Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 02 January 2024

Making and interpreting: digital humanities as embodied action

- Zhiqing Zhang 1 ,

- Wanyi Song 2 &

- Peng Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5087-2112 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 13 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1690 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

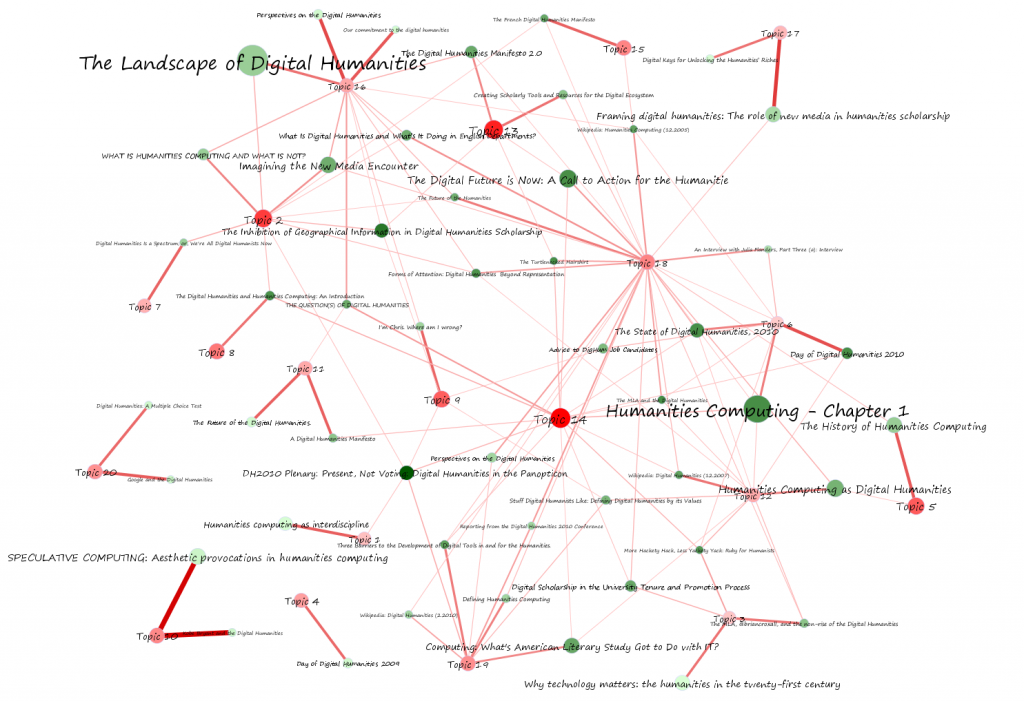

- Complex networks

- Cultural and media studies

Digital technology has created new spaces, new realities and new ways of life, which have changed the way people perceive and recognise the world. In particular, the production, dissemination and reception methods of literature and art have been impacted upon significantly. Acknowledging humanities scholars have been engaged in conducting research while theorising and debating what Digital Humanities (DH) is/is not in the past two decades, this study extends current thought on DH by connecting it with the concept of sociological body, particularly thinking bodily interaction in relation to digital technologies in DH practice. The increasingly deepening integration of body and technology allows DH practice to become an event, in which embodied bodily action is situated in the (digital) environment that impacts on knowledge production. Acknowledging contemporary discourse regarding the two waves of DH, the article pays attention to the presence of the body whereby DH practice is bodily inclusive as mediated by digital technology, in which bodily interaction in producing knowledge via technologies reflects haptic experience and cultural constraints upon the sociological body. At the same time, technologies are not an innocent medium but an active contributor, so much so that we claim knowledge produced with the substantial involvement of digital technology is ‘digitised’ knowledge, as our critical interpretation towards a possible DH 3.0 practice that is subject to the core value of the humanities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Evolution of mediated memory in the digital age: tracing its path from the 1950s to 2010s

Digital transformation of mental health services

Raymond R. Bond, Maurice D. Mulvenna, … John Torous

Parents’ digital skills and their development in the context of the Corona pandemic

Badr A. Alharbi, Usama M. Ibrahem, … Sameh F. Saleh

Introduction

Embracing the current academic tide that favours interdisciplinary research as a means to break boundaries and achieve the integration of disciplines, Harpham ( 2006 ), the former director of the National Humanities Center in U.S., notes that questions formerly reserved for the humanities are being approached by scientists in various disciplines, such as cognitive science, cognitive neuroscience, artificial life, and behavioural genetics. Acknowledging digital technologies have energised humanities research, the emerging field of Digital Humanities (DH) is a response to the transformation of humanities in the digital age. It is worthwhile reminding ourselves that the essential problem of humanity in a computerised age remains the same as it has always been; that is, the problem of not solely how to be more productive, more comfortable, more content, but also how to be more sensitive, more proportionate, more alive (Cousins, 1966 ). DH has interdisciplinary and even anti-disciplinary attributes since its inception, Footnote 1 even though the very definition of DH is still being debated. This article draws on the concept of the sociological body in interdisciplinary terms by thinking bodily embodiment and haptic experience in relation to DH practice whereby the increasing integration of body and technology allows DH to be seen as an event; that is to say, as an embodied body in a digitally situated environment forming information and producing knowledge.

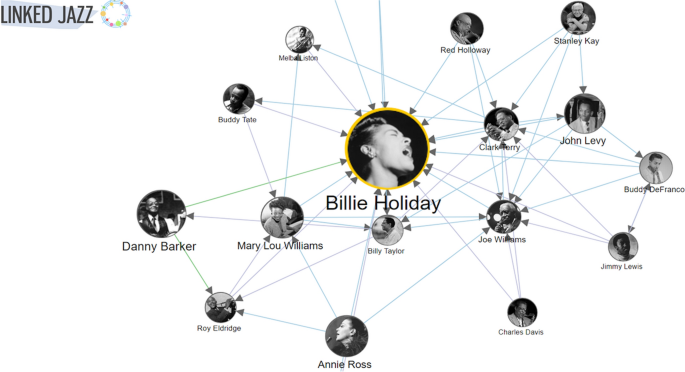

Digital Humanities, initially called Humanities Computing, is broadly humanities-based field involving scholars in the research areas of literary studies, history, media studies, musicology, and many other fields which benefitted from bringing computing technologies into the study of humanities materials. DH originated in the pursuit of more accurate objectivity and comprehensiveness in research beyond traditional methods in the humanities, such as McGann’s ( 2013 ) study on library research on how digital technologies can provide easier access to primary materials and increase the speed of searching and comparison. In cultural analytics, research can be conducted through the use of quantitative computational techniques which offer massive amounts of literary or visual data analysis (Manovich and Douglas, 2009 ), allowing for the visualisation of large amounts of data where patterns emerge. Acknowledging humanistic scholarship is either in the traditionalist mode of individual sensibility or in the contemporary mode of social critique, DH articulates a different understanding of the nature of meaning, which is “to speak to the larger patterns and deeper meanings of human experience…[and is] a modern technological incarnation” (Fuller, 2020 , 260, 262). The well-known example is the difference between distant readings versus close readings of texts in literary study (Moretti, 2013 ).

DH scholars are those who either adopt digital technologies in studying questions that are traditional to the humanities, or use values of traditional humanities in questioning digital technologies. Nevertheless, humanities research is increasingly being mediated through digital technology. Acknowledging efforts to theorise DH as a new discipline in which the debate on the boundary of DH is continuing and has not been settled over the past two decades, DH is intimate to humanities research, given the increasing number of research done in/via ‘charticles’, or journalistic articles that combine text, image, video, computational applications and interactivity in the humanities (Stickney, 2008 ). Kirschenbaum ( 2012 ) notes that various DH scholarly approaches reflect their interest in making in DH by, for example, creating digital archives, digital visualisation and possible new digital methods for (re)exploring social and cultural concerns. McGann notes that the main value of DH work resides in the creation, migration, or preservation of cultural materials ( 2008 , 2014 ). Meanwhile, other scholars emphasise interpretive work as a critical reflection, such as the interpretation of DH production in terms of its social and cultural impact. Although the digital approach can lead to a different understanding of large-scale cultural, social and political processes, it is actualised in concrete actions and reactions of operating digital technologies reflected as decision making on, and interpretation of, the inclusion/exclusion of data, for example. Thinking bodily interactions, humanities and digital technology altogether is to focus on the making in practice with the presence of body and haptic knowledge. In other words, technologies are not innocent; the knowledge produced with the substantial involvement of digital technology is ‘digitised’ knowledge, thereafter the bodily digital is formed.

While Manovich questions what culture is after it has been “softwarized” ( 2009 ), this article acknowledges, following Berry, that “understanding digital humanities is in some sense then understanding code, and this can be a resourceful way of understanding cultural production more generally” (2011, 5). In other words, the computer together with software is “the new engine of culture” (Manovich, 2013 , 21) and DH is where it takes effect. The article uses an interdisciplinary approach to think through the everyday use of digital technology in professional practice and research activity as an embodied act, in which one’s bodily action can be the critical interpretation in the process of knowledge making, such as bodily movement in manipulating digital technologies. Bodily making is critical interpretation. The mingling between physical and virtual space is ever strong, enabled and accelerated by the development of technology, such as immersive bodily experience by TeamLab. There is no longer a need to divide actual and virtual spaces, but rather take the body in action that is acting, reacting and crossing spaces constantly while knowledge is produced, in which ‘digitised’ embodiment and the bodily digital are formed. Rethinking DH via the concepts of situatedness and embodied bodily actions is to think DH practice as dynamic event, being in the world and beyond a discipline.

This article argues that DH practice is an embodied act in experiencing the impact of digital technology upon bodies, whereby new bodily knowledge, inclusive of the haptic and the visual, emerges in the process of action and reaction in collaboration with digital tools across actual and virtual space. The article, via analytical discussion, conceptualises and sees digital technology as not an innocent tool or neutral medium, but rather a series of concrete actions and reactions of bodily interactions with actuality and virtuality, where the knowledge co-produced is ‘digitised’ knowledge. The article, therefore, begins with a literature review that revisits the core value of traditional humanities, followed by stating the changes brought about by virtual reality, and then presents various concerns and some conceptual analysis of distinct and diverse aspects of scholarly works in the two waves of DH. The research method descripts the ensuing analytical discussion built on from previous works in terms of the concepts of situatedness and embodiment as a theoretical lens. The findings are elaborated on and theorised in the penultimate section conceptualising the bodily inclusive in DH practice by thinking bodily interaction, humanities, and digital technology altogether to produce ‘digitised’ knowledge via two case analyses.

Literature review

Criticalness–core value of humanities.

Criticalness, along with debate, pluralism and inquiry for instance, is the essence of the humanities, and the role of humanities scholars is crucial in the production and interpretation of cultural materials. There is a need to identify the values in DH which Spiro proposes are openness, collaboration, experimentation, collegiality and connectedness, and diversity and experimentation (2012a; 2012b). How the values of DH can be harnessed to enhance the humanities can be thought through in various ways; however, what is relevant to this article is in terms of bodily actions. Despite decades-long debate on DH’s role, value and relation to the humanities, much humanities research relies too much on digital technologies while critical awareness has weakened. For example, text can be quantified by forming conceptual indicators, yet the meaning temporarily fixed by researchers has limited explanatory power, thus highlighting the lack of criticism. Footnote 2 The humanistic pursuit of knowledge, which concerns subjective consciousness and is related to the viewer’s sensibility, cannot be processed by numbers themselves. In other words, in the current context of academic research ‘to have numbers’, scholars are concerned that art and literature works, for example, may only have data value after electronic transformation (Zhang and Zhang, 2021).

Becoming virtual

American scholar Lippmann proposed a concept in 1922 called “pseudo-environment” in his far-reaching book Public Opinion . Lippmann believes that newspapers, magazines and other media reconstruct a reality, which he calls a pseudo-environment. This pseudo-environment is an information environment, not an objective response to the real environment, but a new world created by the media, which shapes the audience’s picture of the real world in their minds (Lippmann, 1922 ). The original meaning of pseudo in English contains the meaning of ‘false’. Lippmann believes that the reality created by the media is not the reality that is faithfully reflected, but the reality constructed by the media organisation and the media organisation system; as long as the audience believes it, they exist in it. With the change of the media environment, the pseudo-environment, constructed by centralised media, such as newspapers and magazines, is a thing of the past. Instead, it has been replaced by the virtual environment based on the Internet. The virtual space is visual, distributed, and interactive involving user participation. While the pseudo-environment includes the participation of media organisations and ‘false’ elements in it, there is no such question of authenticity in the virtual space; or in other words, the liquid and User-Generated Content (UGC)-based new reality redefine the question of what is true and what is false.

The pseudo-environment has been replaced by virtual reality. For example, American science fiction writer Neal Stephenson published a novel Snow Crash in 1992 in which he created a space that did not exist—Metaverse. The Internet era is a digital era, and the virtual era is a dynamic and image era composed of Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR) and Mixed Reality (MR). The visual space created by virtual reality does not exist in one’s imagination, nor is it completely real, but offers a kind of new bodily experience and existence independent of matter and consciousness. Therefore, the advent of this virtual era ensured and advanced by digital technologies has affected not only people’s lifestyles, such as shopping and travelling, but the way people perceive and recognise the world through bodily experience.

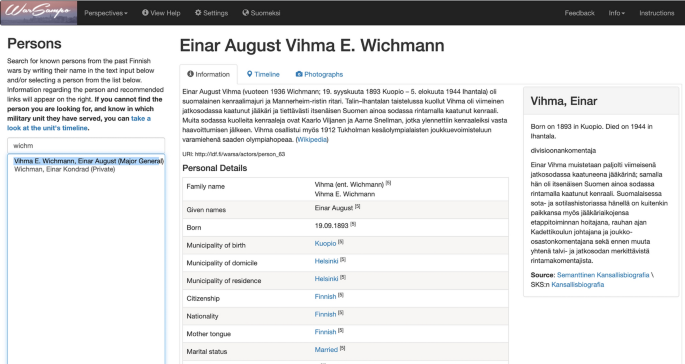

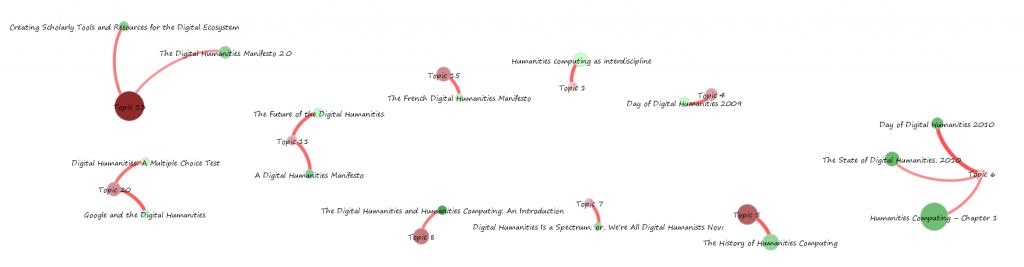

Digital humanities

Digital Humanities (DH) research stems from the pursuit of objectivity and comprehensiveness in the research of the humanities (Piper, 2016 ). Based on a large amount of data, it attempts to conduct quantitative analysis on the subjectivity of the humanities and obtain some factual conclusions on this basis. Digital technologies have furthered this type of research and redefined DH as a response to the transformation of the humanities in the digital age. It is generally believed that DH is a field of academic activities where computer or digital technology intersects with the humanities. The pioneer of digital humanities recognised by academic circles is Roberto Busa, an Italian Jesuit priest. According to Jones ( 2016 ), Busa in collaboration with IBM in 1949 made an index consisting of more than 10 million words from the Latin works of St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274). This epoch-making achievement combined text and calculation for the first time, which greatly promoted the application of computers in the field of linguistics. In the 1960s, statistics began to join in, the most representative of which was the new research field of ‘authorship research’, which classified author texts by counting the frequency of word occurrence or the number of word occurrences, because each author is usually considered to have unique—yet very subtle—stylistic differences in the use of common words. A typical example of this is the study of the authorship of The Federalist Papers (1787–1788). Footnote 3 The first academic journal in DH, entitled Computers and the Humanities , was launched in 1966.

William Pannapacker declared the arrival of digital humanities at the annual meeting of Modern Languages Association (MLA) conference in 2009, which is the largest and most important association in the field of humanities in the United States. Many discussions have revolved around DH ever since, focussing on three core features. Firstly, DH digitises vast experiential materials and establishes (or utilises existing) databases to lay the foundation for analysis; secondly, it introduces statistical methods, conducts data mining, compares the significant characteristics of quantitative indicators, or discovers certain patterns, trends and regular phenomena; and thirdly, there is diversification and dynamic presentation of the research results.

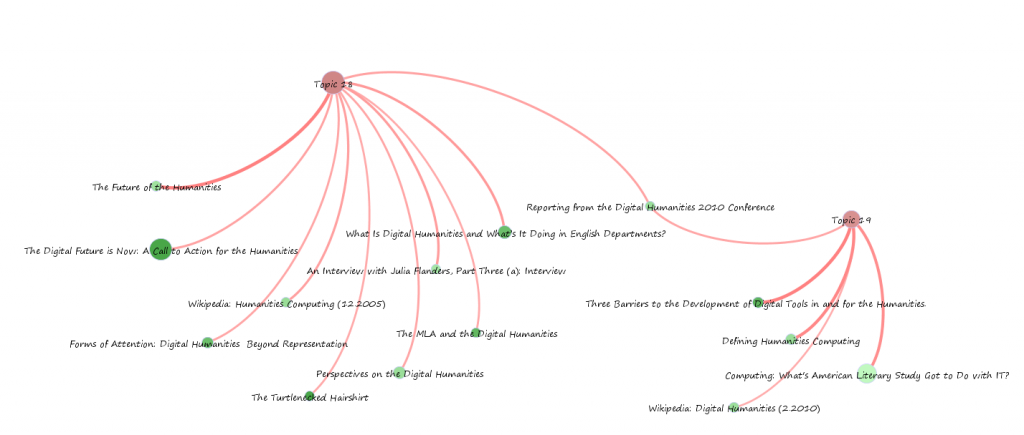

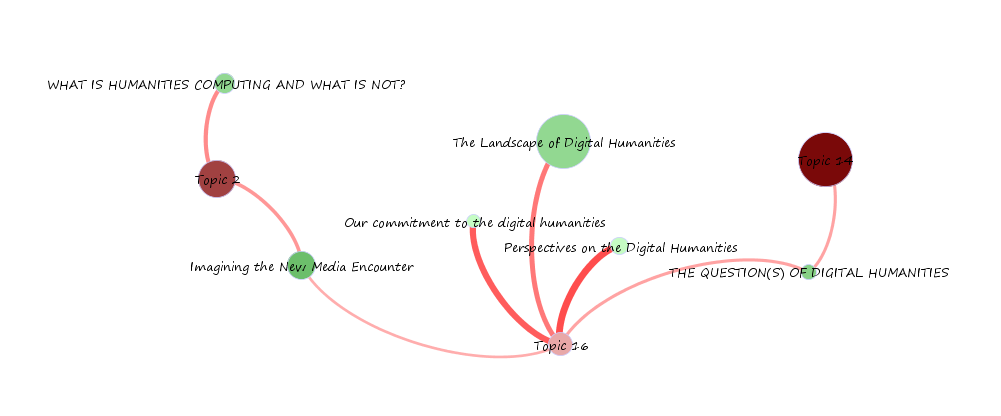

The first wave

There are two widely known waves in DH. The first wave took place in the late 1990s focussing on digitisation projects. Moretti ( 2000 ) believes that to study world literature, neither ‘close reading’ nor comparative methods should be used, but a new ‘distant reading’ mode should be used, that is, using databases and quantitative methods, to explain the category factors and formal elements in the overall or broader text system. For example, by using a case study on published novels, Moretti exemplifies that the excessive number of novels cannot be understood by traditional methods in the humanities, but rather it is “a collective system, that should be grasped as such, as a whole” (2005/2007, 3–4). The impact of the first wave included data mining or large corpus processing and distant reading, which brought new insights and techniques into the humanities, as distinct from traditional methods such as close reading and textual analysis. The first wave was later summarised by Schnapp and Presner as “quantitative, mobilizing the search and retrieval powers of the database, automating corpus linguistics, stacking hypercards into critical arrays” (2009, 2). Previous discussions regarding the first wave resulted in many binary points of views, such as close reading versus distance reading, ‘panoramic’ collective view enabled by digital technology and big data versus individual intimate experience in traditional humanities, actual versus virtual, etc. Discussion regarding the binarism of digital technologies in humanities research seems to be diminishing with the arrival of the second wave of DH.

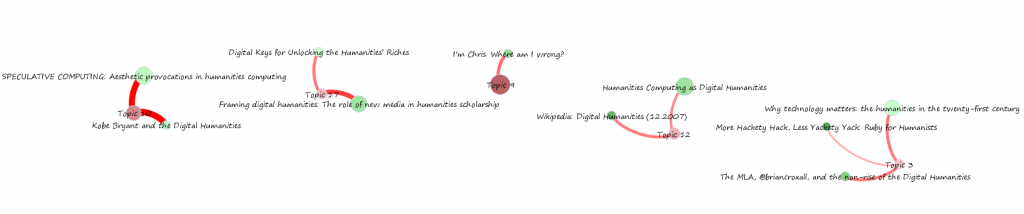

The second wave

The second wave called Digital Humanities 2.0 arrived in the late 2000s with more complexity and wider application in practice and theory; it “is deeply generative, creating the environments and tools for producing, curating, and interacting with knowledge that is ‘born digital’ and lives in various digital contexts…[and] introduces entirely new disciplinary paradigms, convergent fields, hybrid methodologies…” (Presner, 2010 , 68). Hayles notes that DH had emerged from “the low-prestige status of a support service into a genuinely intellectual endeavour with its own professional practices, rigorous standards, and exciting theoretical explorations” (2011, 46). Many scholars had recognised by then that DH is a new way of working with representation and mediation, such as Schreibman et al. ( 2008 ), Schnapp and Presner ( 2009 ), Berry ( 2011 ) and Hayles ( 2011 ); in Presner’s words, it is a new “Normal Humanities” (2010, 11). DH in general is a new scholarly method with its “focus on the identification of novel patterns in the data as against the principle of narrative and understanding” (Berry, 2011 , 13).

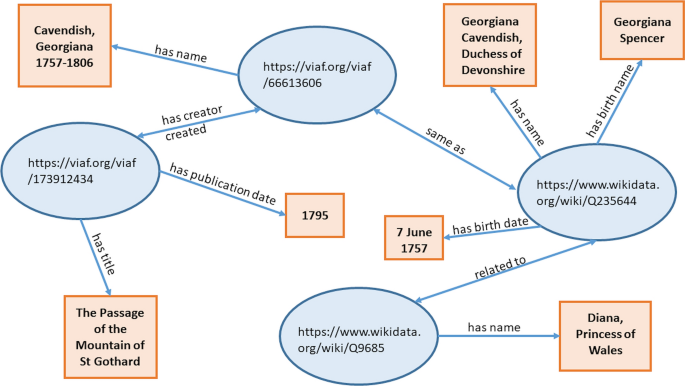

Schnapp and Presner note that the second wave is “ qualitative, interpretive, experiential, emotive, generative in character” (2009, 2, original emphasis). These characteristics of the second wave “harnesses digital toolkits in the service of the Humanities’ core methodological strengths: attention to complexity, medium specificity, historical context, analytical depth, critique and interpretation” (Schnapp and Presner, 2009 , 2). There are increasing number of scholarly practices across the humanities as shown in the examples below that reflect the characteristic applications, as well as the significance and impact of digital technology, in the second wave of DH. Before reviewing the three selected approaches in recent works of DH 2.0 that form the path to discussion on the importance of embodiment and haptic experience in this context, it is important to reiterate that this article acknowledges and extends upon the characteristics of DH 2.0 to propose a prospective on bodily action. The experiential, emotive and generative characteristics of DH 2.0 are every concrete bodily action actualised in the process of DH practice, while moving in and out of actual and virtual spaces, seeing the collective data through individual eyes, and conducting close reading on data from distance reading, etc. are rethought in terms of bodily action and lived experience. DH practice is bodily inclusive in which there is only bodily action to count on, a digital event as culturally embodied and spatially situated.

Recent research in DH 2.0 has addressed complexity, medium specificity, historical context, analytical depth, critique and interpretation, while many fields across the humanities have incorporated approaches and arguments from DH for their own core concerns. Of particular interest to this article, there are three selected approaches concerning cultural issues, minimising digital technologies in practice, and practicing in a situated space/place, which support the proposal for the bodily inclusive in DH practice that co-produces ‘digitised’ knowledge and becomes the bodily digital.

Firstly, concerns in traditional humanities involve digital technologies, such as the commitment of some DH scholars to antiracism and feminism discussions as well as Black studies. For example, Prince et al. ( 2022 ) call for a more equitable field based on the current challenging and difficult situation confronting DH Black scholars. Adams ( 2022 ) examines how Black fans use social media platforms to engage fandoms of contemporary Black popular cultural productions. Similar approaches in DH has been flourishing in cultural studies, gender studies, and minority/marginalised group studies in relation to topics such as colonialism (Alpert-Abrams and McCarl, 2021 ), feminist, queer and LGBTQ+ issues (Ketchum, 2020 ), exclusion of women and scholars of colour (Nowviskie, 2015 ), and how DH is reinforcing a gender gap in the field and a gendering of DH work itself (Wernimont, 2013 ; Olofsson, 2015 ; Mandell, 2016 ). The voices and opinions in the above groups across various studies are critical to understanding the social and cultural atmosphere and political climate, thereby forging a more inclusive path towards understanding society. The digital technologies engaged in the above research are seen as part of the social and cultural environment in facilitating the making of their qualitative comments as well as interpretations of their core concerns in the cultural domain.

Secondly, there is an enquiry about the necessity of using digital technologies, termed the concept of digital minimalism, or minimal computing according to Risam ( 2018 ). Gil ( 2015 ) questions “what do we need?” in an effort to reflect upon and recalibrate the increasing use of digital technologies. Wythoff ( 2022 ) notes that minimal computing focusses on “cultural practices rather than tools or platforms” and “prioritizes a humanist approach to technology”. Risam describes minimal computing as “a range of cultural practices that privilege making do with available materials to engage in creative problem-solving and innovation” (2018, 43). In actual practice, the concept is manifested as minimal design, maximum justice and minimal technical language (Sayer, 2016 ) to privilege wider access and openness to community. For example, Risam and Edwards ( 2017 ) practice minimal computing by embracing small data sets, local archives, and freely available platforms for creating small-scale digital humanities projects. Privileging making and shifting focus back on cultural practice in traditional thought, digital minimalism accommodates the impact of digital technologies and ensures wider access by reducing the use of high-tech and instead regarding digital technologies as merely tools and platforms. This approach is conscious of the body-tool relation and critiques the idea of ‘the more, or stronger, the better’. Despite partially disagreeing with digital minimalism’s strategy that seemingly has a sense of ‘withdrawal’ from, and reluctance towards, ever-growing digital technologies, we appreciate their thinking on making , which connects with bodily inclusive action in our argument. We thereby propose that the bodily inclusive in DH practices become digital events to embrace the ever-increasing use of digital technologies in everyday life. The full discussion on bodily embodiment in relation to digital technology is in the penultimate section of this article. Before that, we will outline the next approach concerning the DH lab/centre as a situated place/space that indirectly points to bodily actions taking place within, which is of interest to the article in terms of the emotive and generative sense of knowledge production/transfer in DH 2.0.

Thirdly, discussion on space and place is called situated research practice in DH (Oiva and Pawlicka-Deger, 2020 ), whereby research activities are typically undertaken in DH centres and laboratories in terms of ‘situatedness’. Many scholars argue that the DH lab/centre is more than a physical place. For example, based on a review of the ‘laboratory turn’ in the humanities, Pawlicka-Deger ( 2020 ) notes that the space and place of lab/centre has been conceptualised in relation to ways of thinking, communicating and working entailing new social practices and new research modes. There are five models of DH labs Footnote 4 that can be categorised and analysed to reflect the lab/centre as concept, initiative, and programme.

While the DH lab/centre is conceptually regarded as a problem-based project rather than a physical workspace, the emphasis is on collaboration, experimentation, and hands-on practices in the laboratorial space. That is to say, for example, “the manner in which the knowledge-transfer activities in DH communities are facilitated affects the knowledge they produce” (Oiva, 2020 ). Exploring the situatedness of DH lab/centre, Malazita et al. ( 2020 ) claim that “laboratory structures and cultures produce specific kinds of knowledge practitioners…[who] in turn produce and police the boundaries of legitimate and recognizable knowledge work…[a]ll of these productions are, in part, results of particular institutional and disciplinary positions”. Moreover, “knowledge is inseparable from the communities that create it, its context, structure, and the means with which it is produced and shared” (Oiva, 2020 ). Acknowledging the main idea of Oiva and Malazita et al. that it is important to understand the practices, structures, and the community underlying knowledge construction, we nonetheless argue there is also the presence of the body, which is culturally embodied and historically inherited, in the situated laboratorial space. Lived and immanent bodily interactions take place in the situated DH labs/centres and communities simultaneously while transferring/producing knowledge.

Bodily interaction actively constructs the DH lab/centre as a cultural space via the professional practice undertaken within as a dynamic process, an event of happening. Borrowing the concept of epistemic culture (Knorr Cetina, 1999 ), Malazita et al. ( 2020 ) point out that in terms of “the material and epistemic production of DH labs, their spaces, cultures, practices, and products…humanities scholars…must be produced as epistemic subjects through the interactions of their education, the objects, the field, and the documentary and critical writings about the objects”. To extend on this, movement in terms of the sociological body can add an extra lens to think through the situatedness of DH practice in a more complex and medium-specific way. The narrative of bodily movement is about historical context and analytical depth that is always engaged in critiques and interpretations.

Research method

The article proposes an alternative approach for DH practice as process-inclusive in the sense that bodily interaction, when operating or accommodating digital technologies while moving in and out of virtual and actual space for example, is itself critical and humane at a bodily level. The article builds on previous studies on embodiment (Liu, 2018 , 2022 ), actual and virtual space (Liu, 2020 ; Liu and Lan, 2020 , 2021 ) and bodily movement (Liu and Lan, 2021 ; Lan and Liu, 2023 ) to rethink bodily inclusive DH practice. After reviewing the discussion of DH 1.0 emphasising on the development of technology and analysis on cultural content, as well as of DH 2.0 with attention to complexity, medium specificity, historical context, analytical depth, critique and interpretation. Our proposal on the bodily approach in the process of knowledge making in understanding DH practice is particularly timely as the boundary, in terms of bodily experience, between actual and virtual space is increasingly blurred. In other words, the article predicts in the forthcoming Digital Humanities 3.0 wherein bodily accommodated digital technologies actively contribute to knowledge production in understanding the world.

The body, or the sociological body, has been extensively studied in a multitude of ways in sociological thinking and research by scholars such as Synnott ( 1993 ), Featherstone et al. ( 1991 ), Strathern ( 1996 ), Csordas ( 1994 ), Turner ( 1996 ), and Williams and Bendelow ( 1998 ); their intellectual contributions are discussed elsewhere and will not be repeated here. Since the body has been reconciled as “simultaneously a social and biological entity which is in a constant state of becoming” (Shilling, 1993 , 27), the body in this article is understood as a historically inherited and culturally embodied being (Liu, 2018 ) that is acted upon by institutions (Foucault, 1991 ). Bodily actions from everyday life—derived from the sociological concept of body techniques, or in Mauss’s term “the habitus” (1979, 101), which are “forms of embodied pre-reflective understanding, knowledge or reason…[that] distinguish and differentiate social groups” (Crossley, 2005 , 7–8) and have their own cultural interests and political motivations—are extended into the world of the virtual. Body technique is a “learned and incorporated skill” (Ravn, 2017 , 59), whereby the body first “act[s] to the skill qua thematized goal” and then acts “from” the skill (Leder, 1990 , 32) toward further goals. The body itself is in action to practice in DH research. The body in action, by exemplifying the disciplinary mechanisms or control in everyday society for example, is manipulating of, or being compromised by, digital technology; thereby, the bodily experience is impacted upon in ways of seeking, obtaining, selecting, analysing and interpreting data. Being subjective and critical in traditional humanities can be always present in DH, but co-produced with digital technologies.

Kinesics is the term coined in the study of bodily movements according to Birdwhistell ( 1952 ; 1970 ), which investigates and interprets nonverbal behavior (Ekman and Friesen, 1969 ), Footnote 5 such as facial expression (Raman and Singh, 2006 ), Footnote 6 gestures (Andersen, 1999 ), Footnote 7 posture (Pearse and Pearse, 2005 ; Patel, 2014 ), and bodily movements. Acknowledging studies conducted over the past decades with various emphasis and empirical parameters, bodily movement are taken as symbolic or metaphorical in social and cultural interaction. For example, body gestures (Kendon, 1981 ) and hand gestures (McNeill, 1992 ) are systemic and socially learned, Footnote 8 which touching behaviors and movements can express the internal state of a person of being arousal or anxiety (Andersen, 1999 ). The haptic experience of touching is tactile contact with oneself, objects, and others.

This article proposes a focus on the concrete actions of the body in practice mobilising/compromising digital technologies as an essential part of the research activity where new bodily experience emerges. The shift in focus to the bodily inclusive is timely in rethinking the current position of DH as being neither discipline nor interdiscipline. Instead, advanced digital technology, such as the forthcoming Web 3.0, is able to significantly narrow the boundary between virtual and actual bodily experience, whereby bodily inclusive DH practice can be seen as an event, a production itself; therefore, the embodied bodily movement is a critical response to research activities regardless of the research outcome. Humanities is the pursuit in which new knowledge is produced, and the anticipated Digital Humanities 3.0 is the process of experiencing in which new (digital) bodily experience is realised, thereby affecting the understanding of the world. In a parallel discussion, Fish ( 2012 ) notes, “Each reorganization (sometimes called a ‘deformation’) creates a new text that can be reorganized in turn and each new text raises new questions that can be pursued to the point where still newer questions emerge”, which implies that research is embedded in the ongoing process of (re)making and experimenting.

Therefore, moving away from debates concerning technology, method or criticalness etc., while embracing qualitative, interpretive, experiential, emotive and generative characteristics, thinking bodily action, humanities and digital technology altogether is to propose the situatedness of the bodily encounter in the process of making in the digital age. In this paradigm, the certainty of knowledge that researchers arrive at is not due to what things have been done but how things have been done upon every single bodily movement, wherein bodily experience is essential in knowledge making in the digital environment. Digital technology is more than a neutral medium, rather it has grown to actively contribute towards co-forming the realisation of the world. Two cases are examined to reflect DH practice as embodied action. The first is the practice of a fashion designer whose traditional garment making skills intertwine with digital technology resulting in new bodily experience and haptic knowledge in mixed realities. Footnote 9 The second reviews a research practice on an online community using data analysis in which the bodily inclusive proposes an alternative approach.

Digital Humanities 3.0 as embodied act: making, interpreting and criticalness

Kirschenbaum notes that DH is more akin to a common methodological outlook (2012), which perhaps downgrades the significance of DH and its potential to be a new space in comprehending and forming the world. Some scholars question whether the centre and the boundaries of DH remain amorphous (McCarty, 2016 ); Svensson ( 2016 ), for example, describes DH as being in a liminal state, that it is neither discipline nor interdiscipline. DH seems to have huge potentiality; however, at the same time, its promised future is continually delayed in which its highly anticipated impact has not yet been fully realised (Alvarado, 2012 ).

The role of humanities scholars always concerns the production and interpretation of cultural materials in constantly changing cultural and social environments, rather than focussing on technological progress (Fitzpatrick, 2010 ), which is also coherent with Earhart’s view that DH should engage theoretically with technology, not merely with the content of technologies (2012a; 2012b). Cong-Huyen ( 2015 ) and Parikka ( 2012 ), for example, mobilise critical theories to bridge the ‘natural’ progression of technology and critical thinking on cultural materials. This article argues that, on the premise of ever-strengthening digital technologies, bodily movement becomes the meeting point of the two, whereby immanent and irreducible bodily actions operate technologies in the ways to favour the latter’s own interest, while the operational technologies reinforce the users in perceiving the world, in which actions are taken in field study, searching for materials, visualising the research, and enhancing decision making, as well as accommodating various digital technologies in the process of knowledge making. Bodily movement is specific to the medium with attention paid to details and complexity, wherein the body is cultural and physical in its historical context, which in turn diversifies the understanding of DH 2.0 practice. Moreover, the bodily experience in everyday research practice could become prominent in and provide alternative ways of thinking to DH 3.0. The interaction between body and digital technologies in everyday experience determines what knowledge can be produced and how it is to be presented. Concrete actions determine bodily experience and subsequent understanding of the world, which are what humanities scholars work with, and are affected by and inseparable from. From everyday practice, new realisations emerge in bodily actions and reactions situated in the digital environment, some of which are immature, controversial or even handicapped, yet they actively contribute to the perception of the world.

Negroponte ( 1995 ) notes that digitalisation has created a new living space, and people in the digital age live more in the virtual space constructed by digital technology. What is emphasised here is that while people study, work and communicate in this space, regardless of whether it is actual, virtual or mixed, bodily actions are taking place to create new literature, art, history and even culture in the virtual interaction. After more than two decades later, the increasing integration of body and technology allows DH practice to become an event, in which the embodied body acts and reacts in a situated digital environment. Therefore, bodily actions itself is the process of knowledge making that leads to new realisation and ‘digitised’ knowledge.

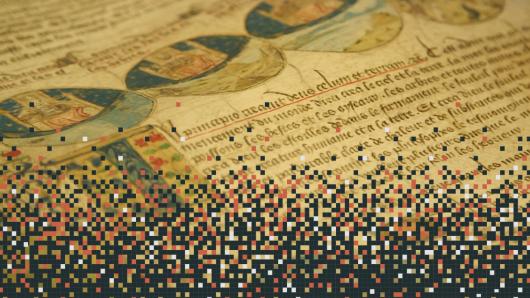

Narrowing the ‘gap’ – connecting body to DH in digital fashion design practice

The selected and synthesised historical trajectories of the growth of DH not only demonstrate the increasing impact of digital technologies upon everyday life, but also pave the way towards conceptualising the connection of DH to the body. The observable ever-strengthening technologies and deepening of everyday engagement have prompted the rethinking of the situated body in terms of DH. This brings the ideas of ‘digitised’ body, ‘digitised’ knowledge and embodiment into focus, especially given the high number of everyday experiences involving the mix of actual and virtual realities. The realisation of dematerialization does not entail embracing virtuality by abandoning materiality. But rather, dematerialisation reflects a new type of ‘digitised’ knowledge and embodiment in mixed reality. The everyday body can visually experience the simulated virtual space while the body remains situated in the actual environment in terms of haptic experience, for example.

The haptic, as a somatic sense of touch, has been studied extensively in the field of psychology with recent scholarship focusing on touch or non-visual senses (Classen, 1997 ; Stoller, 1997 ; Geurts, 2005 ; Howes, 2003 ; Feld, 2005 ; Paterson, 2007 ). Bodily actions are embodied, tactile and spatial experiences, that arise from touching and sensing via skin, for example, and provide a sense of immediacy for the body when interacting with actual space; it is “like a journey inward into the fibrous and synaptic entanglements of a diffuse nerve-muscle system” (Paterson, 2011 , 266). Bodily actions in a physical space combine several somatic senses, namely, the modalities of proprioception as the body’s muscular tension, kinaesthesia as the sense of the body’s movement, and vestibular sense as a sense of balance (Paterson, 2007 , 4). That is to say, apart from our visual perception, virtual space is also experienced and understood through our skin, such as through touch. Digital fashion designers in everyday practice, for instance, are visually immersed in the world of the virtual, and whose bodies have ‘retaught’ their physical experience via virtual experience. This is a type of haptic experience embodied in digital action, or digitised embodiment, which impacts upon the actual body continuously into their everyday lives.

Scholarly investigations on digitised embodiment have examined how the body interacts with, and is (re)configured by, digital technologies, focusing on various increasingly digitised environments—such as “sensor-saturated physical environments” (Lupton, 2017 , 202), where the body is exposed to, grows with, and is constantly under surveillance—that configurate and reconfigure bodily actions (Bauman and Lyon, 2012 ; Kitchin and Dodge, 2011 ; Kitchin, 2014 ). The body is digitised and recorded constantly while surfing online, walking under surveillance, talking on the smartphone, body scanning for health checks, etc., hereby reproduced by/in the digitised environment. In other words, digital data are generated and used to further discipline bodily behaviours. The complex relation between body and digital technology is full of entanglements, as well as inextricabilities in terms of sociomaterialism, which argues social and materiality aspects are entangled in an organisational life (Orlikowski, 2007 ). In Orlikowski and Scott’s words: “sociomateriality is integral, inherent, and constitutive, shaping the contours and possibilities of everyday organizing” (2008, 463). The inextricable, intertwining in-between reflects that the body is a digital data assemblage (Lupton, 2015 ). The entanglements in, and co-configuration of, each other, between body and digital technology, reflect a type of bodily knowing that is inclusive of haptic experience.

Bodily knowing, apart from being related to individual consciousness of the body’s physical conditions, is the understanding of and interaction with its surroundings, which are usually occupied by other bodies and objects. As Lupton notes, “[w]e experience the world as fleshly bodies, via the sensations and emotions configured through and by our bodies as they relate to other bodies and to material objects and spaces” (2017, 201). The body extends beyond its physical entity and is distributed into the inhabited space involving embodied interactions and affective responses, whereby embodiment is a relational assemblage (Lupton, 2017 ). While feelings are produced through interaction between self and world (Labanyi, 2010 , 223), the body in environment touches and is touched.

Acknowledging that the virtual is anthropological (Boellstorff, 2008 , 237), anthropological methods can be applied to investigating the world of the virtual by (re)interpreting socio-cultural relations manifested in virtual space, such as social status, gender issues, disabilities, ethnicities, class, etc. For example, scholars in videogame studies investigate bodily representations in virtual space, with focus on the presence, absence, and types of the portrayal of social groups in terms of identity, gender, and sexuality (Downs and Smith, 2005 ; Heintz-Knowles et al. 2001 ; Janz and Martis, 2007 ; Williams et al. 2009 ), and the phenomenological experiences of engaging with third-person videogames, which the player controls the game through avatars that results in control of three bodies: the avatar’s body, player’s own body, and visual perspective of a “game body” (Crick, 2011 , 262). Footnote 10 Bodily actions may be conducted in actuality, yet their simulated impact virtually can achieve certain new actions created in the situated mixed reality where body capacities and boundaries can be rethought in terms of situatedness. The bodily actions conducted while comprehending the mixed environment via haptic experience produce new ‘digitised’ knowledge and become the bodily digital. The case study on digital fashion design practice is analysed to substantiate the thinking of the bodily digital whereby the body in everyday practice/life is the product of digital actions that, in turn, lead to ‘digitised’ knowledge.

Designing digital cloth requires relatively fewer intensive actions, mostly limited to the operation of computer devices, including typing on the keyboard, dragging and clicking the mouse, etc., compared to traditional methods in the process of garment making, such as sewing, stitching and cutting, which involve the participation of the whole body, where the texture of fabrics is sensed and understood mainly via touch. When touching occurs, somatosensory signals are transduced by nerves, either as the pressure felt by the designer’s fingertips pressing against the textile, or the temperature felt from the warmth of the fabric on the skin. The haptic knowledge about textiles is embedded in designers who were initially trained in traditional methods; subsequently, their bodily experience casts the approach and fosters the understanding of digital garment making. Moreover, digital clothing, which require comparatively fewer complex bodily tasks in the process of making, is done in virtual space that prompts designers to rethink their bodily boundary and capacities in the mixed (in)tangible world. There is a correlation between a simple latitude action taken with minimum muscular tension, and achieving rather complex tasks in digital space. The narrowing ‘gap’ between the body and the digital is manifested in the case of digital fashion design practice that reflects how the haptic experience is digitised, and how the digital experience is bodily digital. Designers engaging with digital data assemblages are in turn managed and manipulated by the assemblages that impact upon their ways of knowing and embodiment in their practice that is situated in mixed reality. “Technologies discipline the body to better assimilate it to their requirements, their ways of seeing, monitoring and treating human flesh” (Lupton, 2017 , 203).

Fashion designers not only use 3D-technology to create digital prototyping and sampling of the garment for final visualisation, but also to think through, with and alongside the digital technologies and new media (Manovich, 2020 ; Hansen, 2006 ; Hayles, 2012 ), as supported by Johnston’s argument (2012) on the concept of autonomy in technology, which is originally from Kittler ( 1990 ). The digital transformation, called digital mediatisation or ‘digital fashion’ (Milne, 2019 ), in the investigation on fashion and its relation to digital media (Rocamora, 2017 , 505), takes place in many facets, such as fashion shows, collections design and retailing, that turn the products, wearers and environments partially or entirely virtual. Although many hurdles and challenges have been identified, such as how fashion design practice can create meaningful content for digital worlds (Tepe and Koohnavard, 2023 ), the shift to computer-aided design (CAD), such as CLO3D and Browzwear, is becoming popular in everyday design practice. The technology enables and enhances design processes operating under the concept of greener and more sustainable design, such as the use of digital 3D software in zero-waste fashion design practice (McQuillan, 2020 ) and 3D virtual prototyping as a new medium and influence on design methods and visual thinking (Siersema, 2015 ).

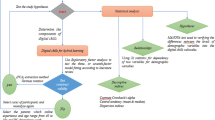

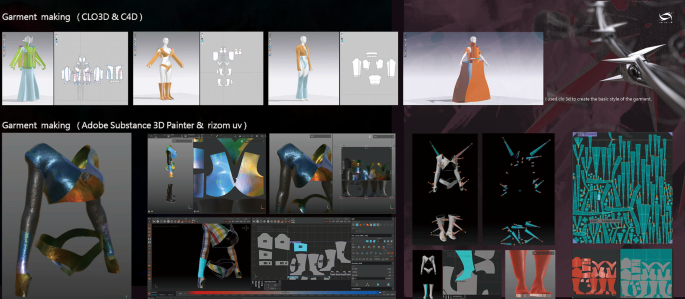

The digital work, entitled The Region ‘X’ , created by fashion designer Tianjiao Wang in 2022, with its theme on the human body intertwining with all things, is inspired by a movie called Annihilation (Garland, 2018 ). Wang is trained in traditional methods of garment making accompanied with essential knowledge and bodily skills, but has lately turned her attention to the digital field, creating collections using software. For example, the pattern cutting and silhouette of The Region ‘X’ are done by CAD and Photoshop respectively, and the virtual fabric reinforcement is manipulated in CLO3D, as shown in Fig. 1 . The sagging effect of cloth as a visual experimentation is done by Cinema 4D, which allows for continuous adjustments of the garment style and shape and detailed design in the virtual environment. RIZOMUV is used to arrange and disassemble the UV and to optimise the position of the panels. Painting the surface materials of the garment is then done by Adobe Substance 3D Painter, as shown in Fig. 2 . Accessories, such as hand decoration, shoes and hats, are created in Cinema 4D.

The visual experimentation, such as the sagging effect of cloth, is simulated in Cinema 4D. The virtual reality allows for continuous adjustments of the garment style and shape. Photo credit: Tianjiao Wang, 2023.

Wang experiments with painting on the surface of garment materials in Adobe Substance 3D Painter. Visually triggered ‘touch’ experience takes place in this practice. Photo credit: Tianjiao Wang, 2023.

Digital technology is used as a means of creating alternative fashion-related experiences for digital and hybrid spaces, introducing practitioners to possibilities beyond the construction of physical products through digital means. The concept has been widely implemented in contemporary fashion education; for example: new technologies are taught at fashion schools (Bain, 2022 ); new teaching models are associated with technology learning (Bertola and Colombi, 2021 ); digital skills are used in the fashion studio (Särmäkari, 2023 ); and body-diverse methods are used in designing dress in the digital age (Tepe, 2022 ). Yet, digital fashion is more than a visual festival; advanced digital technology is not a better tool than the sewing machine, for example. As shown in Wang’s case, the body interacts with and is situated in the mixed reality, where the sensorial body is in full operation and becomes bodily digital. The body is the product of digital actions and is a digital embodied being. Tactile experience, via touch and feel, which is essential for traditional designers in differentiating and selecting textures and materials that express individuality and create meanings, is significantly intertwined with visual experience in the digital space. In this sense, the texture and material of fabrics, such as wool, cotton, linen, synthetic polyester, etc., are identified by visual perception, given the capacity of CAD, such as CLO3D and Browzwear, to vividly delineate various textures on screen. In other words, the simulated materiality shown on screen is detected by visual means and ‘perceived’ by the body in front of the computer with haptic experience via touching the keypad, clicking on the mouse, etc. The digital design practice provokes the memory of bodily touching materials, which is reassured visually on screen, therefore that fabric is ‘touched’, ‘felt’ and selected. This mixed reality practice produces a type of haptic experience, which involves the visual. The intertwining of the body with mixed realities via visual and haptic experience makes the bodily digital or digital embodiment, in which ‘digitised’ knowledge is produced as the body becomes the product of digital actions (Fig. 3 ).

Photo credit: Tianjiao Wang, 2023.

Mobilising the bodily inclusive in research activity

Thinking digital technology (such as Web 3.0), humanities and contemporary theory of bodily embodiment altogether is being bodily inclusive in research activity. There are no identical bodily actions taking place, for example, among different scholars or by the same scholar in different projects, regardless of the methods used. The attention on bodily actions brings forth an alternative thought process to help with re-examining and improving incomplete research, offering a pathway other than a concrete conclusion as a traditional research outcome. Take for example Zhu’s ( 2021 ) analysis based on distance reading of 1500 review comments collected as a small fraction out of the total of 654,914 comments on the Internet platform Douban regarding the famous Chinese movie The Wandering Earth . Footnote 11 Review comments were collected solely from Douban, which means that data from other major Chinese online platforms are not taken into consideration. To go beyond Zhu’s limited conclusion on the movie, which attracted great public attention and opinion in the Douban community, the bodily inclusive approach can offer further possible work to be done in terms of the online users and the scholarly practice.

Online social media environment such as Douban have specific users in terms of gender, age, cultural background, social status, etc. as well as online behaviours that are relatively consistent. The 1500 comments were first screened and selected by Douban as the gatekeeper before being made available to viewers, including Zhu. Without an understanding of the criteria used by Douban in screening and selecting comments, that is to say, in determining what can or cannot be seen by viewers, the analysis of the 1500 comments could be misleading in reflecting the viewers’ genuine attitude towards the movie in the Douban community. Despite the current limitations of the research, thinking the bodily inclusive can alter the focus to, for instance, bodily actions of online users, who are differentiated in gender, age, cultural background and social status, moving in and out of actual and virtual space while operating and being operated by digital technologies, whereby digital bodily actions become an active part in perceiving and reflecting their perception and attitude towards the movie. There is a potential pathway for Zhu to pursue deeper understanding and to obtain further insights about the impact of the movie on the online community by focussing on the users’ bodily interactions in relation to digital technologies, Footnote 12 rather than relying on and being limited by the official screening of the comments against certain criteria and social values. For example, Piper investigates online reading concerning users’ hands (2012), that reading body in a digital environment requires greater haptic intelligence (McLaughlin, 2015 ). The impact of digitisation on tactility and the sensory responses of users (Mangen and Schilhab, 2012 ) reflects upon bodily actions. Online reading is a practice that is “material, embodied, and responsive to [the] environment” (Thomas, 2021 , 2), while the reading body in actions is tactile, situated, and creative.

Bodily actions, such as extending the arm and moving the fingers to grab a cup of tea in actual space, is studied within the scope of anthropology and social science, where bodily gesture and the action sequences reflect social status, gender issues, disabilities, ethnicities, individuality, etc., while meanings and interpretations are (re)produced. While research has extended into the world of the virtual to investigate the avatar as the representation of the body and its relation to other avatars in a virtual ‘socio-cultural’ environment for example (Villani et al. 2016 ; Freeman and Maloney, 2021 ), there is a body present in front of the computer screen whose tactile experience continues, and whose digitised embodiment reflects the intimate interconnection between DH and the body. That is to say, there is scope to observe and study the situated body of Internet users, acted upon by socio-cultural institutions, and how they exercise power and behave online via concrete bodily movement. Observing and measuring bodily gestures and movements in the way the users drink, smoke, talk, etc. while clicking the mouse, touching the screen, and typing the keyboard to make/delete online comments or ‘like’ things, can provide further insights in terms of the interrelationship between online and offline behaviours. Footnote 13 Furthermore, the interrelationship is mutually impactful between digital technologies and the body as culturally embodied and historically inherited being; bodily action in front of the computer screen is a reflection of this interrelationship.

To observe and study the bodily inclusive on both the scholars who are situated in a digital environment while conducting research activities, and certain groups of people acting online as the study objects, is to think the ‘gap’ and the moment of close encounter between the body and digital technologies. In other words, in the encounter of the two, the characteristics of DH 2.0 come into play as being at once qualitative, interpretive, experiential, emotive and generative, as well as being immanent and lived experience. Moreover, it is foreseeable that increased interactivity and user participation enabled by Web 2.0 (Davidson, 2012 ) are further strengthened by Web 3.0, in which bodily experience in actual and virtual space would be no longer separable for example. Thinking body, digital technology, and humanities altogether, along with the arrival of Web 3.0, is a means to image DH 3.0 in terms of the trans-disciplinary, focussing on the concept of the digital lived encounter.

Furthermore, thinking the bodily inclusive in the process of DH activities is to say Zhu’s research is more than offering a conclusion with more or less limitation though, drawn from database analysis that is always partial and shown in visualised patterns that have to be simplified to allow wider access. Yet, a clear pathway of how the multiple decisions made and led to the conclusion is reflected on the bodily actions. For instance, the process of research involved a large number of Zhu’s bodily actions in interacting with the database that are mutually impactful and can be tracked and reviewed anytime afterwards. In other words, the making in DH practice is a creating of indexicality, a sign pointing to some aspect of its context of occurrence, where each interaction of the involved data as the context, which is selected, omitted, (re)edited and (re)ordered, projects the occurrence of bodily action in front of the computer screen. Every bodily gesture and movement taken contributes to the perception formed by the body towards the world, and impacts upon knowledge production. Therefore, Zhu’s research subject matter is ‘1500 review comments’, but it can also be equally thought that the subject is the work of Zhu’s series of bodily movements interacting with the data in real time in mixed space as an extension of Zhu’s cultural body. The making in DH practice is also the creation of human indexicality. Thinking the bodily inclusive is to acknowledge and unveil the process of knowledge production in DH practice where the constant interaction and mutual impact of operating digital technologies throughout the research is full of criticalness and decision making.

Thinking the bodily inclusive is to go beyond the earlier productive work via traditional methods, which has been erased by the process with only a conclusion at the end. There is no such a thing called ‘raw’ data that seems innocent, as data is mined, collected, stored, sorted, (re)visited, extracted, analysed, deleted and restored via and by bodily actions. There is a reshuffle and a re-ordering and therefore re-interpretion of the data every time a bodily action takes place. Hence, the bodily actions in the research process reflect and visualise the pathway of certain bodily experience gradually accumulated that contribute to the production of knowledge, apart from and along with the fixed and must-be-arrived-at ‘conclusion’ of research.

Acknowledging humanities scholars don’t do things as usual and simply extend their traditional activities enabled by the advantages of networked digital technology, DH transcends beyond a discipline and a research field. It can be seen as a response of and a new exploration in the humanities to the digital age. Therefore, the article proposes an alternative approach for understanding and engaging the concept of the sociological body in order to introduce the bodily inclusive in DH practice, which hints at the possibilities of ‘digitised’ knowledge production and haptic knowledge in upcoming DH 3.0. Digital technology changes the pathway of bodily experience created in research and conceptualisation, in which bodily action is characterised and partially formed by digital technology. The value of the humanities embodied in and reflected on bodily actions would inform and simultaneously be informed by the ways technologies are manipulated, in which certain knowledge is produced and perception towards the world is formed. In other words, the interaction between body and digital technology, which is capable of diminishing the boundary between actual and virtual experience for example, contributes to the perception towards the world.

Apart from technology being a tool, a medium, a laboratory, or a vehicle for activism (Svensson, 2009 , 2010 ) in Web 2.0, bodily actions in upcoming DH 3.0 actively co-make the knowledge of and the understanding towards the world, embedded via the interaction with digital technology. Digital technology not just provides new ways for concepts to be communicated, but new ways to co-produce bodily actions. In a parallel discussion, Hogsden and Poulter consider digital experience “an alternative reciprocal model” (2012, 82) while King et al. regard the digital encounter as a “different category from physical encounters” (2016, 86). For Heim, “virtual worlds…do not simply reproduce the existential features of reality but transform them beyond immediate recognition” (1993, 32). In short, the use of digital technology offers a type of new bodily experience. Therefore, to think the significant engagement of digital technologies as the condition of and the impact upon bodily actions and experience in this process of knowledge production is to say that the certain knowledge is produced by, and can only be, the interactions between body and digital technology, which is how we understand new bodily experience in the digital age and the bodily digital, thereby the knowledge produced by the bodily digital is called ‘digitised’ knowledge.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this research as no data were generated or analysed.

DH is sometimes anti-disciplinary as it does not fit within traditional academic disciplines. Interdisciplinary brings scholars together across disciplines to create an integrated science instead of fragmented disciplines.

There are methods such as qualitative content analysis in communication study that coding is formed to reduce masses of information in traditional text, and variable matrix is subjected to statistical analysis. Further readings refer to Kuckartz ( 2014 ) and Schreier ( 2012 ).

Chinese scholars Chen Dakang and Li Xianping also tried to use this method to determine the copyright of A Dream of Red Mansions [紅樓夢] in the 1980s.

They are the center-type lab, techno-science lab, work station-type lab, social challenges-centric lab, and virtual lab (Pawlicka-Deger, 2020 ).

According to Ekman and Friesen, there are five categories of nonverbal behavior in terms of psychology.

Raman and Singh note the five basic physical descriptions of facial expressions, which are neutral, relaxed, tense, uplifted, and droopy.

According to Anderson, there are three main types of gestures, which are adaptors, emblems, and illustrators, and five groups of facial expressions, including happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust.

Kendon examines body gestures in terms of communication; and McNeill proposes a general classification of four types of hand gestures, including beat, deictic, iconic, and metaphoric.

I acknowledge the example that the digital practice of fashion designers might not be considered integral to DH discourses globally in some scholars’ thoughts. Nevertheless, the case supports the argument of how the haptic experience in physical space is re-mediated through digital technology.

According to Crick, the “game body” is “the software-simulated mobile camera that follows (or inhabits) a game character in a virtual world” (2011, 261).

Douban is one of the major Chinese online platforms providing information about novels, movies, TV series, music, stage plays, etc. where users can search, comment, communicate, and interact with each other. There are over 200 million registered users and over 400 million monthly active users as of the end of 2019. https://www.douban.com/partner/intro

Interactions include bodily movement and associate ‘motor action’.

Previous studies on Human-Computer Interaction provides various examples of using gesture-based sensors such as Kinect to capture users’ interaction gestures.

Adams BA (2022) ‘Whole self to the world’: creating affective worlds and black digital intimacy in the fandom of the misadventures of awkward black girl and insecure. Dig Hum Q 16(3). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/16/3/000639/000639.html

Alpert-Abrams H, McCarl C (2021) Digital humanities and Colonial Latin American studies. Spec issue Dig Hum Q 14::4. (eds)

Google Scholar

Alvarado RC (2012) The digital humanities situation. In: Gold MK (ed) Debates in the digital humanities. University of Minneapolis Press, Minneapolis, p 50–55

Chapter Google Scholar

Andersen P (1999) Nonverbal communication: Forms and functions. Mayfield, California

Bain M (2022) The new technologies fashion schools are teaching students. Technology. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/technology/the-new-technologies-fashion-schools-are-teaching-students/

Bauman Z, Lyon D (2012) Liquid surveillance: a conversation. Wiley, Cambridge

Berry DM (2011) The computational turn: thinking about the digital humanities. Cul Mach 12. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/49813/

Bertola P, Colombi C (2021) Reflecting on the future of fashion design education: new education models and emerging topics in fashion design. In: Paulicelli E, Manlow V, Wissinger E (eds) The Routledge companion to fashion studies. Routledge, London, p 84–93

Birdwhistell R (1952) Introduction to Kinesics: An Annotation System for Analysis of Body Motion and Gesture. Department of State, Foreign Service Institute, Washington, DC

Birdwhistell R (1970) Kinesics and context: Essays on body motion communication. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

Boellstorff T (2008) Coming of age in Second Life: an anthropologist explores the virtually human. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Classen C (1997) Foundations for an anthropology of the senses. Int Soc Sci J 153:401–412

Article Google Scholar

Cong-Huyen A (2015) “Toward a transnational Asian/American digital humanities: a #transform invitation. In: Svensson P, Goldberg DT (eds) Between humanities and the digital. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, p 109–120

Cousins N (1989) The computer and the poet. In: Pylyshyn ZW, Bannon L (eds) Perspectives on the computer revolution. Intellect Books, Bristol, p 535–536. 1966

Crick T (2011) The game body: toward a phenomenology of contemporary video gaming. Gam Cul 6(3):259–269

Crossley N (2005) Mapping reflexive body techniques: on body modification and maintenance. Bod Soc 11(1):1–35

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Csordas TJ (1994) Embodiment and experience: the existential ground of culture and self. Cambridge University Press, Oxford

Da NZ (2019) The computational case against computational literary analysis. Cri Inq 45(3):601–639

Davidson C (2012) Humanities 2.0: promise, perils, predictions. In: Gold MK (ed) Debates in the digital humanities. University of Minneapolis Press, Minneapolis, p 476–489

Downs E, Smith S (2005) Keeping abreast of hypersexuality: a videogame character content analysis. International Communication Association, New York, p 26–30

Drucker J (2012) Humanities theory and digital scholarship. In: Gold MK (ed) Debates in the digital humanities. University of Minnesota Press, City, p 85–95

Earhart AE (2012a) Can information be unfettered? Race and the new digital humanities canon. In: Gold MK (ed) Debates in the digital humanities. University of Minneapolis Press, Minneapolis, 309–318

Earhart AE (2012b) The digital edition and the digital humanities. Tex Cul 7(1):18–28

Ekman P, Friesen W (1969) The Repertoire or Nonverbal Behavior: Categories, Origins, Usage and Coding. Semiotica 1:49–98. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1969.1.1.49

Featherstone M, Hepworth M, Turner BS (1991) The body: social process and cultural theory. Sage, London

Book Google Scholar

Feld S (2005) Places sensed, senses placed: towards a sensuous epistemology of environments. In: Howes D (ed) Empire of the senses: the sensual culture reader. Berg, Oxford, p 179–191

Fish S (2012) Mind your p’s and b’s: the digital humanities and interpretation. The New York Times. https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/23/mind-your-ps-and-bs-the-digital-humanities-and-interpretation/

Fitzpatrick K (2010) Reporting from the Digital Humanities 2010 Conference. https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/reporting-from-the-digital-humanities-2010-conference

Foucault M (1991) Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison (trans: Sheridan A). Penguin, London

Freeman G, Maloney D (2021) Body, Avatar, and Me: The Presentation and Perception of Self in Social Virtual Reality. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 4 CSCW3 No 239 https://doi.org/10.1145/3432938

Fuller MA (2020) Digital humanities and the discontents of meaning. J Chi His 4(2):259–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/jch.2020.13

Garland A (2018) Annihilation. DNA Films, UK, (dir)

Geurts KL (2005) Consciousness as “feeling in the body”. In: Howes D (ed) Empire of the senses: the sensual culture reader. Berg, Oxford, p 164–178

Gil A (2015) The user, the learner and the machines we make. Minimal Computing. https://go-dh.github.io/mincomp/thoughts/2015/05/21/user-vs-learner/

Hansen MBN (2006) New philosophy for new media. MIT Press, Cambridge

Harpham G (2006) Science and the theft of humanity. Am Sci 4(Jul–Aug):296–298

Hayles NK (2011) How we think: transforming power and digital technologies. In: Berry DM (ed) Understanding the digital humanities. Palgrave, London, p 42–66

Hayles NK (2012) How we think digital media and contemporary technogenesis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Heim M (1993) The metaphysics of virtual reality. Oxford University Press, London

Heintz-Knowles K, Henderson J, Glaubke C, Miller P, Parker M, Espejo E (2001) Fair play? violence, gender and race in videogames. Children Now, Oakland, CA

Hogsden C, Poulter E (2012) Contact networks for digital reciprocation. Mus Soc 10(2):81–94

Horkheimer M, Adorno TLW (2007) Dialectic of enlightenment. Stanford University Press, Oxford, 1947

Howes D (2003) Sensual relations: engaging the senses in culture and social theory. University of Michigan Press, Michigan

Janz J, Martis R (2007) The lara phenomenon: powerful female characters in videogames. Sex Roles 56(3–4):141–148

Jockers ML, Underwood T (2016) Text-mining the humanities. In: Schreibman S, Siemens R, Unsworth J (eds) A new companion to digital humanities. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex, p 291–306

Johnston J (2012) Fridrich Kittler: Media theory after poststructuralism. In: Johnston J (ed) Literature, Media, Information Systems. Routledge, London, p 1–25

Jones SE (2016) Roberto Busa, S.J., and the emergence of humanities computing: the priest and the punched cards. Routledge, New York

Kendon A (1981) Nonverbal Communication: Interaction and Gesture. Mouton Publisher, The Hague, 10.1515/9783110880021

Ketchum AD (2020) Lost spaces, lost technologies, and lost people: online history projects seek to recover LGBTQ+ spatial histories. Dig Hum Q 14(3). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/14/3/000483/000483.html

King L, Stark JF, Cooke P (2016) Experiencing the digital world: the cultural value of digital engagement with heritage. Her Soc 9(1):76–101

Kirschenbaum M (2012) The humanities, done digitally. In: Gold MK (ed) Debates in the digital humanities. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, p 12–15

Kitchin R (2014) The data revolution: big data, open data, data infrastructures and their consequences. Sage, London

Kitchin R, Dodge M (2011) Code/space: software and everyday life. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Kittler F (1990) Discourse Networks 1800/1900. Stanford University Press, Redwood City, CA

Knorr Cetina K (1999) Epistemic cultures: how the sciences make knowledge. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Kuckartz U (2014) Qualitative Text Analysis: a Guide to Methods Practice. Sage, Los Angeles

Labanyi J (2010) Doing things: emotion, affect, and materiality. J Span Cul Stu 11(3–4):223–233

Lan L, Liu P (2023) Exhibiting fashion on the heritage site: the interrelation between body, heritage space, and fashionable clothing. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:827, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-023-02373-8

Leder D (1990) The absent body. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Lippmann W (1922) Public opinion. Harcourt, Brace, New York

Liu P (2018) Walking in the Forbidden City: embodied encounters in narrative geography. Vis Stu 33(2):144–160

Liu P (2020) Body in the Forbidden City: embodied sensibilities and lived experience in the affective architecture. In: Micieli-Voutsinas J, Person AM (eds) Affective architectures: more-than-representational geographies of heritage. Routledge, New York, p 120–139

Liu P (2022) Weather as medium: exploring bodily experience in the heritage space under light, air and temperature conditions. J Arch 27(7–8)

Liu P, Lan L (2020) Constructing an affective retail space: bodily engagement with a luxury fashion brand through spatial and heritage storytelling. In: Sikarskie AG (ed) Storytelling in luxury fashion marketing: visual culture and digital technology. Routledge, New York, p 157–173

Liu P, Lan L (2021) Museum as multisensorial site: story co-making and the affective interrelationship between museum visitors, heritage space, and digital storytelling. Mus Manag Cur 36(4):403–426

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Liu P, Lan L (2021) Bodily changes: the castration as cultural and social practice in the space of the Forbidden City. SAGE Open 11(3):1–12

Lupton D (2015) Donna Haraway: the digital cyborg assemblage and the new digital health technologies. In: Collyer F (ed) The Palgrave handbook of social theory in health, illness and medicine. Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, p 567–581

Lupton D (2017) Digital bodies. In: Silk M, Andrews D, Thorpe H (eds) Routledge handbook of physical cultural studies. Routledge, London, p 200–208

Malazita JW, Teboul EJ, Rafeh H (2020) Digital humanities as epistemic cultures: how DH labs make knowledge, objects, and subjects. Dig Hum Q 14(3). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/14/3/000465/000465.html

Mandell LC (2016) Gendering digital literary history: what counts for digital humanities. In: Schreibman S, Siemens R, Unsworth J (eds) A new companion to digital humanities. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex, p 511–523

Mangen A, Schilhab T (2012) An embodied view of reading: theoretical considerations, empirical findings and educational implications. In: Matre S, Skaftun A (eds) Skriv! Les! Akademika Forlag, Trondheim, p 285–300

Manovich L (2009) The practice of everyday (media) life: from mass consumption to mass cultural production? Cri Inq 35(2):319–331. https://doi.org/10.1086/596645

Manovich L (2013) Software takes command. Bloomsbury Academic, New York

Manovich L, Douglas, J (2009) Visualizing Temporal Patterns in Visual Media. http://manovich.net/content/04-projects/061-article-2009/58-article-2009.pdf

Manovich L (2020) Cultural analytics. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Marcuse H (2003) One-dimensional man: studies in the ideology of advanced industrial society. Routledge, New York, 1964

Mauss M (1979) Techniques of the body. In: Mauss M (ed) Sociology and psychology: essays (trans: Brewster B). Routledge, Kegan Paul, London, p 97–123

McCarty W (2016) Becoming interdisciplinary. In: Schreibman S, Siemens R, Unsworth J (eds) A new companion to digital humanities. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex, p 67–83

McGann J (2008) The future is digital. J Vic Cul 13(1):80–88

McGann J (2013) Philology in a new key. Cri Inq 39(2):327–346

McGann J (2014) A new republic of letters–memory and scholarship in the age of digital reproduction. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

McLaughlin T (2015) Reading and the Body: The Physical Practice of Reading. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

McNeill D (1992) Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

McQuillan H (2020) Digital 3D design as a tool for augmenting zero-waste fashion design practice. Int J Fash Des, Tech Edu 13(1):89–100

Moretti F (2000) Conjectures on world literature. New Left Rev (Jan–Feb). https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii1/articles/franco-moretti-conjectures-on-world-literature

Moretti F (2005) Graphs, maps, trees: abstract models for literary history. Verso, London, https://docdrop.org/static/drop-pdf/Pages-from-Moretti-2007-Graphs-Maps-bkBff.pdf

Moretti F (2013) Distant Reading. Verso, London

Milne R (2019) The rise of digital clothing––Q&A with digital fashion expert and founder of HOT: SECOND Karinna Nobbs. Accessed 5 September 2023. https://blog.edited.com/blog/resources/the-rise-of-digital-fashion-qa

Negroponte N (1995) Being digital. Knopf Doubleday, New York

Nowviskie B (2015) Resistance in the materials. In: Svensson P, Goldberg DT (eds) Between humanities and the digital. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, p 383–389

Oiva M (2020) The chili and honey of digital humanities research: the facilitation of the interdiscinplinary transfer of knowledge in digital humanities centers. Dig Hum Q 14(3). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/14/3/000464/000464.html

Oiva M, Pawlicka-Deger U (2020) Lab and slack. Situated research practices in digital humanities––introduction to the DHQ special issue. Dig Hum Q 14(3). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/14/3/000485/000485.html

Olofsson J (2015) Did you mean ‘why are women cranky?’. In: Svensson P, Goldberg DT (eds) Between humanities and the digital. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, p 243–251

Orlikowski W (2007) Sociomaterial practices: exploring technology at work. Org Stu 28(9):1435–1448

Orlikowski W, Scott S (2008) 10 sociomateriality: challenging the separation of technology, work and organization. Aca Manag Ann 2(1):433–474

Pannapacker W (2009) The MLA and the digital humanities. The Annual Meeting of Modern Languages Association (MLA) Conference

Parikka J (2012) Archives in media theory: material media archaeology and digital humanities. In: Berry DM (ed) Understanding digital humanities. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, p 85–104

Patel D (2014) Body language: An effective communication tool. IUP J Eng Stu IX(2):90–95

Paterson M (2007) The senses of touch: haptics, affects and technologies. Taylor and Francis, New York

Paterson M (2011) More-than visual approaches to architecture: vision, touch, technique. Soc Cul Geo 12(3):263–281