The Philippines: Historical Overview

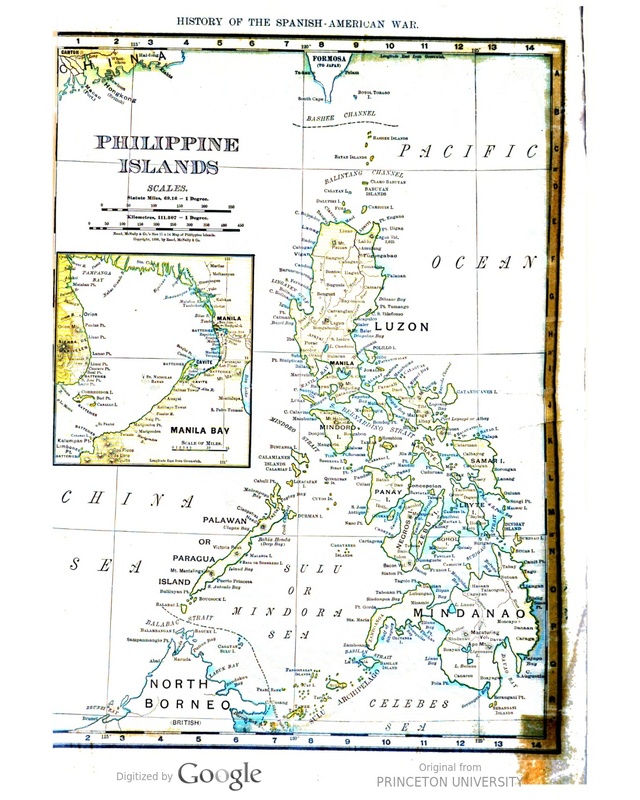

Map of the Philippines from 1898.

Source: History of the Spanish-American War , (New York: the Company, 1898), 2.

The Philippines is an archipelago made up of over 7,000 islands located in Southeast Asia. There are more than 175 ethnolinguistic groups, and over 100 dialects and languages spoken. One of the difficulties of writing a history of the Philippines is that prior to the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century, the people that inhabited the archipelago did not see themselves as a unified political or cultural group. In fact, it was not until the late nineteenth century that a sense of a Philippine nation began to develop.

The first peoples to inhabit the Philippines migrated more than 4,000 years ago from what is today southern China. These peoples did not just populate the Philippines but dispersed throughout Southeast Asia. Historians and anthropologists have been able to trace their early migrations by examining linguistic patterns and have noted the Austronesian origin of most of the languages spoken in the precolonial Philippines and Southeast Asia. Indigenous languages spoken in Indonesia and Malaysia, for example, also share Austronesian roots.[1]

Early settlements of the Philippine archipelago occurred along rivers which kept populations somewhat isolated from one another. Rivers provided natural resources (water and protein via seafood) to sustain small communities. While these settlements were scattered along rivers, they did not develop a political center. Instead, early settlers saw themselves in relation to smaller communities and developed local alliances and allegiances. People were linked to one another through kinship, both biological and fictive, and followed a leader whom they called a datu. Datus emerged as protectors of the group. They used their skills in negotiation and warfare to demand tribute from merchants and maintain their clans. Eventually, these small communities ranging from 30 to 100 households became known as barangays, meaning “boat” in Tagalog, a Philippine language that originates in central Luzon.[2]

When Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the archipelago, specifically to the Visayas region in 1521, he encountered a large network of barangays connected to a broader maritime world in Southeast Asia. Precolonial communities were in contact with other ethnolinguistic groups across the archipelago and beyond through trade and religious exchange. Goods such as rice, spices, aromatics, and other forest products attracted foreign merchants as far as India and China and richly rewarded the datus.[3] In terms of religion, historical evidence shows that precolonial Philippine peoples practiced “animism,” or beliefs and practices that held spirits as immanent to the surrounding world. These religious practices developed through trade networks, which also paved the way for the spread of Islam. Well before the arrival of Christianity, Islam reached the archipelago in the fourteenth century.[4]

It was the Spanish expedition led by Magellan in 1521 that laid the foundations for imagining a Spanish colony in the Philippines. Over the next 50 years, the Spanish crown sent more expeditions to the islands in search of spices and other goods. They named the islands after King Felipe II and aimed to have every datu follow him.[5] In 1565, Miguel Lopez de Legaspi arrived and brought the datu of Cebu in the Visayas to swear allegiance to the Spanish crown. His power over the region was insecure, however. Legaspi then gathered his followers and an army to travel to Maynilad (today known as Manila) to capture the port town from the son of a Luzon datu.[6]

Securing power over local settlements was a long and difficult process occurring over the next century that required both coaxing and coercion. By 1576, the Spanish created many settlements and the population of Spanish men in the region reached over 250.[7] One of their main challenges entailed bringing the indigenous people, who were still living in scattered settlements, under a centralized authority.

Bringing the indigenous population under Spanish rule took many decades of cajoling and relied on different tactics including developing alliances and enticing people through gifts and promises of salvation. Central to this process were the missionary friars who were a part of four main Catholic orders: Augustinians, Franciscans, Jesuits, and Dominicans. These missionary friars were sent to convert the native peoples to Christianity with the promise of Spain’s claim to the archipelago. According to historian John Phelan, “Christianization acted as a powerful instrument of societal control over the conquered people.”[8] Religious conversion through what was called conquista espiritual (“spiritual conquest”) became an important means to subjugate indigenous populations and also persuade them to relocate to political centers in order to facilitate a centralized Spanish rule.

The Spanish friars referred to the relocation process as reducción. As much as reducción was a process of religious conversion, it was also a militarized endeavor that involved violence when the so-called “indios” resisted.[9] A century after the Spanish Reconquista, wherein the Spanish reconquered the Iberian peninsula from Muslim rule, Spanish friars in the Philippines viewed their missionary duty as a continuation of an earlier struggle. The growing presence of Islam in the southern islands of the archipelago proved that the Spanish were destined to provide the natives salvation. They called converts to Islam “Moros” after the Moors they fought in Spain, which discursively connected their religious mission to their previous war of conquest.

Once areas were under Spanish control, the colonial government established an encomienda system that required the local population to pay tribute and perform labor for the colony.[10] A Spanish governor, who was also a military captain, effectively had the power to make decisions for the colony. This was due to the fact that the Philippine islands were so far away from the metropole. Yet, the governor’s power was still limited. The fact that he was also a military captain signals how, even after 300 years of rule, the Spanish never fully had control over the local population and therefore depended on military leadership [11]. Under the governor, provinces were established with a gobernadorcillo ruling each town. The gobernadorcillo enforced the law established by the colonial governor. Under the gobernadorcillo was the cabeza de barangay or the head of barangay who collected taxes locally. At times, the gobernadorcillo and the cabeza de barangay used force to obtain the funds they required from the local people. The Spanish colonial government depended on the collection of tribute to maintain their operations and control the Philippine population.

By the 1850s, the economic prosperity of the native-born population, especially of Chinese mestizos, began to develop into an elite class that rivaled the peninsulares, or the “pure blooded” Spanish in the archipelago (also sometimes known as criollos). By the 1870s, this new elite sent their sons to Manila and Europe for a liberal education and they became known as ilustrados, or “enlightened ones.”[12] Ilustrados began to question the authority of the Spanish friars and publicly critique the poor administration of the Philippine colony. It was this group of elite men that established the Propaganda Movement, based in Manila and Spain, calling for reforms centered on equality between Filipinos, mestizos, and the Spanish.[13] The writings of propagandists, especially that of Jose Rizal, the most famous of the group, inspired the Filipino masses. The views of the majority, however, diverged from those of the elites who advocated mainly for modest reform and representation. The politics of the elite was ultimately considered too moderate from the perspective of a majority who became inspired to revolt against Spain and fight for independence. In 1896, the Philippine revolution began as a radical fight for emancipation from Spanish colonialism and the right to Filipino self-governance.[14]

In 1898, a major event on the other side of the globe stymied the efforts of the Filipino revolutionaries. In April of 1898, the US sent the battleship USS Maine to Havana Harbor, Cuba, in support of Cuban revolutionaries. When the ship exploded killing over 200 Americans, the US government assumed the Spanish were responsible and used the event as a pretext for war. US president William McKinley declared war with Spain in August of 1898, and US troops were shipped to the remaining Spanish possessions, including the Philippines, just two days later.[15] The Filipino revolutionaries could not have predicted such a turn of events that would ultimately affect the outcome of their fight for an independent Philippines.

By the time the American military arrived in April of 1898, the Filipino revolutionaries had successfully gained control over all major cities in the archipelago except for the capital city of Manila. There, the Spanish were protected by a fortress constructed for military protection against outside invaders called Intramuros. Knowing that they were losing the war against the Filipinos, Spanish and US military officers pre-arranged a battle in Manila which excluded Filipino soldiers in order to stage the Spanish defeat. The Spanish orchestrated a mock battle in order to save face and lose the war to the Americans rather than to the Filipinos, whom they believed to be an inferior race.[16] The 1898 Treaty of Paris ended the Spanish-American War and officially transferred ownership of Spain’s remaining colonies to the US.[17]

Filipino revolutionaries continued their fight for independence against the US in the Philippine-American war. Over the next several decades of US rule, the US military and colonial officials attempted to establish control, pacify the local populations, and justify US imperialism in the Philippines. This is where our exhibit begins.

[1] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 20.

[2] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 27.

[3] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 23.

[4] James Francis Warren, The Sulu Zone, 1768-1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State, (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1981).

[5] José S. Arcilla, An Introduction to Philippine History, (Manila: Ateneo Publications, 1971), 11.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 53.

[8] John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565-1700, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1959), 93.

[9] John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines, 44-45.

[10] John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines, 95.

[11] José S. Arcilla, An Introduction to Philippine History, 28.

[12] Edgar Wickberg, The Chinese in Philippine Life, 1850-1898, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965).

[13] John N. Schumacher, The Propaganda Movement, 1880-1895: The Creators of a Filipino Consciousness, the Makers of Revolution, (Manila: Solidaridad Pub. House, 1973).

[14] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 104.

[15] Paul Kramer, The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 78.

[16] Paul Kramer, The Blood of Government, 90.

Essay on Philippines History

Students are often asked to write an essay on Philippines History in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Philippines History

Early history.

Long ago, people from Asia and Borneo came to the Philippines by walking on land bridges. These bridges are now underwater. These people were hunters and gatherers. They used simple tools made from stone and bone.

Trade and Influence

Between 1000 BC and 1521 AD, the Philippines was influenced by many cultures. Traders from India, China, and the Middle East came to the islands. They brought new ideas, goods, and religions. The locals learned to farm, make pottery, and use metal.

Spanish Rule

In 1521, Spanish explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived. Spain took control of the islands and named them the Philippines. The Spanish taught the locals Christianity and Spanish. They ruled for over 300 years.

American Period

In 1898, the US fought Spain and won. The Philippines then became a US territory. The US introduced English and modern education. But many Filipinos wanted independence.

Independence

On July 4, 1946, the Philippines became an independent nation. The country faced many challenges like poverty and corruption. But it also made progress in areas like education and healthcare. Today, the Philippines is a vibrant democracy with a rich history.

250 Words Essay on Philippines History

Long ago, the Philippines was not one country but a group of small islands. People from different parts of Asia came to these islands by boat. These people were hunters and food gatherers. They used simple tools made from stone and wood.

Over time, other people came to the Philippines for trade. They brought new ideas and goods. These people were from China, India, and the Islamic world. They influenced the way of life in the Philippines. The locals learned how to farm, make pottery, and weave cloth.

In 1521, a Spanish explorer named Ferdinand Magellan came to the Philippines. The Spanish wanted to control the islands because of their rich resources. They ruled the Philippines for more than 300 years. The Spanish changed many things. They brought their religion, culture, and law to the islands.

In 1898, the United States took control of the Philippines from Spain. The American rule brought new changes. They improved education, health, and infrastructure. But, many Filipinos wanted independence.

On July 4, 1946, the Philippines became an independent nation. It was a big step for the Filipinos. They could now make their own laws and decisions. But, they also faced many challenges. They had to rebuild the country after World War II.

In short, the history of the Philippines is a mix of different cultures and influences. It is a story of change and growth. The Filipino people have shown resilience and strength in the face of challenges. They continue to strive for a better future.

500 Words Essay on Philippines History

The Philippines is a Southeast Asian country with a rich and complex history. The early history of the Philippines dates back to around 50,000 years ago when the first humans arrived from Borneo and Sumatra via boats. These early people were known as Negritos, who were followed by the Austronesians. The Austronesians introduced farming and fishing techniques to the islands.

In the 10th century, trade began with nearby Asian kingdoms, like the Indianized kingdom of Sri Vijaya and the Chinese Song Dynasty. Traders from these regions brought with them religion, culture, and political ideas. The Philippines was heavily influenced by these cultures, adopting Hindu-Buddhist and Islamic beliefs.

Spanish Colonization

In 1521, the explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the Philippines and claimed the islands for Spain. This marked the start of over 300 years of Spanish rule. The Spanish brought with them Christianity and a new form of government. They built schools, roads, and hospitals, but they also imposed harsh laws and taxes.

American Rule and Independence

After the Spanish-American War in 1898, the Philippines became a territory of the United States. The U.S. introduced democratic governance and a new educational system. Then, on July 4, 1946, the Philippines gained independence, becoming a sovereign nation.

Post-Independence Era

Post-independence Philippines faced several challenges including political instability and economic issues. Ferdinand Marcos, who became president in 1965, declared martial law in 1972. This period, known as the Marcos Era, was marked by human rights abuses and corruption. Marcos was ousted in 1986 through the People Power Revolution, a peaceful protest that marked a significant moment in Philippine history.

Modern Day Philippines

Today, the Philippines is a democratic country with a growing economy. Despite facing issues like poverty and political corruption, it continues to progress. The country’s rich history and diverse culture are reflected in its traditions, festivals, and the warm spirit of its people.

In conclusion, the history of the Philippines is a story of resilience and adaptability. From its early inhabitants to the modern-day Filipinos, the country has navigated through periods of change and challenges, shaping it into the vibrant nation it is today.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Philippines Fun

- Essay on Philippines Culture

- Essay on Philippines Crimes

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- WEB & APPS

- PRIVACY POLICY

- TERMS AND CONDITION

Philippine History: Meaning and relevance of history

Evaluate primary sources for their credibility, authenticity, and provenance

Meaning and relevance of history

It is important to study history because it helps us understand situations in the present. Looking back at past events helps us shape the present and the future. … History is of vital importance to the human race because it primarily recounts the rise and fall of human civilizations.

▪ Etymological Definition: derived from the Greek word, στορία (historia) which means ἱinquiry, knowledge acquired by investigation

▪ Aristotle: A systematic account of a set of natural phenomena

▪ Formal Definition: the study of the past as it is described in written documents (and other sources= oral history)

PHILIPPINE HISTORIOGRAPHY θUnderwent several changes since the precolonial period until present θAncient Filipinos narrated their history through communal songs and epics that they passed orally form a generation to another θSpaniards came, their chroniclers started recording their observations through written accounts. The Spanish colonizers narrated the history of their colony in bipartite view θFilipino historian Zeus Salazar introduced the new guiding philosophy for writing and teaching history: θpantayong pananaw (for us-from us perspective) – this perspective highlights the importance of facilitating an internal conversation an discourse among Filipinos about our own history, using the language that is understood by everyone

Historical Method : examination and analysis of records Historiography: reconstruction of the past from the data (writing or narration)

Historical Research : attempts to systematically recapture the complex nuances, the people, meaning…of the past that have influenced and shaped the present.

Steps in Historical Research

Historical research involves the following steps:

Identify an idea, topic or research question

Conduct a background literature review

Refine the research idea and questions

Determine that historical methods will be the method used

Identify and locate primary and secondary data sources

Evaluate the authenticity and accuracy of source materials

Analyze the date and develop a narrative exposition of the findings.

Historical research relies on a wide variety of sources, both primary & secondary including unpublished material.

Distinction of primary and secondary sources

HISTORICAL SOURCES

Primary sources- sources produced at the same time as the event, period, or subject being studied. ϖeyewitness accounts of convention delegates and their memoirs are used as primary sources ϖArchival documents, artifacts, memorabilia, letters, census, and government records

Secondary sources -sources that are produced by an author who used primary sources to produce the material ϖare historical sources, which studied a certain historical subject

Primary Sources

Eyewitness accounts of events/Can be oral or written testimony

Found in public records & legal documents, minutes of meetings, corporate records, recordings, letters, diaries, journals, drawings. Located in university archives, libraries or privately run collections such as local historical society.

Primary sources help students relate in a personal way to events of the past and promote a deeper understanding of history as a series of human events. Because primary sources are snippets of history, they encourage students to seek additional evidence through research. Primary sources are materials in a variety of formats, created at the time under study.

Primary sources are produced usually by a participant or observer at the time an event or development took place (or even at a later date). Primary sources include manuscripts such as letters, diaries, journals, memos. Newspapers, memoirs, and autobiographies also might function as primary sources. Nonwritten primary sources might be taped interviews, films and videotapes, photographs, furniture, cards, tools, weapons, houses and other artifacts

Original evidence documenting a time period, event, people, idea, or work. Primary sources can be printed materials (such as books and ephemera), manuscript/archival materials (such as diaries or ledgers), audio/visual materials (such as recordings or films), artifacts (such as clothes or personal belongings), or born-digital materials (such as emails or digital photographs). Primary sources can be found in analog, digitized, and born-digital forms.

Secondary Sources

Can be oral or written/Secondhand accounts of events

Found in textbooks, encyclopedias, journal articles, newspapers, biographies and other media such as films or tape recordings.

Secondary source A work synthesizing and/or commenting on primary and/or other secondary sources. Secondary sources, which are often works of scholarship, are differentiated from primary sources by the element of critical synthesis, analysis, or commentary.

EVALUATING HISTORICAL SOURCES

Historians most often use written sources, but audio and visual materials as well as artifacts have become important objects that supply information to modern historians. Numerical data are explained in written form or used in support of a written statement. Historians must be aware of the climate of opinion or shared set of values, assumptions, ideas, and emotions that influence the way their sources are constructed and the way they perceive those sources. In addition, an individual’s own frame of reference– the product of one’s own individual experiences lived–must be acknowledged by the perceptive historian in order to determine the reliability and credibility of a source in relation to others. Good historical writing includes:

- a clear argument that has both logical and persuasive elements

- interpretations that strive to be as objective as possible but openly acknowledging the underlying concerns and assumptions

- something new rather than simply re-hashing the work of other authors–sometimes asking old questions and finding new answers or asking questions which never have been asked

- a response to debates in the field of history, either by challenging or reinforcing the interpretations of other historians evidenced in the footnotes and biography

How to Read a Primary Source

1. Author and Audience:

Who wrote the text (or created the artifact) and what is the author/creator’s place in society? If the person is not well known, try to get clues from the text/artifact itself. Why do you think the author wrote it? How “neutral” is the text; how much does the author have a stake in you reading it, i.e., does the author have an “ax to grind” which might render the text unreliable? What evidence (in the text or artifact) tells you this? People generally do not go to the trouble to record their thoughts unless they have a purpose or design; and the credible author acknowledges and expresses those values or biases so that they may be accounted for in the text.

What is the intended audience of the text or artifact? How does the text reveal the targetted audience?

2. Logic: What is the author’s thesis? How does the creator construct the artifact? What is the strategy for accomplishing a particular goal? Do you think the strategy is effective for the intended audience? Cite specific examples.

What arguments or concerns does the author imply that are not clearly stated? Explain what you think this position may be and why you think it.

3. Frame of Reference:

How do the ideas and values in the source differ from the ideas and values of our age? Give specific examples of differences between your frame of reference and that of the author or creator — either as an individual or as a member of a cultural group.

What assumptions do we as readers bring to bear on this text? See if you can find portions of the text which we might find objectionable, but which contemporaries might have found acceptable.

4. Evaluating Truth Content:

How might this text support one of the arguments found in a historical secondary source? Choose a paragraph anywhere in a secondary source you’ve read, state where this text might be an appropriate footnote (give a full citation), and explain why.

Offer one example of a historical “fact” (something that is indisputable or generally acknowledged as true) that we can learn from this text (this need not be the author’s exact words).

5. Relation to Other Sources:

Compare and contrast the source with another primary source from the same time period. What major similarities? What major differences appear in them?

Which do you find more reliable and credible? Reliability refers to the consistency of the author’s account of the truth. A reliable text displays a pattern of verifiable truth-telling that tends to make the reader trust that the rest of the text is true also. Your task as a historian is to make and justify decisions about the relative veracity of historical texts and portions of them.

Understanding History—A Primer of Historical Method. By Louis Gottschalk.

Unfortunately, not only for the author and the publisher but also for the historical guild, the shortcomings of this volume are both serious and numerous. Itis not well organized, not at all systematic. It lacks perspective, sequence, and coherence. It does not leave with the most careful reader a clear mental picture of the general subject of the volume. In this respect it falls far below the level of Hockett’s Introduction to Research in American History. The work is highly eclectic, a series of short essays, brief comments, and random gatherings. Gottschalk violates at times his own theory and pronouncements. Objectivity, in research and also to some extent in composition, is advocated, but subjectivity is clearly apparent in this treatise. Theories and pronouncements in the treatise are violated, as for example in the mention of items not yet elucidated but consciously deferred for fuller consideration in later pages. Understanding History is not a systematic manual of historical method, but a collection of comments on the subject.

Historical method

It comprises the techniques and guidelines by which historians use primary sources and other evidence to research and then to write histories in the form of accounts of the past. The question of the nature, and even the possibility, of a sound historical method is raised in the philosophy of history as a question of epistemology.

• Human sources may be relics such as a fingerprint; or narratives such as a statement or a letter. Relics are more credible sources than narratives.

• Any given source may be forged or corrupted. Strong indications of the originality of the source increase its reliability.

• If a number of independent sources contain the same message, the credibility of the message is strongly increased.

• The tendency of a source is its motivation for providing some kind of bias.

Historical method 2 External criticism: authenticity and provenance Garraghan divides criticism into six inquiries

1. When was the source, written or unwritten, produced (date)? | 2. Where was it produced (localization)? 3. By whom was it produced (authorship)? 4. From what pre-existing material was it produced (analysis)? 5. In what original form was it produced (integrity)? 6. What is the evidential value of its contents (credibility)?

External and internal criticism

INTERNAL CRITICISM:

aka positive criticism is the attempt of the researcher to restore the meaning of the text. This is the phase of hermeneutics in which the researcher engages with the meaning of the text rather than the external elements of the document.

-Looks at content of the source and examines the circumstances of its production

-Looks at the truthfulness and factuality of the evidence by looking at the author of the source, its context, the agenda behind its creation, the knowledge which informed it, and its intended purpose

-Entails that the historian acknowledge and analyze how such reports can be manipulated to be used as a war propaganda

-Validating historical sources is important because the use of unverified, falsified, and untruthful historical sources can lead to equally false conclusions θWithout thorough criticisms of historical evidences, historical deceptions and lies will all be probable

historical reliability Noting that few documents are accepted as completely reliable, Louis Gottschalk sets down the general rule, “for each particular of a document the process of establishing credibility should be separately undertaken regardless of the general credibility of the author.”

EXTERNAL CRITICISM

The practice of verifying the authenticity of evidence by examining its physical characteristics; consistency with the historical characteristic of the time when it was produced; and the materials used for the evidence.

it sometimes is said that its function is negative, merely saving us from using false evidence; whereas internal criticism has the positive function of telling us how to use authenticated evidence.

Examples of the things that will be examined when conducting external criticism of a document include the quality of the paper, the type of ink, and the language and words used in the material, among others

2. Analyze the context, content, and perspective of different kinds of primary sources

Examples of primary source material include:

· Written materials: speeches, letters, diaries, autobiographies and memoirs, newspapers and magazines published at the time, government documents, maps, laws, advertisements

· Images: photographs, films, fine art

· Audio: oral histories, interviews, music recordings

· Artifacts: clothing, tools, inventions, memorabilia

Where to find primary sources? There are a number of different online collections of primary source documents. If you’re looking for historical primary sources, consider starting your search with these resources.

Primary Source Analysis Guide

Students first identify the author, audience, and historical context of the source. Since an author may have a particular bias or position, it is important to teach students to identify and acknowledge an author’s perspective or point of view as they begin to analyze a primary source.

After identifying the content and context of a primary source, students then work through a four-step analysis process. I guide the students’ thinking with prompts and questions for each step of the process. The four steps and questions are:

· Observe: What do you observe? Consider the images, people, objects, activities, actions, words, phrases, facts, and numbers.

· Explain: What is the meaning of the objects, words, symbols, etc.?

· Infer: What sentiment (attitude or feeling) do you think the author is trying to convey through the source? What, based on the source, can you infer about the historical event or time period?

· Wonder: What about the source makes you curious? What questions still remain? What additional information would you need to know in order to deepen your understanding of the ideas expressed in the source?

As a final step, students summarize the central idea of the source by considering the author’s message and specific supporting details. To support students in this process, I provide them with fill-in-the-blank prompts to concisely state the central idea.

Content and Contextual Analysis of Selected Primary Sources in Philippine History

The historian’s primary tool of understanding and interpreting the past is the historical sources.

Historical sources ascertain historical facts. Such facts are then analyzed and interpreted by the historian to weave historical narrative. Using primary sources in historical research entails two kinds of criticism.

EXTERNAL CRITICISM examines the authenticity of the document or the evidence being used.

INTERNAL CRITICISM examines the truthfulness of the content of the evidence.

A Brief Summary of the First Voyage Around the World by Magellan by Antonio Pigafetta

Who is Antonio Pigafetta? – Famous Italian traveller born in Vicenza around 1490 and died in the same city in 1534, who is also known by the name of Antonio Lombardo or Francisco Antonio Pigafetta. Initially linked to the order of Rhodes, which was Knight, went to Spain in 1519, accompanied by Monsignor Francisco Chiericato, and was made available from Carlos V to promote the company initiated by the Catholic Monarchs in the Atlantic. Soon he became a great friendship with Magallanes, who accompanied, together with Juan Sebastián Elcano, in the famous expedition to the Moluccas begun in August of 1519 and finished in September 1522.

He was wounded at the battle of the island of Cebu (Philippines) in which Magellan found death. The output of Seville made it aboard of the Trinity; the return, along with a handful of survivors (17 of the 239 who left this adventure), in victory, ship that entered in Sanlúcar de Barrameda (Cádiz) on September 6, the designated year. In the last years of his life, he traveled by land from France to finally return to Italy in 1523. He wrote the relation of that trip, which was the first around the world, Italian and with the title of Relazioni in lathe to the primo viaggio di circumnavigazione. Notizia del Mondo Nuovo with figure you dei paesi scoperti, which was published posthumously, in 1536.

The account of Pigafetta is the single most important source about the voyage of circumnavigation, despite its tendency to include fabulous details. He took notes daily, as he mentioned when he realizes his surprise at Spain and see that he had lost a day (due to its driving direction). Includes descriptions of numerous animals, including sharks, the Storm petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus), the pink spoonbill (Ajaja ajaja) and the Phyllium orthoptera, an insect similar to a sheet. Pigafetta captured a copy of the latter near Borneo and kept it in a box, believing a moving blade who lived in the air. His report is rich in ethnographic details. He practiced as an interpreter and came to develop, at least in two Indonesian dialects.

Pigafetta’s work instantly became a classic that prominent literary men in the West like WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, MICHEL de MONTAIGNE, and GIAMBATTISTA VICO referred to the book in their interpretation of the New World. Pigafetta’s travelogue is one of the most important primary sources in the study of the precolonial Philippines.

In Pigafetta’s account, their fleet reached what he called the LADRONES ISLANDS or the “Islands of the Thieves.” He recounted: “These people have no arms, but use sticks, which have a fish bone at the end. They are poor, but ingenious, and great thieves, and for the sake of that we call these three islands the Ladrones Islands.”

The Ladrones Islands

The Ladrones Islands is presently known as the Marianas Islands. Tendays after they have reached Ladrones Islands, Pigafetta reported that they have what he called the Isle of Zamal, now Samar but Magellan decided to land in another uninhabited island for greater security where they could rest for a few days. – On MARCH 18, nine men came to them and showed joy and eagerness in seeing them. Magellan realized that the men were reasonable and welcomed them with food, drinks and gifts.

Pigafetta detailed in amazement and fascination the palm tree which bore fruits called cochos and wine. – He characterized the people as “very familiar and friendly” and willingly showed them different islands and the names of these islands. The fleet went to Humunu Island (Homonhon) and there they found what he referred to as the “Watering Place of Good Signs.” for it is in this place that they found the first signs of gold in the island. They named the island together with a nearby island as the archipelago of St. Lazarus.

On March 25th, Pigafetta recounted that they saw two balanghai (balangay), a long boat full of people in Mazzava/Mazaus. The leader whom he reffered to the king became closely bonded with Magellan as they both exchanged gifts to one another. – After a few days, Magellan was introduced to the king’s brother who was also a king of another island where Pigafetta reported that they saw mines of gold. The gold was abundant that parts of the ship and of the house of the king were made of gold. This king was named Raia Calambu, king of Zuluan and Calagan (Butuan and Caragua), and the first king was Raia Siagu.

On March 31st (Easter Sunday), Magellan ordered the chaplain to preside a Mass by the shore. The king heard about this plan and sent two dead pigs and attended the Mass with the other king. Pigafetta then wrote: “…when the offertory of the mass came, the two kings, went to kiss the cross like us, but they offered nothing, and at the elevation of the body of our Lord they were kneeling like us, and adored our Lord with joined hands.” This was the first Mass in the Philippines, and the cross would be famed Magellan’s Cross which is still preserved at present day. This was the same cross which Magellan explained to the kings as a sign of his emperor who ordered him to plan it in the places were he would reach and further explained that once other Spaniards saw this cross, then they would know that they had been in this island and would not cause them troubles.

By April 7th, Magellan and his men reached the port of Zzubu (Cebu) with the help of Raia Calambu who offered to pilot them in going to the island. The kind of Cebu demanded that they pay tribute as it was customary but Magellan refused. By the next day, Magellan’s men and the king of Cebu, together with other principal men of Cebu, met in an open space. There the king offered a bit of his blood and demanded that Magellan do the same. – On April 14, Magellan spoke to the kind and encouraged him to be a good Christian by burning all of the idols and worship the cross instead. The king of Cebu was then baptized as a Christian. After 8 days, all of the island’s inhabitant were already baptized.

When the queen came to the Mass one day, Magellan gave her an image of the Infant Jesus made by Pigafetta himself. – On 26th of April, Zula, a principal man from the island of Matan (Mactan) went to see Magellan and asked him for a boat full of men so that he would be able to fight the chief name Silapulapu (Lapulapu). Magellan offered 3 boats instead and went to Mactan to fight the said chief. – They numbered 49 in total and the islanders of Mactan were estimated to number 1,500. Magellan died in battle. He was pierced with a poison arrow in his right leg. The king of Cebu who was baptized offered help but Magellan refused so that he could see how they fought. – The kind also offered the people of Mactan gifts of any value and amount in exchange of Magellan’s body but the chief refused and wanted to keep Magellan’s body as a memento of their victory.

Magellan’s men then elected Duarte Barbosa as the new captian. – Pigafetta also accounted how Magellan’s slave and interpreter named Henry betrayed them and told the king of Cebu that they intended to leave as soon as possible. Henry and the king of Cebu conspired and betrayed what was left of Magellan’s men. The king invited these men to a gathering where he said he would present the jewels that he would send for the King of Spain.

Pigafetta was left on board the ship and was not able to join the 24 men who went to the gathering because he was nursing his battle wounds. – The natives had slain all the men except the interpreter and Juan Serrano who shouted at the men on this ship to pay ransom so that he would be spared but he was left on the island for they refused to go back to shore. – The fleet abandoned Serrano and departed. They left Cebu and continued their journey around the world.

The KKK and the “Kartilya ng Katipunan

The Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (KKK) or Katipunan is arguably the most important organization formed in the Philippine history. ϖThe two principal aims of the KKK as gathered from the writings of Bonifacio: 1. Unity of the filipino people

Bonifacio came out after the failure of the reform movement headed by Rizal and M. Del Pilar. This paved way for a more radical and more active lines. He formed the Katipunan, a secret society which was founded at Tondo Manila, in a house on Azcarraga Street then numbered 314, on July 7, 1892, the same date on which Rizal was decreed to be banished to Dapitan.

Rizal doubtless approved the first aim but refused to accept the second and this was the reason that he refused to go along with the “Katipuneros” (soldiers’ of the Katipunan) and voluntarily surrendered that leads him to prison and death. – To achieve unity of the Filipinos, propaganda work must be done and this was through massive education and civic trainings of the Katipuneros. To that end, Bonifacio prepared his now well-known decalogue, and Jacinto his famous “Kartilya ng Katipunan” (Primer of the Katipunan)

These are the rules in Kartilya. The Kartilya can be treated as the Katipunan’s Code of conduct which contains 14 rules that instruct the way a Katipunero should behave.

Below is a translated version of the rules on Kartilya 1. The life that is not consecrated to a lofty and reasonable purpose is a tree without a shade, if not a poisonous weed. 2. To do good for personal gain and not for its own sake is not virtue. 3. It is rational to be charitable and love one’s fellow creature, and to adjust one’s conduct, acts and words to what is in itself reasonable. 4. Whether our skin be black or white, we are all born equal: superiority in knowledge, wealth and beauty are to be understood, but not superiority by nature.

Below is a translated version of the rules on Kartilya 5. The honorable man prefers honor to personal gain; the scoundrel, gain to honor. 6. To the honorable man, his word is sacred. 7. Do not waste thy time: wealth can be recovered but not time lost. 8. Defend the oppressed and fight the oppressor before the law or in the field. 9. The prudent man is sparing in words and faithful in keeping secrets.

Below is a translated version of the rules on Kartilya 10. On the thorny path of life, man is the guide of woman and the children, and if the guide leads to the precipice, those whom he guides will also go there. 11. Thou must not look upon woman as a mere plaything, but as a faithful companion who will share with thee the penalties of life; her (physical) weakness will increase thy interest in her and she will remind thee of the mother who bore thee and reared thee. 12. What thou dost not desire done unto thy wife, children, brothers and sisters, that do not unto the wife, children, brothers and sisters of thy neighbor.

Below is a translated version of the rules on Kartilya 13. Man is not worth more because he is a king, because his nose is aquiline, and his color white, not because he is a *priest, a servant of god, nor because of the high prerogative that he enjoys upon earth, but he is worth most who is a man of proven and real value, who does good, keeps his words, is worthy and honest; he who does not oppress nor consent to being oppressed, he who loves and cherishes his fatherland, though he be born in the wilderness and know no tongue but his own. 14. When these rules of conduct shall be known to all, the longed-for sun of liberty shall rise brilliant over this most unhappy portion of the globe and its rays shall diffuse everlasting joy among the confederated brethren of the same rays, the lives of those who have gone before, the fatigues and the well-paid sufferings will remain. If he who desires to enter (the katipunan) has informed himself of all this and believes he will be able to perform what will be his duties, he may fill out

28. An Excerpt from the Second Paragraph of the Kartilya which states that “The object pursued by this association is great and precious: to unite in ideas and purposes all filipinos by means of a strong oath and from union derive force with which to tear the veil that obscures intelligence and thus find the true path of reason and light” – The strong oath was documented and signed with the signed with the blood of the “Katipuneros” (blood (blood compact). They swore at the Katipunan creed; Katipunan creed; to defend the oppressed, fight the fight the oppressor even to the extent of supreme self- supreme self- sacrifice.

29. An Excerpt from the Second Paragraph of the Kartilya which states that – One of the most important Katipunan documents was the Kartilya ng Katipunan. – The original title of the document was “Manga (sic) Aral Nang (sic) Katipunan ng mga A.N.B.” Or “Lesson of the Organization of the Sons of Country”.

Reading “The Proclamation of the Philippine Independence”

– June 12, 1898 – The Philippine Declaration of independence was proclaimed in Cavite el Viejo (presentday Kawit, Cavite) – Filipino revolutionary forces under General Emilio Aguinaldo proclaimed the sovereignty and independence of the Philippine Islands from the colonial rule of Spain.

– 1896 – the Philippine Revolution began. Eventually, the Spanish signed an agreement with the revolutionaries – Emilio Aguinaldo went into exile in Hongkong. At the outbreak of the Spanish-American war.

Commodore George Dewey – sailed from Hong Kong to Manila Bay leading a squadron of U.S. Navy ships. – May 1, 1898 – the United States defeated the Spanish in the Battle of Manila Bay. – the U.S. Navy transported Aguinaldo back to the Philippines.

THE PROCLAMATION ON JUNE 12 Independence was proclaimed on June 12, 1898 between four and five in the afternoon in Cavite at the ancestral home of General Emilio Aguinaldo. – The event saw the unfurling of the National Flag of the Philippines, made in Hong Kong by Marcela Agoncillo, Lorenza Agoncillo, and Delfina Herboza.

THE PROCLAMATION ON JUNE 12 – and the performance of the Marcha Filipina Magdalo, as the national anthem, now known as Lupang Hinirang, which was composed by Julián Felipe and played by the San Francisco de Malabon marching band. – The Act of the Declaration of Independence was prepared, written, and read by Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista in Spanish.

THE PROCLAMATION ON JUNE 12

– The Declaration was signed by ninety-eight people, among them an American army officer who witnessed the proclamation who attended the proceedings, Mr. L. M. Johnson, a Coronel of Artillery. – The proclamation of Philippine independence was, however, promulgated on 1 August, when many towns had already been organized under the rules laid down by the Dictatorial Government of General Aguinaldo

The declaration was not recognized by the U.S. nor Spain and Spain later sold the Philippines to the United States in the 1898 Treaty of Paris ended the Spanish-American War. – Philippine-American War – The Philippine Revolutionary Government did not recognize the treaty or American sovereignty, and subsequently fought and lost a conflict with United States.

Ended when Emilio Aguinaldo was captured by U.S. forces, and issued a statement acknowledging and accepting the sovereignty of the United States over the Philippines. – Following World War II, the US granted independence to the Philippines on July 4, 1946 via the Treaty of Manila.

Treaty of Paris, (1898)

1964 – President Diosdado Macapagal signed into law Republic Act No. 4166 designating June 12 as the country’s Independence Day.

Raiders of the Sulu Seas

The History channel showed a documentary about what was claimed then as pirates of the Sulu seas from Mindanao, Philippines. The documentary was on how these raiders were actually plying their trade before and during the Spanish colonization of the Philippines. This bit of history would not have been taught and learned from Philippine history subjects in school.

The Spanish established their colony on the southern tip of Mindanao in Zamboanga. Fort Pilar was constructed with ten (10) meter-high wall fortification all around. This was the base of the Spaniards to facilitate their trade. Zamboanga is very close to Basilan, the Tawi-tawi and Sulu group of islands and the Maguindanao area where there we three different tribes of seafaring Filipino Muslims. The three tribes were known as Balangingi-Samal, Ilanuns and Sultanate of Sulu, all which were employing Taosogs who were excellent warriors.

The three tribes are not really pirates during the times they were plying their trade of capturing people and selling them as slaves. Slave trading was a business then and they were not raiding ships in high seas. What they did was go and land in different shores posing as fishermen. Without any warning, draw their 1-meter long swords and take as many slaves as they can. Once captured, the slaves’ palms are punctured and tied to each other. The slaves are loaded in their 25 to 27 meter by 6 meter boats that has 30 to 34 oarsmen and sails. It was said that their boats were the fastest that Spanish Galleons could not even give chase.

The History documentary was actually focusing on how the tribes were able to organize a flotilla of a hundred ships or more with more than 3,000 men. This happened when the three tribes connived to raid Fort Pilar. The Spanish were stricken with fear upon seeing the number of boats and the army they were to face.

How were the hundred or more boats gathered? Well, the three tribes had some sort of a pact on how to go about their business and employing Taosogs as their warriors. One tribe could set out to sea with a few boats then drop-by each of the several bases of the tribes along the shores. They would call upon all available seafarers to join the expedition. As they go along, their numbers grow.

The slavery trade of the three tribes ended only when the Spaniards ordered three steamboats from England. The steamboats were faster, easier to navigate and had various armaments to take on the tribes. Spaniards were now able to chase and follow the boats to their bases and conduct raids. It was said that the conflict between the tribes and the Spaniards did not stem from business or trade but was more on belief, religious belief.

1.Distrinction of primary and secondary sources 2. Analyze the context, content, and perspective of different kinds of primary sources 3. Determine the contribution of different kinds of primary sources in understanding Philippine history 4. Develop critical and analytical skills with exposure to primary sources 5. Demonstrate the ability to use primary sources to argue in favor or against a particular issue 6. Effectively communicate, using various techniques and genres, their historical analysis of a particular event or issue that could help others understand the chosen topic. Propose, recommendations/solutions to present-day problems based on their understanding of root causes and their anticipation of future scenarios 8. Display the ability to work in a team and contribute to a group project 9. Manifest interest in local history and concern in promoting and preserving our country’s national patrimony and cultural heritage Course Outline: Content and contextual analysis of selected primary sources, identification of the historical importance of the text; and examination of the author’s main argument and point of view “One past but many histories”: controversies and conflicting views in Philippine history a. Site of the First Mass b. Cavite Mutiny d. Cry of Balintawak or Pugadlawin 10. Social, political, economic and cultural issues 1. Agrarian Reform Policies 11. The Philippine Constitution: 1899 (Malolos) Constitution; 1935 Constitution; 1973 Constitution; 1987 Constitution 12. Taxation Critical evaluation and promotion of local and oral history, museums, historical shrines, cultural performances, indigenous practices, religious rites and rituals, etc.

Customs of the Tagalogs -Juan de Plasencia In 1589, if we are to put socio-political context into the text (These are interrelated threads that probably constitute major segments of colonial historical writing in the Philippines.) 1.the issue of authorship 2. the discourse of power in colonial writing 3. the logic of binarism or the Occident-Other dichotomy.

The authorial voice or authorship plays a pivotal role in putting meaning(s) to this colonial text. The author, Juan de Plasencia was, in the first place, not a native Tagalog but a Franciscan missionary who first arrived in the Philippines in 1577. He was tasked by the King of Spain to document the customs and traditions of the colonized (“natives”) based on, arguably, his own observations and judgments. Notably, de Plasencia wrote the Doctrina Cristiana, an early book on catechism and is believed to be the first book ever printed in the Philippines. Such initiatives were an accustomed practice of the colonizer during the Age of Discovery to enhance their superiority over the colonized and validity of their so-called duties and legacies to the World. It is a common fact that during this era, the Spanish colonizers, spearheaded by missionaries, drew a wide variety of texts ranging from travel narratives and accounts of the colony to even sermons.

Born to the illustrious family of Portocarreros in Plasensia in the region of Extremadura, Spain in the early 16th century. He was one of the seven children of Pedro Portocarrero, a captain of a Spanish schooner. Fray Joan de Puerto Carrero, del convento de Villanueva de la Serena. Was his real name.

Purpose: Relacion de las Costumbres and Instruccion. To put an end to some injustices being committed against the natives by certain government officials.

Chieftain (Datu) Nobles (Maharlika) Commoners (Aliping Namamahay) Slaves (Aliping Saguiguilir) Social Classes; datu Chief, captain of wars, whom governed. Nobles or maharlika ¬ Free-born, they do not pay taxes. Commoners or aliping namamahay ¬ They live in their own houses and lords of their property and gold. Slaves or aliping sa guiguilir ¬ They serve their master in his house and his cultivated lands and can be sold.

Houses ✣ Made of wood, bamboo, and nipa palm. Government ✣ The unit of government is called Barangay ruled by a chieftain, and consist of 30 to 100 families together with their relatives and slaves. 18

Inheritance ✣ The 1st son of the barangay chieftain inherits his father’s position; if the 1st son dies, the 2nd son succeeds their father; in the absence of male heirs, it is the eldest daughter that becomes the chieftain. 20

Slaves ✣ A person becomes slave by: (1) by captivity in war, (2) by reason of debt, (3) by inheritance, (4) by purchase, and (5) by committing a crime. ✣ Slaves can be emancipated through: (1) by forgiveness, (2) by paying debt, (3) by condonation, and (4) by bravery (where a slave can possibly become a Datu) or by marriage.21

Religious Belief ✣ They worship many gods and goddesses: (1) bathala, supreme being; (2) Idayanale, god of agriculture; (3) Sidarapa, god of death; (4) Agni, god of fire; (5) Balangaw, god of rainbow; (6) Mandarangan, god of war; (7) Lalahon, god of harvest; and (8) Siginarugan, god of hell. ✣ Also believe in sacred animals and tress. 23

Superstitious Beliefs ✣ Believe in Aswang, Dwende, Kapre, Tikbalang, Patyanak/Tiyanak. ✣ They also believe in magical power of amulet and charms such as anting-anting, kulam and gayuma or love potion.

Economic Life ✣ Agriculture in the plane lands: planting of rice, corn, banana, coconut, sugar canes and other kinds of vegetable and fruits. ✣ Hunting in high lands. ✣ Fishing in river banks and sea. ✣ Shipbuilding, weaving, poultry, mining and lumbering. ✣ Domestic trade of different barangays by boat. ✣ Foreign trade with countries like Borneo, China, Japan, Cambodia, Java, and Thailand.

Language and System of Writing ✣ Major languages: Tagalog, Ilocano, Pangasinan, Pangpangan, Sugbuhanon, Hiligaynon, Magindanaw and Samarnon this languages is originated from the Malayo-Polenisian language. ✣ System of writing: the alphabets consisted of 3 vowels and 14 consonants called Baybayi. ✣ They used tap of tress as ink and pointed stick as pencil. ✣ They wrote on large plant leaves, bark of a tree or bamboo tubes.

Kartilya ng Katipunan ni Emilio Jacinto

1. Ang buhay na hindi ginugugol sa isang malaki at banal na kadahilanan ay kahoy na walang lilim, kundi damong makamandag.

2. Ang gawang magaling na nagbuhat sa paghahambog o pagpipita sa sarili, at hindi talagang nasang gumawa ng kagalingan, ay di kabaitan.

3. Ang tunay na kabanalan ay ang pagkakawang-gawa, ang pag-ibig sa kapwa at ang isukat ang bawat kilos, gawa’t pangungusap sa talagang Katuwiran.

4. Maitim man o maputi ang kulay ng balat, lahat ng tao’y magkakapantay; mangyayaring ang isa’y hihigtan sa dunong, sa yaman, sa ganda…; ngunit di mahihigtan sa pagkatao.

5. Ang may mataas na kalooban, inuuna ang puri kaysa pagpipita sa sarili; ang may hamak na kalooban, inuuna ang pagpipita sa sarili kaysa sa puri.

6. Sa taong may hiya, salita’y panunumba.

7. Huwag mong sayangin ang panahon; ang yamang nawala’y mangyayaring magbalik; ngunit panahong nagdaan ay di na muli pang magdadaan.

8. Ipagtanggol mo ang inaapi; kabakahin ang umaapi.

9. Ang mga taong matalino’y ang may pag-iingat sa bawat sasabihin; matutong ipaglihim ang dapat ipaglihim.

10. Sa daang matinik ng buhay, lalaki ang siyang patnugot ng asawa at mga anak; kung ang umaakay ay tungo sa sama, ang pagtutunguhan ng inaakay ay kasamaan din.

11. Ang babae ay huwag mong tingnang isang bagay na libangan lamang, kundi isang katuwang at karamay sa mga kahirapan nitong buhay; gamitin mo nang buong pagpipitagan ang kanyang kahinaan, at alalahanin ang inang pinagbuharan at nag-iwi sa iyong kasanggulan.

12. Ang di mo ibig gawin sa asawa mo, anak at kapatid, ay huwag mong gagawin sa asawa, anak at kapatid ng iba.

Emilio Aguinaldo: Gunita ng Himagsikan

Between 1928 and 1946, he produced in long hand the first volume of his memoirs, “Mga Gunita ng Himagsikan (1964),” translated from the original Tagalog as “Memoirs of the Revolution” (1967). In his preface Aguinaldo says the memoirs were based on a diary he kept, documents he preserved, and family lore gathered from his elders. We do not know whether this diary is extant or whether a promised second volume of the memoirs were fully written out. All we have is an account from his birth and early years, ending with the 1897 Treaty of Biak-na-Bato.

The second volume would cover the resumption of the Philippine Revolution against Spain and the Philippine-American War. Aguinaldo wanted to correct history by making reference to the historian’s confused accounts on the beginning of the Revolution: “Except for those that were written, other details had been forgotten. Many details showed inconsistencies because not all sources were documented for lack of reliable references. For instance, the right day of the First Cry of Balintawak could not be ascertained. Some say this took place on August 23, 1896 at the old Bonifacio Monument in Balintawak, others claim it happened on August 24, 1896. . . . we now have too many markers for a single event.”

National historical institute documents of the 1898 declaration of philippine independence the malolos constitution and the first republic ph

Malolos Constitution

A committee headed by Felipe Calderon and aided by Cayetano Arellano, the constitution was drafted, for the first time by representatives of the Filipino people and it is the first republican constitution in Asia. The constitution was inspired by the constitutions of Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Brazil, Belgium and France. After some minor revisions (mainly due to the objections of Apolinario Mabini ), the final draft of the constitution was presented to Aguinaldo. This paved the way to launching the first Philippine Republic. It established a democratic, republication government with three branches – the Executive, Legislative and the Judicial branches. It called for the separation of church and state. The executive powers were to be exercise by the president of the republic with the help of his cabinet. Judicial powers were given to the Supreme Court and other lower courts to be created by law. The Chief justice of the Supreme Court was to be elected by the legislature with the concurrence of the President and his Cabinet.

First Philippine Republic

The first Philippine Republic was inaugurated in Malolos, Bulacan on January 21, 1899. After being proclaimed president, Emilio Aguinaldo took his oath of office. The constitution was read article by article and followed by a military parade. Apolinario Mabini was elected as a prime minister. The other cabinet secretaries were: Teodoro Sandico, interior; Baldomero Aguinaldo, war; Gen. Mariano Trias, finance & war; Apolinario Mabini, foreign affairs; Gracio Gonzaga for welfare, Aguedo Velarde, public instruction; Maximo Paterno, public works & communication; and Leon María Guerrero for agriculture, trade & commerce.

Corazon Aquino: Speech before the US Congress (Sept. 18, 1986)

Who is the author of the primary source? What do you know about the author that may shape his/her perspective? Corazon Aquino was the author of the primary source. She is known as the wife of the oppositionist of Ferdinand Marcos. She showed her mutiny and sadness through addressing the speech when she finally got the chance in the US Congress. Who is the intended audience of the primary source? The intended audience of the primary source is the Filipino people, as well as the whole world who witnessed the impoverishment of the Marcos’ administration; students, researchers, political analysts.

Where and when was the primary source published or created? She delivered her speech before the Joint session of the United States Congress with U.S lawmaker in September 18, 1986.

Describe the historical context. What was happening during this event of time period? It has been known by everyone that the Marcos-Aquino families greatly hates each other. Ninoy Aquino, the husband of Cory and the number one oppositionist of Ferdinand Marcos was detained in the North. Ninoy’s captivation and assassination on the latter part much fuelled Cory’s determination to fight against the government and seek refuge from the Americans.

“Still, we fought for honor, and, if only for honor, we shall pay.” -She emphasized that the fight that they started was not wasted and it was not a nonsense one. That they, the Filipinos put up a good fight against the administration.

“The task had fallen on my shoulders to continue offering the democratic alternative to our people.” -She took the responsibilities in taking care and fighting for the sake of freedom of the whole country.

* Cory Aquino was devastated and sad about the situation of the country; about the two decades of social and political oppression.

Filipino version of the Cavite Mutiny of 1872 Dr. Trinidad Hermenigildo Pardo de Tavera , a Filipino scholar and researcher, wrote the Filipino version of the bloody incident in Cavite. In his point of view, the incident was a mere mutiny by the native Filipino soldiers and laborers of the Cavite arsenal who turned out to be dissatisfied with the abolition of their privileges. Indirectly, Tavera blamed Gov. Izquierdo’s cold-blooded policies such as the abolition of privileges of the workers and native army members of the arsenal and the prohibition of the founding of school of arts and trades for the Filipinos, which the general believed as a cover-up for the organization of a political club.

On 20 January 1872, about 200 men comprised of soldiers, laborers of the arsenal, and residents of Cavite headed by Sergeant Lamadrid rose in arms and assassinated the commanding officer and Spanish officers in sight. The insurgents were expecting support from the bulk of the army unfortunately, that didn’t happen. The news about the mutiny reached authorities in Manila and Gen. Izquierdo immediately ordered the reinforcement of Spanish troops in Cavite. After two days, the mutiny was officially declared subdued.

Tavera believed that the Spanish friars and Izquierdo used the Cavite Mutiny as a powerful lever by magnifying it as a full-blown conspiracy involving not only the native army but also included residents of Cavite and Manila, and more importantly the native clergy to overthrow the Spanish government in the Philippines. It is noteworthy that during the time, the Central Government in Madrid announced its intention to deprive the friars of all the powers of intervention in matters of civil government and the direction and management of educational institutions. This turnout of events was believed by Tavera, prompted the friars to do something drastic in their dire sedire to maintain power in the Philippines.

Meanwhile, in the intention of installing reforms, the Central Government of Spain welcomed an educational decree authored by Segismundo Moret promoted the fusion of sectarian schools run by the friars into a school called Philippine Institute. The decree proposed to improve the standard of education in the Philippines by requiring teaching positions in such schools to be filled by competitive examinations. This improvement was warmly received by most Filipinos in spite of the native clergy’s zest for secularization.

The friars, fearing that their influence in the Philippines would be a thing of the past, took advantage of the incident and presented it to the Spanish Government as a vast conspiracy organized throughout the archipelago with the object of destroying Spanish sovereignty. Tavera sadly confirmed that the Madrid government came to believe that the scheme was true without any attempt to investigate the real facts or extent of the alleged “revolution” reported by Izquierdo and the friars.

Convicted educated men who participated in the mutiny were sentenced life imprisonment while members of the native clergy headed by the GOMBURZA were tried and executed by garrote. This episode leads to the awakening of nationalism and eventually to the outbreak of Philippine Revolution of 1896. The French writer Edmund Plauchut’s account complimented Tavera’s account by confirming that the event happened due to discontentment of the arsenal workers and soldiers in Cavite fort. The Frenchman, however, dwelt more on the execution of the three martyr priests which he actually witnessed.

Unraveling the Truth

Considering the four accounts of the 1872 Mutiny, there were some basic facts that remained to be unvarying:

1. There was dissatisfaction among the workers of the arsenal as well as the members of the native army after their privileges were drawn back by Gen. Izquierdo;

2. Gen. Izquierdo introduced rigid and strict policies that made the Filipinos move and turn away from Spanish government out of disgust;

3. Central Government failed to investigate on what truly transpired but relied on reports of Izquierdo and the friars and the opinion of the public;

4. The happy days of the friars were already numbered in 1872 when the Central Government in Spain decided to deprive them of the power to intervene in government affairs as well as in the direction and management of schools prompting them to commit frantic moves to extend their stay and power;

5. The Filipino clergy members actively participated in the secularization movement in order to allow Filipino priests to take hold of the parishes in the country making them prey to the rage of the friars;

6. Filipinos during the time were active participants, and responded to what they deemed as injustices; and Lastly, the execution of GOMBURZA was a blunder on the part of the Spanish government, for the action severed the ill-feelings of the Filipinos and the event inspired Filipino patriots to call for reforms and eventually independence.

1872 Cavite Mutiny: Spanish Perspective

Jose Montero y Vidal, a prolific Spanish historian documented the event and highlighted it as an attempt of the Indios to overthrow the Spanish government in the Philippines.

Gov. Gen. Rafael Izquierdo ’s official report magnified the event and made use of it to implicate the native clergy, which was then active in the call for secularization. The two accounts complimented and corroborated with one other, only that the general’s report was more spiteful. Initially, both Montero and Izquierdo scored out that the abolition of privileges enjoyed by the workers of Cavite arsenal such as non-payment of tributes and exemption from force labor were the main reasons of the “revolution” as how they called it, however, other causes were enumerated by them including the Spanish Revolution which overthrew the secular throne, dirty propagandas proliferated by unrestrained press, democratic, liberal and republican books and pamphlets reaching the Philippines, and most importantly, the presence of the native clergy who out of animosity against the Spanish friars, “conspired and supported” the rebels and enemies of Spain. In particular, Izquierdo blamed the unruly Spanish Press for “stockpiling” malicious propagandas grasped by the Filipinos. He reported to the King of Spain that the “rebels” wanted to overthrow the Spanish government to install a new “hari” in the likes of Fathers Burgos and Zamora. The general even added that the native clergy enticed other participants by giving them charismatic assurance that their fight will not fail because God is with them coupled with handsome promises of rewards such as employment, wealth, and ranks in the army. Izquierdo, in his report lambasted the Indios as gullible and possessed an innate propensity for stealing.

The two Spaniards deemed that the event of 1872 was planned earlier and was thought of it as a big conspiracy among educated leaders, mestizos, abogadillos or native lawyers, residents of Manila and Cavite and the native clergy. They insinuated that the conspirators of Manila and Cavite planned to liquidate high-ranking Spanish officers to be followed by the massacre of the friars. The alleged pre-concerted signal among the conspirators of Manila and Cavite was the firing of rockets from the walls of Intramuros.

According to the accounts of the two, on 20 January 1872, the district of Sampaloc celebrated the feast of the Virgin of Loreto, unfortunately participants to the feast celebrated the occasion with the usual fireworks displays. Allegedly, those in Cavite mistook the fireworks as the sign for the attack, and just like what was agreed upon, the 200-men contingent headed by Sergeant Lamadrid launched an attack targeting Spanish officers at sight and seized the arsenal.

When the news reached the iron-fisted Gov. Izquierdo, he readily ordered the reinforcement of the Spanish forces in Cavite to quell the revolt. The “revolution” was easily crushed when the expected reinforcement from Manila did not come ashore. Major instigators including Sergeant Lamadrid were killed in the skirmish, while the GOMBURZA were tried by a court-martial and were sentenced to die by strangulation. Patriots like Joaquin Pardo de Tavera, Antonio Ma. Regidor, Jose and Pio Basa and other abogadillos were suspended by the Audencia (High Court) from the practice of law, arrested and were sentenced with life imprisonment at the Marianas Island. Furthermore, Gov. Izquierdo dissolved the native regiments of artillery and ordered the creation of artillery force to be composed exclusively of the Peninsulares.

On 17 February 1872 in an attempt of the Spanish government and Frailocracia to instill fear among the Filipinos so that they may never commit such daring act again, the GOMBURZA were executed. This event was tragic but served as one of the moving forces that shaped Filipino nationalism.

Ricardo P. Garcia: The Great Debate: Rizal Retraction

“Acts of Faith, Hope, and Charity” reportedly recited and signed by Dr. Rizal as attested by “witnesses” and a signed Prayer Book. This is very strong testimony if true, for Rizal was giving assent to Roman Catholic teaching not in a general way as in the case of the Retraction statement but specifically to a number of beliefs which he had previously repudiated. According to the testimony of Father Balaguer, following the signing of the Retraction a prayer book was offered to Rizal. “He took the prayer book, read slowly those acts, accepted them, took the pen and saying ‘Credo’ (I believe) he signed the acts with his name in the book itself.” (16) What was it Rizal signed? It is worth quoting in detail the “Act of Faith.”

TEXT OF THE RETRACTION DOCUMENT DISCOVERED BY FATHER GARCIA IN 1935

I declared myself a Catholic and in this Religion in which I was born and educated I want to live and die.

I retract with all my heart how much in my words, writings, printed matter and conduct there has been contrary to my quality as a son of the Catholic Church. I believe and profess how much she teaches and I submit to the room she commands. Abomination of Masonry, as an enemy of the Church, and as a society prohibited by the Church. May the Diocesan Couple, as the Superior Ecclesiastical Authority, make public this spontaneous manifestation of mine to repair the scandal that my actions may have caused and for God and men to forgive me.

Cry of Pugad Lawin -Pio Valenzuela The”Cry of Pugad Lawin” was a cry for freedom. Its historic significance to us consists of the realization that the Filipino people had finally realized the lasting value of freedom and independence and the need to fight in order to prove themselves worthy to be called a truly free people

The term “Cry” is translated from the Spanish el grito de rebelion (cry of rebellion) or el grito for short. Thus the Grito de Balintawak is comparable to Mexico’s Grito de Dolores . However, el grito de rebelion strictly refers to a decision or call to revolt. It does not necessarily connote shouting, unlike the Filipino sigaw.

The news of the discovery of the Katipunan spread throughout Manila and the suburbs. Bonifacio, informed of the discovery, secretly instructed his runners to summon all the leaders of the society to a general assembly to be held on August 24. They were to meet at Balintawak to discuss the steps to be taken to meet the crisis. That same night of August 19, Bonifacio, accompanied by his brother Procopio, Emilio Jacinto, Teodoro Plata, and Aguedo del Rosario, slipped through the cordon of Spanish sentries and reached Balintawak before midnight.

Pio Valenzuela followed them the next day. On the 21st, Bonifacio changed the Katipunan code because the Spanish authorities had already deciphered it. In the afternoon of the same day, the rebels, numbering about 500, left Balintawak for Kangkong, where Apolonio Samson, a Katipunero, gave them food and shelter. In the afternoon of August 22, they proceeded to Pugadlawin. The following day, in the yard of Juan A. Ramos, the son of Melchora Aquino who was later called the “Mother of the Katipunan”, Bonifacio asked his men whether they were prepared to fight to the bitter end.

Despite the objection of his brother-in-law, Teodoro Plata, all assembled agreed to fight to the last. “That being the case, ” Bonifacio said, “bring out your cedulas and tear them to pieces to symbolize our determination to take up arms!” The men obediently tore up their cedulas, shouting “Long live the Philippines!” This event marked the so-called “Cry of Balintawak,” which actually happened in Pugadlawin.

The Cry of Balintawak: First Skirmishes

In the midst of this dramatic scene, some Katipuneros who had just arrived from Manila and Kalookan shouted “Dong Andres! The civil guards are almost behind us, and will reconnoiter the mountains.” Bonifacio at once ordered his men to get ready for the expected attack of the Spaniards. Since they had inferior arms the rebels decided, instead, to retreat. Under cover of darkness, the rebels marched towards Pasong Tamo, and the next day, August 24, they arrived at the yard of Melchora Aquino, known as Tandang Sora. It was decided that all the rebels in the surrounding towns be notified of the general attack on Manila on the night of August 29, 1896.

At ten in the morning of August 25, some women came rushing in and notified Bonifacio that the civil guards and some infantrymen were coming. Soon after, a burst of fire came from the approaching Spaniards. The rebels deployed and prepared for the enemy. In the skirmish that followed, the rebels lost two men and the enemy one. Because of their inferior weapons, which consisted mostly of bolos and a few guns, the rebels decided to retreat. On the other hand, the Spaniards, finding themselves greatly outnumbered, also decided to retreat. So both camps retreated and thus prevented a bloody encounter. This was the first skirmish fought in the struggle for national emancipation.