- AI Generator

142 Science Hypothesis Stock Photos & High-Res Pictures

Browse 142 science hypothesis photos and images available, or start a new search to explore more photos and images..

Advertisement

Three Famous Hypotheses and How They Were Tested

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

Key Takeaways

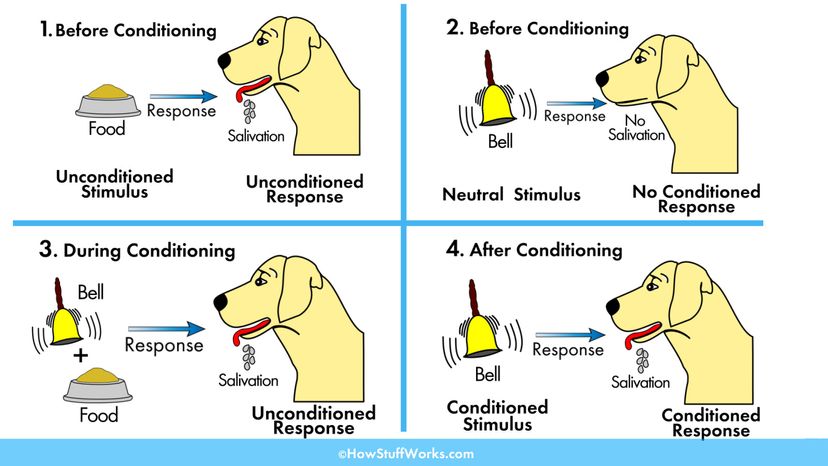

- Ivan Pavlov's experiment demonstrated conditioned responses in dogs.

- Pavlov's work exemplifies the scientific method, starting with a hypothesis about conditioned responses and testing it through controlled experiments.

- Pavlov's findings not only advanced an understanding of animal physiology but also laid foundational principles for behaviorism, a major school of thought in psychology that emphasizes the study of observable behaviors.

Coho salmon ( Oncorhynchus kisutch ) are amazing fish. Indigenous to the Pacific Northwest, they begin their lives in freshwater streams and then relocate to the open ocean. But when a Coho salmon reaches breeding age, it'll return to the waterway of its birth , sometimes traveling 400 miles (644 kilometers) to get there.

Enter the late Arthur Davis Hasler. While an ecologist and biologist at the University of Wisconsin, he was intrigued by the question of how these creatures find their home streams. And in 1960, he used a Hypothesis-Presentation.pdf">basic tenet of science — the hypothesis — to find out.

So what is a hypothesis? A hypothesis is a tentative, testable explanation for an observed phenomenon in nature. Hypotheses are narrow in scope — unlike theories , which cover a broad range of observable phenomena and draw from many different lines of evidence. Meanwhile, a prediction is a result you'd expect to get if your hypothesis or theory is accurate.

So back to 1960 and Hasler and those salmon. One unverified idea was that Coho salmon used eyesight to locate their home streams. Hasler set out to test this notion (or hypothesis). First, he rounded up several fish who'd already returned to their native streams. Next, he blindfolded some of the captives — but not all of them — before dumping his salmon into a faraway stretch of water. If the eyesight hypothesis was correct, then Hasler could expect fewer of the blindfolded fish to return to their home streams.

Things didn't work out that way. The fish without blindfolds came back at the same rate as their blindfolded counterparts. (Other experiments demonstrated that smell, and not sight, is the key to the species' homing ability.)

Although Hasler's blindfold hypothesis was disproven, others have fared better. Today, we're looking at three of the best-known experiments in history — and the hypotheses they tested.

Ivan Pavlov and His Dogs (1903-1935)

Isaac newton's radiant prisms (1665), robert paine's revealing starfish (1963-1969).

The Hypothesis : If dogs are susceptible to conditioned responses (drooling), then a dog who is regularly exposed to the same neutral stimulus (metronome/bell) before it receives food will associate this neutral stimulus with the act of eating. Eventually, the dog should begin to drool at a predictable rate when it encounters said stimulus — even before any actual food is offered.

The Experiment : A Nobel Prize-winner and outspoken critic of Soviet communism, Ivan Pavlov is synonymous with man's best friend . In 1903, the Russian-born scientist kicked off a decades-long series of experiments involving dogs and conditioned responses .

Offer a plate of food to a hungry dog and it'll salivate. In this context, the stimulus (the food) will automatically trigger a particular response (the drooling). The latter is an innate, unlearned reaction to the former.

By contrast, the rhythmic sound of a metronome or bell is a neutral stimulus. To a dog, the noise has no inherent meaning and if the animal has never heard it before, the sound won't provoke an instinctive reaction. But the sight of food sure will .

So when Pavlov and his lab assistants played the sound of the metronome/bell before feeding sessions, the researchers conditioned test dogs to mentally link metronomes/bells with mealtime. Due to repeated exposure, the noise alone started to make the dogs' mouths water before they were given food.

According to " Ivan Pavlov: A Russian Life in Science " by biographer Daniel P. Todes, Pavlov's big innovation here was his discovery that he could quantify the reaction of each pooch by measuring the amount of saliva it generated. Every canine predictably drooled at its own consistent rate when he or she encountered a personalized (and artificial) food-related cue.

Pavlov and his assistants used conditioned responses to look at other hypotheses about animal physiology, as well. In one notable experiment, a dog was tested on its ability to tell time . This particular pooch always received food when it heard a metronome click at the rate of 60 strokes per minute. But it never got any food after listening to a slower, 40-strokes-per-minute beat. Lo and behold, Pavlov's animal began to salivate in response to the faster rhythm — but not the slower one . So clearly, it could tell the two rhythmic beats apart.

The Verdict : With the right conditioning — and lots of patience — you can make a hungry dog respond to neutral stimuli by salivating on cue in a way that's both predictable and scientifically quantifiable.

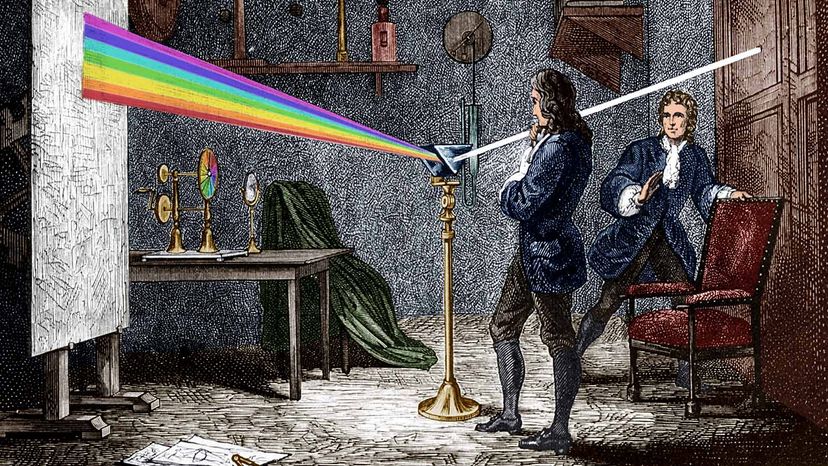

The Hypothesis : If white sunlight is a mixture of all the colors in the visible spectrum — and these travel at varying wavelengths — then each color will refract at a different angle when a beam of sunlight passes through a glass prism.

The Experiments : Color was a scientific mystery before Isaac Newton came along. During the summer of 1665, he started experimenting with glass prisms from the safety of a darkened room in Cambridge, England.

He cut a quarter-inch (0.63-centimeter) circular hole into one of the window shutters, allowing a single beam of sunlight to enter the place. When Newton held up a prism to this ray, an oblong patch of multicolored light was projected onto the opposite wall.

This contained segregated layers of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet light. From top to bottom, this patch measured 13.5 inches (33.65 centimeters) tall, yet it was only 2.6 inches (6.6 centimeters) across.

Newton deduced that these vibrant colors had been hiding within the sunlight itself, but the prism bent (or "refracted") them at different angles, which separated the colors out.

Still, he wasn't 100 percent sure. So Newton replicated the experiment with one small change. This time, he took a second prism and had it intercept the rainbow-like patch of light. Once the refracted colors entered the new prism, they recombined into a circular white sunbeam. In other words, Newton took a ray of white light, broke it apart into a bunch of different colors and then reassembled it. What a neat party trick!

The Verdict : Sunlight really is a blend of all the colors in the rainbow — and yes, these can be individually separated via light refraction.

The Hypothesis : If predators limit the populations of the organisms they attack, then we'd expect the prey species to become more common after the eradication of a major predator.

The Experiment : Meet Pisaster ochraceus , also known as the purple sea star (or the purple starfish if you prefer).

Using an extendable stomach , the creature feeds on mussels, limpets, barnacles, snails and other hapless victims. On some seaside rocks (and tidal pools) along the coast of Washington state, this starfish is the apex predator.

The animal made Robert Paine a scientific celebrity. An ecologist by trade, Paine was fascinated by the environmental roles of top predators. In June 1963, he kicked off an ambitious experiment along Washington state's Mukkaw Bay. For years on end, Paine kept a rocky section of this shoreline completely starfish-free.

It was hard work. Paine had to regularly pry wayward sea stars off "his" outcrop — sometimes with a crowbar. Then he'd chuck them into the ocean.

Before the experiment, Paine observed 15 different species of animals and algae inhabiting the area he decided to test. By June 1964 — one year after his starfish purge started — that number had dropped to eight .

Unchecked by purple sea stars, the barnacle population skyrocketed. Subsequently, these were replaced by California mussels , which came to dominate the terrain. By anchoring themselves to rocks in great numbers, the mussels edged out other life-forms. That made the outcrop uninhabitable to most former residents: Even sponges, anemones and algae — organisms that Pisaster ochraceus doesn't eat — were largely evicted.

All those species continued to thrive on another piece of shoreline that Paine left untouched. Later experiments convinced him that Pisaster ochraceus is a " keystone species ," a creature who exerts disproportionate influence over its environment. Eliminate the keystone and the whole system gets disheveled.

The Verdict : Apex predators don't just affect the animals that they hunt. Removing a top predator sets off a chain reaction that can fundamentally transform an entire ecosystem.

Contrary to popular belief, Pavlov almost never used bells in his dog experiments. Instead, he preferred metronomes, buzzers, harmoniums and electric shocks.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can a hypothesis become a theory, what's the difference between a hypothesis and a prediction.

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Biology library

Course: biology library > unit 1, the scientific method.

- Controlled experiments

- The scientific method and experimental design

Introduction

- Make an observation.

- Ask a question.

- Form a hypothesis , or testable explanation.

- Make a prediction based on the hypothesis.

- Test the prediction.

- Iterate: use the results to make new hypotheses or predictions.

Scientific method example: Failure to toast

1. make an observation..

- Observation: the toaster won't toast.

2. Ask a question.

- Question: Why won't my toaster toast?

3. Propose a hypothesis.

- Hypothesis: Maybe the outlet is broken.

4. Make predictions.

- Prediction: If I plug the toaster into a different outlet, then it will toast the bread.

5. Test the predictions.

- Test of prediction: Plug the toaster into a different outlet and try again.

- If the toaster does toast, then the hypothesis is supported—likely correct.

- If the toaster doesn't toast, then the hypothesis is not supported—likely wrong.

Logical possibility

Practical possibility, building a body of evidence, 6. iterate..

- Iteration time!

- If the hypothesis was supported, we might do additional tests to confirm it, or revise it to be more specific. For instance, we might investigate why the outlet is broken.

- If the hypothesis was not supported, we would come up with a new hypothesis. For instance, the next hypothesis might be that there's a broken wire in the toaster.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- AI Generator

142 Science Hypothesis Stock Photos & High-Res Pictures

Browse 142 science hypothesis photos and images available, or start a new search to explore more photos and images..

- AI Generator

zoo hypothesis

Hypothesis graphic, hypothesis testing, hypothesis test, value hypothesis, hypothesis icon, medical hypothesis, science hypothesis, 859 hypothesis stock photos and high-res pictures, browse 859 authentic hypothesis stock photos, high-res images, and pictures, or explore additional zoo hypothesis or hypothesis graphic stock images to find the right photo at the right size and resolution for your project..

What is a scientific hypothesis?

It's the initial building block in the scientific method.

Hypothesis basics

What makes a hypothesis testable.

- Types of hypotheses

- Hypothesis versus theory

Additional resources

Bibliography.

A scientific hypothesis is a tentative, testable explanation for a phenomenon in the natural world. It's the initial building block in the scientific method . Many describe it as an "educated guess" based on prior knowledge and observation. While this is true, a hypothesis is more informed than a guess. While an "educated guess" suggests a random prediction based on a person's expertise, developing a hypothesis requires active observation and background research.

The basic idea of a hypothesis is that there is no predetermined outcome. For a solution to be termed a scientific hypothesis, it has to be an idea that can be supported or refuted through carefully crafted experimentation or observation. This concept, called falsifiability and testability, was advanced in the mid-20th century by Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper in his famous book "The Logic of Scientific Discovery" (Routledge, 1959).

A key function of a hypothesis is to derive predictions about the results of future experiments and then perform those experiments to see whether they support the predictions.

A hypothesis is usually written in the form of an if-then statement, which gives a possibility (if) and explains what may happen because of the possibility (then). The statement could also include "may," according to California State University, Bakersfield .

Here are some examples of hypothesis statements:

- If garlic repels fleas, then a dog that is given garlic every day will not get fleas.

- If sugar causes cavities, then people who eat a lot of candy may be more prone to cavities.

- If ultraviolet light can damage the eyes, then maybe this light can cause blindness.

A useful hypothesis should be testable and falsifiable. That means that it should be possible to prove it wrong. A theory that can't be proved wrong is nonscientific, according to Karl Popper's 1963 book " Conjectures and Refutations ."

An example of an untestable statement is, "Dogs are better than cats." That's because the definition of "better" is vague and subjective. However, an untestable statement can be reworded to make it testable. For example, the previous statement could be changed to this: "Owning a dog is associated with higher levels of physical fitness than owning a cat." With this statement, the researcher can take measures of physical fitness from dog and cat owners and compare the two.

Types of scientific hypotheses

In an experiment, researchers generally state their hypotheses in two ways. The null hypothesis predicts that there will be no relationship between the variables tested, or no difference between the experimental groups. The alternative hypothesis predicts the opposite: that there will be a difference between the experimental groups. This is usually the hypothesis scientists are most interested in, according to the University of Miami .

For example, a null hypothesis might state, "There will be no difference in the rate of muscle growth between people who take a protein supplement and people who don't." The alternative hypothesis would state, "There will be a difference in the rate of muscle growth between people who take a protein supplement and people who don't."

If the results of the experiment show a relationship between the variables, then the null hypothesis has been rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis, according to the book " Research Methods in Psychology " (BCcampus, 2015).

There are other ways to describe an alternative hypothesis. The alternative hypothesis above does not specify a direction of the effect, only that there will be a difference between the two groups. That type of prediction is called a two-tailed hypothesis. If a hypothesis specifies a certain direction — for example, that people who take a protein supplement will gain more muscle than people who don't — it is called a one-tailed hypothesis, according to William M. K. Trochim , a professor of Policy Analysis and Management at Cornell University.

Sometimes, errors take place during an experiment. These errors can happen in one of two ways. A type I error is when the null hypothesis is rejected when it is true. This is also known as a false positive. A type II error occurs when the null hypothesis is not rejected when it is false. This is also known as a false negative, according to the University of California, Berkeley .

A hypothesis can be rejected or modified, but it can never be proved correct 100% of the time. For example, a scientist can form a hypothesis stating that if a certain type of tomato has a gene for red pigment, that type of tomato will be red. During research, the scientist then finds that each tomato of this type is red. Though the findings confirm the hypothesis, there may be a tomato of that type somewhere in the world that isn't red. Thus, the hypothesis is true, but it may not be true 100% of the time.

Scientific theory vs. scientific hypothesis

The best hypotheses are simple. They deal with a relatively narrow set of phenomena. But theories are broader; they generally combine multiple hypotheses into a general explanation for a wide range of phenomena, according to the University of California, Berkeley . For example, a hypothesis might state, "If animals adapt to suit their environments, then birds that live on islands with lots of seeds to eat will have differently shaped beaks than birds that live on islands with lots of insects to eat." After testing many hypotheses like these, Charles Darwin formulated an overarching theory: the theory of evolution by natural selection.

"Theories are the ways that we make sense of what we observe in the natural world," Tanner said. "Theories are structures of ideas that explain and interpret facts."

- Read more about writing a hypothesis, from the American Medical Writers Association.

- Find out why a hypothesis isn't always necessary in science, from The American Biology Teacher.

- Learn about null and alternative hypotheses, from Prof. Essa on YouTube .

Encyclopedia Britannica. Scientific Hypothesis. Jan. 13, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/science/scientific-hypothesis

Karl Popper, "The Logic of Scientific Discovery," Routledge, 1959.

California State University, Bakersfield, "Formatting a testable hypothesis." https://www.csub.edu/~ddodenhoff/Bio100/Bio100sp04/formattingahypothesis.htm

Karl Popper, "Conjectures and Refutations," Routledge, 1963.

Price, P., Jhangiani, R., & Chiang, I., "Research Methods of Psychology — 2nd Canadian Edition," BCcampus, 2015.

University of Miami, "The Scientific Method" http://www.bio.miami.edu/dana/161/evolution/161app1_scimethod.pdf

William M.K. Trochim, "Research Methods Knowledge Base," https://conjointly.com/kb/hypotheses-explained/

University of California, Berkeley, "Multiple Hypothesis Testing and False Discovery Rate" https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~hhuang/STAT141/Lecture-FDR.pdf

University of California, Berkeley, "Science at multiple levels" https://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/0_0_0/howscienceworks_19

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rare magnitude 4.8 and 3.8 earthquakes rock Northeast, including greater New York area

Underwater robot in Siberia's Lake Baikal reveals hidden mud volcanoes — and an active fault

Longest eclipse ever: How scientists rode the supersonic Concorde jet to see a 74-minute totality

How to draw your research with simple scientific illustrations

Turn sketchbook ideas into scientific masterpieces: a student’s journey

You know the phrase. A picture speaks a 1000 words.

And often, a research paper speaks for much longer than it really needs to. SEVERAL thousand words more beyond what you may want to know. So why don’t we try and make your long story short with your very own scientific illustrations and infographics? And the good news is that you don’t need to be a fancy high-level artist to draw for YOUR science.

Not a Picasso? No problem! But you could be a Da Vinci - most people know him as a famous painter, but he was equally versed in the sciences.

Let us take you through the process of becoming a scientist just like him, one step at a time.

In this blog, Dr. Juan Miguel Balbin, Science Communicator at Animate Your Science, talks about his experiences and life lessons growing up with a sketchbook, and the fundamentals of making simple scientific illustrations to add visibility to your research.

The boy with a sketchbook, now a scientist with a lab book

As a scientist you’ve gone through school. Several levels of school more than what you originally intended. For now let’s cast our minds back to primary school (or elementary for our global readers!). We all had a pencil case with several coloured pencils, broken and blunt ones, and maybe some notes you’d sneakily pass around in class.

For me, I had a sketchbook in there that was just a little bigger than the size of my hand.

Artist lesson #1 : No piece of art in the world is completely original

I liked to draw, but I wasn’t the best at it. I had friends who could draw hyperrealistic animals or put together entire comic book strips. Me? I wasn’t super original. I’d draw characters from my favourite video games or TV shows growing up. But I always felt like I was “copying” from something that already existed. Was I a fraud because I couldn’t come up with my own unique ideas? Little did I know at the time that every artist “copies” and dare I say “steals” ideas as inspiration for their own style. It’s only human to be influenced.

So anyone can draw if your imagination is up for the task!

Artist lesson #2 : Start doodling with a simple medium that’s accessible to you

Eventually my sketchbook ran out of pages, so I wondered if I could go digital. I first tinkered a lot with Microsoft Paint (the classic one that needed Windows XP or older!) as well as Microsoft PowerPoint. These were great starting points for someone wanting to test out digital art and to learn about bitmap vs vector graphics .

Artist lesson #3 : Refine your way of drawing with new tools as you progress

In the end, doodles in Paint and PowerPoint could only go so far when it came to looking professional. So, in high school I picked up classes for Adobe Illustrator (AI) which was industry-standard stuff in graphic design. AI was a fantastic tool to equip myself with to really get that polished look in my work.

But one thing didn’t change. I still drew very simple things, just using new toys.

Artist lesson #4 : Thinking like a scientist makes art easier

I realised that I had a very methodological way of drawing where I would reverse-engineer an image in my mind and list the shapes it was made up of. Wait, was this how an artist thinks? I wasn’t sure. Perhaps this style of thinking paved the way for me on the path to becoming a scientist with a little bit of art and graphic design under my belt. Take the Twitter bird for example!

Artist lesson #5 : If you can draw, you fill a very special niche on a team

Fast forward to University, and I came across the concept of scientific posters. I had a group assignment where we needed to make a poster about insecticide resistance in moths. Nobody else wanted to be responsible for making the poster, so I put my hand up for the job. My group was thankful for someone with a graphic design skillset. I didn’t know what a poster was really meant to look like, except that it shouldn’t be an intimidating wall of text where you would have to squint to see the Size 8 No Spacing Times New Roman.

Instead, we filled it up half-way with pictures and catchy titles while giving a good oral commentary. No intimidating text, just a gigantic moth in the middle of the poster (apologies to those with a phobia!). We scored a very high mark, and it set the bar high for every science poster after.

Artist lesson #6 : Art is your ticket to a good first impression

Heading into my PhD, I was being trained to be a clear and concise scientist. Creativity was gauged on research novelty, not by how prettily I could label up some tubes. What was an artist doing here? Then came my first lab meeting where I presented my initial project proposal. I’ve seen everyone else do theirs, but I wanted to try something different - my own way.

My slides had colourful illustrations of genetically-modified malaria parasites that I would engineer to glow green and red - this was the moment I made my artwork known to my research group and they loved it! However for more formal seminars, the “traditional” slides were needed. Yes that meant reverting back to a bunch of statistics and references. Oh well.

Artist lesson #7 : A story is told better when you use art to show what’s happening

The next step was to present at scientific conferences and excite people with my research! But how could I possibly do this with a project that had mostly negative results? Why was hypothesis A wrong? Because of reasons B and C? How could I tell people this was really hard? With little data on me, I sought to fill up the gaps in my posters and PowerPoints with visual introductions to my topic, drawn schematics of my experiments and used these to tell my story.

And it worked well. Really well.

My storytelling worked well enough to be awarded two prizes at two separate events for the same seemingly basic research project. You don’t need to cure cancer or make a Da Vinci-level painting to make an impact, I certainly didn’t. There’s room for artists of all skill levels in science.

Hopefully at this point you’ve been inspired to give scientific illustrations a try! Let’s now talk about the process of making your graphics and why scientists might hesitate to give drawing a go. I guarantee your next grant or presentation will be GLOWING with these tips.

Identify what shapes make up your research object

“but i haven’t got any drawing skills”.

If you can draw basic shapes, you’re all set. Really, that’s it, plus a healthy dose of imagination. Basic shapes form the basis of any complicated (or simple) drawing.

Okay sure, maybe an owl’s a bit too much. But you can see it’s just made up of a million different shapes. And just like any science experiment there’s method to the madness, so hold on to your pencil and paper. What shapes make up your “owl”?

Let’s draw a cell for example, a red blood cell (my specialty!). A simple red circle is a good place to start. But then you go back into Google Images and find that these cells aren’t just red circles, they’ve got some dimension to them, with a little bit of a dip in the center. So, draw another red circle, but make it a little darker to make it fancy.

Voila! You now have a mostly medically-accurate red blood cell. Of course, you could always add more details, but the point is that beauty lies in simplicity, and science loves to keep things clear, concise and simple . But simple doesn’t need to mean boring and made in a rush. See our article on graphical abstracts to see why you don’t rush these things.

So no, we’re not drawing owls unless you specifically work on owls. Be relieved.

“My work is too complicated for me to turn into a picture.”

In that case, let’s make it less complicated by using symbols.

Symbols are easy to understand and will allow your audience to quickly get a hold on the topic you’re presenting. You can use symbols to illustrate your literature review, methodology, or even as icons for your dot points. Let’s try and make these, using shapes.

microscope (circles and rectangles)

chemical flask (triangles and rectangles)

viral particle (triangles in an icosahedron)

leaf (pointy oval)

atomic models (three ovals and circles)

For researchers who work on more abstract or non-tangible topics, we’ll have to be a little more creative. But this is the fun part! Allow me to introduce metaphorical symbols - your new best friend. These represent broader concepts and methods that could closely tie with your topic and methods. Take these for example.

magnifying glass (representing “investigation”, circles and rectangles)

gears (representing “mechanisms”, circles and squares)

keys (representing the keys to “unlocking the unknown”, circles and rectangles)

thought bubble (representing “hypotheses”, circles)

stopwatch (representing “time needed for a study”, circles and rectangles)

lightbulb (representing “novelty”, circles, rectangles and lines)

ladder (representing “progression”, rectangles)

stick figures (representing “participants”, you know how to make this!)

check boxes (representing “tasks” in your study, squares and rectangles)

Once you have your individual symbols together, you could display them as a scientific infographic like this.

Then give yourself a pat on the back, you’ve earned it for making your first set of scientific illustrations!

“I don’t know what software to use to make my drawings”

Worry not, you likely already have something you can use! Many researchers love to use Microsoft PowerPoint to arrange figures because they’ve already been trained in it. PowerPoint is a fantastic starting point for making illustrations using the Insert shape tool.

Levelling up past PowerPoint? Try out InkScape for free to gain that edge in your vector artwork. We also recommend Affinity Designer which you can access with a one-time payment! Affinity Designer allows you to tinker with both bitmap and vector graphics for that added flexibility.

The holy grail is definitely the Adobe Creative Suite of software products, including Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator and Adobe InDesign. For starters, try out Illustrator! A free trial is available, so give it a try before you commit to a subscription!

“I haven’t got the time to learn to make these myself”

Understandable, completely understandable. Though I would bet that if you’re reading this blog right now that you would be keen to give it a try with some trial and error.

There are also online resources, such as BioRende r , which provide you with base illustrations that you can move around and assemble into a figure yourself.

Alternatively, we’re at your beck and call. Have a look at our gallery to get an idea of the services we provide so we could draw your research for you!

Other tips for new venturing scientific illustrators

An illustration is only good if it can be easily understood! Pair it with an equally descriptive figure legend and/or very clear labels.

Visibility is everything - make sure it is suitably large for your purpose, and is coloured in a way that matches the palette for your poster/presentation etc.

Your pictures tell a story , but they need you to narrate them. Use your illustrations as a tool to better structure your oral narrative.

Once you’re confident with illustrating, why not breathe life into them in a video abstract or animation ?

Take-away points

Every artist starts out simple!

You can draw anything if you can pick out what shapes to use to make an image.

You can tell a story by drawing simple symbols and icons.

We’re only at the tip of the iceberg with what you could do to make scientific illustrations. If you found this blog useful, perhaps you'd consider subscribing to our newsletter ?

Until next time!

Dr Juan Miguel Balbin

Dr Tullio Rossi

#scientificillustration #Twitter

Related Posts

How to design an effective graphical abstract: the ultimate guide

How to Make Cool Animated Science Videos in PowerPoint

How to Select a Great Colour Scheme for Your Scientific Poster

- Images home

- Editorial home

- Editorial video

- Premium collections

- Entertainment

- Premium images

- AI generated images

- Curated collections

- Animals/Wildlife

- Backgrounds/Textures

- Beauty/Fashion

- Buildings/Landmarks

- Business/Finance

- Celebrities

- Food and Drink

- Healthcare/Medical

- Illustrations/Clip-Art

- Miscellaneous

- Parks/Outdoor

- Signs/Symbols

- Sports/Recreation

- Transportation

- All categories

- Shutterstock Select

- Shutterstock Elements

- Health Care

Browse Content

- Sound effects

PremiumBeat

- PixelSquid 3D objects

- Templates Home

- Instagram all

- Highlight covers

- Facebook all

- Carousel ads

- Cover photos

- Event covers

- Youtube all

- Channel Art

- Etsy big banner

- Etsy mini banner

- Etsy shop icon

- Pinterest all

- Pinterest pins

- Twitter All

- Twitter Banner

- Infographics

- Zoom backgrounds

- Announcements

- Certificates

- Gift Certificates

- Real Estate Flyer

- Travel Brochures

- Anniversary

- Baby Shower

- Mother's Day

- Thanksgiving

- All Invitations

- Party invitations

- Wedding invitations

- Book Covers

- About Creative Flow

- Start a design

AI image generator

- Photo editor

- Background remover

- Collage maker

- Resize image

- Color palettes

Color palette generator

- Image converter

- Creative AI

- Design tips

- Custom plans

- Request quote

- Shutterstock Studios

- Data licensing

0 Credits Available

You currently have 0 credits

See all plans

Image plans

With access to 400M+ photos, vectors, illustrations, and more. Includes AI generated images!

Video plans

A library of 28 million high quality video clips. Choose between packs and subscription.

Music plans

Download tracks one at a time, or get a subscription with unlimited downloads.

Editorial plans

Instant access to over 50 million images and videos for news, sports, and entertainment.

Includes templates, design tools, AI-powered recommendations, and much more.

Search by image

Scientific Hypothesis Examples

- Scientific Method

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

A hypothesis is an educated guess about what you think will happen in a scientific experiment, based on your observations. Before conducting the experiment, you propose a hypothesis so that you can determine if your prediction is supported.

There are several ways you can state a hypothesis, but the best hypotheses are ones you can test and easily refute. Why would you want to disprove or discard your own hypothesis? Well, it is the easiest way to demonstrate that two factors are related. Here are some good scientific hypothesis examples:

- Hypothesis: All forks have three tines. This would be disproven if you find any fork with a different number of tines.

- Hypothesis: There is no relationship between smoking and lung cancer. While it is difficult to establish cause and effect in health issues, you can apply statistics to data to discredit or support this hypothesis.

- Hypothesis: Plants require liquid water to survive. This would be disproven if you find a plant that doesn't need it.

- Hypothesis: Cats do not show a paw preference (equivalent to being right- or left-handed). You could gather data around the number of times cats bat at a toy with either paw and analyze the data to determine whether cats, on the whole, favor one paw over the other. Be careful here, because individual cats, like people, might (or might not) express a preference. A large sample size would be helpful.

- Hypothesis: If plants are watered with a 10% detergent solution, their growth will be negatively affected. Some people prefer to state a hypothesis in an "If, then" format. An alternate hypothesis might be: Plant growth will be unaffected by water with a 10% detergent solution.

- Scientific Hypothesis, Model, Theory, and Law

- What Are the Elements of a Good Hypothesis?

- What Is a Hypothesis? (Science)

- Understanding Simple vs Controlled Experiments

- Six Steps of the Scientific Method

- What Is a Testable Hypothesis?

- Null Hypothesis Definition and Examples

- What Are Examples of a Hypothesis?

- How To Design a Science Fair Experiment

- Null Hypothesis Examples

- What 'Fail to Reject' Means in a Hypothesis Test

- Middle School Science Fair Project Ideas

- Effect of Acids and Bases on the Browning of Apples

- High School Science Fair Projects

- How to Write a Science Fair Project Report

The corpse of an exploded star and more — March’s best science images

The month’s sharpest science shots, selected by Nature ’s photo team.

By Emma Stoye

Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Image Processing: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF’s NOIRLab), M. Zamani & D. de Martin (NSF’s NOIRLab)

Supernova shot . Astronomers captured this stunning 1.3-gigapixel image of the Vela supernova remnant — the remains of a star that exploded more than 10,000 years ago — using the telescope-mounted Dark Energy Camera (DECam) at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. Images taken through several DECam filters, each of which allows through distinct wavelengths of light, were combined to produce the bright colours. The resulting photo — DECam’s highest-resolution picture so far — shows the interwoven plumes of dust and gas in unprecedented detail.

Credit: New England Aquarium

Rare sighting . Researchers conducting an aerial survey off the coast of New England have spotted a grey whale ( Eschrichtius robustus ) — a species thought to have been almost extinct from the Atlantic Ocean since the eighteenth century — diving and resurfacing. The animal’s presence could be explained by climate change : sea ice usually prevents these whales from crossing the Northwest Passage, which connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean. But in the past few years, the passage has been largely free of ice during the Northern Hemisphere summer. “These sightings of grey whales in the Atlantic serve as a reminder of how quickly marine species respond to climate change, given the chance,” says Orla O’Brien, a marine biologist at the New England Aquarium in Boston, Massachusetts.

Credit: J. Baker et al. / Nat. Hum. Behav. ; Collection PACEA

Dental decorations . These adornments made from the teeth of animals, including bears, elk and foxes, were crafted by Gravettian hunter-gatherers — the culture responsible for the iconic Venus of Willendorf figurine. Researchers analysed thousands of personal ornaments, along with genetic data of the people buried at the same sites. They found that the variety in jewellery styles couldn’t be explained fully by how far apart populations lived, and identified nine distinct cultural groups that existed in Europe between 34,000 and 24,000 years ago. These groups aligned mostly with the genetic data. However, the study also revealed more-nuanced patterns, indicating that culture and genetics are interconnected but not perfectly aligned.

Credit: Adrees Latif/Reuters

Wind-driven wildfire . This drone shot of trees reduced to ash in Hemphill County, Texas, shows the aftermath of the Smokehouse Creek fire , the biggest wildfire ever recorded in the state. The blaze ripped through an area of more than 400,000 hectares and took three weeks to control. Unusually warm and gusty weather conditions allowed it to spread rapidly, prompting evacuations and destroying homes, power lines and other infrastructure.

Credit: Seung Hye Yang

SpaceX spiral . This galaxy-like ‘SpaceX spiral’ was photographed over Iceland in early March , against a backdrop of the Northern Lights. The phenomenon is caused by sunlight bouncing off frozen crystals of excess fuel as they are jettisoned by a spinning rocket. The rocket — a SpaceX Falcon 9 that had blasted off from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California — released more than 50 small satellites into low Earth orbit before burning up in the atmosphere over the Barents Sea.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Driving test . Three small Moon rovers have been put through a series of rigorous tests to demonstrate their ability to drive autonomously and function as a team without explicit commands from operators. The rovers will be deployed on a future Moon mission and used to map and explore the lunar surface using ground-penetrating radar. To check that the rovers can tolerate the demands of space travel and Moon-like conditions, researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, subjected them to ‘shake and bake’ testing, with extreme temperatures and intense vibration, as well as monitoring their performance in a vacuum chamber. “Now we know these rovers are ready to show what a team of little space robots can accomplish together,” says JPL engineer Subha Comandur.

Credit: Miguel Lo Bianco/Reuters

Ancient art . Researchers think that wall paintings in an Argentinian cave called Cueva Huenul 1 could be thousands of years older than previously estimated, a finding that would make them the oldest cave art in Patagonia — a region that covers the southern tip of South America. Radiocarbon dating of some of the plant-based pigments used to draw abstract shapes suggests that some of the art was created up to 8,200 years ago. Scientists think that the drawings could have been a way for many generations of people to share information at a time when very dry conditions in Patagonia presented a challenge for hunter-gatherers.

Credit: Ryan Stalker/ British Wildlife Photography Awards

Hitching a ride . This shot of a drifting football that has been colonized below the waterline by goose barnacles was the overall winner of the 2024 British Wildlife Photography Awards . “Although the ball is waste and should not be in the sea, I do wonder about the journey the ball has been on,” says the competition entry from photographer Ryan Stalker. “From initially being lost, then spending time in the tropics where the barnacles are native and perhaps years in the open ocean before arriving in Dorset.”

Credit: Ael Kermarec/AFP/Getty

Ongoing eruption . A fresh eruption on Iceland’s Reykjanes Peninsula drew crowds of spectators as molten lava flowed out of a new ground fissure on 16 March and headed towards the nearby town of Grindavík. Researchers have been monitoring volcanic activity in the area closely — several eruptions have taken place over the past few months, including a January event that resulted in lava entering the town itself .

Snack time . Photographer Marilyn Taylor won the London Camera Exchange Photographer of the Year competition with this night-time snap of a long-tongued bat ( Glossophaga sp.) preparing to feed on a banana plant in Costa Rica. “This was probably one of the most interesting ‘shoots’ I’ve ever been on — it was absolutely fascinating,” says Taylor. “It was very difficult to see these tiny bats flying like ghosts.” Research shows that some of these bats are adapting to feed predominantly on banana nectar , as their natural forest habitats are replaced with plantations.

Image captions

Credit: Marilyn Taylor FRPS FIPF FSWPP/Taylor Made Imagery

- Privacy Policy

- Use of cookies

- Legal notice

- Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility statement

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

Published on May 6, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection .

Example: Hypothesis

Daily apple consumption leads to fewer doctor’s visits.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more types of variables .

- An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls.

- A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

If there are any control variables , extraneous variables , or confounding variables , be sure to jot those down as you go to minimize the chances that research bias will affect your results.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Step 1. ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2. Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to ensure that you’re embarking on a relevant topic . This can also help you identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalize more complex constructs.

Step 3. Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

4. Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

5. Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if…then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis . The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

- H 0 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has no effect on their final exam scores.

- H 1 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has a positive effect on their final exam scores.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 7, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/hypothesis/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, operationalization | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is your plagiarism score.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Understanding Science

How science REALLY works...

- Understanding Science 101

- Misconceptions

- Testing ideas with evidence is at the heart of the process of science.

- Scientific testing involves figuring out what we would expect to observe if an idea were correct and comparing that expectation to what we actually observe.

Misconception: Science proves ideas.

Misconception: Science can only disprove ideas.

Correction: Science neither proves nor disproves. It accepts or rejects ideas based on supporting and refuting evidence, but may revise those conclusions if warranted by new evidence or perspectives. Read more about it.

Testing scientific ideas

Testing ideas about childbed fever.

As a simple example of how scientific testing works, consider the case of Ignaz Semmelweis, who worked as a doctor on a maternity ward in the 1800s. In his ward, an unusually high percentage of new mothers died of what was then called childbed fever. Semmelweis considered many possible explanations for this high death rate. Two of the many ideas that he considered were (1) that the fever was caused by mothers giving birth lying on their backs (as opposed to on their sides) and (2) that the fever was caused by doctors’ unclean hands (the doctors often performed autopsies immediately before examining women in labor). He tested these ideas by considering what expectations each idea generated. If it were true that childbed fever were caused by giving birth on one’s back, then changing procedures so that women labored on their sides should lead to lower rates of childbed fever. Semmelweis tried changing the position of labor, but the incidence of fever did not decrease; the actual observations did not match the expected results. If, however, childbed fever were caused by doctors’ unclean hands, having doctors wash their hands thoroughly with a strong disinfecting agent before attending to women in labor should lead to lower rates of childbed fever. When Semmelweis tried this, rates of fever plummeted; the actual observations matched the expected results, supporting the second explanation.

Testing in the tropics

Let’s take a look at another, very different, example of scientific testing: investigating the origins of coral atolls in the tropics. Consider the atoll Eniwetok (Anewetak) in the Marshall Islands — an oceanic ring of exposed coral surrounding a central lagoon. From the 1800s up until today, scientists have been trying to learn what supports atoll structures beneath the water’s surface and exactly how atolls form. Coral only grows near the surface of the ocean where light penetrates, so Eniwetok could have formed in several ways:

Hypothesis 2: The coral that makes up Eniwetok might have grown in a ring atop an underwater mountain already near the surface. The key to this hypothesis is the idea that underwater mountains don’t sink; instead the remains of dead sea animals (shells, etc.) accumulate on underwater mountains, potentially assisted by tectonic uplifting. Eventually, the top of the mountain/debris pile would reach the depth at which coral grow, and the atoll would form.

Which is a better explanation for Eniwetok? Did the atoll grow atop a sinking volcano, forming an underwater coral tower, or was the mountain instead built up until it neared the surface where coral were eventually able to grow? Which of these explanations is best supported by the evidence? We can’t perform an experiment to find out. Instead, we must figure out what expectations each hypothesis generates, and then collect data from the world to see whether our observations are a better match with one of the two ideas.

If Eniwetok grew atop an underwater mountain, then we would expect the atoll to be made up of a relatively thin layer of coral on top of limestone or basalt. But if it grew upwards around a subsiding island, then we would expect the atoll to be made up of many hundreds of feet of coral on top of volcanic rock. When geologists drilled into Eniwetok in 1951 as part of a survey preparing for nuclear weapons tests, the drill bored through more than 4000 feet (1219 meters) of coral before hitting volcanic basalt! The actual observation contradicted the underwater mountain explanation and matched the subsiding island explanation, supporting that idea. Of course, many other lines of evidence also shed light on the origins of coral atolls, but the surprising depth of coral on Eniwetok was particularly convincing to many geologists.

- Take a sidetrip

Visit the NOAA website to see an animation of coral atoll formation according to Hypothesis 1.

- Teaching resources

Scientists test hypotheses and theories. They are both scientific explanations for what we observe in the natural world, but theories deal with a much wider range of phenomena than do hypotheses. To learn more about the differences between hypotheses and theories, jump ahead to Science at multiple levels .

- Use our web interactive to help students document and reflect on the process of science.

- Learn strategies for building lessons and activities around the Science Flowchart: Grades 3-5 Grades 6-8 Grades 9-12 Grades 13-16

- Find lesson plans for introducing the Science Flowchart to your students in: Grades 3-5 Grades 6-8 Grades 9-16

- Get graphics and pdfs of the Science Flowchart to use in your classroom. Translations are available in Spanish, French, Japanese, and Swahili.

Observation beyond our eyes

The logic of scientific arguments

Subscribe to our newsletter

- The science flowchart

- Science stories

- Grade-level teaching guides

- Teaching resource database

- Journaling tool

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

of 3. Browse Getty Images' premium collection of high-quality, authentic Science Hypothesis stock photos, royalty-free images, and pictures. Science Hypothesis stock photos are available in a variety of sizes and formats to fit your needs.

6,909 hypothesis stock photos, 3D objects, vectors, and illustrations are available royalty-free. ... Science and Research Icon showing one part of the scientific process. Scientists discovering science molecules and making experiments vector outline illustration, laboratorial science research or invention, education.

Browse 110+ science hypothesis stock photos and images available, or start a new search to explore more stock photos and images. Sort by: Most popular. Chess board game concept for ideas and competition and strategy... Chess board game concept for ideas and competition and strategy or Simulation Hypothesis, Theory concept. 3d rendering.

Although Hasler's blindfold hypothesis was disproven, others have fared better. Today, we're looking at three of the best-known experiments in history — and the hypotheses they tested. Contents. Ivan Pavlov and His Dogs (1903-1935) Isaac Newton's Radiant Prisms (1665) Robert Paine's Revealing Starfish (1963-1969)

hypothesis. science. scientific hypothesis, an idea that proposes a tentative explanation about a phenomenon or a narrow set of phenomena observed in the natural world. The two primary features of a scientific hypothesis are falsifiability and testability, which are reflected in an "If…then" statement summarizing the idea and in the ...

The scientific method. At the core of biology and other sciences lies a problem-solving approach called the scientific method. The scientific method has five basic steps, plus one feedback step: Make an observation. Ask a question. Form a hypothesis, or testable explanation. Make a prediction based on the hypothesis.

Search from Hypothesis stock photos, pictures and royalty-free images from iStock. Find high-quality stock photos that you won't find anywhere else. ... Scientific Methods, Hypothesis and Conclusion. Science Research in Lab Concept. Cartoon People Vector Illustration. Scientific Process Icon Set with hypothesis, analysis, etc Scientific Process ...

Find Science Hypothesis stock photos and editorial news pictures from Getty Images. Select from premium Science Hypothesis of the highest quality.

849 Hypothesis Stock Photos and High-res Pictures View hypothesis videos Browse 849 authentic hypothesis stock photos, high-res images, and pictures, or explore additional zoo hypothesis or hypothesis graphic stock images to find the right photo at the right size and resolution for your project.

Bibliography. A scientific hypothesis is a tentative, testable explanation for a phenomenon in the natural world. It's the initial building block in the scientific method. Many describe it as an ...

The six steps of the scientific method include: 1) asking a question about something you observe, 2) doing background research to learn what is already known about the topic, 3) constructing a hypothesis, 4) experimenting to test the hypothesis, 5) analyzing the data from the experiment and drawing conclusions, and 6) communicating the results ...

A hypothesis is a tentative, testable answer to a scientific question. Once a scientist has a scientific question she is interested in, the scientist reads up to find out what is already known on the topic. Then she uses that information to form a tentative answer to her scientific question. Sometimes people refer to the tentative answer as "an ...

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for an observation. The definition depends on the subject. In science, a hypothesis is part of the scientific method. It is a prediction or explanation that is tested by an experiment. Observations and experiments may disprove a scientific hypothesis, but can never entirely prove one.

How to draw your research with simple scientific illustrations. Turn sketchbook ideas into scientific masterpieces: a student's journey. You know the phrase. A picture speaks a 1000 words. And often, a research paper speaks for much longer than it really needs to. SEVERAL thousand words more beyond what you may want to know.

Credit: Ling Li. Skeleton structure. This scanning electron micrograph shows an ultra-close-up view of parts of a starfish skeleton known as ossicles. The highly ordered lattice structure makes ...

DNA testing in a scientific laboratory. Genome research using modern biotechnology methods. Find Scientific Method stock images in HD and millions of other royalty-free stock photos, illustrations and vectors in the Shutterstock collection. Thousands of new, high-quality pictures added every day.

2020 has been a year like no other. The COVID-19 pandemic pushed science to the forefront and dominated lives. But the year also produced fresh images unrelated to the virus. From wafer-thin solar ...

Browse 50+ hypothesis picture pictures stock photos and images available, or start a new search to explore more stock photos and images. Sort by: Most popular. CORDOBA, SPAIN - MAY 15, 2022: Hypothesis room in the Mosque-Cathe. mathematical statistical hypothesis test.

Scientific Hypothesis Examples . Hypothesis: All forks have three tines. This would be disproven if you find any fork with a different number of tines. Hypothesis: There is no relationship between smoking and lung cancer.While it is difficult to establish cause and effect in health issues, you can apply statistics to data to discredit or support this hypothesis.

The month's sharpest science shots, selected by Nature 's photo team. Supernova shot. Astronomers captured this stunning 1.3-gigapixel image of the Vela supernova remnant — the remains of a ...

The specific group being studied. The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis. 5. Phrase your hypothesis in three ways. To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if…then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

Testing hypotheses and theories is at the core of the process of science.Any aspect of the natural world could be explained in many different ways. It is the job of science to collect all those plausible explanations and to use scientific testing to filter through them, retaining ideas that are supported by the evidence and discarding the others. You can think of scientific testing as ...

hypothesis, something supposed or taken for granted, with the object of following out its consequences (Greek hypothesis, "a putting under," the Latin equivalent being suppositio ). Discussion with Kara Rogers of how the scientific model is used to test a hypothesis or represent a theory. Kara Rogers, senior biomedical sciences editor of ...