Special Educator Academy

Free resources, contingency maps for behavior problem-solving (freebie).

Sharing is caring!

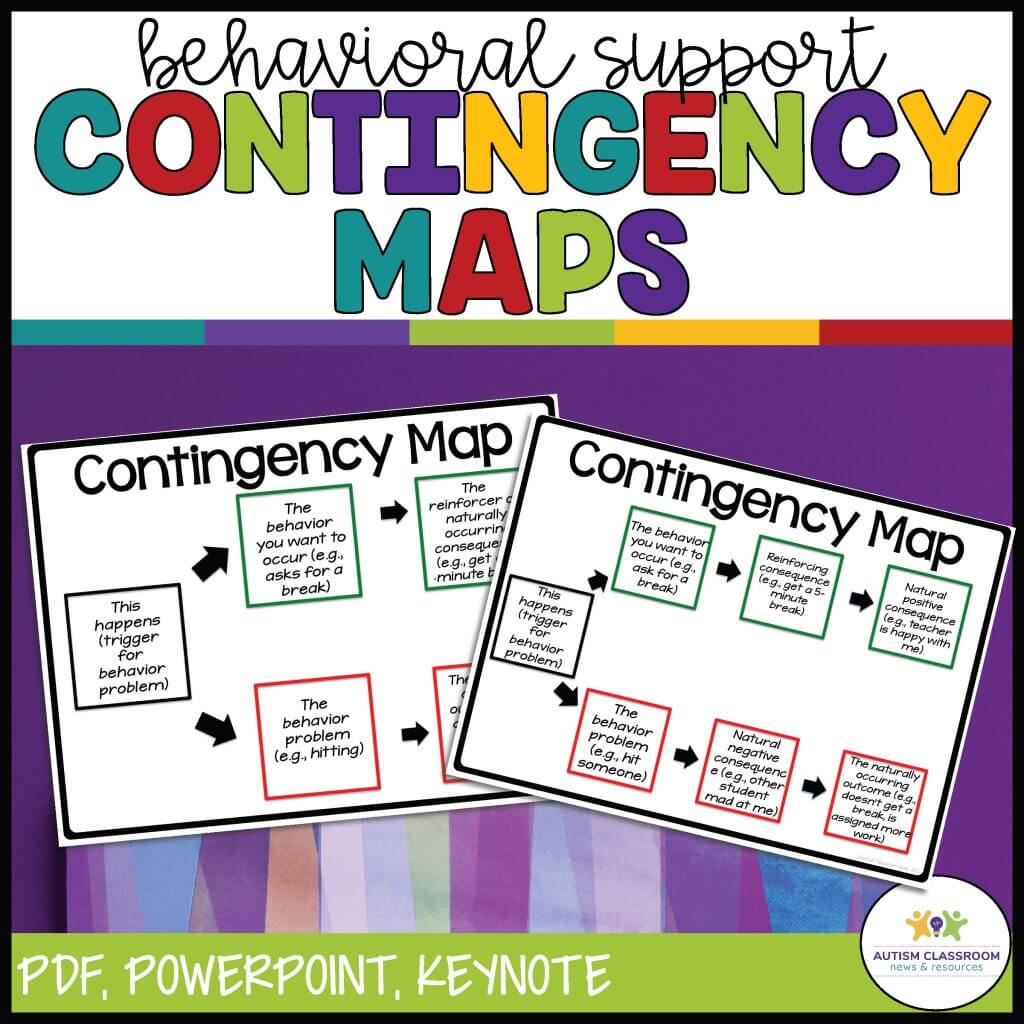

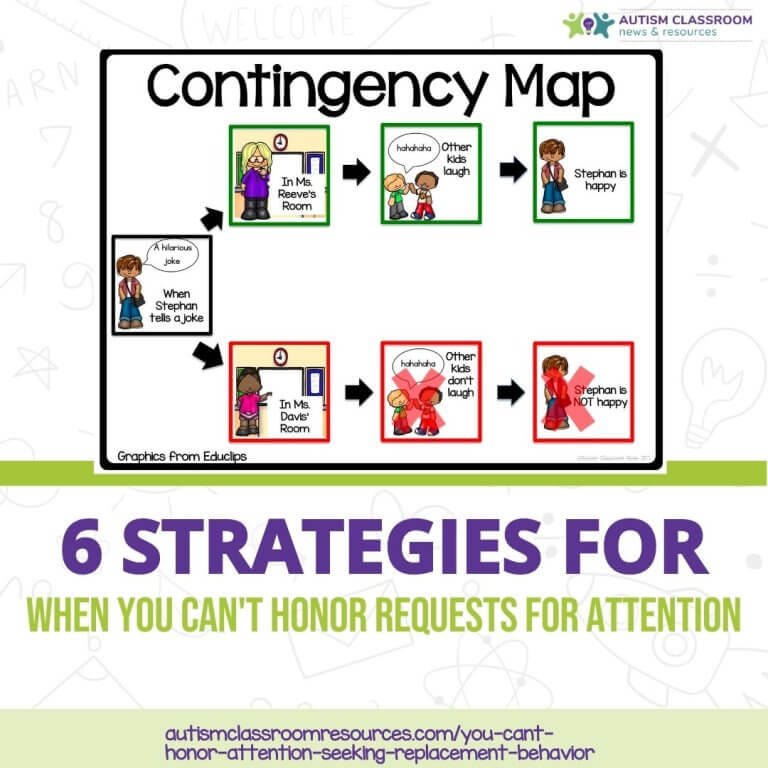

Contingency maps are a cognitive-behavioral method for helping an individual to understand the consequences of behavioral choices. They are particularly useful for teaching individuals to use functionally equivalent behaviors as alternatives to problem behavior.

They also are sometimes referred to as consequence maps and they are essentially graphic organizers for behavior. Michelle Garcia Winner uses similar strategies for Social Thinking that she calls Social Mapping .

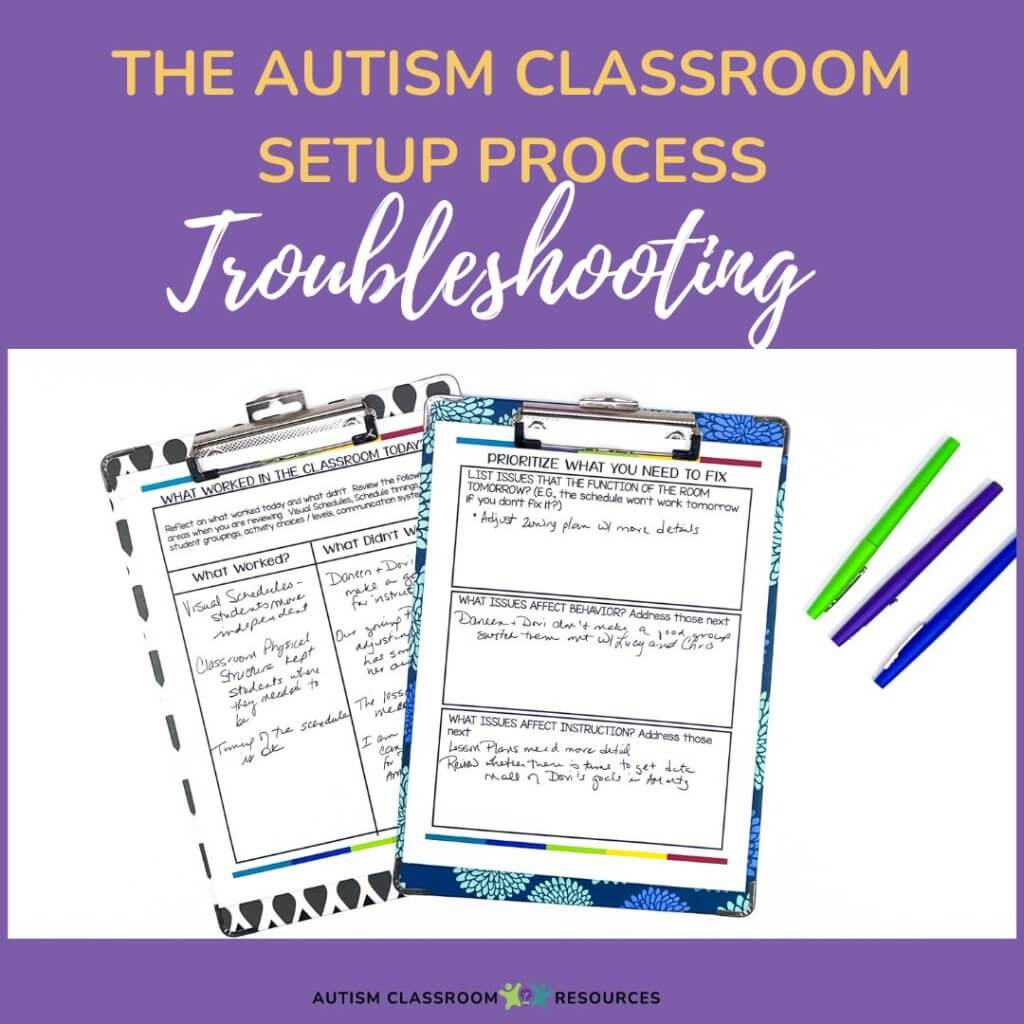

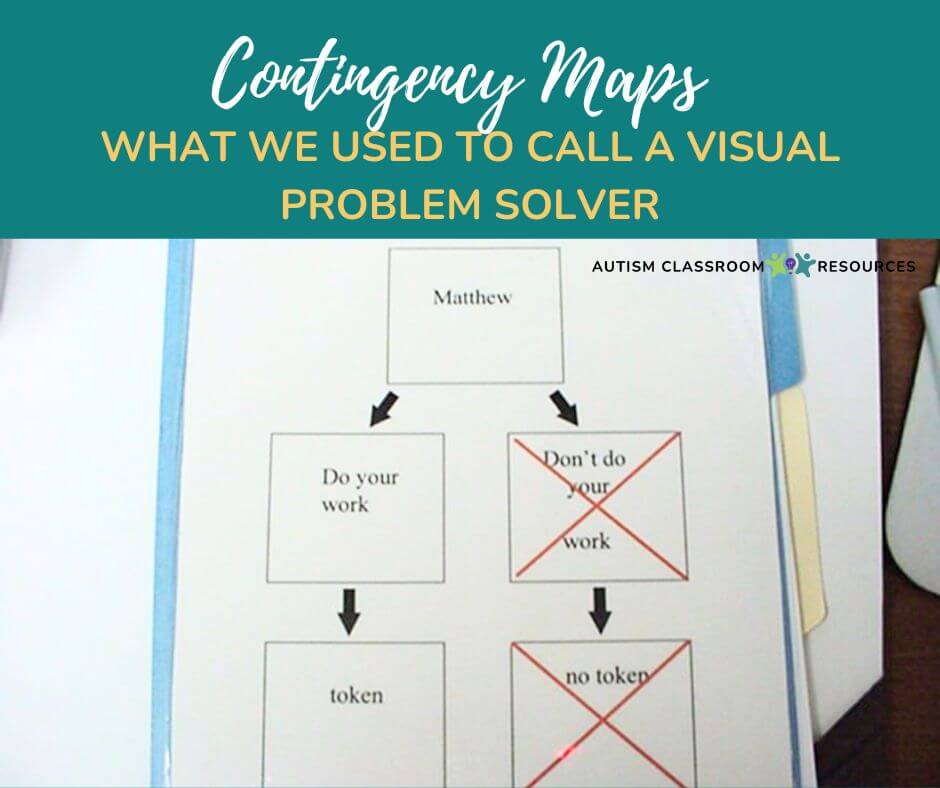

Contingency maps are a visual support that has been around in many forms for a number of years. The examples below come from a strategy we used to call visual problem solvers about 15 years ago.

How Do Contingency Maps Work?

Essentially, they are set up so that the student can see the consequence of the alternative behavior and the consequence (typically the naturally occurring consequence) of the negative behavior.

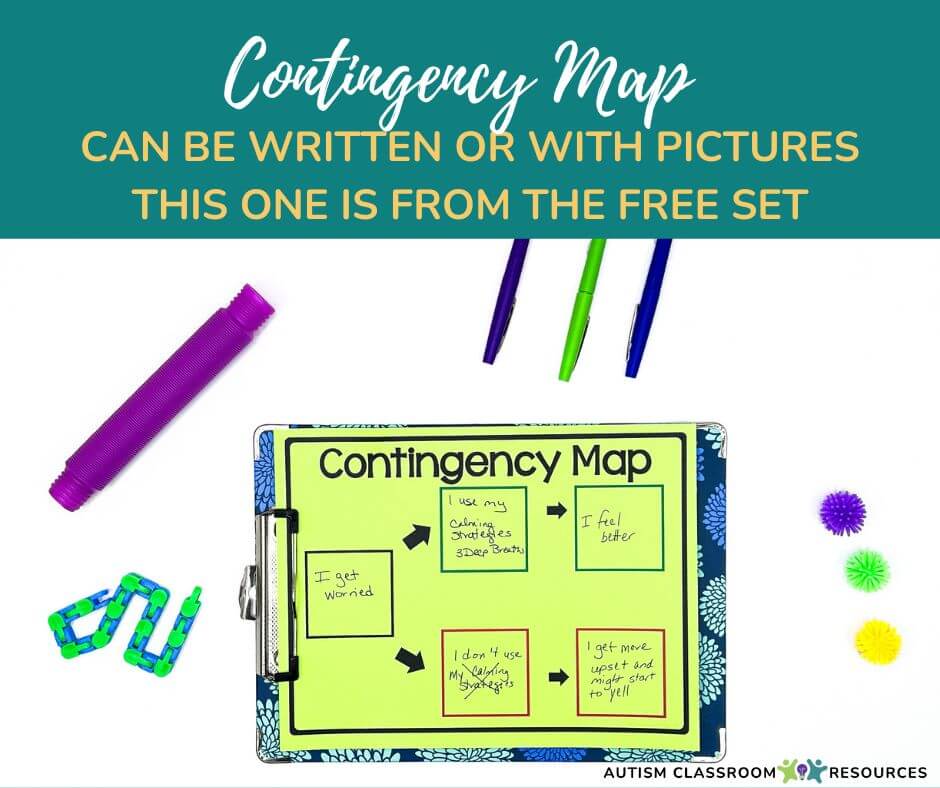

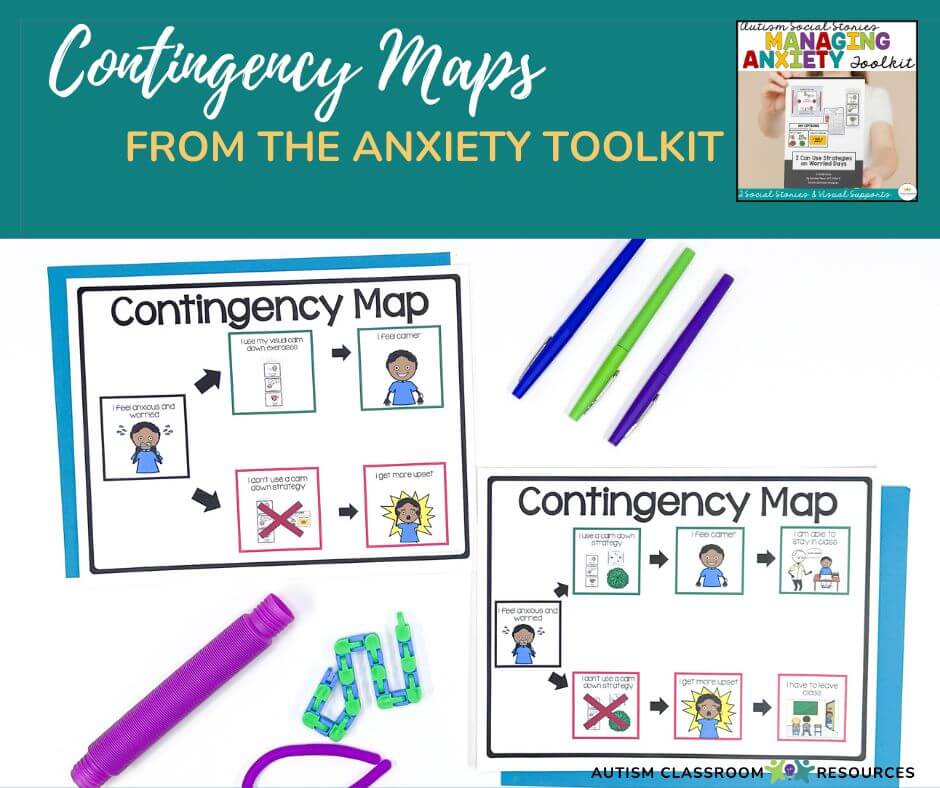

So in this example, If the student gets worried, and uses his calming strategies, the outcome is usually that he feels better. If he gets worreid and doesn’t use the calming strategies, the outcome is often that he starts to scream and become more upset.

Evidence Base and Effectiveness

As a visual support strategy there is evidence for the use of a variety of visual cues to increase independence and reduce problem behavior , and contingency maps fit in that body of literature. Specifically there have been two peer-reviewed articles looking at contingency maps as a way to reduce problem behavior.

Using a single-subject research design, Brown and Mirenda (2006) showed that the use of visual contingency maps were more effective than providing verbal contingencies to an individual for initiating and completing routine tasks [ click here to read the abstract ]. Brown and Mirenda used the contingency map as part of a functional equivalence training program (also known as functional communication training ). The contingency map showed the alternative behavior that was designed to replace the challenging behavior by serving the same function.

Tobin and Simpson (2012) have a great article in Teaching Exceptional Children describing data with another individual, using a single-subject design, that showed that a contingency map (they refer to it as a consequence map) was effective in reducing challenging behavior (decreased the frequency of disrobing) of a student. If you are a member of the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) –and I highly recommend it if you are a special education professional–you have access to the article. If not, the abstract is available here as well . This article also has a great description of how to implement contingency maps as well as examples.

Developing and Using Contingency Maps

Define the behavior.

Essentially to use a contingency, first you need to identify the specific behavior you want to change. You need to define it clearly and make sure that you and the student understand what it looks like. It also helps to take a baseline of the frequency of the behavior so you can determine if your contingency map works.

Determine the function

Next, you need to determine the function that the behavior serves. That is the topic of another post to cover, however, I have written about in the past and there are some tools available at this post.

The purpose of knowing the function of the behavior is to determine what appropriate behavior will serve the same function that you can use to replace it with. For instance, if your student hits to escape from work tasks, think about teaching him to ask for a break. Then this would be part of your graphic organizer.

Create the visual

Third, you need to create the contingency map, and that’s where I’ve got your back in several formats.

Below is a link to a freebie set of contingency maps along with some universal “no” signs to use with them. They are editable in PowerPoint and available in the Free Resources Library and in my TpT Store.

Essentially a contingency map makes the statement that

- when this happens (typically the identified trigger for problem behavior from your functional assessment),

- if the student engages in the appropriate alternative behavior (e.g., asking for a break),

- he or she will get a consequence he or she enjoys (i.e., a reinforcer).

- If he or she engages in the negative behavior then the positive consequence does not occur.

Sometimes the good choices are colored green and the poor choices are colored red, as in the examples below.

Steps for Using Contingency Maps

Contingency maps can be written or visual depending on the skills of your students. They are good visual cues to use for redirection since they show the consequence of behaviors.

In this example, the student’s behavior has been determined to be functioning to escape work situations. So, if he raises his hand and asks for a break, he gets a break to sit on the bean bag. If he doesn’t ask for a break and runs away, he does not get the bean bag.

After you have created the visual, it is not a magic bullet and it won’t work without teaching. You have to present the visual contingency and provide at least a brief explanation about how it works. Sometimes a social story or social narrative can be helpful for this. I would also practice the contingencies through a role play and make sure you have it available when it is needed to be used.

I would present it with as little verbal interaction as possible, just to lessen either the attention from the verbal explanation as a possible reinforcer for the problem behavior or to keep from escalating the behavior with verbal demands for some students.

Make sure to reinforce the alternative behavior with the promised contingency. It is important to make sure that the reinforcer is meaningful for the alternative behavior and reinforcing. Tools for finding reinforcers for students with ASD can be found in this post .

It also helps for the consequence to be naturally occurring to help the behavior maintain in the absence of the map over time. So for instance, if I ask my friends questions, they will want to talk to me, but if I hit my friends, they will not want to talk to me.

Assess and Fade

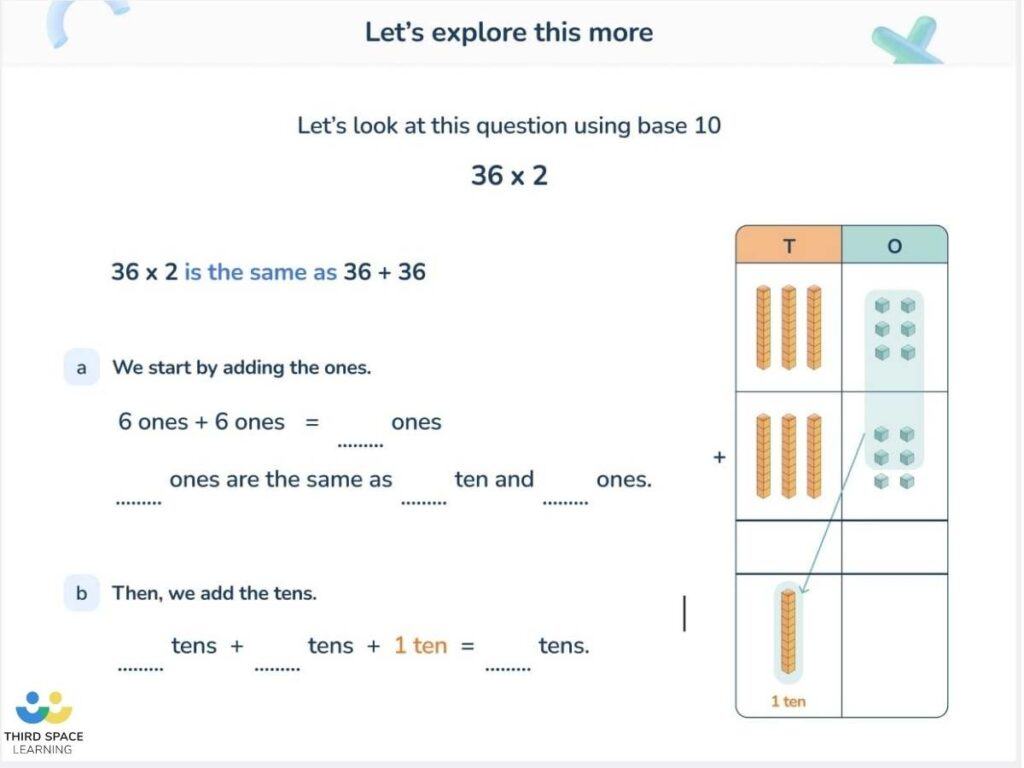

Take data on whether the frequency of the behavior is decreasing. If it is working, then over time you can fade the use of the visual map as the student becomes more independent and the negative behavior reduces in frequency.

Contingency Map Options

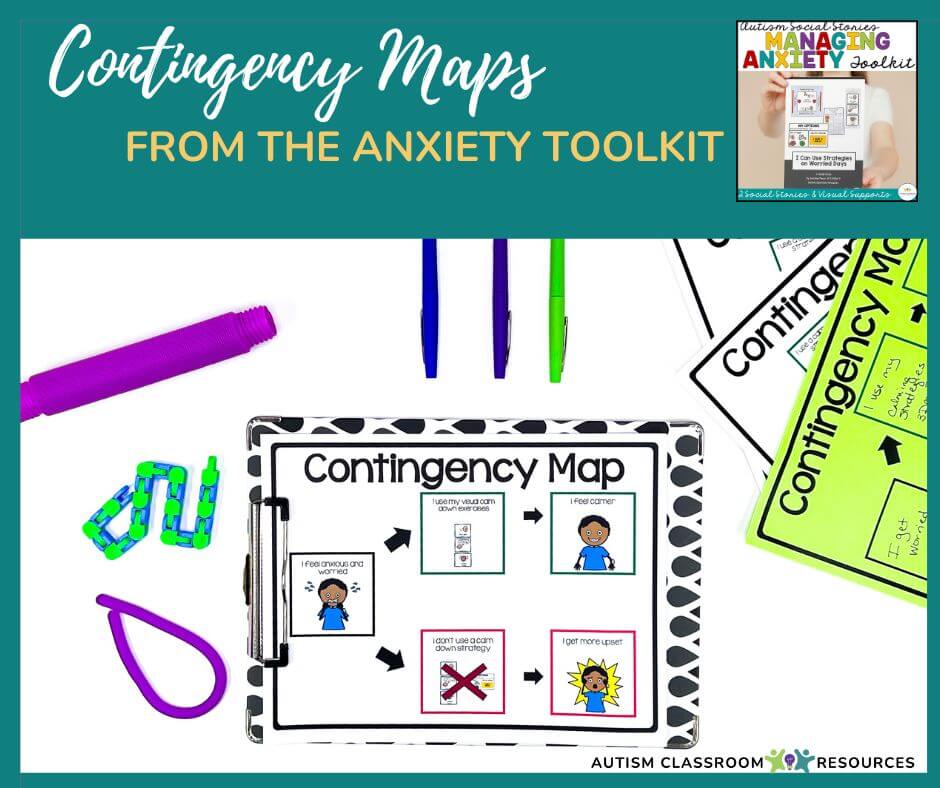

Contingency Maps are part of several of my Behavioral Toolkits. I’ve noted where each one came from in the pictures above. But they are available in my Making Mistakes Toolkit (obviously focused on handling making errors) and in my Managing Anxiety Toolkit . Click the pictures below to grab either of them.

Click on either of the pictures below to check out the toolkits in the store

I have also created some templates for you to use. Click here for the free version through my TPT store. They are editable in PowerPoint to add your own pictures(or upload to Google Slides) or Keynote to add your own pictures on to them. There are some pictures included in the pdf version as well that you could use with velcro.

Remember that if students are not great at comprehending what they have read, they may still need pictures. You could also laminate the chart and use a dry erase marker to make a contingency map on the fly.

Clearly, contingency maps are an invaluable tool for educators working with students who exhibit challenging behavior. By providing a visual representation of expectations and consequences, these maps empower both teachers and students to take proactive steps towards positive behavior management.So, why wait? Grab your contingency maps now and start creating a more conducive learning environment for your students!

- Read more about: Behavior Support , Visual Supports

You might also like...

Engaging Special Education Students: 3 Strategies for Student Engagement Techniques that Work!

How to Help Reduce Anxiety in Students Who Don’t Want to Stand Out

Visual Schedules for Autism Classrooms: 7 Reasons Why We Use and Love Them

6 Strategies to Help When You Can’t Honor Replacement Behaviors for Attention-Seeking Behaviors

Unlock unlimited access to our free resource library.

Welcome to an exclusive collection designed just for you!

Our library is packed with carefully curated printable resources and videos tailored to make your journey as a special educator or homeschooling family smoother and more productive.

Learn how WRTS and MBRTS are helping with COVID-19. Read here .

Read Our Blog

Social Skills Activities that Teach Kids Problem-Solving

September 22 , 2021.

Social skills activities are important for children of all abilities. With this in mind, We Rock the Spectrum’s Social Skills Blog Series aims to provide insight into activities and practical tips that help instill social skills in children. In this article, we focus on the importance of problem-solving skills in children and introduce five fun and educational activities that can enhance their problem-solving skill set.

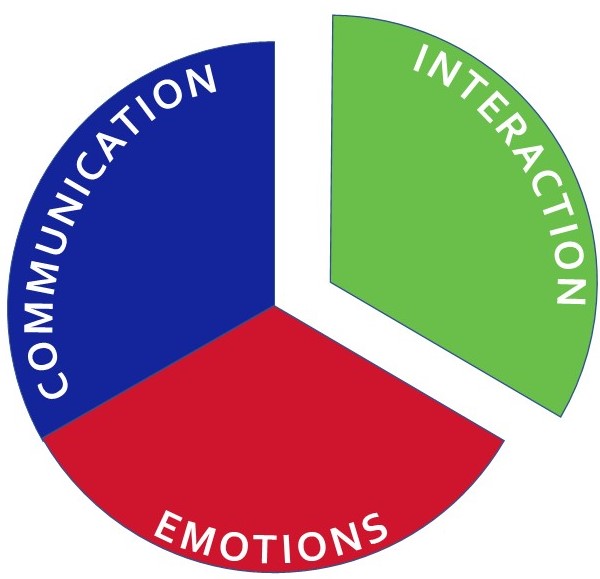

Autism Spectrum Disorder is a developmental disability in which children find it difficult to socialize and interact with others. Although autism comes in a variety of forms, many

kids have difficulty developing problem-solving skills. The combination of diminished communication, emotional, and self-regulation skills, all contribute to the child’s reduced skills. To be able to become well-rounded individuals, children of all abilities need to be given the opportunity and resources to learn proper problem-solving skills so that they can face challenges head-on later in life. With this in mind, we have put together a guide on the importance of problem-solving skills for both neurotypical children and children with autism.

Why is Problem-Solving Important?

Problem-solving deals with the ability to make decisions in tough or challenging situations. Children of all abilities need to learn how to properly handle each situation with problem-solving in order to become more independent and resilient. Having good problem-solving skills allow children to gain the patience and self-confidence they need to develop into capable individuals.

Problem-solving activities help children develop the skills they need to efficiently and effectively deal with complex issues and situations. In life, children will run into a variety of situations with differing contexts. Having the proper problem-solving skill set will allow children to learn how to handle every situation with ease. Once a child is able to effectively problem-solve, they will be able to better navigate their own personal problems and those of others as well. Additionally, a child will be able to identify a problem, develop different solutions, test different solutions, and analyze the results.

It is essential for parents or guardians to help boost problem-solving skills through a variety of sensory strategies. Here is a list of 5 fun activities that will teach children of all abilities how to build their problem-solving skills.

5 Activities that Teach Problem Solving

1. problems in a jar.

Problems in a Jar is a fun and creative way for children to explore different situations that can occur in the real world. This activity is designed to help kids generate solutions from one problem or circumstance. To begin, an adult will write one situation on a small sheet of paper, fold it, and place it in a jar. This continues until the jar is full. The child then picks a paper and reads off the problem. He/she must then come up with the best solution that solves the challenging scenario. This helps children think thoroughly about each possible solution independently.

2. Scavenger Hunt

Everyone loves a game of scavenger hunt! This group activity prompts children’s deduction skills based on clues and hints, which in turn, enhances their problem-solving skills. To start, divide children into groups of 2-3 and have them come up with a plan on which members look for which items. Children can also brainstorm together on where each item is located. This helps kids work together towards one goal while also nourishing their communication. Parents can also reward kids with small treats for every item they find on the scavenger hunt.

3. Impromptu Skits

Impromptu skits are a fun and engaging way for kids to think independently and with quick reactions. In this activity, children are given one situation wherein they have to reenact how the situation unfolds and how to solve the issue. This allows children to think about how to deal with each situation and see how it can be solved efficiently. After the skit, ask the children to explain their thought processes and correct them if there were any actions that were unnecessary. Children watching the skit will also be able to learn and understand how to best act in certain circumstances.

Puzzles are one of the best ways a child can stimulate their mind. Puzzles have multiple pieces that are all jumbled together. To solve a puzzle, children need to sort the pieces out and place them in their proper areas to be able to put the puzzle back together. This helps children develop memory recall and thought organization. To start off easy, children can work on puzzles with fewer pieces. Once they get the hang of it, they can move on to more difficult and complex puzzles to build their skill set.

5. Play With A Purpose TM

Having a space where your children will feel safe experimenting is vital to developing problem-solving skills quickly. We Rock the Spectrum’s Play With A Purpose™ stimulates and exercises a child’s sight, smell, taste, hearing, touch, vestibular system, and proprioception through positive physical, emotional, and social development. At We Rock the Spectrum, kids are able to play and interact together through arts and crafts, classes, our sensory equipment , and more to strengthen their problem-solving skills in an inclusive, sensory-safe environment.

Key Takeaways

Equipping all children with the proper problem-solving tools and resources at an early age will ensure they develop the skills they need to become versatile individuals. Children who are able to hone their problem-solving skills at their most important phase of development will be able to become more independent and know how to acclimate best to a multitude of situations in the long run. We Rock the Spectrum is a kids gym franchise that offers a wide range of fun and inclusive problem-solving activities through its specialized sensory equipment and Play With A Purpose™ program. Discover more about our mission by getting in touch with us today !

Autism Awareness

Autism resources, birthday parties, classes for kids, dream with dina, our partners, parent's corner, resources team, rockin' events, schools out program, social skills groups, uncategorized, we recommend, we rock care, we rock tarzana, why we rock, may (2023) 1, february (2023) 1, october (2022) 2, september (2022) 15, august (2022) 12, june (2022) 1, february (2022) 1, september (2021) 1, july (2021) 1, march (2021) 1, february (2021) 11, december (2020) 2, june (2020) 1, may (2020) 1, april (2020) 3, march (2020) 4, february (2020) 3, january (2020) 2, december (2019) 2, september (2019) 1, july (2019) 1, may (2019) 1, march (2019) 2, february (2019) 2, august (2018) 1, july (2018) 2, may (2018) 1, february (2018) 1, december (2017) 1, october (2017) 5, august (2017) 2, july (2017) 7, june (2017) 3, may (2017) 3, march (2017) 3, february (2017) 1, january (2017) 2, december (2016) 4, november (2016) 3, july (2016) 1, april (2016) 2, march (2016) 2, february (2016) 2, january (2016) 1, october (2015) 4, september (2015) 4, august (2015) 4, may (2015) 2, january (2015) 1, december (2014) 3, november (2014) 34, october (2014) 4.

News and Knowledge

Read the latest issue of the Oaracle

Teaching Autistic Students to Solve Math Word Problems

August 29, 2022

By: Jenny Root, Ph.D., BCBA

Categories: How To , Education

In the past three months, how many times have you had no choice but to use cash to make a purchase? Or tell time using an analog clock?

Although you have undoubtedly made purchases, it is likely you used a card or smart device, especially if the purchases were made online. To check the time, you probably glanced at a digital clock on a screen or even just asked Alexa, Google Home, or another artificial intelligence device.

While the functions of many activities of daily living, such as making purchases and telling time, have remained the same over time, how we accomplish these tasks has changed dramatically as technology has evolved.

Math instruction for autistic students has historically had a limited focus on “functional” skills in order to prepare them for independence in their adult lives. Yet in addition to mastering a series of discrete skills, autistic young adults need to be able to problem solve . This includes:

- Being aware of when there is a problem.

- Identifying a reasonable strategy.

- Monitoring their progress accurately.

- Adapting as necessary.

Word problem solving is one way to teach students how, when, and why to apply math skills in real-world situations they will encounter in a future we may not be able to envision yet.

These research-supported strategies can help teachers and parents teach autistic students to solve word problems using modified schema-based instruction (MSBI). MSBI is an evidence-based practice for teaching word problem solving.

Create a meaningful task.

Word problems need to depict a realistic and meaningful problem. This will help students better understand the “why” behind word problem solving and support generalization to everyday situations. You can begin planning by identifying high-interest, real-world contexts when the targeted math skills could be used, such as familiar community locations, family routines, or preferred activities. The quantities represented in the problem should be realistic for the situation. Use technology to build background knowledge for generalization by showing short videos or pictures, such as videos of people making purchases using a credit card or comparing rideshare costs between two apps.

Consider accessibility.

Both the materials and word problems themselves need to be accessible to students. The reading level, quantities represented, structure, and visual supports can all be adjusted to address barriers students may face. If independently reading the problem is a barrier, students can use technology to access text-to-speech or ask a skilled reader—a parent, peer, or teacher—to read it aloud to them. Quantities in the problem can be reduced to match a student’s numeracy skills (e.g., quantities under 10) or they can be provided with a calculator for efficiency.

Research has shown that autistic students can successfully fade this equation template once they become fluent in problem solving.

Focus on problem types, not keywords or operations.

Teaching word problem solving using MSBI may differ from your prior approaches to math instruction. Many teachers and parents teach operations sequentially, meaning once addition is mastered, they move on to subtraction, then multiplication, then division. But this developmental mindset can put unnecessary ceilings on student opportunity by having a “not ready for” mindset. Waiting for students to be “ready for” problem solving by overly focusing on their skill deficits will hold them back from meaningful, age-appropriate instruction.

MSBI also does not teach students to focus on keywords to identify operations, such as “more” meaning add and “left” meaning subtract. While this trick may initially work for some simple problems, it doesn’t help students conceptually understand the problem. Real-world problems won’t have keywords.

Instead of teaching by operation or focusing on keywords, research has shown when autistic students learn to identify and represent the problem by the schema (pattern of problem structure), they are able to independently solve, discriminate between, and generalize problems. There are two categories of schemas, or problem structures. Additive problems use addition and subtraction operations and include group/total, compare/difference, and change schemas. Multiplicative problems use multiplication and division and include equal group, multiplicative comparison, rate, and proportion. Here is a great resource that explains each schema .

Choose a problem-solving routine.

The three key components of schema instruction are teaching:

- The key features of each schema.

- A solution strategy for each schema.

- Important language and vocabulary related to the schema.

MSBI provides additional support as needed for working memory, language, reading level, and numeracy skills so that students are engaged, motivated, and able to “show what they know” while problem solving.

Problem-solving routines draw students’ attention to the decisions they need to make and actions they need to engage in to arrive at a solution. General attack strategies can be effective. These are two examples:

UPS Check

- Understand

- Check work

- Discover the problem type.

- Identify information in the problem to represent in the diagram.

- Solve the problem.

- Check the answer.

Students usually write these at the top of their paper or reference them on a poster or whiteboard in the classroom. Autistic students and those with more extensive support needs will likely need a more detailed and personalized routine that breaks down the mathematical decisions into more discrete behaviors.

When developing routines to meet student needs, analyze the decisions that need to be made and behaviors involved in solving problems. Routines should always begin with reading the problem or requesting that a problem be read aloud. At least when students are initially learning the routine, they should have individual copies to follow, either printed directly on worksheets or as a separate visual support. Judiciously pair visual supports with text to give support but not so much that they are just relying on matching instead of demonstrating mathematical understanding. The general curriculum access lab at Florida State University has example problem-solving routines from research with students with autism and other developmental disabilities on their website.

Support independence.

You must explicitly teach students to follow a problem-solving routine. Use think-alouds with clear and concise language while actively engaging students in the problem-solving process. Opportunities for guided practice are important for identifying points of strength and areas of misconception. A system of least prompts (starting with the prompt that provides the least amount of assistance) can be used when students are not independently correct:

- A generic verbal prompt: Read/point to step of the problem-solving routine.

- Direct verbal prompt: explain how to complete the step.

- A model-retest: Model completing step and ask student to repeat.

Self-monitoring and goal-setting can help facilitate independence in problem solving. Giving a space for students to check off steps as they are completed enables self-monitoring task completion to start as soon as they begin to solve the problem. The focus can shift to self-monitoring independence by having students check off steps completed “by myself” or “with help” as in the example below or self-monitoring duration by timing themselves.

Word problem solving is an important skill for all students, as it puts math concepts and procedures into a real-world context. In addition, self-determinatio n skills such as choice-making, self-monitoring, and goal-setting can be feasibly embedded to enhance effectiveness and efficiency. To prepare autistic students for independence in their futures, they need instruction focused on skills of the future, not the past.

Related Posts

Announcing 2024 Youth Art Contest Winners

Thank you to all the talented artists who participated in OAR’s 2024 Youth Art Contest. With entries from 125 artists across 24 states and…

April 3, 2024

Read More >

IACC Releases 2019-2020 Research Funding Report

In March, the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC) released its 2019-2020 IACC Autism Research Portfolio Analysis Report. The…

April 2, 2024

OAR Staffer Takes On A New Role

Long-time OAR staff member Rachel Luizza was recently promoted to director of development and marketing. When asked about her new job, she…

Our Newsletter

You’ll receive periodic updates and articles from OAR

Your cart is empty

Autism wall art.

Discover the essence of creativity and awareness in our Autism Wall Art...

Estimated total

Art That Speaks: Autism Decor 🎨 | Free Ship $49+

Trend Alert: Autism Tees! 👕 | Find Your Style!

Discover: Autism Jigsaw Puzzles 🧩 | Engage & Enjoy

Express with Autism Hats 🧢 | Style & Awareness

Write & Reflect: Autism Journals ✏️ | Shop Now

Autism and Puzzle Solving: Building Skills for Life

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects individuals in various ways. Puzzle solving has been found to be a beneficial activity for individuals with autism, as it helps develop cognitive skills, problem-solving abilities, and visual-spatial abilities. In this article, we will explore the importance of puzzle solving for individuals with autism, the types of puzzles that are suitable for them, and the numerous benefits of incorporating puzzle solving into their daily lives. We will also discuss strategies for introducing puzzle solving to individuals with autism and how to support them in this activity. Finally, we will share success stories of how puzzle solving has positively impacted individuals with autism, highlighting their improved cognitive abilities, enhanced problem-solving skills, increased social interaction, and greater sense of achievement.

Key Takeaways

- Puzzle solving can promote cognitive development and improve problem-solving skills in individuals with autism.

- It enhances visual-spatial abilities and helps develop attention and focus.

- Jigsaw puzzles, logic puzzles, pattern recognition puzzles, and maze puzzles are suitable for individuals with autism.

- Puzzle solving can improve fine motor skills and enhance social skills.

- Introducing puzzle solving in structured environments with visual supports and using reinforcement and rewards can be effective strategies.

Understanding Autism

What is Autism?

Autism, also known as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by social communication challenges and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior. It is important to understand that autism is not a disease or a result of bad parenting. Autism is a unique way of experiencing the world, and individuals with autism have diverse strengths and abilities.

- Autism is a spectrum disorder, meaning that it affects individuals differently and to varying degrees.

- Common signs of autism include difficulties in social interaction, communication, and engaging in repetitive behaviors.

- Autism is a lifelong condition, but with the right support and interventions, individuals with autism can lead fulfilling and meaningful lives.

Tip: Embrace the strengths and talents of individuals with autism, and create an inclusive and supportive environment that celebrates their unique abilities.

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by social communication challenges and restricted , repetitive patterns of behavior. It encompasses previous separate diagnoses such as Autistic disorder, Asperger Syndrome, and PDD-NOS. The DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing ASD include persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. Diagnosing ASD involves a complex process of assessment and observation, often requiring the expertise of multiple professionals.

Causes of Autism

The exact causes of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are still unknown. However, experts believe that a combination of genetic and environmental factors play a role in its development. Research suggests that certain genes, brain structure abnormalities, and chemical imbalances in the brain may contribute to the development of ASD. While the exact cause may be unclear, it is important to note that autism is not caused by vaccines or parenting styles.

Signs and Symptoms

Autism is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts. Individuals with autism may have difficulty understanding and responding to social cues, maintaining eye contact, and expressing or understanding emotions. They may also exhibit repetitive behaviors, insistence on routine, intense or focused interests, and sensory sensitivities . These characteristics must cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. It's important to note that autism is not solely due to developmental delay. Diagnostic criteria for autism include persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.

The Importance of Puzzle Solving

Cognitive Benefits of Puzzle Solving

Engaging in puzzle activities can enhance cognitive function, improve memory, and promote overall mental well-being. Puzzle solving stimulates critical thinking and problem-solving skills, allowing individuals with autism to exercise their cognitive abilities. It also provides a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction when a puzzle is successfully completed. Additionally, puzzle solving can help individuals with autism develop patience, perseverance, and attention to detail. By engaging in puzzle solving, individuals with autism can strengthen their cognitive skills and build a foundation for lifelong learning and success.

Improving Problem-Solving Skills

Developing problem-solving skills is crucial for individuals with autism. By engaging in puzzle solving activities, they can enhance their ability to think critically, analyze information, and find creative solutions. Puzzle solving provides a structured and engaging way to practice problem-solving skills, allowing individuals with autism to develop and strengthen this important cognitive ability. Additionally, puzzle solving can help individuals with autism improve their attention to detail, spatial reasoning, and logical thinking. It is a fun and effective way to promote cognitive development and boost confidence.

Enhancing Visual-Spatial Abilities

Developing strong visual-spatial abilities is crucial for individuals with autism. These skills involve understanding and interpreting visual information, such as shapes, patterns, and spatial relationships. Visual-spatial abilities play a significant role in problem-solving, decision-making, and navigation. They are essential for activities like assembling puzzles, reading maps, and recognizing objects in the environment.

To enhance visual-spatial abilities in individuals with autism, various strategies can be implemented:

- Engage in activities that involve visual-spatial processing, such as jigsaw puzzles and pattern recognition puzzles.

- Provide visual supports, such as visual cues and diagrams, to help individuals understand and interpret visual information.

- Create a structured environment that promotes organization and orderliness.

Tip : When introducing puzzles, start with simpler ones and gradually increase the complexity to match the individual's skill level.

Developing Attention and Focus

Developing attention and focus is crucial for individuals with autism. It allows them to stay engaged and complete tasks effectively. Here are some strategies to help improve attention and focus:

- Create a structured environment that minimizes distractions.

- Use visual supports, such as schedules and visual timers, to provide clear expectations.

- Break tasks into smaller, manageable steps.

- Provide positive reinforcement and rewards for staying focused.

Remember, developing attention and focus is a skill that can be cultivated over time with patience and support.

Types of Puzzles for Individuals with Autism

Jigsaw Puzzles

Jigsaw puzzles are a popular choice for individuals with autism. These puzzles provide a tactile and visual experience, allowing individuals to engage their fine motor skills and spatial awareness. The process of fitting the pieces together can be both challenging and rewarding, promoting problem-solving abilities and a sense of accomplishment. Jigsaw puzzles come in a variety of themes and difficulty levels, allowing individuals to choose puzzles that match their interests and abilities. Whether it's a puzzle featuring animals, landscapes, or characters from their favorite movies, jigsaw puzzles offer a fun and engaging activity for individuals with autism.

Logic Puzzles

Logic puzzles are a fantastic way to challenge the mind and develop critical thinking skills in individuals with autism. These puzzles require analytical thinking and problem-solving abilities , allowing individuals to exercise their cognitive abilities while having fun. By engaging in logic puzzles, individuals with autism can enhance their logical reasoning and decision-making skills . Additionally, logic puzzles provide a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction when solved, boosting self-esteem and confidence. Incorporating logic puzzles into daily life can be a stimulating and enjoyable activity for individuals with autism, promoting cognitive development and fostering a love for problem-solving.

Pattern Recognition Puzzles

Pattern recognition puzzles are a valuable tool for individuals with autism. These puzzles challenge the brain to identify and understand patterns, which can improve cognitive skills and problem-solving abilities. By engaging in pattern recognition puzzles, individuals with autism can enhance their visual-spatial abilities and develop attention and focus. These puzzles provide a structured and engaging activity that celebrates the unique strengths of autistic individuals. Whether it's finding the missing piece or deciphering a complex pattern, pattern recognition puzzles offer a fun and rewarding experience for individuals with autism.

Maze Puzzles

Maze puzzles are a captivating and stimulating activity for individuals with autism. These puzzles provide a unique opportunity to enhance problem-solving skills and promote cognitive development. By navigating through the twists and turns of a maze, individuals with autism can improve their visual-spatial abilities and develop attention and focus. Maze puzzles also offer a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction when successfully completed. Incorporating maze puzzles into daily life can be a fun and engaging way to build skills for individuals with autism.

Benefits of Puzzle Solving for Individuals with Autism

Promoting Cognitive Development

Promoting cognitive development is crucial for individuals with autism. By providing appropriate stimulation and support, we can help enhance their cognitive abilities. Here are some strategies to promote cognitive development:

- Create a structured environment that fosters learning and exploration.

- Choose puzzles that are challenging yet achievable.

- Provide visual supports such as visual schedules and visual cues.

- Use reinforcement and rewards to motivate and reinforce learning.

Remember, each individual with autism is unique, so it's important to tailor the strategies to their specific needs and abilities.

Improving Fine Motor Skills

Engaging in fine motor skills activities is essential for individuals with autism to enhance their motor coordination, hand dexterity, and overall independence. These activities can include tasks such as manipulating small objects, using scissors, and practicing handwriting. By regularly engaging in fine motor skills activities, individuals with autism can improve their ability to perform everyday tasks and gain a sense of accomplishment. It is important to provide a supportive and structured environment to facilitate their progress. Additionally, incorporating sensory elements, such as tactile materials or fidget toys, can further enhance their engagement and sensory integration.

Enhancing Social Skills

Improving social skills is a crucial aspect of supporting individuals with autism . People with autism often face challenges in social situations and forming meaningful relationships. ABA therapy incorporates social skills training to address these difficulties. Therapists employ various strategies to help individuals with autism initiate conversations, understand body language, and develop appropriate social behaviors. By enhancing social skills, individuals with autism can build stronger connections with their peers and feel more confident in social settings.

Boosting Self-Esteem and Confidence

Boosting self-esteem and confidence is crucial for individuals with autism. It reinforces their belief in their abilities and encourages them to undertake and persevere through challenges. Building self-esteem can be achieved through various strategies, such as:

- Providing positive reinforcement and praise for accomplishments

- Encouraging independence and autonomy

- Fostering a supportive and inclusive environment

- Celebrating individual strengths and achievements

By implementing these strategies, individuals with autism can develop a strong sense of self-worth and confidence, leading to greater overall well-being and success in various aspects of life.

Strategies for Introducing Puzzle Solving to Individuals with Autism

Creating a Structured Environment

For individuals with autism, creating a structured environment is crucial. It promotes a sense of stability and reduces anxiety . By establishing routines and utilizing visual supports, individuals with autism can navigate their daily lives with more ease and confidence. A structured environment provides a predictable and organized space that helps individuals with autism feel secure and supported. It allows them to focus on tasks and activities, improving their attention and concentration. Creating a structured environment is an essential step in introducing puzzle solving to individuals with autism.

Choosing Appropriate Puzzles

When selecting puzzles for individuals with autism, it's important to consider their unique needs and abilities. Tailor the difficulty level to match their cognitive skills, ensuring that the puzzle is challenging but not overwhelming. Choose puzzles with clear visual cues and minimal distractions to help them stay focused. Additionally, select puzzles that align with their interests to keep them engaged and motivated. Remember, the goal is to provide a positive and enjoyable puzzle-solving experience that promotes skill development and boosts self-esteem.

Providing Visual Supports

Visual supports are essential for individuals with autism, as they provide structure and predictability. Consistency with rules is key, and visual schedules, reminders, or written rules can help them understand expectations. These supports can be tailored to the individual's needs and can be created in collaboration with their ABA therapist . By incorporating visual demonstrations and cues, individuals with autism can better navigate their daily routines and tasks. Remember, every individual is unique, so it's important to find strategies that work best for them.

Using Reinforcement and Rewards

Utilize positive reinforcement by providing rewards, praise, or privileges when your teen displays desired behaviors. This encourages them to repeat those behaviors in the future. Operant extinction can be implemented by withholding attention or rewards for unwanted behaviors, decreasing their occurrence over time. Offer prompts to help your teen learn and perform desired behaviors, using verbal, visual, or physical cues. Gradually fade the prompts as they become more independent. Parental involvement is crucial for reinforcing skills and promoting progress in ABA therapy at home.

Incorporating Puzzle Solving into Daily Life

Puzzle Solving as a Leisure Activity

Puzzle solving is not just a leisure activity; it's a gateway to relaxation and mindfulness . As we immerse ourselves in the process of solving puzzles, we can experience a sense of calm and focus. It's a chance to escape from the busyness of everyday life and engage in a soothing and meditative activity. Whether it's a jigsaw puzzle, a logic puzzle, or a pattern recognition puzzle, the act of solving puzzles can provide a much-needed break and a moment of tranquility.

Puzzle Solving in Educational Settings

Incorporating puzzle solving into educational settings can have a profound impact on individuals with autism. Puzzle solving provides a unique opportunity for cognitive development and problem-solving skills enhancement. It helps individuals improve their visual-spatial abilities and develop attention and focus . Here are some strategies for incorporating puzzle solving in educational settings:

- Create a structured environment that promotes engagement and concentration.

- Choose puzzles that are appropriate for the individual's skill level.

- Provide visual supports, such as visual cues or step-by-step instructions.

- Use reinforcement and rewards to motivate and encourage participation.

By integrating puzzle solving into educational settings, we can create an inclusive and stimulating learning environment for individuals with autism.

Puzzle Solving in Therapy

Therapy is an essential component of autism treatment, focusing on improving behavior and social skills. Positive reinforcement is used to encourage desired behaviors and reduce unwanted ones. Speech and Language Therapy helps improve communication skills, while Occupational Therapy focuses on daily living skills. Behavioral Therapy uses positive reinforcement to improve behavior and social skills. Puzzle solving can be incorporated into therapy sessions to enhance problem-solving abilities and promote cognitive development. It provides a structured and engaging activity that celebrates autistic identities and encourages skill building.

Puzzle Solving for Skill Building

Puzzle solving is more than just a leisure activity for individuals with autism. It is a powerful tool for skill building and personal growth. By engaging in puzzles, individuals with autism can develop important cognitive abilities, such as problem-solving skills and attention to detail. Puzzle solving also helps improve fine motor skills and enhances visual-spatial abilities. It provides a structured and engaging way to build skills that can be applied in various aspects of life.

Supporting Individuals with Autism in Puzzle Solving

Understanding Individual Needs

When it comes to individuals with autism, understanding their unique needs is crucial. Each person on the autism spectrum is different, and their support should be tailored to their specific requirements. By recognizing and addressing these needs, we can enhance their skills and promote their growth and development. Diagnosis of Autism and Intellectual Disability involves a complex process of assessment and observation, often requiring the expertise of multiple professionals. It's important to increase awareness and knowledge of these conditions to improve outcomes for individuals affected by them. Additionally, individuals with both autism and intellectual disability may require a comprehensive and multi-faceted approach to support their unique needs.

Providing Guidance and Assistance

When supporting individuals with autism in puzzle solving, it is crucial to provide guidance and assistance tailored to their unique needs. Here are some strategies to consider:

- Use prompts: Guide individuals with verbal, visual, or physical cues to help them find the correct response.

- Model tasks: Show them how to perform tasks, engage in social interactions, or follow routines through visual demonstrations.

- Establish clear rules: Create visual schedules, reminders, or written rules to provide structure and predictability.

Remember, consistency and individualized support are key to fostering success in puzzle solving for individuals with autism.

Encouraging Independence

Encouraging independence is crucial for individuals with autism to develop essential life skills. Here are some strategies to promote independence:

Provide clear and consistent rules at home, using visual schedules and reminders to help them understand expectations.

Gradually fade prompts and cues as they become more independent in executing tasks and behaviors.

Model tasks and social interactions to show them how to perform them.

Reinforce positive actions with praise and incentives to encourage repetition.

Give opportunities for learning new skills, tailored specifically for teenagers.

Remember, consistency and support are key in fostering independence and empowering individuals with autism to thrive.

Adapting Puzzles for Different Abilities

When it comes to puzzle solving, it's important to consider the diverse abilities of individuals with autism. Adapting puzzles can make them more accessible and enjoyable for everyone. Here are some strategies to ensure inclusivity:

- Provide puzzle options with varying difficulty levels

- Use visual supports, such as color-coding or picture cues

- Break down complex puzzles into smaller, manageable parts

- Modify puzzle pieces for easier manipulation

Remember, the goal is to create a positive and empowering puzzle-solving experience for individuals with autism.

Success Stories: How Puzzle Solving has Impacted Individuals with Autism

Improved Cognitive Abilities

Enhancing cognitive abilities is a key benefit of puzzle solving for individuals with autism. Cognitive abilities refer to the mental processes involved in acquiring knowledge, understanding, and problem-solving. By engaging in puzzle solving, individuals with autism can improve their critical thinking and reasoning skills , as well as memory and attention . Puzzle solving also stimulates visual-spatial processing , which is important for tasks such as reading maps or solving complex puzzles. Additionally, puzzle solving can enhance creativity and flexible thinking , allowing individuals with autism to approach challenges from different perspectives.

Enhanced Problem-Solving Skills

Developing problem-solving skills is a crucial benefit of puzzle solving for individuals with autism. Problem-solving is an essential skill that empowers individuals to overcome challenges and find creative solutions. By engaging in puzzle solving, individuals with autism can enhance their ability to think critically, analyze information, and make decisions. This skill is not only valuable in daily life but also in educational and professional settings. Puzzle solving provides a fun and engaging way for individuals with autism to develop and strengthen their problem-solving skills.

Increased Social Interaction

Improving social skills is a crucial aspect of puzzle solving for individuals with autism. Puzzle solving activities provide opportunities for social interaction and collaboration, allowing individuals to practice communication, turn-taking, and teamwork. Engaging in puzzles with others can help individuals with autism develop and strengthen their social skills, fostering meaningful connections and relationships. Through puzzle solving, individuals with autism can enhance their ability to initiate conversations, understand non-verbal cues, and engage in cooperative play. By promoting social interaction, puzzle solving empowers individuals with autism to integrate into society, establish meaningful relationships, and gain independence.

Greater Sense of Achievement

Individuals with autism who engage in puzzle solving often experience a greater sense of achievement. Completing a puzzle, whether it's a jigsaw puzzle, logic puzzle, pattern recognition puzzle, or maze puzzle, provides a tangible result that can boost self-esteem and confidence. The feeling of accomplishment that comes from solving a puzzle can be especially empowering for individuals with autism, as it showcases their problem-solving abilities and showcases their unique strengths. Puzzle solving allows individuals with autism to showcase their intelligence and creativity, and it can be a source of pride and joy. It's a reminder that they are capable of overcoming challenges and achieving success.

Success Stories: How Puzzle Solving has Impacted Individuals with Autism. Puzzle solving has been proven to have a positive impact on individuals with autism. It helps improve cognitive skills, problem-solving abilities , and social interaction. Many individuals with autism have found solace and joy in solving puzzles, as it provides a sense of accomplishment and boosts self-esteem. At Autism Store, we understand the importance of puzzle solving for individuals with autism. That's why we offer a wide range of autism-themed puzzles, including jigsaw puzzles, 3D puzzles, and more. Visit our website to explore our collection and find the perfect puzzle for yourself or your loved ones. Join the puzzle-solving community and experience the benefits it brings to individuals with autism.

In conclusion, the journey of understanding and appreciating individual differences and strengths is crucial in supporting individuals with autism. Embracing these differences can lead to remarkable growth and connection, enabling individuals to build essential life skills and contribute meaningfully to society. It is imperative to focus on remediating all the things that are not going well, and instead, put autistic students in jobs that play to their strengths. This approach fosters independence, social integration, and personal growth, ultimately leading to a more inclusive and supportive environment for individuals with autism.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is autism.

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects communication, social interaction, and behavior.

What are autism spectrum disorders?

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a range of conditions characterized by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviors, and communication difficulties.

What are the causes of autism?

The exact causes of autism are not known, but it is believed to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

What are the signs and symptoms of autism?

Signs and symptoms of autism can vary, but common ones include difficulties with social interaction, repetitive behaviors, and challenges with communication.

What are the cognitive benefits of puzzle solving?

Puzzle solving can improve cognitive skills such as problem-solving, attention, and visual-spatial abilities.

How does puzzle solving improve problem-solving skills?

Puzzle solving requires individuals to think critically, analyze patterns, and find solutions, which enhances problem-solving skills.

What types of puzzles are suitable for individuals with autism?

Suitable puzzles for individuals with autism include jigsaw puzzles, logic puzzles, pattern recognition puzzles, and maze puzzles.

How does puzzle solving enhance social skills?

Puzzle solving can promote social interaction, cooperation, and communication when done in a group setting or with a partner.

Your Voice Matters

More autism resources & education, benefits of sensory-friendly play for autism.

The concept of sensory-friendly play is transformative for children with autism, offering a bridge to new forms of learning and interaction. By tailoring play environments to their unique sensory needs,...

Sensory Integration and Behavioral Improvements

Sensory Integration and Behavioral Improvements is a comprehensive exploration into how sensory integration therapy impacts various aspects of children's development, particularly those with special needs. It delves into the theory...

Legal Rights for Autism in the Workplace

The article 'Legal Rights for Autism in the Workplace' explores the intersection of neurodiversity and employment law, focusing on the legal protections and accommodations available for autistic individuals in the...

Home / Autism Blog / Autism and Puzzle Solving: Building Skills for Life

Explore our Autism Store

Autism home decor.

Transform your living space with our Autism Home Decor Collection at Heyasd.com,...

Autism Apparel

Elevate your style with our Autism Apparel Collection at Heyasd.com, a diverse...

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.

Can we help you find something?

Contact us today if you have any questions or suggestions. We will work around the clock to assist you!

Confirmation

Contact us 24/7.

- Create an account

Engaging Work Tasks at Your Fingertips

Search through thousands of quality teaching materials that will help your students reach their learning goals.

View All or select a category.

- Australia/UK

- Digital No-Print Activities

- Early Childhood

- Fine Motor Skills

- Gross Motor Skills

- Holiday/Seasonal

- IEP Goal Skill Builder Packets

- Independent Functioning

- Language/Speech

- Learning Bags

- Meet My Teacher

- Occupational Therapy

- Physical Education

- PRINT and GO Resources

- Social Skills

- Social Studies

- Task Box Filler Activities

- Teacher Resources

- Visual Schedules

Select a Domain

Select an IEP domain and you'll find thousands of free IEP goals, along with teaching materials to help your students master each goal.

- Academic - Math

- Academic - Reading

- Academic - Writing

- Communication & Language

- Social/Emotional

PRINT and GO Resource Sale

All of our PRINT and GO Resources are 20% off to help your students practice IEP goals and academic skills at home.

Add PRINT and GO Resources to your cart and apply coupon code PRINT to see the discount. Limited time offer.

- Problem Solving

- Free IEP Goal Bank

Our Mission

Our mission is to enhance special needs classrooms around the globe with engaging "hands-on" learning materials and to provide effective resources for Special Education teachers and therapists to share with their students.

Follow us on Facebook!

When you sign up for an account, you may choose to receive our newsletter with educational tips and tricks, as well as the occasional special freebie! Sign me up!

Information

- About Us: What's Our Story?

- Purchase Orders

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Returns & Exchanges

Customer Service

- Education Team Members

- Gift Vouchers

- Order History

- My Teacher's Wish List

Autism Educators, Inc. © 2012-2024

- Current Issue

- Back Issues

- Article Topics

- ASN Events Calendar

- 2023 Leadership Awards Reception

- Editorial Calendar

- Submit an Article

- Sign Up For E-Newsletter

Social Problem Solving: Best Practices for Youth with ASD

- By: Michael Selbst, PhD, BCBA-D Steven B. Gordon, PhD, ABPP Behavior Therapy Associates

- July 1st, 2014

- assessment , problem solving , social information processing , social skills

- 8086 0

Joey, age 9, has been diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and due to his high functioning has been mainstreamed into a fourth grade classroom with a shadow. His […]

Joey, age 9, has been diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and due to his high functioning has been mainstreamed into a fourth grade classroom with a shadow. His challenging behaviors typically center on his peer interactions in spite of adequate academic performance. When in a group situation he becomes very argumentative when his ideas are not used, becomes very bossy on the playground, and has run out of the classroom when things do not go his way. Megan, age 14, has also been diagnosed with ASD. She isolates herself from her peers and rarely initiates or responds to greetings. Conversations are almost nonexistent unless they are focused on her favorite topics of anime or fashion.

Children with ASD described as above typically have significant social skills impairments and often require direct instruction in order to address these deficits. They often have difficulty in many of the following areas: sharing, handling frustration, controlling their temper, ending arguments calmly, responding to teasing, making/keeping friends, complying with requests. Strong social skills contribute to the initiation and maintenance of positive relationships with others and as a result contribute to peer acceptance. Social skills impairments, on the other hand, contribute to peer rejection. The ability to get along with peers, therefore, is as important to self-esteem as the ability to meet with academic success in the classroom. This article will review the domain of social skills, the assessment of social skills, the importance of social problem-solving and a social skills curriculum which incorporates evidence-based practices to address this very important area.

Social information processing (SIP) is a widely-studied framework for understanding why some children have difficulty getting along with peers. A particularly well-known SIP model developed by Crick and Dodge (1994) describes six stages of information processing that children cycle through when evaluating a particular social situation: encoding (attending to and encoding the relevant cues), interpreting (making a judgment about what is going on), clarifying goals (deciding what their goal is in the particular situation), generating responses (identifying different behavioral strategies for attaining the decided upon goal), deciding on the response (evaluating the likelihood that each potential strategy will help reach their goal and choosing which strategy to implement), and performing the response (doing the chosen response). It is assumed that the steps outlined above operate in real time and frequently outside of conscious awareness. Numerous studies have shown that unpopular children have deficits at multiple stages of the SIP model. For example, they frequently attend to fewer social cues before deciding on peers’ intent, are more likely to assume that peers have acted towards them with hostile intent, are less likely to adopt pro-social goals, are more likely to access aggressive strategies for handling potential conflicts, evaluate aggressive responses more favorably, and are less skillful at enacting assertive and prosocial strategies.

Deficits in social skills are one of the defining characteristics of children with ASD. These impairments manifest in making and keeping friends, communicating feelings appropriately, demonstrating self-control, controlling emotions, solving social problems, managing anger, and generalizing learned social skills across settings. Elliott and Gresham (1991) indicated that social skills are primarily acquired through learning (observation, modeling, rehearsal, & feedback); comprise specific, discrete verbal and nonverbal behaviors; entail both effective and appropriate initiations and responses; maximize social reinforcement; are influenced by characteristics of environment; and that deficits/excesses in social performance can be specified and targeted for intervention. Social skills can be conceptualized as a narrow, discrete response (i.e., initiating a greeting) or as a broader set of skills associated with social problem solving. The former approach results in the generation of an endless list of discrete skills that are assessed for their presence/absence and are then targeted for instruction. Although this approach has an intuitive appeal and is easily understood, the child can easily become dependent on the teacher/parent in order to learn each skill.

An alternative approach focuses on teaching a problem solving model that the child is able to apply independently. Rather than focusing on teaching a specific behavioral skill, the focus is on teaching a social problem solving model that the learner would be able to use as a “tool box.” The well-used saying “give a person a fish and she eats for a day but teach her to fish and she eats for a lifetime” is particularly relevant. The social problem solving approach offers the promise of helping the child with ASD to become a better problem solver, thereby promoting greater independence in social situations and throughout life.

After many years of conducting social skills training using the specific skill approach, the authors have developed a model of social problem solving that uses the easily learned acronym of POWER. The steps of POWER-Solving® include:

P ut problem into words

O bserve feelings

W ork out your goal

E xplore solutions

R eview plan

Each of the five steps of POWER-Solving® has been previously identified as reliably distinguishing between children with emotional/behavioral disorders and psychologically well-adjusted individuals. The ability to “Put problem into words” is critical in order to start the problem solving process. Children with ASD often have difficulties finding the words to identify a problem. Thus, the first step in this approach involves direct training in the use of the rubric “I was… and then…” Upon entering the classroom and finding a peer in his seat Joey immediately pushed the peer in an attempt to get him out of his seat. Through the use of POWER-Solving® Joey was taught to articulate “I was walking into the classroom and then I saw that Billy was in my seat.”

The second step of “Observe feelings” was addressed by helping Joey develop a feelings vocabulary (e.g., angry, frustrated, scared, sad) as well as measuring the intensity of these emotions using a scale from one to ten, with a one being “very weak” and a ten being “very strong.” Photographs and drawings were used extensively to capitalize on his strong visual skills.

The third step of POWER-Solving®, “Work out your goal?” involves identifying the goal and the motivation to reach the chosen goal. This critical step sets the stage for what follows. The goal must be specific and measurable, consistent with Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) principles. Joey was able to identify that his goal consisted of two parts. First, he wanted to get Billy out of his seat and second, he wanted him to still be his friend. He reported that his desire to reach this goal was a nine on the ten-point scale.

The fourth step of POWER-Solving® involves “Explore solutions.” Socially skilled individuals are able to generate a range of effective solutions but those with impairments are more limited and often apply the same rigid solution over and over again in spite of repeated ineffectiveness. Joey was taught to “brainstorm,” which involves generating as many solutions as possible that might reach the stated goal, provided the solution is safe, fair, and effective. Joey was able to identify that approaching Billy and saying “Excuse me but I need to sit in my seat now” would help him to accomplish his goal(s). Behavioral rehearsal, combined with coaching and feedback, helped Joey to become fluent in applying this solution.

The final step of POWER-Solving®, “Review plan,” involved Joey reviewing his plan to use this skill the next time the situation presented and to reward himself by saying “I am proud of myself for figuring this out.”

POWER-Solving® has been applied successfully in multiple settings such as the classroom, a summer treatment program, clinical settings and home environments. The curriculum is systematic and relies heavily on visual cues and supports. Children are taught how to problem-solve first using their “toolbox” (i.e., the five steps of POWER-Solving®). The children are presented with specific unit lessons on each of the five steps of POWER-Solving®. All children have an opportunity to practice each step of POWER-Solving®. After learning each step of POWER, the children have acquired a “toolbox” which they can begin to apply to social situations.

When teaching social skills, it is important to coach the children through behavioral rehearsal activities to promote skill acquisition, performance, generalization and fluency. Additionally, daily activities reinforce these skills, some of which include designing their own feelings thermometer, developing novel products via group collaboration, and developing a skit to teach a specific skill.

To increase students’ performance of the desired skills, use of a token economy may be helpful, whereby points are earned during the day for displaying appropriate behavior, demonstrating a predetermined individualized social behavioral objective and for using the POWER-Solving® steps. At the end of every day, points could be exchanged for a reward. In addition to the direct instructional format, incidental teaching should be used in anticipation of a challenging situation as well as a consequence for failure to use the steps when confronted with a specific problem. An experienced social skills coach, generalization strategies, and a systematic plan to teach and reinforce skills are critical for success.

Please feel free to contact us at Behavior Therapy Associates for more information about best practices for social skills training, as well as information regarding the POWER-Solving curriculum. We can be reached at 732-873-1212, via email [email protected] or on website at www.BehaviorTherapyAssociates.com .

Crick, N.R., & Dodge, K.A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin , 115, 74–101.

Elliott, S.T. & Gresham, F. M. (1991). Social skills intervention guide: Practical strategies for social skills training . Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Related Articles

Using media as an effective tool to teach social skills to adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders.

Media is a powerful educational tool for adolescents and young adults in general; however, for individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) it provides a unique opportunity to learn social skills. […]

The Importance of Socialization for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are defined by three main components/deficits. These are deficits in Communication (receptive/expressive speech and language delay), Behaviors (aka self-stimulatory behaviors or stimming) and Socialization. Communication: these […]

Teaching Social Skills – A Key to Success

As young adults with autism transition from high school to college, work or independent living, they need to have good social skills in order to make friends, engage colleagues and […]

Places for Persons with Asperger’s to Meet People

There are many places where persons with Asperger’s can meet people, but too often they don’t know where they can comfortably and satisfactorily do this. Bars, cocktail parties, and other […]

I Finally Feel Like I Belong

I was one of the unpopular kids. I was never invited to birthday parties or sleepovers. I had no friends, and no one wanted to hang out with me. I […]

Have a Question?

Have a comment.

You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Individuals, Families, and Service Providers

View our extensive library of over 1,500 articles for vital autism education, information, support, advocacy, and quality resources

Reach an Engaged Autism Readership Over the past year, the ASN website has had 550,000 pageviews and 400,000 unique readers. ASN has over 55,000 social media followers

View the Current Issue

ASN Winter 2024 Issue "Understanding and Accommodating Varying Sensory Profiles"

Social Skills Activities for Children with Autism

AutismTeachingStrategies.com

Interaction

* Cooperation & engagement with a partner

Draw a Pizza Two-Person Activity

Draw a Cookie Two-Person Activity

Paper Fortune Teller for Playing & Hanging Out Skills

*Cooperation & engagement with multiple individuals

Friendship Growing Cards for Friendship Social Skills

Puzzle Piece Drawing Shapes to Explore Peer Connections

Learning about Others with Google Street View

Groupworld Group Story-Creating Project

* Connection & Appreciation for Others with Autism

Amazing & Helpful YouTube Videos by People with Autism

* Reciprocity in relationships

Using a Toy Balance to Teach Relationship Reciprocity

* Awareness of negative behaviors, social cause & effect

What I should Have Done Different Worksheet

Customizable Meters for Awareness of Negative Behaviors

Comic Book Conversations / Social Story PowerPoint Template

Self-control Channel Changers for Target Behavior Awareness

Pencil & Pen Memories Worksheets, What Others Remember

Annoy-o-meter, Nice-o-meter

Sticky Notes Kit – Explore Social Hierarchy & Who Is In Charge

Personal Space illustrated eBook

Silly to Serious Kit, Formal & Informal Conduct

Dealing with Losing & Disappointment Illustrated Panels

Missing Object Game – To Practice Sportsmanship

Words Hurt/Words Help Worksheets

Pencil / Pen Memories Worksheets, Explore What Others Remember about us

Question Cards for Rigidity / Flexibility

Question Cards to Explore Tattling & Correcting

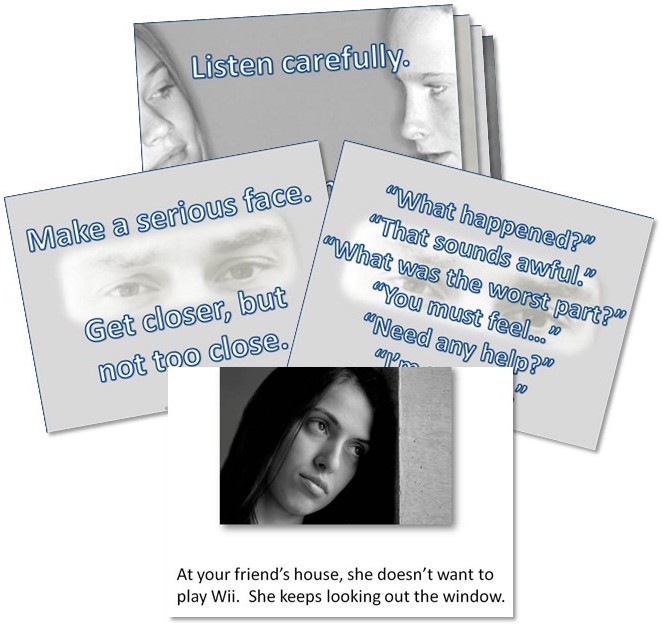

* Showing concern/empathy

Empathy Showing Concern Picture Guide

Empathy Showing Concern Photos for Role Play Practice

* Social Isolation

Worksheets for Exploring Social Isolation

Card Game Activity to Explore Social Isolation

4 Resources for Helping Children with ASD Who Are Obsessed with Fantasy

The Screen Lovers Help Book – Free Download for Screen Addiction

Corona Cards – For Children who are Isolated During the Pandemic

* Teasing/bullying

Teasing & Bullying Teaching Panels & Question Cards

* Romantic attraction and Boy – Girl Relations

Relating to Girls Teaching Panels & Question Cards

Using Girls’ Magazines to Promote Learning about Girls

* Maturity and young adult skills

Young Adult Future Cards for Exploring Young Adult Maturity

Workplace Preparation Q & A Cards

Workplace Preparation Teaching Materials

Workplace Preparation Guide to Job Interviewing

* Creative / Game-Like Social Interaction Problem Solving

Easy Template for Making Your Own Board Game on Social Skills Themes

Holiday /Christmas – Theme On-Screen Social Skills Board Games

Create, Draw, Describe Your Own “Dark Force” & “Light Force”

Fix The Problem Game for Working On Interaction Problems

_______________________________________________________________

Mental Health Professionals

School-based professionals, speech professionals.

Math teaching support you can trust

resources downloaded

one-on-one tutoring sessions

schools supported

[FREE] Fun Math Games & Activities

Engage your students with our ready-to-go packs of no-prep games and activities for a range of abilities across Kindergarten to Grade 5!

How Autism May Affect Students’ Understanding Of Math And What Teachers Can Do To Help

Hilary forbes.

Here we look at the impact of autism on math from my perspective as an autistic teacher who’s spent many years working in schools; as such I’ve taught children with all neurodiversities and have my own unique insight into some of the challenges that math and especially math problem solving can have for the autistic learner.

We look at the key barriers to learning that some autistic children face when learning math, the roots of these and how teachers can remove them without extra workload and more sleepless nights planning and preparing lessons.

Autistic learners are part of a neurodiverse classroom

Overwhelming volume of content in the curriculum, how to think about abstract concepts in math, questions to consider when teaching autistic children math, how autism can affect math problem solving, why are these connections not obvious to our learners, processing time is crucial, understanding how key mathematical connections need to be taught and practiced, putting a plan in place to build relationships and agree expectations, allow for verbal processing or any other special needs, reassure and encourage, autism math takeaways.

Autism Spectrum Condition is a neurological and developmental condition that affects how those with autism interact with other people, including how they communicate, behave and learn.

Autism is a wide and varied condition and presents itself in a broad array of ways, meaning that not all autistic people will behave or face the same challenges when learning math or any other subject.

Autistic children, like any children, can make great mathematicians and can have many cognitive strengths and even savant abilities. However, in some cases, different approaches may need to be utilized to best teach math concepts to autistic students and unlock their mathematical ability .

For example, for some autistic learners, the classroom environment itself can be a challenge, especially if it is brightly lit, heavily decorated or loud. Sensory overload can be a big obstacle, preventing students from being able to focus on what they are learning.

Read more: How To Support A Child With Autism In The Classroom

Math mastery recognizes that children need to have a deep understanding of mathematical concepts and how these concepts connect with one another. In order for this to happen, there needs to be time for processing.

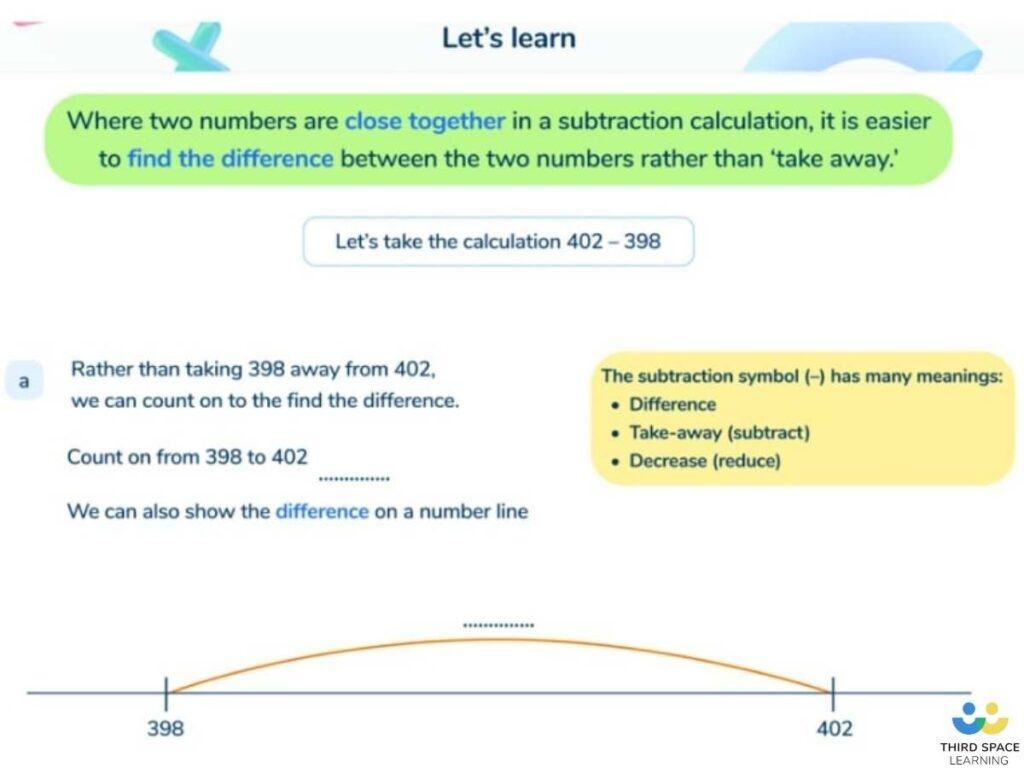

However, the math curriculum can often feel like a race for teachers as they try to cover all topics by the end of the year. This can be detrimental for those children who require more processing time; they can begin to lose the connections they need to build on their knowledge.

When content is covered so quickly, the time for students to process new information is cut short. For some autistic children, this rush through the material can cause sensory overload, as there is a large amount of information to process at one time.

The fast pace of schools (especially in light of the pandemic), can lead to lots of gaps in learning as the student is trying to process the first concept while the teacher has moved on to the next.

This fast pace, combined with the already multisensory environment of a classroom, can be overwhelming for autistic students.

There is now a gradually increasing recognition that all children need more time to acquire a deep understanding of the connections in math, and perhaps that the curriculum needs to be narrower in order for these connections to be really understood.

Third Space Learning’s one-to-one intervention program mitigates this by first identifying the gaps in students’ understanding and developing a tailored set of lessons. These are then covered by a tutor who supports the student at a pace that works for them, moving their learning forward and closing the gap.

There is a fallacy that autistic children cannot learn or understand abstract concepts. This is incorrect.

What autistic children often struggle to understand is not the abstract concept itself, but rather when they are not taught that something is an abstract concept.

In this case, autistic children can think that they are expected to understand abstract concepts in the same way as concrete ideas.

In teaching, it is easy to move seamlessly from concrete to abstract, but it is also easy to forget that children do not always know where that seam lies. This is a crucial aspect of teaching if autistic learners are to grasp the necessary connections.

The best way to ensure more explicit connections is to try to understand every possible angle from which the subject matter can be learned. This can be done by getting into the habit of asking yourself a series of questions.

Here are some questions that you could consider when teaching any child, but especially autistic children. Of course, they are particularly pertinent to the types of math problem solving we encourage all children to explore throughout their math education.

- What could be misunderstood?

- What words or phrases are there that need explaining?

- Are there everyday words used in the subject matter that mean something different in math?

While it might sound obvious, we as teachers need to have a deep familiarity and knowledge of the subject matter and all the different connections with every area of math, before being able to communicate these to any child, especially autistic children.

This does not necessitate having a 1st class degree in mathematics. It means developing the practice of being a learning detective and looking for clues when children do not have those connections in place.

It’s about finding ways to communicate first in everyday language, and then explaining the formal math language.

The missing connections are often much more basic than is often immediately obvious.

Autistic children can experience deficits in executive functioning. This can lead to difficulties in math word problem solving as it involves:

- Organizing information and operations

- Flexibly moving between pieces of information

- Identifying the relevant information in the problem