Guide to the classics: Don Quixote, the world’s first modern novel – and one of the best

PhD Candidate and Teaching Associate, The University of Melbourne

Honorary Fellow, The University of Melbourne

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Melbourne provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember…

This line, arguably the most famous in the history of Spanish literature, is the opening of The Ingenious Nobleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes, the first modern novel .

Published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, this is the story of Alonso Quijano, a 16th-century Spanish hidalgo , a noble, who is so passionate about reading that he leaves home in search of his own chivalrous adventures. He becomes a knight-errant himself: Don Quixote de la Mancha. By imitating his admired literary heroes, he finds new meaning in his life: aiding damsels in distress, battling giants and righting wrongs… mostly in his own head.

But Don Quixote is much more. It is a book about books, reading, writing, idealism vs. materialism, life … and death. Don Quixote is mad. “His brain’s dried up” due to his reading, and he is unable to separate reality from fiction, a trait that was appreciated at the time as funny . However, Cervantes was also using Don Quixote’s insanity to probe the eternal debate between free will and fate. The misguided hero is actually a man fighting against his own limitations to become who he dreams to be.

Open-minded, well-travelled, and very well-educated, Cervantes was, like Don Quixote himself, an avid reader. He also served the Spanish crown in adventures that he would later include in the novel. After defeating the Ottoman Empire in the battle of Lepanto (and losing the use of his left hand, becoming “the one-handed of Lepanto”), Cervantes was captured and held for ransom in Algiers.

This autobiographical episode and his escape attempts are depicted in “The Captive’s Tale” (in Don Quixote Part I), where the character recalls “a Spanish soldier named something de Saavedra”, referring to Cervantes’s second last name. Years later, back in Spain, he completed Don Quixote in prison, due to irregularities in his accounts while he worked for the government.

Tilting at windmills

In Part I, Quijano with his new name, Don Quixote, gathers other indispensable accessories to any knight-errant: his armour; a horse, Rocinante; and a lady, an unwitting peasant girl he calls Dulcinea of Toboso, in whose name he will perform great deeds of chivalry.

While Don Quixote recovers from a disastrous first campaign as a knight, his close friends, the priest and the barber, decide to examine the books in his library. Their comments about his chivalric books combine literary criticism with a parody of the Inquisition ’s practices of burning texts associated with the devil. Although a few volumes are saved (Cervantes’s own La Galatea among them), most books are burned for their responsibility in Don Quixote’s madness.

In Don Quixote’s second expedition, the peasant Sancho Panza joins him as his faithful squire, with the hopes of becoming the governor of his own island one day. The duo diverges in every aspect. Don Quixote is tall and thin, Sancho is short and fat ( panza means “pot belly”). Sancho is an illiterate commoner and responds to Don Quixote’s elaborate speeches with popular proverbs. The mismatched couple has remained as a key literary archetype since then.

In perhaps the most famous scene from the novel, Don Quixote sees three windmills as fearful giants that he must combat, which is where the phrase “tilting at windmills” comes from. At the end of Part I, Don Quixote and Sancho are tricked into returning to their village. Sancho has become “quixotized”, now increasingly obsessed with becoming rich by ruling his own island.

Don Quixote was an enormous success, being translated from Spanish into the main European languages and even reaching North America. In 1614 an unknown author, Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda, published an apocryphal second part. Cervantes incorporated this spurious Don Quixote and its characters into his own Part II, adding yet another chapter to the history of modern narrative.

Whereas Part I was a reaction to chivalric romances, Part II is a reaction to Part I. The book is set only one month after Don Quixote and Sancho’s return from their first literary quest, after they are notified that a book retelling their story has been published (Part I).

The rest of Part II operates as a game of mirrors, recalling and rewriting episodes. New characters, such as aristocrats who have also read Part I, use their knowledge to play tricks on Don Quixote and Sancho for their own amusement. Deceived by the rest of the characters, Sancho and a badly wounded Don Quixote finally return again to their village.

After being in bed for several days, Don Quixote’s final hour arrives. He decides to abandon his existence as Don Quixote for good, giving up his literary identity and physically dying. He leaves Sancho – his best and most faithful reader – in tears, and avoids further additions by any future imitators by dying.

The original unreliable narrator

The narrator of Part I’s prologue claims to write a sincere and uncomplicated story. Nothing is further from reality. Distancing himself from textual authority, the narrator declares that he merely compiled a manuscript translated by some Arab historian – an untrustworthy source at the time. The reader has to decide what’s real and what’s not.

Don Quixote is also a book made of preexisting books. Don Quixote is obsessed with chivalric romances, and includes episodes parodying other narrative subgenres such as pastoral romances , picaresque novels and Italian novellas (of which Cervantes himself wrote a few ).

Don Quixote’s transformation from nobleman to knight-errant is particularly profound given the events in Europe at the time the novel was published. Spain had been reconquered by Christian royals after centuries of Islamic presence. Social status, ethnicity and religion were seen as determining a person’s future, but Don Quixote defied this. “I know who I am,” he answered roundly to whoever tried to convince him of his “true” and original identity.

Don Quixote through the ages

Many writers have been inspired by Don Quixote: from Goethe, Stendhal, Melville , Flaubert and Dickens, to Borges , Faulkner and Nabokov.

In fact, for many critics, the whole history of the novel could justifiably be considered “ a variation of the theme of Don Quixote ”. Since its early success, there have also been many valuable English translations of the novel. John Rutherford and more recently Edith Grossman have been praised for their versions .

Apart from literature, Don Quixote has inspired many creative works . Based on the episode of the wedding of Camacho in Part II, Marius Petipa choreographed a ballet in 1896. Also created for the stage, Man of La Mancha , the 1960s’ Broadway musical, is one of the most popular reimaginings. In 1992, the State Spanish TV launched a highly successful adaptation of Part I . Terry Gilliam’s much-awaited The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is only the most recent addition to a long list of films inspired by Don Quixote .

More than 400 years after its publication and great success, Don Quixote is widely considered the world’s best book by other celebrated authors. In our own times, full of windmills and giants, Don Quixote’s still-valuable message is that the way we filter reality through any ideology affects our perception of the world.

The headline of this article was updated on August 10 to clarify that Don Quixote is considered the first “modern” novel, not the first novel.

- Guide to the Classics

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

Or browse by category:

- Get the app

- Movie Reviews

- Best Movie Lists

- Best Movies on Netflix, Disney+, and More

Common Sense Selections for Movies

50 Modern Movies All Kids Should Watch Before They're 12

- Best TV Lists

- Best TV Shows on Netflix, Disney+, and More

- Common Sense Selections for TV

- Video Reviews of TV Shows

Best Kids' Shows on Disney+

Best Kids' TV Shows on Netflix

- Book Reviews

- Best Book Lists

- Common Sense Selections for Books

8 Tips for Getting Kids Hooked on Books

50 Books All Kids Should Read Before They're 12

- Game Reviews

- Best Game Lists

Common Sense Selections for Games

- Video Reviews of Games

Nintendo Switch Games for Family Fun

- Podcast Reviews

- Best Podcast Lists

Common Sense Selections for Podcasts

Parents' Guide to Podcasts

- App Reviews

- Best App Lists

Social Networking for Teens

Gun-Free Action Game Apps

Reviews for AI Apps and Tools

- YouTube Channel Reviews

- YouTube Kids Channels by Topic

Parents' Ultimate Guide to YouTube Kids

YouTube Kids Channels for Gamers

- Preschoolers (2-4)

- Little Kids (5-7)

- Big Kids (8-9)

- Pre-Teens (10-12)

- Teens (13+)

- Screen Time

- Social Media

- Online Safety

- Identity and Community

Explaining the News to Our Kids

- Family Tech Planners

- Digital Skills

- All Articles

- Latino Culture

- Black Voices

- Asian Stories

- Native Narratives

- LGBTQ+ Pride

- Best of Diverse Representation List

Celebrating Black History Month

Movies and TV Shows with Arab Leads

Celebrate Hip-Hop's 50th Anniversary

Don quixote, common sense media reviewers.

Art and emotion both lost in retelling of classic.

A Lot or a Little?

What you will—and won't—find in this book.

People taunt and torment Don Quixote because he is

A surprising amount of violence for a book filled

Some mild swearing: "scumbag," "dam

A reference to an ice cream brand.

Parents need to know that there is a surprisingly high level of violence for a book that looks like it's for middle graders. Most of it is played for laughs, but it involves severe beatings with serious and lasting injuries.

Positive Messages

People taunt and torment Don Quixote because he is mad.

Violence & Scariness

A surprising amount of violence for a book filled with pictures. Most of it is played humorously, but involves severe beatings, blood, knocked-out teeth, broken limbs, stabbings, split heads, and other serious injuries. A mention of a heart being cut out of a dying man, and of men hanged from trees.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Violence & Scariness in your kid's entertainment guide.

Some mild swearing: "scumbag," "damn," "ass," etc.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Language in your kid's entertainment guide.

Products & Purchases

Drinking, drugs & smoking.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Drinking, Drugs & Smoking in your kid's entertainment guide.

Parents Need to Know

Where to read, community reviews.

- Parents say

- Kids say (3)

There aren't any parent reviews yet. Be the first to review this title.

What's the Story?

An old Spanish man in the 1500s becomes obsessed with books on chivalry, loses his mind, and decides he is a knight errant. Convincing a peasant neighbor to accompany him as his squire, he travels around the countryside, wearing an old suit of armor and riding a nag, attempting feats of knighthood that are mostly in his imagination. While doing so, some of those he meets, hearing about his insanity, play a variety of tricks on him, some amusing and some cruel.

Is It Any Good?

This is a peculiar, if well-intentioned, effort. Illustrated retellings for children of classic adult literature is a large and controversial genre: some think that they take away the pleasure of discovering the real thing later in life, while others believe that it enriches their childhoods. But whichever side you fall on, this one is indeed a very strange concept for a children's book. Start with a story in which the main characters are a deranged old man and his middle-aged sidekick, neither likely to appeal to children. Take nearly 350 pages of often very formal prose, with a few weird anachronisms thrown in, to retell it, and do so in a way that enhances the insanity while leaving out any sense or emotional involvement the original might have had. You end up with a story whose only appeal is the occasional bits of slapstick humor and nonsense.

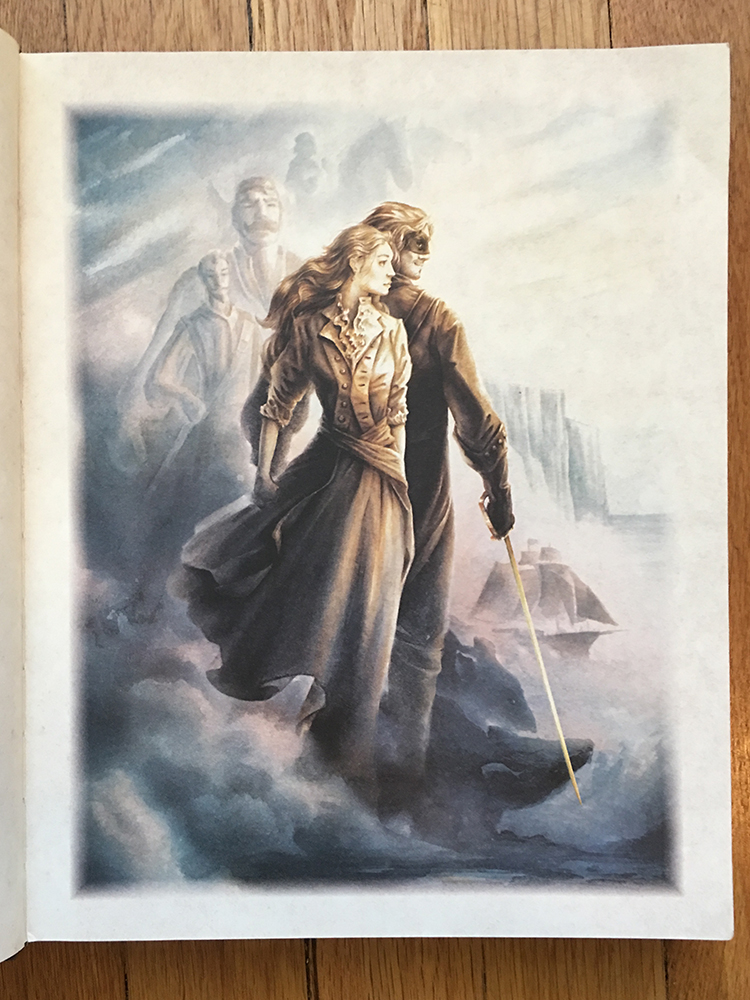

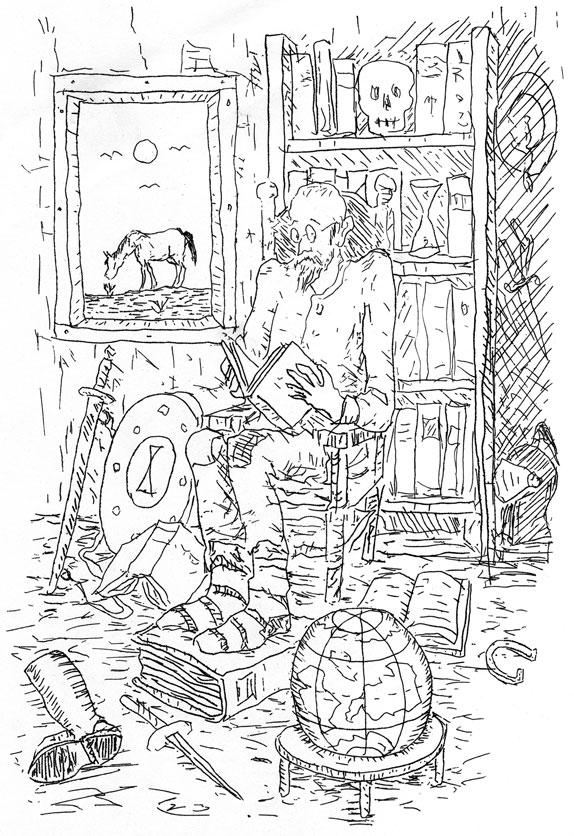

Stranger still was the decision to hire a brilliant illustrator, Chris Riddell, who created a wealth of hilarious illustrations, which the book designer then hid, for the most part, behind opaque blocks of text, so that only bits of them are peeking out. This is a large, handsome volume, with pictures on nearly every spread, printed on heavy, glossy stock, and the price reflects this. But they have done a disservice to the illustrator, and chosen and rewritten the story in a way that will have limited appeal to its target audience.

From the Book: Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember, a gentleman lived not long ago, one of those who has a lance and ancient shield on a shelf and keeps a skinny nag and a greyhound for racing. An occasional stew, beef more often than lamb, hash most nights, eggs and abstinence on Saturdays, lentils on Fridays, sometimes squab as a treat on Sundays -- these consumed three-fourths of his income. The rest went for a light woolen tunic and velvet breeches and hose of the same material for feast days, while weekdays were honored with dun-colored coarse cloth. He had a housekeeper past forty, a niece not yet twenty, and a man-of-all-work who did everything from saddling the horse to pruning the trees. Our gentleman was approximately fifty years old; his complexion was weathered, his flesh scrawny, his face gaunt, and he was a very early riser and a great lover of the hunt. Some claim that his family name was Quixada, or Quexada, for there is a certain amount of disagreement among the authors who write of this matter, although reliable conjecture seems to indicate that his name was Quexana. But this does not matter very much to our story; in its telling there is absolutely no deviation from the truth.

Talk to Your Kids About ...

Families can talk about retellings of classic stories. Do you think it's a good idea? Why or why not? Have you read any before? Did you like them? Why do you think writers and publishers create them?

Book Details

- Author : Martin Jenkins

- Illustrator : Chris Riddell

- Genre : Literary Fiction

- Book type : Fiction

- Publisher : Candlewick Press

- Publication date : April 1, 2009

- Publisher's recommended age(s) : 10 - 14

- Number of pages : 347

- Last updated : July 12, 2017

Did we miss something on diversity?

Research shows a connection between kids' healthy self-esteem and positive portrayals in media. That's why we've added a new "Diverse Representations" section to our reviews that will be rolling out on an ongoing basis. You can help us help kids by suggesting a diversity update.

Suggest an Update

Our editors recommend.

The Adventures of Odysseus

Common Sense Media's unbiased ratings are created by expert reviewers and aren't influenced by the product's creators or by any of our funders, affiliates, or partners.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

'don quixote' speaks to the 'quality of being a dreamer'.

NPR's Robert Siegel speaks with Ilan Stavans about his book, Quixote: The Novel and the World. Stavans was inspired by the Miguel de Cervantes' classic, Don Quixote, which turns 400 this year.

Copyright © 2015 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Books: A true story

Book reviews and some (mostly funny) true stories of my life.

Book Review: Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

August 23, 2016 By Jessica Filed Under: Book Review 1 Comment

Don Quixote

Don Quixote has become so entranced by reading chivalric romances, that he determines to become a knight-errant himself. In the company of his faithful squire, Sancho Panza, his exploits blossom in all sorts of wonderful ways. While Quixote's fancy often leads him astray – he tilts at windmills, imagining them to be giants – Sancho acquires cunning and a certain sagacity. Sane madman and wise fool, they roam the world together, and together they have haunted readers' imaginations for nearly four hundred years. With its experimental form and literary playfulness, Don Quixote generally has been recognized as the first modern novel. The book has had enormous influence on a host of writers, from Fielding and Sterne to Flaubert, Dickens, Melville, and Faulkner, who reread it once a year, "just as some people read the Bible."

Don Quixote has the humor of Nacho Libre and a weird blend of fantasy and reality that I can only compare to Galaxy Quest . I. Loved. This. Book. I was surprised how funny it was. Like laugh-out-loud funny with crude potty humor (my favorite) and violence that the Three Stooges would love. For example, Don Quixote does something absolutely crazy until I can’t stand him but then he gets the crap beaten out of him so I felt sorry for him and kind of liked him again until, of course, he does something crazy again. It actually takes a while to get tired of that cycle because it manages to be funny every time. By the time I was tired of it, Don Quixote started to change and develop more. The story is tragic, too, so it has some depth (but even the tragedy manages to be kind of funny).

If you read this novel in high school and feel like you didn’t read the same book as me, YOU DIDN’T. You need to read the Edith Grossman translation. It’s amazing. It flows well. It’s modern enough to understand yet she worked hard to keep as much of the context of the time period and language as possible. The style feels similar to reading Jane Austen. It’s not totally modern but not old enough that it’s hard to understand. Edith’s footnotes in this novel were great. They gave context when needed. They pointed out plot holes that I didn’t even notice like someone in the room talking even though the author never mentioned them coming in. She also did her best to explain the word play humor that sadly didn’t translate to English. If you’re still not convinced to read it because it’s long, I can tell you that the reason it’s so long is because there are chivalric novellas inserted into the narrative. They’re good stories but if you are intimidated by how long it is, you could skip these novellas.

If Don Quixote was going to be written today, it would be about video games rotting someone’s brains and they tried to bring the rules of video games into real life.

This is how the book describes Don Quixote:

In short, our gentleman became so caught up in reading that he spent his nights reading from dusk till dawn and his days reading from sunrise to sunset, and so with too little sleep and too much reading his brains dried up, causing him to lose his mind. -Cervantes, (translated by Edith Grossman). Don Quixote (p. 21).

So Don Quixote decides to become a chivalric knight after he loses his mind. His family is shocked by this and asks a priest for help. This priest goes through Don Quixote’s books to “help” him by getting rid of the evil ones. At first, I thought they were just going to burn them all. But as the conversation goes on, the priest starts to justify keeping some of the books he likes in long speeches. I almost died laughing at the hypocrisy of it.

There are several characters who are trying to “help” Don Quixote but they do it by pretending to believe everything Don Quixote says and does. Doesn’t that make them just as crazy as Don Quixote? Since the characters are pretending to go along with Don Quixote, it makes it so his imagination is literally influencing the plot. I’m also pretty sure he would have been “cured” sooner if they had left him alone and let reality teach him. The characters who are helping him are a judge, a priest and a barber which sounds like the perfect setup for a joke. “A judge, a priest and a barber walk into an inn…”

By part II, I started to wonder if maybe Don Quixote has a point. That maybe the world needs knights/heroes who go around the world doing good. Maybe we are the ones that are crazy to think that the world is fine the way it is and we don’t need to try and make it better even if we are aiming for an ideal that we can’t reach. At the very least, I started to admire his determination to do what makes him happy no matter what anyone else says.

The plot consists of random, unrelated events which usually bugs the crap out of me. But what kept me reading was the desire to know if this new, random event would finally be the thing that knocks some sense into Don Quixote.

I love the characters in this book. Sancho Panza is awesome. He was by far my favorite character. I imagined him kind of like this:

He reminds me of Nacho from Nacho Libre. He’s the source of most of the humor. I could hardly breath when Sancho has “done something with my person I shouldn’t have (p. 148).” I won’t spoil it but basically it’s totally immature bathroom humor. It’s written in such lovely language to contrast the crude humor that it’s literally the funniest thing I’ve ever read .

Don Quixote and Sancho don’t always get along and it was immensely entertaining to read. Don Quixote gets mad at Sancho’s logic quite frequently. Sancho tries to sound wise by saying every proverb he’s ever heard whether it applies to the situation or not. He also likes to switch his words around like in this next quote (and it makes Don Quixote really mad lol):

“ Censuring is what you should say,” said Don Quixote, “and not sentencing , you corrupter of good language, may God confound you!” – Cervantes (translated by Edith Grossman). Don Quixote (p. 579).

Sancho is also a little bit of a Captain Obvious and states obvious things which annoys Don Quixote and made me laugh. Still, the great thing about Sancho is that despite his nonsense, his simple-mindedness often appears wiser than Don Quixote which make them a great, contrasting pair.

My favorite thing about the movie Galaxy Quest is that the characters have to live through the ridiculous science-fiction that you see in shows like Star Trek in real life.

Don Quixote is like that, too. He tries to imitate the highly stylized and totally unrealistic life of a knight in real life.

There are poems at the beginning that are easy to skip, but don’t. Or at least listen to them on audiobook. They are written in a style where some of the syllables are missing and it’s hilarious. Having it read out loud sounds like someone getting punched in the gut halfway through each line. The poems are also the first example of this weird mix of fantasy and reality. The poems are stories of the real characters in Don Quixote talking to famous characters from other chivalry novels.

In Part II, the characters in the book have read Part I and the fact that they’ve read Part I influences what they do in Part II. The characters react to the real life reception of the novel when they meet characters who have read it. And the characters they meet are both fans and critics. It’s so bizarre and fun and it works.

Cervantes claims to be re-writing a translation of someone else’s story about Don Quixote so the author becomes a character in his own book . The priest, when he is going through Don Quixote’s books, finds one written by Cervantes and says it’s a good book. THIS IS SO WEIRD I LOVE IT. Also in Part I, Cervantes wrote a few plot holes that are addressed in Part II. Cervantes doesn’t just clarify them. He has the characters themselves explain the plot holes and be mad that the author didn’t keep an accurate history.

Cervantes made a lot of references to real chilvaric novels throughout the book. I could tell that Cervantes really knew what he was making fun of. But by the end of the book, I still couldn’t tell if that meant he loved chilary novels or hated them. I think that’s a sign of brilliant satire.

Don Quixote refuses to eat because he’s trying to emulate knights from the books he’s read and it never mentions them eating. This is so funny I can’t even….

I learned so much from reading this book. Like did you know that Don Quixote is considered the first modern novel? And it inspired Dickens, Flaubert, Joyce and Prouse? Part I has chapter breaks according to the events in the novel but Part II develops into the traditional novel where the chapter breaks are based on the emotions of the characters. We get to hear more often what the characters think (I got that from Sparknotes just FYI).

Just to add to the nerdiness of this review, here are a few other interesting tidbits that I learned from Sparknotes about Don Quixote (aka stuff you could rip off for a book report):

- There’s actually quite a bit of Spanish history in the novel.

- This novel challenged the idea of class and worth making it revolutionary for it’s time.

- There are books everywhere in the novel and they show the power that books and ideas can have in our lives – for good or bad and regardless if they are fiction or not.

- Don Quixote as a character is likable yet hate-able at the same time. He has good intentions but he still hurts others.

- Cervantes disagrees with the fake translator on whether Don Quixotes’ actions were good or not leaving it up to the reader to decide.

- The writing style sounds like a transcription of an oral history sometimes. One of the themes in Don Quixote is story-telling and Cervantes likes to mess around with all kinds of story formats – poems, epic, novels, oral stories etc.

Now let’s talk about feminism which does actually exist in this book. A bit. Don Quixote meets a girl who is so beautiful that a man claims that he “has” to fall in love with her and she has to return his love or he will die. Yeah she calls BS on that one on goes on her happy, independent way. Sadly, the rest of the female characters are flat and valued only by their looks but it’s hard to tell if this was part of the satire or not… I mean every other female character in the book is sooooooo beautiful. Too many drop-dead gorgeous ladies without personalities to keep track of. Blech.

The audiobook was fantastic. I switched back and forth between the audiobook and ebook. The voices that the narrator did were so good that they got stuck in my head even when I was reading the ebook.

In the prologue, Cervantes describes what the perfect novel should do:

…move the melancholy to laughter, increase the joy of the cheerful, not irritate the simple, fill the clever with admiration for its invention, not give the serious reason to scorn it, and allow the prudent to praise it. -Cervantes, (translated by Edith Grossman). Don Quixote (p. 8).

In other words, the best books should:

..achieve the greatest goal of any writing, which, as I have said, is to teach and delight at the same time. -Cervantes, (translated by Edith Grossman). Don Quixote (p. 414).

It’s the perfect description of the perfect novel and I think Don Quixote lives up to that.

PS. The Ending View Spoiler » At the end, on Don Quixote’s tombstone, it says: “for it was his great good fortune to live a madman, and die sane (p. 939).” Wow. That’s kind of deep. Does it mean that complete sanity is so sad that it’s best only to experience right before you die? Also, it was sad that Don Quixote died. But it made sense. For him to be sane it would go against who he is and if he stops being who he is it’s kind of the same as dying. « Hide Spoiler

Book Review of Don Quixote on a Post-it

For more reviews like this, be sure to follow me on Instagram !

About Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was a Spanish novelist, poet, and playwright. His novel Don Quixote is often considered his magnum opus, as well as the first modern novel.

It is assumed that Miguel de Cervantes was born in Alcalá de Henares. His father was Rodrigo de Cervantes, a surgeon of cordoban descent. Little is known of his mother Leonor de Cortinas, except that she was a native of Arganda del Rey.

In 1569, Cervantes moved to Italy, where he served as a valet to Giulio Acquaviva, a wealthy priest who was elevated to cardinal the next year. By then, Cervantes had enlisted as a soldier in a Spanish Navy infantry regiment and continued his military life until 1575, when he was captured by Algerian corsairs. He was then released on ransom from his captors by his parents and the Trinitarians, a Catholic religious order. He subsequently returned to his family in Madrid.

In Esquivias (Province of Toledo), on 12 December 1584, he married the much younger Catalina de Salazar y Palacios (Toledo, Esquivias –, 31 October 1626), daughter of Fernando de Salazar y Vozmediano and Catalina de Palacios. Her uncle Alonso de Quesada y Salazar is said to have inspired the character of Don Quixote. During the next 20 years Cervantes led a nomadic existence, working as a purchasing agent for the Spanish Armada and as a tax collector. He suffered a bankruptcy and was imprisoned at least twice (1597 and 1602) for irregularities in his accounts. Between 1596 and 1600, he lived primarily in Seville. In 1606, Cervantes settled in Madrid, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Cervantes died in Madrid on April 23, 1616.

Reading this book contributed to these challenges:

- Classics Club

August 23, 2016 at 10:52 am

Wow! I’ve never heard of anyone raving about this book as much as this. I’ve always wanted to read Don Quixote, but it is one of those books that really intimidate me.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

email subscription

Tiger Riding for Beginners

Bernie gourley: traveling poet-philosopher & aspiring puddle dancer.

BOOK REVIEW: Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

Amazon.in page

Project Gutenberg page

DON QUIXOTE is among the earliest novels, and – owning to its humor and thought-provoking story – it continues to be one of the world’s most important literary works. The book tells the tale of a Spanish gentleman, Alonzo Quixano, who has a combination midlife crisis and breakdown of sanity that result in his adoption of the new name Don Quixote de La Mancha (a.k.a. Knight of the Rueful Countenance, and [later] Knight of the Lions) and his setting off as a knight errant (i.e. a roving warrior in search of adventure, competition, and opportunities to be virtuous / chivalrous.) We are told that this breakdown is the culmination of obsessive reading of books on Chivalry. These books were the pulp fiction of the time: low-brow, sensationalist, and – to the scholarly-minded — pointless. A recurring debate throughout the book is whether these books are harmful and should be avoided or whether they are a harmless amusement that may even have benefits. For Don Quixote, they are neither; he sees them as a truthful depiction of how knights live an behave.

The book is divided into two parts. In the first part, Don Quixote makes two journeys away from his village in La Mancha. The first trip is short-lived, beginning with some preliminaries before he can strike out as a knight. A handy series of delusions help set events in motion. In his mind, an old broken-down horse becomes “Rocinante” (a regal knight’s steed.) A beautiful farmgirl who he has never met becomes the Lady Duclinea del Toboso – object of his affections [unbeknownst to her.] Finally, an innkeeper becomes the King who Don Quixote asks for knighthood [which the bewildered innkeeper bestows upon the deranged old man.] Shortly thereafter, Don Quixote takes his first beating and is taken back home.

During this time period, his concerned staff and neighbors burn all his books on Chivalry, but that has little impact [possibly because he’s already read all the books and knows them by heart] and soon Don Quixote is riding out on his second sally — this time with his squire, Sancho Panza. Don Quixote is able to face quite a number of ignominious adventures during this outing, including his famous charge on the windmills – which he sees as giant arm-swinging monsters. [From whence the turn of phrase “tilting at windmills” derives to describe the behavior of charging into a futile and ill-advised battle with an illusory enemy.] At the end of the first part, Don Quixote is dragged back to his village by the curate and the barber (two men interested in saving Don Quixote from his madness.) Believing he is under an enchantment, Don Quixote is able to be returned home with minimal kicking and screaming.

Part two of the book continues the adventures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza as they again leave their home village. It’s worth noting that Cervantes presents this work as if it were a book within a book – in other words, as if he’s presenting collected tales of the life of Don Quixote as they were presented in other volumes. This creates some amusing instances of the literary equivalent of fourth wall breaking. I found that the second part did feel different from the first. Whereas, part one comes across as a conglomeration of tales, a through-flow of story is more apparent in the second part. The two parts weren’t released together, and so there is probably good reason for this besides a literary decision to change styles. The second part has been said to be more reflective – rather than pure farce – and that makes sense as Cervantes had about a decade to ponder what he wanted to say. Much of the second part revolves around the activities of a Duke and Duchess who prank Don Quixote. By this time, the first volume of Don Quixote’s exploits has been in publication for a while and the “knight errant” is well-known as a madman and a buffoon.

Pranking both Don Quixote and Sancho Panza is a challenge as the two men are quite different in their vulnerabilities. The Duke and Duchess can use suggestion to exploit Don Quixote’s inclination to mentally conjure grandiose, romantic scenarios. However, Sancho Panza is of sound mind and has a kind of pragmatic insightfulness and so they must – instead — exploit his lack of sophistication and cowardice. The Duke gives Sancho Panza governorship of an island – something that Don Quixote has been promising he would give his squire as soon as some King or Queen saw fit to reward him for his virtuous service as a knight errant – which, of course, is not forthcoming. Sancho rules for only ten days before his hunger and cowardice reach their limits in the face of: first, a doctor who puts him on a calorie-restrictive diet for the health benefits; and, second, a mock attack on his island.

The book ends after a second battle with a disguised Sanson Carrasco. Carrasco, far from the knight seeking fame that he pretends to be, is a villager from La Mancha who wants to see Don Quixote return home to get well. He “battles” Don Quixote once as the Knight of Mirrors about midway through the book, but is defeated (more through a combination of his own inexperience and bad luck than as a result of Don Quixote’s skill.) On this second occasion, he fights as the Knight of the White Moon and defeats Don Quixote – who is forced by the dictates of the wager to return home. At first, Don Quixote plays like he might try out the shepherd’s life for a year, but soon he falls into a funk. Before he dies, he reclaims the name Alonzo Quixano and acknowledges that he’d been out of his mind and that all of his adventures in knight errantry were a farce.

Returning to the question of whether the chivalry books are harmful and should be avoided at all costs or whether they are entertainment with some redeeming features, the reader is really left leeway to conclude as he or she sees fit. It’s worth noting that this wasn’t a new question. Plato and his most famous student, Aristotle, argued this same question. Plato believed that all these exciting stories could do is incite people to violence and other unproductive endeavors. Aristotle believed that there could be catharsis (purging of emotions) through dramatic works.

At first blush, it might seem clear to the reader that Cervantes is saying that these works are detrimental. He proposes that they, literally, dried out Don Quixote’s brain and turned him into a madman. However, one might come to feel differently as one sees the influence that Don Quixote has on people. While everyone recognize that he is a madman, most also recognize that he has a sort of wisdom and courage about him. He stands for virtuosity, even if he doesn’t have the power to back it up with weapons that he imagines he does. Sancho Panza also has a sort of wisdom, and one suspects that this sagacity has increased through his exposure to Don Quixote. For the brief time that Sancho Panza is governor, he makes some sound decisions and he never exploits his position to his own gain. While none of the battles of Don Quixote amount to much, people are moved by his advice and his virtuous example.

This is a hard book not to love. I will admit to thinking that — particularly in Part one –it could have benefited from an editor, but given its seminal literary position, it’s hard to give this criticism much weight. [What I mean by it is that there are numerous repetitive examples of Don Quixote mistaking one thing for another and getting into an unwise fight throughout the first part, few of these scenes are anywhere near as effective as the relatively early ‘tilting at windmills’ scene. Therefore, there is a bit of tedium in these scenes.] That said, the book is witty is places and laugh-out-loud funny in others, and it offers philosophical food-for-thought while never being overbearing in the process. If you read fiction, you should definitely read this book.

View all my reviews

Share on Facebook, Twitter, Email, etc.

- Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes" data-content="https://berniegourley.com/2020/09/30/book-review-don-quixote-by-miguel-de-cervantes/" title="Share on Tumblr">Share on Tumblr

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Advertisement

Supported by

Critic’s Take

In Exile With ‘Don Quixote’

By Ariel Dorfman

- Oct. 7, 2016

- Share full article

Of the myriad times since adolescence that I have returned to the story of Don Quixote de la Mancha, there is one I choose to remember — that I cannot help but remember — as we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the death of Miguel de Cervantes. That reading, in October 1973, took place among a distraught group of captive men and women who, like me, had sought asylum in the Argentine Embassy in Santiago, Chile, after the coup that overthrew the democratic government of Salvador Allende.

In an atmosphere in which a thousand future exiles were suffocating in rooms designed to host cocktail parties, I joined a group of some 30 refugees who were reading it aloud together. Conceived as a sort of literary therapy to fight depression among us, I soon discovered that these readers had much to teach me. Many of them had come to our country from the failed revolutions of other Latin American lands, had been locked away for prolonged periods of time, and suffered torture and banishment. They instinctively understood Cervantes, who like them had been the victim of astonishing adversity and had become immensely resourceful in a cruel and disenchanted world.

Indeed, the defining experience of Cervantes’s life was the harrowing five years starting in 1575 that he spent in the dungeons of Algiers as a prisoner of the Barbary pirates. It was there, on the border of Islam and the West, that Cervantes came to appreciate the value of tolerance toward those who are radically different, and it was there he discovered that of all the goods men can aspire to, freedom is by far the greatest. While awaiting a ransom that his family could not pay, confronted with execution each time he attempted to escape, watching his fellow slaves tormented and impaled, he longed for a life without manacles. But once he returned to Spain, a crippled war veteran neglected by those who had sent him into conflict, he came to the conclusion that if we cannot heal the misfortunes that assail our bodies, we can, however, hold sway over how our soul responds to those sorrows.

“Don Quixote” was born of that revelation. In the prologue to Part 1 of his novel he tells the “idle reader” that it was “begotten in a prison, where every discomfort has its place and every sad sound makes its home.” Whether that jail was in Seville or in Castro del Río, this recurring experience of incarceration forced him to revisit the Algerian ordeal and put him face to face with a dilemma that he resolved to our joy: Either succumb to the bitterness of despair or let loose the wings of the imagination. The result was a book that pushed the limits of creativity, subverting every tradition and convention. Instead of a rancorous indictment of a decaying Spain that had rejected and censored him, Cervantes invented a tour de force as playful and ironic as it was multifaceted, laying the ground for all the wild experiments the novelistic genre was to undergo.

Cervantes realized that we are all madmen constantly outpaced by history, fragile humans shackled to bodies that are doomed to eat and sleep, make love and die, made ridiculous and also glorious by the ideals we harbor. To put it bluntly, he discovered the vast psychological and social territory of the ambiguous modern condition. Captives of a harsh and unyielding reality, we are also simultaneously graced by the constant ability to surpass its battering blows.

Those of us reading “Don Quixote” in 1973, in an embassy we could not leave, surrounded by soldiers ready to transport us to stadiums and cellars and, ultimately, cemeteries, responded viscerally to the novel. That continuous exaltation and practice of liberty, both personal and aesthetic, was inspiring. This faith was epitomized by a passage from Part 2 of “Don Quixote” that moved us to tears.

Sancho Panza has been made governor of a fictitious island by a frivolous duke. The lowly squire proves to be a far wiser and more compassionate ruler than the noblemen who mock him and his master. One night, doing the rounds, he comes upon a young lad who is running away from a constable. The boy gets cheeky, and the ersatz governor sentences him to sleep in prison. Infuriatingly, the prisoner insists that he can be put in chains but that no one has the power to make him sleep: Staying awake or not depends on his own volition and not on anyone else’s commands. Chastened by the lad’s independence, Sancho lets him go.

It is an episode that has stayed with me. If I recall it now, it is because I feel it contains the essential message Cervantes still has for today’s desperate humanity.

True, most of the planet’s inhabitants are not in prison, as Cervantes so often was, nor do they find themselves confined within walls, like the revolutionaries in the Argentine Embassy. And yet we live, as if captured, in a time of violence and inequality, greed and stupidity, intolerance and xenophobia, marooned on a planet spinning out of control — like lunatics sleepwalking toward the abyss.

Cervantes died 400 years ago, and yet he continues to send us words — like the wisdom of that boy threatened by Sancho Panza — that we need to meditate upon before it is too late. Nobody has the power to make us sleep if we don’t wish it ourselves. Cervantes is telling us that our besieged, besotted, captive humanity should not lose hope that we can awaken in time.

Ariel Dorfman is the author, most recently, of “Feeding on Dreams.”

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30 , yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety .

“Real Americans,” a new novel by Rachel Khong , follows three generations of Chinese Americans as they all fight for self-determination in their own way .

“The Chocolate War,” published 50 years ago, became one of the most challenged books in the United States. Its author, Robert Cormier, spent years fighting attempts to ban it .

Joan Didion’s distinctive prose and sharp eye were tuned to an outsider’s frequency, telling us about ourselves in essays that are almost reflexively skeptical. Here are her essential works .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

100 of the Greatest Books Read and Reviewed

100 of the World's Greatest books – classics that demand attention and have a lot to say to us today. This is a quest to read and review that top 100 classics, however long that journey may be!

“Don Quixote” by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (Review)

Don Quixote is one of those truly weighty classics that one know something about even if one has never worked their way through the 1000 plus pages that make up the two books telling the tale of the worthy, though slightly mad Don and his faithful Sancho.

Since this book was written in the 1600s it has a long and storied history in the annals of literature. Of course, it is translated from Spanish so it is bound to lose something in translation (maybe even from 1600s Spanish to modern Spanish?) but since my language skills are poor I don’t have a choice unfortunately.

There is also quite the history to Quixote of which I was unaware prior to reading the book and researching it a little. It covers the wanderings (quixotic having entered the lexicon) of the titular character and his long suffering sidekick and squire Sancho Panza. The book is in two parts, written a decade apart although they are basically of a similar ilk. The cover Quixote’s obsession with chivalry and knight errantry that he learned from reading books. It is strongly implied, especially in the second half, that Quixote is mad. There is quite the evidence to suggest this throughout (tilting at windmills, seeing all inns as castles) the narrative but it is more up front in part 2.

Cervantes seems to really admire Quixote and is always writing about his good heart. Panza, too, is given sympathetic treatment and is quite the comical character although, of course we are seeing the wise fool versus the foolish wise man. The literary style of the novel has been commented upon by people a lot more erudite than me but it is very interesting, interspersed as it is with sub stories (including the introduction of another widely used term in “Lothario”) that sometimes cover a lot of ground in their own right.

The wanderings are long and frankly, sometimes I was rather lost in the lengthy descriptions of events but the development of the relationships is fascinating and well explained, but wow, it takes a lot of time to work through this novel. However that seems to be true of all such epic novels and I am glad that I made the effort and I feel more able to understand the terms that have made it into common usage as a result of the influence of this novel. It takes some reading though!

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

DON QUIXOTE

The new translation by gerald j. davis.

by Miguel de Cervantes translated by Gerald J. Davis ‧ RELEASE DATE: May 3, 2012

Split between old and new, this translation seeks a niche audience.

This new translation of the beloved classic attempts to return to the roots of its earliest English translation.

With numerous English translations of Don Quixote already in existence, any new translator will have much to prove. Davis’ ( Jungle of Glass , 2011) translation results from his attempt to preserve “the voice of the [Thomas] Shelton translation,” the earliest Quixote in English, in order to give a contemporary audience the sense of how the 17th-century masterpiece originally read. Even though Shelton translated the second part of the novel, Davis neglects it, which may disappoint some readers, as Cervantes provides some of his most piercing psychological and philosophical insights in the sequel. In Davis’ rendering, the register ascends above most current translations, preferring “a seventeenth century sensibility” over readability for a contemporary audience. This stylistic choice leads to stilted prose, especially in dialogue, where Davis provides the characters with lofty affectations informed by antiquated etiquette. That’s not to say, though, that this edition reaches the syrupy decadence of Peter Motteux’s early translation. Thus, Davis’ Quixote hovers between eras, neither transforming Cervantes’ novel into plain, current English nor infusing it with full-on Spanish Golden Age textures. The compromise attempts to harness the best of both eras, although the result can sometimes feel disjointed and ignorant of Cervantes’ dry sarcasm. The most readable passages occur during action scenes (even when the action takes place in Quixote’s imagination), where Davis deftly navigates the text, often with great gusto. His translation bypasses literalism, freely rearranging syntax and diction, and his arrangements create a colorful atmosphere and flavor, though some scholars may disagree with the mild poetic liberties he has taken. With so many translations available, Davis’ Quixote provides a unique path through the work, which, though it remains incomplete, should find a readership in those interested in the gaps between the language of Cervantes’ time and ours.

Pub Date: May 3, 2012

ISBN: 978-1477401194

Page Count: 362

Publisher: Lulu

Review Posted Online: July 16, 2012

Review Program: Kirkus Indie

Share your opinion of this book

More by Miguel de Cervantes

BOOK REVIEW

by Miguel de Cervantes ; translated by Edith Grossman ; edited by Roberto González Echevarría

JUPITER STORM

by Marti Dumas illustrated by Stephanie Parcus ‧ RELEASE DATE: Nov. 11, 2017

In more ways than one, a tale about young creatures testing their wings; a moving, entertaining winner.

A fifth-grade New Orleans girl discovers a mysterious chrysalis containing an unexpected creature in this middle-grade novel.

Jacquelyn Marie Johnson, called Jackie, is a 10-year-old African-American girl, the second oldest and the only girl of six siblings. She’s responsible, smart, and enjoys being in charge; she likes “paper dolls and long division and imagining things she had never seen.” Normally, Jackie has no trouble obeying her strict but loving parents. But when her potted snapdragon acquires a peculiar egg or maybe a chrysalis (she dubs it a chrysalegg), Jackie’s strong desire to protect it runs up against her mother’s rule against plants in the house. Jackie doesn’t exactly mean to lie, but she tells her mother she needs to keep the snapdragon in her room for a science project and gets permission. Jackie draws the chrysalegg daily, waiting for something to happen as it gets larger. When the amazing creature inside breaks free, Jackie is more determined than ever to protect it, but this leads her further into secrets and lies. The results when her parents find out are painful, and resolving the problem will take courage, honesty, and trust. Dumas ( Jaden Toussaint, the Greatest: Episode 5 , 2017, etc.) presents a very likable character in Jackie. At 10, she’s young enough to enjoy playing with paper dolls but has a maturity that even older kids can lack. She’s resourceful, as when she wants to measure a red spot on the chrysalegg; lacking calipers, she fashions one from her hairpin. Jackie’s inward struggle about what to obey—her dearest wishes or the parents she loves—is one many readers will understand. The book complicates this question by making Jackie’s parents, especially her mother, strict (as one might expect to keep order in a large family) but undeniably loving and protective as well—it’s not just a question of outwitting clueless adults. Jackie’s feelings about the creature (tender and responsible but also more than a little obsessive) are similarly shaded rather than black-and-white. The ending suggests that an intriguing sequel is to come.

Pub Date: Nov. 11, 2017

ISBN: 978-1-943169-32-0

Page Count: 212

Publisher: Plum Street Press

Review Posted Online: Feb. 22, 2018

Kirkus Reviews Issue: April 15, 2018

More by Marti Dumas

by Marti Dumas

BROTHERS IN ARMS

Bluford high series #9.

by Paul Langan Ben Alirez ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 1, 2004

A YA novel that treats its subject and its readers with respect while delivering an engaging story.

In the ninth book in the Bluford young-adult series, a young Latino man walks away from violence—but at great personal cost.

In a large Southern California city, 16-year-old Martin Luna hangs out on the fringes of gang life. He’s disaffected, fatherless and increasingly drawn into the orbit of the older, rougher Frankie. When a stray bullet kills Martin’s adored 8-year-old brother, Huero, Martin seems to be heading into a life of crime. But Martin’s mother, determined not to lose another son, moves him to another neighborhood—the fictional town of Bluford, where he attends the racially diverse Bluford High. At his new school, the still-grieving Martin quickly makes enemies and gets into trouble. But he also makes friends with a kind English teacher and catches the eye of Vicky, a smart, pretty and outgoing Bluford student. Martin’s first-person narration supplies much of the book’s power. His dialogue is plain, but realistic and believable, and the authors wisely avoid the temptation to lard his speech with dated and potentially embarrassing slang. The author draws a vivid and affecting picture of Martin’s pain and confusion, bringing a tight-lipped teenager to life. In fact, Martin’s character is so well drawn that when he realizes the truth about his friend Frankie, readers won’t feel as if they are watching an after-school special, but as though they are observing the natural progression of Martin’s personal growth. This short novel appears to be aimed at urban teens who don’t often see their neighborhoods portrayed in young-adult fiction, but its sophisticated characters and affecting story will likely have much wider appeal.

Pub Date: Jan. 1, 2004

ISBN: 978-1591940173

Page Count: 152

Publisher: Townsend Press

Review Posted Online: Jan. 26, 2013

More by Paul Langan

by Paul Langan

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

May 23, 2024

Current Issue

Anything Can Happen

October 21, 2021 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

Artizon Museum, Tokyo

Honoré Daumier: Don Quixote in the Mountains circa 1850

I don’t think I understand what Don Quixote is about, and I don’t think anybody knows what Don Quixote is about.

—Keith Dewhurst, author of the play Don Quixote (1982)

Miguel de Cervantes concluded The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote of La Mancha in 1605 with a phrase in Italian from Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso : “ Forse altro canterà con miglior plettro ” (Perhaps another will sing with a better [guitar] pick). While his book was selling in record numbers, Cervantes turned to short stories and pastoral poetry. In 1614 the pseudonymous Alonzo Fernández de Avellaneda published an unauthorized sequel to Don Quixote , prompting a furioso Cervantes to publish his own second volume of the novel a year later. Attributing its authorship, as he had that of volume 1, to the mythical Arab scholar Cid Hamet Benengeli, Cervantes exacted revenge. In chapter 70, devils battered the presumptuous Fernández’s manuscript with tennis rackets so “that the very insides flew out of it”:

“Away with it,” cried the first devil, “down with it, plunge it to the lowest pit of Hell, where I may never see it more.” “Why is it such sad stuff?” said the other. “Such intolerable stuff,” cried the first devil, “that if I and all the devils in Hell should set their heads together to make it worse, it were past our skill.”

Cervantes contrived in volume 2 to forestall further appropriation by granting Don Quixote a “natural death.” The priest at the knight’s bedside called on a scribe to certify his demise in writing, “lest any other author but Cid Hamet Benengeli should take occasion to raise him from the dead, and presume to write endless histories of his adventures.” But burying Quixote proved as futile as Arthur Conan Doyle’s murder of Sherlock Holmes at the Reichenbach Falls.

Don Quixote, like Achilles, Odysseus, Faust, and Don Juan, refuses the grave. Novels, dramas, operas, poems, movies, paintings, and sculptures resurrect him and his loyal squire, Sancho Panza, in every century. In the twenty-first, it is the turn of Ariel Dorfman and Salman Rushdie. Despite drawing from the same source, the two American-resident exiles have produced very different novels, whose charms might just spare them Cervantes’s flames of eternal damnation.

Notions of authorship, creator, and creatures, as well as of love, folly, and imagination, dominate Rushdie’s and Dorfman’s pages as they did Cervantes’s. Who conceived Quixote and Sancho? The nonexistent Benengeli? Cervantes? Or Pierre Menard, Jorge Luis Borges’s fictional early-twentieth-century scholar who was so obsessed with Cervantes that he set out to reproduce word for word “the ninth and thirty-eighth chapters of part 1 of Don Quixote and a fragment of the twenty-second chapter.” Borges, in truly Borgesian fashion, delivered a capricious judgment: “The text of Cervantes and that of Menard are verbally identical, but the second is almost infinitely richer.” Cervantes, through intention or accident, invited not only imitation but absurdity.

The key to Quixote’s and Sancho’s enduring appeal may lie in an observation by Dr. Arthur Brock, the Scottish psychiatrist who treated the World War I poet Wilfred Owen for shell shock at the Craiglockhart War Hospital:

Sancho Panza and his romantic crack-brained master were perhaps less “thought out” by Cervantes than they were direct offsprings from his sub-conscious mind. Like the vivid symbols of dream-life, the creations of genius are really too good to be merely, or even mainly, intellectual products.

In Dorfman’s novel, Cautivos , Quixote springs straight out of Cervantes’s unconscious on October 31, 1580, when the future author “sank to his knees on the beach in Valencia and kissed the ground, that was it, that was the moment chosen for me [Quixote] to emerge from oblivion.”

Cervantes quotes Cid Hamet Benengeli, “For me alone was the great Quixote born, and I alone for him,” whereas Dorfman’s Quixote thinks, “Without Miguel de Cervantes, I was nothing.” Cautivos is the biography of an author by his character. Cervantes has escaped to Valencia from five years of slavery, torture, and humiliation in Algeria, unaware of the fictional being observing him in hope of being written into full existence. Although Cervantes is a wounded hero of Spain’s victory over the Ottoman fleet at Lepanto, Spanish officials greet him with suspicion, interrogation, and further captivity. The interrogators Marín and Garrido and their notary, Carrasco—an “unholy trinity”—lead him to a hovel on the beach to demand proof that he did not cooperate with his Moorish captors. He remains silent before his inquisitors, much to the invisible Quixote’s discomfort.

Marín, calling Cervantes “Miguelito,” dismisses him like a servant. The proud aristocrat rounds on his accusers, unwrapping letters from Christian cautivos (captives) in Algiers that he has promised to deliver to their families. He then relates in fury the story of his imprisonment and escape attempts, concluding, “Did your notary, this Carrasco, write it all down?” Readers of Cervantes will recall that a certain “bachelor,” Samson Carrasco, claimed to Sancho Panza that he and not Cid Hamet Benengeli wrote the first book of Don Quixote , a claim for which Quixote punishes him. Marín and Garrido beg Cervantes’s “pardon for doubting his blood heritage and making lewd, absurd, nasty insinuations.”

The purpose of their questions was to determine his suitability for a mission to North Africa to spy on the Ottoman fleet. Quixote listens, fearing that his author’s life and thus his own will be snuffed out. Cervantes accepts, but his real goal is to see Zahara, the beautiful married Algerian woman he loves, and bring her to Spain. In Algiers, disguised as an Arab, he learns that the sultan’s ships are heading east to face the Persians, information he will take to Spain after seeing Zahara. Their lovemaking inflames Quixote—his first, somewhat shocking, exposure to carnality. Zahara refuses to leave Algiers, and a distraught Cervantes asks, “What can I do without you by my side?” Quixote tells us, “She responded with the one word I had been hoping to hear…‘Write.’” His story, he realizes, will be told. On Cervantes’s return to Spain, though, he is cast into prison in Seville. It is there that he hears the prisoners’ stories and reads them books of chivalry that will one day become the basis of his masterpiece, causing Quixote to reflect, “Only then do I understand that this is the best possible thing in the whole world that could have happened to us.”

Dorfman’s account is more or less faithful to what is known of Cervantes’s life, but the trick of a new narrator for an old story—Pat Barker’s retelling of the Iliad by Briseis in The Silence of the Girls is a magnificent example—lets us imagine the author and his creation in new ways. Dorfman incarnates Quixote out of Cervantes’s idealization of love, betrayals by government agents, and incarceration in the dungeons of Seville.

In Quichotte , Rushdie moves Cervantes’s tale from seventeenth-century Spain to the contemporary United States (pop. 331,883,986). (He provides population figures for the towns his Quixote—here called Quichotte—visits, one of many running jokes, like calling certain roadways and motels “historic.”) Quichotte is a transplanted Indian from Bombay whose name, Smile, is an Americanization of Ismail. Rushdie laces so many allusions and jokes into the novel that “Ismail” may refer to Melville’s “Call me Ishmael” and Ahab’s mad quest for the whale, which parallels Smile’s pursuit of an idealized woman. Or not. As the original Quixote’s lunacy derived from overconsumption of popular chivalric fables, Smile, “on account of his love for mindless television, had spent far too much of his life in the yellow light of tawdry motel rooms watching an excess of it.” For Smile, like Peter Sellers (a bogus Indian in more than one film) as Chauncey Gardiner in Being There , television is reality. His Dulcinea is Salma R. (Salma Regina?), a luscious starlet from his native Bombay, a brown Oprah Winfrey hosting a witless daytime reality show in New York, and an opioid addict. His “infatuation which he characterized, quite inaccurately, as love” prompts him, while listening to a recording of Jules Massenet’s opera Don Quichotte , to become Mister—feeling himself unworthy of the title Don—Quichotte, determined to win her through heroic deeds.

His cousin and employer, pharma tycoon Dr. R.K. Smile, arrives in a private jet to fire him from his job as a traveling drug salesman. The meeting takes place in a motel in “Flagstaff, Arizona (pop. 70,320).” Quichotte takes his sudden unemployment as fortuitous, telling his cousin, “I’ve got plenty to do. I’ll just drive.”

His Rocinante is an “old gunmetal grey Chevy Cruze” in which he sets off alone toward New York and Salma R. During a meteor shower near Moorcroft, Wyoming (pop. 1,063), a teenage boy miraculously materializes in the Cruze’s passenger seat. He is Sancho, the son Quichotte has lacked in a long and loveless life:

“My silly little Sancho, my big tall Sancho, my son, my sidekick, my squire! Hutch to my Starsky, Spock to my Kirk, Scully to my Mulder. BJ to my Hawkeye, Robin to my Batman!…”

“Cut it out, ‘Dad’,” the imaginary young man rejoined. “What’s in all this for me?”

Quichotte and Sancho embark on that familiar trope of American myth, the road trip, through a dystopian landscape. That’s just the first chapter. In chapter 2, Rushdie reveals that Quichotte is a fictional character in a novel being written by another Indian émigré from Bombay, who uses the nom de plume Sam DuChamp for his series of third-rate spy novels, called Five Eyes. Resisting the obvious reference to Marcel Duchamp, whose Portrait (Dulcinea) was exhibited in Paris in 1911, Rushdie has DuChamp’s readers “calling him Sam the Sham, like the ‘Wooly Bully’ guy, who drove to his gigs in a Packard hearse.”

The Quichotte book that DuChamp—whom Rushdie calls “Brother” rather than give him a “real” name—is writing is more than a novel within the novel. It is also a parallel story to DuChamp’s own: he and his protagonist share a birthplace, age, race, class, failings, naiveté, immigration status, and quest. DuChamp/Brother speculates, in Rushdie’s fusion of real and fictional, that his and Quichotte’s parents may frequent the same clubs. Brother’s and Quichotte’s stories unfold in alternating chapters, in which Quichotte gradually unhinges his creator. Far from purging his existential anxieties, writing about Quichotte came “close to triggering a flight response” in Brother. From his spy stories, he knew that “you can run but you can’t hide.” Rushdie, the author of both characters, opines, “Maybe writing about Quichotte was a way of running away from that truth.” Or, in Rushdie’s case, toward it—via the madness of men turned into mastodons in New Jersey, portals to other worlds, and, well, the apparent end of the universe. The author as creator can also be destroyer, and Rushdie toys with both.

“Outlining the plot of a Rushdie novel is a futile exercise in a brief review,” wrote the novelist Allan Massie in The Scotsman when Quichotte came out in Britain. The problem is no different in a long review, perhaps because Rushdie confronts the reader with a multiplicity of plots. It’s like a Marx Brothers movie, easier to enjoy than to analyze. Quichotte could be Pynchon on acid, except that Pynchon was on acid. This is the America of Gore Vidal’s comic novel Duluth , in which characters appear, disappear, and reappear as characters in the television series Duluth , written by one Rosemary Klein Kantor, who calls her plagiarism of other works “creation by other means.” Rushdie’s Quichotte lives in “The Age of Anything-Can-Happen,” and pretty much everything does. Sometimes things happen twice, first to Quichotte and then to DuChamp.

Dorfman and Rushdie both faced the prospect of murder by vicious regimes. Dorfman’s criticisms of Chile’s General Augusto Pinochet put him at risk of sharing the fate of former Chilean foreign minister Orlando Letelier, assassinated by Pinochet’s agents in 1976 in the supposed sanctuary of the United States. Rushdie received a death sentence from Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini in the famous fatwa against The Satanic Verses in 1989. It is little wonder that both were drawn to a tale by a seventeenth-century Spanish political prisoner whose own life was often in jeopardy.

The interplay between author and character—Cervantes and Quixote in Cautivos , Brother and Quichotte in Quichotte , not to mention between Rushdie and Dorfman and their dramatis personae—touches on a theme Georges Simenon treated in Maigret’s Memoirs (1951). Twenty years after publishing Pietr the Latvian , the first of seventy-five Maigret romans policiers , Simenon allowed illustrious Jules Maigret of the Police Judiciaire his own say. When Maigret meets Simenon, he observes his “hint of a Belgian accent” and questions whether “my investigations as told by him were more convincing—he may even have said more accurate—than as experienced by me.” Simenon rejects Maigret’s charge of gross misrepresentation: “The whole problem is to make something more real than life. Well, I’ve done that! I’ve made you more real than life.” But Maigret has had an effect on Simenon, telling his creator, “Do you know that with the course of time you’ve begun to walk and smoke your pipe and even to speak like your Maigret?”

Rushdie and Dorfman are unlikely to walk and speak like their Quixotes, but each has delved deep into the Knight of La Mancha’s soul to understand and perpetuate his enduring allure. Rushdie’s Quichotte is less mad than the humans-become-mastadons who are as incomprehensible and frightening to their neighbors as Donald Trump’s devotees are to the uninitiated. Dorfman’s cautivo sees his creator, like Maigret sees Simenon, more clearly than Cervantes sees himself. Both novels, like their model, are riddles to be deciphered in myriad ways.

Cervantes, Borges, Dorfman, and Rushdie would undoubtedly concur with Yogi Berra: “When you get to the fork in the road, take it.”

October 21, 2021

The Storyteller

‘Who Designs Your Race?’

Are the Kids All Right?

Subscribe to our Newsletters

More by Charles Glass

December 10, 2023

The civil war may be over in Damascus, but the mood in the city is one of resignation.

March 23, 2023 issue

December 19, 2019 issue

Charles Glass is a former Chief Middle East Correspondent for ABC News and the author of They Fought Alone: The True Story of the Starr Brothers, British Secret Agents in Nazi-Occupied France . His most recent book is Soldiers Don’t Go Mad: A Story of Brotherhood, Poetry, and Mental Illness During the First World War . (December 2023)

June 10, 2021 issue

‘Animal Farm’: What Orwell Really Meant

July 11, 2013 issue

V. S. Pritchett, 1900–1997

April 24, 1997 issue

May 27, 2021 issue

Clocked In Still Starving

September 23, 2021 issue

Santiago de Compostela

February 1, 1963 issue

Bring Up the Bodies: An Inquisition

July 12, 2012 issue

Subscribe and save 50%!

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Don Quixote

By miguel de cervantes.

'Don Quixote' by Miguel de Cervantes tells the story of the eccentric Alonso Quixano, a man in his mid 50s, whose love for chivalric romantics leads him to assume the function of a knight-errant as he goes out on a noble quest to prove his valor to the world by reviving the culture of gallant horse-riding.

Article written by Victor Onuorah

Degree in Journalism from University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

The book is both tragic and comedic and follows the struggles of Alonso Quixano whose adventure goes to prove that sometimes setting and following your dreams, against society’s expectations, is the most worthwhile thing to do.

‘Spoiler-Free’ ‘ Don Quixote ‘ Summary

‘ Don Quixote ‘ is a classic written by Miguel de Cervantes documenting the adventure of Alonso, a fifty-year-old and native of La Mancha, a suburb of Spain. Influenced by the heroic deeds portrayed in countless chivalric books he has read, Alonso decides to become a hero himself and must set out to restore order to a world that, in his opinion, needs saving from the hands of evil entities and people who oppress the poor.

All set for his journey, he changes his name to the more suitable ‘ Don Quixote ‘, buys a horse, and selects a young farmer, Sancho Panza, as his squire, and a peasant young girl – who he calls Dulcinea – as his lady for the journey. He begins his journey and arrives at a public inn but he prefers to think of this place like a castle.

In the inn, he meets with all kinds of people including prostitutes and the innkeeper. He realizes it’s getting late and he must pass the night at the inn, but Alonso can’t seem to stay out of trouble for too long that by the end of the night, he fights a group of drivers before leaving by the morning.

As the journey continues, Alonso meets and rescues a young male applicant who appears to be getting some maltreatments from his lord. Later, our protagonist soon gets the beating of his life after he accosts a team of traders and questions them for saying unpleasant things to his lady, Dulcinea. He is taken home to recuperate but while he’s at it, his niece arranges with a group of locals and destroys his library and the books in it.

Alonso is told a wizard is responsible when he finally comes to consciousness. With eyes set on the quest, Alonso resumes his journey taking along Sancho, his squire. Things quickly get feisty and his valor is tested in an epic, but comical, battle against the windmills only he mistakes them for giants.

He soon encounters a lady marching with friars and seeks to rescue her. He and Sancho then enter another inn but brew trouble that leads to them leaving with injuries. Alonso loses lady Dulcinea and tries to get her back but is met with a stern test that threatens his knight-errantry. He must defeat the knight of the white moon or risk resignation from his chivalric adventures.

‘ Don Quixote ‘ Summary

Spoiler alert: important details of the novel are revealed below.

‘ Don Quixote ‘ begins with Alonso’s obsession with books of valor and chivalry. He keeps a stockpile of them and does nothing but reads them all day. Because of excessive exposure to the books, he loses his mind and decides he can become like one of the heroes in the books to save the helpless and rid the world of all impending evil.

He baptizes himself with a new name – ‘ Don Quixote de la Mancha ‘ – a locality in old Spain and gathers a team for his adventure which includes; his horse Rocinante, and a poor farm girl he renames Dulcinea, the love of his life.

Donning an old, worn-out knightly suit, ‘ Don Quixote ‘ begins his journey of saving the world and proving his knight-errantry. Their first real stop is an inn crowded with prostitutes and the innkeeper, but he prefers to see this place like a castle filled with ladies and lords. He decides there’s no better place so he organizes to be knighted here.

His first test as a knight comes too quickly as he rescues a young boy from his master’s brutality, but soon gets beaten up to stupor by a mob of traders who barely know the first thing about knight-errantry.

‘ Don Quixote ‘ is forced back home to recover, and while he lies unconscious, his friends and family – pioneered by his niece, a barber, and a priest – gather and burn all his books to ashes because they fear these objects may have been the reason for his madness which almost took his life.

When he finally awakens to the reality of losing his precious books, he is left without a choice but to blame it on the works of evil wizardry, which is known to be the mortal enemy of all knight errant such as himself. Undistracted from the goal of his quest, he recruits Sancho Panza as his squire and begins his second journey.

As they make progress in the sally, ‘ Don Quixote ‘ is faced with perhaps the most epochal battles in straight successions that, in fact, define his knightly adventure. First, wrestles with many giants which, in reality, are mere windmills.

Next, he’s up against a herd of enchanters who he pictures as ill-tempered muleteers, and then makes trouble with a passing congregation of friars who, in his mind, are good for nothing abductors holding an innocent young lady captive.