- Get involved

COVID-19: A reminder of the power of hope and solidarity

May 5, 2020.

Ulrika Modéer

UN Assistant Secretary-General and Director of the Bureau of External Relations and Advocacy, UNDP

Co-Founder, Heart17

The novel coronavirus pandemic can be the moment the world pushes back against fear and isolationism, and turns instead towards hope, solidarity and a shared sense of global community.

These are fearful times, to be sure. Some 3.55 million people have been infected by COVID-19 and nearly a quarter of a million have perished. Billions of people are on lockdown or in self isolation.

Yet this pandemic and the fear, dread, and anxiety that it has induced has not occurred in isolation. For years, we have existed under the constant and pervasive feeling that things are getting worse, that we are failing each other and that we are failing our planet. This isn’t helped by a daily news cycle that reads like an ever-escalating drumbeat of anxiety. Climate change, war and conflict, isolationism and trade wars; our world, at times, feels dark and lonely, and this despite the many, many positive news stories that exist but that rarely get attention.

Global togetherness

No one doubts that COVID-19 is one of the most dire threats the world has ever faced. And yet, amidst the confusion and anxiety, there are ever stronger signs of hope and solidarity, a sense of, and desire for, togetherness.

It is this spirit of global togetherness that gives us hope. In this time of crisis, we are all neighbours in the world, and success will only be achieved when all people, in all countries, are protected.

Thankfully, this shared sense of responsibility has seen a world come together in ways that we have not seen for some time, and the examples are everywhere.

In the U.K., an army of volunteers has come forth to support their neighbors. As stated in the New York Times , “When the government appealed recently for 250,000 people to help the National Health Service, more than 750,000 signed up. It was forced to temporarily stop taking applicants so it could process the flood.”

In Somalia, where health infrastructure and traditional media have suffered under decades of strife, local storytellers are being equipped with the skills and tools to reach remote communities and educate them on best practices against COVID-19. The initiative is a collaboration between UNDP Somalia ’s Accelerator Lab and experts from Australia’s Queensland University and Digital Storytellers .

And, as pointed out by Jayathma Wickramanayake, the UN Youth Envoy, young people from Syria to Peru to South Sudan are helping to tackle misinformation, raise community awareness and support the elderly.

Such examples are spreading like wildfire as people seek out a light at the end of the tunnel and work to show, to each other, that we all stand together. We see this in the towns and cities around the globe where citizens are painting hearts on windows, where crowds cheer for healthcare workers, and where everyday people perform songs on social media to help lift spirits.

Leaning into hope

Without ignoring the realities we face, it is clear that the world is reaching for a positive message. These words were echoed by UN Secretary-General António Guterres to world leaders, as he emphasized the need for solidarity and global cooperation .

His call has resonated. Long sought-after partnerships with private sector companies are suddenly coming to fruition as everyone steps up to pitch in. UNDP has recently partnered with Variety on a global ad campaign. And UNDP’s new partnership with Heart17, a global initiative using creativity and innovation to accelerate the SDGs and light a spark of hope among the young generation, has brought together major players within fashion and popular culture, such as H&M Group and Spotify, to share their media space for messages around health and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Certainly there will be many lessons learned once COVID-19 has passed, and UNDP’s Accelerator Labs has assessed some of the post-COVID-19 trends they see emerging. A key takeaway is this: COVID-19 has been a sort of reset across societies, across sectors. From telecommuting for work or school, to supply chain management, to support for health systems, and small and medium enterprises, to mental health support across borders or simply across the street, COVID-19 has forced us to look at how we work as a species on this planet.

Amidst the pain that we continue to endure, we should find comfort in the stories of hope and solidarity, and continue to see the value in the positive, encouraging lessons that are emerging for our post-COVID world.

Related Content

Revitalizing global development: The urgent call for quality funding

Billions of dollars can be freed up to protect vulnerable populations from economic hardship and advance the SDGs

Achieving healthy societies depends on transformative change

COVID-19 has laid bare the weaknesses of our health systems and the shortcomings of our development approaches.

What Ukraine shows us about working together

UNDP and Samsung fighting COVID-19

Successful partnership marks first anniversary.

Global solidarity in the face of COVID-19

The coronavirus pandemic has upended almost every aspect of life as we know it.

Holding on to hope is hard, even with the pandemic’s end in sight – wisdom from poets through the ages

Professor of English, Rutgers University - Newark

Disclosure statement

Rachel Hadas does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Rutgers University - Newark provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

As we begin to glimpse what might be the beginning of the end of the pandemic, what does hope mean? It’s hard not to sense the presence of hope, but how do we think of it?

Hope is fragile but tough, fugitive but tenacious, even adhesive. It sticks: Hope “ stayed behind/in her impregnable home beneath the lip/of the jar ,” wrote the ancient Greek poet Hesiod in his poem “Works and Days.” While the evils released from the jar by Pandora fly out into the world, hope remains.

Written in the 19th century, poet Emily Dickinson’s version of hope is “the thing with feathers” that “perches in the soul” and perseveres; it sings “and never stops at all.” Dickinson invites us to imagine Hope frail as a bird, fluttering. It doesn’t fly away – but that verb “perches,” suggesting that it always might.

That Dickinson’s hope “sings the tune without the words” might suggest that hope provides a general, even generic response rather than a specific remedy tailored to the occasion. Nevertheless, even in the sorest storms, hope is available.

Which isn’t to say that hope is always consoling. When we turn to hope, have recourse to hope or even hope against hope, it isn’t at moments of triumph or complacency. Rather, we need hope at moments when things feel precarious.

Once we recognize this simple principle, the intuitive truth that hope is a companion of anxiety turns up everywhere.

‘Intrinsically intertwined’

In 2018, the Rubin Museum in New York City mounted a participatory art installation entitled “ A Monument for the Anxious and Hopeful .” Artist Candy Chang and writer James A. Reeves asked “ visitors to anonymously write their anxieties and hopes on vellum cards and display them on a 30’ x 15’ wall for others to see .”

Tracy A. Dennis-Tiwary , a psychology and neuroscience scholar, notes that over 50,000 cards were submitted . The cards, writes Dennis-Tiwary, “reflected … immense optimism and fear. … It was not obvious unless you looked closely, but the juxtaposition of the two card types revealed a pattern: the anxieties and hopes were often the same. … The monument showed how anxiety and hope go hand in hand.”

Chang and Reeves write that “Anxiety and hope are defined by a moment that has yet to arrive.” Put another way, writes Dennis-Tiwary, “when we imagine and prepare for the uncertain future, anxiety and hope are intrinsically intertwined, forever transforming from one to another.”

Leaving despair behind

The Athenian dramatist Euripides was a peerless psychologist with a particular interest in the stresses of decision-making. His play, “ Iphigenia among the Taurians ,” is less a tragedy than a melodrama or romance, with a happy ending against the odds.

In the following passage, the resourceful Iphigenia – a priestess whose job it is to sacrifice foreigners who land on the shores of her captor’s island – is devising a complicated strategy to free at least one of her prisoners and thereby send a message to her family back home. She’s unaware, at this point in the drama, that one of the captives whom she’s supposed to sacrifice is her own brother Orestes. She has thought of a clever scheme, but the hope engendered by it, the very possibility of its success, also makes her anxious. Here’s my translation:

“People in trouble do not have a prayer of calm once they have left behind despair and turned toward hope.”

As with the plot of any exciting movie, we’re rooting for the good guys, and our hope is balanced by uneasiness. Suspense!

Iphigenia’s next words to Orestes are also acute:

“So this is what I fear: that you, once you have sailed away from here, will forget about me, will ignore my heart’s desire.”

Will the lucky winners, the survivors, forget about those who, having perhaps enabled them to escape, have been left behind?

This is Iphigenia’s entirely reasonable worry. Even the hoped-for and possible success of her scheme may have a downside. As Chang, Reeves and Dennis-Tiwary all point out, hope and anxiety are so closely intertwined that they may turn out to be different sides of the same coin.

‘Green shoots of hope’

Only two months after the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, and less than two months after President Joe Biden’s inauguration, hope is palpable; so is anxiety.

A year into the pandemic, spring is about to arrive. A recent New Yorker article notes that “ here in the city there are green shoots … who can’t imagine that happier days may soon be here again ?” The word hope isn’t mentioned, but a hopeful aura pervades the passage.

Yet nothing is certain. Trump and Trumpism glower in the wings and also in the political arena. New viral variants abound. There may be a light at the end of the tunnel, no doubt – but how long will that tunnel be? Hope requires patience.

In a famous passage in Plato’s “Republic ,” Socrates evokes the limitations of human vision by using the allegory of an underground cave whose inhabitants have never seen the daylight. The passage never mentions hope, but it does mention the reluctance of the prisoners, whose lives have been spent underground, to be dragged into the light, which dazzles their eyes.

Hope doesn’t go away, but it morphs and mutates. Have we become habituated to despair?

[ Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter .]

- Donald Trump

- Emily Dickinson

- January 6 US Capitol attack

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Perspective and Hope in the Era of COVID-19

Close your eyes and think of someone you're protecting and someone you'll hug when the pandemic is over

Duke Global Health Institute psychologist Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell explores behaviors, hope and connectedness in her video.

By Mary Brophy Marcus

Published April 17, 2020, last updated on August 4, 2020 under Voices of DGHI

Seeking to find and share hope during a difficult time, DGHI psychologist Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell recently made a video to share with others who are staying at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Watch her video and read a few of her insights in her Q&A.

Why did you make a video?

As the far-reaching effects of COVID-19 became apparent, I began to hunger for hope. Where does hope come from? How do we stay hopeful? As a researcher who studies positive mental health, I knew hope had been studied, and I wanted to apply that knowledge to our current situation, for myself as much as anyone else.

What's a key message you really want people to know?

Staying home during COVID-19 is a significant and brave action. It's not inaction.

Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell shares an...

What’s something you discovered along the way that surprised you?

That what we’re living through today is a human experience. I suddenly feel very connected to my ancestors. Viruses are ancient, and while this situation feels new and unknown to me, it actually isn’t new and it isn’t unknown. People have responded to epidemics for centuries.

Who should watch this video?

A lot of us are gathering over Zoom these days, often just for an unstructured check-in (Check out this example from Duke University ). I’d love it if people watched this video together. The four-minute hope exercise at the end is more powerful if done together. This video may provide a peaceful way to end a virtual check-in.

Is there anything that weighs on your mind that you didn’t have the chance to address in your video?

So many people are losing their jobs and I’m deeply worried about the impact of such financial stress. I suggest in this video that people stay strong and stay home, and yet we all have to earn money somehow. In addition to keeping perspective and hope, I think the public health community needs to address economics, too.

- Mental health

- United States

- Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell

Related News

Centering Maternal and Infant Health in the Workplace

May 2, 2024

Student Stories

Class of 2024 Spotlight: Ismail Shekibula MS’24

April 29, 2024

Research News

A Collective Effort to Improve Child Health in Nigeria

April 10, 2024

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Hope and resilience during a pandemic among three cultural groups in israel: the second wave of covid-19.

- 1 Conflict Management & Resolution Program, Department of Interdisciplinary Studies, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel

- 2 Department of Public Policy & Management, Guilford Glazer Faculty of Business and Management, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel

The aim of this study was to explore the coping resources of hope and sense of coherence, which are rooted in positive-psychology theory, as potential resilience factors that might reduce the emotional distress experienced by adults from three cultural groups in Israel during the chronic-stress situation of a pandemic. The three cultural groups examined were secular Jews, Ultra-Orthodox Jews, and Arabs. We compared these cultural groups during the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, just before the Jewish New Year (mid-September 2020) as a second lockdown was announced. Data were gathered from 248 secular Jews, 243 Ultra-Orthodox Jews, and 203 Arabs, who were 18–70 years old ( M = 37.14, SD = 12.62). The participants filled out self-reported questionnaires including the Brief Symptom Inventory as a measure of emotional/psychological distress (i.e., somatization, depression, and anxiety) and questionnaires about sense of coherence and different types of hope (i.e., intrapersonal, interpersonal, and transpersonal) as measures of coping resources and resiliency. Differences were found between the three groups in terms of several variables. The Arab participants reported the highest levels of emotional distress and the lowest levels of interpersonal and transpersonal hope; whereas the Ultra-Orthodox participants revealed the highest levels of sense of coherence and other resilience factors. A structural equation model revealed that, in addition to the sociodemographic factors, only sense of coherence and intrapersonal hope played significant roles in explaining emotional distress, explaining 60% of the reported distress among secular Jews, 41% among Ultra-Orthodox Jews, and 48% among Arabs. We discuss our findings in light of the salutogenic and hope theories. We will also discuss their relevancy to meaning-seeking and self-transcendence theory in the three cultural groups.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has led governments of many countries around the world to impose lockdowns that have lasted several weeks to several months. In Israel, the first lockdown lasted from March to May 2020. Once Israel got out of the first lockdown, the feeling among citizens was that normal life had returned. Requests from the government to minimize gatherings were not enforced and schools were opened, with students in isolated groups (capsules), at the beginning of September. Thus, by mid-September, a second wave had arrived and, just before the Jewish New Year, the government announced a second lockdown, with restrictions that were more severe than those imposed during the first wave of the epidemic.

Against the backdrop of the second wave and the second lockdown, the present study aimed to assess two main resources, hope and sense of coherence (SOC), as potential resiliency factors capable of reducing three common emotional problems (i.e., somatization, anxiety, and depression) during this difficult period. Based on the hope theory of Snyder (2000) and salutogenic theory ( Antonovsky, 1987 ), which are inherently related to the concepts of meaning-seeking and self-transcendence, we wanted to examine the above-mentioned resiliency factors and emotional-distress variables among three main cultural groups in Israel: secular Jews, Ultra-Orthodox Jews, and Arabs. We sought to explore similarities and differences among these groups, in terms of the different variables as well as the ways in which resiliency factors explain emotional distress under the conditions of chronic stress imposed by an ongoing epidemic.

Hope for the future enables effective coping with developmental challenges. It elaborates options for individuals and helps them to examine sources of personal strength by relating to the future and not only relying on the past ( Sharabi et al., 2012 ). Several researchers have tried to define hope and have emphasized different components of this construct. Snyder (2002) offered a definition in which hope combines individual perceptions, in order to generate alternative ways to achieve desirable goals. Others have suggested that hope is a personal resource that can be developed and fostered and which is essential for coping, success, and decision-making.

Researchers have agreed that hope involves emotional elements of expectation, as well as cognitive and deductive thinking to pursue new ideas and solutions ( Lazarus, 1991 ; Snyder, 1994 ). Hope is seen by some researchers as a positive attitude toward life and the ability to have optimistic views ( Moorey and Greer, 1989 ; Strang and Strang, 2001 ; Sawatzky et al., 2009 ). Hope is based on high-level cognitive processing, which requires mental representations of positively valued, abstract future situations. More specifically, it requires setting goals, planning how to achieve those goals, and the use of imagery and creativity, cognitive flexibility, mental exploration of novel situations, and even risk-taking ( Lazarus, 1991 ; Snyder, 1994 , 2000 ). The affective component of hope is considered to be a consequence of cognitive elements and may contain positive, as well as negative features since individuals may realize that the achievement of their goal may involve struggles, costs, and endurance ( Snyder, 1994 , 2000 ). It seems that the emotional element of hope is rooted in early experiences of trust, which are influenced by others and by external events ( Erikson et al., 1994 ).

While Snyder (1994 , 2000) emphasized the cognitive component of hope, Jacoby and Goldzweig (2014) elaborated on Snyder's concept of hope and identified three sub-concepts that emphasize the emotional components of hope, in addition to the cognitive component. In their view, the term intrapersonal hope refers to hope in which a person looks into him/herself while assessing his/her resources. Interpersonal hope refers to the relationships one has with different significant and meaningful individuals in whom one can trust. Transpersonal hope refers to hope that relies on supernatural powers and which gives an individual a sense of meaning and purpose ( Jacoby and Goldzweig, 2014 ). The representation of hope in this way is connected to the concept of self-transcendence, which also represents consciousness that is related to various sources from one's internal self to one's environment and broadening to include the cosmos ( Wong, 2016 ).

In the current study, we evaluated the three components of hope as resiliency factors that might be involved in reducing psychological/emotional distress. Indeed, one recent study has shown that hope, defined as expectation from the future, leads to positive outcomes even during a pandemic, meaning that a sense of leading a meaningful life mediates the role of basic health in predicting stress resulting from Covid-19 ( Trzebiński et al., 2020 ; Walsh, 2020 ; Yildirim and Arslan, 2020 ).

Salutogenesis and Sense of Coherence

Antonovsky (1979) proposed the conceptualization and model of salutogenesis , which means the “origin of health,” in the stress and health field. Rather than classifying health/illness dichotomously, this continuum model suggests that each individual is somewhere on the ease/dis-ease continuum at any given moment ( Antonovsky, 1987 ). According to this model, people have general resistance resources that can help them to conceptualize the world as organized and understandable. SOC represents the motivation and the internal and external resources one can use to cope with stressors and plays an important role in the way one perceives challenges throughout life. SOC is a global orientation to see the world as more or less comprehensible (the internal and the external world are perceived as rational, understandable, consistent, and expected), manageable (the individual believes that s/he has the necessary resources available to deal with situations), and meaningful (the motivation to cope and the commitment to emotionally invest in the coping process; Antonovsky, 1987 ). Both the cognitive aspects of SOC and the emotional-motivational aspects reflect major components of the concept of self-transcendence. In the self-transcendence process, it is claimed that cognitive restructuring processes lead to choices and outcomes ( Wong, 2016 ), which can also be viewed as indicative of comprehensibility and manageability. Additionally, an inherent tendency to move beyond one's own self-interest and become aware of sources of purpose ( Wong, 2016 ) can be viewed in light of the salutogenic concept of meaningfulness.

The salutogenic model suggests that an individual with a strong SOC is less likely than one with a weak SOC to perceive many stressful situations as threatening and, therefore, anxiety-provoking. Given their tendency to perceive the world as meaningful and manageable, individuals with a strong SOC will be less likely to feel threatened by stressful events, including a pandemic, and, therefore, will be less vulnerable to developing psychological distress in such a situation ( Gómez-Salgado et al., 2020 ; Ruiz-Frutos et al., 2020 ; Schäfer et al., 2020 ).

Research in the stress literature dealing with the concept of SOC and its application to mental-health problems has differentiated between acute stress and chronic stress. It has been argued that the resource of SOC is more influential and plays a powerful role in reducing stress in the context of chronic stress, as opposed to acute stress ( Sagy and Braun-Lewensohn, 2009 ). In the present study, we suggest that the situation we are examining is a chronic-stress situation, as the pandemic has been with us since February–March of 2019.

Psychological Distress in a Chronic-Stress Situation

Stress encompasses cognitive, emotional, physical/somatic, and social variables ( Lazarus and Folkman, 1984 ). Research conducted during normal times among a representative sample of Israeli adults to identify baseline levels of various psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, and somatization found very low levels of each of those problems ( Gilbar and Ben-Zur, 2002 ). However, research conducted during various stressful situations has shown that individuals who are exposed to stressful situations, including a pandemic, tend to be especially vulnerable to developing common psychological problems, including somatization, anxiety, and depression. More specifically, the lockdowns and curfews that were implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic influenced psychological problems and distress, including anxiety and depression, as noted in several recent studies ( Hossain et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ).

Demographic Characteristics

In various contexts and countries, the resiliency factors of SOC and hope have been analyzed with regard to gender and no significant gender differences have been found for either variable ( Roothman et al., 2003 ; Maree et al., 2008 ; Van Schalkwyk and Rothmann, 2008 ; Braun-Lewensohn and Mosseri Rubin, 2014 ). In general ( Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001 ; Gronning et al., 2018 ), and during the COVID-19 pandemic specifically, women have been shown to be more likely to develop psychological problems and distress, including anxiety, depression, and somatization ( Liu et al., 2020 ; Sfendla and Hadrya, 2020 ).

Antonovsky (1987) claimed that SOC continues to develop until the age of 30, at which point it stabilizes. However, several studies from the last decade have claimed that SOC continues to develop and strengthen during adulthood (beyond age 30) and declines as individuals approach old age ( Nilsson et al., 2010 ; Braun-Lewensohn and Sagy, 2014 ). Similarly, the hope construct is strengthened during adulthood and weakens in old age ( Bailey and Snyder, 2007 ).

As for the outcome variables of psychological distress, several studies have suggested that during stressful events younger adults are more exposed to social media and news, which results in more anxiety, depression, and somatization. This has also been found in the context of the current pandemic ( Qiu et al., 2020 ; Sfendla and Hadrya, 2020 ).

Socio-Economic Status (SES)

SES is among the general resiliency resources that Antonovsky (1987) suggested are important for the development of a strong SOC. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated that the higher individuals' socio-economic status, including education and income, the stronger their SOC ( Volanen et al., 2004 ). Similarly, low SES was found to be associated with lower levels of hope; whereas high SES was found to be associated with higher levels of hope ( Snyder, 2002 ). Finally, low-SES individuals have been found to report more psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, and somatization, as compared to their high-SES counterparts ( De Mello et al., 2013 ) also during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Patel et al., 2020 ).

Cultural Groups Examined in This Study

Israeli jews.

Diversity in Israel includes not only the variety of ethnicities that constitute the country's overall population, but also the cultural variety within the Jewish majority, a significant proportion of which (more than 30%) is made up of immigrants. A third of the Jewish population defines itself religiously as “traditional”; whereas another third defines itself as “religious,” or “very religious” ( Bistrov and Sofer, 2010 ). Overall, Jewish Israeli society is considered a Western, individualistic society ( Sagy et al., 2001 ).

Ultra-Orthodox Society

The population of Ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel numbers about 1,125,000, accounting for ~12.5% of the country's population ( Cahaner and Malach, 2019 ). They represent a significant minority group in Israeli society. The Ultra-Orthodox do not differ from the majority group in terms of race or nationality, but are separated by ideological, religious, and social motivations, which unite them ( Brown, 2017 ). Researchers of Ultra-Orthodox society usually divide this sector into three main groups: Hasidic, Lithuanian ( Misnagdim ), and Mizrahi ( Brown, 2017 ). However, in a general sense, when relating to these three groups, we may point to two characteristics common to all of them: Torah study as a constitutive value and social isolation. These two values are central to these communities. However, in recent years, social and economic changes have stretched the boundaries of Ultra-Orthodox communities and the effects of these changes are still unfolding ( Braun-Lewensohn and Kalagy, 2019 ).

The Ultra-Orthodox community can be characterized as a religious collectivist community, with very high levels of social capital relative to other populations in Israeli society. Consequently, the Ultra-Orthodox individual is surrounded by three concentric groups: the family, the community, and the public. These three circles provide members of the Ultra-Orthodox community with physical and spiritual support, alongside demands for the normative behavior accepted in the community ( Bart and Ben-Ari, 2015 ). The social capital of this community has been written about in the research literature in the contexts of health and mental well-being. Tchernichovsky and Sharoni (2015) found that the health of the Ultra-Orthodox population is better than would be expected based on their socio-economic status. Among this population, social capital affects health mainly through psychosocial support, including community aid, which reduces mental stress. This is despite the fact that it does not seem that this population has any greater access to medical services or organizations, as compared to other groups in Israel ( Tchernichovsky and Sharoni, 2015 ).

Arabs in Israel

The Arab minority comprises about 21% of the entire Israeli population and includes Muslims (83%), Christians (9%), and Druze (8%; Gharrah, 2012 ; Central Bureau of Statistics (Israel), 2020 ). Arab society is highly collectivistic-patriarchal, although it is currently undergoing a rapid process of transition ( Al-Haj, 1988 ; Haj Yahia-Abu Ahmad, 2006 ; Azaiza, 2013 ). In this context, inequalities based on gender and age (and, in recent years, also education) are very common ( Al-Haj, 1988 ; Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005 ). This minority society differs from Jewish Israeli society in that it is less individualistic and more authoritarian and in its emphasis on connectedness and social relationships with meaningful others in one's social environment ( Haj Yahia, 2019 ). Arabs also differ from the Jewish majority in terms of language, religion, and other cultural factors ( Al-Krenawi et al., 2009 ). Arabs in Israel are a largely disadvantaged minority with major determinants of mental-health problems, including political, social, cultural, and economic factors ( Abu-Kaf, 2019 ). The Arab minority is subject to various forms of discrimination that may contribute to social and economic disparities between them and the Jewish majority ( Ghanem, 2001 ; Okun and Friedlander, 2005 ; Pinson, 2007 ; Yiftachel, 2009 ; Knesset Research and Information Center, 2016 ). The Arab community suffers from poverty, harsh living conditions, violence, discrimination and stigma, and poor employment and working conditions ( Keinan and Bar, 2007 ; The Galilee Society-The Arab National Society for Health Research and Services, 2013 ; Central Bureau of Statistics, 2015 ; Knesset Research and Information Center, 2015 ).

The above-mentioned cultural groups have been examined in various studies with regard to the variables examined the present study. Due to numerous SES factors, in addition to their national status, Arabs in Israel have been found to suffer from more psychological problems and distress (e.g., depression, somatization, and anxiety) than their Jewish counterparts ( Haberfeld and Cohen, 2007 ; Baron-Epel et al., 2010 ; Abu-Kaf, 2019 ). As for the other variables, it has been found that Ultra-Orthodox individuals express the strongest SOC, followed by secular Jews, and then Israeli Arabs (e.g., Abu-Kaf et al., 2017 ; Kalagy et al., 2017 ). The picture is more complicated when comparing secular Jews and Bedouin Arabs in terms of various factors of hope. In a previous study, Bedouin Arabs reported stronger collective hope than Secular Jews, but no differences were found between those two groups in terms of individual hope. As for the explanation of numerous psychological problems by SOC and hope, while SOC was found to be the strongest predictor of a lack of psychological symptoms among Jews, hope was found to be the strongest among Arabs ( Braun-Lewensohn and Sagy, 2010 ).

In this study, we sought to explore the prevalence of the major resiliency factors of SOC and hope, as well as psychological distress (in terms of anxiety, depression, and somatization) among three cultural groups in Israel (i.e., secular Jews, Ultra-Orthodox Jews, and Arabs). We compared these variables among these groups and estimated the contributions of the resiliency factors to the explanation of the reported psychological distress. We further evaluated the roles of the sociodemographic variables of gender, age, and SES in explaining psychological distress during the long-term Covid-19 pandemic. Based on the salutogenic model ( Antonovsky, 1987 ) and the hope theory ( Snyder, 2000 ), we hypothesized that individuals with strong SOC and high levels of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and transpersonal hope would be more resilient and, therefore, would react with less anxiety, depression, and somatization ( Gómez-Salgado et al., 2020 ; Trzebiński et al., 2020 ). We further hypothesized that women, low-SES individuals, and older individuals would be more vulnerable during the pandemic and that those factors would contribute to higher levels of stress ( De Mello et al., 2013 ; Sfendla and Hadrya, 2020 ).

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Data were gathered from 248 secular Jews (Age: M = 39.76, SD = 13.58), 243 Ultra-Orthodox Jews (Age: M = 37.50, SD = 12.70), and 203 Arabs (Age: M = 33.95, SD = 10.46), who were all 18–70 years old ( F = 12.50, p < 0.001). Women accounted for 50.4% of the secular group ( n = 113), 53.4% of the Ultra-Orthodox group ( n = 118), and 57.9% of the Arab group ( n = 106; χ 2 = 2.22, p = 0.32). SES was evaluated in terms of three levels: below-average salary, average salary, and above-average salary. In our sample, a below-average salary was reported by 118 (52.7%) of the secular participants, 147 (66.5%) of the Ultra-Orthodox participants, and 126 (68.9%) of the Arab participants. An average salary was reported by 55 (24.6%) of the secular participants, 37 (16.7%) of the Ultra-Orthodox participants, and 32 (17.5%) of the Arab participants. An above-average salary was reported by 51 (22.8%) of the secular participants, 37 (16.7%) of the Ultra-Orthodox participants, and 25 (13.7%) of the Arab participants (χ 2 = 14.27, p < 0.01).

All of the ethical guidelines applicable to this study were followed. The study was approved by the Human Subjects Ethics Committee of the Conflict Management and Resolution Program at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (Approved Ethics Form No. 2020-008). Participants completed self-report questionnaires in mid-September 2020, just before the Jewish New Year, as a second curfew was being announced and after ~6 months of the Covid-19 pandemic. The participants were recruited by the midgam panel ( https://www.midgampanel.com/ ) and were informed that the researchers were interested in their experiences. They were also informed that their participation was voluntary and anonymous and that they were free to withdraw their participation for any reason at any time during the questionnaire procedure.

Demographics

Participants were asked to report their gender, age, and SES. SES was measured by one question in which participants were presented the average salary in Israel and had to report whether they earn below the Israeli average salary, average salary or above the Israeli average salary.

We used the 18-item, short version of a hope questionnaire ( Jacoby and Goldzweig, 2014 ). Each item was scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 ( do not agree at all ) to 4 ( totally agree ). In addition to a global scale of hope, this questionnaire included three subscales: interpersonal hope (five items; i.e., I draw strength from the relationships in my life ), intrapersonal hope (nine items; i.e., At difficult times in my life, I trust myself that I will be able to get out of the difficult situation ), and transpersonal hope (four items; i.e., I have a belief that gives me a sense of comfort ). In the present study, the mean of the relevant items was computed for each subscale. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was α = 0.88 for both the intrapersonal scale and the transpersonal scale. For the interpersonal scale, it was α = 0.83.

Sense of Coherence (SOC)

SOC was measured using an instrument ( Antonovsky, 1987 ) that included a series of items scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale that had anchoring phrases at each end. High scores indicate a strong SOC. An account of the development of the SOC scale and its psychometric properties, showing it to be reliable and reasonably valid, appears in Antonovsky (1987 , 1993) writings. In this study, SOC was measured using the short-form scale consisting of 13 items, which has been found to be highly correlated to the original long version ( Antonovsky, 1993 ). The scale includes items such as: “ Doing the things you do every day is ” with answers ranging from 1 ( a source of pain and boredom ) to 7 ( a source of deep pleasure and satisfaction ). In the present study, the mean was calculated and Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.82.

We used the short version of the Brief Symptom Inventory ( Derogatis and Fitzpatrick, 2004 ), which is comprised of 18 items that are each rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 – not at all ; 4 – very much ). This questionnaire examines three areas of psychological and psychiatric problems: somatization, depression, and anxiety. The reliability of the short version of the questionnaire and its three subscales has been reported to be good ( Franke et al., 2017 ). Here are examples of items from each subscale. Somatization: “ To what extent have you felt faint or experienced dizziness?” Anxiety: “ To what extent have you suffered from a feeling of stress?” Depression: “ To what extent have you suffered from a feeling of depression?” The Cronbach's alpha coefficients for each of the stress indices (i.e., anxiety, depression, and somatization) and for the global severity index were all α = 0.88.

Statistical Analyses

To address our first objective, frequencies and standard deviations of each variable were computed. The second objective related to the comparison of the three cultural groups and One-way ANOVA was conducted. Finally, to evaluate the model in which the sociodemographic factors of gender, age, and SES and the resiliency factors of SOC and the three dimensions of hope explain the psychological/emotional distress (i.e., anxiety somatization, and depression) in each group, structural equation modeling was conducted using the AMOS 26 program ( Arbuckle and Wothke, 1999 ).

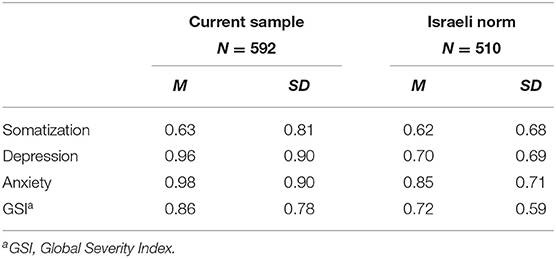

For most of the stress indices, our results were higher than the community adult Israeli norms ( Gilbar and Ben-Zur, 2002 ). The average scores for all of the resiliency factors, namely, SOC and the various hope scales, were also at the upper end of the scales ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 . Means and SD s of the psychological-distress variables measured in this study, as compared to Israeli norms.

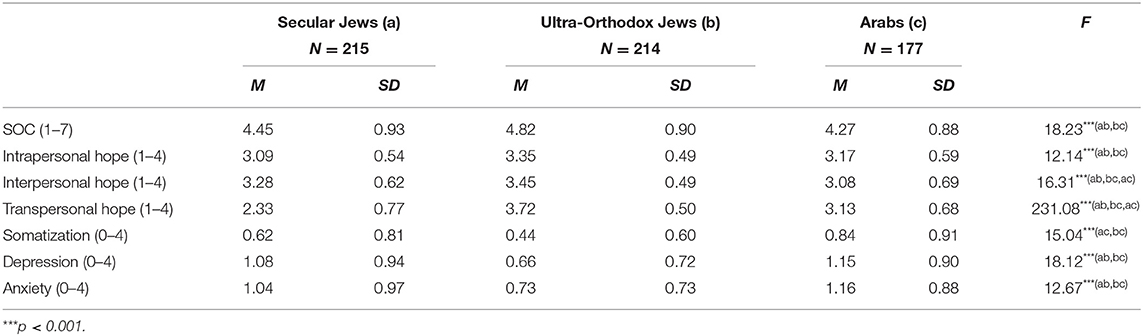

Significant differences were found among all of the examined variables (see Table 2 ). The most prevalent differences were found between the Ultra-Orthodox group and the other two groups. In all cases, the Ultra-Orthodox group reported higher levels of resiliency factors and lower levels of psychological distress. Differences were also found between secular Jews and Arabs in two of the three hope scales. Secular Jews reported higher levels of interpersonal hope; whereas Arabs reported higher levels of transpersonal hope. As for psychological distress, a significant difference was found only for somatization, with the Arab group reporting more somatization than the secular group.

Table 2 . Differences between the groups in terms of the main variables.

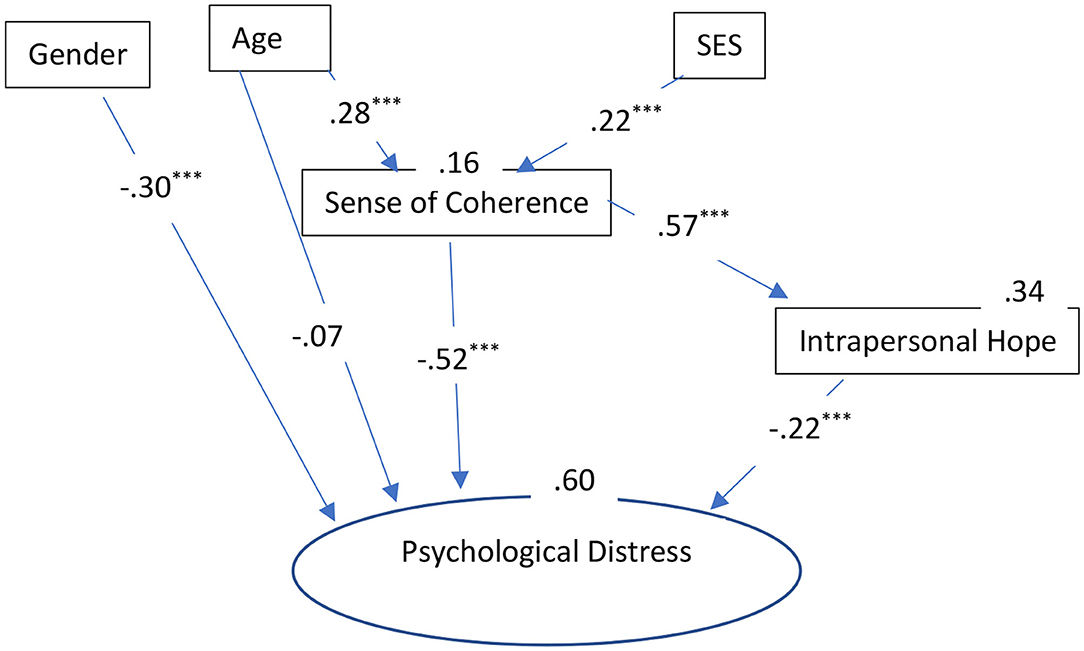

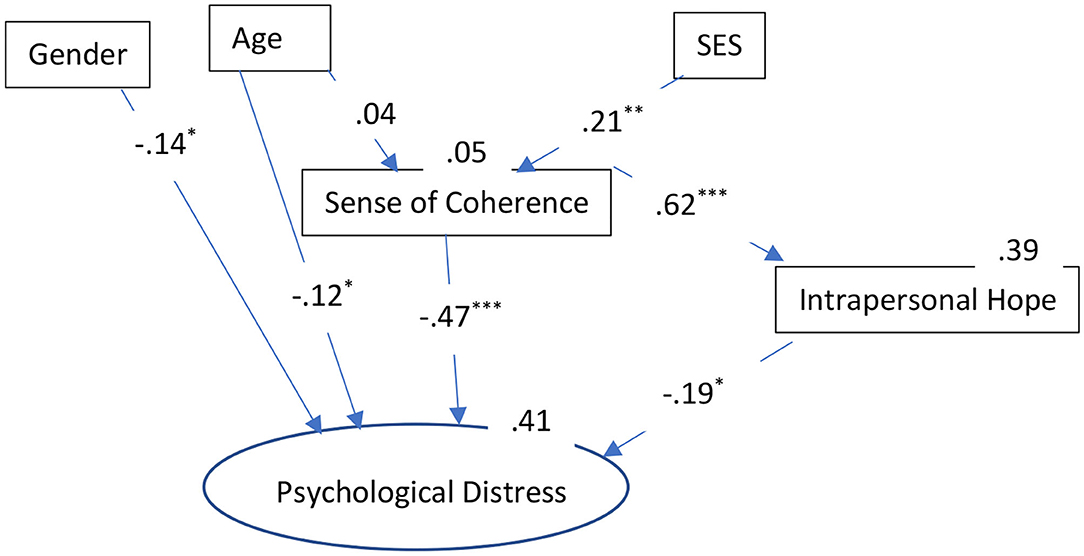

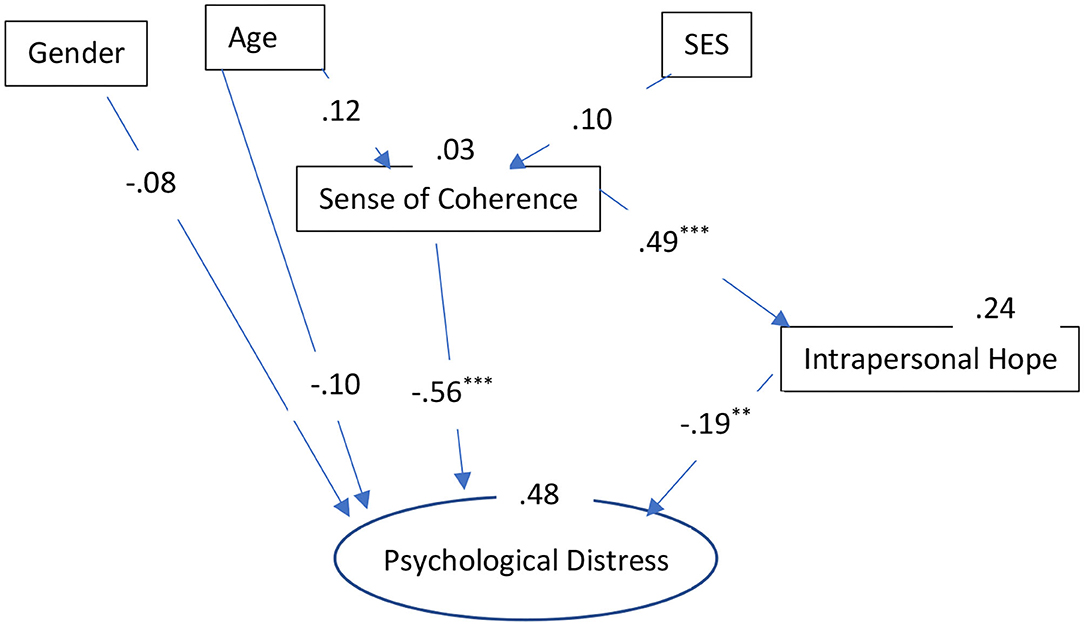

We used multi-group analysis to compare the effects of the different resiliency factors among each group (i.e., secular Jews, Ultra-Orthodox Jews, and Arabs). The mean for each scale was computed separately and used as a manifest variable. For psychological distress (the dependent variable), a latent variable was created using the three dimensions of stress reactions as indicators (i.e., somatization, depression, and anxiety). Model fit was assessed using the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ 2 / df ) incremental fit index (IFI; Bollen, 1989 ), the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990 ), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne and Cudeck, 1993 ). Acceptable fit is indicated by a χ 2 /df ratio of 3 or less ( Carmines and McIver, 1981 ), IFI and CFI equal to or >0.90, and RMSEA of <0.08 ( Browne and Cudeck, 1993 ; Hoyle, 1995 ). The indices were adequate for the overall model: χ ( 54 ) 2 = 137.29, p < 0.001; χ 2 / df = 2.86; CFI = 0.95; IFI = 0.95; and RMSEA = 0.05 ( Figures 1 – 3 ).

Figure 1 . The roles of sociodemographic and resiliency factors in explaining psychological distress: Results of the path analysis for secular Jews. *** p < 0.001. SES, Socio-Economic Status.

Figure 2 . The roles of sociodemographic and resiliency factors in explaining psychological distress: Results of the path analysis for Ultra-Orthodox Jews. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. SES, Socio-Economic Status.

Figure 3 . The role of sociodemographic and resiliency factors in explaining psychological distress: Results of the path analysis for Arabs. ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. SES, Socio-Economic Status.

The final SEM, presents only significant relationships, as variables that were not significant for the explanation of the stress indices were deleted from the final model. The overall model explained 60% of the variance in psychological distress among the secular Jews, 41% of the variance among the Ultra-Orthodox Jews, and 48% of the variance among the Arabs. The indirect effects of the various variables on psychological distress were as follows. Secular Jews : SES (−0.14), age (−0.18), SOC (−0.13); Ultra-Orthodox: SES (−0.12), age (−0.02), SOC (−0.12); and Arabs: SES (−0.07), age (−0.08), SOC (−0.09).

It is important to note that, as for the socio-demographic factors, it is clear that being a women in the secular group had a powerful and significant effect on the development of the examined forms of psychological distress, while it had less of an effect in the Ultra-Orthodox group and no effect in the Arab group. Age also had different effects on psychological distress. In terms of the total direct and indirect effect, age seemed to have the most powerful effect in the secular group (−0.25), followed by the Arab group (−0.18), and, to a lesser extent, in the Ultra-Orthodox group (−0.14); with younger individuals experiencing greater psychological distress. Lastly, SES was also most powerful among the secular group with a total effect (direct and indirect) of −0.14, less powerful among the Ultra-Orthodox group (−0.12), and least powerful among the Arab group (−0.07).

These results indicate that, in all three groups, the resiliency factors were the most prominent in their contributions to the explanation of the psychological distress, with SOC having the strongest effect [secular Jews: total effect (−0.65); Arabs: total effect (−0.64); and Ultra-Orthodox Jews: total effect (−0.59)]. In order to test the differences in the strength of the relationships between the resiliency factors and the dependent variable, the effects of SOC and intrapersonal hope on psychological distress were examined using a nested model. Equality constraints among groups were assigned for each effect, to allow for the comparison of the constrained model with the free model. Statistical differences were found for the variables as follows: SOC and psychological distress [( χ ( 51 ) 2 = 1056.7); Δ χ ( 3 ) 2 = 919.41; p < 0.001] and intrapersonal hope and psychological distress [( χ ( 51 ) 2 = 595.7); Δ χ ( 3 ) 2 = 458.41; p < 0.001]. This means that despite the fact that these variables made important and significant contributions to stress in all three groups, SOC and intrapersonal hope differed significantly in their contributions to psychological distress in the three groups. Both variables had the greatest contribution to psychological distress in the secular group.

The aim of this study was to compare three major cultural groups in Israel against the backdrop of a second lockdown during the Covid-19 pandemic. First, we explored the prevalence of psychological distress (i.e., anxiety, depression, and somatization), as well as resiliency factors among individuals in Israeli society. Second, we examined differences between the cultural groups in terms of the main study variables. Then, through the prism of several resiliency theories (i.e., salutogenesis, hope, and self-transcendence, which are all rooted in positive psychology), we attempted to examine how hope and SOC explain psychological distress in those cultural groups.

Our results show that, overall, during the pandemic, Israelis reported increased psychological distress, as compared to non-crisis times. These results replicate results from countries around the world which also reported elevated stress symptoms (e.g., Husky et al., 2020 ; Rossi et al., 2020 ). It seems that the ongoing stressful situation, together with the fact that people were just days before the second lockdown, brought individuals meaningful stress that led to anxiety and depression. Moreover, the fact that people had hardly gotten back to normal life led them to feel that they were giving up major parts of their life. In addition, the fact that this was the second time in which major Jewish holidays were to be celebrated only with the people with whom one lived, as opposed to celebrations with extended families, caused a great deal of distress.

Our second aim was to compare Ultra-Orthodox Jews, secular Jews, and Arabs, in terms of resiliency factors and psychological distress. Overall, it can be stated that the Ultra-Orthodox group reported the strongest resiliency factors and, correspondingly, suffered the fewest symptoms of psychological distress. This could be due to the fact that Ultra-Orthodox individuals have strong faith in God, which leads them to experience a meaningful life, which leads, in turn, to better mental health ( Wong, 2019 , 2020a ). These results might also be a result of the traditional structure of the Ultra-Orthodox family ( Cahaner and Malach, 2019 ). Ultra-Orthodox society is characterized by large families with many children living in dense communities. Feelings of loneliness are less frequent in such environments, which, in turn, leads to lower levels of the types of psychological distress evaluated in this study. Additionally, throughout the years it was found that religious practices and beliefs are positively related to life satisfaction, happiness and other indicators of mental well-being ( Koenig, 2001 ; Guillford, 2002 ). Thus, it seems that religious belief provides a positive worldview, which gives meaning to experiences, whether positive or negative. This is significant because it provides a sense of purpose in life, an optimistic attitude and a high level of hope ( Pargament et al., 2000 ; Koenig, 2001 ). In addition, religious beliefs can evoke positive emotions, such as joy, neutralizing or relieving stress in daily life ( Koenig, 2001 ).

From the examination of symptoms of psychological distress, it appears that both the secular Jews and the Arabs experienced high levels of distress. During regular times, members of Arab society in Israel suffer from more psychological distress than Jews, due to their political and economic status (i.e., lower participation in the workforce, lower income, and lower educational attainment), as well as social factors such as inferior social position, social exclusion, and an intense conflictual relationship with the Jewish majority ( Kaplan et al., 2010 ; Abu-Kaf, 2019 ; Abu-Kaf et al., 2020 ). It should be noted that also around the world, during the COVID-19 pandemic, minorities including Muslim Arabs reported elevated levels of stress ( Miconi et al., 2020 ). However, the significance of our results is that during this pandemic, it seems that secular Jewish society closed this gap with regards to psychological distress. Strong distrust in elected officials and representatives and their decisions, which appeared to the public to be random and based not on the actual situation on the ground, but rather on political pressure, led individuals to feelings of helplessness, which turned into distress.

Our results can be interpreted through the lens of the second wave of positive psychology (PP.2). This wave explores the negative sides of life while highlighting its optimistic parts and focusing on the productive functioning of individuals ( Mayer et al., 2019 ; Mayer and Vanderheiden, 2020 ). Therefore, in spite of the fact, that negative outcomes of psychological distress have emerged as result of the health pandemic, it could be, that it is only a first stage in which individuals can explore their situation and grow out of these difficulties which will transform also to positive outcomes.

Our main objective related to the explanation of psychological distress (i.e., somatization, anxiety, and depression) by the various demographic and resiliency factors (i.e., SOC and hope) and the examination of differences between the three cultural groups. Overall, in all three groups, the main resiliency factors of SOC and hope explained psychological distress significantly and powerfully. It should be mentioned that among the various components of hope, only the intrapersonal component was significant in all three groups.

Likewise other studies during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Barni et al., 2020 ) the most significant and meaningful factor that most powerfully explained the psychological/emotional distress in the three cultural groups was SOC, with its three dimensions of comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness.

Similarly, the self-transcendence theory, which is the meaningfulness dimension of SOC, has seemed to be the most important component across studies ( Eriksson and Mittelmark, 2017 ). Thus, it seems that creating meaning for life, aside from being able to comprehend and manage one's life even during the chronic-stress situation of a pandemic, helps individuals from various cultures and backgrounds to better handle the situation, and, therefore, to suffer from less psychological distress. These results add significant knowledge to that provided by previous research, which compared acute and chronic situations of political violence and found that in chronic-stress situations among Western secular cultures, SOC serves as a major protective factor against psychological distress ( Sagy and Braun-Lewensohn, 2009 ).

The second important factor to explain psychological distress in the current study was intrapersonal hope, which means turning into oneself in order to assess one's resources. Our results elaborate understanding relating to basic and global hope during pandemic ( Trzebiński et al., 2020 ). Intrapersonal hope is connected to self-transcendence and allows the individual to be conscious of his/her internal resources and to apply those resources in the wider environment. Thus, it seems that positive, hopeful thoughts serve as significant protective factor in the face of the chronic stress of a pandemic.

In light of PP 2.0 it seems that those individuals who felt suffering as the starting point, were able to discover ways in which they adopt to the situation and transform their pain, distress and suffer to positive elements such as hope and SOC, which in turn result in wellbeing and strengths ( Wong, 2020b ). This processes of turning pain and suffer into growth and strength might be similar to the relationships which can be found throughout research between post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth (i.e., Liu et al., 2017 ).

A striking result emerged from our examination of the effect of gender on psychological distress. Similarly to results from populations around the world ( Spoorthy et al., 2020 ), being a secular woman meant being more vulnerable to the development of psychological distress. However, in the two more traditional and religious societies, the role of gender was less prominent. The gap between Ultra-Orthodox and Arab women, on the one hand, and secular women, on the other, might be explained in two possible ways. First, in traditional societies, women are very significant and influential in the communal and household spheres. Thus, in times of stress and crisis, the responsibility that they carry on their shoulders obligates them to act optimally and, as result, they do not allow themselves to be vulnerable. Moreover, as part of more traditional and collectivistic cultural contexts and regardless of their limited material resources, Ultra-Orthodox and Arab women are more directed toward self-transcendence, which means that their fundamental attitudes toward life involve less egotistic focus and more caring for others or for something greater than themselves ( Wong, 2020a ). This fundamental attitude protects them from psychological distress during stressful times. Second, as stated previously, the unique family structures of these two traditional societies, in which women are surrounded by many people, protects them from being lonely, depressed, and distressed. Religious and spiritual beliefs also strengthen feelings of being protected and empowerment among these groups of women. Additionally, leaders and authority figures in the Ultra-Orthodox community are in touch with the women of that community and provide encouragement, while secular women do not have such figures on whom to rely.

In the context of Arab society, this finding may be explained by the more traditional division of gender roles, in general, and in the home, in particular ( Abu-Kaf, 2019 ; Haj Yahia, 2019 ; Abu-Kaf et al., 2020 ). During the lockdown, Arab men experienced difficulty staying at home with no clear chores or responsibilities. It seems that Arab men closed the gap in psychological distress levels with Arab women during the health pandemic and, especially, during the lockdown period.

Study Limitations

Information about their experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic was provided only by the individual themselves and, therefore, the collected data are subjective. In addition, because we lack baseline information about the rates of psychological distress and resiliency factors among the surveyed individuals prior to the study period, we cannot with certainty ascribe the outcomes solely to the impact of the examined stressful situation.

Despite these limitations, the importance of this study lies in the fact that it is a field study carried during a stressful situation, which provided as a natural laboratory for the investigation of human behavior ( Lazarus, 1982 ). It is also important to note that the secular Jewish, Ultra-Orthodox, and Arab communities are heterogeneous and include different subgroups. Future research should include large samples from the three populations and should pay more attention to variability within each population.

The aim of this study was to evaluate stress and resiliency in three cultural groups in Israel. Through the lens of PP.2 the covid-19 pandemic enabled us to understand how a harsh situation of health pandemic, can lead to suffer, but then facilitate power, growth and strength. Our main results show that while the Ultra-Orthodox group exhibited resiliency, the two other groups (i.e., secular Jews and Arabs) suffered from major psychological distress. However, when we examined how the resiliency factors of SOC and hope explain the symptoms of psychological distress, similar results emerged among the three groups, with SOC having the strongest effect, followed by intrapersonal hope.

These results lead to important policy recommendations. Action must be taken to raise the awareness of decision-makers of the great importance of the mental well-being of residents during health crises. This aspect has been neglected in relation to other urgent issues, such as employment and economic and physical health. The allocation of resources including sense of coherence ( Castiglioni and Gaj, 2020 ) for the improvement of existing mechanisms and strengthening the provision of mental-health services are critical tasks at this time.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Ethics Committee of the Conflict Management and Resolution Program at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (Approved Ethics Form No. 2020-008). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

OB-L wrote the manuscript, ran, and analyzed the data. SA-K and TK contributed to writing and analyzing the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corona Challange Covid-19 BGU. Project no. 87793311.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors OB-L.

Abu-Kaf, S. (2019). Mental health issues among Palestinian women in Israel. Ment. Health Palest. Citiz. Isr . 121–148. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvpj7j65.11

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Abu-Kaf, S., Braun-Lewensohn, O., and Kalagy, T. (2017). Youth in the midst of escalated political violence: sense of coherence and hope among Jewish and Bedouin Arab adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Ment. Health 11:42. doi: 10.1186/s13034-017-0178-z

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Abu-Kaf, S., Nakash, O., Hayat, T., and Cohen, M. (2020). Emotional distress among the Bedouin Arab and Jewish elderly in Israel: the roles of gender, discrimination, and self-esteem. Psychiatr. Res . 291:113203. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113203

Al-Haj, M. (1988). The changing Arab kinship structure: the effect of modernization in an urban community. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 36, 237–258. doi: 10.1086/451650

Al-Krenawi, A., Graham, G. R., Al-Bedah, E. A., Kadri, H. M., and Sehwail, M. A. (2009). Cross-national comparison of Middle Eastern university students: help-seeking behaviors, attitudes toward helping professionals, and cultural beliefs about mental health problems. Community Ment. Health J . 45, 26–36. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9175-2

Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, Stress, and Coping: New Perspectives on Mental and Physical Well-Being . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the Mystery of Health . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Google Scholar

Antonovsky, A. (1993). The Structure and Properties of the Sense of Coherence Scale. Soc. Sci. Med . 36, 725–733. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z

Arbuckle, J. L., and Wothke, W. (1999). Amos 4.0 User's Guide . Chicago, IL: Small Waters.

Azaiza, F. (2013). Processes of conservation and change in Arab society in Israel: implications for the health and welfare of the Arab population. Int. J. Soc. Welfare 22, 15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00866.x

Bailey, T. C., and Snyder, C. R. (2007). Satisfaction with life and hope: a look at age and marital status. Psychol. Record. 57, 233–240. doi: 10.1007/BF03395574

Barni, D., Danioni, F., Canzi, E., Ferrari, L., Ranieri, S., Lanz, M., et al. (2020). Facing the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of sense of coherence. Front. Psychol. 11:578440. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.578440

Baron-Epel, O., Kaplan, G., and Moran, M. (2010). Perceived discrimination and health related quality of life among Arabs, immigrants and veteran Jews in Israel. Public Health 10:282. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-282

Bart, A., and Ben-Ari, A. (2015). Personal and social adjustment to divorce in a Haredi community in Israel. (Hebrew). Haredi Soc. Stud . 2, 88–116.

Bentler, P. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull . 107, 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Bistrov, Y., and Sofer, A. (2010). Israel's Demography 2010-2030: On the Path to a Religious State . Haifa, Israel: Haifa University, Haykin, Cathedra (Hebrew).

Bollen, K. (1989). Structural Equations with Latent Variables . New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. doi: 10.1002/9781118619179

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text

Braun-Lewensohn, O., and Kalagy, T. (2019). Between the inside and the outside world: coping of Ultra-Orthodox individuals with their work environment after academic studies. Community Ment. Health J . 55, 894–905. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00392-x

Braun-Lewensohn, O., and Mosseri Rubin, M. (2014). Personal and communal resilience in communities exposed to missile attacks: does intensity of exposure matter? J. Posit. Psychol . 9, 175–182. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.873946

Braun-Lewensohn, O., and Sagy, S. (2010). Sense of coherence, hope and values among adolescents under missile attacks: a longitudinal study. Int. J. Child. Spiritual . 15, 247–260. doi: 10.1080/1364436X.2010.520305

Braun-Lewensohn, O., and Sagy, S. (2014). Community resilience and sense of coherence as protective factors in explaining stress reactions: comparing cities and rural communities during missiles attacks. Community Ment. Health J . 50, 229–234. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9623-5

Brown, B. (2017). The Ultra-Orthodox: A Guide to Their Beliefs and Sectors . Jerusalem: Am-Oved and the Israel Democracy Institute (Hebrew).

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1993). “Alternative ways of assessing model fit,” in Testing Structural Equation Models , eds K. A. Bollen, and J. S. Long (Newbury Park, CA: Sage), 136–162.

Cahaner, L., and Malach, G. (2019). Statistical Report on Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) Society in Israel 2019 . Jerusalem: The Israel Democracy Institute (Hebrew).

Carmines, E. G., and McIver, J. P. (1981). “Analyzing models with unobserved variables,” in Social Measurement: Current Issues , eds G. W. Bohrnstedt, and E. F. Borgatta (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage).

Castiglioni, M., and Gaj, N. (2020). Fostering the reconstruction of meaning among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11:2741. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567419

Central Bureau of Statistics (2015). Statistical Abstracts of Israel . Available online at: http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnaton/shnatone_new.htm?CYear=2015andVol=66andCSubject=30 (accessed January 25, 2017).

Central Bureau of Statistics (Israel) (2020). Statistical Abstract of Israel, 2020 . Available online at: https://www.cbs.gov.il/en/mediarelease/Pages/2020/Israe-Independence-Day-2020.aspx (accessed December 1, 2020).

De Mello, M. T., de Aquino Lemos, V., Antunes, H. K. M., Bittencourt, L., Santos-Silva, R., and Tufik, S. (2013). Relationship between physical activity and depression and anxiety symptoms: a population study. J. Affect. Dis . 149, 241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.035

Derogatis, L. R., and Fitzpatrick, M. (2004). “The SCL-90-R, the brief symptom inventory (BSI), and the BSI-18.” in The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment: Instruments for Adults , ed M. E. Maruish (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 1–41.

Erikson, E. H., Erikson, J. M., and Kivnick, H. Q. (1994). Vital Involvement in Old Age . New York, NY: WW Norton and Company.

Eriksson, M., and Mittelmark, M. B. (2017). “The sense of coherence and its measurement,” in The Handbook of Salutogenesis , eds M. Mittelmark, S. Sagy, M. Eriksson, G. F. Bauer, J. M. Pelikan, B. Lindsrom and G. A. Espnes (Cham: Springer), 97–106. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6_12

Franke, G. H., Jaeger, S., Glaesmer, H., Barkmann, C., Petrowski, K., and Braehler, E. (2017). Psychometric analysis of the brief symptom inventory 18 (BSI-18) in a representative German sample. BMC Med. Res. Method . 17:14. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0283-3

Ghanem, A. (2001). The Palestinian-Arab minority in Israel, 1948-2000: A political study . New York, NY: State University of New York Press.

Gharrah, R. (2012). Arab Society in Israel , 5th Edn. Jerusalem: The Van Leer Institute.

Gilbar, O., and Ben-Zur, H. (2002). Adult Israeli community norms for the brief symptom inventory (BSI). Int. J. Stress Manag . 9, 1–10. doi: 10.1023/A:1013097816238

Gómez-Salgado, J., Domínguez-Salas, S., Romero-Martín, M., Ortega-Moreno, M., García-Iglesias, J. J., and Ruiz-Frutos, C. (2020). Sense of coherence and psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Sustainability 12:6855. doi: 10.3390/su12176855

Gronning, K., Espnes, G. A., Nguyen, C., Ferreira, A. M., Gregorio, M. J., Sousa, R., et al. (2018). Psychological distress in elderly people is associated with diet, wellbeing, health status, social support and physical functioning—A HUNT3 study. BMC Geriatr . 18:205. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0891-3

Guillford, L. (2002). Spiritual care and psychiatric treatment: an introduction. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 8, 249–261. doi: 10.1192/apt.8.4.249

Haberfeld, Y., and Cohen, Y. (2007). Gender, ethnic, and national earnings gaps in Israel: the role of rising inequality. Soc. Sci. Res . 36, 654–672. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.02.001

Haj Yahia, M. (2019). “The Palestinian family in Israel,” in Mental Health and Palestinian Citizens in Israel (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press), 97–120. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvpj7j65.10

Haj Yahia-Abu Ahmad, N. (2006). Couplehood and parenting in the Arab family in Israel: Processes of change and preservation in three generations . [unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Haifa: University of Haifa (Hebrew).

Hofstede, G., and Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Culture and organizations: Software of the mind , 2nd Edn. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hossain, M. M., Tasnim, S., Sultana, A., Faizah, F., Mazumder, H., Zou, L., et al. (2020). Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Res . 9:636. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.24457.1

Hoyle, R. H. (1995). Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Husky, M. M., Kovess-Masfety, V., and Swendsen, J. D. (2020). Stress and anxiety among university students in France during Covid-19 mandatory confinement. Compr. Psychiatry 102:152191. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152191

Jacoby, R., and Goldzweig, G. (2014). “The many faces of hope,” in Paper Presented at the 6th Global Conference of Hope (Prague, Czech Republic).

Kalagy, T., Braun-Lewensohn, O., and Abu-Kaf, S. (2017). Youth from fundamentalist societies: what are their attitudes toward war and peace and their relations with anxiety reactions? J. Relig. Health 56, 1064–1080. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0358-4

Kaplan, G., Glasser, S., Murad, H., Atamna, A., Alpert, G., Goldbourt, U., et al. (2010). Depression among Arabs and Jews in Israel: a population-based study. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol . 45, 931–939. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0142-1

Keinan, T., and Bar, D. (2007). Mobility Among Arab Women in Israel . Haifa, IL: Kayan Feminist Organization.

Knesset Research Information Center (2015). Employment of Arab women - data, Barriers and Recommendations (Hebrew) . Jerusalem, IL: Author. Available online at: www.knesset.gov.il/committees/heb/material/data/avoda2015-07-27-00-03.pdf (accessed December 1, 2020).

Knesset Research Information Center (2016). Public Transportation Services in Arab Communities- A Snapshot (Hebrew) . Jerusalem, IL: Author. Available online at: http://knesset.gov.il/committees/heb/material/data/kalkala2016-02-22-00-02.pdf (accessed December 1, 2020).

Koenig, H. G. (2001). Religion and medicine II: religion, mental health, and related behaviors. Int. J. Psychiatry Med . 31, 97–109. doi: 10.2190/BK1B-18TR-X1NN-36GG

Lazarus, P. J. (1982). Incidence of shyness in elementary-school age children. Psychol. Rep . 51, 904–906. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1982.51.3.904

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and Adaptation . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lazarus, R. S., and Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping . New York: Springer.

Lei, L., Huang, X., Zhang, S., Yang, J., Yang, L., and Xu, M. (2020). Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in southwestern China. Med. Sci. Monit . 26:e924609. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924609

Liu, A. N., Wang, L. L., Li, H. P., Gong, J., and Liu, X. H. (2017). Correlation between posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms based on Pearson correlation coefficient: a meta-analysis. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 205, 380–389. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000605

Liu, N., Zhang, F., Wei, C., Jia, Y., Shang, Z., Sun, L., et al. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res . 287:112921. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921

Maree, D. J. F., Maree, M., and Collins, C. (2008). The relationship between hope and goal achievement. J. Psychol. Afric . 18, 65–74. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2008.10820172

Mayer, C. H., and Vanderheiden, E. (2020). Contemporary positive psychology perspectives and future directions. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 32, 537–541. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1813091

Mayer, C. H., Vanderheiden, E., and Oosthuizen, R. M. (2019). Transforming shame, guilt and anxiety through a salutogenic PP1. 0 and PP2. 0 counselling framework. Counsell. Psychol. Q. 32, 436–452. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2019.1609421

Miconi, D., Li, Z. Y., Frounfelker, R. L., Santavicca, T., Cénat, J. M., Venkatesh, V., et al. (2020). Ethno-cultural disparities in mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study on the impact of exposure to the virus and COVID-19-related discrimination and stigma on mental health across ethno-cultural groups in Quebec (Canada). BJPsych Open 7:e14. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.146

Moorey, S., and Greer, S. (1989). Psychological Therapy for Patients with Cancer: A New Approach . London: Heneman.

Nilsson, K. W., Leppert, J., Simonsson, B., and Starrin, B. (2010). Sense of coherence and psychological well-being: improvement with age. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 64, 347–352. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.081174

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2001). “Ruminative coping and adjustment to bereavement,” in Handbook of Bereavement Research: Consequences, Coping, and Care , eds M. S. Stroebe, R. O. Hansson, W. Stroebe, and H. Schut (New York, NY: American Psychological Association), 545–562. doi: 10.1037/10436-023

Okun, B. S., and Friedlander, D. (2005). Educational stratification among Arabs and Jews in Israel: historical disadvantage, discrimination, and opportunity. Populat. Stud. 59, 163–180. doi: 10.1080/00324720500099405

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., and Perez, L. M. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the rcope. J. Clin. Psychol. 56, 519–543. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200004)56:4andlt;519::AID-JCLP6andgt;3.0.CO;2-1

Patel, J. A., Nielsen, F. B. H., Badiani, A. A., Assi, S., Unadkat, V. A., Patel, B., et al. (2020). Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Public Health 183:110. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006

Pinson, H. (2007). At the boundaries of citizenship: Palestinian Israeli citizens and the civic education curriculum. Oxford Rev. Educ. 33, 331–348. doi: 10.1080/03054980701366256

Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., Xie, B., and Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatr . 33:e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213

Roothman, B., Kirsten, D., and Wissing, M. (2003). Gender differences in aspects of psychological well-being. S. Afric. J. Psychol . 33, 212–218. doi: 10.1177/008124630303300403

Rossi, R., Socci, V., Talevi, D., Mensi, S., Niolu, C., Pacitti, F., et al. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Front. Psychiatry 11:790. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790

Ruiz-Frutos, C., Ortega-Moreno, M., Allande-Cussó, R., Ayuso-Murillo, D., Domínguez-Salas, S., and Gómez-Salgado, J. (2020). Sense of coherence, engagement, and work environment as precursors of psychological distress among non-health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Saf. Sci. 133:105033. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.105033

Sagy, S., and Braun-Lewensohn, O. (2009). Adolescents under rocket fire: when are coping resources significant in reducing emotional distress? Glob. Health Promot . 16, 5–15. doi: 10.1177/1757975909348125

Sagy, S., Orr, E., Bar-On, D., and Awwad, E. (2001). Individualism and collectivism in two conflicted societies: comparing Israeli-Jewish and Palestinian-Arab high school students. Youth Soc . 33, 3–20. doi: 10.1177/0044118X01033001001

Sawatzky, R., Gadermann, A., and Pesut, B. (2009). An investigation of the relationships between spirituality, health status and quality of life in adolescents. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 4, 5–22. doi: 10.1007/s11482-009-9065-y

Schäfer, S., Sopp, R., Schanz, C., Staginnus, M., Göritz, A. S., and Michael, T. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on public mental health and the buffering effect of sense of coherence. Psychother. Psychosom. 89, 1–7. doi: 10.1159/000510752

Sfendla, A., and Hadrya, F. (2020). Factors associated with psychological distress and physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Secur . 18, 444–453. doi: 10.1089/hs.2020.0062

Sharabi, A., Levi, U., and Margalit, M. (2012). Children's loneliness, sense of coherence, family climate, and hope: developmental risk and protective factors. J. Psychol . 146, 61–83. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.568987

Snyder, C. R. (1994). “Hope and optimism,” in Encyclopedia Human Behavior, Vol. 2 (San Diago, CA: Academic Press), 535–542.

Snyder, C. R. (2000). “Hypothesis: there is hope,” in Handbook of Hope: Theory, Measures, and Applications , ed C. R. Snyder (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 3–21. doi: 10.1016/B978-012654050-5/50003-8

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: rainbows in the mind. Psychol. Inquir . 13, 249–275. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01

Spoorthy, M. S., Pratapa, S. K., and Mahant, S. (2020). Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic–a review. Asian J. Psychiatr. 51:102119. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119

Strang, S., and Strang, P. (2001). Spiritual thoughts, coping and “sense of coherence” in brain tumour patients and their spouses. Palliat. Med . 15, 127–134. doi: 10.1191/026921601670322085

Tchernichovsky, D., and Sharoni, C. (2015). “The connection between social capital and health among the ultra-Orthodox,” in State of the Nation Report , eds Tchernichovsky and Weiss (Jerusalem: Taub Institute), 383–409 (Hebrew).

The Galilee Society-The Arab National Society for Health Research Services (2013). Annual Report . Available online at: http://www.gal-soc.org/files/userfiles/GS_annual%20report_2013.pdf (accessed January 25 2017).

Trzebiński, J., Cabański, M., and Czarnecka, J. Z. (2020). Reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic: the influence of meaning in life, life satisfaction, and assumptions on world orderliness and positivity. J. Loss Trauma 25, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2020.1765098

Van Schalkwyk, L., and Rothmann, S. (2008). The validation of the orientation to life questionnaire in a chemical factory. S. Afric. J. Industr. Psychol . 34, 31–39. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v34i2.725

Volanen, S. M., Lahelma, E., Silventoinen, K., and Suominen, S. (2004). Factors contributing to sense of coherence among men and women. Eur. J. Public Health 14, 322–330. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.3.322

Walsh, F. (2020). Loss and resilience in the time of COVID-19: meaning making, hope, and transcendence. Fam. Process 59, 898–911. doi: 10.1111/famp.12588

Wong, P. T. (2016). Self-transcendence: a paradoxical way to become your best. Int. J. Existent. Posit. Psychol . 6:9.

Wong, P. T. (2020a). Existential positive psychology and integrative meaning therapy. Int. Rev. Psychiatr . 32, 565–578. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1814703

Wong, P. T. P. (2019). “Foreword: from shame to wholeness: an existential positive psychology perspective,” in The Bright Side of Shame: Transforming and Growing Through Practical Applications in Cultural Contexts , eds C.-H. Mayer, and E. Vanderheiden (Cham: Springer). Available online at: http://www.drpaulwong.com/from-shame-to-wholeness-an-existential-positive-psychology-perspective/ (accessed December 1, 2020).

Wong, P. T. P. (2020b). The maturing of positive psychology and the emerging PP 2.0: A book review of Positive Psychology (3rd ed.) by William Compton and Edward Hoffman. Int. J. Wellbeing 10, 107–117. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v10i1.885

Yiftachel, O. (2009). “Ghetto citizenship: Palestinian Arabs in Israel,” in Israel and the Palestinians–Key Terms , eds N. Rouhana, and A. Sabagh (Haifa, IL: Mada Center for Applied Research), 56–60.

Yildirim, M., and Arslan, G. (2020). Exploring the associations between resilience, dispositional hope, preventive behaviours, subjective well-being, and psychological health among adults during early stage of COVID-19. Curr. Psychol. 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01177-2

Keywords: hope, sense of coherence, resilience, stress, pandemic, ethnic groups