Polymyalgia rheumatica as the first presentation of metastatic lymphoma

Affiliation.

- 1 Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. [email protected]

- PMID: 20686306

- DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3400

A 48-year-old HIV-positive woman presented with progressive pain and stiffness of both shoulders and hips. She was given the diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) due to high erythrocyte sedimentation rate. However, a 1-week course of prednisolone failed to improve her symptoms. She later discovered a breast lump of which histopathological tissue was consistent with a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Whole body bone scan revealed multiple bony metastases. The presence of atypical features of PMR and lack of dramatic response to steroids should prompt physicians to raise the probability of differential diagnoses other than PMR, and in particular, malignancy.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Antineoplastic Agents / therapeutic use

- Diagnosis, Differential

- HIV Infections / complications

- HIV Infections / diagnosis

- HIV Infections / drug therapy

- Lymphoma, B-Cell / complications

- Lymphoma, B-Cell / diagnosis*

- Lymphoma, B-Cell / drug therapy

- Middle Aged

- Polymyalgia Rheumatica / complications

- Polymyalgia Rheumatica / diagnosis*

- Polymyalgia Rheumatica / drug therapy

- Antineoplastic Agents

- Hodgkin's

- Non-hodgkin's

- Surviving Lymphoma

What is Metastatic Cancer?

By: anonymous (not verified) | july 19, 2011.

The term 'metastatic lymphoma' does not refer to a diagnosis. Unlike many of the subtypes of lymphoma we have featured in these articles, metastatic lymphoma is not one of them. While it is possible for a person's lymphoma to metastasize, or spread to distant sites of the body compared to where it began, it is not very common to discuss advanced lymphomas in terms of metastasis.

Metastatic Cancer Explained

When we discuss cancer, we normally do so according to anatomy breast cancer, lung cancer, kidney cancer, etc. If it is determined that, for example, a case of cancer began in the lungs, then the lungs would be considered the primary site of that cancer, meaning the site of the cancer's origin.

If it is later determined that the lung cancer is not merely confined to the lung, but has in fact spread to local sites (in this case, perhaps somewhere in the chest) as well as distant sites, then it would be considered a case of metastatic lung cancer.

While some metastatic cancers can be treated, most often when a cancer has metastasized well beyond its primary origin, it is not treatable and is often fatal. In fact, when we read of people dying from cancer, it is because their cancer has metastasized.

Metastatic Lymphoma

Simply because the term is not often used in lymphomas does not mean that lymphomas cannot metastasize. They can and often do spread to distant sites in the body if not controlled or caught early. However, when other cancers metastasize it normally means the cancer has formed a new secondary tumor in a new site. Since solid tumors aren't really an aspect of lymphoma and they are certainly not an aspect of leukemia, the notion of metastatic lymphoma becomes a little more complicated.

That said, on the rare occasion of metastatic lymphoma and that a lymphoma forms a distant tumor in the body, that tumor is most often found in the lungs, spleen, or the central nervous system.

Sources: Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health Photo: Pixabay

More Articles

December 21, 2023.

Amazon.com is pleased to have the Lymphoma Information Network in the family of Amazon.com associates. We've agreed to ship items...

The question ought to be what are myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), since this is a group of similar blood and bone marrow diseases that...

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC) is a very rare and aggressive skin cancer that usually develops when a person is in his or her 70s. It is...

Radiation Therapy Topics

At some point, the Seattle biotech company Cell Therapeutics Inc (CTI) should earn an entry in the Guinness Book of World Records for utter and...

Site Beginnings

This site was started as Lymphoma Resource Page(s) in 1994. The site was designed to collect lymphoma...

Three papers appearing in the journal Blood and pointing towards a regulator-suppressor pill could offer hope to blood cancer...

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted a third so-called Breakthrough Therapy Designation for the investigational oral...

The US Food and Drug Administration today has approved an expanded use of Imbruvica (ibrutinib) in patients with...

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has announced that it has granted "Breakthrough Therapy Designation" for the investigational agent...

According to a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team from the University of California, San...

Pharmacyclics has announced that the company has submitted a New Drug Application (NDA) to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for...

New research suggests that frontline radioimmunotherapy ...

Gilead Sciences has announced results of the company's Phase II study of its investigational compound idelalisib, an oral inhibitor of...

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

Bone metastases represent a prominent source of morbidity [ 2,3 ]. Skeletal-related events (SREs) that are due to bone metastases can include pain, pathologic fracture, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord compression. Across a wide variety of tumors involving bone, the frequency of SREs can be reduced through the use of osteoclast inhibitors, such as bisphosphonates or denosumab. (See "Overview of cancer pain syndromes", section on 'Multifocal bone pain' and "Clinical presentation and evaluation of complete and impending pathologic fractures in patients with metastatic bone disease, multiple myeloma, and lymphoma" and "Hypercalcemia of malignancy: Mechanisms", section on 'Osteolytic metastases' and "Clinical features and diagnosis of neoplastic epidural spinal cord compression" and "Osteoclast inhibitors for patients with bone metastases from breast, prostate, and other solid tumors" and "Multiple myeloma: The use of osteoclast inhibitors" .)

The incidence, distribution, clinical presentation, and diagnosis of adult patients with bone metastases is presented here. An overview of therapeutic options is provided separately, as are most detailed discussions of the mechanisms of bone metastases. Specific issues related to bone metastases in patients with prostate cancer, multiple myeloma, and primary lymphoma of bone (PLB) are discussed separately.

● (See "Overview of therapeutic approaches for adult patients with bone metastasis from solid tumors" .)

● (See "Mechanisms of bone metastases" .)

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Hodgkin's lymphoma (Hodgkin's disease)

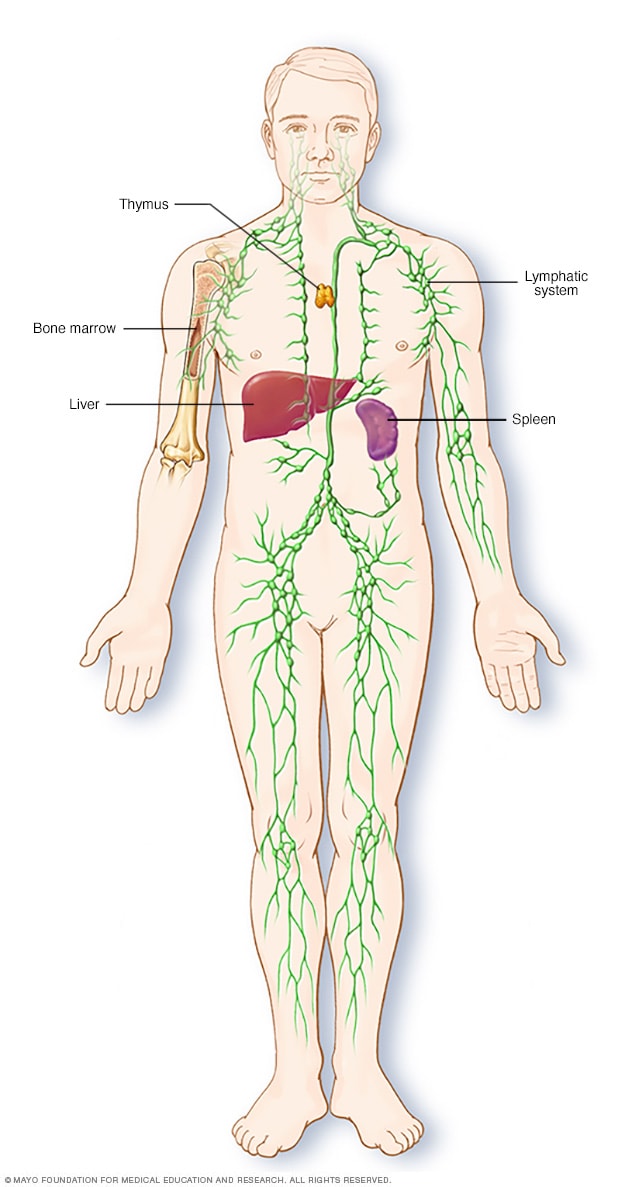

Parts of the immune system

The lymphatic system is part of the body's immune system, which protects against infection and disease. The lymphatic system includes the spleen, thymus, lymph nodes and lymph channels, as well as the tonsils and adenoids.

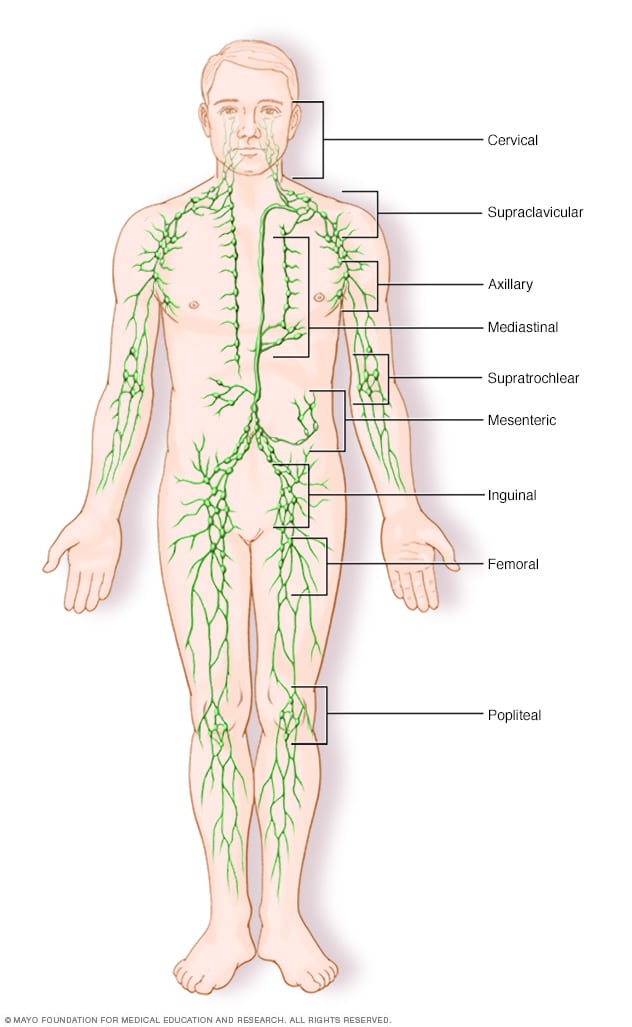

Lymph node clusters

Lymph nodes are bean-sized collections of cells called lymphocytes. Hundreds of these nodes cluster throughout the lymphatic system, for example, near the knee, groin, neck and armpits. The nodes are connected by a network of lymphatic vessels.

Hodgkin's lymphoma is a type of cancer that affects the lymphatic system, which is part of the body's germ-fighting immune system. In Hodgkin's lymphoma, white blood cells called lymphocytes grow out of control, causing swollen lymph nodes and growths throughout the body.

Hodgkin's lymphoma, which used to be called Hodgkin's disease, is one of two general categories of lymphoma. The other is non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Advances in diagnosis and treatment of Hodgkin's lymphoma have helped give people with this disease the chance for a full recovery. The prognosis continues to improve for people with Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Products & Services

- A Book: Living Medicine

- Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

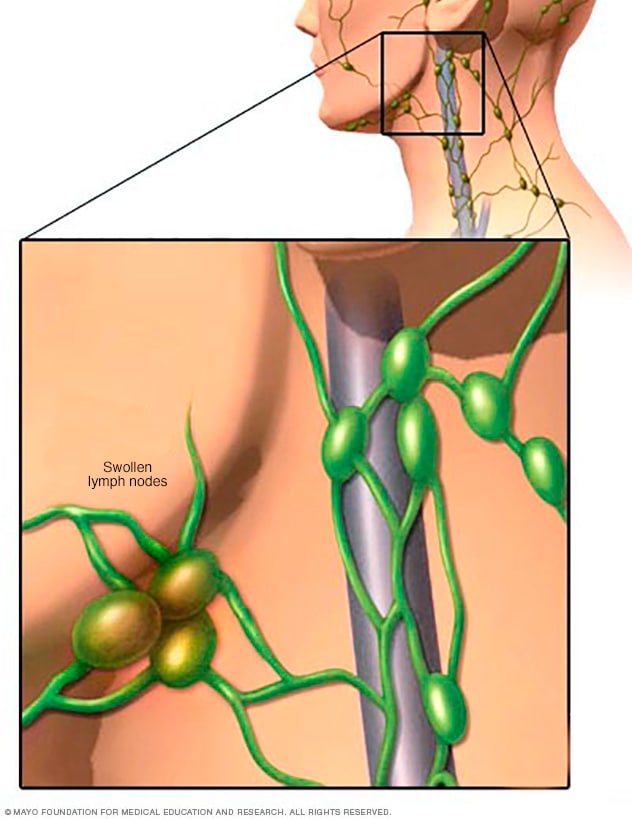

Swollen lymph nodes

One of the most common places to find swollen lymph nodes is in the neck. The inset shows three swollen lymph nodes below the lower jaw.

Signs and symptoms of Hodgkin's lymphoma may include:

- Painless swelling of lymph nodes in your neck, armpits or groin

- Persistent fatigue

- Night sweats

- Losing weight without trying

- Severe itching

- Pain in your lymph nodes after drinking alcohol

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your health care provider if you have any persistent signs or symptoms that worry you.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

Get Mayo Clinic cancer expertise delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe for free and receive an in-depth guide to coping with cancer, plus helpful information on how to get a second opinion. You can unsubscribe at any time. Click here for an email preview.

Error Select a topic

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing

Your in-depth coping with cancer guide will be in your inbox shortly. You will also receive emails from Mayo Clinic on the latest about cancer news, research, and care.

If you don’t receive our email within 5 minutes, check your SPAM folder, then contact us at [email protected] .

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Doctors aren't sure what causes Hodgkin's lymphoma. They know that it begins when infection-fighting white blood cells called lymphocytes develop changes in their DNA. A cell's DNA contains the instructions that tell a cell what to do.

The DNA changes tell the cells to multiply rapidly and to continue living when other cells would naturally die. The lymphoma cells attract many healthy immune system cells to protect them and help them grow. The extra cells crowd into the lymph nodes and cause swelling and other Hodgkin's lymphoma signs and symptoms.

There are multiple types of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Your type is based on the characteristics of the cells involved in your disease and their behavior. The type of lymphoma you have helps determines your treatment options.

Classical Hodgkin's lymphoma

Classical Hodgkin's lymphoma is the more common type of this disease. People diagnosed with this type have large lymphoma cells called Reed-Sternberg cells in their lymph nodes.

Subtypes of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma include:

- Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin's lymphoma

- Mixed cellularity Hodgkin's lymphoma

- Lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin's lymphoma

- Lymphocyte-rich Hodgkin's lymphoma

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma

This much rarer type of Hodgkin's lymphoma involves lymphoma cells that are sometimes called popcorn cells because of their appearance. Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma is usually diagnosed at an early stage and may require less intensive treatments compared to the classical type of the disease.

Risk factors

Factors that can increase the risk of Hodgkin's lymphoma include:

- Your age. Hodgkin's lymphoma is most often diagnosed in people in their 20s and 30s and those over age 55.

- A family history of lymphoma. Having a blood relative with Hodgkin's lymphoma increases your risk of developing Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- Being male. People who are assigned male at birth are slightly more likely to develop Hodgkin's lymphoma than are those who are assigned female.

- Past Epstein-Barr infection. People who have had illnesses caused by the Epstein-Barr virus, such as infectious mononucleosis, are more likely to develop Hodgkin's lymphoma than are people who haven't had Epstein-Barr infections.

- HIV infection. People who are infected with HIV have an increased risk of Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Hodgkin's lymphoma (Hodgkin's disease) care at Mayo Clinic

Living with hodgkin's lymphoma (hodgkin's disease)?

Connect with others like you for support and answers to your questions in the Adolescent & Young Adult (AYA) Cancer support group on Mayo Clinic Connect, a patient community.

Adolescent & Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Discussions

3 Replies Sun, Feb 25, 2024

20 Replies Sat, Feb 24, 2024

2 Replies Mon, Feb 12, 2024

- Hodgkin lymphoma. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1439. Nov. 15, 2021.

- Adult Hodgkin lymphoma treatment (PDQ) — patient version. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/patient/adult-hodgkin-treatment-pdq. Accessed Nov. 15, 2021.

- AskMayoExpert. Classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2021.

- Aster JC, et al. Pathogenesis of Hodgkin lymphoma. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Dec. 1, 2021.

- Hoffman R, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma: Clinical manifestations, staging and therapy. In: Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2018. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Nov. 25, 2021.

- Ansell SM. Hodgkin lymphoma: A 2020 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification and management. American Journal of Hematology. 2020; doi:10.1002/ajh.25856.

- Side effects of chemotherapy. Cancer.Net. https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/how-cancer-treated/chemotherapy/side-effects-chemotherapy. Accessed Dec. 1, 2021.

- Side effects of radiation therapy. Cancer.Net. https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/how-cancer-treated/radiation-therapy/side-effects-radiation-therapy. Accessed Dec. 1, 2021.

- Side effects of a bone marrow transplant (stem cell transplant). Cancer.Net. https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/how-cancer-treated/bone-marrowstem-cell-transplantation/side-effects-bone-marrow-transplant-stem-cell-transplant. Accessed Dec. 1, 2021.

- Distress management. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=3&id=1431. Nov. 15, 2021.

- Lymphoma SPOREs. National Cancer Institute. https://trp.cancer.gov/spores/lymphoma.htm. Accessed Nov. 15, 2021.

- Laurent C, et al. Impact of expert pathologic review of lymphoma diagnosis: Study of patients from the French Lymphopath Network. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017; doi:10.1200/JCO. 2016.71.2083 .

- Braswell-Pickering BA. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. Nov. 3, 2021.

- Goyal G, et al. Association between facility volume and mortality of patients with classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2020; doi:10.1002/cncr.32584.

- Member institutions. Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. https://www.allianceforclinicaltrialsinoncology.org/main/public/standard.xhtml?path=%2FPublic%2FInstitutions. Accessed Dec. 7, 2021.

- NRG Oncology list of main member, LAPS and NCORP sites. NRG Oncology. https://www.nrgoncology.org/About-Us/Membership/Member-Institution-Lists. Accessed Dec. 7, 2021.

- Hodgkin's vs. non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: What's the difference?

Associated Procedures

- Bone marrow biopsy

- Bone marrow transplant

- Chemotherapy

- Positron emission tomography scan

- Radiation therapy

News from Mayo Clinic

- Brentuximab vedotin may improve overall survival in patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma July 14, 2022, 04:22 p.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Pathologic Assessment of Lymph Node Metastasis

- First Online: 25 June 2022

Cite this chapter

- James Isom 4 &

- Jane L. Messina 4 , 5 , 6

991 Accesses

The pathologic assessment and evaluation of lymph node status plays a central role in the diagnosis, staging, and management of most malignancies. The pathologic status of the lymph node plays a central role in the staging, and thus subsequent treatment of diseases, which is codified in the AJCC/UICC staging system. Lymph node metastasis may be subclinical and detected microscopically during surgical resection of a sentinel node or regional lymphadenectomy for initial therapy, or it may present clinically as the first manifestation of a metastatic malignancy. Different protocols exist for the pathologic evaluation of lymph nodes in these distinct settings. These involve systematic gross assessment, careful light microscopic evaluation, judicious and sometimes stepwise application of immunohistochemical methods, and accurate pathologic reporting. The evaluation of a lymph node metastasis in a patient with unknown primary malignancy requires knowledge of the relative frequencies of malignancies, their most common sites of presentation, and an algorithmic approach to immunohistochemical testing. Molecular analysis by gene expression profiling offers modest improvement in diagnostic accuracy, but these improvements have not yet been translated into clinical improvements.

- Unknown primary

- Nodal assessment

- Nodal staging

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Urteaga O, Pack GT. On the antiquity of melanoma. Cancer. 1966;19(5):607–10.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gorantla VC, Kirkwood JM. State of melanoma: an historic overview of a field in transition. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014;28(3):415–35.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cooper S. The first lines of the theory and practice of surgery. London: Longman; 1840.

Google Scholar

Snow HM. Melanoma cancerous disease. Lancet. 1892;140:869–922.

Article Google Scholar

Faries MB, et al. Lymph node metastasis in melanoma: a debate on the significance of nodal metastases, conditional survival analysis and clinical trials. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2018;35(5–6):431–42.

Denoix P. Nomenclature classification des cancers. Bull Inst Nat Hyg (Paris). 1952;7:743–8.

Hutter RV. At last—worldwide agreement on the staging of cancer. Arch Surg. 1987;122(11):1235–9.

Amin MB. AJCC cancer staging manual. 8th ed. Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2017.

Book Google Scholar

Surgery basic science and clinical evidence. 2nd ed. Springer Nature; 2008.

Cabanas RM. An approach for the treatment of penile carcinoma. Cancer. 1977;39(2):456–66.

Morton DL, et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992;127(4):392–9.

Fayne RA, et al. Evolving management of positive regional lymph nodes in melanoma: past, present and future directions. Oncol Rev. 2019;13(2):433.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zeitoun J, Babin G, Lebrun JF. Sentinel node and breast cancer: a state-of-the-art in 2019. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2019;47(6):522–6.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Faries MB. Application of senitnel lymph node surgery outside of melanoma and breast cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2021;

Burghgraef TA, et al. In vivo sentinel lymph node identification using fluorescent tracer imaging in colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;158:103,149.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Vuijk FA, et al. Fluorescent-guided surgery for sentinel lymph node detection in gastric cancer and carcinoembryonic antigen targeted fluorescent-guided surgery in colorectal and pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2018;118(2):315–23.

Cancer Protocol Templates. 2021 [cited 2021; Available from: https://www.cap.org/protocols-and-guidelines/cancer-reporting-tools/cancer-protocol-templates .

Narayanan R, Wilson TG. Sentinel node evaluation in prostate cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2018;35(5–6):471–85.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cotarelo CL, et al. Improved detection of sentinel lymph node metastases allows reliable intraoperative identification of patients with extended axillary lymph node involvement in early breast cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2021;38(1):61–72.

Osarogiagbon RU, et al. Survival implications of variation in the thoroughness of pathologic lymph node examination in American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0030 (Alliance). Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102(2):363–9.

Gleisner AL, et al. Nodal status, number of lymph nodes examined, and lymph node ratio: what defines prognosis after resection of colon adenocarcinoma? J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(6):1090–100.

Wright JL, Lin DW, Porter MP. The association between extent of lymphadenectomy and survival among patients with lymph node metastases undergoing radical cystectomy. Cancer. 2008;112(11):2401–8.

Chan JK, et al. Metastatic gynecologic malignancies: advances in treatment and management. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2018;35(5–6):521–33.

Mansour J, et al. Prognostic value of lymph node ratio in metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2018;132(1):8–13.

Mozzillo N, et al. Sentinel node biopsy in thin and thick melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(8):2780–6.

Leong SP, et al. Clinical patterns of metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25(2):221–32.

Hemminki K, et al. Site-specific cancer deaths in cancer of unknown primary diagnosed with lymph node metastasis may reveal hidden primaries. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(4):944–50.

Kawaguchi T. Pathological features of lymph node metastasis. 2 from morphological aspects. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2001;102(6):440–4.

Zhou H, Lei PJ, Padera TP. Progression of metastasis through lymphatic system. Cell. 2021;10(3)

Cote RJ, et al. Role of immunohistochemical detection of lymph-node metastases in management of breast cancer. International Breast Cancer Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354(9182):896–900.

Messina JL, et al. Pathologic examination of the sentinel lymph node in malignant melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(6):686–90.

Euscher ED, et al. Ultrastaging improves detection of metastases in sentinel lymph nodes of uterine cervix squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(9):1336–43.

Su LD, et al. Immunostaining for cytokeratin 20 improves detection of micrometastatic Merkel cell carcinoma in sentinel lymph nodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(5):661–6.

Abdel-Halim CN, et al. Histopathological definitions of extranodal extension: a systematic review. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15(2):599–607.

Dekker J, Duncan LM. Lack of standards for the detection of melanoma in sentinel lymph nodes: a survey and recommendations. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137(11):1603–9.

Cole CM, Ferringer T. Histopathologic evaluation of the sentinel lymph node for malignant melanoma: the unstandardized process. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(1):80–7.

Bautista NC, Cohen S, Anders KH. Benign melanocytic nevus cells in axillary lymph nodes. A prospective incidence and immunohistochemical study with literature review. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102(1):102–8.

Carson KF, et al. Nodal nevi and cutaneous melanomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20(7):834–40.

Biddle DA, et al. Intraparenchymal nevus cell aggregates in lymph nodes: a possible diagnostic pitfall with malignant melanoma and carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(5):673–81.

Koh SS, Cassarino DS. Immunohistochemical expression of p16 in melanocytic lesions: an updated review and meta-analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(7):815–28.

Lezcano C, et al. Immunohistochemistry for PRAME in the distinction of nodal nevi from metastatic melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44(4):503–8.

Kamposioras K, et al. Malignant melanoma of unknown primary site. To make the long story short. A systematic review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;78(2):112–26.

Lester S et al. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with invasive carcinoma of the breast; December 2013.

Lyman GH, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(13):1365–83.

Wiatrek R, Kruper L. Sentinel lymph node biopsy indications and controversies in breast cancer. Maturitas. 2011;69(1):7–10.

Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33.

Buttar A, et al. Cancers of unknown primary. In: Pieters R, editor. Cancer concepts: a guidebook for the non-oncologist. University of Massachusetts Medical School; 2015.

Hemminki K, et al. Survival in cancer of unknown primary site: population-based analysis by site and histology. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(7):1854–63.

Losa F, et al. 2018 consensus statement by the Spanish Society of Pathology and the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology on the diagnosis and treatment of cancer of unknown primary. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(11):1361–72.

Chorost MI, et al. Unknown primary. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87(4):191–203.

Hainsworth JD, Fizazi K. Treatment for patients with unknown primary cancer and favorable prognostic factors. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(1):44–51.

Jereczek-Fossa BA, Jassem J, Orecchia R. Cervical lymph node metastases of squamous cell carcinoma from an unknown primary. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30(2):153–64.

Kandalaft PL, Gown AM. Practical applications in immunohistochemistry: carcinomas of unknown primary site. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(6):508–23.

Pentheroudakis G, Golfinopoulos V, Pavlidis N. Switching benchmarks in cancer of unknown primary: from autopsy to microarray. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(14):2026–36.

Binder C, et al. Cancer of unknown primary-epidemiological trends and relevance of comprehensive genomic profiling. Cancer Med. 2018;7(9):4814–24.

Ettinger DS, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines Occult primary. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2011;9(12):1358–95.

Bochtler T, Löffler H, Krämer A. Diagnosis and management of metastatic neoplasms with unknown primary. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2018;35(3):199–206.

Bellizzi AM. An algorithmic Immunohistochemical approach to define tumor type and assign site of origin. Adv Anat Pathol. 2020;27(3):114–63.

Houston KA, et al. Patterns in lung cancer incidence rates and trends by histologic type in the United States, 2004-2009. Lung Cancer. 2014;86(1):22–8.

Banerjee SS, Harris M. Morphological and immunophenotypic variations in malignant melanoma. Histopathology. 2000;36(5):387–402.

Pavlidis N. Cancer of unknown primary: biological and clinical characteristics. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(Suppl 3)):11–8.

Lee MS, Sanoff HK. Cancer of unknown primary. BMJ. 2020;371:m4050.

Weiss LM, et al. Blinded comparator study of immunohistochemical analysis versus a 92-gene cancer classifier in the diagnosis of the primary site in metastatic tumors. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15(2):263–9.

Handorf CR, et al. A multicenter study directly comparing the diagnostic accuracy of gene expression profiling and immunohistochemistry for primary site identification in metastatic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(7):1067–75.

Hainsworth JD, et al. Molecular gene expression profiling to predict the tissue of origin and direct site-specific therapy in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site: a prospective trial of the Sarah Cannon research institute. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(2):217–23.

Hayashi H, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing site-specific treatment based on gene expression profiling with carboplatin and paclitaxel for patients with cancer of unknown primary site. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(7):570–9.

Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet. 2012;379(9824):1428–35.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, FL, USA

James Isom & Jane L. Messina

Departments of Pathology and Cutaneous Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA

Jane L. Messina

Departments of Pathology and Cell Biology and Oncologic Sciences, University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, FL, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane L. Messina .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Surgery and Melanoma Center, California Pacific Medical Center and Research Institute, San Francisco, CA, USA

Stanley P. Leong

Henry Ford Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI, USA

S. David Nathanson

Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA

Jonathan S. Zager

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Isom, J., Messina, J.L. (2022). Pathologic Assessment of Lymph Node Metastasis. In: Leong, S.P., Nathanson, S.D., Zager, J.S. (eds) Cancer Metastasis Through the Lymphovascular System. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93084-4_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93084-4_6

Published : 25 June 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-93083-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-93084-4

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Create account

Intraocular Lymphoma

Primary intraocular lymphoma often poses a diagnostic dilemma with presentation like vitritis, intermediate uveitis or subretinal plaque-like lesions [1] . Diagnosis is often challenging in such cases, and this is why it is often one of the diseases referred to as a masquerade syndrome. [1] [2]

- 1.1 Etiology

- 1.3 Symptoms

- 1.4.1 Fluorescein Angiography

- 1.4.2 Optical coherence tomography

- 1.4.3 Fundus autofluorescence

- 1.4.4 Diagnostic vitrectomy

- 1.5 Systemic Evaluation

- 2.1.1 EBRT(External Beam Radiotherapy)

- 2.1.2.1 Methotrexate

- 2.1.2.2 Rituximab

- 2.1.3.1 Methotrexate

- 2.1.3.2 Rituximab

- 2.2 Prognosis

- 3 Additional Resources

- 4 References

Vitreoretinal lymphoma (as primary introacular lymphoma is now known) is the most common introacular lymphoproliferative disease. The term vitreoretinal lymphoma distinguishes it from other introcular lymphoproliferations including choroidal lymphomas (which do not have any association with central nervous system disease) and iris or ciliary body lymphomas. [3] The term intraocular lymphoma was first introduced more than 60 years ago. [4] [5] However, prior to the advent of immunohistochemistry, vitreoretinal lymphomas were known as reticulum cell sarcomas, microgliomas, perithelial sarcomas or lymphosarcomas. It is considered a variant of primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphomas and may occur only in the eye initially (thus a primary vitreoretinal lymphoma) or contemporaneously with CNS disease. Rarely, a vitreoretinal lymphoma can be classified as secondary when it arises due to metastasis from a systemic lymphoma. [2] [6]

The majority of vitreoretinal lymphomas are of a diffuse large B-cell (DLBCL) histologic subtype [3] [7] [8] , though occasionally T-cell lymphomas can occur. [9]

Vitreoretinal lymphomas represent < 1% of all intraocular tumors [10] , 4-6% of all intracranial tumors and 1-2% of all extra nodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. [11] Involvement of the CNS is common, developing in 35-90% along the course of the disease. Women are more commonly affected than men [10] and patients generally present in 4th to 6th decade [11] , although a case as young as 15 years has been reported [12] [13] . Eighty to ninety percent patients will have bilateral disease, although initial presentation may be unilateral or asymmetric. [11]

On examination , anterior segment is may exhibit anterior chamber cells as well as keratic precipitates in both the primary presentation as well as in recurrences. [14] [2] Confocal microscopy of such "keratic precipitates" has demonstrated features that recapitulate atypical large lymphocytes with large nuclei and minimal cytoplasm. [15] These cells can even layer and present as a hypopyon; in these situations, the eye is generally more quiet than it would be with a hypopyon from an infectious etiology.

The manifestation of the disease can be either as vitreous inflammation, subretinal lesions, or both. Vitreous opacities may be seen extending from posterior pole to periphery which may move on movement of the eye producing an image like aurora in the sky [2] caused due to the reactive inflammatory cells in vitreous.

Subretinal lesions may begin as small, yellow to white mounds, which enlarge and expand and further coalesce to produce large yellow sub retinal masses with brown pigmentation in the center known as leopard skin pigmentation. These lesions may become atrophic and shrink with treatment and the passage of time.

The lesions may involve optic disc producing an optic nerve head swelling. Vasculitis with retinal hemorrhages can also be seen. [16] [17] Sheathing of the vessels may be seen which could be reactive or due to lymphoma cells infiltration.

The patient usually presents with the complaints of blurring of vision, floaters, or a combination of both.

Clinical diagnosis

Vitreoretinal lymphoma can be challenging to diagnose due to its uncommon occurrence and the similarities it shares with other uveitic conditions. Diseases that should be considered on the differential diagnosis include chronic endophthalmitis, syphilis, tuberculosis, Behcet disease, birdshot chorioretinopathy, secondary intraocular lymphoma, primary uveal lymphoma, and birdshot chorioretinopathy. Patients may be initially be treated with topical or systemic corticosteroids under the presumption that their presentation represents a posterior uveitis. Because lymphomatous cells are responsive to steroids, the "uveitis" may improve, only to recur with decrease in the dose of steroids or discontinuation of therapy. A diagnostic and therapeutic vitrectomy may result without a diagnosis of a lymphomatous process, particularly when a patient is still using topical or systemic corticosteroids. A study from the National Eye Institute found that patients underwent a mean of 2.1 procedures prior to a diagnosis of vitreoretinal lympoma. Furthermore, they found an average of 13.9 months from onset of symptoms to a confirmed histopathological diagnosis. [18]

Fluorescein Angiography

Hypofluorescence may be seen due to blockage of dye by the tumor cells as well as granular hyperfluorescence and late staining due to damage to the retinal pigment epithelium. The contrast between hypo- and hyperfluorescence has been noted to be reminiscent of leopard spots, but is certainly not pathognomonic for the disease. A leopard spot pattern denoted by hypofluorescent round spots has been observed in 43% of cases. [19]

Optical coherence tomography

Granular subretinal lesions (between Bruch's membrane and the retinal pigment epithelium) can be seen when subretinal lesions exist. OCT can be used to monitor progression or regression of the lymphoma. [20]

Fundus autofluorescence

Many patterns of fundus autofluorescence exist in intraocular lymphoma. A study from the National Eye Institute found that granularity on FAF was associated with active lymphoma in 61% of their cases. [19]

Diagnostic vitrectomy

For diagnosis, the gold standard is cytopathologic inspection of ocular fluid or chorioretinal biopsies. Small gauge vitrectomy may help with the yield and it is important to obtain an undiluted specimen (0.5 - 1 ml) at a low cut rate.

The sample may then be evaluated for:

- Immunohistochemistry

- Directed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for gene rearrangements in immunoglobulin heavy chain genes or (if T-cell lymphoma is suspected) T-cell receptor genes [21]

- Directed PCR for mutation in the MYD88 gene involving codon L265P [22]

- Cytokine measurement

Even after taking the appropriate measures, this can still yield false negative results.

Cytological examination is the gold standard for diagnosis [23] which shows large atypical lymphoid cells with pleomorphic nuclei, scant basophilic cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli. However, Kimura et al showed that cytology was sufficient in only 48% of cases. [24] The reason for such low yields includes the fact that lymphomatous cells may necrose and be misinterpreted.

Directed PCR can also be performed to identify IgH gene rearrangements using FR2A, FR3A, and CDR3 primers [25] . While fine needle or laser capture microdissection is a technique that can help in procuring a relatively pure population of large, atypical lymphocytes, few ocular pathologists routinely perform such a procedure. Immunohistochemistry employing cell markers such as CD20 , CD3, CD79a, and PAX5 can help identify the cell type. Directed PCR for the MYD88 gene (codon L265P) can also be diagnostic of a DLBCL vitreoretinal lymphoma.

Cytokine evaluation assessing for interleukin (IL)-10 compared to IL-6 may also be considered as corroborating a suspicion of lymphoma. IL-10 is an immunosuppressive cytokine while IL-6 is an inflammatory cytokine; an elevated IL-10 /IL-6 ratio is suggestive of lymphoma, although there is a relatively lower diagnostic sensitivity with this test. [26] [27] [20] Aqueous levels of IL-10 are used by some to monitor for recurrence.

Systemic Evaluation

Gadolium enhanced MRI of the brain should be performed to evaluate for intracerebral disease. Care should be coordinated with a neuro-oncologist.

The treatment can be aimed as local therapy which can be radiotherapy to the eye or intracameral / intravitreal agents like (methotrexate and rituximab) or as systemic therapy which can be external beam radiotherapy or systemic chemotherapy.

Medical therapy

Ebrt(external beam radiotherapy).

In cases of bilaterality, EBRT is the most effective treatment [28] . A total dose of 30-40 Gy, divided in the fractions of 1.5 to 2 Gy is often used.The side effects associated are dermatitis, punctate keratopathy , cataract and radiation retinopathy. The 2-year overall and disease-free survival rates were reported to be 74% and 58% respectively. [29]

Local Chemotherapy

Methotrexate.

In unilateral cases, intravitreal methotrexate has been used in the dosage of 400 µg/0.1cc twice weekly for 4 weeks , followed by 1 weekly for 4 weeks, followed by 1 monthly for 12 months. It is used as a primary therapy as an alternative to radiotherapy or for cases of relapse. [30] The risks associated are conjunctival injection and keratopathy. Sometimes these can be very severe which warrants the use of alternatives. Clinical remission is achieved after mean of 6.4 +/- 3.4 injections [31]

Intravitreal rituximab which is a chimeric anti CD20 monoclonal antibody can be used in the dosage of 1mg /0.1 ml in cases which are unresponsive or cannot tolerate methotrexate. [32]

For isolated ocular lymphoma, local chemotherapy and or radiotherapy can be done. In cases of systemic involvement or CNS lymphoma, systemic chemotherapy with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) or rituximab-CHOP is done.

Other systemic agents that have been investigated include pomalidomide, stem cell transplantation, or ibrutinib, with or without local therapy. [33]

Systemic Chemotherapy

Intravenous high dose methotrexate is commonly used in patients with intraocular lymphoma that have CNS or systemic involvement. [34] [35]

In cases with CNS involvement, rituximab may be used in conjunction with high dose methotrexate. [35]

Currently there is no prophylactic method that completely prevents the onset of CNS lymphoma subsequent to vitreoretinal lymphoma. Patients with vitreoeretinal lymphoma must undergo careful and regular surveillance for development of CNS involvement. While the mortality rates vary widely in the literature, the 5-year overall survival rate of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma is less than 25%. In a multicenter study involving 7 different countries, the investigators found that local ocular therapy may help with the tumor control, but did not impact overall survival. In that particular study, the overall survival and median progression-free survival were reported to be 31 and 18 months, respectively. [36]

Additional Resources

- Boyd K. Eye Cancer . American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/eye-cancer-list . Accessed March 11, 2019.

- Boyd K, Vemulakonda GA. Eye Lymphoma . American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/eye-lymphoma-list . Accessed March 11, 2019.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Grange LK, Kouchouk A, Dalal MD, Vitale S, Nussenbla RB, Chan CC, et al. Neoplastic masquerade syndromes in patients with uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157:526‐31.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Biswas J, Majumdar PD .Uveitis: An Update .Goto H.Intraocular lymphoma.2016. 93-100

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Coupland SE, Damato B. Understanding intraocular lymphomas. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol . 2008;36:564-578.

- ↑ Cooper, E.L. & Riker, J.L. (1951) Malignant lymphoma of the uveal tract. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 34, 1153–1158.

- ↑ Qualman, S.J., Mendelsohn, G., Mann, R.B. & Green, W.R. (1983) Intraocular lymphomas. Natural history based on a clinicopathologic study of eight cases and review of the literature. Cancer, 52, 878–886.

- ↑ Salomão DR, Pulido JS, Johnston PB, Canal-Fontcuberta I, Feldman AL. Vitreoretinal presentation of secondary large B-cell lymphoma in patients with systemic lymphoma. JAMA Ophthalmo l . 2013;131(9):1151-1158

- ↑ Coupland SE, Chan CC, Smith J. Pathophysiology or retinal lymphoma. Ocul Immunol Inflamm . 2009;17:227-237

- ↑ Chan CC, Gonzales JA. Primary Intraocular Lymphoma. New Jersey, London, Singapore, Beinjing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Taipei: Worl Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.,2007:1-267

- ↑ Coupland SE, Anastasssiou G, Bornfeld N, Hummel M, Stein H. Primary intraocular lymphoma of T-cell type: Report of a case and review of the literature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2005;243:189-197

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bardenstein DS. Intraocular lymphoma. Cancer Control. 1998;5:317–325.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Freeman LN, Schachat AP, Knox DL, et al. Clinical features laboratory investigations, and survival in ocular reticulum sarcoma. Ophthalmology 1987;94: 1631-1639.

- ↑ Cohen IJ, Vogel R, Matz S, et al. Successful non-neurotoxic therapy (without radiation) of a multifocal primary brain lymphoma with a methotrexate, vincristine, and BCNU protocol (DEMOB). Cancer. 1986;57:6–11.

- ↑ Wilkins CS, Goduni L, Dedania VS, Modi YS, Johnson B, Mehta N, Weng CY. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenge. Retina. 2021 Jul 1;41(7):1570-1576. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002820. PMID: 32332425.

- ↑ Hoffman PM, McKelvie P, Hall AJ, Stawell RJ, Santamaria JD. Intraocular lymphoma: a series of 14 patients with clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes. Eye 2003;17:513-521

- ↑ Zhang P, Tian J, Gao L. Intraocular lymphoma masquerading as recurent iridocyclitis: findings based on in vivo confocal microscopy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2018;26(3):362-364

- ↑ Akpek EK, Ahmed I, Hochberg FH, Soheilian M, Dryja TP, Jakobiec FA, Foster CS. Intraocular-central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features, diagnosis and outcomes. Ophthalmol 1999;106(9):1805-1810

- ↑ Katoch D, Bansal R, Nijhawan R, Gupta A. Primary intraocular central nervous system lymphoma masquerading as diffuse retinal vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep 2013;1-4

- ↑ Dalal M, Casady M, Moriarty E, Faia L, Nussenblatt R, Chan CC, Sen HN. Diagnostic procedures in vitreoretinal lymphoma. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014 Aug;22(4):270-6.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Casady M, Faia L, Nazemzadeh M, Nussenblatt R, Chan CC, Sen HN. Fundus autofluorescence patterns in primary intraocular lymphoma. Retina. 2014 Feb;34(2):366-72.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Liu TY, Ibrahim M, Bittencourt M, et al. Retinal optical coherence tomography manifestations of intraocular lymphoma. J Ophthal Inflamm Infect 2012; 2: 215-218.

- ↑ Chan CC. Molecular pathology of primary intraocular lymphoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2003;101:269-286

- ↑ Pulido JS, Salomão DR, Frederick LA, Viswanatha DS. MyD-88 L265P mutations are present in some cases of vitreoretinal lymphoma. Retina 2015;35(4):624-627

- ↑ Chan CC, Sen HN. Current concepts in diagnosing and managing primary vitreoretinal (intraocular) lymphoma. Discov Med 2013;15:93‐100.

- ↑ Kimura K, Usui Y, Goto H, et al. Clinical features and diagnostic significance of the intraocular fluid of 217 patients with intraocular lymphoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2012; 56: 383-389.

- ↑ Wang Y, Shen D, Wang VM, Sen HN, Chan CC. Molecular biomarkers for the diagnosis of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Int J Mol Sci 2011;12:5684‐97.

- ↑ Buggage RR, Whitcup SM, Nussenblatt RB, Chan CC. Using interleukin 10 to interleukin 6 ratio to distinguish primary intraocular lymphoma and uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999;40:2462-2463

- ↑ Chan CC, Rubenstein JL, Coupland SE, et al. Primary vitreoretinal lympoma: A report from an international primary central nervous system lymphoma collaborative group symposium. The Oncologist. 2011;16: 1589-1599

- ↑ Berenbom A, Davila RM, Lin HS et al .Treatment outcomes for primary intra ocular lymphoma: implications for external beam radiotherapy. Eye 21: 1198-1201

- ↑ Isobe K, Ejima Y, Tokumaru S et al. Treatment of primary intraocular lymphoma with radiation therapy : a multi institutional survey in Japan . Leuk Lymphoma 47: 1800-1805

- ↑ De Smet MD, Vancs VS, Kohler D et al. Intravitreal chemotherapy for the treatment of recurrent intraocular lymphoma. Br J Ophthalmol 83: 448-451

- ↑ Frenkel S, Hendler K, Siegal T et al. Intravitreal methotrexate for treating vitreoretinal lymphoma: 10years of experience . Br J Ophthalmol 92: 383-388

- ↑ Kitzmann AS, Pulido JS, Mohney BG. Intraocular use of rituximab. Eye. 2007; 21: 1524-1527.

- ↑ Pulido, J.S., Johnston, P.B., Nowakowski, G.S. et al. The diagnosis and treatment of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: a review. Int J Retin Vitr 4, 18 (2018).

- ↑ Venkatesh R, Bavaharan B, Mahendradas P, Yadav NK. Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019 Feb 14;13:353-364.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Kalogeropoulos D, Vartholomatos G, Mitra A, Elaraoud I, Ch'ng SW, Zikou A, Papoudou-Bai A, Moschos MM, Kanavaros P, Kalogeropoulos C. Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2019 Jan-Mar;33(1):66-80.

- ↑ Grimm S.A., Pulido J.S., Jahnke K. Primary intraocular lymphoma: an International Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Collaborative Group report. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1851–1855.

- Oncology/Pathology

- Retina/Vitreous

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 01 April 2024

Multiple thrombi mimicking metastases in the right atrium of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma diagnosed by multimodal cardiac imaging: one case report

- Zhiqiang Hu 1 ,

- Shuai Yuan 1 &

- Yun Mou 1

Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery volume 19 , Article number: 165 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

72 Accesses

Metrics details

Right-side heart mass can be found incidentally on routine transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). Accurate diagnosis of cardiac mass often requires more than one imaging method. We present a mid-age woman with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who was found to have multiple right atrial masses mimicking metastases on routine TTE, which were finally diagnosed as thrombi by multimodal cardiac imaging.

Case presentation

A 52-year-old woman was diagnosed with primary mediastinal diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) almost six months prior. The TTE revealed multiple masses in the right atrium with normal cardiac function when she was being evaluated for the next chemotherapy. On arrival, she was hemodynamically stable and asymptomatic. Physical examination was no remarkable. Laboratory findings showed leukocytosis of 17,900 cells/mm3, hemoglobin of 7.5 mg/dL, and a normal D-dimer level. The suspicious diagnosis of right atrial metastasis was made by TEE. However, the diagnosis of right atrial thrombi was made by contrast CMR. Finally, the 18 F-FDG PET-CT demonstrated no metabolic activity in the right atrium, which further supported the diagnosis of thrombi. Eventually, the masses were removed by cardiopulmonary bypass thoracotomy because of a high risk of pulmonary embolism. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of thrombi.

Conclusions

This case highlights the importance of multimodality cardiac imaging in the appropriate diagnosis of a RA masses in patient of lymphoma. Diagnosis of RA masses can be made using multimodal cardiac imaging like TTE, TEE and CMR, even PET. Echocardiography is the most commonly used on multimodal imaging in cardiac thrombus. CMR has high specificity in differentiating a tumor from thrombus, while 18 F-FDG PET has good sensitivity to determine the nature of the masses.

Peer Review reports

Right-side heart thrombus can be found incidentally on routine TTE. Its early and accurate diagnosis is beneficial to clinical management. Accurate diagnosis of cardiac thrombus often requires more than one imaging method. Echocardiography is the most commonly used diagnostic method, and CMR is the gold standard for noninvasive diagnosis of cardiac thrombus. PET-CT has good sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of cardiac thrombus, and has become one of evaluation methods of cardiac thrombus [ 1 ]. We present a case of RA thrombi in a patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), in which diagnosis was confirmed with the aid of multimodal cardiac imaging.

A 52-year-old woman was diagnosed with primary mediastinal of differentiation CD20 (+), CD79a (+), Bcl-2 (+), Bcl-6 (partial+), MUM1 (partial+) diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) almost six months prior. She was found to have stage IV disease with diffuse involvement of the thymus, lymph nodes and bone marrow. A power-injectable port was inserted and five cycles of R-DAEPOCH chemotherapy (rituximab, etoposide, epirubicin, vindesine, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide) have performed. During chemotherapy cycles, the patients have no special discomfort symptoms. The transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed multiple masses in the right atrium with normal cardiac function when she was being evaluated for the next chemotherapy. She was then sent to the in-patient department for further evaluation.

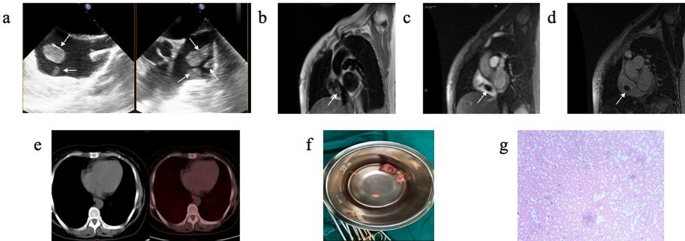

On arrival, she was hemodynamically stable and asymptomatic. Physical examination was no remarkable. Laboratory findings showed leukocytosis of 17,900 cells/mm3, hemoglobin of 7.5 mg/dL, and a normal D-dimer level. To further clarify the diagnosis, TEE showed multiple oval homogenous masses attached to the atrial wall with thin sticks, swinging with cardiac cycle, and no obvious thickening of the right atrial wall. (Fig. 1 a). Because there was a question of differentiating between metastatic lesions vs. thrombi, CMR was also obtained which showed isointense signal on black blood T2-weighted image (Fig. 1 b) with no enhancement of the RA masses on gadolinium contrast injection in early (Fig. 1 c) and delayed periods (Fig. 1 d), supporting the diagnosis of thrombi. In addition, PET-CT showed no abnormal elevated FDG metabolism in the right atrium (Fig. 1 e). The patient finally underwent surgical treatment because of high risk of pulmonary embolism. Multiple occupying lesions were visible in the right atrium (Fig. 1 f) during the surgery, and the histopathological confirmed that the right atrial masses were thrombi (Fig. 1 g).

( a ) TEE showed multiple oval homogenous masses attached to the atrial wall with thin sticks, swinging with cardiac cycle, and no obvious thickening of the right atrial wall. ( b ) CMR showed isointense signal on black blood T2-weighted imaging. ( c ) CMR gadolinium contrast injection showed no enhancement of the RA masses in early priod. ( d ) CMR gadolinium contrast injection showed no enhancement of the RA masses in delayed priod. ( e ) PET-CT showed no abnormal elevated FDG metabolism in the RA. ( f ) During the surgery, multiple occupying lesions were visible in the right atrium, varying in size and brittle as pearls. The largest one was about 3*2 cm in size, and no obvious abnormalities were observed in the tricuspid valve ring and right atrial wall. ( g ) The histopathological (200×) after surgery confirmed that the right atrial masses were thromboid tissue with calcium deposition

When a mass is found in the right atrium, it should be differentiated from cardiac or non-cardiac tumor. Among non-cardiac tumor, right atrium thrombus is the most common mass. Right atrium thrombus can be classified into “emboli in transit” and thrombus in situ, which was often associated with medical devices [ 2 ]. A thrombus in situ often appears smaller, less mobile, homogenous, and demonstrate no enhancement due to their avascularity after contrast injection.

Right atrium mass can be detected by TTE initially. However, there are several limitations, including operator dependence, a restricted field of view in TTE. When there is diagnostic doubt, TEE can provide some additional diagnostic information-but TEE is an invasive test. Furthermore, CT or CMR [ 3 ], and PET-CT [ 4 ] often become the methods for further differential examination. CMR imaging has become the gold standard techniques in the evaluation of cardiac masses, which can be used to evaluate the signal characteristics and morphological characteristics of cardiac mass, and help to determine the nature of mass lesions [ 5 ]. MR imaging characteristics can be used to predict the likely malignancy of a cardiac mass. Some studies have shown that the accuracy of MR in differentiating benign and malignant cardiac tumors may be more than 90% [ 3 , 6 ]. However, the sensitivity of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is insufficient, and PET just compensates for the sensitivity of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, while cardiac magnetic resonance imaging also compensates for its poor specificity. Therefore, some studies suggested combining both methods for a more accurate diagnosis of cardiac masses [ 7 ].

Unfortunately, there is no noninvasive imaging modality determining malignancy of cardiac tumors with sufficient accuracy. Therefore, more imaging methods are needed to complement each other to provide better treatment options for patients. The cardiac masses in the patient mentioned here were detected by a routine TTE during chemotherapy for lymphoma, which were firstly suspected the possibility of metastases because of a history of malignancy in this patient. In order to further understand the characteristics of the cardiac masses, TEE was performed for the patient, and the masses were found with regular shape and attached to the right atrial wall with high mobility, but the nature of the masses could not be determined. Furthermore, CMR and PET-CT showed no blood flow in the masses and no obvious abnormal FDG metabolism in the right atrium, and finally determined that the masses in the right atrial were thrombi.

This case highlights the importance of multimodality cardiac imaging in the appropriate diagnosis of a RA masses in patient of lymphoma. Diagnosis of RA masses can be made using multimodal cardiac imaging like TTE, TEE and CMR, even PET. Echocardiography is the most commonly used on multimodal imaging in cardiac thrombi. CMR has high specificity in differentiating a tumor from thrombi, while PET has good sensitivity to determine the nature of the masses.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

transthoracic echocardiography

cardiac magnetic resonance

positron emission tomography

fluorodeoxyglucose

non-Hodgkin lymphoma

right atrium

Rahbar K, et al. Differentiation of malignant and benign cardiac tumors using 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(6):856–63.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Goh FQ, et al. Clinical characteristics, treatment and long-term outcomes of patients with right-sided cardiac thrombus. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2022;68:1–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pazos-López P, et al. Value of CMR for the Differential diagnosis of Cardiac masses. JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(9):896–905.

PubMed Google Scholar

Rinuncini M, et al. Differentiation of cardiac thrombus from cardiac tumor combining cardiac MRI and 18F-FDG-PET/CT imaging. Int J Cardiol. 2016;212:94–6.

Motwani M, et al. MR imaging of cardiac tumors and masses: a review of methods and clinical applications. Radiology. 2013;268(1):26–43.

Hoffmann U, et al. Usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging of cardiac and paracardiac masses. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(7):890–5.

Mikail N, et al. Diagnosis and staging of cardiac masses: additional value of CMR with (18)F-FDG-PET compared to CMR with CECT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49(7):2232–41.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This work was supported by Zhejiang Province Educational Committee of China (Grant numbers: Y201839456), and Zhejiang Province Natural Science Foundation Committee of China (Grant numbers: LSD19H180002).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Echocardiography and Vascular Ultrasound Center, The First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, #79 Qingchun Road, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, 310003, P.R. China

Zhiqiang Hu, Shuai Yuan & Yun Mou

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ZQH conceived the study. SY drafted the manuscript and edited the images. YM contributed to the development of methodology. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yun Mou .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval, consent to participate.

Informed consent was obtained from patient included in the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent of clinical detail and image publication was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hu, Z., Yuan, S. & Mou, Y. Multiple thrombi mimicking metastases in the right atrium of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma diagnosed by multimodal cardiac imaging: one case report. J Cardiothorac Surg 19 , 165 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-024-02650-w

Download citation

Received : 21 September 2023

Accepted : 19 March 2024

Published : 01 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-024-02650-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Right atrium mass

- Multimodal cardiac imaging

Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery

ISSN: 1749-8090

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 31 May 2023

Metastasis from follicular lymphoma to an ovarian mature teratoma: a case report of tumor-to-tumor metastasis

- Yusuke Sato 1 ,

- Mitsutake Yano 1 ,

- Satoshi Eto 1 ,

- Kuniko Takano 2 &

- Kaei Nasu 1 , 3

Journal of Ovarian Research volume 16 , Article number: 106 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1038 Accesses

Metrics details

Tumor-to-tumor metastasis (TTM) is a rare but well-established phenomenon where histologically distinct tumors metastasize within each other. Here we report the first “known” case of follicular lymphoma that metastasized and extended to a mature ovarian teratoma.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old Japanese postmenopausal woman visited our hospital for a detailed examination of an ovarian tumor. Clinical imaging suggested it to be either teratoma-associated ovarian cancer with multiple lymph node metastases, or tumor-to-tumor metastasis from malignant lymphoma to ovarian teratoma. A bilateral adnexectomy and retroperitoneal lymph node biopsy were performed. Lined with squamous epithelium, the cyst constituted a mature ovarian teratoma, and the solid part showed diffuse proliferation of abnormal lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemically, the abnormal lymphoid cells were negative for CD5, MUM1, and CyclinD1, and positive for CD10, CD20, CD21, BCL2, and BCL6. Genetic analysis using G-banding and fluorescence in situ hybridization identified a translocation of t(14;18) (q32;q21), and we diagnosed tumor-to-tumor metastasis from nodal follicular lymphoma to mature ovarian teratoma. Twelve months after surgery, the patient showed no progression without adjuvant therapy.

Conclusions

The present case suggests that molecular approaches are useful in the diagnosis of TTM in mature ovarian teratomas when morphologic and immunohistochemical findings alone are insufficient for diagnoses.

Ovarian mature teratomas (OMTs), which are composed of cells derived from two or three germ cell layers, are among the most common benign ovarian tumors. Malignant transformation of OMTs causes various cancers, such as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma, neural tumor, malignant melanoma, and lymphoma [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. The ovaries can also receive cancer metastasis from other organs [ 4 ]. Therefore, when cancers are found in OMTs, it is difficult to determine whether they are due to malignant transformation (primary) or metastasis.

Tumor-to-tumor metastasis (TTM) is a rare but well-established phenomenon defined as metastasis in histologically distinct tumors [ 5 ]. To date, three cases of TTM to OMTs have been reported: appendiceal adenocarcinoma [ 5 ], cervical adenocarcinoma [ 6 ], and breast cancer [ 3 ]. Ten cases of primary lymphoma derived from OMTs [ 7 , 8 ] and only one cases of lymphoma-led invasions into OMTs are reported [ 9 ]. Here, we report a case of coexisting ovarian maturing teratoma and follicular lymphoma, diagnosed as TTM, using morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular approaches.

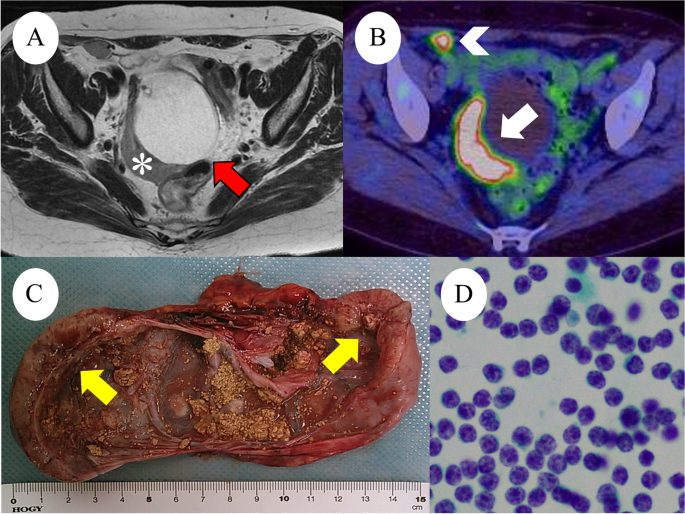

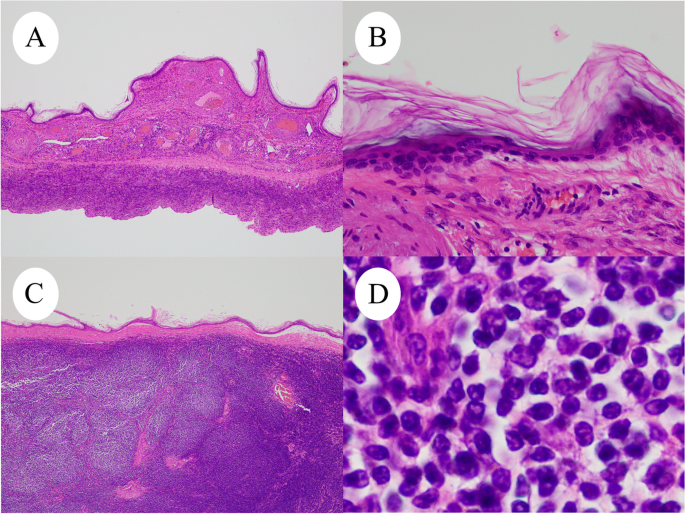

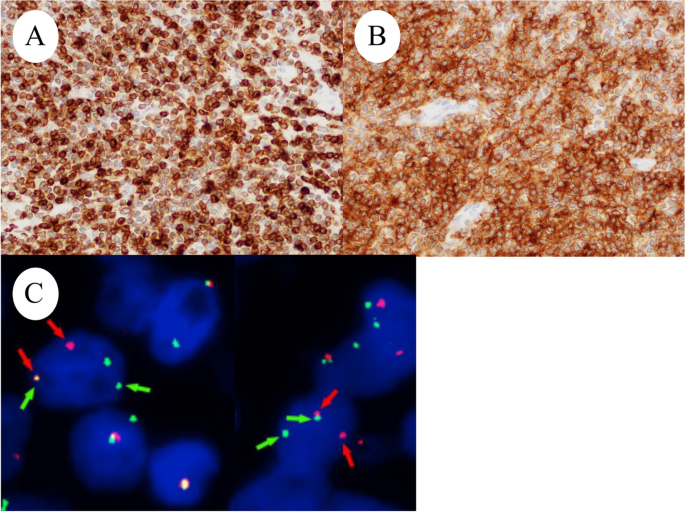

A 59-year-old Japanese postmenopausal woman (gravida 2, para 2) with no history of being immunocompromised, visited our hospital for a detailed examination of an ovarian tumor found during a medical checkup. She had a family history of prostate and pharyngeal cancer in her father and mother, respectively. Transvaginal ultrasonography showed a 70-mm cystic tumor with solid parts in the right ovary. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography and plain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a right ovarian teratoma and multiple enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes (Fig. 1 A). 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission, tomography-computed tomography revealed increased fluorodeoxyglucose accumulation in the right ovarian tumor and pelvic to axillary lymph nodes (Fig. 1 B). These clinical images suggested OMT-associated ovarian cancer with multiple lymph node metastases or TTM from malignant lymphoma to OMT. Carbohydrate antigen 125 level of 32.9 U/mL (normal range, ≤ 35.0 U/mL), carbohydrate antigen 19 − 9 level of 3.0 U/mL (normal range, ≤ 37.0 U/mL), and soluble Interleukin-2 receptors level of 432 U/mL (normal range, 204–587 U/mL) were normal. Soluble interleukin-2 receptors are one of the useful serum markers for lymphoma. A bilateral adnexectomy and retroperitoneal lymph node biopsy were performed, revealing a moderate amount of milky ascites. Macroscopically, the right ovarian tumor was a cystic mass with fat and solid parts (Fig. 1 C). Ascitic cytology revealed no neoplastic (Fig. 1 D). The cyst was lined by squamous epithelium constituting an OMT, and the solid part showed diffuse proliferation of abnormal lymphoid cells (Fig. 2 A-D). Immunohistochemically, abnormal lymphoid cells of the ovarian tumor tested negative for CD5, MUM1, and CyclinD1, and positive for CD10, CD20, CD21, BCL2, and BCL6 (Fig. 3 A-B). The abnormal lymphoid cells of the retroperitoneal lymph nodes were negative for CD5, CMYC, MUM1, and CyclinD1, and positive for CD10, CD20, CD21, CD79a, BCL2, and BCL6. Genetic analysis of the lymphoma using G-banding and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) identified a translocation of t(14;18) (q32;q21) (Fig. 3 C) and diagnosed TTM from nodal follicular lymphoma (histological grade 1) to OMT. Twelve months after the surgery, the patient showed no recurrence without adjuvant therapy.

A : Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image reveals a 70-mm right ovarian mass (red arrows) with a 20-mm crescent solid part at the dorsal side (white asterisks). B : Positron emission tomography-CT shows FDG accumulation in the solid component (white arrows), measuring SUV max od 8.3 and retroperitoneal lymph node (white arrowhead), measuring SUV max of 7.8. C : Right ovarian tumor, macroscopic examination shows cystic tumor filled with fatty and yellow sebaceous component and solid nodule (yellow arrows). D : Ascites cytology was no neoplastic findings

Microscopic examination of right ovarian tumor (H&E). A and B : Cystic wall covered with keratinized squamous epithelium. C and D : Microscopic examination shows the solid nodule consisted of diffusely proliferated abnormal lymphoid cells

Right ovarian tumor is positive for ( A ) BCL2 and ( B ) CD10. ( C ) FISH analysis. Red probes the centromere side of the BCL gene (18q21) breaking point, and green probes the telomeric side. Split signals were observed

TTM is defined as metastasis in distinct tumors of the same body, and 15 cases of TTM in ovarian tumors have been reported to date [ 5 ]. OMTs causes various cancers via malignant transformation; therefore, the coexistence of OMT and cancers requires the differentiation between primary and metastatic cancers.

Ten cases of primary malignant lymphoma derived from OMT have been reported [ 7 , 8 ]. TTM of malignant lymphoma to OMT is the only existing case of plasmablastic lymphoma [ 9 ]. TTM to OMT is summarized in Table 1 [ 3 , 5 , 6 , 9 ] and shows that the present case is the first recorded case of nodal follicular lymphoma metastasizing and extending to the OMT. Historically, the most common method for diagnosing TTM to OMT was immunohistochemical analysis (4/5 cases), followed by virological examination and FISH, which were performed in two cases each. This is the first molecular analysis report that combines G-banding and FISH. These results recommend molecular diagnostic approaches for TTM and OMT when morphological and immunohistochemical findings alone are insufficient for diagnoses.

Ozsan et al. divided 16 follicular lymphomas initially diagnosed in the ovary into two groups based on clinical, morphological, immunophenotypic, and genetic features [ 10 ]. Ozsan et al. reported that ovarian extension of nodal follicular lymphoma was characterized as low histologic grade, BCL2 protein positivity, and presence of t(14;18)(q32;q21), while true primary ovarian follicular lymphoma was characterized as higher histologic grade, CD10 and BCL2 negativity, and absence of t(14;18)(q32;q21) [ 10 ]. We diagnosed the present case with TTM from nodal follicular lymphoma to OMT based on the distribution of lymph node lesion (pelvic to axillary), genetic analysis of t(14;18)(q32;q21), immunohistochemical expression of BCL2 and CD10, and histologic grades (grade 1). However, this study included only one case of OMT [ 10 ]. It is unclear whether OMT-derived follicular lymphoma has the same biology as that of a conventional follicular lymphoma. Tamura et al. reported that SCCs derived from OMTs share genetic characteristics with pulmonary SCCs rather than cutaneous SCCs, which is the most common component of OMTs [ 11 ]. It is expected that more cases will be accumulated in the future.

To the best of our knowledge, the present case is the first report of follicular lymphoma metastasizing and extending to the OMT. To make this differential diagnosis of TTM and primary ovarian follicular lymphoma, we used immunohistochemical and molecular analyses (G-banding and FISH) for the first time.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Hackethal A, Brueggmann D, Bohlmann MK, Franke FE, Tinneberg HR, Münstedt K. Squamous-cell carcinoma in mature cystic teratoma of the ovary: systematic review and analysis of published data. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1173–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70306-1 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yano M, Nasu K, Yasuda M, Katoh T, Kagabu M, Kobara H, et al. Clinicopathological features and programmed death-ligand 1 immunohistochemical expression in a multicenter cohort of uterine and ovarian melanomas: a retrospective study in Japan (KCOG-G1701s). Melanoma Res. 2022;32:150–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CMR.0000000000000811 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kirova YM, Feuilhade F, de Baecque-Fontaine C, Le Bourgeois JP. Metastasis of a breast carcinoma in a mature teratoma of the ovary. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1999;20:223–5.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

De Waal YR, Thomas CM, Oei AL, Sweep FC, Massuger LF. Secondary ovarian malignancies: frequency, origin, and characteristics. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1160–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181b33cce .

Yano M, Katoh T, Hamaguchi T, Kozawa E, Hamada M, Nagata K, et al. Tumor-to-tumor metastasis from appendiceal adenocarcinoma to an ovarian mature teratoma, mimicking malignant transformation of a teratoma: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2019;14:88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-019-0865-6 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Santos F, Oliveira C, Caldeira JP, Coelho A, Félix A. Metastatic endocervical adenocarcinoma in a mature cystic teratoma: a case of a tumor-to-tumor metastasis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2018;37:559–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/PGP.0000000000000457 .

Hutspardol S, Li Y, Dube V, Delabie J. Concurrent primary follicular lymphoma and a mature cystic teratoma of the ovary: a Case report and review of literature. Case Rep Pathol. 2022;2022:5896696. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5896696 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tandon N, Sultana S, Sun H, Zhang S. Follicular lymphoma arising in a mature cystic teratoma in a 26 year old female. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2016;46:298–301.

PubMed Google Scholar

Hadžisejdić I, Babarović E, Vranić L, Duletić Načinović A, Lučin K, Krašević M, et al. Unusual presentation of plasmablastic lymphoma involving ovarian mature cystic teratoma: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12:83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-017-0672-x .

Ozsan N, Bedke BJ, Law ME, Inwards DJ, Ketterling RP, Knudson RA, et al. Clinicopathologic and genetic characterization of follicular lymphomas presenting in the ovary reveals 2 distinct subgroups. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1691–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31822bd8a8 .

Tamura R, Yoshihara K, Nakaoka H, Yachida N, Yamaguchi M, Suda K, et al. XCL1 expression correlates with CD8-positive T cells infiltration and PD-L1 expression in squamous cell carcinoma arising from mature cystic teratoma of the ovary. Oncogene. 2020;39:3541–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-020-1237-0 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage ( www.editage.jp ) for the English language editing.

This research was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (22K15409) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, and The Seiichi Imai Memorial Foundation.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Oita University, Oita, Japan

Yusuke Sato, Mitsutake Yano, Satoshi Eto & Kaei Nasu

Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology, Faculty of Medicine, Oita University, Oita, Japan

Kuniko Takano

Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Support System for Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Oita University, Oita, Japan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

YS and MY: conception, pathological diagnosis, immunohistochemical analysis, molecular analysis, writing of the manuscript. SE: collection of clinical data. KT: Immunohistochemical and molecular analyses. KN: Collection of clinical data and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mitsutake Yano .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.