- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis

Bernd Heine is Emeritus Professor at the Institut für Afrikanistik, University of Cologne. He has held visiting professorships in Europe, Eastern Asia (Japan, Korea, China), Australia, Africa (Kenya, South Africa), North America (University of New Mexico, Dartmouth College), and South America (Brazil). His 33 books include Possesson: Cognitive Sources, Forces, and Grammaticalization (CUP, 1997); Auxiliaries: Cognitive Forces and Grammaticalization (OUP, 1993); Cognitive Foundations of Grammar (OUP, 1997) (with Tania Kuteva); World Lexicon of Grammaticalization (CUP, 2002); Language Contact and Grammatical Change (CUP, 2005); The Changing Languages of Europe (OUP, 2006), and The Evolution of Grammar (OUP, 2007); and with Heiko Narrog as co-editor, The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis (OUP, 2011), and The Oxford Handbook of Grammaticalization (OUP, 2012).

Heiko Narrog is professor at Tohoku University, Japan. He received a PhD in Japanese studies from the Ruhr University Bochum in 1997, and a PhD in language studies from Tokyo University in 2002. His publications include Modality in Japanese and the Layered Structure of Clause (Benjamins, 2009), Modality, Subjectivity, and Semantic Change: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective (OUP, 2012), The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis (OUP, 2010), and The Oxford Handbook of Grammaticalization (OUP, 2011), both co-edited with Bernd Heine.

A newer edition of this book is available.

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This handbook compares the main analytic frameworks and methods of contemporary linguistics It offers an overview of linguistic theory, revealing the common concerns of competing approaches. By showing their current and potential applications, the book provides the means by which linguists and others can judge what are the most useful models for the task in hand. Scholars from all over the world explain the rationale and aims of over thirty explanatory approaches to the description, analysis, and understanding of language. Each chapter considers the main goals of the model; the relation it proposes between lexicon, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and phonology; the way it defines the interaction between cognition and grammar; what it counts as evidence; and how it explains linguistic change and structure.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Welcome to Linguistic Analysis

A peer-reviewed research journal publishing articles in formal phonology, morphology, syntax and semantics. The journal has been in continuous publication since 1976. ISSN: 0098-9053

Please note that Volumes , Issues , Individual Articles , as well as a yearly Unlimited Access Pass (via IP Authentication or Username-and-Password ) to Linguistic Analysis are now available here for purchase and for download on this website. For more information on rates and ordering options, please visit the Rates page. We will continue to add new material so come back to visit. Please Contact us if you are interested in specific back issues.

Current Issue

Linguistic Analysis Volume 43 Issues 1 & 2 (2022)

Barcelona Conference on Syntax, Semantics, & Phonology , edited by Anna Paradis & Lorena Castillo-Ros.

This issue brings together a selection of ten papers presented at the 15th Workshop on Syntax, Semantics, and Phonology (WoSSP), held at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, on June 28-29, 2018. WoSSP is a series of on-going workshops organized by PhD students for students who are working in any domain of generative linguistics, and which offers them a forum to share their work in progress . One of the main aims of the WoSSP conference is to provide a space where graduate students who wish to present their work may exchange ideas within different formal approaches to linguistic phenomena.

Read the Introduction

Issues in Preparation

Volume 43, 3-4: Dependency Grammars

This issue, edited by Timothy Osborne, brings together a selection of papers that examine dependency grammars from a variety of perspectives.

Volume 44, 1-2 Pot-pourri

A selection of orthodox and alternate linguistic perspectives, including an in-depth examination of phonology in classical Arabic poetry, and 3 article-length studies of English grammar by Michael Menaugh.

Note: Volume 43, 3-4, will be the last issue of the journal published in paper. Beginning with volume 44, 1-2, all issues will be available in electronic form only on this website <www.linguisticanalysis.com>. Interested parties will be able to purchase single articles, whole issues, or take advantage of the annual All-Access pass to everything.

Note: We are also uploading all past volumes and issues of the journal and expect this process to be completed by the end of 2023.

Thank you for your patience and continued support.

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Linguistic Analysis

From data to theory.

- Annarita Puglielli and Mara Frascarelli

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: De Gruyter Mouton

- Copyright year: 2011

- Audience: Researchers, Scholars and Advanced Students of Linguistics concerned with Formal Analysis in a Typological, Comparative Perspective

- Front matter: 8

- Main content: 404

- Published: March 29, 2011

- ISBN: 9783110222517

- Published: March 17, 2011

- ISBN: 9783110222500

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

A bibliometric analysis of linguistic research on covid-19.

- 1 Foreign Language Research Department, Beijing Foreign Studies University, Beijing, China

- 2 Center for Linguistics, Literary and Cultural Studies, Sichuan International Studies University, Chongqing, China

Research on COVID-19 has drawn the attention of scholars around the world since the outbreak of the pandemic. Several literature reviews of research topics and themes based on scientometric indicators or bibliometric analyses have already been conducted. However, topics and themes in linguistic-specific research on COVID-19 remain under-studied. With the help of the CiteSpace software, the present study reviewed linguistic research published in SSCI and A&HCI journals to address the identified gap in the literature. The overall performance of the documents was described and document co-citations, keyword co-occurrence, and keyword clusters were visualized via CiteSpace. The main topic areas identified in the reviewed studies ranged from the influences of COVID-19 on language education, and speech-language pathology to crisis communication. The results of the study indicate not only that COVID-19-related linguistic research is topically limited but also that insufficient attention has been accorded by linguistic researchers to Conceptual Metaphor Theory, Critical Discourse Analysis, Pragmatics, and Corpus-based discourse analysis in exploring pandemic discourses and texts.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted human beings in significant ways, and scientists and researchers have actively responded to the challenges in the post-pandemic era by investigating the phenomenon from the vantage point of their research domains. Since 2020, publications about COVID-19 have proliferated across disciplines. The COVID-19 research literature has also increased in bibliometric and scientometric studies (e.g., Chahrour et al., 2020 ; Deng et al., 2020 ; Colavizza et al., 2021 ), as well as systematic reviews and meta-analyses of a variety of COVID-19 pandemic-related topics, such as the risk factors for critical and fatal COVID-19 cases ( Zheng et al., 2020 ) and considerations of whether asthmatic patients are at higher risk of contracting the virus (e.g., Morais-Almeida et al., 2020 ).

In response to the pandemic, linguistic researchers have provided multilingual public communication services or other helpful language services ( Shen, 2020 ; Di Carlo et al., 2022 ). However, at this juncture, a clear need to map the contributions of the linguistic research community to pandemic literature was in evidence. Hence, the present study reviewed the COVID-19-related literature published in SSCI and A&HCI journals on the Web of Science over the past 2 years to address this need. The study used the CiteSpace bibliometric tool to analyze the current state of linguistic research on COVID-19. CiteSpace is a tool for performing a visual analytic examination of the academic literature of a discipline, a research field, or both, referred to as a knowledge domain ( Chen, 2004 , 2006 , 2020 ). A bibliometric analysis is significant for recognizing the expansion of literature in linguistics. It can aid scholars in gaining quantitative insights into the rise of linguistic research on the COVID-19 pandemic, taking into account the social impact of the disease. The findings can identify the frontiers and gaps in the linguistic study on COVID-19 and guide future research.

Previous studies

The COVID-19 pandemic has exercised a disruptive and profound impact on every aspect of human life. Scientific research papers concerning this pandemic have been growing exponentially. We searched publications related to this topic with “COVID” as the topic term in the Web of Science core collection and got 69,591 results 1 . To help researchers assess the research trends and topics on this issue, several literature surveys have already been implemented. Based on scientometric indicators or bibliometric analyses, these reviews include a focus on research patterns from publications on COVID-19 ( Sahoo and Pandey, 2020 ), the most productive countries and the international scientific collaboration ( Belli et al., 2020 ), and the current hotspots for the disease and future directions ( Zyoud and Al-Jabi, 2020 ). The majority of these studies, however, have concentrated on the medical elements of COVID-19, while paying little attention to the research in the social sciences.

In this context, a recent review by Liu et al. (2022) based on a scientometric analysis of the performance of social science research on COVID-19, covering the landscape, research fields, and international collaborations, represents a notable departure from the prevalent focus of earlier studies. Representing a linguistic focus, another recent study by Heras-Pedrosa et al. (2022) consisted of a systemic analysis of publications in health communication and COVID-19. It found that, in 2020, concepts related to mental health, mass communication, misinformation, and communication risk were more frequently used, and in the succeeding year (2021), vaccination, infodemic, risk perception, social distancing, and telemedicine were the most prevalent keywords.

Within the linguistic field, literature reviews tend to focus on COVID-19-related language education exist. For instance, Moorhouse and Kohnke (2021) explore the lessons learned from COVID-19, and identify and analyze the primary knowledge produced by the English-language teaching community during the epidemic, also offering recommendations for further research on this particular subject. A systemic literature review of adult online learning during the pandemic by Lu et al. (2022) compiled and assessed 124 SSCI literature of empirical studies using a systematic literature review and the literature visualization tool CiteSpace. A bibliometric analysis on “E-learning in higher education in COVID-19” by Brika et al. (2022) deployed VOSviewer, CiteSpace, and KnowledgeMatrix Plus to extract networks and bibliometric indicators about keywords, authors, organizations, and countries. The study offered various insights related to higher education. Distance learning, interactive learning, online learning, virtual learning, computer-based learning, digital learning, and blended learning are among the many terms or subfields of e-learning in higher education.

Linguists have made notable contributions to COVID-19 research. However, there is currently no literature review available on the overall state of the field, including topics such as the most active contributors (e.g., countries, institutions, and journals) to research, dominant topic areas in the field, and trends and gaps in linguistic research. To bridge this gap, this study utilized CiteSpace software 6.1 R2 to conduct a systematic review of the present state of linguistic research on COVID-19. Specifically, this study addressed the following questions:

Q1: Which countries, institutions, and journals have contributed the most to the linguistic research on COVID-19?

Q2: What are the active research areas in the linguistic research on COVID-19?

Q3: What are the recent trends and the research gaps in the linguistic research on COVID-19?

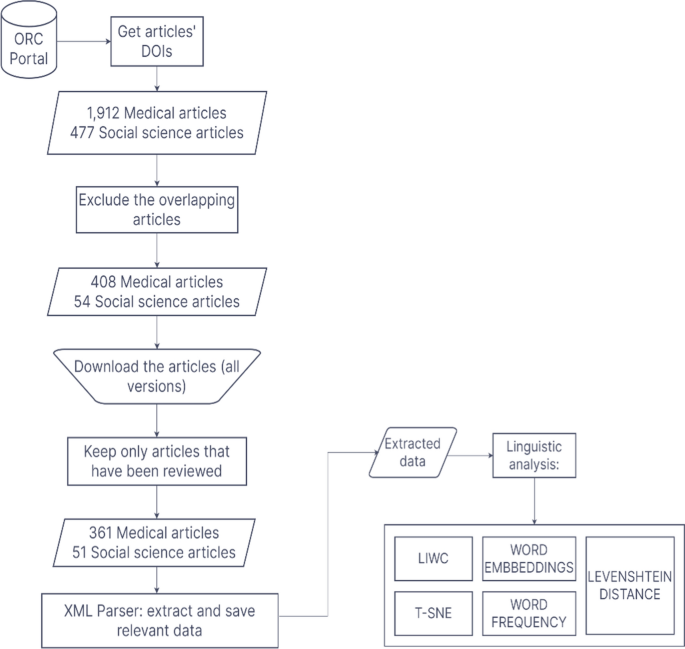

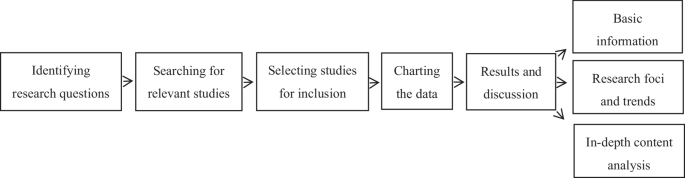

Data collection

As the study was focused on the linguistic field, we searched the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) and Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) available on the Web of Science (WoS) platform. The data were collected through an advanced search. All collected articles/reviews were written in English, and we retrieved the data using the following fields:

1. Topic = (“covid*” OR “*nCoV” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “new coronavirus” OR “coronavirus disease 2019” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2” OR “novel coronavirus” OR “coronavirus 19”). These terms were only allowed in the title, abstract, or keywords.

2. Time span = 2020–2022

3. Document type = article OR review (the review articles do not include book reviews)

4. (“*”) is a wildcard in WOS that represents any group of characters, including no character.

5. Research area = “linguistics”

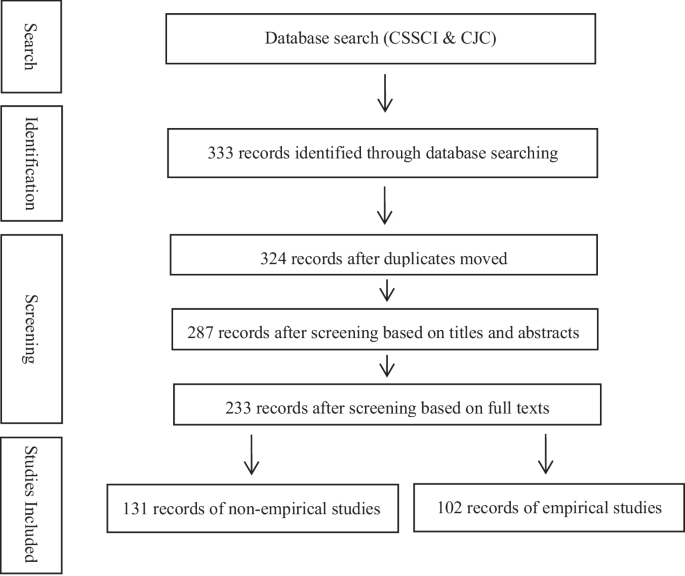

Based on the search items listed above, 363 research and review articles were obtained from the Web of Science Core Collection on 25 May 2022. Through manual analysis, the documents completely unrelated to linguistic research, as well as conference abstracts, book reviews, correspondence, and other unrelated documents were excluded. To guarantee the recall ratio, this study used the “remove duplicates (WOS)” function in CiteSpace to filter out duplicated studies from the collected data. After the cleaning procedure, the final dataset contained 355 documents.

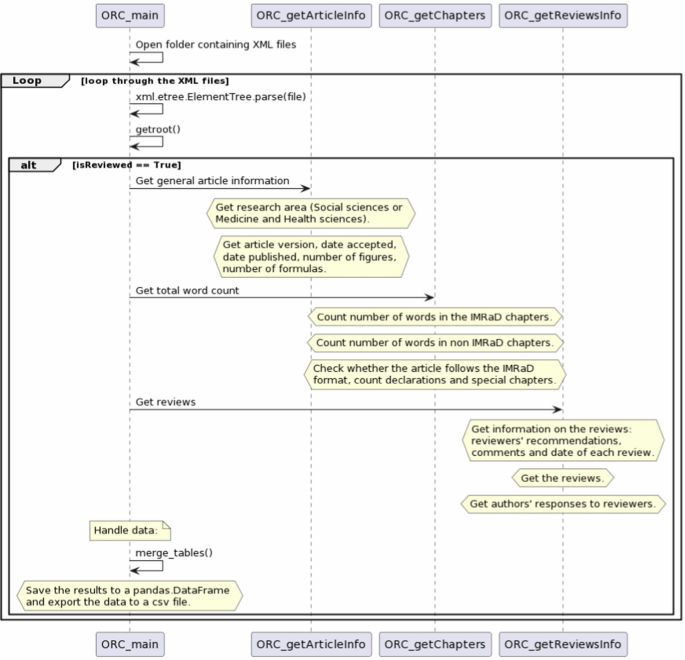

The instrument deployed in this study was CiteSpace 6.1 R2 developed by Chen (2004) as a bibliometric analysis tool ( Chen, 2004 , 2006 , 2017 ; Chen et al., 2010 ). The input in this software is a set of bibliographic data files in the field-tagged Institute for Scientific Information Export Format.

In this study, the files were downloaded from the WoS core collection. We chose “full record and cited references” as the record content and the files can be recognized by CiteSpace software directly. When the files are added to the software, they are subjected to the following procedural steps: time slicing, thresholding, modeling, pruning, merging, and mapping (For more details, please see Chen, 2004 ). The outputs of this software are visualized co-citation networks which is to say that each of the networks is presented in a separate interactive window interface. It can show the evolution of a knowledge field on a citation network, display the overall state of a certain field, and highlight some important documents in the development of a field. The strength of CiteSpace lies in the analysis and visualization of the thematic structures and research hotspots. It can provide us with co-citation networks among references, authors, and countries which is of pivotal importance given the research questions underpinning the present study. Hence, to locate important references, recognize research trends, and pinpoint research hotspots in the linguistic research on COVID-19, co-citation documents and keyword co-occurring analyses were conducted in this study through this software.

Global distribution of articles on COVID-19

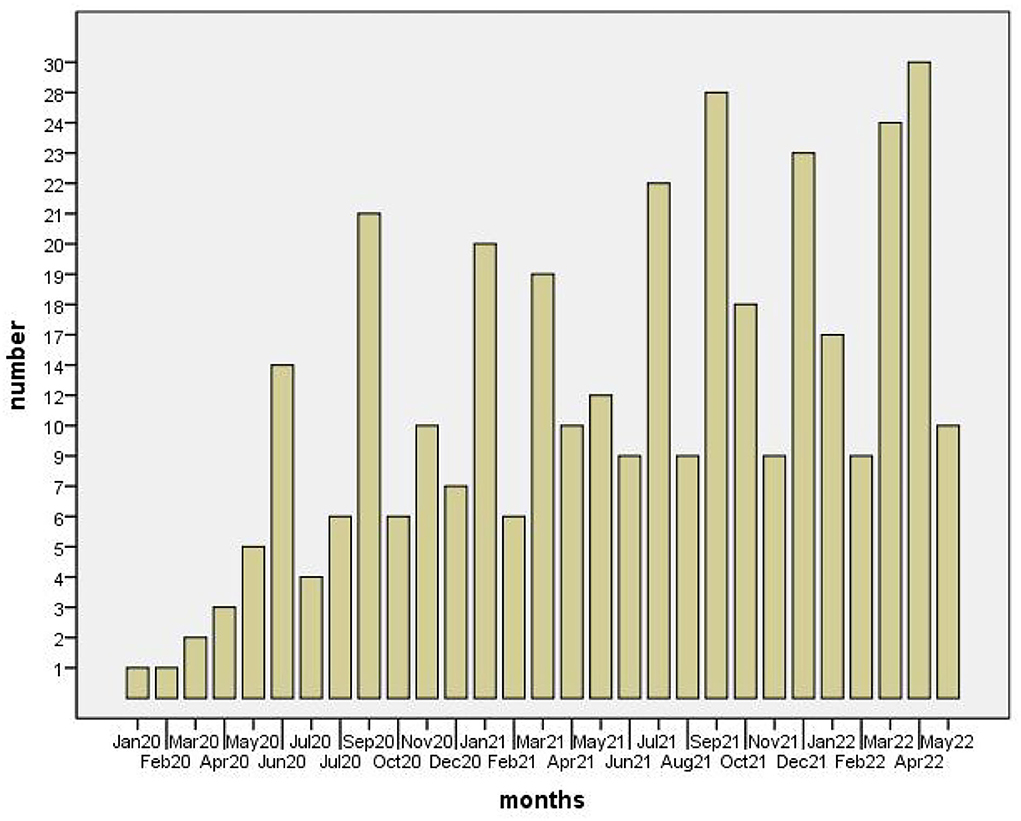

The overall distribution characteristics are presented below. Figure 1 displays the number of papers published each month since January 2020 when the World Health Organization formally declared the epidemic a global public health emergency. There was only one article about COVID-19 published in January 2020, whereas the publications show a peak in April 2022 with 30 publications. Overall, the results show that publications on the topic are increasing every month. Therefore, we might conclude that linguistic researchers have begun to be increasingly interested in COVID-19 linguistic research.

Figure 1 . Number of articles published by month.

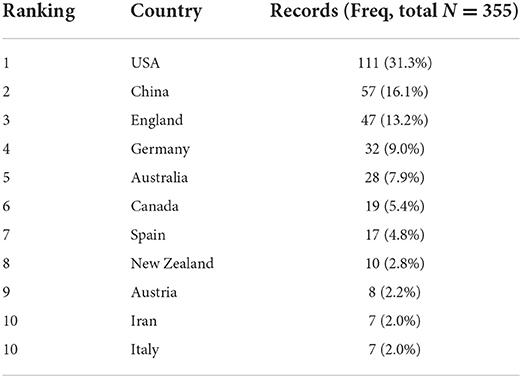

Tables 1 , 2 , respectively, indicate the top 10 most productive countries and institutions for COVID-19 publications. The USA was ranked as the top country in terms of the number of articles related to linguistic publications on COVID-19, with 111 publications in total, followed by China with 57 articles and England with 47 articles ( Table 1 ). In terms of the number of linguistic research publications on COVID-19, Purdue University ranked as the top contributing institution (16 records), followed by the University of London (10 records) and the State University System of Florida (eight publications).

Table 1 . Top 10 most productive countries for COVID-19 linguistic research.

Table 2 . Top 10 most productive institutions for COVID-19 linguistic research.

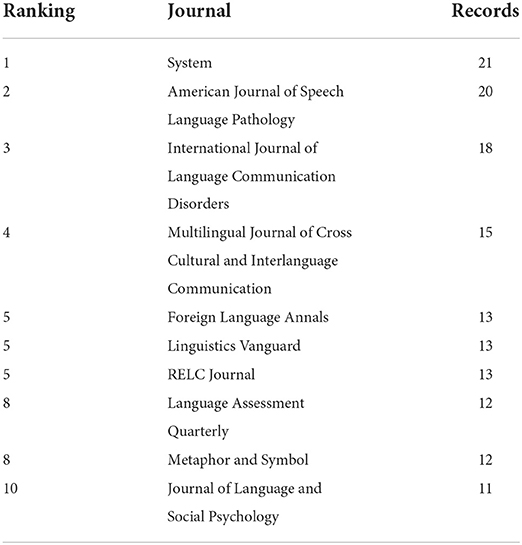

The 355 articles reviewed in the current study were published in 83 journals. The top 10 most productive journals are listed in Table 3 . System ranked the top journal in the number of published articles, with 21 publications related to COVID-19, followed by American Journal of Speech Language Pathology and International Journal of Language Communication Disorders , with 20 and 18 publications, respectively. As we can see in Table 3 , most of the top 10 journals are related to language education or speech-language pathology.

Table 3 . Top 10 most prolific journals.

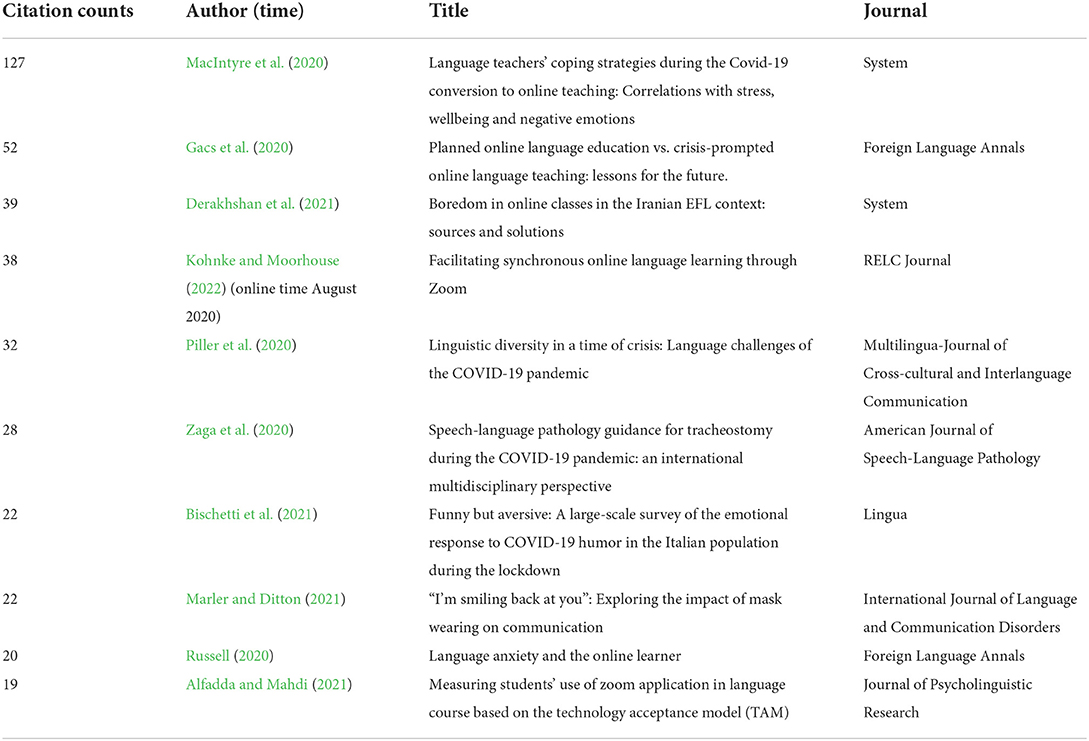

Based on the Global Citation Score in the WoS, the top 10 most-cited articles contributing to COVID-19 research are listed in Table 4 . MacIntyre et al. (2020) ranked as the most-cited article with 127 citations. This article is published in System which is also the most productive journal. The top four articles are all about online language teaching during the COVID-19 period.

Table 4 . Top 10 most-cited articles contributing to COVID-19 linguistic research.

Document co-citation analysis

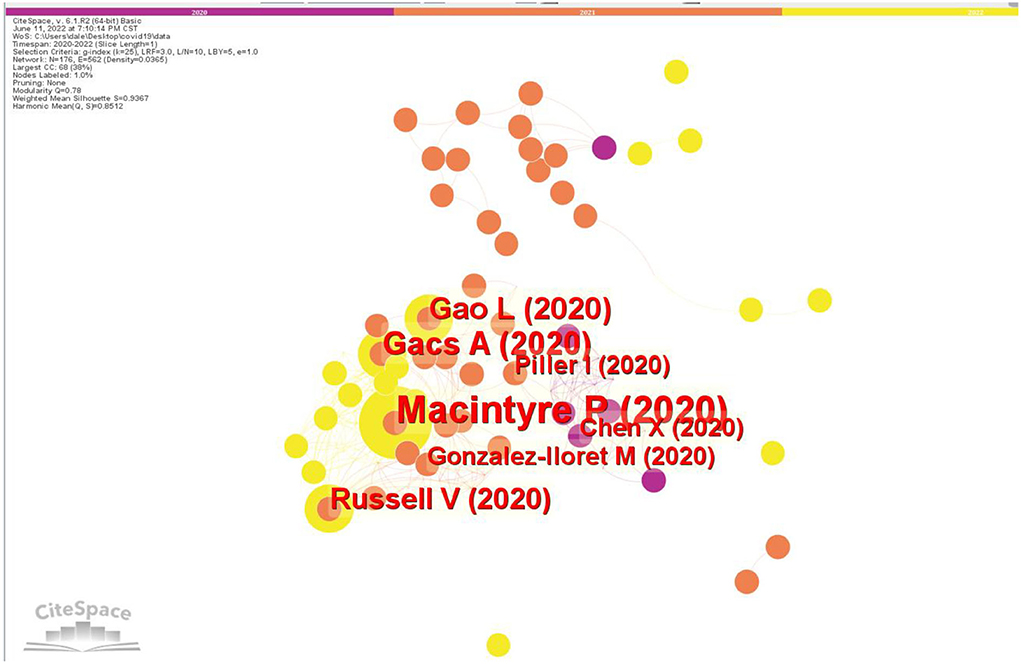

The 355 bibliographic recordings from WoS were visualized and a 1-year time slice was selected for analysis. The size of the node is proportional to the frequency of the cited references. Different colors around nodes represent the frequency of references in different time periods. The labels shown in Figure 2 are all documents with more than three citations, and the connection between nodes shows the co-citation relationship.

Figure 2 . Critical articles in linguistic research on COVID-19.

The top 50 most cited articles every year were selected. There were 176 individual nodes and 562 links, representing cited articles and co-citation relationships among the whole data set, respectively. The results are illustrated in Figure 2 . The results are somewhat different from those obtained from the Global Citation Score in the WoS ( Table 4 ) since the Global Citation Score in the WoS is calculated based on all the citations in WoS, while the document co-citation analysis is based only on the 355 documents retrieved from WoS.

According to the document co-citation analysis, the most co-cited article was written by MacIntyre et al. (2020) . This study explores the issue of language teachers' coping mechanisms and their correlates in the context of the distinctive stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic and the educational responses at the global level. It demonstrates how language teachers have faced a variety of challenges as a result of the global response to the COVID-19 outbreak. High levels of stress have been caused by the quick transition to online education, the blending of job and personal life, and the constant worry about personal and familial wellbeing. With the help of a variety of techniques, teachers were found to be dealing as effectively as they could. Coping strategies that are deemed to be more active and approach-oriented, namely ones that more directly addressed the problems brought on by the phenomenon including the emotions evoked, were found to be connected with more favorable outcomes in terms of psychological health and wellbeing. The greater use of avoidant coping mechanisms was linked to worse psychological outcomes. Increased use of avoidant coping, in particular, was linked to higher stress levels and a range of unpleasant feelings (anxiety, anger, sadness, and loneliness). MacIntyre et al. (2020) also found that a variety of particular techniques were employed by the participants within the approach and avoidant categories of coping, and the majority of them produced outcomes consistent with the category in which they appeared. The multidimensional nature of the stressors required multidimensional coping strategies, but it was obvious that some coping strategies were superior to others. This study by MacIntyre et al. (2020) offers insights into the effectiveness of coping strategies used by language teachers during the crisis and their implications for other stressful events and processes such as school transfers, educational reform, or demanding work periods like the end-of-year exam. MacIntyre et al. (2020) suggest that all pre-service and in-service teacher education programs should incorporate stress management as a fundamental professional competence.

The second most cited article is written by Gacs et al. (2020) , which compares the crisis-prompted online language teaching during the COVID-19 era with well-designed and carefully planned online language education. Due to the 2020 pandemic, many institutions were forced to transition away from face-to-face (F2F) teaching to online instruction. The crisis-prompted online language teaching is different from actual planned online language education. This is because in times of pandemic, war, crisis, natural disaster, or extreme weather, neither teachers nor students are prepared for switching over to online education without good technology literacy, access, and infrastructure. Gacs et al. (2020) describe the process of preparing, designing, implementing, and evaluating online language education when adequate time is available and the concessions one has to make as well when adequate time is not a possibility in times of pandemic or in other emergent conditions. This article presents a roadmap for planning, implementing, and evaluating online education in an ideal and crisis contexts.

The third most cited article conducted by Gao and Zhang (2020) set up a qualitative inquiry to investigate how EFL teachers perceive online instruction in light of their disrupted lesson plans and how EFL teachers teach during the early-stage COVID-19 outbreak developed their information technology literacy. The findings from this study on teachers' perceptions of online instruction during COVID-19 have theoretical ramifications for studies on both teachers' cognitions and online EFL teaching.

It is evident that the three top-cited articles are on the theme of language education. Therefore, it can be concluded that remote online education during a pandemic crisis is the most studied area from the linguistic perspective.

Keyword co-occurrence

In a way, keywords serve as the central summary of articles and serve to convey their major idea and subject matter. The co-occurrence of keywords in an article indicates the degree of closeness between the keywords and the strength of this relationship. According to common perception, the more strongly related two or more terms are, the more often they are likely to appear together. CiteSpace provides a function called Betweenness Centrality to describe the strength. In other words, if a keyword consistently appears alongside other distinct keywords, it is likely that we will see it even if we talk about other related subjects. As a result, the greater the value of Betweenness Centrality a keyword displays, the more significant a keyword is.

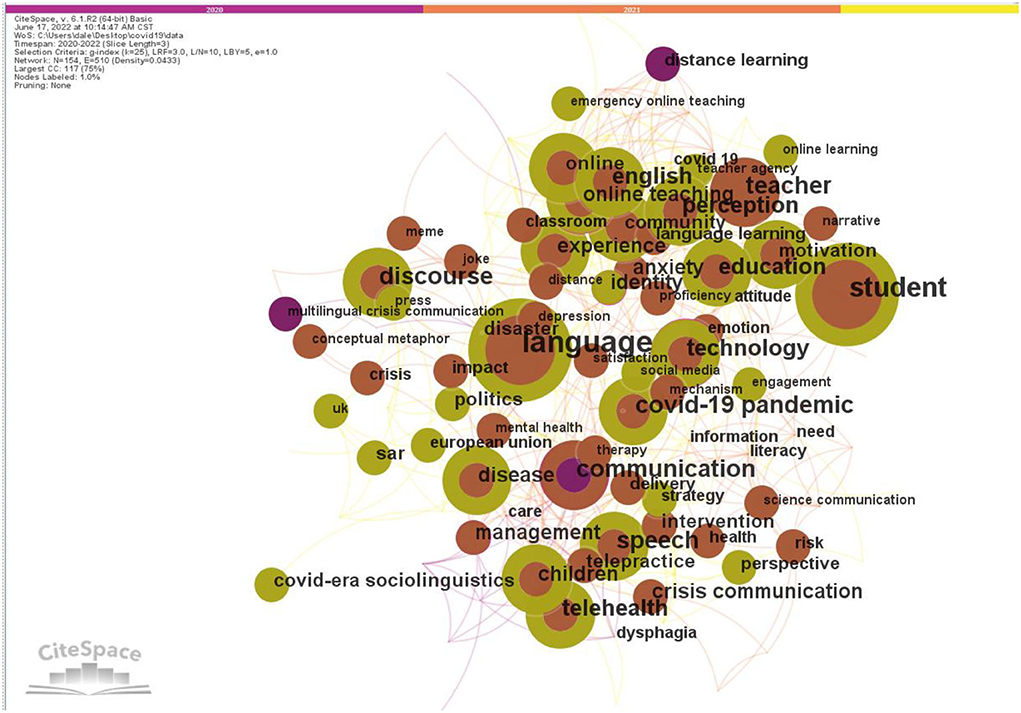

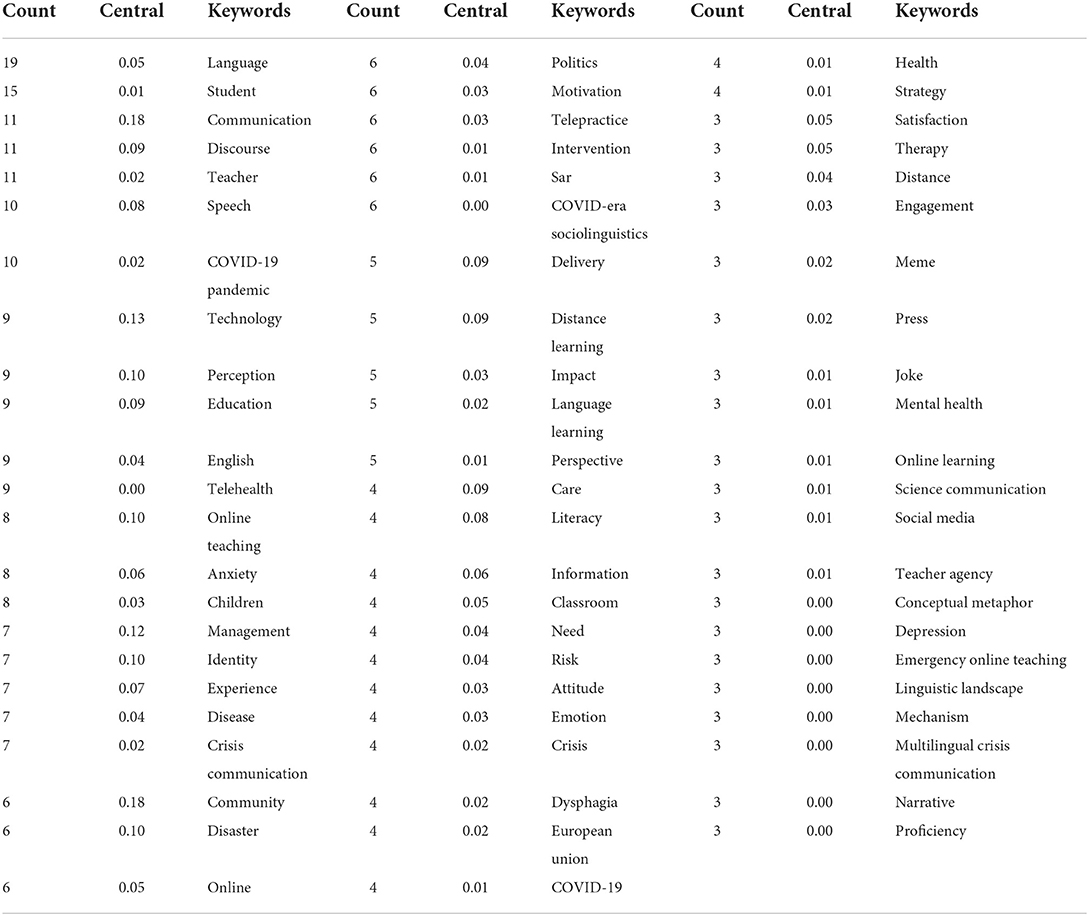

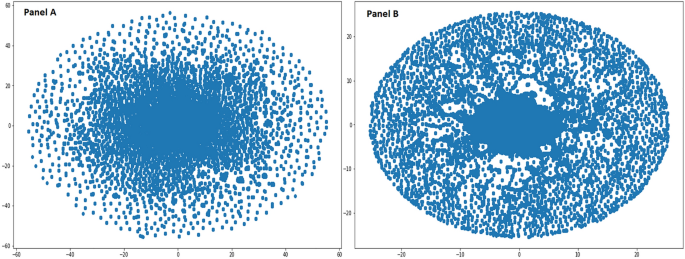

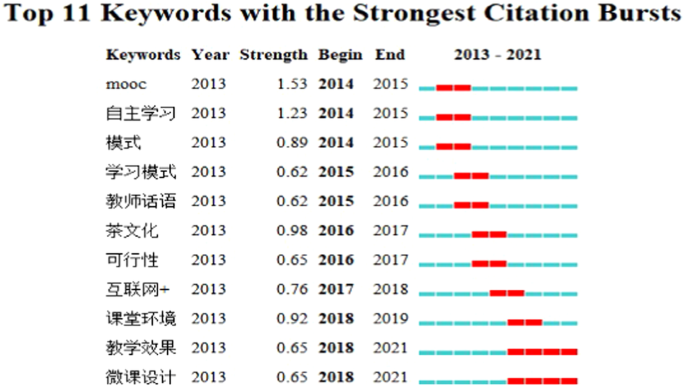

A keyword co-occurrence analysis was conducted in this study to identify the research fields and dominant topics. A term analysis of words extracted from keywords was conducted to identify the words or phrases co-occurring in at least two distinct articles. Terms with high frequency may be treated as indicators of hotspots in a certain research field ( Chen, 2004 ). The top five high-frequency keywords were language, student, communication, discourse, and teacher. The keyword co-occurrence network is shown in Figure 3 , and the keywords with frequencies of more than three are displayed in Table 5 .

Figure 3 . Keyword co-occurrence network for documents of linguistic research on COVID-19.

Table 5 . The co-occurring keywords with high frequency.

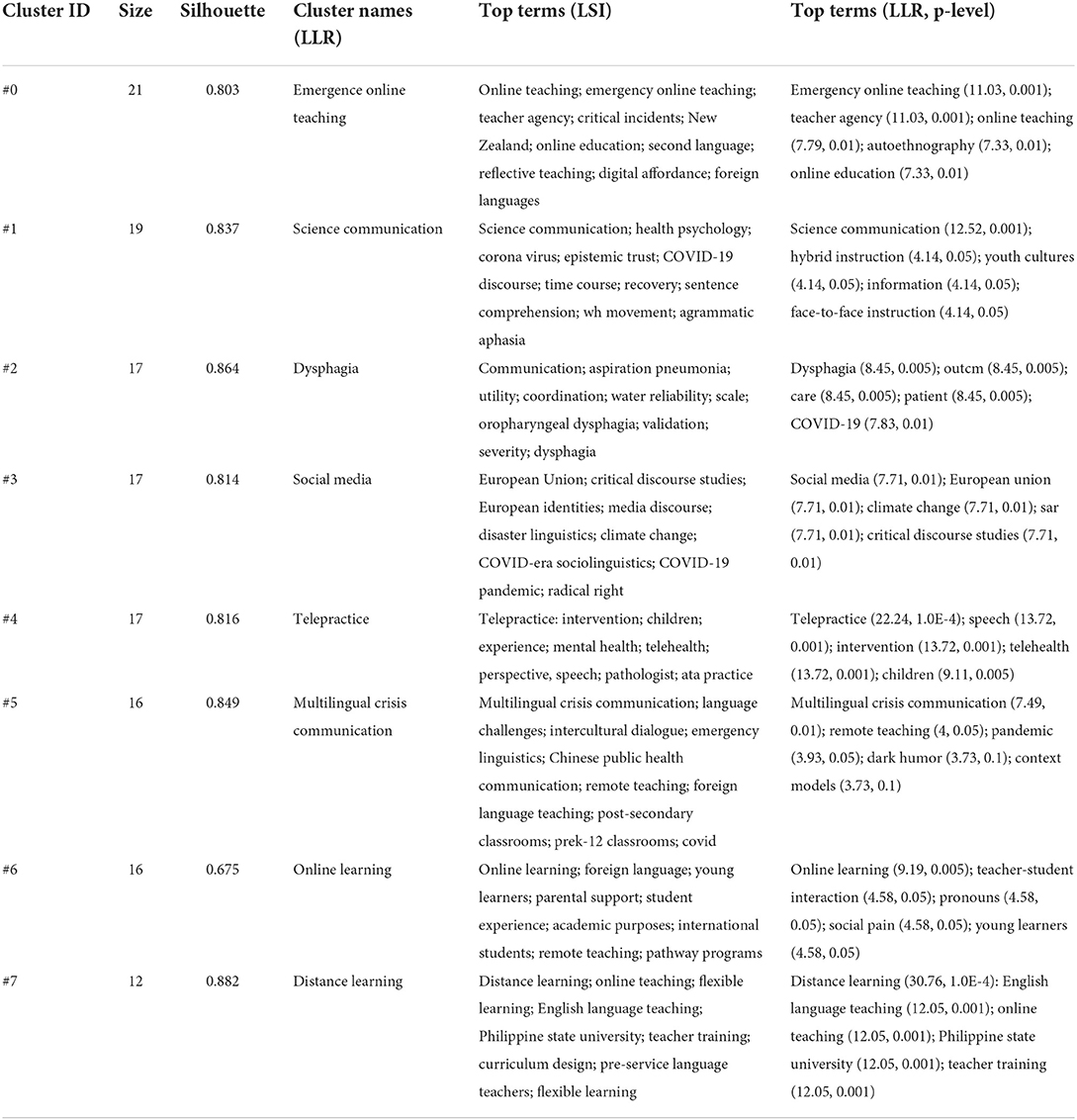

Cluster interpretations

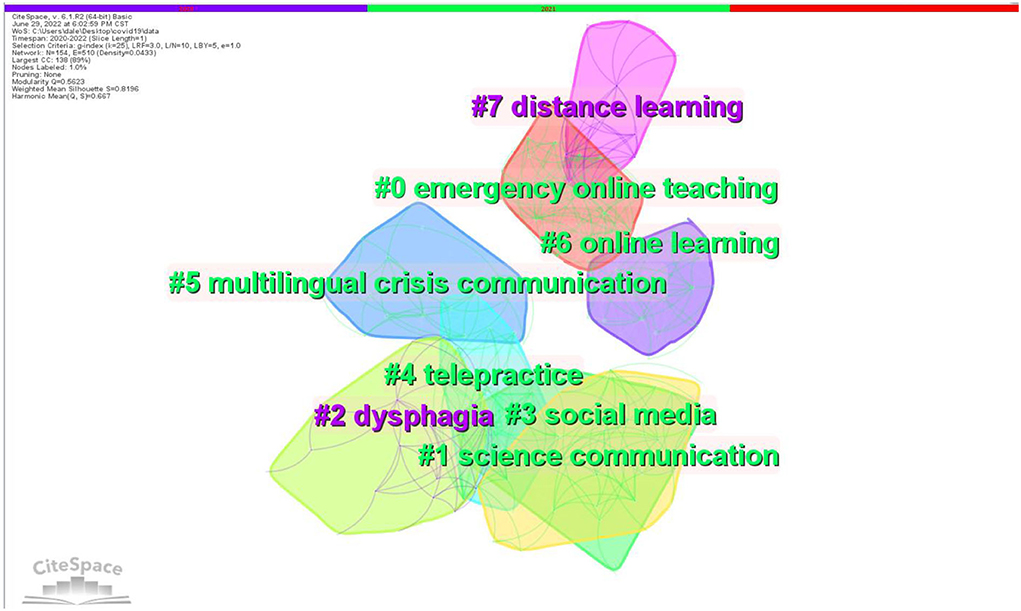

Based on the analysis of the results of keyword co-occurrence, we used CiteSpace to conduct a cluster analysis. The 355 articles generated 20 clusters in total. Labeling clusters with indexing terms and showing clusters by log-likelihood ratio (LLR), Figure 4 shows the eight most important keyword clusters obtained by keyword co-occurrence analysis. Table 6 shows the keywords lists of the seven important clusters in linguistic research on COVID-19. It illustrates an aggregated distribution in which the most colorful areas overlapped, indicating that these clusters share some basic concepts or information (as suggested by Chen, 2004 ).

Figure 4 . Cluster view of keyword co-occurrence.

Table 6 . Important clusters of keywords in linguistic research on COVID-19.

Cluster #0 is labeled as emergence online teaching

Cluster #6 (online learning) and Cluster #7 (distance learning) are closely related to Cluster #0 since both Cluster #6 (online learning) and Cluster #7 (distance learning) fall under the umbrella of online education during a crisis. Emergency online teaching and online/distance learning are clearly shown to be the focus of linguistic research related to COVID-19.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, teaching and learning experienced a shift from physical, in-person (or face-to-face) learning environments to virtual, online learning environments. Although online education is well-established, pandemic-initiated online teaching and learning differed from traditional, well-planned online teaching, thus leading to significant difficulties for both language teachers and students. The stakeholders had to quickly adapt to new environments and learning styles while dealing with the pandemic's personal and societal repercussions on their everyday lives and wellbeing ( MacIntyre et al., 2020 ). The online teaching of foreign and second languages during COVID-19 is referred to as emergency remote teaching (ERT), a term used to describe education temporarily moved online due to unforeseeable events such as natural catastrophes or conflict ( Hodges et al., 2020 ). The difficulties primary school ESOL teachers in the United States encountered as a result of the unexpected instructional adjustments brought on by the COVID-19 epidemic are described by Wong et al. (2022) along with how these difficulties appeared to have impacted the teachers' wellbeing.

There are problems unique to language education, even if English language teachers and students have faced many of the same difficulties as their peers in other disciplines. For instance, many people view the interaction between students and teachers as a crucial component of language acquisition ( Walsh, 2013 ), whereas interaction works very differently in the online mode ( Payne, 2020 ). Therefore, to encourage and support engagement during online language lessons, teachers need to showcase certain competencies ( Cheung, 2021 ; Moorhouse et al., 2021 ).

Understandably, the research community has developed a keen interest on how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected language teaching and learning. More attention is directed toward adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic-initiated online education due to the rapid and abrupt switch from classroom instruction to online learning. For instance, how the students—especially primary pupils—and the teachers adapt to online teaching is the main topic discussed in a special issue of System (2022, volume 105). The COVID-19 pandemic also changed the in-person and on-campus testing into placement testing. Ockey (2021) provides an overview of COVID-19's impact on English language university admissions and placement tests.

Cluster #1 is labeled as science communication

During the COVID-19 pandemic period, it has become very crucial for scientists and government politicians to communicate scientific knowledge to the public to limit the spread of COVID-19. Linguistic factors can play an important role in science communication. A study by Schnepf et al. (2021) inquired into whether complex (vs. simple) scientific statements on mask-wearing could lead audiences to distrust the information and its sources, thus obstructing compliance with behavioral measures communicated on evidence-based recommendations. The study found that text complexity affected audiences inclined toward conspiracy theories negatively. Schnepf et al. (2021) provided recommendations for persuading audiences with a high conspiracy mentality, a group known to be mistrustful of scientific evidence. Janssen et al. (2021) inquired into how the use of lexical hedges (LHs) impacted the trustworthiness ratings of communicators endeavoring to convey the efficacy of mandatory mask-wearing. The study found that scientists were perceived as being more competent and having greater integrity than politicians.

Cluster #2 is labeled as dysphagia

When a society faces a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of COVID-19 on special needs populations, such as people with dysphagia or aphasia or hearing impairments ( Cheng and Cheng, 2022 ; Mathews et al., 2022 ), assumes greater importance for the linguistic community. A study by Jayes et al. (2022) described how UK Speech and language therapists (SLTs) supported differently abled individuals with communication disabilities to make decisions and participate in mental capacity assessments, best interest decision-making, and advance care planning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Govender et al. (2021) investigated how people with a total laryngectomy (PTL) were impacted by COVID-19. Feldhege et al. (2021) conducted an observational study on changes in language style and topics in an online Eating Disorder Community at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Owing to the severity of the pandemic, speech-language pathologists (SLPs) shifted quickly to virtual speech-language services. Thus, telepractice (cluster #4) also becomes one of the important keyword clusters. Telepractice has been used extensively to offer services to people with communication disorders since the global COVID-19 pandemic. Due to physical separation tactics used to contain the COVID-19 outbreak, many SLPs implemented a live, synchronous online distribution of clinical services. However, SLPs have received synchronous telepractice training to equip them for the shift from an in-person service delivery approach. Using synchronous modes of online clinical practice, Knickerbocker et al. (2021) provide an overview of potential causes of phonogenic voice issues among SLPs in telepractice and suggest prospective preventative techniques to maintain ideal vocal health and function.

Cluster #3 is labeled as social media and it is closely related to Cluster #5 (multilingual crisis communication) since social media research is a way to analyze public communication, particularly during a health crisis. Given the physical restrictions during COVID-19, social media platforms enabled individuals to maintain contact and share ideas. Many studies have investigated the performances of various types of social media platforms during the pandemic, such as Twitter ( Weidner et al., 2021 ), Weibo ( Ho, 2022 ; Yao and Bik Ngai, 2022 ), WhatsApp ( Pérez-Sabater, 2021 ), and YouTube ( Breazu and Machin, 2022 ). Weidner et al. (2021) looked at the characteristics of tweets concerning telepractice via the prism of a well-known framework for using health technology. During the epidemic, there was a surge in telepractice-related tweets. Although several tweets covered ground that is expected in the application of technology, some covered ground that might be particular to speech-language pathology. Yao and Bik Ngai (2022) investigated how People's Daily communicated COVID-19 messages on Weibo. Its findings contribute to the understanding of how public engagement on social media can be augmented via the use of attitudinal messages in health emergencies. Cluster #5 multilingual crisis communication is mostly studied from the perspective of sociolinguistics. Contributing to the sociolinguistics of crisis communication, Ahmad and Hillman (2021) examined the communication strategies employed by Qatar's government in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. While a study by Gallardo-Pauls (2021) proposed a specifically linguistic/discursive model of risk communication, Tu et al. (2021) inquired into how pronouns “we” and “you” affected the likelihood to stay at home differently. In another study, Tian et al. (2021) investigated the role of pronouns in crafting supportive messages and hope appeals and facilitating people to cope with COVID-19.

When a society is faced with a crisis, its language can reflect, reveal, and reinforce societal anarchy and divides. A study by Nagar (2021) examined how minority groups—Muslims and migrant workers—experienced marginalization, oppression, and damage through linguistic mechanisms such as silence, presuppositions, accommodations, othering, dog-whistling, and poverty.

Implications for future study

As a discipline, linguistics has contributed significantly to the literature on COVID-19. Based on the results obtained from the above descriptive statistics and visualizations via Citespace, the study found that linguistic research on COVID-19 hitherto has largely focused on the influences of COVID-19 on language education, speech-language pathology, and crisis communication. Language education is one particular strand of applied linguistics, while speech-language pathology and crisis communication, respectively, comprise interdisciplinary studies of language and pathology, and language and communication.

The present state of linguistic research on COVID-19 reveals that there is a dearth of studies deploying linguistic theories such as Conceptual Metaphor Theory, Critical Discourse Analysis, Pragmatics, and Corpus-based discourse analysis. These theories can serve as important heuristics for exploring COVID-19 discourses. A strand of research from the perspective of these theories has highlighted the problematic nature of COVID-19 discourses.

Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, linguists were concerned about the language regarding COVID-19. The Conceptual Metaphor Theory ( Lakoff and Johnson, 1980 ), as one of the primary theoretical constructs in Cognitive Linguistics, was employed by some scholars to explore the COVID-19 discourse. Through their analysis of the conceptual metaphors in different kinds of COVID-19 discourse, linguistic scholars found that the WAR metaphor dominated the COVID-19 discourse ( Bates, 2020 ; Chapman and Miller, 2020 ; Isaacs and Priesz, 2021 ). However, other metaphors such as FIRE remained underexplored concerning the pandemic ( Semino, 2021 ). Although a study by Abdel-Raheem (2021) has explored the multimodal COVID-19 metaphor by examining political cartoons, in general, the multimodal COVID-19 metaphor has not been studied extensively. Further, despite the fact that Preux and Blanco (2021) experimental study explored the influence of the WAR and SPORT domains on emotions and thoughts during the COVID-19 era, the impact of the COVID-19 metaphor on the emotions and mental health of the public has received limited attention.

Critical Discourse Analysis has been deployed by some linguistic researchers. For example, critical discourse analysis was used by Zhang et al. (2021) to compare the reports on COVID-19 and social responsibility expressions in Chinese and American media sources. Based on a case study of U.S. regulations on travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, Li and Gong (2022) use proximization theory to demonstrate how proximization helps to legitimize health emergency measures. By using a multi-level content analysis technique based on theories of proximization and representation of distant suffering, Florea and Woelfel (2022) investigated the news portrayal of COVID-19 during the year 2020 as proximal vs. remote discourses of suffering. Forchtner and Özvatan, 2022 take a step toward the conceptual integration of narrative (genre) into the Discourse-Historical Approach in Critical Discourse Studies. Their study illuminated the far-right populist Alternative for Germany's (AfD) performances of delegitimization of itself/the nation in relation to Europe and legitimization of itself/the nation by articulating two paradigmatic, transnational crises: climate change and COVID-19. Szabó and Szabó (2022 ) used the discourse dynamics approach to identify the metaphorical terms employed by the Prime Minister to legitimize the crisis management of the Hungarian government and delegitimize critical commentary external to the European Union.

Drawing on critical discourse analysis and textual analysis, Zhou (2021) conducted an interdisciplinary study of the semiotic work dedicated to legitimating Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) treatment of COVID-19 in the social media account of an official TCM institution. While CDA analysis of COVID-19 discourses has been undertaken, more CDA-led studies need to be undertaken, given the complexity of power and inequities interwoven reflected in the texts and discourses pertaining to the pandemic.

Pragmatics research on COVID-19 is another underexplored area. Ogiermann and Bella (2021) analyze signs displayed on the doors of closed businesses in Athens and London during the first lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic, providing some new insights into the dual function of expressive speech acts discussed in pragmatic theory. Blitvich (2022) explores the connections between face-threat and identity construction in the on/off line nexus by focusing on a stigmatized social identity ( Goffman, 1963 ), a local ethnographically specific, cultural position ( Bucholtz and Hall, 2005 ) attributed to some American women stereotypically middle-aged and white who are positioned by others as Karens. Thus, a woman who is perceived to be acting inappropriately, harshly, or in an entitled manner is categorized as a Karen . This incorrect behavior is frequently connected to alleged acts of racism toward minorities. The anti-masker Karens also achieved attention during the COVID-19 pandemic. This research offers a multimodal analysis of a sizable corpus, 256 films of persons whose actions and the way they were seen caused them to be positioned as Karens , to advance our knowledge of the Karen identity. More theories of Pragmatics, such as Relevance Theory, can be employed in the study of COVID-19 discourse.

Corpus-based COVID-19 discourse analysis is also deserving of research attention. Mark Davies has built the Coronavirus Corpus ( https://www.english-corpora.org/corona/ )—an online collection of news articles in English from around the world from January 2020 onwards. The corpus, which was first released in May 2020, currently has about 1,500 million words in size at the cutoff point (16 May 2022), and it continues to grow by three to four million words each day. It can provide vast original discourse data for researchers. For example, based on a 12.3-million-word corpus, Jiang and Hyland (2022) explore keyword nouns and verbs, and frequent noun phrases to understand the central concerns of the public reflected in its news media. In future, more research can be conducted based on the Coronavirus Corpus.

Human life has been greatly affected and disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientists and researchers have actively responded to this pandemic by investigating the phenomenon of COVID-19 from the lens offered by their fields of research, and publications relevant to COVID-19 have proliferated rapidly across disciplines since the beginning of 2020. To investigate contributions made by linguistic researchers to pandemic research, the current study carried out a bibliometric analysis of the relevant and available literature. Three hundred and fifty-five bibliometric recordings ranging from January 2020 to May 2022 were collected from WoS, and CiteSpace software was adopted to quantitatively and visually review these papers. The study found that there was continued growth in publications between January 2020 to May 2022. USA was found to be the most productive country in terms of contributions to literature contributing 111 publications pertaining to COVID-19, whereas System ranked as the top journal in the number of published articles related to COVID-19 (21 publications). Through the visualizations of keyword co-occurring analysis and cluster interpretation via Citespace, the study also found that linguistic research on COVID-19 focused largely on the influences of COVID-19 on language education, speech-language pathology, and crisis communication. However, the present review flags the need for more investigations of COVID-19 texts and discourses deploying the explanatory lens of key linguistics theories such as Conceptual Metaphor Theory, Critical Discourse Analysis, Pragmatics, and Corpus-based Discourse Analysis.

Although within its delineated scope, the present study aspired to be as comprehensive as possible, some limitations were unavoidable. For instance, the study searched documents in the Web of Science alone, not including other data sources such as Scopus, Google Scholar, Index Medicus, or Microsoft Academic Search. Further, only one scientometric tool was employed in this review. Future research may make use of a larger database and different analytical tools.

Nonetheless, this study comprises a pioneering review of linguistic research on COVID-19 and identifies and provides a clear overview of international linguistic research in relation to COVID-19. Hence, it can be used as a useful springboard by linguistic researchers interested in probing COVID-19 discourses and texts through the lens of leading theories in the field, thus not only expanding the topical breadth of linguistic research on the pandemic but also generating valuable insights in areas of pragmatics and metaphor as well as CDA and corpus research. These insights are likely to have theoretical as well as practical implications for the field of linguistics.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This study was funded by the National Social Science Foundation Project (Award Number: 20XYY001, PI: ZH).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ The search date is 15/05/2022.

Abdel-Raheem, A. (2021). Where Covid metaphors come from: reconsidering context and modality in metaphor. Social Semiotics. 1–40. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2021.1971493. [Epub ahead of print].

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ahmad, R., and Hillman, S. (2021). Laboring to communicate: use of migrant languages in COVID-19 awareness campaign in Qatar. Multilingua. 40, 303–337. doi: 10.1515/multi-2020-0119

Alfadda, H., and Mahdi, H. (2021). Measuring students' use of zoom application in language course based on the technology acceptance model (TAM). J. Psycholinguistic Res. 50, 883–900. doi: 10.1007/s10936-020-09752-1

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bates, B. R. (2020). The (in)appropriateness of the WAR metaphor in response to SARS-CoV-2: A rapid analysis of Donald J. Trump's rhetoric. Front. Communicat. 5, 1–12. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.00050

CrossRef Full Text

Belli, S., Mugnaini, R., Balt,à, J., and Abadal, E. (2020). Coronavirus mapping in scientifc publications: when science advances rapidly and collectively, is access to this knowledge open to society? Scientometrics. 124, 2661–2685. doi: 10.1007/s11192-020-03590-7

Bischetti, L., Canal, P., and Bambini, V. (2021). Funny but aversive: a large-scale survey of the emotional response to Covid-19 humor in the Italian population during the lockdown. Lingua. 249, 102963. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2020.102963

Blitvich, P. (2022). Karen: Stigmatized social identity and face-threat in the on/offline nexus. J. Pragmat. 188, 14–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2021.11.012

Breazu, P., and Machin, D. (2022). Racism is not just hate speech: ethnonationalist victimhood in YouTube comments about the Roma during Covid-19. Lang. Society . 1–21. doi: 10.1017/S0047404522000070

Brika, S. K. M., Chergui, K., Algamdi, A., Musa., A. A, and Zouaghi, R. (2022). E-Learning research trends in higher education in light of COVID-19: a bibliometric analysis. Front. Psychol. 12, 762819. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.762819

Bucholtz, M., and Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: a sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Stud . 7, 585e614 doi: 10.1177/1461445605054407

Chahrour, M., Assi, S., Bejjani, M., Nasrallah, A. A., Salhab, H., and Fares, M. (2020). A bibliometric analysis of COVID-19 research activity: a call for increased output. Cureus. 12, e7357. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7357

Chapman, C. M., and Miller, D. S. (2020). From metaphor to militarized response: the social implications of “we are at war with COVID-19” – crisis, disasters, and pandemics yet to come. Int. J. Sociol. Social Policy. 40, 1107–1124. doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-05-2020-0163

Chen, C. (2004). Searching for intellectual turning points: progressive knowledge domain visualization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101, 5303–5310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307513100

Chen, C. (2006). CiteSpace II: detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 57, 359–377. doi: 10.1002/asi.20317

Chen, C. (2017). Science mapping: a systematic review of the literature. J. Data Inf Sci. 2, 1–40. doi: 10.1515/jdis-2017-0006

Chen, C. (2020). A Glimpse of the first eight months of the COVID-19 literature on microsoft academic graph: themes, citation contexts, and uncertainties. Front. Res. Metr. Anal . 5, 607286. doi: 10.3389/frma.2020.607286

Chen, C., Ibekwe-San Juan, F., and Hou, J. (2010). The structure and dynamics of cocitation clusters: a multiple-perspective cocitation analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 61, 1386–1409. doi: 10.1002/asi.21309

Cheng, S. Y., and Cheng, S. L. (2022). Parents' psychological stress and their views of school success for deaf or hard-of-hearing children during COVID-19. Communicat. Dis. Q . 1–9. doi: 10.1177/15257401221078788

Cheung, A. (2021). Synchronous online teaching, a blessing or a curse? Insights from EFL primary students'interaction during online English lessons. System. 100, 102566. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102566

Colavizza, G., Costas, R., Traag, V. A., Eck, N. J., Leeuwen, T., and Waltman, L. (2021). A scientometric overview of CORD-19. PLoS ONE. 16, e0244839. doi: 10.1371./journal.pone.0244839

Deng, Z., Chen, J., and Wang, T. (2020). Bibliometric and visualization analysis of human coronaviruses: prospects and implications for COVID-19 research. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol . 10, 581404. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.581404

Derakhshan, A., Kruk, K., Mehdizadeh, M., and Pawlak, M. (2021). Boredom in online classes in the Iranian EFL context: sources and solutions. System. 101, 102556. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102556

Di Carlo, P., Lukschy, L., Rey, S., and Vita, V. (2022). Documentary linguists and risk communication: views from the virALLanguages project experience. Linguistics Vanguard . doi: 10.1515/lingvan-2021-0021

Feldhege, J., Moessner, M., Wolf, M., and Bauer, S. (2021). Changes in language style and topics in an online eating disorder community at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic: observational study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e28346. doi: 10.2196/28346

Florea, S., and Woelfel, J. (2022). Proximal versus distant suffering in TV news discourses on COVID-19 pandemic. Text and Talk. 42, 327–345. doi: 10.1515/text-2020-0083