National Archives News

The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, August 1945

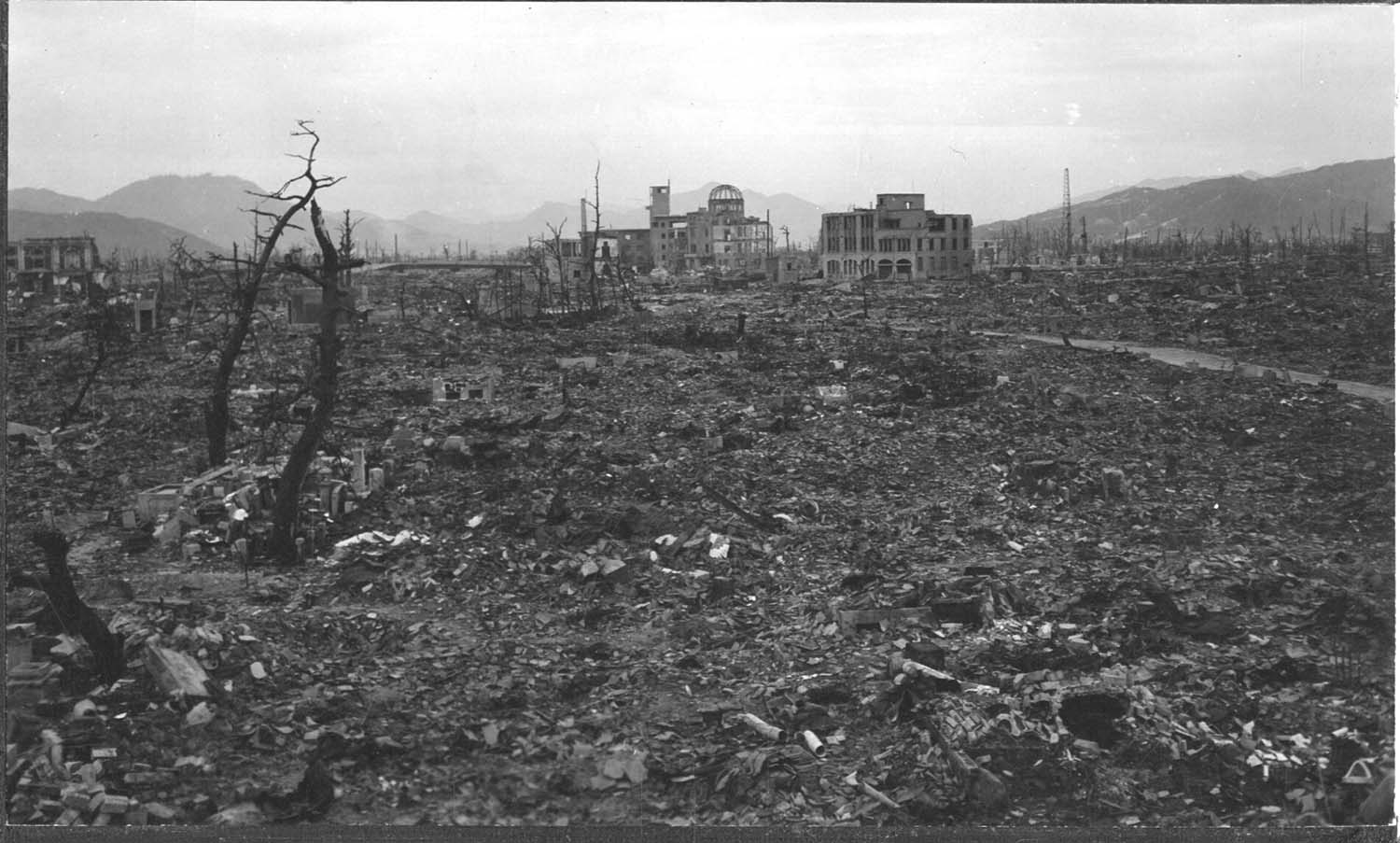

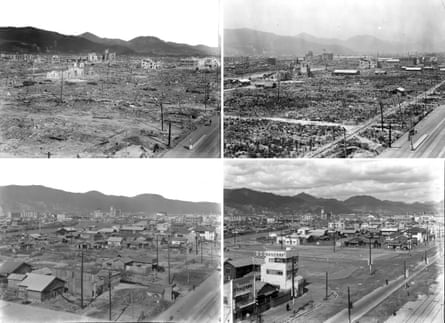

Photograph of Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. (National Archives Identifier 22345671 )

The United States bombings of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and August 9, 1945, were the first instances of atomic bombs used against humans, killing tens of thousands of people, obliterating the cities, and contributing to the end of World War II. The National Archives maintains the documents that trace the evolution of the project to develop the bombs, their use in 1945, and the aftermath.

Online Exhibits

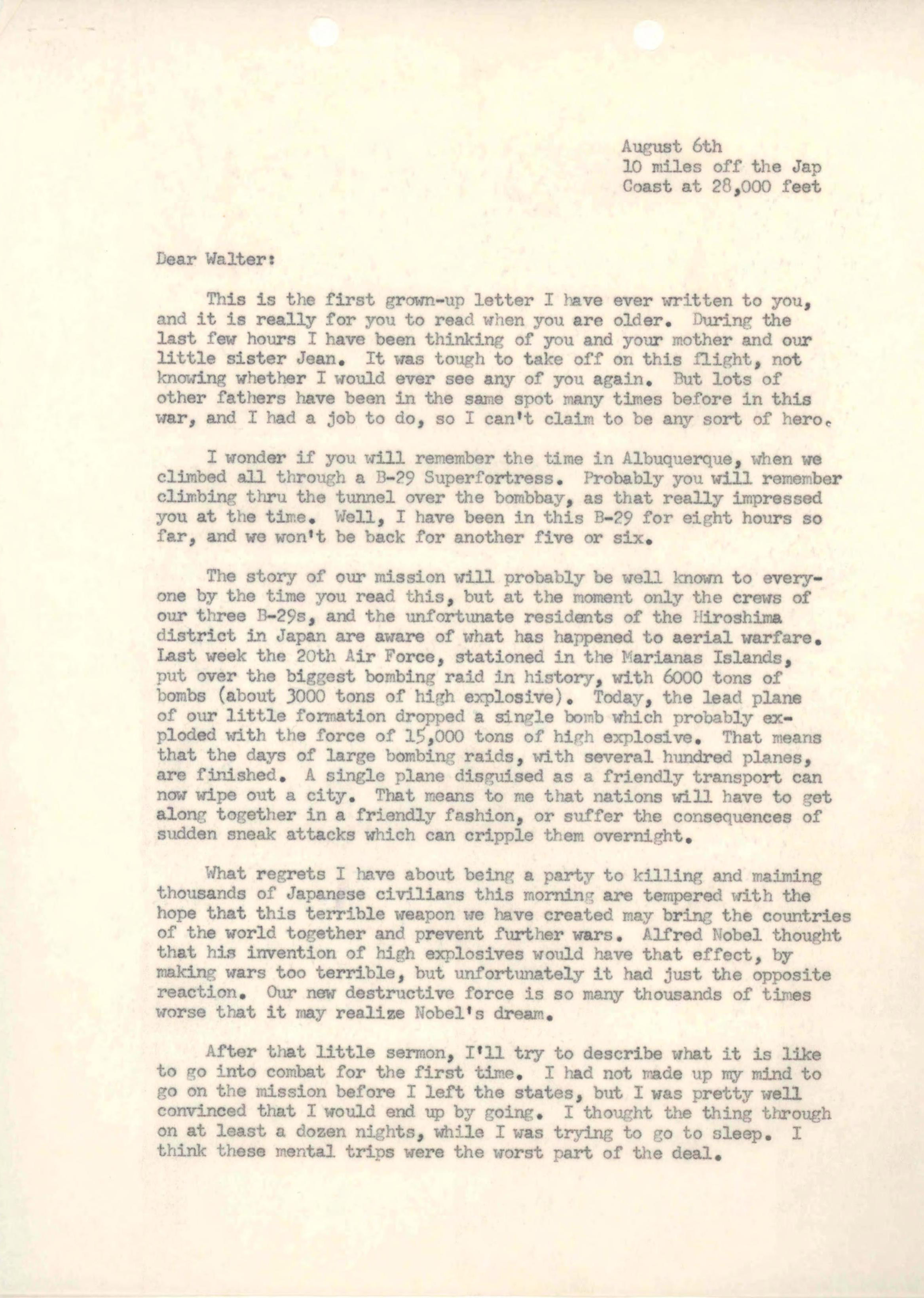

The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki features a letter written by Luis Alvarez, a physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, on August 6, 1945, after the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan.

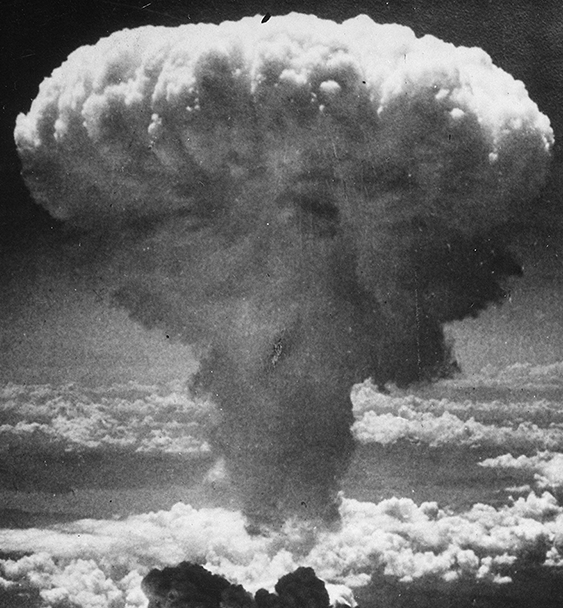

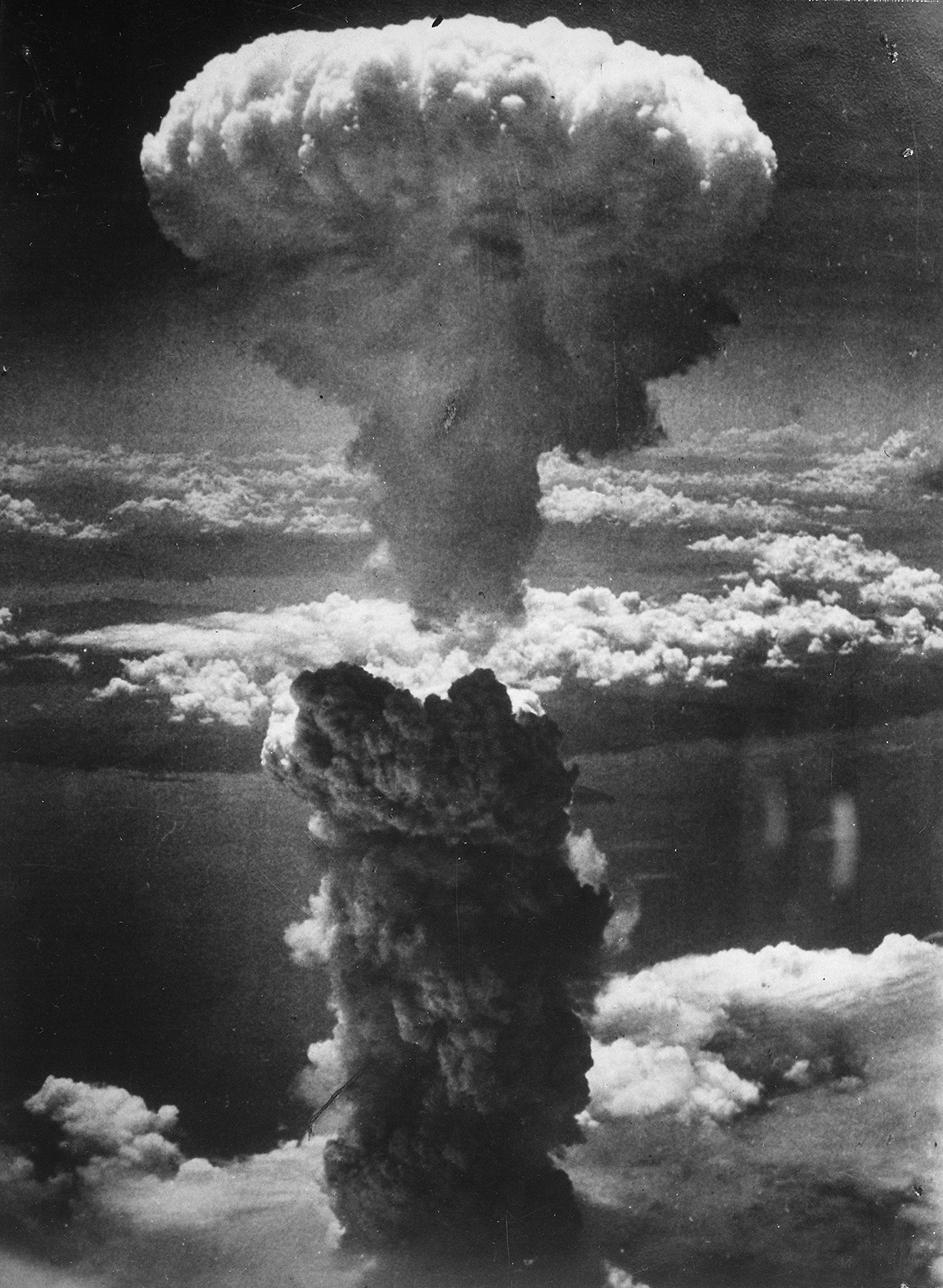

[Photograph: The atomic cloud rising over Nagasaki, Japan, August 9, 1945. National Archives Identifier 535795 ]

A People at War looks at the 509 Composite Group, the unit selected to carry the atomic bomb to Hiroshima.

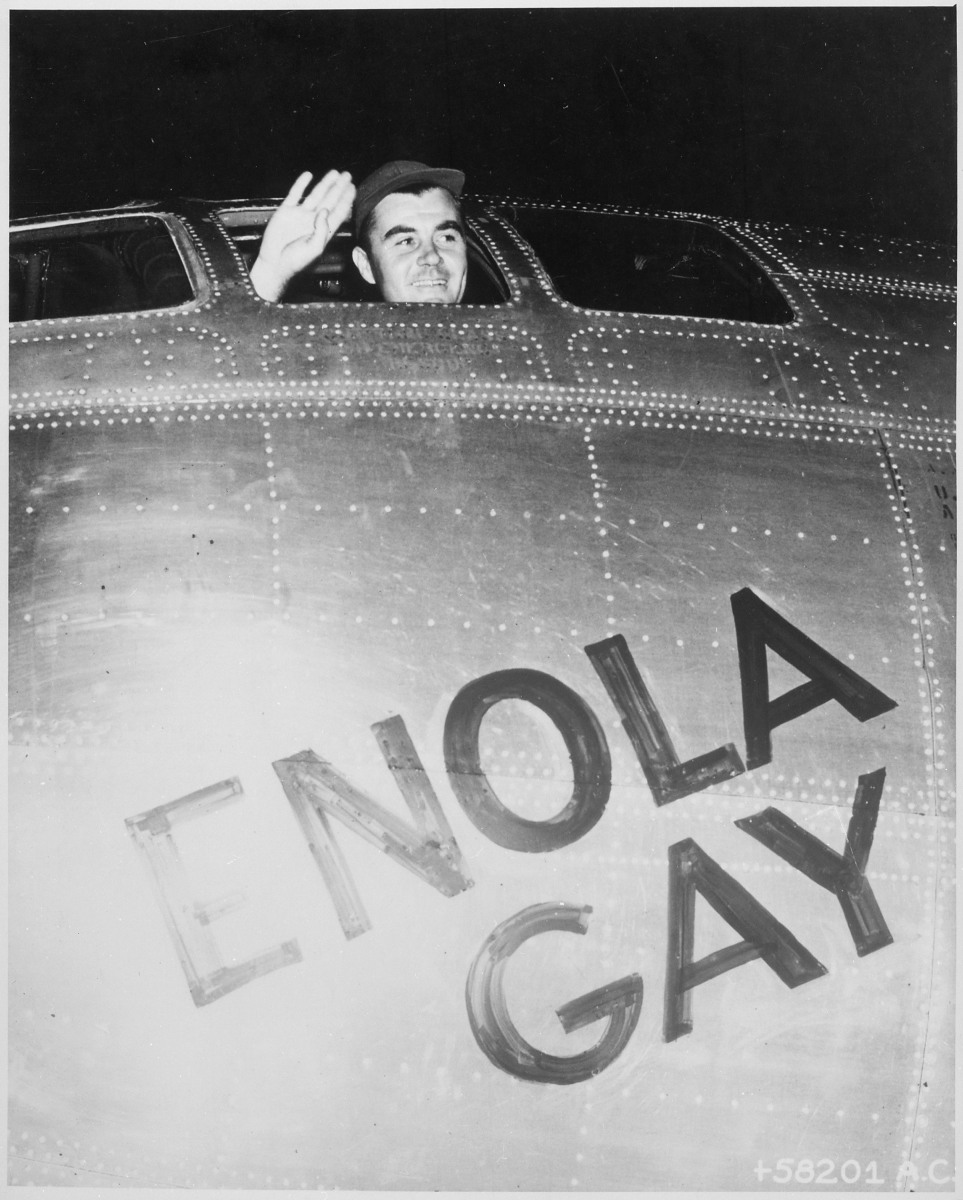

[Photograph: Col. Paul Tibbets, Jr., waves from the cockpit of the Enola Gay before departing for Hiroshima, August 6, 1945. National Archives Identifier 535737 ]

Photograph Gallery

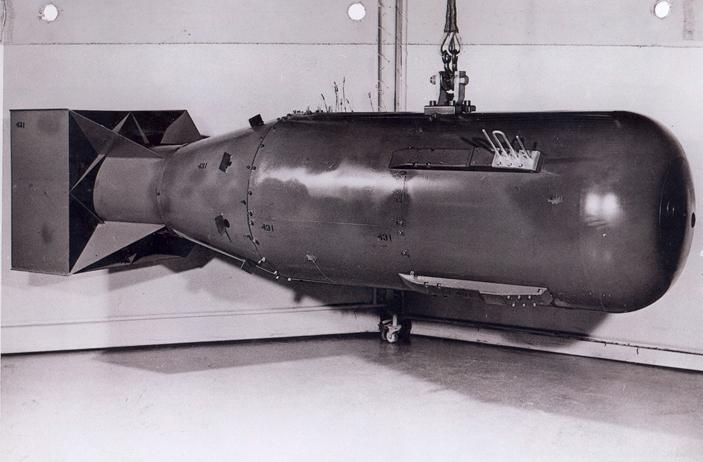

"Little Boy" atomic bomb being raised into plane on Tinian Island before the flight to Hiroshima. National Archives Identifier 76048583

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 22345671

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 22345679

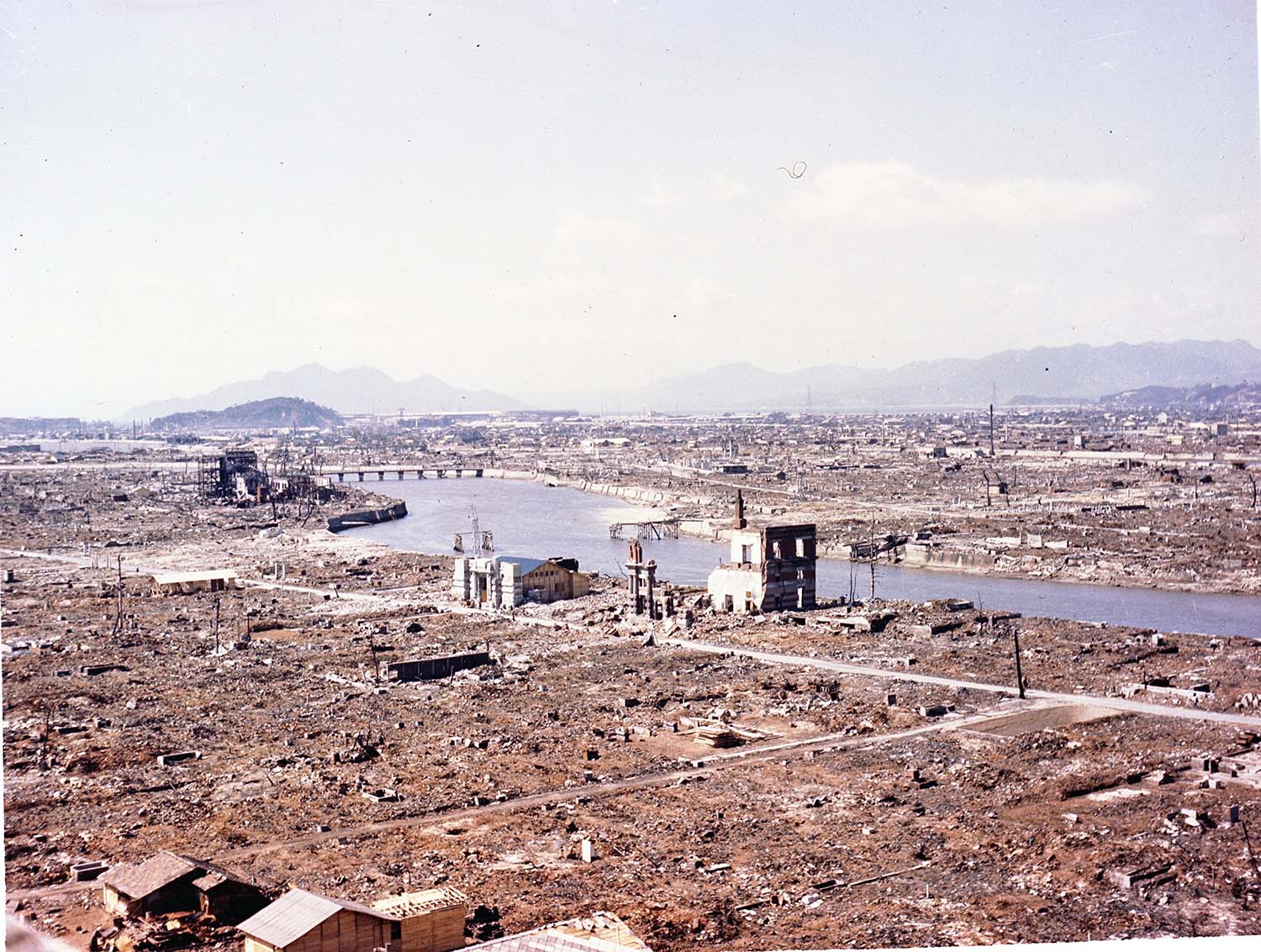

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 22345680

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 148728174

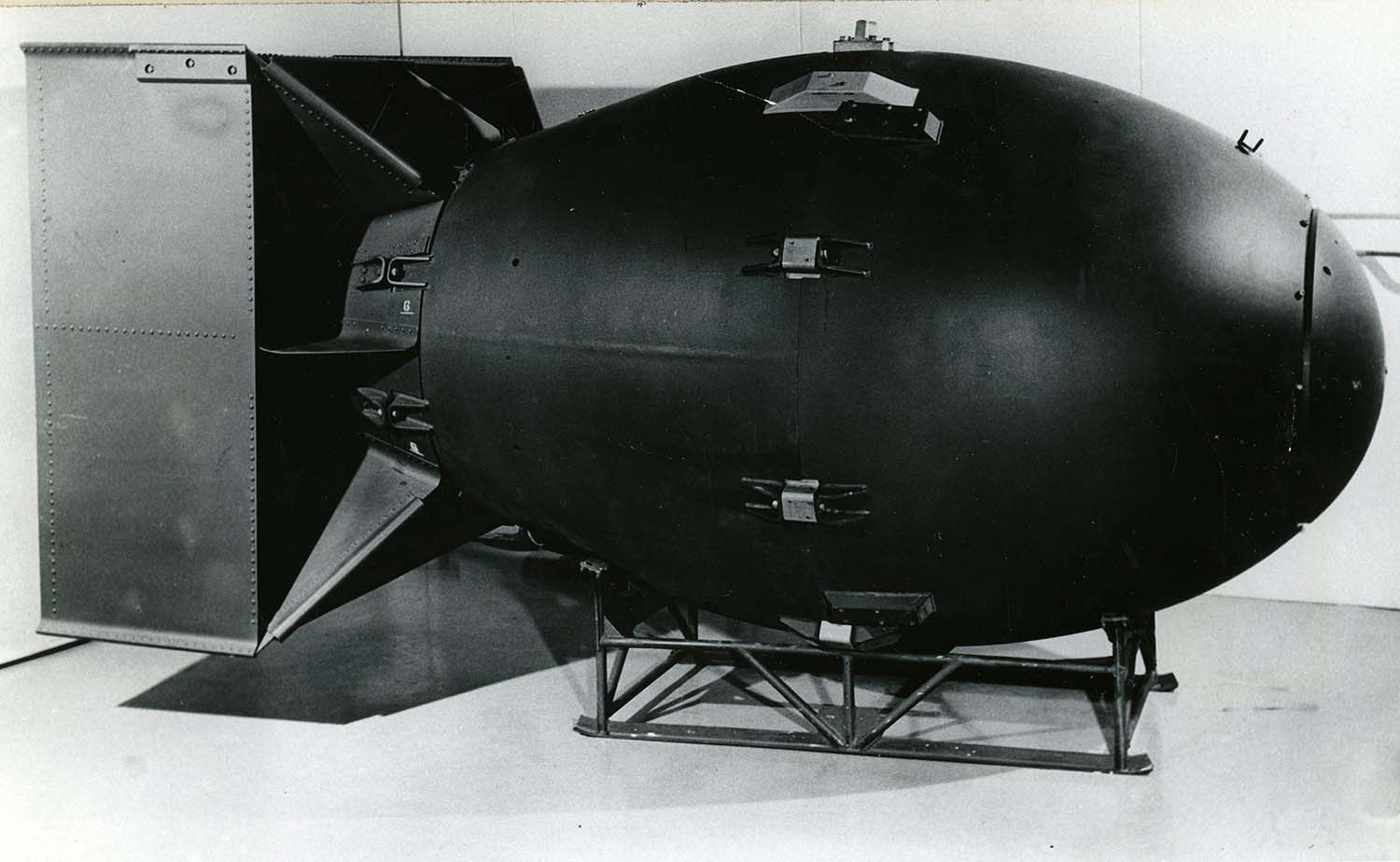

Nuclear weapon of the "Fat Man" type, the kind detonated over Nagasaki, Japan. National Archives Identifier 175539928

The atomic cloud rising over Nagasaki, Japan. National Archives Identifier 535795

Nagasaki after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 39147824

Nagasaki after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 39147850

Additional Photographs

Atomic Bomb Preparations at Tinian Island, 1945

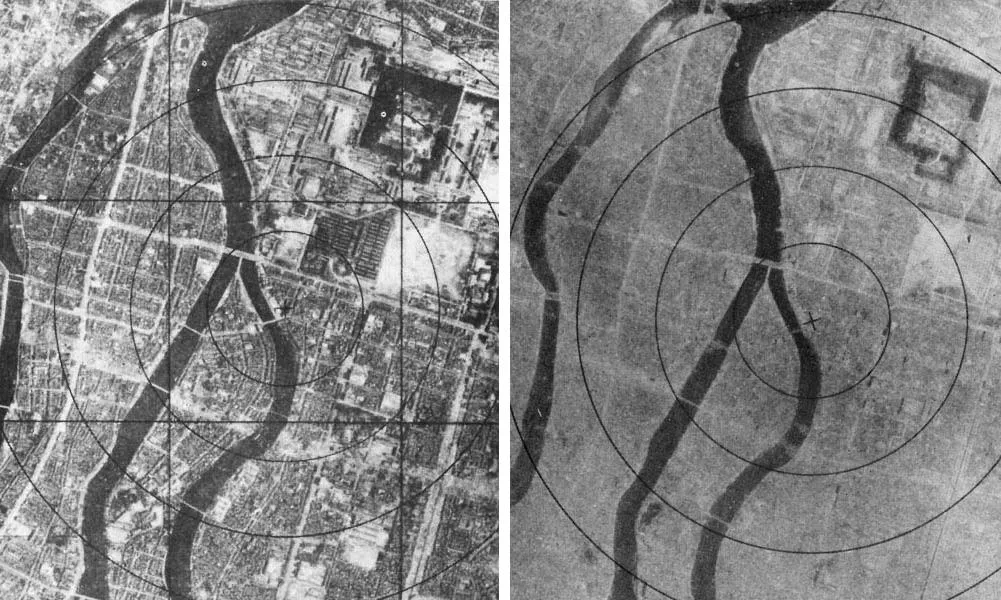

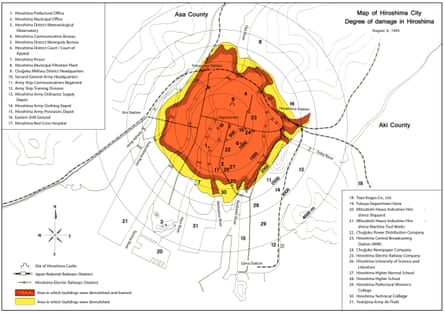

Photographs used in the report Effects of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima, Japan

Manhattan Project Notebook

Atomic bomb/Enola Gay preparations for the bombing missions

Post-bombing aerial and on-the-ground images of Hiroshima

Empty bottle of Chianti Bertolli wine signed by scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project

Archival Film

Hiroshima and Nagasaki Effects, 1945

The Last Bomb , a 1945 film, done in Technicolor, by the Army Air Forces Combat Camera Units and Motion Picture Units covering the B-29 bombing raids on Japan

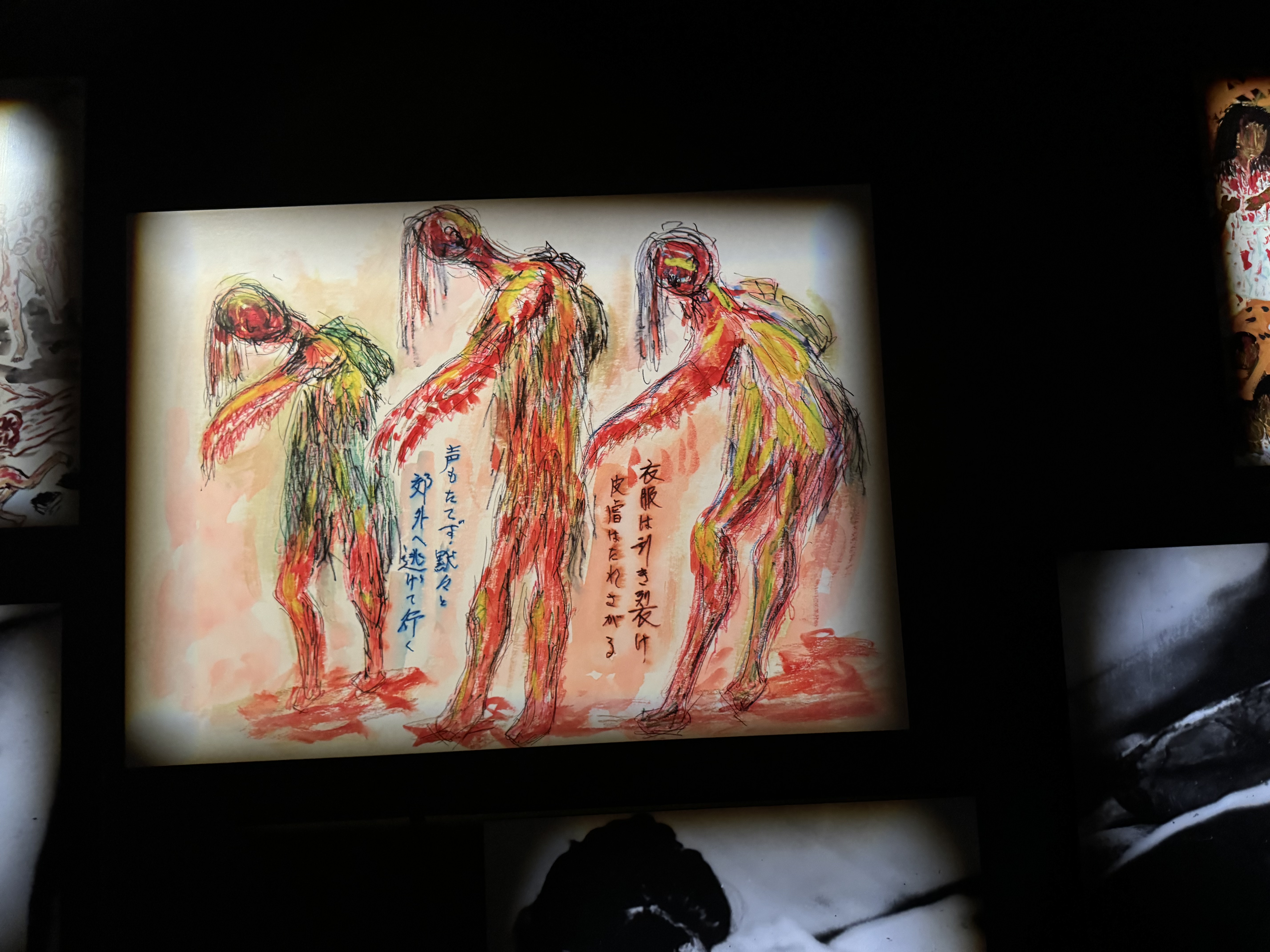

Effects on the human body of radiation from the atomic bomb

Additional Records

Photos: Atomic Bomb Preparations at Tinian Island, 1945

Atomic bomb/ Enola Gay preparations for the bombing missions

Post-Hiroshima bombing aerial and on-the-ground images

Color image of Hiroshima after bombing

Manhattan Project records from Oak Ridge, TN

Blogs and Social Media Posts

Unwritten Record: Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Unwritten Record: Witness to Destruction: Photographs and Sound Recordings Documenting the Hiroshima Bombing

Forward with Roosevelt: Found in the Archives: The Einstein Letter

Pieces of History: Little Boy: The First Atomic Bomb

Pieces of History: Harry Truman and the Bomb

Pieces of History: Morgantown Ordnance Works (part of the Manhattan Project) Panoramas, 1940–1942

Today's Document: Petition from Manhattan Project Scientists to President Truman

For Educators

Docs Teach resources on the atomic bomb

Teaching with Documents: Photographs and Pamphlet about Nuclear Fallout

Kennedy Library: “The Presidency in the Nuclear Age”

At the Presidential Libraries

Roosevelt Library: Albert Einstein’s letter to FDR regarding the atomic bomb

Truman Library: “The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb ”

Truman Library: Additional records on the bombing of Hiroshima

Truman Library: President Truman's Diary Entry for July 17, 1945 (the day before Truman learned that the United States had successfully tested the world's first atomic bomb)

Truman Library: Memo for the Record, Manhattan Project, July 20, 1945

Truman Library: Petition from Leo Szilard and other scientists to President Truman

Eisenhower Library: Atoms for Peace

Kennedy Library: “ The Presidency in the Nuclear Age: The Race to Build the Bomb and the Decision to Use It”

The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II

A Collection of Primary Sources

Updated National Security Archive Posting Marks 75th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombings of Japan and the End of World War II

Extensive Compilation of Primary Source Documents Explores Manhattan Project, Eisenhower’s Early Misgivings about First Nuclear Use, Curtis LeMay and the Firebombing of Tokyo, Debates over Japanese Surrender Terms, Atomic Targeting Decisions, and Lagging Awareness of Radiation Effects

Washington, D.C., August 4, 2020 – To mark the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the National Security Archive is updating and reposting one of its most popular e-books of the past 25 years.

While U.S. leaders hailed the bombings at the time and for many years afterwards for bringing the Pacific war to an end and saving untold thousands of American lives, that interpretation has since been seriously challenged. Moreover, ethical questions have shrouded the bombings which caused terrible human losses and in succeeding decades fed a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union and now Russia and others.

Three-quarters of a century on, Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain emblematic of the dangers and human costs of warfare, specifically the use of nuclear weapons. Since these issues will be subjects of hot debate for many more years, the Archive has once again refreshed its compilation of declassified U.S. government documents and translated Japanese records that first appeared on these pages in 2005.

* * * * *

Introduction

By William Burr

The 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 is an occasion for sober reflection. In Japan and elsewhere around the world, each anniversary is observed with great solemnity. The bombings were the first time that nuclear weapons had been detonated in combat operations. They caused terrible human losses and destruction at the time and more deaths and sickness in the years ahead from the radiation effects. And the U.S. bombings hastened the Soviet Union’s atomic bomb project and have fed a big-power nuclear arms race to this day. Thankfully, nuclear weapons have not been exploded in war since 1945, perhaps owing to the taboo against their use shaped by the dropping of the bombs on Japan.

Along with the ethical issues involved in the use of atomic and other mass casualty weapons, why the bombs were dropped in the first place has been the subject of sometimes heated debate. As with all events in human history, interpretations vary and readings of primary sources can lead to different conclusions. Thus, the extent to which the bombings contributed to the end of World War II or the beginning of the Cold War remain live issues. A significant contested question is whether, under the weight of a U.S. blockade and massive conventional bombing, the Japanese were ready to surrender before the bombs were dropped. Also still debated is the impact of the Soviet declaration of war and invasion of Manchuria, compared to the atomic bombings, on the Japanese decision to surrender. Counterfactual issues are also disputed, for example whether there were alternatives to the atomic bombings, or would the Japanese have surrendered had a demonstration of the bomb been used to produced shock and awe. Moreover, the role of an invasion of Japan in U.S. planning remains a matter of debate, with some arguing that the bombings spared many thousands of American lives that otherwise would have been lost in an invasion.

Those and other questions will be subjects of discussion well into the indefinite future. Interested readers will continue to absorb the fascinating historical literature on the subject. Some will want to read declassified primary sources so they can further develop their own thinking about the issues. Toward that end, in 2005, at the time of the 60th anniversary of the bombings, staff at the National Security Archive compiled and scanned a significant number of declassified U.S. government documents to make them more widely available. The documents cover multiple aspects of the bombings and their context. Also included, to give a wider perspective, were translations of Japanese documents not widely available before. Since 2005, the collection has been updated. This latest iteration of the collection includes corrections, a few minor revisions, and updated footnotes to take into account recently published secondary literature.

2015 Update

August 4, 2015 – A few months after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, General Dwight D. Eisenhower commented during a social occasion “how he had hoped that the war might have ended without our having to use the atomic bomb.” This virtually unknown evidence from the diary of Robert P. Meiklejohn, an assistant to Ambassador W. Averell Harriman, published for the first time today by the National Security Archive, confirms that the future President Eisenhower had early misgivings about the first use of atomic weapons by the United States. General George C. Marshall is the only high-level official whose contemporaneous (pre-Hiroshima) doubts about using the weapons against cities are on record.

On the 70th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the National Security Archive updates its 2005 publication of the most comprehensive on-line collection of declassified U.S. government documents on the first use of the atomic bomb and the end of the war in the Pacific. This update presents previously unpublished material and translations of difficult-to-find records. Included are documents on the early stages of the U.S. atomic bomb project, Army Air Force General Curtis LeMay’s report on the firebombing of Tokyo (March 1945), Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s requests for modification of unconditional surrender terms, Soviet documents relating to the events, excerpts from the Robert P. Meiklejohn diaries mentioned above, and selections from the diaries of Walter J. Brown, special assistant to Secretary of State James Byrnes.

The original 2005 posting included a wide range of material, including formerly top secret "Magic" summaries of intercepted Japanese communications and the first-ever full translations from the Japanese of accounts of high level meetings and discussions in Tokyo leading to the Emperor’s decision to surrender. Also documented are U.S. decisions to target Japanese cities, pre-Hiroshima petitions by scientists questioning the military use of the A-bomb, proposals for demonstrating the effects of the bomb, debates over whether to modify unconditional surrender terms, reports from the bombing missions of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and belated top-level awareness of the radiation effects of atomic weapons.

The documents can help readers to make up their own minds about long-standing controversies such as whether the first use of atomic weapons was justified, whether President Harry S. Truman had alternatives to atomic attacks for ending the war, and what the impact of the Soviet declaration of war on Japan was. Since the 1960s, when the declassification of important sources began, historians have engaged in vigorous debate over the bomb and the end of World War II. Drawing on sources at the National Archives and the Library of Congress as well as Japanese materials, this electronic briefing book includes key documents that historians of the events have relied upon to present their findings and advance their interpretations.

The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II: A Collection of Primary Sources

Seventy years ago this month, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, and the Japanese government surrendered to the United States and its allies. The nuclear age had truly begun with the first military use of atomic weapons. With the material that follows, the National Security Archive publishes the most comprehensive on-line collection to date of declassified U.S. government documents on the atomic bomb and the end of the war in the Pacific. Besides material from the files of the Manhattan Project, this collection includes formerly “Top Secret Ultra” summaries and translations of Japanese diplomatic cable traffic intercepted under the “Magic” program. Moreover, the collection includes for the first time translations from Japanese sources of high level meetings and discussions in Tokyo, including the conferences when Emperor Hirohito authorized the final decision to surrender. [1]

Ever since the atomic bombs were exploded over Japanese cities, historians, social scientists, journalists, World War II veterans, and ordinary citizens have engaged in intense controversy about the events of August 1945. John Hersey’s Hiroshima , first published in the New Yorker in 1946 encouraged unsettled readers to question the bombings while church groups and some commentators, most prominently Norman Cousins, explicitly criticized them. Former Secretary of War Henry Stimson found the criticisms troubling and published an influential justification for the attacks in Harper’s . [2] During the 1960s the availability of primary sources made historical research and writing possible and the debate became more vigorous. Historians Herbert Feis and Gar Alperovitz raised searching questions about the first use of nuclear weapons and their broader political and diplomatic implications. The controversy, especially the arguments made by Alperovitz and others about “atomic diplomacy” quickly became caught up in heated debates over Cold War “revisionism.” The controversy simmered over the years with major contributions by Martin Sherwin and Barton J. Bernstein but it became explosive during the mid-1990s when curators at the National Air and Space Museum met the wrath of the Air Force Association over a proposed historical exhibit on the Enola Gay. [3] The NASM exhibit was drastically scaled-down but historians and journalist continued to engage in the debate. Alperovitz, Bernstein, and Sherwin made new contributions as did other historians, social scientists, and journalists including Richard B. Frank, Herbert Bix, Sadao Asada, Kai Bird, Robert James Maddox, Sean Malloy, Robert P. Newman, Robert S. Norris, Tsuyoshi Hagesawa, and J. Samuel Walker. [4]

The continued controversy has revolved around the following, among other, questions:

- were the atomic strikes necessary primarily to avert an invasion of Japan in November 1945?

- Did Truman authorize the use of atomic bombs for diplomatic-political reasons-- to intimidate the Soviets--or was his major goal to force Japan to surrender and bring the war to an early end?

- If ending the war quickly was the most important motivation of Truman and his advisers to what extent did they see an “atomic diplomacy” capability as a “bonus”?

- To what extent did subsequent justification for the atomic bomb exaggerate or misuse wartime estimates for U.S. casualties stemming from an invasion of Japan?

- Were there alternatives to the use of the weapons? If there were, what were they and how plausible are they in retrospect? Why were alternatives not pursued?

- How did the U.S. government plan to use the bombs? What concepts did war planners use to select targets? To what extent were senior officials interested in looking at alternatives to urban targets? How familiar was President Truman with the concepts that led target planners chose major cities as targets?

- What did senior officials know about the effects of atomic bombs before they were first used. How much did top officials know about the radiation effects of the weapons?

- Did President Truman make a decision, in a robust sense, to use the bomb or did he inherit a decision that had already been made?

- Were the Japanese ready to surrender before the bombs were dropped? To what extent had Emperor Hirohito prolonged the war unnecessarily by not seizing opportunities for surrender?

- If the United States had been more flexible about the demand for “unconditional surrender” by explicitly or implicitly guaranteeing a constitutional monarchy would Japan have surrendered earlier than it did?

- How decisive was the atomic bombings to the Japanese decision to surrender?

- Was the bombing of Nagasaki unnecessary? To the extent that the atomic bombing was critically important to the Japanese decision to surrender would it have been enough to destroy one city?

- Would the Soviet declaration of war have been enough to compel Tokyo to admit defeat?

- Was the dropping of the atomic bombs morally justifiable?

This compilation will not attempt to answer these questions or use primary sources to stake out positions on any of them. Nor is it an attempt to substitute for the extraordinary rich literature on the atomic bombings and the end of World War II. Nor does it include any of the interviews, documents prepared after the events, and post-World War II correspondence, etc. that participants in the debate have brought to bear in framing their arguments. Originally this collection did not include documents on the origins and development of the Manhattan Project, although this updated posting includes some significant records for context. By providing access to a broad range of U.S. and Japanese documents, mainly from the spring and summer of 1945, interested readers can see for themselves the crucial source material that scholars have used to shape narrative accounts of the historical developments and to frame their arguments about the questions that have provoked controversy over the years. To help readers who are less familiar with the debates, commentary on some of the documents will point out, although far from comprehensively, some of the ways in which they have been interpreted. With direct access to the documents, readers may develop their own answers to the questions raised above. The documents may even provoke new questions.

Contributors to the historical controversy have deployed the documents selected here to support their arguments about the first use of nuclear weapons and the end of World War II. The editor has closely reviewed the footnotes and endnotes in a variety of articles and books and selected documents cited by participants on the various sides of the controversy. [5] While the editor has a point of view on the issues, to the greatest extent possible he has tried to not let that influence document selection, e.g., by selectively withholding or including documents that may buttress one point of view or the other. The task of compilation involved consultation of primary sources at the National Archives, mainly in Manhattan Project files held in the records of the Army Corps of Engineers, Record Group 77, but also in the archival records of the National Security Agency. Private collections were also important, such as the Henry L. Stimson Papers held at Yale University (although available on microfilm, for example, at the Library of Congress) and the papers of W. Averell Harriman at the Library of Congress. To a great extent the documents selected for this compilation have been declassified for years, even decades; the most recent declassifications were in the 1990s.

The U.S. documents cited here will be familiar to many knowledgeable readers on the Hiroshima-Nagasaki controversy and the history of the Manhattan Project. To provide a fuller picture of the transition from U.S.-Japanese antagonism to reconciliation, the editor has done what could be done within time and resource constraints to present information on the activities and points of view of Japanese policymakers and diplomats. This includes a number of formerly top secret summaries of intercepted Japanese diplomatic communications, which enable interested readers to form their own judgments about the direction of Japanese diplomacy in the weeks before the atomic bombings. Moreover, to shed light on the considerations that induced Japan’s surrender, this briefing book includes new translations of Japanese primary sources on crucial events, including accounts of the conferences on August 9 and 14, where Emperor Hirohito made decisions to accept Allied terms of surrender.

[ Editor’s Note: Originally prepared in July 2005 this posting has been updated, with new documents, changes in organization, and other editorial changes. As noted, some documents relating to the origins of the Manhattan Project have been included in addition to entries from the Robert P. Meiklejohn diaries and translations of a few Soviet documents, among other items. Moreover, recent significant contributions to the scholarly literature have been taken into account.]

I. Background on the U.S. Atomic Project

Documents 1A-C: Report of the Uranium Committee

1A . Arthur H. Compton, National Academy of Sciences Committee on Atomic Fission, to Frank Jewett, President, National Academy of Sciences, 17 May 1941, Secret

1B . Report to the President of the National Academy of Sciences by the Academy Committee on Uranium, 6 November 1941, Secret

1C . Vannevar Bush, Director, Office of Scientific Research and Development, to President Roosevelt, 27 November 1941, Secret

Source: National Archives, Records of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Record Group 227 (hereinafter RG 227), Bush-Conant papers microfilm collection, Roll 1, Target 2, Folder 1, "S-1 Historical File, Section A (1940-1941)."

This set of documents concerns the work of the Uranium Committee of the National Academy of Sciences, an exploratory project that was the lead-up to the actual production effort undertaken by the Manhattan Project. The initial report, May 1941, showed how leading American scientists grappled with the potential of nuclear energy for military purposes. At the outset, three possibilities were envisioned: radiological warfare, a power source for submarines and ships, and explosives. To produce material for any of those purposes required a capability to separate uranium isotopes in order to produce fissionable U-235. Also necessary for those capabilities was the production of a nuclear chain reaction. At the time of the first report, various methods for producing a chain reaction were envisioned and money was being budgeted to try them out.

Later that year, the Uranium Committee completed its report and OSRD Chairman Vannevar Bush reported the findings to President Roosevelt: As Bush emphasized, the U.S. findings were more conservative than those in the British MAUD report: the bomb would be somewhat “less effective,” would take longer to produce, and at a higher cost. One of the report’s key findings was that a fission bomb of superlatively destructive power will result from bringing quickly together a sufficient mass of element U235.” That was a certainty, “as sure as any untried prediction based upon theory and experiment can be.” The critically important task was to develop ways and means to separate highly enriched uranium from uranium-238. To get production going, Bush wanted to establish a “carefully chosen engineering group to study plans for possible production.” This was the basis of the Top Policy Group, or the S-1 Committee, which Bush and James B. Conant quickly established. [6]

In its discussion of the effects of an atomic weapon, the committee considered both blast and radiological damage. With respect to the latter, “It is possible that the destructive effects on life caused by the intense radioactivity of the products of the explosion may be as important as those of the explosion itself.” This insight was overlooked when top officials of the Manhattan Project considered the targeting of Japan during 1945. [7]

Documents 2A-B: Going Ahead with the Bomb

2A : Vannevar Bush to President Roosevelt, 9 March 1942, with memo from Roosevelt attached, 11 March 1942, Secret

2B : Vannevar Bush to President Roosevelt, 16 December 1942, Secret (report not attached)

Sources: 2A: RG 227, Bush-Conant papers microfilm collection, Roll 1, Target 2, Folder 1, "S-1 Historical File, Section II (1941-1942): 2B: Bush-Conant papers, S-1 Historical File, Reports to and Conferences with the President (1942-1944)

The Manhattan Project never had an official charter establishing it and defining its mission, but these two documents are the functional equivalent of a charter, in terms of presidential approvals for the mission, not to mention for a huge budget. In a progress report, Bush told President Roosevelt that the bomb project was on a pilot plant basis, but not yet at the production stage. By the summer, once “production plants” would be at work, he proposed that the War Department take over the project. In reply, Roosevelt wrote a short memo endorsing Bush’s ideas as long as absolute secrecy could be maintained. According to Robert S. Norris, this was “the fateful decision” to turn over the atomic project to military control. [8]

Some months later, with the Manhattan Project already underway and under the direction of General Leslie Grove, Bush outlined to Roosevelt the effort necessary to produce six fission bombs. With the goal of having enough fissile material by the first half of 1945 to produce the bombs, Bush was worried that the Germans might get there first. Thus, he wanted Roosevelt’s instructions as to whether the project should be “vigorously pushed throughout.” Unlike the pilot plant proposal described above, Bush described a real production order for the bomb, at an estimated cost of a “serious figure”: $400 million, which was an optimistic projection given the eventual cost of $1.9 billion. To keep the secret, Bush wanted to avoid a “ruinous” appropriations request to Congress and asked Roosevelt to ask Congress for the necessary discretionary funds. Initialed by President Roosevelt (“VB OK FDR”), this may have been the closest that he came to a formal approval of the Manhattan Project.

Document 3 : Memorandum by Leslie R. Grove, “Policy Meeting, 5/5/43,” Top Secret

Source: National Archives, Record Group 77, Records of the Army Corps of Engineers (hereinafter RG 77), Manhattan Engineering District (MED), Minutes of the Military Policy Meeting (5 May 1943), Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Roll 3, Target 6, Folder 23, “Military Policy Committee, Minutes of Meetings”

Before the Manhattan Project had produced any weapons, senior U.S. government officials had Japanese targets in mind. Besides discussing programmatic matters (e.g., status of gaseous diffusion plants, heavy water production for reactors, and staffing at Las Alamos), the participants agreed that the first use could be Japanese naval forces concentrated at Truk Harbor, an atoll in the Caroline Islands. If there was a misfire the weapon would be difficult for the Japanese to recover, which would not be the case if Tokyo was targeted. Targeting Germany was rejected because the Germans were considered more likely to “secure knowledge” from a defective weapon than the Japanese. That is, the United States could possibly be in danger if the Nazis acquired more knowledge about how to build a bomb. [9]

Document 4 : Memo from General Groves to the Chief of Staff [Marshall], “Atomic Fission Bombs – Present Status and Expected Progress,” 7 August 1944, Top Secret, excised copy

Source: RG 77, Correspondence ("Top Secret") of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, file 25M

This memorandum from General Groves to General Marshall captured how far the Manhattan Project had come in less than two years since Bush’s December 1942 report to President Roosevelt . Groves did not mention this but around the time he wrote this the Manhattan Project had working at its far-flung installations over 125,000 people ; taking into account high labor turnover some 485,000 people worked on the project (1 out of every 250 people in the country at that time). What these people were laboring to construct, directly or indirectly, were two types of weapons—a gun-type weapon using U-235 and an implosion weapon using plutonium (although the possibility of U-235 was also under consideration). As the scientists had learned, a gun-type weapon based on plutonium was “impossible” because that element had an “unexpected property”: spontaneous neutron emissions would cause the weapon to “fizzle.” [10] For both the gun-type and the implosion weapons, a production schedule had been established and both would be available during 1945. The discussion of weapons effects centered on blast damage models; radiation and other effects were overlooked.

Document 5 : Memorandum from Vannevar Bush and James B. Conant, Office of Scientific Research and Development, to Secretary of War, September 30, 1944, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, Harrison-Bundy Files (H-B Files), folder 69 (copy from microfilm)

While Groves worried about the engineering and production problems, key War Department advisers were becoming troubled over the diplomatic and political implications of these enormously powerful weapons and the dangers of a global nuclear arms race. Concerned that President Roosevelt had an overly “cavalier” belief about the possibility of maintaining a post-war Anglo-American atomic monopoly, Bush and Conant recognized the limits of secrecy and wanted to disabuse senior officials of the notion that an atomic monopoly was possible. To suggest alternatives, they drafted this memorandum about the importance of the international exchange of information and international inspection to stem dangerous nuclear competition. [11]

Documents 6A-D: President Truman Learns the Secret:

6A : Memorandum for the Secretary of War from General L. R. Groves, “Atomic Fission Bombs,” April 23, 1945

6B : Memorandum discussed with the President, April 25, 1945

6C : [Untitled memorandum by General L.R. Groves, April 25, 1945

6D : Diary Entry, April 25, 1945

Sources: A: RG 77, Commanding General’s file no. 24, tab D; B: Henry Stimson Diary, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress); C: Source: Record Group 200, Papers of General Leslie R. Groves, Correspondence 1941-1970, box 3, “F”; D: Henry Stimson Diary, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress)

Soon after he was sworn in as president following President Roosevelt’s death, Harry Truman learned about the top secret Manhattan Project from a briefing from Secretary of War Stimson and Manhattan Project chief General Groves, who went through the “back door” to escape the watchful press. Stimson, who later wrote up the meeting in his diary, also prepared a discussion paper, which raised broader policy issues associated with the imminent possession of “the most terrible weapon ever known in human history.” In a background report prepared for the meeting, Groves provided a detailed overview of the bomb project from the raw materials to processing nuclear fuel to assembling the weapons to plans for using them, which were starting to crystallize.

With respect to the point about assembling the weapons, the first gun-type weapon “should be ready about 1 August 1945” while an implosion weapon would also be available that month. “The target is and was always expected to be Japan.” The question whether Truman “inherited assumptions” from the Roosevelt administration that that the bomb would be used has been a controversial one. Alperovitz and Sherwin have argued that Truman made “a real decision” to use the bomb on Japan by choosing “between various forms of diplomacy and warfare.” In contrast, Bernstein found that Truman “never questioned [the] assumption” that the bomb would and should be used. Norris also noted that “Truman’s `decision’ was a decision not to override previous plans to use the bomb.” [12]

II. Targeting Japan

Document 7 : Commander F. L. Ashworth to Major General L.R. Groves, “The Base of Operations of the 509 th Composite Group,” February 24, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5g

The force of B-29 nuclear delivery vehicles that was being readied for first nuclear use—the Army Air Force’s 509 th Composite Group—required an operational base in the Western Pacific. In late February 1945, months before atomic bombs were ready for use, the high command selected Tinian, an island in the Northern Marianas Islands, for that base.

Document 8 : Headquarters XXI Bomber Command, “Tactical Mission Report, Mission No. 40 Flown 10 March 1945,”n.d., Secret

Source: Library of Congress, Curtis LeMay Papers, Box B-36

As part of the war with Japan, the Army Air Force waged a campaign to destroy major industrial centers with incendiary bombs. This document is General Curtis LeMay’s report on the firebombing of Tokyo--“the most destructive air raid in history”--which burned down over 16 square miles of the city, killed up to 100,000 civilians (the official figure was 83,793), injured more than 40,000, and made over 1 million homeless. [13] According to the “Foreword,” the purpose of the raid, which dropped 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs, was to destroy industrial and strategic targets “ not to bomb indiscriminately civilian populations.” Air Force planners, however, did not distinguish civilian workers from the industrial and strategic structures that they were trying to destroy.

The killing of workers in the urban-industrial sector was one of the explicit goals of the air campaign against Japanese cities. According to a Joint Chiefs of Staff report on Japanese target systems, expected results from the bombing campaign included: “The absorption of man-hours in repair and relief; the dislocation of labor by casualty; the interruption of public services necessary to production, and above all the destruction of factories engaged in war industry.” While Stimson would later raise questions about the bombing of Japanese cities, he was largely disengaged from the details (as he was with atomic targeting). [14]

Firebombing raids on other cities followed Tokyo, including Osaka, Kobe, Yokahama, and Nagoya, but with fewer casualties (many civilians had fled the cities). For some historians, the urban fire-bombing strategy facilitated atomic targeting by creating a “new moral context,” in which earlier proscriptions against intentional targeting of civilians had eroded. [15]

Document 9 : Notes on Initial Meeting of Target Committee, May 2, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5d (copy from microfilm)

On 27 April, military officers and nuclear scientists met to discuss bombing techniques, criteria for target selection, and overall mission requirements. The discussion of “available targets” included Hiroshima, the “largest untouched target not on the 21 st Bomber Command priority list.” But other targets were under consideration, including Yawata (northern Kyushu), Yokohama, and Tokyo (even though it was practically “rubble.”) The problem was that the Air Force had a policy of “laying waste” to Japan’s cities which created tension with the objective of reserving some urban targets for nuclear destruction. [16]

Document 10 : Memorandum from J. R. Oppenheimer to Brigadier General Farrell, May 11, 1945

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5g (copy from microfilm)

As director of Los Alamos Laboratory, Oppenheimer’s priority was producing a deliverable bomb, but not so much the effects of the weapon on the people at the target. In keeping with General Groves’ emphasis on compartmentalization, the Manhattan Project experts on the effects of radiation on human biology were at the MetLab and other offices and had no interaction with the production and targeting units. In this short memorandum to Groves’ deputy, General Farrell, Oppenheimer explained the need for precautions because of the radiological dangers of a nuclear detonation. The initial radiation from the detonation would be fatal within a radius of about 6/10ths of a mile and “injurious” within a radius of a mile. The point was to keep the bombing mission crew safe; concern about radiation effects had no impact on targeting decisions. [17]

Document 11 : Memorandum from Major J. A. Derry and Dr. N.F. Ramsey to General L.R. Groves, “Summary of Target Committee Meetings on 10 and 11 May 1945,” May 12, 1945, Top Secret

Scientists and officers held further discussion of bombing mission requirements, including height of detonation, weather, radiation effects (Oppenheimer’s memo), plans for possible mission abort, and the various aspects of target selection, including priority cities (“a large urban area of more than three miles diameter”) and psychological dimension. As for target cities, the committee agreed that the following should be exempt from Army Air Force bombing so they would be available for nuclear targeting: Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and Kokura Arsenal. Japan’s cultural capital, Kyoto, would not stay on the list. Pressure from Secretary of War Stimson had already taken Kyoto off the list of targets for incendiary bombings and he would successfully object to the atomic bombing of that city. [18]

Document 12 : Stimson Diary Entries, May 14 and 15, 1945

Source: Henry Stimson Diary, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress)

On May 14 and 15, Stimson had several conversations involving S-1 (the atomic bomb); during a talk with Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, he estimated that possession of the bomb gave Washington a tremendous advantage—“held all the cards,” a “royal straight flush”-- in dealing with Moscow on post-war problems: “They can’t get along without our help and industries and we have coming into action a weapon which will be unique.” The next day a discussion of divergences with Moscow over the Far East made Stimson wonder whether the atomic bomb would be ready when Truman met with Stalin in July. If it was, he believed that the bomb would be the “master card” in U.S. diplomacy. This and other entries from the Stimson diary (as well as the entry from the Davies diary that follows) are important to arguments developed by Gar Alperovitz and Barton J. Bernstein, among others, although with significantly different emphases, that in light of controversies with the Soviet Union over Eastern Europe and other areas, top officials in the Truman administration believed that possessing the atomic bomb would provide them with significant leverage for inducing Moscow’s acquiescence in U.S. objectives. [19]

Document 13 : Davies Diary entry for May 21, 1945

Source: Joseph E. Davies Papers, Library of Congress, box 17, 21 May 1945

While officials at the Pentagon continued to look closely at the problem of atomic targets, President Truman, like Stimson, was thinking about the diplomatic implications of the bomb. During a conversation with Joseph E. Davies, a prominent Washington lawyer and former ambassador to the Soviet Union, Truman said that he wanted to delay talks with Stalin and Churchill until July when the first atomic device had been tested. Alperovitz treated this entry as evidence in support of the atomic diplomacy argument, but other historians, ranging from Robert Maddox to Gabriel Kolko, have denied that the timing of the Potsdam conference had anything to do with the goal of using the bomb to intimidate the Soviets. [20]

Document 14 : Letter, O. C. Brewster to President Truman, 24 May 1945, with note from Stimson to Marshall, 30 May 1945, attached, secret

Source: Harrison-Bundy Files relating to the Development of the Atomic Bomb, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1108 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), File 77: "Interim Committee - International Control."

In what Stimson called the “letter of an honest man,” Oswald C. Brewster sent President Truman a profound analysis of the danger and unfeasibility of a U.S. atomic monopoly. [21] An engineer for the Kellex Corporation, which was involved in the gas diffusion project to enrich uranium, Brewster recognized that the objective was fissile material for a weapon. That goal, he feared, raised terrifying prospects with implications for the “inevitable destruction of our present day civilization.” Once the U.S. had used the bomb in combat other great powers would not tolerate a monopoly by any nation and the sole possessor would be “be the most hated and feared nation on earth.” Even the U.S.’s closest allies would want the bomb because “how could they know where our friendship might be five, ten, or twenty years hence.” Nuclear proliferation and arms races would be certain unless the U.S. worked toward international supervision and inspection of nuclear plants.

Brewster suggested that Japan could be used as a “target” for a “demonstration” of the bomb, which he did not further define. His implicit preference, however, was for non-use; he wrote that it would be better to take U.S. casualties in “conquering Japan” than “to bring upon the world the tragedy of unrestrained competitive production of this material.”

Document 15 : Minutes of Third Target Committee Meeting – Washington, May 28, 1945, Top Secret

More updates on training missions, target selection, and conditions required for successful detonation over the target. The target would be a city--either Hiroshima, Kyoto (still on the list), or Niigata--but specific “aiming points” would not be specified at that time nor would industrial “pin point” targets because they were likely to be on the “fringes” a city. The bomb would be dropped in the city’s center. “Pumpkins” referred to bright orange, pumpkin-shaped high explosive bombs—shaped like the “Fat Man” implosion weapon--used for bombing run test missions.

Document 16 : General Lauris Norstad to Commanding General, XXI Bomber Command, “509 th Composite Group; Special Functions,” May 29, 1945, Top Secret

The 509 th Composite Group’s cover story for its secret mission was the preparation of “Pumpkins” for use in battle. In this memorandum, Norstad reviewed the complex requirements for preparing B-29s and their crew for successful nuclear strikes.

Document 17 : Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, “Memorandum of Conversation with General Marshal May 29, 1945 – 11:45 p.m.,” Top Secret

Source: Record Group 107, Office of the Secretary of War, Formerly Top Secret Correspondence of Secretary of War Stimson (“Safe File”), July 1940-September 1945, box 12, S-1

Tacitly dissenting from the Targeting Committee’s recommendations, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall argued for initial nuclear use against a clear-cut military target such as a “large naval installation.” If that did not work, manufacturing areas could be targeted, but only after warning their inhabitants. Marshall noted the “opprobrium which might follow from an ill considered employment of such force.” This document has played a role in arguments developed by Barton J. Bernstein that figures such as Marshall and Stimson were “caught between an older morality that opposed the intentional killing of non-combatants and a newer one that stressed virtually total war.” [22]

Document 18 : “Notes of the Interim Committee Meeting Thursday, 31 May 1945, 10:00 A.M. to 1:15 P.M. – 2:15 P.M. to 4:15 P.M., ” n.d., Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 100 (copy from microfilm)

With Secretary of War Stimson presiding, members of the committee heard reports on a variety of Manhattan Project issues, including the stages of development of the atomic project, problems of secrecy, the possibility of informing the Soviet Union, cooperation with “like-minded” powers, the military impact of the bomb on Japan, and the problem of “undesirable scientists.” Interested in producing the “greatest psychological effect,” the Committee members agreed that the “most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses.” Exactly how the mass deaths of civilians would persuade Japanese rulers to surrender was not discussed. Bernstein has argued that this target choice represented an uneasy endorsement of “terror bombing”--the target was not exclusively military or civilian; nevertheless, worker’s housing would include non-combatant men, women, and children. [23] It is possible that Truman was informed of such discussions and their conclusions, although he clung to a belief that the prospective targets were strictly military.

Document 19 : General George A. Lincoln to General Hull, June 4, 1945, enclosing draft, Top Secret

Source: Record Group 165, Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, American-British-Canadian Top Secret Correspondence, Box 504, “ABC 387 Japan (15 Feb. 45)

George A. Lincoln, chief of the Strategy and Policy Group at U.S. Army’s Operations Department, commented on a memorandum by former President Herbert Hoover that Stimson had passed on for analysis. Hoover proposed a compromise solution with Japan that would allow Tokyo to retain part of its empire in East Asia (including Korea and Japan) as a way to head off Soviet influence in the region. While Lincoln believed that the proposed peace teams were militarily acceptable he doubted that they were workable or that they could check Soviet “expansion” which he saw as an inescapable result of World War II. As to how the war with Japan would end, he saw it as “unpredictable,” but speculated that “it will take Russian entry into the war, combined with a landing, or imminent threat of a landing, on Japan proper by us, to convince them of the hopelessness of their situation.” Lincoln derided Hoover’s casualty estimate of 500,000. J. Samuel Walker has cited this document to make the point that “contrary to revisionist assertions, American policymakers in the summer of 1945 were far from certain that the Soviet invasion of Manchuria would be enough in itself to force a Japanese surrender.” [24]

Document 20 : Memorandum from R. Gordon Arneson, Interim Committee Secretary, to Mr. Harrison, June 6, 1945, Top Secret

In a memorandum to George Harrison, Stimson’s special assistant on Manhattan Project matters, Arneson noted actions taken at the recent Interim Committee meetings, including target criterion and an attack “without prior warning.”

Document 21 : Memorandum of Conference with the President, June 6, 1945, Top Secret

Source: Henry Stimson Papers, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress)

Stimson and Truman began this meeting by discussing how they should handle a conflict with French President DeGaulle over the movement by French forces into Italian territory. (Truman finally cut off military aid to France to compel the French to pull back). [25] As evident from the discussion, Stimson strongly disliked de Gaulle whom he regarded as “psychopathic.” The conversation soon turned to the atomic bomb, with some discussion about plans to inform the Soviets but only after a successful test. Both agreed that the possibility of a nuclear “partnership” with Moscow would depend on “quid pro quos”: “the settlement of the Polish, Rumanian, Yugoslavian, and Manchurian problems.”

At the end, Stimson shared his doubts about targeting cities and killing civilians through area bombing because of its impact on the U.S.’s reputation as well as on the problem of finding targets for the atomic bomb. Barton Bernstein has also pointed to this as additional evidence of the influence on Stimson of an “an older morality.” While concerned about the U.S.’s reputation, Stimson did not want the Air Force to bomb Japanese cities so thoroughly that the “new weapon would not have a fair background to show its strength,” a comment that made Truman laugh. The discussion of “area bombing” may have reminded him that Japanese civilians remained at risk from U.S. bombing operations.

III. Debates on Alternatives to First Use and Unconditional Surrender

Document 22 : Memorandum from Arthur B. Compton to the Secretary of War, enclosing “Memorandum on `Political and Social Problems,’ from Members of the `Metallurgical Laboratory’ of the University of Chicago,” June 12, 1945, Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 76 (copy from microfilm)

Physicists Leo Szilard and James Franck, a Nobel Prize winner, were on the staff of the “Metallurgical Laboratory” at the University of Chicago, a cover for the Manhattan Project program to produce fuel for the bomb. The outspoken Szilard was not involved in operational work on the bomb and General Groves kept him under surveillance but Met Lab director Arthur Compton found Szilard useful to have around. Concerned with the long-run implications of the bomb, Franck chaired a committee, in which Szilard and Eugene Rabinowitch were major contributors, that produced a report rejecting a surprise attack on Japan and recommended instead a demonstration of the bomb on the “desert or a barren island.” Arguing that a nuclear arms race “will be on in earnest not later than the morning after our first demonstration of the existence of nuclear weapons,” the committee saw international control as the alternative. That possibility would be difficult if the United States made first military use of the weapon. Compton raised doubts about the recommendations but urged Stimson to study the report. Martin Sherwin has argued that the Franck committee shared an important assumption with Truman et al.--that an “atomic attack against Japan would `shock’ the Russians”--but drew entirely different conclusions about the import of such a shock. [26]

Document 23 : Memorandum from Acting Secretary of State Joseph Grew to the President, “Analysis of Memorandum Presented by Mr. Hoover,” June 13, 1945

Source: Record Group 107, Office of the Secretary of War, Formerly Top Secret Correspondence of Secretary of War Stimson (“Safe File”), July 1940-September 1945, box 8, Japan (After December 7/41)

A former ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew’s extensive knowledge of Japanese politics and culture informed his stance toward the concept of unconditional surrender. He believed it essential that the United States declare its intention to preserve the institution of the emperor. As he argued in this memorandum to President Truman, “failure on our part to clarify our intentions” on the status of the emperor “will insure prolongation of the war and cost a large number of human lives.” Documents like this have played a role in arguments developed by Alperovitz that Truman and his advisers had alternatives to using the bomb such as modifying unconditional surrender and that anti-Soviet considerations weighed most heavily in their thinking. By contrast, Herbert P. Bix has suggested that the Japanese leadership would “probably not” have surrendered if the Truman administration had spelled out the status of the emperor. [27]

Document 24 : Memorandum from Chief of Staff Marshall to the Secretary of War, 15 June 1945, enclosing “Memorandum of Comments on `Ending the Japanese War,’” prepared by George A. Lincoln, June 14, 1945, Top Secret

Commenting on another memorandum by Herbert Hoover, George A. Lincoln discussed war aims, face-saving proposals for Japan, and the nature of the proposed declaration to the Japanese government, including the problem of defining “unconditional surrender.” Lincoln argued against modifying the concept of unconditional surrender: if it is “phrased so as to invite negotiation” he saw risks of prolonging the war or a “compromise peace.” J. Samuel Walker has observed that those risks help explain why senior officials were unwilling to modify the demand for unconditional surrender. [28]

Document 25 : Memorandum by J. R. Oppenheimer, “Recommendations on the Immediate Use of Nuclear Weapons,” June 16, 1945, Top Secret

In a report to Stimson, Oppenheimer and colleagues on the scientific advisory panel--Arthur Compton, Ernest O. Lawrence, and Enrico Fermi—tacitly disagreed with the report of the “Met Lab” scientists. The panel argued for early military use but not before informing key allies about the atomic project to open a dialogue on “how we can cooperate in making this development contribute to improved international relations.”

Document 26 : “Minutes of Meeting Held at the White House on Monday, 18 June 1945 at 1530,” Top Secret

Source: Record Group 218, Records of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Central Decimal Files, 1942-1945, box 198 334 JCS (2-2-45) Mtg 186 th -194 th

With the devastating battle for Okinawa winding up, Truman and the Joint Chiefs stepped back and considered what it would take to secure Japan’s surrender. The discussion depicted a Japan that, by 1 November, would be close to defeat, with great destruction and economic losses produced by aerial bombing and naval blockade, but not ready to capitulate. Marshall believed that the latter required Soviet entry and an invasion of Kyushu, even suggesting that Soviet entry might be the “decisive action levering them into capitulation.” Truman and the Chiefs reviewed plans to land troops on Kyushu on 1 November, which Marshall believed was essential because air power was not decisive. He believed that casualties would not be more than those produced by the battle for Luzon, some 31,000. This account hints at discussion of the atomic bomb (“certain other matters”), but no documents disclose that part of the meeting.

The record of this meeting has figured in the complex debate over the estimates of casualties stemming from a possible invasion of Japan. While post-war justifications for the bomb suggested that an invasion of Japan could have produced very high levels of casualties (dead, wounded, or missing), from hundreds of thousands to a million, historians have vigorously debated the extent to which the estimates were inflated. [29]

According to accounts based on post-war recollections and interviews, during the meeting McCloy raised the possibility of winding up the war by guaranteeing the preservation of the emperor albeit as a constitutional monarch. If that failed to persuade Tokyo, he proposed that the United States disclose the secret of the atomic bomb to secure Japan’s unconditional surrender. While McCloy later recalled that Truman expressed interest, he said that Secretary of State Byrnes squashed the proposal because of his opposition to any “deals” with Japan. Yet, according to Forrest Pogue’s account, when Truman asked McCloy if he had any comments, the latter opened up a discussion of nuclear weapons use by asking “Why not use the bomb?” [30]

Document 27 : Memorandum from R. Gordon Arneson, Interim Committee Secretary, to Mr. Harrison, June 25, 1945, Top Secret

For Harrison’s convenience, Arneson summarized key decisions made at the 21 June meeting of the Interim Committee, including a recommendation that President Truman use the forthcoming conference of allied leaders to inform Stalin about the atomic project. The Committee also reaffirmed earlier recommendations about the use of the bomb at the “earliest opportunity” against “dual targets.” In addition, Arneson included the Committee’s recommendation for revoking part two of the 1944 Quebec agreement which stipulated that the neither the United States nor Great Britain would use the bomb “against third parties without each other’s consent.” Thus, an impulse for unilateral control of nuclear use decisions predated the first use of the bomb.

Document 28 : Memorandum from George L. Harrison to Secretary of War, June 26, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED, H-B files, folder no. 77 (copy from microfilm)

Reminding Stimson about the objections of some Manhattan project scientists to military use of the bomb, Harrison summarized the basic arguments of the Franck report. One recommendation shared by many of the scientists, whether they supported the report or not, was that the United States inform Stalin of the bomb before it was used. This proposal had been the subject of positive discussion by the Interim Committee on the grounds that Soviet confidence was necessary to make possible post-war cooperation on atomic energy.

Document 29 : Memorandum from George L. Harrison to Secretary of War, June 28, 1945, Top Secret, enclosing Ralph Bard’s “Memorandum on the Use of S-1 Bomb,” June 27, 1945

Under Secretary of the Navy Ralph Bard joined those scientists who sought to avoid military use of the bomb; he proposed a “preliminary warning” so that the United States would retain its position as a “great humanitarian nation.” Alperovitz cites evidence that Bard discussed his proposal with Truman who told him that he had already thoroughly examined the problem of advanced warning. This document has also figured in the argument framed by Barton Bernstein that Truman and his advisers took it for granted that the bomb was a legitimate weapon and that there was no reason to explore alternatives to military use. Bernstein, however, notes that Bard later denied that he had a meeting with Truman and that White House appointment logs support that claim. [31]

Document 30 : Memorandum for Mr. McCloy, “Comments re: Proposed Program for Japan,” June 28, 1945, Draft, Top Secret

Source: RG 107, Office of Assistant Secretary of War Formerly Classified Correspondence of John J. McCloy, 1941-1945, box 38, ASW 387 Japan

Despite the interest of some senior officials such as Joseph Grew, Henry Stimson, and John J. McCloy in modifying the concept of unconditional surrender so that the Japanese could be sure that the emperor would be preserved, it remained a highly contentious subject. For example, one of McCloy’s aides, Colonel Fahey, argued against modification of unconditional surrender (see “Appendix ‘C`”).

Document 31 : Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy to Colonel Stimson, June 29, 1945, Top Secret

McCloy was part of a drafting committee at work on the text of a proclamation to Japan to be signed by heads of state at the forthcoming Potsdam conference. As McCloy observed the most contentious issue was whether the proclamation should include language about the preservation of the emperor: “This may cause repercussions at home but without it those who seem to know the most about Japan feel there would be very little likelihood of acceptance.”

Document 32 : Memorandum, “Timing of Proposed Demand for Japanese Surrender,” June 29, 1945, Top Secret

Probably the work of General George A. Lincoln at Army Operations, this document was prepared a few weeks before the Potsdam conference when senior officials were starting to finalize the text of the declaration that Truman, Churchill, and Chiang would issue there. The author recommended issuing the declaration “just before the bombardment program [against Japan] reaches its peak.” Next to that suggestion, Stimson or someone in his immediate office, wrote “S1”, implying that the atomic bombing of Japanese cities was highly relevant to the timing issue. Also relevant to Japanese thinking about surrender, the author speculated, was the Soviet attack on their forces after a declaration of war.

Document 33 : Stimson memorandum to The President, “Proposed Program for Japan,” 2 July 1945, Top Secret

Source: Naval Aide to the President Files, box 4, Berlin Conference File, Volume XI - Miscellaneous papers: Japan, Harry S. Truman Presidential Library

On 2 July Stimson presented to President Truman a proposal that he had worked up with colleagues in the War Department, including McCloy, Marshall, and Grew. The proposal has been characterized as “the most comprehensive attempt by any American policymaker to leverage diplomacy” in order to shorten the Pacific War. Stimson had in mind a “carefully timed warning” delivered before the invasion of Japan. Some of the key elements of Stimson’s argument were his assumption that “Japan is susceptible to reason” and that Japanese might be even more inclined to surrender if “we do not exclude a constitutional monarchy under her present dynasty.” The possibility of a Soviet attack would be part of the “threat.” As part of the threat message, Stimson alluded to the “inevitability and completeness of the destruction” which Japan could suffer, but he did not make it clear whether unconditional surrender terms should be clarified before using the atomic bomb. Truman read Stimson’s proposal, which he said was “powerful,” but made no commitments to the details, e.g., the position of the emperor. [32]

Document 34 : Minutes, Secretary’s Staff Committee, Saturday Morning, July 7, 1945, 133d Meeting, Top Secret

Source: Record Group 353, Records of Interdepartmental and Intradepartmental Committees, Secretary’s Staff Meetings Minutes, 1944-1947 (copy from microfilm)

The possibility of modifying the concept of unconditional surrender so that it guaranteed the continuation of the emperor remained hotly contested within the U.S. government. Here senior State Department officials, Under Secretary Joseph Grew on one side, and Assistant Secretary Dean Acheson and Archibald MacLeish on the other, engaged in hot debate.

Document 35 : Combined Chiefs of Staff, “Estimate of the Enemy Situation (as of 6 July 1945, C.C.S 643/3, July 8, 1945, Secret (Appendices Not Included)

Source: RG 218, Central Decimal Files, 1943-1945, CCS 381 (6-4-45), Sec. 2 Pt. 5

This review of Japanese capabilities and intentions portrays an economy and society under “tremendous strain”; nevertheless, “the ground component of the Japanese armed forces remains Japan’s greatest military asset.” Alperovitz sees statements in this estimate about the impact of Soviet entry into the war and the possibility of a conditional surrender involving survival of the emperor as an institution as more evidence that the policymakers saw alternatives to nuclear weapons use. By contrast, Richard Frank takes note of the estimate’s depiction of the Japanese army’s terms for peace: “for surrender to be acceptable to the Japanese army it would be necessary for the military leaders to believe that it would not entail discrediting the warrior tradition and that it would permit the ultimate resurgence of a military in Japan.” That, Frank argues, would have been “unacceptable to any Allied policy maker.” [33]

Document 36 : Cable to Secretary of State from Acting Secretary Joseph Grew, July 16, 1945, Top Secret

Source: Record Group 59, Decimal Files 1945-1949, 740.0011 PW (PE)/7-1645

On the eve of the Potsdam Conference, a State Department draft of the proclamation to Japan contained language which modified unconditional surrender by promising to retain the emperor. When former Secretary of State Cordell Hull learned about it he outlined his objections to Byrnes, arguing that it might be better to wait “the climax of allied bombing and Russia’s entry into the war.” Byrnes was already inclined to reject that part of the draft, but Hull’s argument may have reinforced his decision.

Document 37 : Letter from Stimson to Byrnes, enclosing memorandum to the President, “The Conduct of the War with Japan,” 16 July 1945, Top Secret

Source: Henry L. Stimson Papers (MS 465), Sterling Library, Yale University (reel 113) (microfilm at Library of Congress)

Still interested in trying to find ways to “warn Japan into surrender,” this represents an attempt by Stimson before the Potsdam conference, to persuade Truman and Byrnes to agree to issue warnings to Japan prior to the use of the bomb. The warning would draw on the draft State-War proclamation to Japan; presumably, the one criticized by Hull (above) which included language about the emperor . Presumably the clarified warning would be issued prior to the use of the bomb; if the Japanese persisted in fighting then “the full force of our new weapons should be brought to bear” and a “heavier” warning would be issued backed by the “actual entrance of the Russians in the war.” Possibly, as Malloy has argued, Stimson was motivated by concerns about using the bomb against civilians and cities, but his latest proposal would meet resistance at Potsdam from Byrnes and other. [34]

Document 38 : R. E. Lapp, Leo Szilard et al., “A Petition to the President of the United States,” July 17, 1945

On the eve of the Potsdam conference, Leo Szilard circulated a petition as part of a final effort to discourage military use of the bomb. Signed by about 68 Manhattan Project scientists, mainly physicists and biologists (copies with the remaining signatures are in the archival file), the petition did not explicitly reject military use, but raised questions about an arms race that military use could instigate and requested Truman to publicize detailed terms for Japanese surrender. Truman, already on his way to Europe, never saw the petition. [35]

IV. The Japanese Search for Soviet Mediation

Documents 39A-B: Magic

39A : William F. Friedman, Consultant (Armed Forces Security Agency), “A Short History of U.S. COMINT Activities,” 19 February 1952, Top Secret

39B :“Magic” – Diplomatic Summary, War Department, Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1204 – July 12, 1945, Top Secret Ultra

Sources: A: National Security Agency Mandatory declassification review release; B: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security Agency/Central Security Service, “Magic” Diplomatic Summaries 1942-1945, box 18

Beginning in September 1940, U.S. military intelligence began to decrypt routinely, under the “Purple” code-name, the intercepted cable traffic of the Japanese Foreign Ministry. Collectively the decoded messages were known as “Magic.” How this came about is explained in an internal history of pre-war and World War II Army and Navy code-breaking activities prepared by William F. Friedman , a central figure in the development of U.S. government cryptology during the 20 th century. The National Security Agency kept the ‘Magic” diplomatic and military summaries classified for many years and did not release the entire series for 1942 through August 1945 until the early 1990s. [36]

The 12 July 1945 “Magic” summary includes a report on a cable from Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo to Ambassador Naotake Sato in Moscow concerning the Emperor’s decision to seek Soviet help in ending the war. Not knowing that the Soviets had already made a commitment to their Allies to declare war on Japan, Tokyo fruitlessly pursued this option for several weeks. The “Magic” intercepts from mid-July have figured in Gar Alperovitz’s argument that Truman and his advisers recognized that the Emperor was ready to capitulate if the Allies showed more flexibility on the demand for unconditional surrender. This point is central to Alperovitz’s thesis that top U.S. officials recognized a “two-step logic”: relaxing unconditional surrender and a Soviet declaration of war would have been enough to induce Japan’s surrender without the use of the bomb. [37]

Document 40 : John Weckerling, Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, July 12, 1945, to Deputy Chief of Staff, “Japanese Peace Offer,” 13 July 1945, Top Secret Ultra

Source: RG 165, Army Operations OPD Executive File #17, Item 13 (copy courtesy of J. Samuel Walker)

The day after the Togo message was reported, Army intelligence chief Weckerling proposed several possible explanations of the Japanese diplomatic initiative. Robert J. Maddox has cited this document to support his argument that top U.S. officials recognized that Japan was not close to surrender because Japan was trying to “stave off defeat.” In a close analysis of this document, Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, who is also skeptical of claims that the Japanese had decided to surrender, argues that each of the three possibilities proposed by Weckerling “contained an element of truth, but none was entirely correct”. For example, the “governing clique” that supported the peace moves was not trying to “stave off defeat” but was seeking Soviet help to end the war. [38]

Document 41 : “Magic” – Diplomatic Summary, War Department, Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1205 – July 13, 1945, Top Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security Agency/Central Security Service, “Magic” Diplomatic Summaries 1942-1945, box 18

The day after he told Sato about the current thinking on Soviet mediation, Togo requested the Ambassador to see Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and tell him of the Emperor’s “private intention to send Prince Konoye as a Special Envoy” to Moscow. Before he received Togo’s message, Sato had already met with Molotov on another matter.

Document 42 : “Magic” – Diplomatic Summary, War Department, Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1210 – July 17, 1945, Top Secret Ultra

Source: Record Group 457, Records of the National Security Agency/Central Security Service, “Magic” Diplomatic Summaries 1942-1945, box 18.

Another intercept of a cable from Togo to Sato shows that the Foreign Minister rejected unconditional surrender and that the Emperor was not “asking the Russian’s mediation in anything like unconditional surrender.” Incidentally, this “`Magic’ Diplomatic Summary” indicates the broad scope and capabilities of the program; for example, it includes translations of intercepted French messages (see pages 8-9).

Document 43 : Admiral Tagaki Diary Entry for July 20, 1945

Source: Takashi Itoh, ed., Sokichi Takagi: Nikki to Joho [Sokichi Takagi: Diary and Documents] (Tokyo, Japan: Misuzu-Shobo, 2000), 916-917 [Translation by Hikaru Tajima]

In 1944 Navy minister Mitsumasa Yonai ordered rear admiral Sokichi Takagi to go on sick leave so that he could undertake a secret mission to find a way to end the war. Tagaki was soon at the center of a cabal of Japanese defense officials, civil servants, and academics, which concluded that, in the end, the emperor would have to “impose his decision on the military and the government.” Takagi kept a detailed account of his activities, part of which was in diary form, the other part of which he kept on index cards. The material reproduced here gives a sense of the state of play of Foreign Minister Togo’s attempt to secure Soviet mediation. Hasegawa cited it and other documents to make a larger point about the inability of the Japanese government to agree on “concrete” proposals to negotiate an end to the war. [39]

The last item discusses Japanese contacts with representatives of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in Switzerland. The reference to “our contact” may refer to Bank of International Settlements economist Pers Jacobbson who was in touch with Japanese representatives to the Bank as well as Gero von Gävernitz, then on the staff, but with non-official cover, of OSS station chief Allen Dulles. The contacts never went far and Dulles never received encouragement to pursue them. [40]

V. The Trinity Test

Document 44 : Letter from Commissar of State Security First Rank, V. Merkulov, to People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs L. P. Beria, 10 July 1945, Number 4305/m, Top Secret (translation by Anna Melyaskova)

Source: L.D. Riabev, ed., Atomnyi Proekt SSSR (Moscow: izd MFTI, 2002), Volume 1, Part 2, 335-336

This 10 July 1945 letter from NKVD director V. N. Merkulov to Beria is an example of Soviet efforts to collect inside information on the Manhattan Project, although not all the detail was accurate. Merkulov reported that the United States had scheduled the test of a nuclear device for that same day, although the actual test took place 6 days later. According to Merkulov, two fissile materials were being produced: element-49 (plutonium), and U-235; the test device was fueled by plutonium. The Soviet source reported that the weight of the device was 3 tons (which was in the ball park) and forecast an explosive yield of 5 kilotons. That figure was based on underestimates by Manhattan Project scientists: the actual yield of the test device was 20 kilotons.

As indicated by the L.D. Riabev’s notes, it is possible that Beria’s copy of this letter ended up in Stalin’s papers. That the original copy is missing from Beria’s papers suggests that he may have passed it on to Stalin before the latter left for the Potsdam conference. [41]

Document 45 : Telegram War [Department] 33556, from Harrison to Secretary of War, July 17, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File 5e (copy from microfilm)

An elated message from Harrison to Stimson reported the success of the Trinity Test of a plutonium implosion weapon. The light from the explosion could been seen “from here [Washington, D.C.] to “high hold” [Stimson’s estate on Long Island—250 miles away]” and it was so loud that Harrison could have heard the “screams” from Washington, D.C. to “my farm” [in Upperville, VA, 50 miles away] [42]

Document 46 : Memorandum from General L. R. Groves to Secretary of War, “The Test,” July 18, 1945, Top Secret, Excised Copy

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 4 (copy from microfilm)

General Groves prepared for Stimson, then at Potsdam, a detailed account of the Trinity test. [43]

VI. The Potsdam Conference

Document 47 : Truman’s Potsdam Diary

Source: Barton J. Bernstein, “Truman at Potsdam: His Secret Diary,” Foreign Service Journal , July/August 1980, excerpts, used with author’s permission. [44]

Some years after Truman’s death, a hand-written diary that he kept during the Potsdam conference surfaced in his personal papers. For convenience, Barton Bernstein’s rendition is provided here but linked here are the scanned versions of Truman’s handwriting on the National Archives’ website (for 15-30 July).

The diary entries cover July 16, 17, 18, 20, 25, 26, and 30 and include Truman’s thinking about a number of issues and developments, including his reactions to Churchill and Stalin, the atomic bomb and how it should be targeted, the possible impact of the bomb and a Soviet declaration of war on Japan, and his decision to tell Stalin about the bomb. Receptive to pressure from Stimson, Truman recorded his decision to take Japan’s “old capital” (Kyoto) off the atomic bomb target list. Barton Bernstein and Richard Frank, among others, have argued that Truman’s assertion that the atomic targets were “military objectives” suggested that either he did not understand the power of the new weapons or had simply deceived himself about the nature of the targets. Another statement—“Fini Japs when that [Soviet entry] comes about”—has also been the subject of controversy over whether it meant that Truman thought it possible that the war could end without an invasion of Japan. [45]

Document 48 : Stimson Diary entries for July 16 through 25, 1945

Stimson did not always have Truman’s ear, but historians have frequently cited his diary when he was at the Potsdam conference. There Stimson kept track of S-1 developments, including news of the successful first test (see entry for July 16) and the ongoing deployments for nuclear use against Japan. When Truman received a detailed account of the test, Stimson reported that the “President was tremendously pepped up by it” and that “it gave him an entirely new feeling of confidence” (see entry for July 21). Whether this meant that Truman was getting ready for a confrontation with Stalin over Eastern Europe and other matters has also been the subject of debate.

An important question that Stimson discussed with Marshall, at Truman’s request, was whether Soviet entry into the war remained necessary to secure Tokyo’s surrender. Marshall was not sure whether that was so although Stimson privately believed that the atomic bomb would provide enough to force surrender (see entry for July 23). This entry has been cited by all sides of the controversy over whether Truman was trying to keep the Soviets out of the war. [46] During the meeting on August 24, discussed above, Stimson gave his reasons for taking Kyoto off the atomic target list: destroying that city would have caused such “bitterness” that it could have become impossible “to reconcile the Japanese to us in that area rather than to the Russians.” Stimson vainly tried to preserve language in the Potsdam Declaration designed to assure the Japanese about “the continuance of their dynasty” but received Truman’s assurance that such a consideration could be conveyed later through diplomatic channels (see entry for July 24). Hasegawa argues that Truman realized that the Japanese would refuse a demand for unconditional surrender without a proviso on a constitutional monarchy and that “he needed Japan’s refusal to justify the use of the atomic bomb.” [47]

Document 49 : Walter Brown Diaries, July 10-August 3, 1945

Source: Clemson University Libraries, Special Collections, Clemson, SC; Mss 243, Walter J. Brown Papers, box 10, folder 12, Byrnes, James F.: Potsdam, Minutes, July-August 1945

Walter Brown, who served as special assistant to Secretary of State Byrnes, kept a diary which provided considerable detail on the Potsdam conference and the growing concerns about Soviet policy among top U.S. officials. This document is a typed-up version of the hand-written original (which Brown’s family has provided to Clemson University). That there may be a difference between the two sources becomes evident from some of the entries; for example, in the entry for July 18, 1945 Brown wrote: "Although I knew about the atomic bomb when I wrote these notes, I dared not place it in writing in my book.”

The degree to which the typed-up version reflects the original is worth investigating. In any event, historians have used information from the diary to support various interpretations. For example, Bernstein cites the entries for 20 and 24 July to argue that “American leaders did not view Soviet entry as a substitute for the bomb” but that the latter “would be so powerful, and the Soviet presence in Manchuria so militarily significant, that there was no need for actual Soviet intervention in the war.” For Brown's diary entry of 3 August 9 1945 historians have developed conflicting interpretations (See discussion of document 57). [48]

Document 50 : “Magic” – Diplomatic Summary, War Department, Office of Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, No. 1214 – July 22, 1945, Top Secret Ultra