Essay Papers Writing Online

Effective essay writing rubrics to enhance students’ skills and performance.

Essay writing is a fundamental skill that students must master to succeed academically. To help students improve their writing, educators often use rubrics as a tool for assessment and feedback. An essay writing rubric is a set of criteria that outlines what is expected in a well-crafted essay, providing students with clear guidelines for success.

Effective essay writing rubrics not only evaluate the quality of the content but also assess the organization, coherence, language use, and overall structure of an essay. By using a rubric, students can better understand what aspects of their writing need improvement and how to achieve higher grades.

This article will explore the importance of essay writing rubrics in academic success and provide tips on how students can use them to enhance their writing skills. By understanding and mastering the criteria outlined in a rubric, students can not only improve their writing but also excel in their academic endeavors.

Learn the Key Elements

When it comes to effective essay writing, understanding the key elements is essential for academic success. Here are some important elements to keep in mind:

- Thesis Statement: A clear and concise thesis statement that presents the main idea of your essay.

- Structure: A well-organized structure with introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

- Evidence: Use relevant evidence and examples to support your arguments.

- Analysis: Analyze the evidence provided and draw conclusions based on your analysis.

- Clarity and Coherence: Ensure that your essay is clear, coherent, and easy to follow.

By mastering these key elements, you can improve your essay writing skills and achieve academic success.

Elements of Effective Essay Writing

When it comes to writing a successful essay, there are several key elements that you should keep in mind to ensure your work is of high quality. Here are some essential aspects to consider:

Understand the Importance

Understanding the importance of essay writing rubrics is crucial for academic success. Rubrics provide clear criteria for evaluating and assessing essays, which helps both students and instructors. They help students understand what is expected of them, leading to more focused and organized writing. Rubrics also provide consistency in grading, ensuring that all students are evaluated fairly and objectively. By using rubrics, students can see where they excel and where they need to improve, making the feedback process more constructive and impactful.

of Clear and Concise Rubrics

One key aspect of effective essay writing rubrics is the clarity and conciseness of the criteria they outline. Clear and concise rubrics provide students with a roadmap for success and make grading more efficient for instructors. When creating rubrics, it is essential to clearly define the expectations for each aspect of the essay, including content, organization, style, and grammar.

By using language that is straightforward and easy to understand, students can easily grasp what is expected of them and how they will be evaluated. Additionally, concise rubrics avoid confusion and ambiguity, which can lead to frustration and misunderstanding among students.

Furthermore, clear and concise rubrics help instructors provide more targeted feedback to students, allowing them to focus on specific areas for improvement. This ultimately leads to better learning outcomes and helps students develop their writing skills more effectively.

Implement Structured Guidelines

Structured guidelines are essential for effective essay writing. These guidelines provide a framework for organizing your thoughts, ideas, and arguments in a logical and coherent manner. By implementing structured guidelines, you can ensure that your essay is well-organized, cohesive, and easy to follow.

One important aspect of structured guidelines is creating an outline before you start writing. An outline helps you plan the structure of your essay, including the introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. It also helps you organize your ideas and ensure that your arguments flow logically from one point to the next.

Another important aspect of structured guidelines is using transitions to connect your ideas and arguments. Transitions help readers follow the flow of your essay and understand how one point relates to the next. They also help maintain the coherence and clarity of your writing.

Finally, structured guidelines include formatting requirements such as word count, font size, spacing, and citation style. Adhering to these formatting requirements ensures that your essay meets academic standards and is visually appealing to readers.

for Academic Excellence

When aiming for academic excellence in essay writing, it is essential to adhere to rigorous standards and criteria set by the educational institution. The use of effective essay writing rubrics can greatly enhance the quality of academic work by providing clear guidelines and criteria for assessment.

Academic excellence in essay writing involves demonstrating a deep understanding of the subject matter, presenting a well-structured argument, and showcasing critical thinking skills. Rubrics can help students focus on key elements such as thesis development, evidence analysis, organization, and clarity of expression.

By following a well-designed rubric, students can ensure that their essays meet the desired academic standards and expectations. Feedback provided based on the rubric can also help students identify areas for improvement and guide them towards achieving academic success.

Master the Art

Mastering the art of essay writing requires dedication, practice, and attention to detail. To become a proficient essay writer, one must develop strong writing skills, a clear and logical structure, as well as an effective argumentative style. Start by understanding the purpose of your essay and conducting thorough research to gather relevant information and evidence to support your claims.

Furthermore, pay close attention to grammar, punctuation, and spelling to ensure your work is polished and professional. Use essay writing rubrics as a guide to help you stay on track and meet the necessary criteria for academic success. Practice makes perfect, so don’t be afraid to revise and edit your work to improve your writing skills even further.

By mastering the art of essay writing through consistent practice and attention to detail, you can set yourself up for academic success and develop a valuable skill that will benefit you in various aspects of your life.

of Constructing Detailed Evaluations

Constructing detailed evaluations in essay writing rubrics is essential for providing specific feedback to students. When designing a rubric, it is important to consider the criteria that will be assessed and clearly define each level of performance. This involves breaking down the evaluation criteria into smaller, measurable components, which allows for more precise and accurate assessments.

Each criterion in the rubric should have a clear description of what is expected at each level of performance, from basic to proficient to advanced. This helps students understand the expectations and enables them to self-assess their work against the rubric. Additionally, including specific examples or descriptors for each level can further clarify the expectations and provide guidance to students.

Constructing detailed evaluations also involves ensuring that the rubric aligns with the learning objectives of the assignment. By mapping the evaluation criteria to the desired learning outcomes, instructors can ensure that the rubric accurately reflects what students are expected to demonstrate in their essays. This alignment helps students see the relevance of the assessment criteria and encourages them to strive for mastery of the material.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, tips and techniques for crafting compelling narrative essays.

Criteria of a Perfect Essay

Writing is easier said than done and writing a perfect essay requires keenness to details as well as the application of certain criteria. Writing is a process, and it takes time, patience, and endless practice to grow and develop this skill to perfection. Unfortunately, for a newbie and a majority of writing amateurs, writing is easy and anyone with a good command of English can write. They could not be more wrong. Having a great command of the queen’s language will not guarantee or qualify you as a great writer much less a writer. Writing requires more than just language and a repository of great vocabulary, and you have to grow and develop your skills before you can call yourself a writer. You should not expect to simply become and evolve into a great writer overnight. Perfect essay writing requires a resolve and a commitment to certain criteria which makes up the essence of this article. If you are in immediate need of assistance and deadlines to meet, you can also explore option to buy essays online which can be your lifeline in such difficult situations.

How to Write a Perfect Essay

- Ensure you have a thesis and thesis statement . When writing a perfect essay, you must have a thesis. This gives your essay purpose and with it you can develop and build your stance. A thesis helps you to identify the topic of your essay and it is followed by other sentences. The thesis statement makes it simple for your readers to understand your perspective or viewpoint.

- Have a well-structured essay . Perfect essay writing necessitates organization. Each body paragraph of your essay should begin with a topic sentence which conveys the main point of a single body paragraph. The topic sentence ought to have an argument which supports or builds on the thesis statement so as to motivate your readers’ interest in your article. You may require some help and ideas to better structure your work and consider taking help of professional services.

- Provide evidence for your arguments . For you to learn how to write a perfect college essay, you should have resolute support for your claims. Your argument is well presented when you state it and explain the specifics which led you to this conclusion. This effectively sets up your organization.

- Subject perception . Your essay can be well-organized but without acuity it does not bare much evidence based on your arguments. In order to learn how to write a perfect essay, the perspicacity of your subject ought to relate directly to the organization and the evidence you provide for your arguments. With this, you dig deeply with your claims and offer a perceptive subject.

- Resolve yourself to being lucid . Perfect essay writing requires clear and concrete words and sentences. Its vitality is that the meaning of your article will reach your readers thus your essay will be highly graded. Ensure that you do not introduce your paragraphs with the commonly used examples in class.

- Purpose to use a formal voice throughout your essay . For you to comprehend how to write a perfect essay, you should use the formal speech. This is crucial since it makes you sound more substantial and in command. Avoid using the informal language and retrenchments such as can’t, won’t, isn’t etc.

- Be resourceful in how you come up with your ideas . Perfect essay writing necessitates a distinctive presentation of ideas. This drives your readers to want to know more of what your essay entails. Present your opinions in an original format so as to make your article to appear more alluring.

- Purpose to maintain relevance throughout your essay . When writing a perfect essay, ensure that you do not veer off topic. Your readers can easily lose interest and give up on continuing to read your article. Ensure that the subsequent paragraphs link or mimic the main argument or the thesis statement.

- Using correct spelling and punctuation enables you to improve on how to write a perfect college essay. To ensure this, make an effort of always proofreading through your paper and omit the errors you come across.

Writing needs to have a goal and a purpose because, without one, an article may not appeal to the readers. Readers need to look forward to the next paragraph. From the criteria above, some simple and seemingly irrelevant factors like punctuation and the choice of voice must also be taken seriously.

In conclusion, writing perfect essays takes time and you need to have a plan in place. The ideas to be included in an article should be well-researched and have enough substance to develop or build the thesis statement. The points provided above are not necessarily all you need to write a perfect essay, but they can help you comprehend what a perfect essay entails and warrants. Simply adhere to the above criteria and maintain a keen eye to details and you might surprise yourself.

About The Author

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.3 Becoming a Successful College Writer

Learning objectives.

- Identify strategies for successful writing.

- Demonstrate comprehensive writing skills.

- Identify writing strategies for use in future classes.

In the preceding sections, you learned what you can expect from college and identified strategies you can use to manage your work. These strategies will help you succeed in any college course. This section covers more about how to handle the demands college places upon you as a writer. The general techniques you will learn will help ensure your success on any writing task, whether you complete a bluebook exam in an hour or an in-depth research project over several weeks.

Putting It All Together: Strategies for Success

Writing well is difficult. Even people who write for a living sometimes struggle to get their thoughts on the page. Even people who generally enjoy writing have days when they would rather do anything else. For people who do not like writing or do not think of themselves as good writers, writing assignments can be stressful or even intimidating. And of course, you cannot get through college without having to write—sometimes a lot, and often at a higher level than you are used to.

No magic formula will make writing quick and easy. However, you can use strategies and resources to manage writing assignments more easily. This section presents a broad overview of these strategies and resources. The remaining chapters of this book provide more detailed, comprehensive instruction to help you succeed at a variety of assignments. College will challenge you as a writer, but it is also a unique opportunity to grow.

Using the Writing Process

To complete a writing project successfully, good writers use some variation of the following process.

The Writing Process

- Prewriting. In this step, the writer generates ideas to write about and begins developing these ideas.

- Outlining a structure of ideas. In this step, the writer determines the overall organizational structure of the writing and creates an outline to organize ideas. Usually this step involves some additional fleshing out of the ideas generated in the first step.

- Writing a rough draft. In this step, the writer uses the work completed in prewriting to develop a first draft. The draft covers the ideas the writer brainstormed and follows the organizational plan that was laid out in the first step.

- Revising. In this step, the writer revisits the draft to review and, if necessary, reshape its content. This stage involves moderate and sometimes major changes: adding or deleting a paragraph, phrasing the main point differently, expanding on an important idea, reorganizing content, and so forth.

- Editing. In this step, the writer reviews the draft to make additional changes. Editing involves making changes to improve style and adherence to standard writing conventions—for instance, replacing a vague word with a more precise one or fixing errors in grammar and spelling. Once this stage is complete, the work is a finished piece and ready to share with others.

Chances are, you have already used this process as a writer. You may also have used it for other types of creative projects, such as developing a sketch into a finished painting or composing a song. The steps listed above apply broadly to any project that involves creative thinking. You come up with ideas (often vague at first), you work to give them some structure, you make a first attempt, you figure out what needs improving, and then you refine it until you are satisfied.

Most people have used this creative process in one way or another, but many people have misconceptions about how to use it to write. Here are a few of the most common misconceptions students have about the writing process:

- “I do not have to waste time on prewriting if I understand the assignment.” Even if the task is straightforward and you feel ready to start writing, take some time to develop ideas before you plunge into your draft. Freewriting —writing about the topic without stopping for a set period of time—is one prewriting technique you might try in that situation.

- “It is important to complete a formal, numbered outline for every writing assignment.” For some assignments, such as lengthy research papers, proceeding without a formal outline can be very difficult. However, for other assignments, a structured set of notes or a detailed graphic organizer may suffice. The important thing is that you have a solid plan for organizing ideas and details.

- “My draft will be better if I write it when I am feeling inspired.” By all means, take advantage of those moments of inspiration. However, understand that sometimes you will have to write when you are not in the mood. Sit down and start your draft even if you do not feel like it. If necessary, force yourself to write for just one hour. By the end of the hour, you may be far more engaged and motivated to continue. If not, at least you will have accomplished part of the task.

- “My instructor will tell me everything I need to revise.” If your instructor chooses to review drafts, the feedback can help you improve. However, it is still your job, not your instructor’s, to transform the draft to a final, polished piece. That task will be much easier if you give your best effort to the draft before submitting it. During revision, do not just go through and implement your instructor’s corrections. Take time to determine what you can change to make the work the best it can be.

- “I am a good writer, so I do not need to revise or edit.” Even talented writers still need to revise and edit their work. At the very least, doing so will help you catch an embarrassing typo or two. Revising and editing are the steps that make good writers into great writers.

For a more thorough explanation of the steps of the writing process as well as for specific techniques you can use for each step, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

The writing process also applies to timed writing tasks, such as essay exams. Before you begin writing, read the question thoroughly and think about the main points to include in your response. Use scrap paper to sketch out a very brief outline. Keep an eye on the clock as you write your response so you will have time to review it and make any needed changes before turning in your exam.

Managing Your Time

In Section 1.2 “Developing Study Skills” , you learned general time-management skills. By combining those skills with what you have learned about the writing process, you can make any writing assignment easier to manage.

When your instructor gives you a writing assignment, write the due date on your calendar. Then work backward from the due date to set aside blocks of time when you will work on the assignment. Always plan at least two sessions of writing time per assignment, so that you are not trying to move from step 1 to step 5 in one evening. Trying to work that fast is stressful, and it does not yield great results. You will plan better, think better, and write better if you space out the steps.

Ideally, you should set aside at least three separate blocks of time to work on a writing assignment: one for prewriting and outlining, one for drafting, and one for revising and editing. Sometimes those steps may be compressed into just a few days. If you have a couple of weeks to work on a paper, space out the five steps over multiple sessions. Long-term projects, such as research papers, require more time for each step.

In certain situations you may not be able to allow time between the different steps of the writing process. For instance, you may be asked to write in class or complete a brief response paper overnight. If the time available is very limited, apply a modified version of the writing process (as you would do for an essay exam). It is still important to give the assignment thought and effort. However, these types of assignments are less formal, and instructors may not expect them to be as polished as formal papers. When in doubt, ask the instructor about expectations, resources that will be available during the writing exam, and if they have any tips to prepare you to effectively demonstrate your writing skills.

Each Monday in Crystal’s Foundations of Education class, the instructor distributed copies of a current news article on education and assigned students to write a one-and-one-half- to two-page response that was due the following Monday. Together, these weekly assignments counted for 20 percent of the course grade. Although each response took just a few hours to complete, Crystal found that she learned more from the reading and got better grades on her writing if she spread the work out in the following way:

For more detailed guidelines on how to plan for a long-term writing project, see Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” .

Setting Goals

One key to succeeding as a student and as a writer is setting both short- and long-term goals for yourself. You have already glimpsed the kind of short-term goals a student might set. Crystal wanted to do well in her Foundations of Education course, and she realized that she could control how she handled her weekly writing assignments. At 20 percent of her course grade, she reasoned, those assignments might mean the difference between a C and a B or between a B and an A.

By planning carefully and following through on her daily and weekly goals, Crystal was able to fulfill one of her goals for the semester. Although her exam scores were not as high as she had hoped, her consistently strong performance on writing assignments tipped her grade from a B+ to an A−. She was pleased to have earned a high grade in one of the required courses for her major. She was also glad to have gotten the most out of an introductory course that would help her become an effective teacher.

How does Crystal’s experience relate to your own college experience?

To do well in college, it is important to stay focused on how your day-to-day actions determine your long-term success. You may not have defined your career goals or chosen a major yet. Even so, you surely have some overarching goals for what you want out of college: to expand your career options, to increase your earning power, or just to learn something new. In time, you will define your long-term goals more explicitly. Doing solid, steady work, day by day and week by week, will help you meet those goals.

In this exercise, make connections between short- and long-term goals.

- For this step, identify one long-term goal you would like to have achieved by the time you complete your degree. For instance, you might want a particular job in your field or hope to graduate with honors.

- Next, identify one semester goal that will help you fulfill the goal you set in step one. For instance, you may want to do well in a particular course or establish a connection with a professional in your field.

- Review the goal you determined in step two. Brainstorm a list of stepping stones that will help you meet that goal, such as “doing well on my midterm and final exams” or “talking to Professor Gibson about doing an internship.” Write down everything you can think of that would help you meet that semester goal.

- Review your list. Choose two to three items, and for each item identify at least one concrete action you can take to accomplish it. These actions may be recurring (meeting with a study group each week) or one time only (calling the professor in charge of internships).

- Identify one action from step four that you can do today. Then do it.

Using College Resources

One reason students sometimes find college overwhelming is that they do not know about, or are reluctant to use, the resources available to them. Some aspects of college will be challenging. However, if you try to handle every challenge alone, you may become frustrated and overwhelmed.

Universities have resources in place to help students cope with challenges. Your student fees help pay for resources such as a health center or tutoring, so use these resources if you need them. The following are some of the resources you might use if you find you need help:

- Your instructor. If you are making an honest effort but still struggling with a particular course, set up a time to meet with your instructor and discuss what you can do to improve. He or she may be able to shed light on a confusing concept or give you strategies to catch up.

- Your academic counselor. Many universities assign students an academic counselor who can help you choose courses and ensure that you fulfill degree and major requirements.

- The academic resource center. These centers offer a variety of services, which may range from general coaching in study skills to tutoring for specific courses. Find out what is offered at your school and use the services that you need.

- The writing center. These centers employ tutors to help you manage college-level writing assignments. They will not write or edit your paper for you, but they can help you through the stages of the writing process. (In some schools, the writing center is part of the academic resource center.)

- The career resource center. Visit the career resource center for guidance in choosing a career path, developing a résumé, and finding and applying for jobs.

- Counseling services. Many universities offer psychological counseling for free or for a low fee. Use these services if you need help coping with a difficult personal situation or managing depression, anxiety, or other problems.

Students sometimes neglect to use available resources due to limited time, unwillingness to admit there is a problem, or embarrassment about needing to ask for help. Unfortunately, ignoring a problem usually makes it harder to cope with later on. Waiting until the end of the semester may also mean fewer resources are available, since many other students are also seeking last-minute help.

Identify at least one college resource that you think could be helpful to you and you would like to investigate further. Schedule a time to visit this resource within the next week or two so you can use it throughout the semester.

Overview: College Writing Skills

You now have a solid foundation of skills and strategies you can use to succeed in college. The remainder of this book will provide you with guidance on specific aspects of writing, ranging from grammar and style conventions to how to write a research paper.

For any college writing assignment, use these strategies:

- Plan ahead. Divide the work into smaller, manageable tasks, and set aside time to accomplish each task in turn.

- Make sure you understand the assignment requirements, and if necessary, clarify them with your instructor. Think carefully about the purpose of the writing, the intended audience, the topics you will need to address, and any specific requirements of the writing form.

- Complete each step of the writing process. With practice, using this process will come automatically to you.

- Use the resources available to you. Remember that most colleges have specific services to help students with their writing.

For help with specific writing assignments and guidance on different aspects of writing, you may refer to the other chapters in this book. The table of contents lists topics in detail. As a general overview, the following paragraphs discuss what you will learn in the upcoming chapters.

Chapter 2 “Writing Basics: What Makes a Good Sentence?” through Chapter 7 “Refining Your Writing: How Do I Improve My Writing Technique?” will ground you in writing basics: the “nuts and bolts” of grammar, sentence structure, and paragraph development that you need to master to produce competent college-level writing. Chapter 2 “Writing Basics: What Makes a Good Sentence?” reviews the parts of speech and the components of a sentence. Chapter 3 “Punctuation” explains how to use punctuation correctly. Chapter 4 “Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?” reviews concepts that will help you use words correctly, including everything from commonly confused words to using context clues.

Chapter 5 “Help for English Language Learners” provides guidance for students who have learned English as a second language. Then, Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” guides you through the process of developing a paragraph while Chapter 7 “Refining Your Writing: How Do I Improve My Writing Technique?” has tips to help you refine and improve your sentences.

Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” through Chapter 10 “Rhetorical Modes” are geared to help you apply those basics to college-level writing assignments. Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” shows the writing process in action with explanations and examples of techniques you can use during each step of the process. Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” provides further discussion of the components of college essays—how to create and support a thesis and how to organize an essay effectively. Chapter 10 “Rhetorical Modes” discusses specific modes of writing you will encounter as a college student and explains how to approach these different assignments.

Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” through Chapter 14 “Creating Presentations: Sharing Your Ideas” focus on how to write a research paper. Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” guides students through the process of conducting research, while Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” explains how to transform that research into a finished paper. Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” explains how to format your paper and use a standard system for documenting sources. Finally, Chapter 14 “Creating Presentations: Sharing Your Ideas” discusses how to transform your paper into an effective presentation.

Many of the chapters in this book include sample student writing—not just the finished essays but also the preliminary steps that went into developing those essays. Chapter 15 “Readings: Examples of Essays” of this book provides additional examples of different essay types.

Key Takeaways

- Following the steps of the writing process helps students complete any writing assignment more successfully.

- To manage writing assignments, it is best to work backward from the due date, allotting appropriate time to complete each step of the writing process.

- Setting concrete long- and short-term goals helps students stay focused and motivated.

- A variety of university resources are available to help students with writing and with other aspects of college life.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt

- Asking Analytical Questions

- Introductions

- What Do Introductions Across the Disciplines Have in Common?

- Anatomy of a Body Paragraph

- Transitions

- Tips for Organizing Your Essay

- Counterargument

- Conclusions

- Strategies for Essay Writing: Downloadable PDFs

- Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines

New Product! Create Academic and Professional Success with “Academic Vocabulary”!

Descriptive Writing: Tips, Checklist, and Cheat Sheet

What is descriptive writing? The real question is this: How do student writers use descriptive writing effectively in real writing? When teachers can answer this question, they know how to use their time wisely to teach descriptive writing.

I mention this because the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) uses three text types: 1) Argument/Opinion, 2) Informational/Explanatory, and 3) Narrative. And another thing to consider is this: When is the last time you wrote or read an entire descriptive essay?

While the CCSS does not include description as a main text type, it does mention description throughout the standards using these terms:

! description, descriptive details, descriptions of actions, narrative descriptions, and write precise enough descriptions of the step-by-step procedures.

In short, the CCSS emphasizes two types of descriptive writing:

1. Descriptive writing as a tool in narrative, expository, and argument writing.

2. Expository Descriptive Writing: This kind of description is really expository writing. Sometimes it’s called General Description or Scientific Description.

The following list focuses on the first type of descriptive writing.

========================================================

Descriptive Writing Tips, Checklist, and Cheat Sheet

1. The writer creates vivid pictures of people, places, things, and events in the mind of the reader using description and sensory details.

2. The writer vividly describes experiences and events bringing them to life.

3. The writer effectively describes processes in detail.

4. The writer’s description follows a logical pattern of organization: e.g., general outline or impression to specific details.

5. The writer creates powerful descriptions using sensory details and imagery. The writer’s language appeals to the five senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell.

6. The writer’s description contains an effective use of figurative language: simile, metaphor, alliteration, personification, etc.

7. The writer skillfully uses description with purpose. The writer describes things that help the reader visualize and understand. The writer describes things that the reader needs to visualize in order to understand.

8. The writer skillfully chooses things that need description:

a. The writer chooses nouns (people, places, things, ideas) that need description. b. The writer chooses events (things that happen) that need description. c. The writer chooses processes (actions and steps that outline how things happen) that need description.

9. The writer describes things that are noticeable, memorable, important, or interesting. The writer avoids describing things that are trivial or unimportant.

10. The writer avoids purple-prose descriptive writing. The writer avoids descriptive writing that distracts from and breaks the flow of the composition’s main purpose and main message. The descriptive writing is not too elaborate, too extravagant, or too flowery. Furthermore, the writer does not provide too much description.

11. Without the writer’s descriptions, the piece of writing would be bland and lacking. The word pictures that the writer paints are necessary and fascinating.

12. The writer skillfully and appropriately navigates between using descriptive details, descriptive passages, and descriptive paragraphs. If the piece of writing is a descriptive whole composition (i.e., a descriptive essay), the writer’s purpose is clear.

13. The writer skillfully uses adjectives, adverbs, and figurative language (similes, metaphors, etc.) to bring the description to life. The writer does not underuse them or overuse them.

14. The writer finds interesting and novel ways to include description:

a. The writer combines description with action. b. The writer uses dialogue as a tool for description. c. The writer uses quotes to describe.

15. The writer uses description as an effective tool that is appropriate for the genre:

a. Main Genre: 1) argument, 2) expository, 3) narrative, 4) descriptive. b. Narrative-Story Genre: mystery, personal narrative, action-adventure story, tale (folktale, fairy tale, tall tale, etc.), historical fiction, etc. c. Format Genre: essay, story, report, article, letter, advertisement, daily school work, etc.

16. The writer uses description to “Show, Don’t Tell.” As Anton Chekhov (1860–1904) famously said, “Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.”

Over 15 Years of Creating Writing Success for Beginning and Struggling Writers of All Ages!

The fastest, most effective way to teach students clear and organized multi-paragraph writing… guaranteed, create academic and professional success today by improving your critical thinking, logical arguments, and effective communication.

8 Note-taking Skills

The capacity to take and organise notes during lessons, for research and assessments, and for exam preparation is a key academic writing skill.

This chapter will cover why, when, where, what, and how to take notes.

No student has ever reached the end of a term or semester and said “gee, I’m really glad I didn’t bother taking any notes”. Note-taking is a key strategy for organising information, ideas, and what you have learned in a chronological and systematic way that can be reviewed later. Humans are not physically or neurologically wired to remember vast amounts of information long-term (unless of course you are one of the extremely rare individuals with an eidetic memory). Also, the more senses you actively use while learning, the more likely you are to remember the information, therefore, writing (or typing) engages another part of your mind.

The short answer is ALWAYS . Every lesson, lecture, library session; every time you engage in a learning activity. The fact is, you won’t know exactly what you’ll need until further down the track and it’s too late when you’ve arrived at the end of the study period and you realise that you haven’t captured enough information to refresh your memory before the big exam or assessment is due. Playing catch-up can be very stressful.

Part of good note-taking is making your notes accessible. Design specific files on your computer or device desktop or have designated partitions in a notebook. Divide your notes into weekly lectures, tutorials, assessment research, further reading. For example, if you have an assessment that involves the weekly readings or materials from weeks 1-5 of the term, then you should know exactly where to locate those materials on your device or in your notebook. It sounds like common sense, but you might be surprised how many students quickly develop poor organisation of their notes.

Important points or key ideas will generally be repeated by your teacher. They will show up on power points or in readings. Use your teachers’ speech and body language cues to identify when a point is being stressed. It is physically impossible to type or write every word that a teacher says because on average they speak about 125 words a minute. That is why it is important that you identify the key points and record them.

There is no one correct method to record notes. There is only the right method for you. Choose something that works for you and develop consistency. However, here are three popular methods:

Cornell Method

In the Cornell Method the page is quickly divided into a 30:70% split. This can be done prior to class or as the class gets underway.

At the top (Title section) record the date, course/subject, and teacher/lecturer.

To the right, record the key information from the lesson or lecture. Remember to watch and listen for cues from the teacher and/or power point.

The left-hand side and summary section are used after class to help commit the information to memory and to review the lesson prior to next class.

Writing questions in the left-hand column helps to clarify meanings, reveal relationships, establish continuity, and strengthen memory. Also, the writing of questions sets up a perfect stage for exam-studying later [1] .

Summarising the class notes into your own words will create a quick reference guide for exams and help you retain valuable knowledge.

As you can see, the right-hand column has the key content as presented by the teacher/lecturer (made in dot-point form). The left-hand column has your thoughts and reactions to these ideas. Once you have had a chance to review the content and how it fits together, the summary at the bottom shows that you have mentally digested the key content and can put it accurately into your own words – a very powerful learning tool.

Also known as concept mapping, this technique creates a visual representation of information and ideas in an organised way. It is a great way of making connections between concepts and demonstrating intertextuality and contextual relationships. It can be very helpful when trying to analyse or break down larger concepts into key features and supporting elements. Watch this quick video to learn more:

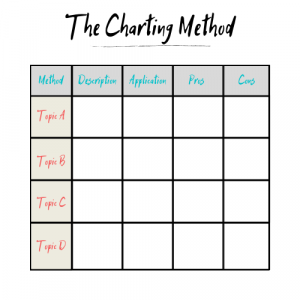

The charting method provides a systematic overview of your notes. The page is split into rows and columns (a table), and labelled. While this method requires some additional preparation time before your lesson, consider making up a simple word document that can be edited and adapted for your purposes. You might find it saves time during class as you can quickly categorise information as you hear or see it. It also transforms into a quick reference guide when it is time to study for your exams.

The charting method is also very useful for synthesizing large amounts of information that is compared across different sources (e.g., topics, theories, readings, approaches, experts). Your job at the start is to determine the best categories to compare and contrast the sources (see blue-green words in diagram).

- Cornell University: Learning Strategies Center. (2019). The Cornell note-taking system. http://lsc.cornell.edu/notes.html ↵

photographic

signal hint

the interrelationship between texts; the way different texts are similar or related, or different to each other

Academic Writing Skills Copyright © 2021 by Patricia Williamson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Primary Hub

- Art & Design

- Design & Technology

- Health & Wellbeing

- Secondary Hub

- Citizenship

- Primary CPD

- Secondary CPD

- Book Awards

- All Products

- Primary Products

- Secondary Products

- School Trips

- Trip Directory

- Trips by Subject

- Trips by Type

- Trips by Region

- Submit a Trip Venue

Trending stories

Top results

- Success Criteria Strategies For Developing Writing Skills In The Classroom

Success criteria – strategies for developing writing skills in the classroom

Criteria for descriptive writing can be restrictive for pupils – but they can be easily expanded, says James Durran…

When approaching a piece of writing, pupils are often given ‘success criteria’ in the form of a list of features which the writing ‘requires’ in order to be successful.

However, colleagues and I have been working with primary schools to develop an alternative to listed success criteria for writing, which we call ‘boxed’ or ‘expanded success criteria’.

It is very easy to adopt, and teachers have been finding that it can transform how writing is discussed and approached in the classroom, with an immediate impact on the quality of what pupils are producing.

Current criteria are tied explicitly to particular curriculum and teaching ‘objectives’, and often include technicalities such as full stops and commas; may include features such as metaphors, adjectives for description, varied sentence openers and so on; and they tend to include grammatical or cohesive devices , such as time adverbials, subordinate clauses or relative pronouns.

These ingredients can be useful, such as reminding pupils of things they might do to make the writing effective, reinforcing learning, providing a ready checklist for self and peer assessment, and so on. But teachers are increasingly aware of their potential drawbacks:

- They can promote a ‘writing-by-numbers’ approach, in which writing becomes a performance of features rather than a coherent whole.

- They can encourage teaching and task-setting by narrow text type, limiting the scope of what pupils might achieve.

- They are not really success criteria. The success of a piece of actual writing can only be measured by how well it communicates or achieves its purpose for its intended reader, not by whether it contains specified ingredients.

- Feedback – at the end or while drafting and editing – can therefore tend to focus just on whether specific elements are included, rather than on how effective the writing is as a complete piece.

Together, these interrelated factors can work against pupils’ development as real writers, writing for specific, authentic purpose and audiences .

Read the room

If pupils are writing a recipe, it is simple and easy to give them a list of components including, for example, ingredients and equipment; numbered steps; time and sequence adverbials; imperative or command verbs.

And these components are a useful starting point. But if you then ask children to compare the following two fragments, which each give the same instruction:

Add Worcester sauce for extra flavour. Slosh in some Worcester sauce to make it even yummier.

Suddenly there is much more to consider. Now, questions such as ‘Who is the recipe for?’ , ‘What do they want and need?’ , ‘How can we engage them?’ and ‘What sort of verbs, nouns and adjectives might we therefore use?’ come up.

Although this might sound like more work, it is much more interesting for pupils, and is certainly more fun to teach!

It is important to teach about genre and the features of different kinds of writing. But as teachers we know that when pupils move on from thinking just in terms of text type, their writing opens up, with much more potential for richness, variety and authenticity.

For example, an account of a trip – perhaps in the form of an article – is not just a ‘recount’. It can be engagingly descriptive, will have elements of entertaining narrative, is likely to involve explanation, and even elements of persuasion and argument.

Similarly, a brochure about a town should be much more than a ‘non-chronological report’. Depending on the intended audience, it will modulate between and blend elements of description, narrative, explanation, instruction and persuasion.

When considering how to help a pupil develop a story opening, it is easy to start listing technical or stylistic devices. For example:

Billy went into the house. He looked into the kitchen. He saw a big dog. The dog ran to him.

But the first question to ask this child is not ‘Could you use some…?’ or ‘Can you add in…?’ It is, simply, ‘What sort of story is this, and how do you want the reader to feel?’ . Then things move forward.

Boxed criteria in practice

Traditional ‘success criteria’ are really the wrong way round. They define ‘success’ in terms of the presence of ingredients, not in terms of the actual point of the writing.

Boxed criteria keep the ingredients, but link them explicitly to purpose and to the reader. It’s really that simple.

In the middle, pupils put what type of writing they’re doing and its intended audience; outwards from this are the intended ‘effects’ on that audience, or what the writing is meant to provide for its readers; outwards again are the ingredients – the features which might help to achieve these things.

Note that in this example the ingredients are themselves described in terms of their impact: ‘scary nouns’, ‘frightening adjectives’ and ‘spooky similes’. Grammatical forms should be used for a reason, not for their own sake.

You might create these boxes yourself and give them to the children. It is more likely, however, that the class will construct them together through discussion, and reading and picking apart examples.

Ultimately, there is nothing radical or intrinsically innovative about this method. It is just a visual device for focusing the thinking of teachers and pupils on what writing is actually about: communication and effect, not just the performance of skills.

Pupils might have their own grid in their books, which can be easily replicated through a simple template. (You can create this in a Word document and keep it handy for the children to stick into their books).

Or, you might decide to have a big class one on the wall. This can be drawn onto the whiteboard, or constructed as part of a classroom display.

A fun way to mix up the boxes is to print out examples of sentences in texts you like and stick them up on the board with an image.

Either way, it can be a dynamic, evolving thing, added to and adjusted as ideas are developed and shared through the planning, drafting and editing stages of writing.

This is a tool which can live with the piece of writing through its stages: from reading and exploring examples, to planning and assembling ideas, drafting and editing, proof-reading, all the way through to publication and reflection.

And of course, at every stage, the starting point for teacher, peer or self-assessment and feedback is not a list of ingredients, but whether the writing is achieving what it is meant to achieve.

Sign up to our newsletter

You'll also receive regular updates from Teachwire with free lesson plans, great new teaching ideas, offers and more. (You can unsubscribe at any time.)

Which sectors are you interested in?

Early Years

Thank you for signing up to our emails!

You might also be interested in...

Why join Teachwire?

Get what you need to become a better teacher with unlimited access to exclusive free classroom resources and expert CPD downloads.

Exclusive classroom resource downloads

Free worksheets and lesson plans

CPD downloads, written by experts

Resource packs to supercharge your planning

Special web-only magazine editions

Educational podcasts & resources

Access to free literacy webinars

Newsletters and offers

Create free account

By signing up you agree to our terms and conditions and privacy policy .

Already have an account? Log in here

Thanks, you're almost there

To help us show you teaching resources, downloads and more you’ll love, complete your profile below.

Welcome to Teachwire!

Set up your account.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Commodi nulla quos inventore beatae tenetur.

I would like to receive regular updates from Teachwire with free lesson plans, great new teaching ideas, offers and more. (You can unsubscribe at any time.)

Log in to Teachwire

Not registered with Teachwire? Sign up for free

Reset Password

Remembered your password? Login here

The English Classroom

A GUIDE FOR PRESERVICE AND GRADUATE TEACHERS

Success Criteria

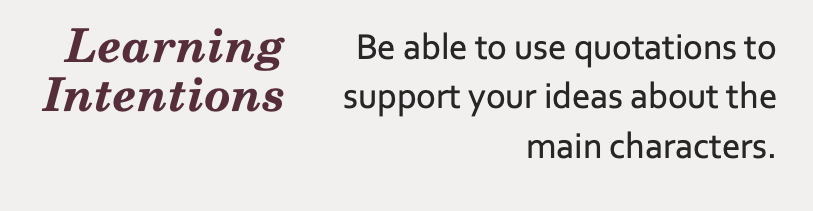

The situation.

Your students need to understand what must be demonstrated in the lesson.

The Solution

What is a success criteria.

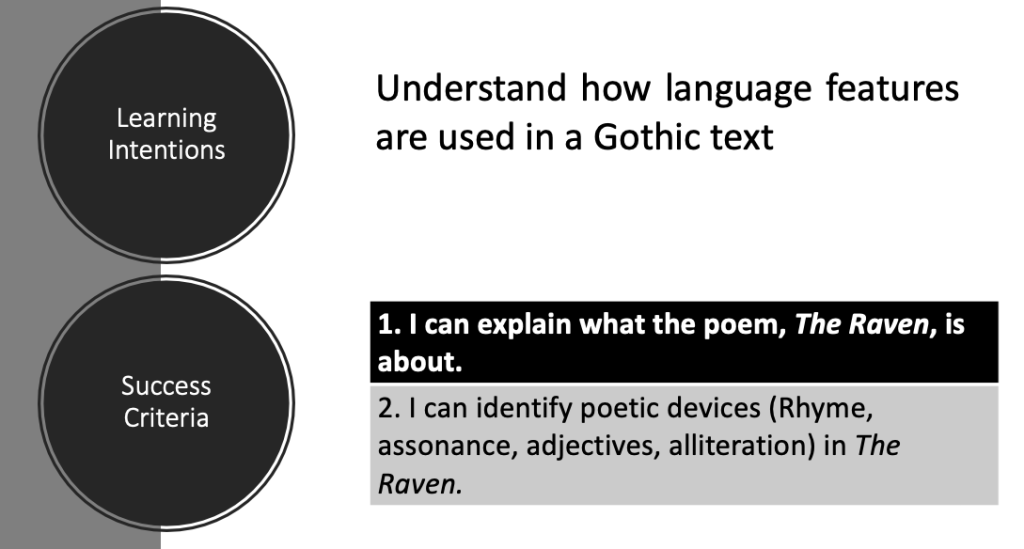

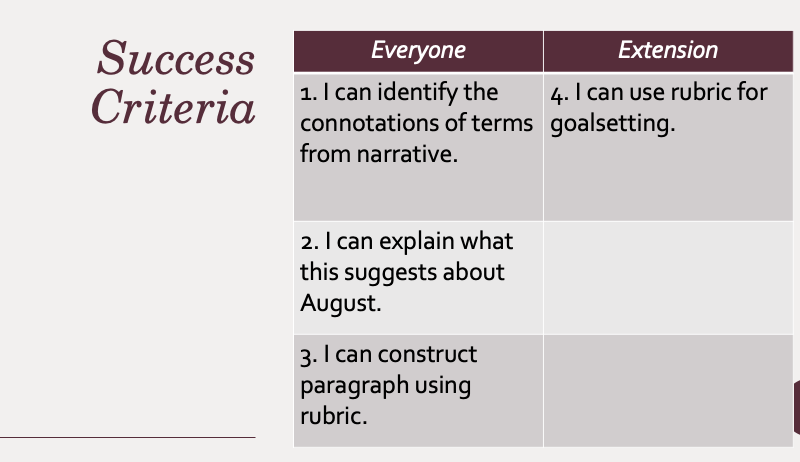

A success criteria is a set of two-four “I can” statement that contribute to a student’s overall learning during a lesson. For example, I can identify a metaphor in The Raven . It simply outlines the skills that need to be demonstrated during the lesson. The success criteria should be ticked off cyclically during the lessons, so that students understand how they are traveling with the learning.

A success criteria is much like an action plan. It outlines the smaller pieces of learning that students will complete to get to a point where the learning intention will be achieved. Below, is an example of what I use:

Here is the learning intentions presented with the success criteria:

The overall learning focused on language features in a gothic narrative. To achieve this learning, I had students look at The Raven. Now, you wouldn’t have to look at The Raven to achieve this goal – you could look at any number of gothic narrative or poems. This is the sweet spot of the success criteria and learning intention. The end goal is always the same, but you are free to adjust the road leading there. For example, we could look at poetic devices in a different poem and still achieve the learning goal.

Warning: the success criteria is not a step one, step two process. It is not a checklist. It simply outlines what students can do. This is why they are written using “I can statement”.

Differentiating Success Criteria

Aside from the above, you can also differentiate the success criteria. Some students can dig deeper into their learning than others and should be encouraged to extend themselves. If possible, give students another option that they can achieve after the central learning has been completed.

Below is the learning intention:

And the differentiated success criteria, encouraging students to use a rubric to goal-set for future learning.

Share this:

Published by The English Classroom

View all posts by The English Classroom

One thought on “ Success Criteria ”

- Pingback: Check For Understanding | Cosmik Egg

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

KS3/4 analytical writing success criteria and targets, numbered checklist

Subject: English

Age range: 11-14

Resource type: Worksheet/Activity

Last updated

22 February 2018

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

An essay writing rubric is a set of criteria that outlines what is expected in a well-crafted essay, providing students with clear guidelines for success. Effective essay writing rubrics not only evaluate the quality of the content but also assess the organization, coherence, language use, and overall structure of an essay. ...

prompt on your own. You'd be surprised how often someone comes to the Writing Center to ask for help on a paper before reading the prompt. Once they do read the prompt, they often find that it answers many of their questions. When you read the assignment prompt, you should do the following: • Look for action verbs.

Pay attention to your choice of verb. When writing Learning Goals and Success Criteria, it can be helpful to focus on selecting the right verb, which is often the first word of the sentence. • Learning Goals should refer to understanding, knowledge, skills, or application.

Resolve yourself to being lucid. Perfect essay writing requires clear and concrete words and sentences. Its vitality is that the meaning of your article will reach your readers thus your essay will be highly graded. Ensure that you do not introduce your paragraphs with the commonly used examples in class.

An academic essay is a piece of writing in which you present your position on a topic, and support that position by evidence. An essay has three main parts: introduction, body, and conclusion. In the introduction, you put forward your position (this can take the form of a question or an argument) and its relevance to the chosen topic. In the ...

The essay writing process consists of three main stages: Preparation: Decide on your topic, do your research, and create an essay outline. Writing: Set out your argument in the introduction, develop it with evidence in the main body, and wrap it up with a conclusion. Revision: Check your essay on the content, organization, grammar, spelling ...

The basic structure of an essay always consists of an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. But for many students, the most difficult part of structuring an essay is deciding how to organize information within the body. This article provides useful templates and tips to help you outline your essay, make decisions about your structure, and ...

Using the Writing Process. To complete a writing project successfully, good writers use some variation of the following process. The Writing Process. Prewriting. In this step, the writer generates ideas to write about and begins developing these ideas. Outlining a structure of ideas.

Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt. Asking Analytical Questions. Thesis. Introductions. What Do Introductions Across the Disciplines Have in Common? Anatomy of a Body Paragraph. Transitions. Tips for Organizing Your Essay. Counterargument.

The most common criticisms of markers often focus on the five broad skills below: ♦ Students need to be analytical. ♦ Students need to use evidence effectively. ♦ Students need to structure their essays logically. ♦ Students need to be critical and persuasive. ♦ Students need to write in an academic style.

Learning intention: We are learning how to write an introduction to an essay. Success criteria: I can write an introduction that: ... whiteboard, we can also provide a worked example of writing a response to a short answer question. We can demonstrate how we might select a quote or construct a topic sentence.

1. The writer creates vivid pictures of people, places, things, and events in the mind of the reader using description and sensory details. 2. The writer vividly describes experiences and events bringing them to life. 3. The writer effectively describes processes in detail. 4.

Whereas curriculum-based measurement writing (CBM-W) measures allow teachers to effectively monitor student progress at the letter-, word-, sentence-, or paragraph-writing level, CBM-W is more widely researched with beginning or early writers, and some of these metrics in isolation (e.g., words written) do not represent overall writing quality (Allen et al., 2018).

"Success criteria make the learning target, or 'it,' visible for both teachers and students by . describing what learners must know and be able to do that would demonstrate that they . have met the learning intentions for the day" (Almarode et al, 2021, Ch. 1). To illustrate the . potential of success criteria, consider the research on

Writing questions in the left-hand column helps to clarify meanings, reveal relationships, establish continuity, and strengthen memory. Also, the writing of questions sets up a perfect stage for exam-studying later [1]. Summarising the class notes into your own words will create a quick reference guide for exams and help you retain valuable ...

In my opinion, there are 6 things you should keep in mind whilst writing an English Essay. Throughout you should present a coherent, well structured argument. As obvious as it may sound, try to keep your line of argument as clear as you can for the examiner. This will ensure they understand the points you make.

Success Criteria for Critical Essays - 30 point check 1 Use the checklist below as a reminder of what is required in a Critical Essay. 2 Check your essay against this list. 3 Ensure that you have amended and improved your essay before submitting it to be marked. Have you written the task at the top?

writing lesson with Year 8: - Reflect on success criteria. - Set target against criteria based on recent classwork and their assessment. - Scaffolding creative writing with modelling. - Independent writing with criteria to support. - Peer-assessment using criteria. - Selecting a new target as necessary with the criteria allowing them to see

Boxed criteria in practice. Traditional 'success criteria' are really the wrong way round. They define 'success' in terms of the presence of ingredients, not in terms of the actual point of the writing. Boxed criteria keep the ingredients, but link them explicitly to purpose and to the reader. It's really that simple.

The Writing Rope (Sedita, 2019) supports a deeper understanding of skilled writing by organising the many skills, strategies and techniques into five overarching components. These include the compositional components of critical thinking, syntax, text structure and writing craft, and the transcription skills of spelling, handwriting and ...

A success criteria is a set of two-four "I can" statement that contribute to a student's overall learning during a lesson. For example, I can identify a metaphor in The Raven. It simply outlines the skills that need to be demonstrated during the lesson. The success criteria should be ticked off cyclically during the lessons, so that ...

All genres and ALL years | Teaching Resources. Success criteria for Writing. All genres and ALL years. Subject: English. Age range: 7-11. Resource type: Assessment and revision. File previews. doc, 849.5 KB. Success criteria for all genres in English writing, non- fiction and fiction.

Suitable for self assessment, peer assessment, teacher assessment. Created for KS3 but could be adapted for KS4 support. This numbered checklist sets out what a student should be aiming for in analytical writing (e.g. analysing the presentation of a theme, character, structure etc). Each area is coded with a number. SPAG targets are also included.