Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

The “Golden Thread” Explained Simply (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

The research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.

Research Aims: What are they?

Simply put, the research aim(s) is a statement that reflects the broad overarching goal (s) of the research project. Research aims are fairly high-level (low resolution) as they outline the general direction of the research and what it’s trying to achieve .

Research Aims: Examples

True to the name, research aims usually start with the wording “this research aims to…”, “this research seeks to…”, and so on. For example:

“This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.” “This study sets out to assess the interaction between student support and self-care on well-being in engineering graduate students”

As you can see, these research aims provide a high-level description of what the study is about and what it seeks to achieve. They’re not hyper-specific or action-oriented, but they’re clear about what the study’s focus is and what is being investigated.

Need a helping hand?

Research Objectives: What are they?

The research objectives take the research aims and make them more practical and actionable . In other words, the research objectives showcase the steps that the researcher will take to achieve the research aims.

The research objectives need to be far more specific (higher resolution) and actionable than the research aims. In fact, it’s always a good idea to craft your research objectives using the “SMART” criteria. In other words, they should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound”.

Research Objectives: Examples

Let’s look at two examples of research objectives. We’ll stick with the topic and research aims we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic:

To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation. To assess employee perceptions of digital transformation in retail HR. To identify the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR.

And for the student wellness topic:

To determine whether student self-care predicts the well-being score of engineering graduate students. To determine whether student support predicts the well-being score of engineering students. To assess the interaction between student self-care and student support when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students.

As you can see, these research objectives clearly align with the previously mentioned research aims and effectively translate the low-resolution aims into (comparatively) higher-resolution objectives and action points . They give the research project a clear focus and present something that resembles a research-based “to-do” list.

Research Questions: What are they?

Finally, we arrive at the all-important research questions. The research questions are, as the name suggests, the key questions that your study will seek to answer . Simply put, they are the core purpose of your dissertation, thesis, or research project. You’ll present them at the beginning of your document (either in the introduction chapter or literature review chapter) and you’ll answer them at the end of your document (typically in the discussion and conclusion chapters).

The research questions will be the driving force throughout the research process. For example, in the literature review chapter, you’ll assess the relevance of any given resource based on whether it helps you move towards answering your research questions. Similarly, your methodology and research design will be heavily influenced by the nature of your research questions. For instance, research questions that are exploratory in nature will usually make use of a qualitative approach, whereas questions that relate to measurement or relationship testing will make use of a quantitative approach.

Let’s look at some examples of research questions to make this more tangible.

Research Questions: Examples

Again, we’ll stick with the research aims and research objectives we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic (which would be qualitative in nature):

How do employees perceive digital transformation in retail HR? What are the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR?

And for the student wellness topic (which would be quantitative in nature):

Does student self-care predict the well-being scores of engineering graduate students? Does student support predict the well-being scores of engineering students? Do student self-care and student support interact when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students?

You’ll probably notice that there’s quite a formulaic approach to this. In other words, the research questions are basically the research objectives “converted” into question format. While that is true most of the time, it’s not always the case. For example, the first research objective for the digital transformation topic was more or less a step on the path toward the other objectives, and as such, it didn’t warrant its own research question.

So, don’t rush your research questions and sloppily reword your objectives as questions. Carefully think about what exactly you’re trying to achieve (i.e. your research aim) and the objectives you’ve set out, then craft a set of well-aligned research questions . Also, keep in mind that this can be a somewhat iterative process , where you go back and tweak research objectives and aims to ensure tight alignment throughout the golden thread.

The importance of strong alignment

Alignment is the keyword here and we have to stress its importance . Simply put, you need to make sure that there is a very tight alignment between all three pieces of the golden thread. If your research aims and research questions don’t align, for example, your project will be pulling in different directions and will lack focus . This is a common problem students face and can cause many headaches (and tears), so be warned.

Take the time to carefully craft your research aims, objectives and research questions before you run off down the research path. Ideally, get your research supervisor/advisor to review and comment on your golden thread before you invest significant time into your project, and certainly before you start collecting data .

Recap: The golden thread

In this post, we unpacked the golden thread of research, consisting of the research aims , research objectives and research questions . You can jump back to any section using the links below.

As always, feel free to leave a comment below – we always love to hear from you. Also, if you’re interested in 1-on-1 support, take a look at our private coaching service here.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

39 Comments

Thank you very much for your great effort put. As an Undergraduate taking Demographic Research & Methodology, I’ve been trying so hard to understand clearly what is a Research Question, Research Aim and the Objectives in a research and the relationship between them etc. But as for now I’m thankful that you’ve solved my problem.

Well appreciated. This has helped me greatly in doing my dissertation.

An so delighted with this wonderful information thank you a lot.

so impressive i have benefited a lot looking forward to learn more on research.

I am very happy to have carefully gone through this well researched article.

Infact,I used to be phobia about anything research, because of my poor understanding of the concepts.

Now,I get to know that my research question is the same as my research objective(s) rephrased in question format.

I please I would need a follow up on the subject,as I intends to join the team of researchers. Thanks once again.

Thanks so much. This was really helpful.

I know you pepole have tried to break things into more understandable and easy format. And God bless you. Keep it up

i found this document so useful towards my study in research methods. thanks so much.

This is my 2nd read topic in your course and I should commend the simplified explanations of each part. I’m beginning to understand and absorb the use of each part of a dissertation/thesis. I’ll keep on reading your free course and might be able to avail the training course! Kudos!

Thank you! Better put that my lecture and helped to easily understand the basics which I feel often get brushed over when beginning dissertation work.

This is quite helpful. I like how the Golden thread has been explained and the needed alignment.

This is quite helpful. I really appreciate!

The article made it simple for researcher students to differentiate between three concepts.

Very innovative and educational in approach to conducting research.

I am very impressed with all these terminology, as I am a fresh student for post graduate, I am highly guided and I promised to continue making consultation when the need arise. Thanks a lot.

A very helpful piece. thanks, I really appreciate it .

Very well explained, and it might be helpful to many people like me.

Wish i had found this (and other) resource(s) at the beginning of my PhD journey… not in my writing up year… 😩 Anyways… just a quick question as i’m having some issues ordering my “golden thread”…. does it matter in what order you mention them? i.e., is it always first aims, then objectives, and finally the questions? or can you first mention the research questions and then the aims and objectives?

Thank you for a very simple explanation that builds upon the concepts in a very logical manner. Just prior to this, I read the research hypothesis article, which was equally very good. This met my primary objective.

My secondary objective was to understand the difference between research questions and research hypothesis, and in which context to use which one. However, I am still not clear on this. Can you kindly please guide?

In research, a research question is a clear and specific inquiry that the researcher wants to answer, while a research hypothesis is a tentative statement or prediction about the relationship between variables or the expected outcome of the study. Research questions are broader and guide the overall study, while hypotheses are specific and testable statements used in quantitative research. Research questions identify the problem, while hypotheses provide a focus for testing in the study.

Exactly what I need in this research journey, I look forward to more of your coaching videos.

This helped a lot. Thanks so much for the effort put into explaining it.

What data source in writing dissertation/Thesis requires?

What is data source covers when writing dessertation/thesis

This is quite useful thanks

I’m excited and thankful. I got so much value which will help me progress in my thesis.

where are the locations of the reserch statement, research objective and research question in a reserach paper? Can you write an ouline that defines their places in the researh paper?

Very helpful and important tips on Aims, Objectives and Questions.

Thank you so much for making research aim, research objectives and research question so clear. This will be helpful to me as i continue with my thesis.

Thanks much for this content. I learned a lot. And I am inspired to learn more. I am still struggling with my preparation for dissertation outline/proposal. But I consistently follow contents and tutorials and the new FB of GRAD Coach. Hope to really become confident in writing my dissertation and successfully defend it.

As a researcher and lecturer, I find splitting research goals into research aims, objectives, and questions is unnecessarily bureaucratic and confusing for students. For most biomedical research projects, including ‘real research’, 1-3 research questions will suffice (numbers may differ by discipline).

Awesome! Very important resources and presented in an informative way to easily understand the golden thread. Indeed, thank you so much.

Well explained

The blog article on research aims, objectives, and questions by Grad Coach is a clear and insightful guide that aligns with my experiences in academic research. The article effectively breaks down the often complex concepts of research aims and objectives, providing a straightforward and accessible explanation. Drawing from my own research endeavors, I appreciate the practical tips offered, such as the need for specificity and clarity when formulating research questions. The article serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers, offering a concise roadmap for crafting well-defined research goals and objectives. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced researcher, this article provides practical insights that contribute to the foundational aspects of a successful research endeavor.

A great thanks for you. it is really amazing explanation. I grasp a lot and one step up to research knowledge.

I really found these tips helpful. Thank you very much Grad Coach.

I found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing this.

thank you so much, the explanation and examples are really helpful

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Research Group

- Job Seekers

Research Tips

Understanding the Difference between Research Questions and Objectives

January 13, 2023

When conducting research, clearly understanding the difference between research questions and objectives is important. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they refer to two distinct aspects of the research process.

Research questions are broad statements that guide the overall direction of the research. They identify the main problem or area of inquiry that the research will address. For example, a research question might be, "What is the impact of social media on teenage mental health?" This question sets the stage for the research and helps to define the scope of the study.

- Research questions are more general and open-ended, while objectives are specific and measurable.

- Research questions identify the main problem or area of inquiry, while objectives define the specific outcomes that the researcher is looking to achieve.

- Research questions help define the study's scope, while objectives help guide the research process.

- Research questions are often used to generate hypotheses or identify gaps in existing knowledge, while objectives are used to establish clear and achievable targets for the research.

- Research questions and objectives are not mutually exclusive, but well-defined research questions should lead to specific objectives necessary to answer the question.

On the other hand, research objectives are specific, measurable goals that the research aims to achieve. They are used to guide the research process and help to define the specific outcomes that the researcher is looking to achieve. For example, an objective for the above research question might be "To determine the correlation between social media usage and rates of depression in teenagers." This objective is more specific and measurable than the research question and helps define the specific outcomes that the researcher is looking to achieve.

It is important to note that research questions and objectives are not mutually exclusive; a study can have one or several questions and objectives. A well-defined research question should lead to specific objectives necessary to answer the question.

In summary, research questions and objectives are two distinct aspects of the research process. Research questions are broad statements that guide the overall direction of the research, while research objectives are specific, measurable goals that the research aims to achieve. Understanding these two terms' differences is essential for conducting effective and meaningful research.

- Call: +254725788400

- [email protected]

1.3 Research Objectives and Research Questions

By Anthony M. Wanjohi

A good research problem is that which generates a number of other research questions or objectives. After stating the research problem, you should go ahead to generated research questions or objectives. You may choose to use either research questions or objectives especially if they are referring to one and the same phenomenon.

Research questions refer to questions, which the researcher would like to be answered by carrying out the proposed study. The only difference between research questions and objectives is that research questions are stated in a question form while objectives are stated in a statement form. For an objective to be good, it should be SMART: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound.

The importance of research objectives lies in the fact that they determine:

- The kind of questions to be asked. In other words, research questions are derived from the objectives.

- The data collection and analysis procedure to be used. Data collection tools are developed from the research objectives.

- The design of the proposed study. Various research designs have different research objectives.

Using the study on Teacher and Parental Factors Affecting Students’ Academic Performance in Private Secondary Schools in Embu Municipality, Kenya as an example, you may state your research specific research objectives as follows:

- To find out the teacher factors influencing the students’ academic performance in private secondary schools in Embu Municipality?

- To find out the parental factors influencing the students’ academic performance in private secondary schools in Embu Municipality?

- To determine the extent to which teacher/parental factors affect the students’ academic performance in private secondary schools in Embu Municipality

- To find out what measures can be put in place to improve the students’ academic performance in private secondary schools in Embu Municipality

Research Questions:

From the aforementioned research objectives, the following research questions can be stated:

- What are the teachers factors influencing the students’ academic performance in private secondary schools in Embu Municipality?

- What are the parental factors influencing the students’ academic performance in private secondary Schools in Embu Municipality?

- To what extent do teacher/parental factors affect the students’ academic performance in private secondary Schools in Embu Municipality?

- What measures can be put in place to improve students’ academic performance in private secondary schools in Embu Municipality?

Note that you can choose to use either research objectives or the research questions if they are the same as it is in the given examples. But in the situation where you derive two or more research questions from one objective, you can use both research objectives and research questions in your proposed study. Read more…

Suggested Citation (APA):

Wanjohi, A.M. (2012). Research objectives and research questions. Retrieved online from at www.kenpro.org/research-objectives-and-research-questions

About KENPRO

Kenya Projects Organization is a membership organization founded and registered in Kenya in the year 2009. The main objective of the organization is to build individual and institutional capacities through project planning and management, research, publishing and IT.

Related Posts

KENPRO strengthens human and institutional capacities through providing best practices in project management, research and IT solutions, with a component of training.

Related Sites

- African Journal of Education and Social Sciences

- AfroKid Computing

- Afri Digital Marketing

- Higher Institute of Applied Learning

- Schools Net Kenya

- School Study Resources

- Writers Bureau Centre

Recent Publications

Innovative application of solar and biogas in agriculture in kenya, 6 ways to attract high-quality talent to your business, uganda solar installation capacity growth trends between 2012 and 2022, kenya solar installation capacity growth trends between 2012 and 2022, an overview of solar energy growth trends from 2012 to 2022 in the context of africa and kenya, why manager-employee relations are crucial for companies, subscription.

Subscribe below to receive updates on our publications

- +254 734 579 299

- +254 725 788 400

- General Inquiries: [email protected]

St. Marks Academy Admin Block, Off Magadi Road, P.O. Box 15509-00503, Mbagathi, Nairobi-Kenya

Kenya Projects Organization (KENPRO) is a registered membership organization in Kenya (Reg. No. KJD/N/CBO/1800168/13)

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Research Questions & Hypotheses

Generally, in quantitative studies, reviewers expect hypotheses rather than research questions. However, both research questions and hypotheses serve different purposes and can be beneficial when used together.

Research Questions

Clarify the research’s aim (farrugia et al., 2010).

- Research often begins with an interest in a topic, but a deep understanding of the subject is crucial to formulate an appropriate research question.

- Descriptive: “What factors most influence the academic achievement of senior high school students?”

- Comparative: “What is the performance difference between teaching methods A and B?”

- Relationship-based: “What is the relationship between self-efficacy and academic achievement?”

- Increasing knowledge about a subject can be achieved through systematic literature reviews, in-depth interviews with patients (and proxies), focus groups, and consultations with field experts.

- Some funding bodies, like the Canadian Institute for Health Research, recommend conducting a systematic review or a pilot study before seeking grants for full trials.

- The presence of multiple research questions in a study can complicate the design, statistical analysis, and feasibility.

- It’s advisable to focus on a single primary research question for the study.

- The primary question, clearly stated at the end of a grant proposal’s introduction, usually specifies the study population, intervention, and other relevant factors.

- The FINER criteria underscore aspects that can enhance the chances of a successful research project, including specifying the population of interest, aligning with scientific and public interest, clinical relevance, and contribution to the field, while complying with ethical and national research standards.

- The P ICOT approach is crucial in developing the study’s framework and protocol, influencing inclusion and exclusion criteria and identifying patient groups for inclusion.

- Defining the specific population, intervention, comparator, and outcome helps in selecting the right outcome measurement tool.

- The more precise the population definition and stricter the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the more significant the impact on the interpretation, applicability, and generalizability of the research findings.

- A restricted study population enhances internal validity but may limit the study’s external validity and generalizability to clinical practice.

- A broadly defined study population may better reflect clinical practice but could increase bias and reduce internal validity.

- An inadequately formulated research question can negatively impact study design, potentially leading to ineffective outcomes and affecting publication prospects.

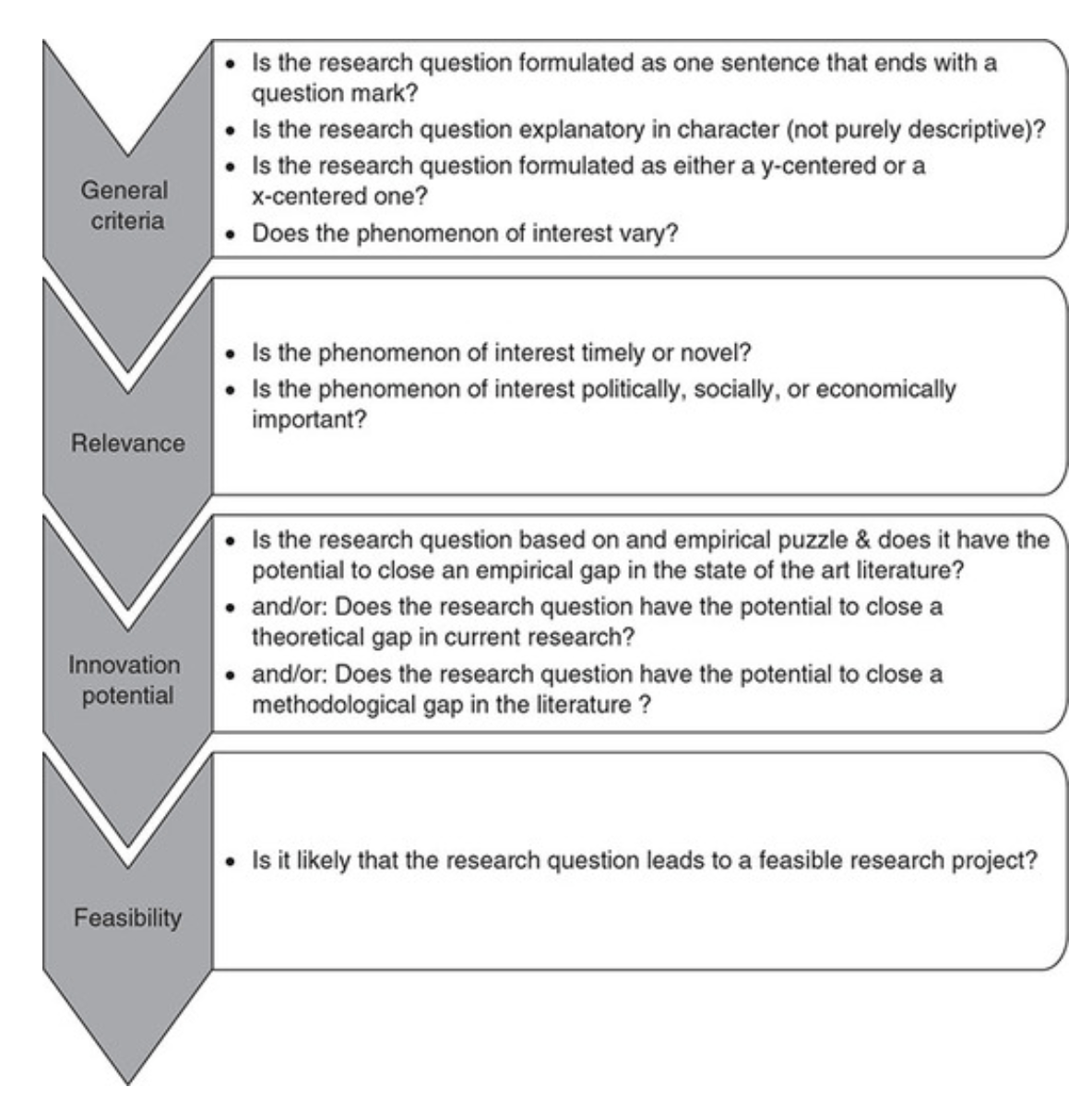

Checklist: Good research questions for social science projects (Panke, 2018)

Research Hypotheses

Present the researcher’s predictions based on specific statements.

- These statements define the research problem or issue and indicate the direction of the researcher’s predictions.

- Formulating the research question and hypothesis from existing data (e.g., a database) can lead to multiple statistical comparisons and potentially spurious findings due to chance.

- The research or clinical hypothesis, derived from the research question, shapes the study’s key elements: sampling strategy, intervention, comparison, and outcome variables.

- Hypotheses can express a single outcome or multiple outcomes.

- After statistical testing, the null hypothesis is either rejected or not rejected based on whether the study’s findings are statistically significant.

- Hypothesis testing helps determine if observed findings are due to true differences and not chance.

- Hypotheses can be 1-sided (specific direction of difference) or 2-sided (presence of a difference without specifying direction).

- 2-sided hypotheses are generally preferred unless there’s a strong justification for a 1-sided hypothesis.

- A solid research hypothesis, informed by a good research question, influences the research design and paves the way for defining clear research objectives.

Types of Research Hypothesis

- In a Y-centered research design, the focus is on the dependent variable (DV) which is specified in the research question. Theories are then used to identify independent variables (IV) and explain their causal relationship with the DV.

- Example: “An increase in teacher-led instructional time (IV) is likely to improve student reading comprehension scores (DV), because extensive guided practice under expert supervision enhances learning retention and skill mastery.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: The dependent variable (student reading comprehension scores) is the focus, and the hypothesis explores how changes in the independent variable (teacher-led instructional time) affect it.

- In X-centered research designs, the independent variable is specified in the research question. Theories are used to determine potential dependent variables and the causal mechanisms at play.

- Example: “Implementing technology-based learning tools (IV) is likely to enhance student engagement in the classroom (DV), because interactive and multimedia content increases student interest and participation.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: The independent variable (technology-based learning tools) is the focus, with the hypothesis exploring its impact on a potential dependent variable (student engagement).

- Probabilistic hypotheses suggest that changes in the independent variable are likely to lead to changes in the dependent variable in a predictable manner, but not with absolute certainty.

- Example: “The more teachers engage in professional development programs (IV), the more their teaching effectiveness (DV) is likely to improve, because continuous training updates pedagogical skills and knowledge.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: This hypothesis implies a probable relationship between the extent of professional development (IV) and teaching effectiveness (DV).

- Deterministic hypotheses state that a specific change in the independent variable will lead to a specific change in the dependent variable, implying a more direct and certain relationship.

- Example: “If the school curriculum changes from traditional lecture-based methods to project-based learning (IV), then student collaboration skills (DV) are expected to improve because project-based learning inherently requires teamwork and peer interaction.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: This hypothesis presumes a direct and definite outcome (improvement in collaboration skills) resulting from a specific change in the teaching method.

- Example : “Students who identify as visual learners will score higher on tests that are presented in a visually rich format compared to tests presented in a text-only format.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis aims to describe the potential difference in test scores between visual learners taking visually rich tests and text-only tests, without implying a direct cause-and-effect relationship.

- Example : “Teaching method A will improve student performance more than method B.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis compares the effectiveness of two different teaching methods, suggesting that one will lead to better student performance than the other. It implies a direct comparison but does not necessarily establish a causal mechanism.

- Example : “Students with higher self-efficacy will show higher levels of academic achievement.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis predicts a relationship between the variable of self-efficacy and academic achievement. Unlike a causal hypothesis, it does not necessarily suggest that one variable causes changes in the other, but rather that they are related in some way.

Tips for developing research questions and hypotheses for research studies

- Perform a systematic literature review (if one has not been done) to increase knowledge and familiarity with the topic and to assist with research development.

- Learn about current trends and technological advances on the topic.

- Seek careful input from experts, mentors, colleagues, and collaborators to refine your research question as this will aid in developing the research question and guide the research study.

- Use the FINER criteria in the development of the research question.

- Ensure that the research question follows PICOT format.

- Develop a research hypothesis from the research question.

- Ensure that the research question and objectives are answerable, feasible, and clinically relevant.

If your research hypotheses are derived from your research questions, particularly when multiple hypotheses address a single question, it’s recommended to use both research questions and hypotheses. However, if this isn’t the case, using hypotheses over research questions is advised. It’s important to note these are general guidelines, not strict rules. If you opt not to use hypotheses, consult with your supervisor for the best approach.

Farrugia, P., Petrisor, B. A., Farrokhyar, F., & Bhandari, M. (2010). Practical tips for surgical research: Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie , 53 (4), 278–281.

Hulley, S. B., Cummings, S. R., Browner, W. S., Grady, D., & Newman, T. B. (2007). Designing clinical research. Philadelphia.

Panke, D. (2018). Research design & method selection: Making good choices in the social sciences. Research Design & Method Selection , 1-368.

Difference between Research Questions and Research Objectives

When embarking on a research project, it’s important to have a clear understanding of the distinction between research questions and research objectives. Both are key components of a research study, but they differ in their focus and purpose.

The main difference is that research questions focus on the general purpose or aim of the study whereas research objectives provide specific, measurable, and attainable steps to achieve the research questions.

Before we move to the differences, let’s understand what are Research Questions and Research Objectives:

- Research Questions : Research questions refer to the overarching goals or aims of a research project. They typically describe the main topic or issue being investigated and the questions that the researcher aims to answer.

- Research Objectives : Research objectives refer to specific steps or goals that the researcher aims to achieve in order to answer the research questions. These objectives should be clearly defined, measurable, and achievable.

Now, let’s move to Research Questions vs Research Objectives:

Major differences between Research Questions and Research Objectives

Note that sometimes, the question might also be asked as “distinguish between Research Questions and Research Objectives”.

- Difference between Purpose and Objective

- Difference between Aim and Objective

- Difference between Members of Legislative Assembly (MLA) and Members of Legislative Council (MLC)

Final words

Research questions and research objectives are related, they are not interchangeable terms. Research questions describe the goals or aims of a study in a broader sense, while research objectives provide specific, measurable, achievable steps to achieve those goals.

Understanding the difference between these two terms can help you design and execute a more effective research study.

You can view other “differences between” posts by clicking here .

If you have a related query, feel free to let us know in the comments below.

Also, kindly share the information with your friends who you think might be interested in reading it.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Formulating Research Aims and Objectives

Formulating research aim and objectives in an appropriate manner is one of the most important aspects of your thesis. This is because research aim and objectives determine the scope, depth and the overall direction of the research. Research question is the central question of the study that has to be answered on the basis of research findings.

Research aim emphasizes what needs to be achieved within the scope of the research, by the end of the research process. Achievement of research aim provides answer to the research question.

Research objectives divide research aim into several parts and address each part separately. Research aim specifies WHAT needs to be studied and research objectives comprise a number of steps that address HOW research aim will be achieved.

As a rule of dumb, there would be one research aim and several research objectives. Achievement of each research objective will lead to the achievement of the research aim.

Consider the following as an example:

Research title: Effects of organizational culture on business profitability: a case study of Virgin Atlantic

Research aim: To assess the effects of Virgin Atlantic organizational culture on business profitability

Following research objectives would facilitate the achievement of this aim:

- Analyzing the nature of organizational culture at Virgin Atlantic by September 1, 2022

- Identifying factors impacting Virgin Atlantic organizational culture by September 16, 2022

- Analyzing impacts of Virgin Atlantic organizational culture on employee performances by September 30, 2022

- Providing recommendations to Virgin Atlantic strategic level management in terms of increasing the level of effectiveness of organizational culture by October 5, 2022

Figure below illustrates additional examples in formulating research aims and objectives:

Formulation of research question, aim and objectives

Common mistakes in the formulation of research aim relate to the following:

1. Choosing the topic too broadly . This is the most common mistake. For example, a research title of “an analysis of leadership practices” can be classified as too broad because the title fails to answer the following questions:

a) Which aspects of leadership practices? Leadership has many aspects such as employee motivation, ethical behaviour, strategic planning, change management etc. An attempt to cover all of these aspects of organizational leadership within a single research will result in an unfocused and poor work.

b) An analysis of leadership practices in which country? Leadership practices tend to be different in various countries due to cross-cultural differences, legislations and a range of other region-specific factors. Therefore, a study of leadership practices needs to be country-specific.

c) Analysis of leadership practices in which company or industry? Similar to the point above, analysis of leadership practices needs to take into account industry-specific and/or company-specific differences, and there is no way to conduct a leadership research that relates to all industries and organizations in an equal manner.

Accordingly, as an example “a study into the impacts of ethical behaviour of a leader on the level of employee motivation in US healthcare sector” would be a more appropriate title than simply “An analysis of leadership practices”.

2. Setting an unrealistic aim . Formulation of a research aim that involves in-depth interviews with Apple strategic level management by an undergraduate level student can be specified as a bit over-ambitious. This is because securing an interview with Apple CEO Tim Cook or members of Apple Board of Directors might not be easy. This is an extreme example of course, but you got the idea. Instead, you may aim to interview the manager of your local Apple store and adopt a more feasible strategy to get your dissertation completed.

3. Choosing research methods incompatible with the timeframe available . Conducting interviews with 20 sample group members and collecting primary data through 2 focus groups when only three months left until submission of your dissertation can be very difficult, if not impossible. Accordingly, timeframe available need to be taken into account when formulating research aims and objectives and selecting research methods.

Moreover, research objectives need to be formulated according to SMART principle,

where the abbreviation stands for specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound.

Examples of SMART research objectives

At the conclusion part of your research project you will need to reflect on the level of achievement of research aims and objectives. In case your research aims and objectives are not fully achieved by the end of the study, you will need to discuss the reasons. These may include initial inappropriate formulation of research aims and objectives, effects of other variables that were not considered at the beginning of the research or changes in some circumstances during the research process.

John Dudovskiy

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Velentgas P, Dreyer NA, Nourjah P, et al., editors. Developing a Protocol for Observational Comparative Effectiveness Research: A User's Guide. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013 Jan.

Developing a Protocol for Observational Comparative Effectiveness Research: A User's Guide.

- Hardcopy Version at Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Chapter 1 Study Objectives and Questions

Scott R Smith , PhD.

The steps involved in the process of developing research questions and study objectives for conducting observational comparative effectiveness research (CER) are described in this chapter. It is important to begin with identifying decisions under consideration, determining who the decisionmakers and stakeholders in the specific area of research under study are, and understanding the context in which decisions are being made. Synthesizing the current knowledge base and identifying evidence gaps is the next important step in the process, followed by conceptualizing the research problem, which includes developing questions that address the gaps in existing evidence. Understanding the stage of knowledge that the study is designed to address will come from developing these initial questions. Identifying which questions are critical to reduce decisional uncertainty and minimize gaps in the current knowledge base is an important part of developing a successful framework. In particular, it is beneficial to look at what study populations, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, timeframe, and settings (PICOTS framework) are most important to decisionmakers in weighing the balance of harms and benefits of action. Some research questions are easier to operationalize than others, and study limitations should be recognized and accepted from an early stage. The level of new scientific evidence that is required by the decisionmaker to make a decision or to take action must be recognized. Lastly, the magnitude of effect must be specified. This can mean defining what is a clinically meaningful difference in the study endpoints from the perspective of the decisionmaker and/or defining what is a meaningful difference from the patient's perspective.

The foundation for designing a new research protocol is the study's objectives and the questions that will be investigated through its implementation. All aspects of study design and analysis are based on the objectives and questions articulated in a study's protocol. Consequently, it is exceedingly important that a study's objectives and questions be formulated meticulously and written precisely in order for the research to be successful in generating new knowledge that can be used to inform health care decisions and actions.

An important aspect of CER 1 and other forms of translational research is the potential for early involvement and inclusion of patients and other stakeholders to collaborate with researchers in identifying study objectives, key questions, major study endpoints, and the evidentiary standards that are needed to inform decisionmaking. The involvement of stakeholders in formulating the research questions increases the applicability of the study to the end-users and facilitates appropriate translation of the results into health care practice and use by patient communities. While stakeholders may be defined in multiple ways, for the purposes of this User's Guide , a broad definition will be used. Hence, stakeholders are defined as individuals or organizations that use scientific evidence for decisionmaking and therefore have an interest in the results of new research. Implicit in this definition of stakeholders is the importance for stakeholders to understand the scientific process, including considerations of bioethics and the limitations of research, particularly with regard to studies involving human subjects. Ideally, stakeholders also should express commitment to using objective scientific evidence to inform their decisionmaking and recognize that disregarding sound scientific methods often will undermine decisionmaking. For stakeholder organizations, it is also advantageous if the organization has well-established processes for transparently reviewing and incorporating research findings into decisions as well as organized channels for disseminating research results.

There are at least seven essential steps in the conceptualization and development of a research question or set of questions for an observational CER protocol. These steps are presented as a general framework in Table 1.1 below and elaborated upon in the subsequent sections of this chapter. The framework is based on the principle that researchers and stakeholders will work together to objectively lay out the research problems, research questions, study objectives, and key parameters for which scientific evidence is needed to inform decisionmaking or health care actions. The intent of this framework is to facilitate communication between researchers and stakeholders in conceptualizing the research problem and the design of a study (or a program of research involving a series of studies) in order to maximize the potential that new knowledge will be created from the research with results that can inform decisionmaking. To do this, research results must be relevant, applicable, unbiased and sufficient to meet the evidentiary threshold for decisionmaking or action by stakeholders. In order for the results to be valid and credible, all persons involved must be committed to protecting the integrity of the research from bias and conflicts of interest. Most importantly, the study must be designed to protect the rights, welfare, and well-being of subjects involved in the research.

Framework for developing and conceptualizing a CER protocol.

- Identifying Decisions, Decisionmakers, Actions, and Context

In order for research findings to be useful for decisionmaking, the study protocol should clearly articulate the decisions or actions for which stakeholders seek new scientific evidence. While only some studies may be sufficiently robust for making decisions or taking action, statements that describe the stakeholders' decisions will help those who read the protocol understand the rationale for the study and its potential for informing decisions or for translating the findings into changes in health care practices. This information also improves the ability of protocol readers to understand the purpose of the study so they can critically review its design and provide recommendations for ways it may be potentially improved. If stakeholders have a need to make decisions within a critical time frame for regulatory, ethical, or other reasons, this interval should be expressed to researchers and described in the protocol. In some cases, the time frame for decisionmaking may influence the choice of outcomes that can be studied and the study designs that can be used. For some stakeholders' questions, research and decisionmaking may need to be divided into stages, since it may take years for outcomes with long lag times to occur, and research findings will be delayed until they do.

In writing this section of the protocol, investigators should ask stakeholders to describe the context in which the decision will be made or actions will be taken. This context includes the background and rationale for the decision, key areas of uncertainty and controversies surrounding the decision, ways scientific evidence will be used to inform the decision, the process stakeholders will use to reach decisions based on scientific evidence, and a description of the key stakeholders who will use or potentially be affected by the decision. By explaining these contextual factors that surround the decision, investigators will be able to work with stakeholders to determine the study objectives and other major parameters of the study. This work also provides the opportunity to discuss how the tools of science can be applied to generate new evidence for informing stakeholder decisions and what limits may exist in those tools. In addition, this initial step begins to clarify the number of analyses necessary to generate the evidence that stakeholders need to make a decision or take other actions with sufficient certainty about the outcomes of interest. Finally, the contextual information facilitates advance planning and discussions by researchers and stakeholders about approaches to translation and implementation of the study findings once the research is completed.

- Synthesizing the Current Knowledge Base

In designing a new study, investigators should conduct a comprehensive review of the literature, critically appraise published studies, and synthesize what is known related to the research objectives. Specifically, investigators should summarize in the protocol what is known about the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of the interventions and about the outcomes being studied. Furthermore, investigators should discuss measures used in prior research and whether these measures have changed over time. These descriptions will provide background on the knowledge base for the current protocol. It is equally important to identify which elements of the research problem are unknown because evidence is absent, insufficient, or conflicting.

For some research problems, systematic reviews of the literature may be available and can be useful resources to guide the study design. The AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Centers 2 and the Cochrane Collaboration 3 are examples of established programs that conduct thorough systematic reviews, technology assessments, and specialized comparative effectiveness reviews using standardized methods. When available, systematic reviews and technology assessments should be consulted as resources for investigators to assess the current knowledge base when designing new studies and working with stakeholders.

When reviewing the literature, investigators and stakeholders should identify the most relevant studies and guidelines about the interventions that will be studied. This will allow readers to understand how new research will add to the existing knowledge base. If guidelines are a source of information, then investigators should examine whether these guidelines have been updated to incorporate recent literature. In addition, investigators should assess the health sciences literature to determine what is known about expected effects of the interventions based on current understanding of the pathophysiology of the target condition. Furthermore, clinical experts should be consulted to help identify gaps in current knowledge based on their expertise and interactions with patients. Relevant questions to ask to assess the current knowledge base for development of an observational CER study protocol are:

- What are the most relevant studies and guidelines about the interventions, and why are these studies relevant to the protocol (e.g., because of the study findings, time period conducted, populations studied, etc.)?

- Are there differences in recommendations from clinical guidelines that would indicate clinical equipoise?

- What else is known about the expected effects of the interventions based on current understanding of the pathophysiology of the targeted condition?

- What do clinical experts say about gaps in current knowledge?

- Conceptualizing the Research Problem

In designing studies for addressing stakeholder questions, investigators should engage multiple stakeholders in discussions about how the research problem is conceptualized from the stakeholders' perspectives. These discussions will aid in designing a study that can be used to inform decisionmaking. Together, investigators and stakeholders should work collaboratively to determine the major objectives of the study based on the health care decisions facing stakeholders. As pointed out by Heckman, 4 research objectives should be formalized outside considerations of available data and the inferences that can be made from various statistical estimation approaches. Doing so will allow the study objectives to be determined by stakeholder needs rather than the availability of existing data. A thorough discussion of these considerations is beyond the scope of this chapter, but some important considerations are summarized in supplement 1 of this User's Guide.

In order to conceptualize the problem, stakeholders and other experts should be asked to describe the potential relationships between the intervention and important health outcomes. This description will help researchers develop preliminary hypotheses about the stated relationships. Likewise, stakeholders, researchers, and other experts should be asked to enumerate all major assumptions that affect the conceptualization of the research problem, but will not be directly examined in the study. These assumptions should be described in the study protocol and in reporting final study results. By clearly stating the assumptions, protocol reviewers will be better able to assess how the assumptions may influence the study results.

Based on the conceptualization of the research problem, investigators and stakeholders should make use of applicable scientific theory in designing the study protocol and developing the analytic plan. Research that is designed using a validated theory has a higher potential to reach valid conclusions and improve the overall understanding of a phenomenon. In addition, theory will aid in the interpretation of the study findings, since these results can be put in context with the theory and with past research. Depending on the nature of the inquiry, theory from specific disciplines such as health behavior, sociology, or biology could be the basis for designing the study. In addition, the research team should work with stakeholders to develop a conceptual model or framework to guide the implementation of the study. The protocol should also contain one or more figures that summarize the conceptual model or framework as it applies to the study. These figures will allow readers to understand the theoretical or conceptual basis for the study and how the theory is operationalized for the specific study. The figures should diagram relationships between study variables and outcomes to help readers of the protocol visualize relationships that will be examined in the study.

For research questions about causal associations between exposures and outcomes, causal models such as directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) may be useful tools in designing the conceptual framework for the study and developing the analytic plan. The value of DAGs in the context of refining study questions is that they make assumptions explicit in ways that can clarify gaps in knowledge. Free software such as DAGitty is available for creating, editing, and analyzing causal models. A thorough discussion of DAGs is beyond the scope of this chapter, but more information about DAGs is available in supplement 2 of this User's Guide.

The following list of questions may be useful for defining and describing a study's conceptual framework in a CER protocol:

- What are the main objectives of the study, as related to specific decisions to be made?

- What are the major assumptions of decisionmakers, investigators, and other experts about the problem or phenomenon being studied?

- What relationships, if any, do experts hypothesize exist between interventions and outcomes?

What is known about each element of the model?

Can relationships be expressed by causal diagrams?

- Determining the Stage of Knowledge Development for the Study Design

The scientific method is a process of observation and experimentation in order for the evidence base to be expanded as new knowledge is developed. Therefore, stakeholders and investigators should consider whether a program of research comprising a sequential or concurrent series of studies, rather than a single study, is needed to adequately make a decision. Staging the research into multiple studies and making interim decisions may improve the final decision and make judicious use of scarce research resources. In some cases, the results of preliminary studies, descriptive epidemiology, or pilot work may be helpful in making interim decisions and designing further research. Overall, a planned series of related studies or a program of research may be needed to adequately address stakeholders' decisions.

An example of a structured program of research is the four phases of clinical studies used by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to reach a decision about whether or not a new drug is safe and efficacious for market approval in the United States. Using this analogy, the final decision about whether a drug is efficacious and safe to be marketed for specific medical indications is based upon the accumulation of scientific evidence from a series of studies (i.e., not from any individual study), which are conducted in multiple sequential phases. The evidence generated in each phase is reviewed to make interim decisions about the safety and efficacy of a new pharmaceutical until ultimately all the evidence is reviewed to make a final decision about drug approval.

Under the FDA model for decisionmaking, initial research involves laboratory and animal tests. If the evidence generated in these studies indicates that the drug is active and not toxic, the sponsor submits an application to the FDA for an “investigational new drug.” If the FDA approves, human testing for safety and efficacy can begin. The first phase of human testing is usually conducted in a limited number of healthy volunteers (phase 1). If these trials show evidence that the product is safe in healthy volunteers, then the drug is further studied in a small number of volunteers who have the targeted condition (phase 2). If phase 2 studies show that the drug has a therapeutic effect and lacks significant adverse effects, trials with large numbers of people are conducted to determine the drug's safety and efficacy (phase 3). Following these trials, all relevant scientific studies are submitted to the FDA for a decision about whether the drug should be approved for marketing. If there are additional considerations like special safety issues, observational studies may be required to assess the safety of the drug in routine clinical care after the drug is approved for marketing (phase 4). Overall, the decisionmaking and research are staged so that the cumulative findings from all studies are used by the FDA to make interim decisions until the final decision is made about whether a medical product will be approved for marketing.

While most decisions about the comparative effectiveness of interventions will not need such extensive testing, it still may be prudent to stage research in a way that allows for interim decisions and sequentially more rigorous studies. On the other hand conditional approval or interim decisions may risk confusing patients and other stakeholders about the extent to which current evidence indicates that a treatment is effective and safe for all individuals with a health condition. For instance, under this staged approach new treatments could rapidly diffuse into a market even when there is limited evidence of long-term effectiveness and safety for all potential users. An illustrative example of this is the case of lung-volume reduction surgery, which was increasingly being used to treat severe emphysema despite limited evidence supporting its safety and efficacy until new research raised questions about the safety of the procedure. 6

Below is one potential categorization for the stages of knowledge development as related to informing decisions about questions of comparative effectiveness:

- Descriptive analysis

- Hypothesis generation

- Feasibility studies/proof of concept

- Hypothesis supporting

- Hypothesis testing

The first stages (i.e., descriptive analysis, hypothesis generation, and feasibility studies) are not mutually exclusive and usually are not intended to provide conclusive results for most decisions. Instead these stages provide preliminary evidence or feasibility testing before larger, more resource-intensive studies are launched. Results from these categories of studies may allow for interim decisionmaking (e.g., conditional approval for reimbursement of a treatment while further research is conducted). While a phased approach to research may postpone the time when a conclusive decision can be reached it does help to conserve resources such as those that may be consumed in launching a large multicenter study when a smaller study may be sufficient. Investigators will need to engage stakeholders to prioritize what stage of research may be most useful for the practical range of decisions that will be made.

Investigators should discuss in the protocol what stage of knowledge the current study will fulfill in light of the actions available to different stakeholders. This will allow reviewers of the protocol to assess the degree to which the evidence generated in the study holds the potential to fill specific knowledge gaps. For studies that are described in the protocol as preliminary, this may also help readers understand other tradeoffs that were made in the design of the study, in terms of methodological limitations that were accepted a priori in order to gather preliminary information about the research questions.

- Defining and Refining Study Questions Using PICOTS Framework

As recommended in other AHRQ methods guides, 7 investigators should engage stakeholders in a dialogue in order to understand the objectives of the research in practical terms, particularly so that investigators know the types of decisions that the research may affect. In working with stakeholders to develop research questions that can be studied with scientific methods, investigators may ask stakeholders to identify six key components of the research questions that will form the basis for designing the study. These components are reflected in the PICOTS typology and are shown below in Table 1.2 . These components represent the critical elements that will help investigators design a study that will be able to address the stakeholders' needs. Additional references that expand upon how to frame research questions can be found in the literature. 8 - 9

PICOTS typology for developing research questions.

The PICOTS typology outlines the key parts of the research questions that the study will be designed to address. 10 As a new research protocol is developed these questions can be presented in preliminary form and refined as other steps in the process are implemented. After the preliminary questions are refined, investigators should examine the questions to make sure that they will meet the needs of the stakeholders. In addition, they should assess whether the questions can be answered within the timeframe allotted and with the resources that are available for the study.

Since stakeholders ultimately determine effectiveness, it is important for investigators to ensure that the study endpoints and outcomes will meet their needs. Stakeholders need to articulate to investigators the health outcomes that are most important for a particular stakeholder to make decisions about treatment or take other health care actions. The endpoints that stakeholders will use to determine effectiveness may vary considerably. Unlike efficacy trials, in which clinical endpoints and surrogate measures are frequently used to determine efficacy, effectiveness may need to be determined based on several measures, many of which are not biological. These endpoints may be categorized as clinical endpoints, patient-reported outcomes and quality of life, health resource utilization, and utility measures. Types of measures that could be used are mortality, morbidity and adverse effects, quality of life, costs, or multiple outcomes. Chapter 6 gives a more extensive discussion of potential outcome measures of effectiveness.

The reliability, validity, and accuracy of study instruments to validly measure the concepts they purport to measure will also need to be acceptable to stakeholders. For instance, if stakeholders are interested in quality of life as an outcome, but do not believe there is an adequate measure of quality of life, then measurement development may need to be done prior to study initiation or other measures will need to be identified by stakeholders.

- Discussing Evidentiary Need and Uncertainty

Investigators and stakeholders should discuss the tradeoffs of different study designs that may be used for addressing the research questions. This dialogue will help researchers design a study that will be relevant and useful to the needs of stakeholders. All study designs have strengths and weaknesses, the latter of which may limit the conclusiveness of the final study results. Likewise, some decisions may require evidence that cannot be obtained from certain designs. In addition to design weaknesses, there are also practical tradeoffs that need to be considered in terms of research resources, like the time needed to complete the study, the availability of data, investigator expertise, subject recruitment, human subjects protection, research budget, difference to be detected, and lost-opportunity costs of doing the research instead of other studies that have priority for stakeholders. An important decision that will need to be made is whether or not randomization is needed for the questions being studied. There are several reasons why randomization might be needed, such as determining whether an FDA-approved drug can be used for a new use or indication that was not studied as part of the original drug approval process. A paper by Concato includes a thorough discussion of issues to consider when deciding whether randomization is necessary. 11

In discussing the tradeoffs of different study designs, researchers and stakeholders may wish to discuss the principal goals of research and ensure that researchers and stakeholders are aligned in their understanding of what is meant by scientific evidence. Fundamentally, research is a systematic investigation that uses scientific methods to measure, collect, and analyze data for the advancement of knowledge. This advancement is through the independent peer review and publication of study results, which are collectively referred to as scientific evidence. One definition of scientific evidence has been proposed by Normand and McNeil 12 as:

… the accumulation of information to support or refute a theory or hypothesis. … The idea is that assembling all the available information may reduce uncertainty about the effectiveness of the new technology compared to existing technologies in a setting where we believe particular relationships exist but are uncertain about their relevance …

While the primary aim of research is to produce new knowledge , the Normand and McNeil concept of evidence emphasizes that research helps create knowledge by reducing uncertainty about outcomes. However, rarely, if at all, does research eliminate all uncertainty around most decisions. In some cases, successful research will answer an important question and reduce uncertainty related to that question, but it may also increase uncertainty by leading to more, better informed questions regarding unknowns. As a result, nearly all decisions face some level of uncertainty even in a field where a body of research has been completed. This distinction is also critical because it helps to separate the research and subsequent actions that decisionmakers may take based on their assessment of the research results. Those subsequent actions may be informed by the research findings but will also be based on stakeholders' values and resources. Hence, as the definition by Normand and McNeil implies, research generates evidence but stakeholders decide whether to act on the evidence. Scientific evidence informs decisions to the extent it can adequately reduce the uncertainty about the problem for the stakeholder. Ultimately, treatment decisions are only guided by an assessment of the certainty that a course of therapy will lead to the outcomes of interest and the likelihood that this conclusion will be affected by the results of future studies.

In conceptualizing a study design, it is important for investigators to understand what constitutes sufficient and valid evidence from the stakeholder's perspective. In other words, what is the type of evidence that will be required to inform the stakeholder's decision to act or make a conscious decision not to take action? Evidence needed for action may vary by type of stakeholder and the scope of decisions that the stakeholder is making. For instance, a stakeholder who is making a population-based decision such as whether to provide insurance coverage for a new medical device with many alternatives may need substantially robust research findings in order to take action and provide that insurance coverage. In this example, the stakeholder may only accept as evidence a study with strong internal validity and generalizability (i.e., one conducted in a nationally representative sample of patients with the disease). On the other hand a patient who has a health condition where there are few treatments may be willing to accept lower-quality evidence in order to make a decision about whether to proceed with treatment despite a higher level of uncertainty about the outcome.

In many cases, there may exist a gradient of actions that can be taken based on available evidence. Quanstrum and Hayward 13 have discussed this gradient and argued that health care decisionmaking is changing, partly because more information is available to patients and other stakeholders about treatment options. As shown in the upper panel (A) in Figure 1.1 , many people may currently believe that health care treatment decisions are basically uniform for most people and under most circumstances. Panel A represents a hypothetical treatment whereby there is an evidentiary threshold or a point at which treatment is always beneficial and should be recommended. On the other hand below this threshold care provides no benefits and treatment should be discouraged. Quanstrum and Hayward argue that increasingly health care decisions are more like the lower panel (B). This panel portrays health care treatments as providing a large zone of discretion where benefits may be low or modest for most people. While above this zone treatment may always be recommended, individuals who fall within the zone may have questionable health benefits from treatment. As a result, different decisionmakers may take different actions based on their individual preferences.

Conceptualization of clinical decisionmaking. See Quanstrum KH, Hayward RA (Reference #). This figure is copyrighted by the Massachusetts Medical Society and reprinted with permission.

In light of this illustration, the following questions are suggested for discussion with stakeholders to help elicit the amount of uncertainty that is acceptable so that the study design can reach an appropriate level of evidence for the decision at hand:

- What level of new scientific evidence does the decisionmaker need to make a decision or take action?

- What quality of evidence is needed for the decisionmaker to act?

- What level of certainty of the outcome is needed by the decisionmaker(s)?

- How specific does the evidence need to be?

- Will decisions require consensus of multiple parties?

Additional Considerations When Considering Evidentiary Needs

As mentioned earlier, different stakeholders may disagree on the usefulness of different research designs, but it should be pointed out that this disagreement may be because stakeholders have different scopes of decisions to make. For example, high-quality research that is conclusive may be needed to make a decision that will affect the entire nation. On the other hand, results with more uncertainty as to the magnitude of the effect estimate(s) may be acceptable in making some decisions such as those affecting fewer people or where the risks to health are low. Often this disagreement occurs when different stakeholders debate whether evidence is needed from a new randomized controlled trial or whether evidence can be obtained from an analysis of an existing database. In this debate, both sides need to clarify whether they are facing the same decision or the decisions are different, particularly in terms of their scope.

Groups committed to evidence-based decisionmaking recognize that scientific evidence is only one component of the process of making decisions. Evidence generation is the goal of research, but evidence alone is not the only facet of evidence-based decisionmaking. In addition to scientific evidence, decisionmaking involves the consideration of (a) values, particularly the values placed on benefits and harms, and (b) resources. 14 Stakeholder differences in values and resources may mean that different decisions are made based on the same scientific evidence. Moreover, differences in values may create conflict in the decisionmaking process. One stakeholder may believe a particular study outcome is most important from their perspective, while another stakeholder may believe a different outcome is the most important for determining effectiveness.

Likewise, there may be inherent conflicts in values between individual decisionmaking and population decisionmaking, even though these decisions are often interrelated. For example, an individual may have a higher tolerance for treatment risk in light of the expected treatment benefits for him or her. On the other hand a regulatory health authority may determine that the population risk is too great without sufficient evidence that treatment provides benefits to the population. An example of this difference in perspective can be seen with how different decisionmakers responded to evidence about the drug Avastin ® (bevacizumab) for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. In this case, the FDA revoked their approval of the breast cancer indication for Avastin after concluding that the drug had not been shown to be safe and effective for that use. Nonetheless, Medicare, the public insurance program for the elderly and disabled continued to allow coverage when a physician prescribes the drug, even for breast cancer. Likewise, some patient groups were reported to be concerned by the decision since it presumably would deny some women access to Avastin treatment. For a more thorough discussion of these issues around differences in perspective, the reader is referred to an article by Atkins 15 and the examples in Table 1.3 below.

Examples of individual versus population decisions (Adapted from Atkins, 2007).

- Specifying Magnitude of Effect

In order for decisions to be objective, it is important for there to be an a priori discussion with stakeholders about the magnitude of effect that stakeholders believe represents a meaningful difference between treatment options. Researchers will be familiar with the basic tenet that statistically significant differences do not always represent clinically meaningful differences. Hence, researchers and stakeholders will need to have knowledge of the instruments that are used to measure differences and the accuracy, limitations, and properties of those instruments. Three key questions are recommended to use when eliciting from stakeholders the effect sizes that are important to them for making a decision or taking action:

- How do patients and other stakeholders define a meaningful difference between interventions?

- How do previous studies and reviews define a meaningful difference?

- Are patients and other stakeholders interested in superiority or noninferiority as it relates to decisionmaking?

- Challenges to Developing Study Questions and Initial Solutions

In developing CER study objectives and questions, there are some potential challenges that face researchers and stakeholders. The involvement of patients and other stakeholders in determining study objectives and questions is a relatively new paradigm, but one that is consistent with established principles of translational research. A key principle of translational research is that users need to be involved in research at the earliest stages for the research to be adopted. 16 In addition, most research is currently initiated by an investigator, and traditionally there have been few incentives (and some disincentives) to involving others in designing a new research study. Although the research paradigm is rapidly shifting, 17 there is little information about how to structure, process, and evaluate outcomes from initiatives that attempt to engage stakeholders in developing study questions and objectives with researchers. As different approaches are taken to involve stakeholders in the research process, researchers will learn how to optimize the process of stakeholder involvement and improve the applicability of research to the end-users.