Drug Testing

- Drug testing looks for the presence or absence of specific drugs in a biological sample, such as urine, blood, or hair. Drug testing cannot diagnose a substance use disorder. As a tool in substance use treatment programs , drug testing can monitor a patient’s progress and inform their treatment. Substance use treatment programs should not use drug testing results alone to discharge patients from treatment. Drug testing is also used in workplace and justice settings.

- While multiple test options are available, urine drug screening is most common. An initial urine drug screen can deliver rapid results but can be affected by factors, such as certain medications, that can cause incorrect results (called a false positive or a false negative) . If an initial test is positive, health care providers can order a sensitive and specific confirmatory test. For all testing methods, accurate interpretation may require consultations with specialists such as Medical Review Officers (MRO) and medical toxicologists.

- NIDA supports and conducts research to improve drug testing by investigating more accurate and accessible technologies and applying drug testing in new ways to support individual and public health. NIDA does not administer drug testing programs, assist in interpreting drug test results , or manufacture, regulate, or distribute drug screening products. Learn more about drug testing regulation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and about workplace drug testing from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) .

What is a drug test?

A drug test looks for the presence or absence of a drug in a biological sample, such as urine, blood, or hair. Drug tests may also look for drug metabolites in the sample. A drug metabolite is a substance made or used when the body breaks down (or “metabolizes”) a drug.

Drug tests target only specific drugs or drug classes above a predetermined cutoff level. 1 A cutoff level is a point of measurement at or above which a result is considered positive and below which a result is considered negative. For example, in workplace drug testing the federal cutoff level for a cannabis drug test in urine is 50ng/mL. A test result below 50ng/mL will be reported as negative even if the result is above 0. This cutoff level helps to limit false positive s. 2

Drug testing is different than “ drug checking ,” which helps people who use drugs determine which chemicals are found in the substance they intend to take. Drug checking is a type of harm reduction .

What is the difference between a drug screen and a confirmatory drug test?

Usually, drug testing involves a two-step process: an initial drug screen and a confirmatory test.

- Initial drug screens or presumptive drug tests are used to identify possible use of a drug or drug class. These tools are also called point-of-care testing and are useful because they can produce rapid results. Initial urine drug screens use the immunoassay method for analysis, which uses antibodies to detect drugs at the molecular level.

- Confirmatory or definitive tests either verify or refute the result of an initial screen. These tests are more specific, more sensitive, and results take longer because they are sent to a laboratory. These tests use methods called gas chromatography/mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry to analyze samples. The results can indicate specific drugs and provide more exact information about how much of a drug is present. 1,3

If an initial drug screen is positive, a second round of more precise confirmatory testing is done to confirm or rule out that positive result.

What substances do drug tests detect?

Drug tests are commonly used to detect five categories of drugs as defined by the federally mandated workplace drug testing guidelines, although health care providers can order additional tests, if needed. 2,3 This list may also change as new drugs enter the drug supply. 4

These drug tests are usually urine tests, though other biological samples can also be used: 2

- Amphetamines, including methamphetamine

- Cannabis (marijuana), which tests for cannabinoid metabolites, including THC metabolites

- Cocaine , which tests for benzoylecgonine, a cocaine metabolite

- Opioids , a class of drugs that includes heroin, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and pain relievers like oxycodone (OxyContin ® ), hydrocodone (Vicodin ® ), codeine, and morphine. This category will have separate tests depending on which opioid is being tested. There is currently no drug test that tests for all opioids.

- Phencyclidine (PCP)

Drug tests can also detect additional categories of drugs:

- Barbiturates

- Benzodiazepines

- MDMA/MDA (Ecstasy/Molly)

How is NIDA advancing research on drug testing?

NIDA supports and conducts research to improve drug testing methods by investigating more accurate and accessible technologies and applying drug testing in new ways to support individual and public health. This research includes efforts to develop new highly specific and sensitive tests for urine, breath, and sweat. It also includes the development of innovative technologies such as wearable sensors that can test for drugs in real time.

NIDA also supports the National Drug Early Warning System , which helps collect and share information on emerging drugs that may inform the development of drug tests.

NIDA does not administer drug testing programs, assist in interpreting drug test results , or manufacture, regulate, or distribute drug screening products. Learn more about drug testing regulation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and about workplace drug testing from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) .

What is drug testing used for?

Drug testing is used to find out whether a person has used a substance in the recent past. Drug testing can sometimes also detect passive exposure to drugs, such as secondhand smoke or prenatal exposure. The length of time following exposure that a drug can be detected during testing can vary.

Drug testing cannot diagnose a substance use disorder. 2

A drug test may be used for different reasons, including:

- Supporting the clinical aims of substance use disorder treatment .

- A medical assessment , such as during emergency department visits for unintentional poisoning, attempts at self-harm, or environmental exposures. In these cases, point-of-care testing is used to help diagnose and manage patients whose symptoms may be related to drug use. 5,6 Newborns can also be tested for possible prenatal exposure to illicit drugs using urine, blood, meconium (an infant’s first bowl movement), hair, or umbilical cord samples. 7

- Preventing prescription drug misuse. Some health care providers will schedule or order random urine drug testing while prescribing controlled substances, such as opioids, stimulants, and depressants. However, this practice is not standardized. 8,9

- Employment. Employers may require drug testing as part of a drug-free workplace program. Drug testing is required by federal law in some workplaces, including safety and security-sensitive industries like transportation, law enforcement, and national security.

- Legal evidence. Drug testing may be part of a criminal or motor vehicle accident investigation or ordered as part of a court case.

- Athletics. Professional and other athletes are tested for drugs that are used to improve performance (sometimes referred to as “doping”). The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency conducts this testing.

- Recovery residences. Communities of people in recovery from substance use disorders may use drug testing to monitor abstinence of residents. 10

How are drug tests performed?

Urine is the preferred and most used biological sample for drug testing, as it is available in large amounts, contains higher concentrations of drugs and metabolites than blood, and does not require needles. 11 Urine drug tests are also available during point-of-care, or outside the laboratory (e.g., doctor’s office, hospital, ambulance, at home). 12

Less commonly, drug testing may use blood or serum, oral fluid (saliva), breath, sweat, hair, or fingernails. 1

There are FDA-approved at-home drug tests (urine or saliva) readily available at pharmacies. It is important to follow specific instructions and send a urine sample to a laboratory for confirmation.

How is drug testing used during treatment for substance use disorders?

Urine drug screening can be an important tool for substance use disorder treatment. 13 Health care providers can use urine drug screens to follow a patient’s progress. Test results are used to determine whether dosing adjustments or other treatment interventions are needed. After unexpected results , patients and health care providers can speak openly about treatment and progress to better tailor the treatment to the patient’s needs. 10,13

Federal guidelines for Opioid Treatment Programs require drug testing. Urine drug tests are often administered as part of the intake process to confirm substance use history and as a routine part of therapy. 14

Understanding the limits of urine drug screening and other toxicology testing is an important part of making treatment decisions. Drug testing is never the sole determinant when making patient care decisions. 10

Contingency management is a behavioral therapy that uses motivational incentives including tangible rewards for drug-negative urine specimens. Contingency management has been demonstrated to be highly effective in the treatment of substance use disorders including addiction to stimulants. 15

What happens if a drug test result is positive during substance use disorder treatment?

If a drug test result is positive during substance use disorder treatment, health care providers may prescribe additional or alternative treatments. Drug test results should not be used as the sole factor when making patient care decisions, including discharge decisions. 10,13 It is best practice for addiction treatment providers to avoid responding punitively to a positive drug test or using it as the basis for expelling someone from treatment. However, actual consequences of a positive drug test during substance use treatment may depend on state laws and the individual program.

Recovery residences (e.g., sober living homes) may also use drug testing to monitor the abstinence of residents, and residents may be expelled on the basis of positive drug tests. However, it is important that expulsion should not prevent or interfere with the individual continuing to receive outpatient addiction treatment. 10

What are the limitations of drug testing?

Urine drug tests do not provide information regarding the length of time since last ingestion, overall duration of use, or state of intoxication. 16

Sometimes urine can be difficult to obtain due to dehydration, urinary retention (the person is unable to empty their bladder), or other reasons. 17

Drug testing can be a useful tool, but it should not be the only tool for making decisions. Drug testing results should be considered alongside a patient’s self-reports, treatment history, psychosocial assessment, physical examination, and a practitioner’s clinical judgment. 2,18

Drug testing can also produce false positives and false negatives.

How accurate are drug tests? Can a drug test result in a false positive or false negative?

All tests have limitations, and false positives or false negatives can occur. 1

A false positive is when a drug test shows the presence of a substance that isn’t there. This can happen during the initial urine drug screening, which uses the immunoassay method (antibodies to detect drugs at the molecular level). Immunoassays are the most commonly available method of testing for drugs in urine. 2 Immunoassays rely on a chemical reaction between an antibody and a drug the test is designed to identify. Sometimes the antibodies can react to other chemicals that are similar to the drug—called cross-reactivity. Cross-reactivity can occur with some over-the-counter medicines, prescription medicines, and certain foods, like poppy seeds. For example, some cough and cold medicines, antidepressants, and antibiotics can cause false positive results. 19,3

A false negative is when a drug test does not show the presence of a substance that is there. This can happen during the initial urine drug screening. A false negative result can happen when the cutoff level used was set too high, so small amounts of the drug or drug metabolites were missed. 2 False negatives can also happen when contaminants are deliberately ingested or added to urine to interfere with a test’s ability to detect a drug’s presence. 20

Laboratory errors can also result in false positives or false negatives.

A confirmatory test can be performed to confirm the initial screening test results. A medical review officer can also interview the patient and review the lab results to help resolve any discrepancies. 1,14

How are drug test results confirmed?

An essential component of any drug testing program is a comprehensive final review of laboratory results. 18 In federally mandated drug testing programs, this role is often filled by a medical review officer, who will review, verify, and interpret positive test results. Medical review officers provide quality assurance and evaluate medical explanations for certain drug test results. The medical review officer should be a licensed physician with a knowledge of substance use disorders. 21

To avoid misinterpreting drug test results, health care providers can use experts in the field. This includes clinical chemists or medical toxicologists at hospitals, clinics, or poison control centers. Expert assistance with toxicology interpretations can improve the accuracy of drug test results.

Can NIDA assist me with interpreting or disputing the results of a drug screen?

NIDA is a biomedical research organization and does not provide personal medical advice, legal consultation, or medical review services to the public. While NIDA-supported research may inform the development and validation of drug-screening technologies, NIDA does not manufacture, regulate, or distribute laboratory or at-home drug screening products. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA ) regulates most of these products in the United States. Those with concerns about drug screening results may consider reaching out to the drug-screening program or a qualified health care professional. For more information on workplace drug screening, please visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) Division of Workplace Programs website.

Latest from NIDA

What do drug tests really tell us?

NIH and FDA leaders call for more research, lower barriers to improve and implement drug- checking tools amid overdose epidemic

NIH launches harm reduction research network to prevent overdose fatalities

Find more resources on drug testing.

- Learn more about drug test regulation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) .

- Learn more about workplace drug-testing programs from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) .

- Find basic drug testing information from MedlinePlus , a service of NIH’s National Library of Medicine (NLM).

- Find information about drug testing in child welfare from the National Center on Substance Abuse and Child Welfare .

- McNeil SE, Chen RJ, Cogburn M. Drug testing . In: StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing; January 16, 2023.

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Clinical drug testing in primary care . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Technical Assistance Publication Series , No. 32 2012. Accessed May 3, 2023

- Moeller KE, Lee KC, Kissack JC. Urine drug screening: practical guide for clinicians . Mayo Clin Proc . 2008;83(1):66-76. doi:10.4065/83.1.66

- Gerona RR, French D. Drug testing in the era of new psychoactive substances . Adv Clin Chem . 2022; 111:217-263. doi:10.1016/bs.acc.2022.08.001

- Mukherji P, Azhar Y, Sharma S. Toxicology screening . StatPearls . Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed May 3, 2023.

- Bhalla A. Bedside point of care toxicology screens in the ED: Utility and pitfalls . Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci . 2014;4(3):257-260. doi:10.4103/2229-5151.141476

- Farst KJ, Valentine JL, Hall RW. Drug testing for newborn exposure to illicit substances in pregnancy: pitfalls and pearls . Int J Pediatr . 2011;2011:951616. doi:10.1155/2011/951616

- Chakravarthy K, Goel A, Jeha GM, Kaye AD, Christo PJ. Review of the Current State of Urine Drug Testing in Chronic Pain: Still Effective as a Clinical Tool and Curbing Abuse, or an Arcane Test? . Curr Pain Headache Rep . 2021;25(2):12. Published 2021 Feb 17. doi:10.1007/s11916-020-00918-z

- Raouf M, Bettinger JJ, Fudin J. A practical guide to urine drug monitoring . Fed Pract . 2018;35(4):38-44.

- Jarvis M, Williams J, Hurford M, et al. Appropriate use of drug testing in clinical addiction medicine . J Addict Med . 2017;11(3):163-173. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000323

- Kapur BM. Drug-testing methods and clinical interpretations of test results . Bull Narc . 1993;45(2):115-154.

- Hadland SE, Levy S. Objective Testing: Urine and Other Drug Tests . Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am . 2016;25(3):549-565. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2016.02.005

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance abuse: Clinical issues in intensive outpatient treatment . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series , No. 47 2006. Accessed May 3, 2023.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Federal guidelines for opioid treatment programs . Published January 2015. Accessed May 3, 2023.

- Petry NM. Contingency management: what it is and why psychiatrists should want to use it . Psychiatrist . 2011;35(5):161-163. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.110.031831

- Dobrek L. Lower Urinary Tract Disorders as Adverse Drug Reactions-A Literature Review . Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(7):1031. Published 2023 Jul 20. doi:10.3390/ph16071031

- Chua I, Petrides AK, Schiff GD, et al. Provider Misinterpretation, Documentation, and Follow-Up of Definitive Urine Drug Testing Results . J Gen Intern Med . 2020;35(1):283-290. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05514-5

- Reisfield GM, Teitelbaum SA, Jones JT. Poppy seed consumption may be associated with codeine-only urine drug test results . J Anal Toxicol . 2023;47(2):107-113. doi:10.1093/jat/bkac079

- Kale N. Urine Drug Tests: Ordering and interpreting results . Am Fam Physician . 2019;99(1):33-39.

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Division of Workplace Programs. Medical review officer guidance manual for federal workplace drug testing programs . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . 2020. Accessed April 20, 2023.

- Mitra | VAMS Microsampling

- Mitra Laboratory Tools

- Mitra | Collection Kits

- Mitra | RNA Preservation

- hemaPEN | DBS Next-Gen

- hemaPEN Laboratory Tools

- Harpera | Skin Microbiopsy

- hemaPEN Resources

- Mitra Resources

- Harpera Resources

- Microsampling Resource Library

- Industry Applications

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQS)

- Lab Directory

- Newsroom / Media

The Critical Role of Drug and Alcohol Testing: Protecting Lives and Livelihoods

by Neoteryx Microsampling on Jan 25, 2021 9:00:00 AM

Drug and alcohol misuse isn't just a private problem; it’s a societal one, affecting families, communities, and workplaces. The National Drug-Free Workplace Alliance points out that over 74% of illegal drug users are employed. More alarmingly, such users play a role in nearly 40% of all industrial fatalities in the US. This data underscores the essential role of drug and alcohol testing, especially within professional environments.

Understanding the Value of Drug Testing

Ensuring Employee Well-being : Drug testing provides an opportunity for employees to acknowledge substance abuse issues. It can also help identify early signs of addiction facilitating timely interventions, and potentially preventing fatal accidents.

Protecting Businesses : Companies benefit directly by ensuring a safer, drug-free workplace. This can safeguard a business's reputation, assets, and overall employee morale.

Deterring Substance Misuse : The risk of job loss due to positive drug tests can deter many from drug misuse.

How Drug Testing Works: Procedures and Types

There's a lack of universal standards in clinical drug testing practices, as noted by the American Society of Addiction Medication . However, this hasn't deterred the effective application of drug tests in various settings, from homes to workplaces.

While traditional venues such as clinics have been the norm, remote drug testing is gradually gaining traction. This trend is being facilitated by labs that now process samples mailed to them, increasing the feasibility of at-home drug tests.

Among the available tests, blood tests are deemed the most accurate. They provide specific information about drug and alcohol concentration levels. Plus, compared to urine samples, it's far more challenging to tamper with blood samples.

Recent advancements have led to the development of remote blood collection devices, which are minimally invasive and user-friendly. Such tools typically employ the finger-prick method, making them suitable for at-home use or during face-to-face sessions at treatment facilities.

The Role of Drug Testing in Addiction Recovery

Routine drug testing is a pivotal component of many recovery programs. By identifying relapses early, it paves the way for swift interventions, helping affected individuals return to their recovery path.

Consistent testing also plays a central role in places like “Board & Care” or “Sober Living” facilities. Here, staying drug-free isn't just a personal goal—it’s a requisite. Those who relapse, evidenced by a positive drug test, can lose their place in the program, making regular testing a compelling motivator for sustained recovery.

In Summary : Drug and alcohol testing is more than just a procedural measure; it's a critical tool in fostering healthier workplaces, ensuring employee well-being, and supporting individuals on their journey to recovery.

To find a microsampling lab that performs drug testing on remote specimen samples, visit the Microsampling Lab Directory by clicking the icon below:

Comments (3)

- Microsampling (209)

- Research, Remote Research (117)

- Venipuncture Alternative (107)

- Clinical Trials, Clinical Research (82)

- Mitra® Device (74)

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, TDM (50)

- Dried Blood Spot, DBS (38)

- Biomonitoring, Health, Wellness (31)

- Infectious Disease, Vaccines, COVID-19 (25)

- Decentralized Clinical Trial (DCT) (23)

- Blood Microsampling, Serology (21)

- Omics, Multi-Omics (18)

- Toxicology, Doping, Drug/Alcohol Monitoring, PEth (17)

- Specimen Collection (16)

- hemaPEN® Device (13)

- Preclinical Research, Animal Studies (12)

- Pharmaceuticals, Drug Development (9)

- Harpera® Tool (5)

- Industry News, Microsampling News (5)

- Skin Microsampling, Microbiopsy (5)

- Company Press Release, Product Press Release (4)

- Antibodies, MAbs (3)

- Environmental Toxins, Exposures (1)

- April 2024 (2)

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (2)

- January 2024 (4)

- December 2023 (3)

- November 2023 (3)

- October 2023 (3)

- September 2023 (3)

- July 2023 (3)

- June 2023 (2)

- April 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (2)

- February 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (3)

- December 2022 (2)

- November 2022 (3)

- October 2022 (4)

- September 2022 (3)

- August 2022 (5)

- July 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (2)

- May 2022 (4)

- April 2022 (3)

- March 2022 (3)

- February 2022 (4)

- January 2022 (5)

- December 2021 (3)

- November 2021 (5)

- October 2021 (3)

- September 2021 (3)

- August 2021 (4)

- July 2021 (4)

- June 2021 (4)

- May 2021 (4)

- April 2021 (3)

- March 2021 (5)

- February 2021 (4)

- January 2021 (4)

- December 2020 (3)

- November 2020 (5)

- October 2020 (4)

- September 2020 (3)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2020 (6)

- June 2020 (4)

- May 2020 (4)

- April 2020 (3)

- March 2020 (6)

- February 2020 (3)

- January 2020 (4)

- December 2019 (5)

- November 2019 (4)

- October 2019 (2)

- September 2019 (4)

- August 2019 (5)

- July 2019 (3)

- June 2019 (7)

- May 2019 (6)

- April 2019 (5)

- March 2019 (6)

- February 2019 (5)

- January 2019 (8)

- December 2018 (3)

- November 2018 (4)

- October 2018 (7)

- September 2018 (6)

- August 2018 (5)

- July 2018 (8)

- June 2018 (6)

- May 2018 (5)

- April 2018 (6)

- March 2018 (4)

- February 2018 (6)

- January 2018 (4)

- December 2017 (2)

- November 2017 (3)

- October 2017 (2)

- September 2017 (4)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (4)

- June 2017 (5)

- May 2017 (6)

- April 2017 (6)

- March 2017 (5)

- February 2017 (4)

- January 2017 (1)

- July 2016 (3)

- May 2016 (1)

- April 2016 (2)

Receive Blog Notifications

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

student opinion

Should Schools Test Their Students for Nicotine and Drug Use?

Would such testing result in fewer students using these substances?

By Shannon Doyne

Find all our Student Opinion questions here.

Do you think schools should test their student for drugs, alcohol and nicotine? Do you think such tests would encourage students to stay away from drugs? Or do you worry these tests are an invasion of privacy, or that they might be ineffective?

In “ Ohio High School Plans to Drug-Test All Students at Least Once a Year ,” Derrick Bryson Taylor writes about Stephen T. Badin High School in Hamilton, Ohio. Starting in January, students at the high school will be tested at least once a year for illicit drugs, alcohol, nicotine and other banned substances:

Students are required to consent to the testing as a condition of their enrollment at the school, and potential consequences for violating the drug policy include suspension and expulsion, the letter said. Under the new guidelines, a first positive drug test alone would not necessarily result in disciplinary action, provided there are no other violations of the policy, like rules against intoxication during school hours or possession of drugs on campus. But a comprehensive intervention plan would be put into place after a second positive test, and expulsion might be recommended after a third.

The policy reflects a growing trend among U.S. schools and districts:

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study from 2016 said more than 37 percent of school districts had adopted a drug-testing policy. There seems to be an increase in similar programs across the country, Cindy Huang, assistant professor of counseling psychology at Teachers College, Columbia University, said in an interview on Thursday. The research to prove if drug testing is beneficial to students is mixed, according to the Professor Huang. “There’s really no clear indication that implementing mandatory drug testing will directly lead to better and reduced substance abuse rates,” she said. Parents across the country should not be concerned if their school begins a drug-testing program if it is “properly planned and then implemented,” Professor Huang said. In such cases, she said, it has the potential to work as prevention. She added that parents should be asking detailed questions about what happens if a child tests positive, whether testing will truly be conducted at random and in such a way that does not target specific children, and whether there will be programs in addition to drug testing that will promote awareness of substance use.

Students, read the entire article, then tell us:

What would happen if your school started testing all students for drugs, alcohol and nicotine? Would the results surprise school leaders? Would the policy likely change student behavior, in your opinion?

Does your school already test students for illegal substances? Are there rules about who can be tested and how many times they can be tested? Is there a clear policy for handling students who test positive?

Do you think drug testing is an invasion of privacy? Why or why not?

The article raises the following issue about Stephen T. Badin High School’s drug-test policy: Since the school will have no maximum number of times it can test a particular student, the policy can lead to “arbitrary enforcement and harassment.” What are your thoughts on this idea? Have you ever seen a student or group of students targeted for disciplinary reasons? Explain.

If you were an administrator at a school where it is obvious that students are vaping, drinking alcohol or using illegal drugs, how would you handle the issue? Would you recommend a drug-testing policy similar to that of Stephen T. Badin High School? Would you recommend a different kind of policy? Why?

Students 13 and older are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Serv Res

- v.42(2); 2007 Apr

Workplace Drug Testing and Worker Drug Use

To examine the nature and extent of the association between workplace drug testing and worker drug use.

Data Sources

Repeated cross-sections from the 2000 to 2001 National Household Surveys on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) and the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

Study Design

Multivariate logistic regression models of the likelihood of marijuana use are estimated as a function of several different workplace drug policies, including drug testing. Specific questions about penalty severity and the likelihood of detection are used to further evaluate the nature of the association.

Principal Findings

Individuals whose employers perform drug tests are significantly less likely to report past month marijuana use, even after controlling for a wide array of worker and job characteristics. However, large negative associations are also found for variables indicating whether a firm has drug education, an employee assistance program, or a simple written policy about substance use. Accounting for these other workplace characteristics reduces—but does not eliminate—the testing differential. Frequent testing and severe penalties reduce the likelihood that workers use marijuana.

Conclusions

Previous studies have interpreted the large negative correlation between workplace drug testing and employee substance use as representing a causal deterrent effect of drug testing. Our results using more comprehensive data suggest that these estimates have been slightly overstated due to omitted variables bias. The overall pattern of results remains largely consistent with the hypothesis that workplace drug testing deters worker drug use.

A large literature suggests that employee substance use in the workplace may impose high costs to firms in the form of lower productivity, increased absenteeism, and more workplace accidents (see National Research Council 1994 for a review). Partially as a response to these costs, employers have responded by implementing a variety of policies and programs designed to reduce employee substance use. In addition to education programs and written standards such as “Zero Tolerance” policies, employers have in the past two decades increasingly turned to drug testing programs. Currently, about 46 percent of all workers report that their employer performs drug testing, although other sources indicate that as many as 90 percent of Fortune 200 firms use some type of drug testing ( Flynn 1999 ). The rationale behind workplace drug testing is straightforward: by raising the expected costs of workplace substance use, the programs aim to deter consumption of dangerous substances by current and prospective employees.

Indeed, anecdotal evidence suggests that both supporters and opponents of workplace drug testing—which increased substantially throughout the late 1980s and remained steady throughout the 1990s—believe that testing deters employee drug use. Despite this, there are only three studies that have used nationally representative data to provide evidence on whether large-scale employer drug testing deters employee drug use ( Hoffmann and Larison 1999 ; SAMHSA 1999; French, Roebuck, and Alexandre 2004 ). Each of these finds that drug use is lower among individuals whose firms test for drugs. Some have interpreted the negative testing/use correlation as representing a causal deterrent effect of testing on worker drug use.

Admittedly, a strong negative relationship between testing and use is consistent with such an interpretation. However, the same observed negative correlation is also consistent with a handful of equally plausible alternative explanations that have not been adequately ruled out by previous research. For example, the presence of a workplace drug testing program may simply proxy for other omitted firm characteristics. Previous research has not adequately addressed concerns about these and other omitted variables biases, and as such the claim that a negative testing/use relationship reflects a causal deterrent effect warrants further investigation.

This research question has become increasingly important, as in recent years firms have begun to question the merits of drug testing. This opposition has arisen, in part, because drug testing is a huge industry in the United States, costing employers six billion dollars per year ( Costantinou 2001 ). Of course, if drug testing reduces workplace substance use (either through a deterrent effect among current workers or through firm screening), then the programs may well be worth their expense. One important evaluation question, then, is: Do workplace drug testing programs really reduce substance use? In this paper, we revisit this question by using more comprehensive data than has been used previously to more fully evaluate alternative explanations for the negative relationship between testing and use.

PREVIOUS LITERATURE

Although there are large and growing independent literatures on the institutional details regarding workplace substance testing programs and on the effects of workplace drug testing programs on outcomes such as absenteeism, productivity, and workplace accidents, we do not review them here. 1 Instead, this section focuses on the handful of studies that have specifically asked whether workplace drug testing has a deterrent effect on employee drug use. Before reviewing these studies, however, it is worth noting that a panel of experts commissioned by the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine wrote in a 1994 book that “[d]espite beliefs to the contrary, the preventive effects of drug-testing programs have never been adequately demonstrated” (p. 11).

Since 1994 NAS/IOM book, there have been at least five large-scale studies of the effects of workplace drug testing on employee substance use; three of these have used data from various years of the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. First, a 1999 study by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) related the presence of drug testing programs to self-reported marijuana use and heavy drinking rates using the 1994 and 1997 waves of the NHSDA. That study found a significant negative relationship between workplace testing and drug use in the 1997 data. A similar study published in 1999 used only on the 1994 NHSDA and similarly found a significant negative relationship between workplace drug testing and self-reported illicit drug use ( Hoffmann and Larison 1999 ). Finally, French, Roebuck, and Alexandre (2004) used data from the 1997 and 1998 NHSDA and found a significant negative association between testing and drug use.

All of the studies to some extent interpret the observed negative association as representing a “deterrent” effect of workplace drug testing. Despite this claim, there are several reasons to be skeptical that the associations uncovered by these studies do in fact reflect deterrence effects. First, none of the studies has had information on the penalties individuals face for failing a drug test. We show below that about a quarter of workers in worksites that test employees for drugs report either that there is “no official penalty” for first offense or that “nothing happens.”Understanding the sensitivity of individual behavior to differential sanctions is crucial for testing economic theories of deterrence. Second, the existing studies provide little or no information on other drug programs or policies in the respondents' workplaces. If drug testing is simply proxying for a relatively high value of health placed by firms, or if firms that impose drug testing are more likely to provide other relevant programs such as drug education (which itself might have independent effects on use), then the drug testing estimates may be upward biased. For these reasons, one might be skeptical that the negative testing/use correlations do in fact represent true deterrence effects of testing.

A common characteristic of the above studies is that they use observational data to examine the nature of the cross-sectional association between workplace drug testing and worker drug use (we use a similar approach below). In contrast, we are aware of only one large-scale study to use a pre–post treatment-control research design to study the effects of workplace drug testing. Specifically, Mehay and Pacula (1999) consider the effects of an aggressive “Zero Tolerance” drug testing policy that was implemented in the United States military in 1981. Using data from multiple surveys before and after implementation of the policy, the authors compare differences in drug use rates for military personnel versus civilians over the period 1979–1995. They find much lower rates of drug use reported by military personnel in 1995 compared with civilians, and this difference remains even after controlling for the associated military/civilian difference that existed in the preprogram period. Using a policy change in this manner allows a more direct assessment of causality in the relationship between drug testing and drug use than in observational studies such as those considered here.

DATA AND EMPIRICAL APPROACH

Our main analysis data come from the public-use files of the National Household Surveys on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) over the period 2000–2002. 2 These data were first collected in 1971 and in recent years have been administered annually to produce prevalence estimates of substance use in the United States. Youths under age 25 and racial minorities are oversampled. As early as the 1994 wave of the NHSDA, the questionnaire has included a section on substance use policies and programs at the individual's workplace. These include whether the individual's employer: (1) had a written policy regarding substance use; (2) provided substance use education; (3) provided an employee assistance program (EAP) for workers with drug or alcohol problems; and (4) tested its employees for drugs and alcohol. 3 We follow most previous research by considering only drug (not alcohol) testing. We do so for several reasons: there is very little independent variation in alcohol testing (almost all employers that test for alcohol also test for drugs); jobs that test for alcohol tend to be qualitatively distinct and/or mandated by the federal government (such as transportation workers); and alcohol is not an illegal substance for individuals over age 21. We further restrict attention to marijuana because previous evidence suggests that it is the main concern of employers and the drug with the highest test positive rates. 4 Also, use rates of other illicit substances are so low as to provide insufficient statistical power.

The 2000–2002 NHSDA surveys also asked follow-up questions regarding the nature of drug testing for those indicating their employers performed testing. These included whether the employer tested as part of the hiring process, randomly, or both. Respondents are also asked about the penalty for first drug test offense in their workplace. The substantive responses included: being fired, referred to treatment/counseling, nothing, or something else. We use these penalty severity responses below to provide descriptive evidence on the nature of the underlying relationship between testing and use.

In addition to questions about drug testing, the core NHSDA survey asks respondents about recent marijuana use. Notably, these questions are asked in the first part of the survey, well before questions on drug testing programs are administered. We use information from these responses to create an outcome variable called Marijuana Use that equals one if the respondent used marijuana at least 1 day of the previous 30 and zero otherwise. 5

We restrict attention to individuals age 18 and older who report they are currently working (the drug testing questions were not asked of those without jobs). We further restrict attention to those reporting that they work for a private for-profit firm, as some government workers face mandated drug testing. To account for the uneven distribution of marijuana use in the population, we estimate the marijuana participation model using standard logit regression. The general form of the model is given by

where Y is the marijuana use indicator. X is a vector of demographic and job information, including a male dummy, three education dummies, two race dummies, two age category dummies, a military service dummy, five firm size dummies, 16 industry dummies, 15 occupation dummies, and 2 year dummies. Geographic identifiers are not available in the public use files of the NHSDA. As in previous research, we are therefore unable to append relevant state policies and prices to the individual observations or to account for state level clustering. All regressions are weighted using the NHSDA sampling weight.

MAIN RESULTS

Table 1 presents means of key variables (weighted to be nationally representative). The first column of Table 1 presents means for the full sample, while the second and third columns present means separately by whether the respondent reports that her employer performs workplace drug testing. The top panel presents demographic characteristics and shows that males are more likely to work in jobs where the employer performs drug testing, while younger workers are less likely to work in these types of jobs. Highly educated workers are also less likely to work in a job subject to drug testing, while black respondents are over-represented in the group subject to drug testing.

Descriptive Statistics 2000–2002 National Household Surveys on Drug Abuse

Sample is adults age 18+ who work for a private for-profit firm in the 2000–2002 National Household Surveys on Drug Abuse, public-use files. Weighted percents.

The bottom panel of Table 1 presents characteristics of the employer. With respect to the main workplace policy variable of interest, 46 percent of the full sample reports that their employer performs workplace drug testing. Interestingly, Table 1 also shows that the other types of workplace policies are more likely to be observed by employees whose worksites have drug testing programs, a pattern that is consistent with the possibility that unobserved characteristics about employers are partially responsible for the negative association between workplace drug testing and worker drug use found previously.

The key relationship of interest is also apparent in the data shown in Table 1 : about 6 percent of the working sample reports having used marijuana in the past 30 days, and this rate is higher among respondents whose employers do not test for drugs. Some of the raw gap in use, however, may be related to the differences in demographic characteristics associated with workplace drug testing that were also apparent in Table 1 . We control directly for these observed characteristics in Table 2 , which reports adjusted odds ratios and associated standard errors on the relevant drug testing indicator in models that successively add more control variables (each entry in Table 2 is from a different regression). The testing estimates in column 1 are from sparse models that only control for year effects and the dummy variable indicating the respondent does not know if the employer performs substance use testing. Column 2 adds the individual demographic characteristics (age, education, etc.), while column 3 includes firm size and occupation dummies and column 4 adds industry dummies. These job characteristics may be important, as some courts and governments have regulated the types of jobs in which testing can take place (e.g., safety-sensitive positions).

Workplace Testing IS Negatively Related to Marijuana Participation

Sample is adults age 18+ who work for a private for-profit firm in the 2000–2002 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, public-use files. Each entry represents a different model. Models are estimated using logit, and adjusted odds ratios are presented for the drug testing indicator with standard errors presented below in parentheses. Controls include: the drug testing indicator, a dummy variable indicating the respondent does not know if there is a workplace testing program, a male dummy, dummies for less than high school education, some college, and BA or more, dummy variables for non-Hispanic black and Hispanic, dummies for age groups 25–34 and 35+, a military service dummy, 2 year indicators, five firm size indicators, 15 occupation indicators, and 16 industry indicators.

The relationships in the raw data observed in Table 1 are largely unchanged after inclusion of detailed covariates in Table 2 . For example, the raw model for past month marijuana use shows a significant gap in column 1: workers whose employers test for drugs are just 0.57 times as likely to report using marijuana in the past month compared with workers whose employers do not test for drugs. Adding demographic and employer characteristics changes this only slightly: in the fully saturated model the adjusted odds ratio is just 0.634 and remains significant at the one percent level in every specification.

Of course, there may be other unmeasured characteristics about firms that perform drug testing that might also be negatively correlated with substance use. Specifically, Table 1 showed that individuals whose employers test for drugs are much more likely to report that their employer provides substance use education (56 percent of individuals whose employers test for drugs versus 21 percent of other workers), has an official substance use policy (94 versus 53 percent), or has an EAP (68 versus 28 percent). While not surprising, these patterns do suggest the likely presence of omitted variables about firms. That is, some firms might just be “anti-drug,” which could result in drug testing programs, other substance use policies, and workers that are relatively substance free. Importantly, all of these could be true even in the absence of a deterrent effect of testing.

Table 3 makes this point explicitly by showing the association between each of the substance use policies listed above in similarly specified models for marijuana participation (i.e., Equation 1 above, replacing the drug testing indicator with the drug education indicator, and so forth). These models include all the control variables listed in column 4 of Table 2 . In each of the first four columns the adjusted odds ratio for the relevant workplace policy indicator is less than one and highly significant, indicating that workers whose employers have these policies are less likely to report marijuana use. However, in the rightmost column of Table 3 when we separately control for each type of workplace policy, we find that the magnitude of the differentials between each of the policies—including workplace drug testing—and worker marijuana use is smaller (i.e., the adjusted odds ratios are closer to one) than when they are each entered separately. Moreover, the statistical significance of the estimates is reduced or eliminated. These patterns suggest that previous drug testing estimates have been biased upward from failure to account for other workplace programs. Despite this, an important testing/use association remains: the estimate in column 5 of Table 3 indicates that respondents whose employers test for drugs are only about 0.7 times as likely to have used marijuana in the past 30 days as respondents whose employers do not test for drugs. 6

Evidence on Omitted Variables Bias Adjusted Odds Ratios for Various Policy/Program Indicators—Each Column Represents a Different Model 2000–2002 NHSDA

See notes to Table 2 for control variables. All models also include the relevant “don't know” dummy variables for each workplace policy.

Another possibility for the observed testing/use relationship is that worker-based sorting and omitted individual characteristics may drive the relationship. It could be, for example, that people with unobserved preferences for health are systematically more likely to sort into jobs where workplace drug testing is required. And, individuals who use drugs may sort out of jobs that require such testing. 7 These individuals might have differentially poor health or health habits, or they may have a higher preference for risk, for example. We can assess the empirical importance of these factors in two ways. First, in results unreported but available upon request, we re-estimated Equation (1) above including an additional control for self-rated health (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor). We also estimated models that included dummy variables indicating that the respondent always wears a seatbelt when riding in a car or never/rarely wears a seatbelt. Neither of these controls—either in isolation or together—substantively altered the adjusted odds ratio for the drug testing indicator. 8 This suggests that bias from unobserved worker sorting is not likely driving the observed association between drug testing and marijuana use.

Does the association between workplace drug testing and worker drug use plausibly reflect deterrent effects of drug testing? To address this question, we turn to two additional sets of variables that capture variation in expected costs of employee drug use. First, we use responses about whether the employer testing is performed at the hiring stage, at random, or both at hiring and at random. These variables arguably measure the aggressiveness of workplace testing and the likelihood of detection. 9 Second, we use previously unexplored data on the penalty for first drug test offense as reported by the individual. If the reductions in use reflect deterrence effects, then the estimated reductions in substance use should be increasing in penalty severity.

These estimates are presented in Table 4 : the results regarding whether the employer tests prehire only, at random only, or both prehire and at random are presented in column 1, while column 2 presents the results for the expected penalty severity variables. We find that individuals reporting that their employer tests both at hire and at random are only 0.44 times as likely as individuals whose employers do not perform drug testing to report past month marijuana use. More importantly, we estimate that the likelihood of marijuana participation among individuals whose employers test both at hiring and randomly is significantly lower than participation among individuals whose employers test only at random or only at hiring. These patterns are consistent with deterrent effects of testing associated with an increased likelihood of detection.

Worker Drug Use Is Decreasing in the Likelihood of Detection and Penalty Severity, Adjusted Odds Ratios for Various Employer Policies—Each Column Is a Different Model, 2000–2002 NHSDA

See notes to Table 2 . The model in column 1 also includes a dummy variable indicating the respondent did not know if the employer tested as part of the hiring process and a dummy variable indicating the respondent did not know if the employer tested randomly. The model in column 2 also includes a dummy indicating the person does not know the penalty for first offense.

The second column of Table 4 presents the penalty severity results. If drug testing reduces substance use primarily through a deterrent effect, we would expect the estimated relationships between each of the various penalties and marijuana participation to be increasing in the severity of the penalty. That is, the dummy variable indicating violators are fired upon first offense should have the smallest adjusted odds ratio, followed by treatment/counseling referral. This is precisely the pattern that emerges. Specifically, we find that individuals reporting that the penalty for first offense is getting fired (i.e., individuals subject to a “Zero Tolerance” policy) are just 0.56 times as likely to report past month marijuana use compared with individuals whose employers do not test. Moreover, the coefficient on the most severe penalty—being fired—is statistically different from the second most costly penalty (treatment/counseling). That substance use is strongly decreasing in penalty severity is again consistent with a deterrent effect of drug testing.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The results presented above provide further evidence consistent with the idea that workplace drug testing may deter worker drug use. In particular, we have extended previous research by controlling for other potentially confounding workplace policies, as well as providing new evidence on the relationship between marijuana use, the likelihood of detection, and penalty severity. A number of concerns, however, remain. Two of particular importance deal with reporting: first, do individuals report accurate information about the presence of workplace testing? And second, do individuals report accurate information about their drug use?

To answer the first question, we examined self-reported drug testing data from the 1994 NHSDA to independent worksite survey data collected by the National Institute on Drug Abuse in 1993. The results of the latter survey of large employers (50+ full time workers) were published in 1996, and we used those published estimates to compare testing rates by industry and geographic region to the associated rates reported by individuals in the NHSDA with firm sizes of 25+individuals ( Hartwell et al. 1996 ). 10 We found that the patterns from the independent worksite survey corresponded very closely to the self-reported data from the NHSDA. For example, about 62 percent of employees in the NIDA survey were covered by an employer drug testing program, while the associated rate in the NHSDA was 59.5 percent. Moreover, these rates by industry revealed qualitatively identical and quantitatively similar patterns in the industries in which testing is most highly concentrated: communications, utilities, and transportation have the highest testing rates (about 85 percent in each sample), followed closely by mining and construction and manufacturing. The geographic testing patterns also generally conformed across the two sources, with the highest testing rates reported in the South and the lowest in the Northeast. These patterns suggest that individual self-reports of workplace testing are consistent with independent measures of actual testing practices. 11

The other serious reporting concern is that individuals underreport drug use in survey data; this problem is well-known and has been addressed at length elsewhere (see, for example, Mensch and Kandel 1988 ). Of course, if the propensity to underreport substance use is uncorrelated with the presence of testing, then this concern is quite minor in the context of evaluating the deterrence hypothesis. More worrisome, however, is the possibility that underreporting in the NHSDA survey is correlated with workplace testing. For example, individuals who face large work sanctions (such as job loss) if they get caught using drugs may simply be less likely to tell anyone that they use drugs. To provide some evidence on this issue we estimated models relating drug use to the likelihood of detection (as proxied by whether the firm tests at hire, at random, or both) that excluded individuals with the strongest incentives to underreport use: those who report that failing a drug test at their worksite results in termination of employment. Even in this subsample, we found that individuals whose employers test for drug use were significantly less likely to report past month marijuana use. Moreover, the evidence for the deterrence hypothesis remained: the estimate for the variable indicating the employer tests both at hire and at random indicated significantly lower likelihood of marijuana participation compared with the other two dummy variables indicating either hiring testing or random testing only. That these tests of the deterrence hypothesis survive exclusion of individuals who should be most susceptible to testing-based underreporting is consistent with a deterrent effect of drug testing.

These alternative hypotheses highlight the fact that this study is subject to some important limitations, all of which are shared by previous studies using these data. One problem is that the NHSDA does not provide information on the location of drug use or the degree of impairment associated with such use. Much of the controversy regarding drug testing surrounds the fact that testing positive for, say, marijuana use need not imply that the individual is impaired At Work. As impairment is the more relevant concern for employers, one could argue that examining the effect of testing on marijuana use is somewhat misguided. 12

Also, the NHSDA are cross-sectional in nature; as such, we have no ability to determine the precise ordering of substance use, employment flows, and drug testing. Cross-sectional data also limit the strength of our conclusions with respect to the underlying structural relationships between drug testing and drug use: absent a compelling strategy for addressing nonrandom adoption of workplace drug testing (e.g., instrumental variables), we have instead tried to mitigate obvious sources of omitted variables bias by including detailed worker and employer characteristics. To the extent that the negative relationship in the cross-section between testing and use survives these controls, this increases support for the hypothesis that the differentials are true testing effects. Our approach cannot prove, however, that drug testing causes a reduction in use.

Finally, this paper has not evaluated the overall cost/benefit analysis associated with workplace drug testing. That is, are any benefits with respect to increased productivity, decreased accidents, etc., that may be attributable to workplace drug testing worth the associated costs? Given that these costs have risen substantially in recent years—now representing a nontrivial expense for employers—the answer to this question is not obvious. Such a calculation would also require an estimate of the additional job search costs imposed on various types of workers with different preferences regarding drug use and workplace drug testing policy. Given that the current paper cannot pinpoint causality directly, these questions—while important—are beyond our scope.

Despite these limitations, this paper has advanced the previous literature by providing a more comprehensive analysis of workplace drug testing and worker substance use. Overall, the results are most consistent with a deterrent effect of workplace drug testing on worker drug use that cannot be easily explained away by omitted variables about firms or workers, or by selection and sorting stories. We estimate that respondents subject to workplace drug testing are about 0.6–0.7 times as likely to have used marijuana in the past 30 days compared with similarly situated individuals whose employers do not test for drugs. Future work might use these estimates in combination with evidence on the association between drug testing and productivity to provide new insight on underlying structural relationships between substance use and workplace outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Jeff DeSimone, Daniel Eisenberg, Mireille Jacobson, and Christo Karuna for helpful discussions. The editors, anonymous referees, and seminar participants at The Paul Merage School of Business and the Economics Department at UC Irvine provided very useful comments. All errors are those of the author.

1 See, for example, National Research Council/IOM 1994 book, Under the Influence , for a review.

2 We also replicated previous findings using data from 1994 to 1999, and these results are available upon request. We focus on 2000–2002 because these are the only years to provide data on penalty severity, and sample sizes in these years were increased such that at least 900 households per state were sampled. In 2002 the NHSDA changed its name to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Throughout the paper, we refer simply to the NHSDA. There were some substantive changes that accompanied the name change in 2002, including the provision of a monetary incentive to respondents. The main results are not sensitive to excluding the 2002 data; they are included here for completeness.

3 The NHSDA does ask respondents whether the employer's written substance use policy covers alcohol, drugs, or both. However, nearly all respondents report that the policy covers both drugs and alcohol. We do not delete the handful of individuals ( < 10 in each survey year) who report the policy covers alcohol but not drugs. EAPs are generally directed at workers with alcohol problems.

4 Data from Quest Dynamics published at Workforce shows that in recent years about 60 percent of all positive drug tests in the U.S. workforce are for marijuana; the next closest substance is cocaine at < 15 percent. There is also evidence that underreporting of marijuana use is less severe than for other drugs (see Mensch and Kandel 1988 ). A notable limitation of focusing on marijuana is that it is not obvious that marijuana causes workplace impairment—the key concern of employers—more than other substances.

5 Results for alternative measures of use—such as marijuana intensity—were similar. We exclude individuals with missing or incomplete information on any of the marijuana outcome variables. We do not, however, delete observations where the respondent reports not knowing information about workplace substance use policies. We also create a dummy variable indicating the respondent reported not knowing about the specific policy in question. Throughout, when we control for a particular program or policy, we also control for the associated “don't know” dummy variable.

6 It is also worth noting that the magnitude of the changes in the adjusted odds ratio in Table 3 suggests larger sensitivity to accounting for other workplace characteristics both for having a workplace policy and offering drug education compared to the associated sensitivity of the drug testing coefficient. Also, in results not reported (but available upon request) we found that the statistical significance of the associations between marijuana use and having a written policy or having received drug education is not robust to considering an alternative time period (1994–1998), despite that the significant negative association between workplace drug testing and past month marijuana participation remains.

7 Pinpointing this type of direct job sorting by drug users requires a prospective research design that is beyond the scope of this paper.

8 Results were also insensitive to inclusion of various controls for current smoking behavior, such as a dummy variable indicating the individual is a daily smoker, or the number of cigarettes consumed in the previous month. To the extent that cigarettes proxy for unobservable characteristics related to time preference, this further supports the main findings.

9 This information has been used previously by researchers, but in a relatively limited way; no previous research, for example, has formally tested whether the substance use differential is larger for firms that perform both types of testing than for firms that do one but not the other.

10 For the 1994 NHSDA estimates we excluded all individuals who report they did not know about the employer's testing programs. The firm size cutoffs in the 1994 NHSDA were 25–99 and 100+; to preserve sample size, we chose the 25+threshold.

11 Probably the most persistent type of misreporting regarding employer testing is individuals reporting that they do not know about employer testing. Some researchers have argued that these “don't know” responses should be coded as “no testing” if perceptions about testing are relevant for drug use decisions. Throughout, we have separately controlled for whether the individual does not know about drug testing.

12 Another possible concern is that because the substances commonly tested for under the “NIDA 5” (cannabinoids, cocaine, amphetamines, opiates, and phencyclidine) are known to workers, drug testing could have the unintended consequence of inducing marijuana users to substitute toward other illicit drugs with unknown relative effects on impairment and productivity (e.g., barbiturates).

- Costantinou M. The Drug Testing Industry Is a Multibillion Dollar Profit Center.” San Francisco Chronicle. 2001 August 12. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flynn G. How to Prescribe Drug Testing. Workforce. 1999; 78 (1):107–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- French M, Roebuck M, Alexandre P. To Test or Not to Test: Do Workplace Drug Testing Programs Discourage Employee Drug Use? Social Science Research. 2004; 33 (2004):45–63. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartwell T, Steele P, French M, Rodman N. Prevalence of Drug Testing in the Workplace. Monthly Labor Review. 1996; 119 (11):35–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoffmann J, Larison C. Worker Drug Use and Workplace Drug-Testing Programs: Results from the 1994 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1999; 26 (2):331. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mehay S, Pacula R. The Effectiveness of Workplace Drug Prevention Policies: Does ‘Zero Tolerance. 1999 Work?”, NBER Working Paper 7383. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mensch BS, Kandel DB. Underreporting of Substance Use in a National Longitudinal Cohort. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1988; 52 :100–24. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Research Council, Institute of Medicine. Under the Influence? Drugs and the American Workforce. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Worker Drug Use and Workplace Policies and Programs: Results from the 1994 and 1997 NHSDA. 1999. Office of Applied Studies Analytic Series Paper A-11. [ PubMed ]

Drug testing at the workplace Essay

Corporations, companies and schools should be allowed to randomly drug test their employees because employers have an expectation that they should not be high on drugs. As much as drugs can be used in a recreational manner thereby not interfering with somebody’s job or public safety, this should not be allowed in the workplace.

This implies that employees should not be compromised by anything as far as discharging their duties and responsibilities are concerned (Weber 19). In this case, it is a fact that there is time for everything and that is why employers should be free to drug test their employees to be sure that nothing will be compromised. It should be known that workplace testing has been a contentious issue in many organizations and will therefore continue attracting attention as time goes by.

Random drug testing of employees encourages greater responsibility both to the individual (employee) and others. This means that workers who may cause harm to themselves as a result of taking drugs will be protected as much as the use might be in a recreational manner. In a broad perspective, testing ensures that people do not work under the influence which enhances productivity and efficiency.

People will not feel comfortable if they know that professionals who are attending to them are under the influence of drugs or alcohol in any way. Employees who take drugs engage in this activity at their own will which does not need any interference from employers. All this withstanding, employees should be tested for drugs so that individuals who are in need of any help can be assisted (Weber 31). There are employees who might be having addiction problems and drug testing enhances the need for self reporting and honesty.

There should be properly informed procedures as far as workplace drug testing is concerned to ensure that it is a participatory exercise. This is because random testing will act as a deterrent for other people who might try to regularly use drugs or might be having an intention to experiment with alcohol.

The health of employees should be a great concern for any employer because it has an impact on productivity which is related to positive outcomes that an organization might be anticipating for. In this case, the health and safety of employees is guaranteed in an organization through random drug testing whereby it will discourage people from abusing drugs (Weber 19).

As a matter of fact, this will reduce different incidences of accidents and injuries that might come about as a result of working under the influence. Employers should not control the behavior of their employees in any way which means that everybody should be made to understand the need for random drug testing.

Workplace testing should be allowed in any organization because there are cases where failures by different professionals might be irreversible and substantial. In this case, the costs that an organization might encounter as a result of people working under the influence are always too costly yet this could have been avoided. Organizations should be allowed to drug test employees because it is a way of monitoring them to ensure that they adhere to workplace ethics that enhance productivity.

The issue of random drug testing has taken a different dimension because there are employers who end up discharging employees off their duties if they test positive (Weber 45). Adherence to job requirements does not require people to use drugs and alcohol by pretending that they are being used in a recreational manner which is a fact. Drug testing by organizations should be done in consideration of many factors to ensure that it is all inclusive.

Works Cited

Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. New York: Penguin Books, 2002. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, January 18). Drug testing at the workplace. https://ivypanda.com/essays/drug-testing-at-the-workplace/

"Drug testing at the workplace." IvyPanda , 18 Jan. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/drug-testing-at-the-workplace/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Drug testing at the workplace'. 18 January.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Drug testing at the workplace." January 18, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/drug-testing-at-the-workplace/.

1. IvyPanda . "Drug testing at the workplace." January 18, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/drug-testing-at-the-workplace/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Drug testing at the workplace." January 18, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/drug-testing-at-the-workplace/.

- Hybrid Electric Vehicle Batteries: Charging and Discharging

- Human Rights Violations by Police: Accountable in Discharging Their Duties

- Discharging Minors in a Psychiatric Facility While Parents Feel Unsafe

- Wayco Company's Non-smoking Policy

- Professionalism in Nursing: Concepts & Challenges

- The English Contract Law: Terms and Classification

- Frankenstein Murderer: Hero Analysis and Careful Study of the Case

- Issue of Public Humiliation

- Legal Aspects of Human Resource Management

- Recreational Drugs Use and Legalization

- When the Time to Grow Into a Professional Comes: Trying Out as a Volunteer in a Charity Shop. Experience and Lessons Learned

- Stakeholder Management Strategies and their Design

- Team Work and Motivation

- Leadership in General Electric

- Leadership and Motivation Theories, Principles and Issues

- 5 Panel Drug Test

- 10 Panel Drug Test

- 12 Panel Drug Test

- DOT Drug Testing

- Hair Drug Tests

- Urine Alcohol Tests

- Breath Alcohol Tests

- Employment Drug Testing

- Court-Ordered Drug Testing

- Drugs Tested

- Drug Test Panels

- Alternative DNA Test

- Legal Paternity Test

- Home DNA Test Kit

- Prenatal Paternity Test

- Sibling DNA Test

- Aunt or Uncle DNA Test

- Grandparent DNA Test

- Postmortem DNA Test

- Hair DNA Test

- Triple Database Package

- Court Record Package

- Platinum Package

- Ultimate Package

- Resume Verification

- DOT Background Check

- Occupational Health Locations

- Antibody Testing

- Employment Physical

- Respiratory Health Exam

- Tuberculosis (TB) Testing

- Vision and Hearing

- Drug & DNA Locations

- Marijuana Compliance

- State Laws Compliance

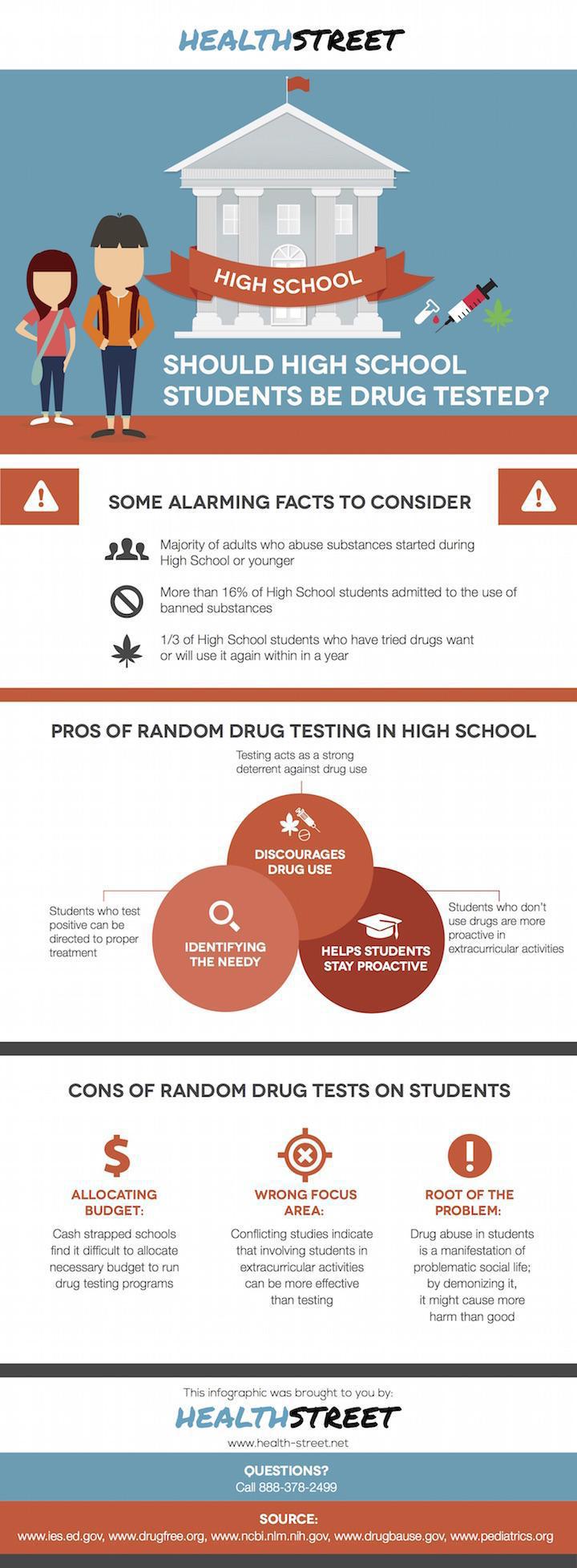

Should High School Students be Drug Tested?

Drug test all high school students to reduce drug use and save lives! Sounds like a slam dunk, right? Upon closer examination, there are both pros and cons to going down this path. Learn the details of the debate.

Register Now

Drug Testing High School Students

It sounded like a great idea when I first heard it: drug test high school students ! Yet it's an idea wrapped in controversy. While substance use has declined over the last decade, almost 10 percent of the nation's teens report the use of illicit drugs within the last month . And like most parents, I'm enormously concerned about the devastating implications of illicit drug use on our adolescents. So, I've attempted to explore both sides of a question that doesn't come with an easy answer.

Pros of Drug Testing High School Students

1. random tests discourage drug use.

If students know they can be subject to drug tests at any time, it's a clear deterrent to partaking in drug use. More subtly, a random drug testing policy can also can aid those kids facing peer pressure to use, or who are on the fence, because it provides them with an easy excuse to say no to drugs.

2. Identifying Students in Need of Help

Drug testing is typically just one component to a larger system. A program combining prevention, intervention, counseling and a treatment plan synergistically work together to help combat students' drug use. And when a student tests positive, it's recommended that schools focus on helping the students deal with their usage rather than punishing them.

3. Evidence Leans Towards Effectiveness

Random drug testing in schools is intended to curb illicit drug use, but the question remains: is it even effective? While reports of effectiveness are conflicting, The Supreme Court has stood by their decision to allow schools to drug test on a random basis. At least one recent study shows that drug testing can, in fact, help. The National Center for Education Evaluation reports that students involved in extracurricular activities in schools that conducted drug testing had less substance use than comparable students from schools without drug testing.

Cons of Testing HS Students

1. the cost of testing.

With schools across the country tightening their budgets, the added expense of drug testing can be daunting for struggling school systems. Sharon Levy of the American Academy of Pediatrics estimates only 1 positive for every 125 students tested, thus equating to a cost of around $3,000 for each positive result. These funds could be earmarked for prevention programs instead.

2. Focusing on The Wrong Area

It's been proven that a student's involvement in extracurricular activities is one of the best ways to prevent drug abuse. By schools turning their focus on engaging their students in a meaningful high school experience, it could open up a greater opportunity to set up their kids for healthy decision-making in all aspects of life. Devoting efforts to this holistic approach might, in the long run, stop more kids from partaking in illicit drugs.

3. Drugs are not the Core Problem

Teenage substance abuse is frequently a manifestation of a child's problematic home life or inability to foster healthy social relations. Teens who are suffering often use drugs as a form of self-medication. By punishing teen users, the potential for academic harm increases, perpetuating an already precarious cycle of drug abuse and low self-esteem. Treatment and prevention should remain the top priority - with or without a complementary drug testing program. In any case, demonizing the students who test positive or moralizing about their behavior is likely to backfire.

So... Should High School Students be Tested for Drugs?