Should Juveniles Be Tried as Adults? Argumentative Essay

Introduction.

The purpose of this essay is to determine whether juveniles should be tried as adults under the criminal court system. The age of a juvenile according to most laws is 18 years and below.

However, different states have different ages that define who a juvenile in; for instance, Wyoming have acknowledged 19 years to be the age of a juvenile, while states such as New York, Connecticut and North Carolina, one is recognized as a juvenile when he/she is under the age of 16.

Knowing the age of a person suspected to be a juvenile is vital, because this will assist the authorities to decide which court the individual should be charged in. (Juvenile Law Par. 1).

Juvenile Court Systems and Laws

When it comes to determining whether a juvenile offender will be tried as an adult, juvenile court judges usually look at the seriousness of the alleged offense and the need to protect the community from the juvenile offender, the nature of the offense; whether it was violent, premeditated or aggressive, the amount of damage that resulted from the offense, whether the offense was committed against a person or property, the level of maturity of the juvenile offender, whether they have a criminal record or records of achievements and the likelihood of whether the offender can be rehabilitated by the juvenile criminal system (Cassel and Bernstein 42).

Juvenile laws have become very punitive in the recent past to deal with the increasing cases of juvenile delinquency around the world. The general argument that underlies these changes is that juvenile offenders should be held accountable for their criminal behavior by receiving punishments that are equivalent to their crime.

The juvenile laws have also suggested that the current juvenile justice systems do not offer any important psychological differences between juveniles and adults when considering their criminal responsibility. Despite their being declines in violent crimes committed by juveniles in America, all states have revised and adopted juvenile law policies that will be used to increase the prosecution of juveniles as adults (Free 159).

An example of a state that has adopted new juvenile policies is California which passed the Gang Violence and Youth Crime Prevention Act in March 2000. This act would see juveniles who are 14 years and over being tried as adults for any type of violent crime. This act gave state prosecutors the alternative of transferring juvenile cases that were violent or had gang involvement to the adult court without any judicial reviews (Free 159).

States that support the prosecution of juvenile offenders below the age of 14 in adult courts include Arizona who age limit is ten, Arkansas, Colorado, Maryland whose juvenile offender age is seven, Minnesota, Mississippi, Texas, South Dakota and Vermont (Hile 30).

Arguments For and Against Trying Juveniles in Adult Court Systems

Arguments that have arisen for trying juvenile offenders as adults are that violence committed by juveniles is viewed to be a serious problem and it should be dealt with in an effective and efficient manner. Other arguments are that juvenile courts are not effective when it comes to dealing with violence committed by juveniles.

The punishments and sentences that are meted out by juvenile courts are not usually appropriate to the kind of crime that has been committed (Cole and Smith 398). Other arguments that have arisen on trying children as adults are that the procedures used in waiving juvenile jurisdictions are usually problematic and cumbersome in many states in America. Criminal justice and law requires that any violent or heinous crimes committed by a person regardless of their age should be dealt with to the full extent of the law.

Despite these arguments, there are those who continue to propose that violent juvenile offenders should be dealt with by the juvenile court system. Many legal and juvenile experts have argued that trying juveniles as adults will only make things worse. Their main argument is that trying juveniles as adults means that the legal system has failed to consider their social and emotional development which is different from that of adults (Cole and Smith 398).

The arguments that have been raised for not trying juveniles as adults are that; the juvenile system has the appropriate mechanisms that can be used to deal with the social and emotional problems of juvenile offenders, general criminal laws around the world recognize that children have diminished capacities and responsibilities for their actions, meting out adult punishments to juvenile offenders robs them of their childhood and threatens their psychological development.

Such arguments have put pressure on legislators to lower the age of adulthood so that violent cases for serious juvenile offenders can be tried in the adult court system. This has however been viewed to be a futile exercise given that different states have different guidelines and procedures that are used to determine the appropriate age of a juvenile.

Some legal experts have argued that setting artificial guidelines to be used in determining whether a juvenile is an adult will restrict the ability of the court system to convict the juvenile offenders based on the type of crime they have committed (Hile 32).

The main argument that has been identified in the essay is that juvenile offenders who have mostly committed violent crimes should be tried and prosecuted in the adult criminal court system. This is mostly because the juvenile system does not provide the necessary punitive actions that can be used to deal with serious juvenile offenders.

Arguments in the essay have shown that to counter the juvenile system’s poor punishments, serious offenders should be tried in the adult court systems which have been viewed to be more punitive and strict when it comes to serious violent crimes

Works Cited

Cassel, Elaine and Bernstein, Douglas. Criminal behaviour , 2 nd Edition, New Jersey, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associate Publishers, 2007. Print.

Cole, George and Smith, Christopher. Criminal justice in America. California: Thomson Wadsworth Education Publishers, 2008. Print.

Free, Marvin. Racial issues in criminal justice: the case of African Americans . Westport, US: Praeger Publishers, 2003. Print.

Hile, Kevin. Trial of juveniles as adults. United States: Chelsea House Publishers, 2003. Print.

Juvenile Laws. History, trying juveniles as adults, modern juvenile law, should the justice system be abolished ? N.d., Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 31). Should Juveniles Be Tried as Adults? https://ivypanda.com/essays/trying-juveniles-as-adults-outline/

"Should Juveniles Be Tried as Adults?" IvyPanda , 31 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/trying-juveniles-as-adults-outline/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Should Juveniles Be Tried as Adults'. 31 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Should Juveniles Be Tried as Adults?" October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/trying-juveniles-as-adults-outline/.

1. IvyPanda . "Should Juveniles Be Tried as Adults?" October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/trying-juveniles-as-adults-outline/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Should Juveniles Be Tried as Adults?" October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/trying-juveniles-as-adults-outline/.

- Business Law. Punitive Damages in Florida

- Why Juveniles Should Be Tried in Adults’ Court?

- Juvenile Justice System vs. Adult Prosecution

- Crime Policy and Practices: Trying Juveniles as Adults

- Punishments for Juvenile Offenders

- Features of Conviction of Juvenile Offenders

- Gangs and Juvenile Delinquency

- Juvenile Justice System of USA

- Juvenile Delinquency

- Future of the Juvenile Justice System

- Policing the Drug Problem in United States

- Business Law: Periodicals Review

- Title VII Fact Situations

- Understanding Legal Aspects and Current Issues of Compensation Methodologies

- Gun Control in the USA

- Essay Editor

Should Juveniles Be Tried as Adults? Argumentative Essay

1. introduction.

The age at which a person can be tried as an adult in the criminal justice system is the subject of much discussion and debate. Up until recently, the age of eighteen was the cut-off at which a person could be tried as an adult in the United States. However, the ever-increasing rise of violent juvenile crime in the 1970s and 1980s led to widespread changes in many state juvenile crime laws, so that a minor as young as 14 years of age could now be tried as an adult if the crime was serious enough. The crux of the debate comes down to whether a juvenile offender should be judged and punished in the same realm as an adult. On one side of the issue, there are people who believe that children and adolescents are not competent to make adult decisions and therefore should not be held accountable in an adult manner. These people believe that child brains are undeveloped, leaving them unable to understand the repercussions or consequences of their actions. Additionally, children are assumed to have plenty of time to learn the correct behavior, so detractors of trying juveniles as adults feel that rehabilitation is a much more sound correctional tactic for youth. Those in opposition to trying minors as adults would also argue that placing the label of "convict" or "felon" on a juvenile can be detrimental to his or her future. Being convicted as an adult can lead to time in an adult penitentiary or jail, which proves to be an even harsher environment for a youth. Finally, there is a belief that the transfer to adult court does no more to prevent crime than would have been done by keeping the juvenile in the juvenile court system.

1.1. Background information

Juvenile is a term which defines a person who is under 18 years old, but in some cases, teens are often tried as adults. In many states, such as Vermont, Georgia, and Michigan, the law states that a juvenile is any person under the age of 17. In previous years, the idea of being tried as an adult was only for the worst of crimes. However, times have changed, and being tried as an adult no longer is based on the severity of the crime, but the age of the offender. One of the greatest achievements of the Juvenile Justice System was to recognize the fundamental difference between adults and children, and the system was designed to treat the children with the best interests at heart, to protect their welfare, and to help them avert a life of crime. In the adult court, the primary concern is the renditions of justice, and a conviction with little thought to rehabilitation or future impacts on the life of the convict. When a juvenile is tried as an adult in a criminal court, they will carry the permanent label of convicted criminal, instead of having the chance of a clean record if treated in a juvenile court. Dropping the age of Juvenile court jurisdiction has been done under the pretenses of protecting the public and that it would serve as a deterrent of future crime. However, studies have shown that minors prosecuted in adult court are more likely to reoffend in the future compared to those convicted of similar crimes in juvenile court. Often they become placed in an adult prison or jail, where their protection cannot be guaranteed and are exposed to violence, sexual abuse, and diseases, and the cost of the offense committed will be far greater. Although it varies by state, if a juvenile is tried as an adult and convicted in a criminal court, they may also receive an adult sentence such as life imprisonment with no chance of parole or probation, or the death penalty. In the case of the death penalty, it is unconstitutional to execute someone who committed a crime under the age of 18, however, there are many instances in which the defendant was close enough to the age 18 that the death penalty was a sentence as a mere form of punishment fitting the crime. This is exactly the opposite of what the Supreme Court case Thompson v. Oklahoma ruled when it claimed that neither the execution of an individual at 15 years old nor the life imprisonment of a 16-year-old for a minor property crime were permissible.

1.2. Thesis statement

The thesis statement is that this essay will try to prove that there is enough evidence to indicate that when a juvenile is tried as an adult for their acts of violence, there is a lower percentage of case recurrence and a decrease in violent acts committed by a juvenile. In order to make this position clear, the difference between child and adult, and the commingling of the two standards in the juvenile and adult system will be examined, as well as the process of transferring the juvenile to adult court. Also examined will be the effectiveness of deterrence of punishment on both types of systems. A discussion of both the future implications of the two systems, as well as an alternative solution, is included. Overall, it will be demonstrated that a juvenile sentencing to the adult system can be a beneficial measure for both the safety of the community and the best interests of the juvenile.

2. Arguments in favor of trying juveniles as adults

2.1. Responsibility and accountability It is often mentioned in the justice system that if a juvenile commits a crime that is deemed "adult-like," then the juvenile should be treated as an adult. The court system is said to be based upon punishment and justice, but the special treatment often deters justice. Juveniles are not learning how to be responsible for their actions when they are being tried as juveniles. Trying these juveniles as adults may hold them accountable and responsible, and they may actually learn that in order to be a respected member of society, there are consequences that need to be faced when a wrong action is taken. Minors should uniformly be held to the same standard as adults whenever they commit the same crime. The best way to do this is to try them as adults. If a juvenile can commit a crime deemed as an adult and they are able to understand the long-term consequences and effects of their actions, then they should be prepared to face the long-term consequences. Juveniles tried and convicted as adults face sentencing to adult penalties, including adult jails and state prison facilities where they are subject to the same length of sentence and conditions thereof as their adult counterparts. Despite abolition of the death penalty for juveniles, many states uphold this sentence for crimes committed when the offender was under the age of 18. Resulting in transfer enables prosecution of juveniles as adults and long-term confinement. 2.2. Deterrence and public safety It is sometimes debated as to whether or not trying a juvenile as an adult would bring forth a deterrence to other juveniles. The belief is that if juveniles know they can "beat the system" and receive a much lesser punishment than they deserve, they will continue to commit adult-like crimes because they know they are getting away easy. Some juveniles have the mentality that juvenile crimes are not "real crimes" and anything done in the juvenile justice system is just a slap on the wrist. This logic comes from the fact that many youths are not receiving a punishment to fit their crime and are getting off easy because there are limitations to the sentencing that can be given in the juvenile system.

2.1. Responsibility and accountability

According to MacArthur Foundation research on adolescents, "Treatment that is age-appropriate is essential for youngsters, but they also need to face consequences that are commensurate with the offense." Although we would prefer to believe that everyone must be held accountable for his or her actions, there are differences in the level of responsibility that can be attributed to children and adults based on the developmental stage of the individual. When a juvenile engages in risky behavior, there are biological factors that can mitigate the extent of his responsibility. Research has shown that brain development continues through adolescence and into early adulthood. The part of the brain responsible for decision-making, the prefrontal cortex, is not fully developed until the age of 25. This means that juveniles may be less capable of considering the long-term consequences of their actions, resulting in an impulsive decision. In some cases, trials have determined that a minor had the intent of an adult, despite a demonstrated lack of understanding of the implications of his actions. It is unjust to compare the understanding and intent of a juvenile to that of an adult when making a similar decision. The findings of a National Institute of Mental Health study using a simulated driving game support this claim. In this study, the younger the subject, the more likely he or she was to make a risky decision, regardless of failing past experience of negative consequences. This indicates that the capacity for learning from past mistakes is lower in juveniles. It may not be fair to say that a juvenile who committed a crime lacks the understanding of right and wrong, but it is probable that the decision-making process involved was less thoughtful and informed than that of a typical adult.

2.2. Deterrence and public safety

There are two important sides to the issue we are addressing. First is the plight of the victim and the views of society on juvenile offenders. The idea is that the offender's potential for committing violence is so dangerous to society that they must be put under adult jurisdiction no matter what the level of the offense. This is often said to be in the best interest of public safety and is a fear of many people. Considering the demographic trends of increased youth crime, numerically this is a valid concern. However, in terms of serious youth violence, this is not the case. Most serious violent offenses are committed by a small and finite group of juveniles. These juveniles tend to be the ones either tried as adults or are subject to waiver laws allowing for transfer to adult court. The crimes committed by this group are not deterred by the threat of adult punishment. Rather, it is the concept of youth punishment, inescapable due to the automatic certification for serious offenses, that has become an acceptable occupational hazard for these offenders. They know that juvenile sanctions, even for certified offenders, secure very short confinement in limited security facilities. This, in turn, has led to a trend of increased violent juvenile crime. It is at this point that the second side to this issue is addressed. In light of the fact that society's main goal is prevention and protection through incapacitation, there is a hope that a transfer to adult court will lead to more incarceration of violent youth offenders in adult correctional facilities. This is despite the fact that studies have shown that a minority of violent offenders trying to escape the juvenile justice system through acts of on or off-site petition have learned that adult certification always leads to a return to the juvenile system, which is still considered preferable to them. Nevertheless, on the assumption that this group of offenders will remain in adult courts and facilities, advocates of transfer believe it will prevent them from committing future violent offenses and lead to the prevention of the aforementioned phenomenon in the long term.

2.3. Severity of the crime committed

Objective: The crime committed by a juvenile cannot be treated as an adult. The act itself is heinous and brutal, but the offender is a child. It may be a case of an exceptional child who committed a terrible crime, but it cannot be forgotten that children are assets. Delinquency is the outcome of the crime because by committing heinous crimes, are we trying to say that the child is becoming a liability and burden? If yes, then what are the causes behind the crimes of the juveniles? It is the society who is responsible for such acts committed by the children. By trying juveniles as adults, are we trying to escape from the social responsibility and shifting the blame on the individual? In a society or community, the crime or offense committed by an individual affects the society. It creates awareness and alarm for the society and the community where the crime is committed. The fear of crime disturbs the peace and tranquility of the community or the society. The effect of the crime on an individual may be positive or negative. If the effect is negative, then there is a scope of reformation and rehabilitation. Sentencing a juvenile as an adult itself proves the negative effect of the crime. There are various ways to reduce or eliminate the bad impression of the crime. Juveniles have a tender age. It is well familiar with the philosophy "child is the father of man." Then why forget the child psychology? They may change according to the circumstances because the circumstances mold the man's character. It may be to escape from punishment, but in the case of the child, it is a better way to change the character.

3. Arguments against trying juveniles as adults

From a more psychological standpoint, the fact that adolescents have not matured completely, either physically or mentally, and are more susceptible to negative influences and peer pressure makes it harder for them to make rational decisions, with many of their actions being impulsive and thoughtless. This is due to the fact that the part of the brain responsible for decision-making, the prefrontal cortex, is not fully developed until around the age of 25. Because this is the case, they may not fully understand the severity of their actions and the consequences that may follow, and thus should not be held fully accountable for them since they do not perceive themselves to be committing adult crimes. In the words of Laurence Steinberg, a leading expert on adolescence, "It is inaccurate, and thus unfair, to define an adolescent act, no matter how serious it is, as evidence of a permanently defective character." Related to this is the idea that juveniles have the capacity to change and are more inclined to be rehabilitated, which is generally the primary goal when dealing with delinquents. Try them as adults and that changes. Many will end up in adult correctional facilities, be denied education, vocational training and mental health services - all programs that are fundamental for their change and development. Such juveniles will be at a higher risk of reoffending and will increase the ratio of youth to adult crime.

3.1. Brain development and maturity

Age plays a significant role in one’s ability to form judgments and understand consequences. Adolescents are known to be impulsive risk-takers, leading to dangerous behavior such as drug abuse and delinquency. Adolescence is also a time of rapid and extensive change in learning, memory, and cognitive control. In fact, the brain continues to develop through the adolescent years and into early adulthood. Understanding the still-developing nature of the adolescent brain can help in guiding adolescents toward positive growth. The areas of the brain responsible for decision-making and impulse control are still being formed and refined in adolescence and do not fully develop until the individual is in their early 20s. Because of this, young people may be more likely than adults to engage in risky or careless behavior and less likely to think before they act. In some cases, this can result in impulsive and ill-informed decisions with devastating consequences. Such is the case for 16-year-old Florida native, Lionel Tate, who was convicted of first-degree murder for violently beating to death a six-year-old family friend when Tate was left unsupervised. In an investigation of the case, it was discovered that Tate was attempting to mimic pro-wrestling moves that he had seen on television. Because of the particularly brutal crime, Tate was tried as an adult, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison. After three years in incarceration, the case was retried and the jury recommended Tate's release. Currently, Lionel Tate is spending 30 years on probation. Had Tate's brain been more developed or had he been mentally sound, the wrestling moves would not have been attempted and the tragedy would never have occurred. The immaturity of the adolescent brain often means that an individual may not fully understand the extent of his actions or the consequences that follow.

3.2. Rehabilitation and reintegration

The section "Rehabilitation and Reintegration" is quite coherent with both the other sections of the essay and the essay's overall argument. The claim is that juveniles should not be tried in the adult system because they cannot fully comprehend their actions and the punishment stemming from their actions. The overall argument of the paper is that juveniles should be kept in the juvenile system because they are children and they have diminished capability. In the Brain development and maturity section, facts were presented which showed that juveniles have a lesser capability in certain cognitive realms. These claims are consistent with the claim in this section that juveniles are less able to learn from their mistakes. This section also claims that sending juveniles to the adult system increases recidivism rates. This is consistent with the claim within the potential for harsh sentencing section, which states that children tried as adults receive disproportionately harsh sentences. Finally, it is claimed that keeping children in the juvenile system better protects the community. This claim is consistent with the essay's overall claim that children are not simply small adults, and they are far different from adult criminals.

3.3. Potential for harsh sentencing

Currently in the United States, five percent of convicted murderers are sentenced to death, and at least 22 juveniles have been convicted for crimes that have led to a death and been sentenced to death since 1990 (DPIC, 2016). Despite the fact that half of these sentences have been overturned due to the unconstitutionality of executing juveniles, it is clear that juveniles who are transferred to the criminal justice system are at risk of very severe sentences, including life imprisonment without the possibility of parole (LWOP) and execution. Petitioning for a juvenile to be tried as an adult is a direct contradiction to the purpose of the juvenile system, which is to rehabilitate and prevent reoffending, as the juvenile will no longer have the opportunity to take advantage of the resources and reduced punishment offered through the juvenile system. DW Pfeiffer, an American lawyer and author, explains that the harsh punishment faced by juveniles tried in the adult system stems from the public perception that the only way to protect society is to punish the offender the same way they have hurt the victim. Because a juvenile tried in the adult system is viewed and punished as an adult offender, there is no differentiation between them and adult offenders who have committed the same crimes. This perception has led to the increase in imposing adult sentences on juveniles, as well as increasing the severity of sentences given to youth for less serious crimes within both the juvenile and adult systems (Pfeiffer, 1998). This contradicts the principles of diminished responsibility and culpability of the offender due to their age, and it also contradicts the principle that a lesser sentence is appropriate for a lesser offence (NCYL, 2001). This need to punish juvenile offenders as severely as adult offenders demonstrates society's lack of understanding that youth are impulsive, short sighted, and are less capable of understanding the long-term consequences of their actions.

Related articles

White collar crime.

1. Introduction White collar crime is a term that is applied to non-violent crimes committed by business or government professionals for the purpose of financial gain. The "white collar" is usually applied to people who have certain recognized means of livelihood and who are salaried employees. It could also be applied to persons who are recognized as having a dependable means of income even if that income is not derived from a regular job or other occupation in the technical sense of the term. ...

The Classical School of Thought and Strain Theory in Criminology Essay

1. Introduction The earliest theoretical framework of criminology emerged from the Classical School of Thought in the late 17th to mid-18th century. The core concept of this theory was to search for the causes of crime in the nature of man as a rational actor, an individual making conscious decisions. The classical theory propounded that in a free society, an individual is free to choose their own path and therefore choose to engage in criminal behavior. In this theory, it was also put forth th ...

James Hardie Asbestos Case History

1. Introduction James Hardie Industries and its Canadian subsidiary have been defending a class action lawsuit brought on behalf of people residing in British Columbia. This action is against several manufacturers and distributors of building materials containing asbestos. The claim involves issues of conspiracy to suppress the hazards of asbestos-containing products, negligence, breach of duty, and breach of consumer protection legislation. In the 1940s, claims began to emerge regarding the he ...

Mass Incarceration in the United States Essay

1. Introduction Mass incarceration is one of the biggest social issues faced by the United States. It is also a result of America's longstanding history of racism that challenges the notion of the United States as the 'land of the free'. A system which has successfully locked up the majority of its minority citizens has been labeled "the new Jim Crow" by Michelle Alexander. The US has witnessed rates of imprisonment unparalleled by any other industrialized country. However, when these incarcera ...

Silence of the Lambs

1. Introduction Silence of the Lambs is a psychological thriller that has achieved great recognition in recent years, but has a number of unsavory connotations in regard to its subject matter. This special section of the film is pivotal in fiction and film in evoking and maintaining viewer interest and participation in the story. Giving audiences pieces of information to make them feel like insiders who know more than the characters themselves can facilitate an exciting level of involvement and ...

Cyber Crime and Necessity of Cyber Security Report

1. Introduction Definition of cyber crime Cyber crime is a malicious act done by a person to others using modern telecommunication networks and electronic technology, such as: 1. The perpetrator who is doing the crime or the act itself. 2. The computer used as a tool to commit the act. 3. The computer can be used in several ways as a tool in a crime, for example, the thief steals it to sell or it can be used as a storage device to store the evidence of the crime. 4. The computer can be used as ...

Poverty as a Great Social Problem and Its Causes Essay

1. Introduction Of all the social problems that exist in the world today, poverty is often considered to be the most pervasive. For this reason, there is an obvious need for a more thorough understanding of the causes of poverty as a prerequisite to the effective amelioration of this social condition. It is to this understanding that this essay is directed, attempting to sketch the complex web of interaction between economic and social forces which have produced for us a society in which millio ...

Criminal Procedure Essay Topic Ideas

1. Overview of Criminal Procedure Criminal procedure concerns the enforcement of individuals who have been suspected or are accused of committing a criminal offense. According to the due process model, a defendant is granted a variety of rights throughout the criminal justice process. The overall procedure begins with a crime allegedly committed and ends with a verdict or a decision based on the available evidence. The criminal procedure process is very complex and is full of intricate steps th ...

Should Juveniles Be Tried as Adults?

Jan 8, 2007, 12:00 AM

Reprinted from the Sunday, January 7, 2007 edition of The Tennessean

"Old enough to do the crime, old enough to do the time."

This popular refrain reduces a complex reality to simplistic rhetoric. It’s also wrong. While young people must be held accountable for serious crimes, the juvenile justice system exists for precisely that purpose. Funneling more youth into the adult system does no good and much harm.

Juveniles are not adults, and saying so doesn’t make it so. Besides, we don’t really mean it: When we try them in criminal court, we don’t deem them adults for other purposes, such as voting and drinking. We know they’re still minors — they’re developmentally less mature and responsible and more impulsive, erratic and vulnerable to negative peer pressure.

As people, they are still active works in progress. We just don’t like the logical consequences of that reality — that they are by nature less culpable than lawbreaking adults, even when they do very bad things. So we change the rules of the game.

Which is precisely what we’ve done. In the last decade, virtually every state has made it much easier to try juveniles as adults. These sweeping changes came amidst widespread alarm that a wave of "juvenile superpredators" was coming — which fortunately turned out to be false. (In fact, juvenile crime was already falling by the time states were tightening the screws.)

In some states, including Tennessee, there is now no minimum age for being transferred to criminal court for certain crimes. It’s not abstract: Kids as young as 10 have been charged as adults.

The consequences of this switch-up can be extreme. Most young offenders do not become adult criminals. But when we punish them as adults, we change those odds. Teens tried as adults commit more crimes when released; their educational and employment prospects are markedly worse, creating opportunity and incentive for more crime; they bear a lifelong, potentially debilitating stigma.

The separate juvenile system was developed both to mitigate these harms and because youth were being preyed upon and "schooled in crime" while in adult prisons. We are now sending them straight back to that harsh schoolyard. All this for little or no payoff: Increased transfer has never been shown to reduce juvenile crime.

Our desire to ratchet up consequences is understandable. Victims of juvenile crime don’t hurt any less, and close cases (say, crime committed the day before the 18th birthday) make age distinctions seem arbitrary. This is why we historically have built in a small "safety valve," under which transfer arguably is appropriate for those very few offenders who are extremely close to the age cutoff and commit particularly awful crimes. The trouble is that the valve has both expanded and lost its spring. Indeed, people now act as if the decision to treat a juvenile as a juvenile implies a judgment that the crime was not that serious, the victims not that worthy of respect.

It doesn’t have to be this way. I once attended the sentencing of a teenager — Clarence — who had killed a woman — Pauline — who sang in my choir. The proceeding was no less solemn, no less tragic by reason of being in a juvenile court. Clarence was sent to a secure facility that very much resembled a prison. His family was destroyed. Pauline’s family was destroyed. The only slight glimmer of hope was that Clarence might, while incarcerated, grow up and become a law-abiding adult and that we would not collectively make him worse than when he went in.

When we consign our youth to the adult system, we are throwing away even that glimmer. Juvenile sentences, in contrast, shield our youth from the unique dangers of adult facilities and preserve the possibility — however slight it may seem — of rehabilitation.

Terry A. Maroney joined the Vanderbilt Law faculty as assistant professor in Fall 2006.

Explore Story Topics

- Vanderbilt Law News

Trying and Sentencing Youth As Adults: Key Takeaways from Recent Petrie-Flom Center Event

By Minsoo Kwon

All 50 states have transfer laws that either allow or require children to be prosecuted in adult criminal court, rather than juvenile court. There is no constitutional right to be tried in juvenile court. What has modern neuroscience shown about the differences between the developing and the adult brain, and how justifiable is trying, prosecuting, and sentencing children in the adult criminal justice system?

Panelists discussed these topics during a recent webinar hosted by the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics. This article highlights key points made during the conversation.

First, BJ Casey , Christina L. Williams Professor of Neuroscience at Barnard College explained key neuroscientific research that highlights the significant differences between the brains of children and adults.

- Casey presented data that focused on ages 10 to 25 years to demonstrate observable changes in the brain’s capacity for change, also known as plasticity, throughout the emerging adolescence period. She discussed additional relevant neuroscience concepts, such as structural changes in gray matter and cortical thickness, and changes in personality and self-regulation.

- Along with critical changes in the prefrontal cortex, there are changes in the deep primitive regions of the brain. Such regions, Casey noted, “are involved in desire, rage, and fight and flight.” Adolescents, she explained, have a “heightened sensitivity to emotional information related to rewards, threat, stress, also social information like peer influences. And this is combined with this under-appreciation of risks and consequences.”

- “There are expert and health organizations like the World Health Organization, NIH, United Nations who all acknowledge that there’s continued maturity and development that extends into the 20s and even our laws in this country recognize extended maturation in the early 20s with the extended age for drinking and foster care,” Casey said. “It’s not just special protections that youth need. [They also need] opportunities for them to build the very skills that are necessary for being a healthy independent adult and a contributing member of society.”

- Casey explained: “We know in the United States that psychopathy is relatively rare. The estimates are at one percent in this country. But what if we look at individuals who have psychopathic traits, does that change across development? I want to report the findings from over a thousand justice-involved youth who showed from 16 to 24 years of age a decrease in their psychopathic traits… the majority of youth who engage in antisocial behavior show declines in that criminal behavior with age, and with targeted interventions we could get an even bigger decline.”

- “It’s about getting the right treatment,” said Casey.

- The science does not support transferring children and youth to adult courts, she explained, not only because of the significant differences in brain structure and behavior, but also because there is hope to treat these youth with targeted interventions that would effectively curb criminal activity as they age into full adulthood.

Then, Marsha Levick , Chief Legal Officer and Co-Founder of the Juvenile Law Center, discussed specifics of the juvenile and adult criminal justice systems in the U.S.

- “Once these youth are put into the adult criminal justice system, those systems are driven by punishment and retribution. They are not at all centered-on rehabilitation. The kinds of rehabilitation programs and positive interventions… will be significantly fewer, if they exist at all, than what you will see in the juvenile system,” Levick said.

- “What often happens is that judges will make determinations that they don’t think there’s enough time in juvenile court to allow for available treatment options to actually have an impact. It’s also often the case that there may simply not be a facility available in a particular jurisdiction,” Levick said.

- Instead, the juvenile justice system operates within 51 separate jurisdictions, each “constrained only by relatively minimal limitations that the U.S. constitution imposes upon them,” Levick said.

- “States that allow for this kind of charging discretion give these prosecutors unfettered discretion,” Levick said. This is particularly dangerous in states that have a “once an adult, always an adult,” policy. This means that once a child is transferred into the adult criminal justice system, they will automatically be treated as an adult for any relevant crimes going forward.

In their concluding remarks, Casey and Levick emphasized that a discussion of juvenile justice in the holistic sense must be one that acknowledges the power of targeted treatment in the prevention of crime, as well as the current structural problems that force children into the adult criminal justice system. Panelists ended with poignant statements of how the United States must begin to reconcile our treatment of justice-involved youth that is currently inconsistent with scientific evidence.

“We tolerate an inconsistency in how we approach young people who are involved with the justice system in this country that is irrational. It is completely counter to scientific knowledge that we possess and have reasonable access to,” Levick said. “The unwillingness to follow the science combined with a cultural commitment to punishment has really prevented us from making smart choices.”

Casey concluded: “We have a long way to go, but we really need to move in the direction of remediation, as opposed to being punitive… and that is going to be a real paradigm shift.”

This transcript has been edited and condensed. Watch the full event video here . This event was sponsored by the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School and is part of the Project on Law and Applied Neuroscience, a collaboration between the Center for Law, Brain and Behavior at Massachusetts General Hospital and the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School, with support from the Oswald DeN. Cammann Fund at Harvard University.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Minsoo Kwon

Minsoo Kwon is a Junior at Harvard University studying Neuroscience and an intern at the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Sign up for our newsletter

Should Juveniles be Tried as Adults

This essay about the adjudication of juveniles navigates the intricate ethical and sociological implications of trying them as adults. It explores the tension between cognitive development and legal culpability, advocates for accountability and deterrence, prioritizes victim rights, and discusses the delicate balance between recidivism and rehabilitation. By intertwining developmental insights with imperatives of societal welfare, it proposes a nuanced approach to juvenile justice that transcends binary discourse, fostering a holistic milieu centered on justice and compassion.

How it works

Within the labyrinth of legal discourse, the interrogation of whether juveniles should be subjected to adult trials resonates with profound ethical and sociological implications. This perennial debate, entwined with the nuances of morality, rehabilitation paradigms, and societal safety nets, forces a contemplation of the intricate balance between justice and compassion. This essay embarks on a nuanced exploration of the contention surrounding the adjudication of juveniles, advocating for a contextualized approach that amalgamates developmental insights with the imperatives of accountability and societal welfare.

Navigating Developmental Dynamics:

At the heart of the discourse lies the dialectic tension between the evolving cognitive landscape of juveniles and the imperatives of legal culpability. Adherents of a lenient approach underscore the inherent disparities in cognitive maturation, emphasizing the protracted neurobiological transformation characterizing adolescence. Undoubtedly, adolescence is a stage rife with cognitive flux, where impulse control and foresight often lag behind burgeoning emotions. However, such assertions, while cogent, falter in their universal applicability. The heterogeneity of adolescent experiences necessitates a discerning lens, one that discerns between impulsive misdemeanors borne of developmental turbulence and premeditated transgressions indicative of a matured agency.

Embracing Accountability and Deterrence:

Integral to the fabric of any justice system is the principle of accountability, which undergirds the moral edifice of societal order. Advocates of trying juveniles as adults accentuate the imperatives of accountability, echoing the sentiments of retributive justice. The premise that actions must engender commensurate consequences resonates deeply within legal philosophy, heralding a system predicated on the principle of just deserts. Furthermore, the deterrence argument, predicated on the notion that stringent penalties dissuade potential offenders, underscores the pragmatic exigency of adult trials. The specter of adult repercussions, with its attendant gravity, serves as a potent deterrent, dissuading juveniles from traversing the perilous terrain of criminality.

Restoring Equilibrium: A Victim-Centric Paradigm:

At the nucleus of the justice paradigm lies the plight of victims, whose narratives are often eclipsed amidst the discourse on offender rehabilitation. The reification of victim rights necessitates a recalibration of legal praxis, one that ensures that justice is not merely dispensed but also perceived. Victims of heinous crimes, ensnared in the labyrinth of trauma, yearn for closure and vindication. By adjudicating juveniles as adults in egregious cases, the legal apparatus not only amplifies the voices of victims but also fosters a climate of restorative justice. Denying victims the catharsis of witnessing perpetrators being held accountable obfuscates the path to healing, perpetuating the specter of unresolved trauma.

Striking a Delicate Balance: Recidivism and Rehabilitation:

Critics of the adult trial paradigm often invoke the specter of recidivism, cautioning against the potential erosion of rehabilitation efforts. The punitive tenor of adult correctional facilities, juxtaposed against the malleable psyches of juveniles, portends a perilous trajectory fraught with recidivist pitfalls. However, such apprehensions, though valid, elide the nuances of a holistic rehabilitative schema. The confluence of accountability and rehabilitation, rather than constituting antithetical poles, can synergistically coalesce within a judicious legal framework. Tailored intervention programs, replete with therapeutic modalities and reintegration initiatives, hold the promise of not only ameliorating recidivist propensities but also engendering a restorative ethos conducive to societal reintegration.

Conclusion:

In summation, the discourse surrounding the adjudication of juveniles is a dialectic tapestry interwoven with the threads of moral imperatives and societal exigencies. The dichotomous imperatives of accountability and rehabilitation, far from constituting mutually exclusive propositions, converge within a nuanced legal prism. By recalibrating the paradigm of juvenile justice, cognizant of developmental dynamics and societal imperatives, the legal apparatus can transcend the shackles of binary discourse, engendering a holistic milieu predicated on the twin pillars of justice and compassion. Thus, the imperative lies not in succumbing to the allure of categorical imperatives but in embracing the dialectic flux inherent within the crucible of justice.

Cite this page

Should Juveniles Be Tried As Adults. (2024, Apr 07). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/should-juveniles-be-tried-as-adults-new/

"Should Juveniles Be Tried As Adults." PapersOwl.com , 7 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/should-juveniles-be-tried-as-adults-new/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Should Juveniles Be Tried As Adults . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/should-juveniles-be-tried-as-adults-new/ [Accessed: 21 Apr. 2024]

"Should Juveniles Be Tried As Adults." PapersOwl.com, Apr 07, 2024. Accessed April 21, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/should-juveniles-be-tried-as-adults-new/

"Should Juveniles Be Tried As Adults," PapersOwl.com , 07-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/should-juveniles-be-tried-as-adults-new/. [Accessed: 21-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Should Juveniles Be Tried As Adults . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/should-juveniles-be-tried-as-adults-new/ [Accessed: 21-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Criminal Justice Collaborative

Charging youths as adults can be a 'cruel wake-up call.' is there another way.

Renata Sago

The booking and release center at the Orange County Jail in Florida, where juveniles who are charged as adults await trials in criminal court. Mark Wilson/Getty Images hide caption

The booking and release center at the Orange County Jail in Florida, where juveniles who are charged as adults await trials in criminal court.

The moments inside a courtroom in Orlando in 2007 were quick and consequential for Marquis McKenzie. The 16-year-old stood handcuffed behind a lectern. A juvenile judge announced his charges, then apologized that he could no longer take up the case.

"You're being direct filed," he told McKenzie, who was accused of armed robbery over a cellphone and a wallet. "You understand what I'm saying? You're being charged as an adult now."

As a 16-year-old, Marquis McKenzie was sent to the juvenile section in one of Florida's medium security private prisons. Joey Roulette hide caption

As a 16-year-old, Marquis McKenzie was sent to the juvenile section in one of Florida's medium security private prisons.

McKenzie remembers his mother wailing from the courtroom benches, begging the judge to reconsider.

"I had never been in that situation. I had gotten in trouble, but I had never gotten arrested," he recalls a decade later. "I just knew it was going to be a hell of a ride from there."

The juvenile judge's announcement meant that McKenzie was no longer solely subject to the rehabilitative services offered within Florida's juvenile system. He was now facing a 10-year sentence. A judge in one of the state's criminal courts would have the option of sending him two hours away to residential confinement at a youth facility, or to the juvenile section in one of Florida's medium security private prisons.

The latter is where McKenzie ended up. That same year, more than 3,600 other kids were direct filed and sent to adult court, too.

Across the country, lawmakers, juvenile justice advocates and community groups are shifting away from direct file, and rethinking their approach to handling kids and young adults who commit crimes. Florida, more than other states, has traditionally embraced an aggressive direct file system run by state attorneys who opt to transfer kids out of the juvenile court system and into the adult criminal system. The repercussions are great and the options for navigating the complex system are limited.

" Cruel wake-up call"

Florida was in the thick of its direct file culture when McKenzie's case was transferred to adult court. From 2006 to 2011, more than 15,600 youths passed through the adult criminal court system for violent and nonviolent offenses.

"That was a 'get tough' era in the United States," says Florida State University criminologist Carter Hay. "That was a time when there was a lot of concern about juvenile crime. There was a lot of media attention to the idea that there were these juvenile superpredators who were just a real threat to public safety."

Lionel Tate Back in Jail on Holdup Charge

Behind the trend were state attorneys, to whom Florida's direct file statute grants unfettered discretion to move any juvenile case to adult court without a judge's permission. The statute dates back to juvenile justice reform from the 1950s, when lawmakers were seeking to balance rehabilitation and punishment of youths who had committed heinous crimes. In the 1990s and into the 2000s, the direct file statute became the most used tool for handling children.

"A lot of these juveniles that have been through the system a lot, when they get arrested, their attitude is 'Nothing's going to happen to me. I'm a juvenile,' " says former 9th Circuit state attorney Jeff Ashton.

For more than 30 years he helped prosecute juvenile cases in Orange and Osceola counties, where McKenzie was direct filed. As state attorney, he spent four years having a final say over which cases got sent to adult court.

"When they get direct filed to adult, it's sort of this cruel wake-up call," he says.

The Orange County Juvenile Assessment Center is where youths are taken when arrested. There, case managers use risk assessment tools to make recommendations for the state attorney on how youths should be handled. In recent years, the state of Florida has invested more resources in its risk assessment tools. Joey Roulette/WMFE hide caption

The Orange County Juvenile Assessment Center is where youths are taken when arrested. There, case managers use risk assessment tools to make recommendations for the state attorney on how youths should be handled. In recent years, the state of Florida has invested more resources in its risk assessment tools.

According to Ashton, the direct file statute gives judges a "bigger toolbox" for deciding how to deal with youths who have committed crimes. It also allows for more nuances in how prosecutors across Florida's 20 circuits interpret the gravity of crimes and the potential threat a youth offender has on the overall safety of a community, criteria that arguably reflect personal values and interpretations of the law.

In a 2011 report , the U.S. Department of Justice identified Florida's direct file rate as disproportionately high compared to other states. The statute is hard to measure and easily classifiable as subjective. Human Rights Watch, in a report on juvenile justice, criticized Florida's direct file statute as an example of disparate treatment of people of color. Its report found that from 2008 to 2013, black boys in Florida were disproportionately sent to prison, whether for first- or second-time offenses.

That trend continues with data from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice showing that 64 percent of kids sent to adult court in 2016 were black.

Measuring direct files across the country

Currently, 12 states and the District of Columbia allow prosecutors to make decisions on where kids end up based on a direct file statute. But one major roadblock has been measuring the consistencies and inconsistencies within the statute.

"We have pretty decent estimates of the cases that go through juvenile court, everything from race and ethnicity to age and offense. But in criminal court — the ones that go straight there because the prosecutor said so or the legislator tried to say so — largely we have no clue what those cases are all about," says Melissa Sickmund, director of the National Center for Juvenile Justice. The private, nonprofit research organization has spent 40 years collecting and analyzing data on juvenile crime and delinquency in conjunction with the federal government.

For a long time, the focus of federal and state data has been the corrections system, which has limited the ability of researchers, policymakers and juvenile justice advocates to get a clear picture of the potential and shortcomings of the adult transfer system.

Juvenile justice in most states varies from county to county, without a standardized system for documenting, analyzing and disseminating statistics on kids who commit crimes or are at risk of doing so. The tradition within the juvenile justice system has been to decide the outcomes case by case, with individual values for what is in the best interest of the child having more weight than data.

Proportion Of Girls In Juvenile Justice System Is Going Up, Studies Find

"It makes it hard to do reform," says Sickmund. "You have a good intent and say we're going to do things differently, but then a few years down the road, it's hard to say whether that was a good decision or not because you don't know where you were."

Research has shown that taking kids out of the juvenile system and putting them in the adult system makes them worse off. One way to measure the impact of direct file is through recidivism: Was a youth rearrested after being sent to adult court and dismissed? Was he reconvicted for another offense? Was it for a serious charge that would have been a felony?

In 2014, the Pew Charitable Trusts conducted a survey of juvenile corrections agencies in all 50 states as part of its Public Safety Performance Project. The survey, which focused on measuring recidivism, found that 1 in 4 states does not regularly report the data needed to assess trends in where youths end up.

The survey displays the data states were collecting at the time and their varied standards. Language to describe recidivism — and the definition of the term itself — changes from state to state and over time. No project of its nature has been done since, according to Adam Gelb, director of the Public Safety Performance Project, largely because of the level of work and coordination involved.

"There were two real takeaways from the report," Gelb says. "One was that there needs to be much greater consistency in how states are collecting this information and, second, that they've actually got to make recidivism reduction a core part of their mission, and that means tracking it; using that data to make decisions about how to respond to these kids."

States in the midst of reform

Last year saw sweeping changes across the country in the nation's direct file trend. The most dramatic shift was in California where, last November, voters approved Proposition 57, which removes the unfettered discretion given to state prosecutors. The new law requires that kids eligible for a transfer to adult court first go before a juvenile judge , who is expected to consider the youth's case and the circumstances that led to it.

Prop 57 was the result of a major effort by juvenile justice advocates, who argued that sending kids directly to adult court undermined the rehabilitative mission of the juvenile system.

They voiced concern that California's direct file statute opened the door for longer sentences and psychological trauma of being processed through adult criminal court, which meant lifelong consequences for youths and their families.

In a report , the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, a San Francisco-based nonprofit, noted disparities across counties in how the direct file statute was used, based on the political affiliations of district attorneys and the race and ethnicities of youths. According to Maureen Washburn, a policy analyst, an overall drop in juvenile crime in California helped make a case for reform. Lower numbers of youths in the system means more capacity to strengthen rehabilitative care. Less than a year into Prop 57's implementation, advocacy groups are planning to research and evaluate transfer hearings and, eventually consider phasing them out.

Juvenile Justice System Failing Native Americans, Studies Show

"The juvenile justice system in California is prepared and poised to manage all young people regardless of the seriousness of their offense in the juvenile justice system where they can truly receive the services and rehabilitation that they need to rejoin their families and community," Washburn says.

In 2016, lawmakers in Indiana approved an unprecedented state "reverse transfer" law, which allows kids sent to adult court to be placed back in a juvenile court if their adult charges are unsuccessful. The purpose of the change is to restore the possibility of exposing a kid to rehabilitative care within the juvenile justice system. In recent years, Indiana voters have reduced the number of offenses once protected under the direct file statute. Kids accused of criminal gang activity, intimidation and substance-abuse-related acts can now be seen in juvenile court.

"But we think there's still a lot more to do," says JauNae Hanger, president of the Children's Policy & Law Initiative of Indiana, a network of juvenile justice advocates.

She argues that Indiana and other states must reconsider the age at which brains have fully developed.

"What happens to the 18- to 25-year-old? Should we be treating them differently?" Hanger asks. "That's a long-term question for our state, how we treat youthful offenders systemically."

The community and change

Before landing in front of the judge 10 years ago, Marquis McKenzie had displayed the textbook signs of an "at risk youth" navigating the complexities of community in desperate need of economic resources. He vividly recalls moving with his mother when he was 8 to the Ivey Lane Homes, a housing project in Pine Hills, a predominantly black, mixed-income neighborhood on Orlando's west side. The community, once a suburban oasis for white middle class families, had earned the moniker "Crime Hills." McKenzie remembers being exposed to gang violence, drug deals, drug busts and burglaries.

Witnessing a domestic violence incident between his mother and her boyfriend ultimately drove him to get involved in street life, he says.

"She had to get eight stitches in her head. And after that, nothing else didn't really matter. That was my excuse to be harmful to people," he says.

When McKenzie was transferred to adult court, he took a youth defendant plea. Though facing 10 hard years in prison, he served two and was placed on four years of probation, which were reduced by half due to good behavior.

"Income is one of the biggest things," McKenzie, who is now 27, says of many teenagers who get in trouble. "It's kind of hard to tell them to put the gun down or stop stealing if you don't have a direct resource for them."

Today, McKenzie has two sons, ages 7 and 4. He started his own cleaning company, called The Dirt Master LLC, and has been training to teach remodeling, so he can equip youths with skills to repair their homes and, ultimately, their neighborhoods.

"A lot of people have broken sinks, tubs, holes in the walls," he says. "And I kind of strongly believe if you change the way somebody's living, you can impact their life forever."

Today, Marquis McKenzie has two sons, ages 7 and 4. He started his own cleaning company, called The Dirt Master LLC, and has been training to teach remodeling, so he can equip youths with skills to repair their homes and, ultimately, their neighborhoods. Joey Roulette hide caption

Today, Marquis McKenzie has two sons, ages 7 and 4. He started his own cleaning company, called The Dirt Master LLC, and has been training to teach remodeling, so he can equip youths with skills to repair their homes and, ultimately, their neighborhoods.

" You could consider other options"

Orange County, where McKenzie was direct filed in 2007, has the highest number of direct files in Florida. And Pine Hills, where McKenzie grew up, has the highest concentration of juvenile arrests and direct files in Florida.

With support from the state attorney's office and the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, community groups there are working to fill a gap that law enforcement cannot.

Let Your Voice Be Heard Inc. has become the biggest voice in Pine Hills, hosting job fairs, talking in schools about conflict resolution, and making on-call house visits for "crisis mentoring."

"We sit down and try to figure out what the case is with that particular individual. If we don't have the expertise that the child needs, then between 24 to 72 hours, we will contact the individuals for the parent to take the child to get further assistance for that particular situation," says Emery James, who helped found the nonprofit advocacy group with Miles Mulrain.

James was direct filed to prison at 15 for an armed robbery. Now, at 38, he is developing programs to keep kids out of the system.

In Connecticut, Project Youth Court Offers Peer-To-Peer Justice

"I've learned firsthand the detriments of negative situations and the psychological effects that it can have on a child's mind. By the grace of God, by me going through all the trials that I did, I can look back and say 'Wow, everybody's not going to make it out like that, doing 10 years or better in the system with all of the dehumanizing living conditions."

In the past five years, Florida's Department of Juvenile Justice has visibly shifted its focus to kids' unique needs based on a set of criteria including family situation, schooling, and mental and physical health histories. The agency has a sophisticated set of data available for law enforcement to make informed decisions on where it is best for a child to end up.

Ed Brodsky is state attorney for the 12th judicial circuit. In 24 years, part of them as a former assistant state attorney, he has handled dozens of criminal cases involving adults and youths. He has noticed a significant change in the prosecution model.

When asked a decade later whether a 16-year-old with McKenzie's case and circumstances would be direct filed, he responded, "You could consider other options."

Florida's direct file rate has dropped since McKenzie was sent to adult court, and it continues to. The number of youths transferred under the direct file statute has decreased by 51 percent, from 15,665 to 7,619.

For McKenzie, that is promising, but the remnants of his past still haunt him. Earlier this year, he found himself in the back of a police car for not moving his parked car and resisting arrest for it — charges that were dropped.

"It would've been another stumbling block, especially if I'd have gotten convicted for it," he says. "[Police] already still look at the past that I have. It's like 'He's not done getting in trouble,' so it would have been even more for me to try to prove my point as a citizen out here and even for other felons who haven't made it to the point where I'm at. I'm just going to keep fighting until a door opens and my voice gets heard."

Should Juveniles be Tried as Adults Essay: Exploring Both Sides of the Debate

The question of why juveniles should be tried as adults in criminal courts is a complex and controversial issue that has generated much debate in recent years. Some people argue that minors who commit serious crimes should be held accountable and face the same punishment as adults who commit the same offenses. They contend that trying juveniles as adults will serve as a deterrent to other young people who may be considering committing similar crimes.

On the other hand, others argue that juveniles are not fully developed and should not be held to the same standards as adults. They contend that young people are still developing emotionally, cognitively, and socially, and that their decision-making abilities are not yet fully formed.

Additionally, research shows that juveniles who are tried as adults are more likely to suffer from mental health problems, become repeat offenders, and experience physical and sexual abuse while in prison. Therefore, it is important to examine both sides of the debate over trying juveniles as adults and consider the implications of each position. In this essay, we will explore the arguments for and against trying juveniles as adults, as well as the potential consequences of each approach. If you need help with writing such a complicated topic, specialists at custom writing service are always ready to help with arguments on any essay theme. Because, sometimes we need qualified assistance with a complex topic.

Juveniles Should be Tried as Adults: Pros, Cons, and Implications

On the one hand, proponents of “should juveniles be tried as adults thesis statement” argue that it is necessary to hold young offenders accountable for their actions. They contend that if minors commit serious crimes such as murder, rape, or armed robbery, they should face the same consequences as adults who commit the same crimes. They also argue that trying juveniles as adults will serve as a deterrent to other young people who may be considering committing similar offenses.

Arguments Against Trying Juveniles as Adults

However, opponents of trying juveniles as adults argue that minors are not fully developed and, therefore should not be held to the same standard as adults. They contend that adolescents are still developing emotionally, cognitively, and socially, and that their decision-making abilities are not yet fully formed. Besides, research shows that juveniles who are tried as adults are more likely to suffer from mental health problems, become repeat offenders, and experience physical and sexual abuse while in prison.

The Juvenile Justice System

Another argument against trying juveniles as adults is that the juvenile justice system was created specifically to handle young offenders. The system is designed to provide rehabilitation and support for minors who have committed crimes. Trying juveniles as adults undermines the purpose of the juvenile justice system and denies young people the opportunity to receive the treatment and support they need to turn their lives around.

The question of whether juveniles should be tried as adults is a complex one. While some argue that young offenders should be held accountable for their actions, others contend that minors are not fully developed and should not be held to the same standard as adults. Ultimately, the evidence suggests that trying juveniles as adults is counterproductive and may do more harm than good. It is important to remember that young people who commit crimes are still developing and have the potential to turn their lives around with the right support and intervention. Therefore, juveniles should not be tried as adults, but instead should be given the opportunity to receive rehabilitation and support through the juvenile justice system.

Tips and Strategies for Effective Argumentation

Before you start writing, do some research to gain a comprehensive understanding of the issue. Read academic articles, news reports, and other credible sources to get a broad perspective on the topic.

Define Key Terms

Be sure to define key terms in your essays on juveniles being tried as adults, such as “juveniles” and “adults.” This will ensure that your reader understands the meaning of these terms in the context of your argument.

Present Both Sides

Be sure to present both sides of the debate, and use evidence to support each position. This will demonstrate that you have done your research and understand the issue’s complexity.

Provide Examples

Use real-life examples to illustrate your points. This can help to make your argument more compelling and relatable to your reader.

Address Counterarguments

Acknowledge counterarguments to your position, and use evidence to refute them. This will demonstrate that you have considered different perspectives on the issue and can think critically about the topic.

Consider the Implications

In addition to presenting the arguments for and against trying juveniles as adults, consider the potential consequences of each approach. This can help to demonstrate the practical implications of the issue and show why it matters.

Edit and Proofread

Once you have written your essay, be sure to edit and proofread it carefully. Check for errors in grammar, spelling, and punctuation, and make sure your writing is clear and concise. Overall, writing should juveniles be tried as adults essay requires careful research, consideration of different perspectives, and attention to detail. In general, informative essay writing it is a skill that is not easy for everyone to learn. By following these tips, you can produce a well-researched, persuasive, and compelling essay on this complex and vital issue.

Related posts:

- The Great Gatsby (Analyze this Essay Online)

- Pollution Cause and Effect Essay Sample

- Essay Sample on What Does Leadership Mean to You

- The Power of Imaging: Why I am Passionate about Becoming a Sonographer

Improve your writing with our guides

Youth Culture Essay Prompt and Discussion

Why Should College Athletes Be Paid, Essay Sample

Reasons Why Minimum Wage Should Be Raised Essay: Benefits for Workers, Society, and The Economy

Get 15% off your first order with edusson.

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

100% privacy. No spam ever.

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Youth in the Adult Criminal Justice System

The origin of the juvenile justice system was guided by the concept of rehabilitation through individualized justice (OJJDP, n.d.; Snyder and Sickmund, 2006; Robinson and Kurlychek, 2019). The juvenile court system is based on the legal principle of parens patriae or “state as parent” (Robinson and Kurlychek, 2019:37; McGowan et al., 2007:S8) and was intended to provide positive social development to youths who may not be receiving this support in their homes or communities. Over the last three decades, states have implemented various legislative changes in response to youths’ crimes, making it easier for them to be prosecuted as adults (OJJDP, n.d.; Kolivoski and Shook, 2016). This trend has contributed to increases in the numbers of youths incarcerated in adult correctional facilities (Loeffler and Grunwald, 2015; Redding, 2010).

This literature review describes the legal mechanisms by which youths can be processed and incarcerated with adults and provides the most recent data on the number of youths in adult jails and prisons. (For the purposes of this review, juveniles are defined as the population of individuals under age 18 with the potential for or actual contact with the juvenile justice system; youth refers to the general population of individuals under 18.) The review also provides a historical policy overview; discusses outcome evidence for relevant policies; presents the theoretical foundation for sending juveniles to the criminal justice system and incarcerating them with adults; highlights disparities in the transfer of juveniles to adult court; and discusses the impact of these practices and policies on youth. (In this review adult system and criminal court are used interchangeably, as are juvenile system and juvenile court. ) Additionally, the review identifies gaps in knowledge and data and offers suggestions for further research.

Definitions

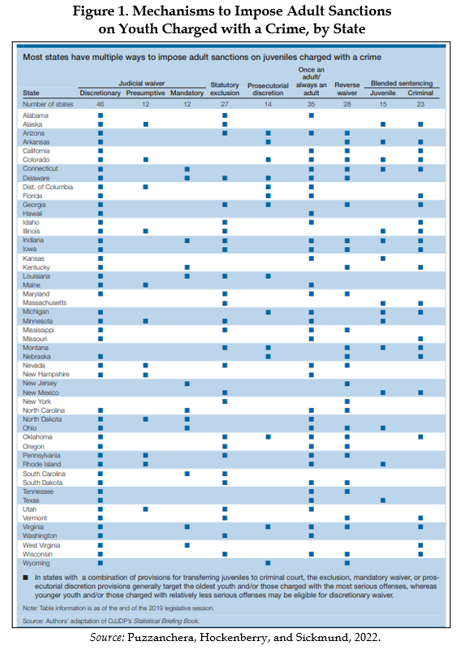

This section defines the mechanisms by which juveniles are tried and convicted in the adult criminal justice system and the facilities where they can be held. Figure 1 shows which mechanisms states use to impose adult sanctions on youths who commit crimes.

The upper age of jurisdiction is the oldest age at which a juvenile court has original jurisdiction over an individual for law-violating behavior (Statistical Briefing Book [SBB], 2021). Individual states determine the age cutoff for juvenile court jurisdiction, and the upper age is 17 in most states (SBB, 2021). (For more information on the age limits, see the Model Programs Guide literature review, Age Boundaries of the Juvenile Justice System .)

Juvenile transfer is the process of moving a case involving a juvenile (and therefore a delinquency matter) under the original jurisdiction of the juvenile court to the jurisdiction of the criminal court for trial as an adult. [The criminal court has jurisdiction only over youths who committed law-violating acts that would be criminal (delinquent acts); status offenses are limited strictly to juvenile jurisdiction.] The most common mechanisms used to transfer juveniles to adult court include judicial waiver, statutory exclusion, and direct file (Weston, 2016; Zane et al., 2016).

A judicial waiver is the mechanism whereby a juvenile court judge waives jurisdiction over a case and refers it to criminal court jurisdiction.

Statutory exclusion is a state law mandating that youths who commit certain crimes automatically are processed as adults (Dempsey, 2020; Weston, 2016; Zane et al., 2016).

Prosecutorial direct file as a mechanism of transferal means that the initial decision to bring charges against a minor in juvenile court or adult criminal court rests solely with the prosecutor or district attorney (Weston, 2016; Zane et al., 2016).