- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Do Democracy and Capitalism Really Need Each Other?

- Laura Amico

Scholars from around the world weigh in.

Democracy and capitalism coexist in many variations around the world, each continuously reshaped by the conditions and the people forming them. Increasingly, people have deep concerns about both. In a recent global survey, Pew found that, among respondents in 27 countries, 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working. Further, Millennials and Gen Zs are increasingly disinterested in capitalism, with only half of them viewing it positively in the United States .

- Laura Amico is a former senior editor at Harvard Business Review.

Partner Center

Democracy field notes

Questions about the troubled spirit and ailing institutions of contemporary democracy

Capitalism and Democracy [part 1]

Professor of Politics, University of Sydney

Disclosure statement

John Keane receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

University of Sydney provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Let’s begin with a discomforting fact often forgotten in recent years: ‘free market’ capitalism is not necessarily the best friend of democracy. Since the early years of the 19th century, especially during periods of economic stagnation and mass unemployment, the relationship between capitalism and democracy has actually been a source of great social unrest, state violence and public pressures for institutional reform. That’s why, at various moments during the past two centuries, the modern capitalist system has been charged by its critics with crushing the spirit and substance of representative self-government.

Shortly after World War One, the American economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen captured the point in a famous formulation. There are historical moments, he noted, when ‘democratic sovereignty’ is converted into ‘a cloak to cover the nakedness of a government that does business for the kept classes’.

The current period of global recession and stagnation, centred in the Atlantic region, has helped revive new versions of this old formula. Thanks especially to the work of prominent European political economists, political analysts and historians, Wolfgang Streeck , Colin Crouch , Thomas Piketty and Jürgen Kocka among them, the subject of capitalism versus democracy is back. Market failures are having political effects; they are breathing new life into an old subject that demands fresh thinking and a new democratic politics that, so far, has not happened on any scale.

One shortcoming of the new European contributions is their general reluctance to engage details of the long history of links between democracy and markets. What can be learned from the deep past? Well, minimally, the famous remark by the historian Barrington Moore Jr , ‘no bourgeois, no democracy’, turns out to be less than plausible. The historical record suggests that things have been more complex, that viable democratic institutions, such as citizens assemblies, public juries, watchdog bodies, political parties and periodic elections, have in fact been contingently related to a wide repertoire of property forms.

The early Greek assembly democracies, for instance, enjoyed a functional but tense relationship with commodity production and exchange. Within these polities, the life of (male) citizens was widely seen as standing in opposition to the production of goods and services by women and slaves in the sphere of the oikos . Politics trumped economics; democracy rested upon slavery. By contrast, the modern forms of representative democracy that first sprang up in the Low Countries, at the end of the sixteenth century, were tightly bound to profit-driven commodity production and exchange. Modern capitalism and representative democracy were twins. The pair often quarrelled. ‘The further democratisation advanced’, the distinguished German historian Jürgen Kocka notes, ‘the more likely it was to find large parts of the bourgeoisie on the side of those who warned against, criticised or opposed further democratisation.’

At the outset, things seemed otherwise. Modern capitalism appeared to be supportive of parliamentary government. Capitalist dynamics helped gradually erode older forms of unequal dependency of the feudal, monarchic and patriarchal kind. The spread of commodity production and exchange triggered tensions between state power and property-owning and creditor citizens jealous of their liberties provided by civil society. Modern capitalism also laid the foundations for the radicalisation of civil society, in the shape of the birth of social democracy backed by powerful mass movements of workers protected by trade unions, political parties and governments committed to widening the franchise and building welfare state institutions.

This much is clear. Yet since early modern times, and especially after 1945, capitalist markets have been a mixed blessing for democracy in representative form. The dynamism, technical innovation and enhanced productivity of 'free’ markets have been impressive. Equally notable have been their rapaciousness, unequal (class-structured) outcomes, reckless exploitation of nature and their vulnerability to bubbles, whose inevitable bursting generates wild downturns. These downturns typically breed populist manias, fear and misery in people’s lives, in the process destabilising democratic institutions, as happened on a global scale during the 1920s and 1930s, and is again happening today, with accelerating momentum.

How can we best summarise the relationship between capitalism and democracy today? Here’s an inexact but pithy formula: in these early years of the 21st century, monitory democracies can neither live with capitalist markets nor live without capitalist markets. The formula is designed to unsettle. It aims to provoke second thoughts and fresh thinking; along the way, it also helps to shed some light on the wildly divergent scholarly and political assessments of the future of capitalism and democracy.

Free markets?

According to defenders of the ‘free market’, more than a few of whom are dogmatic market fundamentalists, political democracy is an unwanted parasite on the body of economic growth. Democracy whips up unrealistic public passions and fantasies. It distorts and paralyses the spirit and substance of rational calculations upon which markets functionally depend; understood as government based on majority rule, democracy is said to be profoundly at odds with free competition, individual liberty and the rule of law. What is therefore required is ‘ democratic pessimism ’ and (Friedrich von Hayek’s famous thesis) the restriction of majority-rule democracy in favour of ‘austerity’ (cutbacks and restructuring of state spending) and limited constitutional government (‘demarchy’ ) whose job is to protect and nurture ‘free markets’ protected by the rule of law.

Other scholars, political commentators, policy makers and politicians stake out the contrary view. They maintain that since markets are never ‘naturally’ free but always, in one way or another, the creature of laws and governing institutions, market failures and market ‘externalities’ require political correction. Well-designed political interventions that draw democratic strength from popular consent are needed to redistribute income and wealth, to repair environmental damage caused by markets and to breathe new life into the old ideals of equality, freedom and solidarity of citizens.

Exactly what this general democratic formula means in practice has been hotly disputed since the earliest (19th-century Chartist and co-operative movement) public attacks on markets in the name of ‘the people’. The democratisation of markets has meant different things at different times to different groups of people. For some analysts, democracy requires the replacement of markets by the principles of Humanity ( Giuseppe Mazzini ), or by communist visions of ‘social individuality’ (Karl Marx) and post-market individualism ( C.B. Macpherson ). For the majority of card-carrying democrats of the past century, the democratisation of markets meant greater state intervention and control of markets. When confronted with the collapse of the Soviet model of socialism, some analysts tried to develop fruitful comparisons among contemporary Anglo-Saxon, Rhineland, Japanese, Indian, Chinese and other ‘varieties of capitalism’. Recognising that parliamentary democracy is constantly vulnerable to corporate ‘kidnapping’, these analysts champion updated versions of the social democratic vision of liberating (‘de-commodifying’) areas of life currently in the grip of unregulated markets. What is needed, they argue, is the restriction of markets: new government policies that ‘socialise’ the unjust effects of competition by ‘embedding’ markets within civil society institutions guaranteed by election victories, welfare mechanisms and legal regulation.

Whether such policies and regulations can succeed without straddling borders and through state efforts alone remains an open question. Yet the broad vision is bold, and clear: in defence of the democratic principle of equality, government instruments are needed to limit ‘predatory’ forms of capitalism. The priority is to protect people and their ecosystems, to nurture social citizenship rights through a politics of redistribution that includes the defence of public services, raising the minimum wage and enforcing new contract law arrangements that empower workers and consumer citizens.

Such proposals for a new politics of breaking the grip of capitalist markets on people’s lives are important, above all because they restore the old subject of worsening inequality to its rightful place in scholarly work on democracy. Pauperism mixed with plutocracy is today a feature of practically every democracy on our planet. Things are everywhere growing worse, not better. For all democrats and scholars sympathetic to democracy, disparities between rich and poor ought to be intellectually and politically scandalous. ‘Enough is enough’ should be the new democratic mantra.

Among the top priorities of researchers must be to remind citizens and their representatives that wide gaps between rich and poor, in the long run, have ruinous effects on civil society and the whole political order. Citizens in unequal societies, many researchers have shown , more likely end up sick, obese, unhappy, unsafe, or in jail. Such dysfunctions, in various ways, impact the lives of the rich. Even plutocrats feel the pinch; nobody is safe from the scourge of inequality. Inequality is perversely egalitarian.

Whether in South Africa, Greece, Brazil or the United States, market inequality endangers the spirit and institutions of monitory democracy in other ways. Concentrated wealth likes secrecy, surveillance and law and order. It outvotes ballots; and wealth tilts public policy in favour of the rich, towards short-sighted rewards or special treatment (deregulation, tax breaks) and away from the public goods (education, infrastructure) so essential to future economic growth. Finally, in normative terms, capitalist inequality plainly contradicts the democratic spirit of equality. Like salt to the sea, the principle of equality is the quintessence of the democratic ideal. That’s why, historically speaking, every form of democracy worth its salt has stood against the presumption that the wealthy are ‘naturally’ entitled to rule. When they don’t, and when the gap between rich and poor grows ever wider, they are asking for political trouble.

To be continued….

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Communications and Engagement Officer, Corporate Finance Property and Sustainability

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Democracy is in deeper trouble than capitalism

Subscribe to the economic studies bulletin, isabel v. sawhill isabel v. sawhill senior fellow emeritus - economic studies , center for economic security and opportunity @isawhill.

March 18, 2020

This piece originally appeared in the Harvard Business Review , as part of their 5-Part Series: Democracy Under Attack, on March 11, 2020.

Capitalism and democracy absolutely need each other to survive, but right now it is democracy that is most threatened.

Capitalism is the right way to organize an economy, but it’s not a good way to organize a society. Markets do a good job of allocating resources, fostering dynamism, and preserving individual choice, but they cannot solve climate change, too much inequality, or the plight of workers whose jobs have been destroyed by trade or technology.

When government fails to address these or other systemic problems, democracy begins to lose its legitimacy. In desperation, citizens turn to populists on the right or the left. If these leaders then prove unable to keep their promises, trust in government erodes further. Political instability begins to threaten capitalism itself.

We are now seeing that spiral in action. Dissatisfaction with democracy in the U.S. has risen by one-third since the mid-1990s and now includes about half the population, according to the Centre for the Future of Democracy at Cambridge University. It was the white working class, whose counties had been ravaged by a loss of jobs , that elected Donald Trump in 2016. Yes, his supporters had cultural anxieties (opposition to immigration in particular) in addition to economic ones, but there’s no denying the surprisingly strong county-level correlation of votes for Trump with long-term economic distress, very low employment rates, plant closings related to trade, and the location of the opioid epidemic.

Related Content

Isabel V. Sawhill

July 9, 2019

October 10, 2018

Oren Cass, Robert Doar, Kenneth A. Dodge, William A. Galston, Ron Haskins, Tamar Jacoby, Anne Kim, Lawrence Mead, Bruce Reed, Isabel V. Sawhill, Ryan Streeter, Abel Valenzuela Jr., W. Bradford Wilcox

November 26, 2018

Now the U.S. is in the midst of another presidential campaign and the signposts of instability are rising on the left. If Bernie Sanders wins the Democratic nomination this year, it will be clear that it is not just the working class that is fed up but also young people and progressives, who believe the system is corrupt and that only a democratic socialist can save the day. But a Sanders revolution would almost surely disappoint his voters further, since enacting most of his proposals is politically infeasible, leading to more fraying of trust in government.

Fewer than half of 18- to 29-year-olds now support capitalism. They are right that markets without guardrails do not produce a healthy society. But a government that overreaches by trying to replace the market in areas like health care or job creation will not restore that trust. This is the balancing act we face.

U.S. Democracy

Economic Studies

Vanessa Williamson

May 14, 2024

2:00 pm - 3:15 pm EST

Brookings Institution, Washington DC

1:30 pm - 2:45 pm EDT

Is Capitalism Compatible with Democracy?

- First Online: 09 March 2018

Cite this chapter

- Wolfgang Merkel 3 , 4

1771 Accesses

2 Citations

Capitalism and democracy follow different logics. During the first postwar decades, tensions between the two were moderated through the sociopolitical embedding of capitalism by an interventionist tax and welfare state. Yet, the financialization of capitalism since the 1980s has broken the precarious capitalist-democratic compromise. Socioeconomic inequality has risen continuously and has transformed directly into political inequality. The lower third of developed societies has retreated silently from political participation; thus its preferences are less represented in parliament and government. Deregulated and globalized markets have seriously inhibited the ability of democratic governments to govern. If these challenges are not met with democratic and economic reforms, democracy may slowly transform into an oligarchy, formally legitimized by general elections. It is not the crisis of capitalism that challenges democracy but its neoliberal triumph.

A first German version was co-authored by Jürgen Kocka in: Wolfgang Merkel (Ed.) Demokratie und Krise (Democracy and Crisis). Wiesbaden, Springer, 2015

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Hall and Soskice, however, only describe two varieties of capitalism that they see represented in the context of the OECD: liberal market economies and coordinated market economies . New hybrid types of Manchester-like state capitalism in China, gangster capitalism in Russia and Ukraine during the 1990s, and crony capitalism in Southeast Asia are not taken into consideration here, since they have emerged outside the context of the OECD.

The labels for this type of capitalism vary: “organized capitalism,” “coordinated capitalism,” “Keynesian welfare state” (KWS), or “Fordism.” We use the first two terms interchangeably and take KWS as a variety of “coordinated capitalism” that is particularly compatible with democracy.

Cf. more extensively, Merkel ( 2004 ).

Such cuts were only moderate in Scandinavia, Germany, Austria, and France but drastic within the context of Anglo-Saxon economies (USA, UK, NZ).

The welfare state and Keynesianism were, of course, developed to different degrees within the OECD countries (Esping-Andersen 1990 ; Hall and Soskice 2001 ).

It is thus even more surprising that neoclassical economics and neoliberal political forces question this relationship. They see political equality fulfilled by the equal availability of political rights (see von Hayek 1978 ; the Free Democratic Party of Germany (FDP) and the liberal political parties in the Netherlands and Scandinavia, respectively).

When asked whether their vote or political participation influence political decision-making, more than two-thirds of lower class citizens in Germany answered in the negative. When confronted with the same question, a resounding two-thirds and more of middle class citizens responded in the affirmative, stating that their voice had an impact (Merkel and Petring 2012 ).

The exclusive character of US democracy becomes even more apparent if the 10–15% of the lower class without citizenship are taken into account. A considerably smaller section of the population (5%) at the upper end of the income scale does not have citizenship (Bonica et al. 2013 , p. 110).

The financial crisis and the bottom-up redistributive effects that have become apparent within the context of the crisis seem nonetheless to have reached social democratic parties. The minimum wage and the effects of deregulation on the financial and labor markets have, after two decades, slowly made their way back to the top of party agendas.

In non-Anglo-Saxon countries, this shift did not happen by cutting back the welfare state but was pushed through by a tax and income policy in favor of business and the better-off.

The US government followed the capitalist rules of a free market more closely when it allowed many more banks to go bankrupt then did European governments.

US democracy is, of course, older than that. But even there universal suffrage for women was introduced only in 1920 (in the UK in 1928, in France in 1945). Until the mid-1960s, six southern US states banned African Americans from voting for racist reasons. Only since that period can the “mother country” of democracy be seen as having fully implemented democratic values.

If one takes full suffrage of men and women as the crucial indicator for a complete democracy, then New Zealand (1900) was the first and Australia one of the first democracies, not the USA or UK.

Bonica, A., McCarty, N., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2013). Why hasn’t democracy slowed rising inequality? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27 (3), 103–124.

Article Google Scholar

Crouch, C. (2004). Post-democracy . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Google Scholar

Crouch, C. (2011). The strange non-death of neo-liberalism . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Enderlein, H. (2013). Das erste Opfer der Krise ist die Demokratie: Wirtschaftspolitik und ihre Legitimation in der Finanzmarktkrise 2008–2013. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 54 , 714–739.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fraenkel, E. (1974[1964]). Deutschland und die westlichen Demokratien (6th ed.). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Freedom House. (2010). Freedom in the world . Accessed January 22, 2014, from http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2010#.Uu_OLrS2yF8

Habermas, J. (1975). Legitimation crisis . Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Hacker, J. S., & Pierson, P. (2010). Winner-take-all politics: How Washington made the rich richer—and turned its back on the middle class . New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of capitalism. The institutional foundation of comparative advantage . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Harvey, D. (2007). A brief history of neoliberalism . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hayek, F. A. V. (1978). Law, legislation and liberty . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Heires, M., & Nölke, A. (2013). Finanzialisierung. In J. Wullweber, A. Graf, & M. Behrens (Eds.), Theorien der Internationalen Politischen Ökonomie (pp. 253–266). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Keane, J. (2011). Monitory democracy? In S. Alonso, J. Keane, & W. Merkel (Eds.), The future of representative democracy (pp. 212–235). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Kitschelt, H. (2001). Politische Konfliktlinien in westlichen Demokratien. Ethnisch-kulturelle und wirtschaftliche Verteilungskonflikte. In W. Heitmeyer & D. Loch (Eds.), Schattenseiten der Globalisierung. Rechtsradikalismus, Rechtspopulismus und separatistischer Regionalismus in westlichen Demokratien (pp. 418–442). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Kocka, J. (2016). Capitalism: A short history . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Korpi, W. (1983). Democratic class struggle . London: Routledge.

Lash, C., & Urry, J. (1987). The end of organized capitalism . Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Lehmann, P., Regel, S., & Schlote, S. (2015). Ungleichheit in der politischen Repräsentation. Ist die Unterschicht schlechter repräsentiert? In W. Merkel (Ed.), Demokratie und Krise. Zum schwierigen Verhältnis von Theorie und Empirie (pp. 157–180). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Lembcke, O. W., Ritzi, C., & Schaal, G. S. (Eds.). (2012). Zeitgenössische Demokratietheorie, Bd. 1: Normative Demokratietheorien . Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Luhmann, N. (1995). Social systems . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Manin, B. (1997). The principles of representative government . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Merkel, W. (2004). Embedded and defective democracies. Democratization, 11 (5), 33–58.

Merkel, W. (2010). Systemtransformation. Eine Einführung in die Theorie und Empirie der Transformationsforschung (2nd ed.). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Merkel, W. (2016). The challenge of capitalism to democracy. Reply to Colin crouch and Wolfgang Streeck. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 10 (1), 61–80.

Merkel, W., Egle, C., Henkes, C., Ostheim, T., & Petring, A. (2006). Die Reformfähigkeit der Sozialdemokratie. Herausforderungen und Bilanz der Regierungspolitik in Westeuropa . Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Merkel, W., & Petring, A. (2012). Politische Partizipation und demokratische Inklusion. In T. Mörschel & C. Krell (Eds.), Demokratie in Deutschland. Zustand—Herausforderungen—Perspektiven (pp. 93–119). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden.

Nölke, A., & Heires, M. (2014). Politik der Finanzialisierung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

O’Connor, J. (1973). The fiscal crisis of the state . London and New York: Routledge.

Offe, C. (1972). Strukturprobleme des kapitalistischen Staates: Aufsätze zur Politischen Soziologie . Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main.

Offe, C. (1984). Contradictions of the welfare state . Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Offe, C. (2003). Herausforderungen der Demokratie . Campus: Frankfurt am Main.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century . Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Polanyi, K. (1944). The great transformation . New York, NY: Rinehart.

Przeworski, A. (1986). Paper stones: A history of electoral socialism . Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Przeworski, A. (2010). Democracy and the limits of self-government . Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Rosa, H. (2012). Weltbeziehungen im Zeitalter der Beschleunigung . Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Rosa, H., & Scheuermann, W. (2009). High-speed society: Social acceleration, power and modernity . Pennsylvania, PA: Penn State University Press.

Rosanvallon, P. (2008). Counter-democracy. Politics in an age of distrust . Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Schäfer, A. (2010). Die Folgen sozialer Ungleichheit für die Demokratie in Westeuropa. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 4 (1), 131–156.

Scharpf, F. W. (2011). Monetary union, fiscal crisis and the preemption of democracy . MPIfG Discussion Paper 11/11. Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung, Köln, July 2011.

Scharpf, F. W. (2012). Kann man den Euro retten ohne Europa zu zerstören? Accessed January 20, 2014, from http://www.mpifg.de/people/fs/documents/pdf/Kann_man_den_Euro_retten_2012.pdf

Scheuermann, W. (2004). Liberal democracy and the social acceleration of time . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Schmitt, C. (1996[1931]). Der Hüter der Verfassung (4th ed.). Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Schmitter, P. C. (1974). Still the century of corporatism. The Review of Politics, 36 , 85–131.

Schmitter, P. C. (1982). Reflections on where the theory of neo-corporatism has gone and where the praxis of neo-corporatism may be going. In G. Lehmbruch & P. C. Schmitter (Eds.), Patterns of corporatist policy-making (pp. 259–279). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Simmerl, G. (2012). Europäische Schuldenkrise als Demokratiekrise. Zur diskursiven Interaktion zwischen Politik und Finanzmarkt. Berliner Debatte Initial, 23 , 108–124.

Soros, G. (1998). The crisis of global capitalism . New York, NY: Public Affairs.

Streeck, W. (2009). Re-forming capitalism. institutional change in the German political economy . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Streeck, W. (2013). Vom DM Nationalismus zum Europatriotismus. Eine Replik auf Jürgen Habermas. Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik, 9 , 75–92.

Streeck, W. (2014). Buying time: The delayed crisis of democratic capitalism . London: Verso.

Walzer, M. (1983). Spheres of justice: A defense of pluralism and equality . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Windolf, P. (Ed.). (2005). Finanzmarkt-Kapitalismus. Analyse zum Wandel von Produktionsregimen . Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Winkler, H. A. (Ed.). (1974). Organisierter Kapitalismus. Voraussetzungen und Anfänge . Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht.

WZB. (2014). Data collection on elections, parties and governments from 1950–2014 .

Zürn, M. (1998). Regieren jenseits des Nationalstaates: Globalisierung und Denationalisierung als Chance . Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Democracy and Democratization, WZB Berlin Social Science Center, Berlin, Germany

Wolfgang Merkel

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wolfgang Merkel .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

WZB Berlin Social Science Center and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

WZB Berlin Social Science Center, Berlin, Germany

Sascha Kneip

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Merkel, W. (2018). Is Capitalism Compatible with Democracy?. In: Merkel, W., Kneip, S. (eds) Democracy and Crisis. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72559-8_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72559-8_11

Published : 09 March 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-72558-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-72559-8

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Steel mill, Youngstown Ohio, 1953. Photo by Library of Congress

Liberalism against capitalism

The work of john rawls shows that liberal values of equality and freedom are fundamentally incompatible with capitalism.

by Colin Bradley + BIO

Completed in 1910, the renaissance revivalist Mahoning County Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio would make any city proud. Its Honduran mahogany, terracotta, 12 marble columns and 40-foot diameter stained-glass dome stand testament to the region’s turn-of-the-century success as a moderate industrial power. Across Market Street, the humbler federal courthouse completed in 1995 invokes a then- au courant corporate office-building style: concrete and panelised stone relieved by blue-black glass, with decorative squares and circles scattered here and there.

The Thomas D Lambros Federal Building and Courthouse is named for Judge Thomas Demetrios Lambros (1930-2019), native son of Ashtabula, Ohio, who in 1967 was appointed to the federal bench by the US president Lyndon B Johnson. The website of the US General Services Administration remembers Judge Lambros as ‘a pioneer in the alternative dispute resolution movement’ – arbitration, as it is generally known. But the people of Youngstown and the Mahoning Valley might remember Judge Lambros for a different reason.

Lambros presided over a fiercely contested lawsuit in 1979-80 filed by 3,500 steelworkers laid off by United States Steel Corporation’s Youngstown Works plant – part of a wave of closures across what we now call the Rust Belt. The lawsuit was an avowedly desperate effort to compel US Steel to sell the company either to the city or else to the workers who, hopefully with federal loans, would continue to operate the plant and keep sending paychecks to the thousands of families depending on them.

In an early hearing, Judge Lambros made a remarkable – revolutionary, almost – suggestion to the workers’ lawyers. They might have a shot if they argued that the people of Youngstown had a ‘community property right’ accrued from the ‘lengthy, long-established relationship between United States Steel, the steel industry as an institution, the community in Youngstown, the people of Mahoning County, and the Mahoning Valley in having given and devoted their lives to this industry’. Because steel production had become such a central part of community life, the judge suggested, the community arguably had a right to decide what happened to the steel mill.

The suit failed. When called upon to issue a ruling in the Youngstown case, Judge Lambros turned on his own suggestion. There just was no precedent in US law to say that the workers or the people really had such a ‘community property right’. Lambros was torn between his moral sense that they should have one, and his professional duty as a judge to find that the law (then as now) recognised no such right. Youngstown Works shuttered for good.

J udge Lambros’s profound ambivalence reflects a contradiction that seems to lie at the heart of liberalism. On the one hand, the promise of a liberal society is of a society of equals – of people who are equally entitled and empowered to make decisions about their own lives, and who are equal participants in the collective governance of that society. Liberalism professes to achieve this by protecting liberties. Some of these are personal liberties. I get to decide how to style my hair, which religion to profess, what I say or don’t say, which groups I join, and what I do with my own property. Some of these liberties are political: I should have the same chance as anyone else to influence the direction of our society and government by voting, joining political parties, marching and demonstrating, standing for office, writing op-eds, or organising support for causes or candidates.

On the other hand, liberalism is usually uttered in the same breath as capitalism. Capitalism is a social system characterised by the fact that private persons (or legal entities like corporations) own the means of production. Combined with liberalism’s protection of rights and liberties, this means that, just as I get to decide what to do with what I own (a 2004 Hyundai with a busted A/C unit and squeaky wheel bearings), so did the legal entity US Steel get to decide what to do with what it owned: the Youngstown Works.

Liberalism’s apparent commitment to capitalism threatens to prevent it from delivering on all that it promises. To see this, it is important to remember that formal political processes do not exhaust the way our society governs itself. One of the main tasks for a society is to organise economic production. We humans are a species that makes stuff. We make tools, dwellings, food, art, culture, more little humans, and much else. Moreover, we usually do this together, as a joint activity. Such cooperative production inevitably produces a division of labour: some hunt while others gather; some fish while others sow; some design artificial intelligence while others squeegee windows at the stop light.

When societies industrialise, achieving economies of scale and the capacity to purchase cutting-edge technologies needed for profitable production becomes extremely expensive. So expensive, in fact, that it is possible only for a relatively small number of people or entities to do it. This leads not just to a division of labour, but to a class-stratified society. Some people – capitalists – own the materials or technologies that produce society’s wealth, while other people – workers – have to work for the capitalists in exchange for a wage. In such a class-stratified society, capitalists not only make the important investment decisions that guide society’s overall direction, but they are also effectively private dictators telling their workers what to do, when to do it, what to wear, when to pee, and what to post online. Given liberalism’s defence of the capitalists’ rights to do all this, it is hard to see how liberalism might reliably achieve its goal of bringing about a society of equals in which we all have a share in our collective governance. Hence the contradiction at its heart, and Judge Lambros’s ambivalence.

Liberals rarely question the basics of political economy like who owns what and lords it over whom

The political-economic background of the Youngstown closure is an object of ongoing controversy among historians, economists and sociologists. All agree that it was part of the phenomenon of ‘globalisation’. But whereas the former US president Bill Clinton – whose administration oversaw the construction of the Lambros Federal Building – could declare in 2000 that globalisation was ‘the economic equivalent of a force of nature’, nobody seriously believes that anymore. Under US leadership (itself a response to Chinese rivalry), the world is turning toward ‘neomercantilism’, embracing strategies whereby governments protect domestic industries while intervening mightily in markets, imposing carrots and sticks to steer private investors toward targeted economic goals like place-based investments in green technology.

This means that the way society organises production has re-emerged as a contested political issue. But it does so in a fractured ideological moment. Liberalism’s hegemony is perhaps at a nadir. Populist authoritarians and ‘illiberal democrats’ have attracted a surprising level of legitimacy and support, while post-liberal ideologies look ahead to new possibilities. Critics on the Left and the Right offer two main visons of the near-future. On the Left, critics suspect that the return of industrial policy might be less than the ‘new economic world order’ its proponents tout it to be, reflecting liberalism’s inability to get to the root of capitalism’s problems. Those who hold this view, like the economist Daniela Gabor, see legislative efforts like the US president Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) or the European industrial policy proposed by the French president Emmanuel Macron as merely underwriting private profit-making by using the state to ‘de-risk’ some capital investments, making them safer for capitalists who reap massive rewards with little downside. Some socialists even go so far as to suggest that Biden’s IRA is a regression to a kind of feudalism. On the Right, some so-called post-liberals, like the political theorist Patrick Deneen, hope that an industrial policy focused on restoring blue-collar manufacturing jobs to the US heartland will turn out to be a revolutionary first step toward throwing out liberalism with all its (hypocritical) aspirations for individual liberties and social equality.

This dichotomy ignores the possibility of a liberal anticapitalism . This may sound like an oxymoron. Neither liberals nor their critics disentangle liberalism from capitalism (though some historians have begun to). Most liberals even emphasise the happy marriage between the two. Among those liberal egalitarians who stress the redistributive New Deal as liberalism’s moral core, few seriously grapple with big issues of political economy. Liberals advance institutional and procedural solutions – ‘structural change’ to representative processes, expanding voting access, etc – but rarely question the basics of political economy like who owns what and lords it over whom.

That makes it all the more surprising that liberalism’s greatest philosophical exponent, John Rawls, developed a sustained, systematic and principled argument that even the most humane, welfarist form of capitalism is incompatible with the possibility of achieving liberalism’s deepest aim: free people living together in a society of equals. These arguments should be much better known.

Contrary to a common caricature of his views, Rawls does not reduce politics to technocratic nudges and tinkering with marginal tax rates. Liberalism is a philosophy of the ‘basic structure’ of society. The basic structure includes a society’s fundamental institutions: not only political structures like constitutions (where they exist), but also markets and property rights. Everything is up for moral assessment, not just considered abstractly, but with respect to how different institutions interact with one another and with ordinary human behaviour, over the course of generations.

‘Everything’ here includes the basics of political economy like who makes what and who owns what, and who decides. Crucially, for Rawls, this includes the way society organises the production of goods and services. Focusing on the inequalities and domination that arise from the way capitalism empowers a small group to control how we produce society’s wealth, Rawls argues that no form of capitalism can ever cohere with the liberal ideal of a society of equals. Social equality and basic liberties will always be thwarted by it.

Rawls’s corpus is complex and contested. But we don’t need to agree with him on everything. Even if we ditch the larger Rawlsian apparatus and the many tweaks he made on particular topics after the publication of A Theory of Justice (1971), he stated the core of a liberal, anticapitalist political economy, and never abandoned the conviction that a liberal society must overcome capitalism.

F or Rawls, liberalism revolves around two ideals: society as a fair system of cooperation, and people as free, equal, capable of acts of joy, kindness and creativity; and disposed – if not always without reluctance – to cooperate with one another to flourish. Rawls shows that these ideals lead to principles that we can appeal to in designing, improving and maintaining our basic political and economic structures.

Capitalism is an economic system with three features. First, Rawls said it is a ‘social system based on private property in the means of production’. It allows almost unfettered private ownership of not only personal property, but also the highly valuable and productive industrial and financial assets of a society – what Vladimir Lenin in 1922 called the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy. Second, it allocates access to private property primarily via markets. This includes markets in goods, markets in financial products, and markets in labour. That leads to the third feature: most people – workers – try to earn enough to support themselves or their families by selling their labour for a wage to a capitalist who owns the means of production.

As a result of this, capitalism is an economic system that produces a class-based society and division of labour. This is what Rawls’s liberal anticapitalism targets, focusing on the obstacles that a class-stratified society of owner-capitalists and workers poses to a genuinely cooperative and emancipatory liberal society. Rawls argues that capitalism violates two core tenets of liberalism: the principles of social equality, and of extensive political liberty. Moreover, reforms that leave the capitalist core in place are unlikely to be stable. Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Social equality

One component of social equality is fair equality of opportunity. Your chances at attaining or succeeding in any valued role should not depend on aspects of your birth or circumstance over which you had little or no control. All current societies fail to meet this: race, gender, religion, disability, sexuality and other circumstances favour the chances of some over others. Likewise, in a class-stratified capitalist society, whether you or your parents own productive assets significantly determines your life chances. So, fair equality of opportunity is unlikely under capitalism. I say ‘unlikely’ because it is possible that a capitalist welfare state could promote equal opportunity by investing heavily in education and healthcare.

But even a society that fulfilled equal opportunity would still fall short of the full ideal of liberal equality. More difficult to specify but infinitely more powerful than equal opportunity is the value Rawls called ‘reciprocity’. This is the idea that it matters that we are, are seen by others as, and see ourselves as, fully participating members of society, on equal footing and status with other participants. Capitalism makes reciprocity impossible because it requires a division of labour that prises apart the ‘social roles and aims of capitalists and workers’. Consequently, Rawls said, ‘in a capitalist social system, it is the capitalists who, individually and in competition with one another, make society’s decisions’ about how to invest its resources and what and how to produce. This makes it hard for workers to see themselves as active participants in directing society because, well, they aren’t (with the limited exception of voting in a ballot every few years).

Capitalist make important decisions on behalf of society, yet their interests diverge from those of the working class

This is what the people of Youngstown learned when the owners of US Steel decided to move the factory away. Likewise, today the CEO of McDonald’s can tell his employees that ‘we’re all in this together’ until he’s blue in the face, even though he gets more than 1,150 times what they do per hour and makes all the decisions about how they spend their time. When this is true, ‘society’ simply feels like something we are ‘caught in’ rather than something we are making and sustaining together, Rawls wrote in Political Liberalism (1993).

Such capitalists make important decisions on behalf of society, yet their interests diverge from the interests of the working class. This is a form of social domination. Rawls worried that those who do not own the means of production will be ‘viewed both by themselves and by others as inferior’ and will likely develop ‘attitudes of deference and servility’ while the owners grow accustomed to a ‘will to dominate’. This conflicts with a true ‘social bond’ between equals, which calls on us to make a ‘public political commitment to preserve the conditions their equal relation requires’, as he wrote in Justice as Fairness: A Restatement (2001).

Political liberty

Capitalism is also inconsistent with the basic liberal value of political liberty. Political scientists have been arguing for some time that advanced democracies like the United States and Western Europe are probably better characterised as oligarchies, since their policies bear almost no relation to the interests of the poor when these deviate from those of the wealthy. The usual suggested solution is to ‘get money out of politics’ by reforming campaign finance rules.

But the Youngstown Works story suggests something even deeper. The steelworkers actually enjoyed considerable political support in their fight. They were represented by President Johnson’s former attorney general, Ramsey Clark. Meanwhile, the Youngstown City Council, the Ohio State Legislature, and the US House Committee on Ways and Means all took some action on their behalf. But, as Judge Lambros finally conceded, none of these were a match for the power of capital.

Anticipating the economist Thomas Piketty’s claim in Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013) that capitalist societies ‘drift toward oligarchy’, Rawls argued that economic and political inequality ‘tend to go hand in hand’, and this fact encourages the wealthy to ‘enact a system of law and property ensuring their dominant position, not only in politics, but throughout the economy’. The wealthy use their dominant position to set the legislative and regulatory agendas, monopolise public conversation, hold political decision-making hostage by threatening capital flight, and engage in outright corruption. Reforming campaign finance rules to keep money out of politics is perhaps an important start in curbing this tendency. But it’s just a start.

Rawls was sensitive to Karl Marx’s criticism that liberal rights might be empty or merely formal – naming protections without really providing them. In response, Rawls insisted that rights to political participation must be given ‘fair value’. In A Theory of Justice , he observed that the full policies needed to protect political liberty ‘never seem to have been seriously entertained’ in capitalist societies. The reason is that the conversion of economic inequality to political domination happens quickly . ‘Political power rapidly accumulates’ when property holdings are unequal, and the ‘inequities in the economic and social system may soon undermine whatever political equality might have existed’. Ensuring political liberty therefore requires us not just to restrict the use of money in politics but, in Rawls’s words, ‘to prevent excessive concentrations of property and wealth’ in the first place.

Altering property rights goes near the heart of capital’s power

As Piketty and his colleagues have shown, today’s stupefying level of inequality has two primary sources: massive income inequality aided by lower top-marginal tax rates, and a high rate of return on capital compared with returns on labour. Compound interest for the rich keeps making the rich richer as the poor get relatively poorer. Rawls argued we need to address both: the first via taxation and wage controls, and the second by altering the ‘legal definition of property rights’.

It is easy to overlook how radical this latter proposal is. As the legal scholar Katharina Pistor has shown in The Code of Capital (2019), capitalism relies on the legal definition of property rights. Not all property rights accumulate at the rapid rate of capital, nor confer on their owners as much control over other people. Altering property rights therefore goes near the heart of capital’s power. This could take the form of recognising ‘community property rights’ of the sort that Judge Lambros suggested and then backed off from. Or it could involve separating the capitalists’ ownership rights over factory equipment, say, from the rights to manage how that equipment gets used, reserving the latter rights for the workers who actually use it. Liberalism may protect property of some kind, but not necessarily give the turbocharged property rights that capitalists enjoy today.

But can’t we just reform capitalism piecemeal along social-democratic lines to alleviate these problems? Rawls says no: reformed capitalism would just swiftly revert back to inequality and domination. This is the problem of instability. We must ask of any proposed regime, like a reformed welfare-state capitalism, whether it ‘generates political and economic forces that make it depart all too widely from its ideal institutional description’. To assess a conception of justice or an institutional arrangement intended to satisfy it, we need to consider how the political, social, psychological and economic dynamics it is likely to foster will play out over time.

Central to Rawls’s understanding of stability was Marx’s observation in ‘On the Jewish Question’ (1844) that ‘while ideally politics takes precedence over money’, under capitalism, ‘in fact politics has become the servant of money’. It’s not enough to recognise some domain as ‘political’ and to try to summon the ‘political will’ to change it. Political power – the legislative and policymaking power of the state – cannot simply achieve anything it desires. It is constrained by, among other things, the power of capital. It is vital to understand how the dynamics of capital ownership may thwart proposed political interventions. Many of these are familiar: the regulatory race to the bottom fuelled by the threat of capital flight; ‘market discipline’; creditors imposing austerity and structural adjustment on not-so-sovereign nations.

Rawls had little to say about how social organising might challenge capital’s political hegemony, and here perhaps most of all we must look elsewhere for guidance. But he understood that, so long as capital reigns, liberal politics is doomed to be ineffective. Any exertion of political will that leaves in place the political economic core of capitalism will preserve a class-stratified society based on the unequal ownership of the means of production and a destabilising and demeaning division of labour.

A t this point, one might wonder how useful all this abstract moral criticism of capitalism really is. On the Right, some may dismiss it as otiose since there is no serious alternative to capitalism, and anyway these moral criticisms haven’t acknowledged capitalism’s primary advantage: its productivity and ability to make more stuff for more people. On the Left, some may suspect that abstract political philosophising is perhaps interesting, but ultimately useless – like a Fabergé egg, as the Marxist political theorist William Clare Roberts described Rawls’s theory: beautiful, well-crafted, but ultimately useless. Capitalism won’t be overcome by convincing ourselves that it is unjust: that requires revolutionary action.

But as advocates of ‘moral economy’, including the legal scholars associated with the Law and Political Economy project acknowledge, there is an important role for moral criticism of political economy of the type that Rawls and others have furnished. This can provide clarity and focus. Especially when empirical information about economic trends is noisy, moral critique provides a kind of compass.

This leaves the question what liberal anticapitalism looks like. Rawls thought there were two, possibly just, types of regime. One, a ‘property-owning democracy’, allows private ownership of the means of production, but only on the condition that private capital is held in roughly equal shares by everyone, preventing the emergence of a significant split between classes of owners and non-owners. This requires hefty wealth and inheritance taxes to spread out ownership of productive assets, and a background welfare state to ensure robust ‘human capital’ by providing both education and healthcare.

Rawls’s liberal critique of capitalism leaves us not with a silver bullet, but with a moral compass and an agenda

The other type of just regime is liberal, or market, socialism. Under market socialism, the state controls the economy overall, but worker-managed firms are left to compete in a closely monitored and adjusted market. This is an attempt to harness the allocative efficiencies of markets and the price mechanism within a socialist system that democratises major investment decisions and prevents private accumulation of significant wealth. Rawls saw in the actually existing socialist states of the 20th century an intolerable absence of political liberty. This is why he insisted that a just socialism would be liberal and should to large extent rely on markets rather than central planning.

But the liberal critique of capitalism that Rawls developed in his later work gives us reasons to be wary still of either of these alternative regimes. It is reasonable to fear, for instance, that markets will simply reproduce the destabilising dynamics Rawls himself identified, as Marx had before him. The Marxist philosopher G A Cohen might well have been right when he declared in Why Not Socialism? (2009) that ‘[e]very market, even a socialist market, is a system of predation.’

This is where Rawls’s liberal critique of capitalism leaves us. Not with a silver bullet, but with a moral compass and an agenda. His critique leaves out some important things. Notably, he had little to say about race and ignored the dynamics of ‘racial capitalism’. No reckoning with capitalism is complete without this dimension. Nevertheless, he helped illuminate the important fact that what we need, and many of us want, are decentralised, cooperative forms of economic production that are consistent with the core liberal values of social equality and basic liberties. But we’ve yet to discover at scale how to have this cake and eat it. Rawls’s work provides little help on this, but fortunately we do not need to rely on his theoretical and philosophical approach in isolation. Here we can turn to social science and to the countless examples of activists and visionaries – from Jackson, Mississippi to Preston, England – developing participatory economics, community wealth-building, and other new and richer forms of what the political theorist Bernard Harcourt today calls ‘coöperism’.

These social experiments are continuations of the efforts of the people of Youngstown in 1980 to claim a right to make decisions about the management of the factory that sustained that community and was sustained by the labour of the steelworkers who operated it, and the women who supported them. These are among small-scale efforts that give us some reason to hope for a more equal and socially just world.

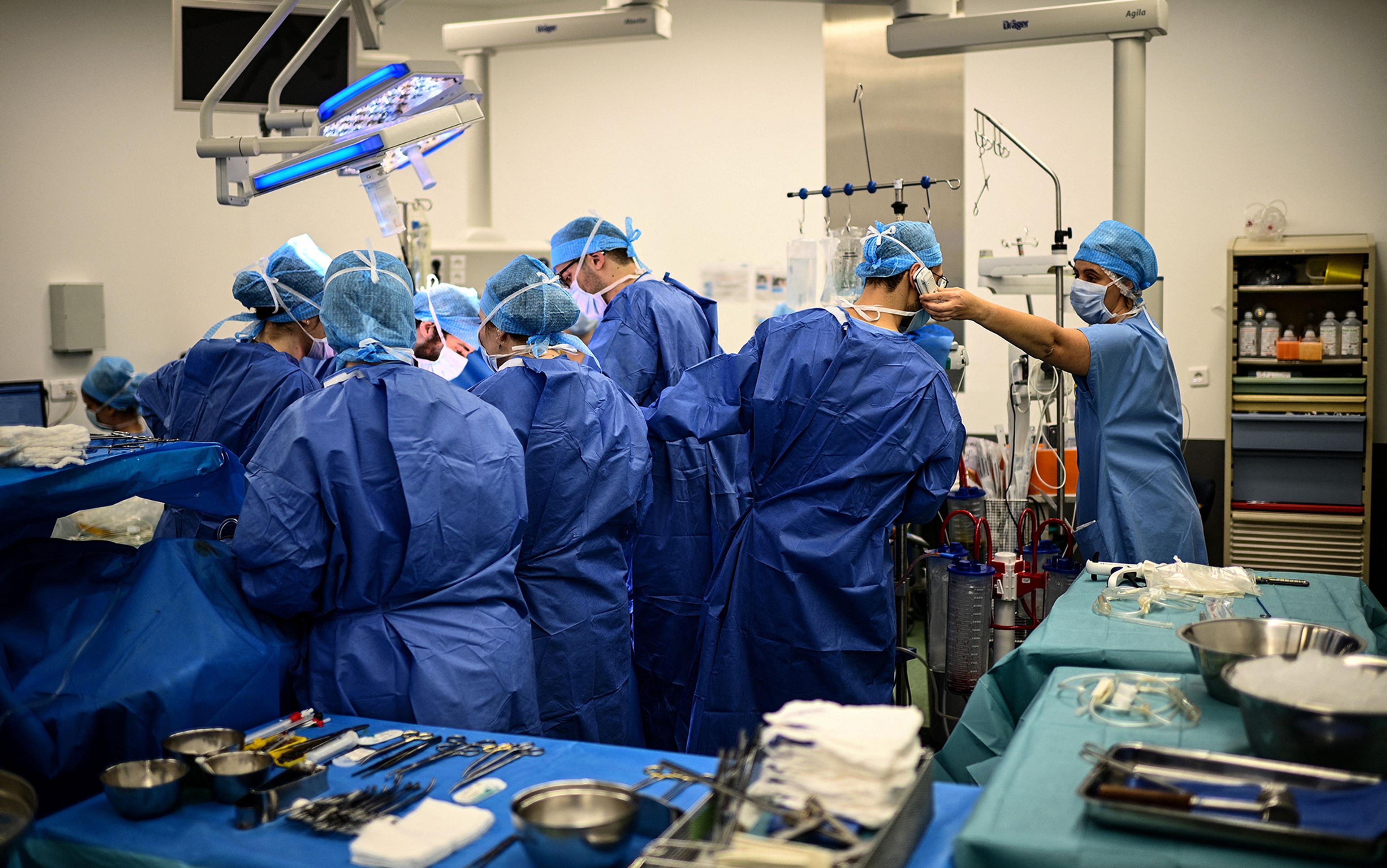

Last hours of an organ donor

In the liminal time when the brain is dead but organs are kept alive, there is an urgent tenderness to medical care

Ronald W Dworkin

Stories and literature

Do liberal arts liberate?

In Jack London’s novel, Martin Eden personifies debates still raging over the role and purpose of education in American life

History of ideas

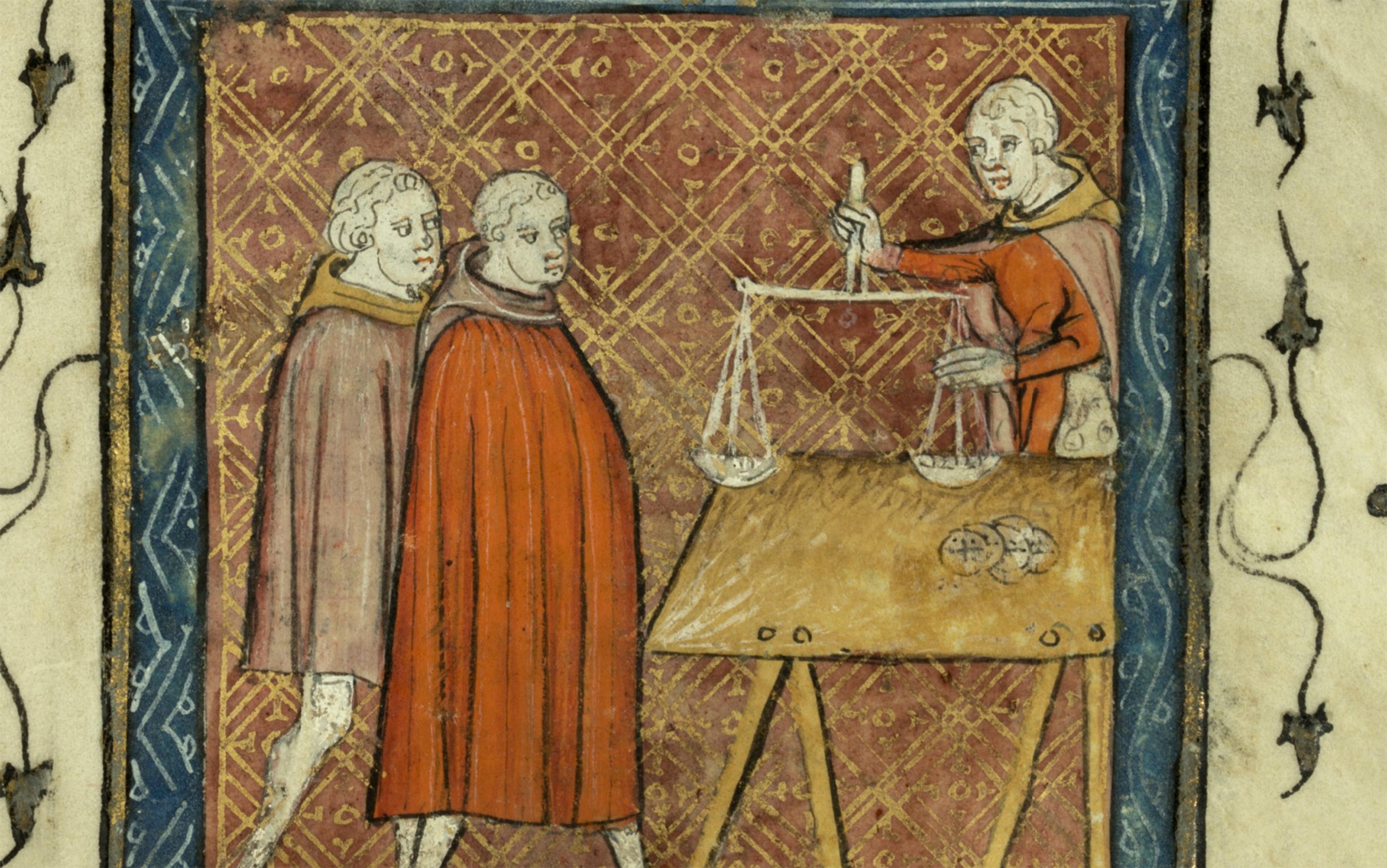

Reimagining balance

In the Middle Ages, a new sense of balance fundamentally altered our understanding of nature and society

What would Thucydides say?

In constantly reaching for past parallels to explain our peculiar times we miss the real lessons of the master historian

Mark Fisher

The environment

Emergency action

Could civil disobedience be morally obligatory in a society on a collision course with climate catastrophe?

Rupert Read

Metaphysics

The enchanted vision

Love is much more than a mere emotion or moral ideal. It imbues the world itself and we should learn to move with its power

Mark Vernon

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Is capitalism compatible with democracy?

2014, Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft

Related Papers

The relationship between capitalism and democracy is one that deserves serious scholarship and attention because both terms have come to represent modernity generally, and the 20 th century more specifically. The purpose of this essay is to understand how capitalism and democracy relate to each other, and whether or not democracy can be shown to be antagonistic to capitalism. In other words, the central question driving this essay is to expose whether or not there is a way to conceptualize democracy or political action that would lead to the demise of capitalism. I propose to proceed by dividing this essay into three sections: the first part is a brief sketch of how the inseparable association of capitalism and democracy is a historical construction of the last century, the second part will discuss in what ways and to what degree democracy has been changed by capitalism in order to render it impotent as a resistive force, and the third part will analyse whether or not democracy still holds the potential to bring about the end of capitalism. Section 1

This chapter reviews some theories about the relation between capitalism and democracy. This is a large question and no attempt is made to examine all possible aspects of the relation nor to consider any single aspect in all its detail. Instead I will focus on four concerns: (a) the degree of association between capitalism and democracy, (b) the major determinants or causes of that association, (c) the effects of democratic forms on political class struggle, and (d) future developments in the capitalist state. In each case I present some relevant views advanced by other theorists and comment on them. The chapter concludes with some more general theoretical reflections on the nature of state power in capitalist societies.

Review of Radical Political Economics 50(4) pp. 793-809. (2018)

Annamaria Artner

Adrian Pabst

António Varella Cid

piergiuseppe fortunato

This paper provides a theory to explain why in di¤erent historical experiences di¤erent coalition of social groups have been at the hearth of the democratization process. This issue is addressed using an occupational choice model were four di¤erent social groups interact. As time goes, the capital accumulation process leads to changes in both the composition of society and the labor market equilibrium. In turn, these changes a¤ect the interests of the di¤erent groups and leads to the formation of various possible coalitions in support of democratization.

corey dolgon

Since 1989, due to historical developments and the works of theorists such as Francis Fukuyama, authoritative sources have claimed that the combination of a “free market economy” and “liberal democracy built on equal rights” results in the most developed form of human society. Taking into consideration that development is driven by contradictions, the above premise is true if it is accepted that no contradictions exist within or between a free market economy and liberal democracy. If, however, such contradictions do exist, the potential development of human society cannot be said to ultimately conclude with capitalism. Therefore, democratic capitalism may be the most developed and final form of capitalism, but not that of human society in general. This essay aims to clarify the meanings of free market and democracy, and their relationship. Based on the general and specific definitions of democracy, it distinguishes between the concepts of de jure and de facto equality, and analyses the impact of the most important working mechanism of a market economy – competition – on manifold inequalities. It discusses the real inequalities manifested in income and the ownership of the means of production, and also the inequalities within capital, and between capital and wage labour. By reflecting upon these inequalities, the study looks at how free market forces work towards the erosion of democracy and constrain the practical utilization of democratic institutions.

Culture, Practice & Europeanization

Hauke Brunkhorst

The great challenge of our time is not a clash of civilizations, as many advocated since Samuel Huntington published The Clash of Civilizations. Nor is the world most important challenge the revival of the Cold War in the form of a renewed US-Russia confrontation or in the forms of the evils of unconventional war that the US calls “terrorism”, a generic term governments use to label any opponent terrorist. These issues are manufactured and symptomatic of capitalist countries engaged in an intense world competition for markets and raw materials. This is not very different from the world power structure during the Age of New Imperialism, 1870-1914. The great challenge of our time is social and geographic inequality that threatens not only the system of capitalism creating inequality, but the democratic political regime under which capitalism has thrived in the last one hundred years.

RELATED PAPERS

Sally Driml

Hassan Azhdari Zarmehri

Justyna Wietecha

pınar çelik

SIMPÓSIO NACIONAL DE SISTEMAS PREDIAIS

Douglas Barreto

Luis Erneta Altarriba

The Gerontologist

Shelly Chadha

IDOSR JOURNAL OF COMPUTER AND APPLIED SCIENCES

KIU Publication Extension

Toxicological Review

Nikolay Goncharov

International Journal of Neuroscience

Mohammad Zare

Emerging Markets: Finance eJournal

Sunduzwayo Madise

Peter Delobelle

Shanelle Foster

2015 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition Proceedings

Alina Ilyasova

Annabelle Solomon

Review of Scientific Instruments

ettore majorana

Ulrike Eberle

Nuclear Technology

carlos guerra

Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine

Sotirios Korossis

Journal of Vascular Surgery

andris kazmers

African Journal of Agricultural Research

Teshome Derso

The Journal of Urology

Peter fabri

Fluid Phase Equilibria

Alicia Cases

Ngọc Anh Phạm

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

Supported by

Critic’s Notebook

Is the Marriage Between Democracy and Capitalism on the Rocks?

Never easy, the relationship between the vaunted political system and economic order appears to be in crisis. New books by historians and economists sound the alarm.

- Share full article

By Jennifer Szalai

The documentary series “Free to Choose,” which aired on public television in 1980 and was hosted by the libertarian economist Milton Friedman, makes for surreal watching nowadays. Even if Ronald Reagan would go on to win the presidential election later that year, it was still a time when capitalism’s most enthusiastic supporters evidently felt the need to win the public over to a vision of free markets and minimal government. Today’s billionaire donors may be able to funnel money to their favored candidates without even bothering to pay lip service to American democracy, but the corporate funders of “Free to Choose” set out to make their case.

They had an enormous audience: The 15 million viewers who watched the first episode saw an avuncular Friedman (diminutive and smiling), leaning casually against a chair in a Chinatown sweatshop (noisy and crowded), surrounded by women pushing fabric through clattering sewing machines. “They are like my mother,” Friedman said, gesturing at the Asian women in the room. She had worked in a factory too, after immigrating as a 14-year-old from Austria-Hungary in the late 19th century. Friedman explained that these low-wage garment workers weren’t being exploited; they were gaining a foothold in the American land of plenty. The camera then cut to a tray of juicy steaks.

Friedman may have been happy to do his part to try to persuade the masses, but he didn’t put too much stock in democracy. He notoriously offered economic advice to the Chilean military dictator Augusto Pinochet that amounted to a brutal program of austerity. In 1967, at the height of the civil rights movement, Friedman argued that any progress made by Black Americans had to do with “the opportunities offered them by a market system” (instead of “legislative measures” that only encouraged “unrealistic and extravagant expectations”). What Friedman believed in was capitalism, or what he called “economic freedom.” Political freedom might come — but capitalism, he said, could do just fine without it.

Not so, insists Martin Wolf in his new book, “ The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism .” “Capitalism cannot survive in the long run without a democratic polity, and democracy cannot survive in the long run without a market economy,” he writes. Capitalism supplies democracy with resources, while democracy supplies capitalism with legitimacy. Wolf, the chief economics commentator for The Financial Times, worries that after an efflorescence of democratic capitalism, “that delicate flower” is beginning to wither. Most of his ire is directed at an unhinged financial system that has encouraged a “rentier capitalism” and a “rigged” economy.”

Wolf is hardly alone in noticing that the relationship between democracy and capitalism has gone haywire. He and other observers are trying to make sense of what might happen next — and, befitting our current bewilderment, they offer a range of perspectives. Some, like Wolf, hope the relationship can be repaired; others argue that the pairing has always been fraught, if not impossible.

In Wolf’s case, his anguished tone reflects the scale of his own disillusionment. Born in 1946 in postwar England, he recalls in his preface how “the world seemed solid as I grew up.” He describes the feelings of “confidence” in democracy and capitalism that flourished with the collapse of the Soviet Union. But he has also read his Marx and Engels, looking askance at their solutions while commending them for how “brilliantly” they described capitalism’s relentlessness and omnivorousness. Left to its own devices, capitalism expands wherever it can, plowing its way through national boundaries and local traditions — making it marvelously dynamic or utterly ruinous, and not infrequently both.

Yet the “democratic capitalism” that Wolf wants to preserve was, even by his own lights, short-lived. Democracy itself — or “liberal democracy” with universal suffrage, which Wolf says is the kind of democracy he means — is a “political mayfly.” Democratic capitalism ended, in his account, with the financial crisis of 2008. The former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich has offered another measure, arguing that democratic capitalism, at least in the United States, began with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and ended with Reagan, when “corporate capitalism” took over. (There’s also an argument to be made that true democracy in the United States began only with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 .) Reich and Wolf share a deep sense of crisis, along with the adamant conviction that democratic capitalism can and should be revived.

Capitalism expands wherever it can, plowing its way through national boundaries and local traditions — making it marvelously dynamic or utterly ruinous, and not infrequently both.

The left-wing German sociologist Wolfgang Streeck stakes out a decidedly different position, suggesting that the tendency to equate “democratic capitalism” with a few decades of postwar plenty is to misinterpret a “historical compromise between a then uniquely powerful working class and an equally uniquely weakened capitalist class.” In “How Will Capitalism End?” (2016), Streeck argues that it’s not compromise but the cascade of crises following the postwar boom — inflation, unemployment, market crashes — “that represents the normal condition of democratic capitalism.” Where Wolf wistfully invokes a “delicate flower,” Streeck writes contemptuously of a “shotgun marriage.”

Less than a decade ago, Streeck sounded like a fringe Savonarola; in 2014, he published “Buying Time,” declaring he was sure that the end of democratic capitalism was nigh. When an idea that once seemed preposterous starts to look prescient, we know that something fundamental has changed.

It’s a transformation that the historian Gary Gerstle explores in his fascinating and incisive “The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order” (2022). Before the New Deal order started to falter in the late 1960s and ’70s, Gerstle writes, a majority of Americans believed that capitalism should be managed by a strong state; in the neoliberal order that followed, a majority of Americans believed that the state should be constrained by free markets. Each order began to break down when its traditional ways of solving problems didn’t seem to work. Both the New Deal and its neoliberal successor took for granted that democracy and capitalism were compatible; if these books are any indication, that mainstream assumption — and even the notion of a mainstream assumption — is in tatters.

Democracy might be imperiled, but capitalism, according to Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, has obtained the status of civic religion. In “ The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market ,” the authors argue that industry groups and wealthy donors have engaged in a concerted campaign to promote “market fundamentalism” — “a vision of growth and innovation by unfettered markets where government just gets out of the way.”

Oreskes and Conway are perhaps best known for “ Merchants of Doubt ” (2010), which detailed corporate-funded efforts to protect the tobacco industry and promote climate-change denial by depicting settled science as “unsettled.” They describe their new book as a sequel of sorts — an attempt to understand the ideology that animated the figures in “Merchants,” whose terror of government regulation was so extreme that they equated environmental protections with communist tyranny.

But instead of sowing doubt, what the figures in this new book are peddling is certainty: the iffy “science” of laissez-faire economics dressed up as indisputable fact. Oreskes and Conway are historians of science, and they do an impressive job of uncovering the resources that groups like the National Association of Manufacturers and the Foundation for Economic Education put into spreading the (greed is good) word.

The main implication of “The Big Myth” seems to be that “market fundamentalism” is so horrifically egregious — enriching the few and despoiling the planet — that Americans had to be plied with propaganda to believe in it. But as Gerstle’s book shows, neoliberal ideas proved so seductive because they also happened to dovetail with the stories that Americans wanted to tell about themselves, emphasizing individuality and freedom.

Such popular support is crucial in a democracy, of course, but in “Globalists” (2018) the historian Quinn Slobodian argues that neoliberals have found ways not just to liberate markets but to “encase” them in international institutions, thereby shielding capitalist activities from democratic accountability. He observes that neoliberals were especially alarmed after World War II by decolonization, adopting a condescending “racialized language” that pitted “the rational West,” with its trade rules and property laws, against a postcolonial South, “with its ‘emotional’ commitment to sovereignty.”

Slobodian’s excellent if discomfiting new book, “ Crack-Up Capitalism ” (forthcoming in April), explores other neoliberal evasions of the nation-state: tax havens, special economic zones, gated communities — enclaves that are “freed from ordinary forms of regulation.” A new generation of swashbuckling billionaires entertain the prospect of secession, using their money to realize fantasies of escape, whether through seasteading or spaceships . The book quotes one seasteading enthusiast declaring, “Democracy is not the answer,” but merely “the current industry standard.” That person was Patri Friedman , Milton’s grandson.

Still, as much as a rarefied class might try to live in a realm beyond democracy, Slobodian says that even the most fantastical capitalist projects require a demos to function. Tech billionaires might be trying to create a world where the plebes — with their pesky demands for secure working conditions and a living wage — will be replaced by indefatigable robots that don’t have to eat anything at all (let alone a tray of juicy steaks). But for now essential workers are still humans.

“The waged service class is the easiest for the visionaries to forget and the hardest for them to live without,” Slobodian writes. “The cloud floats because the underclass holds it up. Time will tell if they drop their arms one day and make something new.”

An earlier version of this article misstated the name of one of the organizations that promoted the idea of free markets in the United States. It is the Foundation for Economic Education, not the Foundation for Economic Freedom.

How we handle corrections

Jennifer Szalai is the nonfiction book critic for The Times. More about Jennifer Szalai

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

As book bans have surged in Florida, the novelist Lauren Groff has opened a bookstore called The Lynx, a hub for author readings, book club gatherings and workshops , where banned titles are prominently displayed.

Eighteen books were recognized as winners or finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, in the categories of history, memoir, poetry, general nonfiction, fiction and biography, which had two winners. Here’s a full list of the winners .

Montreal is a city as appealing for its beauty as for its shadows. Here, t he novelist Mona Awad recommends books that are “both dreamy and uncompromising.”

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30 , yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Capitalism vs. Democracy

What's the difference.

Capitalism and democracy are two distinct systems that often coexist in modern societies. Capitalism is an economic system that emphasizes private ownership, free markets, and profit-driven production. It allows individuals and businesses to pursue their economic interests with minimal government intervention. On the other hand, democracy is a political system that emphasizes the participation of citizens in decision-making processes and the protection of individual rights and freedoms. While capitalism focuses on economic aspects, democracy focuses on political aspects, ensuring that power is distributed among the people. Both systems promote individual freedom and choice, but they operate in different spheres and serve different purposes.

Further Detail

Introduction.

Capitalism and democracy are two distinct systems that have shaped the modern world in profound ways. While capitalism primarily focuses on economic organization and the distribution of wealth, democracy pertains to political governance and the participation of citizens in decision-making processes. Both systems have their own unique attributes and impacts on society. In this article, we will explore and compare the key characteristics of capitalism and democracy, shedding light on their strengths, weaknesses, and the potential synergies that can arise when they coexist.

Capitalism is an economic system characterized by private ownership of resources and the means of production, driven by profit motives and market competition. It emphasizes individual freedom, entrepreneurship, and the pursuit of self-interest. In a capitalist society, prices and production are determined by supply and demand, and the market plays a central role in allocating resources.

One of the key attributes of capitalism is its ability to foster innovation and economic growth. The profit motive incentivizes individuals and businesses to develop new products, services, and technologies, leading to increased productivity and overall prosperity. Capitalism also provides individuals with the freedom to choose their occupations and pursue economic opportunities, which can lead to upward social mobility and the accumulation of wealth.