An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier Sponsored Documents

The power of positive thinking: Pathological worry is reduced by thought replacement in Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Claire eagleson.

a King's College London, Institute of Psychology, Psychiatry and Neuroscience, London, UK

Sarra Hayes

b Curtain University, Perth, Australia

Andrew Mathews

c University of California, Davis, USA

Gemma Perman

d Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, UK

Colette R. Hirsch

Worry in Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), takes a predominantly verbal form, as if talking to oneself about possible negative outcomes. The current study examined alternative approaches to reducing worry by allocating volunteers with GAD to conditions in which they either practiced replacing the usual form of worry with images of possible positive outcomes, or with the same positive outcomes represented verbally. A comparison control condition involved generating positive images not related to worries. Participants received training in the designated method and then practiced it for one week, before attending for reassessment, and completing follow-up questionnaires four weeks later. All groups benefited from training, with decreases in anxiety and worry, and no significant differences between groups. The replacement of worry with different forms of positive ideation, even when unrelated to the content of worry itself, seems to have similar beneficial effects, suggesting that any form of positive ideation can be used to effectively counter worry.

- • People with GAD practiced replacing worry with alternatives for one week.

- • Alternatives were positive outcomes rehearsed as images or verbal thoughts.

- • A control group rehearsed positive images unrelated to their worries.

- • One month later all groups reported significantly reduced anxiety and worry.

- • Unexpectedly, even unrelated positive ideation can effectively counter worry.

1. Introduction

Excessive worry is a common symptom in anxiety disorders and is the central feature of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). In Hirsch and Mathews' (2012) model of pathological worry three processes combine to maintain uncontrollable worry: emotional processing biases, impaired attentional control and the tendency to represent possible negative outcomes in over-general verbal form. The aim of the study reported here was to investigate the effects of different methods designed to modify this last process in pathological worriers with GAD.

Worry is predominantly verbal, as if talking to oneself about possible negative outcomes, whereas imagery is relatively infrequent, and tends to be brief ( Freeston et al., 1996 , Hirsch et al., 2012 ). In contrast, when instructed to relax, non-worriers report primarily images whereas those with GAD report similar amounts of verbal thought and imagery ( Borkovec & Inz, 1990 ). The latter authors suggested that verbal worry may be a strategy to avoid more distressing emotional representations, such as images ( Borkovec, Alcaine, & Behar, 2004 ). In partial support of this idea, Butler, Wells, and Dewick (1995) found that instructions to worry (verbally) about a distressing film led to less anxiety immediately afterwards than did instructions to think about it in images. However, verbal worry led to more intrusive images in the days following than did thinking in images. Thus, even if verbal worry leads to temporary reductions in anxiety, it can maintain negative thought intrusions in the longer term.

Similarly, high worriers given instructions to worry verbally reported increased negative thought intrusions from pre- to post-worry, but those instructed to worry in images actually showed a decrease ( Stokes & Hirsch, 2010 ). This suggests that verbal thinking style plays a causal role in maintaining intrusions, perhaps serving to trigger subsequent worry episodes. The question of why verbal-based worry elevates intrusive thoughts remains unanswered. One possibility is that verbal thoughts in worry tend to be relatively abstract and over-general, raising many vague possibilities but reducing the possibility of resolving them because they are not clearly defined ( Stöber, Tepperwien, & Staak, 2000 ), which may instead maintain perceived threat ( Philippot, Baeyens, & Douilliez, 2006 ).

Alternatively, increased intrusive thoughts may arise from the detrimental effects of verbal worry on attention and attentional control ( Stefanopoulou, Hirsch, Hayes, Adlam, & Coker, 2014 ). Leigh and Hirsch (2011) demonstrated that verbal worry in high worriers impairs attentional control (compared to non-worriers), but this group difference disappears after worrying using images. Furthermore, Williams, Mathews, and Hirsch (2014) demonstrated that verbal worry increased attentional bias towards threat, but worrying in imagery did not. This evidence suggests that verbal-based worry can maintain intrusive thoughts about threats, in contrast to imagery-based worry.

So far we have only considered thinking about negative (worry-related) rather than positive topics. Encouraging imagery of alternative positive outcomes might be particularly helpful, by competing in affective valence with the usual negative content of worry. Indeed, Hirsch, Perman, Hayes, Eagleson, and Mathews (2015) found that practice in thinking about worry topics in more positive ways (whether verbally or in images) reduced subsequent intrusions compared with worry in verbal form, although this reduction was not significantly greater than that seen following similar practice using imagery of negative outcomes. However, only practice in thinking about alternative positive outcomes (whether as images or in verbal form) also reduced the rated cost of worry outcomes and increased perceived ability to cope with them. Thus it seems likely that practice with positive representations has benefits beyond those produced by worry-related imagery alone.

Alternatively, it could be that verbal worry is best countered by generating opposing positive thoughts in the same (verbal) modality, because this would more directly compete with the negative outcomes rehearsed in worry. It may be, for example, that worry-related intrusions (in verbal form) are more likely to prime alternative positive verbal outcomes that were rehearsed earlier, in comparison to positive images, which would require an additional shift from a semantic to a perceptual modality.

This is the first study to investigate whether extended practice with positive alternatives to worry, either in verbal or imagined form, has lasting effects on anxiety and worry in GAD. Volunteers with GAD were allocated either to practice in replacing the usual form of worry with images of positive outcomes, or in which positive outcomes were represented in verbal form. Both conditions tested the hypothesis that rehearsing positive outcomes for worry-related concerns should counter negative expectations and reduce worry. However, reductions in worry could conceivably result from replacing negative content with any form of positive ideation, whether or not designed to challenge the negative meanings rehearsed in worry. If so, similar effects would follow practice in replacing worry with positive ideation unconnected with worry content. Accordingly, in a third (control) condition participants were instructed to practice positive images unrelated to their worry.

2.1. Overview of design

Volunteers with GAD were randomly allocated to one of three conditions: (i) practice in generating mental images of positive outcomes to worry topics (positive imagery of worry, PIW); (ii) practice in generating verbal descriptions of positive worry-related outcomes (positive verbal representations of worry, PVW); or (iii) practice in generating positive images unrelated to any current concerns (positive imagery of non-worry, PIN). All participants completed an initial face-to-face training session, followed by a week of practice in their assigned condition exercise at home, before returning for a post-training assessment session and then completing follow-up questionnaires one month later.

2.2. Participants

Participants were volunteers aged 18 to 65, recruited from the community via advertisements, who met criteria for GAD on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I (SCID-I; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1996 ), and who had English as their first language. Exclusion criteria included a history of Bipolar Disorder or psychosis, and current psychological therapy (past therapy was acceptable). If participants were taking medication for anxiety or depression, they had to be on a stable dose for at least one month prior to taking part. One hundred and fifty participants were initially recruited and attended the first assessment session. Of those, 21 were excluded as not meeting criteria for GAD and one who had just begun Cognitive Behavior Therapy.

Of the 128 participants who met criteria, 26 were excluded: two for not following instructions during initial practice; four failed to attend for reassessment; two did not return follow-up questionnaires; six completed less than 50% of their assigned practice; and 12 reported being unable to think as instructed for most of the time during a check in session 2. A chi-square goodness-of-fit analysis revealed no significant differences in the number excluded across groups, χ 2 (2, n = 128) = 1.56, ns . Analyses were conducted on data from the remaining participants (32 PIW, 35 PVW and 35 PIN).

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1 . There were no group differences in gender, χ 2 (2, n = 102) = 1.43, ns; age, F (2, 99) = .48, ns ; education, F (2, 99) = .79, ns ; Penn State Worry Questionnaire scores (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990 ), F (2, 99) = 1.71, ns; State Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait (STAI-T; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983 ), F (2, 99) = .49, ns ; Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994 ), F (2, 99) = .50, ns ; Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996 ), F (2, 99) = 2.11, ns , or number of negative intrusions during the initial breathing focus task (see below), F (2, 99) = .22, ns .

Table 1

Mean (SD) participant characteristics.

PSWQ= Penn State Worry Questionnaire; STAI-T = State Trait Anxiety Index- Trait version; LOT-R = Life Orientation Test- Revised version; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II.

2.3. Breathing focus task

This task was adapted from the Worry Task ( Hayes, Hirsch, & Mathews, 2010 ; Hirsch, Mathews, Lequertier, Perman, & Hayes, 2013 ). Participants were asked to focus on their breathing for five minutes, and when a tone sounded (on 12 random occasions), to indicate whether they were thinking about their breathing, or something else. If the latter, they classified their thought as positive, negative, or neutral, and gave a brief summary of its content (e.g. “positive: going out tonight”). At the end of the task, participants recorded a fuller description of each thought, allowing an independent assessor, blind to thought origin, to categorize each as positive, negative, or neutral. Negative thoughts were further classified as low, medium or high in negativity. Another assessor classified 25% of participants' reports ( n = 30; ten per group selected at random); inter-rater reliability for valence classification using Cohen's kappa statistic (κ) was .75, and for negativity .71.

2.4. Instructions for each intervention condition

2.4.1. positive imagery of worry (piw).

Participants identified three current worry topics and rated how distressing each was; how often they had worried about it over the past week, and how controllable it was, using 0–10 scales. The difference between verbal thoughts and images was then described, and participants informed they would be practicing thinking in mental imagery rather than verbally. They were then asked to produce a vivid image regarding friendship and hold it for 30 s, re-focusing on imagery if verbal thoughts occurred, and then rated how well they had thought in their designated thinking style (imagery), from 0 (not at all) to 10 (completely), and the percentage of thoughts that were positive, negative or neutral. Participants then read a worry description (concerns about paying a bill), and were asked to think of how the scenario could have a positive outcome. For two more descriptions they were instructed to generate vivid images of the situation turning out positively (for one and two minutes respectively), with ratings as before, used by the experimenter to encourage appropriate imagery.

Finally, participants generated lists of potential positive outcomes for each of their own three worry topics, followed by imagining each for two minutes. Designated thinking style and valence ratings were collected as a manipulation check.

2.4.2. Positive verbal worry (PVW)

Instructions were as for PIW, but instead of imagery participants were instructed to think (and then write down) verbal descriptions, and rate their use of verbal mentation (0–10). If participants reported any images, they were instructed to refocus their minds on verbal thoughts.

2.4.3. Positive imagery non-worry (PIN)

This was the same as the positive imagery of worry condition, except that instead of an image of positive worry-related outcomes, participants were instructed to imagine something positive that was completely unrelated to the worry scenario they had read, or to any of their own worry topics.

2.5. Procedure

Participants were sent the PSWQ and STAI-T to complete and bring to the first session, which they began by completing the BDI-II and the LOT-R, and after a 45 s practice, the breathing focus task, followed by the GAD module of the SCID-I. Participants then completed the designated mentation style training and were instructed to use this style anytime they noticed themselves worrying during the following week. They were also asked to repeat the imagery/verbal practice with each of their three worry topics for two minutes daily, and to record this on a homework diary sheet.

Participants attended again one week later for reassessment. Homework diaries were collected and participants repeated the PSWQ, STAI-T and LOT-R, followed by the breathing focus task. As an indirect check on adherence, participants' ability to reproduce the required daily practice was assessed by asking them to repeat the homework without reminders or prompting, after which they rated the verbal/imagery content and proportion of positive thoughts experienced. To examine participants’ ability to disengage from worry they rated how often (0 Never-10 Very often) they could stop worries that occurred outside of the homework exercise period. Participants were not explicitly asked to continue practicing the exercise after session 2. A month after this reassessment session participants completed (by mail) the PSWQ and STAI-T.

3.1. Manipulation check

Session 1 involved training in the designated thinking style. The criterion for successful completion of the exercise was a score of 6 or higher (on a 10 point scale) in engaging with the designated thinking style (imagery or verbal) and 60% benign mentation (% positive and neutral content). During session 1 practices using the participant's worry topics, all groups were able to use their designated thinking style well above the cutoff (PIW: M = 8.10, sd . = 1.37; PVW: M = 8.45, sd. = 1.44; PIN: M = 7.83, sd. = 1.58). A one-way ANOVA revealed there were no significant differences between groups, F (2, 99) = 1.57, ns . All groups were also found to produce benign valence content above the cutoff point (PIW: M = 87.51, sd. = 9.72; PVW: M = 83.93, sd. = 12.00; PIN: M = 89.03, sd. = 9.11), with no significant differences between them, F (2, 99) = 2.23, ns .

A manipulation check was also administered during session 2 in the form of an adherence check, with mean scores on the above ratings again well above cut-offs, with no differences between groups. For designated thinking style (PIW: M = 8.83, sd . = 1.29; PVW: M = 8.93, sd. = 1.13; PIN: M = 8.36, sd. = 1.19), there were no significant differences between groups, F (2, 99) = 2.25, ns , nor for benign content (PIW: M = 94.78, sd . = 6.97; PVW: M = 94.57, sd. = 8.38; PIN: M = 94.03, sd. = 6.26), F (2, 99) = .10, ns .

3.2. Breathing focus task

The number of negative thought intrusions was analyzed in a mixed-model ANOVA, with one group factor (PIW, PVW, PIN) and two repeated factors: time (session 1–2) and assessor (self, independent). There was a significant main effect of time, λ = .52 , F (1, 99) = 92.94, p < .001, η p 2 = .48 , with fewer negative intrusions reported in session 2 (3.6 down to 1.7). However, there were no significant main effects for group or rater, nor any significant interactions.

A Chi-square analysis similarly failed to reveal any differences between groups in the proportion of thoughts classified as low, medium or high in negativity by an independent rater ( Preacher, 2001 ). For the post-intervention breathing focus task, medium and high negativity thoughts were collapsed due to low numbers of highly negative thoughts. The proportion of low versus medium/high negativity thoughts did not differ by group, χ 2 (2, N = 206) = 2.73, ns . Across all groups, negative intrusions reduced over time (from 194 to 98 for low and 203 to 108 for medium/high negativity respectively), but the proportion of low to medium/high did not change, χ 2 (1, N = 603) = .90, ns . In summary, all negative thoughts reduced over time, with no apparent differences due to group.

3.3. Effects of training on worry and anxiety

Mixed model ANOVAs were carried out on PSWQ and STAI-T scores, with one group factor and one repeated measures factor of time (session 1, session 2, follow-up). For the PSWQ, the only significant finding was a main effect of time, λ = .40, F (2, 98) = 74.40, p < .0005, η p 2 = .50, with all groups showing reductions in worry across time (see Table 2 for means). Paired-samples t-tests revealed significant decreases from session 1 to 2, t (101) = 8.64, p < .001, and session 2 to follow-up, t (101) = 6.47, p < .001. Similarly, for the STAI-T, the only significant finding was a main effect of time, λ = .52, F (2, 98) = 45.61, p < .0005, η p 2 = .38, with significant decreases from session 1 to 2, t (101) = 6.34, p < .001, and session 2 to follow-up, t (101) = 5.73, p < .001. Analysis of the LOT-R (a measure of optimism) assessed at session 1 and 2 only, also revealed a main effect of time, λ = .69, F (1, 99) = 43.64, p < .0005, η p 2 = .29, with increased optimism overall, but no other significant effects. Thus, in all groups, worry and trait anxiety decreased significantly over time, while positive feelings of optimism increased, without any indication that this effect differed across conditions (all interaction F 's < 1).

Table 2

Mean (SD) scores on the PSWQ, STAI-T and LOT-R at each time point.

Note: PSWQ= Penn State Worry Questionnaire; STAI-T = State Trait Anxiety Index- Trait version; LOT-R = Life Orientation Test- Revised version. High scores on LOT-R indicate optimism.

The unexpected lack of group differences in worry or anxiety raises the question of whether, in the absence of a non-intervention control, all our conditions were equally effective, or equally ineffective. We therefore compared the effect size of changes observed in the present groups with those reported for non-treated control groups in two recent meta-analyses of psychological treatment for GAD ( Cuijpers et al., 2014 , Hanrahan et al., 2013 ). Studies were identified in which means and standard deviations were reported for non-treated groups over a follow-up period (ranging from 4 to 16 weeks) and in which participants completed the STAI-T (8) and/or the PSWQ (12). The average within-group effect size (Cohen's d) in these untreated groups was .10 for the STAI-T (ranging from −.27 to .32, sd . 0 .20) and .03 for the PSWQ (ranging from −.72 to .41, sd . .28). The effect size for the equivalent changes observed in the present study for the STAI-T ranged from .91 for the PIW group, to 1.01 for the PIN group, and 1.07 for the PVW group, giving an overall effect size of 1.0 for all participants; and for the PSWQ from 1.52 for the PIN group, to 1.86 for the PIW group, and 2.50 for the PVW group, giving an overall effect size of 1.92. The effects observed in the present study were thus well outside the range reported for untreated control groups, indicating that all the present interventions were indeed effective.

3.4. Post-hoc investigation of process variables associated with reduction in worry

Given there were no differences in outcome among the present groups, post-hoc analyses reported below combined all groups to identify relevant process variables.

3.4.1. Negative thought intrusions during breathing focus

Since there was no significant effect of rater, the number of negative thought intrusions during session 2 was averaged across self and assessor. Mean negative intrusions were significantly correlated with PSWQ at follow-up, r = .27, p < .01. To explore this finding further, stepwise regression was conducted predicting PSWQ follow-up scores, entering baseline PSWQ and negative intrusions at step one, with session 2 negative intrusions added at step two. PSWQ and negative intrusions at baseline accounted for 15.8% of the variance and intrusions at session 2 predicted an additional 4.6% of the variance, R squared change = .046, F change (1, 98) = 5.70, p < .05.

Negative intrusions at session 2 were correlated with STAI-T trait scores at follow-up, r = .32, p < .05. As before, in regression analysis predicting final STAI-T, baseline anxiety and average negative intrusions accounted for 30.7% of the variance, but entering negative intrusions in step two did not significantly improve the prediction, R squared change = .018, F change (1, 98) = 2.59, p = .11. Hence, while fewer negative intrusions following homework practice predicted greater reductions in worry on the PSWQ, this effect did not generalize to trait anxiety.

3.4.2. Ability to generate positive thoughts

The percentage of positive thoughts generated during the adherence check in session 2 was also correlated with PSWQ at follow-up, r = −.28, p < .005. In regression analysis predicting follow-up PSWQ, baseline PSWQ and the average percentage of positive thoughts generated in the practice scenarios in session 1 accounted for 16% of the variance. In step two, entering the percentage of positive thoughts at session 2 adherence check accounted for an additional 6.8% of the variance in final PSWQ, R squared change = .068, F change (1, 98) = 8.59, p < .01. Similarly, the correlation between positive thoughts generated in session 2 and STAI-T scores at follow-up was r = −.25, p < .05. Entering baseline STAI-T trait score and percentage of positive thoughts in the practice scenarios at step one explained 31.5% of the variance in final STAI-T, and adding positive thoughts from session 2 explained an additional 2.7%, R squared change = .027, F change (1, 98) = 3.99, p < .05.

3.4.3. Ability to disengage from worry

During session 2 reassessment participants rated how often they had been successful in terminating any spontaneously occurring worries during the week. The correlation between this rating and PSWQ score at follow-up was r = −.23, p < .05. Hierarchical regression, after baseline PSWQ was entered in the first step as before, showed that entering disengagement from worry in step two accounted for a further 4.4%, R squared change = .044, F change (1, 99) = 5.42, p < .05. Similarly, after entering baseline STAI-T trait scores at step one, adding rated ability to shift away from worries in step two explained an additional 4.1%, R squared change = .041, F change (1, 99) = 6.26, p < .05. These results suggest that, in addition to involuntary thought intrusions during breathing focus, ability to voluntarily generate positive thoughts and disengage from worry predicted greater decreases in worry and anxiety, regardless of condition.

4. Discussion

We report here the first study of GAD assessing the effects of manipulating imagery and verbal processing in the longer term reduction of worry and anxiety. The main finding was that all three groups showed significant reductions in negative intrusions, and reported worry and anxiety, with no significant differences between conditions. Unexpectedly, the control condition in which participants practiced positive imagery chosen to be unrelated to worry content did not differ significantly from the conditions that involved practicing alternative positive outcomes of worry topics, whether in verbal or imagery form. Thus, it seems that the critical mechanism underlying the observed changes was replacing the usual flow of verbal worry with any alternative positive ideation. This suggests that, even if the negative and verbal form of worry contributes to its persistence, it is not necessary to directly modify this content to produce improvement.

Consistent with this interpretation, although negative intrusion frequency was substantially reduced, when intrusions did recur, they were still rated as moderately or highly negative. In other words, practicing any positive ideation reduced the frequency of worry-related thoughts, but not their negativity. Furthermore, reduced worry at follow-up was predicted by fewer negative intrusions during breathing focus, and greater ability to generate positive thoughts and disengage from worry in session 2. The lack of overall differences between groups, together with these post-hoc findings, again suggests that rather than reducing negativity of worry, the improvements were due to improved ability to disengage from it and focus instead on more positive content. These findings converge on the idea that repeated practice in replacing worry with positive ideation can counter the intrusive and distressing properties of worry.

One challenge to this conclusion is that, in the absence of a non-intervention control, the changes would have occurred without any intervention. We have argued that this is unlikely, given that the effect sizes were large and much greater than would be expected in the absence of any treatment. Even so, we cannot conclude from the present results that it is necessary to replace worry with positive ideation, because we did not include a non-positive condition. Even instructions to imagine negative outcomes, rather than the usual quasi-verbal form, reduces later intrusive thoughts ( Hirsch et al., 2015 , Stokes and Hirsch, 2010 ), perhaps because the more concrete content of images leads to outcomes being seen as more manageable or implausible. However, only conditions involving substituting positive content had the additional effect of reducing the perceived cost of worry outcomes, and enhancing perceived ability to cope ( Hirsch et al., 2015 ).

Given that the present results were not compared with established treatments, we can make no claims for clinical effectiveness, nor would we suggest that the methods used here can be utilized as stand-alone interventions. The GAD volunteers in this study were not seeking treatment, so the utility of these methods in a clinical population is yet to be established. However, participants reported substantial improvements on measures of worry (e.g. within-group effect sizes of around 2 on the PSWQ), and these effects were maintained one month later. One clinical implication deserving further evaluation is that it may not be necessary to modify worry-related thought content directly, as is the aim of thought challenging in Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Future research could usefully compare the effectiveness of challenging negative thoughts versus practice in replacing them with any positive (or other) alternative. The latter approach may reduce negative intrusive thoughts and prevent consequent development of worry episodes, by increasing the availability of competing thoughts. At the very least, the present results indicate the need for research investigating whether modifying negative content, or enhancing access to positive alternatives, are equally or differentially effective in preventing uncontrollable worry in GAD.

5. Author note

This research was supported by grants from The Wellcome Trust (WT083204) and The Psychiatry Research Trust. The last author receives salary support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of The Wellcome Trust, The Psychiatry Research Trust, NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. Claire Eagleson is now at UNSW Australia. The authors would like to thank Ellena Cooke, Priya Kochuparampil, Zoe Maiden and Marc Williams for completing the assessor ratings and for Lewis Owens in help with referencing.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interests to declare.

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Stress management

Positive thinking: Stop negative self-talk to reduce stress

Positive thinking helps with stress management and can even improve your health. Practice overcoming negative self-talk with examples provided.

Is your glass half-empty or half-full? How you answer this age-old question about positive thinking may reflect your outlook on life, your attitude toward yourself, and whether you're optimistic or pessimistic — and it may even affect your health.

Indeed, some studies show that personality traits such as optimism and pessimism can affect many areas of your health and well-being. The positive thinking that usually comes with optimism is a key part of effective stress management. And effective stress management is associated with many health benefits. If you tend to be pessimistic, don't despair — you can learn positive thinking skills.

Understanding positive thinking and self-talk

Positive thinking doesn't mean that you ignore life's less pleasant situations. Positive thinking just means that you approach unpleasantness in a more positive and productive way. You think the best is going to happen, not the worst.

Positive thinking often starts with self-talk. Self-talk is the endless stream of unspoken thoughts that run through your head. These automatic thoughts can be positive or negative. Some of your self-talk comes from logic and reason. Other self-talk may arise from misconceptions that you create because of lack of information or expectations due to preconceived ideas of what may happen.

If the thoughts that run through your head are mostly negative, your outlook on life is more likely pessimistic. If your thoughts are mostly positive, you're likely an optimist — someone who practices positive thinking.

The health benefits of positive thinking

Researchers continue to explore the effects of positive thinking and optimism on health. Health benefits that positive thinking may provide include:

- Increased life span

- Lower rates of depression

- Lower levels of distress and pain

- Greater resistance to illnesses

- Better psychological and physical well-being

- Better cardiovascular health and reduced risk of death from cardiovascular disease and stroke

- Reduced risk of death from cancer

- Reduced risk of death from respiratory conditions

- Reduced risk of death from infections

- Better coping skills during hardships and times of stress

It's unclear why people who engage in positive thinking experience these health benefits. One theory is that having a positive outlook enables you to cope better with stressful situations, which reduces the harmful health effects of stress on your body.

It's also thought that positive and optimistic people tend to live healthier lifestyles — they get more physical activity, follow a healthier diet, and don't smoke or drink alcohol in excess.

Identifying negative thinking

Not sure if your self-talk is positive or negative? Some common forms of negative self-talk include:

- Filtering. You magnify the negative aspects of a situation and filter out all the positive ones. For example, you had a great day at work. You completed your tasks ahead of time and were complimented for doing a speedy and thorough job. That evening, you focus only on your plan to do even more tasks and forget about the compliments you received.

- Personalizing. When something bad occurs, you automatically blame yourself. For example, you hear that an evening out with friends is canceled, and you assume that the change in plans is because no one wanted to be around you.

- Catastrophizing. You automatically anticipate the worst without facts that the worse will happen. The drive-through coffee shop gets your order wrong, and then you think that the rest of your day will be a disaster.

- Blaming. You try to say someone else is responsible for what happened to you instead of yourself. You avoid being responsible for your thoughts and feelings.

- Saying you "should" do something. You think of all the things you think you should do and blame yourself for not doing them.

- Magnifying. You make a big deal out of minor problems.

- Perfectionism. Keeping impossible standards and trying to be more perfect sets yourself up for failure.

- Polarizing. You see things only as either good or bad. There is no middle ground.

Focusing on positive thinking

You can learn to turn negative thinking into positive thinking. The process is simple, but it does take time and practice — you're creating a new habit, after all. Following are some ways to think and behave in a more positive and optimistic way:

- Identify areas to change. If you want to become more optimistic and engage in more positive thinking, first identify areas of your life that you usually think negatively about, whether it's work, your daily commute, life changes or a relationship. You can start small by focusing on one area to approach in a more positive way. Think of a positive thought to manage your stress instead of a negative one.

- Check yourself. Periodically during the day, stop and evaluate what you're thinking. If you find that your thoughts are mainly negative, try to find a way to put a positive spin on them.

- Be open to humor. Give yourself permission to smile or laugh, especially during difficult times. Seek humor in everyday happenings. When you can laugh at life, you feel less stressed.

- Follow a healthy lifestyle. Aim to exercise for about 30 minutes on most days of the week. You can also break it up into 5- or 10-minute chunks of time during the day. Exercise can positively affect mood and reduce stress. Follow a healthy diet to fuel your mind and body. Get enough sleep. And learn techniques to manage stress.

- Surround yourself with positive people. Make sure those in your life are positive, supportive people you can depend on to give helpful advice and feedback. Negative people may increase your stress level and make you doubt your ability to manage stress in healthy ways.

- Practice positive self-talk. Start by following one simple rule: Don't say anything to yourself that you wouldn't say to anyone else. Be gentle and encouraging with yourself. If a negative thought enters your mind, evaluate it rationally and respond with affirmations of what is good about you. Think about things you're thankful for in your life.

Here are some examples of negative self-talk and how you can apply a positive thinking twist to them:

Practicing positive thinking every day

If you tend to have a negative outlook, don't expect to become an optimist overnight. But with practice, eventually your self-talk will contain less self-criticism and more self-acceptance. You may also become less critical of the world around you.

When your state of mind is generally optimistic, you're better able to handle everyday stress in a more constructive way. That ability may contribute to the widely observed health benefits of positive thinking.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Forte AJ, et al. The impact of optimism on cancer-related and postsurgical cancer pain: A systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2021; doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.09.008.

- Rosenfeld AJ. The neuroscience of happiness and well-being. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2019;28:137.

- Kim ES, et al. Optimism and cause-specific mortality: A prospective cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2016; doi:10.1093/aje/kww182.

- Amonoo HL, et al. Is optimism a protective factor for cardiovascular disease? Current Cardiology Reports. 2021; doi:10.1007/s11886-021-01590-4.

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition. Accessed Oct. 20, 2021.

- Seaward BL. Essentials of Managing Stress. 4th ed. Burlington, Mass.: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2021.

- Seaward BL. Cognitive restructuring: Reframing. Managing Stress: Principles and Strategies for Health and Well-Being. 8th ed. Burlington, Mass.: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2018.

- Olpin M, et al. Stress Management for Life. 5th ed. Cengage Learning; 2020.

- A very happy brain

- Being assertive

- Bridge pose

- Caregiver stress

- Cat/cow pose

- Child's pose

- COVID-19 and your mental health

- Does stress make rheumatoid arthritis worse?

- Downward-facing dog

- Ease stress to reduce eczema symptoms

- Ease stress to reduce your psoriasis flares

- Forgiveness

- Job burnout

- Learn to reduce stress through mindful living

- Manage stress to improve psoriatic arthritis symptoms

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Meditation is good medicine

- Mountain pose

- New School Anxiety

- Seated spinal twist

- Standing forward bend

- Stress and high blood pressure

- Stress relief from laughter

- Stress relievers

- Support groups

- Tips for easing stress when you have Crohn's disease

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Positive thinking Stop negative self-talk to reduce stress

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Women rarely die from heart problems, right? Ask Paula.

When will patients see personalized cancer vaccines?

A molecular ‘warhead’ against disease

A Harvard study found that women who were optimistic had a significantly reduced risk of dying from several major causes of death over an eight-year period, compared with women who were less optimistic.

Credit: Estitxu Carton/Creative Commons

How power of positive thinking works

Karen Feldscher

Harvard Chan School Communications

Study looks at mechanics of optimism in reducing risk of dying prematurely

More like this.

Can happiness lead toward health?

Having an optimistic outlook on life — a general expectation that good things will happen — may help people live longer, according to a new study from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The study found that women who were optimistic had a significantly reduced risk of dying from several major causes of death — including cancer, heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease, and infection — over an eight-year period, compared with women who were less optimistic.

The study appears online today in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

“While most medical and public health efforts today focus on reducing risk factors for diseases, evidence has been mounting that enhancing psychological resilience may also make a difference,” said Eric Kim , research fellow in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences and co-lead author of the study. “Our new findings suggest that we should make efforts to boost optimism, which has been shown to be associated with healthier behaviors and healthier ways of coping with life challenges.”

The study also found that healthy behaviors only partially explain the link between optimism and reduced mortality risk. One other possibility is that higher optimism directly impacts our biological systems, Kim said.

The study analyzed data from 2004 to 2012 from 70,000 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study, a long-running study tracking women’s health via surveys every two years. They looked at participants’ levels of optimism and other factors that might play a role in how optimism may affect mortality risk, such as race, high blood pressure, diet, and physical activity.

The most optimistic women (the top quartile) had a nearly 30 percent lower risk of dying from any of the diseases analyzed in the study compared with the least optimistic (the bottom quartile), the study found. The most optimistic women had a 16 percent lower risk of dying from cancer; 38 percent lower risk of dying from heart disease; 39 percent lower risk of dying from stroke; 38 percent lower risk of dying from respiratory disease; and 52 percent lower risk of dying from infection.

While other studies have linked optimism with reduced risk of early death from cardiovascular problems, this was the first to find a link between optimism and reduced risk from other major causes.

“Previous studies have shown that optimism can be altered with relatively uncomplicated and low-cost interventions — even something as simple as having people write down and think about the best possible outcomes for various areas of their lives, such as careers or friendships,” said postdoctoral research fellow Kaitlin Hagan, co-lead author of the study. “Encouraging use of these interventions could be an innovative way to enhance health in the future.”

Other Harvard Chan School authors of the study included Professor Francine Grodstein and Associate Professor Immaculata De Vivo, both in the Department of Epidemiology, and Laura Kubzansky, Lee Kum Kee Professor of Social and Behavioral Sciences and co-director of the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness. Harvard Medical School Assistant Professor Dawn DeMeo was also a co-author.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Share this article

You might like.

New book traces how medical establishment’s sexism, focus on men over centuries continues to endanger women’s health, lives

Sooner than you may think, says researcher who recently won Sjöberg Prize for pioneering work in field

Approach attacks errant proteins at their roots

Harvard announces return to required testing

Leading researchers cite strong evidence that testing expands opportunity

Yes, it’s exciting. Just don’t look at the sun.

Lab, telescope specialist details Harvard eclipse-viewing party, offers safety tips

For all the other Willie Jacks

‘Reservation Dogs’ star Paulina Alexis offers behind-the-scenes glimpse of hit show, details value of Native representation

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 01 March 2023

The effect of positive thinking on resilience and life satisfaction of older adults: a randomized controlled trial

- Zahra Taherkhani 1 ,

- Mohammad Hossein Kaveh 2 ,

- Arash Mani 3 ,

- Leila Ghahremani 1 &

- Khadijeh Khademi 4

Scientific Reports volume 13 , Article number: 3478 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

4565 Accesses

4 Citations

223 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

The cumulative effects of adversity and unhappiness affect life satisfaction and quality of life in the growing older adult population. Most of the interventions aimed at improving the health and quality of life of older adults have adopted a problem-oriented or weakness-focused approach. However, a positive or strengths-focused approach can also have a virtuous but more effective capacity to contribute to the well-being and life satisfaction of older adults. Therefore, the present study was conducted to investigate the effect of positive thinking training on improving resilience and life satisfaction among older adults. A randomized controlled trial was conducted on 100 older adults with simple random sampling. The intervention group received 90-min weekly sessions for eight weeks on positive thinking training through written homework for reflection, group discussion, and media. The data were collected using Ingram and Wisnicki Positive Thinking Questionnaire, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, and Tobin Life Satisfaction Questionnaire at baseline and one week and two months after the training. The collected data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics in SPSS software 26. P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Positive thinking training led to better thinking ( p < 0.001), higher resilience ( p < 0.001), and greater life satisfaction ( p < 0.001). The study's findings showed the effectiveness of the positive thinking training approach in improving resilience and life satisfaction in older adults. It is recommended to evaluate the long-term outcome in populations with different social, economic, and cultural statuses in future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing

Joep van Agteren, Matthew Iasiello, … Michael Kyrios

Social support enhances the mediating effect of psychological resilience on the relationship between life satisfaction and depressive symptom severity

Yun-Hsuan Chang, Cheng-Ta Yang & Shulan Hsieh

Only vulnerable adults show change in chronic low-grade inflammation after contemplative mental training: evidence from a randomized clinical trial

Lara M. C. Puhlmann, Veronika Engert, … Tania Singer

Introduction

The older adult population is growing because of improved healthcare and education systems. These individuals encounter physical, psychological, and social adjustments that challenge their sense of self and capacity to live. Many people experience loneliness and depression episodes in old age due to living alone or lacking a close family, which results in the inability to participate in community activities 1 . The simultaneous effects of health disorders experiences and socioeconomic problems throughout life lead to life satisfaction challenges and low tolerance of problems during old age 2 . Older adults care programs have often focused on secondary care for some physical and psychological illnesses with a negative health approach. Psychological research and theory on welfare and quality of life have also focused on the influence of negative aspects 3 . In contrast to this traditional attitude, however, the past two decades have witnessed the occurrence of an alternative positive viewpoint, which originates from developmental psychology and explores the personal and environmental factors that can improve psychological happiness and quality of life, particularly during hardship or stress 4 , 5 .

New positive approaches have focused on the importance and role of individual components and skills, including resiliency, and increased emphasis on ideal or successful aging 6 . Several features of resilience, including physical, mental, and social features, have been well-known among older people 7 , 8 , 9 , representing the multi-dimensionality of this feature. High resilience during later years of life has been accompanied by ideal outcomes, such as reduced depression and anxiety, increased quality of life, and improved lifestyle behaviors 10 , 11 , 12 . In general, individual factors, such as level of education, cognitive and emotional abilities, self-care skills, beliefs, and attitudes, as well as physical-social environment factors, including family, healthcare system, social welfare, and physical environment facilities for the safe presence of older adult's individuals in the community have vital effects on their physical and mental health. In this way, these factors can affect their efficiency and life satisfaction 13 , 14 . Studies have indicated that life satisfaction and happiness do not depend solely on external conditions; individual mental states, such as hope, self-esteem, and a sense of efficiency, are also important. Individuals with a positive mental structure can evaluate many negative events positively 15 , 16 . Resilience is one of the most important determining factors of older adults’ mental health. Resilience refers to individuals’ traits and skills that empower them to thrive in the face of hardship or a disruptive event 10 , 11 . Resilient people have flexibility, high confidence, life expectancy, the ability to forgive others, purposefulness, social participation, and a positive view of life and the future that prevents anxiety and depression in older adults 17 . In addition to internal and personal factors, external and environmental factors affect resiliency 18 . Thus, resilience is not a static phenomenon. In this context, resiliency can be improved by interventions, such as positive thinking techniques, reviewing past events, having social participation, strengthening self-confidence and motivation, using a semantic approach, e.g., yoga, and reinforcing internal powers 19 , 20 .

The pattern of individual thinking is important; individuals with positive thinking can overcome problems, while negative thoughts can lead to greater problems. Therefore, people can overcome life difficulties and events by abandoning negative thoughts and replacing them with positive ones 21 , 22 . The positive approach aims to identify the structures and methods that lead to well-being, happiness, and increased life satisfaction. Therefore, using positive training techniques to increase older adult's individuals’ resilience can act as a barrier to the physical and emotional weaknesses of older adults. Studies in Iran have evaluated the impact of positive thinking on older adults' mental health, psychological well-being, life expectancy, and loneliness 23 , 24 , 25 . However, these studies have not been able to directly investigate the impact of positive thinking on the improvement of resilience in this population. In other countries, the effects of positive thinking skills on increasing the resilience level have been somewhat proven 18 , 23 , 26 . However, resilience is an individual-social process that is significantly affected by culture and religion. Even the aging phenomenon is defined differently in various societies 19 , 24 .

In Iranian society, older adults are highly respected, and there is a positive attitude toward their knowledge and experiences, which gives them a deep sense of usefulness. However, negative stereotypes about their abilities prevent them from being active in society and interfere with their creativity, liveliness, and care priorities. Accordingly, overcoming these negative stereotypes leads to a sense of empowerment, resilience, and life satisfaction. Thus, providing effective educational, emotional, cultural, and social interventions can be helpful 27 .

Hence, the results of these studies cannot be generalized to Iranian society without independent evaluations. To our knowledge, no empirical studies were found in the current research framework. Additionally, the previous studies have only considered a part of the relationships, and a few similar studies have yielded inconclusive results. Considering the transition to old age in Iranian society and considering cultural, social, religious, and economic factors that vary among communities, the present study aims to investigate the effects of positive thinking training on increasing the resilience level and life satisfaction in a population of Iranian older adults.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted with the clinical trials registration number IRCT20171212037844N1 and the registration date of 15/01/2018. In addition, all methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations. The study objectives and procedures were explained, and the participants were asked to sign the written informed consent forms.

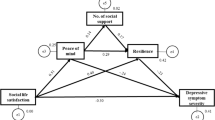

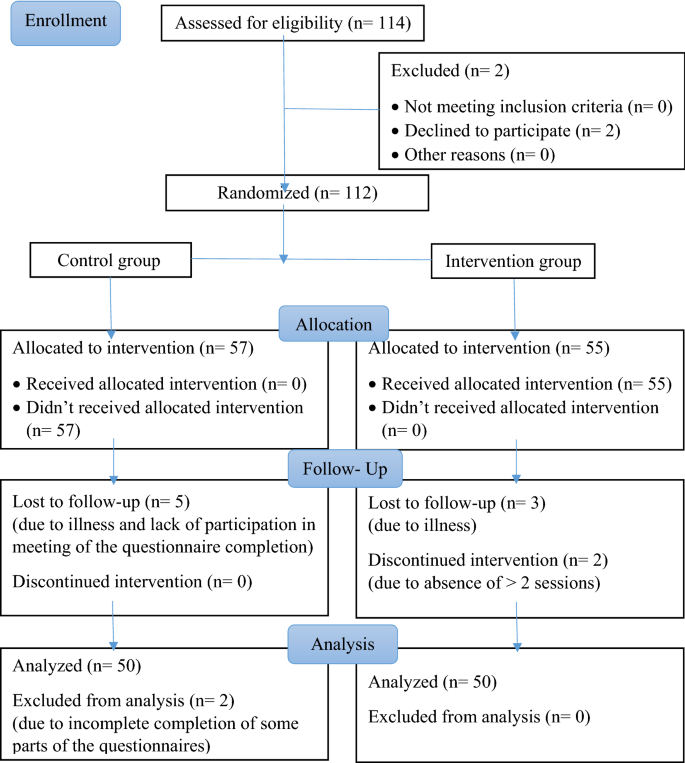

Study design and population

This educational randomized controlled trial was conducted in Shiraz, Iran, in 2018. The study population included people aged 60–70 covered by the older adult daycare centers affiliated with Welfare Organization in Shiraz. Based on a similar study 23 , using the appropriate formula with the type I error rate of 5% and the test power of 80%, considering a 10% attrition rate, the sample size was calculated as 45 participants in each group. Participants were selected in each center with the simple random sampling technique. For this purpose, the list of names of older adults covered by the center was considered the basis for sampling. The sampling interval was calculated by considering almost equal sex proportions using a randomization number between 1 and 10. The selected people were checked in terms of the inclusion criteria, and in case of ineligibility, the next person was selected from the list. All the participants had normal vision and hearing, scored ≥ 26 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and had the physical and mental ability to answer the questions. The participants had no psychiatric or neurological disorders and received no psychoactive drugs. Writing and reading literacy was another inclusion criterion. However, the exclusion criteria were being absent for more than two sessions, participating in similar training courses, and reluctance to continue participating in the study. The CONSORT diagram of the study is shown in Fig. 1 .

The CONSORT diagram of the study .

Data collection

The participants were asked to complete four questionnaires, including the Persian version of the Ingram and Wisnicki Positive Thinking Questionnaire 28 , the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 29 , the Tobin Life Satisfaction Questionnaire 30 , and a demographic information questionnaire.

The demographic data included age, sex, level of education, marital status, having children, housing situation, employment status, monthly income, and suffering from diseases.

Ingram and Wisnicki's Positive Thinking Questionnaire contained 30 items, e.g., "I have a good sense of humor"; scored using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Thus, the total score of this questionnaire ranged from 30 to 150, with an average score of 90. Total scores above 90 and closer to 150 indicate a higher degree of positive thinking. The reliability index of this questionnaire was found to be 0.92 using Cronbach’s alpha 28 , which was 0.96 in the present study.

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale included 25 items graded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (always false) to 5 (always true), with higher scores reflecting greater resilience. An example of the items in this questionnaire is "I take pride in my achievements." The reliability of the questionnaire was calculated with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 29 , which was 0.97 in the present study.

Tobin Life Satisfaction Questionnaire consisted of 13 items. Five items had negative contents, e.g ., "I have gotten more of the breaks in life than most of the people I know." The rest had positive content, e.g., "I have made plans for things I’ll be doing a month or a year from now." The statement “I do not know” was assigned two scores. In addition, positive statements received three scores for positive responses and one for negative ones. In contrast, negative statements were assigned three scores for negative responses and one for positive ones. Thus, the total life satisfaction score ranges from 13 to 39, with higher scores representing a higher level of life satisfaction. The reliability coefficient was calculated as 0.93. Cronbach’s alpha and Guttmann coefficients were found to be 0.79 and 0.78, respectively 30 . Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96 in the present study.

Baseline (Pre-test) and demographic data were collected one week before starting the training sessions. Post-intervention data were collected one week (Post-test) and two months (Follow-up) after the end of the intervention.

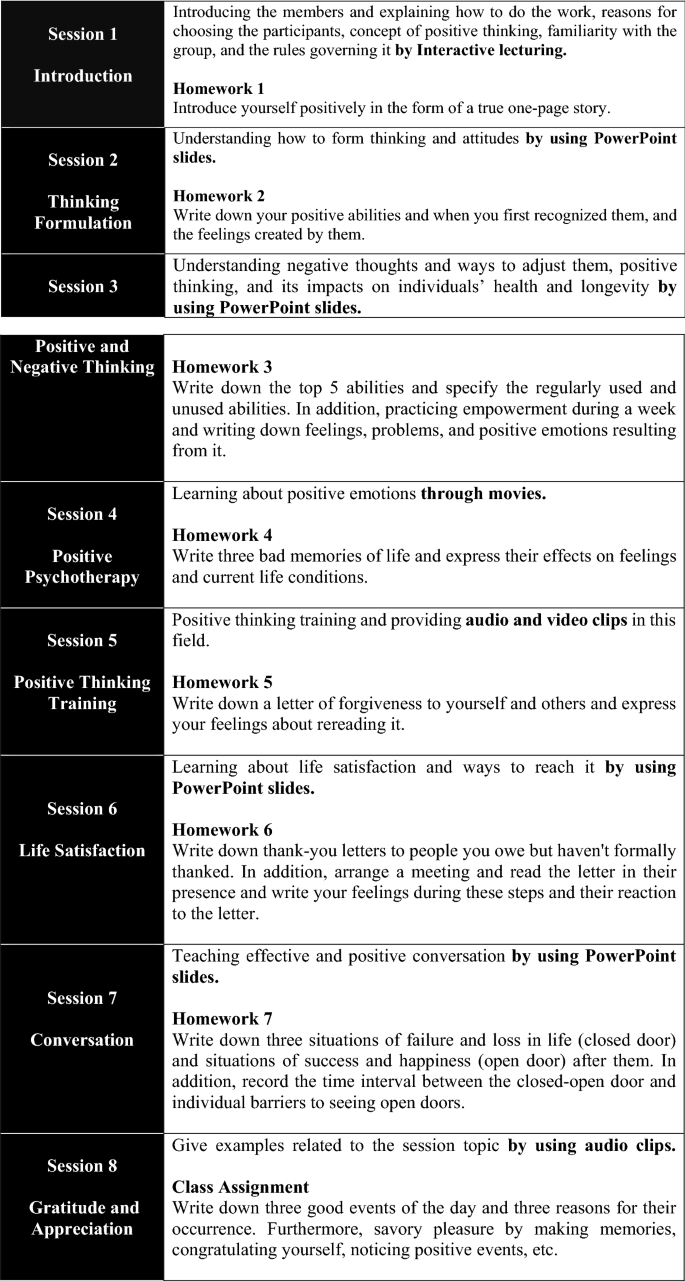

Procedure and intervention

The individuals in the intervention group participated in training sessions on positive thinking consisting of one 90-min session per week for eight consecutive weeks. The session's content was based on the theories of positive psychology 31 , 32 in the field of positive thinking, including Strengths of Character (Homework 1, 2, 3), Engagement and Flow (Homework 4, 5, 6,7), and Meaning (Class Assignment). The training was performed using teaching/learning methods, including Interactive lecturing, group discussion, and media, such as PowerPoint presentations and audio and video clips. Based on scientific evidence, writing thoughts, feelings, and experiences, especially in combination with their expression, strengthens the character, reduces distress, and improves mental health. It is important to note that group discussions are more effective in these cases 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 . Hence, at the end of each session, participants were given written homework for reflection at home to practice positive thinking; they explained and discussed it in the group at the beginning of the next session (Except session 8). It should be noted that their practical experience was introduced as a method of positive thinking. The topics, as well as the objectives of each training session, are summarized in Fig. 2 . In addition, a detailed description of the intervention program is shown in Appendix A .

The topics and objectives, and homework of each training session.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics in the SPSS software version 26 38 and G-Power 3.1.9.2 (Düsseldorf, Germany). Data normality was checked by Shapiro–Wilk test. Additionally, a chi-square test was used to analyze the demographic data. Moreover, Repeated Measures ANOVA and independent T-test were performed to compare the research constructs' means. Bayesian inference was also used to update the probability of the hypothesis as more evidence or information became available. In all statistical tests, a p value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the participants were required to complete a written informed consent form. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUMS.REC.1396.122).

The descriptive findings of this study showed no statistically significant differences in terms of the mean age (year) between the control group (M = 64.58, SD = 3.7) and the intervention group (M = 65.32, SD = 3.63); there was moderate evidence for the equal mean of age between two groups [t (98) = -0.639, p = 0.52; BF = 5.36]. The frequency distribution of other demographic data in the control and intervention groups is summarized in Table 1 .

Accordingly, there was no significant difference between the two study groups ( p > 0.05). Most participants had high school and lower degrees, were married, had children, lived in their own houses, were retired, received one-two million Tomans as their income, and suffered from at least one underlying disease. The most and least frequent diseases were cardiovascular disorders and cancer, respectively.

The results revealed anecdotal evidence for the equal mean score of positive thinking between the control and intervention groups before the intervention (BF = 1.69). However, moderate evidence for the difference was observed between the two groups in this regard 1 week after the intervention [t (98) = −2.87, p = 0.005] and in the follow-up phase [t (98) = −2.73, p = 0.007]. In the intervention group, there was very strong evidence for the mean scores difference of positive thinking in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages [F (1.05, 51.89) = 50.48, p < 0.001], and the effect of the intervention was maintained over time (Table 2 ).

The results indicated moderate evidence for the equal mean of resiliency score at the pre-test stage between the control and intervention groups (BF = 5.69). Nonetheless, extreme evidence for the difference was found between the two groups in this regard after the intervention [t (87.5) = −11.152, p < 0.001] and in the follow-up phase [t (98) = −5.81, p < 0.001]. In the intervention group, there was extreme evidence for the difference in the mean score of resiliency in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages [F (1.68, 82.61) = 77.16, p < 0.001] (Table 3 ).

Anecdotal evidence was found between the control and intervention groups regarding the equal mean of life satisfaction score in the pre-test stage (BF = 1.72). However, extreme evidence for the difference was found between the control and intervention groups in this regard after the intervention [t (98) = −4.53, p < 0.001] and in the follow-up phase [t (98) = −4.43, p < 0.001]. In the intervention group, there was strong evidence for the difference in the life satisfaction scores in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages [F (1.23, 60.71) = 69.60, p < 0.001] (Table 4 ).

The main purpose of the present study was to investigate the effect of positive thinking training on increasing resilience levels and life satisfaction in a population of Iranian older adults. Designed positive thinking interventions are very sparse, specifically those targeting older adults. Most existing projects and studies have focused on high-risk younger adults, most of which are theoretical research studies with methodological weaknesses, small populations, and no exact outcome measures, which are inaccessible or invalid for older adults. Considering the cultural and social differences amongst societies, the lack of a similar study on an Iranian population, and low scores of positive thinking, resilience, and life satisfaction among Iranian older adults based on the present study findings, it seems necessary to perform appropriate interventions. The results of this study showed that the positive-thinking intervention significantly increased the mean scores of positive thinking, resilience, and life satisfaction in the intervention group one week and two months after the intervention. Several studies have been conducted on promoting resilience through older adults’ capability to enjoy positive experiences, activities to predict future events, and tools to reinforce relationships that activate feelings of pleasure and well-being 17 . Similarly, Ruiz-Rodríguez et al. conducted an interventional study and reported a significant relationship between social support, positive thinking, and social relationships with the degree of resilience 39 . Lysne PE et al. reported a significant positive correlation between resilience and different dimensions of health and life satisfaction 40 . Resiliency leads to life satisfaction through improving mental health and indirectly affects life satisfaction. In other words, resilience leads to a positive attitude and life satisfaction by affecting individual feelings and excitement 41 . The current study's clear and practical results can be implemented as training programs for many similar aging centers. However, this study had several limitations, including limited follow-up for only two months, selection of the study groups from older adult centers, and non-generalizability of some findings, such as resilience due to ethnic and cultural differences.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the current study findings revealed a relationship between resilience and positive thinking. Positive thinking and interventions can increase older adults’ resilience, and thereby improve their quality of life. High quality of life can lead to greater life satisfaction. In addition, positive psychological training can directly contribute to positive and healthy thinking, ultimately leading to a better dynamic life for older adults.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Mini-Mental State Examination

Gründahl, M. et al. Construction and validation of a scale to measure loneliness and isolation during social distancing and its effect on mental health. Front. Psychiatry 13 , 798596. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.798596 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Donovan, N. J. & Blazer, D. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Review and commentary of a national academies report. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28 (12), 1233–1244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005 (2020).

Wang, B. & Xu, L. Construction of the “internet plus” community smart elderly care service platform. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021 , 4310648. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4310648 (2021).

Bar-Tur, L. Fostering well-being in the elderly: Translating theories on positive aging to practical approaches. Front. Med. Lausanne 8 , 517226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.517226 (2021).

Trudel-Fitzgerald, C. et al. Psychological well-being as part of the public health debate? Insight into dimensions, interventions, and policy. BMC Public Health 19 (1), 1712. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8029-x (2019).

Urtamo, A., Jyväkorpi, S. K. & Strandberg, T. E. Definitions of successful ageing: A brief review of a multidimensional concept. Acta Biomed. 90 (2), 359–363. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v90i2.8376 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Galvez-Hernandez, P., González-de Paz, L. & Muntaner, C. Primary care-based interventions addressing social isolation and loneliness in older people: A scoping review. BMJ Open 12 (2), e057729. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057729 (2022).

Veldema, J. & Jansen, P. The relationship among cognition, psychological well-being, physical activity and demographic data in people over 80 years of age. Exp. Aging Res. 45 (5), 400–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361073X.2019.1664459 (2019).

Malone, J. & Dadswell, A. The role of religion, spirituality and/or belief in positive ageing for older adults. Geriatrics (Basel). 3 (2), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3020028 (2018).

Gijzel, S. M. W. et al. Resilience in clinical care: Getting a grip on the recovery potential of older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67 (12), 2650–2657. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16149 (2019).

Chan, S. M. et al. Resilience and coping strategies of older adults in Hong Kong during COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods study. BMC Geriatr. 22 (1), 299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03009-3 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nedjat, S. et al. Life satisfaction as the main factor behind the elderly`s health knowledge utilization: A qualitative study in an Iranian context. Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran 32 , 115. https://doi.org/10.1419/mjiri.32.115 (2018).

Luo, Y., Wu, X., Liao, L., Zou, H. & Zhang, L. Children’s filial piety changes life satisfaction of the left-behind elderly in rural areas in China?. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (8), 4658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084658 (2022).

Wang, L., Yang, L., Di, X. & Dai, X. Family support, multidimensional health, and living satisfaction among the elderly: A case from Shaanxi Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (22), 8434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228434 (2020).

Wu, C. et al. Association of frailty with recovery from disability among community-dwelling older adults: Results from two large U.S. cohorts. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 74 (4), 575–581. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly080 (2019).

Zaidel, C., Musich, S., Karl, J., Kraemer, S. & Yeh, C. S. Psychosocial factors associated with sleep quality and duration among older adults with chronic pain. Popul. Health Manag. 24 (1), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2019.0165 (2021).

Hiebel, N. et al. Resilience in adult health science revisited-A narrative review synthesis of process-oriented approaches. Front. Psychol. 12 , 659395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.659395 (2021).

Kunzler, A. M. et al. Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 7 (7), 12527. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012527.pub2 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Zapater-Fajarí, M., Crespo-Sanmiguel, I., Pulopulos, M. M., Hidalgo, V. & Salvador, A. Resilience and psychobiological response to stress in older people: The mediating role of coping strategies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13 , 632141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.632141 (2021).

Tanner, J. J. et al. Resilience, pain, and the brain: Relationships differ by sociodemographics. J. Neurosci. Res. 99 (5), 1207–1235. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24790 (2021).

Andrade, G. The ethics of positive thinking in healthcare. J. Med. Ethics Hist. Med. 12 , 18. https://doi.org/10.18502/jmehm.v12i18.2148 (2019).

Yue, Z. et al. Optimism and survival: Health behaviors as a mediator-a ten-year follow-up study of Chinese elderly people. BMC Public Health 22 (1), 670. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13090-3 (2022).

Safari, S. & Akbari, B. The effectiveness of positive thinking training on psychological well-being and quality of life in the elderly. Avicenna J. Neuro Psycho Physiol. 5 (3), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.32598/ajnpp.5.3.113 (2018).

Makaremnia, S., Dehghan Manshadi, M. & Khademian, Z. Effects of a positive thinking program on hope and sleep quality in Iranian patients with thalassemia: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Psychol. 9 (1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00547-0 (2021).

Maier, K., Konaszewski, K., Skalski, S. B., Büssing, A. & Surzykiewicz, J. Spiritual needs, religious coping and mental well-being: A cross-sectional study among migrants and refugees in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 (6), 3415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063415 (2022).

Bartholomaeus, J. D., Van Agteren, J. E. M., Iasiello, M. P., Jarden, A. & Kelly, D. Positive aging: The impact of a community well-being and resilience program. Clin. Gerontol. 42 (4), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1561582 (2019).

Javadi Pashaki, N., Mohammadi, F., Jafaraghaee, F. & Mehrdad, N. Factors influencing the successful aging of iranian old adult women. Iran Red Crescent Med. J. 17 (7), e22451. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.22451v2 (2015).

Safarzadeh, S., Ghasemi Safarabad, M. & Dehghanpour, M. The Relationship between positive automatic thoughts, feeling socially competent and perception of clinical decision-making with happiness among khuzestan military hospitals nurses. Military Psychol. 11 (41), 51–61 (2020).

Google Scholar

Derakhshanrad, S., Piven, E., Rassafiani, M., Hosseini, S. & Mohammadi, S. F. Standardization of connor-davidson resilience scale in Iranian subjects with cerebrovascular accident. J. Rehabilitation Sci. Res. 1 (4), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.3047/jrsr.2014.41059 (2014).

Tagharrobi, Z., Tagharrobi, L., Sharifi, K. H. & Sooki, Z. Psychometric Evaluation of the life satisfaction index-Z (Lsi-Z) in an iranian elderly sample. Payesh 10 (1), 5–13 (2011).

Seligman, M. E. P., Rashid, T. & Parks, A. C. Positive psychotherapy. Am. Psychol. 61 (8), 774–788. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.774 (2006).

Duncan, A. R., Jaini, P. A. & Hellman, C. M. Positive psychology and hope as lifestyle medicine modalities in the therapeutic encounter: A narrative review. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 15 (1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827620908255 (2020).

Ruini, C. & Mortara, C. C. Writing technique across psychotherapies-from traditional expressive writing to new positive psychology interventions: A narrative review. J. Contemp. Psychother. 52 (1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-021-09520-9 (2022).

Vanaken, L., Bijttebier, P. & Hermans, D. An investigation of the coherence of oral narratives: Associations with mental health, social support and the coherence of written narratives. Front. Psychol. 11 , 602725. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.602725 (2021).

Ching-Teng, Y., Chia-Ju, L. & Hsiu-Yueh, L. Effects of structured group reminiscence therapy on the life satisfaction of institutionalized older adults in Taiwan. Soc. Work Health Care 57 (8), 674–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2018.1475439 (2018).

Liu, Z., Yang, F., Lou, Y., Zhou, W. & Tong, F. The effectiveness of reminiscence therapy on alleviating depressive symptoms in older adults: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 12 , 709853. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.709853 (2021).

Yen, H. Y. & Lin, L. J. A systematic review of reminiscence therapy for older adults in Taiwan. J. Nurs. Res. 26 (2), 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000233 (2018).

Article ADS MathSciNet PubMed Google Scholar

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Released 2019; Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Available at: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-26?mhsrc=ibmsearch_a&mhq=SPSS%2026

Ruiz-Rodríguez, I., Hombrados-Mendieta, I., Melguizo-Garín, A. & Martos-Méndez, M. J. The importance of social support, optimism and resilience on the quality of life of cancer patients. Front. Psychol. 13 , 833176. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.833176 (2022).

Lysne, P. E. et al. Adaptability and resilience in aging adults (ARIAA): Protocol for a pilot and feasibility study in chronic low back pain. Pilot Feasibil. Stud. 7 (1), 188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-021-00923-y (2021).

Kim, E. S. et al. Resilient aging: Psychological well-being and social well-being as targets for the promotion of healthy aging. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 7 , 23337214211002950. https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214211002951 (2021).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Shiraz university of medical sciences.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Promotion, School of Health, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Zahra Taherkhani & Leila Ghahremani

Department of Health Promotion, School of Health, Institute of Health, Research Center for Health Sciences, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, 71536-755, Iran

Mohammad Hossein Kaveh

Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Institute of Health, Research Center for Health Sciences, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Student Research Committee, Department of Health Promotion, School of Health, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Khadijeh Khademi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.H.K. supervised and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Z.T. collected the data and drafted the original manuscript; K.H. K.H. analyzed the data, edited and revised the manuscript; A.M and L. G.H. were the advisors and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mohammad Hossein Kaveh .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.