- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Effectiveness of...

Effectiveness of weight management interventions for adults delivered in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

- Related content

- Peer review

- Claire D Madigan , senior research associate 1 ,

- Henrietta E Graham , doctoral candidate 1 ,

- Elizabeth Sturgiss , NHMRC investigator 2 ,

- Victoria E Kettle , research associate 1 ,

- Kajal Gokal , senior research associate 1 ,

- Greg Biddle , research associate 1 ,

- Gemma M J Taylor , reader 3 ,

- Amanda J Daley , professor of behavioural medicine 1

- 1 Centre for Lifestyle Medicine and Behaviour (CLiMB), The School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences, Loughborough University, Loughborough LE11 3TU, UK

- 2 School of Primary and Allied Health Care, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

- 3 Department of Psychology, Addiction and Mental Health Group, University of Bath, Bath, UK

- Correspondence to: C D Madigan c.madigan{at}lboro.ac.uk (or @claire_wm and @lboroclimb on Twitter)

- Accepted 26 April 2022

Objective To examine the effectiveness of behavioural weight management interventions for adults with obesity delivered in primary care.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

Eligibility criteria for selection of studies Randomised controlled trials of behavioural weight management interventions for adults with a body mass index ≥25 delivered in primary care compared with no treatment, attention control, or minimal intervention and weight change at ≥12 months follow-up.

Data sources Trials from a previous systematic review were extracted and the search completed using the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, PubMed, and PsychINFO from 1 January 2018 to 19 August 2021.

Data extraction and synthesis Two reviewers independently identified eligible studies, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Meta-analyses were conducted with random effects models, and a pooled mean difference for both weight (kg) and waist circumference (cm) were calculated.

Main outcome measures Primary outcome was weight change from baseline to 12 months. Secondary outcome was weight change from baseline to ≥24 months. Change in waist circumference was assessed at 12 months.

Results 34 trials were included: 14 were additional, from a previous review. 27 trials (n=8000) were included in the primary outcome of weight change at 12 month follow-up. The mean difference between the intervention and comparator groups at 12 months was −2.3 kg (95% confidence interval −3.0 to −1.6 kg, I 2 =88%, P<0.001), favouring the intervention group. At ≥24 months (13 trials, n=5011) the mean difference in weight change was −1.8 kg (−2.8 to −0.8 kg, I 2 =88%, P<0.001) favouring the intervention. The mean difference in waist circumference (18 trials, n=5288) was −2.5 cm (−3.2 to −1.8 cm, I 2 =69%, P<0.001) in favour of the intervention at 12 months.

Conclusions Behavioural weight management interventions for adults with obesity delivered in primary care are effective for weight loss and could be offered to members of the public.

Systematic review registration PROSPERO CRD42021275529.

Introduction

Obesity is associated with an increased risk of diseases such as cancer, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease, leading to early mortality. 1 2 3 More recently, obesity is a risk factor for worse outcomes with covid-19. 4 5 Because of this increased risk, health agencies and governments worldwide are focused on finding effective ways to help people lose weight. 6

Primary care is an ideal setting for delivering weight management services, and international guidelines recommend that doctors should opportunistically screen and encourage patients to lose weight. 7 8 On average, most people consult a primary care doctor four times yearly, providing opportunities for weight management interventions. 9 10 A systematic review of randomised controlled trials by LeBlanc et al identified behavioural interventions that could potentially be delivered in primary care, or involved referral of patients by primary care professionals, were effective for weight loss at 12-18 months follow-up (−2.4 kg, 95% confidence interval −2.9 to−1.9 kg). 11 However, this review included trials with interventions that the review authors considered directly transferrable to primary care, but not all interventions involved primary care practitioners. The review included interventions that were entirely delivered by university research employees, meaning implementation of these interventions might differ if offered in primary care, as has been the case in other implementation research of weight management interventions, where effects were smaller. 12 As many similar trials have been published after this review, an updated review would be useful to guide health policy.

We examined the effectiveness of weight loss interventions delivered in primary care on measures of body composition (weight and waist circumference). We also identified characteristics of effective weight management programmes for policy makers to consider.

This systematic review was registered on PROSPERO and is reported according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement. 13 14

Eligibility criteria

We considered studies to be eligible for inclusion if they were randomised controlled trials, comprised adult participants (≥18 years), and evaluated behavioural weight management interventions delivered in primary care that focused on weight loss. A primary care setting was broadly defined as the first point of contact with the healthcare system, providing accessible, continued, comprehensive, and coordinated care, focused on long term health. 15 Delivery in primary care was defined as the majority of the intervention being delivered by medical and non-medical clinicians within the primary care setting. Table 1 lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

- View inline

We extracted studies from the systematic review by LeBlanc et al that met our inclusion criteria. 11 We also searched the exclusions in this review because the researchers excluded interventions specifically for diabetes management, low quality trials, and only included studies from an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country, limiting the scope of the findings.

We searched for studies in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, PubMed, and PsychINFO from 1 January 2018 to 19 August 2021 (see supplementary file 1). Reference lists of previous reviews 16 17 18 19 20 21 and included trials were hand searched.

Data extraction

Results were uploaded to Covidence, 22 a software platform used for screening, and duplicates removed. Two independent reviewers screened study titles, abstracts, and full texts. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by a third reviewer. All decisions were recorded in Covidence, and reviewers were blinded to each other’s decisions. Covidence calculates proportionate agreement as a measure of inter-rater reliability, and data are reported separately by title or abstract screening and full text screening. One reviewer extracted data on study characteristics (see supplementary table 1) and two authors independently extracted data on weight outcomes. We contacted the authors of four included trials (from the updated search) for further information. 23 24 25 26

Outcomes, summary measures, and synthesis of results

The primary outcome was weight change from baseline to 12 months. Secondary outcomes were weight change from baseline to ≥24 months and from baseline to last follow-up (to include as many trials as possible), and waist circumference from baseline to 12 months. Supplementary file 2 details the prespecified subgroup analysis that we were unable to complete. The prespecified subgroup analyses that could be completed were type of healthcare professional who delivered the intervention, country, intensity of the intervention, and risk of bias rating.

Healthcare professional delivering intervention —From the data we were able to compare subgroups by type of healthcare professional: nurses, 24 26 27 28 general practitioners, 23 29 30 31 and non-medical practitioners (eg, health coaches). 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 Some of the interventions delivered by non-medical practitioners were supported, but not predominantly delivered, by GPs. Other interventions were delivered by a combination of several different practitioners—for example, it was not possible to determine whether a nurse or dietitian delivered the intervention. In the subgroup analysis of practitioner delivery, we refer to this group as “other.”

Country —We explored the effectiveness of interventions by country. Only countries with three or more trials were included in subgroup analyses (United Kingdom, United States, and Spain).

Intensity of interventions —As the median number of contacts was 12, we categorised intervention groups according to whether ≤11 or ≥12 contacts were required.

Risk of bias rating —Studies were classified as being at low, unclear, and high risk of bias. Risk of bias was explored as a potential influence on the results.

Meta-analyses

Meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.4. 40 As we expected the treatment effects to differ because of the diversity of intervention components and comparator conditions, we used random effects models. A pooled mean difference was calculated for each analysis, and variance in heterogeneity between studies was compared using the I 2 and τ 2 statistics. We generated funnel plots to evaluate small study effects. If more than two intervention groups existed, we divided the number of participants in the comparator group by the number of intervention groups and analysed each individually. Nine trials were cluster randomised controlled trials. The trials had adjusted their results for clustering, or adjustment had been made in the previous systematic review by LeBlanc et al. 11 One trial did not report change in weight by group. 26 We calculated the mean weight change and standard deviation using a standard formula, which imputes a correlation for the baseline and follow-up weights. 41 42 In a non-prespecified analysis, we conducted univariate and multivariable metaregression (in Stata) using a random effects model to examine the association between number of sessions and type of interventionalist on study effect estimates.

Risk of bias

Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool v2. 43 For incomplete outcome data we defined a high risk of bias as ≥20% attrition. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third author.

Patient and public involvement

The study idea was discussed with patients and members of the public. They were not, however, included in discussions about the design or conduct of the study.

The search identified 11 609 unique study titles or abstracts after duplicates were removed ( fig 1 ). After screening, 97 full text articles were assessed for eligibility. The proportionate agreement ranged from 0.94 to 1.0 for screening of titles or abstracts and was 0.84 for full text screening. Fourteen new trials met the inclusion criteria. Twenty one studies from the review by LeBlanc et al met our eligibility criteria and one study from another systematic review was considered eligible and included. 44 Some studies had follow-up studies (ie, two publications) that were found in both the second and the first search; hence the total number of trials was 34 and not 36. Of the 34 trials, 27 (n=8000 participants) were included in the primary outcome meta-analysis of weight change from baseline to 12 months, 13 (n=5011) in the secondary outcome from baseline to ≥24 months, and 30 (n=8938) in the secondary outcome for weight change from baseline to last follow-up. Baseline weight was accounted for in 18 of these trials, but in 14 24 26 29 30 31 32 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 it was unclear or the trials did not consider baseline weight. Eighteen trials (n=5288) were included in the analysis of change in waist circumference at 12 months.

Studies included in systematic review of effectiveness of behavioural weight management interventions in primary care. *Studies were merged in Covidence if they were from same trial

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Study characteristics

Included trials (see supplementary table 1) were individual randomised controlled trials (n=25) 24 25 26 27 28 29 32 33 34 35 38 39 41 44 45 46 47 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 59 or cluster randomised controlled trials (n=9). 23 30 31 36 37 48 49 57 58 Most were conducted in the US (n=14), 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 45 48 51 54 55 UK (n=7), 27 28 38 41 47 57 58 and Spain (n=4). 25 44 46 49 The median number of participants was 276 (range 50-864).

Four trials included only women (average 65.9% of women). 31 48 51 59 The mean BMI at baseline was 35.2 (SD 4.2) and mean age was 48 (SD 9.7) years. The interventions lasted between one session (with participants subsequently following the programme unassisted for three months) and several sessions over three years (median 12 months). The follow-up period ranged from 12 months to three years (median 12 months). Most trials excluded participants who had lost weight in the past six months and were taking drugs that affected weight.

Meta-analysis

Overall, 27 trials were included in the primary meta-analysis of weight change from baseline to 12 months. Three trials could not be included in the primary analysis as data on weight were only available at two and three years and not 12 months follow-up, but we included these trials in the secondary analyses of last follow-up and ≥24 months follow-up. 26 44 50 Four trials could not be included in the meta-analysis as they did not present data in a way that could be synthesised (ie, measures of dispersion). 25 52 53 58 The mean difference was −2.3 kg (95% confidence interval −3.0 to −1.6 kg, I 2 =88%, τ 2 =3.38; P<0.001) in favour of the intervention group ( fig 2 ). We found no evidence of publication bias (see supplementary fig 1). Absolute weight change was −3.7 (SD 6.1) kg in the intervention group and −1.4 (SD 5.5) kg in the comparator group.

Mean difference in weight at 12 months by weight management programme in primary care (intervention) or no treatment, different content, or minimal intervention (control). SD=standard deviation

Supplementary file 2 provides a summary of the main subgroup analyses.

Weight change

The mean difference in weight change at the last follow-up was −1.9 kg (95% confidence interval −2.5 to −1.3 kg, I 2 =81%, τ 2 =2.15; P<0.001). Absolute weight change was −3.2 (SD 6.4) kg in the intervention group and −1.2 (SD 6.0) kg in the comparator group (see supplementary figs 2 and 3).

At the 24 month follow-up the mean difference in weight change was −1.8 kg (−2.8 to −0.8 kg, I 2 =88%, τ 2 =3.13; P<0.001) (see supplementary fig 4). As the weight change data did not differ between the last follow-up and ≥24 months, we used the weight data from the last follow-up in subgroup analyses.

In subgroup analyses of type of interventionalist, differences were significant (P=0.005) between non-medical practitioners, GPs, nurses, and other people who delivered interventions (see supplementary fig 2).

Participants who had ≥12 contacts during interventions lost significantly more weight than those with fewer contacts (see supplementary fig 6). The association remained after adjustment for type of interventionalist.

Waist circumference

The mean difference in waist circumference was −2.5 cm (95% confidence interval −3.2 to −1.8 cm, I 2 =69%, τ 2 =1.73; P<0.001) in favour of the intervention at 12 months ( fig 3 ). Absolute changes were −3.7 cm (SD 7.8 cm) in the intervention group and −1.3 cm (SD 7.3) in the comparator group.

Mean difference in waist circumference at 12 months. SD=standard deviation

Risk of bias was considered to be low in nine trials, 24 33 34 35 39 41 47 55 56 unclear in 12 trials, 25 27 28 29 32 45 46 50 51 52 54 59 and high in 13 trials 23 26 30 31 36 37 38 44 48 49 53 57 58 ( fig 4 ). No significant (P=0.65) differences were found in subgroup analyses according to level of risk of bias from baseline to 12 months (see supplementary fig 7).

Risk of bias in included studies

Worldwide, governments are trying to find the most effective services to help people lose weight to improve the health of populations. We found weight management interventions delivered by primary care practitioners result in effective weight loss and reduction in waist circumference and these interventions should be considered part of the services offered to help people manage their weight. A greater number of contacts between patients and healthcare professionals led to more weight loss, and interventions should be designed to include at least 12 contacts (face-to-face or by telephone, or both). Evidence suggests that interventions delivered by non-medical practitioners were as effective as those delivered by GPs (both showed statistically significant weight loss). It is also possible that more contacts were made with non-medical interventionalists, which might partially explain this result, although the metaregression analysis suggested the effect remained after adjustment for type of interventionalist. Because most comparator groups had fewer contacts than intervention groups, it is not known whether the effects of the interventions are related to contact with interventionalists or to the content of the intervention itself.

Although we did not determine the costs of the programme, it is likely that interventions delivered by non-medical practitioners would be cheaper than GP and nurse led programmes. 41 Most of the interventions delivered by non-medical practitioners involved endorsement and supervision from GPs (ie, a recommendation or checking in to see how patients were progressing), and these should be considered when implementing these types of weight management interventions in primary care settings. Our findings suggest that a combination of practitioners would be most effective because GPs might not have the time for 12 consultations to support weight management.

Although the 2.3 kg greater weight loss in the intervention group may seem modest, just 2-5% in weight loss is associated with improvements in systolic blood pressure and glucose and triglyceride levels. 60 The confidence intervals suggest a potential range of weight loss and that these interventions might not provide as much benefit to those with a higher BMI. Patients might not find an average weight loss of 3.7 kg attractive, as many would prefer to lose more weight; explaining to patients the benefits of small weight losses to health would be important.

Strengths and limitations of this review

Our conclusions are based on a large sample of about 8000 participants, and 12 of these trials were published since 2018. It was occasionally difficult to distinguish who delivered the interventions and how they were implemented. We therefore made some assumptions at the screening stage about whether the interventionalists were primary care practitioners or if most of the interventions were delivered in primary care. These discussions were resolved by consensus. All included trials measured weight, and we excluded those that used self-reported data. Dropout rates are important in weight management interventions as those who do less well are less likely to be followed-up. We found that participants in trials with an attrition rate of 20% or more lost less weight and we are confident that those with high attrition rates have not inflated the results. Trials were mainly conducted in socially economic developed countries, so our findings might not be applicable to all countries. The meta-analyses showed statistically significant heterogeneity, and our prespecified subgroups analysis explained some, but not all, of the variance.

Comparison with other studies

The mean difference of −2.3 kg in favour of the intervention group at 12 months is similar to the findings in the review by LeBlanc et al, who reported a reduction of −2.4 kg in participants who received a weight management intervention in a range of settings, including primary care, universities, and the community. 11 61 This is important because the review by LeBlanc et al included interventions that were not exclusively conducted in primary care or by primary care practitioners. Trials conducted in university or hospital settings are not typically representative of primary care populations and are often more intensive than trials conducted in primary care as a result of less constraints on time. Thus, our review provides encouraging findings for the implementation of weight management interventions delivered in primary care. The findings are of a similar magnitude to those found in a trial by Ahern et al that tested primary care referral to a commercial programme, with a difference of −2.7 kg (95% confidence interval −3.9 to −1.5 kg) reported at 12 month follow-up. 62 The trial by Ahern et al also found a difference in waist circumference of −4.1 cm (95% confidence interval −5.5 to −2.3 cm) in favour of the intervention group at 12 months. Our finding was smaller at −2.5 cm (95% confidence interval −3.2 to −1.8 cm). Some evidence suggests clinical benefits from a reduction of 3 cm in waist circumference, particularly in decreased glucose levels, and the intervention groups showed a 3.7 cm absolute change in waist circumference. 63

Policy implications and conclusions

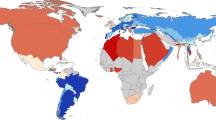

Weight management interventions delivered in primary care are effective and should be part of services offered to members of the public to help them manage weight. As about 39% of the world’s population is living with obesity, helping people to manage their weight is an enormous task. 64 Primary care offers good reach into the community as the first point of contact in the healthcare system and the remit to provide whole person care across the life course. 65 When developing weight management interventions, it is important to reflect on resource availability within primary care settings to ensure patients’ needs can be met within existing healthcare systems. 66

We did not examine the equity of interventions, but primary care interventions may offer an additional service and potentially help those who would not attend a programme delivered outside of primary care. Interventions should consist of 12 or more contacts, and these findings are based on a mixture of telephone and face-to-face sessions. Previous evidence suggests that GPs find it difficult to raise the issue of weight with patients and are pessimistic about the success of weight loss interventions. 67 Therefore, interventions should be implemented with appropriate training for primary care practitioners so that they feel confident about helping patients to manage their weight. 68

Unanswered questions and future research

A range of effective interventions are available in primary care settings to help people manage their weight, but we found substantial heterogeneity. It was beyond the scope of this systematic review to examine the specific components of the interventions that may be associated with greater weight loss, but this could be investigated by future research. We do not know whether these interventions are universally suitable and will decrease or increase health inequalities. As the data are most likely collected in trials, an individual patient meta-analysis is now needed to explore characteristics or factors that might explain the variance. Most of the interventions excluded people prescribed drugs that affect weight gain, such as antipsychotics, glucocorticoids, and some antidepressants. This population might benefit from help with managing their weight owing to the side effects of these drug classes on weight gain, although we do not know whether the weight management interventions we investigated would be effective in this population. 69

What is already known on this topic

Referral by primary care to behavioural weight management programmes is effective, but the effectiveness of weight management interventions delivered by primary care is not known

Systematic reviews have provided evidence for weight management interventions, but the latest review of primary care delivered interventions was published in 2014

Factors such as intensity and delivery mechanisms have not been investigated and could influence the effectiveness of weight management interventions delivered by primary care

What this study adds

Weight management interventions delivered by primary care are effective and can help patients to better manage their weight

At least 12 contacts (telephone or face to face) are needed to deliver weight management programmes in primary care

Some evidence suggests that weight loss after weight management interventions delivered by non-medical practitioners in primary care (often endorsed and supervised by doctors) is similar to that delivered by clinician led programmes

Ethics statements

Ethical approval.

Not required.

Data availability statement

Additional data are available in the supplementary files.

Contributors: CDM and AJD conceived the study, with support from ES. CDM conducted the search with support from HEG. CDM, AJD, ES, HEG, KG, GB, and VEK completed the screening and full text identification. CDM and VEK completed the risk of bias assessment. CDM extracted data for the primary outcome and study characteristics. HEJ, GB, and KG extracted primary outcome data. CDM completed the analysis in RevMan, and GMJT completed the metaregression analysis in Stata. CDM drafted the paper with AJD. All authors provided comments on the paper. CDM acts as guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: AJD is supported by a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) research professorship award. This research was supported by the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. ES’s salary is supported by an investigator grant (National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia). GT is supported by a Cancer Research UK fellowship. The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: This research was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Leicester Biomedical Research Centre; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The lead author (CDM) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported, and that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: We plan to disseminate these research findings to a wider community through press releases, featuring on the Centre for Lifestyle Medicine and Behaviour website ( www.lboro.ac.uk/research/climb/ ) via our policy networks, through social media platforms, and presentation at conferences.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

- Renehan AG ,

- Heller RF ,

- Bansback N ,

- Birmingham CL ,

- Abdullah A ,

- Peeters A ,

- de Courten M ,

- Stoelwinder J

- Aghili SMM ,

- Ebrahimpur M ,

- Arjmand B ,

- KETLAK Study Group

- ↵ Department of Health and Social Care. New specialised support to help those living with obesity to lose weight UK2021. www.gov.uk/government/news/new-specialised-support-to-help-those-living-with-obesity-to-lose-weight [accessed 08/02/2021].

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

- ↵ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Maintaining a Healthy Weight and Preventing Excess Weight Gain in Children and Adults. Cost Effectiveness Considerations from a Population Modelling Viewpoint. 2014, NICE. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng7/evidence/evidence-review-2-qualitative-evidence-review-of-the-most-acceptable-ways-to-communicate-information-about-individually-modifiable-behaviours-to-help-maintain-a-healthy-weight-or-prevent-excess-weigh-8733713.

- ↵ The Health Foundation. Use of primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic. 17/09/2020: The Health Foundation, 2020.

- ↵ Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient Experiences in Australia: Summary of Findings, 2017-18. 2019 ed. Canberra, Australia, 2018. www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Lookup/4839.0Main+Features12017-18?OpenDocument.

- LeBlanc ES ,

- Patnode CD ,

- Webber EM ,

- Redmond N ,

- Rushkin M ,

- O’Connor EA

- Damschroder LJ ,

- Liberati A ,

- Tetzlaff J ,

- Altman DG ,

- PRISMA Group

- McKenzie JE ,

- Bossuyt PM ,

- ↵ WHO. Main terminology: World Health Organization; 2004. www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Health-systems/primary-health-care/main-terminology [accessed 09.12.21].

- Aceves-Martins M ,

- Robertson C ,

- REBALANCE team

- Glasziou P ,

- Isenring E ,

- Chisholm A ,

- Wakayama LN ,

- Kettle VE ,

- Madigan CD ,

- ↵ Covidence [program]. Melbourne, 2021.

- Welzel FD ,

- Carrington MJ ,

- Fernández-Ruiz VE ,

- Ramos-Morcillo AJ ,

- Solé-Agustí M ,

- Paniagua-Urbano JA ,

- Armero-Barranco D

- Bräutigam-Ewe M ,

- Hildingh C ,

- Yardley L ,

- Christian JG ,

- Bessesen DH ,

- Christian KK ,

- Goldstein MG ,

- Martin PD ,

- Dutton GR ,

- Horswell RL ,

- Brantley PJ

- Wadden TA ,

- Rogers MA ,

- Berkowitz RI ,

- Kumanyika SK ,

- Morales KH ,

- Allison KC ,

- Rozenblum R ,

- De La Cruz BA ,

- Katzmarzyk PT ,

- Martin CK ,

- Newton RL Jr . ,

- Nanchahal K ,

- Holdsworth E ,

- ↵ RevMan [program]. 5.4 version: Copenhagen, 2014.

- Sterne JAC ,

- Savović J ,

- Gomez-Huelgas R ,

- Jansen-Chaparro S ,

- Baca-Osorio AJ ,

- Mancera-Romero J ,

- Tinahones FJ ,

- Bernal-López MR

- Delahanty LM ,

- Tárraga Marcos ML ,

- Panisello Royo JM ,

- Carbayo Herencia JA ,

- Beeken RJ ,

- Leurent B ,

- Vickerstaff V ,

- Hagobian T ,

- Brannen A ,

- Rodriguez-Cristobal JJ ,

- Alonso-Villaverde C ,

- Panisello JM ,

- Conroy MB ,

- Spadaro KC ,

- Takasawa N ,

- Mashiyama Y ,

- Pritchard DA ,

- Hyndman J ,

- Jarjoura D ,

- Smucker W ,

- Baughman K ,

- Bennett GG ,

- Steinberg D ,

- Zaghloul H ,

- Chagoury O ,

- Leslie WS ,

- Barnes AC ,

- Summerbell CD ,

- Greenwood DC ,

- Huseinovic E ,

- Leu Agelii M ,

- Hellebö Johansson E ,

- Winkvist A ,

- Look AHEAD Research Group

- LeBlanc EL ,

- Wheeler GM ,

- Aveyard P ,

- de Koning L ,

- Chiuve SE ,

- Willett WC ,

- ↵ World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight, 2021, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- Starfield B ,

- Sturgiss E ,

- Dewhurst A ,

- Devereux-Fitzgerald A ,

- Haesler E ,

- van Weel C ,

- Gulliford MC

- Fassbender JE ,

- Sarwer DB ,

- Brekke HK ,

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 27 January 2020

Epidemiology and Population Health

Evidence from big data in obesity research: international case studies

- Emma Wilkins 1 ,

- Ariadni Aravani 1 ,

- Amy Downing 1 ,

- Adam Drewnowski 2 ,

- Claire Griffiths 3 ,

- Stephen Zwolinsky 3 ,

- Mark Birkin 4 ,

- Seraphim Alvanides 5 , 6 &

- Michelle A. Morris ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9325-619X 1

International Journal of Obesity volume 44 , pages 1028–1040 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

948 Accesses

4 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Risk factors

- Signs and symptoms

Background/objective

Obesity is thought to be the product of over 100 different factors, interacting as a complex system over multiple levels. Understanding the drivers of obesity requires considerable data, which are challenging, costly and time-consuming to collect through traditional means. Use of ‘big data’ presents a potential solution to this challenge. Big data is defined by Delphi consensus as: always digital , has a large sample size, and a large volume or variety or velocity of variables that require additional computing power (Vogel et al. Int J Obes. 2019). ‘Additional computing power’ introduces the concept of big data analytics. The aim of this paper is to showcase international research case studies presented during a seminar series held by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Strategic Network for Obesity in the UK. These are intended to provide an in-depth view of how big data can be used in obesity research, and the specific benefits, limitations and challenges encountered.

Methods and results

Three case studies are presented. The first investigated the influence of the built environment on physical activity. It used spatial data on green spaces and exercise facilities alongside individual-level data on physical activity and swipe card entry to leisure centres, collected as part of a local authority exercise class initiative. The second used a variety of linked electronic health datasets to investigate associations between obesity surgery and the risk of developing cancer. The third used data on tax parcel values alongside data from the Seattle Obesity Study to investigate sociodemographic determinants of obesity in Seattle.

Conclusions

The case studies demonstrated how big data could be used to augment traditional data to capture a broader range of variables in the obesity system. They also showed that big data can present improvements over traditional data in relation to size, coverage, temporality, and objectivity of measures. However, the case studies also encountered challenges or limitations; particularly in relation to hidden/unforeseen biases and lack of contextual information. Overall, despite challenges, big data presents a relatively untapped resource that shows promise in helping to understand drivers of obesity.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 20,95 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Non-traditional data sources in obesity research: a systematic review of their use in the study of obesogenic environments

Julia Mariel Wirtz Baker, Sonia Alejandra Pou, … Laura Rosana Aballay

Trends in the prevalence of adult overweight and obesity in Australia, and its association with geographic remoteness

Syed Afroz Keramat, Khorshed Alam, … Rubayyat Hashmi

Best practices for analyzing large-scale health data from wearables and smartphone apps

Jennifer L. Hicks, Tim Althoff, … Scott L. Delp

Davison KK, Birch LL. Childhood overweight: a contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obes Rev. 2001;2:159–71.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Egger G, Swinburn B. An “ecological” approach to the obesity pandemic. BMJ. 1997;315:477–80.

Harrison K, Bost KK, McBride BA, Donovan SM, Grigsby-Toussaint DS, Kim J, et al. Toward a developmental conceptualization of contributors to overweight and obesity in childhood: the six-Cs model. Child Dev Perspect. 2011;5:50–8.

Article Google Scholar

Butland B, Jebb S, Kopelman P, McPherson K, Thomas S, Mardell J et al. Foresight. Tackling obesities: future choices—project report. Government Office for Science; 2007.

Rutter HR, Bes-Rastrollo M, de Henauw S, Lahti-Koski M, Lehtinen-Jacks S, Mullerova D, et al. Balancing upstream and downstream measures to tackle the obesity epidemic: a position statement from the European association for the study of obesity. Obes Facts. 2017;10:61–3.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mittelstadt BD, Floridi L. The ethics of big data: current and foreseeable issues in biomedical contexts. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22:303–41.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kaisler S, Armour F, Espinosa JA, Money W. Big data: issues and challenges moving forward. In: Proceedings of the 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Association for Computing Machinery Digital Library; 2013. p. 995–1004.

Herland M, Khoshgoftaar TM, Wald R. A review of data mining using big data in health informatics. J Big Data. 2014;1: https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-1115-1-2 .

Vogel C, Zwolinsky S, Griffiths C, Hobbs M, Henderson E, Wilkins E. A Delphi study to build consensus on the definition and use of big data in obesity research. Int J Obes. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0313-9 .

Morris M, Birkin M. The ESRC strategic network for obesity: tackling obesity with big data. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1948–50.

Timmins K, Green M, Radley D, Morris M, Pearce J. How has big data contributed to obesity research? A review of the literature. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1951–62.

Monsivais P, Francis O, Lovelace R, Chang M, Strachan E, Burgoine T. Data visualisation to support obesity policy: case studies of data tools for planning and transport policy in the UK. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1977–86.

Morris M, Wilkins E, Timmins K, Bryant M, Birkin M, Griffiths C. Can big data solve a big problem? Reporting the obesity data landscape in line with the Foresight obesity system map. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1963–76.

Vayena E, Salathé M, Madoff LC, Brownstein JS. Ethical challenges of big data in public health. PLOS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1003904.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Silver LD, Ng SW, Ryan-Ibarra S, Taillie LS, Induni M, Miles DR, et al. Changes in prices, sales, consumer spending, and beverage consumption one year after a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages in Berkeley, California, US: a before-and-after study. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002283.

Gore RJ, Diallo S, Padilla J. You are what you tweet: connecting the geographic variation in america’s obesity rate to Twitter content. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0133505.

Nguyen QC, Li D, Meng H-W, Kath S, Nsoesie E, Li F, et al. Building a national neighborhood dataset from geotagged Twitter data for indicators of happiness, diet, and physical activity. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016;2:e158.

Hirsch JA, James P, Robinson JR, Eastman KM, Conley KD, Evenson KR, et al. Using MapMyFitness to place physical activity into neighborhood context. Front Public Health. 2014;2:1–9.

Althoff T, Hicks JL, King AC, Delp SL, Leskovec J. Large-scale physical activity data reveal worldwide activity inequality. Nature. 2017;547:336–9.

Kerr NL. HARKing: hypothesizing after the results are known. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 1998;2:196–217.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380:219–29.

Bennett JE, Li G, Foreman K, Best N, Kontis V, Pearson C, et al. The future of life expectancy and life expectancy inequalities in England and Wales: Bayesian spatiotemporal forecasting. Lancet. 2015;386:163–70.

World Health Organisation. Report of the Commission on ending childhood obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. Atlanta, GA, U.S.: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009.

Local Government Association. Building the foundations: tackling obesity through planning and development. London, UK: Local Government Association; 2016.

Burgoine T, Alvanides S, Lake AA. Creating ‘obesogenic realities’; Do our methodological choices make a difference when measuring the food environment? Int J Health Geogr. 2013;12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-12-33 .

Wilkins E, Morris M, Radley D, Griffiths C. Methods of measuring associations between the Retail Food Environment and weight status: Importance of classifications and metrics. SSM Popul Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100404 .

Bardou M, Barkun AN, Martel M. Obesity and colorectal cancer. Gut. 2013;62:933–47.

Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104–17.

Derogar M, Hull MA, Kant P, Östlund M, Lu Y, Lagergren J. Increased risk of colorectal cancer after obesity surgery. Ann Surg. 2013;258:983–8.

Kant P, Hull MA. Excess body weight and obesity—the link with gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:224–38.

Östlund MP, Lu Y, Lagergren J. Risk of obesity-related cancer after obesity surgery in a population-based cohort study. Ann Surg. 2010;252:972–6.

Sainsbury A, Goodlad RA, Perry SL, Pollard SG, Robins GG, Hull MA. Increased colorectal epithelial cell proliferation and crypt fission associated with obesity and roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17:1401–10.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Aravani A, Downing A, Thomas JD, Lagergren J, Morris EJA, Hull MA. Obesity surgery and risk of colorectal and other obesity-related cancers: an English population-based cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;53:99–104.

Openshaw S. The modifiable areal unit problem. In: Concepts and techniques in modern geography. Norwich: Geo Books; 1984. p. 1–41.

Kwan M-P. The uncertain geographic context problem. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2012;102:958–68.

Di Zhu X, Yang Y, Liu X. The importance of housing to the accumulation of household net wealth. Harvard, USA: Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University; 2003.

Rehm CD, Moudon AV, Hurvitz PM, Drewnowski A. Residential property values are associated with obesity among women in King County, WA, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:491–5.

Drewnowski A, Buszkiewicz J, Aggarwal A. Soda, salad, and socioeconomic status: findings from the Seattle Obesity Study (SOS). SSM Popul Health. 2019;7:e100339.

Birkin M, Morris MA, Birkin TM, Lovelace R. Using census data in microsimulation modelling. In: Stillwell J, Duke-Williams O, editors. The Routledge handbook of census resources, methods and applications. 1st ed. Routledge: IJO publication; 2018.

Jiao J, Drewnowski A, Moudon AV, Aggarwal A, Oppert J-M, Charreire H, et al. The impact of area residential property values on self-rated health: a cross-sectional comparative study of Seattle and Paris. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:68–74.

Nguyen DM, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterol Clinics. 2010;39:1–7.

Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2001;55:111–22.

Timperio A, Salmon J, Telford A, Crawford D. Perceptions of local neighbourhood environments and their relationship to childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Obes. 2005;29:170–5.

Roda C, Charreire H, Feuillet T, Mackenbach JD, Compernolle S, Glonti K, et al. Mismatch between perceived and objectively measured environmental obesogenic features in European neighbourhoods. Obes Rev. 2016;17 S1:31–41.

Drewnowski A, Arterburn D, Zane J, Aggarwal A, Gupta S, Hurvitz PM, et al. The Moving to Health (M2H) approach to natural experiment research: a paradigm shift for studies on built environment and health. SSM Popul Health. 2019;7:100345.

Bourassa SC, Cantoni E, Hoesli M. Predicting house prices with spatial dependence a comparison of alternative methods. J Real Estate Res. 2010;32:139–60.

Google Scholar

Wilkins EL, Radley D, Morris MA, Griffiths C. Examining the validity and utility of two secondary sources of food environment data against street audits in England. Nutr J. 2017;16:1–13.

Nevalainen J, Erkkola M, Saarijarvi H, Nappila T, Fogelholm M. Large-scale loyalty card data in health research. Digit Health. 2018;4:2055207618816898.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Aiello L, Schifanello R, Quercia D, Del Prete L. Large-scale and high-resolution analysis of food purchases and health outcomes. EPJ Data Sci. 2019;8:14.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95.

Zwolinsky S, McKenna J, Pringle A, Widdop P, Griffiths C, Mellis M, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior clustering: segmentation to optimize active lifestyles. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:921–8.

Bauman A, Ainsworth BE, Sallis JF, Hagströmer M, Craig CL, Bull FC, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of sitting: a 20-country comparison using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:228–35.

Guerin PB, Diiriye RO, Corrigan C, Guerin B. Physical activity programs for refugee somali women: working out in a new country. Women & Health. 2003;38:83–99.

Pope L, Harvey J. The efficacy of incentives to motivate continued fitness-center attendance in college first-year students: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Health. 2014;62:81–90.

Cetateanu A, Jones A. Understanding the relationship between food environments, deprivation and childhood overweight and obesity: evidence from a cross sectional England-wide study. Health Place. 2014;27:68–76.

Harrison F, Burgoine T, Corder K, van Sluijs EM, Jones A. How well do modelled routes to school record the environments children are exposed to? A cross-sectional comparison of GIS-modelled and GPS-measured routes to school. Int J Health Geogr. 2014;13:5.

Ells LJ, Macknight N, Wilkinson JR. Obesity surgery in England: an examination of the health episode statistics 1996–2005. Obes Surg. 2007;17:400–5.

Nielsen JDJ, Laverty AA, Millett C, Mainous AG, Majeed A, Saxena S. Rising obesity-related hospital admissions among children and young people in England: National time trends study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65764.

Smittenaar C, Petersen K, Stewart K, Moitt N. Cancer incidence and mortality projections in the UK until 2035. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1147–55.

Wallington M, Saxon EB, Bomb M, Smittenaar R, Wickenden M, McPhail S, et al. 30-day mortality after systemic anticancer treatment for breast and lung cancer in England: a population-based, observational study. The Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1203–16.

Smolina K, Wright FL, Rayner M, Goldacre MJ. Determinants of the decline in mortality from acute myocardial infarction in England between 2002 and 2010: Linked national database study. BMJ. 2012;344:d8059.

Hanratty B, Lowson E, Grande G, Payne S, Addington-Hall J, Valtorta N, et al. Transitions at the end of life for older adults–patient, carer and professional perspectives: A mixed-methods study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2014. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr02170 .

Aggarwal A, Monsivais P, Cook AJ, Drewnowski A. Does diet cost mediate the relation between socioeconomic position and diet quality? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65:1059–66.

Drewnowski A, Aggarwal A, Tang W, Moudon AV. Residential property values predict prevalent obesity but do not predict 1-year weight change. Obesity. 2015;23:671–6.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The ESRC Strategic Network for Obesity was funded via ESRC grant number ES/N00941X/1. The authors would like to thank all of the network investigators ( https://www.cdrc.ac.uk/research/obesity/investigators/ ) and members ( https://www.cdrc.ac.uk/research/obesity/network-members/ ) for their participation in network meetings and discussion which contributed to the development of this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Leeds Institute for Data Analytics and School of Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

Emma Wilkins, Ariadni Aravani, Amy Downing & Michelle A. Morris

Center for Public Health Nutrition, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Adam Drewnowski

School of Sport, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, UK

Claire Griffiths & Stephen Zwolinsky

Leeds Institute for Data Analytics and School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

- Mark Birkin

Engineering and Environment, Northumbria University, Newcastle, UK

Seraphim Alvanides

GESIS—Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Cologne, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michelle A. Morris .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wilkins, E., Aravani, A., Downing, A. et al. Evidence from big data in obesity research: international case studies. Int J Obes 44 , 1028–1040 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-0532-8

Download citation

Received : 23 May 2019

Revised : 20 December 2019

Accepted : 07 January 2020

Published : 27 January 2020

Issue Date : May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-0532-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

- Julia Mariel Wirtz Baker

- Sonia Alejandra Pou

- Laura Rosana Aballay

International Journal of Obesity (2023)

Creating a long-term future for big data in obesity research

- Emma Wilkins

- Michelle A. Morris

International Journal of Obesity (2019)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 02 May 2019

Enhancing knowledge and coordination in obesity treatment: a case study of an innovative educational program

- Tonje C. Osmundsen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5776-6694 1 ,

- Unni Dahl 2 &

- Bård Kulseng 3 , 4

BMC Health Services Research volume 19 , Article number: 278 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

4380 Accesses

7 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Currently, there is a lack of knowledge, organisation and structure in modern health care systems to counter the global trend of obesity, which has become a major risk factor for noncommunicable diseases. Obesity increases the risk of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders and cancer. There is a need to strengthen integrated care between primary and secondary health care and to enhance care delivery suited for patients with complex, long-term problems such as obesity. This study aimed to explore how an educational program for General Practitioners (GPs) can contribute to increased knowledge and improved coordination between primary and secondary care in obesity treatment, and reports on these impacts as perceived by the informants.

In 2010, an educational program for the specialist training of GPs was launched at three hospitals in Central Norway opting for improved care delivery for patients with obesity. In contrast to the usual programs, this educational program was tailored to the needs of GPs by offering practice and training with a large number of patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes for an extended period of time. In order to investigate the outcomes of the program, a qualitative design was applied involving interviews with 13 GPs, head physicians and staff at the hospitals and in one municipality.

Through the program, participants strengthened care delivery by building knowledge and competence. They developed relations between primary and secondary care providers and established shared understanding and practices. The program also demonstrated improvement opportunities, especially concerning the involvement of municipalities.

Conclusions

The educational program promoted integrated care between primary and secondary care by establishing formal and informal relations, by improving service delivery through increased competence and by fostering shared understanding and practices between care levels. The educational program illustrates the combination of advanced high-quality training with the development of integrated care.

Peer Review reports

Obesity and diabetes are grave international health problems [ 1 , 2 ] and the economic burden for both patients and national economies is significant [ 3 ]. Obesity is a complex condition often involving several other chronic and serious diseases requiring lifelong follow-up [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. It often affects whole families and intervention is needed at multiple levels, including social and psychological dimensions. Treatment is therefore complex and time-consuming and poses a challenge for the organisation of health care services [ 7 , 8 ]. Currently, there is a lack of well-established integrated approaches for prevention and treatment across health care levels.

Treatment offerings

To tackle these challenges, the coordination of services needs to be improved [ 7 , 9 , 10 ]. In Norway, the Coordination Reform was launched in 2010 [ 11 ]. Here, as in other countries [ 12 ], integrated care is accompanied by goals for moving patients from secondary health care to primary care, increasing focus on prevention and health-promoting activities and patient involvement. Obese and overweight patients with related diseases have traditionally been offered treatment in primary care, but in recent years the number of patients with severe obesity and complications has increased and consequently, so has the number of patients referred to secondary health care. To counter such a development, primary and secondary health care providers should jointly develop integrated care based on an understanding of the disease’s complexity. In addition, knowledge and capacity at the primary health care level must be improved and services targeted at prevention and cure must be made available.

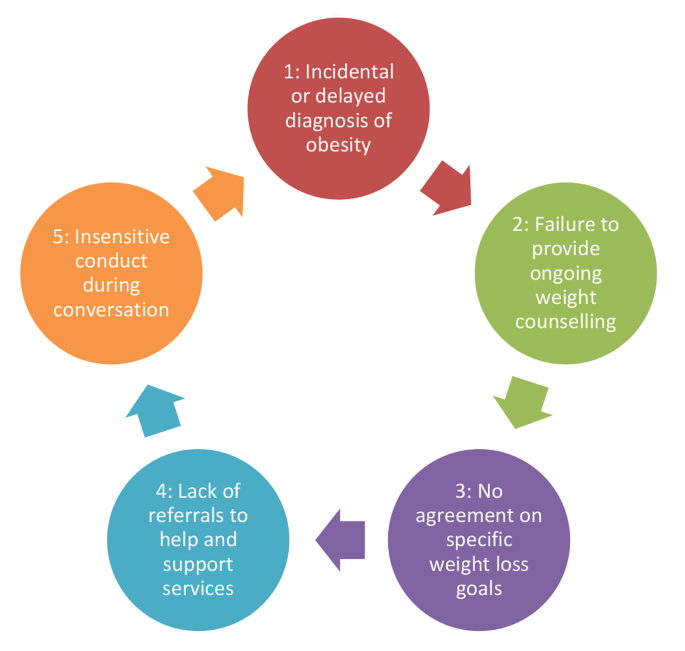

Although health care workers are key players in the effort to stop the obesity trend in the population and to prevent the complications of obesity, international research suggests that obese patients do not receive adequate help for their health problems. Studies have shown that health care providers’ treatment and attitude towards overweight and obese patients are governed by poor knowledge and inconsistencies [ 13 , 14 ] and have a strong weight bias, indicating stigma [ 15 , 16 ]. A mapping in Central Norway showed a lack of knowledge and tools for how to treat and prevent overweight and obesity [ 17 ]. Less than half of the obese patients who sought medical help for their lifestyle problems were advised to lose weight by their GP [ 18 ] or given exercise counselling [ 19 ], and while research has shown that such advice and counselling may have an effect on weight loss, it is inadequate [ 20 ]. Limited treatment contact is thought to be the main reason why modest weight loss is achieved [ 20 ]. There are available treatment guidelines for primary care, but there are currently few sufficiently effective established treatment offerings available to children and adults struggling with overweight and obesity within primary health care [ 21 ]. More extensive treatment in primary care is often randomly organised, at times by local enthusiasts. Treatment is difficult to establish in primary care because of the complexity involved in treating obesity, and while GPs are competent to diagnose obesity, there is a general lack in knowledge about treating the disease [ 13 , 14 ] and available time [ 20 ]. Furthermore, considering coordination between primary and secondary health care providers, integrated care for patients with obesity is underdeveloped [ 4 , 14 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]. In Norway, obese patients are normally referred to secondary health care when they have a Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 40 or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m 2 with complications of obesity, while children should have an iso-BMI > 35 or iso-BMI > 30 kg/m2 with complications of obesity [ 25 ]. However, until a patient reaches this stage in the development of the disease, few treatments are available, and when a patient is referred to secondary health care, a lack of coordination and cooperation between primary and secondary care leads to treatments that may be limited in scope and time.

Education of GP specialists in the health care system in Norway

The health care system in Norway is primarily a public system organised in two levels. Secondary healthcare services are owned and financed by the Ministry of Health and Care Services and managed through four regional health authorities. The primary care level includes general practitioners (GPs), nursing homes, home care services, maternal and child health centres and out-of-hours services. Primary care is organised and financed by the local authorities (municipalities). Even though GPs are organised as a part of the primary care level, GPs are private contractors and not organised in a shared formal organisation that can instruct GPs or act as a partner on behalf of GPs [ 26 ].

The educational program for becoming a GP specialist in Norway includes 1 year of practice at a hospital. Currently, there are no positions targeted at GPs’ educational needs, so a GP seeking specialization must apply for a regular specialist training position at a hospital. In most of these positions, the doctor is enrolled in the rota system. This means that candidates will often spend time in emergency admissions on evening and night shifts that are compensated by time off. This leaves little time to attend in-house patients and perform routine follow-up of patients, both of which are relevant for their practice as GPs.

Theoretical basis

Mur-Veeman et al. [ 27 ] have shown that organizational and financial splits between health care providers, such as those present in Norway between primary and secondary health care, hinder integrated care development and delivery. Organizational divides are closely linked to contradictory interests, separate professional cultures, power relations and mistrust between health care providers. Martinussen [ 28 ] has shown that the interaction between GPs and hospital physicians has improvement potential, and weak collaboration between GPs and hospitals has been the focus of several studies [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Delayed or inaccurate communication can have substantial implications for the quality of care, which is especially apparent when patients need lifelong follow-up. Efforts to strengthen integrated care can counteract such inadequate treatment at the interstices between providers. In this paper, integrated care is defined as “[ ] a coherent set of methods and models on the funding, administrative, organizational, service delivery and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment and collaboration within and between the cure and care sectors” [ 32 ].

There are many strategies available to foster integrated care. It is found that different commitments, goals and tasks can be major obstacles for collaboration between care levels [ 33 ]. Thus, defining roles and having a shared purpose is essential to achieve successful interorganizational collaboration [ 34 ]. Other approaches include training of medical staff, a focus on how they perform their responsibilities and tasks, and how they work together with colleagues and patients [ 32 ]. Face-to-face interaction is well known to foster trust and collaborative relations. This has also earlier been shown to apply to the relationships between GPs and hospital specialists [ 28 , 35 ]. Networking and collaboration both horizontally and vertically across health care providers promotes integrated care, as well as a “Shared understanding of patient needs, common professional language and criteria, the use of specific, agreed-upon practices and standards throughout the lifecycle of a particular disease or condition…” [ 32 ].

Fruitful integration between care levels is dependent on communication between primary and secondary health care providers [ 36 ], and this collaboration becomes even more important for patients with multiple complex conditions and needs [ 37 ]. Efforts to improve integration should aim to understand the perspectives of clinicians in each setting and implement strategies that engage both groups by way of shared communication through direct access to each other, interpersonal relations, shared electronic medical records and clearly defined accountability [ 31 ]. However, organizational and financial splits between these two parts of the health care system impede such collaboration. The lack of a common hierarchy and governance structure necessitates professionals to create combined responsibilities for shared accountability and decision making to deliver integrated care [ 38 ]. There is therefore a need for models and methods that may enhance care delivery suited for patients with complex, long term problems that cut across multiple care providers and settings. Such models should combine the clinical expertise of the specialist and the ability of GPs to bridge the gap between medical and social problems [ 39 ] to allow for continuity of care over time. The development of agreed care pathways has the potential to align clinical, management and service user interests across primary and secondary care [ 40 ] but has been shown to be most effective in contexts where patient care trajectories are predictable [ 41 ]. When pathways are more variable, this is a demanding intervention that requires comprehensive and prolonged efforts by health care professionals in the involved organizations [ 42 ].

We have witnessed many efforts to foster integrated care in the past decade, and this topic has received substantial political interest [ 11 , 27 ]. However, there are few reports on how educational programs for care providers can contribute. A noteworthy exception is Hirsh et al. [ 43 ], who studied how a clerkship model may provide undergraduate students with training relevant for the continuity of care. Concerning the specialist training of GPs, there are few examples of similar discussions. Surveying former research in the area revealed that specialist training is rarely debated, and when it is, the discussion concerns evaluation forms, attendance and curricula. We did find a few examples of case studies in which GPs visited local hospitals for knowledge exchange [ 44 , 45 ]. Such cases have been reported as beneficial for integrated care and mutual learning between GPs and hospital staff, but collaboration lasts a short time, does not involve GPs practising at the hospital and does not demand much involvement between GPs and hospital staff. In response to the challenges described above, the Centre for Obesity Research (ObeCe) at St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital wanted to develop an educational program fostering integrated care. Thus, in 2010, an educational program for the specialization of GPs was established at three regional hospitals in Norway to enhance the exchange of knowledge and strengthen coordination between primary and secondary healthcare providers.

The research question addressed in this paper is thus: what are the main outcomes of the educational program relevant for care delivery to obese patients, as experienced by the participants?

In this study, we investigated how an educational program for GPs in one region in Norway, including one university hospital and two general hospitals, could contribute to enhancing the continuation of care across health care providers. This educational program provides a case study of how educational measures may be designed to promote integrated care. To evaluate the program, understand its potential contribution to integrated care and reveal how it may be improved, a qualitative study [ 46 ] was undertaken. Central documents concerning the establishment and organization of the program were read and analysed, and 13 informants were interviewed. All participants in the program, as well as their closest collaborators at the hospitals and a representative from one municipality, were interviewed.

Research setting

The program was initiated in November 2010 by the management of the Centre for Obesity Research (ObeCe). ObeCe was established in 2005 in line with national and regional health policies [ 47 , 48 ] and is a research and development centre that has carried out several projects to promote collaboration between primary and secondary health care regarding overweight and diabetes. ObeCe does not have patient treatment as its main concern. This allows the unit the freedom and mandate to create new practices like the educational program for GPs [ 49 ]. By June 2014, eight GPs had participated or were currently participating in the project.

The program was designed by ObeCe to provide GPs with relevant training and education for their general practice and to strengthen the connection between primary and secondary care. It was also geared towards providing primary health care providers with competence concerning a grave public health problem, as it focused on subject areas relevant for the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity. The GPs received extensive training with the same patient groups that they meet in their general practice and which they considered challenging. The costs of the educational program were limited to salary expenses for the involved GPs, in addition, they contributed financially to their respective departments by treating patients.

The GPs were employed in educational positions on temporary contracts limited to one-year full time. They had the possibility to work part time, leaving them the opportunity to continue with their own practice. During the program, the GPs participated both in clinical practice and theoretical studies. They were part of multidisciplinary teams at different departments at the hospital. The program was designed to provide the GPs with knowledge and training in four main areas: clinical practices, theoretical studies, research and the development of integrated care. However, the informants emphasized that the balance between these four areas could be adjusted to allow for individual interests and needs. A tutor supported them during the course of the program.

The GPs worked at three different departments to gain clinical practice: the Multidisciplinary Outpatient Clinic for Obesity, the Department of Endocrinology and ObeCE. The multidisciplinary Outpatient Clinic for Obesity is a clinic with health professionals such as surgeons, psychologists, nutritional experts, physiotherapists and endocrinologists that receives children, adults and families, and has a broad perspective on obesity-related issues similar to the perspective of a GP. The GPs did not participate in the rota system, so they had fixed days each week at the different departments: three days at the Department of Endocrinology, one day at the Multidisciplinary Outpatient Clinic for Obesity and one day at ObeCe. They were given their own list of patients to follow for an extended period.

They were involved in patient care at the clinics and in preparing obese patients for operations and for self-management. They also received training in treating patients with type 2 diabetes at the Department of Endocrinology. The GPs evaluated referrals to the hospital from other GPs, conducted physical examinations, reviewed medical histories, provided diagnoses and followed up with tests. These examinations provided the basis to determine the severity of the disease and to create a treatment plan for the patient. They followed patients long enough to observe the effects of the treatments and the patients’ experiences.

The educational program was devised to give the GPs access to theoretical studies and they participated in courses, both initiated by the hospital in general and available at each clinic. Internal courses at the hospital (two hours each week) are required for any specialist under training, but in this program, the GPs also attended lectures at each clinic for one hour each week. In addition, they contributed themselves by holding lectures for the staff at the clinics and at ObeCe. They were also given leeway and encouraged to take initiative in areas they felt they could improve and contribute to.

The GPs had 20% of their time dedicated to research and were encouraged to contribute to the professional development of the field of obesity and overweight. They were expected to update themselves on the latest research results, and as a requirement of the program, the GPs participated in on-going research projects within one month of their employment. The GPs who participated in the program received their formal qualifications as specialists and re-certification in line with the purpose of the program.

Participants

All those involved or related to the program at the time of the study and available for interviews were asked to participate, and all accepted. Those interviewed included five GPs who were enrolled in the program, two nurses, one research assistant, four head physicians and one manager from the local municipality, thereby covering those informants most involved and familiar with the project. Interviews were conducted in two rounds: in April 2012 and in September 2013. The methodological approach was deemed appropriate, as the study was exploratory and aimed to uncover respondents’ experiences and opinions. Each interview lasted from one to two hours. Participation was voluntary.

Data collection and analysis

As a basis for the interviews, a semi-structured guide was developed reflecting the research questions of the study and sent to each informant before the interview (see Additional file 1 , Interview guide). Informants were asked how they experienced the program, in particular about the effects of the program on their own knowledge, expertise and ability to provide quality of care, as well as the results for the various clinics at the hospital and the primary health care services. Informants were also asked whether they saw the program as useful for the particular patient group and society at large, and if so, in what ways. The guide was flexible and allowed the informants to include any new themes they found relevant to describe the program and their experience. All interviews were taped and later transcribed. The data was systematically categorised and coded. The analytical process focused on identifying and differentiating the concepts and topics the informants described, both those introduced by the interview guide and those provided by the informants themselves. Concrete examples of integrated care practices and other examples of results from the program were noted. Similarities and differences between each informant and the informant’s group were coded and compared. The analytical approach was inductive and exploratory, focusing on the concepts and categories as described by the informants.

In interviews, both GPs and their collaborators at the hospital emphasized three main areas they saw as important outcomes of the program: (1) the establishment of relations and networks which breached the organizational divide between primary and secondary care; (2) increased knowledge and competence both at the primary care level and at the hospital; and (3) the development of shared practices and the use of shared standards. In addition, the informants also identified shortcomings, mainly related to the weak integration the GPs experienced with their own municipalities.

Establishing relations and networks

Through the program, GPs and hospital staff became acquainted and formed collaborative relations, both during the time the GPs were at the hospital and after. Since the GPs worked in three different departments at the hospital, they were able to establish relations with several colleagues at the hospital, both doctors and nurses. Both GPs and hospital staff emphasised in interviews the value of the personal relations and networks they had been able to build through the program. One of the GPs stated:

“The most important thing is the increased competence and the network of contacts you get. It becomes so much simpler. And that is a part of the point, that it becomes seamless and that it should work like this” (GP3).

The GPs were encouraged to contribute to areas they felt they could improve and, as a result, they established the first formal arena for knowledge exchange between staff at the ObeCe and the Outpatient Clinic for Obesity so that employees from the two departments can meet at regular intervals for lectures and research updates. This was made possible because the GPs worked fixed days at both departments and were, unlike their colleagues at the hospital, not in the rota system. The rota system affords less individual predictability, as it is not known well in advance which person will occupy which shift. The GPs would know months in advance where they would work each day, so it was easier to plan ahead and take responsibility to schedule activities for knowledge exchange with their hospital colleagues.

The program aided in forming new relations and networks. The GPs emphasised in interviews how this was made possible because they were met by informed and positive colleagues at the hospital. Respect and trust characterised the relations that were established and laid the grounds for open discussions and mutual learning.

Increased knowledge and competence

The program offered several opportunities for training, both through formal courses initiated at the hospital and through the time specified for research. The interviewed GPs explained that they had increased their knowledge of overweight and obese patients, and related diseases such as diabetes, through participating in the program.

According to the informants, the professional environment of the hospital, the time set aside for research and the tutoring they received during the program gave room for investigations that the GPs rarely had time for in their general practice.

The program also provided knowledge and competence that extends beyond those of a formal qualification in overweight and obesity treatment. In an interview, one of the participating GPs explained how the program had changed her attitude towards the patient group and increased her understanding of the complexity of the field of overweight and obesity:

“It is easy to have prejudices concerning this patient group, and there is much stigmatisation. I notice that with colleagues and others who are not familiar with the field. It is easy to conclude, as with other lifestyle related diseases, that it is self-inflicted and weak individuals who are not capable of changing their own situation. It is of course not so simple” (GP1).

The GPs also stated they had an increased sense of confidence in treating obese and overweight patients with related diseases such as diabetes when returning to their medical practices. During their time at the hospital, they were able to see a large number of patients with type 2 diabetes, which increased their confidence in their ability to treat this patient group. Earlier, they would have referred type 2 diabetes patients to secondary health care because they did not feel confident enough to treat them themselves. As explained by GP2:

“My attitude changes while I am here [at the hospital]. I see possibilities for all that can be done in my general practice. Before, I would think that ‘now I have tried with this patient for half a year, and nothing happens, we won’t get any further.’ Now, with new knowledge, I believe there is more we can do” (GP2).

There was a mutual exchange of knowledge between the GPs and medical personnel at the hospital, especially concerning care delivery. A head physician at one of the clinics where the GPs worked said:

“Professionally, it has been very positive for our clinic that they have brought with them the GPs’ views into treatment for diabetes. We are able to discuss what is feasible to do in a general practice, and what we need to continue to do here” (Head Physician).