Causes of the Russian Revolution

Photos.com / Getty Images

- European Revolutions

- European History Figures & Events

- Wars & Battles

- The Holocaust

- Industry and Agriculture History in Europe

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- B.S., Texas A&M University

The Russian Revolution of 1917 stands as one of the most impactful political events of the 20th century. Lasting from March 8, 1917, to June 16, 1923, the violent revolution saw the overthrow of the tradition of czarist rulers by the Bolsheviks , led by leftist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin . Perhaps more significant to the future of international politics and security, Lenin’s Bolsheviks would go on to form the Communist Party of the Soviet Union .

Key Takeaways: Causes of the Russian Revolution

- The Bolshevik-led Russian Revolution of 1917, in overthrowing Tsar Nicholas II, ended over 300 years of autocratic tsarist rule.

- The Russian Revolution lasted from March 8, 1917, to June 16, 1923.

- Primary causes of the Revolution included peasant, worker, and military dissatisfaction with corruption and inefficiency within the czarist regime, and government control of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Primary causes of the Russian Revolution included widespread corruption and inefficiency within the czarist imperial government, growing dissatisfaction among peasants, workers, and soldiers, the monarchy’s level of control over the Russian Orthodox Church, and the disintegration of the Imperial Russian Army during World War I .

Changes in the Working Class

The social causes of the Russian Revolution can be traced to the oppression of both the rural peasant class and the urban industrial working class by the tsarist regime and the costly failures of Tsar Nicholas II in World War I. The rather delayed industrialization of Russia in the early 20th century triggered immense social and political changes that resulted in interrelated dissatisfaction among both the peasants and the workers.

Peasant Dissatisfaction

Under the elementary theory of property, Russian peasants believed that land should belong to those who farmed it. While they had been emancipated from serfdom by Tsar Alexander II in 1861, rural agrarian peasants resented being forced to pay the government back for their minimal allotments of land and continued to press for communal ownership of the land they worked. Despite feeble attempts at land reforms in the early 20th century, Russia continued to consist mainly of poor farming peasants and a glaring inequality of land ownership, with 25% of the nation’s land being privately owned by only 1.5% of the population.

Dissatisfaction was further exacerbated by the growing numbers of rural peasant villagers moving to and from urban areas leading to the disruptive influences of city culture on pastoral village life through the introduction of previously unavailable consumer goods, newspapers, and word of mouth.

Working Class Dissatisfaction

By the end of the 19th century, Russia’s cities were growing rapidly as hundreds of thousands of people moved to urban areas to escape poverty. Between 1890 and 1910, for example, then Russia’s capital, Saint Petersburg, grew from 1,033,600 to 1,905,600, with Moscow experiencing similar growth. The resulting “proletariat”—an expanded working class possessing economically valuable skills—became more likely to go on strike and to publicly protest than the dwindling peasant class had been in the past.

Instead of the wealth realized by workers in Western Europe and the United States, the Industrial Revolution in Russia left workers facing unsafe working conditions, low wages, and few worker’s rights. The once well-off Russian working class was suddenly confronted with overcrowded housing often with deplorable sanitary conditions, and long work hours. Even on the eve of World War I, workers were putting in 10 to 12-hour workdays six days a week. The constant risk of injury and death from unsafe and unsanitary working conditions along with harsh physical discipline and inadequate wages added to the proletariat’s growing discontent.

Despite these hardships, many workers were encouraged to expect more from life. The self-respect and confidence gained from their newly acquired essential skills served to heighten workers’ expectations and desires. Now living in cities, workers came to desire consumer products they had never seen in villages. More importantly to the looming revolution, workers living in cities were more likely to be swayed by new—often rebellious—ideas about political and social order.

No longer considering Tsar Nicholas II to be the protector of the working class, strikes and public disorder from this new proletariat increased rapidly in number and violence, especially after the “Bloody Sunday” massacre of January 22, 1905, in which hundreds of unarmed protestors were killed by Nicholas’ elite troops.

When Russia entered World War I in 1914, the vast demand for factories to produce war supplies triggered even more labor riots and strikes. Already largely opposed to the war, the Russian people supported the workers. Equally unpopular forced military service stripped cities of skilled workers, who were replaced by unskilled peasants. When the inadequate railway system combined with the diversion of resources, production, and transport to war needs caused widespread famine, droves of remaining workers fled the cities seeking food. Suffering from a lack of equipment and supplies, the Russian soldiers themselves finally turned against the Tsar. As the war progressed, many of the military officers who remained loyal to the Tsar were killed and replaced by discontented draftees with little loyalty to the Tsar.

Unpopular Government

Even before World War I, many sections of Russia had become dissatisfied with the autocratic Russian government under Czar Nicholas II, who had once declared, “One Czar, One Church, One Russia.” Like his father, Alexander III, Nicholas II applied an unpopular policy of “Russification,” a process that required non-ethnic Russian communities, such as Belarus and Finland, to give up their native culture and language in favor of Russian culture.

An extremely conservative ruler, Nicholas II maintained strict authoritarian control. Individual citizens were expected to show unquestioned devotion to their community, acquiescence to the mandated Russian social structure, and a sense of duty to the country.

Blinded by his visions of the Romanov monarchy that has ruled Russia since 1613, Nicholas II remained unaware of the declining state of his country. Believing his power had been granted by Divine Right, Nicholas assumed that the people would show him unquestioning loyalty. This belief made him unwilling to allow social and political reforms that could have relieved the suffering of the Russian people resulting from his incompetent management of the war effort.

Even after the events of the failed Russian Revolution of 1905 had spurred Nicholas II to grant the people minimal civil rights, he proceeded to limit these liberties in order to maintain the ultimate authority of the Tsarist Monarchy . In the face of such oppression, the Russian people continued to press Nicholas II to allow democratic participation in government decisions. Russian liberals, populists, Marxists , and anarchists supported social and democratic reform.

Heritage Images / Getty Images

The people’s dissatisfaction with the autocratic Russian government peaked after the Bloody Sunday massacre of January 1905. The resulting crippling worker strikes forced Nicholas II to choose between either establishing a military dictatorship or allowing the creation of a limited constitutional government. Though both he and his advising minister had reservations about granting a constitution, they decided it would tactically be the better choice. Thus on October 17, 1905, Nicholas issued the October Manifesto promising to guarantee civil liberties and establishing Russia’s first parliament —the Duma. Members of the Duma were to be popularly elected and their approval would be required before the enactment of any legislation. In 1907, however, Nicholas disbanded the first two Dumas when they failed to endorse his autocratic policies. With the loss of the Dumas, quashed hopes for democracy fueled a renewed revolutionary fervor among all classes of the Russian people as violent protests criticized the Monarchy.

Church and Military

At the time of the Russian Revolution, the Tsar was also the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, which played an integral role in the autocratic government. Reinforcing the Tsars’ authority, Official Church doctrine declared that the Tsar had been appointed by God, thus any challenge to—the “Little Father”—was considered an insult to God.

Mostly illiterate at the time, the Russian population relied heavily on what the Church told them. Priests were often financially rewarded for delivering the Tsar’s propaganda. Eventually, the peasants began to lose respect for the priests, seeing them as increasingly corrupt and hypocritical. Overall, the Church and its teachings became less respected during the rule of Nicholas II.

The level to which the Church was subservient to the Tsarist state remains a topic of debate. However, the Church’s freedom to take independent activity was limited by the edicts of Nicholas II. This extent of state control over religion angered many clergy members and lay believers alike.

Feelings of Russian national unity following the outbreak of World War I in August 1914 briefly quelled the strikes and protests against the Tsar. However, as the war dragged on, these feelings of patriotism faded. Angered by staggering losses during just the first year of the war, Nicholas II took over command of the Russian Army. Personally directing Russia’s main theatre of war, Nicholas placed his largely incapable wife Alexandra in charge of the Imperial government. Reports of corruption and incompetence in the government soon began to spread as the people became increasingly critical of the influence of self-proclaimed “mystic” Grigori Rasputin over Alexandra and the Imperial family.

Under the command of Nicholas II, Russian Army war losses grew quickly. By November 1916, a total of over five million Russian soldiers had been killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. Mutinies and desertions began to occur. Lacking food, shoes, ammunition, and even weapons, discontent and lowered morale contributed to more crippling military defeats.

The war also had a devastating effect on the Russian people. By the end of 1915, the economy was failing due to wartime production demands. As inflation reduced income, widespread food shortages and rising prices made it difficult for individuals to sustain themselves. Strikes, protests, and crime increased steadily in the cities. As suffering people scoured the streets for food and firewood, resentment for the wealthy grew.

As the people increasingly blamed Tsar Nicholas for their suffering, the meager support he had left crumbled. In November 1916, the Duma warned Nicholas that Russia would become a failed state unless he allowed a permanent constitutional government to be put in place. Predictably, Nicholas refused and Russia’s Tsarist regime, which had endured since the reign of Ivan the Terrible in 1547, collapsed forever during the Revolution of February 1917. Less than one year later, Tsar Nicholas II and his entire family were executed.

Nationalist and Revolutionary Sentiments

Nationalism as an expression of cultural identity and unity first arose in Russia in the early 19th century and soon became incorporated into pan-Slavism—an anti-Western movement advocating the union of all Slavs or all Slavic peoples of eastern and east-central Europe into a single powerful political organization. Following Nicholas II’s doctrine of “Russification,” Russian Slavophiles opposed allowing the influences of Western Europe to alter Russian culture and traditions.

In 1833, Emperor Nicholas I adopted the decidedly nationalistic motto “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality” as the official ideology of Russia. Three components of the triad were:

- Orthodoxy: Adherence to Orthodox Christianity and protection of the Russian Orthodox Church.

- Autocracy: Unconditional loyalty to the Imperial House of Romanov in return for paternalist protection of all orders of social hierarchy in Christianity.

- Nationality: A sense of belonging to a particular nation and sharing that nation’s common history, culture, and territory.

To a large extent, however, this brand of state-proclaimed Russian nationalism was largely intended to divert public attention from the inner tensions and contradictions of the autocratic Tsarist system after the enactment of Nicholas II’s October Manifesto.

Expressions of Russian nationalism all but vanished during the nation’s disastrous experience in World War I but reemerged following the Bolshevik’s triumph in the 1917 Revolution and the collapse of the tsarist Russian empire. Nationalist movements first increased among the different nationalities that lived in the ethically diverse country.

In developing its policy on nationalism, the Bolshevik government largely followed Marxist-Leninist ideology. Lenin and Karl Marx advocated for a worldwide worker revolution that would result in the elimination of all nations as distinct political jurisdictions. They thus considered nationalism to be an undesirable bourgeois capitalist ideology.

However, the Bolshevik leaders considered the inherent revolutionary potential of nationalism to be a key to advancing the revolution envisioned by Lenin and Marx, and so supported the ideas of self-determination and the unique identity of nations.

On November 21, 1917, just one month after the October Revolution, the Declaration of the Rights of the People of Russia promised four key principles:

- The equality and sovereignty—the principle holding that source of governmental power lies with the people—of all peoples of the Russian empire.

- The right of self-determination for all nations.

- The elimination of all privileges based on nationality or religion.

- Freedom of cultural preservation and development for Russian ethnic minorities.

The newly formed Communist Soviet government, however, resisted the implementation of these ideals. Of all the different countries which had at least perilously coexisted in the tsarist Russian empire, only Poland, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia were granted independence. However, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia lost their independence when they were occupied by the Soviet Army in 1940.

Soviet leaders had hoped the 1917 Revolution would trigger what Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky had called a “Permanent Revolution” spreading socialist ideas from country to country. As history has proven, Trotsky’s vision was not to become reality. By the early 1920s, even the Soviet leaders realized that most developed nations would, by their nationalistic nature, remain autonomous.

Today, Russian extremist nationalism often refers to far-right and a few far-left ultra-nationalist movements. The earliest example of such movements dates to early 20th century Imperial Russia when the far-right Black Hundred group opposed the more popular Bolshevik revolutionary movement by staunchly supporting the House of Romanov and opposing any departure from the autocracy of the reigning tsarist monarchy.

- McMeekin, Sean. “The Russian Revolution: A New History.” Basic Books, March 16, 2021, ISBN-10: 1541675487.

- Trotsky, Leon. “History of the Russian Revolution.” Haymarket Books, July 1, 2008, ISBN-10: 1931859450.

- Baron, Samuel H. “Bloody Saturday in the Soviet Union.” Stanford University Press, May 22, 2001, ISBN-10: 0804752311.

- Gatrell, Peter. “Russia's First World War: A Social and Economic History.” Routledge, April 7, 2005, ISBN-10: 9780582328181.

- Tuminez, Astrid. “Russian Nationalism and Vladimir Putin's Russia.” American International Group, Inc. . April 2000, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/media/csis/pubs/pm_0151.pdf.

- Kolstø, Pal and Blakkisrud, Helge. “The New Russian Nationalism.” Edinburgh University Press, March 3, 2016, ISBN 9781474410434.

- Biography of Czar Nicholas II, Last Czar of Russia

- Bloody Sunday: Prelude to the Russian Revolution of 1917

- Execution of Czar Nicholas II of Russia and His Family

- The Russian Revolution of 1917

- Russian Revolution Timeline

- Timeline of the Russian Revolutions: 1905

- Timeline of the Russian Revolutions: 1906 - 1913

- Timeline of the Russian Revolutions: 1918

- Who Were the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks?

- The Russian Civil War

- Biography of Leon Trotsky, Russian Marxist Revolutionary

- The Red Terror

- Top Books: Modern Russia - The Revolution and After

- Causes of the Russian Revolution Part 2

- The Duma in Russian History

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Russian Revolution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 27, 2024 | Original: March 12, 2024

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was one of the most explosive political events of the 20th century. The violent revolution marked the end of the Romanov dynasty and centuries of Russian Imperial rule. Economic hardship, food shortages and government corruption all contributed to disillusionment with Czar Nicholas II. During the Russian Revolution, the Bolsheviks, led by leftist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, seized power and destroyed the tradition of czarist rule. The Bolsheviks would later become the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

When Was the Russian Revolution?

In 1917, two revolutions swept through Russia, ending centuries of imperial rule and setting into motion political and social changes that would lead to the eventual formation of the Soviet Union .

However, while the two revolutionary events took place within a few short months of 1917, social unrest in Russia had been brewing for many years prior to the events of that year.

In the early 1900s, Russia was one of the most impoverished countries in Europe with an enormous peasantry and a growing minority of poor industrial workers. Much of Western Europe viewed Russia as an undeveloped, backwards society.

The Russian Empire practiced serfdom—a form of feudalism in which landless peasants were forced to serve the land-owning nobility—well into the nineteenth century. In contrast, the practice had disappeared in most of Western Europe by the end of the Middle Ages .

In 1861, the Russian Empire finally abolished serfdom. The emancipation of serfs would influence the events leading up to the Russian Revolution by giving peasants more freedom to organize.

What Caused the Russian Revolution?

The Industrial Revolution gained a foothold in Russia much later than in Western Europe and the United States. When it finally did, around the turn of the 20th century, it brought with it immense social and political changes.

Between 1890 and 1910, for example, the population of major Russian cities such as St. Petersburg and Moscow nearly doubled, resulting in overcrowding and destitute living conditions for a new class of Russian industrial workers.

A population boom at the end of the 19th century, a harsh growing season due to Russia’s northern climate, and a series of costly wars—starting with the Crimean War —created frequent food shortages across the vast empire. Moreover, a famine in 1891-1892 is estimated to have killed up to 400,000 Russians.

The devastating Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 further weakened Russia and the position of ruler Czar Nicholas II . Russia suffered heavy losses of soldiers, ships, money and international prestige in the war, which it ultimately lost.

Many educated Russians, looking at social progress and scientific advancement in Western Europe and North America, saw how growth in Russia was being hampered by the monarchical rule of the czars and the czar’s supporters in the aristocratic class.

Russian Revolution of 1905

Soon, large protests by Russian workers against the monarchy led to the Bloody Sunday massacre of 1905 . Hundreds of unarmed protesters were killed or wounded by the czar’s troops.

The Bloody Sunday massacre sparked the Russian Revolution of 1905, during which angry workers responded with a series of crippling strikes throughout the country. Farm laborers and soldiers joined the cause, leading to the creation of worker-dominated councils called “soviets.”

In one famous incident, the crew of the battleship Potemkin staged a successful mutiny against their overbearing officers. Historians would later refer to the 1905 Russian Revolution as ‘the Great Dress Rehearsal,” as it set the stage for the upheavals to come.

Nicholas II and World War I

After the bloodshed of 1905 and Russia’s humiliating loss in the Russo-Japanese War, Nicholas II promised greater freedom of speech and the formation of a representative assembly, or Duma, to work toward reform.

Russia entered into World War I in August 1914 in support of the Serbs and their French and British allies. Their involvement in the war would soon prove disastrous for the Russian Empire.

Militarily, imperial Russia was no match for industrialized Germany, and Russian casualties were greater than those sustained by any nation in any previous war. Food and fuel shortages plagued Russia as inflation mounted. The already weak economy was hopelessly disrupted by the costly war effort.

Czar Nicholas left the Russian capital of Petrograd (St. Petersburg) in 1915 to take command of the Russian Army front. (The Russians had renamed the imperial city in 1914, because “St. Petersburg” sounded too German.)

Rasputin and the Czarina

In her husband’s absence, Czarina Alexandra—an unpopular woman of German ancestry—began firing elected officials. During this time, her controversial advisor, Grigory Rasputin , increased his influence over Russian politics and the royal Romanov family .

Russian nobles eager to end Rasputin’s influence murdered him on December 30, 1916. By then, most Russians had lost faith in the failed leadership of the czar. Government corruption was rampant, the Russian economy remained backward and Nicholas repeatedly dissolved the Duma , the toothless Russian parliament established after the 1905 revolution, when it opposed his will.

Moderates soon joined Russian radical elements in calling for an overthrow of the hapless czar.

February Revolution

The February Revolution (known as such because of Russia’s use of the Julian calendar until February 1918) began on March 8, 1917 (February 23 on the Julian calendar).

Demonstrators clamoring for bread took to the streets of Petrograd. Supported by huge crowds of striking industrial workers, the protesters clashed with police but refused to leave the streets.

On March 11, the troops of the Petrograd army garrison were called out to quell the uprising. In some encounters, the regiments opened fire, killing demonstrators, but the protesters kept to the streets and the troops began to waver.

The Duma formed a provisional government on March 12. A few days later, Czar Nicholas abdicated the throne, ending centuries of Russian Romanov rule.

Alexander Kerensky

The leaders of the provisional government, including young Russian lawyer Alexander Kerensky, established a liberal program of rights such as freedom of speech, equality before the law, and the right of unions to organize and strike. They opposed violent social revolution.

As minister of war, Kerensky continued the Russian war effort, even though Russian involvement in World War I was enormously unpopular. This further exacerbated Russia’s food supply problems. Unrest continued to grow as peasants looted farms and food riots erupted in the cities.

Bolshevik Revolution

On November 6 and 7, 1917 (or October 24 and 25 on the Julian calendar, which is why the event is often referred to as the October Revolution ), leftist revolutionaries led by Bolshevik Party leader Vladimir Lenin launched a nearly bloodless coup d’état against the Duma’s provisional government.

The provisional government had been assembled by a group of leaders from Russia’s bourgeois capitalist class. Lenin instead called for a Soviet government that would be ruled directly by councils of soldiers, peasants and workers.

The Bolsheviks and their allies occupied government buildings and other strategic locations in Petrograd, and soon formed a new government with Lenin as its head. Lenin became the dictator of the world’s first communist state.

Russian Civil War

Civil War broke out in Russia in late 1917 after the Bolshevik Revolution. The warring factions included the Red and White Armies.

The Red Army fought for the Lenin’s Bolshevik government. The White Army represented a large group of loosely allied forces, including monarchists, capitalists and supporters of democratic socialism.

On July 16, 1918, the Romanovs were executed by the Bolsheviks. The Russian Civil War ended in 1923 with Lenin’s Red Army claiming victory and establishing the Soviet Union.

After many years of violence and political unrest, the Russian Revolution paved the way for the rise of communism as an influential political belief system around the world. It set the stage for the rise of the Soviet Union as a world power that would go head-to-head with the United States during the Cold War .

The Russian Revolutions of 1917. Anna M. Cienciala, University of Kansas . The Russian Revolution of 1917. Daniel J. Meissner, Marquette University . Russian Revolution of 1917. McGill University . Russian Revolution of 1905. Marxists.org . The Russian Revolution of 1905: What Were the Major Causes? Northeastern University . Timeline of the Russian Revolution. British Library .

Photo Galleries

HISTORY Vault: Vladimir Lenin: Voice of Revolution

Called treacherous, deluded and insane, Lenin might have been a historical footnote but for the Russian Revolution, which launched him into the headlines of the 20th century.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

- 20th Century

What Were the Key Causes of the Russian Revolution?

02 Nov 2020

The Russian Revolution of 1917 marked the end of the 300-year Romanov dynasty and the start of a communist system of government. Rather than being triggered by one event, the Revolution was the result of a number of different economic, military and political factors that had been developing over decades.

Changes in society

For much of the 19th century, Russia remained relatively backward, with few roads and limited industrialisation, and a wide class divide. Following the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, agriculture remained in the hands of peasants and former landowners, relying predominantly on traditional methods.

Toward the end of the century, Russia experienced a large population increase, and its late and rapid industrialisation resulted in hundreds of thousands of people moving to urban areas out of financial necessity. This led to overcrowding and poor working conditions, with low wages, unsafe practices and few rights.

Nevertheless, acquiring new skills gave them a sense of self-respect and confidence, increasing expectations and exposing them to new ideas. After 1905’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ massacre, strikes and public disorder from this new proletariat rapidly increased, no longer seeing the Tsar as their champion.

The Tsar’s incompetence

Tsar Nicholas II was a deeply conservative autocratic ruler. He believed he had been granted the power to rule by divine right and assumed this gave him the unquestioning loyalty of his people.

Detached from their plight, Nicholas refused to allow progressive reforms or accept any reduction in power. Religious faith was used as a means of political authority, exercised through the clergy and later through the Cossacks and secret police.

Tsar Nicholas II (Image Credit: Public Domain).

However, Bloody Sunday forced Nicholas to create the October Manifesto, making a number of concessions to decree limited civil rights and a democratically elected parliament, the Duma. Nevertheless, he worked to limit these to preserve his authority, dismissing the first two Dumas.

Nicholas was unprepared for the outbreak of World War One, but he was keen to restore Russia’s prestige after the Russo-Japanese War in 1904/5, and use the war to create national unity. However, he failed to choose skilled leaders, was disorganised in ensuring adequate supplies, and made poor strategic decisions throughout the war, leading to huge losses.

In Autumn 1915, Nicholas declared himself Commander in Chief of the army and departed for the Eastern Front, believing this would inspire the soldiers to fight with renewed vigour. By removing himself from a political role and now in sole command, he consequently bore more personal responsibility for any military failure. His absence also left a weakened government.

The Tsarina and the war

Nicholas’ departure left his wife, Tsarina Alexandra, in control. She wasn’t popular, and as a German princess, raised suspicions as to where her true loyalties lay.

Alexandra gained increasing influence over the appointment of ministers to the government and determined that no member should be in a strong enough position to challenge her husband’s authority. Consequently, the government tended to be filled with increasingly weak and incompetent men – leading to rumours she was a German collaborator.

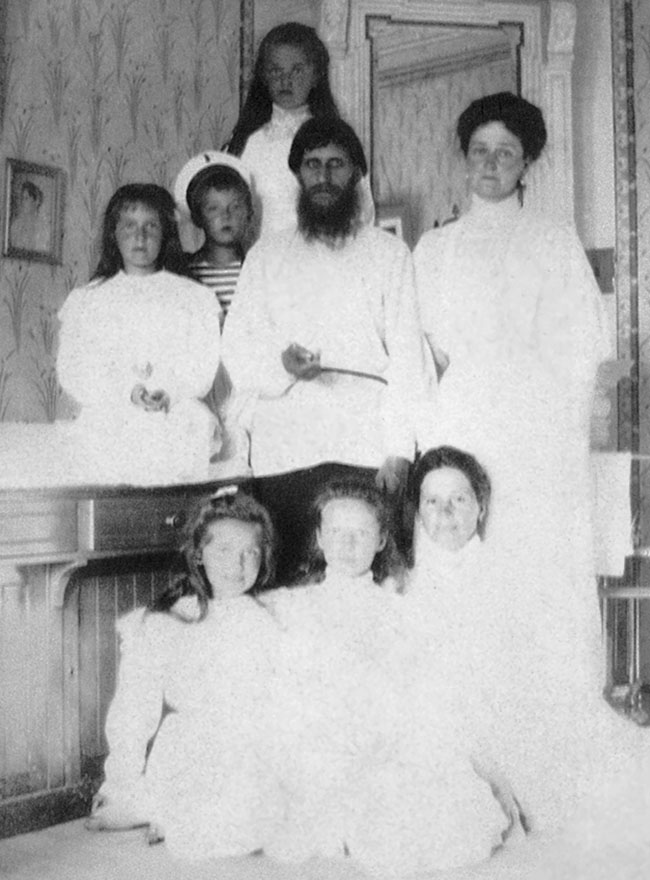

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna with Rasputin, her children and a governess.

Rasputin and his influence over the Tsarina

Alexandra became strongly influenced by a Siberian monk, Rasputin , who was a mystic and self-proclaimed holy man. Although infamous for his drunkenness and womanising, Rasputin also gained a reputation as a healer who could perform amazing feats.

Nicholas and Alexandra had 4 daughters and a son, Alexei, who had haemophilia. Rasputin was summoned by Alexandra to pray for Alexei after he had an internal haemorrhage in spring 1907. After Alexei recovered, Alexandra became convinced Rasputin could control Alexei’s illness, and his influence over the Tsarina became considerable, advising her on government appointments and important decisions.

Rasputin soon became a controversial figure, bringing ridicule on the royal family. He was accused by his enemies of religious heresy and rape, and was rumoured to be having an affair with the Tsarina.

After Rasputin’s murder in December 1916 by Russian aristocrats, Alexandra’s behaviour became more erratic, and she failed to even attempt to address the challenges posed to government in Nicholas’ absence.

Impact of the First World War

Instead of restoring Russia’s prestige, the First World War led to the deaths of almost 2 million Russian soldiers and multiple military defeats.

When Russia entered the war, it was distinctly less industrialized than its allies, with a weakened navy following the 1904 Russo-Japanese War. The addition of the Ottoman Empire to the Central Powers cut off essential trade routes, contributing to munition shortages. Military defeats such as the 1914 Battle of Tannenberg sapped morale, as did the superior German army’s shift of focus to the Eastern front in 1915.

As the war progressed, many officers loyal to the Tsar were killed and replaced by discontented conscripts, with little loyalty to the Tsar. Soldiers were ill-equipped and staggering losses increasingly led to mutinies and revolts.

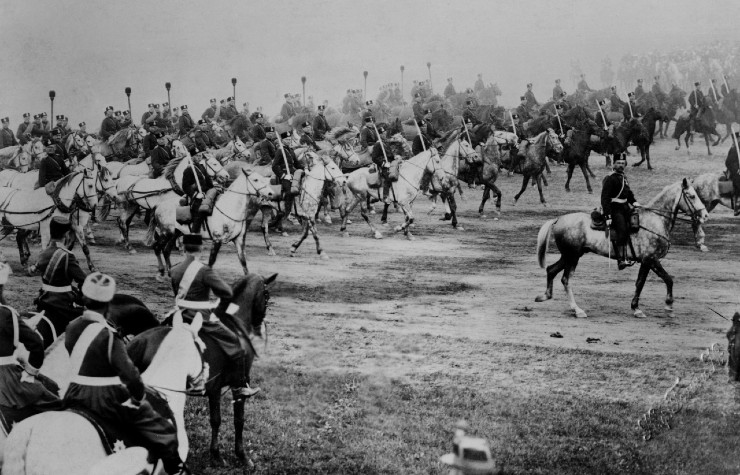

Tsar Nicolas II reviewing Russian troops. When Russia entered World War One, its army was the largest, but least modern of the major European powers. (Image Credit: Everett Collection / Shuttershock).

Economic problems

The vast demand for factory production of war supplies and workers resulted in labour riots and strikes, as did conscription, which took skilled workers from the cities, replacing them with unskilled peasants.

Conscripted peasants were also a large part of the Russian army. This led to a shortage of farm workers, hugely impacting production. By the end of 1915, there were signs the economy was breaking down due to wartime demand. The government attempted to address this by printing more money, but this led to high inflation. Underdeveloped railway systems led to food shortages and rising prices, with workers increasingly abandoning cities to seek food.

The Tsarina failed to address strikes and protests in late 1916 and by the time revolution hit, Russia’s economy was near collapse.

Peasant and worker discontent

The scorched earth policy during the 1915 Russian army retreat destroyed large areas of peasant farmland, ruining their livelihoods. Meanwhile living conditions deteriorated, with shortages in shops and a severe lack of food. This was made worse by peasants hoarding grain for themselves, and the railways being committed to the war effort, unavailable to transport supplies to the cities.

These shortages exacerbated social unrest, creating a powder-keg of despair and anger. Revolutionary groups continued to attract support, aided by the Bolshevik newspaper, Pravda. They believed a worker-run government should replace Tsarist rule, and the shortages provided the ideal opportunity to gain support.

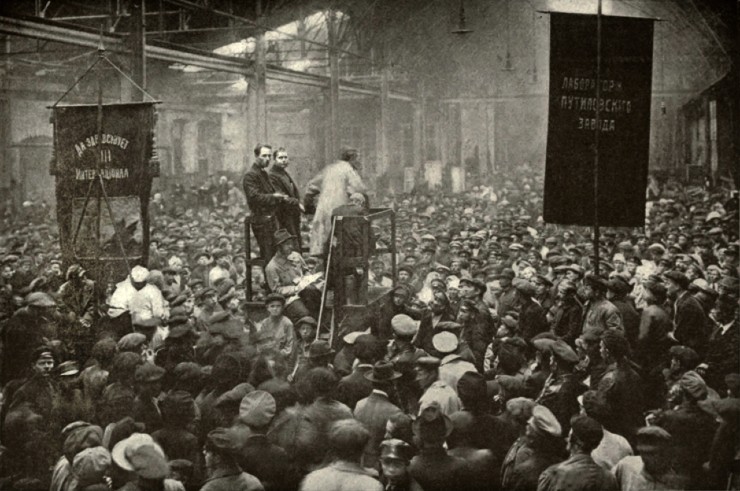

In January 1917, to commemorate Bloody Sunday, thousands of workers went on strike in St Petersburg. In February, further rioting broke out, initially in response to an announcement on bread rationing. Strikers from the Putilov Engineering Plant joined the crowds at the celebration of International Women’s Day.

Meeting in the Putilov Works in Petrograd during the 1917 Russian Revolution. In February 1917 strikes at the factory contributed to the February Revolution. (Image Credit: Shuttershock).

As numbers increased, some of the Tsar’s forces opened fire. Angry protestors broke into the barracks of the city’s Pavlovsky Regiment, yet the Cossack soldiers refused orders to fire on the crowds, joining the protestors and mutinying against the Tsar.

Seize of Power

Dismissing this as short-lived, Nicholas attempted to return to St Petersburg to reclaim authority, but his train was diverted by revolutionaries to Pskov. Isolated and powerless, he was forced to abdicate.

A Provisional Government replaced Nicholas (after his brother refused the crown), but carried on fighting the war. Lenin claimed the government was imperialist in doing so, and undeserving of Socialist support. As the Provisional Government’s power waned, Bolshevik influence increased. As shortages and military defeats continued, Lenin and the Bolsheviks determined to seize power in the name of the Soviets.

Vladimir Lenin during the Russian Revolution of October 1917. (Image Credit: Alamy).

In October 1917 they stormed the Winter Palace, and arrested the Provisional Government, putting themselves in charge.

A year later the Tsar and his family were executed. Russia had changed forever.

You May Also Like

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

The Princes in the Tower: Solving History’s Greatest Cold Case

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Russian Revolutions and Civil War, 1917–1921

Introduction, general overviews.

- Bibliographies and Reference Works

- Prior to 1991

- Prior to 1980

- Eyewitness Accounts

- Collections of Articles and Essays

- The February Revolution and the Provisional Government

- The October Revolution and the Establishment of the Bolshevik Regime

- Foreign Reaction and Intervention

- Political Parties

- Political Figures and Intellectuals

- Workers, Peasants, and Soldiers

- Non-Russian Nationalities

- The Bolshevik State and Private Property

- The Comintern

- Monographs and Biographies

- Essay and Documentary Collections

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Intervention and Use of Force

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Crisis Bargaining

- History of Brazilian Foreign Policy (1808 to 1945)

- Indian Foreign Policy

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Russian Revolutions and Civil War, 1917–1921 by Michael Kort LAST REVIEWED: 09 February 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 22 September 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199743292-0088

The Russian Revolution has not permitted Western historians the comfort of neutrality. It led to the establishment of a regime, the Soviet Union, that on the basis of Marxist ideology claimed to be building the world’s first nonexploitative and egalitarian society. As such, the Soviet regime further claimed to represent humanity’s future and therefore the right to spread its communist revolution worldwide. These pretentions, however dubiously realized in practice, won the Soviet Union millions of loyalists over the world. At the same time, because these pretentions also threatened any society organized according to different principles, including those of liberal democracy and free enterprise, they made the Soviet regime the object of intense fear and opposition. This reaction was reinforced as the Soviet Union quickly became a brutal dictatorship and, after World War II, emerged as one of the world’s two nuclear superpowers. For these reasons Western scholarship on the Russian Revolution has had an element of contentiousness not often seen in other fields. That, in turn, is why any serious student of the Russian Revolution must be familiar with its historiography, and why this article not only contains a major section on historiography but also includes historiographic commentary in many of the individual entries. The term Russian Revolution itself refers to two upheavals that took place in 1917: the February Revolution and the October, or Bolshevik, Revolution. The former was a spontaneous uprising that began in Russia’s capital in late February 1917 and led to the collapse of the tsarist monarchy and the establishment of the Provisional Government, a regime based on the premise that Russia should have a parliamentary government and free-enterprise economic system. The latter took place in late October and was the seizure of power by a militant Marxist political party determined to rule alone, turn Russia into a communist society, and spark a worldwide revolution. (These dates are according to the outdated Julian calendar in use in Russia at the time, which trailed the Gregorian calendar used in the West by thirteen days. According to the Gregorian calendar, the two revolutions took place in March and November, respectively.) Because the Bolsheviks did not consolidate their power until their victory in a three-year civil war, many histories ostensibly about the “Russian Revolution” include not only the events of 1917 but also their immediate aftermath in early 1918, and then the civil war, which began in mid-1918 and lasted until 1921. That framework has been adopted for this article as well. Matters of evidence and documentation have additionally complicated this subject. In this case the key date is 1991, as that is when the collapse of the Soviet Union finally made many important Russian archives available to scholars for the first time. This significant development is covered in the Published Documentary Collections section of this article.

Although all of the volumes listed in this section can be called general overviews, they vary considerably in their structure and approach. Carr 1950–1953 provides a multivolume and extraordinarily detailed institutional narrative of the establishment and consolidation of the Bolshevik regime, which the author essentially endorses. Chamberlin 1965 is a traditional, sweeping narrative that is critical of the Bolshevik regime, as is Figes 1998 , which begins the story in 1891 and carries it to 1924. Pipes 1996 provides a broad narrative in the condensation of two large volumes on this subject, and provides a view that is highly critical of the Bolshevik regime. Schapiro 1984 , likewise, is an interpretive essay, albeit from a liberal perspective critical of the Bolsheviks. Read 1996 is a revisionist narrative that, while scholarly, comes close to being a textbook. (See the introduction to the Historiography section for the definition of revisionist and related terms in the context of Soviet history.) Shukman 1998 is a short survey with a conclusion critical of the Bolshevik regime. Engelstein 2017 covers the period 1914 to 1921 with an emphasis on how the Bolsheviks betrayed the prevailing democratic sentiments in Russia in 1917 and successfully mobilized power to crush their opponents between 1917 and 1921. McMeekin 2017 begins in 1905 and covers through 1922, stressing how blunders first by Nicholas II and then by the Provisional Government under Kerensky’s inept leadership opened the gates for Lenin and the Bolsheviks to come to power. Smith 2017 covers the period 1890 to 1928, focusing on economic and social factors that caused the revolutions of 1917 and affected the Bolshevik regime into the late 1920s.

Carr, Edward Hallett. A History of Soviet Russia: The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917–1923 . 3 vols. London: Macmillan, 1950–1953.

DOI: 10.1007/978-1-349-63648-8

The first three volumes of a series that, first under Carr and then R. W. Davies, eventually totaled fourteen volumes and thousands of pages upon reaching its terminus in 1929. Some scholars argue these volumes constitute a classic work; others, largely because Carr writes as if the Bolshevik regime was the inevitable outcome of the revolution that ended the tsarist regime, dismiss them as an apologia for Bolshevism and therefore largely useless.

Chamberlin, William Henry. The Russian Revolution, 1917–1921 . 2 vols. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1965.

Originally published in 1935, this work remains an extremely valuable source. The author, who covered Russia for the Christian Science Monitor from 1922 to 1933, was a skilled writer, objective observer, and careful researcher. Many specialists believe it has still not been surpassed as an overall history of the period. Volume 1, 1917–1918: From the Overthrow of the Czar to the Assumption of Power by the Bolsheviks . Volume 2, 1918–1921: From the Civil War to the Consolidation of Power .

Engelstein, Laura. Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War, 1914–1921 . New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

This broad narrative faults the tsarist regime for fomenting internal tensions as it fought World War I, most notably but not exclusively by targeting Jews, which weakened its authority during a time of crisis. Engelstein views the February Revolution as broadly democratic. It unfortunately was undermined by the Provisional Government’s inability to deal with the urgent problems caused by World War I and with disorder at home. Lenin and the Bolsheviks were fundamentally undemocratic and exploited the disorder in Russia to seize power in a coup d’état, after which they succeeded in applying brutal force, especially through the Cheka and Red Army, to crush their political opponents and social and ethnic groups resisting their rule during and immediately after the Civil War.

Figes, Orlando. A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891–1924 . New York: Penguin, 1998.

A panoramic narrative that draws on recently opened archives and numerous anecdotes with great effect. Figes argues, on the one hand, that Russia’s long history of serfdom and its autocratic traditions doomed the 1917 effort to establish a democratic regime and, on the other, that it was Bolshevism and Lenin’s policies after the seizure of power that put in place the basic elements of the Stalinist regime.

McMeekin, Sean. The Russian Revolution: A New History . New York: Basic Books, 2017.

McMeekin argues that Lenin’s improbable path to power was paved by errors on the part of Tsar Nicholas II, liberals who supported Russia’s entry into World War I and then proved to be inept as leaders of the Provisional Government, massive amounts of German money funneled to the Bolsheviks during 1917 in the hope that Lenin and his comrades would undermine Russia’s government and war effort, and Lenin’s fierce will to power and political skill. The ultimate Bolshevik victory was far from inevitable; it took a combination of blunders by others, Lenin’s skill and ruthlessness, and, not infrequently, pure luck for the Bolsheviks to be able to seize power in 1917 and then hold it in the battles and turmoil that followed through 1922.

Pipes, Richard. A Concise History of the Russian Revolution . New York: Vintage, 1996.

The author calls this volume a “précis” of his two massive, pathbreaking earlier volumes, The Russian Revolution ( Pipes 1990 , cited under the October Revolution and the Establishment of the Bolshevik Regime ) and Russia under the Bolshevik Regime ( Pipes 1994 , cited under the Civil War and Its Immediate Aftermath ). Pipes argues that with the coup of October 1917 fanatical intellectuals seized control of the upheaval of 1917 intent on establishing a socialist utopia, but, in the end, they reconstituted Russia’s authoritarian tradition in a new regime that laid the basis for totalitarianism. Excellent for advanced undergraduates, this volume covers the period from 1900 to 1924.

Read, Christopher. From Tsar to Soviets: The Russian People and Their Revolution . New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

A comprehensive but reasonably concise (three hundred pages) overview written from a revisionist social history perspective. As the subtitle suggests, Read stresses the activities and efforts of workers and peasants to defend their interests. While sympathetic to Lenin, Read also is critical of the Bolsheviks for suppressing popular movements after seizing power. Includes an extensive bibliography, which increases its value to undergraduates and graduate students.

Schapiro, Leonard Bertram. The Russian Revolutions of 1917: The Origins of Modern Communism . New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Schapiro argues that the Bolsheviks ruthlessly sabotaged the Provisional Government’s effort to lay the basis for democracy in Russia and, having seized power in a coup d’état, laid the basis for a totalitarian regime. A concise account that sums up the lifetime work of a distinguished historian of Soviet Russia. Excellent for undergraduates.

Shukman, Harold. The Russian Revolution . Stroud, UK: Sutton, 1998.

A short but up-to-date survey by the editor of The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the Russian Revolution ( Shukman 1988 , cited under Bibliographies and Reference Works ). This work concludes that Lenin prepared the way for Stalin. Suitable for undergraduates.

Smith, Stephen A. Russia in Revolution: An Empire in Crisis . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Smith argues that neither the collapse of tsarism nor the fall of the Provisional Government were preordained. The basic reason tsarism collapsed was that it was a barrier to modernizing forces in Russian society, but the severe additional social and economic strains imposed on Russia by World War I played a vital role in that collapse. The Provisional Government might have saved itself had it withdrawn from the war. The Bolshevik Revolution was driven by egalitarian and democratic ideals but was a failure since it produced a repressive and cruel society. The degeneration of the Bolshevik regime during the civil war was caused by the authoritarianism embedded in Leninist ideology and the desperate struggle the regime faced in its effort to survive. While Smith assigns considerable responsibility to Lenin for Stalin’s coming to power, he rejects the view that Stalinism was the inevitable outcome of the Bolshevik Revolution.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About International Relations »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Theories of International Relations Since 1945

- Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb

- Arab-Israeli Wars

- Arab-Israeli Wars, 1967-1973, The

- Armed Conflicts/Violence against Civilians Data Sets

- Arms Control

- Asylum Policies

- Audience Costs and the Credibility of Commitments

- Authoritarian Regimes

- Balance of Power Theory

- Bargaining Theory of War

- Brazilian Foreign Policy, The Politics of

- Canadian Foreign Policy

- Case Study Methods in International Relations

- Casualties and Politics

- Causation in International Relations

- Central Europe

- Challenge of Communism, The

- China and Japan

- China's Defense Policy

- China’s Foreign Policy

- Chinese Approaches to Strategy

- Cities and International Relations

- Civil Resistance

- Civil Society in the European Union

- Cold War, The

- Colonialism

- Comparative Foreign Policy Security Interests

- Comparative Regionalism

- Complex Systems Approaches to Global Politics

- Conflict Behavior and the Prevention of War

- Conflict Management

- Conflict Management in the Middle East

- Constructivism

- Contemporary Shia–Sunni Sectarian Violence

- Counterinsurgency

- Countermeasures in International Law

- Coups and Mutinies

- Criminal Law, International

- Critical Theory of International Relations

- Cuban Missile Crisis, The

- Cultural Diplomacy

- Cyber Security

- Cyber Warfare

- Decision-Making, Poliheuristic Theory of

- Demobilization, Post World War I

- Democracies and World Order

- Democracy and Conflict

- Democracy in World Politics

- Deterrence Theory

- Development

- Digital Diplomacy

- Diplomacy, Gender and

- Diplomacy, History of

- Diplomacy in the ASEAN

- Diplomacy, Public

- Disaster Diplomacy

- Diversionary Theory of War

- Drone Warfare

- Eastern Front (World War I)

- Economic Coercion and Sanctions

- Economics, International

- Embedded Liberalism

- Emerging Powers and BRICS

- Empirical Testing of Formal Models

- Energy and International Security

- Environmental Peacebuilding

- Epidemic Diseases and their Effects on History

- Ethics and Morality in International Relations

- Ethnicity in International Relations

- European Migration Policy

- European Security and Defense Policy, The

- European Union as an International Actor

- European Union, International Relations of the

- Experiments

- Face-to-Face Diplomacy

- Fascism, The Challenge of

- Feminist Methodologies in International Relations

- Feminist Security Studies

- Food Security

- Forecasting in International Relations

- Foreign Aid and Assistance

- Foreign Direct Investment

- Foreign Policy Decision-Making

- Foreign Policy of Non-democratic Regimes

- Foreign Policy of Saudi Arabia

- Foreign Policy, Theories of

- French Empire, 20th-Century

- From Club to Network Diplomacy

- Future of NATO

- Game Theory and Interstate Conflict

- Gender and Terrorism

- Genocide, Politicide, and Mass Atrocities Against Civilian...

- Genocides, 20th Century

- Geopolitics and Geostrategy

- Germany in World War II

- Global Citizenship

- Global Civil Society

- Global Constitutionalism

- Global Environmental Politics

- Global Ethic of Care

- Global Governance

- Global Justice, Western Perspectives

- Globalization

- Governance of the Arctic

- Grand Strategy

- Greater Middle East, The

- Greek Crisis

- Hague Conferences (1899, 1907)

- Hierarchies in International Relations

- History and International Relations

- Human Nature in International Relations

- Human Rights

- Human Rights and Humanitarian Diplomacy

- Human Rights, Feminism and

- Human Rights Law

- Human Security

- Hybrid Warfare

- Ideal Diplomat, The

- Identity and Foreign Policy

- Ideology, Values, and Foreign Policy

- Illicit Trade and Smuggling

- Imperialism

- Indian Perspectives on International Relations, War, and C...

- Indigenous Rights

- Industrialization

- Intelligence

- Intelligence Oversight

- Internal Displacement

- International Conflict Settlements, The Durability of

- International Criminal Court, The

- International Economic Organizations (IMF and World Bank)

- International Health Governance

- International Justice, Theories of

- International Law, Feminist Perspectives on

- International Monetary Relations, History of

- International Negotiation and Conflict Resolution

- International Nongovernmental Organizations

- International Norms for Cultural Preservation and Cooperat...

- International Organizations

- International Relations, Aesthetic Turn in

- International Relations as a Social Science

- International Relations, Practice Turn in

- International Relations, Research Ethics in

- International Relations Theory

- International Security

- International Society

- International Society, Theorizing

- International Support For Nonstate Armed Groups

- Internet Law

- Interstate Cooperation Theory and International Institutio...

- Interviews and Focus Groups

- Iran, Politics and Foreign Policy

- Iraq: Past and Present

- Japanese Foreign Policy

- Just War Theory

- Kurdistan and Kurdish Politics

- Law of the Sea

- Laws of War

- Leadership in International Affairs

- Leadership Personality Characteristics and Foreign Policy

- League of Nations

- Lean Forward and Pull Back Options for US Grand Strategy

- Mediation and Civil Wars

- Mediation in International Conflicts

- Mediation via International Organizations

- Memory and World Politics

- Mercantilism

- Middle East, The Contemporary

- Middle Powers and Regional Powers

- Military Science

- Minorities in the Middle East

- Minority Rights

- Morality in Foreign Policy

- Multilateralism (1992–), Return to

- National Liberation, International Law and Wars of

- National Security Act of 1947, The

- Nation-Building

- Nations and Nationalism

- NATO, Europe, and Russia: Security Issues and the Border R...

- Natural Resources, Energy Politics, and Environmental Cons...

- New Multilateralism in the Early 21st Century

- Nonproliferation and Counterproliferation

- Nonviolent Resistance Datasets

- Normative Aspects of International Peacekeeping

- Normative Power Beyond the Eurocentric Frame

- Nuclear Proliferation

- Peace Education in Post-Conflict Zones

- Peace of Utrecht

- Peacebuilding, Post-Conflict

- Peacekeeping

- Political Demography

- Political Economy of National Security

- Political Extremism in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Political Learning and Socialization

- Political Psychology

- Politics and Islam in Turkey

- Politics and Nationalism in Cyprus

- Politics of Extraction: Theories and New Concepts for Crit...

- Politics of Resilience

- Popuism and Global Politics

- Popular Culture and International Relations

- Post-Civil War State

- Post-Conflict and Transitional Justice

- Post-Conflict Reconciliation in the Middle East and North ...

- Power Transition Theory

- Preventive War and Preemption

- Prisoners, Treatment of

- Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs)

- Process Tracing Methods

- Pro-Government Militias

- Proliferation

- Prospect Theory in International Relations

- Psychoanalysis in Global Politics and International Relati...

- Psychology and Foreign Policy

- Public Opinion and Foreign Policy

- Public Opinion and the European Union

- Quantum Social Science

- Race and International Relations

- Rebel Governance

- Reconciliation

- Reflexivity and International Relations

- Religion and International Relations

- Religiously Motivated Violence

- Reputation in International Relations

- Responsibility to Protect

- Rising Powers in World Politics

- Role Theory in International Relations

- Russian Foreign Policy

- Russian Revolutions and Civil War, 1917–1921

- Sanctions in International Law

- Science Diplomacy

- Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), The

- Secrecy and Diplomacy

- Securitization

- Self-Determination

- Shining Path

- Sinophone and Japanese International Relations Theory

- Small State Diplomacy

- Social Scientific Theories of Imperialism

- Sovereignty

- Soviet Union in World War II

- Space Strategy, Policy, and Power

- Spatial Dependencies and International Mediation

- State Theory in International Relations

- Status in International Relations

- Strategic Air Power

- Strategic and Net Assessments

- Sub-Saharan Africa, Conflict Formations in

- Sustainable Development

- Systems Theory

- Teaching International Relations

- Territorial Disputes

- Terrorism and Poverty

- Terrorism, Geography of

- Terrorist Financing

- Terrorist Group Strategies

- The Changing Nature of Diplomacy

- The Politics and Diplomacy of Neutrality

- The Politics and Diplomacy of the First World War

- The Queer in/of International Relations

- the Twenty-First Century, Alliance Commitments in

- The Vienna Conventions on Diplomatic and Consular Relation...

- Theories of International Relations, Feminist

- Theory, Chinese International Relations

- Time Series Approaches to International Affairs

- Transnational Actors

- Transnational Law

- Transnational Social Movements

- Tribunals, War Crimes and

- Trust and International Relations

- UN Security Council

- United Nations, The

- United States and Asia, The

- Uppsala Conflict Data Program

- US and Africa

- US–UK Special Relationship

- Voluntary International Migration

- War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714)

- Weapons of Mass Destruction

- Western Balkans

- Western Front (World War I)

- Westphalia, Peace of (1648)

- Women and Peacemaking Peacekeeping

- World Economy 1919-1939

- World Polity School

- World War II Diplomacy and Political Relations

- World-System Theory

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- The Russian Revolution

What is the Russian Revolution?

The Russian Revolution plays a vital role in World history and had a huge impact not only on Russia but also in other regions as well. It led to the formation of the Soviet Union later which was the first socialist state of the world. Here, we will be covering the Russian Revolution in detail and it's related to all the concepts and events as well which will help you to understand this major event in world history.

In this, we will cover the series of major events that led to this revolution, its causes, and the effects of this revolution, etc. We hope these notes will help you in your studies and will increase your knowledge about historical events as well.

Meaning of Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution took place in the year 1917 when raging workers and peasants raised their voices against the autocratic rule of Czars which ended with the formation of the new government headed by Vladimir Lenin.

Series of Events

The various series of events that actually lead to the occurrence of this revolution are discussed below:

The Revolution of 1905

The industrial revolution came to Russia with a lot of changes such as social and political. The population was increasing in urban cities such as St. Petersburg and Moscow. Such an increase in the population was becoming a problem for the country due to the limited food supply, economic crisis, mismanagement and damages caused by the wars.

Due to the shortage of food supply, the people marched towards the Winter Palace of Nicholas II on Jan 22, 1905 as they wanted to deliver a petition to him. This petition included reforms like - providing better working conditions to all along with an eight-hour workday. But as soon as the crowd entered the palace, the troops started firing at them. This event is known as the Bloody Sunday Massacre. This massacre fueled the Russian revolution of 1905 to a great extent.

The workers went on a number of strikes which were further deteriorating the Russian Economy. Nicolas agreed to bring reforms which were known as October Manifesto but later he dissolved the Russian Parliament. Nothing specific or significant was brought out of this revolution of 1905 but it sparked anger inside the people.

Effects of World War I

Russia did not have a modernised army at that time, and World War I was disastrous for Russia.

Germany seized the important regions of Russia which led to an increase in food shortage and economic problems.

Tsar Nicholas II himself took part in the war and left his wife to take care of the government. But the Russian population were against her for being of German heritage.

A lot of Russian people lost faith in the government which was seen as a revolution in the coming years.

The Revolution of 1917

The Revolution of 1917 can be divided into the following parts and events:

February Revolution

This revolution started on March 8, 1917. Russia used the Julian calendar at that time, according to which, the date of the revolution was February 23.

The raging protestors came to the streets of St. Petersburg due to severe food shortages and were joined by Industrial workers as well. They were clashing with the police and they failed to stop the uprising crowd even after the firing on March 11. A new provisional government was formed by the Parliament of Russia on March 12 and Nicholas II abdicated the throne. This new government was formed under Alexander Kerensky and he established the Statute of rights. But he continued the war, though the opposition was against it, which eventually worsened the economic conditions of Russia and led to more scarcity of food supply. Food riots were being seen in the cities.

However, the February Revolution was a mass movement. It did not necessarily reflect the aspirations of the majority of Russians because it was confined to the metropolis of Petrograd. However, the majority of those who rose to power after the February Revolution, both in the Provisional Government (the temporary government that replaced the tsar) and the Petrograd Soviet (a powerful local council representing workers and soldiers in Petrograd), favoured a democratic form of government.

October Revolution

It occurred on November 6 or 7 of 1917. As per the Julian Calendar, it occurred on October 24 and 25, that's why it is known as the October Revolution.

The communist revolutionaries led a coup against the government of Kerensky which was led by Vladimir Lenin. The new government was established under Lenin which was formed of a council consisting of soldiers, workers, and peasants. In this way, the World's first communist state was established with Lenin as the head of Russia as a whole. It was basically the communist revolution in Russia. But the problems of Russia did not end there. It had to face the Civil War and the Cold War in the coming years.

After October, the Bolsheviks understood that they couldn't keep power in an election-based system without surrendering their beliefs and sharing power with other parties. As a result, in January 1918, they openly abandoned the democratic process and declared themselves representatives of a Proletariat Dictatorship. In response, in the summer of that year, the Russian Civil War erupted, lasting long into 1920.

Causes of the Russian Revolution

The situation in Russia at that time was the major cause of the Russian revolution . There were several reasons for these unbalanced situations which are mentioned below which help you to understand what caused the Russian revolution:

The shortage of food supply, the effects of the Blood Sunday Massacre, and World War I on Russia were some of the major reasons for this revolution.

Autocracy was one of the major reasons that led to this revolution. Czar Alexander II became famous in Russia when some reforms were brought by him. But the successors after him became very autocratic such as Czar Alexander III and Czar Nicholas II. During their ruling period, various political parties lost their powers such as Meer, Jemstvo, and Duma. There was already unrest in the society and their policies and these actions fueled the existing issues. Thus, the autocratic rule of the Czars became one of the major reasons.

Czar Alexander III and his son Czar Nicholas II followed the policy of Russification of all the systems. Nicholas II declared " One Czar, One Church, and One Russia ". Only the catholic religion and the Russian language were introduced as per this policy. Even the Russian language was introduced in non-Russian regions as well such as Poland, Lithuania, Finland, and others. This policy created big unrest in Russia.

The society of Russia was very unbalanced at that time. It consisted of two classes namely the rich and the poor. The rich included all the nobles, feudal lords, and wealthy people whereas the poor class consisted of labourers, peasants, serfs, etc. People from every stratum of Russian society were quite antagonised by the situation. For example, the feudal lords lost their lands, political parties lost their powers, and labourers were pissed off because of low salaries, etc.

A suitable environment for the revolution was created by the rise and activities of Nihilism which influenced the Russian Revolution in 1917. Their main aim was only to destroy the rule of Czars. Their preachers came to destroy the existing system of Czars, the social and religious faith, and the creation of a new world. Their organisations were doing activities to influence the people against the Czars and their system.

The Industrial Revolution also influenced Russian Revolution. Various Russian workers were involved in the construction of the railways of Trans-Siberia and Trans-Caspain and the construction of these railways led to the development of various factories and Industries in Russia. The rise of consciousness among the labourers led to the dream of getting the country free from the autocratic rule of the Czars.

Consequences of Russian Revolution

The various consequences of the Russian Revolution are mentioned below:

The formation of the new government of the Bolshevik Party under Lenin, which was later known as the communist party.

The formation of the secret police which was known as Cheka by the Bolsheviks after the revolution helped Lenin to establish his powers in Russia.

Distribution of the farmland to the farmers and factories to the workers.

Nationalisation of the banks and formation of the council at a national level to run the economy.

Russia pulled itself out of World War I with the treaty of Brest - Litovsk.

The end of the rule of Czars with the execution of Nicholas II, his wife, and children.

Cruel methods were adopted by Lenin for both criminals and political prisoners.

A decrease in industrial production was seen and as a result, the majority of the skilled workers fled the country.

The civil war from 1918 to 1920.

Did You Know?

The October Revolution is also known as the Bolshevik Revolution.

The names of main leaders of the Bolshevik Party were Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky. Joseph Stalin got power after consolidation and forcibly throwing out Leon Trotsky after the death of Lenin in 1924.

Additional Information

The Cheka which was also known as Vecheka was a security agency or sometimes called a secret police agency of the Bolsheviks which was formed after the October Revolution in 1917. It worked as a shield and sword for the new system and government and to fight against the other revolutionaries. It used to operate on its own and outside the law. It was the short name of the actual Russian name i.e Chrezvychainaia Komissiia means the Extraordinary commission and its first leader was Felix Dzerzhinsky.

Thus, here we have covered the Russian Revolution and its related concepts in detail. The Russian Revolution took place in the year 1917. We have learned about the series of events that led to the occurrence of this revolution, such as what caused the Russian Revolution, what were its consequences, what was Cheka in Russia after the revolution, etc.

These notes will be helpful for you to understand one of the major events of history, which substantially impacted world history during that time. It will also provide you with a brief idea of the international scenario with regard to world economics and politics during World War I, the Russian Civil War, the Cold War, and more.

FAQs on The Russian Revolution

1. What Were the Causes of the Russian Revolution?

There were many reasons for the occurrence of the Russian revolution. The poor economy and food shortages were some of the major causes as well as the autocratic rule of the Czars. The policies and actions of the Czars affected society. The participation of Russia in World War I further deteriorated its conditions and shortage of food. Society was highly unbalanced at that time and the event of bloody Sunday sparked the unrest. Society was not happy and the economy of the country was deteriorating day by day.

2. Write a Short Note on the Russian Revolution

The Russian revolution occurred on November 6 or 7of 1917. As per the Julian Calendar, it occurred on October 24 and 25, that's why it is known as the October Revolution. The communist revolutionaries led a coup against the government of Kerensky which was led by Vladimir Lenin. The new government was established under Lenin which was formed of a council consisting of soldiers, workers, and peasants. Distribution of the farmland to the farmers and factories to the workers was being done. Nationalization of the banks and formation of the council at a national level to run the economy was also being done by the new government with a lot of other reforms but the problems did not end there and Russia had to face more troubles later.

3. What factors contributed to the Tsarist regime's demise in 1917?

Most labour unions and industry committees were ruled illegal after 1905. Political action was governed by a set of rules. Because he did not want his authority and abilities to be questioned, the Tsar immediately dismissed the first two Dumas. Conservative lawmakers dominated the third Duma. The monarch began making unilateral decisions without consulting the Duma during World War I.

On the instructions of the Tsar, enormous swaths of agricultural areas were burned and structures destroyed when Russian forces were fleeing from the battle. The fight has also claimed the lives of millions of soldiers. The vast bulk of the population were peasants, and the land was controlled by a few wealthy individuals. All of these causes contributed to the development of the revolution and the fall of the Tsarist monarchy.

4. What were the most significant reforms made by the Bolsheviks following the October Revolution?

By November 1917, industries and banks had been nationalized, and the government had taken over ownership and administration.

The nobility's land was proclaimed communal property, and peasants were empowered to seize it.

Bolsheviks compelled the split of huge mansions according to family needs in the cities.

The use of aristocratic titles was outlawed.

The troops and authorities were given new uniforms.

The Russian Communist Party was renamed after the Bolshevik Party (Bolshevik)

The Bolsheviks held elections for the constituent assembly, but they did not win a majority, and the legislature rejected the Bolshevik plans, prompting Lenin to disband the parliament.

The Russian Congress of Soviets became the country's Parliament. Russia has devolved into a one-party state.

A nation must think before it acts.

- America and the West

- Middle East

- National Security

- Central Asia

- China & Taiwan

- Expert Commentary

- Directory of Scholars

- Press Contact

- Upcoming Events

- People, Politics, and Prose

- Briefings, Booktalks, and Conversations

- The Benjamin Franklin Award

- Event and Lecture Archive

- Intern Corner

- Simulations

- Our Mission

- Board of Trustees

- Board of Advisors

- Research Programs

- Audited Financials

- PA Certificate of Charitable Registration

- Become a Partner

- Corporate Partnership Program

Causes of the Russian Revolution

PA Social Studies Standards Standard – 5.1.W.F

Evaluate the role of nationalism in uniting and dividing citizens.

Standard – 5.2.W.B

Analyze strategies used to resolve conflicts in society and government.

Standard – 6.3.W.D

Analyze how conflict and cooperation among groups and organizations have influenced the history and development of the world.

Standard – 6.4.W.C Compare the role groups and individuals played in the social, political, cultural, and economic development throughout world history.

1. Students will examine the Russian Revolution and the development of Marxist ideology under Lenin and Stalin. 2. Students will describe and explain the causes of the Russian Revolution. 3. Students will use a technological tool to explain one cause of the Russian Revolution.