- Open access

- Published: 05 February 2022

Work environment risk factors causing day-to-day stress in occupational settings: a systematic review

- Junoš Lukan 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Larissa Bolliger 3 na1 ,

- Nele S. Pauwels 4 , 5 ,

- Mitja Luštrek 1 , 2 ,

- Dirk De Bacquer 3 &

- Els Clays 3

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 240 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

17 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

While chronic workplace stress is known to be associated with health-related outcomes like mental and cardiovascular diseases, research about day-to-day occupational stress is limited. This systematic review includes studies assessing stress exposures as work environment risk factors and stress outcomes, measured via self-perceived questionnaires and physiological stress detection. These measures needed to be assessed repeatedly or continuously via Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) or similar methods carried out in real-world work environments, to be included in this review. The objective was to identify work environment risk factors causing day-to-day stress.

The search strategies were applied in seven databases resulting in 11833 records after deduplication, of which 41 studies were included in a qualitative synthesis. Associations were evaluated by correlational analyses.

The most commonly measured work environment risk factor was work intensity, while stress was most often framed as an affective response. Measures from these two dimensions were also most frequently correlated with each other and most of their correlation coefficients were statistically significant, making work intensity a major risk factor for day-to-day workplace stress.

Conclusions

This review reveals a diversity in methodological approaches in data collection and data analysis. More studies combining self-perceived stress exposures and outcomes with physiological measures are warranted.

Peer Review reports

Over the past decades, substantial attention has been directed to research focusing on chronic exposure to stressors in occupational settings and the adverse impact of stress on chronic disease outcomes [ 1 , 2 ]. Psychosocial risk factors have been the last ones to be considered, but are now widely accepted to be as important as other factors like biological or chemical risks [ 3 ]. The influence on mental and cardiovascular health in particular has been confirmed and explained through frameworks at the forefront of stress research, such as the Job Demand-Control-Support model [ 4 – 6 ], the Effort-Reward Imbalance model [ 7 ], and the Job Demands-Resources model [ 8 ].

Evidence of chronic stressors influencing workers’ health and well-being is accumulating, and several systematic reviews and meta-analyses with a focus on studies investigating such relations are available. There is evidence that psychosocial stress is associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [ 1 ], musculoskeletal disorders [ 9 ], mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety [ 2 ], and health risk behaviour, such as cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and overweight [ 10 ]. The most commonly studied workplace risk factors include job demand and job control (such as in the Job Demand-Control-Support model) [ 1 ], but several others have been studied, such as job insecurity, procedural (in)justice, workplace conflict or bullying [ 2 ], and workplace violence [ 11 ]. A lot of these risk factors are structural and as such measured at a single time point. On the other hand, a preliminary literature search revealed little information about how these structural risk factors manifest in daily work life and what the specific (if any) work environment risk factors causing day-to-day (i.e., non-chronic) stress are.

Understanding how day-to-day work situations lead to the experience of stress is important for several reasons. Stress measurement often relies on self-reports, which are subject to memory bias [ 12 ] and there are indications that chronic assessments are not simply the sum of multiple moment-to-moment ratings [ 13 ]. When stress is measured several times a day, these repeated measurements can instead capture stressful situations during or soon after they occur and the risk of memory bias is reduced. This relationship would also be important to understand since, in order to test hypotheses about how particular stressors lead to health outcomes, temporal relationships need to be explored [ 14 , 15 ]. Finally, the question of how to design stress management interventions is still open [ 16 ]. Broad constructs such as work demands and decision latitude are relatively stable aspects of a job and translating the findings from chronic stress research into stress management strategies applicable in every-day working life would require a better understanding of their day-to-day manifestations. To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review with a focus on day-to-day stress and related work environment risk factors has been performed so far.

We were interested in how various situations at work translate to an experience of stress and which situations are the most important for this experience. We named this relationship ‘day-to-day stress’, which differs from chronic stress in that it can entail daily situations in addition to structural characteristics of the workplace. Day-to-day stressors do not necessarily have long-lasting consequences but do influence the perception of work environment and elicit some kind of response from a person. We do not presume any conceptual difference between day-to-day stress and chronic stress or stressors, but rather differentiate them based on the methodology of stress measurement. As such, we did not restrain our selection of studies to review to any particular definition of (day-to-day or chronic) stress. To understand how exposures to work environment risk factors are related to daily variations of stress, we instead focused on the studies that measure these repeatedly with self-reports or continuously using physiological measurements and in real-world occupational settings.

The objective of this systematic review was to explore the onset of day-to-day stress by summarising evidence on potential day-to-day work environment risk factors (stressors), which have an immediate effect on self-perceived stress levels or physiological stress responses, and which may or may not cause chronic stress.

Materials and methods

We conducted this systematic review by following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews [ 17 ] and the PRISMA 2009 Checklist [ 18 ] and registered it on PROSPERO under the ID: CRD42018105355 [ 19 ].

Eligibility criteria

We first settled on working definitions of the concepts of interest. Throughout this systematic review, we use the term work environment risk factors for stressors, which we defined more specifically as causes or predictors of stress, potentially occurring on a day-to-day basis within occupational settings . Furthermore, we defined self-perceived stress outcomes as consequences of such work environment risk factors which were measured with self-perception-based scales, questionnaires, or surveys .

As the main eligibility criterion, the studies needed to include work environment risk factors and either self-perceived stress outcomes or physiological stress detection or both. We looked for any (objective) descriptions of work situations and their consequences in terms of stress. We did not constrain the outcomes to any particular definition of stress as long as the authors of the original studies framed them as somehow related to the phenomenon of psychosocial stress.

Both, risk factors and outcomes, were required to be measured repeatedly, so methods capable of producing repeated or continuous measurements had to be used. One such method is Ecological Momentary Assessment [ 20, EMA ], which is a research method allowing participants to report their experiences in real-time and in real-world settings, in which data are collected repeatedly (i.e., more than two measurement points) over time and often through a digital platform such as a smartphone application [ 21 ]. Moreover, the phenomenon of interest was day-to-day stress, so studies focusing on chronic stress only were not considered.

We focused on studies set in a real-world working environment, and either the workplace setting or the occupational profile needed to be extractable. Healthy full-time and part-time workers of working age were chosen as the population of interest. Observational quantitative and mixed-methods studies (where only the quantitative part of the latter was of relevance) including at least two measurement points were included.

Strategies for database searching

We devised a search strategy according to the eligibility criteria described in the previous subsection. The main blocks of the search strategy require that 1) a study deals with stress (or synonymous concepts), which should furthermore be 2) day-to-day or episodic (or similar). We also set 3) the requirements for methods, which could be either ecological momentary assessments or other methods capable of producing repeated measures, and 4) that the setting of interest is the work setting. The full search strategies with indexing terms and free text words for all the databases can be found in Supplementary Figs. 1 to 7 [see Additional file 3 ].

We evaluated the search strategy with the PRESS checklist [ 22 ] before we applied it in the following databases: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, CINAHL, ERIC, and PsycArticles. We first carried out a search on 31 August 2018 and later did an update of the initial search on 3 July 2020. The only limitation we used at the time of the searches was “English language”.

Study selection process

The studies were selected based on the process described in the PRISMA statement [ 18 ]. After merging all the results and manually deduplicating them, we screened the titles and abstracts, and evaluated the full text of the remaining articles for eligibility.

Both title and abstract screening and full-text evaluation were done independently by two authors using the Rayyan software [ 23 ]. Conflicts after both screening phases were discussed until consensus was reached. We followed the same procedure when we updated our search.

Quality assessment strategy

The quality assessment in systematic reviews includes two phases: 1) evaluation of the quality at study level (each study separately) and 2) evaluation of the body of evidence (all included studies together) to give a thorough quality estimate of the evidence at hand.

For the quality assessment at study level, we used the QualSyst tool for quantitative research [ 24 ]. This tool offers ‘N/A’ grades for criteria that are inapplicable. Out of the 14 criteria in the tool, we omitted three—random allocation to treatment group (1) and blinding of investigators (2) and subjects (3)—since they are only applicable to intervention studies.

Consequently, each study was assessed according to 11 criteria (e.g., question or objective sufficiently described) on a three point scale. From these, the summary score is calculated, which is a number between 0 and 1, where 1 denotes complete satisfaction of all applicable criteria. This procedure was done independently by two authors and any conflicts were discussed until consensus was reached.

The quality assessment of the body of evidence was evaluated using the GRADE approach [ 25 ], including five criteria for downgrading (risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias) and two criteria for upgrading (large magnitude of effect and dose-response gradient) before an overall score was given.

Study selection

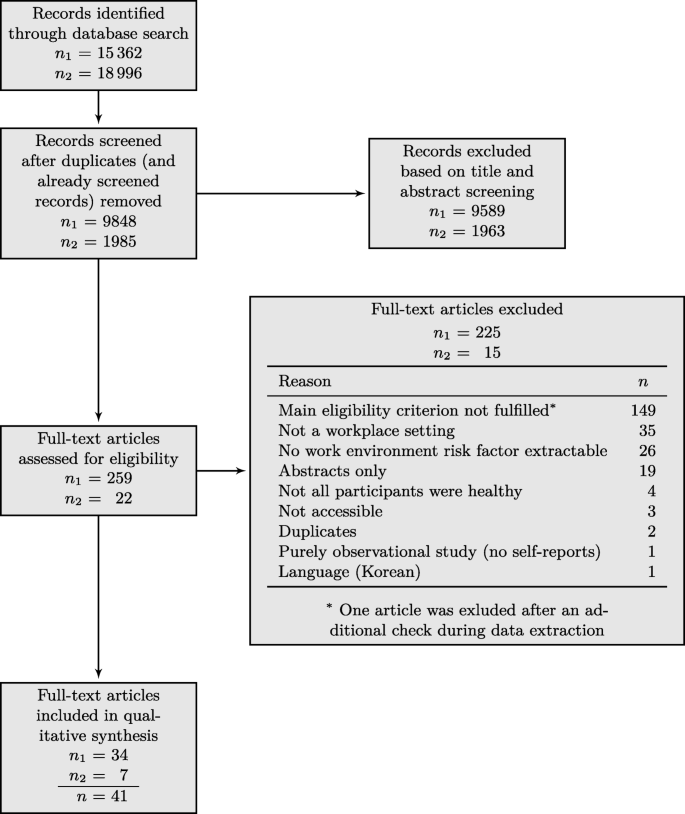

We applied the search strategy as discussed in Strategies for database searching and retrieved 15362 records. We removed duplicates first and then eliminated irrelevant studies by first screening their titles and abstracts and then considering the full text of a selected subset.

We followed the same procedure for the second search, in which we retrieved 18996 records. We excluded all the records already found in the first search as well as some duplicates from different databases, then repeated the same screening procedure. The whole process is illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Study selection presented with the PRISMA flow diagram [ 18 ]. The n 1 and n 2 refer to the first search we performed on 31 August 2018 and to the update search from 3 July 2020, respectively. Their sum is reported as n

As per recommendations in Moher et al. [ 18 ], we noted the exclusion reasons for all the publications we reviewed in full. 149 studies were excluded based on the main eligibility criterion: either the work environment risk factors or stress outcomes were missing, or they were not measured repeatedly. In 35 cases, neither the workplace setting nor the occupational profile was mentioned. In 26 cases, no work environment risk factor could be extracted. 19 publications turned out to be abstracts only. Four further studies were excluded because not all participants were described as healthy. Three studies were not accessible: two PhD theses [ 26 , 27 ], of which authors were contacted, but we got no response, and a report [ 28 ], the author of which is deceased. Two additional duplicates were found, one study only included observational methods (i.e., no self-reports), and one study was available in Korean only.

After this, we were left with 41 studies (34 from the first and 7 from the second search), which were included in the final review for a qualitative synthesis.

Study characteristics

Table 1 lists all the studies included in the final review and gives their most important characteristics. In addition to the number of subjects included ( N ) and the work setting of the study, it includes the study duration and assessment frequency. Added are the quality rating of the study and information about whether data analysis included multilevel analysis.

The studies included from N =14 to N =304 participants, with the median N median =83. The study duration also varied, usually together with the assessment frequency. Thus, some studies only looked at one day, but measured some parameters continuously (e.g., blood pressure in study ID 32), whereas others only sampled once a day for 60 days (study ID 26) or even once a week, but lasted for 182 days (study ID 37).

The average quality of the studies according to QualSyst was M QualSyst =0.86. Specifically, 10 out of the 41 studies were rated at the highest quality level, 28 studies were rated between 0.99 and 0.51, and 3 studies were rated as 0.50 or below. Points were most often deducted because recruitment methods were not clearly reported (‘Method of subject selection’ criterion) or when the authors only reported significance of the main results, but no estimate of variance, such as confidence intervals or standard errors (‘Some estimate of variance’ criterion).

The GRADE approach rates randomised trials as ‘high quality’, observational studies as ‘low quality’, and any other evidence as ‘very low quality’. Since all included studies of this review are observational studies, the quality of the body of evidence was consequently rated as low. Additionally, according to the criteria for downgrading or upgrading mentioned in Quality assessment strategy, no downgrading was required and no upgrading was feasible for our body of evidence, so ‘low’ was also the final score.

Work environment risk factors, self-perceived stress outcomes, and physiological measurements

We identified work environment risk factors, self-perceived stress outcomes, and physiological measurements measured in each study. We extracted all constructs that were measured more than twice (i.e., repeatedly or continuously), while one-time measurements (e.g., during initial baseline screening) were not considered. Since concepts like stress are defined in different ways across the studies, we also looked at the measurement instruments. The work environment risk factors and stress outcomes extracted in this way are published as Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 [see Additional file 1 ].

We classified these into broader categories, which were based on established frameworks. For work environment risk factors, we used the 6th European Working Conditions Survey classification of job quality indices [ 29 ] as the basis. These are objective features of a job which have been proven to have an impact on the health and well-being of workers. They are also only weakly correlated, so that they function as independent descriptions of job quality. Hence, these served well to get a higher level overview of work environment risk factors.

Similarly, stress outcomes were classified according to the stress model described by Ice and James [ 30 ]. They describe stress as a combination of affective, behavioural, and physiological responses, which impact mental health and can have physical health outcomes. These responses are consequences of a person’s appraisal of stressors (stimuli). While classifying the studies in our review, we also identified the need for two additional consequences of stress. First, stress can also affect a person’s cognition, not only at the stage of appraisal, but as its consequence; forgetting of intentions and cognitive failure are examples of this outcome. Second, we determined motivational responses, specifically work engagement, to be sufficiently distinct from affective responses to deserve its own category. This outcome involves not only emotions, but goal-directed behaviour closely related to affective responses.

The frequencies of different measures of work environment risk factors and stress outcomes are summarised in Table 2 . The risk factor most often measured in the included studies was work intensity, defined for example as time pressure or job demand. This was followed by social environment risk factors (such as co-worker and supervisor support) and ‘various’ factors (such as the number or type of stressful situations). On the other end, affective responses were by far the most often measured outcomes, especially as assessed by the Positive and Negative Affect Scale [ 31, PANAS ]. Some studies looked at physiological responses to stress as well, while other outcomes were rarely considered.

It is important to note that while all studies included at least one work environment risk factor and one stress outcome as a consequence of the design of our eligibility criteria, each study could measure more than one risk factor or outcome. This means that the total number of measurements is larger than the number of included studies.

Correlation coefficients

The variables of work environment risk factors, self-perceived stress outcomes, and physiological measurements were considered in the relation structure widely known as ‘exposure/predictor–outcome’ or ‘independent variable–dependent variable’.

As shown in Table 1 , 28 studies analysed their data by using multilevel models, while others resorted to other analyses, such as t -tests, correlational tables, and descriptive analysis. Since multilevel models control for dependencies between predictors (usually work environment risk factors) they give a more complete insight into relationships between all modelled variables. But for these studies direct comparison of coefficient estimates would not be appropriate since the models’ structure varied from study to study.

To produce a meaningful comparison, we therefore decided to focus on correlation coefficients in our synthesis. As these were available in the 28 studies as well as some others, they enabled us to compare more directly the results of more studies. It needs to be noted, however, that only bivariate relationships are reflected in these analyses, while more complex relationships between variables are omitted.

Accordingly, correlation coefficients between work environment risk factors (exposures) and self-perceived stress outcomes (outcomes), and work environment risk factors (exposures) and physiological measurements (outcomes) are available in Supplementary Table B [see Additional file 2 ].

For studies that did multilevel analysis, both within-person level and between-persons level results were extracted. But for other studies only a part of the results of interest were extractable. For example, only the results of between-persons level were reported in the study ID 37 or correlation coefficients were not reported for all variables included in the study ID 33 (e.g., no correlation coefficients between nursing tasks and heart rate).

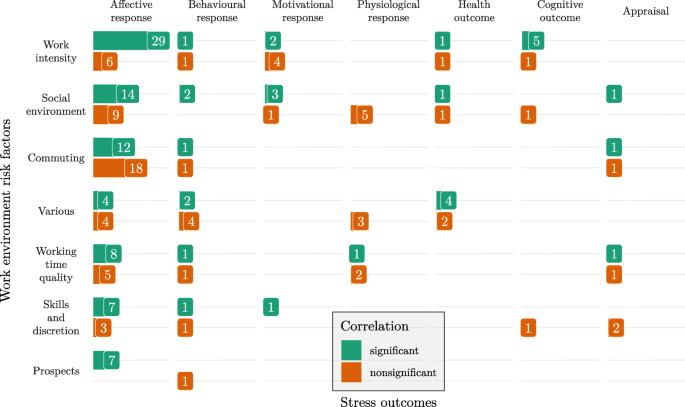

Figure 2 shows the number of statistically significant and nonsignificant correlation coefficients for each pair of work environment risk factor and stress outcome. In this figure, we focused on within-subject correlations only as these were the ones that can capture day-to-day variation of stressors and responses.

The frequency of significant and nonsignificant correlation coefficients between categories of work environment risk factors and stress outcomes

As mentioned in Work environment risk factors, self-perceived stress outcomes, and physiological measurements (see Table 2 ), the most commonly measured risk factor and outcome were work intensity and affective response, respectively. Correspondingly, their relationship in the form of correlation was also the most commonly reported one. Note that the number of correlation coefficients does not directly follow from the number of studies studying a certain relationship, since Table 2 shows measures of all studies, regardless of whether they did multilevel analysis and whether within-subject correlations could be extracted. Additionally, a study looking at several measures of work environment risk factors or stress outcomes could report a correlation within each pair, so that the number of correlations can be even higher than the number of different measures.

Furthermore, most of the correlations between work intensity and affective response were statistically significant. Affective response was also commonly correlated with social environment and this relationship was more often statistically significant than not.

On the other hand commuting from and to the workplace was not significantly correlated with affective responses most of the time. Interestingly, the second most common type of outcomes, physiological responses, were mostly not significantly correlated with any of the risk factors.

In general, the correlations reported in the included studies were more often significant than not (110 significant vs. 80 nonsignificant correlations), but they were typically low. Only two of all the within-subject correlations exceeded 0.5 in their absolute magnitude.

Among the studies that included within-subject correlation coefficients in their results, the most commonly measured work environment risk factor was work intensity, and it was correlated most often with affective response. The high frequency can be to some extent explained by our search strategy. Both stress and demand were included as search terms and we categorised stress(fulness) as an affective response and work demand as work intensity. But since definitions of stress are diverse and often include concepts such as negative affect, our review captured many other stress responses as well as work environment risk factors (stressors).

Work intensity is often measured in epidemiological studies about health consequences of chronic stress, such as coronary heart disease [ 32 ] and depression [ 33 ]. This is reflected in the high number of studies that included it as the stressor of interest. However, since work intensity is most often paired with the control dimension to describe job strain, such as in the Job Demand-Control-Support model, the relative rarity of correlations between skills and discretion and stress outcomes is surprising. It seems that the control dimension of this model is relatively less well researched. However, it is still unclear whether demands and control are related to stress and its health consequences independently, or whether their interaction in the form of job strain is more important [ 34 ]. To settle this question, it would be crucial to explore the role of the control dimension more carefully.

The social environment (e.g., co-worker and supervisor support) has also been correlated with affective and other responses in the included studies. This should be beneficial for gathering more evidence for the relationship of the support dimension with health outcomes, for which only limited evidence has been available in existing reviews [ 33 ]. A similar statement could be made for the prospects category, which has found its place in the Effort-Reward Imbalance model [ 7 ].

Another surprising result was that physiological responses were generally not statistically significantly correlated with any of the work environment risk factors, despite the fact that stress is often predicted from physiological parameters [ 35 ]. This can be explained either with the studies’ analyses choices or complexity of their models. Some of the studies that measured physiological responses did not perform multilevel analysis, but simpler statistical analyses such as t -tests and analysis of variance (studies ID 17, 31, and 32). Others did perform regression analysis or multilevel analysis, but did not report within-subject correlation coefficients for physiological parameters (studies ID 14, 33, and 38). Only three studies reported within-subject correlation coefficients and were included in Fig. 2 , but the relationships between work environment risk factors were usually too complex to be captured by these simple coefficients. For example, co-worker support mediated the daily trajectory of some parameters of heart rate variability [ 36, study ID 8 ] and the relationship between work-to-family conflict and cortisol slope from dinner to bedtime was mediated by supervisor support [ 37, study ID 34 ].

This relative rarity of studies dealing with physiological aspects of stress compared to the field of chronic stress research can be put into a broader context with the help of the conceptual framework proposed by Martikainen et al. [ 38 ] and adapted by Rugulies [ 39 ]. This framework describes the connection between different levels of work environment and health outcomes. It starts with the broadest, (i) macro-level, economic, social, and political structures, and continues through (ii) meso-level workplace structures, (iii) meso-level psychosocial working conditions, to (iv) individual-level experience and cognitive and emotional processes. The latter elicit either (v) psycho-physiological changes or (vi) health-related behaviours, which in turn impact (vii) workers’ health and illness.

It is well established that meso-level workplace structures (ii), such as job insecurity [ 40 ], and meso-level psychosocial working conditions (iii), such as job strain [ 41 ], are related to the risk of diseases and disorders (vii). This has been observed both in immediate physiological responses to stress as well as sustained physiological and behaviour changes. For example, longer duration of work-related stress results in increased rise in morning cortisol level and reduced heart rate variability, and acute stress response involves elevated blood pressure [ 42 ]. On the other hand, job strain has been found to be linked to hypertension, atherosclerosis, and smoking intensity [ 43 ].

Some of the mechanisms of how this happens are also understood. First, pathophysiological effects of stress (v) have been detailed [ 44 ], such as neuroendocrine mechanisms of elevated cortisol and catecholamine (epinephrine) levels as well as inhibited anabolism. Second, stress is related to altered behaviour (vi), such as smoking and alcohol consumption [ 10 ], where this is seen as a second ‘indirect’ pathway of the link between stress and stress-related diseases.

A causal relationship between stress and cardiovascular diseases has still not been established, however, and the pathological mechanisms of chronic and acute stress may differ [ 41 ]. This evidence gap might be owed to a poor understanding of how psychological processes (iv) are involved in this pathway. Steptoe and Kivimäki [ 41 ] explicitly limit the focus of their review to ‘exposure to external stressors, rather than on psychological and biological factors affecting vulnerability to adversity’ (p. 360). And while they mention that ‘one reason for the weak relationship between physiological stress responses and future disease is that mental stress testing measures a propensity to high- or low-stress responsivity’ [ 42, p. 341 ], they only admit this role to biological stress reactivity.

But it might be precisely the psychosocial factors, which Martikainen et al. [ 38 ] see as ‘mediating the effects of social structural factors on individual health outcomes’ (p. 1091), that is, the pathway from (ii) and (iii) through (iv) to (vii), where the key to better understanding this causal relationship lies. It might be through perceptions and psychological processes at the individual level that these macro- and meso-level social processes lead to direct psychobiological processes or modified health-related behaviours and lifestyles and, in turn, influence health [ 38 ].

Some of the studies included in our review deal with the relationships in this pathway and more systematic research is needed. This also has implications for planning interventions better, since effects of stress and depression management techniques on cardiac outcomes are still uncertain [ 41 ]. While it is clear that occupational stress increases risk for coronary heart disease [ 45 ], more research is needed on how to lower this risk. For example, it is possible to modify work schedule to ameliorate exposure to job strain, but only a randomized clinical trial which would test this intervention could truly assess its effect [ 43 ].

Strengths and limitations

As illustrated, different methods of data collection (e.g., time span, number of measurement points) and a wide range of data analysis approaches (e.g., descriptive results, multilevel analysis) were used across the included studies. This heterogeneity led to a challenging data synthesis and study comparison, and restricted us to a qualitative (narrative) synthesis, rather than a quantitative synthesis in the form of a meta-analysis.

To enable a meaningful comparison of the studies’ results, we needed to introduce a rigorous approach to summarising them. First, we developed a working definition of the concepts explored in our research question. Despite widely acknowledged psychosocial stress models [ 4 , 46 ], definitions of psychosocial stress and job stressors are not used consistently in the literature. This diversity in terminology of ‘stressor’ and ‘stress’ was apparent during several steps, such as during the construction of the search strategies and during data extraction. By framing these phenomena—for the purpose of this systematic review—as ‘work environment risk factors’ and ‘self-perceived stress outcomes’, we attempted to harmonize these differences in terminology. To be able to study relationships between stressors and stress, we classified measured variables into one of these two categories according to our working definitions (see Background). This allowed us to compare different studies’ results.

As mentioned, we disregarded the original studies’ framing of independent and dependent variables and instead classified them according to our own criteria. While this enabled us to look at the studies from the point of view of our study question, it introduced the risk of misrepresenting the original findings.

This concern was alleviated by limiting our data extraction of study results to correlation coefficients, which helped us increase study comparability at the same time. The advantage of considering only correlational analyses is that the Pearson correlation coefficient is a symmetric statistic. This allowed us to sidestep the original authors’ hypotheses and models and frame their (partial) results in our work environment risk factors and stress outcomes research question. This had the effect of including studies from different fields and getting an overview of these relationships, which was as broad as possible.

On the other hand, considering only correlational analysis led to an incomplete representation of results of several included studies. This is especially true of the studies performing more extensive analyses, since correlational analysis was merely an intermediate step before final conclusions based on multilevel analysis or analyses focusing on moderating or mediating effects. This has already been illustrated with the case of physiological responses. With such a diverse set of predictors and outcomes, however, comparing the results of these more complex models proved to be problematic, since it is impossible to compare specific effects without considering the full model.

Another consideration is the focus on statistical significance of correlations. While a fixation on statistical significance has been widely criticised [ 47 ], it served as a good first step in comparisons of heterogeneous studies. Effect size examination made little sense as all the reported within-subject correlation coefficients were low (i.e., r <0.5). Noting the above points about simplification with regard to results reporting, the raw number of statistically significant and nonsignificant correlations should still serve as a first overview of the field.

While the field of chronic stress in the workplace is very well established, how daily work situations translate to day-to-day experience of stress and later to chronic conditions seems to be less understood.

We identified several high-quality studies dealing with this topic. The models they employ and the analytical methods they use are well developed. However, their research questions are particular and usually involve a somewhat narrow definition of stress. Instead of approaching stress outcomes as manifestations of a multifaceted response, only some types of responses are considered, most often affective responses. In our review, none of the studies approached this topic from a full-fledged stress model that would incorporate all the relevant aspects of the response to stressors.

Such a study would first require a combination of various data collection methods, such as ecological momentary assessment and continuous physiological monitoring. It would also call for a more complex analysis approach, such as combining multilevel modelling with structural equation modelling or other probabilistic graphical models. Finally, it would need to deal with the problem in the context of a well-established model of stress that lends itself well to such modelling.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional Files. Additional evaluations done by two reviewers independently are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Ecological momentary assessment

Positive affect negative affect scale

Fishta A, Backé E-M. Psychosocial stress at work and cardiovascular diseases: An overview of systematic reviews. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015; 88(8):997–1014. doi:10.1007/s00420-015-1019-0.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harvey SB, Modini M, Joyce S, Milligan-Saville JS, Tan L, Mykletun A, Bryant RA, Christensen H, Mitchell PB. Can work make you mentally ill? a systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup Environ Med. 2017; 74(4):301–10. doi:10.1136/oemed-2016-104015.

Article Google Scholar

Magnavita N, Chirico F. New and emerging risk factors in occupational health. Appl Sci. 2020; 10(24):8906. doi:10.3390/app10248906.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Johnson JV, Hall EM. Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am J Public Health. 1988; 78(10):1336–42. doi:10.2105/ajph.78.10.1336.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Johnson JV, Hall EM, Theorell T. Combined effects of job strain and social isolation on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in a random sample of the Swedish male working population. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1989; 15(4):271–79. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1852.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity and the Reconstruction of Working Life. New York: Basic books; 1990.

Google Scholar

Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996; 1(1):27–41. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.27.

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001; 86(3):499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499.

Hauke A, Flintrop J, Brun E, Rugulies R. The impact of work-related psychosocial stressors on the onset of musculoskeletal disorders in specific body regions: A review and meta-analysis of 54 longitudinal studies. Work Stress. 2011; 25(3):243–56. doi:10.1080/02678373.2011.614069.

Siegrist J, Rödel A. Work stress and health risk behavior. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006; 32(6):473–81. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1052.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Magnavita N, Stasio ED, Capitanelli I, Lops EA, Chirico F, Garbarino S. Sleep problems and workplace violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurosci. 2019; 13(997):1–18. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00997.

Sato H, Kawahara J-i. Selective bias in retrospective self-reports of negative mood states. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2011; 24(4):359–67. doi:10.1080/10615806.2010.543132.

Bell C, Johnston D, Allan J, Johnston M, Pollard B. Repeated real time measures of work stress in nurses may not relate to questionnaire accounts. Psychol Health. 2013; 28(sup1 (EHPS 2013 Abstracts)):65–66. doi:10.1080/08870446.2013.810851.

Shiffman S, Stone AA. Introduction to the special section: Ecological momentary assessment in health psychology. Health Psychol. 1998; 17(1):3–5. doi:10.1037/h0092706.

Smyth JM, Stone AA. Ecological momentary assessment research in behavioral medicine. J Happiness Stud. 2003; 4(1):35–52. doi:10.1023/a:1023657221954.

Hurrell JJ. Organizational stress intervention In: Barling J., Kelloway E. K., Frone M. R., editors. Handbook of Work Stress. SAGE Publications, Inc.: 2005. p. 623–46. Chap. 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412975995.n27 .

Cochrane. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 6.1 edn.: Cochrane; 2020.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 6(7):1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Bolliger L, Lukan J, Pauwels NS, Luštrek M, De Bacquer D, Clays E. Work environment risk factors causing day-to-day stress in occupational settings: A systematic review. PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018105355. 2018. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018105355 .

Csikszentmihalyi M, Larson R, Prescott S. The ecology of adolescent activity and experience. J Youth Adolesc. 1977; 6(3):281–94. doi:10.1007/bf02138940.

Gibbons CJ. Turning the page on pen-and-paper questionnaires: Combining ecological momentary assessment and computer adaptive testing to transform psychological assessment in the 21st century. Front Psychol. 2017; 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01933.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS – Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Explanation and Elaboration (PRESS E&E). Ottawa: Elsevier BV; 2016.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016; 5(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

Kmet L, Lee R, Cook L. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. Edmonton, Alta: Institute of Health Economics; 2004.

Schünemann H, BroŻek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A. Handbook for Grading the Quality of Evidence and the Strength of Recommendations Using the GRADE Approach. London: Cochrane; 2013. Cochrane. Retrieved from https://training.cochrane.org/resource/grade-handbook .

Heeren JK. Stress, hardiness, and burnout among psychiatric nurses working in hospital settings. Phd thesis: University of Virginia; 1991.

Northrop LME. Stress, social support, and burnout in nursing home staff. Phd thesis: West Virginia University; 1996.

Johnstone M. Time and tasks: Teacher workload and stress. Research Report ED368700. 1993. Spotlights 44.

Eurofound. Sixth European Working Conditions Survey – Overview Report (2017 Update). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2017. doi:10.2806/422172.

Ice GH, James GD. Conducting a field study of stress In: Ice G. H., James G. D., editors. Measuring Stress in Humans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 2006. p. 3–24. Chap. 1.

Chapter Google Scholar

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988; 54(6):1063–70. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Pejtersen JH, Burr H, Hannerz H, Fishta A, Eller NH. Update on work-related psychosocial factors and the development of ischemic heart disease. Cardiol Rev. 2015; 23(2):94–98. doi:10.1097/crd.0000000000000033.

Theorell T, Hammarström A, Aronsson G, Bendz LT, Grape T, Hogstedt C, Marteinsdottir I, Skoog I, Hall C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2015; 15(738). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4.

Burr H, Formazin M, Pohrt A. Methodological and conceptual issues regarding occupational psychosocial coronary heart disease epidemiology. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016; 42(3):251–55. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3557.

PubMed Google Scholar

Alberdi A, Aztiria A, Basarab A. Towards an automatic early stress recognition system for office environments based on multimodal measurements. J Biomed Inform. 2016; 59:49–75. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2015.11.007.

Baethge A, Vahle-Hinz T, Rigotti T. Coworker support and its relationship to allostasis during a workday: A diary study on trajectories of heart rate variability during work. J Appl Psychol. 2020; 105(5):506–26. doi:10.1037/apl0000445.

Almeida DM, Davis KD, Lee S, Lawson KM, Walter KN, Moen P. Supervisor support buffers daily psychological and physiological reactivity to work-to-family conflict. J Marriage Fam. 2016; 78(1):165–79. doi:10.1111/jomf.12252.

Martikainen P, Bartley M, Lahelma E. Psychosocial determinants of health in social epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2002; 31(6):1091–93. doi:10.1093/ije/31.6.1091.

Rugulies R. What is a psychosocial work environment?. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2019; 45(1):1–6. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3792.

Kim TJ, von dem Knesebeck O. Is an insecure job better for health than having no job at all? a systematic review of studies investigating the health-related risks of both job insecurity and unemployment. BMC Public Health. 2015; 15(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2313-1.

Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012; 9(6):360–70. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45.

Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease: An update on current knowledge. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013; 34(1):337–54. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114452.

Belkic K, Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Baker D. Is job strain a major source of cardiovascular disease risk?Scand J Work Environ Health. 2004; 30(2):85–128. doi:10.5271/sjweh.769.

Kivimäki M, Steptoe A. Effects of stress on the development and progression of cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018; 15(4):215–29. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2017.189.

Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, Kouvonen A, Väänänen A, Vahtera J. Work stress in the etiology of coronary heart disease—a meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006; 32(6):431–42. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1049.

Siegrist J, Li J. Associations of extrinsic and intrinsic components of work stress with health: A systematic review of evidence on the effort-reward imbalance model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016; 13(4):432. doi:10.3390/ijerph13040432.

Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA statement on p-values: Context, process, and purpose. Amer Statist. 2016; 70(2):129–33. doi:10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108.

Louch G, O’Hara J, Gardner P, O’Connor DB. A daily diary approach to the examination of chronic stress, daily hassles and safety perceptions in hospital nursing. Int J Behav Med. 2017; 24(6):946–56. doi:10.1007/s12529-017-9655-2.

Beckers DGJ, van Hooff MLM, van der Linden D, Kompier MAJ, Taris TW, Geurts SAE. A diary study to open up the black box of overtime work among university faculty members. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2008; 34(3):213–23. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1226.

Rutledge T, Stucky E, Dollarhide A, Shively M, Jain S, Wolfson T, Weinger MB, Dresselhaus T. A real-time assessment of work stress in physicians and nurses. Health Psychol. 2009; 28(2):194–200. doi:10.1037/a0013145.

Ilies R, Johnson MD, Judge TA, Keeney J. A within-individual study of interpersonal conflict as a work stressor: Dispositional and situational moderators. J Organ Behav. 2011; 32(1):44–64. doi:10.1002/job.677. First published: 22 December 2010.

Yeh Y-JY, Ma T-N, Pan S-Y, Chuang P-J, Jhuang Y-H. Assessing potential effects of daily cross-domain usage of information and communication technologies. J Soc Psychol. 2019; 160(4):465–78. doi:10.1080/00224545.2019.1680943.

Zhou L, Wang M, Chang C-H, Liu S, Zhan Y, Shi J. Commuting stress process and self-regulation at work: Moderating roles of daily task significance, family interference with work, and commuting means efficacy. Pers Psychol. 2017; 70(4):891–922. doi:10.1111/peps.12219.

Buunk BP, Verhoeven K. Companionship and support at work: A microanalysis of the stress-reducing features of social interaction. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 1991; 12(3):243–58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1203_1.

Dudenhöffer S, Dormann C. Customer-related social stressors and service providers’ affective reactions. J Organ Behav. 2012; 34(4):520–39. doi:10.1002/job.1826.

Rodrigues S, Kaiseler M, Queirós C, Basto-Pereira M. Daily stress and coping among emergency response officers: a case study. Int J Emerg Serv. 2017; 6(2):122–33. doi:10.1108/ijes-10-2016-0019.

Beattie L, Griffin B. Day-level fluctuations in stress and engagement in response to workplace incivility: A diary study. Work Stress. 2014:1–19. doi:10.1080/02678373.2014.898712.

Diebig M, Bormann KC, Rowold J. Day-level transformational leadership and followers’ daily level of stress: A moderated mediation model of team cooperation, role conflict, and type of communication. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2017; 26(2):234–49. doi:10.1080/1359432x.2016.1250741.

Webster JR, Adams GA, Maranto CL, Beehr TA. “dirty” workplace politics and well-being. Psychol Women Quart. 2018; 42(3):361–77. doi:10.1177/0361684318769909.

Kamarck TW, Shiffman SM, Smithline L, Goodie JL, Paty JA, Gnys M, Jong JY-K. Effects of task strain, social conflict, and emotional activation on ambulatory cardiovascular activity: Daily life consequences of recurring stress in a multiethnic adult sample. Health Psychol. 1998; 17(1):17–29. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.17.1.17.

Albrecht SL, Anglim J. Employee engagement and emotional exhaustion of fly-in-fly-out workers: A diary study. Aust J Psychol. 2018; 70(1):66–75. doi:10.1111/ajpy.12155.

Breevaart K, Bakker AB, Derks D, van Vuuren TCV. Engagement during demanding workdays: A diary study on energy gained from off-job activities. Int J Stress Manage. 2020; 27(1):45–52. doi:10.1037/str0000127.

Karlsson K, Niemelä P, Jonsson A. Heart rate as a marker of stress in ambulance personnel: A pilot study of the body’s response to the ambulance alarm. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2011; 26(1):21–26. doi:10.1017/s1049023x10000129.

Fernández-Castro J, Martínez-Zaragoza F, Rovira T, Edo S, Solanes-Puchol Á, Martín-del-Río B, García-Sierra R, Benavides-Gil G, Doval E. How does emotional exhaustion influence work stress? relationships between stressor appraisals, hedonic tone, and fatigue in nurses’ daily tasks: A longitudinal cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017; 75:43–50. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.07.002.

Klumb PL, Voelkle MC, Siegler S. How negative social interactions at work seep into the home: A prosocial and an antisocial pathway. J Organ Behav. 2017; 38(5):629–49. doi:10.1002/job.2154.

Pereira D, Semmer NK, Elfering A. Illegitimate tasks and sleep quality: An ambulatory study. Stress Health. 2014; 30(3):209–21. doi:10.1002/smi.2599.

Stucky ER, Dresselhaus TR, Dollarhide A, Shively M, Maynard G, Jain S, Wolfson T, Weinger MB, Rutledge T. Intern to attending: Assessing stress among physicians. Acad Med. 2009; 84(2):251–57. doi:10.1097/acm.0b013e3181938aad.

Baethge A, Rigotti T. Interruptions to workflow: Their relationship with irritation and satisfaction with performance, and the mediating roles of time pressure and mental demands. Work Stress. 2013; 27(1):43–63. doi:10.1080/02678373.2013.761783.

Ferdous R, Osmani V, Marquez JB, Mayora O. Investigating correlation between verbal interactions and perceived stress. In: 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE: 2015. p. 1612–15. doi:10.1109/embc.2015.7318683.

Matta FK, Scott BA, Colquitt JA, Koopman J, Passantino LG. Is consistently unfair better than sporadically fair? an investigation of justice variability and stress. Acad Manage J. 2017; 60(2):743–70. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0455.

Reicherts M, Pihet S. Job newcomers coping with stressful situations: A micro-analysis of adequate coping and well-being. Swiss J Psychol. 2000; 59(4):303–16. doi:10.1024//1421-0185.59.4.303.

Gervais RL. Menstruation as a work stressor: Evidence and interventions In: Gervais R. L., Millear P. M., editors. Exploring Resources, Life-Balance and Well-Being of Women Who Work in a Global Context. Springer: 2016. p. 201–18. Chap. 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31736-6_1 .

Boudreaux E, Jones GN, Mandry C, Brantley PJ. Patient care and daily stress among emergency medical technicians. Prehospital Disaster Med. 1996; 11(3):188–93. doi:10.1017/s1049023x0004293x.

Shively M, Rutledge T, Rose BA, Graham P, Long R, Stucky E, Weinger MB, Dresselhaus T. Real-time assessment of nurse work environment and stress. J Healthc Qual. 2011; 33(1):39–48. doi:10.1111/j.1945-1474.2010.00093.x.

Baethge A, Deci N, Dettmers J, Rigotti T. “some days won’t end ever”: Working faster and longer as a boundary condition for challenge versus hindrance effects of time pressure. J Occup Health Psychol. 2019; 24(3):322–32. doi:10.1037/ocp0000121.

Buunk BP, Peeters MCW. Stress at work, social support and companionship: Towards an event-contingent recording approach. Work Stress. 1994; 8(2):177–90. doi:10.1080/02678379408259988.

Weenk M, Alken APB, Engelen LJLPG, Bredie SJH, van de Belt TH, van Goor H. Stress measurement in surgeons and residents using a smart patch. Am J Surg. 2018; 216(2):361–68. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.05.015.

Steptoe A. Stress, social support and cardiovascular activity over the working day. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000; 37(3):299–308. doi:10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00109-4.

Johnston D, Bell C, Jones M, Farquharson B, Allan J, Schofield P, Ricketts I, Johnston M. Stressors, appraisal of stressors, experienced stress and cardiac response: A real-time, real-life investigation of work stress in nurses. Ann Behav Med. 2016; 50(2):187–97. doi:10.1007/s12160-015-9746-8.

van Hooff MLM. The daily commute from work to home: Examining employees’ experiences in relation to their recovery status. Stress Health. 2015; 31(2):124–37. doi:10.1002/smi.2534.

Diebig M, Bormann KC. The dynamic relationship between laissez-faire leadership and day-level stress: A role theory perspective. Ger J Hum Resour Manag. 2020; 34(3):324–44. doi:10.1177/2397002219900177.

Wood S, Michaelides G, Totterdell P. The impact of fluctuating workloads on well-being and the mediating role of work-nonwork interference in this relationship. J Occup Health Psychol. 2013; 18(1):106–19. doi:10.1037/a0031067.

Levin S, France DJ, Hemphill R, Jones I, Chen KY, Rickard D, Makowski R, Aronsky D. Tracking workload in the emergency department. Hum Factors. 2006; 48(3):526–39. doi:10.1518/001872006778606903.

Tadić M, Bakker AB, Oerlemans WGM. Work happiness among teachers: A day reconstruction study on the role of self-concordance. J School Psychol. 2013; 51(6):735–50. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2013.07.002.

Elfering A, Semmer NK, Grebner S. Work stress and patient safety: Observer-rated work stressors as predictors of characteristics of safety-related events reported by young nurses. Ergonomics. 2006; 49(5-6):457–69. doi:10.1080/00140130600568451.

Almeida DM, Davis KD. Workplace flexibility and daily stress processes in hotel employees and their children. Ann Am Acad Politi Soc Sci. 2011; 638(1):123–40. doi:10.1177/0002716211415608.

Download references

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Research Foundation – Flanders, Belgium (FWO) under Grant (project no. G.0318.18N); and the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) under Grant (project ref. N2-0081).

Author information

Junoš Lukan and Larissa Bolliger contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Intelligent Systems, Jožef Stefan Institute, Jamova cesta 39, Ljubljana, 1000, Slovenia

Junoš Lukan & Mitja Luštrek

Jožef Stefan Postgraduate School, Jamova cesta 39, Ljubljana, 1000, Slovenia

Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Ghent University, C. Heymanslaan 10, Ghent, 9000, Belgium

Larissa Bolliger, Dirk De Bacquer & Els Clays

Knowledge Centre for Health Ghent, Ghent University, C. Heymanslaan 10, Ghent, 9000, Belgium

Nele S. Pauwels

Ghent University Hospital, C. Heymanslaan 10, Ghent, 9000, Belgium

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The following authors all contributed to this work: Junoš Lukan (JL), Larissa Bolliger (LB), Nele S. Pauwels (NP), Mitja Luštrek (ML), Dirk De Bacquer (DB), Els Clays (EC). The roles they shared according to the CRediT designations are as follows. Conceptualization: JL, LB, ML, EC Data curation: JL, LB Formal analysis: JL, LB Funding acquisition: ML, DB, EC Investigation: JL, LB Methodology: Not applicable Project administration: JL, LB, ML, EC Resources: NP Software: Not applicable Supervision: NP, ML, DB, EC Validation: Not applicable Visualization: JL Writing - original draft: JL, LB Writing - review & editing: JL, LB, NP, ML, EC. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Larissa Bolliger .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Tables 1 and 2 show work environment risk factors and stress outcomes, respectively, together with the tools used to measure them in original studies. They are ordered in broader categories according to the 6th European Working Conditions Survey [ 29 ] and with respect to the stress model of Ice and James [ 30 ].

Additional file 2

Correlations were extracted from studies that reported them. They are listed in a spreadsheet to enable replication of analyses. These correlations were counted to produce Fig. 2 in the main body of text.

Additional file 3

The full search strategies with indexing terms and free text words for all the databases searched: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, CINAHL, ERIC, and PsycArticles.

Additional file 4

The PRISMA Checklist noting the page numbers of all necessary review items.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lukan, J., Bolliger, L., Pauwels, N.S. et al. Work environment risk factors causing day-to-day stress in occupational settings: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 22 , 240 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12354-8

Download citation

Received : 09 April 2021

Accepted : 29 November 2021

Published : 05 February 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12354-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Day-to-day stress

- Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA)

- Work environment risk factors

- Stress outcomes

- Systematic literature review

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

Stress at work

- Related content

- Peer review

This article has a correction. Please see:

- Errata - June 29, 2017

- Thomas Despréaux , chief resident 1 2 3 ,

- Olivier Saint-Lary , general practitioner , senior lecturer 4 5 ,

- Florence Danzin , psychiatrist 1 6 ,

- Alexis Descatha , occupational/emergency practitioner , professor 1 2 3

- 1 Occupational health unit, University hospital of Poincaré site, Garches, France

- 2 Versailles St-Quentin University, Versailles, France

- 3 CESP, U 1018 Inserm, Villejuif, France

- 4 Versailles Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, Faculty of Health sciences Simone Veil, Department of Family Medicine, Montigny le Bretonneux, France

- 5 Université Paris-Saclay, University Paris-Sud, Villejuif, France

- 6 Charcot Psychiatric Hospital, France

- Correspondence to O Saint-Lary olivier.saint-lary{at}uvsq.fr

What you need to know

Long working hours and strain at work contribute to stress, ill health, and increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and mental illnesses

Explore occupational factors such as an imbalance between effort and reward, work overload, bullying, and job insecurity

Workplace interventions, a short period of leave from work, and psychological treatment can be considered, alongside regular follow-up to assess how the patient is coping

A 55 year old senior executive presents with low back pain. He appears anxious. A reorganisation within his company has increased his workload and he has been working more hours but receiving no recognition from management. Last week he felt humiliated by a colleague. Since then he has not been able to sleep for more than a couple of hours each day.

Stress accounts for more than a third of all cases of work related ill health and almost half of all working days lost due to illness. 1 Internationally, systematic reviews and meta-analysis of observational data suggest that job strain and poorly functioning work environments are associated with the development of depressive symptoms. 2 3 4 A longitudinal cohort study from Norway found workplace bullying to be associated with subsequent suicidal ideation. 5 Long working hours are also associated with increased risk of stroke, heart disease, 6 and diabetes, 7 and poor lifestyle including inactivity, 7 smoking, 7 and risky alcohol use. 8

Patients might present with unexplained somatic symptoms, such as odd aches and pains, palpitations, loss of appetite, and loss of sleep. 9 10 Explore their symptoms and discuss any contributing factors in their work and personal life. The consultation can be long and difficult, as the patient might not volunteer all the information or draw the association with work stress. The objective of this first consultation is to perform a quick risk assessment and explore factors in the patient’s job that are contributing to stress.

What you should cover

The following questions are based on systematic reviews, and the experiences of clinicians and patients.

• the nature and duration of the patient’s presenting symptoms

• associated depressive symptoms, such as

o feeling down, low, or sad

o loss of interest in activities

o tiring easily

o lack of concentration

o changes in sleep and appetite

• feelings of hopelessness, (eg, a belief that the situation cannot improve) 11

• occupation, working environment, and stressors at work (box 1)

• the chronology of events, how the patient has coped so far, and if things have changed recently in their workplace. Typically, three phases are described 13 :

an initial (“serene”) phase, where the patient reports no particular difficulty

a “problem” phase, when obstacles and conflicts gradually appear and the patient tries to deal with the situation

a “crisis” phase, where s/he comes to see you

• protective factors for severity of outcome include a supportive family environment and financial wellbeing. Aggravating factors are familial isolation, being a single parent with young children, having financial difficulties, or being bound by a particular type of employment contract that forces the patient to stay in the same job. The latter can delay diagnosis, and limit the range of remedial options available.

• thoughts of ending their life or causing harm to themselves or others

• other medical illnesses, including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular events, or psychiatric disorders

• smoking, alcohol, and drug abuse

• family history of depression or mental disorders, which could increase the risk of depression and suicide

Box 1: Occupational factors for stress 2 12 13

Conflict of values (being asked to do a poor quality job or cut costs for a person who likes to keep high standards in their work)

Feeling insufficiently rewarded compared with the person’s assessment of their efforts (“effort-reward imbalance”)

Inability to make decisions about when or how to stop work

Lack of support from colleagues and management

Isolation at work (no cooperation between teams)

Work overload (working after hours) or insufficient workload (nothing to do)

Discrimination, humiliation, violence, bullying, and harassment at work

Cases of work related stress in the same company

Company situation in terms of finances, organisational changes, and employee turnover

Job insecurity, temporary employment status

Patients come to their doctor primarily to address their symptoms, but some will also want assistance and advice on how to cope with the situation at work.

Examination

Assess general appearance and look for signs of psychomotor agitation such as restlessness, rapid talking, and racing thoughts, or of psychomotor retardation such as apparent exhaustion and visible slowing of physical activity. These might indicate a mental illness or organic cause, such as a thyroid disorder.

Perform a quick general examination to look for fever, tachycardia, hypertension, and signs of thyroid disorder (which can be a differential diagnosis). Examine thoroughly for reported pain, though somatisation is likely.

What you should do

Investigation and management of physical and mental health diagnoses —Offer usual management of conditions such as depression. Consider immediate referral to psychiatry if the patient describes suicidal or aggressive thoughts or intentions.

Make the connection between the patient’s experience and work stress —For patients with work related stress and a variety of symptoms, acknowledge their situation and validate their feelings with a phrase such as, “I understand that you are suffering and that this feeling is arising from a stressful work environment.”

Offer a supportive setting to discuss and make progress in dealing with work stress —High quality evidence and guidelines for interventions to manage work related adjustment issues and stress are lacking. 14 Cognitive therapy, stepwise reintegration planning, and relaxation training can all be considered. 15 16 Therapy needs to be supportive, active, flexible, goal directed, and time bound. 10 12 14

Consider offering a second appointment—for example, if there is too much to cover. You might suggest that the patient brings a family member to the next appointment for support.

In the interim, you might ask the patient to reflect on their job and personal situation, and possibly to write a short description of their problems at work, the chronology of these problems, and their relationship to the patient’s symptoms. In our experience, some patients find this helps them reflect on the events, and it can help you understand their situation better. This will help to initiate discussion on strategies that the patient might employ to navigate their workspace going forward. Making contact with the workplace to modify work or reduce workload in collaboration with the employer can be helpful. Discuss whether the occupational health services or human resources division at the patient’s company could be involved. In some circumstances, patients might wish to seek compensation or take legal action. Explore if these are important for your patient and direct them to appropriate agencies or lawyers who can help with these matters.

Consider whether the patient wants or might benefit from time away from work including a “sick note.”

Schedule a follow-up visit to assess how the patient is coping with symptoms and workplace issues, and modify the approach accordingly.

Education into practice

What factors would you typically explore in the patient’s history to understand their working environment and stress? Does this article offer you ideas on how to do so differently?

Sometimes, asking the patient to write down their problems at work, the times at which the problems occurred, and the patient’s symptoms, is helpful. Are there ways in which you might consider using this or other techniques to help patients better organise their thoughts or understand them yourself?

Do you offer a second appointment, if there is too much to cover, or if the patient wishes to include a friend or family member?

In difficult cases, do you work in collaboration with mental health professionals as well as occupational health professionals?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

Patients in our practice reported a need to rethink what they had experienced at work and to share this in writing. This helped them identify and clearly communicate the chronology of events. Based on their feedback we recommend encouraging patients to write about their work environment and factors contributing to stress, though this need not be mandatory.

A patient reviewed this article and attested that writing a two page memorandum would have been enormously helpful to identify problems at work and how they had escalated over time, and to come to terms with the situation.

We would like to thank Richard Carter for helping us to improve the language of this document.

We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests.

Patient consent obtained.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

- ↵ Statistics—Work related stress, anxiety and depression statistics in Great Britain (GB). http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causdis/stress

- ↵ Theorell T, Hammarström A, Aronsson G, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015 ; 15 : 738 . doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4 . pmid:26232123 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Rugulies R, Aust B, Madsen IE. Effort-reward imbalance at work and risk of depressive disorders. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scand J Work Environ Health 2017 ; 17 : 3632 . doi:10.5271/sjweh.3632 . pmid:28306759 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Harvey SB, Modini M, Joyce S, et al. Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup Environ Med 2017 ; 74 : 301 - 10 . doi:10.1136/oemed-2016-104015 . pmid:28108676 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Nielsen MB, Einarsen S, Notelaers G, Nielsen GH. Does exposure to bullying behaviors at the workplace contribute to later suicidal ideation? A three-wave longitudinal study. Scand J Work Environ Health 2016 ; 42 : 246 - 50 . doi:10.5271/sjweh.3554 . pmid:27135593 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Kivimäki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, et al. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603 838 individuals. Lancet 2015;386:1739-46. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60295-1

- ↵ Nyberg ST, Fransson EI, Heikkilä K, et al. Job Strain and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: Meta-Analysis of Individual-Participant Data from 47 000 Men and Women. Testa L, ed. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e67323. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067323

- ↵ Virtanen M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, et al. Long working hours and alcohol use: systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies and unpublished individual participant data. BMJ 2015;350:g7772. doi:10.1136/bmj.g7772

- ↵ American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing 2013.

- ↵ van der Klink JJL, van Dijk FJH. Dutch practice guidelines for managing adjustment disorders in occupational and primary health care. Scand J Work Environ Health 2003 ; 29 : 478 - 87 . doi:10.5271/sjweh.756 pmid:14712856 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Fraser L, Burnell M, Salter LC, et al. Identifying hopelessness in population research: a validation study of two brief measures of hopelessness. BMJ Open 2014 ; 4 : e005093 . doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005093 . pmid:24879829 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bruinvels D, Frings-Dresen M. Psychosocial work environment and stress-related disorders, a systematic review. Occup Med (Lond) 2010 ; 60 : 277 - 86 . doi:10.1093/occmed/kqq081 . pmid:20511268 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Mediouni Z, Garrabé H, Jaworski F, et al. Initial evaluation of patients reporting a work-related stress or bullying. J Occup Environ Med 2012 ; 54 : 1439 - 40 . doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e31827942e0 . pmid:23222476 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Joosen MCW, Brouwers EPM, van Beurden KM, et al. An international comparison of occupational health guidelines for the management of mental disorders and stress-related psychological symptoms. Occup Environ Med 2015 ; 72 : 313 - 22 . doi:10.1136/oemed-2013-101626 . pmid:25406476 . OpenUrl

- ↵ West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016 ; 388 : 2272 - 81 . doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X . pmid:27692469 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Van den Broeck K, Remmen R, Vanmeerbeek M, Destoop M, Dom G. Collaborative care regarding major depressed patients: A review of guidelines and current practices. J Affect Disord 2016 ; 200 : 189 - 203 . doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.044 . pmid:27136418 . OpenUrl

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Stress at the Workplace and Its Impacts on Productivity: A Systematic Review from Industrial Engineering, Management, and Medical Perspective

2022, Industrial Engineering & Management Systems

In every fast-paced surrounding, stress is present in every life aspect, including at the workplace. It is a deeply personal experience, with various stressors affecting every individual differently. This study assessed the past and present workplace stress-related information and analyzed its impact on productivity. It primarily concentrates on the field's philosophical principles, while providing a collection of directions for future study as well. This study was formed in the statement of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis). The impact of stress at the workplace on the employee's productivity was observed in the cohort and cross-sectional studies from the perspective of industrial engineering, management, and medicine. Four eligible studies were qualitatively assessed from 2,642 identified literature through four databases (Cochrane, Science Direct, Scielo, and PubMed) using keywords stress, impact, productivity, industrial engineering, management, and medicine. The study was convinced that stress at the workplace contributes to worsening relationships at home, worsening relationships between superiors and subordinates as well as contracting diseases. It has a potential negative impact on productivity. Furthermore, the work environment plays a significant contribution in inducing workplace stress because of human physiologic response. Noxious stress is detrimental to the human body, especially if maintained in the long run. Therefore, stress management is imperative before it is too late.

Related Papers

Ebenezer Ofosuhene

This review of the literature gives information about work stress, factors in the working environment that cause stressful situations and negative health consequences of the workplace stress. Stressors are pointed out in details that lead to stress at the workplace. Approaches to the stress are explained and most famous models of the stress are assessed critically in this review. This article highlights the work stress and its adverse effects on the physical and mental health of an employee. Finally, recommendations for future research are given and areas are highlighted where there is need of more empirical research.

Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health

Umesh Maiya

Stress is much in the news at present but it isn't a new problem. Pressure is part and parcel of all work and helps to keep us motivated. But excessive pressure can lead to stress which undermines performance, is costly to employers and can make people ill. Research reveals that many working days are lost to stress, depression and anxiety. Work-related stress costs a huge burden to the society. Stress takes many forms as well as leading to anxiety and depression it can have a significant impact on an employee's physical health. Research links stress to heart disease, back pain, headaches, gastrointestinal disturbances and alcohol and drug dependency. Individuals are more willing to admit that they are suffering from stress if they can expect to be dealt with sympathetically. In some cases good counseling may be all that is needed. This paper aims at studying the stressors that affects an individual at work, to examine the effects of stress and suitable measures which employe...

AAOHN Journal

Bonita Long

Michael Murray

Rex Journal

In today's age of automation, advanced technology & high competition, man has great dreams of a luxurious living & enjoys at the thought of experiencing it. It is a well-accepted fact that every human being is an individual with his own unique characteristics & ways of responding & behaving. These various ways of responding & behaving can be either positive or negative & these can make one's life a happy or a miserable one. These facts are true for every individual in every sphere of life. In today's fast moving world every individual strives hard to achieve their dreams & the best of luxurious living but faces stress in the process of doing so. The present study will bring to light the stress level, sources of stress & stress management strategies.

Littera Scripta

Andrea Bencsik

Erick Onsongo