- Open access

- Published: 20 April 2022

Does microfinance foster the development of its clients? A bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review

- João Paulo Coelho Ribeiro 1 ,

- Fábio Duarte ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4919-0736 2 &

- Ana Paula Matias Gama 3

Financial Innovation volume 8 , Article number: 34 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

13 Citations

Metrics details

This paper conducts a scientometric analysis and systematic literature review to identify the trends in microfinance outcomes from the perspective of their recipients, specifically more vulnerable people, while also focusing on the demand side. Applying the keywords “co-occurrence networks” and “citation networks,” we examined 524 studies indexed on the ISI Web of Science database between 2012 and March 2021. The subsequent content analysis of bibliometric-coupled articles concerns the main research topics in this field: the socioeconomic outcomes of microfinance, the dichotomy between social performance and the mission drift of microfinance institutions, and how entrepreneurship and financial innovation, specifically through crowdfunding, mitigate poverty and empower the more vulnerable. The findings reinforce the idea that microfinance constitutes a distinct field of development thinking, and indicate that a more holistic approach should be adopted to boost microfinance outcomes through a better understanding of their beneficiaries. The trends in this field will help policymakers, regulators, and academics to examine the nuts and bolts of microfinance and identify the most relevant areas of intervention.

This study conducts a scientometric analysis and systematic literature review to identify the trends in microfinance outcomes from the perspective of their recipients

A Bibliometric analysis were conducted to examine 524 studies indexed on the ISI Web of Science database between 2012 and March 2021

A content analysis of 11 ABS ranked articles (rank 4 or 4*) were conducted to stablish trends of research

The findings suggest that a holistic approach should be adopted to boost microfinance outcomes through a better understanding of their beneficiaries

Introduction

Microcredit has emerged as an innovative tool for fighting poverty in underdeveloped countries (Mustafa et al. 2018 ). Positive experiences suggest that it constitutes an agile, flexible, and cost-effective financial instrument for entrepreneurship projects that otherwise suffer from bank credit rationing (Stiglitz 1990 ). Combining microcredit, microsavings, and microinsurance, microfinance “can help low-income people reduce risk, improve management, raise productivity, obtain higher returns on investments, increase their incomes, and improve the quality of their lives and those of their dependents” (Robinson 2001 : 9).

The promise of microcredit to eradicate global poverty has proven overly ambitious, as poverty results from a wide number of factors. Nevertheless, at least theoretically, providing poor people with financial resources to start their own businesses can help them increase their income and purchasing power, even if starting and running a successful business is not a simple task. Furthermore, if microcredit loans do not create financial wealth, they should then be classified simply as a “mechanism for transferring resources to the poor” (Khandker 1998 : 7).

The implementation of microfinance and its potential as a tool for fighting social and financial asymmetries is an expanding research topic. However, while microfinance may have grown into a worldwide industry, scholars have expressed doubt about its actual impact on the recipients (e.g., Morduch 1999 ). The lack of true profit-generating potential of financed ventures (Bradley et al. 2012 ), high interest rates (Webb et al. 2013 ), and the lack of management and entrepreneurial skills (Evers and Mehmet 1994 ) raise substantial doubts about the outcomes of microfinance for recipients. Furthermore, the current empirical literature casts doubt on the ability of microfinance to generate multidimensional outcomes such as empowerment, education, health, and nutrition (Khavul et al. 2013 ; Miller et al. 2012 ). Therefore, this study seeks to examine the trends in the outcomes of microfinance for its clients, particularly for more vulnerable people (e.g., women, self-employed, older adults, low-income, and refugees), by focusing on the demand dimension of microfinance. To present the prevailing state of research on microfinance and its benefits for clients, we apply a scientometric analysis, which enables us to trace the anatomy and analyze the knowledge of this research topic. Thus, we address three research goals: identifying the current trends in the outputs of the microfinance literature in terms of dates, journals, authors, affiliated countries, and institutions; examining the most influential studies and themes in this field; and discussing the intellectual structures of the outcomes of microfinance research and the underlying trends.

This approach identified five clusters using keyword analysis and knowledge maps: (1) the socioeconomic outcomes of microfinance, (2) the conflict between social performance and the mission drift of microfinance institutions; (3) group lending, social networks, and social capital; (4) poverty alleviation through entrepreneurial activities and the impact of innovative services, especially crowdfunding; and (5) gender and new thematic frontiers.

Muhammad Yunus argues that poor people possess natural abilities to run businesses, and that their own subsistence reflects the capacities of their survival skills (Yunus 1998 ). However, to set up new businesses, poor entrepreneurs need to find alternative financial resources due to their general exclusion from the traditional banking system because of their lack of collateral (Stiglitz 1990 ), limited property rights (Webb et al. 2013 ), and the high transaction costs incurred by small-scale bank loans (Chliova et al. 2015 ; Ghatak 1999 ; Weiss and Montgomery 2005 ). Ongoing and established relations between lenders and borrowers often generate trust and reduce the risk of credit rationing (Stiglitz 1990 ); however, this inherently does not apply to most potential microcredit beneficiaries, as they lack any credit history (Tang et al. 2017 , 2018 ). Hence, Yunus ( 1994 ) identifies the provision of credit as a key factor for overcoming poverty through innovative approaches to providing credit to the poor as encapsulating a potential solution. Therefore, as microfinance-related articles have been published, literature reviews have appeared on several microfinance-related themes. Table 1 summarizes these studies.

Brau and Woller ( 2004 ) surveyed 350 articles related to microfinance institutions (MFIs) sustainability, products and services, management practices, client targeting, regulations and policies, and impact assessment before calling for further research into microfinance practices as a means of combatting poverty around the world. Based on 71 research papers (peer-reviewed journals, university publications, reports by development organizations, and conference publications) on the performance of MFIs, Roy and Goswami ( 2013 ) propose that microfinance researchers, practitioners, and rating agencies consider other dimensions for assessing MFI performance besides the financial aspect, particularly considering measures for social performance, outreach, and sustainability. García-Pérez et al. ( 2017 ) carried out a systematic literature review of 475 articles on microfinance, resulting in their classification of sustainability research under four perspectives: economic, environmental, social, and governance. They report that the economic and social fields have received the most attention, with authors having researched the interrelationships and considered a broader variety of subjects in those areas than in the environmental or governance fields. Fall et al. ( 2018 ) performed a meta-regression analysis of the performance of 38 MFIs before demonstrating that the mean technical efficiency (MTE) of MFIs has increased over time. However, research estimating social efficiency generated lower MTE levels than that for financial efficiency, which may explain why the African microfinance sector has poor performance. Hermes and Hudon ( 2018 ) also studied MFIs while focusing on the determinants of social and financial performance. From a study including 169 articles, they concluded that the most important determinants of MFI performance addressed by the literature are their own respective characteristics (such as the size, age, and type of organization), their funding sources, the quality of their corporate governance policies, and the characteristics of their external environment (such as the prevailing macroeconomic, institutional, and political conditions). However, they report mixed empirical findings, which may stem from a multidimensional perspective of performance. They suggest that outreach, gender, and rural measures should be adopted to measure the social performance of MFIs more holistically. Akter et al. ( 2021 ) have also recently addressed this dual nature of MFI performance (i.e., spanning the financial and social dimensions). After applying bibliometric data to 1252 Scopus-indexed articles, the authors convey how the hot topic research themes related to microfinance cover poverty alleviation, group lending, and credit scoring, whereas the financial performance aspect has been gaining greater attention from recent research evaluating MFI performance.

Copestake et al. ( 2016 : 290) review three decades of microfinance doctoral research, referring to this as a “distinct field of development thinking,” describing the “mainstream narrative of progressive inclusion of poor people and their livelihoods into a globally integrated and regulated financial system, largely in the private sector but also strategically subsidised by government and aid agencies.” The authors identify a critical counterpoint to this narrative of development thinking by emphasizing the specific negative effects of financial integration on poverty and inequality. By compiling a series of studies, they suggest that the performance of microfinance depends on socio-cultural norms, regulation, and management practices, which might further explain the mixed empirical evidence on the impact of microfinance.

Deploying a scientometric analysis of 1874 papers on microfinance, Gutiérrez-Nieto and Serrano-Cinca ( 2019 ) focus on the most cited 5% in this pool and classify the resulting 94 papers as institutionalist (when more oriented toward MFIs), welfarist (when more oriented toward microfinance clients), and generalist (otherwise). Based on chronological analysis, these authors report that, having previously covered innovations in microcredit practices and their impacts (the first research stage), as well as the peculiarities of MFI (second stage), current research primarily targets certain concerns over MFI mission drift and the role of microfinance in fostering financial inclusion. Somewhat interrelated with Gutiérrez-Nieto and Serrano-Cinca ( 2019 ), Zaby ( 2019 ) sets out an overall picture of the state of the art in the microfinance literature coupled with the main schools of thought. This author adopts science mapping to examine 4,409 Scopus-index articles explicitly related to microfinance (Zaby 2019 : 1), and correspondingly identifies three thematic research clusters: (1) the institutional aspects of microfinance, (2) the application of sophisticated research methods to evaluate the impacts of microfinance, and (3) ground-breaking microfinance literature related more generally to social justice. Nogueira et al. ( 2020 ) also report how MFI performance-related issues represent one of the most commonly approached fields of research. Based on 2168 articles indexed in the Web of Science, these authors point out how financial inclusion and entrepreneurship are hot topics related to microfinance. The authors then conclude in favor of the relevance of studying entrepreneurship in order to better understand the beneficiaries of microfinance.

Duvendack et al. ( 2011 : 2) argue that “no study robustly shows any strong impact of microfinance” on the well-being of its beneficiaries. After analyzing 58 papers, these authors identified cases with both poor methodology and data and concluded that most studies advanced no reliable evidence regarding the impact of microfinance. Van Rooyen et al. ( 2012 ) also focus on the impact of microfinance on poor people in their systematic review of studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa. They report that microfinance has a modestly positive impact, but also occasionally results in the deterioration of the situations faced by beneficiaries. This framework indicates that academics and practitioners should closely consider the beneficiaries of microfinance rather than the overall performance of MFIs. This research gap prevents us from reaching any conclusions about the value of microfinance, particularly microcredit, as a tool for mitigating poverty and financial and social exclusion, nor regarding whether their multidimensional outcomes extend beyond the creation of wealth.

Only a few studies have hitherto focused on the impact of microfinance on the poor and on their well-being (e.g., Duvendack et al. 2011 ; Van Rooyen et al. 2012 ). This gap led us to combine bibliometric and content analysis to compile current literature and provide a roadmap of trends for future research into the outcomes of microfinance for recipients with a particular demand-side focus.

Therefore, this study makes several contributions to the literature. In particular, the results of the knowledge maps convey how more traditional topics, such as the focus of microfinance institutions, may potentially shift gradually over time and with the move from social to financial performance, increasing the risk of mission drift, and the advantages of group lending for creating social networks to overcome access to capital-related problems still attracts research interest. Furthermore, emerging trends relate to strategies for overcoming poverty and enhancing socioeconomic development. Entrepreneurship is a powerful tool that strengthens the financial and non-financial outcomes of microfinance. In addition, the scope of microfinance outreach is changing due to the emergence of crowdfunding platforms, particularly prosocial platforms (e.g., KIVA: https://www.kiva.org/ ) that boost women empowerment and gender equalities, stimulating the liberalization of financial systems at a global level and potentially prompting a more financially and socially inclusive system.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Sect. 2 sets out the research methodology design, and Sect. 6 details the bibliometric analysis that systematizes the publication trends, the most prolific journals, authors, and affiliated institutions, as well as the most influential studies and subjects in the field. Section 12 provides the content analysis based on bibliometric coupling, and Sect. 18 outlines and discusses the new trends in the microfinance literature, before Sect. 23 presents our conclusions.

Research methodology

Data and research criteria.

This study applies bibliometric and content analytical procedures to the selected papers, focusing on the outcomes of microfinance for their recipients (demand side), based on information collected from the Web of Science (WoS), Footnote 1 a database that “contains thousands of academic publications along with bibliographic information on their authors, affiliations, and citations” (Ferreira et al. 2019 : 186). We limited our research to articles published after 2011, as that was the last year with systematic literature reviews of this field, following the studies by Duvendack et al. ( 2011 ) and Van Rooyen et al. ( 2012 ; see Table 1 ). Our search of the field adopted the keywords (“microfinance*” OR “micro finance” OR “micro-finance*” OR “microcredit*” OR “micro credit*” OR “micro-credit*”) AND NOT (“microbank*” OR “micro bank*” OR “micro-bank*” OR “microfinance institution*” OR “micro finance institution*” OR “micro-finance institution*” OR “mfi*”) AND (“performance*” OR “success*” OR “outreach*” OR “impact*” OR “impacts*”) as entered in the WoS database. We then screened the articles based on titles, keywords, and abstracts to establish a database of 796 articles with the data collected in April 2021 spanning the period between 01:2012 and 03:2021. Footnote 2 Table 2 provides a comprehensive summary of the criteria used to collect the WoS data.

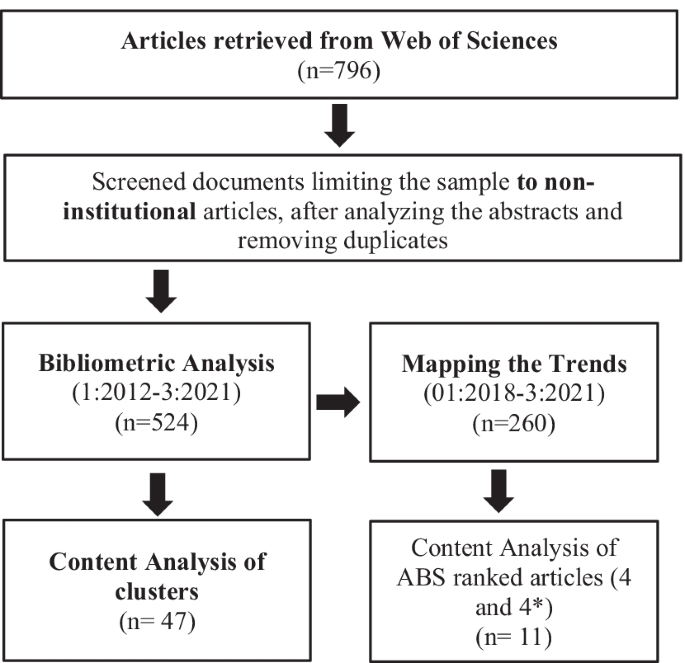

In accordance with our objective of analyzing the literature on the outcomes of microfinance for recipients, the more vulnerable people (demand side), we carried out a screening process of these documents involving the reading of the abstracts and, in case of doubt, we examined the documents in full length, which led to the exclusion of 272 purely institutional articles, that is, those concentrating solely on the financial performance of MFIs (e.g., Gutiérrez-Nieto and Serrano-Cinca, 2019 ). Nevertheless, this screening process did not exclude studies focusing on the social performance of MFIs, as these usually reach out to women, rural, vulnerable, and marginalized populations. This process was undertaken independently by two of the authors before verification by the third author. Thus, the bibliometric analysis examined 524 articles with detailed content analysis and then applied more detailed analysis to 47 of them in keeping with their common linkage to other documents in the network, based on the bibliometric coupling methodology. Furthermore, we undertook an additional context analysis of the most recent articles published between January 2018 and March 2021, ranked by the Association of Business Schools (ABS). This analysis concentrated on 11 articles published in elite journals (ABS 4*) and top journals (ABS 4). These journals generally publish the greatest advances in their respective fields and generate the highest citation impact factors within their field of knowledge. Figure 1 provides a comprehensive summary of the data analysis process.

Data retrieval process

Therefore, this study combines bibliometric analysis and a systematic literature review. Based on quantitative literature analysis, bibliometrics represents a study method from the library and information sciences (Huang and Ho 2011 ) and, according to Sengupta ( 1992 : 76), “is a sort of measuring technique by which interconnected aspects of written communications can be qualified.” Narin et al. ( 1994 : 65) refer to “bibliometrics and, in particular, evaluative bibliometrics,” which “uses counts of publications, patents, and citations to develop science and technology performance indicators.” This type of analysis emerged in order to deal with constantly growing bodies of knowledge and incorporates three major dimensions: measuring a particular scientific activity, its impacts as conveyed by the total number of article citations, and the links among articles (Narin et al. 1994 ), thus tracing the anatomy of the knowledge existing in a research field with regard to a specific topic.

Our study applied VOSviewer Footnote 3 software version 1.6.8 to analyze the publishing trends and most prolific journals, disciplines, authors, institutions, countries, studies, and subjects. This analysis is mainly derived from the number of published articles, total citations, and occurrences. To complement the analysis of the most influential studies, we performed co-citation analysis to systematize the most fundamental articles published between 1:2012 and 3:2021. Introduced by Small ( 1973 ) and developed by White and Griffith ( 1981 ) and White and McCain ( 1998 ), co-citation analysis is one of the most common bibliometric methods for unveiling similarities among the cited articles (Small 1973 ). By applying this tool via VOSviewer, we were able to highlight the main studies guiding the research over the last decade. The fractional counting methodology was used to analyze the most influential subjects, correcting the number of occurrences of each keyword in accordance with the total number of (key)words used in the title, abstract, or keyword list for the same article (Xu et al. 2018 ). The fractional counting method is more suitable than the full counting method (Narin et al. 1994 ): “When full counting is used to construct a bibliometric network, each link resulting from an action has a full weight of one, which means that the overall weight of an action is equal to the number of links resulting from the action. On the other hand, when fractional counting is used, each link has a fractional weight such that the overall weight of an action equals one” (Perianes-Rodriguez et al. 2016 : 1180). In so doing, the relationship between two keywords becomes closer when articles provide fewer keywords. Thus, Van Eck and Waltman ( 2014 ) recommend the fractional counting method, as this overcomes the potential for bias created by highly cited articles with long reference lists or more keywords, leading to misinterpretations.

Following the bibliometric analysis, we performed a systematic literature review to systematize the state of the art and to determine trends and possible research gaps based on the content analysis of clusters. Detailed content analysis was performed in the cases of bibliographically coupled articles—articles sharing a common link to other documents in the network. Bibliographic coupling establishes relationships between articles based on citation similarities and deems two articles to be bibliographically coupled whenever there is a third article cited by both these articles (Kessler 1963 ). Based on a dataset of 524 articles, we deployed VOSviewer to generate bibliometric maps based on the visualization of similarities technique. Of the 524 published articles in our refined dataset, this software reports that only 47 articles were coupled by the same item of reference, with at least 25 citations.

- Bibliometric analysis

Annual publication trends

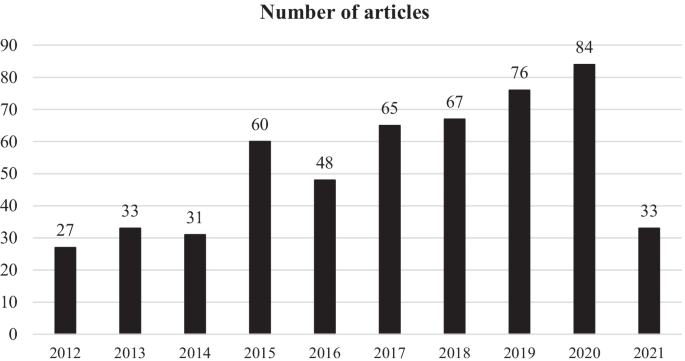

Figure 2 illustrates the trends displayed by the 524 WoS-indexed articles in the field of microfinance outcomes (i.e., demand side) since 2012.

Publication trend of 524 published articles, indexed to WoS, between 1:2012 and 3:2021

The figure indicates an upsurge in publications from 27 papers in 2012 to 84 in 2020. Footnote 4 This trend in publications stems from the increasing number of scholars challenging the proposed benefits of microcredit as a salient tool for addressing credit constraints and poverty (e.g., Angelucci et al. 2015 ; Banerjee et al. 2015a ; Bocher et al. 2017 ; Tarozzi et al. 2015 ), especially when based on entrepreneurial activities (e.g., Alvarez and Barney 2014 ). The Nobel Prize awarded to Banarjee, Duflo, and Kremer in 2019 for their work on different strategies to mitigate poverty also justifies the rise in research related to the ability of microfinance/microcredit to generate positive outcomes, such as empowerment and education, beyond mere wealth creation.

Prolific journals and subjects

Table 3 depicts the list of the most prominent journals publishing on issues related to the demand side of microfinance, and hence the microfinance recipients. A total of 252 journals were included in the 524 articles analyzed. The most prolific journals (two of them ex aequo with nine published articles, three with six published articles, and five with five published articles) have published 179 of the articles studied (34.2% of the total). Almost all of these 179 articles appear in ABS-ranked journals, mainly in ABS 3 (according to the ranking published in 2018) by the Chartered Association of Business Schools. Footnote 5 These findings illustrate how research on the microfinance field primarily engages quality journals of business and management. The Journal of Development Studies represents the most productive journal, having published 31 articles, followed closely by World Development with 30 articles. Together, both journals published 11.4% of the articles analyzed.

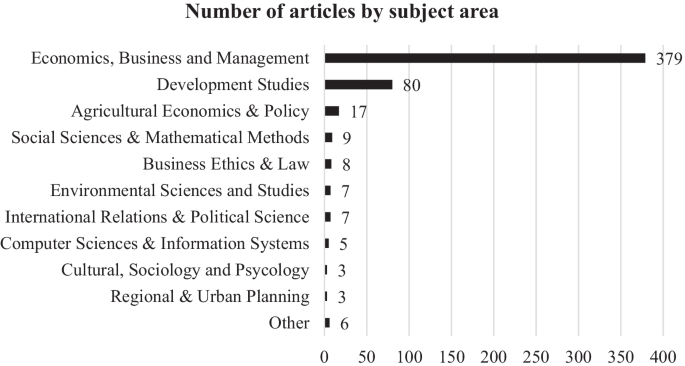

Figure 3 displays the 10 main fields of journals publishing microfinance research since 2012. The most representative areas are economics , business , and management (which includes business finance), with 379 articles (i.e., 72.32% of the total articles). This figure indicates how the analysis of the outcomes of microfinance (on the demand side) has especially adopted an economic perspective. Despite the prominent position of Development Studies in publishing research on this topic (80 articles), the journal still only represented 15.27% of the total articles. The relevance of microcredit for society as a whole remains only a marginal issue and is scarcely addressed in the literature. More studies from the fields of health, business ethics, sociology, and psychology would be worthwhile to generate a better understanding of the effectiveness of microfinance in promoting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the United Nations 2030 Agenda, specifically eradicating poverty (SDG 1), promoting health and well-being (SDG 3), gender equality (SDG 5), and reducing inequalities (SDG 10), in addition to the economic objective of decent work and growth (SDG8).

Top 10 subject areas in microfinance (demand side) research in the 524 published articles, indexed to WoS between 1:2012 and 3:2021

Prolific authors, affiliated institutions, and countries

Tables 4 and 5 display the top 10 authors, institutions, and countries publishing on microfinance (demand side) outcomes since 2012 in WoS-indexed journals by number of publications and citations. Abdullah Al Mamum provides the list detailed in Table 4 , with nine published articles. His research mainly targets the effectiveness of microcredit and training programs to combat poverty and promote the sustainable growth of micro-enterprises in rural areas in Malaysia. However, Ester Duflo stands out as the most prolific author based on total citations—412 citations (Table 5 ) with three published articles. Ester Duflo and her research team, Michael Kremer and Abhijit Banarjee, won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2019 for research on fighting global poverty over the preceding two decades, contributing to transforming development economics into a flourishing field of research. In the field of microfinance, Duflo conducted experimental research in less developed countries to evaluate the impact of training programs on microfinance outreach, especially on health and empowering women. Dean Karlan emerged as the second most prolific author based on both the total number of published articles (Table 4 ) and the total number of citations (Table 5 ), with six published articles (equal to Ariana Szafarz) and 381 citations, 32 more than Johnathan Zinman, with four articles published with Karlan. The expansion of microcredit, the use of loans, and repayment incentives constitute the main topics in the experimental research undertaken by Dean Karlan and Johnathan Zinman. Erica Field and Rohini Pande attained three publications with a total of 179 citations. Based on randomized experiments in India, these authors have been working on the default risk of microborrowers and the repayment requirements that best suit the needs of the poor. Ariana Szafarz represents one of the six authors with over 100 citations divided across six published articles, mainly approaching the topics of social and financial performance, gender, and empowerment. This evidence suggests that, despite the prevalence of articles from the fields of economics, business, and management (as pointed out in Fig. 3 ), the most prolific authors focus on topics within the scope of development studies. Experimental researchers seem to capture the enthusiasm of their target communities, mainly in less developed countries such as Bangladesh, India, Morocco, and Malaysia.

The institution with the most articles published on this aspect of microfinance (Table 4 ) is the University of Groningen (Netherlands) with 11 published articles, followed by the World Bank (United States) with 10, and MIT (United States) and Yale University (United States) with 9 each. MIT is the most prolific institution, based on total citations (968 citations). Yale University and Harvard University (United States) are among the top three with 440 and 300 total citations, respectively. Together, the articles published by members of these institutions received 1,708 citations, accounting for over 57% of the total citations generated by our dataset of WoS-indexed articles. The most prolific institutions all have locations in the United States and are responsible for the highest number of published articles (145) and total citations (2,990).

Citation analysis

Citation analysis is the best method for mapping the influence of a research paper. Citation counts encompass the number of citations that a paper received over a period of time. Thus, a more influential and productive paper is cited most frequently. We use VOSviewer to determine the most influential papers on microfinance outcomes. Table 6 displays the 10 most cited articles locally and globally. The local citations reflect the number of times a paper is cited by others within a sample size of 524 papers, whereas global citations measure the number of times a paper is cited by other works across all databases, including other areas and research fields.

According to global citations (local citations), Banerjee et al. ( 2015b ) are at the top of the list with 295(72) citations, followed by Banerjee et al. ( 2015a ) and Bruton et al. ( 2013 ) with 226(53) and 157(8) citations, respectively. Banerjee et al. ( 2015a , b ) are the most prominent papers paving the way for further research on microfinance outcomes. These studies provide theoretical support for the use of a randomized experimental methodology to measure the causal effects of microcredit on community development, namely on the livelihood of microentrepreneurs.

The number of citations reflects the popularity of a paper. To measure this prestige, we use the total link strength based on the fractional counting method, which indicates the number of times a paper is cited by highly cited papers. Thus, a highly cited paper could not also be a prestige paper. The total link strength is a composite measure that encompasses both popularity and prestige. Table 7 lists the top 15 papers based on the total link strength. The results differed from those of the citation count. When the top 10 papers were compared based on citations (global and local) with the total link strength (co-citations), only 5 papers (Angelucci et al. 2015 ; Attanasio et al. 2015 ; Banerjee et al. 2015a , b ; Crépon et al. 2015 ) are among the top 15 papers based on total strength links (co-citations). Co-citation refers to the number of times two articles are co-cited by an article in the database. The more often articles are co-cited, the greater the link strength (i.e., the more similar the domains under study).

Table 7 shows the studies that mostly guide the research in the last decade, which includes several articles published before 2012. Pitt and Khandker ( 1998 ), with the highest number of co-citations(total link strength) 76(546), is the most influential study in the recent literature. This study provides an evaluation of the group lending program of the Grameen Bank (and similar ones) in Bangladesh, showing that these programs have a significant effect on the well-being of poor households; their effect on education, health, labor supply, and consumption is greater when targeting women. Khandker ( 2005 ) is the third most influential study in this ranking, with 63(411) co-citations (total link strength) in our dataset. This study examines the effects of microfinance on poverty reduction in Bangladesh, at both the individual and aggregate levels, finding that microfinance contributed to poverty reduction, especially for female participants, in line with Pitt and Khandker ( 1998 ), concluding that microfinance boosts local economic growth at the village level. Morduch ( 1999 ) is the fourth most co-cited author in our sample statistics articles with 524 articles and 55(417) total link strengths. The author promotes an evaluation of innovative mechanisms beyond group-lending contracts, raising doubts about the effectiveness of microcredit programs in fighting poverty compared to traditional credit programs. Armendáriz and Morduch ( 2010 ) is the seventh most influential study according to this ranking, with 49(394) co-citations and total link strength.

These authors conducted extensive research on general topics that question the economic problems of microfinance, why such programs are needed, and why financial resources do not flow naturally to the poor. Karlan and Zinman ( 2011 ), with 46(437) co-citations(total link strength), and Karlan and Zinman ( 2010 ) and Stiglitz ( 1990 ), both with 44 co-citations and 325 and 437 total link strengths, respectively, are the ninth and tenth ( ex aequo ) most influential studies. Karlan and Zinman ( 2011 , 2010 ) adopted experimental research methodologies to analyze microcredit programs in the Philippines and South Africa, respectively. Karlan and Zinman ( 2011 ) found that microcredit may serve to increase the ability to cope with risk, strengthen community ties, and increase access to informal credit, but under channels different from those often proposed. The results of Karlan and Zinman ( 2010 ) corroborate the presence of binding liquidity constraints in South Africa and suggest that expanding the credit supply improves welfare. Stiglitz ( 1990 ) also analyzed the success of the Grameen Bank, suggesting that peer monitoring is largely responsible for the financial performance of the microcredit program in Bangladesh. Banerjee et al. ( 2015a ), with 70(605), Crépon et al. ( 2015 ) with 52(517), and Banerjee et al. ( 2015b ) with 51(398), Attanasio et al. ( 2015 ) with 48(517), and Angelucci et al. ( 2015 ) with 43(409) co-citations(total link strength), all published after 2012, also assume a prominent place in this ranking.

Keyword analysis

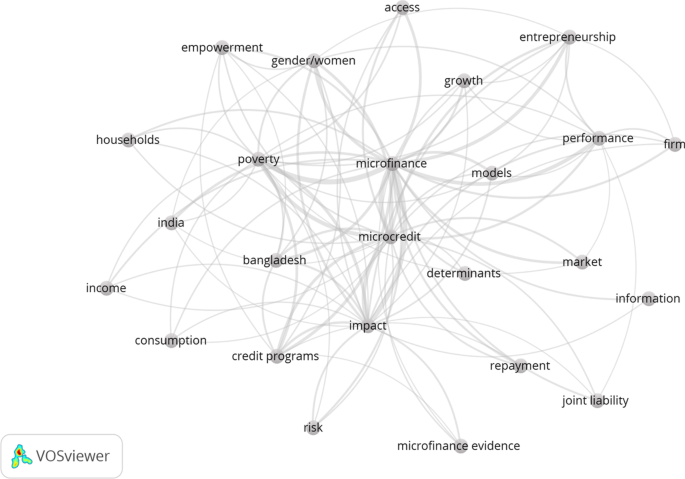

Table 8 reports the top 15 keywords in the 524 articles selected by the study methodology and published between 1:2012 and 3:2021 that attain at least 20 occurrences. This table’s right column reports the number of links a given keyword obtains with another keyword based on the total link strength. “Microfinance” is the most frequent keyword, with 320 occurrences (281 total link strength), indicating that this word acts as a termed concept in the literature. The words “microcredit,” “impact,” and “poverty” are also three of the most frequently cited words with 199(187), 154(148) and 138(136) occurrences (total link strength), respectively, suggesting that scholars are focusing on microfinance/microcredit outcomes, especially approaching these as tools for development and intervention with the potential to lift people out of poverty. The emerging topics of “gender/women,” “entrepreneurship,” and “empowerment” emphasize how the literature is increasingly evaluating the effects of microfinance/microcredit across various dimensions beyond the financing facet.

Figure 4 displays the most influential subjects based on the keyword occurrence networks. Footnote 6 These keywords are either extracted from the title and abstract of each article or sourced directly from the article keyword lists (Van Eck and Waltman 2014 ). To establish this network, we applied VOSviewer software and the fractional counting method, which considers the number of keywords (key), to explore the most relevant themes in microfinance outcomes. This figure also confirms that “microfinance” is widely interconnected with “microcredit,” “poverty,” and “impact.” These results again corroborate how researchers examine microfinance/microcredit as a tool to eradicate poverty in greater depth, especially through entrepreneurial activities.

Network of keyword occurrences in the 524 articles selected from the study sample, covering the period between1:2012 and 03:2021 according to the fractional counting method

Content analysis

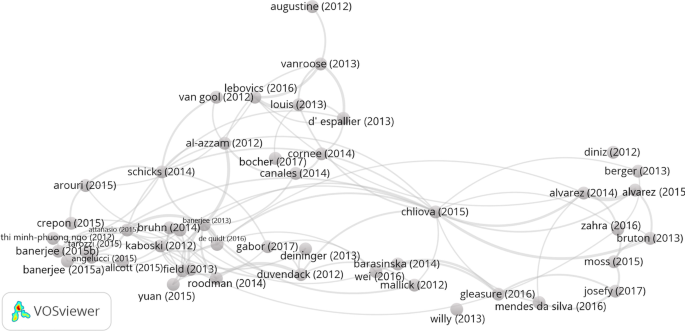

We deploy bibliometric analysis to explore the most relevant documents in this field of research. To identify the most influential publications, we applied VOSviewer to perform bibliometric coupling with a threshold of 25 citations for our analysis, yielding 47 articles out of a total of 524 with at least 25 citations, coupled into five clusters. Figure 5 depicts the knowledge map of the most-cited microfinance articles resulting from the fractional counting method. In a network, these nodes may be aggregated into clusters in which the weighting of edges is higher between the nodes within one cluster than those with another cluster. Thus, the VOSviewer algorithm returned five distinct clusters, with 11 documents in Cluster 1, 10 documents in Cluster 2, 9 documents in Cluster 3, 9 documents in Cluster 4, and 8 documents in Cluster 5. Footnote 7 Table 9 portrays the 48 papers in the five clusters. We subsequently carried out a content analysis with careful examination of the papers in each cluster to determine their common theme.

Knowledge map of the top articles cited by cluster according to the fractional counting method, based on 524 studies selected between 1:2012 and 3:2021

Cluster 1: socioeconomic outcomes of microfinance

This cluster comprised 11 studies focusing on the impacts of microfinance programs on socioeconomic outcomes with randomized experimental evaluations, questioning the influential role of microcredit on poor households. Banerjee et al. ( 2015b ) report that group lending programs in India increase the take-up of microcredit with a positive impact on small business investment and profits as well as on the expenditure of durable goods, but only over a short period. They also did not encounter any significant effects of group microcredit lending on health, education, or women’s empowerment. Banerjee et al. ( 2015a ), Angelucci et al. ( 2015 ), and Tarozzi et al. ( 2015 ) raised doubts about the transformative impacts of microcredit as a development tool. Angelucci et al. ( 2015 ) and Tarozzi et al. ( 2015 ) provide evidence that the effectiveness of microfinance is modest, with little or no evidence of any effectiveness in promoting micro-entrepreneurship, income, the labor market, consumption, social status, subjective well-being, schooling, or empowerment, despite affording a substantial increase in access to credit. Microcredit increases borrowing, which is mainly used for investment and risk management. However, this increased access to credit leads to only modest increases in female decision making, trust, and business size, with little effect on overcoming debt traps (Angelucci et al., 2015 ).

Crépon et al. ( 2015 ) suggest that the effects of microcredit are mainly derived from borrower characteristics rather than from externalities. Microcredit access leads to a significant rise in investment in the assets applied to self-employment activities and an increase in profits among households with higher abilities to borrow. Ngo and Wahhaj ( 2012 ) also demonstrate how access to microloans can lead to positive outcomes for intra-household decision-making and the welfare of women depending on their starting point conditions. They convey how women only benefit from microcredit when they are able to use the credit to invest in profitable joint activities, and when a large proportion of the household budget goes to the consumption of public goods. Otherwise, women borrowers may experience a decline in welfare.

Bruhn and Love ( 2014 ) document the remarkable effects of microcredit on labor markets and income levels, especially among individuals located in areas with lower pre-existing bank penetration and those with low incomes. Arouri et al. ( 2015 ) also provide evidence that access to microcredit, internal remittances, and social allowances can help households strengthen their resilience to natural disasters. Kaboski and Townsend ( 2012 ) indicate that microcredit lines might increase total short-term credit, consumption, agricultural investment, income growth (from business and labor), and wages, but decrease overall asset growth. Schicks ( 2014 ) provides measures for policymakers to address the over-indebtedness potentially arising from microcredit. Analyzing the loan-related sacrifices that borrowers report, the author identifies how male microborrowers are more likely to be over-indebted than women and that over-indebtedness is lower for borrowers with good levels of debt literacy. Based on a case study of microfinance trials, Allcott ( 2015 ) suggested that default rates may depend on the size of the trial samples. This study of program evaluations based on randomized control trials draws attention to the systematically biased out-of-sample predictions of program evaluations, even after many replications.

Microcredit has been referenced as a relevant tool for addressing credit constraints and promoting entrepreneurial activities. However, empirical studies have returned conflicting results, casting doubt on the strength of microcredit not only in financial outcomes but also in its actual ability to enhance several dimensions of human development. Stressing the research findings that indicate the need to consider the context of microcredit program deployment, we suggest paying particular attention to the development setting, as some studies demonstrate how microcredit programs are more effective in contexts where the credit markets have failed (i.e., poor settings), while others propose that microcredit intervention is boosted by environments with higher levels of social, economic, and institutional development. Research on this domain constitutes a fruitful field of research.

Cluster 2: Social performance or mission drift?

This cluster encompasses 10 studies. The focus of this cluster is access to microfinance, usually addressed in the literature as an indicator of MFI social performance (mission locked-in versus mission drift). Vanroose and D’Espallier ( 2013 ) report that MFIs reach more poor clients and prove more profitable in countries where access to the traditional financial system remains low. The results suggest that MFIs offset market failures in the traditional banking sector and flourish best when the formal financial sector is absent. However, MFIs have also shown remarkable social performance in countries with well-developed financial systems, as this pushes MFIs down the market and makes mission drift less likely. Cornée and Szafarz ( 2014 ) also provide evidence that banks offer advantageous credit terms for social projects. In turn, borrowers are motivated to repay loans, thus reducing the probability of default. Louis et al. ( 2013 ) and Lebovics et al. ( 2016 ) provide evidence that these dimensions of performance, and thus the social and financial aspects, are not mutually exclusive. Over a short time frame, there are positive relationships between social efficiency and financial performance (Lebovics et al. 2016 ; Louis et al. 2013 ). However, D’Espallier et al. ( 2013 ) adduce evidence pointing in the opposite direction and propose that microfinance faces a mission drift with the lack of subsidies, worsening the social performance of MFIs. Dealing with this trade-off has involved the implementation of several strategies, including charging higher interest rates, targeting less poor individuals, or reducing the proportion of female borrowers in order to compensate for public non-subsidization.

Bocher et al. ( 2017 ) demonstrate that individuals owning land and with larger households and/or savings experience a greater probability of getting microcredit. These results may indicate that some MFIs do not target the poorest of the poor. Canales ( 2014 ) examines how MFIs balance the pressures to pursue financial efficiency with the need to remain responsive to local needs. The authors document how MFI branches allowed discretionary diversity and decentralized flexibility through relational embeddedness to cater to local needs tend to achieve better performance. Thus, microcredit committees may yield substantial benefits for organizations and unbackable local individuals, for example, when dealing with missed repayments. Augustine ( 2012 ) proposes that the transparency of MFIs’ corporate governance policies is more important than their orientation, concluding that transparent declarations of their social orientation increase their performance. This may occur because public statements about MFI orientation generate commitments to the target community.

Among these clusters, the studies conducted by Al-Azzam et al. ( 2012 ) and Van Gool et al. ( 2012 ) are somewhat collateral to the main topic of MFI social performance. Van Gool et al. ( 2012 ) analyze whether the credit scoring system adopted in retail banking is appropriate for the microfinance industry, especially with regard to its social concerns, and reported that all the benefits of credit scoring models are commercially related. However, they also suggest that credit scoring may serve social concerns, for instance, by modelling information about indebtedness in order to avoid debt traps. Al-Azzam et al. ( 2012 ) focus on the effects of screening, peer monitoring, group pressure, and social ties on borrowing group repayment behaviors. The authors provide evidence that social ties built on religious attitudes and beliefs improve repayment performance. Thus, this study straddles the frontier with Cluster 3.

The trade-off between MFI outreach and profitability remains controversial. Several studies report that MFI shifts over time from social to financial performance as a result of both the costs of microfinance market contracts and the high fixed costs associated with small loans. Recent studies also reinforce that the national context also has a relevant impact on MFI performance. Consequently, several strategies have emerged to improve profitability, including increasing loan amounts, charging high-interest rates, public subsidization, and gaining efficiency through new technologies. Hence, the trade-off between outreach and sustainability continues to attract the research community studying governance and new organizational strategies, such as legal status, to improve MFI social and financial performance.

Cluster 3: group lending, social networks, and social capital

The third cluster involves nine studies focusing on group lending, social networks, and social capital, and how these relate to credit access and loan repayment. Group lending has the ability to build up social networks outside of the family (Attanasio et al. 2015 ), promoting social interactions that increase repayment rates (de Quidt et al. 2016 ), even in the absence of any collateral (Feigenberg and Pande 2013 ). One concern here is that the grace period might restrict social networks among group members, thus increasing default rates by lowering the effectiveness of informal insurance (Field et al. 2013 ).

Social capital is based on a “pre-existing connection between group members” (Banerjee 2013 : 496). Group members hold better information about each other than the respective MFI; they are therefore not only in a better position to screen and monitor the actions of each group member but also to punish those who default, for example, by withdrawing social capital from them (Banerjee 2013 ). Thus, group meetings increase social capital and networks and reduce the monitoring costs of lenders, which may encourage recourse to formal insurance, reducing the bail-in costs in case of default (de Quidt et al. 2016 ). According to the authors, by also functioning on an individual liability basis, group lending might facilitate increases in repayment rates depending on the social capital and networks developed within those groups. Group lending also displays the ability to increase both borrowing and entrepreneurship, as such an approach reduces the discouragement experienced by some individuals who are uncomfortable with borrowing on an individual basis but are willing to borrow in groups and share the liabilities, especially women with lower levels of education (Attanasio et al. 2015 ).

Wei et al. ( 2016 ) indicate how credit scoring models encapsulating client social networks—their social score—might provide a means of raising access to microcredit as an alternative to group lending. However, Yuan and Xu ( 2015 : 232) drew attention to how poorer households “are limited by social networks and they have no financial means to invest in their social capital to expand their social network.” Donou-Adonsou and Sylwester ( 2016 ) examine the relationships between financial development and poverty reduction, a topic on the frontier with Cluster 1. Gabor and Brooks ( 2017 ) seem to approach the frontier with Cluster 4, as they analyze the growing importance of digital-based programs for fostering financial inclusion in the fintech era.

Group-lending mechanisms are still attracting the attention of scholars. The social cohesion characterizing borrowing groups explains the effectiveness of the screening and monitoring stages that reflect in the repayment rates as well as in the outcomes of loans made for business purposes. Furthermore, this requires a deeper understanding of where group lending contexts generate advantages over individual contracts, for example, in developing countries where social capital often implies investments that poor people are not able to attain.

Cluster 4: poverty alleviation, entrepreneurial activities, and financial service innovations

Cluster 4 includes nine studies that focus on the contribution of entrepreneurial activities and financial service innovations to poverty alleviation. The literature posits that entrepreneurship represents a crucial pathway for alleviating poverty (Bruton et al. 2013 ) arising from socioeconomic and technological growth and development (Zahra and Wright 2016 ), which requires an industrialized approach to offset the multiple market failures prevailing in developing economies (Alvarez et al. 2015 ). This might explain why microcredit generally has stronger socioeconomic impacts (especially for the empowerment of women) in more challenging contexts and when targeting client entrepreneurs (Chliova et al. 2015 ). However, not all entrepreneurial activities lead to sustainable economic growth. For example, self-employment opportunities in sectors requiring low levels of human capital tend to perpetuate abject poverty (Alvarez and Barney 2014 ). Significant economic growth and poverty alleviation depend on the ability to discover and create new business opportunities based on more effective utilization of human capital, property rights, and financial capital (Alvarez and Barney 2014 ; Alvarez et al. 2015 ). In fact, local development (Diniz et al. 2012 ) and entrepreneurial success (Josefy et al. 2017 ) depend on the ability to mobilize resources, including financial capital. However, to be effective, an increase in financial resources requires accompanying financial education.

Formal credit markets and even traditional microfinance sources for encouraging investment, innovation, and launching new ventures may no longer be sufficient to overcome the persistent societal challenges of poor countries (Zahra and Wright 2016 ). According to these authors, peer-to-peer lending and crowdfunding may provide a solution for financial, social, and environmental wealth. “Crowdfunding refers to the practice of raising funds for a venture or project from dispersed funders typically using the Internet as a channel of operation” (Josefy et al. 2017 : 163). The availability of funds for promoting microenterprises is expanding rapidly through crowdfunding platforms, such as Kiva, which provides a greater audience of lenders for microenterprises’ signaling autonomy, competitive aggressiveness, and risk-taking (Moss et al. 2015 ). The success of loan campaigns on crowdfunding platforms also depends on contextual community attributes, such as the cultural values of the target audience that shape the level of interest the projects generate in the crowd (Josefy et al. 2017 ).

Information and communication technology (ICT) seems to be an alternative for supporting financial inclusion and fostering social inclusion (Diniz et al. 2012 ). By examining an ICT-based platform, Berger and Nakata ( 2013 ) analyze the socio-technical characteristics that technological solutions may have to successfully implement financial service innovations in the field of microfinance. According to these authors, these innovations tend to produce better results when they are congruent with the unique surrounding socio-human, regulatory, and market conditions.

The literature references entrepreneurship, particularly in deprived environments, as the only option to earn money due to the absence of any other market participation. In such contexts, microcredit enhances entrepreneurial activities through the issuance of small and unsecured loans. Scholars still raise concerns about the effectiveness of such programs, mainly due to the lack of profits generated by the financed ventures to pay the costs of loans and ensure loan repayment. The lack of management skills is an additional issue pointed out by researchers. Recently, new finance alternatives have emerged, especially crowdfunding, which deploys online platforms to allow entrepreneurs to connect with prospective crowd funders—the crowd—who finance new entrepreneurial ventures by lending small amounts. Empirical studies in this area are still in their infancy, but strengthen the perspective that crowdfunding may democratize entrepreneurial finance, particularly among the more vulnerable, and help break the poverty cycle.

Cluster 5: gender and thematic frontiers

The final cluster included eight studies. This cluster covers the impacts of microcredit targeting the vulnerable, with some articles focusing specifically on women. Thus, in this cluster, we encounter several studies bordering on the frontier with other clusters, such as Cluster 1 (e.g., Duvendack and Palmer-Jones 2012 ; Roodman and Morduch 2014 ), Cluster 3 (e.g., Willy and Holm-Müller 2013 ; Mallick 2013 ; Mendes-Da-Silva et al. 2016 ), and Cluster 4 (Deininger and Liu 2013 ; Barasinska and Schäfer 2014 ; Mendes-Da-Silva et al. 2016 ; Gleasure and Feller 2016 ).

Duvendack and Palmer-Jones ( 2012 ) and Roodman and Morduch ( 2014 ) re-examined previous studies, specifically those developed by Pitt and Khandker ( 1998 ), questioning the evidence they reported after studying Bangladesh microcredit programs. Both studies raise doubts about the microcredit outcomes identified by Pitt and Kandker. However, Duvendack and Palmer-Jones ( 2012 ) corroborate the positive effects of microcredit for vulnerable women. Gleasure and Feller ( 2016 : 110) conducted a meta-triangulation analysis of crowdfunding research. Their results suggest that crowdfunding generates new opportunities and describing how these “present genuinely new ideas and behaviours” and not “simply a migration of established practices into a new domain.” For example, crowdfunding may solve some of the discrimination problems faced by women in traditional credit markets, as the study found no gender effects on the likelihood of receiving funds. Deininger and Liu ( 2013 ) report that a combination of microcredit and self-help group initiatives (including training and capacity-building programs) produces positive pro-poor effects, especially by promoting the empowerment of women and health and improving consumption and income diversification in the short term.

Mallick ( 2013 : 179) examines whether continued support for poor individuals, which includes “management assistance, a subsistence allowance, health care facilities, and support for building social networks,” plays a crucial role in borrowing decisions. The authors indeed conclude that this “big push” affords the extremely poor access to microfinance. This effect is higher for larger households and for households with male heads, and increases with the average levels of education and income in the household. Social capital also plays an important role in borrowing decisions, in keeping with several of the findings systematized in Cluster 3. Mendes-Da-Silva et al. ( 2016 ) also support the notion that entrepreneurs’ social networks might play a central role in funding, especially on crowdfunding platforms. Willy and Holm-Müller ( 2013 ) examined the effects of social influence, social capital, and credit access in the agricultural sector and demonstrated how they represent significantly positive predictors of farm soil conservation.

Scholars have identified how entrepreneurship represents one path to the empowerment of women, particularly in developing countries, although empirical evidence indicates a mixed range of outcomes. Some studies stress that microcredits/microfinance endows women with great control over the operations of their ventures and household resources, thus fostering their empowerment. Others argue that microfinance programs do not take into account the cultural and social context of their deployment and thus, in some ways, sustain the existing hierarchy of classes, increasing tensions among household members and providing new forms of dominance over women. Recent research posits that new technologies extending basic financial services have a large effect at a relatively low cost and are susceptible to deepening through knowledge transfers in the form of financial literacy.

Mapping the trends

This section discusses the most recent and influential articles on microfinance topics published in the last three years (2018–3:2021) and ranked on ABS with a classification of 4 or 4*, yielding a total of 11 articles. Footnote 8 As they are more recent, these articles have been cited less often and therefore excluded from the bibliographic coupling analysis carried out in Sect. 4 . We also identified the most relevant emerging topics in the field.

Emerging trends

Table 10 systematizes the scope and main findings of all the articles published in ABS (4 or 4*)-ranked journals in the field of microfinance. Recent studies have promoted new approaches to examining the socioeconomic impacts of microfinance at both the macro (Buera et al. 2021 ; Duflo 2020 ) and micro (Burke et al. 2019 ; Singh et al. 2021 ) levels. The theme of MFI mission drift or mission lock-in is still at the fore in most recent literature (Alon et al. 2020 ), as well as the benefits to the group and joint lending (Attanasio et al. 2019 ), and reputation, social capital, and network (Li and Martin 2019 ). ABS (4 and 4*)-ranked journals have also published papers on somewhat underexplored topics on the frontiers of some clusters, such as alternative programs for promoting social changes (Kim et al. 2019 ), the impact of microcredits on subjective well-being (Bhuiyan and Ivlevs 2019 ), and the roles of cultural institutions (Drori et al. 2018 ) and government regulation (Tantri 2018 ) in the microfinance performance returns.

After analyzing the keywords of the most influential studies published between 1:2018 and 3:2021 (whether or not ABS ranked), Table 11 presents the most recent trends on microfinance literature, with “microfinance,” “microcredit,” “impact,” and “poverty” still representing the keywords with the most occurrences. Comparing Tables 8 with 11 , we observe that roughly half of the occurrences of these keywords relate to articles published since 2018. “Gender/women,” “entrepreneurship,” “performance,” and “empowerment” are trending topics, gaining in importance in the microfinance literature over the last three years.

Entrepreneurship and performance

Microfinance appears as an instrument that promotes access to capital for impoverished individuals otherwise excluded from financial systems and gaining popularity as a means of enhancing entrepreneurial activities (Yunus 1998 ), enabling vulnerable people to engage in market transactions and end subsistence-based livelihoods. Consequently, entrepreneurship among individuals living in poverty settings represents a more important outcome than much traditional entrepreneurship research in developed countries.

However, the empirical literature is inconclusive about the ability of microfinance to enhance the financial standing of vulnerable people (Khavul et al. 2013 ). This ambiguity is strengthened when coupled with other development outcomes, specifically the capabilities of the poor across several facets of human development (e.g., empowerment, education, health). Thus, researchers perceive that a key aspect for continuing scrutiny derives from the effectiveness or otherwise of microfinance, justifying the emergence of an increasing number of papers on this domain. Furthermore, some authors maintain that the context of microfinance deployment, hence the national context and specific features, impact the outcomes of such tools (Crépon et al. 2015 ; Weiss and Montgomery 2005 ), particularly in environments where credit markets have failed. Hence, the performance effect of microfinance is greater in developing countries (Chliova et al. 2015 ). Meanwhile, other authors emphasize the synergetic relationships between institutional and socioeconomic developments as outcomes that microfinance can achieve. However, it remains unclear whether microfinance aligns with supplementary or complementary outcomes.

Our bibliometric analysis demonstrates that when designing programs, microfinance institutions should focus on borrower characteristics instead of standard credit contracts; otherwise, credit only worsens problems of over-indebtedness. To achieve win–win propositions, in addition to credit, microfinance interventions should also involve education and training programs to boost the capabilities of less advantaged citizens to start, maintain, and grow their own ventures. This seems particularly relevant in less developed entrepreneurial ecosystems as well as in regions where the economic development model is based on intensive (low-educated) human capital that is more exposed to persistent poverty traps and anemic economic growth. By achieving successful entrepreneurial outcomes, educated and trained entrepreneurs increase their financial and non-financial outcomes. In sum, our findings shed light on the powerful interwoven effects of knowledge, credit, and entrepreneurship in lifting poor entrepreneurs out of poverty, particularly in deprived settings.

Empowerment and gender

Gender inequalities constitute one of the greatest barriers to human development (Conceição 2019 ), especially in developing countries (Ojong et al. 2021 ). In these countries, women may face additional challenges in obtaining education and a well-paid job, in addition to working an average of three times more often in unpaid and domestic activities than men (UN Women 2020 ). Scholars have emphasized how entrepreneurship provides a pathway to empower women, stressing that microfinance is a reliable tool that leverages its effects primarily through business activities.

The strength of microfinance as a development intervention tool to transform social and economic structures relies on its potential ability to lift people out of poverty (Yunus 1998 ) by running small ventures that generate financial resources to increase entrepreneurs’ financial well-being (Mckernan 2002 ). However, beyond wealth creation, this approach forecasts a capacity for microfinance to boost the livelihood of recipients across several dimensions (Buckley 1997 ; Miller et al. 2012 ). Hence, this places great emphasis on non-financial human development outcomes, specifically women empowerment (Hermes and Lensink 2011 ), which is particularly relevant in poor settings, as the constraints women face regarding market participation constitute a form of dominance and control over women. Women empowerment emerges as a multidimensional concept (Weber and Ahmad 2014 ) that, besides access to credit, also includes income, contribution to household expenditure, health, education, control over resources, participation in community and household decision-making, social mobility and freedom of movement, and self-worth (Kabeer 2001 ; Noponen 2003 ). Therefore, when considering these dimensions, any substantial increase in access to credit certainly does not automatically promote subjective well-being or empowerment (Angelucci et al. 2015 ; Tarozzi et al. 2015 ). Nevertheless, studies suggest that the provision of small loans to women enables them to more effectively mitigate gender barriers by running their own businesses, increasing their mobility outside the household, and achieving the ability to make decisions (Todd 1996 ). In addition, through economic activities, household income increases, improving their standard of living, and consequently enhancing the education of their children and leading them to adopt more preventive health practices (Yunus 1998 ).

The mission to promote the empowerment of women through the provision of small loans also depends on training programs and the ability of MFIs to understand the characteristics of female borrowers (Hunt and Kasynathan 2001 ). Thus, MFIs must design and implement internal policies to mitigate gender biases based on the conditions of female borrowers at the outset. Promoting the participation of women in decision-making processes in higher loan cycles, for example, will spread women’s empowerment (Swain and Wallentin 2009 ) and positively increase the abilities of female borrowers to decide how to use their loans (Weber and Ahmad 2014 ). Hence, recent research suggests a more holistic approach to answering the extent to which microfinance meets sustainable development goals, for example, eradicating poverty, reducing inequalities, and boosting sustainable development.

In fact, the outreach of microfinance itself is changing with the emergence of fintech, namely prosocial crowdfunding platforms. Fintech has had a noteworthy impact on the financial system by reducing operating costs, providing higher quality services, and increasing user satisfaction (Kou et al. 2021 ). In the context of microcredit, prosocial crowdfunding platforms act as socially oriented digital marketplaces, particularly targeting poor settings (Meyskens and Bird 2015 ), where lenders provide credit access to impoverished people underserved by the banking industry, facilitating the liberalization of the financial sector at a global level. In turn, this boosts more inclusive financial and social systems (Dupas and Robinson 2013 ) that generate large effects at relatively low costs.

To be fruitful, the crowdfunding platform design cannot ignore the decision dynamics underlying not only traditional e-commerce platforms but also fintech. Commercial digital platform users base their judgments and decisions on trustworthy reviews. Likewise, we posit that prosocial lenders will increasingly drive digital funding decisions on systematized crowd reviews on borrowers and MFI. Thus, as in many financial applications (see Li et al. 2021 ), detecting clusters of financial and social-environment data (such as borrowers’ social capital and MFIs’ financial and social performance) will be critical for inferring lenders’ behavior and maximizing the performance of crowdfunding platforms and their outcomes. This might constitute a new application case for the so-called data-driven opinion dynamics model (see Zha et al. 2020 ), because financial technologies provide important advantages in processing big data into more meaningful, cheaper, worldwide, and more secure data than conventional methods (Lee and Shin 2018 ).

Thus, we might expect these topics to guide future research, providing a starting point for returning practical implications for policymakers, academics, players in crowdfunding markets, and microentrepreneurs.

Conclusions and implications

Poverty remains a key global challenge. According to the World Bank forecast, the total number in poverty is due to rise for the first time in over two decades, from 119 to 124 million by the end of 2021. In this context, microfinance has emerged as an innovative and sustainable poverty alleviation tool to serve more vulnerable people, particularly in developing countries. However, some scholars have challenged its proposed benefits (e.g., Chliova et al. 2015 ; Morduch 1999 ). Through the application of bibliometric methods, this paper reviews the most recent literature on the trends in the outcomes for microfinance recipients, thus focusing on the demand side. The study examines 524 articles collected from the Web of Science database published between 1:2012 and 3:2021.

Based on keywords, co-occurrences, and links between citations to obtain knowledge maps, the findings demonstrate that in both the theoretical domain and the empirical, research still casts doubt on the capacity of microfinance to generate positive outcomes beyond wealth creation, particularly in terms of empowerment, education, and health (Cluster 1). Further studies in this domain should consider the macro-context when undertaking empirical research; otherwise, policies designed based on such limited evidence may yield unexpected outcomes contrary to the forecast socioeconomic goals. Furthermore, entrepreneurship, through granting small loans (microcredits), represents a precondition for individuals living in poverty starting small businesses and the most efficient strategy for leaving behind subsistence-based lives. However, as lack of management skills may hamper the survival of these businesses, providing finance literacy training has a positive impact on the performance of such small ventures (Cluster 4). Nowadays, the reach of microfinance is changing due to the emergence of crowdfunding, as the crowd of lenders provides prompt credit access to start-ups launched by impoverished microentrepreneurs and empowering women (Cluster 5). This research is still in its infancy, but by sharing risks worldwide, informal lenders can extend credit through small loans, thus democratizing entrepreneurial finance to boost new ventures. The group lending methodology remains an efficient instrument for overcoming the lack of access to financial resources by building up social networks in the community (Cluster 3). Therefore, research in this field should examine how new screening models and credit social models, along with soft information, leverage the financial performance of new ventures and enhance financial inclusion and foster the social inclusion of such individuals. This study also identifies the role of MFIs in addressing market failures in the traditional banking sector, stressing the idea that MFIs gradually shift over time from social performance (outreach to the poor) to financial performance (Cluster 2). Thus, taking into account the recognized role played by microfinance and MFIs in the process of socio-economic transformation, public policy must consider the need to compensate for the market’s financial performance gap in the poorest economies by subsidizing credit activities to avoid mission drift effects. This needs to be accompanied by a transformation of MFI corporate governance policies to ensure transparency in their operations and selection of microfinance recipients. Overall, this study corroborates that microfinance is a distinct field of development thinking that requires a more holistic approach to overcome poverty and boost economic and human development at the global level.

As with any bibliometric analysis, this study has some limitations. As we gathered bibliometric data from the WoS database, we may have missed studies listed only in other databases (e.g., Scopus). Furthermore, some research domains within microfinance and microcredit may rely more on citations than others, which may reduce the scope of the outputs within clusters. Finally, early career researchers may not fare well in citation and co-citation studies even when producing seminal research, which may reduce the impact of their studies as measured using tools deployed to gather bibliometric data.

One of the greatest advantages of the Web of Science database, compared with PubMed, Scopus or Google Scholar, is its timeline coverage in terms of quality research production (Falagas et al., 2008 ). This aggregates research information from five indexed databases: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI Exp.), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI), and the index of Chemistry and Current Chemical Reactions (Goodman 2005 ). The SCI Exp. includes articles published since 1900; and with SSCI and A&HCI dating back to 1956 and 1975, respectively (Meho and Yang 2007 ).

We would acknowledge how searches based on a set of keywords include certain limitations (e.g., Costa et al, 2016 ). One way of improving the selection process in a systematic literature review involves adopting a Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – PRISMA (Moher 2009 ).

VOSviewer is a program developed for constructing and viewing bibliometric maps based on the visualization of similarities (VOS) technique (Van Eck and Waltman, 2009 ).

The year 2021 reflects only the publications until March.

https://charteredabs.org/academic-journal-guide-2018-view/ (accessed in April 2021).

The following similar keywords were merged: “programs” and “credit programs” (to “credit programs”); and, “gender” and “women” (to “gender/women”).

VOSviewer software only reports the name of the first author.

Paul et al. ( 2017 ) examine the most influential papers in the last four year. Spasojevic et al. ( 2018 ) also examine the papers ranked as class ABDC. Furthermore, Gutiérrez-Nieto and Serrano-Cinca ( 2019 ) select the top 5% articles for analysis as the excellent highly cited papers.

Abbreviations

Arts and Humanities Citation Index

Association of business schools

Information and communication technology

Microfinance institutions

Mean technical efficiency

Preferred reporting item for systematic review and meta-analysis

Science citation index expanded

Social enterprises

Social Sciences Citation Index

Sustainable development goal

Visualization of similarities

Web of science

Akter S, Uddin MH, Tajuddin AH (2021) Knowledge mapping of microfinance performance research: a bibliometric analysis. Int J Soc Econ 48(3):399–418. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-08-2020-0545

Article Google Scholar

Al-Azzam M, Carter Hill R, Sarangi S (2012) Repayment performance in group lending: evidence from Jordan. J Dev Econ 97(2):404–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.06.006

Allcott H (2015) Site selection Bias in program evaluation. Q J Econ 130(3):1117–1165. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjv015

Alon I, Mersland R, Musteen M, Randøy T (2020) The research frontier on internationalization of social enterprises. J World Bus 55(5):101091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101091

Alvarez SA, Barney JB (2014) Entrepreneurial opportunities and poverty alleviation. Entrep Theory Pract 38(1):159–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12078

Alvarez SA, Barney JB, Newman AMB (2015) The poverty problem and the industrialization solution. Asia Pacific J Manag 32(2):23–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-014-9397-5

Angelucci M, Karlan D, Zinman J (2015) Microcredit impacts: evidence from a randomized microcredit program placement experiment by compartamos Banco. Am Econ J Appl Econ 7(1):151–182. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130537

Armendáriz B, Morduch J (2010) The economics of microfinance. MIT Press, Cambridge

Google Scholar

Arouri M, Nguyen C, Ben YA (2015) Natural disasters, household welfare, and resilience: evidence from rural Vietnam. World Dev 70:59–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.12.017

Attanasio O, Augsburg B, De Haas R et al (2015) The impacts of microfinance: evidence from joint-liability lending in Mongolia. Am Econ J Appl Econ 7(1):90–122. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130489

Attanasio O, Augsburg B, De Haas R (2019) Microcredit contracts, risk diversification and loan take-up. J Eur Econ Assoc 17(6):1797–1842. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvy032

Augustine D (2012) Good practice in Corporate Governance: transparency, trust, and performance in the microfinance industry. Bus Soc 51(4):659–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650312448623

Banerjee AV (2013) Microcredit under the microscope: What have we learned in the past two decades, and what do we need to know? Annu Rev Econom 5(1):487–519. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-082912-110220

Banerjee A, Duflo E, Glennerster R, Kinnan C (2015a) The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomized evaluation. Am Econ J Appl Econ 7(1):22–53. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130533

Banerjee A, Karlan D, Zinman J (2015b) Six randomized evaluations of microcredit: introduction and further steps. Am Econ J Appl Econ 7(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20140287

Barasinska N, Schäfer D (2014) Is crowdfunding different? Evidence on the relation between gender and funding success from a german peer-to-peer lending platform. Ger Econ Rev 15(4):436–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/geer.12052

Berger E, Nakata C (2013) Implementing technologies for financial service innovations in base of the pyramid markets. J Prod Innov Manag 30(6):1199–1211. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12054

Besley T, Coate S (1995) Group lending, repayment incentives and social collateral. J Dev Econ 46(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(94)00045-E

Bhuiyan MF, Ivlevs A (2019) Micro-entrepreneurship and subjective well-being: evidence from rural Bangladesh. J Bus Ventur 34(4):625–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.09.005

Bocher TF, Alemu BA, Kelbore ZG (2017) Does access to credit improve household welfare? Evidence from Ethiopia using endogenous regime switching regression. Afr J Econ Manag Stud 8:51–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-03-2017-145

Bradley SW, Mcmullen JS, Artz K, Simiyu EM (2012) Capital is not enough: innovation in developing economies. J Manag Stud 49(4):684–717. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01043.x

Brau JC, Woller GM (2004) Microfinance: a comprehensive review of the existing literature. J Entrep Financ JEF 9(1):1–28

Bruhn M, Love I (2014) The real impact of improved access to finance: evidence from Mexico. J Finance 69(3):1347–1376. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12091

Bruton GD, Ketchen DJ, Ireland RD (2013) Entrepreneurship as a solution to poverty. J Bus Ventur 28(6):683–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.05.002

Buckley G (1997) Microfinance in Africa: Is it either the problem or the solution? World Dev 25(7):1081–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00022-3