- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, understanding difficulties and resulting confusion in learning: an integrative review.

- 1 Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2 School of Education, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD, Australia

- 3 University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4 Department of Educational Studies, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 5 College of Education, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, United States

Difficulties are often an unavoidable but important part of the learning process. This seems particularly so for complex conceptual learning. Challenges in the learning process are however, particularly difficult to detect and respond to in educational environments where growing class sizes and the increased use of digital technologies mean that teachers are unable to provide nuanced and personalized feedback and support to help students overcome their difficulties. Individual differences, the specifics of the learning activity, and the difficulty of giving individual feedback in large classes and digital environments all add to the challenge of responding to student difficulties and confusion. In this integrative review, we aim to explore difficulties and resulting emotional responses in learning. We will review the primary principles of cognitive disequilibrium and contrast these principles with work on desirable difficulties, productive failure, impasse driven learning, and pure discovery-based learning. We conclude with a theoretical model of the zones of optimal and sub-optimal confusion as a way of conceptualizing the parameters of productive and non-productive difficulties experienced by students while they learn.

Introduction

As class sizes in education are increasing and technology is impacting on education at all levels, these trends create significant challenges for teachers as they attempt to support individual students. Technology undoubtedly provides substantial advantages for students, enabling them to access information from around the planet easily and at any time. The advantages and disadvantages of the increased use of technology have come to light over time as students increasingly engage with new innovations. In this review, we will address an issue that has become progressively evident in digital learning environments but is relevant to all educational settings, particularly as class sizes grow. We will explore the difficulties in attempting to understand and account for the struggles students experience while learning a particular emphasis on what happens when students experience difficulties and become confused.

Running into problems while learning is often accompanied by an emotional response. Emotion, more broadly, plays a vital role in the integration of new knowledge with prior knowledge. This has been found to be the case in brain imaging studies (e.g., LeDoux, 1992 ), laboratory-based studies (e.g., Isen et al., 1987 ), and applied educational studies (e.g., Pekrun, 2005 ). A clear example of how emotion can impact on the learning process is where it creates an obstacle to learning, reflected in, for example, the vast body of work that has examined the detrimental effect of anxiety on the learning of mathematics ( Hembree, 1990 ). Similarly, confusion has been associated with blockages or impasses in the learning process ( Kennedy and Lodge, 2016 ).

Despite its importance, understanding, identifying and responding to difficulties and the resulting emotions in learning can be problematic, particularly in larger classes and in digital environments. Without the affordances of synchronous face-to-face human interaction in digital environments, emotions like confusion are difficult to detect. It is therefore challenging to respond to students with support or feedback to help their progress when they are stuck and become confused. Humans are uniquely tuned to respond to the emotional reactions of other humans ( Damasio, 1994 ). Intuitively we know what it is like to feel confused as a result of a difficulty in the learning process, yet confusion is not regarded as one of the “basic” emotions: like, for example, happiness, sadness, and anger ( Ekman, 2008 ). And while student confusion is relatively easy for an experienced teacher to detect in face-to-face settings ( Lepper and Woolverton, 2002 ), it is a complex emotion that is difficult to explain scientifically ( Silvia, 2010 ; Pekrun and Stephens, 2011 ). But we know that confusion is both commonly felt by students, is able to be diagnosed by teachers, and able to be resolved productively with teacher support (see for example, Lehman et al., 2008 ). Thus, at the most fundamental level, confusion is both widely experienced and relatively easily detected by teachers, despite the uncertainty about the exact relationship between difficulties and emotional responses in learning. Thus, student emotions, such as confusion, are relatively straightforward for experienced teachers to detect, understand and respond to in face-to-face settings with relatively small class sizes (see Woolfolk and Brooks, 1983 ; Woolf et al., 2009 ; Mainhard et al., 2018 ). The same is not true in digital environments or large classes. Emotions are less obvious to teachers when there are many students or when they interact with students via electronic methods ( Wosnitza and Volet, 2005 ). This means that alternate practices are needed to respond to students when they experience difficulties in these emerging environments.

The increased difficulty in detecting and responding to student emotions is one of several key reasons why a deeper understanding of difficulties and associated emotional responses is needed as new technologies and increasing class sizes impact education. Digital learning environments, especially online or distance learning environments, are often explicitly designed so that students will have flexibility and autonomy in their studies. Students, when studying online or at a distance, are often able to access course material and resources in their own time (and place) and are often not constrained by centralized timetables. As a result, there is often a greater onus on students in these environments to be more autonomous and self-directed in their learning ( Huang, 2002 ). Thus, increased learning flexibility often leads to students having fewer opportunities for engaging with teaching staff and receiving feedback in real time ( Mansour and Mupinga, 2007 ). While activities can be made available in the form of webinars and other synchronous formats, there remains a substantial responsibility on students to be autonomous and make good decisions about their own progress without requiring the real-time intervention of teaching staff.

Digital learning environments that largely provide self-directed students with autonomy and flexibility can potentially be created to detect and respond to student difficulties, but this potential has not yet been realized ( Arguel et al., 2017 ). A key challenge for educational technology researchers and educators is to create digital environments that are better able to provide support for and potentially respond to difficulties and the resulting emotions such as confusion, without the requirement of having a teacher on-call to support students. For this to occur, sophisticated digital learning environments need to be created that can support students in their autonomous, personalized and self-directed learning and provide feedback that in some way, emulates what a teacher does in more traditional, face-to-face settings.

In order for a digital learning environment to be responsive to difficulties—or indeed to other emotions that impact on learning—it is necessary for the system to detect the emotions that students experience during their learning ( Arguel et al., 2017 ). These emotional responses are the key indicator teachers use in face-to-face settings to determine when students are having problems. Given the difficulty of identifying emotions in digital learning environments in ways that humans can in face-to-face environments, this is a particularly vexing issue and one that has led to the growth of the burgeoning field of affective computing ( Picard, 2000 ). A second requirement is that digital learning environments need to be reactive to emotional responses such as confusion once these responses have been detected. For example, it would be useful if confused learners were given system-generated, programmed support to help them resolve their difficulties within the environment itself. Without a teacher present and without any automated support, it is possible that a student may succumb to their confusion, get frustrated and, as a result, disengage entirely ( D'Mello and Graesser, 2014 ). While it is difficult enough to determine when students become confused in these environments, it is even more complex to know when and how to intervene to prevent the confusion from becoming boredom or frustration. Finally, it would be a distinct advantage if any response or feedback that a digital learning environment provided a confused student could be tailored and personalized to the individual student and their learning pathway, progress and process ( Lodge, 2018 ). Teachers are able to quickly adapt to an individual student's emotional responses in a classroom in smaller classes. This enables teachers to intervene with individualized, customized assistance and feedback for students, which can help them manage both their emotions and their approach to the particular learning activity they are finding confusing. Effective intervention represents a significant challenge for designers of digital learning environments as teachers are adept at responding to student emotions in nuanced and personalized ways that are not easily programmed into a digital system.

Taken together, it is apparent that the increased use of digital learning environments has created a need for better understanding and intervening when students experience difficulties and become confused. This situation is, however, not helped by ongoing conjecture in the literature as to whether difficulties in the learning process resulting in confusion are detrimental or beneficial for learning ( Arguel et al., 2017 ). For example, Dweck (1986) argues that confusion is consistently detrimental to learning and is mediated by prior achievement, IQ scores, and confidence. She suggests that students who have poor prior achievement and confidence are at risk of attributing the experience of reaching a learning impasse and their resulting emotional response to their lack of aptitude. That is, students who become confused while completing a learning activity may interpret their confusion as a sign that they are incapable of learning the material. This argument aligns with a body of literature showing that persistent confusion can lead to frustration and boredom, which as a result has a negative impact on learning ( D'Mello and Graesser, 2014 ). More recently, however, research has suggested that difficulties resulting in confusion can benefit student learning. This is perhaps best exemplified in the research on what have been labeled “desirable difficulties” ( Bjork and Bjork, 2011 ), specific features of the learning situation that introduce beneficial difficulties that reliably enhance learning. Along similar lines, D'Mello et al. (2014) found that inducing difficulties and confusion in an intelligent tutoring system appeared to enhance learning. Moreover, some research has indicated that difficulties may be particularly beneficial for conceptual learning, where students sometimes need to overcome misconceptions before developing a more sophisticated understanding of the topic area ( Kennedy and Lodge, 2016 ). For example, Chen et al. (2013) developed a predict-observe-explain activity about commonly misconceived notions in electronics. Conflicting information was presented to students in the form of scenarios and the resulting confusion, when resolved, appeared to enhance student learning, particularly in relation to correcting the misconceptions. What is apparent from this research is that there seems to be a complex mix of factors that lead to students experiencing difficulties and uncertainty about what kinds of outcomes occur as a result. The factors vary between students and the kinds of difficulties faced will differ across knowledge domains and task types.

From these few studies it is evident that experiencing difficulties and confusion might be beneficial for different students under different circumstances and that the role of confusion in productive learning is important to understand across different learning environments, knowledge domains, and types of learning activities. Dweck's (1986) work indicates that confusion may be interpreted, managed and adapted to in different ways by students depending on their levels of confidence and past achievements. On the other hand, the work of D'Mello et al. (2014) and Chen et al. (2013) suggests that confusion can help students' learning, particularly when conceptual learning or conceptual change is the aim of the activity.

In this integrative review, we examine the literature on difficulties in learning. We focus here on the ways in which it might be possible to detect confusion experienced as a result of difficulties and intervene when students are counterproductively confused. Our aim is to explore the ways in which the difficulties students experience in learning could be harnessed for the purpose of enhancing their education. If digital learning environments are to reach their potential, they must be designed in a way to enable sophisticated support and feedback to confused students, in ways that are similar to those a teacher can provide in small group face-to-face settings.

Difficulties, Confusion, and Their Role in Learning

While confusion is common in educational practice and learning research, generally speaking, it has been poorly defined and understood in the educational literature ( Silvia, 2010 ). Confusion is often associated with reaching a cognitive impasse or “being stuck” while trying to learn something new ( Woolf et al., 2009 ), and it is also commonly regarded as a negative emotional experience or something to be avoided while learning (“Miss, help me, I am confused!”; see also Kort et al., 2001 ). Both of these aspects of confusion—being stuck and a feeling to be avoided—have perhaps led to the everyday notion that confusion is detrimental to learning. While there is certainly research that suggests when confusion persists to the point of frustration, it commonly leads to negative outcomes and has a detrimental impact on understanding ( Dweck, 1986 ; D'Mello and Graesser, 2011 ), as mentioned above, there are times when it may be beneficial to experience a cognitive impasse and the feeling of confusion when learning.

When it comes to defining what confusion actually is , there has been some ambiguity as to the extent to which it is a cognitive or emotional phenomenon ( D'Mello and Graesser, 2014 ). This uncertainty stems from debates about whether or not emotions such as confusion require some element of interpretation in order for the subjective experience of the emotion to take form. These views are derived from an attributional perspective on emotion ( Schachter and Singer, 1962 ). The process, according to this perspective, is that confusion is the result of an individual's attribution of an affective response to a preceding subjective experience. In other words, the student reaches an impasse that causes them some difficulty. As a result of the impasse, the student has some sort of emotional response to the situation they find themselves in. That emotional response is then interpreted by the individual—they attribute meaning to it—which may be confusion (or anxiety, or excitement). In this way, the individual experiences or “attributes” the emotion of confusion to the impasse. This interpretation is particularly important given that confusion in learning needs to be about some educational material attempting to be understood by a student ( Silvia, 2010 ). However, the attributional process also suggests that there are substantial differences between individuals in terms of the attributions they make. Two students can experience the exact same educational conditions and interpret them in vastly different ways, leading one to be confused while the other experiences no such response. The interaction between subjective experience and content knowledge has led to confusion being defined as an “epistemic emotion” ( Pekrun and Stephens, 2011 ). In other words, confusion can be defined as an affective response that occurs in relation to how people come to know or understand something. When defined as an epistemic emotion, confusion is considered to have both cognitive and affective components.

While it is reasonably clear that confusion has both cognitive and affective components, what is less obvious is whether difficulties in learning that result in confusion are productive or unproductive in learning. The literature in this area is somewhat equivocal. D'Mello et al. (2014) examined students when learning about scientific reasoning using an intelligent tutoring system. By inducing confusion through the presentation of contradictory information, they were able to determine whether the experience of being confused contributed negatively or positively to learning outcomes. Two virtual agents were used in the intelligent tutoring system to present information about the topic. In the confusion condition, the information from the two agents was contradictory and thus confusing for students. D'Mello and colleagues found that when students completed the “confused” (i.e., contradictory) condition compared to when they completed the control (i.e., non-contradictory) condition they showed enhanced performance, and as a result, argued that confusion can be beneficial for learning. What remains unclear though is whether it was the difficulty, the subjective experience of confusion or a mixture of both that was responsible for the observed differences between the groups.

Numerous attempts have been made to induce difficulties and confusion during learning to determine under what conditions it contributes productively to student learning outcomes (e.g., Lee et al., 2011 ; Lehman et al., 2013 ; Andres et al., 2014 ; Lodge and Kennedy, 2015 ). For example, Grawemeyer et al. (2015) examined students' confusion (and other emotions) during an activity in a digital learning environment that focussed on fractions. They found that, when provided with the appropriate support at the right time, in the form of feedback and instruction, the difficulties experienced by students led to enhanced learning. Similarly, Muller et al. (2007) considered how videos including the presentation and subsequent correction (refutation) of a misconceived notion could create student confusion compared to videos which used more traditional didactic presentation methods. Students who watched physics videos using the refutation method were exposed to the most confusing aspects of the concepts at the beginning of the video followed by an explanation of the commonly misconceived aspects of the content. Despite their higher levels of reported confusion, students in the refutation condition showed greater knowledge gains compared to students who watched the more traditional videos. Muller and his colleagues argued that these findings are related to the extra mental effort expended in trying to understand the material when it is confusing.

These findings, and particularly Muller et al.'s (2007) interpretation of their results, suggests that, when students experience difficulties and confusion, it may in fact serve as a trigger to help them overcome any conceptual obstacles they encounter during their learning. Along similar lines, Ohlsson (2011) argues that impasses and difficulties experienced in the learning process could be effective triggers for students to rethink their learning approaches. When students reach a conceptual impasse, this may serve as a cue that their current strategy or approach to the learning material is not effective, leading them to consider alternate strategies ( D'Mello and Graesser, 2012 ). This perspective is consistent with research that has considered students' strategies for dealing with challenging material. In a series of experimental studies, Alter et al. (2007) found that, when difficulties are introduced while people learn and reason about new information, it triggers a shift in strategy, activating a more systematic or analytic approach to the material. It may be, therefore, that difficulties encountered during the learning process that are accompanied by a subjective feeling of confusion can lead students to alter their learning strategies which may resolve the impasse, resulting in learning benefits. What this research and the findings suggest, however, is that students need to be able to identify the trigger as a cue to change strategy, which necessitates a capacity for monitoring and self-regulation.

Findings from other studies have found that confusion-inducing difficulties are not a productive part of the learning process despite the empirical research supporting the notion that confusion is beneficial in students' learning. For example, Andres et al. (2014) examined confusion while students engaged with a problem solving-based video game designed to help them learn about physics. In this study, confusion negatively impacted on students' ability to solve the problems and, compared to students who were less confused, confused students were less likely to master the learning material. A second study, Poehnl and Bogner (2013) , presented alternative scientific conceptions to a large group of ninth grade students. Despite the apparently higher levels of confusion in this group compared to a group who were not exposed to the confusion-inducing alternate conceptions, this group performed worse in terms of the overall number of conceptions learned. As such, there is conflicting evidence about what role difficulties and resulting confusion play in learning under different conditions. Given the possibility that confusion may operate as a trigger for action. This again highlights the possible role of self-regulation in this process. Year nine students in the Poehnl and Bogner study may not have the same capacity to self-regulate their learning as university students in the other studies discussed here.

Perhaps surprisingly, these are among the few empirical investigations to directly consider the impact of confusion on students' learning that have found it has a deleterious effect and those that have often involve younger students. However, research from other areas of learning and instruction, while not directly considering the role of confusion in learning, have provided findings that are relevant to the role that difficulties and confusion may play in students' learning. The important distinction seems to be the divergence between difficulties that students experience and the emotions that they experience as a result of these difficulties. While there has been limited research examining students' experiences of confusion, there has been much work done on trying to understand the role of difficulties in the learning process. For this review, we scanned the literature in educational psychology, experimental psychology, and education to look for concepts that share a family resemblance (as per Wittgenstein, 1968 ) to the research on difficulties and confusion.

Research on Learning Challenges and Difficulties

Prominent among similar bodies of work that may assist in understanding how difficulties might contribute to learning in digital environments is research in areas such as desirable difficulties (e.g., Bjork and Bjork, 2011 ), productive failure (e.g., Kapur, 2008 ), impasse-driven learning (e.g., VanLehn, 1988 ), cognitive disequilibrium (e.g., Graesser et al., 2005 ), and investigations of learning in discovery-based environments (e.g., Moreno, 2004 ; Alfieri et al., 2011 ). It is among these cognate fields of research that we may find further evidence to support the processes that lead to confusion being beneficial (or not) for learning. Our aim in attempting to compare and contrast this literature is to better understand how difficulties and confusion may be beneficial to learning and under what conditions.

Studies of desirable difficulties typically consider how aspects of the learning process can encumber learners, and how this process (or “difficulty”) can lead to enhanced learning compared to learners not exposed to the difficulty ( Bjork and Bjork, 2011 ). For example, Sungkhasettee et al. (2011) asked participants to study lists of words either upright or inverted. When learning the inverted words, participants demonstrated superior recall to conditions where the words were presented upright. In a similar study using more educationally relevant material, Adams et al. (2013) reported on a series of studies where erroneous examples were given to students who were learning mathematics in a digital environment. Across these studies, Adams et al. found that the use of erroneous examples in mathematics instruction led to improvements in learning consistent with those observed in the broader literature on desirable difficulties. In order to describe the mechanism by which difficulties enhance learning, Adams et al., argue that the use of incorrect examples encourages students to process the learning material in a different way, which leads to better retention and transfer of their understanding. They suggest that students, by considering and engaging in alternative problem solutions, process material more deeply and this is thought to be responsible for the enhanced learning observed (see also McDaniel and Butler, 2011 ).

The growing body of research on desirable difficulties has raised some questions about what constitutes a beneficial difficulty in the learning process ( Yue et al., 2013 ). For example, in a widely cited study, Diemand-Yauman et al. (2011) presented material to participants (study 1) and students (study 2) in easy and hard to read fonts. They found that participants and students who studied material in hard to read fonts performed better when later quizzed on the material. The authors hypothesized that the difficulty in reading the disfluent font slowed the learning process down, leading to deeper encoding, thus creating a desirable difficulty. Subsequent attempts to replicate this disfluency-based desirable difficulty have failed (e.g., Rummer et al., 2016 ), creating further uncertainty about what constitutes a desirable difficulty. Whatever the boundary conditions of desirable difficulties, it is apparent that certain kinds of difficulties in the learning process can reliably enhance the encoding, storage and retrieval of information. Participants exposed to desirable difficulties in the majority of the research on these effects to date have done so predominantly under laboratory conditions. However, it is apparent that there were substantial advantages to introducing targeted difficulties in the learning process that are strong candidates for enhancing learning in live educational settings ( Yan et al., 2017 ) and for further explaining how difficulties contribute to quality learning more broadly.

The principle of productive failure provides another possibility for framing the use of difficulties to enhance learning. Productive failure is a way of sequencing learning activities to give students an opportunity to familiarize themselves with a complex problem or issue in a structured environment but without significant instruction on the content of the material to be learned ( Kapur, 2015 ). Kapur (2014) tested groups of students who were given an opportunity to solve mathematics problems either before or after being given explicit instruction on the procedure associated with how to solve the problems. He found that the group of students who were given the opportunity to attempt problems before being given explicit instructions, despite often failing in their first attempts, overall demonstrated significantly greater gains in learning compared to students who received instructions prior to attempting to solve problems. Without necessarily having the requisite skills or information to solve the problems they were presented with, students would often reach an impasse in the learning process. Kapur (2015) argued that the impasse reached through the failed attempts at learning helps students generate more and different problem-solving strategies through a process that enhances learning over both the shorter and the longer term. It should be noted here that the tasks used in productive failure studies are different to those used in studies of desirable difficulties. Studies on productive failure tend to use more realistic problems given to students rather than tasks that rely more on memorisation.

Despite the different kinds of tasks used, there are clear parallels between the “failure” aspect of productive failure, and the “difficulties” encountered by students within a desirable difficulty paradigm ( Kapur and Bielaczyc, 2012 ). In both situations, there is a deliberate strategy to encumber students' learning process and potentially trigger confusion. Unlike the work on desirable difficulties, however, much of the research on productive failure has been carried out in naturalistic educational settings. This is achieved partly through the sequencing of the activity. The lack of direct instruction on the problem or issue often leads students to inevitably reach an impasse in the learning process that is seemingly accompanied by a sense of confusion ( Hung et al., 2009 ). As summarized by Kapur (2015) , the benefits of productive failure have been demonstrated many times in the peer-reviewed literature (e.g., Kapur, 2008 ; Kapur and Rummel, 2012 ). The results of these studies demonstrate that when students engage in some problem solving first followed by just-in-time instruction when they reach an impasse (i.e., the process leads to failure), it leads to enhanced learning in educational situations that are designed to rely on direct instruction.

Productive failure shares some similarity with the notion of impasse-driven learning, which focuses on what happens when students reach a blockage in their learning. VanLehn (1988) suggests that when students reach an impasse in the learning process, it forces them to go into a problem-solving strategy he labeled “repair.” In other words, students engage in a metacognitive process whereby they attempt to use problem-solving strategies to overcome the impasse or seek help. In both cases, the necessity of engaging in “meta-level” thinking is hypothesized to lead to more effective learning. This notion is similar to the argument made by Ohlsson (2011) in relation to strategy shifting and again highlights the importance of a capacity to monitor and self-regulate learning. In a test of impasse-driven learning, Blumberg et al. (2008) examined frequent and infrequent players of video games and asked them to describe their experiences as they worked through a novel video game. They found that participants who engaged in video games regularly were more able to describe their problem-solving strategies and moments of insight than those infrequently exposed to the types of impasses found in the games. To examine how this process applies to tutoring, VanLehn et al. (2003) analyzed dialogue in tutoring sessions on physics. Their results suggested that students were receptive to tutoring particularly when they reached an impasse in the learning process compared to when they were not at an impasse. The research on impasse-driven learning again suggests that there is something critical about the metacognitive, learning or study strategies that students engage in when their learning process is disrupted or challenged in some way.

At the core of desirable difficulties, productive failure and impasse driven learning is the notion that a difficulty or deliberately designed challenges are important for learning ( VanLehn, 1988 ; Ohlsson, 2011 ). Contemporary, and increasingly popular models of instruction, rooted in Bruner's (1961) notion of discovery-based learning also share this feature. Discovery-based models of teaching and learning such as problem-based learning typically present students with an ill-structured scenario, situation or problem, which they discuss, often in groups, and investigate in order to resolve. Students, in discussing the problem among themselves with or without a more expert facilitator, inevitably encounter material that they do not understand, that is confusing, and represents an impasse in their investigation of the problem. These impasses are central to the problem-based learning instructional model as they both drive the learning process (becoming the “learning issues” that guide students' learning and guide their investigations of the problem) and they also are said to act as intrinsic motivators for students as they attempt to resolve the problem ( Schmidt, 1993 ).

Given some of the core similarities between these theoretical models,—productive failure, impasse driven learning, desirable difficulties, and problem-based learning—a key question for educational researchers is: what are the underlying cognitive and learning processes that both bring about student confusion, and underpin the potential learning benefits derived from it? Also, how do these processes differ between individual students, learning different material, and engaged in different types of tasks? Graesser and D'Mello (2012) suggest that the prime candidate for this underpinning process is cognitive disequilibrium. The notion of cognitive disequilibrium is derived from Piaget's work on cognitive development ( Piaget, 1964 ). It occurs when there is an imbalance created when new information does not seamlessly integrate with existing mental schema. It is plausible then that confusion is the result of certain types of difficulties in the learning process, namely those that lead to an impasse underpinned by cognitive disequilibrium. In attempting to design for and provide interventions for productive challenges then, what appears to be important is not the introduction of difficulties per se but the introduction of difficulties that lead to an impasse and a sense of disequilibrium. Based on the research across these domains this, in turn, is hypothesized to lead to a change in learning approach or problem-solving strategy that can enhance learning.

A Framework for Understanding and Seeing Difficulties and Resulting Confusion in Learning

From this review, it seems clear that difficulties experienced during learning and resulting in confusion can be either productive or unproductive depending on the arrangement of and relationship between a range of variables within a learning environment. These include the type of learning activity, the knowledge domain being learned, and individual differences such as how students attribute difficulties and their capacity for self-regulated learning. For any particular learning or content area, the degree to which difficulties are experienced by a learner, and whether the experience of the resulting epistemic emotion will be productive or unproductive, is a result of a complex relationship between:

(i) Individually-based variables, such as prior knowledge, self-efficacy, and self-regulation;

(ii) The sequence, structure and design of learning tasks and activities; and

(iii) The design and timeliness feedback, guidance, and support provided to students during the learning activity or task.

A key challenge for educational researchers is to determine what sets of relationships between what variables lead to adaptive and maladaptive learning processes and outcomes in digital learning environments.

The review of the literature also suggests two learning processes could be promoted when students experience confusion: one general and one specific. The first, more general, process is that difficulties encourage students to invest more “mental effort” in their learning; they somehow work harder cognitively—through attention or concentration—to resolve the conceptual impasse and the confusion that has resulted from it. The second is that students, when piqued by a conceptual impasse and the resulting feelings of confusion, actively generate and adopt alternative approaches to the learning material they are seeking to understand. This second process suggests that students do not simply invest a greater effort in their learning; it suggests that they investigate and adopt alternative study approaches and strategies, which they then apply. In order for this second process to occur, students need to be sufficiently able to monitor their progress and understand how to take action on the basis of their experience of difficulty or the reaching of an impasse.

Finally, this review suggests that insurmountable learning difficulties may arise when students experience too much confusion or when confusion persists for too long. As discussed by D'Mello and Graesser (2014) one of the most important factors in the beneficial effect of confusion is that it is resolved. Unresolved, persistent confusion leads to frustration, boredom and therefore is detrimental for learning. In an example of this delicate balance in action, Lee et al. (2011) examined confusion while novices attempted to learn how to write computer code. They found that overcoming confusion can enhance learning but, when it remains unresolved, it leads to deleterious effects on student achievement. This observation speaks to the importance of addressing student confusion in a timely and personalized way. However, given the complexities introduced by the individual differences between students, this is not a straightforward task.

In many ways, these features of confusion are captured in Graesser's (2011) notion of a “zone of optimal confusion” (ZOC). Reminiscent of Vygotsky's (1978) concept of the zone of proximal development, the ZOC suggests that it is important not to have too little or too much difficulty but to aim to have just the right amount. If educators and educational designers aimed to create challenges and induce a change in learning strategy as a deliberate tactic to promote conceptual change, students would need to experience sufficient subjective difficulty for the impasse in the learning process to be experienced as confusion. However, if too much or persistent confusion is experienced, it will lead to frustration, hopelessness, boredom and giving up. To use difficulties as a deliberate instructional strategy in digital learning environments is, therefore, a double-edged sword. If students are not sufficiently engaged to become confused and redress their way of approaching the activity, they can then become bored and potentially regress back to their initial conception. If students can be guided and supported through their confusion, however, it can then lead to the productive learning outcomes reported in the empirical literature. That, in essence, is the ZOC.

One ongoing issue with the notion of “optimal confusion” is that it is difficult to determine what separates productive from non-productive confusion as learning unfolds. Given the complexities involved due to individual responses to difficulties in learning, the threshold at which constructive confusion becomes non-productive frustration or boredom will differ markedly between individuals ( Kennedy and Lodge, 2016 ). Identifying where a student might be along the confusion continuum in advance of knowing the outcome of the learning activity is a significant challenge. Kennedy and Lodge found that there were markers evident in trace data suggestive of students crossing the threshold into unproductive forms of confusion. For example, extended delays in progress observed as significant time lags between interactions or rapid cycling through activities are possible indicators of boredom or frustration respectively. Inferring in real time whether students are experiencing confusion that is productive or unproductive remains a challenge but there is some emerging evidence that data and analytics could be used to help predict how students are tracking and provide feedback and support independent of knowing the outcome ( Arguel et al., 2019 ).

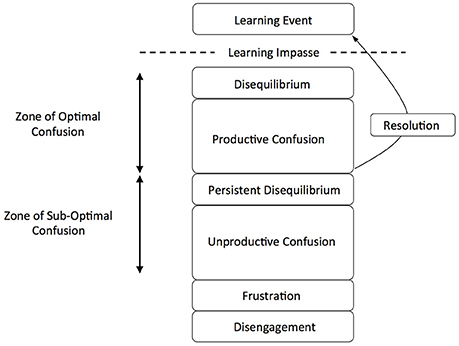

Based on Graesser's (2011) “ZOC” and, using cognitive disequilibrium as a framing mechanism for the important role of confusion in learning, we propose a framework for confusion in digital learning environments (see Figure 1 ). From the top of Figure 1 , a learning event can be specifically designed to create cognitive disequilibrium. An example of this is the approach used by Muller et al. (2008) to create disequilibrium in videos. In this study, the researchers created disequilibrium by focussing on misconceptions as a core instructional strategy, the disequilibrium being generated through the distance between what people think they know and the accepted scientific understanding. From there, disequilibrium is generated as a cause of an impasse in the learning process. At this stage, students will move into the ZOC so long as they are sufficiently engaged and attribute the impasse to be confusing. If this occurs in a productive way and the student has sufficient metacognitive awareness and skill to recognize the confusion as a cue to change strategy, the disequilibrium will be effectively resolved, conceptual change will occur, and students will move on to another learning event. If the confusion becomes persistent, on the other hand, then students may possibly move into the zone of sub-optimal confusion (ZOSOC). When this occurs, the confusion becomes unproductive and leads to possible frustration and/or boredom. Again, it is difficult to determine in real time when and how this occurs and that remains a challenge for future research to examine. The model proposed here builds on similar previous work by D'Mello and Graesser (2014) but is particularly focused on further elucidating both the underpinning processes and the characteristics of the learning design that might influence both the initiation of confusion and its resolution.

Figure 1 . Conceptual framework for the zones of optimal and sub-optimal confusion.

Implications of the Framework

If it can be assumed that confusion is beneficial for learning under some circumstances then it is worth considering the implications of this for learning design. The creation of disequilibrium and confusion is important to both engage students and create the uncertainty required to help them develop conceptual knowledge. A learning event that is aimed at creating this disequilibrium will need to be designed with the aim of both getting students into the ZOC and making sure that they do not enter the ZOSOC. Enticing students to enter the ZOC has been achieved in numerous ways as described above. For example, the material presented or the medium through which it is presented can be contradictory, counterintuitive or the environment can have little to no guidance as in pure discovery-based learning and, to a lesser extent, productive failure. Taken together, there would appear to be many ways to lure students into the ZOC. That said, there are no guarantees that students will enter this ZOC. If a student has high levels of prior knowledge or is highly confident, for example, they may persist at a task with renewed vigor rather than attribute an impasse as confusing ( Arguel et al., 2016 ).

When it does occur, ensuring the confusion leads to a productive outcome is more challenging as it requires the students themselves resolving the disequilibrium, a timely intervention from a teacher, or in a way that can be automatically supported in a digital learning environment. Thus, there appear to be two broad options for ensuring confusion leads to productive outcomes. As alluded to above, the development of effective self-regulation in learning is one way of ensuring that students move from being confused to effectively learning. While students' skills in self-regulation are something they may at least partly bring to a learning event, there is also potential for building in interventions to assist with self-regulation into the learning environment ( Lodge et al., 2018 ). For example, if students did change their strategy or approach to a learning event, this creates an opportunity for them to reflect on the change in their approach and consider how such a strategy might be useful in future learning situations. So, while there are opportunities for helping students to effectively learn new material, there are also possibilities in these situations for students to consider the strategies they use when learning more broadly. In a very concrete manner, one intervention strategy is to help students to understand that difficulties and confusion as part of the learning process are perfectly normal and, indeed, necessary in many instances. Helping students to see confusion as a cue to try a different approach rather than see it is a sign that they are incapable would be a simple way to improve students' capacity to deal with difficult and confusing elements of learning.

A second option for ensuring that students effectively pass through the ZOC and achieve productive learning outcomes is to use feedback. Feedback can take many different forms in digital learning environments thus providing many options for intervening when students appear to be confused. The critical aspect of any intervention on confusion to avoid having students enter into the ZOSOC will be to personalize that feedback by taking into account their prior knowledge ( Lehman et al., 2012 ). Intelligent tutoring systems have some capacity for this level of personalisation. However, much remains to be done before these systems can be regarded as being truly adaptive to the affective components of student learning and applied at scale ( Baker, 2016 ). As a proof of concept though, there are examples of sophisticated adaptive systems that have been built to provide real time feedback and prompts based on student performance as they progress through procedural tasks. For example, adaptive systems have long been available to provide data-driven feedback and prompts to trainee surgeons ( Piromchai et al., 2017 ), and dentists ( Perry et al., 2015 ). That it is possible to create systems that can use data about student interaction to inform feedback interventions suggest that it is possible to build systems that will work across different knowledge domains to respond to students having difficulties.

In the interim, while intelligent tutoring and other adaptive systems built on machine learning and artificial intelligence mature, there are possibilities for building digital learning environments to cater for difficulties and resulting confusion. Most prominent among these are the development of sophisticated learning designs that can respond to student confusion through enhancing student self-regulation and providing feedback in the form of hints or formative information about the strategies or approaches being used. That is not to say that the development of such systems will be easy. Part of the approach to helping students become better equipped to deal with difficulties and confusion needs to be to address the notion that difficulties are inherently detrimental and an indicator that students are not capable.

Difficulties and the confusion that often results are difficult to detect, manage, and respond to in digital learning environments and large classes compared to smaller group face-to-face settings. Despite this, in this paper we have argued that difficulties and confusion are important in the process of learning, particularly when students are developing more sophisticated understandings of complex concepts. Work on desirable difficulties, impasse driven learning, productive failure, and pure discovery-based learning all provide clues as to how confusion could be beneficial for learning. The creation of a sense of cognitive disequilibrium appears to be a vital element and the confusion needs to be effectively resolved by helping students pass through the ZOC without them entering the ZOSOC. We have attempted here to provide a conceptual model for the process by which students pass through this optimal zone. Our hope is that this will help to outline the process of the development and resolution of confusion so that researchers and learning designers can continue to develop methods for ensuring students achieve productive outcomes as a result of becoming confused.

Author Contributions

JL, GK, LL, AA, and MP contributed to the conceptualization, research, and writing of this article.

The authors of this review received funding from the Australian Research Council for the work in this review as part of a Special Research Initiative (Grant number: SRI20300015).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Paula de Barba toward this project.

Adams, D. M., McLaren, B. M., Mayer, R. E., Goduadze, G., and Isotani, S. (2013). Erroneous examples as desirable difficulty. Artif. Int. Educ. Conf. Proc. 2013, 803–806. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-39112-5_117

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alfieri, L., Brooks, P. J., Aldrich, N. J., and Tenenbaum, H. R. (2011). Does discovery-based instruction enhance learning? J. Educ. Psychol. 103, 1–18. doi: 10.1037/a0021017

Alter, A. L., Oppenheimer, D. M., Epley, N., and Eyre, R. N. (2007). Overcoming intuition: metacognitive difficulty activates analytic reasoning. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 136, 569–576. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.4.569

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Andres, J., Rodrigo, M., and Sugay, J. O. (2014). “An exploratory analysis of confusion among students using Newton's playground,” in Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Computers in Education (Nara: Asia-Pacific Society for Computers in Education).

Google Scholar

Arguel, A., Lockyer, L., Lipp, O. V., Lodge, J. M., and Kennedy, G. (2017). Inside out: detecting learners' confusion to improve interactive digital learning environments. J. Educ. Comp. Res. 55, 526–551. doi: 10.1177/0735633116674732

Arguel, A., Lodge, J. M., Pachman, M., and de Barba, P. (2016). “Confidence drives exploration strategies in interactive simulations,” in Show Me the Learning. Proceedings ASCILITE 2016 , eds S. Barker, S. Dawson, A. Pardo, and C. Colvin (Adelaide, SA), 33–42.

Arguel, A., Pachman, M., and Lockyer, L. (2019). “Identifying epistemic emotions from activity analytics in interactive digital learning environments,” in Learning Analytics in the Classroom: Translating Learning Analytics Research for Teachers , eds J. M. Lodge, J. C. Horvath, and L. Corrin (Abingdon: Routledge), 71–77.

Baker, R. S. (2016). Stupid tutoring systems, intelligent humans. Int. J. Artif. Intel. Educ. doi: 10.1007/s40593-016-0105-0

Bjork, E. L., and Bjork, R. A. (2011). “Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning,” in Psychology and the Real World: Essays Illustrating Fundamental Contributions to Society , eds M. A. Gernsbacher, R. W. Pew, L. M. Hough, and J. R. Pomerantz (New York, NY: Worth), 56–64.

Blumberg, F. C., Rosenthal, S. F., and Randall, J. D. (2008). Impasse-driven learning in the context of video games. Comp. Hum. Behav. 24, 1530–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2007.05.010

Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harv. Educ. Rev. 31, 21–32.

Chen, Y. L., Pan, P. R., Sung, Y. T., and Chang, K. E. (2013). Correcting misconceptions on electronics: Effects of a simulation-based learning environment backed by a conceptual change model. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 16, 212–227.

D'Mello, S., and Graesser, A. (2011). The half-life of cognitive-affective states during complex learning. Cognit. Emot. 25, 1299–1308. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.613668

D'Mello, S., and Graesser, A. (2012). Dynamics of affective states during complex learning. Learn. Instru. 22, 145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.10.001

D'Mello, S., Lehman, B., Pekrun, R., and Graesser, A. (2014). Confusion can be beneficial for learning. Learn. Instru. 29, 153–170. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.05.003

Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes' Error . New York, NY: G.P Putnam's Sons.

Diemand-Yauman, C., Oppenheimer, D. M., and Vaughan, E. B. (2011). Fortune favors the bold (and the italicized): effects of disfluency on educational outcomes. Cognition 118, 114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2010.09.012

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text

D'Mello, S., and Graesser, A. (2014). “Confusion,” in Handbook of Emotions and Education eds R. Pekrun and L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (New York, NY: Routledge), 289–310.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. Am. Psychol. 41, 1040–1048. doi: 10.1037/0003-066XX.41.10.1040

Ekman, P. (2008). An argument for basic emotions. Cognit. Emot. 6, 169–200. doi: 10.1080/02699939208411068

CrossRef Full Text

Graesser, A. C. (2011). Learning, thinking, and emoting with discourse technologies. Am. Psychol. 66:746. doi: 10.1016/0749

Graesser, A. C., and D'Mello, S. (2012). Emotions during the learning of difficult material. Learn. Motivat. 57, 183–225. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394293-7.00005-4

Graesser, A. C., Lu, S., Olde, B. A., Cooper-Pye, E., and Whitten, S. (2005). Question asking and eye tracking during cognitive disequilibrium: Comprehending illustrated texts on devices when the devices break down. Mem. Cognit. 33, 1235–1247. doi: 10.3758/BF03193225

Grawemeyer, B., Mavrikis, M., Holmes, W., Hansen, A., Loibl, K., and Gutierrez-Santos, S. (2015). Affect matters: exploring the impact of feedback during mathematical tasks in an exploratory environment. Artif. Intell. Educ. Conf. Proc. 2015, 595–599. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-19773-9_70

Hembree, R. (1990). The nature, effects, and relief of mathematics anxiety. J. Res. Mathe. Educ. 21, 33–46. doi: 10.2307/749455

Huang, H. M. (2002). Toward constructivism for adult learners in online learning environments. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 33, 27–37. doi: 10.1111/1467-8535.00236

Hung, D., Chen, V., and Lim, S. H. (2009). Unpacking the hidden efficacies of learning in productive failure. Learn. Inqu. 3, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11519-008-0037-1

Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., and Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52, 1122–1131. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1122

Kapur, M. (2008). Productive failure. Cognit. Instruc. 26, 379–424. doi: 10.1080/07370000802212669

Kapur, M. (2014). Productive failure in learning math. Cognit. Sci. 38, 1008–1022. doi: 10.1111/cogs.12107

Kapur, M. (2015). Learning from productive failure. Learn. Res. Pract. 1, 51–65. doi: 10.1080/23735082.2015.1002195

Kapur, M., and Bielaczyc, K. (2012). Designing for productive failure. J. Learn. Sci. 21, 45–83. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2011.591717

Kapur, M., and Rummel, N. (2012). Productive failure in learning from generation and invention activities. Instruc. Sci. 40, 645–650. doi: 10.1007/s11251-012-9235-4

Kennedy, G., and Lodge, J. M. (2016). “All roads lead to Rome: Tracking students' affect as they overcome misconceptions,” in Show Me the Learning. Proceedings ASCILITE 2016 , eds S. Barker, S. Dawson, A. Pardo, and C. Colvin (Adelaide, SA), 318–328.

Kort, B., Reilly, R., and Picard, R. (2001). “An affective model of interplay between emotions and learning: reengineering educational pedagogy—building a learning companion,” in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technology: Issues, Achievements and Challenges , eds T. Okamoto, R. Hartley, kinshuk, and J. P. Klus (Madison, WI), 43–48.

LeDoux, J. E. (1992). Brain mechanisms of emotion and emotional learning. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2, 191–197. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90011-9

Lee, D., Rodrigo, M., Baker, R. D., Sugay, J. O., and Coronel, A. (2011). “Exploring the relationship between novice programmer confusion and achievement,” in International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (Berlin: Springer), 175–184.

Lehman, B., D'Mello, S., and Graesser, A. (2012). Confusion and complex learning during interactions with computer learning environments. Inter. Higher Educ. 15, 184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.01.002

Lehman, B., D'Mello, S., and Graesser, A. (2013). “Who benefits from confusion induction during learning? An individual differences cluster analysis,” in Proceedings of 16th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education , eds K. Yacef, C. Lane, J. Mostow, and P. Pavlik (Berlin: Springer), 51–60.

Lehman, B., Matthews, M., D'Mello, S., and Person, N. (2008). “What are you feeling? Investigating student affective states during expert human tutoring sessions,” in Intelligent Tutoring Systems, Vol. 5091 (Berlin: Springer), 50–59.

Lepper, M. R., and Woolverton, M. (2002). “The wisdom of practice: Lessons learned from the study of highly effective tutors,” in Improving Academic Achievement: Contributions of Social Psychology , ed J. Aronson (Orlando, FL: Academic Press), 135–158.

Lodge, J. M. (2018). “A futures perspective on information technology and assessment,” in International Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education 2nd Edn , eds J. Voogt, G. Knezek, R. Christensen, and K. W. Lai (Berlin: Springer), 1–13.

Lodge, J. M., and Kennedy, G. (2015). “Prior knowledge, confidence and understanding in interactive tutorials and simulations,” in Globally Connected, Digitally Enabled, Proceedings Ascilite 2015 in Perth , eds T. Reiners, B. R. von Konsky, D. Gibson, V. Chang, L. Irving, and K. Clarke (Tugan, QLD: ASCILITE), 178–188.

Lodge, J. M., Kennedy, G., and Hattie, J. A. C. (2018). “Understanding, assessing and enhancing student evaluative judgement in digital environments,' in Developing Evaluative Judgement in Higher Education: Assessment for Knowing and Producing Quality Work , eds D. Boud, R. Ajjawi, P. Dawson, and J. Tai (Abingdon: Routledge), 70–78.

Mainhard, T., Oudman, S., Hornstra, L., Bosker, R. J., and Goetz, T. (2018). Student emotions in class: the relative importance of teachers and their interpersonal relations with students. Learn. Instruc. 53, 109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.07.011

Mansour, B. E., and Mupinga, D. M. (2007). Students' positive and negative experiences in hybrid and online classes. Coll. Stud. J. 41, 242–248.

McDaniel, M. A., and Butler, A. C. (2011). “A contextual framework for understanding when difficulties are desirable,” in Successful Remembering and Successful Forgetting: A Festschrift in Honor of Robert A. Bjork , ed A. S. Benjamin (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 175–198.

Moreno, R. (2004). Decreasing cognitive load for novice students: effects of explanatory versus corrective feedback in discovery-based multimedia. Instruc. Sci. 32, 99–113. doi: 10.1023/B:TRUC.0000021811.66966.1d

Muller, D. A., Bewes, J., Sharma, M. D., and Reimann, P. (2007). Saying the wrong thing: improving learning with multimedia by including misconceptions. J. Comp. Assis. Learn. 24, 144–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2007.00248.x

Muller, D. A., Sharma, M. D., and Reimann, P. (2008). Raising cognitive load with linear multimedia to promote conceptual change. Sci. Educ. 92, 278–296. doi: 10.1002/sce.20244

Ohlsson, S. (2011). Deep Learning . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Pekrun, R. (2005). Progress and open problems in educational emotion research. Learn. Instruc. 15, 497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.014

Pekrun, R., and Stephens, E. J. (2011). “Academic emotions,” in APA Educational Psychology Handbook, Vol 2: Individual Differences and Cultural and Contextual Factors , eds K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, S. Graham, J. M. Royer, and M. Zeidner (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 3–31.

Perry, S., Bridges, S. M., and Burrow, M. F. (2015). A review of the use of simulation in dental education. Simul. Healthc. 10, 31–37. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000059

Piaget, J. (1964). Cognitive development in children: Piaget: development and learning. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2, 176–186. doi: 10.1002/tea.3660020306

Picard, R. W. (2000). Affective Computing . Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Piromchai, P., Ioannou, I., Wijewickrema, S., Kasemsiri, P., Lodge, J. M., Kennedy, G., et al. (2017). The effects of anatomical variation on trainee performance in a virtual reality temporal bone surgery simulator – a pilot study. J. Laryngol. Otol. 131, S29–S35. doi: 10.1017/S0022215116009233

Poehnl, S., and Bogner, F. X. (2013). Cognitive load and alternative conceptions in learning genetics: effects from provoking confusion. J. Educ. Res. 106, 183–196. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2012.687790

Rummer, R., Schweppe, J., and Schwede, A. (2016). Fortune is fickle: null-effects of disfluency on learning outcomes. Metacogn. Learn. 11, 57–70. doi: 10.1007/s11409-015-9151-5

Schachter, S., and Singer, J. (1962). Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychol. Rev. 69, 379–399. doi: 10.1037/h0046234

Schmidt, H. G. (1993). Foundations of problem-based learning: some explanatory notes. Med. Educ. 27, 422–432.

Silvia, P. J. (2010). Confusion and interest: The role of knowledge emotions in aesthetic experience. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 4, 75–80. doi: 10.1037/a0017081

Sungkhasettee, V. W., Friedman, M. C., and Castel, A. D. (2011). Memory and metamemory for inverted words: illusions of competency and desirable difficulties. Psychonom. Bull. Rev. 18, 973–978. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0114-9

VanLehn, K. (1988). “Toward a theory of impasse-driven learning,” in Learning Issues for Intelligent Tutoring Systems , eds H. Mandl and A. Lesgold (New York, NY: Springer), 19–41.

VanLehn, K., Siler, S., Murray, C., and Yamauchi, T. (2003). Why do only some events cause learning during human tutoring? Cognit. Instruc. 21, 209–249. doi: 10.1207/S1532690XCI2103_01

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Mental Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wittgenstein, L. (1968). Philosophical Investigations 3rd edn . transl. by G. E. M. Anscombe. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell.

Woolf, B., Burleson, W., Arroyo, I., Dragon, T., Cooper, D., and Picard, R. (2009). Affect-aware tutors: recognising and responding to student affect. Int. J. Learn. Technol. 4, 129–164. doi: 10.1504/IJLT.2009.028804

Woolfolk, A. E., and Brooks, D. M. (1983). Chapter 5: nonverbal communication in teaching. Rev. Res. Educ. 10 , 26, 103–149.

Wosnitza, M., and Volet, S. (2005). Origin, direction and impact of emotions in social online learning. Learn. Instruc. 15, 449–464. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.009

Yan, V. X., Clark, C. M., and Bjork, R. A. (2017). “Memory and metamemory considerations in the instruction of human beings revisited,” in From the Laboratory to the Classroom: Translating Science of Learning for Teachers , eds J. C. Horvath, J. M. Lodge, and J. Hattie (Abingdon: Routledge), 61–78.

Yue, C. L., Castel, A. D., and Bjork, R. A. (2013). When disfluency is-and is not-a desirable difficulty: the influence of typeface clarity on metacognitive judgments and memory. Mem. Cognit. 41, 229–241. doi: 10.3758/s13421-012-0255-8

Keywords: confusion, digital learning environments, desirable difficulties, productive failure, discovery-based learning, impasse driven learning, cognitive disequilibrium

Citation: Lodge JM, Kennedy G, Lockyer L, Arguel A and Pachman M (2018) Understanding Difficulties and Resulting Confusion in Learning: An Integrative Review. Front. Educ . 3:49. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00049

Received: 28 September 2017; Accepted: 12 June 2018; Published: 28 June 2018.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2018 Lodge, Kennedy, Lockyer, Arguel and Pachman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jason M. Lodge, [email protected]

- Resource Collection

- State Resources

Community, Courses, and Resources for Adult Education

- Topic Areas

- About the Collection

- Review Process

- Reviewer Biographies

- Federal Initiatives

- COVID-19 Support

- ADVANCE Integrated Education and Training (IET)

- IET Train-the Trainer Resources

- IET Resource Repository

- Program Design

- Collaboration and Industry Engagement

- Curriculum and Instruction

- Policy and Funding

- Program Management - Staffing -Organization Support

- Student Experience and Progress

- Adult Numeracy Instruction 2.0

- Advancing Innovation in Adult Education

- Bridge Practices

- Holistic Approach to Adult Ed

- Integrated Education and Training (IET) Practices

- Secondary Credentialing Practices

- Business-Adult Education Partnerships Toolkit

- Partnerships: Business Leaders

- Partnerships: Adult Education Providers

- Success Stories

- Digital Literacy Initiatives

- Digital Resilience in the American Workforce

- Landscape Scan

- Publications and Resources

- DRAW Professional Development Resources

- Employability Skills Framework

- Enhancing Access for Refugees and New Americans

- English Language Acquisition

- Internationally-Trained Professionals

- Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship and Civic Participation

- Workforce Preparation Activities

- Workforce Training

- Integrated Education and Training in Corrections

- LINCS ESL PRO

- Integrating Digital Literacy into English Language Instruction

- Meeting the Language Needs of Today's English Language Learner

- Open Educational Resources (OER) for English Language Instruction

- Preparing English Learners for Work and Career Pathways

- Recommendations for Applying These Resources Successfully

- Moving Pathways Forward

- Career Pathways Exchange

- Power in Numbers

- Adult Learner Stories

- Meet Our Experts

- Newsletters

- Reentry Education Tool Kit

- Education Services

- Strategic Partnerships

- Sustainability

- Transition Processes

- Program Infrastructure

- SIA Resources and Professional Development

- Fulfilling the Instructional Shifts

- Observing in Classrooms

- SIA ELA/Literacy Videos

- SIA Math Videos

- SIA ELA Videos

- Conducting Curriculum Reviews

- Boosting English Learner Instruction

- Student Achievement in Reading

- TEAL Just Write! Guide

- Introduction

- Fact Sheet: Research-Based Writing Instruction

- Increase the Amount of Student Writing

- Fact Sheet: Adult Learning Theories

- Fact Sheet: Student-Centered Learning

- Set and Monitor Goals

- Fact Sheet: Self-Regulated Learning

- Fact Sheet: Metacognitive Processes

- Combine Sentences

- Teach Self-Regulated Strategy Development

- Fact Sheet: Self-Regulated Strategy Development

- Teach Summarization

- Make Use of Frames

- Provide Constructive Feedback

- Apply Universal Design for Learning

- Fact Sheet: Universal Design for Learning

- Check for Understanding

- Fact Sheet: Formative Assessment

- Differentiated Instruction

- Fact Sheet: Differentiated Instruction

- Gradual Release of Responsibility

- Join a Professional Learning Community

- Look at Student Work Regularly

- Fact Sheet: Effective Lesson Planning

- Use Technology Effectively

- Fact Sheet: Technology-Supported Writing Instruction

- Project Resources

- Summer Institute

- Teacher Effectiveness in Adult Education

- Adult Education Teacher Induction Toolkit

- Adult Education Teacher Competencies

- Teacher Effectiveness Online Courses

- Teaching Skills that Matter

- Teaching Skills that Matter Toolkit Overview

- Teaching Skills that Matter Civics Education

- Teaching Skills that Matter Digital Literacy

- Teaching Skills that Matter Financial Literacy

- Teaching Skills that Matter Health Literacy

- Teaching Skills that Matter Workforce Preparation

- Teaching Skills that Matter Other Tools and Resources

- Technology-Based Coaching in Adult Education

- Technical Assistance and Professional Development

- About LINCS

- History of LINCS

- LINCS Guide

- Style Guide

Adults with Learning Disabilities: A Review of the Literature

In this literature review, the authors report on the research and current knowledge regarding adults with learning disabilities. The literature review covers a number of areas including defining learning disabilities and their affects, determining if adults have LD, reviewing effective teaching and support strategies, and giving some implications for research, policy, and practice.

Note: A more recent literature review called Learning to Achieve can be found at: http://lincs.ed.gov/programs/learningtoachieve/materials.html

This resource is an excellent one, especially for those wanting to understand the history of literacy and learning disabilities. It is a broad, comprehensive overview and compilation of research in the field of adults with learning disabilities and contains a density of data and facts as well as a solid foundation for advanced investigation and review. Even though the literature review is more than eight years old, the relationship between the information as presented from 1989 through 2000 provides a solid connection to the ongoing work of the past five to ten years. Anyone new to the field would benefit from reading this resource.

The literature review organizes the information into two broad categories: 1) What we Know about Adults with LD with seven major research studies and 2) How we Serve Adults with Learning Disabilities which is subdivided into sections on Reading Research , Assessment , Instructional Interventions , and Assistive Technology . The results of the literature search are then presented, along with implications for research, policy, and practice. The authors identify many questions around diversity, assessment, reading, instructional interventions, employment, self-determination, and professional development of adult basic education providers.

This site includes links to information created by other public and private organizations. These links are provided for the user’s convenience. The U.S. Department of Education does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness, or completeness of this non-ED information. The inclusion of these links is not intended to reflect their importance, nor is it intended to endorse views expressed, or products or services offered, on these non-ED sites.

Please note that privacy policies on non-ED sites may differ from ED’s privacy policy. When you visit lincs.ed.gov, no personal information is collected unless you choose to provide that information to us. We do not give, share, sell, or transfer any personal information to a third party. We recommend that you read the privacy policy of non-ED websites that you visit. We invite you to read our privacy policy.

Related Topics

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A qualitative study of the communication and information needs of people with learning disabilities and epilepsy with physicians, nurses and carers

Jerry paul k. ninnoni.

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Department of Mental Health, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana

Associated Data

Data collected from this study were archived in accordance with the Robert Gordon University policy and as required by the Grampian Research Ethics Committee. However, data can be made available by corresponding author on request.

Living with a chronic condition such as epilepsy can have a debilitating effect on the individual and their carers. Managing epilepsy among people with learning disabilities may present a challenge because of limited communication and may require a multidisciplinary approach. The study investigated the communication and information needs of people with learning disabilities with epilepsy and their physicians, nurses and carers.

Qualitative designed was adopted to collect data from 15 community-based people with mild learning disabilities with epilepsy and 13 carers. Recorded data were transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically.

A range of findings emerged related to patient communication and information needs. These included: Knowledge regarding epilepsy; involvement; honesty and openness when giving information and consistency in provision of information.

People with learning disabilities with epilepsy and their carers would like to know more about epilepsy, to be more involved decision makings through communication in the management of epilepsy to enable them feedback information regarding their health.

Effective communication is more than just providing information but transactional between the communication partners. It involves understanding the emotion and reasons behind the information. In addition to being able to convey a message, there is a need to listen in a way that gains the full meaning of what is being communicated and the other party feels being heard and their views considered. Thus, effective communication is central to the management of service users who have learning disabilities with epilepsy and their doctors, nurses and carers.

Seizure control maybe one of the main goals for medical and nursing staff as well as for people with learning disabilities and their carers [ 1 ]. The individual with epilepsy will need to have knowledge of the condition and be able to communicate information regarding seizures, medications and side effects [ 2 , 3 ]. It is claimed that people with learning disabilities are at greater risks of seizures compared with the epilepsy population overall [ 4 – 6 ] and mortality is increased among the learning disabilities population [ 7 ]. Also, people with epilepsy who live in institutional settings have better seizure control when compared with those in community settings [ 8 – 13 ] and this may reflect the availability of specialist services in residential settings. Following deinstitutionalisation, there are increased numbers of people with learning disabilities and epilepsy residing in communities either living independently or supported by carers who may have limited knowledge and information regarding epilepsy [ 14 , 15 ]. However, patients and carers’ knowledge and information regarding epilepsy may facilitate communication with health professionals such as doctors and nurses.

Non-adherence may imply a refusal to seek healthcare, non-participation in health management or failure to follow doctors’ instructions [ 16 , 17 ]. It may also take other forms for example, the information or education given by healthcare professionals is either misunderstood, administered wrongly or the information is ignored completely [ 18 , 19 ]. All these could be due to a range of factors including communication lapses and inadequate information provision [ 20 , 21 ]. The philosophy of concordance advocates a decision-making process where patients can feel more involved in communication and more comfortable with their treatment [ 22 ]. It is argued that adherence is a multivariate construct that is determined by the interplay of many factors [ 14 , 20 ]. Aspects may reflect the complexities of treatment regimes, level of support and the individuals living circumstances [ 14 , 23 ]. A study by Eastock and Baker [ 24 ] reported that failure to comply with treatment is common among people with epilepsy compared with other chronic conditions. And the reasons for non-adherence included; lack of understanding of why it was necessary to adhere to treatment and the level of information provision, doctor-patient relationship, psychosocial factors and patient characteristics [ 24 , 25 ]. It has also been found that patients reporting with side-effects are more likely to be non-adherent [ 20 , 25 ]. This may be due to poor communication and are reported higher among individuals with learning disabilities who are also more susceptibility to unidentified side effects [ 20 , 26 , 27 ].