Want to Get your Dissertation Accepted?

Discover how we've helped doctoral students complete their dissertations and advance their academic careers!

Join 200+ Graduated Students

Get Your Dissertation Accepted On Your Next Submission

Get customized coaching for:.

- Crafting your proposal,

- Collecting and analyzing your data, or

- Preparing your defense.

Trapped in dissertation revisions?

Dissertation proposal defense: 12 tips for effective preparation, published by steve tippins on may 11, 2020 may 11, 2020.

Last Updated on: 2nd February 2024, 02:59 am

The dissertation proposal defense is a nerve-wracking time for even the most hardened of doctoral students.

Even a pirate (writing his dissertation on effective cutlass techniques), will quake a bit in his boots before delivering his dissertation proposal defense.

However, it doesn’t need to be a stressful time.

As a longtime Dissertation Committee Chair and committee member, I’ve overseen more dissertation proposal defenses than I can count. I’ve also helped students through the process as a coach .

If you follow these tips for preparing and delivering your presentation, you shouldn’t have any problem passing your proposal defense.

Dissertation Proposal Defense Tips

Preparing for your Dissertation Proposal Defense

1. anticipate questions. .

In your presentation, try to answer all of the questions you expect your committee to ask. That way, you control the material. Your committee will be more satisfied with your preparation and understanding and it will be less likely that you have to answer questions that you aren’t prepared for.

2. Look for Weaknesses.

If there are potential weaknesses (in your study, proposal, or presentation), address them ahead of time. Ask peers or mentors to review your proposal or presentation for weaknesses. Look at it yourself with a critical eye. Even if you’re not able to eliminate a weakness, take steps to address it as best you can so that your committee can be confident that you’re aware of it and able to handle it.

3. Practice.

Ideally, you would practice with someone who has been a committee member before. They’ll point out the types of questions they would see your committee asking, so you can prepare for those. I can’t understate the value of having this kind of feedback beforehand so that you can properly prepare. I offer this service as part of my dissertation coaching package .

4. Avoid Wordiness on PowerPoint Slides .

Most dissertation proposal defenses have PowerPoints. Don’t put too many words on the slides! People will start reading the slides instead of paying attention to you. Then they’re off somewhere else which will produce questions that you’ve already answered when they weren’t paying attention.

5. Be Able to Pronounce the Words Correctly.

This might sound obvious, but as a dissertation committee member , I’ve heard far too many students struggle through pronunciations of important terminology. This is probably because, up until this point, they’ve only read them and not spoken them out loud.

However, it gives the committee the impression that they don’t know what they’re talking about. Make sure you can properly pronounce all the words you plan on using (like “phenomenological” and “anthropomorphism,”).

6. Watch Recordings of Previous Defenses.

Some schools have recordings of previous defenses. Listen to one or two. See how the procedure goes. Even if it’s not anything in your discipline, it will still help you get familiar with the procedure itself, which will help you be more comfortable when the time comes.

During your Dissertation Proposal Defense:

7. breathe . .

I’ve seen way too many people try to do their dissertation proposal defense seemingly in one breath. Give your committee time to hear and understand what you’re saying. Remember to leave some moments of silence to allow your audience to digest what you say. Also remember that one second of actual time feels like about thirty minutes to someone who’s giving an important presentation. Breathe.

8. Remember: They Want to Pass You.

If you’ve gotten to the point where your committee has scheduled a dissertation proposal defense for you, that means they believe that you can pass it. They want to pass you. Remember that.

They’re not out to screw you, they’re not out for “gotchas.” They’re saying, “we believe you’re ready, show us that’s true.” While they will be rigorous in their evaluation because they have a responsibility to make sure that they don’t allow you to move forward until you are ready to, it’s helpful to remember that they believe you can pass.

9. Answer the Question, No More.

When committee members ask questions, answer only the question–don’t give them anything more than that. Imagine that you’re a witness in a courtroom (or don’t if that makes you more nervous). Committee members value direct, relevant answers and often find tangents irrelevant and frustrating.

10. Dialogue With Your Committee.

If the committee disagrees with something you said, it can be a discussion. You don’t need to just roll over and say “Yes, you’re right. I made a mistake and I’m very bad.” That’s not what your committee wants to hear, either.

A much better response would be, “I hear what you’re saying, however, this is the reason I’m going in this other direction. What do you think about that?” So you’re beginning to engage in discussions as a scholar. Your committee will be impressed by your ability to think critically and your willingness to engage in dialogue.

However, do not make it adversarial. It’s incredibly important to be respectful in these conversations. After all, your committee members have significant control over your life for as long as you’re writing your dissertation.

11. Make Life Easy for Your Committee.

It’s always good to send your committee members a copy of your PowerPoint presentation and the most recent copy of your proposal the day before the defense. They likely already have a copy, but when in doubt, make their lives easier. It doesn’t cost you anything. Someone might accidentally have an old copy, or might take them some time to find the copy they have. You want their life to be as easy as possible so they can focus on moving you forward.

12. Pay Attention to Time.

Ask your Chair (in the preparation stage) how long you have to make your presentation. It’s extraordinarily important to stay within this timeframe. If you’re told 25 minutes but you take 50 minutes, committee members are predisposed to say “why isn’t this person better prepared, and why are they wasting my time?”

Likewise, if you run through a 30-minute presentation in ten minutes (nervousness can sometimes lead to very fast talking–that’s why it’s important to practice beforehand), your committee will be wondering why you didn’t use the whole time that was allotted to you. And you’ll likely have to field a lot of questions you weren’t prepared for.

Dissertation Proposal Defense Summary

As long as you prepare properly, your dissertation proposal defense should be nothing to worry about. Your committee thinks you’re ready: all you have to do is show them you’re right.

If you’d like help preparing for your defense, or if you’d like to reduce the amount of time it takes to finish your dissertation, take a look at my Dissertation Coaching Services .

Steve Tippins

Steve Tippins, PhD, has thrived in academia for over thirty years. He continues to love teaching in addition to coaching recent PhD graduates as well as students writing their dissertations. Learn more about his dissertation coaching and career coaching services. Book a Free Consultation with Steve Tippins

Related Posts

Dissertation

What makes a good research question.

Creating a good research question is vital to successfully completing your dissertation. Here are some tips that will help you formulate a good research question. What Makes a Good Research Question? These are the three Read more…

Dissertation Structure

When it comes to writing a dissertation, one of the most fraught questions asked by graduate students is about dissertation structure. A dissertation is the lengthiest writing project that many graduate students ever undertake, and Read more…

Choosing a Dissertation Chair

Choosing your dissertation chair is one of the most important decisions that you’ll make in graduate school. Your dissertation chair will in many ways shape your experience as you undergo the most rigorous intellectual challenge Read more…

Make This Your Last Round of Dissertation Revision.

Learn How to Get Your Dissertation Accepted .

Discover the 5-Step Process in this Free Webinar .

Almost there!

Please verify your email address by clicking the link in the email message we just sent to your address.

If you don't see the message within the next five minutes, be sure to check your spam folder :).

Hack Your Dissertation

5-Day Mini Course: How to Finish Faster With Less Stress

Interested in more helpful tips about improving your dissertation experience? Join our 5-day mini course by email!

- Newsletters

Defending Your Dissertation: A Guide

Written by Luke Wink-Moran | Photo by insta_photos

Dissertation defenses are daunting, and no wonder; it’s not a “dissertation discussion,” or a “dissertation dialogue.” The name alone implies that the dissertation you’ve spent the last x number of years working on is subject to attack. And if you don’t feel trepidation for semantic reasons, you might be nervous because you don’t know what to expect. Our imaginations are great at making The Unknown scarier than reality. The good news is that you’ll find in this newsletter article experts who can shed light on what dissertations defenses are really like, and what you can do to prepare for them.

The first thing you should know is that your defense has already begun. It started the minute you began working on your dissertation— maybe even in some of the classes you took beforehand that helped you formulate your ideas. This, according to Dr. Celeste Atkins, is why it’s so important to identify a good mentor early in graduate school.

“To me,” noted Dr. Atkins, who wrote her dissertation on how sociology faculty from traditionally marginalized backgrounds teach about privilege and inequality, “the most important part of the doctoral journey was finding an advisor who understood and supported what I wanted from my education and who was willing to challenge me and push me, while not delaying me. I would encourage future PhDs to really take the time to get to know the faculty before choosing an advisor and to make sure that the members of their committee work well together.”

Your advisor will be the one who helps you refine arguments and strengthen your work so that by the time it reaches your dissertation committee, it’s ready. Next comes the writing process, which many students have said was the hardest part of their PhD. I’ve included this section on the writing process because this is where you’ll create all the material you’ll present during your defense, so it’s important to navigate it successfully. The writing process is intellectually grueling, it eats time and energy, and it’s where many students find themselves paddling frantically to avoid languishing in the “All-But-Dissertation” doldrums. The writing process is also likely to encroach on other parts of your life. For instance, Dr. Cynthia Trejo wrote her dissertation on college preparation for Latin American students while caring for a twelve-year-old, two adult children, and her aging parents—in the middle of a pandemic. When I asked Dr. Trejo how she did this, she replied:

“I don’t take the privilege of education for granted. My son knew I got up at 4:00 a.m. every morning, even on weekends, even on holidays; and it’s a blessing that he’s seen that work ethic and that dedication and the end result.”

Importantly, Dr. Trejo also exercised regularly and joined several online writing groups at UArizona. She mobilized her support network— her partner, parents, and even friends from high school to help care for her son.

The challenges you face during the writing process can vary by discipline. Jessika Iwanski is an MD/PhD student who in 2022 defended her dissertation on genetic mutations in sarcomeric proteins that lead to severe, neonatal dilated cardiomyopathy. She described her writing experience as “an intricate process of balancing many things at once with a deadline (defense day) that seems to be creeping up faster and faster— finishing up experiments, drafting the dissertation, preparing your presentation, filling out all the necessary documents for your defense and also, for MD/PhD students, beginning to reintegrate into the clinical world (reviewing your clinical knowledge and skill sets)!”

But no matter what your unique challenges are, writing a dissertation can take a toll on your mental health. Almost every student I spoke with said they saw a therapist and found their sessions enormously helpful. They also looked to the people in their lives for support. Dr. Betsy Labiner, who wrote her dissertation on Interiority, Truth, and Violence in Early Modern Drama, recommended, “Keep your loved ones close! This is so hard – the dissertation lends itself to isolation, especially in the final stages. Plus, a huge number of your family and friends simply won’t understand what you’re going through. But they love you and want to help and are great for getting you out of your head and into a space where you can enjoy life even when you feel like your dissertation is a flaming heap of trash.”

While you might sometimes feel like your dissertation is a flaming heap of trash, remember: a) no it’s not, you brilliant scholar, and b) the best dissertations aren’t necessarily perfect dissertations. According to Dr. Trejo, “The best dissertation is a done dissertation.” So don’t get hung up on perfecting every detail of your work. Think of your dissertation as a long-form assignment that you need to finish in order to move onto the next stage of your career. Many students continue revising after graduation and submit their work for publication or other professional objectives.

When you do finish writing your dissertation, it’s time to schedule your defense and invite friends and family to the part of the exam that’s open to the public. When that moment comes, how do you prepare to present your work and field questions about it?

“I reread my dissertation in full in one sitting,” said Dr. Labiner. “During all my time writing it, I’d never read more than one complete chapter at a time! It was a huge confidence boost to read my work in full and realize that I had produced a compelling, engaging, original argument.”

There are many other ways to prepare: create presentation slides and practice presenting them to friends or alone; think of questions you might be asked and answer them; think about what you want to wear or where you might want to sit (if you’re presenting on Zoom) that might give you a confidence boost. Iwanksi practiced presenting with her mentor and reviewed current papers to anticipate what questions her committee might ask. If you want to really get in the zone, you can emulate Dr. Labiner and do a full dress rehearsal on Zoom the day before your defense.

But no matter what you do, you’ll still be nervous:

“I had a sense of the logistics, the timing, and so on, but I didn’t really have clear expectations outside of the structure. It was a sort of nebulous three hours in which I expected to be nauseatingly terrified,” recalled Dr. Labiner.

“I expected it to be terrifying, with lots of difficult questions and constructive criticism/comments given,” agreed Iwanski.

“I expected it to be very scary,” said Dr. Trejo.

“I expected it to be like I was on trial, and I’d have to defend myself and prove I deserved a PhD,” said Dr Atkins.

And, eventually, inexorably, it will be time to present.

“It was actually very enjoyable” said Iwanski. “It was more of a celebration of years of work put into this project—not only by me but by my mentor, colleagues, lab members and collaborators! I felt very supported by all my committee members and, rather than it being a rapid fire of questions, it was more of a scientific discussion amongst colleagues who are passionate about heart disease and muscle biology.”

“I was anxious right when I logged on to the Zoom call for it,” said Dr. Labiner, “but I was blown away by the number of family and friends that showed up to support me. I had invited a lot of people who I didn’t at all think would come, but every single person I invited was there! Having about 40 guests – many of them joining from different states and several from different countries! – made me feel so loved and celebrated that my nerves were steadied very quickly. It also helped me go into ‘teaching mode’ about my work, so it felt like getting to lead a seminar on my most favorite literature.”

“In reality, my dissertation defense was similar to presenting at an academic conference,” said Dr. Atkins. “I went over my research in a practiced and organized way, and I fielded questions from the audience.

“It was a celebration and an important benchmark for me,” said Dr. Trejo. “It was a pretty happy day. Like the punctuation at the end of your sentence: this sentence is done; this journey is done. You can start the next sentence.”

If you want to learn more about dissertations in your own discipline, don’t hesitate to reach out to graduates from your program and ask them about their experiences. If you’d like to avail yourself of some of the resources that helped students in this article while they wrote and defended their dissertations, check out these links:

The Graduate Writing Lab

https://thinktank.arizona.edu/writing-center/graduate-writing-lab

The Writing Skills Improvement Program

https://wsip.arizona.edu

Campus Health Counseling and Psych Services

https://caps.arizona.edu

https://www.scribbr.com/

Higher Ed Professor

Demystifying higher education.

- Productivity

- Issue Discussion

- Current Events

Defending your dissertation proposal

T he dissertation proposal and defense represent key milestones in the journey to the degree (Bowen, 2005). Each section of the proposal meets goals critical not just to a successful proposal defense but to the success of the entire dissertation research endeavor. When you and your faculty advisor agree that the dissertation proposal is complete, you will schedule a proposal defense. Ideally, your academic program will inform you in advance of the expected timeline. Within this timeline, you will then work with your advisor and committee members to determine a day and time for the defense. Institutional norms and policies likely require that the finished proposal be provided to the committee a specific number of days or weeks in advance of the defense. Typically, you should expect to provide at least two weeks lead time prior to the proposal defense (Butin, 2010). In today’s post, I will share some details on what to expect and how to prepare for defending your dissertation proposal.

The proposal defense serves two functions. First, the defense allows you to demonstrate your knowledge of the topic and the research process. Second, the defense ensures that you move forward with the dissertation in the strongest possible position. Your chair and committee should make sure you are prepared to complete the study, and that the study is feasible in terms of research design and timeline (Lei, 2009). In effect, a successful proposal defense (and the resulting faculty signatures of approval) constitutes an agreement between the student, the chair, and the committee. For the committee, the agreement codifies that you have done the proper due diligence and can produce a quality dissertation; for you, the approval provides the security of knowing that the committee supports the intended research design and direction.

After setting the defense date and providing a copy of the proposal to the committee, you should prepare for the defense. In most cases, you should not make edits or changes to the proposal after sending it to the committee, even if you notice typographical errors or other small issues. The committee takes care and time to read and prepare questions based on the document they receive; making changes after the document is sent defeats this purpose. While you should not change the document itself, you do need spend time preparing your oral remarks for the proposal defense. Of course, the expectations for this element of the dissertation process vary according to institution and/or dissertation chair preferences; nevertheless, all students can expect to engage in at least a short oral presentation of the proposed study. The committee will have read your proposal at this point, so prepare a talk that summarizes just the main ideas of your dissertation. Let’s say you are asked to present for no more than 15-30 minutes (this practice is a common one). You may want to divide this time into thirds and spend 5-10 minutes on each chapter of your proposal. Additionally, check with your chair to determine if technology is available in the room, if you are expected to use technology, or if handouts or other written materials are expected or preferred.

In addition to preparing for the proposal defense, you may also spend the time between the proposal submission and defense by preparing documents for eventual submission for human subjects research review. Often called the Institutional Review Board or IRB, this department on campus oversees human subject research. Approval from this university office, in addition to the dissertation committee, must be received before moving to data collection. These documents should not be submitted prior to the proposal defense, since changes to the research design commonly occur at the proposal defense and would need to be incorporated into the final human subjects review proposal submission.

You should enter a proposal defense with the expectation of edits. A student rarely if ever leaves a defense without edits. The amount and extent of edits may vary, but feedback that clarifies and strengthens the dissertation serves as the primary outcome of a proposal defense. Edits do not necessarily mean that the original dissertation design was weak; rather, you should think of the defense and feedback from the committee as a collaborative process resulting in an even stronger study (Lei, 2009). After you present an oral summary of the proposal at the defense, committee members often take turns asking questions, sometimes in round-robin style, but other times in conversation with you and each other. You may be asked why you made specific choices as opposed to alternative options in the research design or to explain the logic that led to a specific design feature. The conversation can last for over an hour depending on the topic and the committee members. When the defense reaches a stopping point, you may be asked to leave the room for the committee to deliberate about next steps.

While what happens inside the room once you leave may seem mysterious, it is actually straightforward. The committee primarily discusses what edits, and in what form, they will require you to complete. Once everyone is satisfied, you will be called back into the room and informed of next steps. Three possible outcomes exist from a proposal defense.

- Pass without edits. The committee approves your dissertation proposal with no additional changes requested. Note: This is quite rare.

- Pass with edits. The committee approves your dissertation proposal pending edits. The requested revisions may be small or major, but do not require you to re-defend your dissertation proposal.

- The committee does not approve you moving forward, which means major changes or even a complete overhaul of your entire proposal is necessary. Unless you have pushed for a defense without your chair’s approval or failed to do what was requested during the proposal writing process, this outcome should not happen.

When edits are required, they will be shared with you after the proposal defense or perhaps in a subsequent meeting with the chair, depending on your chair’s preferences. Your committee may have raised a number of potential revisions during the proposal defense, but not all of these will be required. Working with your chair, you will create a to-do list of all issues to be addressed in response to the critiques and suggestions of the committee. Timelines can vary, but two actions generally must be taken at this point: 1) The submission of your human subjects review materials and 2) edits to the proposal. While IRB documents are usually submitted before students turn back to the proposal to make the needed edits, the order of these actions may vary between institutions.

A useful way to tackle the committee’s edits is to take the notes from the proposal defense and place them in one column of a two-column table. In the other column, outline the specific edit you made in response to the committee’s suggestion—you should undertake this tracking process while making edits to the proposal. Make sure to include the edits as well as their respective page numbers in your proposal. This format helps keep you accountable to all the committee’s requested changes and facilitates a later review by the chair and/or committee. You can include the list of revisions when submitting the revised proposal to the chair and, if requested, the committee.

Some committee members may want to see the revised proposal, while others are comfortable delegating that responsibility to the dissertation chair. Confirm with the committee and chair about their preference for overseeing this process at the proposal defense. In addition, you should know if and when the committee members are willing to sign the institutional documents accompanying a successful proposal defense. Ask your advisor, program administrator, or other faculty which documents are necessary for the defense and if you need to bring those with you. These documents signify that you have officially advanced to doctoral candidacy, a key step of the doctoral process.

What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

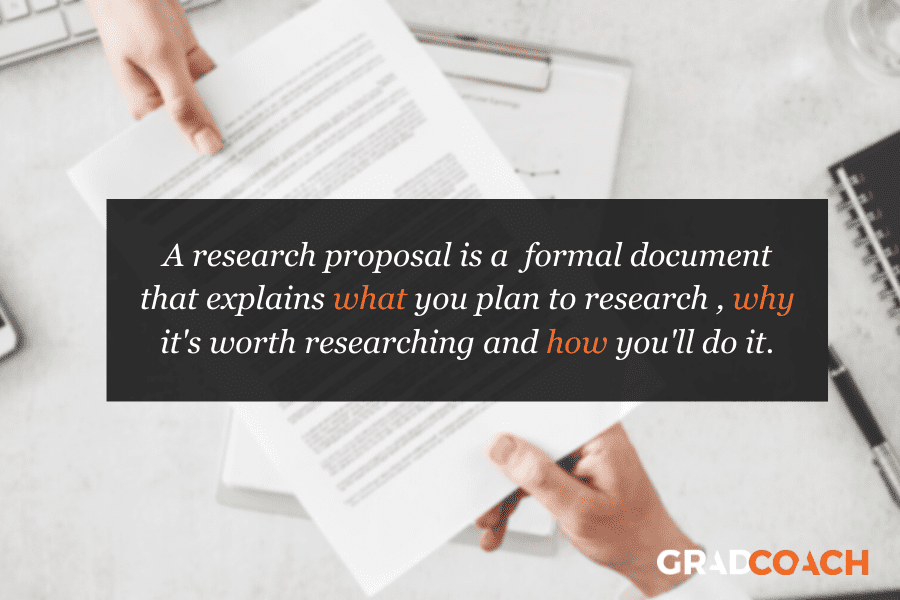

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?

While it’s generally not expected that you’ll have a fully fleshed-out methodology at the proposal stage, you’ll likely still need to provide a high-level overview of your research methodology . Here are some important questions you’ll need to address in your research proposal:

- Will you take a qualitative , quantitative or mixed -method approach?

- What sampling strategy will you adopt?

- How will you collect your data (e.g., interviews, surveys, etc)?

- How will you analyse your data (e.g., descriptive and inferential statistics , content analysis, discourse analysis, etc, .)?

- What potential limitations will your methodology carry?

So, be sure to give some thought to the practicalities of your research and have at least a basic methodological plan before you start writing up your proposal. If this all sounds rather intimidating, the video below provides a good introduction to research methodology and the key choices you’ll need to make.

How To Structure A Research Proposal

Now that we’ve covered the key points that need to be addressed in a proposal, you may be wondering, “ But how is a research proposal structured? “.

While the exact structure and format required for a research proposal differs from university to university, there are four “essential ingredients” that commonly make up the structure of a research proposal:

- A rich introduction and background to the proposed research

- An initial literature review covering the existing research

- An overview of the proposed research methodology

- A discussion regarding the practicalities (project plans, timelines, etc.)

In the video below, we unpack each of these four sections, step by step.

Research Proposal Examples/Samples

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of two successful research proposals (Master’s and PhD-level), as well as our popular free proposal template.

Proposal Writing FAQs

How long should a research proposal be.

This varies tremendously, depending on the university, the field of study (e.g., social sciences vs natural sciences), and the level of the degree (e.g. undergraduate, Masters or PhD) – so it’s always best to check with your university what their specific requirements are before you start planning your proposal.

As a rough guide, a formal research proposal at Masters-level often ranges between 2000-3000 words, while a PhD-level proposal can be far more detailed, ranging from 5000-8000 words. In some cases, a rough outline of the topic is all that’s needed, while in other cases, universities expect a very detailed proposal that essentially forms the first three chapters of the dissertation or thesis.

The takeaway – be sure to check with your institution before you start writing.

How do I choose a topic for my research proposal?

Finding a good research topic is a process that involves multiple steps. We cover the topic ideation process in this video post.

How do I write a literature review for my proposal?

While you typically won’t need a comprehensive literature review at the proposal stage, you still need to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the key literature and are able to synthesise it. We explain the literature review process here.

How do I create a timeline and budget for my proposal?

We explain how to craft a project plan/timeline and budget in Research Proposal Bootcamp .

Which referencing format should I use in my research proposal?

The expectations and requirements regarding formatting and referencing vary from institution to institution. Therefore, you’ll need to check this information with your university.

What common proposal writing mistakes do I need to look out for?

We’ve create a video post about some of the most common mistakes students make when writing a proposal – you can access that here . If you’re short on time, here’s a quick summary:

- The research topic is too broad (or just poorly articulated).

- The research aims, objectives and questions don’t align.

- The research topic is not well justified.

- The study has a weak theoretical foundation.

- The research design is not well articulated well enough.

- Poor writing and sloppy presentation.

- Poor project planning and risk management.

- Not following the university’s specific criteria.

Key Takeaways & Additional Resources

As you write up your research proposal, remember the all-important core purpose: to convince . Your research proposal needs to sell your study in terms of suitability and viability. So, focus on crafting a convincing narrative to ensure a strong proposal.

At the same time, pay close attention to your university’s requirements. While we’ve covered the essentials here, every institution has its own set of expectations and it’s essential that you follow these to maximise your chances of approval.

By the way, we’ve got plenty more resources to help you fast-track your research proposal. Here are some of our most popular resources to get you started:

- Proposal Writing 101 : A Introductory Webinar

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : The Ultimate Online Course

- Template : A basic template to help you craft your proposal

If you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your research proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the proposal development process (and the entire research journey), step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

I truly enjoyed this video, as it was eye-opening to what I have to do in the preparation of preparing a Research proposal.

I would be interested in getting some coaching.

I real appreciate on your elaboration on how to develop research proposal,the video explains each steps clearly.

Thank you for the video. It really assisted me and my niece. I am a PhD candidate and she is an undergraduate student. It is at times, very difficult to guide a family member but with this video, my job is done.

In view of the above, I welcome more coaching.

Wonderful guidelines, thanks

This is very helpful. Would love to continue even as I prepare for starting my masters next year.

Thanks for the work done, the text was helpful to me

Bundle of thanks to you for the research proposal guide it was really good and useful if it is possible please send me the sample of research proposal

You’re most welcome. We don’t have any research proposals that we can share (the students own the intellectual property), but you might find our research proposal template useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-proposal-template/

Cheruiyot Moses Kipyegon

Thanks alot. It was an eye opener that came timely enough before my imminent proposal defense. Thanks, again

thank you very much your lesson is very interested may God be with you

I am an undergraduate student (First Degree) preparing to write my project,this video and explanation had shed more light to me thanks for your efforts keep it up.

Very useful. I am grateful.

this is a very a good guidance on research proposal, for sure i have learnt something

Wonderful guidelines for writing a research proposal, I am a student of m.phil( education), this guideline is suitable for me. Thanks

You’re welcome 🙂

Thank you, this was so helpful.

A really great and insightful video. It opened my eyes as to how to write a research paper. I would like to receive more guidance for writing my research paper from your esteemed faculty.

Thank you, great insights

Thank you, great insights, thank you so much, feeling edified

Wow thank you, great insights, thanks a lot

Thank you. This is a great insight. I am a student preparing for a PhD program. I am requested to write my Research Proposal as part of what I am required to submit before my unconditional admission. I am grateful having listened to this video which will go a long way in helping me to actually choose a topic of interest and not just any topic as well as to narrow down the topic and be specific about it. I indeed need more of this especially as am trying to choose a topic suitable for a DBA am about embarking on. Thank you once more. The video is indeed helpful.

Have learnt a lot just at the right time. Thank you so much.

thank you very much ,because have learn a lot things concerning research proposal and be blessed u for your time that you providing to help us

Hi. For my MSc medical education research, please evaluate this topic for me: Training Needs Assessment of Faculty in Medical Training Institutions in Kericho and Bomet Counties

I have really learnt a lot based on research proposal and it’s formulation

Thank you. I learn much from the proposal since it is applied

Your effort is much appreciated – you have good articulation.

You have good articulation.

I do applaud your simplified method of explaining the subject matter, which indeed has broaden my understanding of the subject matter. Definitely this would enable me writing a sellable research proposal.

This really helping

Great! I liked your tutoring on how to find a research topic and how to write a research proposal. Precise and concise. Thank you very much. Will certainly share this with my students. Research made simple indeed.

Thank you very much. I an now assist my students effectively.

Thank you very much. I can now assist my students effectively.

I need any research proposal

Thank you for these videos. I will need chapter by chapter assistance in writing my MSc dissertation

Very helpfull

the videos are very good and straight forward

thanks so much for this wonderful presentations, i really enjoyed it to the fullest wish to learn more from you

Thank you very much. I learned a lot from your lecture.

I really enjoy the in-depth knowledge on research proposal you have given. me. You have indeed broaden my understanding and skills. Thank you

interesting session this has equipped me with knowledge as i head for exams in an hour’s time, am sure i get A++

This article was most informative and easy to understand. I now have a good idea of how to write my research proposal.

Thank you very much.

Wow, this literature is very resourceful and interesting to read. I enjoyed it and I intend reading it every now then.

Thank you for the clarity

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thank you very much for this essential piece. I need 1o1 coaching, unfortunately, your service is not available in my country. Anyways, a very important eye-opener. I really enjoyed it. A thumb up to Gradcoach

What is JAM? Please explain.

Thank you so much for these videos. They are extremely helpful! God bless!

very very wonderful…

thank you for the video but i need a written example

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How Should I Shape and Defend My Proposal?

- First Online: 28 June 2019

Cite this chapter

- Ray Cooksey 3 &

- Gael McDonald 4

1665 Accesses

This chapter discusses considerations surrounding the production of your research proposal. Your proposal will be required in the early stages of your candidature and is, essentially, a detailed plan of your anticipated postgraduate research journey in the context of the degree program you are enrolled in. In your proposal, you detail ‘ what ’ you intend to study in the form of the topic and research questions and ‘ why ’ (contextualisation and positioning, anticipated contribution(s), potential limitations), and ‘ how ’ (guiding assumptions, research frame, research configuration, sampling and data gathering and analysis strategies) you will obtain the answers to your questions. Your goal is to convince relevant stakeholders that your planned research has a high likelihood of achieving its goals, will add value as an original contribution, will demonstrate your capabilities as a competent researcher, and, most importantly, will likely lead to successful completion of the postgraduate program in which you are enrolled.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Cooksey, R. W. (2008). Paradigm-independent meta-criteria for social & behavioural research. Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Postgraduate Research Conference , University of New England, Armidale, NSW, pp. 4–17.

Google Scholar

Dadich, A., & Fitzgerald, A. (2006). Qualitative research in the making: A practical guide to project design . Paper presented at the ACSPRI Social Science Methodology Conference, Sydney, Australia.

Finn, J. A. (2005). Getting a PhD: An action plan to help manage your research, your supervisor and your project . London: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Hamper, R. J., & Baugh, L. (2010). Handbook for writing proposals (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Jay, R. (2000). How to write proposals and reports that get results: Master the skills of business writing (Rev. ed.). London: Prentice Hall.

Kilbourn, B. (2006). The qualitative doctoral dissertation proposal. Teachers College Record, 108 (4), 529–576.

Article Google Scholar

Krathwohl, D. R., & Smith, N. L. (2005). How to prepare a dissertation proposal . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Locke, L., Spirduso, W., & Silverman, S. (2014). Proposals that work: A guide for planning dissertations and grant proposals (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lockhart, J. C., & Stablein, R. E. (2002). Spanning the academy-practice divide with doctoral education in business. Higher Education Research & Development, 21 (2), 191–202.

O’Leary, Z. (2017). Doing your research project (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Panda, A., & Gupta, R. K. (2014). Making academic research more relevant: A few suggestions. IIMB Management Review, 26 (3), 156–169.

Peters, R. (1997). Getting what you came for: The smart student’s guide to earning a Master’s or a Ph.D. (Rev. ed.). New York: Noonday Press.

Polonsky, J. M., & Waller, S. D. (2015). Designing and managing a research project: A business student’s guide (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Punch, K. F. (2016). Developing effective research proposals (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Sternberg, R. (2014). Writing successful grant proposals from the top down and the bottom up . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Stewart, A. L., & Stewart, R. D. (1993). Proposal preparation (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Wiley.

Stokes, P., & Wall, T. (2014). Research methods . London: Palgrave.

Tammemagi, H. (2010). Winning proposals: How to write them and get better results (3rd ed.). North Vancouver, CA: Self-Counsel Press Inc.

Walker, R. (2014). Writing a research proposal . Retrieved October 27, 2018, from http://transnationalteachingteams.org/documents/Toolbox%207/Writing_A_Research_Proposal.pdf .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

UNE Business School, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia

Ray Cooksey

RMIT University Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Gael McDonald

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ray Cooksey .

Appendix: Research Proposal Check List

To recap, the intention of your research proposal is to cover a number of key questions, including:

What are the purpose and aims of the research?

What is your broad research problem?

What are your specific research questions/hypotheses?

What prior research is relevant to the area of study?

What areas of theory inform those research questions?

What is the underlying epistemology and guiding assumptions?

How are you positioning your research?

What is the theoretical or conceptual framework (where appropriate to have one)?

What data gathering strategies are you are going to use (and do you have a Plan B)?

How will you pilot test or trial your research approach?

How will you go about addressing each research question?

How will you approach the sampling of data sources, including how you will negotiate access via relevant gatekeepers (and do you have a Plan B)?

How will you address any ethical concerns and expectations?

What form of analysis and data displays are you considering?

What do you think are the intended outcomes?

What are the potential strengths and weaknesses of the data sources and what does this mean for your research plan?

What might be the benefit or value of this research and for whom?

What do you anticipate might be the limitations of the research plan?

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cooksey, R., McDonald, G. (2019). How Should I Shape and Defend My Proposal?. In: Surviving and Thriving in Postgraduate Research. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7747-1_16

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7747-1_16

Published : 28 June 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-13-7746-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-13-7747-1

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

- Editing Services

- Academic Editing Services

- Admissions Editing Services

- Admissions Essay Editing Services

- AI Content Editing Services

- APA Style Editing Services

- Application Essay Editing Services

- Book Editing Services

- Business Editing Services

- Capstone Paper Editing Services

- Children's Book Editing Services

- College Application Editing Services

- College Essay Editing Services

- Copy Editing Services

- Developmental Editing Services

- Dissertation Editing Services

- eBook Editing Services

- English Editing Services

- Horror Story Editing Services

- Legal Editing Services

- Line Editing Services

- Manuscript Editing Services

- MLA Style Editing Services

- Novel Editing Services

- Paper Editing Services

- Personal Statement Editing Services

- Research Paper Editing Services

- Résumé Editing Services

- Scientific Editing Services

- Short Story Editing Services

- Statement of Purpose Editing Services

- Substantive Editing Services

- Thesis Editing Services

Proofreading

- Proofreading Services

- Admissions Essay Proofreading Services

- Children's Book Proofreading Services

- Legal Proofreading Services

- Novel Proofreading Services

- Personal Statement Proofreading Services

- Research Proposal Proofreading Services

- Statement of Purpose Proofreading Services

Translation

- Translation Services

Graphic Design

- Graphic Design Services

- Dungeons & Dragons Design Services

- Sticker Design Services

- Writing Services

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

17 Thesis Defense Questions and How to Answer Them

A thesis defense gives you the chance to show off your thesis work and demonstrate your expertise in your field of study. During this one- to two-hour discussion with the members of your thesis committee, you'll have some control over how you present your research, but your committee will ask you some prodding questions to test your knowledge and preparedness. They will all have read your thesis beforehand, so their questions will relate to your study, topic, methods, data sample, and other aspects.

A good defense requires mastery of the thesis itself, so before you consider the questions you might face,

1. What is your topic, and why did you choose it?

Give a quick summary in just a few sentences on what you've researched. You could certainly go on for hours about your work, but make sure you prepare a way to give a very brief overview of your thesis. Then, give a quick background on your process for choosing this topic.

2. How does your topic contribute to the existing literature? How is it important?

Many researchers identify a need in the field and choose a topic to bridge the gaps that previous literature has failed to cover. For example, previous studies might not have included a certain population, region, or circumstance. Talk about how your thesis enhances the general understanding of the topic to extend the reach beyond what others have found, and then give examples of why the world needs that increased understanding. For instance, a thesis on romaine lettuce crops in desert climates might bring much-needed knowledge to a region that might not have been represented in previous work.

3. What are the key findings of your study?

When reporting your main results, make sure you have a handle on how detailed your committee wants you to be. Give yourself several options by preparing 1) a very general, quick summary of your findings that takes a minute or less, 2) a more detailed rundown of what your study revealed that is 3-5 minutes long, and 3) a 10- to 15-minute synopsis that delves into your results in detail. With each of these responses prepared, you can gauge which one is most appropriate in the moment, based on what your committee asks you and what has already been requested.

4. What type of background research did you do for your study?

Here you'll describe what you did while you were deciding what to study. This usually includes a literary review to determine what previous researchers have already introduced to the field. You also likely had to look into whether your study was going to be possible and what you would need in order to collect the needed data. Did you need info from databases that require permissions or fees?

5. What was your hypothesis, and how did you form it?

Describe the expected results you had for your study and whether your hypothesis came from previous research experience, long-held expectations, or cultural myths.

6. What limitations did you face when writing your text?

It's inevitable — researchers will face roadblocks or limiting factors during their work. This could be a limited population you had access to, like if you had a great method of surveying university students, but you didn't have a way to reach out to other people who weren't attending that school.

7. Why did you choose your particular method for your study?

Different research methods are more fitting to specific studies than others (e.g., qualitative vs. quantitative ), and knowing this, you applied a method that would present your findings most effectively. What factors led you to choose your method?

8. Who formed the sample group of your study, and why did you choose this population?

Many factors go into the selection of a participant group. Perhaps you were motivated to survey women over 50 who experience burnout in the workplace. Did you take extra measures to target this population? Or perhaps you found a sample group that responded more readily to your request for participation, and after hitting dead ends for months, convenience is what shaped your study population. Make sure to present your reasoning in an honest but favorable way.

9. What obstacles or limitations did you encounter while working with your sample?

Outline the process of pursuing respondents for your study and the difficulties you faced in collecting enough quality data for your thesis. Perhaps the decisions you made took shape based on the participants you ended up interviewing.

10. Was there something specific you were expecting to find during your analysis?

Expectations are natural when you set out to explore a topic, especially one you've been dancing around throughout your academic career. This question can refer to your hypotheses , but it can also touch on your personal feelings and expectations about this topic. What did you believe you would find when you dove deeper into the subject? Was that what you actually found, or were you surprised by your results?

11. What did you learn from your study?

Your response to this question can include not only the basic findings of your work (if you haven't covered this already) but also some personal surprises you might have found that veered away from your expectations. Sometimes these details are not included in the thesis, so these details can add some spice to your defense.

12. What are the recommendations from your study?

With connection to the reasons you chose the topic, your results can address the problems your work is solving. Give specifics on how policymakers, professionals in the field, etc., can improve their service with the knowledge your thesis provides.

13. If given the chance, what would you do differently?

Your response to this one can include the limitations you encountered or dead ends you hit that wasted time and funding. Try not to dwell too long on the annoyances of your study, and consider an area of curiosity; for example, discuss an area that piqued your interest during your exploration that would have been exciting to pursue but didn't directly benefit your outlined study.

14. How did you relate your study to the existing theories in the literature?

Your paper likely ties your ideas into those of other researchers, so this could be an easy one to answer. Point out how similar your work is to some and how it contrasts other works of research; both contribute greatly to the overall body of research.

15. What is the future scope of this study?

This one is pretty easy, since most theses include recommendations for future research within the text. That means you already have this one covered, and since you read over your thesis before your defense, it's already fresh in your mind.

16. What do you plan to do professionally after you complete your study?

This is a question directed more to you and your future professional plans. This might align with the research you performed, and if so, you can direct your question back to your research, maybe mentioning the personal motivations you have for pursuing study of that subject.

17. Do you have any questions?

Although your thesis defense feels like an interrogation, and you're the one in the spotlight, it provides an ideal opportunity to gather input from your committee, if you want it. Possible questions you could ask are: What were your impressions when reading my thesis? Do you believe I missed any important steps or details when conducting my work? Where do you see this work going in the future?

Bonus tip: What if you get asked a question to which you don't know the answer? You can spend weeks preparing to defend your thesis, but you might still be caught off guard when you don't know exactly what's coming. You can be ready for this situation by preparing a general strategy. It's okay to admit that your thesis doesn't offer the answers to everything – your committee won't reasonably expect it to do so. What you can do to sound (and feel!) confident and knowledgeable is to refer to a work of literature you have encountered in your research and draw on that work to give an answer. For example, you could respond, "My thesis doesn't directly address your question, but my study of Dr. Leifsen's work provided some interesting insights on that subject…." By preparing a way to address curveball questions, you can maintain your cool and create the impression that you truly are an expert in your field.

After you're done answering the questions your committee presents to you, they will either approve your thesis or suggest changes you should make to your paper. Regardless of the outcome, your confidence in addressing the questions presented to you will communicate to your thesis committee members that you know your stuff. Preparation can ease a lot of anxiety surrounding this event, so use these possible questions to make sure you can present your thesis feeling relaxed, prepared, and confident.

Header image by Kasto .

Related Posts

The Future of Academic Publishing: Emerging Trends You Should Know

How to Prove a Thesis Statement: Analyzing an Argument

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Take your thesis to new heights with our expert editing

University of Washington Information School

Doctorate in information science.

- Advising & Support

- Capstone Projects

- Upcoming Info Sessions

- Videos: Alumni at Work

- Request more information

Proposal Defense

The purpose of the dissertation proposal defense is to assure that your plan of researching your proposed research question is complete and holds academic merit. Students work closely with their supervisory committees in determining the composition of the dissertation proposal and in writing the proposal.

At least six weeks prior to the dissertation proposal defense, the candidate contacts Student Services to confirm the members of their supervisory committee. This would include the addition of a non-University of Washington external faculty member if previously agreed upon.

The candidate schedules a date, a time, and a room for the dissertation proposal defense. The candidate also submits details regarding the dissertation proposal defense to the iSchool web calendar, the PhD program chair, and Student Services.

At least two weeks before the scheduled proposal defense date, the final written proposal must be submitted to all members of the supervisory committee. The voting members of the committee, in consultation with the student, determine the length and outline the structure of the defense.

The proposal defense is a public event. However, the deliberations of the supervisory committee are private. The supervisory committee records an official decision using the dissertation proposal defense form.

Once the proposal has been defended and accepted, the candidate is cleared to finish writing the dissertation. The candidate submits one paper copy and one PDF version of the dissertation proposal to Student Services.

More Information

- Dissertation Proposal Defense Policy

- Dissertation Proposal Defense Form

- Learn more about supervisory committee policies

Full Results

Customize your experience.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to prepare an excellent thesis defense

What is a thesis defense?

How long is a thesis defense, what happens at a thesis defense, your presentation, questions from the committee, 6 tips to help you prepare for your thesis defense, 1. anticipate questions and prepare for them, 2. dress for success, 3. ask for help, as needed, 4. have a backup plan, 5. prepare for the possibility that you might not know an answer, 6. de-stress before, during, and after, frequently asked questions about preparing an excellent thesis defense, related articles.

If you're about to complete, or have ever completed a graduate degree, you have most likely come across the term "thesis defense." In many countries, to finish a graduate degree, you have to write a thesis .

A thesis is a large paper, or multi-chapter work, based on a topic relating to your field of study.

Once you hand in your thesis, you will be assigned a date to defend your work. Your thesis defense meeting usually consists of you and a committee of two or more professors working in your program. It may also include other people, like professionals from other colleges or those who are working in your field.

During your thesis defense, you will be asked questions about your work. The main purpose of your thesis defense is for the committee to make sure that you actually understand your field and focus area.

The questions are usually open-ended and require the student to think critically about their work. By the time of your thesis defense, your paper has already been evaluated. The questions asked are not designed so that you actually have to aggressively "defend" your work; often, your thesis defense is more of a formality required so that you can get your degree.

- Check with your department about requirements and timing.

- Re-read your thesis.

- Anticipate questions and prepare for them.

- Create a back-up plan to deal with technology hiccups.

- Plan de-stressing activities both before, and after, your defense.

How long your oral thesis defense is depends largely on the institution and requirements of your degree. It is best to consult your department or institution about this. In general, a thesis defense may take only 20 minutes, but it may also take two hours or more. The length also depends on how much time is allocated to the presentation and questioning part.

Tip: Check with your department or institution as soon as possible to determine the approved length for a thesis defense.

First of all, be aware that a thesis defense varies from country to country. This is just a general overview, but a thesis defense can take many different formats. Some are closed, others are public defenses. Some take place with two committee members, some with more examiners.

The same goes for the length of your thesis defense, as mentioned above. The most important first step for you is to clarify with your department what the structure of your thesis defense will look like. In general, your thesis defense will include:

- your presentation of around 20-30 minutes

- questions from the committee

- questions from the audience (if the defense is public and the department allows it)

You might have to give a presentation, often with Powerpoint, Google slides, or Keynote slides. Make sure to prepare an appropriate amount of slides. A general rule is to use about 10 slides for a 20-minute presentation.

But that also depends on your specific topic and the way you present. The good news is that there will be plenty of time ahead of your thesis defense to prepare your slides and practice your presentation alone and in front of friends or family.

Tip: Practice delivering your thesis presentation in front of family, friends, or colleagues.

You can prepare your slides by using information from your thesis' first chapter (the overview of your thesis) as a framework or outline. Substantive information in your thesis should correspond with your slides.

Make sure your slides are of good quality— both in terms of the integrity of the information and the appearance. If you need more help with how to prepare your presentation slides, both the ASQ Higher Education Brief and James Hayton have good guidelines on the topic.

The committee will ask questions about your work after you finish your presentation. The questions will most likely be about the core content of your thesis, such as what you learned from the study you conducted. They may also ask you to summarize certain findings and to discuss how your work will contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

Tip: Read your entire thesis in preparation of the questions, so you have a refreshed perspective on your work.

While you are preparing, you can create a list of possible questions and try to answer them. You can foresee many of the questions you will get by simply spending some time rereading your thesis.

Here are a few tips on how to prepare for your thesis defense:

You can absolutely prepare for most of the questions you will be asked. Read through your thesis and while you're reading it, create a list of possible questions. In addition, since you will know who will be on the committee, look at the academic expertise of the committee members. In what areas would they most likely be focused?

If possible, sit at other thesis defenses with these committee members to get a feel for how they ask and what they ask. As a graduate student, you should generally be adept at anticipating test questions, so use this advantage to gather as much information as possible before your thesis defense meeting.

Your thesis defense is a formal event, often the entire department or university is invited to participate. It signals a critical rite of passage for graduate students and faculty who have supported them throughout a long and challenging process.

While most universities don't have specific rules on how to dress for that event, do regard it with dignity and respect. This one might be a no-brainer, but know that you should dress as if you were on a job interview or delivering a paper at a conference.

It might help you deal with your stress before your thesis defense to entrust someone with the smaller but important responsibilities of your defense well ahead of schedule. This trusted person could be responsible for:

- preparing the room of the day of defense

- setting up equipment for the presentation

- preparing and distributing handouts

Technology is unpredictable. Life is too. There are no guarantees that your Powerpoint presentation will work at all or look the way it is supposed to on the big screen. We've all been there. Make sure to have a plan B for these situations. Handouts can help when technology fails, and an additional clean shirt can save the day if you have a spill.

One of the scariest aspects of the defense is the possibility of being asked a question you can't answer. While you can prepare for some questions, you can never know exactly what the committee will ask.

There will always be gaps in your knowledge. But your thesis defense is not about being perfect and knowing everything, it's about how you deal with challenging situations. You are not expected to know everything.

James Hayton writes on his blog that examiners will sometimes even ask questions they don't know the answer to, out of curiosity, or because they want to see how you think. While it is ok sometimes to just say "I don't know", he advises to try something like "I don't know, but I would think [...] because of x and y, but you would need to do [...] in order to find out.” This shows that you have the ability to think as an academic.

You will be nervous. But your examiners will expect you to be nervous. Being well prepared can help minimize your stress, but do know that your examiners have seen this many times before and are willing to help, by repeating questions, for example. Dora Farkas at finishyourthesis.com notes that it’s a myth that thesis committees are out to get you.

Two common symptoms of being nervous are talking really fast and nervous laughs. Try to slow yourself down and take a deep breath. Remember what feels like hours to you are just a few seconds in real life.

- Try meditational breathing right before your defense.

- Get plenty of exercise and sleep in the weeks prior to your defense.

- Have your clothes or other items you need ready to go the night before.

- During your defense, allow yourself to process each question before answering.

- Go to dinner with friends and family, or to a fun activity like mini-golf, after your defense.

Allow yourself to process each question, respond to it, and stop talking once you have responded. While a smile can often help dissolve a difficult situation, remember that nervous laughs can be irritating for your audience.

We all make mistakes and your thesis defense will not be perfect. However, careful preparation, mindfulness, and confidence can help you feel less stressful both before, and during, your defense.

Finally, consider planning something fun that you can look forward to after your defense.

It is completely normal to be nervous. Being well prepared can help minimize your stress, but do know that your examiners have seen this many times before and are willing to help, by repeating questions for example if needed. Slow yourself down, and take a deep breath.

Your thesis defense is not about being perfect and knowing everything, it's about how you deal with challenging situations. James Hayton writes on his blog that it is ok sometimes to just say "I don't know", but he advises to try something like "I don't know, but I would think [...] because of x and y, you would need to do [...] in order to find out".

Your Powerpoint presentation can get stuck or not look the way it is supposed to do on the big screen. It can happen and your supervisors know it. In general, handouts can always save the day when technology fails.

- Dress for success.

- Ask for help setting up.

- Have a backup plan (in case technology fails you).

- Deal with your nerves.

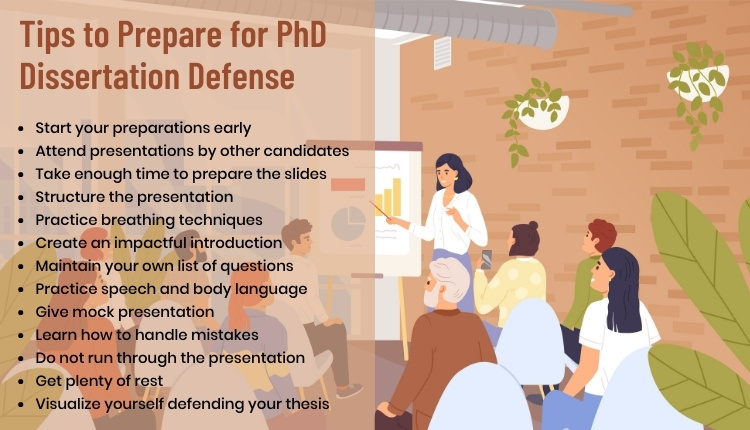

13 Tips to Prepare for Your PhD Dissertation Defense

How well do you know your project? Years of experiments, analysis of results, and tons of literature study, leads you to how well you know your research study. And, PhD dissertation defense is a finale to your PhD years. Often, researchers question how to excel at their thesis defense and spend countless hours on it. Days, weeks, months, and probably years of practice to complete your doctorate, needs to surpass the dissertation defense hurdle.

In this article, we will discuss details of how to excel at PhD dissertation defense and list down some interesting tips to prepare for your thesis defense.

Table of Contents

What Is Dissertation Defense?

Dissertation defense or Thesis defense is an opportunity to defend your research study amidst the academic professionals who will evaluate of your academic work. While a thesis defense can sometimes be like a cross-examination session, but in reality you need not fear the thesis defense process and be well prepared.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/c/JamesHaytonPhDacademy

What are the expectations of committee members.

Choosing the dissertation committee is one of the most important decision for a research student. However, putting your dissertation committee becomes easier once you understand the expectations of committee members.

The basic function of your dissertation committee is to guide you through the process of proposing, writing, and revising your dissertation. Moreover, the committee members serve as mentors, giving constructive feedback on your writing and research, also guiding your revision efforts.

The dissertation committee is usually formed once the academic coursework is completed. Furthermore, by the time you begin your dissertation research, you get acquainted to the faculty members who will serve on your dissertation committee. Ultimately, who serves on your dissertation committee depends upon you.

Some universities allow an outside expert (a former professor or academic mentor) to serve on your committee. It is advisable to choose a faculty member who knows you and your research work.

How to Choose a Dissertation Committee Member?

- Avoid popular and eminent faculty member

- Choose the one you know very well and can approach whenever you need them

- A faculty member whom you can learn from is apt.

- Members of the committee can be your future mentors, co-authors, and research collaborators. Choose them keeping your future in mind.

How to Prepare for Dissertation Defense?

1. Start Your Preparations Early

Thesis defense is not a 3 or 6 months’ exercise. Don’t wait until you have completed all your research objectives. Start your preparation well in advance, and make sure you know all the intricacies of your thesis and reasons to all the research experiments you conducted.

2. Attend Presentations by Other Candidates

Look out for open dissertation presentations at your university. In fact, you can attend open dissertation presentations at other universities too. Firstly, this will help you realize how thesis defense is not a scary process. Secondly, you will get the tricks and hacks on how other researchers are defending their thesis. Finally, you will understand why dissertation defense is necessary for the university, as well as the scientific community.

3. Take Enough Time to Prepare the Slides

Dissertation defense process harder than submitting your thesis well before the deadline. Ideally, you could start preparing the slides after finalizing your thesis. Spend more time in preparing the slides. Make sure you got the right data on the slides and rephrase your inferences, to create a logical flow to your presentation.

4. Structure the Presentation

Do not be haphazard in designing your presentation. Take time to create a good structured presentation. Furthermore, create high-quality slides which impresses the committee members. Make slides that hold your audience’s attention. Keep the presentation thorough and accurate, and use smart art to create better slides.

5. Practice Breathing Techniques

Watch a few TED talk videos and you will notice that speakers and orators are very fluent at their speech. In fact, you will not notice them taking a breath or falling short of breath. The only reason behind such effortless oratory skill is practice — practice in breathing technique.

Moreover, every speaker knows how to control their breath. Long and steady breaths are crucial. Pay attention to your breathing and slow it down. All you need I some practice prior to this moment.

6. Create an Impactful Introduction