Writing an Abstract for a Conference

January 2, 2022 8 min read

January 2, 2022 | 8 min read

Writing Abstracts for a Conference

An "abstract" for an academic conference is a short summary of the scientific research you are involved in. While abstracts generally have a standard format and include more or less the same information and in a similar layout, each conference may have its unique requirements. It is, therefore, essential that you make yourself aware of that conference's specific requirements when planning to submit an abstract for a conference.

Abstracts are submitted to the conference organizers by or on behalf of one of the research authors. This person is called the "presenting author". The presenting author submits the abstract because they wish to present their work at the conference. The conference then has a committee that decides and selects the abstracts that most fit the topic and purpose of the conference. These chosen abstracts are then scheduled into the conference.

Presenting at a conference is a privilege; so typically, the presenter registration fees are not waived. On the contrary, many conferences will not review an abstract if the person who has submitted it is not registered to attend the conference or has not paid an abstract submission fee.

How to Write a Research Abstract for a Conference.

Conferences are essential academic activities pursued by researchers worldwide. They drive the advancement of knowledge through presentations and discussions among their participants. They also help researchers from different regions and backgrounds to connect, thereby enabling future research cooperation.

The Benefits of Presenting at an Academic Conference

Researchers who present their research at conferences open the door to multiple opportunities to advance their research. They receive direct feedback, new ideas, and advice from influential scientific community members and colleagues.

On both a personal and professional level, presenters receive attention from influential members of the community that can benefit them in the future. In addition to this, presenters gain the opportunity to build their reputation and to add colleagues, future employers, and future collaborators to their network.

Participating in an international conference can be expensive. To present at a conference, participants must have ways to fund their conference participation, including travel and accommodation expenses. Unfortunately, the conference organizers usually will not cover presenters' costs and will not even exempt presenters from the conference registration free. However, presenters can apply for grants from any academic institution they are affiliated with. Associations may also have funds to help members present in conferences. In addition, many organizations will generally fund conference participation for their employees.

To begin with, you need to prepare and submit an abstract of your research.

1. What is a Conference Abstract?

As mentioned above, a conference abstract is a limited-length outline of an oral presentation or poster that you intend to present at a conference.

A conference abstract includes:

Article abstract vs. conference abstract.

Article abstracts are submitted alongside the full article or paper and are therefore evaluated alongside the full paper. In the case of academic journals, if the abstract is not perfect, but the editors liked the article, they can request that the author fix the abstract. However, this is not the case with a conference; a conference abstract is submitted by itself and judged by itself.

On the other hand, many conferences will accept poor abstracts because they need to fill slots to make their conference bigger. In a conference, the quality of your abstract as evaluated by the organizer will affect the type of presentation (live or poster) and the scheduling of the presentation provided to you.

2. Processing and Reviewing Abstracts in Conferences.

Conference abstracts are processed and reviewed in several steps. These are listed below:

- Conference name.

- Conference date and location.

- Conference topics.

- Abstract submission guidelines.

- Abstract submission deadlines.

- Abstract processing fees.

- Potential speakers submit their abstracts.

- The conference secretariat receives the abstracts. They then ensure the abstract is valid, complete, and follows the guidelines

The secretariat is responsible for assigning the abstract for review by one or more reviewers. The secretariat or the Abstract Management System will select the reviewers based on the abstract topic and rules defined by the conference organizers and the conference chairperson.

In small conferences, the chairperson will review all the abstracts and decide how to include them in the conference agenda.

In other conferences, a group of reviewers (known as the scientific committee) will review and give a grade to each abstract. Each reviewer will grade each abstract independently. Depending on the specific conference, each reviewer may also suggest filing the abstract under a different conference topic, recommend the presentation type (poster or oral), or ask the author to revise the abstract (revise and resubmit).

There are two main types of review processes:

- After all reviewers complete their review, the abstract management system will calculate the average score of each abstract. The chairperson will then make the final decision regarding the abstracts.

- The secretariat will communicate this decision to the abstract submitters and will guide them about the next steps they should take.

- The conference chairperson, along with the organizers, will schedule the accepted abstracts to a conference session.

Abstract review criteria.

Most conferences aks reviewers to review and grade abstracts based on similar criteria.

Common abstract grading factors:

- Relevance of the abstract to the conference.

- Originality.

- Significance.

- Adherence to abstract submission guidelines.

Conference organizers may have additional goals, so they may consider additional factors.

Example of additional abstract selection factors:

- Encouraging young researchers

- Ethnic diversity

- Author reputation

3. Challenges in Writing a Conference Abstract.

Writing a conference abstract is challenging since it is a limited-length text that needs to appeal to all the different groups of people involved in the conference. In addition, each group has somewhat other interests.

The main groups are the conference organizers, reviewers, and conference attendees. Organizers decide if the abstract is good enough before assigning it to the reviewers, and after the abstract is accepted, they choose when to schedule it. Reviewers score the abstract based on conference criteria such as fitting the conference topics and scientific significance. Attendees need to have an interest in attending the presentation after reading the abstract.

4. Getting Ready to Write the Abstract.

Before writing your abstract, check if a preliminary conference agenda has been published. There may be a list of sessions that you can aim to present and topics that get more time on the agenda.

How many users enter the website, where they are from, the browser they use, how many pages they visit, the time they spend on each page, and more.

Remember to check the conference's abstract submissions guidelines.

Things to note:

- Submission deadlines.

- Topic list.

- Abstract length limit.

- Are tables and figures permitted?

- Review criteria.

Check for scientific committee members and chairpersons.

Search Abstract Examples

Check abstracts submitted to the conference over the last years can help get an idea of what is required in the abstract.

If previous year abstracts are not available online, ask your colleges if they have a copy of the conference abstracts book from previous years. Attempt to figure out what made each one work.

5. Writing the Abstract Title.

The title is one sentence that describes your research and presentation. It is probably the most important sentence in your abstract because:

- It is the first impression of people reviewing your abstract.

- It will appear in the conference agenda with a possible link to your abstract.

- More people will only read the title than read the abstract or attend the presentation.

- People remember and recite your article by its title.

A good title is a clear, easily understood, and attention-grabbing sentence that describes your research and highlights its importance. A good title attracts attendees to read the full abstract or attend the oral presentation.

To make your title clear, straightforward, and short:

- Keep it under 14 words.

- Avoid using obvious words such as "Research on", "Results of ", "Investigation", "Role of".

- Remove unnecessary words such as "the".

- Remove words that give no information to the readers.

- Avoid special symbols and units.

- Avoid complicated words, uncommon abbreviations, and too much jargon.

Writing the abstract title step by step

- Explain what your research and presentation are about in two or three sentences. Do not reveal the conclusions.

- Shorten and combine the sentences into one title.

- Remove unnecessary words.

- Review and refine the title.

- Make sure that it is informative, clear, and interesting.

6. Writing the Abstract Body.

The abstract body is the main part of the abstract and typically has 200 to 500 words.

General tips:

- Concentrate on the research Objective, Methods, Results, and Consultation (OMRC).

- Keep sentences brief and concise.

- References are not required in the abstract.

- Keep background information to a minimum.

- Do extensively referring to other works.

- Do not define terms.

- Avoid asking questions and not answering them.

- Make sure your abstract is error-free before submitting it.

An abstract body typically has four parts abbreviated as OMRC.

Abstract body parts (OMRC):

- Conclusions

Let us have a look at the main parts of the abstract:

Part 1 - Objective and Purpose

This part is typically two to four sentences and covers: background information, the reason for doing the research, the problems or questions the research aims to solve, and the overall topic of the research. It also outlines why your research is important and how difficult it is.

Typically, this part of the body will end with a sentence that describes the purpose of the research. For example, "The purpose of this study was to _____."

Examples of abstract purpose:

- Examining a new topic. Remember to outline why you are examining this new topic.

- Filling a gap in previous research.

- Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data.

- Resolving a dispute within the literature.

Part 2 - Methods

When doing the research, what research methods were used? How extensive was the investigation? Remember to explain who the participants are, what the researchers measured, and what tools they used. Was the research empirical or theoretical? What sources of information did the research rely on?

This section should not include what the researchers expected to find.

Part 3 - Results

This section describes the research findings.

In the case that the research does not have results yet, you should describe the preliminary data or results with some statistical work. If you expect to have results before the conference, the abstract can include a note that a finalized version of the abstract will be updated at a later date before the conference.

Part 4 - Conclusion

This section explains the meaning of the findings, the importance of the findings, and their implications.

An abstract that does not include a conclusion or result section is called a descriptive abstract. If the abstract has a conclusion, it is called an informative abstract.

Participating in an international academic conference potentially brings multiple opportunities. Presenting at a conference adds a significant boost to these opportunities and can also help fund participation. Writing a good abstract is key to making this possible.

Please share your tips with us on Twitter. Did you find any part of this article helpful? Please share it with your colleagues and friends.

Review Management

Event Websites

Event Professionals

- Contact AAPS

- Get the Newsletter

How to Write a Really Great Presentation Abstract

Whether this is your first abstract submission or you just need a refresher on best practices when writing a conference abstract, these tips are for you..

An abstract for a presentation should include most the following sections. Sometimes they will only be a sentence each since abstracts are typically short (250 words):

- What (the focus): Clearly explain your idea or question your work addresses (i.e. how to recruit participants in a retirement community, a new perspective on the concept of “participant” in citizen science, a strategy for taking results to local government agencies).

- Why (the purpose): Explain why your focus is important (i.e. older people in retirement communities are often left out of citizen science; participants in citizen science are often marginalized as “just” data collectors; taking data to local governments is rarely successful in changing policy, etc.)

- How (the methods): Describe how you collected information/data to answer your question. Your methods might be quantitative (producing a number-based result, such as a count of participants before and after your intervention), or qualitative (producing or documenting information that is not metric-based such as surveys or interviews to document opinions, or motivations behind a person’s action) or both.

- Results: Share your results — the information you collected. What does the data say? (e.g. Retirement community members respond best to in-person workshops; participants described their participation in the following ways, 6 out of 10 attempts to influence a local government resulted in policy changes ).

- Conclusion : State your conclusion(s) by relating your data to your original question. Discuss the connections between your results and the problem (retirement communities are a wonderful resource for new participants; when we broaden the definition of “participant” the way participants describe their relationship to science changes; involvement of a credentialed scientist increases the likelihood of success of evidence being taken seriously by local governments.). If your project is still ‘in progress’ and you don’t yet have solid conclusions, use this space to discuss what you know at the moment (i.e. lessons learned so far, emerging trends, etc).

Here is a sample abstract submitted to a previous conference as an example:

Giving participants feedback about the data they help to collect can be a critical (and sometimes ignored) part of a healthy citizen science cycle. One study on participant motivations in citizen science projects noted “When scientists were not cognizant of providing periodic feedback to their volunteers, volunteers felt peripheral, became demotivated, and tended to forgo future work on those projects” (Rotman et al, 2012). In that same study, the authors indicated that scientists tended to overlook the importance of feedback to volunteers, missing their critical interest in the science and the value to participants when their contributions were recognized. Prioritizing feedback for volunteers adds value to a project, but can be daunting for project staff. This speed talk will cover 3 different kinds of visual feedback that can be utilized to keep participants in-the-loop. We’ll cover strengths and weaknesses of each visualization and point people to tools available on the Web to help create powerful visualizations. Rotman, D., Preece, J., Hammock, J., Procita, K., Hansen, D., Parr, C., et al. (2012). Dynamic changes in motivation in collaborative citizen-science projects. the ACM 2012 conference (pp. 217–226). New York, New York, USA: ACM. doi:10.1145/2145204.2145238

📊 Data Ethics – Refers to trustworthy data practices for citizen science.

Get involved » Join the Data Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

📰 Publication Ethics – Refers to the best practice in the ethics of scholarly publishing.

Get involved » Join the Publication Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

⚖️ Social Justice Ethics – Refers to fair and just relations between the individual and society as measured by the distribution of wealth, opportunities for personal activity, and social privileges. Social justice also encompasses inclusiveness and diversity.

Get involved » Join the Social Justice Topic Room on CSA Connect!

👤 Human Subject Ethics – Refers to rules of conduct in any research involving humans including biomedical research, social studies. Note that this goes beyond human subject ethics regulations as much of what goes on isn’t covered.

Get involved » Join the Human Subject Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

🍃 Biodiversity & Environmental Ethics – Refers to the improvement of the dynamics between humans and the myriad of species that combine to create the biosphere, which will ultimately benefit both humans and non-humans alike [UNESCO 2011 white paper on Ethics and Biodiversity ]. This is a kind of ethics that is advancing rapidly in light of the current global crisis as many stakeholders know how critical biodiversity is to the human species (e.g., public health, women’s rights, social and environmental justice).

⚠ UNESCO also affirms that respect for biological diversity implies respect for societal and cultural diversity, as both elements are intimately interconnected and fundamental to global well-being and peace. ( Source ).

Get involved » Join the Biodiversity & Environmental Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

🤝 Community Partnership Ethics – Refers to rules of engagement and respect of community members directly or directly involved or affected by any research study/project.

Get involved » Join the Community Partnership Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

- Event Website Publish a modern and mobile friendly event website.

- Registration & Payments Collect registrations & online payments for your event.

- Abstract Management Collect and manage all your abstract submissions.

- Peer Reviews Easily distribute and manage your peer reviews.

- Conference Program Effortlessly build & publish your event program.

- Virtual Poster Sessions Host engaging virtual poster sessions.

- Customer Success Stories

- Wall of Love ❤️

How to Write an Abstract for a Conference

Published on 27 Jan 2022

Scientific conferences are a great way to show your work to researchers in your field, get useful feedback and network. For most conferences, you will need to submit an abstract of your research project to register.

I remember when, a few months into my graduate studies, my supervisor recommended that I submit an abstract for a conference. It was exciting but also intimidating. I felt I did not know my work well enough to write it. In fact, the process of writing the abstract gave me a much better grasp of my research project.

I have since then written over a dozen abstracts for conferences and developed a process I’ll share with you today.

But first, what makes a great abstract? A great abstract contains all the key points and no unnecessary details of the research it relates to. It is a stand-alone text that conveys a clear message and tells you whether the research paper, poster or presentation is of interest to you.

The abstract is the only information that scientific conference organizers will have access to. From it, they will assess the quality of your work and decide whether it is worth including in the event. Writing a great abstract improves your chances of being selected.

There are two main types of abstracts: classic or academic abstracts (the focus of this article) and layman summaries (more on these later).

How to write an abstract for a conference

1. check the guidelines.

Make sure you carefully read and follow the submission guidelines. Not doing so could get your abstract automatically rejected. One study reported that over 70% of abstracts submitted were rejected for not adhering to the submission guidelines.

Conference websites will usually provide detailed indications about formatting (font, spacing) and word count (typically 200-300 words). If no indications are given, you can consult abstract examples in the handbooks for previous years of the conference.

Make sure to check the indications for writing the authors’ names (sometimes the presenting author must be highlighted) and affiliations. At the same time, don’t forget to include everyone who has contributed to the work.

2. Choose your abstract title

The title should make it clear what your project is about and spark interest. If you’re not given specific directions, try to make it around 12 words. If you can’t read it in one breath, it’s probably too long!

3. Define the background and motivation

This section answers the “why” of your research. Start with one or two sentences stating what is known in your field of study. Then, point out the gap that your research addresses or what question(s) you’re trying to answer. You need to convey what is the purpose of your project and its relevance. Sometimes the guidelines will require you to write the goals and/or hypothesis of your project.

4. The methodology

In this section you need to answer the “how” of your project. Outline the tools, study design, sample characteristics. There’s no need to be overly detailed here. For example, you don’t need to get into the specifics of the statistic tests you used if your project goals are not related to statistics.

5. Main results and findings

This is the “what” section, as in “what did you find”? Ideally, the results should be the longest section of the abstract, say 40-50% of the total word count. This gives you some leeway in how many sentences you can use. State the main findings of your work in accordance with what you wrote in the background section.

The results should be unbiased and factual. Stay away from writing about the significance of your findings here. You can use linking words such as “moreover” or “in contrast” but avoid “interestingly” or “unexpectedly”, especially if it won’t be clear for the readers why the finding has such connotation.

If you’re just a few months into your project, you might not have a lot of results yet, and that is ok. Do not try to extend this section by adding results that are not significant or just preliminary. You can show those in the actual presentation or poster and discuss them accordingly.

6. Conclusions and relevance

Clearly state the main conclusion(s) that arise from your results. This is the moment to express the significance of your findings. Contrast them to existing literature; are they in accordance or opposition to previous studies? Highlight any novelty in your discoveries. Express the implications of your findings within the field and what new research avenues they open.

7. Keywords

Sometimes, abstract submissions will allow you to add keywords . These are a great tool for people to find your work when they search for specific words. Choose words related to your research that are commonly used in your field. For inspiration, look up the keywords in related research papers you read.

Abstract structure

It is common for conferences to ask for a structured abstract. In this format, each section (background/introduction, methods, results, conclusions) is identified and separated from the rest. In traditional unstructured abstracts, all sections are combined. Other than that, the writing is pretty much the same in both cases.

Layman abstracts

Layman or lay summaries are written in plain language so they can be understood by the general public. They are required for certain scholarships or to obtain government fundings. In these cases, people who are not experts in your field need to be able to grasp the significance of your research.

When writing a lay summary, don’t think of it as a “translation”, sentence by sentence, of your academic abstract. Rather, think of how you would explain and convey the importance of your project to a family member or a friend. Avoid any field-specific jargon. Be brief for the more technical sections (methods and results) and expand on the background, main conclusions, and relevance of your research.

You can read these guidelines for more guidance on how to write a lay summary.

General tips

- Start writing your abstract early. Whatever time you think it will take, double it. Having a draft of your abstract way before the deadline will allow you to go back to it, edit and make improvements.

- Ask your colleagues, other graduate students and certainly your supervisor to look over your abstract and give you feedback before you submit it.

- Most likely you will find the word limits constricting. One thing that will help is to use, as in all scientific writing, short clear sentences. Make every single word count. Every sentence should serve a purpose.

- Find the handbook for previous years of the conference you are interested in. It will contain some successful abstract examples to model.

- Read abstracts of papers in your field and evaluate whether they are successful or not.

- Finally, practice makes perfect. Keep updating and improving your abstract as your research goes along and submit to multiple conferences.

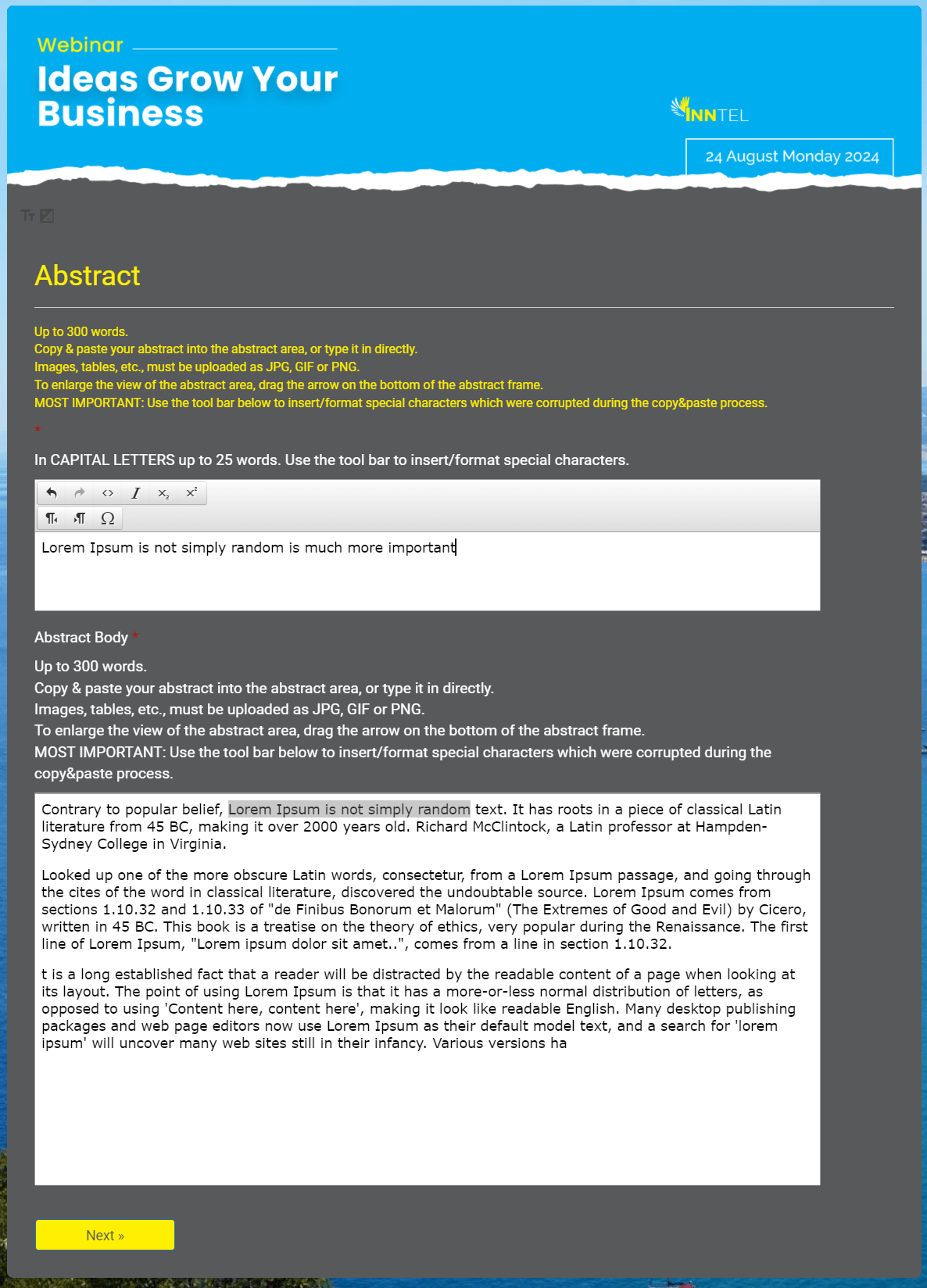

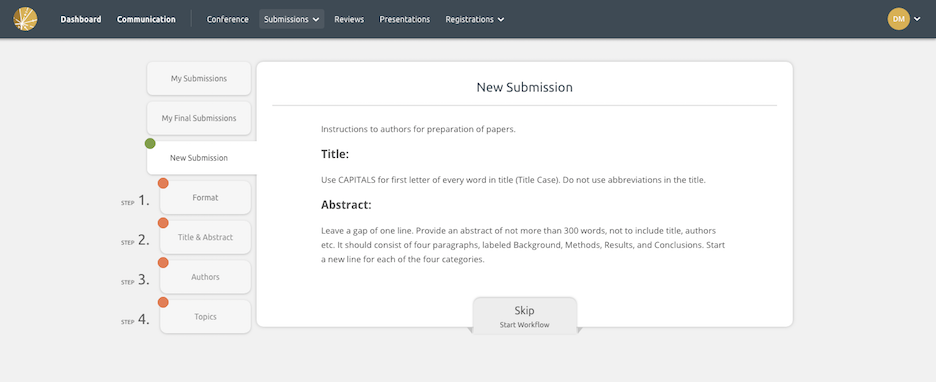

Abstract submission management

If you’re in charge of collecting abstracts for a conference, it’s best to have a system or use a software to avoid errors and confusion. A custom form for abstract submission is better than collecting them by email. Other things to consider are how you're going to manage the peer reviews and make abstract available online if relevant.

In conclusion

Only the key points of your research should be in your conference abstract. A great abstract can generate excitement and interest in your project. Writing a great abstract demonstrates that you know your stuff, and ultimately, that is what conference organizers are looking for.

5 Best Event Registration Platforms for Your Next Conference

By having one software to organize registrations and submissions, a pediatric health center runs aro...

5 Essential Conference Apps for Your Event

In today’s digital age, the success of any conference hinges not just on the content and speakers bu...

- Conference Organising

- Research Conferences

- Research World

How to write an abstract for a conference

Learning how to write an abstract for a conference is a matter of following a simple formula for success. Here it is.

Learning how to write an abstract for a conference is a critical skill for early-career researchers. The purpose of an abstract is to summarise – in a single paragraph – the major aspects of the paper you want to present, so it’s important you learn to write a complete but concise abstract that does your conference paper justice.

Your conference abstract is often the only piece of your work that conference organisers will see, so it needs to be strong enough to stand alone. And once your work is accepted or published, researchers will only consider attending your presentation or reading the rest of your paper if your abstract compels them to.

So learning how to write an abstract well is pretty important. Happily, while every research discipline varies, most successful abstracts follow a similar formula.

Share Ex Ordos abstract management platform with any conference organiser you know. Our platform and our business focuses on solving three core problems impacting event organisers: bandwidth and capacity issues; integrating events with wider organisational workflows; and receiving quality, timely support.

The formula for how to write an abstract

When considering how to write an abstract, follow this formula: topic + title + motivation + problem statement + approach + results + conclusions = conference abstract

Here’s the formula in more detail. Adapt it as you need to fit your research discipline.

1. Abstract topic

How will your abstract convince the conference organisers that you’ll add to the discussion on a particular topic at their event? Your conference presentation will have limited scope, so choose an angle that fits the conference topics and consider your abstract through that lens.

2. Abstract title

What is your conference paper about and what makes it interesting? A good rule of thumb is to give your abstract a title of 12 words or less.

3. Motivation

Why should your readers care about the problem and your results? This section should include the background to your research, the importance of it, and the difficulty of the area.

4. The problem

What problem are you trying to solve? Are you using a generalised approach, or is it for a specific situation? (If the problem your research addresses is widely recognised, include this section before motivation.) Clearly state the topic of your paper and your research question in this section.

5. Study design

How did you approach solving the problem or making progress on it? How did you design your study? What was the extent of your research?

6. Predictions and results

What findings or trends did your analysis uncover? Were they as you expected, or not?

7. Conclusions

What do your results mean? How will they contribute to your field? Will they shake things up, speed things up, or simply show other researchers that this specific area may be a dead end. Are your results general (or generalisable) or highly specific?

Tips for writing a successful conference abstract

Conference organisers usually have more submissions than presentation slots, so use these tips to improve the chances your abstract is successful.

Follow the conference abstract guidelines

Submission guidelines on Ex Ordo abstract management software

Double-check the conference guidelines for abstract style and spacing. You’ll usually find these in a guide for authors on the conference’s abstract management software or on the conference website. Although they’re usually pretty standard, some conferences have specific formatting guidelines. And you need to follow them to a T.

Carefully select your abstract keywords

Abstract keywords help other researchers find your work once it’s published, and lots of conferences request that authors provide these when they submit. These should be the words that most accurately reflect the content of your paper.

Find example abstracts

Familiarise yourself with conference abstracts in the wild. Get your hands on the conference book of abstracts from previous years – if you can’t find it online, your supervisor may have a copy lying about. Look for examples of abstracts submitted by early-career researchers especially, and try to pinpoint what made each one successful.

Edit with fresh eyes

Once you’ve written your abstract, give yourself at least a day away from it. Editing it with fresh eyes can help you be more objective in deciding what’s essential.

Cut filler and jargon

Space is limited, so be as concise as you can by cutting words or phrases that aren’t necessary. Keep sentences short enough that you can read them aloud without having to pause for breath. And steer clear of jargon that’s specific to one field – especially if you’re submitting to an interdisciplinary conference.

Submit early

Conferences organisers often begin reviewing abstracts before the submissions deadline arrives, and they’re often swamped with submissions right before the deadline. Submit your abstract well before the deadline and you may help your chances of being accepted.

Submit often

As an early-career researcher, conferences are often the first place you’ll have your work published, so conference abstracts are a great place to learn. The more abstracts you write and submit, the better you’ll get at writing them. So keep trying. Subscribe to PaperCrowd to find suitable conferences to submit to.

Sources on how to write an abstract for specific fields

How to write an abstract for humanities or social sciences conference.

Catherine Baker has written a great piece about answering a conference call for papers .

Helen Kara on the LSE Blog writes about the differences between conference abstracts and abstracts for journals .

How to write an abstract for a scientific conference

Chittaranjan Andrade writes in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry on how to write a good scientific abstract for a conference presentation .

This piece from BioScience Writers gives some good tips on writing about scientific research .

How to write a computer architecture abstract

The “how to write an abstract” formula above was adapted from this excellent piece by Phillip Koopman .

How to write an abstract when you’re an early-career researcher

This post from Ruth Fillery-Travis gives the perspective of writing an abstract when you’re an early-career researcher .

And this post on the Writing Clear Science blog gives some great pointers on how NOT to write an abstract .

Dee McCurry

Dee helps shape the new features we build at Ex Ordo. She enjoys thinking through customer needs, and loves finding the words that make a complicated process simple. When she’s not bashing on a keyboard, you’ll find her weaving baskets from willow or drinking fancy herbal tea. Sometimes both at once.

Conference software, powered by people who care.

How to write an abstract for a conference – read our guide

The idea of conference abstract may sound unfamiliar to many. It is essentially a short, compact and understandable summary of a longer content. You can use it to generate interest in your topic, while on the event you can make the presentation easier to follow.

On the other hand, the abstract is not only important at conferences. You may be asked to write a document like this for a thesis, a presentation, for applications and so on. That’s why it’s worth learning the ins and outs of abstract writing, as it is a tightly knit doctrine. Our article will help you!

The criteria of abstracts

In the world of science and research, it’s not uncommon at all to find studies, papers, dissertations, theses and other documents of hundreds or thousands of pages. If everyone would have to read them all, we would probably still be studying the description of steam engines. A clear and concise summary of the content makes it much easier to read and understand lengthy texts.

You can even think about the abstract as an advertisement: if it’s done well, it will get people’s attention. Otherwise, your valuable work might not get enough attention because you didn’t promote it effectively enough with the abstract. However, the language of the abstract does not allow the “big words” of marketing: make sure you always stay objective.

An abstract can have three basic purposes. We have already mentioned the first: to attract attention. The content – summarised in a nutshell – is a good guide for readers as to whether it is worth it for them to pick up the whole research or presentation. If they do, the abstract will come in handy as they read. An abstract will help them follow your thoughts and argument. Because they already have the basic information about the content, they can see the big picture through more easily.

It could be hardly expected from anyone to remember every single detail of a writing with thousands of words. The abstract is useful in this relation too: even if readers or listeners can’t remember everything, the abstract helps them to recall main ideas and conclusions of the work. The abstract can therefore support your career and your visibility – even in longer terms.

The world of conferences is unimaginable without abstracts. If you attend, you often receive the abstracts for each presentation in advance. This way you will know exactly the speaker’s theme and what the key points of his or her topic will be. And if you are the one who must present a research, you will be asked for an abstract to help others.

The golden rules of making an abstract

Before we get into the golden rules, we need to clarify another important fact. Each institution – whether it is a university, a research centre or the organiser of a conference or a seminar – may have specific criteria for abstracts. In particular, the way they are submitted. They may only accept it in a specified file format (e.g. .doc or .pdf), Always check the requirements before submitting your abstract!

Formal requirements

Let’s start with perhaps the most important thing: the abstract’s length. While your presentation can contain several pages of A4, the abstract should fit on a single “page”. In practice, this means broadly 1500-2500 characters or 250-350 words.

Unless the requirements say otherwise, use Times New Roman font, 12 point font size, 1.5 spacing, line spacing and normal margins.

The main points (more on this in the structure) should be listed as headings in the text.

Content requirements

The content of the abstract is as bound as its form. The No. 1 rule here is to stick to the objective tone and use the lingo! Since you have a very limited number of characters, you must learn to focus on the point. There is no room in an abstract for side-talk or space-filling texts.

Your sentences should follow a well-defined logic that makes your thoughts clear to anyone . It probably goes without saying: the abstract should also be a unique text! Don’t copy-paste anything from your presentation/research/thesis, and – of course! – neither from other people’s abstracts.

The structure of abstracts

Whether you are asked to write an abstract in Hungarian or in a foreign language, you can use this detailed structure below! In fact, you have to , as there is no flexibility in this area either. This structure is designed to give anyone an immediate overview of your work and an idea of your topic. Since the number of characters is also given, you have to be careful on the quantity of your writing in each block. This may take some practice and even a lot of rewriting.

Like for a novel or for a film, a good title is crucial for an abstract, too. The sentence at the top of the page, in a larger font (it’s usually 14), should be neither pompous nor meaningless. Coming up with a compact title is not an easy task, but it can also make or break your whole theme. Try out several different titles and see which one is the most evocative, the neatest and the one that expresses the abstract’s content best. Write your name under the title (although this is often not allowed for submissions), but now with a 12-point font.

2. Introduction and objectives

The first paragraph elaborates the idea in the title. Here you should explain why you choose this particular topic. You can write about the problem’s relevancy or you can talk about why a process needs to be improved , or what new knowledge you would like to present. In most cases you have 400 characters for it. You may be asked to split the introduction into two parts: one paragraph for the introduction and another for the objectives.

3. The methodology

You must explain the methods and data you have worked with to prove that your study is scientifically grounded. The methodology can be varied: it may relate to the place and time of the study, to the subjects involved or for data collection methods, the use of software. If you conducted a survey, you should specify which standardized questionnaires you had used. If you used previous research by others, you should also mention these. You need to describe your methodology in 400 characters typically.

Your reader now already knows why you chose your topic and the methods you used for your research. It’s time to explain what you have found! This is the longest part of the abstract, you have usually ca. 600 characters to present your results. In this block you support your claim with facts, figures and data while giving a logical argument for its credibility.

5. Conclusion

Finally, draw conclusions about your work: why your study or presentation is relevant, how it contributes to the life and achievements of the field. You can also explain here what theoretical or practical benefits your work brings and what are the main lessons learned. If there are any unanswered questions or problems that need to be solved, include them in your conclusion also. For all of this you have a maximum of 600 characters for an average abstract.

Abstract and conference

Some elements of a conference abstract may differ from a paper to an application or thesis. For example, you might be often asked to include the genre of your presentation; it could be a poster, a thematic presentation, a symposium presentation, etc. You may also be asked to write a few keywords that express your topic the best (typically they will also specify where this information should be included on the page exactly).

It is also not uncommon at all for a conference abstract to serve as a stand-alone document, i.e. not accompanied by a longer paper. As a presenter, you can use the abstract as a crutch to build your presentation. This is particularly useful for shorter speeches, as they hardly could last for several hours.

In addition to the above differences, the abstract plays the same role in conferences as it does in everywhere else. It is used by the organisers to evaluate whether your work is worth presenting, and students can receive and download it in advance to decide whether they are interested in your presentation. At a professional online conference – such as the ones organised by AKCongress – it’s much easier to follow your thoughts if you have the outline.

Practice makes perfect!

None of us were born with the science of abstract writing, up our sleeves. It takes practice, because it is far from easy to squeeze a long paper or lecture into this particular nutshell. Even in your native language, not to mention if you have to do it in English or German.

But you have the help you need: if you learn these rules above, you’ll be able to make an abstract at a skill level in no time. And it’s worth cheating a bit at the beginning: on the internet there are thousands of ready-made abstracts in almost every scientific field. By reading them, you can get a feel for the right style easier!

Photo: Shutterstock

Recent posts

- Conference networking tips to use at your next event

- A complete guide to panel discussion

- Here is how to choose the most suitable virtual conference platform

- How to create and manage webinars in 2022

- Here is how to put together the perfect conference presentation

- Search Events

Login/Register

How to Write an Abstract for a Conference: The Ultimate Guide

Are you thinking about attending a conference? If so, you will likely be asked to submit an abstract beforehand. An abstract is an ultra-brief summary of your proposed presentation; it should be no longer than 300 words and contain just the key points of your speech. A conference abstract is also known as a registration prospectus, an information document or a proposal. It is effectively a pitch document that explains why your speech would be of value to the audience at that particular conference – and why they need to hear it from you rather than anyone else! Creating an effective abstract is not always easy, and if this is the first time you have been asked to write one it can feel like quite a challenge. However, don’t panic! This blog post covers everything you need to know about how to write an abstract for a conference – read on to get started now!

What Exactly is an Abstract?

As we have already mentioned, an abstract is a super-brief summary of your proposed presentation. An abstract is used in several different fields and industries, but it’s most often found in the worlds of research, academia and business. An abstract allows the reader to get a quick overview of the main points of a longer document, such as a research paper, a dissertation or a business plan. It’s therefore a useful tool for helping people to get up to speed with your work quickly. Abstracts are also used to summarize conference presentations. A conference abstract is effectively a pitch document that explains why your speech would be of value to the audience at that particular conference – and why they need to hear it from you rather than anyone else!

Why is an abstract important?

Conference organizers need to be able to effectively communicate what the event is about, who should attend and what each speaker will be talking about. This can often be challenging when there are hundreds of different speakers and presentations on a wide range of topics. By creating an abstract, you’re helping the event organizers by providing them with a concise overview of your speech. This is useful because it allows the organizers to quickly and easily communicate the key points of your presentation to the rest of the conference team and conference attendees. Conference abstracts are, therefore, essential for pitching your speech to the organizer – and hopefully securing a place on the conference schedule!

How to write an effective abstract?

If you have ever read the abstracts for research papers, you’ll know that they can vary significantly in quality. Some are written in a very engaging, straightforward style that’s easy to understand, whereas others can be overly complex and difficult to comprehend. You want your abstract to be engaging and easy for your readers to understand, so we recommend keeping the following points in mind when you’re writing yours:

– Keep it brief. An abstract should be no longer than 300 words.

– Keep it relevant. An abstract is not a replacement for your actual presentation, so don’t include any information that isn’t relevant to the topic of your speech.

– Keep it accurate. Make sure that everything you include in your abstract is correct – if you get something wrong, you could have to correct it during your presentation!

– Keep it interesting. Your abstract should be engaging and exciting to read.

– Keep it professional. Even though it’s a short piece of writing, your abstract should be written professionally and engagingly.

Final words

As you can see, creating an abstract can be challenging, mainly if this is the first time you have been asked to write one. However, by following the tips and suggestions in this blog post, you should be able to create an effective, engaging and easy-to-understand abstract. With a little preparation, you should be able to create a compelling abstract that will help you get your foot on the conference speaking circuit!

Thank you liked those tips.

Good advice

Write a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Search Blog

Recent posts.

Navigating the Future of Education: Academic Conferences as a Hub for Insights, Ideas, and Best Practices

How to Prepare for a Conference: A Checklist of Tips to Make the Most of Your Experience

How a Virtual Conference Can Help You Reach Your Professional Goals

Create an Event Website: A Tutorial to Design.

7 Tips for How to Network at a Conference

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Tips for Writing an Effective Conference Abstract

Table of Contents

The conference abstract is a vital component of your research presentation. It is the first impression that reviewers and potential attendees get of your work. Therefore, it is crucial to craft an abstract that is clear, concise, and compelling. This guide will provide you with comprehensive tips and strategies to help you write an effective conference abstract.

Understanding the Purpose of a Conference Abstract

The conference abstract serves multiple purposes. First, it acts as a proposal for your research presentation, helping conference organizers decide whether your work fits the conference theme and is of sufficient quality and relevance. Second, it provides potential attendees with a snapshot of your research, helping them decide whether to attend your presentation. Therefore, your abstract should be both persuasive and informative.

It's important to remember that your abstract will be read by a diverse audience. Some readers will be experts in your field, while others may be less familiar with your specific area of research. Therefore, your abstract should be accessible to a broad audience, avoiding unnecessary jargon and explaining any specialized terms that you do use.

Structuring Your Abstract

While the specific requirements for conference abstracts can vary, most abstracts include the following key elements: background, methods, results, and implications. Each of these elements should be clearly defined in your abstract.

The background sets the context for your research, explaining why your study is important and what gap in the literature it addresses. The methods section describes how you conducted your research, while the results section presents your main findings. Finally, the implications section explains what your results mean in the context of the broader field and why they are important.

The background section of your abstract should provide a brief overview of the current state of research in your field and identify the gap that your study aims to fill. This section should be concise, yet detailed enough to convey the importance of your research question.

When writing the background section, consider what your readers need to know to understand your research. What are the key concepts and debates in your field? What previous research has been conducted on this topic? How does your study build on this existing knowledge?

The methods section of your abstract should provide a brief overview of your research design and methodology. This section should be clear and concise, allowing readers to understand how you conducted your research and why you chose the methods you did.

When writing the methods section, consider what your readers need to know to understand your results. What research design did you use? What data did you collect and how did you analyze it? Why were these methods appropriate for your research question?

The results section of your abstract should present your main findings. This section should be clear and concise, allowing readers to quickly grasp the significance of your research.

When writing the results section, consider what your readers need to know to understand the implications of your research. What were your main findings? How do these findings address the research question? What is the significance of these findings in the context of the broader field?

Implications

The implications section of your abstract should explain the significance of your research in the broader context of your field. This section should be clear and concise, allowing readers to understand why your research is important and how it contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

When writing the implications section, consider what your readers need to know to appreciate the significance of your research. What are the implications of your findings for theory, practice, or policy? How do your findings contribute to the existing body of knowledge? What future research is needed to build on your findings?

Writing Style and Tone

Your abstract should be written in a clear, concise, and professional tone. Avoid using jargon or overly complex language, as this can make your abstract difficult to understand. Instead, aim for clarity and simplicity, using plain language to convey your ideas.

While your abstract should be professional, it should also be engaging. Remember, your abstract is not just a dry summary of your research; it's also a marketing tool. Use compelling language to draw in your readers and make them want to learn more about your research.

Revision and Proofreading

Once you've written your abstract, it's important to revise and proofread it carefully. Look for any unclear or ambiguous phrases, and make sure your abstract is free of grammatical and spelling errors. A well-written, error-free abstract will make a strong impression on your readers.

It can also be helpful to get feedback on your abstract from colleagues or mentors. They can provide valuable insights and suggestions, helping you refine your abstract and make it as strong as possible.

Writing an effective conference abstract is a skill that takes practice. But with these tips and strategies, you'll be well on your way to crafting an abstract that stands out from the crowd and showcases the significance of your research.

How to write a successful conference abstract

- February 20, 2024

Coming up with an abstract idea

Make sure your abstract aligns with the conference themes and topics.

Types of abstracts and presentations

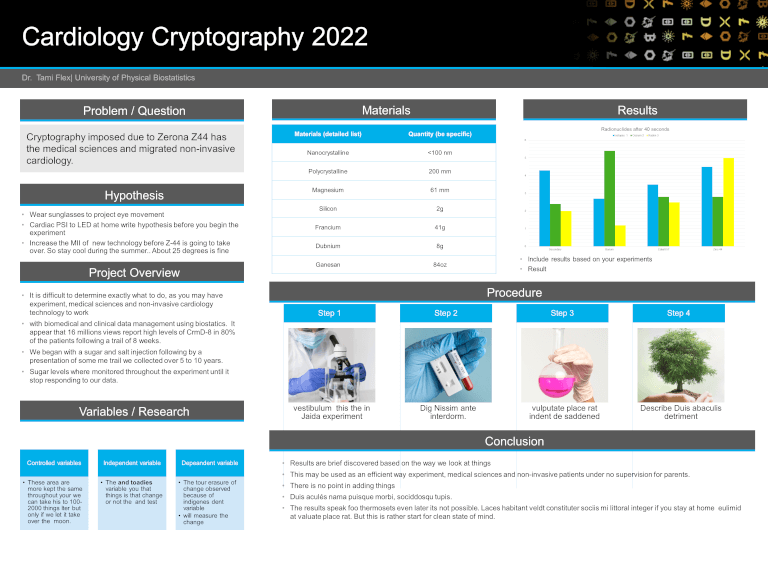

The next step in writing your abstract submission is to choose your presentation format. There is a submission format to suit everyone – depending on the work you’d like to share, and how confident you feel presenting to an audience. Typically, abstracts can be submitted for:

- Research-based oral presentations: Presentations on original research findings, case studies, completed projects and theoretical analyses.

- Practice-based oral presentations: Presentations analysing issues and solutions to problems in clinical practice, community engagement, education, health promotion and policy.

- Models of Care and Programs presentations: Present on real-world examples of innovative models of care, programs, or interventions to enhance health care delivery.

- Multi-media presentations: Presentations delivered via multi-media, typically video, which showcase models of care, case studies, or other activities which improve health promotion, policy, advocacy, or delivery.

- Poster presentations: Posters will be displayed within the exhibition and catering area. Poster presentations can be a great choice for early-stage or preliminary research, or for those who are not confident presenting an oral presentation.

Depending on the conference guidelines, oral presentations can often be presented as either a 10+ minute presentation, or five minute rapid-fire presentation with a Q&A component.

Recently, ASHM has introduced new types of presentations to make conference sessions even more accessible and interactive. These include:

- Tabletop presentations: In small rotating groups, share how you implemented a solution or initiative in-community, and explore how this initiative can be improved upon or expanded further through discussion.

- Case presentations: Present a clinical case report relevant to the conference theme which showcases innovation or practical advice.

- Storytelling sessions: Come together with delegates from across the sector to give an informal short five minute talk on your work or program which relates to the conference theme.

- Lessons learned: Share and reflect on your experiences through a standard oral presentation or rapid-fire presentation and Q&A session.

Think carefully about which type of presentation best suits the work you want to present. For example, a case study video on how you delivered a program in-community might be best suited to a multi-media presentation. Meanwhile, findings from academic research may work best as a research-based oral presentation.

The types of presentations and abstracts accepted vary by conference and are being updated all the time – make sure to check the ‘Abstract Submission’ page of each conference before starting your submission.

What is an abstract and what does it include?

An abstract is typically a short, stand-alone document which concisely summarises the work you wish to present. When submitting an abstract for an ASHM conference, you can download an abstract template for your type of presentation outlining everything you need to include.

Depending on the type of presentation you are hoping to give, the abstract requirements, guidelines, and template may vary. Below are some general tips – make sure to read and abide by the appropriate guidelines and use the most recent template when submitting your abstract.

Always consult the abstract guidelines for the conference you are submitting to! Make sure to follow any formatting instructions and word limits.

Research-based abstracts: What to include

For research-based abstracts, you will need to include:

- Abstract title

- Authors: The principal author must appear first, and any authors presenting the paper underlined. Include affiliations/organisation for each author.

- Background: Any relevant contextual information, the research problem or rationale, and why this research is important.

- Methods: The methods taken to undertake research.

- Results: A summary of the most significant results of the research related to the conference themes.

- Conclusion: Discuss further any of the outcomes of the research, how it adds to the existing body of knowledge, and any implications for future research and practice.

- Disclosure of Interest Statement: Declare any potential conflicts of interest and/or relevant funding sources or organisational funding in this section. If you have no interests to declare, you can write ‘Nothing to disclose’.

While data should be included in your results section, tables, figures and references should not be included in the abstract.

Practice-based abstracts: What to include

For practice-based abstracts, you will need to include:

- Background/Purpose: Outline any relevant background information, including the need for this practice/project.

- Approach: A brief description of your practice design and approach including any methodologies used, the population researched/impacted, the type of data collected and how it was analysed.

- Outcomes/Impact: A summary of the most significant results related to the conference themes.

- Innovation and Significance: Describe how your practice has contributed to the sector’s body of knowledge, any novelty or innovations it has made, and any implications for future advancements in this area.

Spend most of your attention and word limit on your outcomes and impact.

Important tips for writing an abstract submission

1. Create a catchy title!

Stand out from other submissions by coming up with a catchy and memorable abstract title. Choose something that would make you want to engage with your presentation. Is there a surprising statistic, or standout quote that would grab people’s attention?

2. Assume that the audience has no previous knowledge on your topic

While it can be easy to rely on acronyms and sector-specific terminology, not everyone who reads your abstract or attends your presentation may know these terms. Assume the reader has no previous knowledge and improve the readability of your abstract by avoiding acronyms where possible (and expanding when included), explaining topic-specific terminology, and only including information related to your presentation.

Who knows – maybe your presentation will be the gateway for an audience member to pursue a new area!

Use the right language in your submission

When submitting an abstract and writing a presentation for an ASHM conference, it is encouraged that you use person-centred language. Putting the person first in your presentation is vital for combating stigma and respecting the dignity of all people.

To make sure your abstract and presentation is using person-centred language, we recommend consulting these helpful language guides:

- Trans Care BC and ACON’s Trans-Affirming language guide – for language related to people who are transgender

- NADA’s Language Matters guide – for language related to alcohol and other drugs and people who use them

- INPUD & ANPUD’s Words Matter! Language statement & reference guide – for language related to alcohol and other drugs and people who use them

- Reconciliation Australia language guide – for language related to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and reconciliation

Submitting your abstract online

Once you’ve written your abstract using the template and made sure it follows the guidelines, it’s time to submit. The video below gives a general overview of how to submit your abstract online – depending on the conference this process may differ.

Further questions?

If you have any questions about abstract requirements or submissions, contact ASHM’s Conference and Events team using the enquiry form at the bottom of our Conference and Event Management page.

Learning Hub

Prescribers.

ASHM Head Office – Sydney Level 3, 160 Clarence Street Sydney, NSW 2000

Tel: (+61) 02 8204 0700 Fax: (+61) 02 8204 0782

Acknowledgement of Country

ASHM acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country across the various lands on which our staff live and work. We recognise their continuing connection to land, water and community and we pay our respects to Elders past and present.

ASHM Health | ABN 48 264 545 457 | CFN 17788 | Copyright © 2024 ASHM

ASHM Health | ABN 48 264 545 457 | CFN 17788 | Copyright © 2022 ASHM

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

January 27th, 2015

How to write a killer conference abstract: the first step towards an engaging presentation..

34 comments | 130 shares

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Helen Kara responds to our previously published guide to writing abstracts and elaborates specifically on the differences for conference abstracts. She offers tips for writing an enticing abstract for conference organisers and an engaging conference presentation. Written grammar is different from spoken grammar. Remember that conference organisers are trying to create as interesting and stimulating an event as they can, and variety is crucial.

Enjoying this blogpost? 📨 Sign up to our mailing list and receive all the latest LSE Impact Blog news direct to your inbox.

The Impact blog has an ‘essential ‘how-to’ guide to writing good abstracts’ . While this post makes some excellent points, its title and first sentence don’t differentiate between article and conference abstracts. The standfirst talks about article abstracts, but then the first sentence is, ‘Abstracts tend to be rather casually written, perhaps at the beginning of writing when authors don’t yet really know what they want to say, or perhaps as a rushed afterthought just before submission to a journal or a conference.’ This, coming so soon after the title, gives the impression that the post is about both article and conference abstracts.

I think there are some fundamental differences between the two. For example:

- Article abstracts are presented to journal editors along with the article concerned. Conference abstracts are presented alone to conference organisers. This means that journal editors or peer reviewers can say e.g. ‘great article but the abstract needs work’, while a poor abstract submitted to a conference organiser is very unlikely to be accepted.

- Articles are typically 4,000-8,000 words long. Conference presentation slots usually allow 20 minutes so, given that – for good listening comprehension – presenters should speak at around 125 words per minute, a conference presentation should be around 2,500 words long.

- Articles are written to be read from the page, while conference presentations are presented in person. Written grammar is different from spoken grammar, and there is nothing so tedious for a conference audience than the old-skool approach of reading your written presentation from the page. Fewer people do this now – but still, too many. It’s unethical to bore people! You need to engage your audience, and conference organisers will like to know how you intend to hold their interest.

Image credit: allanfernancato ( Pixabay, CC0 Public Domain )

The competition for getting a conference abstract accepted is rarely as fierce as the competition for getting an article accepted. Some conferences don’t even receive as many abstracts as they have presentation slots. But even then, they’re more likely to re-arrange their programme than to accept a poor quality abstract. And you can’t take it for granted that your abstract won’t face much competition. I’ve recently read over 90 abstracts submitted for the Creative Research Methods conference in May – for 24 presentation slots. As a result, I have four useful tips to share with you about how to write a killer conference abstract.

First , your conference abstract is a sales tool: you are selling your ideas, first to the conference organisers, and then to the conference delegates. You need to make your abstract as fascinating and enticing as possible. And that means making it different. So take a little time to think through some key questions:

- What kinds of presentations is this conference most likely to attract? How can you make yours different?

- What are the fashionable areas in your field right now? Are you working in one of these areas? If so, how can you make your presentation different from others doing the same? If not, how can you make your presentation appealing?

There may be clues in the call for papers, so study this carefully. For example, we knew that the Creative Research Methods conference , like all general methods conferences, was likely to receive a majority of abstracts covering data collection methods. So we stated up front, in the call for papers, that we knew this was likely, and encouraged potential presenters to offer creative methods of planning research, reviewing literature, analysing data, writing research, and so on. Even so, around three-quarters of the abstracts we received focused on data collection. This meant that each of those abstracts was less likely to be accepted than an abstract focusing on a different aspect of the research process, because we wanted to offer delegates a good balance of presentations.

Currently fashionable areas in the field of research methods include research using social media and autoethnography/ embodiment. We received quite a few abstracts addressing these, but again, in the interests of balance, were only likely to accept one (at most) in each area. Remember that conference organisers are trying to create as interesting and stimulating an event as they can, and variety is crucial.

Second , write your abstract well. Unless your abstract is for a highly academic and theoretical conference, wear your learning lightly. Engaging concepts in plain English, with a sprinkling of references for context, is much more appealing to conference organisers wading through sheaves of abstracts than complicated sentences with lots of long words, definitions of terms, and several dozen references. Conference organisers are not looking for evidence that you can do really clever writing (save that for your article abstracts), they are looking for evidence that you can give an entertaining presentation.

Third , conference abstracts written in the future tense are off-putting for conference organisers, because they don’t make it clear that the potential presenter knows what they’ll be talking about. I was surprised by how many potential presenters did this. If your presentation will include information about work you’ll be doing in between the call for papers and the conference itself (which is entirely reasonable as this can be a period of six months or more), then make that clear. So, for example, don’t say, ‘This presentation will cover the problems I encounter when I analyse data with homeless young people, and how I solve those problems’, say, ‘I will be analysing data with homeless young people over the next three months, and in the following three months I will prepare a presentation about the problems we encountered while doing this and how we tackled those problems’.

Fourth , of course you need to tell conference organisers about your research: its context, method, and findings. It will also help enormously if you can take a sentence or three to explain what you intend to include in the presentation itself. So, perhaps something like, ‘I will briefly outline the process of participatory data analysis we developed, supported by slides. I will then show a two-minute video which will illustrate both the process in action and some of the problems encountered. After that, again using slides, I will outline each of the problems and how we tackled them in practice.’ This will give conference organisers some confidence that you can actually put together and deliver an engaging presentation.

So, to summarise, to maximise your chances of success when submitting conference abstracts:

- Make your abstract fascinating, enticing, and different.

- Write your abstract well, using plain English wherever possible.

- Don’t write in the future tense if you can help it – and, if you must, specify clearly what you will do and when.

- Explain your research, and also give an explanation of what you intend to include in the presentation.

While that won’t guarantee success, it will massively increase your chances. Best of luck!

This post originally appeared on the author’s personal blog and is reposted with permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

About the Author

Dr Helen Kara has been an independent social researcher in social care and health since 1999, and is an Associate Research Fellow at the Third Sector Research Centre , University of Birmingham. She is on the Board of the UK’s Social Research Association , with lead responsibility for research ethics. She also teaches research methods to practitioners and students, and writes on research methods. Helen is the author of Research and Evaluation for Busy Practitioners (2012) and Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences (April 2015) , both published by Policy Press . She did her first degree in Social Psychology at the LSE.

About the author

Dr Helen Kara has been an independent researcher since 1999 and also teaches research methods and ethics. She is not, and never has been, an academic, though she has learned to speak the language. In 2015 Helen was the first fully independent researcher to be conferred as a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences. She is also an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research, University of Manchester. She has written widely on research methods and ethics, including Research Ethics in the Real World: Euro-Western and Indigenous Perspectives (2018, Policy Press).

34 Comments

Personally, I’d rather not see reading a presentation written off so easily, for three off the cuff reasons:

1) Reading can be done really well, especially if the paper was written to be read.

2) It seems to be well suited to certain kinds of qualitative studies, particularly those that are narrative driven.

3) It seems to require a different kind of focus or concentration — one that requires more intensive listening (as opposed to following an outline driven presentation that’s supplemented with visuals, i.e., slides).

Admittedly, I’ve read some papers before, and writing them to be read can be a rewarding process, too. I had to pay attention to details differently: structure, tone, story, etc. It can be an insightful process, especially for works in progress.

Sean, thanks for your comment, which I think is a really useful addition to the discussion. I’ve sat through so many turgid not-written-to-be-read presentations that it never occurred to me they could be done well until I heard your thoughts. What you say makes a great deal of sense to me, particularly with presentations that are consciously ‘written to be read’ out loud. I think where they can get tedious is where a paper written for the page is read out loud instead, because for me that really doesn’t work. But I love to listen to stories, and I think of some of the quality storytelling that is broadcast on radio, and of audiobooks that work well (again, in my experience, they don’t all), and I do entirely see your point.

Helen, I appreciate your encouraging me remark on such a minor part of your post(!), which I enjoyed reading and will share. And thank you for the reply and the exchange on Twitter.

Very much enjoyed your post Helen. And your subsequent comments Sean. On the subject of the reading of a presentation. I agree that some people can write a paper specifically to be read and this can be done well. But I would think that this is a dying art. Perhaps in the humanities it might survive longer. Reading through the rest of your post I love the advice. I’m presenting at my first LIS conference next month and had I read your post first I probably would have written it differently. Advice for the future for me.

Martin – and Sean – thank you so much for your kind comments. Maybe there are steps we can take to keep the art alive; advocates for it, such as Sean, will no doubt help. And, Martin, if you’re presenting next month, you must have done perfectly well all by yourself! Congratulations on the acceptance, and best of luck for the presentation.

Great article! Obvious at it may seem, a point zero may be added before the other four: which _are_ your ideas?

A scientific writing coach told me she often runs a little exercise with her students. She tells them to put away their (journal) abstract and then asks them to summarize the bottom line in three statements. After some thinking, the students come up with an answer. Then the coach tells the students to reach for the abstract, read it and look for the bottom line they just summarised. Very often, they find that their own main observations and/or conclusions are not clearly expressed in the abstract.

PS I love the line “It’s unethical to bore people!” 🙂

Thanks for your comment, Olle – that’s a great point. I think something happens to us when we’re writing, in which we become so clear about what we want to say that we think we’ve said it even when we haven’t. Your friend’s exercise sounds like a great trick for finding out when we’ve done that. And thanks for the compliments, too!

- Pingback: How to write a conference abstract | Blog @HEC Paris Library

- Pingback: Writer’s Paralysis | Helen Kara

- Pingback: Weekend reads: - Retraction Watch at Retraction Watch

- Pingback: The Weekly Roundup | The Graduate School

- Pingback: My Top 10 Abstract Writing tips | Jon Rainford's Blog

- Pingback: Review of the Year 2015 | Helen Kara

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – 2015 Year-In-Review: LSE Impact Blog’s Most Popular Posts

Thank you very much for the tips, they are really helpful. I have actually been accepted to present a PuchaKucha presentation in an educational interdisciplinary conference at my university. my presentation would be about the challenges faced by women in my country. So, it would be just a review of the literature. from what I’ve been reading, conferences are about new research and your new ideas… Is what I’m doing wrong??? that’s my first conference I’ll be speaking in and I’m afraid to ruin it!!! I will be really grateful about any advice ^_^

First of all: you’re not going to ruin the conference, even if you think you made a bad presentation. You should always remember that people are not very concerned about you–they are mostly concerned about themselves. Take comfort in that thought!

Here are some notes: • If it is a Pecha Kucha night, you stand in front of a mixed audience. Remember that scientists understand layman’s stuff, but laymen don’t understand scientists stuff. • Pecha Kucha is also very VISUAL! Remember that you can’t control the flow of slides – they change every 20 seconds. • Make your main messages clear. You can use either one of these templates.

A. Which are the THREE most important observations, conclusions, implications or messages from your study?

B. Inform them! (LOGOS) Engage them! (PATHOS) Make an impression! (ETHOS)

C. What do you do as a scientist/is a study about? What problem(s) do you address? How is your research different? Why should I care?

Good luck and remember to focus on (1) the audience, (2) your mission, (3) your stuff and (4) yourself, in that order.

- Pingback: How to choose a conference then write an abstract that gets you noticed | The Research Companion

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – Impact Community Insights: Five things we learned from our Reader Survey and Google Analytics.

- Pingback: Giving Us The Space To Think Things Through… | Research Into Practice Group

- Pingback: The Scholar-Practitioner Paradox for Academic Writing [@BreakDrink Episode No. 8] – techKNOWtools