Digital Homework Activities on Windows Pc

Developed By: DTP Online Corporation

License: Free

Rating: 4,3/5 - 585 votes

Last Updated: April 20, 2024

Compatible with Windows 10/11 PC & Laptop

App Details

| 2.76 | |

| 59.5 MB | |

| December 11, 23 | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

App preview ([ see all 15 screenshots ])

About this app

How to install digital homework activities on windows.

Instruction on how to install Digital Homework Activities on Windows 10 Windows 11 PC & Laptop

In this post, I am going to show you how to install Digital Homework Activities on Windows PC by using Android App Player such as BlueStacks, LDPlayer, Nox, KOPlayer, ...

Before you start, you will need to download the APK/XAPK installer file, you can find download button on top of this page. Save it to easy-to-find location.

[Note] You can also download older versions of this app on bottom of this page.

Below you will find a detailed step-by-step guide, but I want to give you a fast overview of how it works. All you need is an emulator that will emulate an Android device on your Windows PC and then you can install applications and use it - you see you're playing it on Android, but this runs not on a smartphone or tablet, it runs on a PC.

If this doesn't work on your PC, or you cannot install, comment here and we will help you!

- Install using BlueStacks

- Install using NoxPlayer

Step By Step Guide To Install Digital Homework Activities using BlueStacks

- Download and Install BlueStacks at: https://www.bluestacks.com . The installation procedure is quite simple. After successful installation, open the Bluestacks emulator. It may take some time to load the Bluestacks app initially. Once it is opened, you should be able to see the Home screen of Bluestacks.

- Open the APK/XAPK file: Double-click the APK/XAPK file to launch BlueStacks and install the application. If your APK/XAPK file doesn't automatically open BlueStacks, right-click on it and select Open with... Browse to the BlueStacks. You can also drag-and-drop the APK/XAPK file onto the BlueStacks home screen

- Once installed, click "Digital Homework Activities" icon on the home screen to start using, it'll work like a charm :D

[Note 1] For better performance and compatibility, choose BlueStacks 5 Nougat 64-bit read more

[Note 2] about Bluetooth: At the moment, support for Bluetooth is not available on BlueStacks. Hence, apps that require control of Bluetooth may not work on BlueStacks.

How to install Digital Homework Activities on Windows PC using NoxPlayer

- Download & Install NoxPlayer at: https://www.bignox.com . The installation is easy to carry out.

- Drag the APK/XAPK file to the NoxPlayer interface and drop it to install

- The installation process will take place quickly. After successful installation, you can find "Digital Homework Activities" on the home screen of NoxPlayer, just click to open it.

(*) is required

Download older versions

Other versions available: 2.76 , 2.73 , 2.30 , 1.89.

Download Digital Homework Activities 2.76 on Windows PC – 59.5 MB

Download Digital Homework Activities 2.73 on Windows PC – 66 MB

Download Digital Homework Activities 2.30 on Windows PC – 63.5 MB

Download Digital Homework Activities 1.89 on Windows PC – 49.2 MB

You Might Also Like

More Apps By This Developer

Most Popular Apps

- APKPure App

- APK Download

- Windows APP

- Pre-register

- Chrome Extension

Digital Homework Activities

2.76 by DTP Education Software

Nov 21, 2023

Use APKPure App

Get Digital Homework Activities old version APK for Android

About Digital Homework Activities

English practice exercises are designed according to i-learn smart start book series

Digital Homework Activities is one of the great and effective ways to help students revise and practice English at home. The activities are richly designed and varied, with vivid and funny images that help students improve their language skills by practicing and consolidating the knowledge they have learned.

Main function:

• Designed by professionals with experience in the field of English language teaching and specialist technicians.

• For elementary students aged 5-11.

• Parents are involved with students in reviewing and monitoring the learning situation of their children.

• Vivid visual images, fun activities attract students.

• The content of the training is diversified with various activities to help strengthen the knowledge.

EXPLAIN ABOUT DIGITAL HOMEWORK ACTIVITIES:

Digital Homework Activities is an activity that trains and consolidates knowledge in the form of games, stimulates the joy of learning English and encourages the ability to self-study with engaging content, vivid images, combined with audiovisuals. , listening, listening and typing to help students become familiar with using computers in learning to create the basis for students to approach modern technology in learning English.

Each activity is designed to suit each topic and lessons that are relevant to the ISS series

In particular, the evaluation and statistics of the number of exercises completed at the time of practice allow children to see their progress.

Additional APP Information

Latest Version

Uploaded by

Luanna Sousa Borges

Requires Android

Android 8.0+

Available on

Free Education App

Flag as inappropriate

What's New in the Latest Version 2.76

Last updated on Nov 21, 2023

- Fix issues

Digital Homework Activities Screenshots

Old Versions of Digital Homework Activities

Digital homework activities 2.76.

59.5 MB Nov 21, 2023

Digital Homework Activities 2.75

63.7 MB Sep 26, 2023

Digital Homework Activities 2.74

65.7 MB May 30, 2023

Digital Homework Activities Alternative

Get more from DTP Education Software

Popular Articles In Last 24 Hours

Digital Homework Activities FAQ

How to download and install digital homework activities, what's the system requirement of digital homework activities, how to get the latest version of digital homework activities, how can i find the alternatives to digital homework activities, also available for other platforms, hot apps in last 24 hours.

Discover what you want easier, faster and safer.

- APK Install

- APK Signature Verification

- APK Download Service

- Developer Console

- Traffic Monetization with APKPure

- Business Cooperation

- English(IT)

- Italiano(IT)

- Tầm nhìn – Sứ mệnh – Giá trị cốt lõi

- Cơ cấu Tập đoàn

- Thành tích nổi bật

- Đối tác chiến lược

- Thiếu niên – Người lớn

- Xuất bản & Thiết kế chương trình

- Giảng dạy tiếng Anh

- Đào tạo giáo viên

- Phần mềm & Thiết bị giáo dục

- E-catalogue

- Góc báo chí

Digital Homework Activities (DHA)

Digital Homework Activities (DHA) là ứng dụng cho học sinh làm bài tập về nhà trên thiết bị di động. DHA được thiết kế dưới dạng trò chơi Tiếng Anh vui nhộn hấp dẫn giúp học sinh rèn luyện và củng cố kiến thức đã học.

Ứng dụng làm bài tập về nhà Digital Homework Activities (DHA)

Đã có mặt tại google play và app store, các tính năng chính:.

- Dành cho học sinh khối tiểu học trong độ tuổi từ 5-11

- Được thiết kế bởi các chuyên viên có kinh nghiệm trong lĩnh vực giảng dạy tiếng Anh

- Mỗi hoạt động được thiết kế khớp với từng chủ đề và các bài học tương ứng với bộ sách i-Learn Smart Start

- Phần đánh giá và thống kê số bài tập hoàn thành ngay tại thời điểm luyện tập cho phép trẻ thấy được sự tiến bộ của mình

- Phụ huynh dễ dàng theo dõi tình hình học tập của con em mình

- Hình ảnh trực quan sinh động, hoạt động vui nhộn cuốn hút học sinh

Các sản phẩm tương tự

Play On Windows PC

Digital Homework Activities

English practice exercises are designed according to i-learn smart start book series.

Advertisement

Latest Version

Digital homework activities app, old versions.

Digital Homework Activities 2.76 APK XAPK

Digital homework activities 2.75 apk xapk, digital homework activities 2.74 apk, trending searches.

The Best Android Emulator for PC

Messenger Meta Platforms, Inc. · Communication

Facebook Lite Meta Platforms, Inc. · Social

Xingtu Beijing Yanxuan Technology Co.Ltd · Photography

CapCut Bytedance Pte. Ltd. · Video Players & Editors

Disney Plus Disney · Entertainment

English to Spanish Translator Happy English · Education

Kahoot Kahoot! · Education

Schoology Schoology, Inc. · Education

Mathway Chegg, Inc. · Education

Blackboard Learn Anthology Inc. · Education

Canvas Student Instructure · Education

Desmos Desmos Inc · Education

English to Spanish Translator Apptack · Education

Quizlet Quizlet Inc. · Education

Duolingo Duolingo · Education

How to install XAPK, APKS, OBB?

You May Also Like

Forgot password

Digital Homework Activities 4+

Education software vietnam, được thiết kế cho ipad.

- #175 trong Giáo Dục

- 2,6 • 168 đánh giá

Ảnh Chụp Màn Hình

Digital Homework Activities là một trong những cách tuyệt vời và hiệu quả để giúp học sinh ôn tập và rèn luyện tiếng Anh tại nhà. Các hoạt động được thiết kế phong phú đa dạng, hình ảnh sinh động, vui nhộn giúp học sinh nâng cao khả năng ngôn ngữ qua việc luyện tập và củng cố những kiến thức các em đã học. Các tính năng chính: • Được thiết kế bởi các chuyên viên có kinh nghiệm trong lĩnh vực giảng dạy tiếng Anh và đội ngũ kỹ thuật viên chuyên ngành. • Dành cho học sinh khối tiểu học trong độ tuổi từ 5-11. • Phụ huynh cùng tham gia với học sinh trong việc ôn luyện và theo dõi tình hình học tập của con em mình. • Hình ảnh trực quan sinh động, hoạt động vui nhộn cuốn hút học sinh. • Nội dung luyện tập được thiết kế đa dạng với các hoạt động phong phú giúp củng cố kiến thức vững vàng. GIẢI THÍCH VỀ DIGITAL HOMEWORK ACTIVITIES: Digital Homework Activities là hoạt động rèn luyện và củng cố kiến thức dưới dạng các trò chơi, khơi gợi niềm vui học tiếng Anh và khuyến khích khả năng tự học với nội dung hấp dẫn, hình ảnh sinh động, kết hợp với phần nghe nhìn, nghe chọn và nghe đánh máy qua đó giúp học sinh làm quen với việc sử dụng máy tính trong học tập tạo tiền đề cho học sinh sau này tiến đến tiếp cận các trang thiết bị công nghệ hiện đại trong việc học tiếng Anh. Mỗi hoạt động được thiết kế khớp với từng chủ đề và các bài học tương ứng với bộ sách ISS Đặc biệt, phần đánh giá và thống kê số bài tập hoàn thành ngay tại thời điềm luyện tập cho phép trẻ thấy được sự tiến bộ của mình.

Phiên bản 1.0.41

Xếp hạng và Nhận xét

168 đánh giá

Sửa lỗi giùm

Sao ko thấy âm thanh hướng dẫn

Lỗi âm thanh

Âm thanh ko nghe được, đã report nhiều lần nhưng vẫn ko sửa. Quá chán

Cho hỏi con ko đăng nhập vào mật khẩu đc tức ko đc làm baoi đc

Ko đăng nhập mật khẩu đc

Quyền Riêng Tư Của Ứng Dụng

Nhà phát triển, Education Software VietNam , đã cho biết rằng phương thức đảm bảo quyền riêng tư của ứng dụng có thể bao gồm việc xử lý dữ liệu như được mô tả ở bên dưới. Để biết thêm thông tin, hãy xem chính sách quyền riêng tư của nhà phát triển .

Dữ Liệu Không Được Thu Thập

Nhà phát triển không thu thập bất kỳ dữ liệu nào từ ứng dụng này.

Phương thức đảm bảo quyền riêng tư có thể khác nhau, chẳng hạn như dựa trên các tính năng bạn sử dụng hoặc độ tuổi của bạn. Tìm hiểu thêm.

- Chính Sách Quyền Riêng Tư

Cũng Từ Nhà Phát Triển Này

iLearn Smart Start Fun English

ISW MultiROM

Có Thể Bạn Cũng Thích

YSchool Phụ Huynh

Apollo Active

OVI Parents

FLYER-Học chứng chỉ Cambridge

Bản quyền © 2024 Apple Inc. Giữ toàn quyền.

How to create digital homework that students love

By Laura McClure on April 26, 2016 in TED-Ed Innovative Educators , TED-Ed Lessons

US History teacher Jennifer Hesseltine combined TED-Ed Lessons with an interactive blackboard to create a digital homework space that students love.

Let’s redesign homework. When’s the last time your students got excited to do homework? Or said things like, “Wow…just WOW. It is amazing how much is out there that we just don’t know about”? What if every homework assignment could expand a student’s worldview while engaging a kid’s natural curiosity? One middle school teacher took on this challenge — so you don’t have to.

For her TED-Ed Innovation Project , US History teacher Jennifer Hesseltine created a digital homework space that students love. Here are her step-by-step instructions on how you can do it too:

1. Go to TED-Ed and create a lesson . This will be your next homework assignment.

You can either create a lesson using any engaging video of your choice, or simply customize an existing TED-Ed Original or TED-Ed Select lesson. If you need help creating a lesson, read this . If you need help customizing a lesson, read this .

2. Create space for lessons in your current learning management system. This is your new digital homework space.

Give this homework space a fun title and a quick description. For inspiration, check out mine on Padlet. You don’t have to use Padlet — your school’s current interactive learning tools will probably work fine for this project. For more options, check out a few teacher-recommended apps or try the free tools for teachers from Google, Apple and Microsoft.

3. Add your TED-Ed lesson to your digital homework space using the customized lesson link.

If you need help sharing a customized lesson link, read this . Easy, right? You can complete Steps 1-3 of this project today.

“Wow…just WOW. It is amazing how much is out there that we just don’t know about.” — 8th grade student after watching the TED-Ed Lesson: “Exploring other dimensions ”

4. Add and remove lessons often from your digital homework space to keep the content fresh and exciting for students.

Students love TED-Ed lessons and the opportunity to learn. Here are a few quotes from my students on a midyear class survey:

- “TED-Ed videos are more fun than normal homework assignments.”

- “One pro about watching a TED-Ed homework video is that you get to answer the questions while you watch the video.”

- “One pro about watching a TED-Ed homework video is that I get to choose what videos to watch. I’m learning about things that interest me.”

5. Take the opportunity in class to highlight the latest lessons.

I always take 5-10 minutes to show students the new lessons I have added (and always make sure to tell them about my favorites).

6. Share the link to your digital homework space once with students at the beginning of the school year.

Your students will have access to any of your recommended TED-Ed Lessons for the remainder of the school year. I gave my students a list of due dates for the entire school year so that students can plan ahead to complete the assignments.

7. Be prepared for student engagement and student feedback.

Students will likely start going directly to the TED-Ed website and giving you ideas of which lessons they would like to see on the homework space, and/or they will want to create some lessons of their own! As a matter of fact…a few of my students have helped to create homework lessons.

An example of a lesson inspired by an 8th grade student (who approached me with the video and created the questions in the “Think” section) is “Francine’s Interview.” This student’s lesson, as one would imagine, is a favorite among her peers.

Send reminders to students about upcoming homework assignments since the assignment due dates are not on a regular schedule (i.e. — due every day, or every other day). Students forget about upcoming assignments since the assignments are all digital, and the due dates are spaced more than one week apart.

Prepare for students who either do not have internet access, or have a difficult time accessing a working computer/piece of technology outside of school. We need to work together to figure out times each week for them to access their homework. I have been very flexible with students in this regard, and will continue to work with these students to be sure that they have a fair opportunity to complete the homework assignments.

- If you have questions about how to replicate this project , please reach out to me on Twitter.

This article is part of the TED-Ed Innovation Project series, which highlights 25+ TED-Ed Innovation Projects designed by educators, for educators, with the support and guidance of the TED-Ed Innovative Educator program. You are welcome to share, duplicate and modify projects under this Creative Commons license to meet the needs of students and teachers. To get started, click here to take the first step.

Digital Homework Activities for PC

Developed By: Education Software VietNam

License: Free

Rating: 1/5 - 2 reviews

Last Updated: 2021-10-01

Compatible: Windows 11, Windows 10, Windows 8.1, Windows 8, Windows XP, Windows Vista, Windows 7, Windows Surface

App Information

| 1.0.35 | |

| 88.1 MB | |

| 2020-04-07 | |

| | |

| | |

| 4+ | |

Compatible with Android

Compatible with iPhone, iPad and MAC

App preview ([ see all 5 screenshots ])

How to install Digital Homework Activities on Windows and MAC?

You are using a Windows or MAC operating system computer. You want to use Digital Homework Activities on your computer, but currently Digital Homework Activities software is only written for Android or iOS operating systems. In this article we will help you make your wish come true.

Currently, the demand for using applications for Android and iOS on computers is great, so there have been many emulators born to help users run those applications on their computers, outstanding above all Bluestacks and NoxPlayer.

Here we will show you how to install and use the two emulators above to run Android and iOS applications on Windows and MAC computers.

Method 1: Digital Homework Activities Download for PC Windows 11/10/8/7 using NoxPlayer

NoxPlayer is Android emulator which is gaining a lot of attention in recent times. It is super flexible, fast and exclusively designed for gaming purposes. Now we will see how to Download Digital Homework Activities for PC Windows 11 or 10 or 8 or 7 laptop using NoxPlayer.

- Step 1 : Download and Install NoxPlayer on your PC. Here is the Download link for you – NoxPlayer Website . Open the official website and download the software.

- Step 2 : Once the emulator is installed, just open it and find Google Playstore icon on the home screen of NoxPlayer. Just double tap on that to open.

- Step 3 : Now search for Digital Homework Activities on Google playstore. Find the official from developer and click on the Install button.

- Step 4 : Upon successful installation, you can find Digital Homework Activities on the home screen of NoxPlayer.

NoxPlayer is simple and easy to use application. It is very lightweight compared to Bluestacks. As it is designed for Gaming purposes, you can play high-end games like PUBG, Mini Militia, Temple Run, etc.

Method 2: Digital Homework Activities for PC Windows 11/10/8/7 or Mac using BlueStacks

Bluestacks is one of the coolest and widely used Emulator to run Android applications on your Windows PC. Bluestacks software is even available for Mac OS as well. We are going to use Bluestacks in this method to Download and Install Digital Homework Activities for PC Windows 11/10/8/7 Laptop . Let’s start our step by step installation guide.

- Step 1 : Download the Bluestacks software from the below link, if you haven’t installed it earlier – Download Bluestacks for PC

- Step 2 : Installation procedure is quite simple and straight-forward. After successful installation, open Bluestacks emulator.

- Step 3 : It may take some time to load the Bluestacks app initially. Once it is opened, you should be able to see the Home screen of Bluestacks.

- Step 4 : Google play store comes pre-installed in Bluestacks. On the home screen, find Playstore and double click on the icon to open it.

- Step 5 : Now search for the you want to install on your PC. In our case search for Digital Homework Activities to install on PC.

- Step 6 : Once you click on the Install button, Digital Homework Activities will be installed automatically on Bluestacks. You can find the under list of installed apps in Bluestacks.

Now you can just double click on the icon in bluestacks and start using Digital Homework Activities on your laptop. You can use the the same way you use it on your Android or iOS smartphones.

For MacOS: The steps to use Digital Homework Activities for Mac are exactly like the ones for Windows OS above. All you need to do is install the Bluestacks Application Emulator on your Macintosh. The links are provided in step one and choose Bluestacks 4 for MacOS.

Digital Homework Activities for PC – Conclusion:

Digital Homework Activities has got enormous popularity with it’s simple yet effective interface. We have listed down two of the best methods to Install Digital Homework Activities on PC Windows laptop . Both the mentioned emulators are popular to use Apps on PC. You can follow any of these methods to get Digital Homework Activities for PC Windows 11 or Windows 10 .

We are concluding this article on Digital Homework Activities Download for PC with this. If you have any queries or facing any issues while installing Emulators or Digital Homework Activities for Windows , do let us know through comments. We will be glad to help you out!

Top Reviews

You might also like.

More apps from the Developer

- Giới thiệu nhà trường

- Thông điệp của Hiệu Trưởng

- Các thế hệ quản lý nhà trường

- Cơ cấu tổ chức

- Cơ sở vật chất

- Đội ngũ giáo viên

- Thành tích nổi bật

- Hoạt động công đoàn

- Hoạt động đội

- Hoạt động ngoại khóa

- Văn bản hành chính

- KHO HỌC LIỆU

- Tin nhà trường

- Tin giáo dục

- Sự kiện nổi bật

- Giảng dạy & Học tập

- Bài viết của học sinh

Bổ trợ ôn tập tiếng Anh i-Learn qua Ứng dụng học tập Digital Home Activities (DHA)

Trước diễn biến phức tạp của dịch bệnh Covid-19, việc học của học sinh đã bị ảnh hưởng không nhỏ. Với mong muốn hỗ trợ các em học sinh ôn tập kiến thức tiếng Anh, sẵn sàng tâm thế để trở lại học trong thời gian tới Công ty TNHH Trực tuyến DTP xin kính gửi đến Quý nhà trường và Phụ huynh chương trình bổ trợ ôn tập tiếng Anh i-Learn qua Ứng dụng học tập Digital Home Activities (DHA).

Nội dung bài tập bổ trợ ôn tập tiếng Anh i-Learn qua Ứng dụng học tập Digital Home Activities (DHA) như sau:

| Video Lessons | Ôn lại các bài học tiếng Anh với Giáo viên bản xứ |

|

Skills time | – Listen & Find: Nghe và tìm đúng hình tương ứng – Listen & Spell: Nghe và gõ đúng từ tương ứng – Tag: trò chơi luyện tập, đánh giá kiến thức cuối bài học |

| Grammar | Các trò chơi thực hành các cấu trúc câu |

| Phonics | Luyện kỹ năng phát âm |

| Song | Ôn từ vựng, cấu trúc câu qua những bài hát giúp ghi nhớ bài học dễ dàng |

Hướng dẫn cài đặt và sử dụng

Bước 1: Đăng ký tài khoản DHA

- Link đăng ký dành cho lớp 1: http://dtplnk.com/ci1669

- Link đăng ký dành cho lớp 2: http://dtplnk.com/ci1670

Điền đầy đủ thông tin và nhấn nút Gửi đi để hoàn thành đăng ký tài khoản

Bước 2: Tải ứng dụng bài tập DHA

Link tải ứng dụng:

- Google Play (Android): http://dtplnk.com/125

- App Store (IOS): http://dtplnk.com/126

Hoặc Quý phụ huynh gõ Digital Home Activities trên thanh tìm kiếm ứng dụng của thiết bị di động

Bước 3: Đăng nhập và sử dụng Ứng dụng

Sau khi tải và cài đặt ứng dụng, Quý phụ huynh học sinh đăng nhập bằng số điện thoại và mật khẩu đã đăng ký tại bước 1 để sử dụng.

Để được hỗ trợ thêm thông tin về Ứng dụng học tập Digital Home Activities xin vui lòng liên hệ hotline 18006242 hoặc truy cập fanpage: i-Learn Smart Start Trân trọng cảm ơn./.

Thông tin mới đưa

Quyết định V/v công bố công khai giảm dự toán ngân sách năm 2024 của Trường TH Hàm Nghi.

HỘI NGHỊ VIÊN CHỨC – NGƯỜI LAO ĐỘNG NĂM HỌC 2024-2025

Quyết định v/v phê duyệt kết quả lựa chọn nhà thầu cung cấp thực phẩm cho học sinh bán trú trường th hàm nghi tháng 10 năm học 2024 – 2025.

Hoạt động ngoại khoá đầu năm học 2024 – 2025

HỌP PHỤ HUYNH ĐẦU NĂM HỌC 2024 – 2025

Kết quả lựa chọn nhà thầu gói thầu: cung cấp thực phẩm cho học sinh bán trú trường tiểu học hàm nghi từ học kỳ i năm học 2024-2025., trả lời hủy.

Email của bạn sẽ không được hiển thị công khai. Các trường bắt buộc được đánh dấu *

Bình luận *

Lưu tên của tôi, email, và trang web trong trình duyệt này cho lần bình luận kế tiếp của tôi.

- Open access

- Published: 08 October 2024

Provision of digital health interventions for young people with ADHD in primary care: findings from a survey and scoping review

- Rebecca Gudka 1 ,

- Kieran Becker 1 ,

- Tamsin Newlove-Delgado 1 &

- Anna Price 1

BMC Digital Health volume 2 , Article number: 71 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

People with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are at risk of negative health outcomes, with risks reduced through evidence-based treatments. Therefore, ensuring continued access to treatment for young people with ADHD, especially as they transition from child to adult services, is a priority. Currently many young people with ADHD are unable to access adequate care, with negative consequences for patients and their communities. Preliminary evidence suggests digital health interventions (DHIs) may act as an effective adjunct to usual care, helping overcome barriers to access, and improving outcomes by increasing understanding of ADHD as a long-term condition. The aim of this mixed methods study is to explore the healthcare information preferences of people with lived experience of ADHD in the primary care context and considers these in the light of the emerging body of literature on DHIs for ADHD. To explore this, a descriptive summary of cross-sectional survey responses was compared and discussed in the context of DHIs identified in a scoping review.

Digital apps, followed by support groups, were deemed the most useful information resource types by survey respondents, but were the least currently used/provided. Over 40% participants indicated a preference for signposting to all resource types by their general practitioner (GP), suggesting that GPs are credible sources for ADHD healthcare information. The scoping review identified nine studies of DHI for ADHD, consisting of games, symptom monitoring, psychoeducation, and medication reminders, with limited evidence of effectiveness/implementation.

Conclusions

People with ADHD state a preference for digital apps as an adjunct to usual care. However, these are currently the least provided information resource in primary care, indicating a key area for future development. The limited evidence base on DHIs for ADHD suggests combining digital apps and support networks, and utilising multimodal delivery methods may also enhance the delivery of healthcare information.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has an estimated worldwide prevalence of 5% and is one of the most common paediatric neurodevelopmental disorders [ 1 ]. Approximately 40% people diagnosed with ADHD in childhood/adolescence will experience symptoms that persist into adulthood, which also predisposes them to the development of other psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression [ 2 ]. Experiencing ADHD symptoms can have a negative influence on many long-term outcomes for young people, such as their physical and mental health, academic and employment opportunities, services use, financial position, engagement in criminal activity and mortality [ 3 ].

Treatment options for ADHD include pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, which have both been shown to have short-term efficacy [ 4 , 5 ]. Long-term outcomes for people with ADHD can also be improved when they receive treatment, compared to when people with ADHD do not receive treatment [ 3 ]. The management of ADHD is most effective when pharmacological and non-pharmacological support is delivered in combination; medications are properly trialled and titrated; and patients have adequate access to specialist support [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. However, there are many common barriers to managing ADHD including side effects and poor tolerability of medication, difficulty adhering to treatment, caregiver/professional misconceptions and stigma surrounding medication, and limited availability and accessibility of ADHD services in the UK [ 4 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Research shows that less than a quarter of people who required ADHD medication in the UK transferred successfully from child to adult mental health services, leaving them without easy access to specialist treatment [ 12 ]. This is of concern as the transition from adolescence into adulthood is a period where young people need access to services most [ 13 ].

With recent research indicating a failure of healthcare for young people with ADHD, there is a clear need for improvements to existing provision [ 14 ]. An increased role for primary care in the management of ADHD, may increase access to healthcare for currently underserved groups [ 6 ]. In addition, non-pharmacological treatments as an adjunct to existing practice may help to improve access to care by being used instead of or to support medication; while people wait for diagnosis, referral, or prescriptions; to support access; or to support psychoeducation. Recent changes to healthcare delivery in England, such as the formation of Primary Care Networks and Integrated Care Boards (ICB) which organise the provisions of care for local communities [ 15 , 16 ], present new opportunities to investigate innovative types of treatment/support which may be more accessible to patients via their general practitioner (GP). Digital health interventions (DHIs) offer remote access and the ability to be used repeatedly, which may provide cost effective support and enhance the delivery of healthcare for young people with ADHD via primary care, acting as an adjunct to mental health provisions.

Digital resources and interventions

Evidence suggests that DHIs for ADHD can be a beneficial adjunct to usual care and improve attention and social function for people with ADHD [ 17 , 18 ]. They may also help people with ADHD to understand and self-manage their ADHD by providing information to help make informed decisions about healthcare or acting as reminders and aids to perform self-management activities such as medication adherence. Types of DHIs include websites and online resources, mobile apps, computer software, Internet-delivered therapies, or gamified interventions. DHIs have advantages such as access in rural areas, at times of day which suit users, fewer side effects and less potential for misuse [ 18 ]. Shou et al . found that the reach of DHIs is broad in developed countries that have the infrastructure and hardware to participate [ 17 ]. Their systematic review found that both children and adults benefitted equally from DHIs, but there were no studies pertaining to adolescents and young adults (ages 16–25) [ 17 ].

There is growing interest in the value of DHIs to supplement the delivery of mental health support. However, ADHD is neglected in the evidence base of DHIs [ 19 ]. In particular, there is limited evidence for interventions which provide support for young people with ADHD, aged 16–25 [ 17 , 19 ]. This is of importance because of the transitions that young people often experience at this age, such as the transition from child to adolescent mental health services, within the education system, and leaving home/parental-care. This research has been designed to address these gaps in the literature, investigating the experiences of, and interventions for, 16–25-year-olds with ADHD.

The aim of this study is to compare the current availability of DHIs which could support the delivery of healthcare for young people with ADHD with the needs and expectations of people with lived experience of ADHD. This will provide evidence for future co-production of guidelines and efficacy studies which will improve primary care for young people with ADHD. The research questions are:

What current DHIs exist to support the delivery of healthcare for young people with ADHD?

What are the reported needs and expectations of people with lived experience with regards to information resources to support the delivery of healthcare for young people with ADHD in primary care?

What comparisons can be made between currently available DHIs and the needs and expectations of people with lived experience?

This work is part of a broader programme of work, the “Mapping ADHD services in Primary care” (MAP) study [ 20 ]. All methods involving human participants have been approved by the Yorkshire and the Humber – Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 22/YH/0132). All survey participants gave informed consent for their data to be used in this study. This is a mixed-methods study, with results presented from a scoping review and a subset of data from the online MAP survey.

Online survey

The survey methodology is described in more detail elsewhere [ 20 ] but is briefly summarised here. The survey was developed in response to a previous study – the Children and Adolescents with ADHD in Transition between Children’s and adult Services study [ 12 ] – which informed us on the priorities of young people with ADHD with regards to their experiences of primary care. These priorities guided the development of the survey questions. The survey was piloted with research advisory groups and revised to simplify the wording and ensure it was accessible and engaging for all participants. The final version of the survey was tested to ensure that they could be completed within ten minutes. The survey was hosted on Qualtrics, a General Data Protection Regulation compliant online survey tool, and the core team tested it to ensure there were no technical problems before disseminating the survey link.

Questions explored current primary care practice in relation to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines for diagnosis and management of ADHD. Questions asked participants to reflect on their experiences when they were between the ages of 16 and 25 years old. This project uses data from a subset of questions described in Table 1 focussed on information resources that help to self-manage ADHD.

Participants

The population of interest included young people with ADHD and their supporters (e.g., parents, carers, guardians) over the age of 16 and living or working in England. Anyone over the age of 16 was eligible to take part, but participants were informed that the context of the study was centred around experiences of people aged 16–25 accessing primary care. The target sample size was 210, to allow for a minimum of six respondents from each ICB to ensure adequate coverage of each NHS ICB in England.

Dissemination and sampling

A convenience sample were recruited through various methods. A link to an online survey was shared with participants via emails. Snowball sampling was employed by asking the lead researcher’s relevant professional contacts to forward emails with the survey link to their networks. Additionally, research partners, the ADHD Foundation and UK Adult ADHD Network, shared the study via social media and their mailing lists. Finally, researchers shared the survey link on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts associated with the study.

Halfway through dissemination, as per protocol, a geographic analysis of responses identified London as an underrepresented NHS region. Subsequently, dissemination was targeted to London using local ADHD groups and emails to contacts in relevant areas. A paid Facebook advertisement was created in the final week of dissemination to target underrepresented geographic regions. The survey was open for six weeks.

Data analysis

Descriptive data analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel. Respondents were categorised as either a young person with ADHD or a supporter of a young person with ADHD, depending on which they reported as their main role. There were four questions from the survey relevant to the aims of this report, described in Table 1 .

Participants were able to opt out of answering the information resource questions. Therefore, where participants did not answer a question on information resources, they were excluded from the analysis for that question and treated as “missing data.” These non-continuing participants have been recorded but were not included in the analysis. Due to the nature of the non-probability sample and the fact that missing data cannot be treated as random, multiple imputation of missing data has not been conducted.

For each question, the percentages of participants who indicated “yes” to each information resource type were summarised and tabulated, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for proportions. These summaries were presented visually using bar graphs.

Scoping review

A literature search was conducted by RG in the following electronic databases: Medline, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library. The searches were conducted on 9th December 2022. Search terms were developed with the support of information specialists at the University of Exeter and included terms synonymous with “young people,” “people with ADHD,” and “digital/online interventions.” No date limit was applied to the search results because DHIs have only been available in recent years and thus we did not anticipate finding studies older than ten years. Texts were limited to English language and human participants only. The full search strategies are detailed in Additional File 1.

Studies were included if they measured effectiveness, acceptability, engagement with or experience of a DHI from a sample of young people with ADHD. The intervention had to be delivered online or use a digital technology and had to be self-administered in any country or healthcare setting. Neuro/bio-feedback interventions were excluded because the authors deemed them unable to be replicated in an a self-administered, at-home setting without clinician intervention. Studies of parent, parent–child or family interventions were also excluded. After discussion, the authors decided that any study which included some participants within the desired age range could have valuable results to help answer the research questions, but studies which were aimed specifically at age ranges outside of the specified range (e.g., 5–12-year-olds) would be less relevant and therefore not included. Therefore, after title and abstract screening, the inclusion criteria were narrowed to only include studies where at least one participant was within the target age range (16–25 years old). Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Additional File 1.

The records found were imported to Mendeley and duplicates were removed. All remaining titles and abstracts were dual screened by RG, AP, and KB. RG reviewed all the included titles and abstracts to apply the updated criterion regarding age of participants. Full-text articles were then screened by the same team of independent reviewers. Any disagreement between reviewers was discussed until agreement was reached. Where no agreement could be reached, the third reviewer was consulted.

RG charted data regarding details of the publication (author, year, country of origin), study design, type and delivery mode of interventions, characteristic of ADHD targeted by the intervention, and any described facilitators and barriers to implementing interventions. Results were synthesised using a narrative approach.

In total, there were 254 unique respondents to questions about information resources, reaching the target number of responses. Of these responses, 96 were a supporter of a young person with ADHD and 158 were a young person with ADHD aged 16 or over. Additionally, responses were received from all NHS ICBs in England. Table 1 provides the number of unique respondents and non-continuing respondents for each survey question.

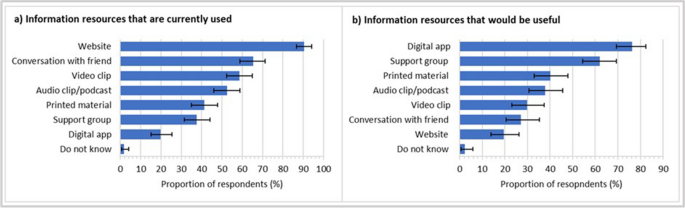

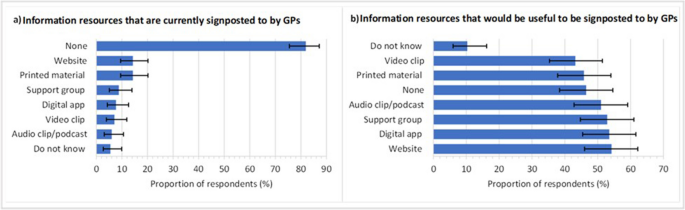

Responses are described below. Tables 2 and 3 show the numbers and proportions of respondents who answered “yes” to information resource types for each question, represented visually in Figs. 1 and 2 .

Information use reported by people with lived experience of ADHD. Bar graphs which show the proportion of respondents with lived experience of ADHD who reported that they a) currently use and b) would find it useful to use each information resource type to help self-manage their ADHD. 95% confidence intervals are indicated

Information signposting by GPs reported by people with lived experience of ADHD. Bar graphs which show the proportion of respondents with lived experience of ADHD who reported that they a) are currently signposted to and b) would find it useful to be signposted to each information resource type by their general practitioner (GP) to help self-manage their ADHD. 95% confidence intervals are indicated

Use of information resources

With regards to which resources respondents currently use, websites were reported by the most respondents (90.9%), followed by a conversation with a friend (65.3%). Digital apps were the least reported in current use of information resources (19.8%). The order of current use of information materials versus which would be useful were exactly opposite. Digital apps (76.4%) followed by support groups (62.1%) were reported by the most participants as “would be useful,” with the least reported resource being websites (19.5%).

Signposting of information resources by GPs

Most respondents indicated they had not been signposted to any resources (81.9%), whereas 14.3% reported being signposted to printed materials, and 14.3% to websites. There is little distinction between information resource type with regards to how many respondents reported that they would be useful to hear about from their GPs, with only 11% difference between the most and least reported information resource, websites (54.2%) and video clips (43.2%) respectively.

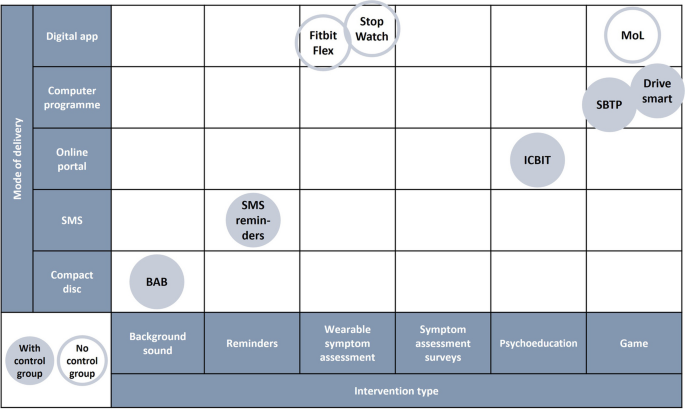

The database searches identified 2498 records (Medline, Embase and Cochrane Library yielded 915, 1356, and 227 records respectively). From these, a total of nine records were identified for inclusion [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ], see the PRISMA flow diagram for details (Additional File 1). The included studies have publication dates ranging from 2010 to 2022. Five studies were conducted in the USA, with Denmark, Sweden, Israel, and Australia also being home to one study each. Details related to the samples, intervention types and mode of delivery are provided in Table 4 . Only two RCTs were identified [ 23 , 25 ], and four pilot studies [ 22 , 25 , 26 , 29 ]. Intervention types included three gamified interventions [ 22 , 23 , 28 ], two wearable symptom monitoring devices [ 26 , 29 ], one psychoeducation programme [ 27 ], one medication reminder service [ 21 ], one symptom monitoring survey [ 24 ] and one background sound [ 25 ]. Three interventions were delivered using a digital app [ 26 , 27 , 29 ], two using an online portal [ 24 , 27 ], two via computer programmes [ 22 , 23 ], one via SMS text messaging [ 21 ], and one via compact disc [ 25 ]. The intervention type and mode of delivery for each identified intervention are visualised in Fig. 3 . The Fitbit Flex intervention evaluated by Schoenfelder et al., was delivered primarily via a digital app, but combined delivery methods by also using an invite only Facebook group which allowed participants to interact with facilitators and other participants to receive encouragement, social support, and rewards for meeting goals. This DHI aimed to promote physical activity and reduce ADHD symptoms. Participants wore a wearable activity tracker (Fitbit Flex), which collected data about energy and movement, and then synced to a mobile app that provided participants with visualisations of the data and feedback towards goals.

Visual representation of types of digital health intervention identified in the scoping review. Interventions identified were binaural auditory beats (BAB) [ 25 ], SMS text reminders [ 21 ], Fitbit Flex movement tracking [ 29 ], StopWatch movement tracking [ 26 ], Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) [ 24 ], Internet-based self-help comprehensive behavioural intervention for tics (ICBIT) [ 27 ], Method of Loci (MoL) [ 28 ], Scientific brain training programme (SBTP) [ 22 ], and Drive Smart [ 23 ]

Of the nine interventions identified, six measured ADHD symptoms as the target for their intervention [ 22 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. The remaining three were designed to target different outcomes which may be negatively affected by ADHD: hazard perception while driving, homework problems, and medication engagement [ 21 , 23 , 25 ].

All studies provided interim results which showed improvements in ADHD outcomes, although two studies found no significant group differences between the intervention and control groups: one tested a computerised brain training exercise against a control of Tetris, and one used binaural auditory beats against a placebo sound [ 22 , 25 ]. Four studies did not use a control group, due to being feasibility or pilot studies focussed on intervention acceptability, hence it is difficult to determine whether the outcomes of these studies are a result of the intervention or another variable [ 24 , 26 , 28 , 29 ].

Some common barriers to implementing interventions were reported, with suggestions for addressing these. These included having a lack of sustained attention whilst trying to do the intervention and forgetting to do it [ 22 , 28 ]. Interventions which offered reminders were deemed as useful by participants, but participants recommended increasing the number of reminders [ 22 , 28 , 29 ]. Another recommendation was ensuring that images are interesting to the relevant age group and modernised, as some of the interventions were initially developed for different age groups or developed years prior to the studies being conducted [ 22 , 23 , 26 , 28 ].

This mixed methods study aimed to find out about the needs and expectations of people with lived experience with regards to information resources, and the current availability of DHIs, to inform the future development and implementation of DHIs for young people with ADHD. The findings from our survey show that digital apps would be deemed the most useful by young people with ADHD and their supporters, followed by support groups. Interestingly, results also show that respondents stated a preference for printed materials over websites. Results from questions about signposting of resources show that young people with ADHD and their supporters would find signposting to any information resource from GPs useful, with little difference between resource types.

The scoping review identified literature relating to nine DHIs relevant to young people with ADHD. The review identified some common factors which influence acceptability and implementation of ADHD interventions, including difficulty engaging in interventions due to a lack of sustained attention; increasing engagement and participation using more reminders and up-to-date visuals; and ensuring interventions are tailored to the target age group.

From the results, three key implications for the future development of DHIs have been identified and are discussed below.

Enhance digital delivery using social support

Based on the finding that a digital app followed by a support group would be considered the most useful intervention for people with lived experience, the Fitbit Flex intervention which combines these two elements identified in the scoping review is noteworthy [ 29 ]. Evidence shows that support groups and peer support, including closed Facebook groups, can improve mental health outcomes and symptom self-management in adolescents [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ]. They provide users with social connectedness, empowerment, and the ability to learn from others [ 30 , 33 ]. However, this research is limited to few empirical studies, especially with regards to the use for support groups for ADHD. The Fitbit Flex study by Schoenfelder et al. was a feasibility trial [ 29 ]. Although the results show that there was a significant increase in physical activity, and a decrease in self- and parent-reported ADHD symptoms, it requires more testing and development to determine efficacy and an investigation into the active components that may be leading to an improvement in symptoms. Conversely, an open-label pilot study also identified in the scoping review, which aimed to test the ability of a wearable activity tracker device to treat hyperactivity, also observed an improvement in ADHD symptoms despite not utilising a social support element [ 26 ]. Overall, the evidence shows promise in improving ADHD symptoms using wearable monitoring devices and combined with results from the survey shows that enhancing the delivery of digital apps with online social support may be effective and meet the needs of people with lived experience.

Increase engagement using up-to-date, multimodal communication methods

Respondents reported that they most frequently access information from websites, despite websites being regarded as the least useful information resource. Printed materials were reported as useful by more respondents than websites. This is in line with previous research, which shows that printed patient education information is deemed more acceptable to patients than digital print [ 34 ]. Online information is perceived as more difficult to read than the equivalent information in printed format [ 34 ]. Additionally, for people with ADHD comprehension of written information is worse when the information is delivered digitally rather than in print [ 35 ]. Another study of how people prefer to receive healthcare information found that participants value a combination of written, audio and video materials, suggesting that the most useful source of information would utilise multimodal communication methods [ 36 ]. It is important to consider some limitations of these studies – the samples were small, and from limited populations, such as a single clinic, university, or level of education, which limits the generalisability of the results. Nonetheless, these findings are of interest for the development of DHIs for young people with ADHD, because they suggest that DHIs may not be useful as sources of written information about ADHD. If used as information resources, DHIs should use multimodal methods of communication.

DHIs may also be more useful when they involve active participation and/or gamified tasks, rather than being designed as information sources. However, one of the common barriers of implementing some gamified DHIs identified in the scoping review was that difficulties with sustained attention limits the use of certain apps [ 22 , 28 , 29 ]. Ensuring that graphics and user interfaces are modern and visually appealing; interventions are tailored to the target age range; and having adequate reminder messages/systems in place were suggestions from participants. This may attract more attention from young people with ADHD, enabling them to stay engaged and complete the intervention.

Ensure interventions are acceptable to GPs and other health practitioners

Finally, when asked what would be useful to be signposted to from GPs, people with lived experience had little preference for information resource type, but each resource was identified as “would be useful” to hear about by over 40% of respondents. A previous study of information resource preference found that health professionals are viewed by parents as a trusted source of information about ADHD [ 37 ]. These results imply that resource type is less important to people so long as the recommendation comes from a credible source. The implementation of information provided by a credible source is a recognised behaviour change technique, which increases uptake of behaviours [ 38 ]. Similarly, to Sciberras et al . we asked participants about information sources and modes of information, but Sciberras et al . also asked participants about the quality and content of information [ 37 ]. This enabled data to be collected regarding the reasons why certain sources are deemed as preferential over others, whereas our study does not allow these inferences to be drawn. Data from a future qualitative study would be beneficial, to provide a rich and in-depth understanding of the preferences of people with lived experience concerning information resources.

Nevertheless, this finding is of interest because it shows that interventions should not only be deemed acceptable by young people, but also by GPs. Research shows that where GPs have a lack of knowledge about a treatment for ADHD, they are left unwilling to prescribe it to young people [ 39 ]. This is supported by a systematic review of GPs as gatekeepers to diagnosis and treatment for people with ADHD, which found that there was a general reluctance by GPs to become involved in the treatment of ADHD – oftentimes due to a lack of time and knowledge [ 11 ]. Thus, if an intervention is viewed as being time-saving and easy for GPs to understand and operate, it may be more acceptable to them, and so they may be more likely to engage and prescribe it or signpost patients towards it.

Outstanding questions for future research

The survey we have reported on here was also shared with health practitioners with questions tailored to them regarding which information resources they currently signpost young people with ADHD to, and what information resources they would find useful to help them make clinical decisions about the care of young people with ADHD. During the screening phase of the scoping review, the researchers observed multiple texts about DHIs which could be useful to health practitioners for the management of ADHD in primary care, which suggests there is a body of evidence for tools that might assist with clinical decision making. Thus, it may be beneficial to conduct a similar study with the target population of health practitioners in primary care who are involved in the management of ADHD.

A key finding from the scoping review is that relatively few studies focus on the development of interventions for adolescents and young people with ADHD. Other systematic reviews in this area of research find interventions aimed at younger populations, but the evidence for people aged 16–25 is limited [ 17 , 19 ]. This was the first review to exclusively focus on this age range, and only nine papers were yielded. Given the importance of transition into adulthood for people with ADHD, developing interventions for this age group should be of high priority. In addition, while many of the results from the included studies were promising, they were generally limited to open-label, non-randomised or pilot and feasibility trials, which demonstrates the need for robust randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which have adequate statistical power to measure the true efficacy of currently available DHIs.

Strengths and limitations

This analysis provides the first overview of stakeholder reported views on the provision of information resources to help young people self-manage their ADHD in England. Additionally, the scoping review is the first to scope out the development of resources specifically for young people with ADHD in the target age range, 16–25 years old, identifying facilitators and barriers for use of resources in primary care. The methods of disseminating the survey link, including utilising the mailing lists of partner organisations and charities enabled us to reach more than the target number of responses and resulted in a good geographic spread of data with at least six respondents from each ICB in England. However, despite reaching a high number of respondents in each ICB, the survey may not be nationally representative due to the low number of responses relative to the number of people in England with ADHD. Furthermore, participants were not randomly selected due to the use of non-probabilistic sampling strategies.

The survey also did not collect demographic information, such as gender, ethnic origin, or age because our priority was keeping the survey short and accessible for people with ADHD, who often have attentional difficulties. Our lack of detailed demographic information limits the generalisability of this sample. It is also possible that the non-probabilistic methods used to sample respondents introduced responder bias. Respondents may have been more likely to complete the survey if they have had extremely negative or positive experiences with their GPs that they wanted to share, so the views presented here may not be reflective of the rest of the population. In addition, most of the advertising for the survey was done online, so respondents had to have access to a computer or mobile device and be computer literate. Furthermore, since participants could be any age over 16, it is difficult to tell whether results exclusively pertain to the experiences of young people aged 16–25, despite framing the context of the research as such prior to the survey and in the wording of survey questions. Results are also susceptible to recall bias should participants over the age of 25 be reflecting on experiences from when they were aged between 16–25.

In addition to limitations regarding the age-range of participants in our survey sample, we also acknowledge the broad age range of participants in included studies in the scoping review which may limit the relevance of findings to people aged 16–25. Due to an underdeveloped body of literature regarding young people with ADHD between the ages of 16–25, this research took an inclusive approach to eligibility of studies which included participants outside of our population of interest. While this enabled us to identify interventions which are being developed/evaluated that may be relevant to this age range, the inclusion of studies which have a mean participant age outside of our population of interest may skew results and impede the ability to draw conclusions for individuals aged 16–25. Quality assessments of the records included in the scoping review were also not performed because this study aimed to identify the scope of the available evidence. The results were synthesised narratively, with some general shortcomings of the evidence highlighted. However, it would be beneficial to conduct a full systematic review which maintains a narrower inclusion criteria regarding age of participants and includes rigorous quality evaluation to fully assess the state of the evidence base regarding current development and provision of DHIs for the management of ADHD symptoms for young people with ADHD. A future systematic review on the same topic is planned [ 40 ].

This study investigates the current availability of peer reviewed research on DHIs for young people and ADHD with the preferences of people with lived experience. The scoping review findings highlight that people aged 16–25 with ADHD are an underrepresented population in research into DHIs. By enhancing DHIs using social support groups, we may be able to develop more acceptable DHIs which meet the unique needs of this population. In addition, DHIs as information resources may be optimised by avoiding written text and by using multimodal communication methods. Lastly, people with lived experience may value more signposting from their GPs to information resources, as GPs act as a credible source of information. Thus, interventions also need to be acceptable to GPs to ensure they are willing to prescribe or signpost patients towards them. Further research is required to evaluate and understand the preferences of stakeholders with regards to information resources, and RCTs are necessary to improve the robustness of the evidence base for using DHIs to help people aged 16–25 self-manage their ADHD.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Digital health intervention

National Health Service

General practitioner

Integrated care board

Mapping ADHD services in primary care

Confidence interval

Randomised controlled trial

Polanczyk G, De Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Di Lorenzo R, Balducci J, Poppi C, Arcolin E, Cutino A, Ferri P, et al. Children and adolescents with ADHD followed up to adulthood: a systematic review of long-term outcomes. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2021;33(6):283–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2021.23 .

Shaw M, Hodgkins P, Caci H, Young S, Kahle J, Woods AG, et al. A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatment. BMC Med. 2012;10(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-10-99 .

Article Google Scholar

Cortese S, Adamo N, Del Giovane C, Mohr-Jensen C, Hayes AJ, Carucci S, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(9):727–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30269-4 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Catalá-López F, Hutton B, Núñez-Beltrán A, Page MJ, Ridao M, Saint-Gerons DM, et al. The pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review with network meta-analyses of randomised trials. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7): e0180355. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180355 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Asherson P, Leaver L, Adamou M, Arif M, Askey G, Butler M, et al. Mainstreaming adult ADHD into primary care in the UK: guidance, practice, and best practice recommendations. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):640. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04290-7 .

Philipsen A, Jans T, Graf E, Matthies S, Borel P, Colla M, et al. Effects of group psychotherapy, individual counseling, methylphenidate, and placebo in the treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72(12):1199–210. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2146 .

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people and adults. London: NICE; 2018. p. 61. [NG87]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87 . Cited 2022 Oct 27

Biederman J, Fried R, DiSalvo M, Storch B, Pulli A, Yvonne Woodworth K, et al. Evidence of low adherence to stimulant medication among children and youths with ADHD: an electronic health records study. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(10):874–80. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800515 .

Price A, Janssens A, Newlove-Delgado T, Eke H, Paul M, Sayal K, et al. Mapping UK mental health services for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: national survey with comparison of reporting between three stakeholder groups. BJPsych Open. 2020;6(4): e76. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.65 .

Tatlow-Golden M, Prihodova L, Gavin B, Cullen W, McNicholas F. What do general practitioners know about ADHD? Attitudes and knowledge among first-contact gatekeepers: systematic narrative review. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0516-x .

Eke H, Ford T, Newlove-Delgado T, Price A, Young S, Ani C, et al. Transition between child and adult services for young people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): findings from a British national surveillance study. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;217(5):616–22. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.131 .

Young S, Adamou M, Asherson P, Coghill D, Colley B, Gudjonsson G, et al. Recommendations for the transition of patients with ADHD from child to adult healthcare services: a consensus statement from the UK adult ADHD network. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1013-4 .

Young S, Asherson P, Lloyd T, Absoud M, Arif M, Colley WA, et al. Failure of healthcare provision for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United Kingdom: a consensus statement. Front Psychiatry. 2021;19(12):649399. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.649399 .

NHS England. Primary care networks. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/primary-care-networks/ . Cited 2023 Apr 7

NHS England. What are integrated care systems? Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/integratedcare/what-is-integrated-care/ . Cited 2023 Apr 7

Shou S, Xiu S, Li Y, Zhang N, Yu J, Ding J, et al. Efficacy of online intervention for ADHD: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Front Psychol. 2022;28(13):854810. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.854810 .

Kollins SH, Childress A, Heusser AC, Lutz J. Effectiveness of a digital therapeutic as adjunct to treatment with medication in pediatric ADHD. NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4(1):58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-021-00429-0 .

Lakes KD, Cibrian FL, Schuck SEB, Nelson M, Hayes GR. Digital health interventions for youth with ADHD: a mapping review. Comput Hum Behav Reports. 2022;1(6): 100174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100174 .

Price A, Smith JR, Mughal F, Salimi A, Melendez-Torres GJ, Newlove-Delgado T. Protocol for the mixed methods Managing young people with Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Primary care (MAP) study: mapping current practice and co-producing guidance to improve healthcare in an underserved population. BMJ Open. 2023;10(13): e068184. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068184 .

Biederman J, Fried R, DiSalvo M, DHIscoll H, Green A, Biederman I, et al. A novel digital health intervention to improve patient engagement to stimulants in adult ADHD in the primary care setting: preliminary findings from an open label study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113158 .

Bikic A, Christensen TØ, Leckman JF, Bilenberg N, Dalsgaard S. A double-blind randomized pilot trial comparing computerized cognitive exercises to Tetris in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2017;71(6):455–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2017.1328070 .

Bruce CR, Unsworth CA, Dillon MP, Tay R, Falkmer T, Bird P, et al. Hazard perception skills of young DHIvers with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) can be improved with computer based DHIver training: an exploratory randomised controlled trial. Accid Anal Prev. 2017;1(109):70–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2017.10.002 .

Kennedy TM, Molina BSG, Pedersen SL. Change in adolescents’ perceived ADHD symptoms across 17 days of ecological momentary assessment. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2096043 .

Kennel S, Taylor AG, Lyon D, Bourguignon C. Pilot feasibility study of binaural auditory beats for reducing symptoms of inattention in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr Nurs. 2009;25(1):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2008.06.010 .

Leikauf JE, Correa C, Bueno AN, Sempere VP, Williams LM. StopWatch: pilot study for an Apple watch application for youth with ADHD. Digit Heal. 2021;1:7. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076211001215 .

Rachamim L, Mualem-Taylor H, Rachamim O, Rotstein M, Zimmerman-Brenner S. Acute and long-term effects of an internet-based, self-help comprehensive behavioral intervention for children and teens with tic disorders with comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or obsessive compulsive disorder: a reanalysis of data from a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med. 2021;11(1): 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11010045 .

Ruchkin V, Wallonius M, Odekvist E, Kim S, Isaksson J. Memory training with the method of loci for children and adolescents with ADHD—a feasibility study. Appl Neuropsychol Child. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622965.2022.2141120 . Cited 2023 Mar 13.

Schoenfelder E, Moreno M, Wilner M, Whitlock KB, Mendoza JA. Piloting a mobile health intervention to increase physical activity for adolescents with ADHD. Prev Med Reports. 2017;1(6):210–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.03.003 .

Halsall T, Daley M, Hawke L, Henderson J, Matheson K. “You can kind of just feel the power behind what someone’s saying”: a participatory-realist evaluation of peer support for young people coping with complex mental health and substance use challenges. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1358. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08743-3 .

Hixenbaugh P, Dewart H, Drees D, Williams D. Peer E-mentoring: enhancement of the first year experience. Psychol Learn Teach. 2006;5(1):8–14. https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2005.5.1.8 .

Griffiths KM, Mackinnon AJ, Crisp DA, Christensen H, Bennett K, Farrer L. The effectiveness of an online support group for members of the community with depression: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12): e53244. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053244 .

Watkins DC, Allen JO, Goodwill JR, Noel B. Strengths and weaknesses of the Young Black Men, Masculinities, and Mental Health (YBMen) Facebook project. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2017;87(4):392–401. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000229 .

Farnsworth M. Differences in perceived difficulty in print and online patient education materials. Perm J. 2014;18(4):45–50. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/14-008 .

Ben-Yehudah G, Brann A. Pay attention to digital text: the impact of the media on text comprehension and self-monitoring in higher-education students with ADHD. Res Dev Disabil. 2019;89:120–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.04.001 .

Krontoft A, Krontoft A. How do patients prefer to receive patient education material about treatment, diagnosis and procedures? —A survey study of patients preferences regarding forms of patient education materials; leaflets, podcasts, and video. Open J Nurs. 2021;11(10):809–27. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2021.1110068 .

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6 .

Sciberras E, Iyer S, Efron D, Green J. Information needs of parents of children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2010;49(2):150–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922809346730 .

Salt N, Parkes E, Scammell A. GPs’ perceptions of the management of ADHD in primary care: a study of Wandsworth GPs. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2005;6(2):162–71. https://doi.org/10.1191/1463423605pc239oa .

Price A, Gudka R. What is the available evidence for digital health interventions providing healthcare information and self-management resources to young people (aged 16 to 25) with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? PROSPERO. 2023;CRD42023458822. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023458822

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who have contributed to this study, including the healthcare professionals, and people with ADHD and their supporters who have been involved in the conception and planning of this research. Also, the colleagues, collaborators, and research partners that have supported every aspect of this study.

This project is funded by an NIHR Three School’s Mental Health Research Fellowship (MHF008). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. This project is supported by the NIHR Clinical Research Network South West Peninsula.

TND was supported by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Advanced Fellowship during the preparation of this paper (NIHR300056).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Exeter Medical School, Exeter, EX1 2LU, UK

Rebecca Gudka, Kieran Becker, Tamsin Newlove-Delgado & Anna Price

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AP and TND conducted development work to conceptualise the research idea. All authors actively contributed to the research design. RG analysed and interpreted the data from the national survey and coordinated the scoping review. RG, KB and AP contributed to scoping review screening and study selection. AP and TND provided academic mentorship. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rebecca Gudka .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The project was given ethical approval by the Yorkshire and the Humber – Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 22/YH/0132). All survey participants gave informed consent to participate and informed consent for their data to be used in this study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

44247_2024_129_moesm1_esm.docx.

Additional file 1. Additional scoping review methods A – Scoping review full search strategy, B – Full inclusion and exclusion criteria for identified studies, C – PRISMA flow diagram of search and screening results.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gudka, R., Becker, K., Newlove-Delgado, T. et al. Provision of digital health interventions for young people with ADHD in primary care: findings from a survey and scoping review. BMC Digit Health 2 , 71 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-024-00129-1

Download citation

Received : 31 October 2023

Accepted : 17 July 2024

Published : 08 October 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s44247-024-00129-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Young people

- Primary Health Care

- Digital mental health interventions

- Health information provision

- Mixed methods study

BMC Digital Health

ISSN: 2731-684X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Digital Homework Activities is an activity that trains and consolidates knowledge in the form of games, stimulates the joy of learning English and encourages the ability to self-study with engaging content, vivid images, combined with audiovisuals. , listening, listening and typing to help students become familiar with using computers in ...

Thông tin về ứng dụng này. Digital Homework Activities là một trong những cách tuyệt vời và hiệu quả để giúp học sinh ôn tập và rèn luyện tiếng Anh tại nhà. Các hoạt động được thiết kế phong phú đa dạng, hình ảnh sinh động, vui nhộn giúp học sinh nâng cao khả năng ngôn ...

Bước 2: Tải xuống file cài đặt của Digital Homework Activities cho máy tính PC Windows. Tải file cài đặt của Digital Homework Activities tại phần đầu của trang web này, file cài đặt này có đuôi là .APK hoặc .XAPK. Chú ý: Bạn cũng có thể tải về Digital Homework Activities apk phiên bản ...

Digital Homework Activities is an amazingly effective way to help students review and practice English at home. The students can improve their language abilities easily due to various lively games designed in pursuit of strengthening their language. Main features of this app: • The app is designed…

Digital Homework Activities is free Education app, developed by DTP Online Corporation. Latest version of Digital Homework Activities is 2.76, was released on 2023-12-11 (updated on 2024-04-20). Estimated number of the downloads is more than 50,000. Overall rating of Digital Homework Activities is 4,3.

Digital Homework Activities APP. Digital Homework Activities là một trong những cách tuyệt vời và hiệu quả để giúp học sinh ôn tập và rèn luyện tiếng Anh tại nhà. Các hoạt động được thiết kế phong phú đa dạng, hình ảnh sinh động, vui nhộn giúp học sinh nâng cao khả năng ngôn ...

Digital Homework Activities is an activity that trains and consolidates knowledge in the form of games, stimulates the joy of learning English and encourages the ability to self-study with engaging content, vivid images, combined with audiovisuals. , listening, listening and typing to help students become familiar with using computers in ...