Stuart Weitzman School of Design 102 Meyerson Hall 210 South 34th Street Philadelphia, PA 19104

215.898.3425

Get Directions

Get the latest Weitzman news in your Inbox:

Excerpt: 'the landscape project'.

Subscribe to e-News

- Landscape Architecture

- Weitzman News

Michael Grant [email protected] 215.898.2539

The Landscape Project is the latest publication from the Department of Landscape Architecture . Launched this fall, it brings together 18 provocative essays by 20 members of the faculty on the myriad ways landscape architects today engage with agriculture, energy, water, urbanism or another issue through the agency of design—and how they could do so in the future. In this essay from the book, titled "Purpose," alums Rebecca Popowsky (MArch’10, MLA’10) and Sarai Williams (MCP’17, MLA’17) discuss new modes of practice and developing models of professional structures in the landscape architecture field. Popowsky, a lecture in landscape architecture, is a landscape architect and research associate at OLIN , where she leads the firm’s research and development group, OLIN Labs . Williams is also a lecturer in landscape architecture and is on the social impact real estate team for Community Solutions , a national nonprofit working with cities to create a lasting end to homelessness. The Landscape Project, edited by Richard Weller, Meyerson Chair of Urbanism and professor and chair of landscape architecture, and Tatum Hands, editor in chief of LA+, is available from Applied Research & Design/ORO Editions , and is expected to begin shipping in January. Purpose The widening gap between the changes that must be made in the built environment and those that can be made through conventional models of professional design practice is driving a generation of landscape architects, architects, and planners to search out and create new modes of practice. In this essay, we describe aspects of this emergence within the current structures of professional landscape architectural practice and discuss several landscape architecture and planning practices that present potential to expand the scope, and in some cases, challenge the foundations of these existing structures. To paint a clear picture of current professional landscape architectural practice, it may be helpful first to describe an analogous professional services model that is more widely familiar – that of law, which has well-established models for public interest practice. Law school prepares would-be lawyers to analyze and apply statutes, regulations, and case law, but generally does not prepare students to become agents of social good. However, the profession has addressed the need to put the law to positive use by creating public interest and government practice models, giving practicing lawyers the opportunity—or obligation—to handle pro bono cases. Non-governmental public interest lawyers who work for groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) work to advance societal goals and are generally supported by public and private grants and private donations. In comparison, the landscape architecture profession has a very small government sector, almost no pro bono mechanism, and no formal public interest sector at all. One obvious reason for this difference is the relative size of the profession–while there are about 800,000 licensed attorneys in the US, the Department of Labor estimates the number of professional landscape architects to be under 25,000. Another reason is that landscape architects haven’t effectively communicated the societal value of the profession to the general public, so little public and philanthropic funding is directed to landscape architectural services. While legal services are widely seen as critical to the protection of individual and community rights, design services (especially in landscape) are more often seen as an unnecessary luxury. However, when the impact of the design of the built environment on issues of social justice and public health is appreciated—especially in a time of extreme climate change and widening inequality—the landscape project should be recognized as an essential service. Absent a source of substantial funding for public interest landscape architecture, landscape architects must themselves build a structure that allows this essential service to be advanced within or alongside the existing practice model. While comparison to analogous fields such as law is helpful, it is important to draw some distinctions that might otherwise be overlooked. One is the distinction between pro bono work and public interest work. State bars set minimum pro bono (or unpaid work) requirements for lawyers, embedding a measure of social obligation into the legal profession. While this certainly has a positive impact at scale (and is something the Council of Landscape Architectural Registration Boards—the licensing body for landscape architects—should consider implementing), pro bono work within private practice generally cannot make serious headway on complex societal or environmental problems. In contrast, public interest legal organizations, such as the NAACP or the ACLU, which support full-time professionals and are expressly established for this purpose, play a significant role in delineation of fundamental civil rights. In this essay, we will refer to both pro bono and public interest work as “purpose-driven” work. This term is used in contrast to “profit-driven” to indicate that the primary goal of a project or practice is societal or environmental benefit rather than private economic gain. A similar distinction should be made between overhead and overtime. In the absence of substantial public interest design funding, purpose-driven work is often non-billable, unfunded, or under-funded. In order for an individual practitioner to take on unfunded work, they may need to perform the work outside of “work hours,” that is, at night or on the weekends. This can be considered overtime. If, on the other hand, a design firm decides to take on non-billable public interest work, that work may be completed during work hours and the cost to the firm can be considered overhead. The key difference is that overhead cuts into profit, while overtime cuts into employee or individual personal time. The scale of work that can be done using either overhead or overtime is limited by the budgetary and time constraints of practices and individual practitioners. To push beyond these limits, external funding is required. Architecture and landscape architecture, like law, are service professions. Design services are commissioned by clients, within a defined scope, for a fee. Design commissions (usually referred to as projects) typically present themselves to design professionals as Requests for Proposals (RFPs). RFPs are issued when three puzzle pieces come together: first, recognition of a need or demand for a built project; second, funding for planning, design, and construction; and third, an individual or number of individuals who have the power and authority to implement the project. When these factors align in a location (project site) an RFP is issued and a design professional can be commissioned to articulate a material form that meets the needs of the project within constraints defined by funding, site, and political, social, and ecological contexts. This model, which might be called the design-commission model, the RFP model, or the client-driven model, can lead to immensely successful built work that provides equitable social, environmental, and economic benefits. However, the good that comes out of any given project depends more on the political, social, and economic context and forces that pre-date the RFP, than on the resulting design actions. In other words, by the time the designer is hired, the overarching impact of the project is largely already set.

Practitioners are compelled to establish new structures to support their work, while also providing design services.

To subvert the conventional role of the designer in this design-commission model, projects need to be instigated in the absence of an RFP. Sometimes this means that no client exists; other times a client group has identified a project need, but they do not have access to funding or decision-making authority; in other cases, needs or problems exist on a site but they have not yet been clearly articulated. Practitioners are experimenting with several mechanisms to support project instigation outside of RFP or client-driven scenarios. For example, grant funding, pilot projects, and “communities of practice” support important work outside of, or in addition to, traditional project models. The following cases are helpful in exploring how these mechanisms interface with projects and communities. Public and philanthropic funding mechanisms such as grants and fellowships are commonly used by designers to support purpose-driven work. Innovative firms have honed their ability to seek out and secure research or seed grants, often in collaboration with academic or institutional partners to support design research and action. Mahan Rykiel Associates, a landscape architecture practice based in Baltimore, for example, has initiated a series of research-based projects around beneficial reuse of dredge material in the Chesapeake Bay, with grant funding from the Maryland Department of Transportation and the Maryland Port Administration and in partnership with researchers at Cornell and the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. Outcomes of this research-based initiative have included public engagement and education workshops, experimental seed germination studies, and a site-specific pilot installation, all aimed at reimagining Baltimore Harbor sediment as an essential resource, rather than a waste material. As in this example, grant-funded work often builds upon itself, moving from “proof of concept” research to small-scale pilot installation, and eventually to large-scale implementation. Merritt Chase, a young practice cofounded by Nina Chase and Chris Merritt, has honed a capacity to move a design agenda forward using pilot-based advocacy projects. They make the case for public space as the foundational building blocks of communities, and for landscape architects to occupy a seat at the table “further upstream” in the process of planning for change (prior to the issuance of the RFP). This compels them to focus much of their attention on short-term design-build projects that aim to build momentum for design ideas. Their “tactical urbanism” projects are about making things that build enthusiasm for longer term investment in the urban landscape. For example, Birch Street Plaza, in Boston’s Roslindale Village, which turns a trafficked street into a pedestrian plaza, began as a six-day pop-up plaza that prototyped and tested design elements using duct tape, milk crates, and wooden dowels. In this case, the pilot project was used largely as a community engagement mechanism that facilitated in-person and online surveys, observation, and conversation that shaped the final plaza design. Sponge Park on the Gowanus Canal, designed by DLANDstudio is another example of a small-scale pilot project that is intended to pave the way for large-scale transformation. The park is a modular street-end installation that intercepts and filters stormwater while providing accessible neighborhood green space. DLAND worked with the Gowanus Canal Conservancy to pull together funders and public agencies over a multi-year process to get the $1.5 million demonstration project implemented. The pilot project demonstrates the effectiveness of nature-based stormwater management and aims to garner public support for large-scale transformation along the full length of the canal. While each of these firms found creative ways to leverage alternative funding mechanisms to instigate built projects, another practice, Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI), used similar mechanisms to support research into building innovative business models. Seed funding allowed the firm’s founding members to explore mission-based business models in other fields, before establishing KDI as a non-profit design firm. Based in Los Angeles and Nairobi, KDI balances grant-funded work with traditional client commissions and a small amount of donor funding. The practice model includes hiring local experts in various fields, including design, engineering, and construction, locally, for projects in Africa and the US while serving communities that lack political and economic clout. In this instance, the structure of the firm is as innovative as their design work

In our research interviewing several of these innovative practitioners, common themes emerged. Practitioners are looking for ways to bring new voices to the table at all stages of the design process; if the people most in need of design services cannot participate substantively in the process, the process will not be fair or just. Practitioners are also looking for ways to ensure that the voices heard within the profession reflect the communities the projects are meant to serve; otherwise, projects will not fully meet community needs. Specifically, community input must be more than obligatory steps taken to smooth the way for development, or for the superimposition of a single designer’s vision. Opening the design process to multiple voices and reorienting design services toward communities in need represents a paradigm shift in contemporary design culture. To support this type of community-oriented work, landscape architects must take advantage of alternative funding mechanisms and collaborative structures. Another common sentiment among these practitioners is that working outside of the typical client-commissioned design model adds layers of complexity and cost that are borne by firms and individual practitioners. They talk about the need to be open to “failing forward”; in other words, missteps are part of the process and should be seen as opportunities to reexamine approaches or refine or adapt objectives. Leaving established professional structures behind is an unruly and risky business. Practitioners are compelled to establish new structures to support their work, while also providing design services. As a community, we can do more to collectively support this kind of work through education and skill-building and by building networks of support among practitioners. In addition to non-traditional funding mechanisms, purpose-driven work can be supported by formal or informal social infrastructures that make space for open-ended collaboration and design exploration. “Communities of practice” (CoP) were defined in the 1990s by educational theorist Etienne Wenger as “a group of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis.”(1) The CoP model is different from a typical professional organization or institution, in that involvement is voluntary and not project- or profit-oriented. Communities of practice are commonly housed within businesses, though they can also function outside of (or bridge across) formal institutions. While big corporations like Ford and IBM use the model as a formal platform for innovation, problem-solving, and driving change, this type of social infrastructure is not often discussed in the design industry. OLIN Labs is an example of the community of practice model housed within a private firm. Five topic-based “Labs” (Eco, Build, Tech, People, and Design) host regular meetings among designers at all levels across the firm in conversation around topics of shared interest. This model, which is internally funded and relies on voluntary staff participation, creates space within the workday for designers to identify research and design projects outside of the RFP pipeline, and work together with colleagues and external collaborators to find creative ways to bring those projects into being. Discussions that grow out of the Labs’ communities of practice sometimes turn into opportunities for informal learning, and other times become freestanding research or advocacy initiatives or pilot projects that can attract grant or client funding. The belief here is that robust communities of practice may offer routes to purpose-driven and impactful design action. Other examples include WxLA and The Urban Studio. WxLA, organized by Gina Ford, Jamie Maslyn Larson, Rebecca Leonard, and Cinda Gilliland, is not firm- or project-specific (Ford, Larson, Leonard, and Gilliland all run their own firms) but brings practitioners together around the goal of gender equality in the profession. Initiatives, such as the WxLA annual scholarships, grow out of this shared mission and community-based infrastructure. The Urban Studio initially arose from a collaboration among Landscape Architecture Foundation Leadership and Innovation Fellows and then grew into a team of practitioners organized around a shared cause, bridging firms, that, in addition to paid consulting work, take on co-design and co-creation workshops in communities of color. In contrast to the traditional for-profit design firm model, The Urban Studio exists primarily as a platform for collaboration among professionals. They convene industry-wide conversations through their annual Cut/Fill “unconference,” relying on donor funding from mission-aligned design firms and industry partners. The studio also brings together practitioners from other firms to take part in career discovery workshops in underserved communities. In both instances, communities of practice provide social infrastructures that challenge the profession to more equitably reflect and represent the populations that we serve. Skills that would facilitate non-conventional practice scenarios such as grant-writing, community organizing, research methods, policy analysis, and business planning, are not generally considered central to design curricula. At some schools, students have the chance to learn these skills by taking part in public-interest work through university-backed centers that hire students as researchers or designers either during the school year or over the summer. Upon graduation, however, emerging design practitioners tend to perceive their career path as one they walk alone. Visual artists are accustomed to the idea that attracting an audience and building collaborative platforms through which their art will be displayed, are as critical to successful practice as the production of art. Artists, who have to not only invent their own projects but then find ways to fund them, hone skills in grant writing and pitching projects to potential patrons, searching for seed funding while communicating their ideas on multiple levels so as to build their reputations as emerging practitioners. If design education is to support emerging forms of practice, a similar set of skills will need to be foregrounded. Even as individual firms and practitioners are finding creative ways to reimagine professional practice models, the field of landscape architecture currently lacks sufficient shared infrastructure to support industry-wide transformation. Rather, efforts to challenge the conventional role of design are ad hoc and rely heavily on voluntary sacrifice on the part of firms and practitioners through nonbillable overhead or unpaid overtime. Frustration among practitioners, students, and academics with the limitations of professional landscape architectural practice is high. If we’re honest with ourselves, we would likely find that the great majority of landscape architects would prefer to work in public-interest scenarios, rather than on projects that primarily support private interests. The problem is that the field lacks robust professional structures that make this type of work sustainable at scale over the long term. Practitioners who are actively trying to get purpose-driven work done (outside of university or government structures) are faced with the difficult task of building the stage that they are performing on, while convincing a non-existent audience to show up and pay attention. Landscape architecture, like architecture, is a very challenging profession even for those practitioners who “just” work on conventional design commissions. Doing anything even slightly outside of that realm is even more difficult, and it can be risky (professionally and financially) without robust support structures. Current and future landscape architectural practices will need to take on the unruly challenge of building these structures cooperatively, if we want to be relevant in the coming decades. To help achieve this we can look to practical precedents such as formalizing a pro-bono system in landscape architecture, building our capacity in government, and also more seriously considering the way in which artists and the not-for-profit sector invent, promote, and build coalitions for their projects. 1) Etienne Wenger, Richard A. McDermott & William Snyder, Cultivating Communities of Practice: A guide to managing knowledge (Harvard Business Press, 2002).

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Publications

From "The Landscape Imagination" - James Corner's Essay on the High Line

- Written by Connor Walker

- Published on June 19, 2014

The following is an excerpt from The Landscape Imagination: The Collected Essays of James Corner 1990–2010 by James Corner . In this passage, Corner discusses the work of John Dixon Hunt , and the qualities of Hunt's work that he seeks to incorporate into his own (including his firm's - James Corner Field Operations - redesign of the New York High Line ).

Over the past two decades, James Corner has reinvented the field of landscape architecture. His highly influential writings of the 1990s, included in our bestselling Recovering Landscape , together with a post-millennial series of built projects, such as New York's celebrated High Line , prove that the best way to address the problems facing our cities is to embrace their industrial past. Collecting Corner's written scholarship from the early 1990s through 2010, The Landscape Imagination addresses critical issues in landscape architecture and reflects on how his writings have informed the built work of his thriving New York based practice, Field Operations.

Hunt’s Haunts: History, Reception , and Criticism on the Design of the High Line

By “Hunt’s Haunts,” I am referring to the writings of John Dixon Hunt and the many discussions I have had with him over the years that have lingered with me in ways deeply enriching and, at the same time, oddly disquieting. After all, good criticism and difficult conceptual frameworks inevitably pose a challenge—one that can often agitate and haunt one’s sense of direction if left unresolved.

This same point regarding the reception of fecund and challenging ideas could also be said of some of Hunt’s favorite physical haunts—some of the great gardens and places from which he has derived inspiration and about which his work is focused. Such places include Stowe, Stourhead, Bomarzo, the melancholic and hidden gardens of Venice, and the many others that have gifted him the feeling of a “greater perfection.” As he has written, such places are “haunted by undeniable spirits, [wherein] the environment can become landscape.” By spirits, of course, he refers not to some mystical essence but rather to the human mind—to the imagination, to the fictions and designs that create a place of lasting presence, a presence that inevitably haunts precisely because of effects that tend to linger and escape any form of easy definition.

Good gardens haunt precisely because they inevitably exceed being thought. This phenomena of haunting excess—both as place and idea, and as developed through Hunt’s writing on the subject—is both inspiring and elusive. It is a fascinating and fundamental topic of all art. Outlined here are three recurrent haunts in Hunt’s work that I find particularly relevant for my own. In this context, I will use some images of the High Line project to suggest a certain striving in real-world practice to try and approximate certain ideas.

First, is Hunt’s work on site, the haunts themselves. Hunt has constructed an almost unassailable argument that the specificity of sites lies at the very core of any significant works of landscape architecture. In this vein, he has elaborated on key concepts such as the “genius of the place,” “reading and writing the site,” “placemaking as an art of milieu,” “site mediation,” and the nesting of “three natures” wherein the garden (third nature) is a focused concentration of its larger surroundings. A close reading of a particular site’s attributes—its history, its various representations, its context, and its potentials—conspires to inform a new project that is in some way an intensification and enrichment of place. Every site is an accumulation of local forces over time, and so, Hunt argues, any significant design response must in some way interpret, extend, and amplify this potential within its specific context. Averse to universal and stylistic approaches to design, Hunt demands inventive originality with regard to specific circumstance. In the case of the High Line , a very close reading was made of the site’s history and urban context. Two readings were particularly formative—one was the singular, autonomous quality of the transportation engineering infrastructure (its linearity and repetition, indifferent to surrounding context, and its brash steel and concrete palette), and the other was the surprising and charming effect of self-sown vegetation taking over the postindustrial structure once the trains had stopped running—a kind of melancholia captured beautifully in earlier photographs made by the artist Joel Sternfeld. These photographs were later used to great effect by those who sought the preservation of the structure in the face of impending demolition.

The new design of the site, from its material systems (the lineal paving, the reinstallation of the rail tracks, the plantings, the lighting, the furnishing, the railings, etc.) to the choreography of movement; the meandering of paths, the siting of overlooks and vistas, and the coordination of seating and social spaces, is intended to reinterpret, amplify, dramatize, and concentrate these readings of the site. The design is highly site-specific; it is irreproducible anywhere else without significant loss of origin and locality, partly owing to the history of the High Line itself, and partly to the unique characteristics of its urban context and adjacencies. The design aims to concentrate these found conditions, to dramatize and reveal past, present, and future contexts, and to create a memorable place for all who visit.

This brings me to a second theme of Hunt’s Haunts, the concern for reception. Over the past few years, Hunt has brought into sharper focus the importance for how a visitor receives a given work—how they experience, understand, value, and extend various interpretations of the work. He says that “landscape comes into being as the creative coupling of perceiving subject and an object perceived.”

As a landscape architect, it is very difficult to believe that a designed work can determine a particular behavioral response; a good designer can at best influence, steer, or guide a particular set of responses, but can never overdetermine or script reception. Hunt recognizes such a distinction in statements, such as, after W. H. Auden, that “a poet, especially a dead one, cannot control how we read and understand his poetry, but that—especially if it is good—we will constantly reread it in new ways; so even when later generations repeat the very same words that W. B. Yeats originally published, they will probably give them new meanings and new resonance.” He continues the analogy: “When we are dealing with materials in a garden that have neither denotative basis (as words do in the first instance) nor precise declarations of idea or emotion, there is considerably more scope for reinvesting them with meanings, for seeing them in different ways than were originally intended or anticipated.” Thus, he suggests that a good design must harbor sufficient room for a wide range of receptions and interpretations, if not actually instigate, prompt, and support open and indeterminate readings. As he quite rightly points out,

here is the palpable, haptic place, smelling, sounding, catching the eye; then there is the sense of an invented or special place, this invention resulting from the creation of richer and fuller experiences than would be possible, at least in such completeness or intensity, if they were not designed. Like cyberspace, a designed landscape is always at bottom a fiction, a contrivance—yet its hold on our imagination will derive, paradoxically, from the actual materiality of its invented sceneries.”

From such ideas, Hunt develops the concept of the longue durée , the long duration, the slow accrual of experience and meaning over time. Possibly one of the most fundamental, important, and difficult criteria for landscape architecture is the fact that the medium is bound into time. There can be no immediacy of appreciation, no fast way to consume landscape in any meaningful or lasting way. Landscapes can never be properly captured in a single moment; they are always in a process of becoming, as in a temporal quarry of accrual and memory collecting experiences, representations, uses, the effects of weather, changes in management, cultivation and care, and other traces of layered presence. In the case of the High Line , the experience of strolling is intentionally slowed down in the otherwise bustling context of Manhattan. Paths meandering in between tall perennial and grass plantings create an experience that can not really be properly captured in a photograph, or even video. Like so many other gardens, the place must be walked, with scenes unfolding in sequence and in juxtaposition. The dynamic plantings are different from week to week, with varied blooms, colors, textures, effects, and moods, combined with the changing light at different times of day, varied weathers and seasons, and with the different microclimatic effects of the surrounding cityscape. The visitor is almost always experiencing the High Line in newly nuanced ways.

Importantly, the design does not employ signs or symbols of narrative intent, it does not try to tell a story or to embed meaning—rather, its very materiality, its detailing, its artifactuality elicits or prompts different associations and readings. Hunt has spoken in numerous essays of triggers and prompts in design, describing a number of theatrical devices such as entry thresholds and liminality, the passage from outside to inside, dramatic frames and scenes, displacement and collage, inscription and marking. These precisely designed triggers and prompts are all concentrations of effect that draw the visitor into another world, heightening the allure and distinctiveness of a special place. The visitor becomes as much a performer as viewer, more deeply engaged in participating in the theatricality of urban life—the promenade as elevated catwalk, urban stage, and social condenser.

And here words bring us to the third haunt of Hunt, the critical. When he declares that “to theorize about gardens is justifiable for its own sake; moreover it increases the pleasures of understanding,” he is establishing the basis not simply for passive contemplation but for actively energizing fresh developments in the ideas and practices of landscape architecture. His insistence on historical perspective is well taken, but his commitment to concepts, to critical discourse, to informed argumentation, and—most important—to cultural enrichment through imaginative and inventive placemaking continues to challenge us all.

Hunt’s haunts are quite simply those remarkable places and ideas where content concentrates, lingers, and accrues. The combination of physical, material places with cultural ideas points to the unity of theory with practice, of design with reception, and of experience with intellect, all dialogues that we strive for in the best of our work. That such experiences might also haunt our imaginations is perhaps the highest calling of art, and in gardens, as Hunt has so eloquently taught us, we might find the greatest perfections.

Table of Contents

Preface — James Corner

Introduction — Alison Bick Hirsch

Critical Thinking and Landscape Architecture, 1991

Sounding the Depths—Origins, Theory, and Representation, 1990

Three Tyrannies of Contemporary Theory, 1991

Recovering Landscape as a Critical Cultural Practice, 1992

2 Representation and Creativity

Aerial Representation: Irony and Contradiction in an Age of Precision, 1996

Drawing and Making in the Landscape Medium, 1992

The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique, and Invention, 1999

Eidetic Operations and New Landscapes, 1999

Ecology and Landscape as Agents of Creativity, 1973

3 Landscape Urbanism

Not Unlike Life Itself: Landscape Strategy Now, 2004

Landscape Urbanism, 2003

Landscraping, 2001

Terra Fluxus, 20064

Practice: Operation and Effect, 2010

Botanical Urbanism, 2005

Hunt’s Haunts: History, Reception, and Criticism on the Design of the High Line , 2009

Afterword — Richard Weller

Acknowledgments

Complete Bibliography of James Corner

- Sustainability

世界上最受欢迎的建筑网站现已推出你的母语版本!

想浏览archdaily中国吗, you've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

Seeing landscape architecture as part of our nation’s essential infrastructure only deepens its relevance today

- Mass Timber

- Trading Notes

- Outdoor Spaces

- Reuse + Renewal

- Architecture

- Development

- Preservation

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- International

Landscape as Infrastructure

The following editorial from Thomas Woltz advances the responsibility of landscape architects to create a cleaner, greener, and more equitable future as urban populations swell and the impacts of climate change put current defenses to the test. This alliance with infrastructure serves as a fitting lead-off for the Focus section of the October/November edition of The Architect’s Newspaper themed on landscape. Along with a review of Kevin Loughran’s Parks for Profit: Selling Nature in the City and a fabric-focused Pictorial, this section showcases a quartet of city-bound projects—three in the San Francisco Bay Area and one in the heart of Manhattan—that, while diverse in scale and scope, bring resiliency, biodiversity, and natural beauty to the forefront. Keep an eye out for these pieces in the coming days. —The Editors

The upcoming need for infrastructural investment in the United States is an extraordinary opportunity for the community of landscape practitioners . There is powerful potential in the alignment of infrastructural needs with the design community’s tools to creatively address some of the most pernicious issues facing our society today, including an interrelated set of social, cultural, and environmental crises. The rapid decline in biodiversity, increase in climate extremes, and social disenfranchisement of minority communities, coupled with failing infrastructure, are urgent issues that should be front of mind in reimagining the critical networks of our world and our nation. The best solutions will be found within innovative collaborations across disciplines that align the engineered, ecological, cultural, and social.

In recent years, landscape architects have delivered compelling projects that punch above the typical response of engineered solutions by utilizing multidisciplinary design approaches with multivalent goals. Rather than simply capping an interstate, OJB established a thriving public landscape in a dense urban area of Dallas. Field Operations’ Tunnel Tops projects in San Francisco’s Presidio, which opened this year , yield a substantial link between the Drill Field of the Presidio and Crissy Field Park by Hargreaves Associates along the shore, designed in 1990. These projects reimagine transportation infrastructure to deliver generous urban experiences that encourage new forms of community, gathering, and celebration.

Too often parks are seen as empty land, “green space,” a tabula rasa, ripe for development rather than recognized as essential contributors to urban life. Memorial Park , Houston ’s largest park, consists of 1,500 acres of forest, river, and prairie, much of which was once inaccessible to the public, owing to nearly a century of neglect and lack of investment. During World War I, the site was Camp Logan, a training ground for soldiers preparing for battle. (The race relations of the era heightened tensions between Black soldiers and white local police officers, culminating in a riot in 1917.) At the end of the war, a prominent Houston family suggested that the camp become a public landscape, envisioning it as a memorial to the soldiers who trained there. Without a plan, however, it was treated as a wilderness park, untended, with athletic facilities scattered haphazardly across its expanse. In the 1950s, an ill-conceived infrastructure project split the poorly tended park in two when six lanes of roadway were built.

In 2012, after four years of severe drought, the park faced another devastating blow: Up to 80 percent of the forest canopy died, providing the wake-up call the city needed to rebuild its largest public landscape. Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects was hired in 2013—and after two years of community input and design work, the firm presented a comprehensive vision for the next 20 years of enhancing the park’s current assets; creating new public destinations; and addressing major infrastructural needs of parking, water quality, stormwater management, resiliency, biodiversity, and connectivity.

A collaborative design approach in an urban landscape of 1,500 acres can address environmental infrastructure at scale and in layered and powerful ways. Goals for Memorial Park included cleaning stormwater, storing water for irrigation, mitigating flood damage, restoring biodiverse native prairie and forest communities, re-establishing wildlife connectivity, and reducing the heat island effect. Of equal importance, but perhaps less evident, is the stewardship of cultural landscape resources alongside the ecological assets, revealing the stories of the peoples who have occupied and used this land over centuries. From the Karankawa people, Spanish settlers, and westward expansion to World War I and the modern day, the design of each project within the park entwines ecological and cultural revelation with the human experience of the landscape.

Opened to the public in 2021, the Eastern Glades , a 100-acre section of the park, combine sustainable parking design, stormwater mitigation, wetland conservation, and forest restoration with new amenities for park users. A newly constructed five-and-a-half-acre lake captures and treats stormwater and in the process offsets millions of gallons of potable water to address the irrigation needs for large areas of the park. Architectural interventions of gates, piers, pavilions, and terraces offer clues that acknowledge the military history of the site, and extensive trails engage visitors in the diverse restored ecosystems and cultural landscapes. These new amenities demonstrate the successful integration of sustainable initiatives without renouncing the consideration of the human experience in large-scale infrastructure.

Perhaps the most ambitious project from the comprehensive plan for Memorial Park is the highly complex 100-acre Land Bridge and Prairie Project , which will open to the public in December. This infrastructure project builds on the precedents of Dallas’s Klyde Warren Park and the Presidio Tunnel Tops to deliver a multilayered landscape of green infrastructure, stormwater management, and human and wildlife connectivity. Four tunnels made of high-performance concrete shells accommodate traffic while supporting two earthen plateaus, rising to about 35 feet above grade, that offer sweeping views of the Houston downtown and uptown skylines. On the Western Mound, interventions at ground level reveal information about the surrounding native ecosystems as they carry visitors to these vantage points, and at the top, nearly 1,000 linear feet of benches foster impromptu public performance and interaction, while designed elements reveal solar alignments during the equinoxes and solstices.

Ecologically, the project establishes nine acres of native savanna and 45 acres of Gulf Coast prairie that filter stormwater before slowly releasing it into Buffalo Bayou. Under the direction of the Memorial Park Conservancy , native seeds from local prairie fragments were collected and cultivated over the past four years to be used in the project, making this an extraordinary precedent of urban prairie restoration. Throughout this infrastructure project, the human experience is enriched through carefully presented details about the history and ecology of the site, through newfound vistas across the land, and through meaningful immersive experiences in native Texan ecologies.

The potential for this level of positive impact on biodiversity and the human experience lies latent in every major infrastructure engineering project of the day. It is paramount that the landscape and architecture design communities lead the way in rethinking our urban systems. The tools of design are powerful. If they are wisely applied, we can put the “public” back into “public works.”

Thomas Woltz is principal of Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects .

TEN x TEN integrates community needs with experimental methods

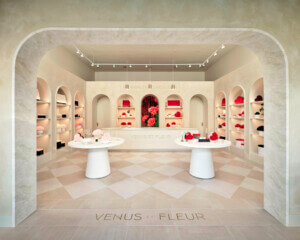

Ringo Studio looks to romantic and classical architecture for Venus et Fleur’s Houston outpost

HILLWORKS encapsulates the holistic shift in the design world toward environmental stewardship

UNITING THE BUILT & NATURAL ENVIRONMENTS

The landscape imagination.

As the author of canonical texts — and now built projects like the High Line in New York City — James Corner, ASLA, founder of Field Operations , has achieved a unique stature in contemporary landscape architecture. The Landscape Imagination: Collected Essays of James Corner, 1990-2010 , a new collection of his written work, thus serves as a sort of mid-career retrospective. The book brings together the bulk of Corner’s writings over the last two decades — from the early theoretical arguments of a young academic struggling to move the discipline beyond Ian McHarg’s ecological determinism, to an eminent practitioner discussing his major public parks.

Corner’s initial contributions to landscape theory lean heavily on Heidegger and hermeneutics, giving intellectual weight to Corner’s mission to rescue landscape architecture from a period of stagnation and seeming irrelevance to contemporary culture. “In a globalized context of rapid and expedient production,” Corner writes, “landscape must appear an antiquated medium and, its design, a fringe activity sustained through the eccentric passions of a handful of romantics and nature-lovers.” That landscape architecture would never appear so today is the result of a shift Corner contributed to in a fundamental way.

Corner’s writings on representation and landscape urbanism chart new and exciting territory for the field. Some of Corner’s essays are classics and mainstays of landscape architecture syllabi. In this volume they appear all together and accompanied by full-color images.

Rather than the concrete arguments found in books like Corner’s Recovering Landscape (1999) or Charles Waldheim’s Landscape Urbanism Reader (2002), to which Corner contributed, The Landscape Imagination follows Corner’s evolving concerns. These extend from drawing and mapping both in and as design — to the role of landscape in and as urbanism.

Always in tension are the landscapes of the mind and the site. But Corner seeks to defy and transcend these distinctions as he expands landscape’s conceptual scope. Corner focuses on ecology while also emphasizing landscape as a cultural project dealing in meaning, creativity, and imagination — hence the title of the collection. He shows us the through-line from theory to practice.

The more recent texts focus on built or proposed projects by Corner’s firm Field Operations. “Critical experimentation in action,” Corner calls them. They are the works of a mature practitioner and landscape visionary, whose intellectual rigor and influential practice have set the terms for landscape in contemporary life.

Read the book .

This guest post is by Mariana Mogilevich , PhD, assistant professor, metropolitan studies program, New York University.

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from the dirt.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Landscape Design Essay Examples and Topics

Concept of japanese gardens.

- Words: 2484

Designing a Playing Field for Putt-Putt Golf

Discussion against the construction of marvin nichols reservoir, landscaping problems at the university, the role of zoning in urban development.

- Words: 2176

Landscape Architecture and Spatial Analysis

- Words: 1105

Diana Balmori as One of the Most Prominent Landscape Designs

- Words: 1361

Renaissance Changes in the Garden Design

Edith wharton: her influence in gardens, architecture and interior decoration.

- Words: 4120

Palm Walk at Arizona State University

- Words: 1238

Re-Imagine New York. Central Park by Olmsted & Vaux

Postman’s park in london.

- Words: 2037

The Gates by Christo and Jeanne-Claude in New York

“a leed-inspired model for landscapes” by nieminen, colonial revival gardens: phenomenon features, lancelot capability brown and his landscape gardens, thomas church’s garden design in architecture, japanese zen garden and its philosophy, italian renaissance gardens and their significance, yarra river valley park and finns reserve landscape analysis.

- Words: 1399

Yellowstone National Park

- Words: 1151

Plantscape in Mason Office Building

Jorge alderete life and designer career, landscape movement history, sacred gardens and landscapes, fletcher steele role in modern day garden design.

- Words: 1389

Landscape Urbanism: A Medium to Modern Cities

The royal botanic garden.

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

UConn Today

- School and College News

- Arts & Culture

- Community Impact

- Entrepreneurship

- Health & Well-Being

- Research & Discovery

- UConn Health

- University Life

- UConn Voices

- University News

April 3, 2024 | Anna Zarra Aldrich, College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources

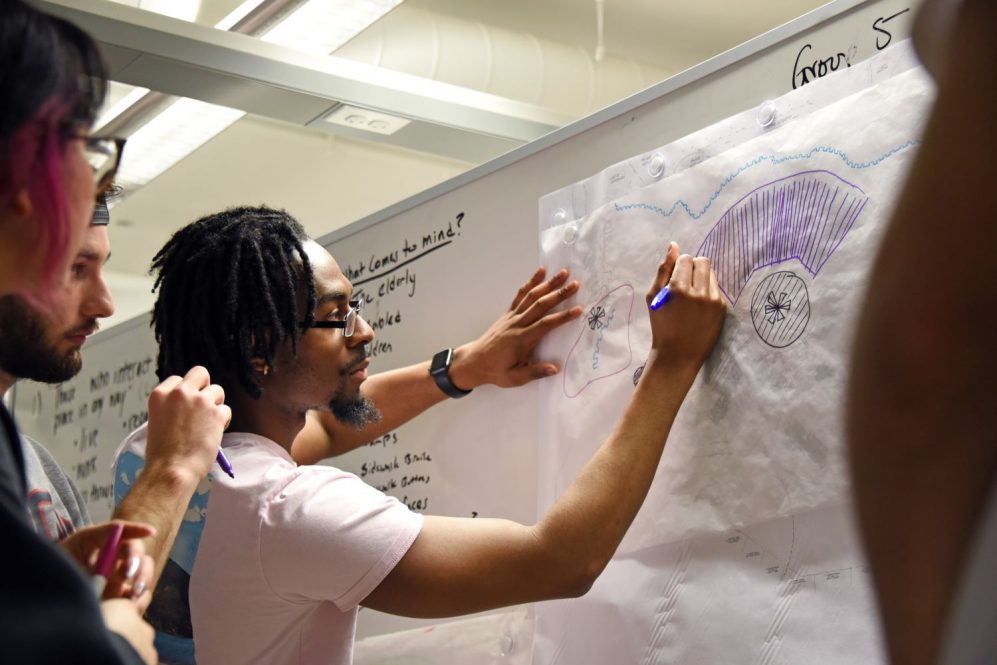

Vertical Studio Model Fosters Collaboration between Landscape Architecture Students

'The value of incorporating the vertical studio is that constant reminder to students that what they’ve learned in the previous class isn’t forgotten, it’s added'

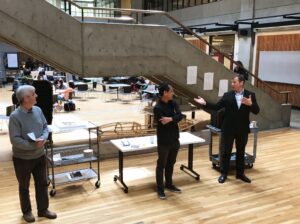

Landscape Architecture students learn in an environment that mimics professional design firms. (Jason Sheldon/UConn Photo)

Professors in the landscape architecture program in the College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources ( CAHNR ) have implemented a teaching model that emphasizes collaboration between students.

This initiative is spearheaded by Assistant Professors Mariana Fragomeni and Julia Smachylo in the Department of Plant Science and Landscape Architecture.

The approach, called a vertical teaching model, is not new to the world of architecture, but it had not been implemented in UConn’s program before.

While a traditional approach to studio education has cohorts working on separate projects, a vertical studio model enables collaboration between students at various stages in their educational career to work side by side. This mimics the environment of professional designers who work across disciplines and experience levels where they can help and learn from one another.

“I think the value of incorporating the vertical studio is that constant reminder to students that what they’ve learned in the previous class isn’t forgotten, it’s added,” Fragomeni says.

While there are many benefits to the traditional vertical studio model, it poses challenges as well. It relies heavily on upperclassmen having developed the skills they need to teach the undergraduates and doesn’t work well for all learning styles.

“From a pedagogical standpoint, there’s a lot of pros and cons to teaching the vertical studio,” Fragomeni says.

To get the best of both worlds, Fragomeni and Smachylo devised a hybrid model. In their version of the vertical teaching model, upper- and underclassmen work on the same project but on different stages of it. Smachylo’s studio for sophomores collaborates with Fragomeni’s junior-class studio on service-learning projects. They first implemented this model in the spring 2023 semester.

In Smachylo’s studio, the underclassmen meet with the client and complete a site analysis, the first step of any landscape architectural project. They assess the physical, biological, and cultural elements of the site using UConn facilities such as the soil testing laboratory and the plant diagnostics lab. This takes full advantage of their colleagues in UConn’s plant science program and UConn Extension, unique aspects that aren’t always available at other universities.

The sophomores then present their findings to the juniors who take up the baton and develop a proposal to share with the client.

The two groups spend a week together collaborating. During this stage, the juniors can ask the sophomores questions about their site analysis and brainstorm together.

“The sophomores start to get a glimpse of how what they’re doing fits in the bigger picture of the design process,” Fragomeni says. “And then for the juniors it’s a reminder of the importance of the site analysis in the conceptualization of their design.”

The students worked on two projects in fall 2023. The first was developing a plan for the New Horizons neighborhood in Farmington, Connecticut. New Horizons is a non-profit community specifically designed for people with physical disabilities. This partnership also led to a service-learning project for this semester with their sister institution Cherry Brook Health Care Center.

“It’s a great opportunity for us to immerse our students in a real project,” Fragomeni says.

In the second project from last year, students worked with the Mansfield Downtown Partnership looking at climate and design in public spaces. Specifically, students were tasked with addressing heat mitigation in downtown Storrs as intense heat is becoming more common and windstorms threaten the natural shade cover provided by trees.

“The Partnership had some need to understand how that space was being used, and there were some issues with heat and wind,” Smachylo. “They really wanted our students to combine both site analysis and create a proposal for how to address adverse climate conditions.”

This model also fosters interpersonal connections between students at different academic levels.

“Informal spaces are really productive spaces,” Smachylo says.

Smachylo and Fragomeni have given presentations about their experience teaching with this model at national conferences.

“This way of working is generating excitement in the classroom,” Smachylo says. “I can see connections being made and the development of a design studio culture that was lost during remote teaching during Covid.”

Fragomeni and Smachylo say they look forward to continuing to adapt their teaching model with each new semester and each new project. The use of the vertical studio approach continues this semester with two additional service-learning projects that address accessibility and historic and agricultural conservation.

“We are new, and we come with the benefit of that energy. Our profession has vastly changed,” Fragomeni says. “It’s really a timely moment for the program to expand and explore.”

This work relates to CAHNR’s Strategic Vision area focused on Fostering Sustainable Landscapes at the Urban-Rural Interface .

Follow UConn CAHNR on social media

Recent Articles

April 3, 2024

Bethany Berger Wins 2024 UConn Law Teaching Award

Read the article

UConn Researchers Closer to Near Real-Time Disaster Monitoring

UConn Sports Analytics Symposium Showcases the Numbers Behind the Games

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Architect — Landscape Architects

Landscape Architects

- Categories: Architect Design Earth

About this sample

Words: 452 |

Published: Jul 10, 2019

Words: 452 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Arts & Culture Environment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1434 words

5 pages / 2352 words

2 pages / 964 words

2 pages / 1046 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Architect

Architecture means life to me, I still remember my strong determination to choose it as a university specialty, although all the hard Conditions that were in my way, I studied architecture and my passion has increased day by [...]

Inigo Jones has left a legacy in more areas than one. He could easily be considered a renaissance man with his involvement in so many different fields. Perhaps this is due to Vitruvius’ belief that architects should have [...]

Frank Gehry is a de-constructivist and one of the most recognizable figures of postmodern architecture. Postmodern architecture is an architectural movement which has shown in the mid of the twentieth century, as a reaction [...]

Ken Yeang (6 October 1948) is an architect, ecologist, planner and author from Malaysia, best known for his ecological architecture and ecomasterplans that have a distinctive green aesthetic. He pioneered an ecology-based [...]

The degree in finance or business is a condition for getting jobs in the financial industry, but what if you don't acquire one , and really want to work in this field? While it is more difficult for someone with a non-financial [...]

The development of any nation primarily depends upon its industrial development, which makes a rich contribution to the growth of a nation. The economic role played by women cannot be isolated from the framework of development. [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Login / Register

- You are here: Photography

Photo essay: looking in on the landscape

15 June 2020 By Max L Zarzycki Photography

Tracing the contours of the interior across countries and through history, the AR draws together intimate moments captured by photographers who look inside for their subjects

Looking in on the landscape 01

Left: one of Jacques Henri Lartigue’s earliest photographs (1904) in which he set his camera afloat in the tub, aged 10. Courtesy of Jacques Henri Lartigue Ministère de la Culture (France), MAP-AAJHL

Right: Martina Mullaney’s Dinner For One series (1998) Courtesy of Martina Mullaney

Locked tight away from the inimical outside, from the air’s mute buzzing, the eye turns in. Photographers point their lenses back towards themselves, towards the home and its happenings, and the camera – as a mechanical tool of hard truth and fixity, of cool representation – becomes also an agent of distortion. Through endless, tireless looking, the intricately known is set to sea as familiar forms shift and expand into broad and alien territories, the lingering image drifting aslant into an uncanny ocean.

Looking in on the landscape 02

Left: Untitled by William Eggleston (c1973) Courtesy of William Eggleston

Right above: In My Room, My Collection of Model Racing Cars (1905) by Jacques Henri Lartigue. Courtesy of Jacques Henri Lartigue Ministère de la Culture (France), MAP-AAJHL

Right below: from Fumi Ishino’s book of photography Rowing a Tetrapod (2018) Courtesy of Fumi Ishino

The eyes go to ground, to rub into carpet bristles’ open field, to crawl. The same desks, chairs and cabinets now loom large, monumental entities taking on the city’s scale with toy trucks to whizz around mouse houses and slip under shoe. The softnesses yielded by the linen’s grain, the droop of the sash and the pink-plumed breeze are unbounded in their feeling. They are too much; swelling, bursting in the lungs. They fleet at the limits of reverie.

Looking in on the landscape 03

Left: between 1975 and 1976 Masao Mochizuki stayed at home and photographed his television screen. Courtesy of Masao Mochizuki / AKIO NAGASAWA Gallery

Right above: in Being Together (2010), John Clang projected the transmissions of his family’s webcams in Singapore onto his own living space in New York City. Courtesy of John Clang / Courtesy FOST Gallery

Right below: Untitled (Nashville) (2017), from Lorena Lohr’s Ocean Sands series. Courtesy of Lorena Lohr

Scenes from the outside are beamed in, accruing in a dense layer of transparency that hangs in thick folds over the familiar structures that make up the home. We are left reaching for loved ones with wires and interconnective networks, distances long and short alike flattening with the projection of parallel realities. Social lines are all imbued with the screen’s unlifely transmission, with the crackle and scratch of a tight electrical coil, a digital ether that encompasses and yet lies slightly out of grasp.

Looking in on the landscape 04

Left: from Laura Letinsky’s Hardly More Than Ever series, taken in 2001. Courtesy of laura letinsky / DOCUMENT / Yancey Richardson Gallery

Right above: Margaret Watkins’ The Kitchen Sink (1919) Courtesy of The Estate of Margaret Watkins / Robert Mann Gallery

Right below: from Martina Mullaney’s Dinner For One series (1998) Courtesy of Martina Mullaney

All around, tall stacks and toppling towers of crockery build up in vast conurbations over every horizontal plane; delicate still lifes constructed in the relentless operations of living, of eating and washing and eating again. Divisions of labour and other ancient genderings are brought bare-boned into exposure as the kitchen’s beating heart flows into the spaces surrounding, the many foodstuffs and their various vessels gathering up in an object array to be picked over or ploughed.

Looking in on the landscape 05

Left above: taken by Khadija Farah as part of The Journal, a collective series run by Women Photograph documenting the lives of women and non-binary photographers in quarantine. Courtesy of Khadija M Farah

Left below: from Performance Under Working Conditions (2003) by Allan Sekula. Courtesy of Allan Sekula Studio

Right: from Sentimental Journey (1971) by Nobuyoshi Araki. Courtesy of Nobuyoshi Araki

Amid this weirding world, this shrunken city, the bed becomes the curtained crux: a stage of sex and sleep and last source of comfort. Quiet intimacies are played out from between its sheets, unfolding in tensely woven bands between cohabitants. Made frayed or tender by constant contact, by aching, inescapable nearness, these gentle abrasions, the peculiar patterns that are drawn in the fabric between, are what will leave a mark.

Looking in on the landscape 06

Practicing Golf Swing (1982) comes from Larry Sultan’s 1992 book Pictures From Home, a memoir documenting both his own life and the lives of his parents. Courtesy the Estate of Larry Sultan / MACK Books / Casemore Kirkeby

This piece is featured in the AR June 2020 issue on Inside – click here to buy your copy today

Since 1896, The Architectural Review has scoured the globe for architecture that challenges and inspires. Buildings old and new are chosen as prisms through which arguments and broader narratives are constructed. In their fearless storytelling, independent critical voices explore the forces that shape the homes, cities and places we inhabit.

Join the conversation online

A Word for Landscape Architecture

John Beardsley

Featured in:

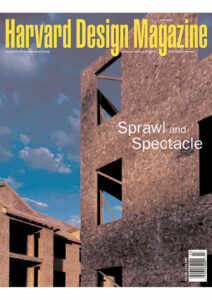

12: Sprawl and Spectacle

I wish to speak a word for landscape architecture, for design inextricable from the history of a site, from its spatial, material, and phenomenal conditions, and from natural and social ecology, as contrasted with a design merely of buildings—to regard design as a part and parcel of nature, as well as of society. I wish to make an extreme statement, if only to make an emphatic one, for there are enough champions of architecture.

Anyone familiar with “Walking,” by Thoreau, will recognize that I have borrowed the rhetoric of the preamble of his essay. Thoreau used hyperbole to make a point; I am inclined to do the same in order to argue that landscape architecture will soon become the most consequential of the design arts. Admittedly, the profession has been beset by various problems. Relatively young, it lacks the rich theoretical and critical traditions of architecture. It has long been constrained by an attachment to the picturesque. In recent years it has been at war within itself, diverse factions pitting ecology against art—as if the two could not coexist. And so far it has failed to attain the public profile of architecture or the fine arts: built works of landscape architecture are not as readily identified and evaluated as paintings, sculptures, or buildings.

Yet as the landscape architect Laurie Olin has written, “It is hard to think of any field that has accomplished so much for society with so few people and with so little understanding of its scope or ambitions.” 1

Much in the history of the discipline substantiates this large claim: the 19th-century parks that enhance so many American cities; the national and state park systems; the rise of urban planning in the 1920s, which was an outgrowth of landscape architecture; the development of prototypical garden cities; the stunning Modernist works of such designers as Daniel Urban Kiley, James C. Rose, and Lawrence Halprin; and the embrace of ecology in recent years as a moral compass for the profession. Pressing Olin’s argument, I would insist that recent achievements in landscape architecture are as visually compelling as those of the past and even more technically sophisticated and conceptually complex. Combining elements of architecture and sculpture with knowledge from the natural sciences, landscape architecture today is struggling to meet profound environmental, social, technological, and artistic challenges.

Thirty years ago, in Design on the Land , historian Norman Newton could confidently describe landscape architecture as “the art—or the science if preferred—of arranging land, together with the spaces and objects upon it, for safe, efficient, healthful, pleasant human use.” 2 This definition is too terse for the intricacies of practice today. We are now apt to view landscape architecture as an “expanded field,” as a discipline bridging science and art, mediating between nature and culture. 3

Landscape architecture is neither art nor science, but art and science; it fuses environmental design with biological and cultural ecology. Landscape architecture aims to do more than to produce places for safe, healthful, and pleasant use; it has become a forum for the articulation and enactment of individual and societal attitudes toward nature. Landscape architecture lies at the intersection of personal and collective experiences of nature; it addresses the material and historical aspects of landscape even as it explores nature’s more poetic, even mythological, associations.

Complexity alone cannot engender consequential works of art. Significant cultural expressions often result from the convergence of a compelling artistic language with an urgent external stimulus. The rise of Cubism, for instance, can be viewed as a register of the radical social and technological transformations of early 20th-century modernization, just as the emergence of Surrealism can be seen as an expression of the influence of Freudian theory. The consequences of such convergences are discernable in design as well as in art. Urgent external stimuli have lately been much in evidence in landscape architecture. Demands for the restoration of derelict and often toxic industrial sites pose artistic, social, and technical difficulties; so does the need to reuse abandoned sites in declining urban centers. The emergence of environmentalism and the ethic of sustainable design are encouraging the development of “green” infrastructure for improved energy efficiency, storm water management, waste water treatment, bioremediation, vegetal roofing, and recycling. Intensifying suburban and exurban sprawl requires new strategies for landscape management and open space preservation. Continued population growth, especially in the Third World, is heightening the need to develop minimum standards for the provision of urban green space, while increased leisure time in the developed world is placing unprecedented burdens on parks and other natural places of recreation. Landscape practitioners today are grappling as well with the dilemma of designing at radically different scales—from that of the small urban space to that of the entire ecosystem.

These phenomena raise an important question. Are these urgent social and environmental demands being met by the development of a compelling design language—a language particular to landscape architecture? Landscape architect Diana Balmori has articulated widespread anxieties within the profession that landscape architecture has yet to find a contemporary idiom. “The profession of landscape architecture appears to be finished,” she argued. “Its edges have been overtaken by architects and environmental artists. Ecology has been taken over by engineers and hasn’t really affected design. At the same time, the profession hasn’t found a core. The center has not been defined and held.” 4

In my view, the situation is not nearly so dire. I would argue that external pressures and contemporary expressive means are indeed working together in recent landscape architecture. I would argue too that this convergence is providing the profession with compelling narratives that might restore the sense of a vital center and help it achieve the visibility so lacking in recent decades.

One such narrative is sustainability—an idea that increasingly informs the design of buildings and landscapes. Indeed, sustainable design seems to require some degree of interdisciplinary cooperation or hybridization in the creation of “green” infrastructure. Examples of this kind of work include landscape designer Herbert Dreiseitl’s unusual and visible storm water retention and purification system for architect Renzo Piano’s DaimlerChrysler complex at Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. This ambitious scheme features rooftop gardens that capture and filter rainwater, which is then directed to cisterns and used in the building. The cisterns also feed a large lagoon, where reeds provide physical and bio-chemical cleansing; mechanical filters furnish backup purification. The benefits of this scheme are not only technical but also aesthetic, even educational; not simply an element of infrastructure, the lagoon is an attractive public amenity that offers lessons in and demonstrations of urban hydrology. More generally, such collaborations suggest that the knowledge provided by landscape architects is increasingly essential to the responsible practice of architecture.

Landscape remediation is another narrative resulting from the convergence of contemporary subject and idiom. At the 200-hectare site of the former iron and steel plant Duisburg-Meiderich in Germany, the landscape architecture firm of Latz + Partner has designed a park that sets new standards for reclamation—for the kind of reclamation, moreover, that does not disguise the problematic history of its site. Designed by Peter Latz and Anneliese Latz, Landscape Park Duisburg North makes an aesthetic and political strategy out of revealing site disturbances. The facility, abandoned by Thyssen Steel in 1985, included blast furnaces, ore bunkers, and a sintering plant; it was criss-crossed by roads, rail lines, and a canal. The soil of the site was contaminated with heavy metals, the canal polluted. The design of the reclamation was guided by existing infrastructure: elevated rail lines and ground-level roads were retained to provide both topographical interest and a framework for circulation. A sewer line and treatment plant were built to clean the old canal; a new storm water collection system filled the former cooling and settling tanks—once contaminated with arsenic—with fresh water.

At the heart of the project are the preserved blast furnaces. Like other relics of heavy industry, these structures seem at once terrible and awe-inspiring. To emphasize these qualities, Latz + Partner have surrounded the furnaces with trees, making them appear like craggy mountains glimpsed through a forest. There is a precedent for such industrial archaeology—I am thinking chiefly of Gasworks Park in Seattle. Both might be understood as instances of the “industrial sublime.” The constructions at Duisburg surround a space that has been named Piazza Metallica, where forty-nine salvaged hematite slabs—each about 2.5 meters square and weighing nearly eight tons—are set out in a grid; the recycled metal, which once lined casting pits in the foundry, commemorates the melting and pouring processes that occurred there. Near the blast furnaces are the remains of ore bunkers that have been transformed into enclosed gardens. Deep within thick concrete walls, these gardens produce a kind of uncanny juxtaposition: they are cloistered, almost monastic spaces, yet set in a menacing industrial frame. Perhaps more than any other element in the park, they convey the designers’ strategy of retaining and revealing yet simultaneously transforming the structures of the site.

Several remediation techniques have been employed at Duisburg, depending on site conditions. The most toxic remnants, including the old sintering plant, were dynamited and buried. Elsewhere contaminated materials were left in place. Several large slag heaps with low-level hydrocarbon pollution, already in stable condition and colonized by plants, were left undisturbed. They are available for limited access and use while they are gradually decontaminated through bioremediation. Retaining the piles has two advantages: it prevents further dispersal of the pollutants, and it creates compelling memorials to site disturbance. Such “found” landscapes produce some of the park’s most intriguing images, such as that of an ore cart—still in its tracks—sprouting vegetation.

Just as important, although less obvious, Landscape Park Duisburg North is an example of social as well as environmental restoration. A place that no longer had any real value to society and that otherwise would have been an eyesore has been given an entirely new life, one that few might have imagined it could have. In a region with little open space, the park offers significant and unusual opportunities for recreation: the blast furnace can be climbed to height of about fifty meters; the cooling tanks are used for swimming, the concrete chimneys for climbing. At a more speculative level, the park offers a lesson in the environmental costs of modern industrial policies and an occasion to wonder about future appropriate choices. Effacing the site’s history and erasing its contradictions would have been far less compelling. As Peter Latz says, “The point is, where is the imagination most challenged, in a state of harmony or in a state of disharmony? Disharmony produces a different statement, a different harmony, a different reconciliation. . . . The seemingly chance results of human interference, which are generally judged to be negative, also have immensely exciting, positive aspects.” 5

In such circumstances the role of the designer is to decide what to retain, what to transform, and what to replace. Disharmony, discontinuity, contradiction: these are the conditions driving the development of a contemporary language of landscape architecture.

But if I had to choose one project that suggests all the intricacies of recent landscape architecture, it would be Parque Ecológico Xochimilco in Mexico City. Not only does this project articulate the commanding narratives that undergird recent practice, such as remediation and sustainability, it also addresses the challenges of urbanization in one of the most populous cities in the developing world, providing both open space for recreation and productive land for economic development. And it does all this on multiple scales, from the circulation in a flower market to the workings of an extensive ecosystem. Even more than Landscape Park Duisburg North, Xochimilco suggests the large role that landscape architecture can now play in social and environmental remediation.

Xochimilco, meaning “the place where flowers are grown,” is a fragment of a pre-Conquest—in places even pre-Aztec—landscape of artificial garden islands, created in the lake that once filled a large area of the valley of Mexico. The islands, called chinampas , were constructed by piling soil on reed mats and anchoring their edges with salix trees. Dating to the 10th century, this landscape of canals and rectangular islands was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987; the designation prompted a large-scale environmental restoration project undertaken by Mexico City and the borough of Xochimilco. Designed by Mario Schjetnan of Grupo de Diseño Urbano and built in the early 1990s, the project encompasses some 3,000 hectares of surviving islands.

The site presented extraordinary challenges. Many of the islands were sinking due to the many wells that fed upon aquifers. Urban development was increasing storm water runoff and subjecting the area to increased flooding. Surface water was contaminated; canals were choked with aquatic plants. Those islands deep in the canal system were hard to reach and thus unavailable for agriculture; those nearer the edges of the site were being encroached on by unauthorized residential buildings. The design was guided by hydraulic strategies: water was pumped back into the aquifer to stabilize the site; large reservoirs were created to retain storm water; polluted water was processed at treatment plants, and the treated water was discharged back into the lake to regulate the water levels in the canals. Eroded islands were recreated using meshes of logs filled with dredge and stabilized by salix trees. (More than 1 million trees were planted on the site.) Agriculture was reintroduced: some islands have pastures for grazing; others are planted with flowers and vegetables. A tree nursery was also located on the site; every year it produces 30 million trees that are then planted throughout Mexico City. Canals were cleared of harmful vegetation and rehabilitated for recreation as well as agriculture. Today, pole barges ply the canals of Xochimilco, especially on weekends; gondolas and gondoliers are available for hire at embarcaderos built along the edge of the site. Out in the canals, you can collect sustenance for body and soul: kitchen barges sell food, while others ferry professional musicians, available to serenade visitors with patriotic and romantic songs.