Essay on Elephant for Students and Children

500+ words essay on elephant.

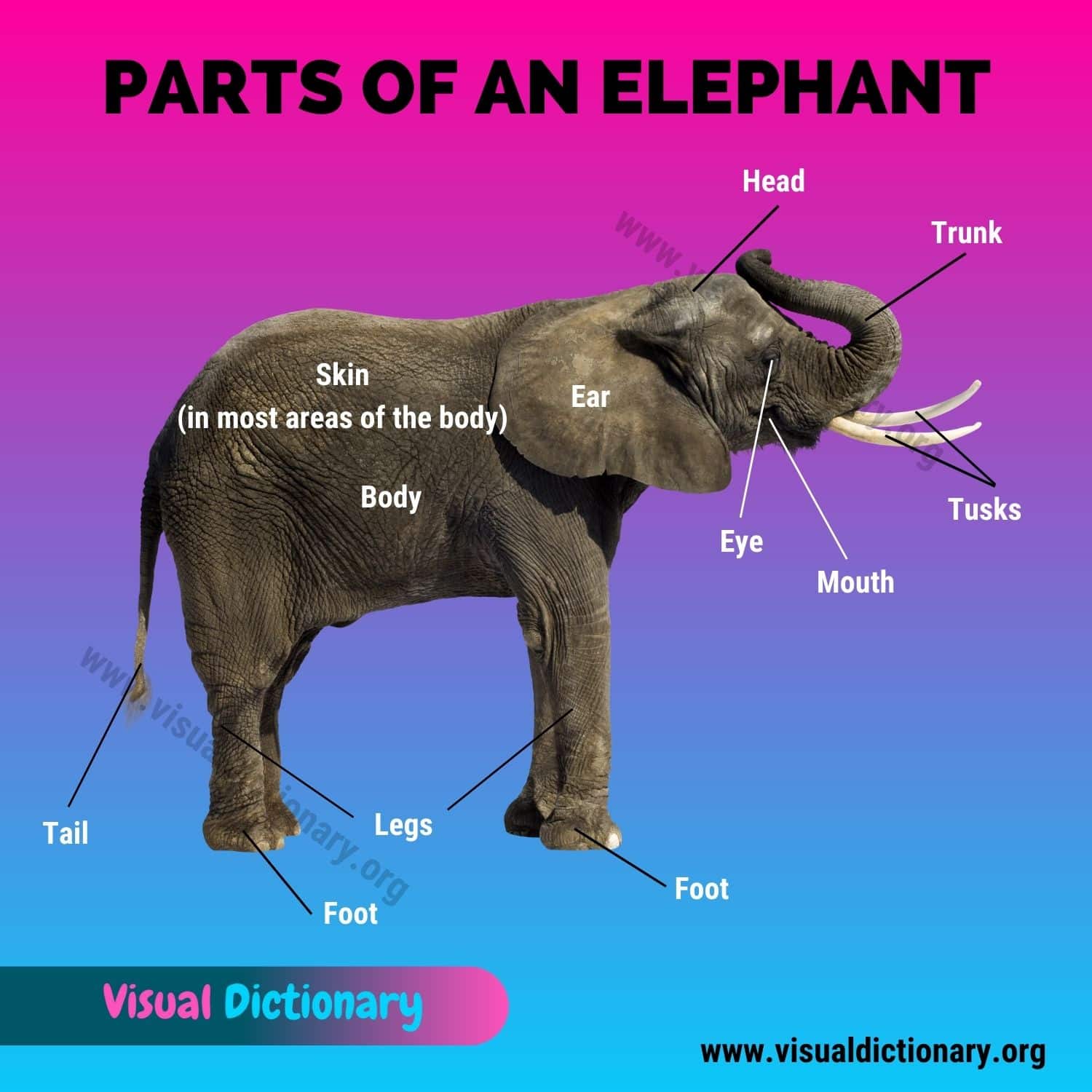

Elephants are quite large animals . They have four legs which resemble large pillars. They have two ears which are like big fans. Elephants have a special body part which is their trunk. In addition, they have a short tail. The male elephant has two teeth which are quite long and are referred to as tusks.

Elephants are herbivorous and feed on leaves, plants, grains, fruits and more. They are mostly found in Africa and Asia. Most of the elephants are grey in color, however, in Thailand, they have white elephants.

In addition, elephants are one of the longest-lived animals with an average lifespan of around 5-70 years. But, the oldest elephant to ever live passed away at the age of 86 years.

Furthermore, they mostly inhabit jungles but humans have forced them to work in zoos and circuses. Elephants are considered to be one of the most intelligent animals.

Similarly, they are quite obedient too. Usually, the female elephants live in groups but the male ones prefer solitary living. Additionally, this wild animal has great learning capacity. Humans use them for transport and entertainment purposes. Elephants are of great importance to the earth and mankind. Thus, we must protect them to not create an imbalance in nature’s cycle.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Importance of Elephants

Elephants come in the group of most intelligent creatures. They are capable of quite strong emotions. These creatures have earned the respect of people of Africa that share the landscape with them. This gives them a great cultural significance. Elephants are tourism magnets for mankind. In addition, they also play a great role in maintaining the biodiversity of the ecosystems.

Most importantly, elephants are also significant for wildlife. They dig for water in the dry season with their tusks. It helps them survive the dry environment and droughts and also helps other animals to survive.

In addition, the elephants of the forest create gaps in the vegetation while eating. The gaps created enables the growth of new plants as well as pathways for smaller animals. This method also helps in dispersal of seeds by trees.

Furthermore, even elephant dung is beneficial. The dung they leave contains seeds of plants they have consumed. This, in turn, helps the birth of new grasses, bushes, and even trees. Thus, they also boost the health of the savannah ecosystem.

Endangerment of Elephants

Elephants have found their way on the list of endangered species. Selfish human activities have caused this endangerment. One of the biggest reasons for their endangerment is the illegal killing of elephants. As their body parts are very profitable, humans kill them off for their skin, bones, tusks, and more.

Moreover, humans are wiping out the natural habitat of elephants i.e. the forests. This results in a lack of food, area to live, and resources to survive. Similarly, hunting and poaching just for the thrill of it also cause the death of elephants.

Therefore, we see how humans are the main reason behind their endangerment. In other words, we must educate the public about the importance of elephants. Conservation efforts must be taken aggressively to protect them. In addition, poachers must be arrested to stop killing of the endangered species.

FAQs on Essay on Elephant

Q.1 Why are Elephants important?

A.1 Elephants are important not only to humans but wildlife and vegetation too. They provide sources of water for other animals in the dry season. Their eating method helps in the growth of new plants. They maintain the balance of the savannah ecosystem.

Q.2 Why is endangerment of elephants harmful?

A.2 Human activities have caused endangerment of elephants. Extinction of these animals will create an imbalance in the ecosystem gravely. We must take steps to stop this endangerment so they can be protected from extinction.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Animal Corner

Discover the many amazing animals that live on our planet.

Elephant Anatomy

The Complete Elephant Anatomy

Trunks | Tusks | Teeth | Brain | Hair | Ears | Feet | Skin | Senses and Communication

The elephants body is well adapted for the survival of rugged conditions of their habitats in Africa and Asia.

Elephants have strong, long trunks that perform multiple tasks, sharp tusks used for carrying heavy objects and for fighting with, large ears which they flap to keep themselves cool as well as having other functions. Elephants also have a tail that with one swish can whisk away flies and other insects making it the perfect fly swatter.

On the left is an anatomy diagram of the internal organs of a female elephant. Click on the image for a larger look at it.

The larger image will open in a new window, use the close button when finished.

Below you can see some distinct differences between the African elephant and the Asian elephants body structures. The African is larger, with much larger ears and larger all round in height and length. For more detailed information on either the African Elephant or the Asian Elephant, click on the individual images in the picture below.

Elephant Trunks

One of the most interesting features of an elephant is its trunk. An elephants trunk is both an upper lip and an extension of the nose with two nostrils running through the whole length.

The trunk has more than 40,000 muscles in it which is more than a human has in their whole body. A human being only has 639 muscles in total. An elephants trunk is both strong and very agile. It can perform multiple tasks from pushing over heavy trees to picking up the smallest twig. An elephant uses its trunk to pick up and throw objects, rub an itchy eye or ear, fills it with water and then pours it into its mouth to drink and also as a snorkel when swimming under water. Elephants also use it for feeding and for friendly wrestling matches with other elephants.

The trunk plays an important role in an elephants life by being used as an exploratory organ. The trunk is extremely flexible and can be used with the finest touch. At the first sign of danger, an elephant raises its trunk to smell the air and detect the smell of what is threatening. An elephant uses a whole range of smelling tasks as it is one of the elephants primary sensory organs, along with the ears. An elephants trunk is so important and vital to its life that it would be almost impossible for the elephant to survive should it ever get damaged.

Most animals use their nose solely for breathing, however, the elephant also uses its trunk for water storage and for drawing in mud and dust to spray over themselves to clean or cool down. An average elephant can hold and store 4 litres of water inside its trunk. The trunk has a sparse covering of fine sensory hairs and the skin covering the front of the trunk has rings of deep crevasses and resembles a slinky.

The African elephant has two prehensile fingers at the tip of its trunk which are used to grab hold of objects and smaller items. The Asian elephant has only one finger at the end of its trunk and usually only uses its trunk to scoop things up. Elephants can lift very heavy weights with its trunk, but it is important to remember that each elephant is individual and unique and the amount of weight each can lift varies. The trunk is not usually used in combat or for fighting with, but it can be used to make threatening gestures. However, elephants do use their trunks to play fight which can be quite interesting to observe.

Another interesting observation is when an elephant is charging. If its trunk is stretched out in front, then the elephant is just bluffing. However, it the trunk is curled or tucked downwards then it means business and is serious about its intentions. Like all vertebrates, elephants possess the Jacobson’s organ in its mouth (a smelling organ).

The elephant tests and experiments with different odours by touching a particular object with its trunk and then placing the trunk in its mouth. Elephants are very inquisitive creatures.

Elephant Tusks

Elephant tusks are very elongated incisor teeth. Elephants do not have any canine teeth at all. Both male and female African elephants have tusks, however, only the male species of the Asian elephant has them. Tusks continue growing for most of the elephants life. They are an age indicator – much like the elephants feet, the age of the elephant can be estimated by observing their tusks. The size of an elephants tusks is an inherited characteristic, however, because of ivory hunters, it would be quite rare today to find and elephant whose tusks weigh more than 100 pounds.

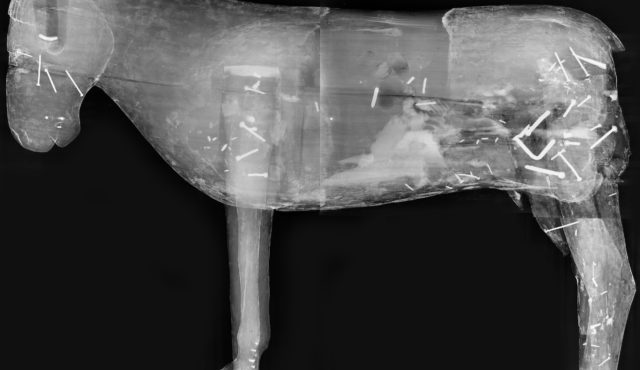

The total length of the tusks is not apparent on the outside of the elephant, about a third of the length of the tusk lies hidden inside the elephants skull. This is the unfortunate reason ivory hunters destroy the elephant for their tusks instead of just cutting them off. Ivory is really only dentine and is no different from ordinary teeth. It is the diamond shaped pattern of the elephants tusk which can be distinguished when viewed from a cross-section which gives elephant ivory its distinctive lustre.

Elephants are either ‘left-tusked’ or ‘right-tusked’, just like a human being might be ‘left-handed’ or ‘right-handed’. The favoured tusk is usually shorter than the other due to constant use. Tusks on an individual elephant can differ in shape, length, thickness and growth direction. Male elephants tend to have heavier, longer and more stouter tusks than females do.

An elephant uses its tusks to many many tasks just like its trunk. They use their tusks for digging, ripping bark of trees, foraging, carrying heavy objects and for resting a wary, heavy trunk on. They will also use them as weapons should they ever encounter conflict.

Tusks in a baby elephant (Calf) are present at birth and are really only like milk teeth. They measure only about 5 centimetres long. These ‘milk tusks’ will fall out around their first birthday. Their permanent tusks will then start to protrude beyond their lips at around 2 – 3 years old and will continue to grow throughout their lives.

Tusks grow at about 15 – 18 centimetres per year, however, they are continually worn down with constant use. Should they be allowed to continually grow without use, they would grow into a spiral shape (similar to those of the extinct woolly mammoth) as they typically grow following a curved growth pattern.

Interestingly, some elephants are born without tusks. This hereditary condition causes huge differences in the musculature and shape of the neck and the head of the elephant. Also, the carriage of the head is different and the bones at the back of the skull are less developed.

Not all male Asian elephants have tusks, there is approximately 40 – 50% of male Asian elephants that are tuskless. These particular males are known as ‘Makhnas ‘ in India.

Elephant Teeth

An elephants teeth are very unique in the manner in which they proceed from the back of each half jaw towards the front. The teeth follow a linear progression. As the front teeth continuously become more worn down they are slowly replaced with new teeth that give the elephant an ability to chew the coarse foods it eats particularly tree bark. The elephant has a total of 24 teeth, but only 2 are usually in use at any one time.

When an elephant is born, a calf has four developing teeth in each side of its jaws. These consist of their smallish first and second teeth which are present after birth and the end of a third and a forth which is still below the gum. As each tooth wears out, it is pushed forward to the front of the mouth and it slowly wears into a shelf as the roots are absorbed. The shelf eventually will break off and the remaining piece will be pushed out of the mouth.

After the first two teeth are gone, parts of the two adjacent teeth are being worn down in each half of the jaw. This process continues until the 6th and sometimes 7th molar appears. The 6th molar weighs on average an incredible 4 kilograms and has a maximum grinding length of 21 centimetres (and a width of 7 centimetres).

This 6th molar will be present for around half the elephants life. When the last molar tooth is worn down and the elephant can no longer chew properly, unfortunately it will usually starve or develop malnutrition and eventually die. This does not happen until the elephant is at least 60 – 70 years old. Below is a table showing the onset and loss of each tooth and age the above process usually occurs:

The molars of an elephant differ between the African and Asian species. Both have a series of ridges (laminae) which run across the tooth. However, in the Asian elephant the ridges are parallel as opposed to the diamond shaped ridges in the African elephant. Although the Asian elephant has grazing teeth, it is usually spends most of its time in forests as opposed to plains like the African elephant.

In both species of elephant, the movement of the jaw during chewing is forwards and backwards, unlike cows who use sideways movements to chew their cud. Therefore, the ridges act as two rasps grating upon one another and is made more effective by the teeth being slightly curved along the lengths.

Elephants Brain

Elephants are born with 35% of the mass of the adult brain. The elephant is among the more intelligent animals. The brain weight of the male African elephant is 4.2-5.4 kilograms. The brain weight of the female African elephant is 3.6 – 4.3 kilograms. Both are quite heavy in comparison to the adult human brain although brain development in elephants is quite similar to that of human beings.

Humans are born with small brain mass, so are elephants. As a human brain grows and develops, so does an elephant calfs brain. Likewise, the learning ability of a human increases with growth, so does that of an elephant calf. It is not surprising that elephants are such intelligent creatures. Although the female elephant brain is smaller than the male elephant brain, this does not suggest that the male is more intelligent than the female. Studies have revealed that the female elephant is equal to or even more intelligent than the male. Given the fact that female elephants are generally smaller to male elephants, the brain mass in proportion to the body size indicates the larger female brain.

Also, the brain and consciousness of the female elephant is much different than that of a male as they are reared and interact with their mothers in very different ways right from birth and while the females form a very close knit bond with each other which is constantly maintained, the males are more solitary and independent.

Although the brain of the elephant is the largest in size among all of the land mammals, it actually only occupies a small area at the back of the skull. However, in proportion to the size of the elephants body, the elephant brain is smaller than the human brain. Despite this, the elephant is one of the only animals along with all apes (including ourselves), sperm whales and a few other creatures who has a large brain relative to body size.

Elephant Hair

Although elephants are generally considered hairless animals, both African and Asian elephants are born with thick hair. The elephant fetus is covered with ‘Lanugo’, a mass of long, downy hair, however, most of this is shed before the elephant is actually born. The hair on an elephant calf sheds more as the elephant calf grows. The hair is not designed to provide warmth for the elephant, however, it does allow the elephant to sense the closeness of objects the hair touches.

The hair on an elephant is thickest on the tail and more visible on the head and back. The hair on the tail can reach a length of up to 100 centimetres.

The hair that appears around the eyes and nose have a protection purpose. It helps to keep out particles and germs from invading the body through the ears and nose. An elephant also has small sensory hairs along its trunk.

Baby elephants (calves) have lots of small fine hairs that cover most of their body. In the photo on the left, you can see the fine hair on the calfs forehead and lower back. These hairs will last in the same density long after the elephants first birthday and then as the elephant grows the hair will gradually become thinner and become less visible.

Elephant Ears

The African elephant has ears that are at least 3 times the size of the Asian elephants ears. The African elephant uses its ears as signaling organs. Ears are also used to regulate body temperature and are used as a protective feature in the African elephant to ward off potential threats. Each elephants ear is unique and different to any other elephants ear. They are used just like fingerprints on a human as a type of identification. The ears serve several important functions in the elephant. When a threat is perceived by the elephant, the ears are spread wide on each side of the head, which produces a huge frontal area.

Because the elephant is such a large bulbous shape and contains large organs, their insides generate a lot of heat, particularly the digestive system. The surface area of an elephant is a lower ratio compared to the elephants volume. Therefore, there is not enough skin area to cope with the heat that needs expelling. So elephants use their ears to perform this function. When an elephant flaps its ears, it can lower their blood temperature by 10 degrees Fahrenheit . Both the African and Asian elephants use their ears for this purpose although it is more effective in the African elephant due to the larger ears.

The wider surface area of outer ear tissue on the African elephants ears consists of a vast network of capillaries and veins. Hot blood in the arteries are filtered through these and cooler blood is returned to the elephants body.

It is not uncommon to see an elephant facing down on a windy day with its ears extended to allow the cool wind to blow across the hot arteries. The physical structure of the elephant ear is simply a sheet of cartilage covered by thin skin. Another amazing function of the elephant ear is its ‘infra sound capabilities’. This is used for long range communication between the elephants. Elephant ears are extremely sensitive and studies have proved that elephants can communicate over great distances with each other. Elephants can use this communication which is unhearing to human ears to warn of impending dangers in the far distance. So do not forget, if you have the opportunity to ever touch the ears of an elephant, be very careful as they are very soft and sensitive.

Elephant Feet

Elephants feet are unique and very interesting. They are quite different from other animal feet. An elephants foot is designed in such a way that elephants actually walk on the tips of their toes. Because of the way it walks, elephants are also known as ‘Digitigrades’ and belong to a group of animals that also includes horses, cattle, sheep, camels and rhinos. All elephants do not have the same number of toes on each foot. The African elephants have 4 toes on their front feet and 3 toes on their back feet. Asian elephants on the other hand, have 5 on the front and 4 at the back.

The sole of the foot is also ridged and pitted which gives the elephant stability when walking over a variety of terrains. Its design prevents the elephant from slipping on smooth surfaces such as ice and snow. The reason that elephants can walk so quietly is in part due to the ‘elastic spongy cushion’ on the bottom of the foot smothering any objects beneath itself. This causes most noises (including the cracking of sticks and twigs) to be muffled.

The fore feet of an elephant have a circular shape whereas the back feet are a more oval shape. The footprint of an elephant can tell you a few things about that particular elephant. For example, elongated oval footprints usually indicates that they belong to a male elephant, whereas a more rounded footprint indicates a female elephant. Male elephants tend to leave double footprints as their rear leg falls slightly to the side of their front leg. Females tend to walk more precisely in the same spot with both legs.

The footprint can also tell you what age the elephant might be. Younger elephants leave a more crisp and defined footprint. Older elephants leave a more undefined footprint because of smoother ridges and worn heels. The height of the elephant can also be determined by its footprint. Twice the circumference of the footprint suggests how tall the elephant is to the height of its shoulder. Elephants footprints can play a beneficial role for other animals. Their large, deep prints create holes in which water can be collected in providing water holes for small animals, roots can be dug up from the ground and navigation on difficult terrain can be made easier.

The structure of the foot allows an elephant to walk in deep mud without difficulty, because when it is being withdrawn the circumference becomes smaller which in turn reduces the suction preventing the elephant from being drawn deeper into the mud.

Elephant Skin

Although elephants belong to the Pachyderm species which means ‘thick-skinned’ animals, they actually have very thin skin except in certain places such as the back and the sides where it is about 2 – 3 centimetres thick. The thinnest parts of skin are behind their ears, around their eyes, on the chest, abdomen and shoulders. On these parts, their skin is as thin as paper. Skin provides a protective function for all animals, however, there are some unique characteristics about the elephants skin. Elephants skin is very sensitive to the sun. Elephant calves are constantly shadowed by their mothers to avoid sunburn.

Elephants naturally love water, however, one of the reasons they enjoy wallowing in mud, lakes and rivers is to keep cool when it is very hot. Elephants also use their trunks to draw up cool water and squirt it over their backs and heads to wet the skin most exposed to the sunlight. The absence of sweat glands is also another important reason for elephants to spend a lot of time in water and mud.

Wrinkles increase the surface area of the skin so when the elephant bathes in water, there is more skin to wet. When the elephant comes out of the water, the cracks and crevices of the wrinkles trap the water and because it takes longer to evaporate in the heat it keeps the elephants skin moist longer than it would if it had smooth skin.

Skin structure on an elephant can also distinguish whether they are Asian or African. Asian elephants have finer skin than African elephants and it is sometimes colorless except for some ‘white spots’ around the ears and forehead.

The natural skin color of the African elephant is greyish black, but all elephant skin color changes and is determined by the color of the soil of the land where their habitat is. Elephants have a habit of throwing mud over their backs and this gives them their apparent coloring.

Elephant Senses and Communication

By better understanding an elephants view of the world we can become more aware of how amazing these animals really are. As human beings, the impact our senses have on the nature of our experiences such as what we see, hear, smell and touch, play a huge part in determining our world. Likewise, it is important that we recognize the world of an elephant is much different from our world. For instance, the eyesight of an elephant is not as far reaching as a humans eyesight, however, an elephants sense of smell is unparalleled. The elephants acute sense of smell is also used in communication along with its other senses of vision, touch, hearing and the amazing ability to detect vibrations.

An elephant is capable of hearing sound waves well below the human hearing limitation. They communicate using both high and low frequency sounds. Low frequency rumbles are made to warn other elephants at long distance of a current situation whereas high frequency sounds such as trumpeting, barking, snorting and other loud calls are used to communicate to those nearer.

Using their heads, bodies, trunks, ears and tail for communicating is the elephants natural language. Visual communication includes movements of the head, mouth, tusks and trunk. For example, when a female elephant feels threatened, she will make herself appear larger by holding her head as high as she can and spreading her ears wide. Chemical communication is the use of the trunk. The elephant will lift its trunk to smell the air or root around the floor usually searching for urine spots and urine trails.

Tactile communication usually involves the whole body, feet, tail, ears, trunk and tusks and is mostly to do with touch. An elephant will use its tusks to provoke aggression or to lift a baby elephant out of a mud wallow. The rubbing together of ears shows affection. Depending on how the elephant moves and uses its body parts depicts the mood of the animal.

Such moods and body movements show if the elephant is angry, happy, anti-predator, parental, excited or sad. Every observation of the elephant senses shows an insight to the world the elephant lives in. It is important to remember that the elephants world is a completely different world from ours based on its sensory experiences.

Understanding Elephant Anatomy: A Comprehensive Guide

Have you ever wondered about the intricate anatomy of elephants , those gentle giants roaming our planet? We have too! In fact, did you know that elephants walk on their toes like professional ballet dancers yet remain utterly silent due to a unique foot structure ? With extensive research , we’ve dissected every aspect of elephant anatomy in this comprehensive guide.

Don’t miss out, let’s dive deep into the world of these magnificent creatures.

Key Takeaways

- Elephants have a unique foot structure that allows them to walk silently on their toes.

- The trunk of an elephant is an incredible tool that serves multiple functions, such as breathing, drinking, and communication.

- Elephant tusks continuously grow throughout their lifetime and play important roles in digging for food, defending against predators, and displaying dominance within the herd.

- Elephant skin is thick and provides protection from the sun’s harmful rays and insect bites.

Overview of Elephants

Elephants are large mammals that belong to the family Elephantidae , which includes two species – the African elephant and the Asian elephant.

What are elephants?

Elephants are fascinating, intelligent mammals primarily recognized by their large size, long trunks and tusks. Three main species exist: the African savanna elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant.

They play an essential role in maintaining the balance of their ecosystems with their herbivorous habits and extensive travels that promote seed dispersal . Despite this crucial role, elephants face numerous threats due to habitat loss and illegal poaching for ivory – a material obtained from their tusks.

A distinctive feature is their trunk or proboscis which hosts over 40,000 muscles; quite astonishing considering that’s far more than what we humans have in our entire body! This unique tool serves multiple purposes such as detecting smells or potential danger but can also store up to 4 liters of water at once – handy for those parched moments in the wild! Another intriguing fact about these gentle giants is that they have incredible memory capabilities allowing them to recognize human body language among other things proving just how intellectually advanced they truly are.

Elephants aren’t just physically remarkable animals but deeply complex creatures who continue to captivate us with every new discovery into their world.

Different species of elephants

Let’s delve into the fascinating world of elephants, where diversity abounds. There are three primary species that exist today:

- The African Savanna Elephant : This is the largest land mammal in existence today. Notably found in sub-Saharan Africa, they boast large ears and a concave back.

- The African Forest Elephant : Residing predominantly within the dense rainforests of West Africa and the Congo Basin, these elephants take second place in size. They were recognized as a unique species as recently as 2000.

- The Asian Elephant : Divided further into three subspecies – Indian, Sumatran, and Sri Lankan – they represent their continent well with smaller ears and a convex or straight back.

Are elephants endangered?

Absolutely, both African and Asian elephants are endangered species . Disturbingly, more than half of the African elephant population reduced from 1979 to 1989 . At the start of this century, less than 50,000 wild Asian elephants were counted.

This decline is majorly due to habitat loss and poaching. In order to protect these magnificent mammals and maintain our diverse ecosystems, we must take swift actions to stop these threats.

The plight of the pachyderm species underscores the urgent need for conservation efforts worldwide.

Elephant Anatomy: Form and Function

Elephant trunks are a remarkable feature of their anatomy , serving multiple functions such as breathing, smelling, eating, drinking, and even communication.

Elephant Trunks

Elephant trunks act as a crucial tool in their everyday lives. With over 40,000 muscles , these versatile proboscises are incredibly sensitive and adaptable. They allow elephants to perform a wide range of activities from sipping water to lifting objects.

An elephant can store up to 4 liters of water in its trunk , turning it into a portable hydration station during arduous treks across the parched savannah. Moreover, an elephant’s trunk functions as a snorkel when they’re swimming or wading through deep waters – quite the multipurpose tool! Another intriguing fact is the way an elephant’s trunk position communicates intentions; just one example of their complex visual communication methods within the herd.

Elephant Tusks

Elephant tusks are fascinating and unique features that play a crucial role in an elephant’s life. These elongated incisor teeth can grow to be as long as 3 meters and weigh over 100 kilograms each .

They continuously grow throughout an elephant’s lifetime , providing various functions. Tusks are used for activities like digging for food and water, defending against predators , and displaying dominance within their herd .

Unfortunately, the ivory from these tusks is highly valuable in the illegal wildlife trade , posing a significant threat to elephant conservation efforts. African elephants typically have larger and heavier tusks compared to their Asian counterparts .

Elephant Teeth

Elephants have a fascinating dental system, with a total of 24 teeth . However, only two of these teeth are usually in use at any given time. Why? Well, elephants continuously replace their worn-out teeth throughout their lives.

These massive mammals have six sets of molars that gradually move forward as the front set wears down and falls out. This process allows new teeth to come in from the back to take their place.

So, while an elephant may not get a shiny penny from the tooth fairy, they do get fresh and functional chompers!

One prominent feature of an elephant’s dental structure is its elongated incisor teeth – also known as tusks. The size of an elephant’s tusks is actually hereditary; it’s passed down from generation to generation.

Elephant Ears

Elephant ears serve multiple functions for these majestic creatures. Firstly, their large surface area helps to dissipate heat and regulate body temperature . This is especially important in hot climates where elephants reside.

Secondly, elephant ears enhance their hearing abilities by capturing and funneling sound waves towards their eardrums. Not only does this allow them to detect low-frequency rumbles from other elephants over long distances, but it also allows them to pick up on high-frequency sounds that escape the range of human hearing.

Additionally, the flapping motion of elephant ears can deter pests like flies and mosquitoes , providing some relief from annoying insects. Lastly, the shape and size of an elephant’s ears are unique to each individual, serving as a distinguishing feature that adds to their overall anatomy and behavior.

Elephant Feet

The feet of elephants are fascinating and unique. They walk on the tips of their toes, with African elephants having 4 toes on their front feet and 3 toes on their back feet, while Asian elephants have 5 toes on the front and 4 on the back .

The soles of an elephant’s feet are made of tough, fatty connective tissue which acts as a shock absorber and allows for silent movement. The ridged and pitted sole provides stability on various terrains and prevents slipping on smooth surfaces.

The shape of an elephant’s forefeet is circular, while the back feet are more oval.

Elephant Skin

Elephant skin is a remarkable feature that serves multiple purposes. Firstly, it provides protection for these magnificent creatures from the sun’s harmful rays, insect bites, and potential abrasions.

In fact, in some areas of an elephant’s body, its skin can be as thick as 2.5 cm! Additionally, elephant skin plays a role in regulating their body temperature through sweat glands found within the folds of their skin.

Elephants also have a unique way of keeping cool by covering themselves in mud or dust baths which serve to both cool them down and protect their sensitive skin. Another interesting characteristic of elephant skin is its elasticity; it allows these animals to move freely without tearing their protective covering.

Special Features of Elephant Anatomy

Elephants possess several special features that set them apart from other animals. From their highly intelligent brains to their unique sensory organs, elephants are truly remarkable creatures.

Discover more about these fascinating special features by reading on!

Elephant Brain and Intelligence

Elephants have an incredibly sophisticated and intelligent brain. On average, an elephant’s brain weighs between 4.5 to 5.5 kilograms (10-12 pounds). This large size is directly connected to their complex social behaviors and advanced cognitive abilities .

In fact, elephants possess a well-developed hippocampus, which is responsible for memory and spatial awareness. They even have the ability to recognize themselves in mirrors , indicating self-awareness.

Additionally, these magnificent creatures display empathy and compassion towards other members of their herd , showcasing a high level of emotional intelligence.

Elephant Hair

Elephant hair is a unique and important feature of these magnificent creatures. Found on their tails, ears, and heads, elephant hair serves several crucial functions. The long strands of hair on an elephant’s tail can reach up to 1.5 meters in length ! This hair acts as protection against the sun, insects, and other environmental factors that could harm their sensitive skin.

Additionally, the hair on an elephant’s head and ears acts as a sensory organ , allowing them to detect subtle vibrations and changes in their surroundings. Not only does it provide insulation for regulating body temperature but also allows air to flow through during hot climates .

The color of elephant hair can range from dark brown to gray , adding to the fascinating diversity of these remarkable animals’ characteristics.

Elephant Senses and Communication

Elephants have an impressive array of senses that help them navigate their environment and communicate with each other. Their sense of smell is highly developed, allowing them to detect scents from great distances.

They also have excellent hearing and can pick up low-frequency sounds that are too low for humans to hear. In addition, elephants use infrasound, which is sound below the range of human hearing, to communicate with each other over long distances.

But it’s not just their sensory abilities that aid in communication – elephants also rely on vocalizations like trumpeting and rumbling , as well as body language such as head shaking, ear flapping, and trunk gestures .

Elephant Reproduction

Elephant reproduction is a complex and fascinating process. Female elephants begin breeding once they reach puberty, which usually occurs when they are around 12 to 14 years old. The gestation period for elephants is incredibly long, lasting between 18 to 22 months, the longest among mammals.

Female elephants have a menstrual cycle that lasts between 13 to 18 weeks, with a peak phase known as estrus or being in heat .

During this time, male elephants in musth, a period of increased sexual activity and aggression, often guard female elephants in their peak cycle. Mating involves a ritual where the female rubs against the male and entwines trunks.

Successful mating requires the male to chase the female and mount her for at least one or two minutes.

Interesting Facts about Elephants

Elephants have over 40,000 muscles in their trunks . They can hold and store up to 4 liters of water in their trunks . The trunk is an important sensory organ for elephants, used for smelling the air and detecting potential threats. Elephant tusks are elongated incisor teeth used for digging and carrying heavy objects. Elephant eyes have moderately strong vision, able to determine the shape of an object at 150m. Elephant skin is tough, grey, and wrinkled, with a thickness of up to 3.8cm in certain areas .

In conclusion, understanding the anatomy of elephants provides fascinating insights into their incredible abilities and adaptations . From their highly versatile trunks to their impressive tusks and teeth , elephants have evolved unique features that enable them to survive in diverse habitats.

Their immense intelligence and exceptional sensory organs further contribute to their remarkable existence in the animal kingdom. The more we learn about elephant anatomy , the better equipped we are to appreciate and protect these magnificent creatures for future generations.

1. What are some unique aspects of an elephant’s anatomy?

Elephants have several unique characteristics, including walking on the tips of their toes, having prehensile fingers on their trunks for smell and touch tasks, and using low-frequency rumbles for long-range communication .

2. Can elephants regulate their body temperature?

Yes, elephants use various methods to control body heat such as expelling it through capillaries in their large ears and wallowing in mud. Their skin structure includes thick fatty connective tissue contributing to this factor too.

3. How does sensory hair aid elephants?

Elephants use sensory hairs present throughout the trunk and body to detect vibrations and threats from afar. These fine sensory hairs also help them smell the air to detect odours or danger.

4. Are tusks one of the primary components of elephant anatomy?

Absolutely! Tusks formed by dentine are critical not only structurally but culturally as well with threatening gestures among males or unfortunately attracting ivory hunters which is a threat these animals face.

5. Do Elephants possess specific teeth structures?

Certainly! Elephants have molar teeth for grinding coarse foods along with milk tusks appearing temporarily in baby elephants while besides these canine teeth are found commonly amongst solitary tuskless ones known as Makhnas.

6. Do all parts of an Elephant’s body communicate something?

Interestingly enough yes! The tail communicates emotions; Ears act as heat expellers while showing aggression or fear when spread out; Trunk (proboscis) aids in sound production showing joy or irritation; Feet display friendly gestures besides detecting subtle ground vibrations too.

Elephant Parts: Great List of 12 Parts of an Elephant

Have you ever wondered about the different parts of an elephant? These majestic creatures are known for their large size and unique features, but what makes up their anatomy? In this article, we will explore the various parts of an elephant and their functions.

Table of Contents

Elephants are the largest land animals on Earth, and their anatomy is nothing short of remarkable. They are known for their unique physical characteristics, which make them stand out from other animals.

Body Size and Shape

The elephant’s body is massive and bulky, with a round belly and a wide back. They can grow up to 13 feet tall and weigh up to 22,000 pounds. Male elephants are typically larger than females, with longer tusks and a more prominent forehead.

One of the most distinctive features of an elephant is its trunk. The trunk is a multi-functional organ with over 40,000 muscles. Its primary functions are for breathing, smelling, touching, and grasping. Elephants also use their trunks to drink water, which they then squirt into their mouths, and they can even use their trunk as a snorkel when swimming.

Elephants have two long, curved tusks made of ivory that protrude from their upper jaw. Tusks are used for root digging, brush clearing, fighting over females, and self-defense. They also protect their trunks, which are an important part of an elephant’s body.

The elephant’s large ears are one of its most distinguishing characteristics. Elephants use their ears to regulate their body temperature, as well as to communicate with other elephants. They can also use their ears to detect sounds from long distances.

Elephants have thick, wrinkled skin that is gray in color. Their skin is as thin as paper, but it provides a protective function for all animals . However, there are some unique characteristics about the elephant’s skin. For example, elephants have sparse hair on their skin and their skin is covered in a layer of dust and mud to protect them from the sun.

Elephant Parts

Elephants are the largest grassland animal in the world. They can hear with their feet and live an average of 70 years.

An elephant’s trunk is one of its most distinctive features. It is a long, muscular appendage that serves many functions, including breathing, smelling, touching, grasping, and making sounds. The trunk is made up of over 100,000 muscles and can be up to 2 meters long. Elephants use their trunks to drink water, pick fruits, and even to spray themselves with dust or mud to keep cool.

Elephant tusks are elongated incisor teeth that protrude from the upper jaw. Tusks are used for a variety of purposes, including defense, digging, and foraging. Tusks can grow up to 3 meters long and can weigh over 100 kilograms. Unfortunately, elephants are often hunted for their tusks, which are highly valued in some cultures for their ornamental and medicinal properties.

Elephants have six sets of teeth throughout their lives, but they only have two or three teeth in their mouth at any given time. As their front teeth wear down, they are replaced by new teeth that move forward to take their place. This process continues throughout their lives, and when they run out of teeth, they can no longer chew their food properly and may die of starvation.

Legs and Feet

Elephants have four legs that are very strong and sturdy. Their feet are wide and cushioned, which helps them to distribute their weight evenly and walk quietly. Elephants walk on their toes, which are covered by thick, calloused pads. They also have a fifth toe, which is located higher up on their leg and is used for balance and support.

Parts of An Elephant | List

Frequently asked questions.

What are the body parts of an elephant and their uses?

Elephants have many body parts that help them survive in their natural habitat. Some of the most important body parts include their trunks, tusks, ears, and feet. Elephants use their trunks for a variety of tasks, such as breathing, smelling, and grabbing food. Their tusks are used for defense and to dig for food and water. Their large ears help them regulate their body temperature, and their feet are used for walking long distances and foraging for food.

What are 5 characteristics of an elephant?

Elephants are known for their intelligence, social behavior, communication skills, and memory. They also have a unique ability to use tools and to show empathy towards other elephants and even other species. Elephants are also known for their long lifespans, with some living up to 70 years in the wild .

What are the physical features of an elephant?

Elephants are characterized by their large size, gray skin, and long trunks. They also have large ears that they use to regulate their body temperature, and their tusks can grow up to 10 feet long. Elephants have four legs and large, flat feet that help them walk long distances and forage for food.

Why is an elephant’s skin so thick?

An elephant’s skin is very thick and tough, which helps protect them from predators and the harsh elements of their environment. Their skin is also wrinkled, which helps them retain moisture and stay cool in hot weather.

What are some uses of an elephant’s tusk?

Elephants use their tusks for a variety of tasks, such as digging for food and water, defending themselves from predators, and foraging for food. Unfortunately, elephants are also hunted for their tusks, which are made of ivory and are highly valued in some cultures.

How does an elephant use its trunk?

An elephant’s trunk is a highly versatile tool that they use for a variety of tasks. They can use it to breathe, smell, grab food and water, and even communicate with other elephants. Elephants can also use their trunks to make loud trumpeting sounds , which they use to communicate with other elephants over long distances.

Related terms:

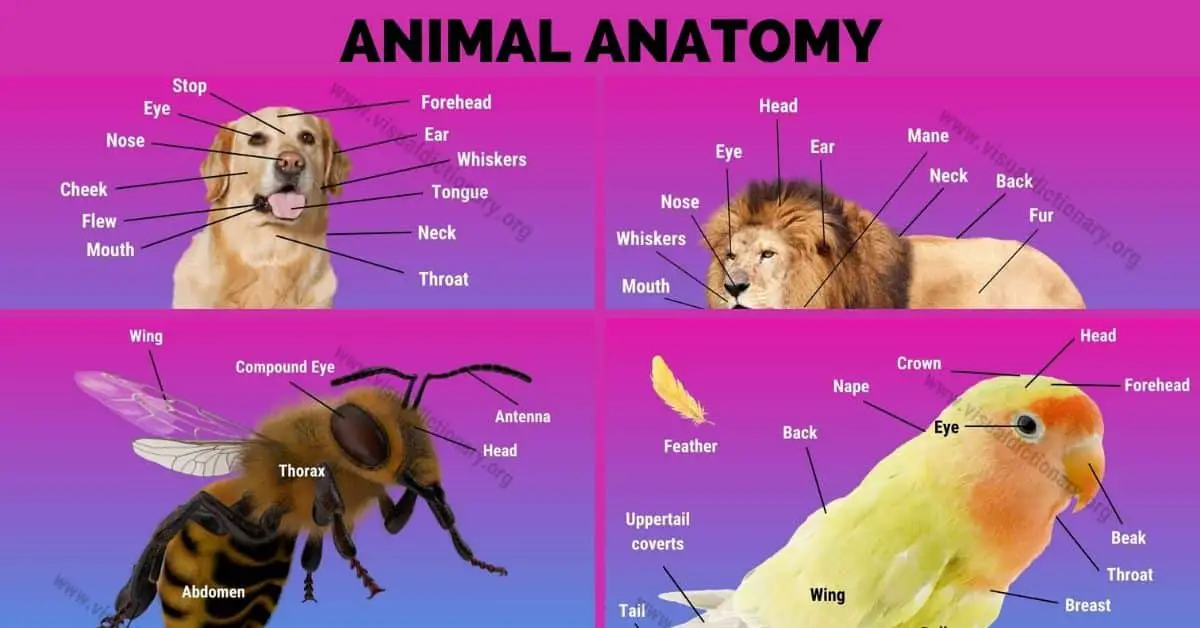

- Parts of a Goat

- Parts of a Pig

- Parts of a Horse

- Parts of a Cow

- Parts of a Lion

- Parts of a Dog

- Parts of a Cat

- Parts of a Tiger

Related Posts:

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

African Elephant

An adult African elephant's trunk is about seven feet (two meters) long! It's actually an elongated nose and upper lip. Like most noses, trunks are for smelling.

When an elephant drinks, it sucks as much as 2 gallons (7.5 liters) of water into its trunk at a time. Then it curls its trunk under, sticks the tip of its trunk into its mouth, and blows. Out comes the water, right down the elephant's throat.

Since African elephants live where the sun is usually blazing hot, they use their trunks to help them keep cool. First they squirt a trunkful of cool water over their bodies. Then they often follow that with a sprinkling of dust to create a protective layer of dirt on their skin. Elephants pick up and spray dust the same way they do water—with their trunks.

Mission Animal Rescue: Elephants

Elephant power, baby elephants, elephants play soccer.

Elephants also use their trunks as snorkels when they wade in deep water. An elephant's trunk is controlled by many muscles. Two fingerlike parts on the tip of the trunk allow the elephant to perform delicate maneuvers such as picking a berry from the ground or plucking a single leaf off a tree . Elephants can also use its trunk to grasp an entire tree branch and pull it down to its mouth and to yank up clumps of grasses and shove the greenery into their mouths.

When an elephant gets a whiff of something interesting, it sniffs the air with its trunk raised up like a submarine periscope. If threatened, an elephant will also use its trunk to make loud trumpeting noises as a warning.

Elephants are social creatures. They sometimes hug by wrapping their trunks together in displays of greeting and affection . Elephants also use their trunks to help lift or nudge an elephant calf over an obstacle, to rescue a fellow elephant stuck in mud, or to gently raise a newborn elephant to its feet. And just as a human baby sucks its thumb, an elephant calf often sucks its trunk for comfort. One elephant can eat 300 pounds (136 kilograms) of food in one day.

People hunt elephants mainly for their ivory tusks. Adult females and young travel in herds, while adult males generally travel alone or in groups of their own.

Explore more!

Amazing animals, comeback critters, save the earth tips, endangered species act.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Elephant Essay

Elephants are the largest land animals with distinct body parts. Unlike other mammals, elephants don’t have nose, instead they breathe through a long trunk. They have huge fan like ears and long extended teeth called tusks. Because of their distinct tusks they are often called tuskers.

Elephants are wild animals; though, they are also domesticated by humans to mainly perform laborious tasks. Colossal body parts give the elephants tremendous physical strength over humans, thus they are tamed and made to perform strenuous and challenging tasks. Elephants have a distinct social structure displaying feelings of compassion, love and care for the family members.

Long and Short Essay on Elephant in English

We have provided below various essay on elephant in order to help students.

Now-a-days, essays and paragraphs writing are more common strategy followed by the teachers in the schools and colleges in order to enhance student’s skill and knowledge about any subject.

All the elephant essay given below are written using very simple words and easy sentences under various words limit. Students can select any of the essays given below according to their need and requirement:

Elephant Essay 1 (100 words)

Elephant is a very big animal. It lives in the forest however it is a pet animal also. Some people keep it at home as a pet animal in order to earn money through circus. It is also kept in the zoo in order to enhance the glory of zoo as well as interest of kids. It has a big body with four legs like pillars, two fan like ears, a long trunk, a short tail and two small eyes. A male elephant contains two long white teeth called as tusks. It can eat soft green leaves, plants, grains, etc. It is very useful animal to the man and proved to be a good friend to mankind as it performs many functions such as earns money, carries heavy loads, etc. It has long life span and lives around one hundred years.

Elephant Essay 2 (150 words)

Elephant is a biggest animal on the land. It is also considered as the strongest animal on the land. Generally it is a wild animal however can live as a pet animal after proper training in the zoo or with human being at home. It has been proved a useful animal for the humanity. It is an animal with big body generally found in the grey color.

It’s all four legs looks like a pillar and two big ears just like a fan. Its eyes are quite small in comparison to the body. It has a long trunk and a short tail. It can pick up a range of things very easily through its trunk such as a small needle and very heavy trees or loads. It has two long white tusks on each side of trunk.

Elephants live in the jungle and generally eat small twigs, leaves, straw and wild fruits however a pet elephant can also eat bread, bananas, sugarcane, etc. It is a pure vegetarian wild animal. Now-a-days, they are used by the people to carry heavy loads, in the circus, lifting logs, etc. In the ancient time, they were used by the kings and dukes in the wars and battles. It lives for long years (more than 100 years). It is very useful animal even after death (bangles are made of bones and tusks).

Elephant Essay 3 (200 words)

Elephant is a largest animal on the land. It lives in the forest however can be a pet after proper training. It can be more than eight feet in height. Its big and heavy body is supported by the strong pillar like legs. It takes help of its long trunk in eating leaves, plants, fruits or trees. Generally two types of elephants are found on land African (scientific name is Loxodonta africana) and Asian (scientific name is Elephas maximus).

Its big hanging ears looks like a fan and legs like a pillar. It has a long trunk attached with mouth and two tusks each side. The trunk of an elephant is very flexible and strong and known as a multi-purpose organ. It is used for feeding, bathing, breathing, expressing emotions, fighting, etc by the elephant.

African elephants are little bigger is size and darker in color than the Asian elephants. They have more prominent ears also. Elephants are commonly found in India, Africa, Sri Lanka, Burma, and Siam. They generally like to live in a herd and become very fond of water. They know well about swimming. Because of being an herbivorous animal, they depend on plants in the forest in order to meet their food need. They move to villages and other residential places in the lack of food in forest or because of deforestation. It is known as an intelligent animal and benefits man in many ways.

Elephant Essay 4 (250 words)

Elephant is a strongest and biggest animal on the earth. It is quite famous for its big body, intelligence and obedient nature. It lives in jungle however can be trained and used by people for various purposes. Its peculiar features are four pillars like legs, two fan like ears, two small eyes, a short tail, a long trunk, and two long white tusks. Elephant eats leaves, stem of banana trees, grass, soft plants, nuts, fruits, etc in the jungle. It lives more than hundred and twenty years. It is found in India in the dense jungles of Assam, Mysore, Tripura, etc. Generally elephants are of dark grey color however white elephants are found as well in the Thailand.

Elephant is an intelligent animal and has good learning capacity. It can be trained very easily according to the use in circus, zoo, transport, carry loads, etc. It can carry heavy logs of timber to a long distance from one place to another. It is an animal of kid’s interest in the zoo or other places. A trained elephant can perform various tasks such as delightful activities in the circus, etc. It can be very angry which create danger to the humanity as it can destroy anything. It is useful animal even after death as its tusk, skin, bones, etc are used to make costly and artistic items.

Elephant Essay 5 (300 words)

Elephant is a very huge wild animal lives in a jungle. It looks quite ugly however mostly liked by the kids. It has big heavy body and called as royal animal. It can be more than 10 feet in height. It is found in coarse dark grey color with very hard skin. In other countries, it is found in white color also. Its long and flexible trunk helps in feeding, breathing, bathing and lifting heavy loads. Its two big ears hanging like big fans. Its four legs are very strong and look like pillars. Elephants are found in the forests of India (Assam, Mysore, Tripura, etc), Ceylon, Africa, and Burma. Elephants like to live in groups of hundreds (lead by a big male elephant) in the jungle.

It is very useful animal to the humanity whole life and after death also. Its various body parts are used to make precious things all over the world. Bones and tusks of elephant are used to make hooks for brushes, knife-handles, combs, bangles including other fancy things. It can live for many years from 150 to 200 years. Keeping elephant at home is very costly which an ordinary person cannot afford.

It has very calm nature however on teasing it can be very angry and dangerous as it can destroy anything even kill people. It is known as intelligent and faithful animal because it understands every sign of the keeper after training. It obeys its keeper very sincerely till death.

There are two types of elephant, African and Indian. African elephants are quite bigger than Indian elephant. Both, male and female African elephants have tusks with wrinkly gray skin and two tips at the end of trunk. Indian or Asian elephants are quite smaller than African elephants with humped back and only one tip at the end of trunk.

Elephant Essay 6 (400 words)

An elephant is very clever, obedient and biggest animal on the earth. It is found in the Africa and Asia. Generally, it is found in grey color however white in Thailand. Female elephants are used to live in groups however male elephants solitary. Elephants live long life more than 100 years. They generally live in jungles however also seen in the zoo and circus. They can grow around 11 feet in height and 13,000 pounds weight. The largest elephant ever has been measured as 13 feet in height and 24,000 pounds in weight. An individual elephant can eat 400 pounds of food and drink 30 gallons of water daily.

Elephant skin becomes one inch thick however very sensitive. They can hear each other’s sound from long distance around 5 miles away. Male elephant starts living alone whenever become adult however female lives in group (oldest female of a group called as matriarch). In spite of having intelligence, excellent hearing power, and good sense of smell, elephants have poor eyesight.

Elephants look very attractive to kids because of its interesting features such as two giant ears, two long tusks (around 10 feet long), four pillars like legs, a huge trunk, a huge body, two small eyes, and a short tail. It is considered that tusks are continued to grow entire life. Trunk is used to eat food, drink water, bath, breathe, smell, carry loads, etc. It is considered as elephants are very smart and never forget any event happened in their life. They communicate to each other in very low sound.

The baby of an elephant is called calf. Elephants come under the category of mammals as they give birth to a baby and feed their milk. A baby elephant can take almost 20 to 22 months in getting fully developed inside its mother womb. No other animal’s baby takes such a long time to develop before birth. A female elephants give birth to a single baby for every four or five years. They give birth to a baby of 85 cm (33 inch) tall and 120 kg heavy. A baby elephant takes almost a year or more to learn the use of trunk. A baby elephant can drink about 10 liters of milk daily. Elephants are at risk of extinction because of their size, prized ivory tusks, hunting, etc. They should be protected in order to maintain their availability on the earth.

More Information:

Essay on Cow

Essay on Tiger

Essay on Peacock

Related Posts

Money essay, music essay, importance of education essay, education essay, newspaper essay, my hobby essay, leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Essay on Elephants

Introduction to Elephants

Elephants, majestic giants of the animal kingdom, embody a profound cultural and ecological significance globally. Revered in numerous societies, particularly in Asia, where they hold religious and symbolic importance, elephants have served as mythical creatures and practical assets throughout history. Today, they face critical challenges such as habitat loss, poaching, and conflicts with human development, threatening their survival. Despite these threats, conservation efforts strive to protect these gentle giants, highlighting the intricate balance between human progress and wildlife preservation. Understanding elephants involves delving into their symbolic, historical, and environmental roles, reflecting on our shared responsibility toward their future.

Anatomy and Physical Characteristics

Elephants are incredibly unique creatures, both in their anatomy and physical characteristics. Here are some key points you might consider covering:

Watch our Demo Courses and Videos

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Mobile Apps, Web Development & many more.

| Elephants are the most giant land animals, with African elephants larger than Asian elephants. They can weigh several tons and stand several meters tall at the shoulder. | |

| An elongated nose and upper lip are used for breathing, smelling, drinking, grabbing objects, and making sounds. | |

| Male African elephants and some Asian elephants have elongated incisor teeth. They use tusks for digging, defense, and other tasks. | |

| Elephants use their large, fan-shaped ears to regulate body temperature. It can flap to cool down. | |

| Thick but sensitive skin, up to an inch thick in some places, sparsely covered with coarse hair. | |

| Pillar-like legs with large, padded feet to distribute weight. Surprisingly agile despite the size. | |

| Throughout a lifetime, individuals use several sets of molars to grind vegetation. New teeth replace worn ones, moving forward in the jaw. | |

| It supports massive weight with adaptations like large leg bones and a solid pelvic girdle. |

Behavior and Social Structure

Elephants, the largest land mammals, are known for their complex behavior and intricate social structures. They exhibit intelligence and close bonds essential for their survival.

- Communication: Elephants communicate through vocalizations, body language , and seismic signals. Their low-frequency rumbles can be heard across great distances, and they trumpet and roar. They use these rumbles for various purposes, including coordinating movements, maintaining group cohesion, and signaling distress or reproductive readiness.

- Emotional Intelligence: Elephants display a remarkable level of emotional intelligence. They exhibit behaviors indicative of empathy , such as comforting distressed individuals and mourning deceased companions. Elephants have shown signs of grief, lingering near the remains of deceased herd members and even covering them with leaves and branches.

- Problem-Solving and Tool Use: Elephants are capable of problem-solving and using tools. Observers have seen them using branches to swat flies, create shade, or scratch themselves. Their ability to learn from experience and modify their behavior highlights their cognitive capabilities.

- Play and Social Learning: Young elephants engage in play, which is crucial for their social and physical development. Play behaviors include mock fights, chasing, and trunk wrestling. Young elephants learn essential social skills through play and bond with their peers.

Social Structure

- Matriarchal Society: Elephant herds are typically matriarchal, led by the oldest and often most experienced female, the matriarch. The matriarch is essential to the herd’s direction, making movement decisions, finding water and food sources, and protecting the group from threats.

- Family Units: Elephant herds are composed of closely related females and their offspring. Female elephants usually live with their natal herd, creating robust, multi-generational family units. Male elephants, on the other hand, leave the herd upon reaching adolescence and either live solitary lives or form loosely associated bachelor groups.

- Allomothering: Older females assist in caring for other people’s calves, a process known as “allomothering” in elephant cultures. This cooperative care enhances the survival rate of the young and allows mothers to feed and rest, ensuring the well-being of the entire herd.

- Social Bonds and Hierarchies: Elephants maintain solid social bonds through frequent physical contact, such as touching trunks, entwining trunks, and leaning on each other. Age, experience, and social bonds often determine the social hierarchy within the herd. The matriarch holds the highest rank, followed by other adult females and their offspring.

- Male Social Structure: After leaving the natal herd, male elephants spend more solitary lives. However, they occasionally associate with other males. These associations, known as bachelor groups, are usually fluid and based on factors such as age, size, and reproductive status. During musth, a period of heightened sexual activity and aggression, males become more competitive and may challenge each other for mating rights.

Habitat and Distribution

Elephants, the largest land mammals, inhabit Africa and Asia, each with unique habitats and distributions specific to African and Asian elephant species.

African Elephants

- Habitat: African elephants thrive in diverse environments, including savannas, forests, deserts, and marshes. They are incredibly adaptable, which allows them to live in varied climates, from the rainforests of Central Africa to the dry regions of the Sahel.

- Distribution: African elephants inhabit sub-Saharan Africa, with significant populations in Botswana, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Kenya, and South Africa. There are two subspecies of African elephants: the savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana), found in open grasslands and woodlands, and the forest elephant (Loxodonta Cyclotis), which inhabits the dense rainforests of Central and West Africa. These elephants’ distribution primarily influences factors such as the availability of food and water and human activities such as agriculture and urban development.

Asian Elephants

- Habitat: Asian elephants primarily inhabit forested regions, including tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests, dry deciduous forests, and grasslands. They depend more on forested environments than their African counterparts and are typically found in regions with dense vegetation providing ample food and cover.

- Distribution: The range of the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) extends across 13 countries in South and Southeast Asia, including India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia (Sumatra and Borneo). The largest populations are found in India, home to more than half of the world’s Asian elephants. Their distribution is increasingly fragmented due to habitat loss, human-elephant conflict, and poaching, resulting in isolated populations vulnerable to genetic bottlenecks and other conservation challenges.

Diet and Feeding Habits

Understanding diet and feeding habits provides insight into elephants’ ecological role as large herbivores in their ecosystems:

Elephants are herbivorous mammals with a diverse diet primarily consisting of vegetation. Their diet typically includes:

- Grasses: Elephants feed on various grasses, which form a significant part of their diet, especially in savannah and grassland habitats.

- Leaves and Foliage: They consume various leaves from different plant species. They browse on tree leaves, shrubs, and other foliage in their habitats.

- Bark: In some cases, elephants also consume bark from trees. They may strip bark with their tusks and consume the inner layers, especially during dry seasons when other food sources are scarce.

- Fruits: In season, fruits are essential to an elephant’s diet. They consume various fruits, such as berries, melons, and other fleshy fruits within their range.

Feeding Habits

Elephants are known for their constant need to feed due to their large size and energy requirements. Key aspects of their feeding habits include:

- Foraging: Elephants spend a significant portion of their day foraging for food. They grasp and manipulate vegetation using their trunk and may also use their tusks to help access certain types of plants.

- Water Dependence: Elephants require large amounts of water daily. They are known to travel long distances to find water sources and may spend considerable time bathing and drinking.

- Feeding Patterns: Elephants frequently adapt their eating habits according to available food and water sources. During periods of scarcity, they may adjust their diet or travel longer distances to find suitable vegetation.

- Social Feeding: Elephants are social animals and often feed in groups. This social behavior can sometimes lead to cooperative feeding and sharing of food resources within their herd.

- Digestive Process: Their digestive system is adapted to process rigid plant material. Its complex process involves fermentation in the large intestine to extract nutrients from fibrous plant material.

Intelligence and Cognitive Abilities

Elephants are amazing animals with exceptional cognitive and intellectual capacities. Here are some points:

- Complex Social Structures: Elephants live in matriarchal herds led by the oldest female, showing sophisticated social structures akin to human societies.

- Exceptional Memory: Known for their long-term memory, elephants can remember distant locations of water sources and pathways, which is crucial for survival in their habitats.

- Tool Use and Problem-Solving: Elephants demonstrate tool use, such as using branches to swat insects or digging for water in dry riverbeds, indicating problem-solving abilities.

- Communication and Language: They communicate through various vocalizations, infrasound (low-frequency sounds), and body language, suggesting complex forms of communication.

- Empathy and Emotional Intelligence: Elephants empathize with injured or distressed herd members, displaying emotional bonds and social cohesion within their groups.

- Self-Awareness: Studies, including mirror tests, suggest that elephants possess a self-awareness comparable to humans, recognizing themselves in reflections.

- Learning and Adaptation: They learn from experiences and can adapt to changing environments, demonstrating the adaptability of thought and the capacity for creativity in the face of difficulty.

- Problem-Solving Skills: In captivity, elephants have demonstrated their cognitive capabilities by solving puzzles and learning complex tasks.

- Numerical and Spatial Awareness: Elephants show numerical understanding, can distinguish between different quantities of items, and have a keen spatial awareness that aids navigation across vast territories.

- Creative Behaviors: Behaviors like creating protective sunscreens from mud or using tools in novel ways showcase their ability to innovate and adapt to their environment.

Cultural Significance of Elephants

Elephants symbolize power, wisdom, and cultural richness. They have spanned civilizations, from ancient warfare to ceremonial rituals, leaving an enduring legacy in human history and imagination.

1. Asian Elephants in Religious Contexts

- Hinduism: In Hindu mythology, Ganesha, the deity of wisdom, success , and the removal of obstacles, is often depicted with an elephant head, symbolizing knowledge and the power to overcome barriers.

- Buddhism: In Buddhism, the white elephant symbolizes mental strength, wisdom, and knowledge. It’s believed that Queen Maya, the mother of Buddha, dreamt of a white elephant before his birth, indicating his future greatness.

2. African Elephants

Folklore and Tribal Beliefs: African cultures view elephants as symbols of strength, power, and wisdom . People often portray them as wise creatures with spiritual significance in stories and myths.

3. Historical Roles

- War Elephants: Throughout history, elephants have been used in warfare by civilizations such as the Persians and Indians and later by Alexander the Great. Due to their size, strength, and ability to intimidate enemy forces, they provided a formidable advantage.

- Ceremonial Uses: Elephants have been central to royal and religious ceremonies in many cultures. In India, for example, they have been used in processions during festivals and important events, symbolizing grandeur and royalty.

Conservation Efforts and Challenges

The points highlight both the proactive measures and the ongoing challenges in the conservation of elephants globally:

- Habitat Loss: Human activities like agriculture, urbanization , and infrastructure development are causing elephants to lose much of their habitat.

- Human-Wildlife: Conflict arises when elephants encroach on human settlements, leading to retaliatory killings and habitat fragmentation.

- Poaching: People target elephants for their ivory tusks despite international bans on ivory trade. Poaching remains a severe threat to their survival.

- Legal Protection: International agreements to save elephants, like the CITES- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna, aim to control and limit the ivory trade.

- Conservation Reserves and National Parks : Establishing protected areas helps provide safe habitats for elephants and other wildlife.

- Community Involvement: Participating local communities in conservation initiatives helps lessen hostility between people and wildlife and encourages sustainable lifestyles.

- Research and Monitoring: Effective conservation measures require a thorough understanding of elephant behavior, migration patterns, and population dynamics.

- Transboundary Conservation Initiatives: Collaborative efforts between countries are essential, as elephants often move across borders for food and water.

- Climate Change: Factors including temperature extremes and shifting rainfall patterns can disrupt elephant habitats and food sources.

- Education and Awareness: Raising public awareness of the value of protecting elephants and their dangers can help mobilize support for conservation initiatives.

Human-Elephant Interaction

The complex dynamics of human-elephant interaction emphasize the need for sustainable conservation practices and ethical considerations in tourism and captive management.

Conservation vs. Human Development Conflicts

- Habitat Loss: As human populations expand, natural habitats are increasingly converted for agriculture , urbanization, and infrastructure projects, reducing elephant habitats.

- Conflict Over Resources: Elephants often compete with humans for water and food, escalating tensions and conflicts.

- Human-Elephant Conflict: Elephant raids on crops can lead to retaliatory killings by farmers, exacerbating conservation challenges.

Elephant Tourism and Ethical Considerations

- Tourism Impact: Elephant tourism, encompassing rides and performances, raises ethical and animal welfare concerns.

- Physical and Psychological Impact: Captive elephants used for tourism may suffer from physical ailments due to workload and improper care, and they may also experience psychological distress from unnatural living conditions.

- Educational vs. Exploitative Tourism: Balancing educational benefits for visitors with the ethical treatment of elephants remains a critical challenge.

Captive Elephants and Welfare Concerns

- Living Conditions: Captive elephants may face inadequate living conditions, confinement, and lack of social interaction, which can impact their physical and mental well-being.

- Training Methods: Traditional training methods such as “breaking” can involve harsh techniques that cause distress and pain to elephants.

- Legal and Regulatory Frameworks: Countries vary in their regulations governing captive elephants, influencing their welfare standards and treatment.

Elephants stand as majestic icons of cultural heritage and biodiversity conservation. Their symbolic significance spans civilizations, embodying wisdom, strength, and spirituality. However, their survival faces challenges from habitat loss, poaching, and human-wildlife conflicts. Conservation efforts must balance ecological needs with human development, emphasizing sustainable practices and ethical considerations in elephant tourism and captivity. As ambassadors of wilderness, elephants urge us to safeguard their habitats and respect their intrinsic value in our shared ecosystem. Preserving elephants means safeguarding a species and the integrity of our planet’s natural heritage for future generations.

*Please provide your correct email id. Login details for this Free course will be emailed to you

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy .

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Web Development & many more.

Forgot Password?

This website or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and required to achieve the purposes illustrated in the cookie policy. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to browse otherwise, you agree to our Privacy Policy

Explore 1000+ varieties of Mock tests View more

Submit Next Question

🚀 Limited Time Offer! - 🎁 ENROLL NOW

- Safari ideas

- Special offers

- Accommodation

- Start planning

- Booking terms

- Great Wildebeest Migration

- Gorilla trekking

- Chimp trekking

- Finding wild dogs

- Beaches and lakes

- Luxury safari

- Malaria-free

- Food & wine

- Other experiences

- When to go on safari - month by month

- East or Southern Africa safari?

- Solo travellers

- Women on safari

- Accommodation types & luxury levels

- General tips & advice

- All stories

- Afrika Odyssey Expedition

- Photographer of the Year

- Read on our app

- Collar a lion

- Save a pangolin

- Guarding tuskers

- Rules of engagement

- Job vacancies

- Ukuri - safari camps

Elephant body language 101 – a guide for beginners