Social Work Research Methods That Drive the Practice

Social workers advocate for the well-being of individuals, families and communities. But how do social workers know what interventions are needed to help an individual? How do they assess whether a treatment plan is working? What do social workers use to write evidence-based policy?

Social work involves research-informed practice and practice-informed research. At every level, social workers need to know objective facts about the populations they serve, the efficacy of their interventions and the likelihood that their policies will improve lives. A variety of social work research methods make that possible.

Data-Driven Work

Data is a collection of facts used for reference and analysis. In a field as broad as social work, data comes in many forms.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative

As with any research, social work research involves both quantitative and qualitative studies.

Quantitative Research

Answers to questions like these can help social workers know about the populations they serve — or hope to serve in the future.

- How many students currently receive reduced-price school lunches in the local school district?

- How many hours per week does a specific individual consume digital media?

- How frequently did community members access a specific medical service last year?

Quantitative data — facts that can be measured and expressed numerically — are crucial for social work.

Quantitative research has advantages for social scientists. Such research can be more generalizable to large populations, as it uses specific sampling methods and lends itself to large datasets. It can provide important descriptive statistics about a specific population. Furthermore, by operationalizing variables, it can help social workers easily compare similar datasets with one another.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative data — facts that cannot be measured or expressed in terms of mere numbers or counts — offer rich insights into individuals, groups and societies. It can be collected via interviews and observations.

- What attitudes do students have toward the reduced-price school lunch program?

- What strategies do individuals use to moderate their weekly digital media consumption?

- What factors made community members more or less likely to access a specific medical service last year?

Qualitative research can thereby provide a textured view of social contexts and systems that may not have been possible with quantitative methods. Plus, it may even suggest new lines of inquiry for social work research.

Mixed Methods Research

Combining quantitative and qualitative methods into a single study is known as mixed methods research. This form of research has gained popularity in the study of social sciences, according to a 2019 report in the academic journal Theory and Society. Since quantitative and qualitative methods answer different questions, merging them into a single study can balance the limitations of each and potentially produce more in-depth findings.

However, mixed methods research is not without its drawbacks. Combining research methods increases the complexity of a study and generally requires a higher level of expertise to collect, analyze and interpret the data. It also requires a greater level of effort, time and often money.

The Importance of Research Design

Data-driven practice plays an essential role in social work. Unlike philanthropists and altruistic volunteers, social workers are obligated to operate from a scientific knowledge base.

To know whether their programs are effective, social workers must conduct research to determine results, aggregate those results into comprehensible data, analyze and interpret their findings, and use evidence to justify next steps.

Employing the proper design ensures that any evidence obtained during research enables social workers to reliably answer their research questions.

Research Methods in Social Work

The various social work research methods have specific benefits and limitations determined by context. Common research methods include surveys, program evaluations, needs assessments, randomized controlled trials, descriptive studies and single-system designs.

Surveys involve a hypothesis and a series of questions in order to test that hypothesis. Social work researchers will send out a survey, receive responses, aggregate the results, analyze the data, and form conclusions based on trends.

Surveys are one of the most common research methods social workers use — and for good reason. They tend to be relatively simple and are usually affordable. However, surveys generally require large participant groups, and self-reports from survey respondents are not always reliable.

Program Evaluations

Social workers ally with all sorts of programs: after-school programs, government initiatives, nonprofit projects and private programs, for example.

Crucially, social workers must evaluate a program’s effectiveness in order to determine whether the program is meeting its goals and what improvements can be made to better serve the program’s target population.

Evidence-based programming helps everyone save money and time, and comparing programs with one another can help social workers make decisions about how to structure new initiatives. Evaluating programs becomes complicated, however, when programs have multiple goal metrics, some of which may be vague or difficult to assess (e.g., “we aim to promote the well-being of our community”).

Needs Assessments

Social workers use needs assessments to identify services and necessities that a population lacks access to.

Common social work populations that researchers may perform needs assessments on include:

- People in a specific income group

- Everyone in a specific geographic region

- A specific ethnic group

- People in a specific age group

In the field, a social worker may use a combination of methods (e.g., surveys and descriptive studies) to learn more about a specific population or program. Social workers look for gaps between the actual context and a population’s or individual’s “wants” or desires.

For example, a social worker could conduct a needs assessment with an individual with cancer trying to navigate the complex medical-industrial system. The social worker may ask the client questions about the number of hours they spend scheduling doctor’s appointments, commuting and managing their many medications. After learning more about the specific client needs, the social worker can identify opportunities for improvements in an updated care plan.

In policy and program development, social workers conduct needs assessments to determine where and how to effect change on a much larger scale. Integral to social work at all levels, needs assessments reveal crucial information about a population’s needs to researchers, policymakers and other stakeholders. Needs assessments may fall short, however, in revealing the root causes of those needs (e.g., structural racism).

Randomized Controlled Trials

Randomized controlled trials are studies in which a randomly selected group is subjected to a variable (e.g., a specific stimulus or treatment) and a control group is not. Social workers then measure and compare the results of the randomized group with the control group in order to glean insights about the effectiveness of a particular intervention or treatment.

Randomized controlled trials are easily reproducible and highly measurable. They’re useful when results are easily quantifiable. However, this method is less helpful when results are not easily quantifiable (i.e., when rich data such as narratives and on-the-ground observations are needed).

Descriptive Studies

Descriptive studies immerse the researcher in another context or culture to study specific participant practices or ways of living. Descriptive studies, including descriptive ethnographic studies, may overlap with and include other research methods:

- Informant interviews

- Census data

- Observation

By using descriptive studies, researchers may glean a richer, deeper understanding of a nuanced culture or group on-site. The main limitations of this research method are that it tends to be time-consuming and expensive.

Single-System Designs

Unlike most medical studies, which involve testing a drug or treatment on two groups — an experimental group that receives the drug/treatment and a control group that does not — single-system designs allow researchers to study just one group (e.g., an individual or family).

Single-system designs typically entail studying a single group over a long period of time and may involve assessing the group’s response to multiple variables.

For example, consider a study on how media consumption affects a person’s mood. One way to test a hypothesis that consuming media correlates with low mood would be to observe two groups: a control group (no media) and an experimental group (two hours of media per day). When employing a single-system design, however, researchers would observe a single participant as they watch two hours of media per day for one week and then four hours per day of media the next week.

These designs allow researchers to test multiple variables over a longer period of time. However, similar to descriptive studies, single-system designs can be fairly time-consuming and costly.

Learn More About Social Work Research Methods

Social workers have the opportunity to improve the social environment by advocating for the vulnerable — including children, older adults and people with disabilities — and facilitating and developing resources and programs.

Learn more about how you can earn your Master of Social Work online at Virginia Commonwealth University . The highest-ranking school of social work in Virginia, VCU has a wide range of courses online. That means students can earn their degrees with the flexibility of learning at home. Learn more about how you can take your career in social work further with VCU.

From M.S.W. to LCSW: Understanding Your Career Path as a Social Worker

How Palliative Care Social Workers Support Patients With Terminal Illnesses

How to Become a Social Worker in Health Care

Gov.uk, Mixed Methods Study

MVS Open Press, Foundations of Social Work Research

Open Social Work Education, Scientific Inquiry in Social Work

Open Social Work, Graduate Research Methods in Social Work: A Project-Based Approach

Routledge, Research for Social Workers: An Introduction to Methods

SAGE Publications, Research Methods for Social Work: A Problem-Based Approach

Theory and Society, Mixed Methods Research: What It Is and What It Could Be

READY TO GET STARTED WITH OUR ONLINE M.S.W. PROGRAM FORMAT?

Bachelor’s degree is required.

VCU Program Helper

This AI chatbot provides automated responses, which may not always be accurate. By continuing with this conversation, you agree that the contents of this chat session may be transcribed and retained. You also consent that this chat session and your interactions, including cookie usage, are subject to our privacy policy .

S371 Social Work Research - Jill Chonody: What is Quantitative Research?

- Choosing a Topic

- Choosing Search Terms

- What is Quantitative Research?

- Requesting Materials

Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences

This page is courtesy of University of Southern California: http://libguides.usc.edu/content.php?pid=83009&sid=615867

Quantitative methods emphasize objective measurements and the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data collected through polls, questionnaires, and surveys, or by manipulating pre-existing statistical data using computational techniques . Quantitative research focuses on gathering numerical data and generalizing it across groups of people or to explain a particular phenomenon.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Muijs, Daniel. Doing Quantitative Research in Education with SPSS . 2nd edition. London: SAGE Publications, 2010.

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

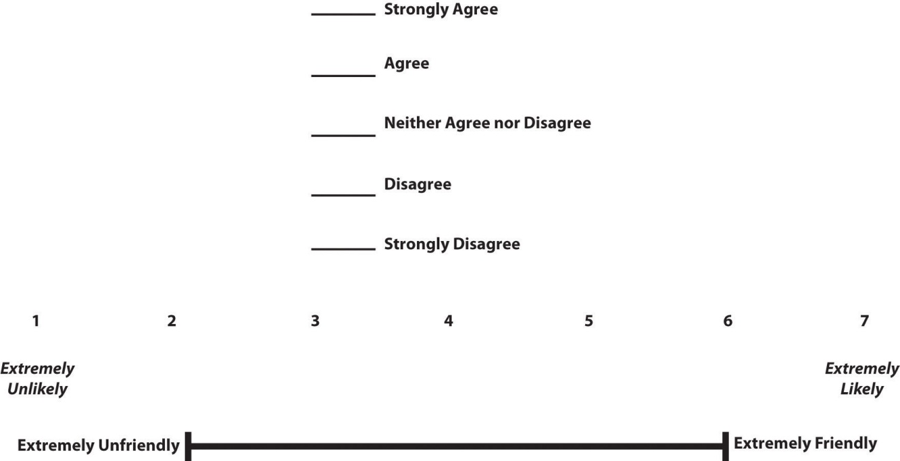

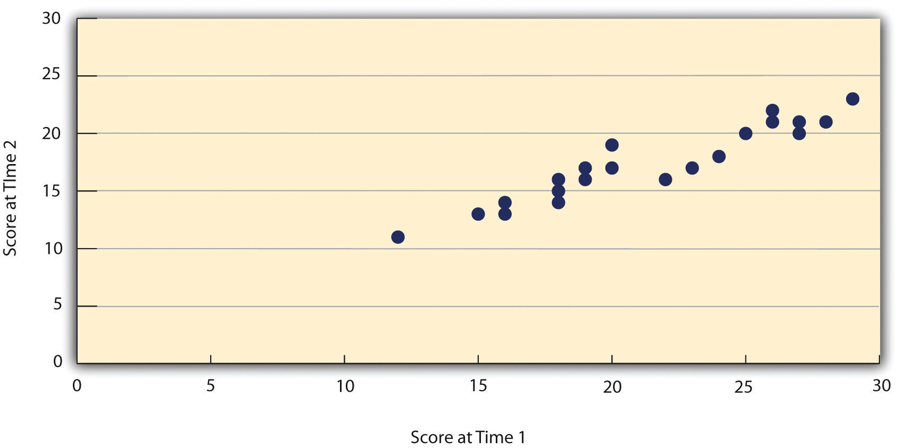

Your goal in conducting quantitative research study is to determine the relationship between one thing [an independent variable] and another [a dependent or outcome variable] within a population. Quantitative research designs are either descriptive [subjects usually measured once] or experimental [subjects measured before and after a treatment]. A descriptive study establishes only associations between variables; an experimental study establishes causality.

Quantitative research deals in numbers, logic, and an objective stance. Quantitative research focuses on numberic and unchanging data and detailed, convergent reasoning rather than divergent reasoning [i.e., the generation of a variety of ideas about a research problem in a spontaneous, free-flowing manner].

Its main characteristics are :

- The data is usually gathered using structured research instruments.

- The results are based on larger sample sizes that are representative of the population.

- The research study can usually be replicated or repeated, given its high reliability.

- Researcher has a clearly defined research question to which objective answers are sought.

- All aspects of the study are carefully designed before data is collected.

- Data are in the form of numbers and statistics, often arranged in tables, charts, figures, or other non-textual forms.

- Project can be used to generalize concepts more widely, predict future results, or investigate causal relationships.

- Researcher uses tools, such as questionnaires or computer software, to collect numerical data.

The overarching aim of a quantitative research study is to classify features, count them, and construct statistical models in an attempt to explain what is observed.

Things to keep in mind when reporting the results of a study using quantiative methods :

- Explain the data collected and their statistical treatment as well as all relevant results in relation to the research problem you are investigating. Interpretation of results is not appropriate in this section.

- Report unanticipated events that occurred during your data collection. Explain how the actual analysis differs from the planned analysis. Explain your handling of missing data and why any missing data does not undermine the validity of your analysis.

- Explain the techniques you used to "clean" your data set.

- Choose a minimally sufficient statistical procedure ; provide a rationale for its use and a reference for it. Specify any computer programs used.

- Describe the assumptions for each procedure and the steps you took to ensure that they were not violated.

- When using inferential statistics , provide the descriptive statistics, confidence intervals, and sample sizes for each variable as well as the value of the test statistic, its direction, the degrees of freedom, and the significance level [report the actual p value].

- Avoid inferring causality , particularly in nonrandomized designs or without further experimentation.

- Use tables to provide exact values ; use figures to convey global effects. Keep figures small in size; include graphic representations of confidence intervals whenever possible.

- Always tell the reader what to look for in tables and figures .

NOTE: When using pre-existing statistical data gathered and made available by anyone other than yourself [e.g., government agency], you still must report on the methods that were used to gather the data and describe any missing data that exists and, if there is any, provide a clear explanation why the missing datat does not undermine the validity of your final analysis.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Brians, Craig Leonard et al. Empirical Political Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods . 8th ed. Boston, MA: Longman, 2011; McNabb, David E. Research Methods in Public Administration and Nonprofit Management: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches . 2nd ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2008; Quantitative Research Methods . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Singh, Kultar. Quantitative Social Research Methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2007.

Basic Research Designs for Quantitative Studies

Before designing a quantitative research study, you must decide whether it will be descriptive or experimental because this will dictate how you gather, analyze, and interpret the results. A descriptive study is governed by the following rules: subjects are generally measured once; the intention is to only establish associations between variables; and, the study may include a sample population of hundreds or thousands of subjects to ensure that a valid estimate of a generalized relationship between variables has been obtained. An experimental design includes subjects measured before and after a particular treatment, the sample population may be very small and purposefully chosen, and it is intended to establish causality between variables. Introduction The introduction to a quantitative study is usually written in the present tense and from the third person point of view. It covers the following information:

- Identifies the research problem -- as with any academic study, you must state clearly and concisely the research problem being investigated.

- Reviews the literature -- review scholarship on the topic, synthesizing key themes and, if necessary, noting studies that have used similar methods of inquiry and analysis. Note where key gaps exist and how your study helps to fill these gaps or clarifies existing knowledge.

- Describes the theoretical framework -- provide an outline of the theory or hypothesis underpinning your study. If necessary, define unfamiliar or complex terms, concepts, or ideas and provide the appropriate background information to place the research problem in proper context [e.g., historical, cultural, economic, etc.].

Methodology The methods section of a quantitative study should describe how each objective of your study will be achieved. Be sure to provide enough detail to enable the reader can make an informed assessment of the methods being used to obtain results associated with the research problem. The methods section should be presented in the past tense.

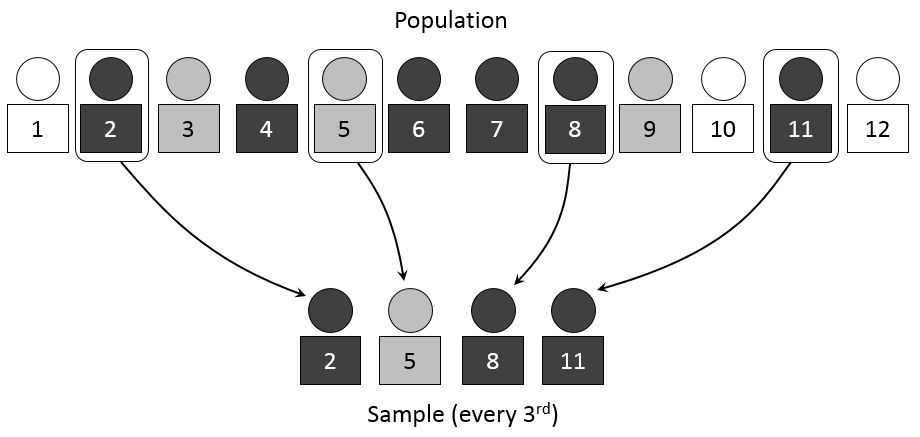

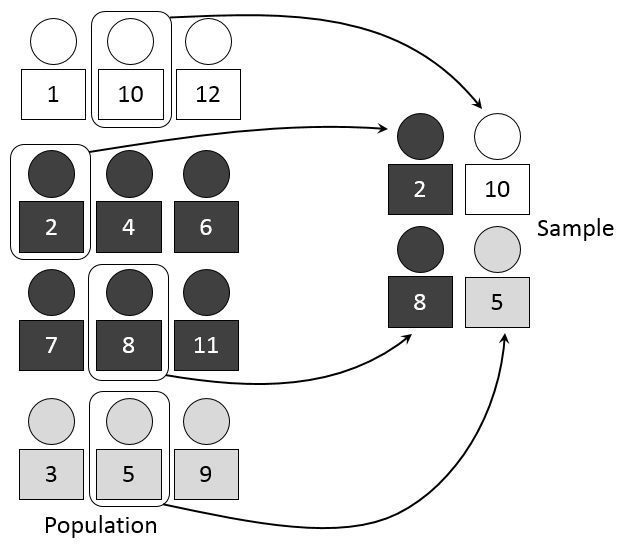

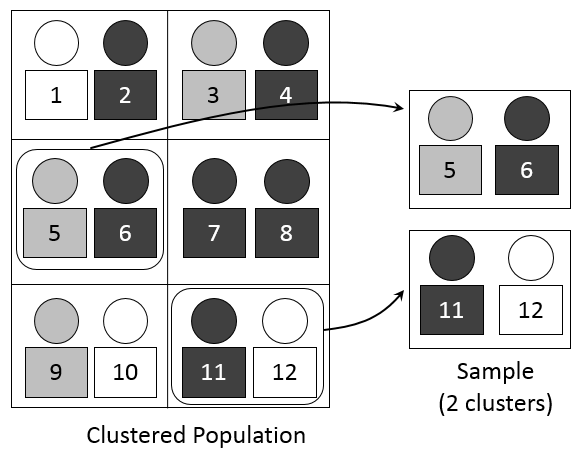

- Study population and sampling -- where did the data come from; how robust is it; note where gaps exist or what was excluded. Note the procedures used for their selection;

- Data collection – describe the tools and methods used to collect information and identify the variables being measured; describe the methods used to obtain the data; and, note if the data was pre-existing [i.e., government data] or you gathered it yourself. If you gathered it yourself, describe what type of instrument you used and why. Note that no data set is perfect--describe any limitations in methods of gathering data.

- Data analysis -- describe the procedures for processing and analyzing the data. If appropriate, describe the specific instruments of analysis used to study each research objective, including mathematical techniques and the type of computer software used to manipulate the data.

Results The finding of your study should be written objectively and in a succinct and precise format. In quantitative studies, it is common to use graphs, tables, charts, and other non-textual elements to help the reader understand the data. Make sure that non-textual elements do not stand in isolation from the text but are being used to supplement the overall description of the results and to help clarify key points being made. Further information about how to effectively present data using charts and graphs can be found here .

- Statistical analysis -- how did you analyze the data? What were the key findings from the data? The findings should be present in a logical, sequential order. Describe but do not interpret these trends or negative results; save that for the discussion section. The results should be presented in the past tense.

Discussion Discussions should be analytic, logical, and comprehensive. The discussion should meld together your findings in relation to those identified in the literature review, and placed within the context of the theoretical framework underpinning the study. The discussion should be presented in the present tense.

- Interpretation of results -- reiterate the research problem being investigated and compare and contrast the findings with the research questions underlying the study. Did they affirm predicted outcomes or did the data refute it?

- Description of trends, comparison of groups, or relationships among variables -- describe any trends that emerged from your analysis and explain all unanticipated and statistical insignificant findings.

- Discussion of implications – what is the meaning of your results? Highlight key findings based on the overall results and note findings that you believe are important. How have the results helped fill gaps in understanding the research problem?

- Limitations -- describe any limitations or unavoidable bias in your study and, if necessary, note why these limitations did not inhibit effective interpretation of the results.

Conclusion End your study by to summarizing the topic and provide a final comment and assessment of the study.

- Summary of findings – synthesize the answers to your research questions. Do not report any statistical data here; just provide a narrative summary of the key findings and describe what was learned that you did not know before conducting the study.

- Recommendations – if appropriate to the aim of the assignment, tie key findings with policy recommendations or actions to be taken in practice.

- Future research – note the need for future research linked to your study’s limitations or to any remaining gaps in the literature that were not addressed in your study.

Black, Thomas R. Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Research Design, Measurement and Statistics . London: Sage, 1999; Gay,L. R. and Peter Airasain. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications . 7th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merril Prentice Hall, 2003; Hector, Anestine. An Overview of Quantitative Research in Compostion and TESOL . Department of English, Indiana University of Pennsylvania; Hopkins, Will G. “Quantitative Research Design.” Sportscience 4, 1 (2000); A Strategy for Writing Up Research Results . The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Nenty, H. Johnson. "Writing a Quantitative Research Thesis." International Journal of Educational Science 1 (2009): 19-32; Ouyang, Ronghua (John). Basic Inquiry of Quantitative Research . Kennesaw State University.

- << Previous: Finding Quantitative Research

- Next: Databases >>

- Last Updated: Jul 11, 2023 1:03 PM

- URL: https://libguides.iun.edu/S371socialworkresearch

Graduate research methods in social work

(2 reviews)

Matt DeCarlo, La Salle University

Cory Cummings, Nazareth University

Kate Agnelli, Virginia Commonwealth University

Copyright Year: 2021

ISBN 13: 9781949373219

Publisher: Open Social Work Education

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Laura Montero, Full-time Lecturer and Course Lead, Metropolitan State University of Denver on 12/23/23

Graduate Research Methods in Social Work by DeCarlo, et al., is a comprehensive and well-structured guide that serves as an invaluable resource for graduate students delving into the intricate world of social work research. The book is divided... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

Graduate Research Methods in Social Work by DeCarlo, et al., is a comprehensive and well-structured guide that serves as an invaluable resource for graduate students delving into the intricate world of social work research. The book is divided into five distinct parts, each carefully curated to provide a step-by-step approach to mastering research methods in the field. Topics covered include an intro to basic research concepts, conceptualization, quantitative & qualitative approaches, as well as research in practice. At 800+ pages, however, the text could be received by students as a bit overwhelming.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

Content appears consistent and reliable when compared to similar textbooks in this topic.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The book's well-structured content begins with fundamental concepts, such as the scientific method and evidence-based practice, guiding readers through the initiation of research projects with attention to ethical considerations. It seamlessly transitions to detailed explorations of both quantitative and qualitative methods, covering topics like sampling, measurement, survey design, and various qualitative data collection approaches. Throughout, the authors emphasize ethical responsibilities, cultural respectfulness, and critical thinking. These are crucial concepts we cover in social work and I was pleased to see these being integrated throughout.

Clarity rating: 5

The level of the language used is appropriate for graduate-level study.

Consistency rating: 5

Book appears to be consistent in the tone and terminology used.

Modularity rating: 4

The images and videos included, help to break up large text blocks.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Topics covered are well-organized and comprehensive. I appreciate the thorough preamble the authors include to situate the role of the social worker within a research context.

Interface rating: 4

When downloaded as a pdf, the book does not begin until page 30+ so it may be a bit difficult to scroll so long for students in order to access the content for which they are searching. Also, making the Table of Contents clickable, would help in navigating this very long textbook.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I did not find any grammatical errors or typos in the pages reviewed.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

I appreciate the efforts made to integrate diverse perspectives, voices, and images into the text. The discussion around ethics and cultural considerations in research was nuanced and comprehensive as well.

Overall, the content of the book aligns with established principles of social work research, providing accurate and up-to-date information in a format that is accessible to graduate students and educators in the field.

Reviewed by Elisa Maroney, Professor, Western Oregon University on 1/2/22

With well over 800 pages, this text is beyond comprehensive! read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

With well over 800 pages, this text is beyond comprehensive!

I perused the entire text, but my focus was on "Part 4: Using qualitative methods." This section seems accurate.

As mentioned above, my primary focus was on the qualitative methods section. This section is relevant to the students I teach in interpreting studies (not a social sciences discipline).

This book is well-written and clear.

Navigating this text is easy, because the formatting is consistent

Modularity rating: 5

My favorite part of this text is that I can be easily customized, so that I can use the sections on qualitative methods.

The text is well-organized and easy to find and link to related sections in the book.

Interface rating: 5

There are no distracting or confusing features. The book is long; being able to customize makes it easier to navigate.

I did not notice grammatical errors.

The authors offer resources for Afrocentricity for social work practice (among others, including those related to Feminist and Queer methodologies). These are relevant to the field of interpreting studies.

I look forward to adopting this text in my qualitative methods course for graduate students in interpreting studies.

Table of Contents

- 1. Science and social work

- 2. Starting your research project

- 3. Searching the literature

- 4. Critical information literacy

- 5. Writing your literature review

- 6. Research ethics

- 7. Theory and paradigm

- 8. Reasoning and causality

- 9. Writing your research question

- 10. Quantitative sampling

- 11. Quantitative measurement

- 12. Survey design

- 13. Experimental design

- 14. Univariate analysis

- 15. Bivariate analysis

- 16. Reporting quantitative results

- 17. Qualitative data and sampling

- 18. Qualitative data collection

- 19. A survey of approaches to qualitative data analysis

- 20. Quality in qualitative studies: Rigor in research design

- 21. Qualitative research dissemination

- 22. A survey of qualitative designs

- 23. Program evaluation

- 24. Sharing and consuming research

Ancillary Material

About the book.

We designed our book to help graduate social work students through every step of the research process, from conceptualization to dissemination. Our textbook centers cultural humility, information literacy, pragmatism, and an equal emphasis on quantitative and qualitative methods. It includes extensive content on literature reviews, cultural bias and respectfulness, and qualitative methods, in contrast to traditionally used commercial textbooks in social work research.

Our author team spans across academic, public, and nonprofit social work research. We love research, and we endeavored through our book to make research more engaging, less painful, and easier to understand. Our textbook exercises direct students to apply content as they are reading the book to an original research project. By breaking it down step-by-step, writing in approachable language, as well as using stories from our life, practice, and research experience, our textbook helps professors overcome students’ research methods anxiety and antipathy.

If you decide to adopt our resource, we ask that you complete this short Adopter’s Survey that helps us keep track of our community impact. You can also contact [email protected] for a student workbook, homework assignments, slideshows, a draft bank of quiz questions, and a course calendar.

About the Contributors

Matt DeCarlo , PhD, MSW is an assistant professor in the Department of Social Work at La Salle University. He is the co-founder of Open Social Work (formerly Open Social Work Education), a collaborative project focusing on open education, open science, and open access in social work and higher education. His first open textbook, Scientific Inquiry in Social Work, was the first developed for social work education, and is now in use in over 60 campuses, mostly in the United States. He is a former OER Research Fellow with the OpenEd Group. Prior to his work in OER, Dr. DeCarlo received his PhD from Virginia Commonwealth University and has published on disability policy.

Cory Cummings , Ph.D., LCSW is an assistant professor in the Department of Social Work at Nazareth University. He has practice experience in community mental health, including clinical practice and administration. In addition, Dr. Cummings has volunteered at safety net mental health services agencies and provided support services for individuals and families affected by HIV. In his current position, Dr. Cummings teaches in the BSW program and MSW programs; specifically in the Clinical Practice with Children and Families concentration. Courses that he teaches include research, social work practice, and clinical field seminar. His scholarship focuses on promoting health equity for individuals experiencing symptoms of severe mental illness and improving opportunities to increase quality of life. Dr. Cummings received his PhD from Virginia Commonwealth University.

Kate Agnelli , MSW, is an adjunct professor at VCU’s School of Social Work, teaching masters-level classes on research methods, public policy, and social justice. She also works as a senior legislative analyst with the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), a policy research organization reporting to the Virginia General Assembly. Before working for JLARC, Ms. Agnelli worked for several years in government and nonprofit research and program evaluation. In addition, she has several publications in peer-reviewed journals, has presented at national social work conferences, and has served as a reviewer for Social Work Education. She received her MSW from Virginia Commonwealth University.

Contribute to this Page

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

The Handbook of Social Work Research Methods

- Bruce Thyer - Florida State University, USA

- Description

Click on the Supplements tab above for further details on the different versions of SPSS programs. The canonical Handbook is completely updated with more student-friendly features

The Handbook of Social Work Research Methods is a cutting-edge volume that covers all the major topics that are relevant for Social Work Research methods. Edited by Bruce Thyer and containing contributions by leading authorities, this Handbook covers both qualitative and quantitative approaches as well as a section that delves into more general issues such as evidence based practice, ethics, gender, ethnicity, International Issues, integrating both approaches, and applying for grants.

New to this Edition

- More content on qualitative methods and mixed methods

- More coverage of evidence-based practice

- More support to help students effectively use the Internet

- A companion Web site at www.sagepub.com/thyerhdbk2e containing a test bank and PowerPoint slides for instructors and relevant SAGE journal articles for students.

This Handbook serves as a primary text in the methods courses in MSW programs and doctoral level programs. It can also be used as a reference and research design tool for anyone doing scholarly research in social work or human services.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

This book was not a good fit for my course. I adopted Research Methods in Practice (Remler and Van Ryzin) instead.

This textbook is exactly what I was looking for to update my course! It is comprehensive, yet easy to digest for an introduction course.

The topics were too dispersed - it could be a resource book but not my primary book.

I like Thyer's book, but I will use it as a recommended text, rather than a main text my research methods course. It can be a great resource for the doctoral students. For my needs, the text I currently use, Engel and Schutt, I think does a better job in covering Social Work research methodology. It has good structure and a continuity of ideas and themes.

Not as well written or as thorough as Essential Research Methods for Social Workers (Rubin)

- An outstanding cast of contributors

- Offers students the depth of topic that is difficult to achieve with a single authored text.

- More coverage of Evidence Based Practice

Sample Materials & Chapters

Chapter 1 - Introductory Principles of SocialWork Research

Chapter 3 - Probability and Sampling

For instructors

Select a purchasing option.

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

- Help & Terms of Use

Quantitative Research Methods for Social Work: Making Social Work Count

- School for Policy Studies

Research output : Book/Report › Authored book

- Quantitative Research Methods

- Social Work

- Persistent link

Fingerprint

- Social Work Social Sciences 100%

- Quantitative Research Method Social Sciences 100%

- Books Social Sciences 40%

- Research Social Sciences 40%

- Social Scientists Social Sciences 40%

- Understanding Social Sciences 40%

- UK Social Sciences 40%

- Skills Social Sciences 40%

T1 - Quantitative Research Methods for Social Work

T2 - Making Social Work Count

AU - Teater, Barbra

AU - Devaney, John

AU - Forrester, Donald

AU - Scourfield, Jonathan

AU - Carpenter, John

PY - 2017/1/1

Y1 - 2017/1/1

N2 - Social work knowledge and understanding draws heavily on research, and the ability to critically analyse research findings is a core skill for social workers. However, while many social work students are confident in reading qualitative data, a lack of understanding in basic statistical concepts means that this same confidence does not always apply to quantitative data.The book arose from a curriculum development project funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), in conjunction with the Higher Education Funding Council for England, the British Academy and the Nuffield Foundation. This was part of a wider initiative to increase the numbers of quantitative social scientists in the UK in order to address an identified skills gap. This gap related to both the conduct of quantitative research and the literacy of social scientists in being able to read and interpret statistical information. The book is a comprehensive resource for students and educators. It is packed with activities and examples from social work covering the basic concepts of quantitative research methods – including reliability, validity, probability, variables and hypothesis testing – and explores key areas of data collection, analysis and evaluation, providing a detailed examination of their application to social work practice.

AB - Social work knowledge and understanding draws heavily on research, and the ability to critically analyse research findings is a core skill for social workers. However, while many social work students are confident in reading qualitative data, a lack of understanding in basic statistical concepts means that this same confidence does not always apply to quantitative data.The book arose from a curriculum development project funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), in conjunction with the Higher Education Funding Council for England, the British Academy and the Nuffield Foundation. This was part of a wider initiative to increase the numbers of quantitative social scientists in the UK in order to address an identified skills gap. This gap related to both the conduct of quantitative research and the literacy of social scientists in being able to read and interpret statistical information. The book is a comprehensive resource for students and educators. It is packed with activities and examples from social work covering the basic concepts of quantitative research methods – including reliability, validity, probability, variables and hypothesis testing – and explores key areas of data collection, analysis and evaluation, providing a detailed examination of their application to social work practice.

KW - Quantitative Research Methods

KW - Social Work

M3 - Authored book

SN - 978-1-137-40026-0

BT - Quantitative Research Methods for Social Work

PB - Palgrave Macmillan

CY - London

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About The British Journal of Social Work

- About the British Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- Introduction

- Quantitative research in social work

- Limitations

- Acknowledgements

- < Previous

Nature and Extent of Quantitative Research in Social Work Journals: A Systematic Review from 2016 to 2020

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Sebastian Kurten, Nausikaä Brimmel, Kathrin Klein, Katharina Hutter, Nature and Extent of Quantitative Research in Social Work Journals: A Systematic Review from 2016 to 2020, The British Journal of Social Work , Volume 52, Issue 4, June 2022, Pages 2008–2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab171

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This study reviews 1,406 research articles published between 2016 and 2020 in the European Journal of Social Work (EJSW), the British Journal of Social Work (BJSW) and Research on Social Work Practice (RSWP). It assesses the proportion and complexity of quantitative research designs amongst published articles and investigates differences between the journals. Furthermore, the review investigates the complexity of the statistical methods employed and identifies the most frequently addressed topics. From the 1,406 articles, 504 (35.8 percent) used a qualitative methodology, 389 (27.7 percent) used a quantitative methodology, 85 (6 percent) used the mixed methods (6 percent), 253 (18 percent) articles were theoretical in nature, 148 (10.5 percent) conducted reviews and 27 (1.9 percent) gave project overviews. The proportion of quantitative research articles was higher in RSWP (55.4 percent) than in the EJSW (14.1 percent) and the BJSW (20.5 percent). The topic analysis could identify at least forty different topics addressed by the articles. Although the proportion of quantitative research is rather small in social work research, the review could not find evidence that it is of low sophistication. Finally, this study concludes that future research would benefit from making explicit why a certain methodology was chosen.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-263X

- Print ISSN 0045-3102

- Copyright © 2024 British Association of Social Workers

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Social Work Research Methods

Introduction.

- History of Social Work Research Methods

- Feasibility Issues Influencing the Research Process

- Measurement Methods

- Existing Scales

- Group Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Evaluating Outcome

- Single-System Designs for Evaluating Outcome

- Program Evaluation

- Surveys and Sampling

- Introductory Statistics Texts

- Advanced Aspects of Inferential Statistics

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Qualitative Data Analysis

- Historical Research Methods

- Meta-Analysis and Systematic Reviews

- Research Ethics

- Culturally Competent Research Methods

- Teaching Social Work Research Methods

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Community-Based Participatory Research

- Economic Evaluation

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice: Finding Evidence

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice: Issues, Controversies, and Debates

- Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs

- Impact of Emerging Technology in Social Work Practice

- Implementation Science and Practice

- Interviewing

- Measurement, Scales, and Indices

- Meta-analysis

- Occupational Social Work

- Postmodernism and Social Work

- Qualitative Research

- Research, Best Practices, and Evidence-based Group Work

- Social Intervention Research

- Social Work Profession

- Systematic Review Methods

- Technology for Social Work Interventions

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Child Welfare Effectiveness

- Rare and Orphan Diseases and Social Work Practice

- Unaccompanied Immigrant and Refugee Children

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Social Work Research Methods by Allen Rubin LAST REVIEWED: 14 December 2009 LAST MODIFIED: 14 December 2009 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195389678-0008

Social work research means conducting an investigation in accordance with the scientific method. The aim of social work research is to build the social work knowledge base in order to solve practical problems in social work practice or social policy. Investigating phenomena in accordance with the scientific method requires maximal adherence to empirical principles, such as basing conclusions on observations that have been gathered in a systematic, comprehensive, and objective fashion. The resources in this entry discuss how to do that as well as how to utilize and teach research methods in social work. Other professions and disciplines commonly produce applied research that can guide social policy or social work practice. Yet no commonly accepted distinction exists at this time between social work research methods and research methods in allied fields relevant to social work. Consequently useful references pertaining to research methods in allied fields that can be applied to social work research are included in this entry.

This section includes basic textbooks that are used in courses on social work research methods. Considerable variation exists between textbooks on the broad topic of social work research methods. Some are comprehensive and delve into topics deeply and at a more advanced level than others. That variation is due in part to the different needs of instructors at the undergraduate and graduate levels of social work education. Most instructors at the undergraduate level prefer shorter and relatively simplified texts; however, some instructors teaching introductory master’s courses on research prefer such texts too. The texts in this section that might best fit their preferences are by Yegidis and Weinbach 2009 and Rubin and Babbie 2007 . The remaining books might fit the needs of instructors at both levels who prefer a more comprehensive and deeper coverage of research methods. Among them Rubin and Babbie 2008 is perhaps the most extensive and is often used at the doctoral level as well as the master’s and undergraduate levels. Also extensive are Drake and Jonson-Reid 2007 , Grinnell and Unrau 2007 , Kreuger and Neuman 2006 , and Thyer 2001 . What distinguishes Drake and Jonson-Reid 2007 is its heavy inclusion of statistical and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) content integrated with each chapter. Grinnell and Unrau 2007 and Thyer 2001 are unique in that they are edited volumes with different authors for each chapter. Kreuger and Neuman 2006 takes Neuman’s social sciences research text and adapts it to social work. The Practitioner’s Guide to Using Research for Evidence-based Practice ( Rubin 2007 ) emphasizes the critical appraisal of research, covering basic research methods content in a relatively simplified format for instructors who want to teach research methods as part of the evidence-based practice process instead of with the aim of teaching students how to produce research.

Drake, Brett, and Melissa Jonson-Reid. 2007. Social work research methods: From conceptualization to dissemination . Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

This introductory text is distinguished by its use of many evidence-based practice examples and its heavy coverage of statistical and computer analysis of data.

Grinnell, Richard M., and Yvonne A. Unrau, eds. 2007. Social work research and evaluation: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . 8th ed. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Contains chapters written by different authors, each focusing on a comprehensive range of social work research topics.

Kreuger, Larry W., and W. Lawrence Neuman. 2006. Social work research methods: Qualitative and quantitative applications . Boston: Pearson, Allyn, and Bacon.

An adaptation to social work of Neuman's social sciences research methods text. Its framework emphasizes comparing quantitative and qualitative approaches. Despite its title, quantitative methods receive more attention than qualitative methods, although it does contain considerable qualitative content.

Rubin, Allen. 2007. Practitioner’s guide to using research for evidence-based practice . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

This text focuses on understanding quantitative and qualitative research methods and designs for the purpose of appraising research as part of the evidence-based practice process. It also includes chapters on instruments for assessment and monitoring practice outcomes. It can be used at the graduate or undergraduate level.

Rubin, Allen, and Earl R. Babbie. 2007. Essential research methods for social work . Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks Cole.

This is a shorter and less advanced version of Rubin and Babbie 2008 . It can be used for research methods courses at the undergraduate or master's levels of social work education.

Rubin, Allen, and Earl R. Babbie. Research Methods for Social Work . 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks Cole, 2008.

This comprehensive text focuses on producing quantitative and qualitative research as well as utilizing such research as part of the evidence-based practice process. It is widely used for teaching research methods courses at the undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral levels of social work education.

Thyer, Bruce A., ed. 2001 The handbook of social work research methods . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

This comprehensive compendium includes twenty-nine chapters written by esteemed leaders in social work research. It covers quantitative and qualitative methods as well as general issues.

Yegidis, Bonnie L., and Robert W. Weinbach. 2009. Research methods for social workers . 6th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

This introductory paperback text covers a broad range of social work research methods and does so in a briefer fashion than most lengthier, hardcover introductory research methods texts.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Social Work »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Adolescent Depression

- Adolescent Pregnancy

- Adolescents

- Adoption Home Study Assessments

- Adult Protective Services in the United States

- African Americans

- Aging out of foster care

- Aging, Physical Health and

- Alcohol and Drug Abuse Problems

- Alcohol and Drug Problems, Prevention of Adolescent and Yo...

- Alcohol Problems: Practice Interventions

- Alcohol Use Disorder

- Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias

- Anti-Oppressive Practice

- Asian Americans

- Asian-American Youth

- Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Baccalaureate Social Workers

- Behavioral Health

- Behavioral Social Work Practice

- Bereavement Practice

- Bisexuality

- Brief Therapies in Social Work: Task-Centered Model and So...

- Bullying and Social Work Intervention

- Canadian Social Welfare, History of

- Case Management in Mental Health in the United States

- Central American Migration to the United States

- Child Maltreatment Prevention

- Child Neglect and Emotional Maltreatment

- Child Poverty

- Child Sexual Abuse

- Child Welfare

- Child Welfare and Child Protection in Europe, History of

- Child Welfare and Parents with Intellectual and/or Develop...

- Child Welfare, Immigration and

- Child Welfare Practice with LGBTQ Youth and Families

- Children of Incarcerated Parents

- Christianity and Social Work

- Chronic Illness

- Clinical Social Work Practice with Adult Lesbians

- Clinical Social Work Practice with Males

- Cognitive Behavior Therapies with Diverse and Stressed Pop...

- Cognitive Processing Therapy

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

- Community Development

- Community Policing

- Community-Needs Assessment

- Comparative Social Work

- Computational Social Welfare: Applying Data Science in Soc...

- Conflict Resolution

- Council on Social Work Education

- Counseling Female Offenders

- Criminal Justice

- Crisis Interventions

- Cultural Competence and Ethnic Sensitive Practice

- Culture, Ethnicity, Substance Use, and Substance Use Disor...

- Dementia Care

- Dementia Care, Ethical Aspects of

- Depression and Cancer

- Development and Infancy (Birth to Age Three)

- Differential Response in Child Welfare

- Digital Storytelling for Social Work Interventions

- Direct Practice in Social Work

- Disabilities

- Disability and Disability Culture

- Domestic Violence Among Immigrants

- Early Pregnancy and Parenthood Among Child Welfare–Involve...

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Framework

- Elder Mistreatment

- End-of-Life Decisions

- Epigenetics for Social Workers

- Ethical Issues in Social Work and Technology

- Ethics and Values in Social Work

- European Institutions and Social Work

- European Union, Justice and Home Affairs in the

- Evidence-based Social Work Practice: Issues, Controversies...

- Families with Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual Parents

- Family Caregiving

- Family Group Conferencing

- Family Policy

- Family Services

- Family Therapy

- Family Violence

- Fathering Among Families Served By Child Welfare

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

- Field Education

- Financial Literacy and Social Work

- Financing Health-Care Delivery in the United States

- Forensic Social Work

- Foster Care

- Foster care and siblings

- Gender, Violence, and Trauma in Immigration Detention in t...

- Generalist Practice and Advanced Generalist Practice

- Grounded Theory

- Group Work across Populations, Challenges, and Settings

- Group Work, Research, Best Practices, and Evidence-based

- Harm Reduction

- Health Care Reform

- Health Disparities

- Health Social Work

- History of Social Work and Social Welfare, 1900–1950

- History of Social Work and Social Welfare, 1950-1980

- History of Social Work and Social Welfare, pre-1900

- History of Social Work from 1980-2014

- History of Social Work in China

- History of Social Work in Northern Ireland

- History of Social Work in the Republic of Ireland

- History of Social Work in the United Kingdom

- HIV/AIDS and Children

- HIV/AIDS Prevention with Adolescents

- Homelessness

- Homelessness: Ending Homelessness as a Grand Challenge

- Homelessness Outside the United States

- Human Needs

- Human Trafficking, Victims of

- Immigrant Integration in the United States

- Immigrant Policy in the United States

- Immigrants and Refugees

- Immigrants and Refugees: Evidence-based Social Work Practi...

- Immigration and Health Disparities

- Immigration and Intimate Partner Violence

- Immigration and Poverty

- Immigration and Spirituality

- Immigration and Substance Use

- Immigration and Trauma

- Impaired Professionals

- Indigenous Peoples

- Individual Placement and Support (IPS) Supported Employmen...

- In-home Child Welfare Services

- Intergenerational Transmission of Maltreatment

- International Human Trafficking

- International Social Welfare

- International Social Work

- International Social Work and Education

- International Social Work and Social Welfare in Southern A...

- Internet and Video Game Addiction

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy

- Intervention with Traumatized Populations

- Intimate-Partner Violence

- Juvenile Justice

- Kinship Care

- Korean Americans

- Latinos and Latinas

- Law, Social Work and the

- LGBTQ Populations and Social Work

- Mainland European Social Work, History of

- Major Depressive Disorder

- Management and Administration in Social Work

- Maternal Mental Health

- Medical Illness

- Men: Health and Mental Health Care

- Mental Health

- Mental Health Diagnosis and the Addictive Substance Disord...

- Mental Health Needs of Older People, Assessing the

- Mental Health Services from 1990 to 2023

- Mental Illness: Children

- Mental Illness: Elders

- Microskills

- Middle East and North Africa, International Social Work an...

- Military Social Work

- Mixed Methods Research

- Moral distress and injury in social work

- Motivational Interviewing

- Multiculturalism

- Native Americans

- Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders

- Neighborhood Social Cohesion

- Neuroscience and Social Work

- Nicotine Dependence

- Organizational Development and Change

- Pain Management

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care: Evolution and Scope of Practice

- Pandemics and Social Work

- Parent Training

- Personalization

- Person-in-Environment

- Philosophy of Science and Social Work

- Physical Disabilities

- Podcasts and Social Work

- Police Social Work

- Political Social Work in the United States

- Positive Youth Development

- Postsecondary Education Experiences and Attainment Among Y...

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Practice Interventions and Aging

- Practice Interventions with Adolescents

- Practice Research

- Primary Prevention in the 21st Century

- Productive Engagement of Older Adults

- Profession, Social Work

- Program Development and Grant Writing

- Promoting Smart Decarceration as a Grand Challenge

- Psychiatric Rehabilitation

- Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic Theory

- Psychoeducation

- Psychometrics

- Psychopathology and Social Work Practice

- Psychopharmacology and Social Work Practice

- Psychosocial Framework

- Psychosocial Intervention with Women

- Psychotherapy and Social Work

- Race and Racism

- Readmission Policies in Europe

- Redefining Police Interactions with People Experiencing Me...

- Rehabilitation

- Religiously Affiliated Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Restorative Justice

- Risk Assessment in Child Protection Services

- Risk Management in Social Work

- Rural Social Work in China

- Rural Social Work Practice

- School Social Work

- School Violence

- School-Based Delinquency Prevention

- Services and Programs for Pregnant and Parenting Youth

- Severe and Persistent Mental Illness: Adults

- Sexual and Gender Minority Immigrants, Refugees, and Asylu...

- Sexual Assault

- Single-System Research Designs

- Social and Economic Impact of US Immigration Policies on U...

- Social Development

- Social Insurance and Social Justice

- Social Justice and Social Work

- Social Movements

- Social Planning

- Social Policy

- Social Policy in Denmark

- Social Security in the United States (OASDHI)

- Social Work and Islam

- Social Work and Social Welfare in East, West, and Central ...

- Social Work and Social Welfare in Europe

- Social Work Education and Research

- Social Work Leadership

- Social Work Luminaries: Luminaries Contributing to the Cla...

- Social Work Luminaries: Luminaries contributing to the fou...

- Social Work Luminaries: Luminaries Who Contributed to Soci...

- Social Work Regulation

- Social Work Research Methods

- Social Work with Interpreters

- Solution-Focused Therapy

- Strategic Planning

- Strengths Perspective

- Strengths-Based Models in Social Work

- Supplemental Security Income

- Survey Research

- Sustainability: Creating Social Responses to a Changing En...

- Syrian Refugees in Turkey

- Task-Centered Practice

- Technology Adoption in Social Work Education

- Technology, Human Relationships, and Human Interaction

- Technology in Social Work

- Terminal Illness

- The Impact of Systemic Racism on Latinxs’ Experiences with...

- Transdisciplinary Science

- Translational Science and Social Work

- Transnational Perspectives in Social Work

- Transtheoretical Model of Change

- Trauma-Informed Care

- Triangulation

- Tribal child welfare practice in the United States

- United States, History of Social Welfare in the

- Universal Basic Income

- Veteran Services

- Vicarious Trauma and Resilience in Social Work Practice wi...

- Vicarious Trauma Redefining PTSD

- Victim Services

- Virtual Reality and Social Work

- Welfare State Reform in France

- Welfare State Theory

- Women and Macro Social Work Practice

- Women's Health Care

- Work and Family in the German Welfare State

- Workforce Development of Social Workers Pre- and Post-Empl...

- Working with Non-Voluntary and Mandated Clients

- Young and Adolescent Lesbians

- Youth at Risk

- Youth Services

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

19 11. Quantitative measurement

Chapter outline.

- Conceptual definitions (17 minute read)

- Operational definitions (36 minute read)

- Measurement quality (21 minute read)

- Ethical and social justice considerations (15 minute read)

Content warning: examples in this chapter contain references to ethnocentrism, toxic masculinity, racism in science, drug use, mental health and depression, psychiatric inpatient care, poverty and basic needs insecurity, pregnancy, and racism and sexism in the workplace and higher education.

11.1 Conceptual definitions

Learning objectives.

Learners will be able to…

- Define measurement and conceptualization

- Apply Kaplan’s three categories to determine the complexity of measuring a given variable

- Identify the role previous research and theory play in defining concepts

- Distinguish between unidimensional and multidimensional concepts

- Critically apply reification to how you conceptualize the key variables in your research project

In social science, when we use the term measurement , we mean the process by which we describe and ascribe meaning to the key facts, concepts, or other phenomena that we are investigating. At its core, measurement is about defining one’s terms in as clear and precise a way as possible. Of course, measurement in social science isn’t quite as simple as using a measuring cup or spoon, but there are some basic tenets on which most social scientists agree when it comes to measurement. We’ll explore those, as well as some of the ways that measurement might vary depending on your unique approach to the study of your topic.

An important point here is that measurement does not require any particular instruments or procedures. What it does require is a systematic procedure for assigning scores, meanings, and descriptions to individuals or objects so that those scores represent the characteristic of interest. You can measure phenomena in many different ways, but you must be sure that how you choose to measure gives you information and data that lets you answer your research question. If you’re looking for information about a person’s income, but your main points of measurement have to do with the money they have in the bank, you’re not really going to find the information you’re looking for!

The question of what social scientists measure can be answered by asking yourself what social scientists study. Think about the topics you’ve learned about in other social work classes you’ve taken or the topics you’ve considered investigating yourself. Let’s consider Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner’s study (2011) [1] of first graders’ mental health. In order to conduct that study, Milkie and Warner needed to have some idea about how they were going to measure mental health. What does mental health mean, exactly? And how do we know when we’re observing someone whose mental health is good and when we see someone whose mental health is compromised? Understanding how measurement works in research methods helps us answer these sorts of questions.

As you might have guessed, social scientists will measure just about anything that they have an interest in investigating. For example, those who are interested in learning something about the correlation between social class and levels of happiness must develop some way to measure both social class and happiness. Those who wish to understand how well immigrants cope in their new locations must measure immigrant status and coping. Those who wish to understand how a person’s gender shapes their workplace experiences must measure gender and workplace experiences (and get more specific about which experiences are under examination). You get the idea. Social scientists can and do measure just about anything you can imagine observing or wanting to study. Of course, some things are easier to observe or measure than others.

Observing your variables

In 1964, philosopher Abraham Kaplan (1964) [2] wrote The Conduct of Inquiry, which has since become a classic work in research methodology (Babbie, 2010). [3] In his text, Kaplan describes different categories of things that behavioral scientists observe. One of those categories, which Kaplan called “observational terms,” is probably the simplest to measure in social science. Observational terms are the sorts of things that we can see with the naked eye simply by looking at them. Kaplan roughly defines them as conditions that are easy to identify and verify through direct observation. If, for example, we wanted to know how the conditions of playgrounds differ across different neighborhoods, we could directly observe the variety, amount, and condition of equipment at various playgrounds.

Indirect observables , on the other hand, are less straightforward to assess. In Kaplan’s framework, they are conditions that are subtle and complex that we must use existing knowledge and intuition to define. If we conducted a study for which we wished to know a person’s income, we’d probably have to ask them their income, perhaps in an interview or a survey. Thus, we have observed income, even if it has only been observed indirectly. Birthplace might be another indirect observable. We can ask study participants where they were born, but chances are good we won’t have directly observed any of those people being born in the locations they report.

Sometimes the measures that we are interested in are more complex and more abstract than observational terms or indirect observables. Think about some of the concepts you’ve learned about in other social work classes—for example, ethnocentrism. What is ethnocentrism? Well, from completing an introduction to social work class you might know that it has something to do with the way a person judges another’s culture. But how would you measure it? Here’s another construct: bureaucracy. We know this term has something to do with organizations and how they operate but measuring such a construct is trickier than measuring something like a person’s income. The theoretical concepts of ethnocentrism and bureaucracy represent ideas whose meanings we have come to agree on. Though we may not be able to observe these abstractions directly, we can observe their components.

Kaplan referred to these more abstract things that behavioral scientists measure as constructs. Constructs are “not observational either directly or indirectly” (Kaplan, 1964, p. 55), [4] but they can be defined based on observables. For example, the construct of bureaucracy could be measured by counting the number of supervisors that need to approve routine spending by public administrators. The greater the number of administrators that must sign off on routine matters, the greater the degree of bureaucracy. Similarly, we might be able to ask a person the degree to which they trust people from different cultures around the world and then assess the ethnocentrism inherent in their answers. We can measure constructs like bureaucracy and ethnocentrism by defining them in terms of what we can observe. [5]

The idea of coming up with your own measurement tool might sound pretty intimidating at this point. The good news is that if you find something in the literature that works for you, you can use it (with proper attribution, of course). If there are only pieces of it that you like, you can reuse those pieces (with proper attribution and describing/justifying any changes). You don’t always have to start from scratch!

Look at the variables in your research question.

- Classify them as direct observables, indirect observables, or constructs.

- Do you think measuring them will be easy or hard?

- What are your first thoughts about how to measure each variable? No wrong answers here, just write down a thought about each variable.

Measurement starts with conceptualization

In order to measure the concepts in your research question, we first have to understand what we think about them. As an aside, the word concept has come up quite a bit, and it is important to be sure we have a shared understanding of that term. A concept is the notion or image that we conjure up when we think of some cluster of related observations or ideas. For example, masculinity is a concept. What do you think of when you hear that word? Presumably, you imagine some set of behaviors and perhaps even a particular style of self-presentation. Of course, we can’t necessarily assume that everyone conjures up the same set of ideas or images when they hear the word masculinity . While there are many possible ways to define the term and some may be more common or have more support than others, there is no universal definition of masculinity. What counts as masculine may shift over time, from culture to culture, and even from individual to individual (Kimmel, 2008). This is why defining our concepts is so important.\

Not all researchers clearly explain their theoretical or conceptual framework for their study, but they should! Without understanding how a researcher has defined their key concepts, it would be nearly impossible to understand the meaning of that researcher’s findings and conclusions. Back in Chapter 7 , you developed a theoretical framework for your study based on a survey of the theoretical literature in your topic area. If you haven’t done that yet, consider flipping back to that section to familiarize yourself with some of the techniques for finding and using theories relevant to your research question. Continuing with our example on masculinity, we would need to survey the literature on theories of masculinity. After a few queries on masculinity, I found a wonderful article by Wong (2010) [6] that analyzed eight years of the journal Psychology of Men & Masculinity and analyzed how often different theories of masculinity were used . Not only can I get a sense of which theories are more accepted and which are more marginal in the social science on masculinity, I am able to identify a range of options from which I can find the theory or theories that will inform my project.

Identify a specific theory (or more than one theory) and how it helps you understand…

- Your independent variable(s).

- Your dependent variable(s).

- The relationship between your independent and dependent variables.

Rather than completing this exercise from scratch, build from your theoretical or conceptual framework developed in previous chapters.

In quantitative methods, conceptualization involves writing out clear, concise definitions for our key concepts. These are the kind of definitions you are used to, like the ones in a dictionary. A conceptual definition involves defining a concept in terms of other concepts, usually by making reference to how other social scientists and theorists have defined those concepts in the past. Of course, new conceptual definitions are created all the time because our conceptual understanding of the world is always evolving.

Conceptualization is deceptively challenging—spelling out exactly what the concepts in your research question mean to you. Following along with our example, think about what comes to mind when you read the term masculinity. How do you know masculinity when you see it? Does it have something to do with men or with social norms? If so, perhaps we could define masculinity as the social norms that men are expected to follow. That seems like a reasonable start, and at this early stage of conceptualization, brainstorming about the images conjured up by concepts and playing around with possible definitions is appropriate. However, this is just the first step. At this point, you should be beyond brainstorming for your key variables because you have read a good amount of research about them

In addition, we should consult previous research and theory to understand the definitions that other scholars have already given for the concepts we are interested in. This doesn’t mean we must use their definitions, but understanding how concepts have been defined in the past will help us to compare our conceptualizations with how other scholars define and relate concepts. Understanding prior definitions of our key concepts will also help us decide whether we plan to challenge those conceptualizations or rely on them for our own work. Finally, working on conceptualization is likely to help in the process of refining your research question to one that is specific and clear in what it asks. Conceptualization and operationalization (next section) are where “the rubber meets the road,” so to speak, and you have to specify what you mean by the question you are asking. As your conceptualization deepens, you will often find that your research question becomes more specific and clear.

If we turn to the literature on masculinity, we will surely come across work by Michael Kimmel , one of the preeminent masculinity scholars in the United States. After consulting Kimmel’s prior work (2000; 2008), [7] we might tweak our initial definition of masculinity. Rather than defining masculinity as “the social norms that men are expected to follow,” perhaps instead we’ll define it as “the social roles, behaviors, and meanings prescribed for men in any given society at any one time” (Kimmel & Aronson, 2004, p. 503). [8] Our revised definition is more precise and complex because it goes beyond addressing one aspect of men’s lives (norms), and addresses three aspects: roles, behaviors, and meanings. It also implies that roles, behaviors, and meanings may vary across societies and over time. Using definitions developed by theorists and scholars is a good idea, though you may find that you want to define things your own way.