What makes it hard to do is that most of us, including me, we were raised in family where the normal eating pattern was three meals a day and oftentimes ice cream after dinner. As everyone knows what you learn when you're a kid you tend to stick with, whether it's... you know anything, religion, or just habits, you know. Exercise, in general kids who are brought up in families where the parents exercise, they're more likely to exercise. So yeah this is a long-standing eating pattern that arose way back probably nine, ten thousand years ago when the agricultural revolution took hold and people settled down and farmed domesticated plants and animals and were able to store food so that they could wake up in the morning and they'd have food to eat. On the other hand, from an evolutionary perspective, breakfast is the least likely meal. That is to say, animals in the wild don't wake up and breakfast is waiting for them. They have to work for it.

Chin: You also mentioned, too, that one of the potential barriers to intermittent fasting is that most healthcare providers are not really trained to provide specific interventions, intermittent fasting interventions. You do mention some of the options and you mentioned them here today in the podcast of this, having two days a week where you restrict how many calories. But there are other options, too, where you do not eat for 16 to 18 hours. Is there any evidence that one is better than the other?

Mattson: No. In humans, there's been no studies yet within the same study that directly compared, you know in other words, have three arms to the study control five-two intermittent fasting or daily time-restricted eating approach and, you know, so same group of people and look at same endpoints. So that hasn’t been done. But we do know that definitely sedentary overindulgent lifestyles are not good for the brain just like they're not good for other organ systems. It makes sense that the converse is true; that is exercise and moderation and energy intake and intermittent fasting compared to normal eating pattern will be beneficial. We don't - it'll be interesting to do studies in normal healthy subjects, normal weight, say people who exercise to see if there's any additional benefits of intermittent fasting for endpoints of that interest, whether it's cognition or endurance. There's a lot of interest in the exercise community in intermittent fasting now. Because it's emerging that at least with endurance events, marathon certainly, Tour de France type things, that if you start the event in a fasted state where you've already switched to using the fats coming from your fat cells then you're able to maintain performance throughout the event. Whereas if you're taking essentially glucose, carbohydrates, you know if you, before the event and then different times during the event, it causes these well - first of all the ketones don't go up but then if you do deplete the glucose then you go into a period of poor performance until the metabolic switch takes hold. So I've had some interest in that. And we did studies in animals running on treadmills daily for two months with them on either intermittent fasting or ad libitum feeding eating patterns. At the end of the two months, the animals that were on the intermittent fasting eating pattern had better endurance when we tested their maximum, how far and how long can they run on the treadmill.

Chin: That's a pretty important finding. So not only are we talking about preventing disease, but potentially talking about enhancing one's performance in their current state.

Mattson: Yeah, yeah.

Chin: Do we know the long-term consequences of intermittent fasting and metabolic switching? Mattson: In animals, we do, but there's a caveat with this, more than one. So in animals, if we start with young or even middle-aged rats or mice and you put them on intermittent fasting eating pattern - the most commonly used one in the rodents is every other day fasting, 24-hours fasting, 24-hours food is always available and this keeps switching back and forth - they can live up to 50 percent longer if they're on the intermittent fasting eating pattern. However the control eating pattern in all animal studies is ad libitum feeding, that is they always have food available and they actually overeat and become fat. If you look at lab rats and mice, particularly as they get middle-aged, they gain a lot of weight and a lot of fat. The animal studies are really asking the question, if you take an obese or overweight and fairly sedentary animal and you switch them to intermittent fasting eating pattern, they live longer. We have found - we did do some studies where we compared daily calorie restriction to intermittent fasting, both of which are beneficial, and we did find greater improvement in insulin sensitivity with the intermittent fasting compared to daily calorie restriction. So I guess you know the take home message there with humans - and in normal weight humans we don't know for sure, but maybe they might benefit from intermittent fasting as they age well.

Chin: I guess, you know, one of the questions I like to ask my interviewees during this podcast, Dr. Mattson, is what they do in their own life. And with you being an expert in this field, I wonder do you practice intermittent fasting and are there other things that you do to maintain brain health and reduce your risk of neurodegenerative disease?

Mattson: I don't eat breakfast and most days I eat all my food within, it varies but, six to seven or eight hour time window, usually it's about six to seven hours. I spread it out so I'll, you know, eat around lunch time or so and then late afternoon. I don't eat everything at once, I kind of spread it out so I can get enough calories to maintain my body weight which is low to start with. Then exercise is very good for the brain. Unfortunately for me now, I got in a mountain bike accident and I'm recovering from surgeries and so I haven't been able to get much aerobic exercise. I can tell, as well as anyone else who exercises regularly and then isn't able to kind of test that, there's a big effect of exercise on the brain. So those are the two things. Then, of course, for Alzheimer's disease keeping your mind intellectually and socially engaged is important. There's good epidemiological evidence for that and that's consistent with what we know from animal studies as well.

Chin: And so likely a combination of all of these things will make a difference. With that, you know, I'd really like to thank you for being on Dementia Matters and as more of these studies come out, I hope to have you back on the show.

Outro: Dementia Matters is brought to you by the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center. The Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center combines academic, clinical, and research expertise from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. It receives funding from private university, state, and national sources, including a grant from the National Institutes of Health for Alzheimer's Disease Centers. This episode was produced by Rebecca Wasieleski and edited by Bashir Aden. Our musical jingle is "Cases to Rest" by Blue Dot Sessions. Check out our website at adrc.wisc.edu . You can also follow us on Twitter and Facebook . If you have any questions or comments email us at [email protected] . Thanks for listening.

Updated on March 25, 2024

Information For

Participants & Families Brain Donors & Families Caregivers Researchers Providers Media Employees

Contact Us Join a Research Lab Subscribe to E-news Give

This website may not display properly if you are using any version of Internet Explorer Feedback, questions or accessibility issues: [email protected]

Privacy Notice | © 2024 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

On the site

- health & fitness

The Intermittent Fasting Revolution

The Science of Optimizing Health and Enhancing Performance

by Mark P. Mattson

ISBN: 9780262545983

Pub date: April 4, 2023

- Publisher: The MIT Press

248 pp. , 5 x 8 in , 20 b&w illus.

ISBN: 9780262046404

Pub date: February 1, 2022

ISBN: 9780262368179

- 9780262545983

- Published: April 2023

- 9780262046404

- Published: February 2022

- 9780262368179

- MIT Press Bookstore

- Penguin Random House

- Barnes and Noble

- Bookshop.org

- Books a Million

Other Retailers:

- Amazon.co.uk

- Waterstones

- Description

How intermittent fasting can enhance resilience, improve mental and physical performance, and protect against aging and disease.

Most of us eat three meals a day with a smattering of snacks because we think that's the normal, healthy way to eat. This book shows why that's not the case. The human body and brain evolved to function well in environments where food could be obtained only intermittently. When we look at the eating patterns of our distant ancestors, we can see that an intermittent fasting eating pattern is normal—and eating three meals a day is not. In The Intermittent Fasting Revolution , prominent neuroscientist Mark Mattson shows that intermittent fasting is not only normal but also good for us; it can enhance our ability to cope with stress by making cells more resilient. It also improves mental and physical performance and protects against aging and disease. Intermittent fasting is not the latest fad diet; it doesn't dictate food choice or quantity. It doesn't make money for the pharmaceutical, processed food, or health care industries. Intermittent fasting is an eating pattern that includes frequent periods of time with little or negligible amounts of food. It is often accompanied by weight loss, but, Mattson says, studies show that its remarkable beneficial effects cannot be accounted for by weight loss alone.

Mattson—whose pioneering research uncovered the ways that the brain responds to fasting and exercise—explains how thriving while fasting became an evolutionary adaptation. He describes the specific ways that intermittent fasting slows aging; reduces the risk of diseases, including obesity, Alzheimer's, and diabetes; and improves both brain and body performance. He also offers practical advice on adopting an intermittent fasting eating pattern as well as information for parents and physicians.

Mark P. Mattson is currently Adjunct Professor of Neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University and was previously Chief of the Laboratory of Neurosciences at the National Institute on Aging in Baltimore. He is among the most highly cited neuroscientists in the world with more than 900 publications and 200,000 citations, is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and has received many awards including the Metropolitan Life Foundation Medical Research Award and the Alzheimer's Association Zenith Fellows Award. He is the author of The Intermittent Fasting Revolution: The Science of Optimizing Health and Enhancing Performance (MIT Press).

“An excellent book, full of very valuable information to improve health and longevity from one of the pioneers and leaders of the 'intermittent fasting revolution.'” Valter D. Longo, Director of the University of Southern California Longevity Institute; author of the international bestseller The Longevity Diet

“This timely book, which includes both historical antecedents as well as the very latest research, is an authoritative and yet accessible introduction to intermittent fasting. Mattson has done more than any other scientist to illuminate this critically important topic, and we are fortunate to have this succinct synopsis of decades of research.” Ken Ford, Founder and Director, Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition

Related Books

- Health Articles

- LIFE Fasting Tracker

- LIFE Extend

5 Human Fasting Studies with Dr. Mark Mattson

A large number of research studies have investigated the impacts of caloric restriction and intermittent fasting in many different species, from fruit flies to mice to monkeys . A quick Google Scholar search yields more than 8,000 results for scholarly articles on “ intermittent fasting ”.

Relatively few studies have evaluated the impacts of fasting in humans, in comparison to studies of impacts in animal models. These relatively few human studies, however, demonstrate that various intermittent fasting schedules have promising benefits for human health.

Dr. Mark Mattson , a neuroscientist at the National Institute on Aging and a professor of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University , studies the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie these benefits. He likens intermittent fasting to exercise; both are “good” stressors that prompt the body to ramp up stress-busting , self-cleanup and anti-inflammatory processes.

“If you don’t expose yourself to mild bioenergetic stress, whether it’s exercise or fasting intermittently, then it’s not so good for your cells, particularly as you age. You aren’t tapping all of the processes that help cells resist stress, function efficiently and fight disease,” Mattson said.

The analogy between exercise and fasting goes further, especially if you agree with Mattson’s view of fasting and subsequent refeeding as a “ metabolic switch ” that takes the body through a growth phase, a cleanup phase and back again. In this view of fasting, the refeeding phase is just as important as the fasting phase.

When you exercise, you put stress on your muscles and cardiovascular system in a way that prompts your body to produce more muscle cells and more mitochondria, which are the “power plants” inside of those cells. There are even some studies that suggest that proteins released from muscles during exercise, known as myokines ( myo = muscle, kine = signaling), act as signaling molecules in the brain. There they promote new synapse formation between nerve cells, or synaptic plasticity , and the formation of new nerve cells from stem cells in some regions of the brain.

“Synaptic plasticity is the brain’s ability to strengthen or weaken connections between pairs of functionally linked neurons. Neurons form functional circuits through specialized nodes called synapses. The synapse is where one neuron talks to another. Aged neurons in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex also have fewer synapses…” – Shelly Xuelai Fan, science writer and neuroscientist

But the muscle cell growth and brain health outcomes of exercise don’t happen during your workout – they actually occur when you rest and sleep after a day of physical activity.

“Your muscles aren’t getting bigger when you are lifting weight or exercising,” Mattson laughs. “It’s when you eat and sleep.”

The same appears to be true of intermittent fasting. Fasting puts cells, including muscle cells and likely also nerve cells, into a stress-resistance mode that benefits these cells when nutrients become available again.

“The stress period, whether it’s fasting or exercise, puts the cells in a stress-resistance mode; they don’t grow and they reduce their overall protein synthesis while enhancing their removal of damaged molecules and proteins through autophagy ,” Mattson said. “Then during the resting or refeeding period, once the cell has cleared out the garbage, protein synthesis goes up and new, undamaged proteins are created. We have evidence that this doesn’t just benefit muscle cells, but that in the brain, new synapses may be formed between nerve cells, probably during the resting and refeeding period. These wouldn’t have formed if the individual hadn’t been subjected to the stress in the first place, whether through fasting or exercise.”

Of course, most of the studies that have revealed the positive impacts of fasting on autophagy , inflammation ( 2 ), synapse formation and other mechanisms underlying chronic disease have been done in animal models, not humans. We certainly need more human studies, particularly investigating the impacts of fasting in specific human populations and for specific disease states, in order for physicians to begin to prescribe fasting interventions with any kind of precision.

But what DO we know today about the impacts of intermittent fasting in humans. What do we know that we can begin to apply?

We recently interviewed Dr. Mark Mattson, a veritable “giant” in the field of intermittent fasting research and its underlying mechanisms, to address this question. He has published a total of four controlled human studies that investigate the impacts of various intermittent fasting interventions. He is also currently conducting a fifth study to look for signs of the cognitive and neurological benefits of fasting. We summarize these five studies in this blog post.

A lot of the initial research on intermittent fasting in humans has been observational, based on results observed in people fasting for Ramadan and in bodybuilders, for example.

“Bodybuilders don’t just want build muscles, but they want them to show. You need two things for that – big muscles and not much fat,” Mattson said. “It turns out that a lot of bodybuilders, perhaps by trial and error, have found that if they don’t eat breakfast, work out midday or around 16 hours fasted, and then eat in the ensuing time, they are able to maintain and build muscle while losing more fat. There have actually been some studies showing this – you can maintain and build muscle while on an intermittent fasting regimen.”

This small scale human study also showed that regular overnight fasting may reduce inflammation and contribute to muscle repair after exercise.

Observational studies of Ramadan fasting have also generally shown that fasting may have weight loss and metabolic health benefits. Ramadan fasting typically involves avoiding calories from sunrise to sunset. Studies of Ramadan fasting almost always involve observation rather than controlled experiments, meaning that they can’t tell us if fasting caused the observed health benefits. However, Ramadan fasting has been shown to positively impact body weight and body fat, at least during the month of Ramadan, as well as levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) and blood pressure .

“[Our] results indicate that Ramadan fasting in young healthy individuals has a positive impact on the maintenance of glucose homeostasis. It also shows that adiponectin levels dropped along with significant loss in weight. We feel caloric restriction during the Ramadan fasting is in itself sufficient to improve insulin sensitivity in healthy individuals.” – Gnanou et al. 2015

Observational studies can give us a picture of what impacts fasting has in humans. However, randomized controlled trials are considered to be evidence of a higher standard and necessary to make health recommendations around something like fasting. People participating in a controlled cohort study or controlled trial are given strict guidelines to follow for a health intervention and typically report to a health provider setting in order for their outcomes (weight, blood pressure, blood biomarkers, etc.) to be measured. People participating in a randomized controlled trial are randomly (e.g. by the flip of a coin) assigned to either a group receiving a treatment or intervention of interest, or to a group receiving a placebo or a control treatment. In the best trials of new pharmaceutical drugs, for example, participants are “blinded” to the treatment group they are in – they don’t know if they are receiving the experimental drug or a placebo (e.g. a sugar pill).

For intermittent fasting, it’s difficult to have a “blinded” treatment or a placebo – you know whether you are fasting or not! However, controlled studies of intermittent fasting can compare intermittent fasting to a standard calorie-restricted diet “control”. The control treatment in this case is important in order for researchers to evaluate the benefits of fasting while “controlling” for the benefits that would come from any type of weight loss.

In terms of evidence based on controlled studies of intermittent fasting, we know more about the impacts of fasting in overweight, prediabetic and inflammation-prone individuals, as opposed to healthy individuals. Several controlled studies conducted by Mattson and others reveal that intermittent fasting can promote weight loss (usually to the same extent as standard dieting) and improve biomarkers of metabolic and cardiovascular health for overweight individuals.

“What we can say for sure is that overweight humans who can switch their eating pattern to intermittent fasting and stick with it are going to maintain a lower body weight with lower ‘bad’ fat stores and better glucose regulation,” Mattson said.

Study 1: Intermittent Fasting in Asthma Patients

“Asthma subjects lose weight and exhibit improved mood and peak airflow when maintained on an alternate day calorie restriction diet.” – Johnson et al. 2006

Mattson’s first study of intermittent fasting in humans was a cohort study and investigation into the impacts of fasting in asthma patients. In a study published in 2006, 10 obese individuals (with a BMI over 30) with moderate to severe asthma maintained an alternate day intermittent fasting schedule for 8 weeks. On this dietary regime, they ate what they wanted when they wanted it every other day, while eating less than 20% of their normal calorie intake (partly in the form of a low-carb meal replacement shake) on their fasting days. This was equivalent to less than 500 calories on alternate fasting days.

The researchers measured baseline values on factors including hunger, weight, mood, asthma symptoms, airway resistance and blood markers of inflammation for all of the individuals in the study. The participants then started their alternate day fasting intervention, which lasted two months. The researchers re-evaluated the participants’ hunger, weight, mood, asthma symptoms, airway resistance and various blood markers approximately every two weeks.

The impacts of this study of intermittent fasting were quite significantly positive and have set the stage for many follow-up studies on how fasting can improve markers of inflammation.

The obese asthma patients in this study lost an average of 8% of their body weight during the course of the study. Their ketone levels also increased on fasting days, confirming that they were adhering to their alternate day fasting regimen.

The study participants reported that their mood and energy levels improved throughout the study, with most of these improvements happening over the first three weeks of the regimen and staying elevated thereafter. Their hunger sensation levels on fasting days stayed about the same throughout the study.

The results of the study get exciting when it comes to asthma symptoms and the markers of inflammation and oxidative stress that Mattson’s lab evaluated in the patients’ blood samples.

“Not immediately, but between two and four weeks of having been on the intermittent fasting regimen, the participants’ asthma symptoms and airway resistance improved and their markers of inflammation and oxidative stress went down. This improvement even persisted for up to two months following the intervention,” Mattson said.

“The improved clinical findings were associated with decreased levels of serum cholesterol and triglycerides, striking reductions in markers of oxidative stress (8-isoprostane, nitrotyrosine, protein carbonyls, and 4-hydroxynonenal adducts) and increased levels of the antioxidant uric acid. Indicators of inflammation, including serum tumor necrosis factor-α and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, were also significantly decreased by [alternate day fasting].” – Johnson et al. 2006

Impressively, the asthma patients who had practiced intermittent fasting for two months showed similar improvements in their asthma symptoms and pulmonary function as patients newly started on controller medications for asthma including a medication called singular (which the author of this blog post personally takes for asthma). Pulmonary function was measured as peak expiratory flow, known commonly as the breathing test measurement if you’ve even been tested for asthma.

“Levels of […] markers of inflammation and oxidative stress were decreased on both ad libitum and CR days, indicating a sustained effect of the [alternate day fasting] diet that did not fluctuate in response to the level of energy intake on the day prior to blood sampling.” – Johnson et al. 2006

Studies 2 and 3: The 5:2 Diet in Obese Individuals

While the study of intermittent fasting impacts on asthma patients described above was promising, it only evaluated impacts in a very small group of patients. Subsequent studies that Mattson worked on tested the impacts of modified fasting for two days every week in larger samples of overweight women.

With first author Michelle Harvie, a research dietitian at the University Hospital South Manchester Trust and a breast cancer researcher associated with the University of Manchester , Mattson published two studies investigating the impacts of fasting in overweight women. These studies, published in 2010 and in 2013 , formed the basis of what is today known as the 5:2 diet . This intermittent fasting schedule involves partially fasting two days out of every week by consuming only one moderate-sized meal or under 500 calories on those two days.

The first study was a randomized controlled trial in 107 overweight or obese premenopausal women. These women were randomly assigned to follow either a 5:2 intermittent fasting schedule (75% calorie restriction on fasting days) or a continuous calorie restriction diet (25% calorie restriction every day) for six months. In both groups, the participants could eat foods that included carbohydrates, but were instructed to follow a Mediterranean-type diet. On fasting days in the 5:2 diet group, the women essentially ate around two pints of semi skimmed milk, four servings of vegetables (~80 g/serving), a serving of fruit, a salty low calorie drink and a multivitamin and mineral supplement.

All participants were asked to keep 7-day food diaries so that the researchers could track their adherence to their fasting schedules or diets. They were encouraged to use techniques such as self-monitoring, obtaining peer and family support and avoiding tempting environments in order to maintain their diets. (Our LIFE Fasting Tracker app can help with these techniques!)

About 80% of women who started the study, finished it, with most dropouts occurring in the first three weeks.

“This told us that for people who have always eaten three meals plus snacks, shifting to eating only 500 calories on a fasting day may make them feel very hungry, irritable and unable to concentrate,” Mattson said. “But if they can stick with it for close to a month, those initial side effects often completely disappear as they become adapted.”

The researchers measured the participants’ weight and biomarkers for breast cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and dementia risk, at baseline and after one, three and six months on the 5:2 diet. They found that women who practiced the 5:2 diet lost about the same amount of weight as women who counted and restricted their calories on a daily basis .

The intermittent fasters however had slightly greater reductions in insulin levels, while all of the women experienced comparable reductions in leptin (a hormone that regulates appetite and fat storage), free androgen index (a biomarker for breast cancer risk), high sensitivity C-reactive protein (associated with inflammation), total and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides and blood pressure. The menstrual cycle was also longer in women who were practicing a 5:2 diet.

“[T]he greater average cycle length amongst the [intermittent fasting] women may reduce breast cancer risk and reflect increased follicular length.” – Harvie et al. 2010

In a follow-up study and randomized trial with a similar protocol, even greater impacts were observed for women who followed, for four months, a 5:2 diet that restricted not just calories on fasting days, but also carbohydrates. In this case, the participants who fasted consumed less than 40 grams of carbohydrates on fasting days, with relatively higher consumption of protein and fat. On fasting days the women essentially ate 250 grams of protein foods including lean meat, fish, eggs and tofu, along with three servings of low-fat dairy foods, four servings of low-carbohydrate vegetables and one serving of low-carbohydrate fruit. Protein intake, in particular, helped minimize hunger on fasting days.

Participants were women who had a family history of breast cancer. The researchers found that for these women, the 5:2 diet with carbohydrate restriction was superior to a continuous calorie restricted Mediterranean-type diet in terms of promoting greater body fat loss and improved insulin sensitivity .

“The take-home of these two studies is that women on the 5:2 diet had improved glucose regulation and lost more abdominal fat than women who counted calories for every meal of every day,” Mattson said. “This is because on the days they were eating only 500 calories, they depleted all of the energy in their liver and started using fats. By comparison, with a continuous calorie restriction diet, even if you have a reduced calorie intake at every meal, you are still replenishing your liver energy stores every time you eat.”

It’s intriguing to look at adherence to the 5:2 diet versus the continuous calorie restriction diet in these studies. By three months into their diets, the intermittent fasters in the second study were still adhering to their calorie and low carbohydrate goals on 70% of their designated fasting days. On the other hand, people following the continuous calorie restriction diet were only hitting their calorie goals approximately every one out of three days (39% of days).

“Although weight control is beneficial, the problem of poor compliance in weight loss programmes is well known ( 9 ). Even where reduced weights are maintained, many of the benefits achieved during weight loss, including improvements in insulin sensitivity, may be attenuated due to non-compliance or adaptation ( 10 ). Sustainable and effective energy restriction strategies are thus required. One possible approach may be intermittent energy restriction (IER), with short spells of severe restriction between longer periods of habitual energy intake. For some subjects such an approach may be easier to follow than a daily or continuous energy restriction (CER) and may overcome adaption to the weight reduced state by repeated rapid improvements in metabolic control with each spell of energy restriction ( 11 ).” – Harvie et al. 2010

What do you find easier? Restrictive diets or intermittent fasting?

Study 4: Intermittent Fasting for Multiple Sclerosis

More recently, Mattson helped to conduct a study in collaboration with Drs. Kate Fitzgerals and Ellen Mowry, neurologists at Johns Hopkins, to evaluate the safety and feasibility of intermittent fasting interventions in 36 patients with multiple sclerosis . Mattson helped design the study.

The researchers again used a 5:2 diet protocol, with 75% calorie restriction or energy need reduction on two fasting days per week. They compared this to a continuous calorie restriction diet and a stable diet. The researchers did not observe any adverse events for the patients during the study.

All of the patients on either the 5:2 diet or the continuous calorie restriction diet lost weight, but the weight loss wasn’t significantly different between these groups. These patients did however, over the course of 8 weeks, report significant improvements in emotional well-being and depression when compared to patients on a stable diet (the control group).

Based on this study, Mattson and colleagues are seeking funding to conduct a larger and longer term study of intermittent fasting on symptoms and health in patients with multiple sclerosis.

Drs. Mowry and Fitzgerald are also currently performing a trial of daily time-restricted feeding in multiple sclerosis patients.

Study 5: Moving Forward with Brain Health

We need more studies of intermittent fasting in humans, particularly to demonstrate the touted cognitive function and brain health benefits of fasting. Mattson is working as we speak to address this gap, in collaboration with Dr. Dimitrios Kapogiannis , a neurologist in Mattson’s group at the National Institute on Aging.

“There’s quite a bit of evidence that, as with your other organ systems, long-term chronic obesity bodes poorly for your brain health as you age,” Mattson said. The idea is that intermittent fasting could help people achieve weight loss as well as reduce inflammation levels in their brains in a way that would help delay and even prevent neurodegenerative disease.

“A major ecological factor that drove the evolution of cognition, namely food scarcity, has been largely eliminated from the day-to-day experiences of modern-day humans and domesticated animals. Continuous availability and consumption of energy-rich food in relatively sedentary modern-day humans negatively impacts the lifetime cognitive trajectories of parents and their children.” – Mattson, 2019

Mattson and Kapogiannis have recruited 40 individuals who are at risk of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease because of their age (they range from 55 to 70 years old) and their metabolic status (they are obese and insulin resistant) to participate in this new study. These individuals will be randomly assigned to either a 5:2 diet or a health intervention that involves simply advice for healthy eating and lifestyle.

At baseline and at two months into the fasting intervention, the researchers will collect brain health data via a battery of psychological tests of cognition as well as via functional MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). Functional MRI can create a map of brain activity by measuring changes associated with blood flow. This imaging and other data the researchers will collect will reveal whether intermittent fasting can impact nerve cell network activity and improve learning and memory in the aging brain!

Mattson will also help analyze cerebral spinal fluid from the intermittent fasting individuals, obtained via spinal taps, to look for changes in the levels of a brain cell growth regulator called BDNF. Mattson has shown in his research that the neurochemical BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, increases in the brains of mice and rats when they are put on intermittent fasting regimens. Increased BDNF is thought to be responsible for some of the mental clarity and improved cognitive function associated with intermittent fasting in humans .

“From the cognitive health standpoint, our data is looking really good so far,” Mattson said.

We will be excited to hear about the results!

In Summary:

- Human studies of fasting have focused on impacts in overweight, prediabetic and inflammation-prone individuals.

- Alternate-day fasting (<500 calories every other day) reduces markers of inflammation. That can mean fewer asthma symptoms, less brain fog and reduced body pains!

- 5:2 fasting (a moderate-sized meal or <500 calories two days per week) promotes weight loss, lowered markers of breast cancer risk and better blood sugar control in overweight women.

- Fasting may improve mood, reduce symptoms of depression and improve cognition.

Take-home message: Intermittent fasting, whether a 5:2 diet or daily time-restricted feeding, are likely better for your health than eating three meals per day plus snacks. Especially if you love those carbs!

What questions do you hope to see answered or what data would you like to see from future studies of intermittent fasting interventions in humans? Let us know by commenting below!

Related Posts

Paige Jarreau, PhD

I am a health literacy advisor at LifeOmic and a science communicator at Kelly Services and the National Institutes of Health.

Add comment Cancel reply

Privacy preference center, privacy preferences.

Stories by Mark P. Mattson

Mark P. Mattson is chief of the Laboratory of Neurosciences at the National Institute on Aging and a professor of neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. His discoveries have advanced understanding of nerve cell circuits during aging.

Toxic Chemicals in Fruits and Vegetables Are What Give Them Their Health Benefits

Chemicals that plants make to ward off pests stimulate nerve cells in ways that may protect the brain against diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's

Mark P. Mattson

Enter a Search Term

Biohacking brain health: research exploring fasting and diet changes shows promise in delaying alzheimer's disease, improving cognition.

- Expert Advice

Scientifically reviewed by Sharyn Rossi, PhD , BrightFocus Foundation

Researchers, including BrightFocus grantees, have been examining how modifiable lifestyle interventions such as intermittent fasting, the “fasting-mimicking” diet (FMD), ketone supplementation, and other targeted diet changes can help people delay Alzheimer’s disease, improve cognition, and live longer.

Although fasting—or time-restricted eating within a certain window—has long been explored as a quick weight-loss tool, research into the many other health benefits of fasting techniques has been ongoing for decades. Recent findings on time-restricted eating methods, nutritional changes, and other interventions have shown positive and promising results in animal studies and limited human studies related to Alzheimer’s disease and cognition, although more controlled, randomized human trials are still needed.

But how do these “biohacks” really work? What does the research show, and who could benefit?

How fasting and the ketone factor combat aging

Fasting causes the coordinated alteration of numerous metabolic and transcriptional mechanisms that can influence cells throughout the body, producing an altered metabolic state that optimizes cellular functioning by removing or repairing molecules. This increases resilience to stress, reduces blood glucose, and decreases inflammation—culminating in maintained or enhanced cognitive performance.

A central aspect of fasting–which is different from just restricting calories–is that the body undergoes a metabolic switch from using glucose to using ketones as fuel, entering a fat-burning state called ketosis, a result of the depletion of liver energy stores and the mobilization of fat.

The metabolic changes that occur during repeated cycling from fasting to eating may help to support brain function and resistance to stress and disease.

Ketones trigger the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a molecule that promotes the growth of new brain cells and protects cells from stress, allowing them to live longer and strengthen neurons and neural connections in areas of the brain responsible for learning and memory.

According to neuroscientist and brain aging expert Mark Mattson, PhD, National Institute of Aging (as published in an interview ), scientists have discovered that fasting increases ketone levels more than the standard ketogenic, or low-carb “keto” diet. Ketogenic diets can increase ketones fourfold whereas fasting has been shown to increase ketones by up to twentyfold. As a result, fasting, compared to a ketogenic diet, may have a stronger, more beneficial effect on overall health and aging.

An active Alzheimer’s Disease Research project at BrightFocus is also investigating how brains use ketones as fuel against Alzheimer’s. Researchers are developing new imaging probes to visualize how the brain utilizes ketones as an alternate energy source and comparing these signatures to brain glucose metabolism. Highly anticipated results will provide new insights into potential treatment pathways and are expected to be published in the coming months.

It is important to note that mainstream ketogenic diets have been associated with adverse effects such as gastrointestinal problems, weight loss (which often should be avoided in neurodegenerative diseases), high cholesterol, and vitamin and mineral deficiencies. And while no major nutritional modification plan should be undertaken without consulting a doctor, researchers have also found exogenous ketone supplementation with ketone bodies, or ketone-infused drinks, to have similar results to intermittent fasting in some studies .

Further, genetic risk factors may also play a role in the efficacy of these lifestyle interventions, as is also currently being investigated by an Alzheimer's Disease Research project at BrightFocus.

Eat to live longer

Valter Longo, PhD, author of The Longevity Diet: Discover the New Science Behind Stem Cell Activation and Regeneration to Slow Aging, Fight Disease, and Optimize Weight and a professor of gerontology and biological sciences at the University of Southern California and director of its Longevity Institute, advocates for the practice of a healthy lifestyle that includes dietary and lifestyle interventions such as the longevity diet to promote healthy aging, live longer, and delay Alzheimer’s disease progression. In 2018, TIME Magazine named Dr. Longo as one of the 50 most influential people in health care for his research on fasting-mimicking diets as a way to improve health and prevent disease. Based on two decades of clinical studies and epidemiological research, including research into populations that get less Alzheimer’s diagnoses, such as centenarian-abundant longevity hotspots Okinawa, Japan, and Loma Linda, California, Dr. Longo described the plant-heavy longevity diet as “more of a food-based drug that has most of the benefits of a vegan diet without the problems of a vegan diet,” such as malnourishment and increased stress fractures.

The longevity diet is nearly free of the saturated and trans fats found in high quantities in animal-derived foods, which have been associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in studies conducted at the Chicago Health and Aging project. Processed foods have also been linked to an increased risk of dementia.

Components central to the higher-complex carb, lower-protein longevity diet include:

- two meals a day and one snack

- foods rich in omega-3s

- vitamins B, C, D, and E

- whole grains

- some fish (with low mercury levels)

- limited sugar

- coffee - olive oil (3 tablespoons per day) and nuts (1 ounce per day)

- avoid all animal-based products except for low-mercury fish and cheese or other dairy products from goat’s milk

- 12 hours of eating and 12 hours of not eating, or “fasting,” per day

- Exercise: walk for an hour every day and as much as possible (take the stairs if you can); incorporate 2.5 hours a week of moderate to vigorous exercise, including strength training and free weights

In a study published earlier this year in the journal Cell , Dr. Longo and coauthor Rozalyn Anderson of the University of Wisconsin said that maintaining a BMI lower than 25, along with ideal sex- and age-specific body fat and lean body mass levels and abdominal circumference, should be used as guidelines to establish daily food intake rather than a set calorie level. In younger and middle-aged adults, a high BMI is associated with reduced cognition or a higher risk of dementia later in life.

Evidence is also growing to support the notion that intermittent fasting can have health benefits associated with cardiovascular disease, mood, and diabetes—a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease—among others. Those who have diabetes can only fast under strict health and medication monitoring as it is not a practice that is suitable for every individual and may also be harmful if you need food at certain times or take medication that affects your blood.

The “fasting-mimicking” diet

In a recent study in Cell Reports , investigators including Dr. Longo discovered that cycles of a diet that mimics fasting appear to reduce signs of Alzheimer's in mice.

The “fasting-mimicking” diet, which is also a pillar of the longevity diet, is designed to mimic the effects of a water-only fast while still providing necessary nutrients. In mice, researchers found reduced brain inflammation and increased cognitive performance in addition to lower levels of two disease makers: amyloid beta—the primary component of plaque buildup in the brain—and hyperphosphorylated tau protein, which forms tangles in the brain.

Early clinical data indicates that five days a month of the FMD are safe and feasible for the group of patients with mild impairment or early Alzheimer's disease who were also studied; however, Dr. Longo stated that further human studies are still needed and that individuals should not undertake this regimen without close supervision by medical professionals. Notably, the clinical trial also provided patients with daily supplements of plant-based fats to promote a more ketogenic state.

So, should everyone just start fasting?

It’s not that simple. Every person is different, and only a doctor or qualified medical professional should provide guidance on what is appropriate.

People who need to take certain medications that require food or who take heart or blood pressure medications may be more likely to suffer dangerous imbalances in potassium and sodium when they're fasting. Those who have a history of disordered eating are not advised to try intermittent fasting, which can also bring about a host of side effects, including fatigue, insomnia, nausea, and dizziness.

In a review of the research by the National Institute of Aging published in the New England Journal of Medicine , authors Rafael de Cabo, PhD, of NIA’s Intramural Research Program (IRP) , and Mark Mattson, PhD, stated that while the benefits of fasting are evident, human trials have mainly involved relatively short-term interventions and have not provided evidence of long-term health effects, including effects on lifespan, and that studies are needed to determine whether this eating pattern is safe for people at a healthy weight, or who are younger or older, since most clinical research so far has been conducted on overweight and middle-aged adults. In addition, research is needed to identify safe, effective medications that mimic the effects of intermittent fasting without the need to substantially change eating habits.

The bottom line

Ultimately, “biohacks” like fasting or time-restricted eating are just words that have limited value; one size does not fit all. What is more important is what type of fasting or time-restricted eating method is best for an individual, if any, and additional Alzheimer’s disease research is still needed in humans.

The good news?