How to Write the Community Essay: Complete Guide + Examples

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Step 1: Decide What Community to Write About

- Step 2: The BEABIES Exercise

- Step 3: Pick a Structure (Narrative or Montage)

- Step 4: Write a Draft!

Introduction

On the Common Application, a number of colleges have begun to require that students respond to a supplemental essay question that sounds something like this:

Tell us a bit more about a community you are a part of.

Here is the exact wording from a few schools:

University of Michigan: “Everyone belongs to many different communities and/or groups defined by (among other things) shared geography, religion, ethnicity, income, cuisine, interest, race, ideology, or intellectual heritage. Choose one of the communities to which you belong, and describe that community and your place within it. (250 words)”

Duke University: “We seek a talented, engaged student body that embodies the wide range of human experience; we believe that the diversity of our students makes our community stronger. If you'd like to share a perspective you bring or experiences you've had to help us understand you better—perhaps related to a community you belong to, your sexual orientation or gender identity, or your family or cultural background—we encourage you to do so. Real people are reading your application, and we want to do our best to understand and appreciate the real people applying. (250 words)

(Old) Brown University: “Tell us about a place or community you call home. How has it shaped your perspective? (250 words)

I love this essay question.

Why? Because, while this essay is largely asking about your place within that community, it is a great opportunity to share more about you, and how you will most likely engage with that community (or other communities) on your future college campus.

It’s a chance to say: “Here’s how I connect with folks in this community. And if accepted to your college, I’ll probably be active in getting involved with that same community and others on your college campus.”

And colleges want students who are going to be active in engaging with their community.

How to Write The Community Essay

Step 1: decide what community you want to write about.

How? This may seem obvious, but it can be really helpful to first brainstorm the communities you’re already a part of.

Here’s how:

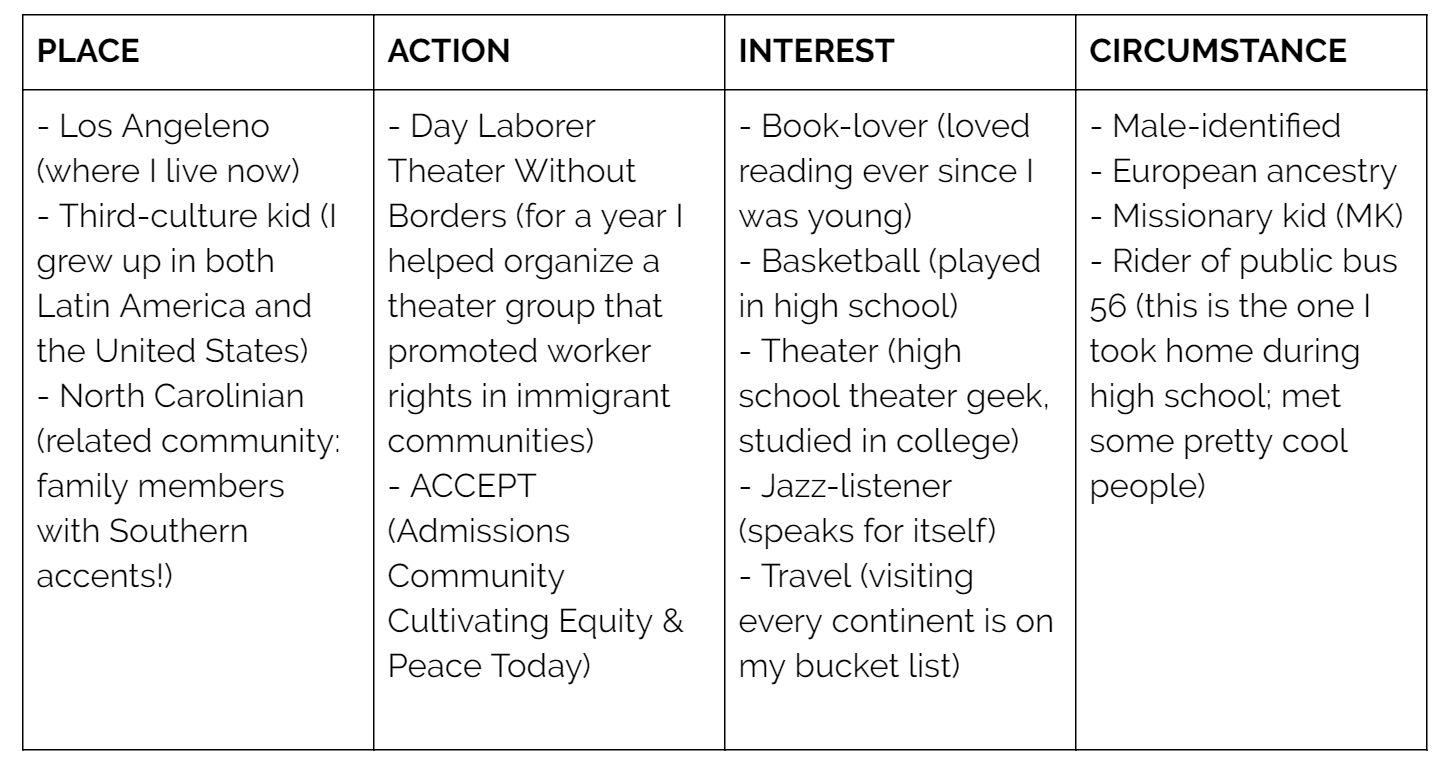

Create a “communities” chart by listing all the communities you’re a part of. Keep in mind that communities can be defined by...

Place: groups of people who live/work/play near one another

Action: groups of people who create change in the world by building, doing, or solving something together (Examples: Black Lives Matter, Girls Who Code, March for Our Lives)

Interest: groups of people coming together based on shared interest, experience, or expertise

Circumstance: groups of people brought together either by chance or external events/situations

Use four columns in your chart, like this.

Your turn.

What communities are you a part of?

Spend 5-10 minutes making a list of as many as you can think of.

In fact, here’s a simple GoogleDoc you can download and fill in right now.

Once you’ve completed that exercise for several of the communities you are a part of, you might start to see one community seems to be the most obvious one to write about.

Go with the one that you feel gives the best chance to help you share more about yourself.

Step 2: Use the BEABIES exercise to generate your essay content

Once you’ve chosen a community or two, map out your content using the BEABIES Exercise . That exercise asks:

What did you actually do in that community? (Tip: use active verbs like “organized” and “managed” to clarify your responsibilities).

What kinds of problems did you solve (personally, locally, or globally)?

What specific impact did you have?

What did you learn (skills, qualities, values)?

How did you apply the lessons you learned in and outside of that community?

Don’t skip that step. It’s important.

Step 3: Pick a structure (Narrative or Montage)

The Narrative Structure . This structure works well for students who have faced a challenge in this community. Otherwise, the Montage Structure works well.

Consider answering these three questions in your essay if you choose the Narrative Structure:

What challenge did you face?

What did you do about it?

What did you learn?

Here’s an example of a narrative “community” essay based on a challenge that tackles those three questions, roughly in order:

Community Essay Example: East Meets West

I look around my room, dimly lit by an orange light. On my desk, a framed picture of an Asian family beaming their smiles, buried among US history textbooks and The Great Gatsby. A Korean ballad streams from two tiny computer speakers. Pamphlets of American colleges scattered on the floor. A cold December wind wafts a strange infusion of ramen and leftover pizza. On the wall in the far back, a Korean flag hangs besides a Led Zeppelin poster. Do I consider myself Korean or American? A few years back, I would have replied: “Neither.” The frustrating moments of miscommunication, the stifling homesickness, and the impossible dilemma of deciding between the Korean or American table in the dining hall, all fueled my identity crisis. Standing in the “Foreign Passports” section at JFK, I have always felt out of place. Sure, I held a Korean passport in my hands, and I loved kimchi and Yuna Kim and knew the Korean Anthem by heart. But I also loved macaroni and cheese and LeBron. Deep inside, I feared I’d labeled by my airport customs category: a foreigner everywhere. This ambiguity, however, has granted me the opportunity to absorb the best of both worlds. Look at my dorm room. This mélange of cultures in my East-meets-West room embodies the diversity that characterizes my international student life. I’ve learned to accept my “ambiguity” as “diversity,” as a third-culture student embracing both identities. Do I consider myself Korean or American? Now, I can proudly answer: “Both.” — — —

(250 words)

While this author doesn’t go into too much depth on the “What did you do about it?” question named above, we do get a sense of the challenge he faced and what he learned.

For more on how to use the narrative structure, check out the free guide to writing the personal statement.

The Montage Structure. This is another potential structure, often times great for essays that don’t necessarily focus on a particular challenge.

Here’s a great example:

Community Essay Example: Storytellers

Storytellers (Montage Structure)

I belong to a community of storytellers. Throughout my childhood, my mother and I spent countless hours immersed in the magical land of bedtime stories. We took daring adventures and explored far away lands. Imagination ran wild, characters came to life, and I became acquainted with heroes and lessons that continue to inspire me today. It was a ritual that I will never forget. In school I met many other storytellers—teachers, coaches, and fellow students whose stories taught me valuable lessons and enabled me to share stories of my own. My stories took shape through my involvement with theatre. I have learned that telling stories can be just as powerful as hearing them. When I tell a story, I can shape the world I live in and share my deepest emotions with the audience. This is exactly why I love theatre so much. The audience can relate to the story in many of the same powerful ways that I do. I love to perform with my theatre class to entertain and educate young audiences throughout my community. To tell our stories, we travel to elementary and middle schools performing plays that help educate younger students of the dangers of drugs, alcohol, and bullying. As storytellers, we aim to touch lives and better the world around us through our stories. — — —

(219 words)

To write this essay, I recommend the “uncommon connections” exercise.

The Uncommon Connections Exercise

First: Use the Values Exercise at this link to brainstorm predictable values that other students might describe in their essay and then vow not to use those values.

Second : Identify 3-4 uncommon connections (values other students would be unlikely to think of) and give an example of each.

Third : Describe one example per paragraph, perhaps in chronological order.

Another idea: It’s also possible to combine the narrative and montage structures by describing a challenge WHILE also describing a range of values and lessons.

Here’s an example that does this:

Community Essay Example: The Pumpkin House (plus Ethan's analysis)

The Pumpkin House (Narrative + Montage Combo Structure)

I was raised in “The Pumpkin House.” Every Autumn, on the lawn between the sidewalk and the road, grows our pumpkin. Every summer, we procure seeds from giant pumpkins and plant them in this strip of land. Every fall, the pumpkin grows to be giant. This annual ritual became well known in the community and became the defining feature of our already quirky house. The pumpkin was not just a pumpkin, but a catalyst to creating interactions and community. Conversations often start with “aren’t you the girl in the pumpkin house?” My English teacher knew about our pumpkin and our chickens. His curiosity and weekly updates about the pumpkin helped us connect.

The author touches on the values of family and ritual in the first few sentences. She then mentions the word “community” explicitly, which clearly connects the essay to the prompt. In the second paragraph she mentions the value of connection.

One year, we found our pumpkin splattered across the street. We were devastated; the pumpkin was part of our identity. Word spread, and people came to our house to share in our dismay. Clearly, that pumpkin enriched our life and the entire neighborhoods’.

Here she introduces the problem. Then she raises the stakes: the pumpkin was part of her family’s identity as well as that of the community.

The next morning, our patch contained twelve new pumpkins. Anonymous neighbors left these, plus, a truly gigantic 200 lb. pumpkin on our doorstep.

Describing the neighborhood’s response offers a vivid example of what makes for a great community.

Growing up, the pumpkin challenged me as I wasn’t always comfortable being the center of attention. But in retrospect, I realize that there’s a bit of magic in growing something from a seed and tending it in public. I witnessed how this act of sharing creates authentic community spirit. I wouldn’t be surprised if some day I started my own form of quirky pumpkin growing and reap the benefit of true community.

The author makes another uncommon connection in her conclusion with the unexpected idea that “the pumpkin challenged [her].” She then uses beautiful language to reflect on the lessons she learned: “there’s a bit of magic in growing something from a seed and tending it in public.”

Step 4: Write a first draft!

It sometimes helps to outline and draft one or two different essays on different activities, just to see which community might end up being a better topic for your essay.

Not sure? Share your drafts with a friend or teacher and ask this question:

Which of these essays tells you more about me/my core values, helps me stand out, and shows that I’ll engage actively with other communities in college.

Happy writing.

How to Write the Community Essay – Guide with Examples (2023-24)

September 6, 2023

Students applying to college this year will inevitably confront the community essay. In fact, most students will end up responding to several community essay prompts for different schools. For this reason, you should know more than simply how to approach the community essay as a genre. Rather, you will want to learn how to decipher the nuances of each particular prompt, in order to adapt your response appropriately. In this article, we’ll show you how to do just that, through several community essay examples. These examples will also demonstrate how to avoid cliché and make the community essay authentically and convincingly your own.

Emphasis on Community

Do keep in mind that inherent in the word “community” is the idea of multiple people. The personal statement already provides you with a chance to tell the college admissions committee about yourself as an individual. The community essay, however, suggests that you depict yourself among others. You can use this opportunity to your advantage by showing off interpersonal skills, for example. Or, perhaps you wish to relate a moment that forged important relationships. This in turn will indicate what kind of connections you’ll make in the classroom with college peers and professors.

Apart from comprising numerous people, a community can appear in many shapes and sizes. It could be as small as a volleyball team, or as large as a diaspora. It could fill a town soup kitchen, or spread across five boroughs. In fact, due to the internet, certain communities today don’t even require a physical place to congregate. Communities can form around a shared identity, shared place, shared hobby, shared ideology, or shared call to action. They can even arise due to a shared yet unforeseen circumstance.

What is the Community Essay All About?

In a nutshell, the community essay should exhibit three things:

- An aspect of yourself, 2. in the context of a community you belonged to, and 3. how this experience may shape your contribution to the community you’ll join in college.

It may look like a fairly simple equation: 1 + 2 = 3. However, each college will word their community essay prompt differently, so it’s important to look out for additional variables. One college may use the community essay as a way to glimpse your core values. Another may use the essay to understand how you would add to diversity on campus. Some may let you decide in which direction to take it—and there are many ways to go!

To get a better idea of how the prompts differ, let’s take a look at some real community essay prompts from the current admission cycle.

Sample 2023-2024 Community Essay Prompts

1) brown university.

“Students entering Brown often find that making their home on College Hill naturally invites reflection on where they came from. Share how an aspect of your growing up has inspired or challenged you, and what unique contributions this might allow you to make to the Brown community. (200-250 words)”

A close reading of this prompt shows that Brown puts particular emphasis on place. They do this by using the words “home,” “College Hill,” and “where they came from.” Thus, Brown invites writers to think about community through the prism of place. They also emphasize the idea of personal growth or change, through the words “inspired or challenged you.” Therefore, Brown wishes to see how the place you grew up in has affected you. And, they want to know how you in turn will affect their college community.

“NYU was founded on the belief that a student’s identity should not dictate the ability for them to access higher education. That sense of opportunity for all students, of all backgrounds, remains a part of who we are today and a critical part of what makes us a world-class university. Our community embraces diversity, in all its forms, as a cornerstone of the NYU experience.

We would like to better understand how your experiences would help us to shape and grow our diverse community. Please respond in 250 words or less.”

Here, NYU places an emphasis on students’ “identity,” “backgrounds,” and “diversity,” rather than any physical place. (For some students, place may be tied up in those ideas.) Furthermore, while NYU doesn’t ask specifically how identity has changed the essay writer, they do ask about your “experience.” Take this to mean that you can still recount a specific moment, or several moments, that work to portray your particular background. You should also try to link your story with NYU’s values of inclusivity and opportunity.

3) University of Washington

“Our families and communities often define us and our individual worlds. Community might refer to your cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood or school, sports team or club, co-workers, etc. Describe the world you come from and how you, as a product of it, might add to the diversity of the UW. (300 words max) Tip: Keep in mind that the UW strives to create a community of students richly diverse in cultural backgrounds, experiences, values and viewpoints.”

UW ’s community essay prompt may look the most approachable, for they help define the idea of community. You’ll notice that most of their examples (“families,” “cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood”…) place an emphasis on people. This may clue you in on their desire to see the relationships you’ve made. At the same time, UW uses the words “individual” and “richly diverse.” They, like NYU, wish to see how you fit in and stand out, in order to boost campus diversity.

Writing Your First Community Essay

Begin by picking which community essay you’ll write first. (For practical reasons, you’ll probably want to go with whichever one is due earliest.) Spend time doing a close reading of the prompt, as we’ve done above. Underline key words. Try to interpret exactly what the prompt is asking through these keywords.

Next, brainstorm. I recommend doing this on a blank piece of paper with a pencil. Across the top, make a row of headings. These might be the communities you’re a part of, or the components that make up your identity. Then, jot down descriptive words underneath in each column—whatever comes to you. These words may invoke people and experiences you had with them, feelings, moments of growth, lessons learned, values developed, etc. Now, narrow in on the idea that offers the richest material and that corresponds fully with the prompt.

Lastly, write! You’ll definitely want to describe real moments, in vivid detail. This will keep your essay original, and help you avoid cliché. However, you’ll need to summarize the experience and answer the prompt succinctly, so don’t stray too far into storytelling mode.

How To Adapt Your Community Essay

Once your first essay is complete, you’ll need to adapt it to the other colleges involving community essays on your list. Again, you’ll want to turn to the prompt for a close reading, and recognize what makes this prompt different from the last. For example, let’s say you’ve written your essay for UW about belonging to your swim team, and how the sports dynamics shaped you. Adapting that essay to Brown’s prompt could involve more of a focus on place. You may ask yourself, how was my swim team in Alaska different than the swim teams we competed against in other states?

Once you’ve adapted the content, you’ll also want to adapt the wording to mimic the prompt. For example, let’s say your UW essay states, “Thinking back to my years in the pool…” As you adapt this essay to Brown’s prompt, you may notice that Brown uses the word “reflection.” Therefore, you might change this sentence to “Reflecting back on my years in the pool…” While this change is minute, it cleverly signals to the reader that you’ve paid attention to the prompt, and are giving that school your full attention.

What to Avoid When Writing the Community Essay

- Avoid cliché. Some students worry that their idea is cliché, or worse, that their background or identity is cliché. However, what makes an essay cliché is not the content, but the way the content is conveyed. This is where your voice and your descriptions become essential.

- Avoid giving too many examples. Stick to one community, and one or two anecdotes arising from that community that allow you to answer the prompt fully.

- Don’t exaggerate or twist facts. Sometimes students feel they must make themselves sound more “diverse” than they feel they are. Luckily, diversity is not a feeling. Likewise, diversity does not simply refer to one’s heritage. If the prompt is asking about your identity or background, you can show the originality of your experiences through your actions and your thinking.

Community Essay Examples and Analysis

Brown university community essay example.

I used to hate the NYC subway. I’ve taken it since I was six, going up and down Manhattan, to and from school. By high school, it was a daily nightmare. Spending so much time underground, underneath fluorescent lighting, squashed inside a rickety, rocking train car among strangers, some of whom wanted to talk about conspiracy theories, others who had bedbugs or B.O., or who manspread across two seats, or bickered—it wore me out. The challenge of going anywhere seemed absurd. I dreaded the claustrophobia and disgruntlement.

Yet the subway also inspired my understanding of community. I will never forget the morning I saw a man, several seats away, slide out of his seat and hit the floor. The thump shocked everyone to attention. What we noticed: he appeared drunk, possibly homeless. I was digesting this when a second man got up and, through a sort of awkward embrace, heaved the first man back into his seat. The rest of us had stuck to subway social codes: don’t step out of line. Yet this second man’s silent actions spoke loudly. They said, “I care.”

That day I realized I belong to a group of strangers. What holds us together is our transience, our vulnerabilities, and a willingness to assist. This community is not perfect but one in motion, a perpetual work-in-progress. Now I make it my aim to hold others up. I plan to contribute to the Brown community by helping fellow students and strangers in moments of precariousness.

Brown University Community Essay Example Analysis

Here the student finds an original way to write about where they come from. The subway is not their home, yet it remains integral to ideas of belonging. The student shows how a community can be built between strangers, in their responsibility toward each other. The student succeeds at incorporating key words from the prompt (“challenge,” “inspired” “Brown community,” “contribute”) into their community essay.

UW Community Essay Example

I grew up in Hawaii, a world bound by water and rich in diversity. In school we learned that this sacred land was invaded, first by Captain Cook, then by missionaries, whalers, traders, plantation owners, and the U.S. government. My parents became part of this problematic takeover when they moved here in the 90s. The first community we knew was our church congregation. At the beginning of mass, we shook hands with our neighbors. We held hands again when we sang the Lord’s Prayer. I didn’t realize our church wasn’t “normal” until our diocese was informed that we had to stop dancing hula and singing Hawaiian hymns. The order came from the Pope himself.

Eventually, I lost faith in God and organized institutions. I thought the banning of hula—an ancient and pure form of expression—seemed medieval, ignorant, and unfair, given that the Hawaiian religion had already been stamped out. I felt a lack of community and a distrust for any place in which I might find one. As a postcolonial inhabitant, I could never belong to the Hawaiian culture, no matter how much I valued it. Then, I was shocked to learn that Queen Ka’ahumanu herself had eliminated the Kapu system, a strict code of conduct in which women were inferior to men. Next went the Hawaiian religion. Queen Ka’ahumanu burned all the temples before turning to Christianity, hoping this religion would offer better opportunities for her people.

Community Essay (Continued)

I’m not sure what to make of this history. Should I view Queen Ka’ahumanu as a feminist hero, or another failure in her islands’ tragedy? Nothing is black and white about her story, but she did what she thought was beneficial to her people, regardless of tradition. From her story, I’ve learned to accept complexity. I can disagree with institutionalized religion while still believing in my neighbors. I am a product of this place and their presence. At UW, I plan to add to campus diversity through my experience, knowing that diversity comes with contradictions and complications, all of which should be approached with an open and informed mind.

UW Community Essay Example Analysis

This student also manages to weave in words from the prompt (“family,” “community,” “world,” “product of it,” “add to the diversity,” etc.). Moreover, the student picks one of the examples of community mentioned in the prompt, (namely, a religious group,) and deepens their answer by addressing the complexity inherent in the community they’ve been involved in. While the student displays an inner turmoil about their identity and participation, they find a way to show how they’d contribute to an open-minded campus through their values and intellectual rigor.

What’s Next

For more on supplemental essays and essay writing guides, check out the following articles:

- How to Write the Why This Major Essay + Example

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay + Example

- How to Start a College Essay – 12 Techniques and Tips

- College Essay

Kaylen Baker

With a BA in Literary Studies from Middlebury College, an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, and a Master’s in Translation from Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Kaylen has been working with students on their writing for over five years. Previously, Kaylen taught a fiction course for high school students as part of Columbia Artists/Teachers, and served as an English Language Assistant for the French National Department of Education. Kaylen is an experienced writer/translator whose work has been featured in Los Angeles Review, Hybrid, San Francisco Bay Guardian, France Today, and Honolulu Weekly, among others.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Student Parent Counselor Educator Other First Name Last Name Email Address Zip Code Area of Interest Business Computer Science Engineering Fine/Performing Arts Humanities Mathematics STEM Pre-Med Psychology Social Studies/Sciences Submit

Think you can get into a top-10 school? Take our chance-me calculator... if you dare. 🔥

Last updated March 21, 2024

Every piece we write is researched and vetted by a former admissions officer. Read about our mission to pull back the admissions curtain.

Blog > Essay Advice , Supplementals > How to Write a Community Supplemental Essay (with Examples)

How to Write a Community Supplemental Essay (with Examples)

Admissions officer reviewed by Ben Bousquet, M.Ed Former Vanderbilt University

Written by Kylie Kistner, MA Former Willamette University Admissions

Key Takeaway

If you're applying to college, there's a good chance you'll be writing a Community Essay for one (or lots) of your supplementals. In this post, we show you how to write one that stands out.

This post is one in a series of posts about the supplemental essays . You can read our core “how-to” supplemental post here .

When schools admit you, they aren’t just admitting you to be a student. They’re also admitting you to be a community member.

Community supplemental essays help universities understand how you would fit into their school community. At their core, Community prompts allow you to explicitly show an admissions officer why you would be the perfect addition to the school’s community.

Let’s get into what a Community supplemental essay is, what strategies you can use to stand out, and which steps you can take to write the best one possible.

What is a Community supplemental essay?

Community supplemental essay prompts come in a number of forms. Some ask you to talk about a community you already belong to, while others ask you to expand on how you would contribute to the school you’re applying to.

Let’s look at a couple of examples.

1: Rice University

Rice is lauded for creating a collaborative atmosphere that enhances the quality of life for all members of our campus community. The Residential College System and undergraduate life is heavily influenced by the unique life experiences and cultural tradition each student brings. What life perspectives would you contribute to the Rice community? 500 word limit.

2: Swarthmore College

Swarthmore students’ worldviews are often forged by their prior experiences and exposure to ideas and values. Our students are often mentored, supported, and developed by their immediate context—in their neighborhoods, communities of faith, families, and classrooms. Reflect on what elements of your home, school, or community have shaped you or positively impacted you. How have you grown or changed because of the influence of your community?

Community Essay Strategy

Your Community essay strategy will likely depend on the kind of Community essay you’re asked to write. As with all supplemental essays, the goal of any community essay should be to write about the strengths that make you a good fit for the school in question.

How to write about a community to which you belong

Most Community essay prompts give you a lot of flexibility in how you define “community.” That means that the community you write about probably isn’t limited to the more formal communities you’re part of like family or school. Your communities can also include friend groups, athletic teams, clubs and organizations, online communities, and more.

There are two things you should consider before you even begin writing your essay.

What school values is the prompt looking for?

Whether they’re listed implicitly or explicitly, Community essay prompts often include values that you can align your essay response with.

To explain, let’s look at this short supplemental prompt from the University of Notre Dame:

If you were given unlimited resources to help solve one problem in your community, what would it be and how would you accomplish it?

Now, this prompt doesn’t outright say anything about values. But the question itself, even being so short, implies a few values:

a) That you should be active in your community

b) That you should be aware of your community’s problems

c) That you know how to problem-solve

d) That you’re able to collaborate with your community

After dissecting the prompt for these values, you can write a Community essay that showcases how you align with them.

What else are admissions officers learning about you through the community you choose?

In addition to showing what a good community member you are, your Community supplemental essays can also let you talk about other parts of your experience. Doing so can help you find the perfect narrative balance among all your essays.

Let’s use a quick example.

If I’m a student applying to computer science programs, then I might choose to write about the community I’ve found in my robotics team. More specifically, I might write about my role as cheerleader and principle problem-solver of my robotics team. Writing about my robotics team allows me to do two things:

Show that I’m a really supportive person in my community, and

Show that I’m on a robotics team that means a lot to me.

Now, it’s important not to co-opt your Community essay and turn it into a secret Extracurricular essay , but it’s important to be thinking about all the information an admissions officer will learn about you based on the community you choose to focus on.

How to write about what you’ll contribute to your new community

The other segment of Community essays are those that ask you to reflect on how your specific experiences will contribute to your new community.

It’s important that you read each prompt carefully so you know what to focus your essay on.

These kinds of Community prompts let you explicitly drive home why you belong at the school you’re applying to.

Here are two suggestions to get you started.

Draw out the values.

This kind of Community prompt also typically contains some kind of reference to values. The Rice prompt is a perfect example of this:

Rice is lauded for creating a collaborative atmosphere that enhances the quality of life for all members of our campus community . The Residential College System and undergraduate life is heavily influenced by the unique life experiences and cultural tradition each student brings. What life perspectives would you contribute to the Rice community? 500 word limit.

There are several values here:

a) Collaboration

b) Enhancing quality of life

c) For all members of the community

d) Residential system (AKA not just in the classroom)

e) Sharing unique life experiences and cultural traditions with other students

Note that the actual question of the prompt is “What life perspectives would you contribute to the Rice community?” If you skimmed the beginning of the prompt to get to the question, you’d miss all these juicy details about what a Rice student looks like.

But with them in mind, you can choose to write about a life perspective that you hold that aligns with these five values.

Find detailed connections to the school.

Since these kinds of Community prompts ask you what you would contribute to the school community, this is your chance to find the most logical and specific connections you can. Browse the school website and social media to find groups, clubs, activities, communities, or support systems that are related to your personal background and experiences. When appropriate based on the prompt, these kinds of connections can help you show how good a fit you are for the school and community.

How to do Community Essay school research

Looking at school values means doing research on the school’s motto, mission statement, and strategic plans. This information is all carefully curated by a university to reflect the core values, initiatives, and goals of an institution. They can guide your Community essay by giving you more values options to include.

We’ll use the Rice mission statement as an example. It says,

As a leading research university with a distinctive commitment to undergraduate education, Rice University aspires to pathbreaking research , unsurpassed teaching , and contribution to the betterment of our world . It seeks to fulfill this mission by cultivating a diverse community of learning and discovery that produces leaders across the spectrum of human endeavor.

I’ve bolded just a few of the most important values we can draw out.

As we’ll see in the next section, I can use these values to brainstorm my Community essay.

How to write a Community Supplemental Essay

Step 1: Read the prompt closely & identify any relevant values.

When writing any supplemental essay, your first step should always be to closely read the prompt. You can even annotate it. It’s important to do this so you know exactly what is being asked of you.

With Community essays specifically, you can also highlight any values you think the prompt is asking you to elaborate on.

Keeping track of the prompt will make sure that you’re not missing anything an admissions officer will be on the lookout for.

Step 2: Brainstorm communities you’re involved in.

If you’re writing a Community essay that asks you to discuss a community you belong to, then your next step will be brainstorming all of your options.

As you brainstorm, keep a running list. Your list can include all kinds of communities you’re involved in.

Communities:

- Model United Nations

- Youth group

- Instagram book club

- My Discord group

Step 3: Think about the role(s) you play in your selected community.

Narrow down your community list to a couple of options. For each remaining option, identify the roles you played, actions you took, and significance you’ve drawn from being part of that group.

Community: Orchestra

These three columns help you get at the most important details you need to include in your community essay.

Step 4: Identify any relevant connections to the school.

Depending on the question the prompt asks of you, your last step may be to do some school research.

Let’s return to the Rice example.

After researching the Rice mission statement, we know that Rice values community members who want to contribute to the “betterment of our world.”

Ah ha! Now we have something solid to work from.

With this value in mind, I can choose to write about a perspective that shows my investment in creating a better world. Maybe that perspective is a specific kind of fundraising tenacity. Maybe it’s always looking for those small improvements that have a big impact. Maybe it’s some combination of both. Whatever it is, I can write a supplemental essay that reflects the values of the university.

Community Essay Mistakes

While writing Community essays may seem fairly straightforward, there are actually a number of ways they can go awry. Specifically, there are three common mistakes students make that you should be on the lookout for.

They don’t address the specific requests of the prompt.

As with all supplemental essays, your Community essay needs to address what the prompt is asking you to do. In Community essays especially, you’ll need to assess whether you’re being asked to talk about a community you’re already part of or the community you hope to join.

Neglecting to read the prompt also means neglecting any help the prompt gives you in terms of values. Remember that you can get clues as to what the school is looking for by analyzing the prompt’s underlying values.

They’re too vague.

Community essays can also go awry when they’re too vague. Your Community essay should reflect on specific, concrete details about your experience. This is especially the case when a Community prompt asks you to talk about a specific moment, challenge, or sequence of events.

Don’t shy away from details. Instead, use them to tell a compelling story.

They don’t make any connections to the school.

Finally, Community essays that don’t make any connections to the school in question miss out on a valuable opportunity to show school fit. Recall from our supplemental essay guide that you should always write supplemental essays with an eye toward showing how well you fit into a particular community.

Community essays are the perfect chance to do that, so try to find relevant and logical school connections to include.

Community Supplemental Essay Example

Example essay: robotics community.

University of Michigan: Everyone belongs to many different communities and/or groups defined by (among other things) shared geography, religion, ethnicity, income, cuisine, interest, race, ideology, or intellectual heritage. Choose one of the communities to which you belong, and describe that community and your place within it. (Required for all applicants; minimum 100 words/maximum 300 words)

From Blendtec’s “Will it Blend?” videos to ZirconTV’s “How to Use a Stud Finder,” I’m a YouTube how-to fiend. This propensity for fix-it knowledge has not only served me well, but it’s also been a lifesaver for my favorite community: my robotics team(( The writer explicitly states the community they’ll be focusing on.)) . While some students spend their after-school hours playing sports or video games, I spend mine tinkering in my garage with three friends, one of whom is made of metal.

Last year, I Googled more fixes than I can count. Faulty wires, misaligned soldering, and failed code were no match for me. My friends watched in awe as I used Boolean Operators to find exactly the information I sought.(( The writer clearly articulates their place in the community.)) But as I agonized over chassis reviews, other unsearchable problems arose.

First((This entire paragraph fulfills the “describe that community” direction in the prompt.)) , there was the matter of registering for our first robotics competition. None of us familiar with bureaucracy, David stepped up and made some calls. His maturity and social skills helped us immediately land a spot. The next issue was branding. Our robot needed a name and a logo, and Connor took it upon himself to learn graphic design. We all voted on Archie’s name and logo design to find the perfect match. And finally, someone needed to enter the ring. Archie took it from there, winning us first place.

The best part about being in this robotics community is the collaboration and exchange of knowledge.((The writer emphasizes a clear strength: collaboration within their community. It’s clear that the writer values all contributions to the team.)) Although I can figure out how to fix anything, it’s impossible to google social skills, creativity, or courage. For that information, only friends will do. I can only imagine the fixes I’ll bring to the University of Michigan and the skills I’ll learn in return at part of the Manufacturing Robotics community((The writer ends with a forward-looking connection to the school in question.)) .

Want to see even more supplemental essay examples? Check out our college essay examples post .

Liked that? Try this next.

How to Write Supplemental Essays that Will Impress Admissions Officers

How to Write a College Essay (Exercises + Examples)

Extracurricular Magnitude and Impact

"the only actually useful chance calculator i’ve seen—plus a crash course on the application review process.".

Irena Smith, Former Stanford Admissions Officer

We built the best admissions chancer in the world . How is it the best? It draws from our experience in top-10 admissions offices to show you how selective admissions actually works.

- 720-279-7577

‹‹ BACK TO BLOG

The Community Essay for the Common App Supplements

Mark montgomery.

- July 24, 2023

How do you write the community essay for the Common App? Many college applications require supplemental essays. A common supplementary question asks you to consider and write about a community to which you belong.

The definition of community is open to interpretation and can be difficult to pin down. We each belong to a wide variety of communities ranging from our family and friend groups to being members of the global community.

My Communities

For example, I belong to a bunch of different communities. I sing in a choir, so I’m part of the community of the Colorado Chorale community (and within that community, I’m a member of the tenor section). I go to see plays a lot, so I’m a member of the “theater-going” community. Birdwatching can be fun, I find, so I belong to the “community of birdwatchers.” I belong to a club or two, so I’m a member or those communities. I belong to a political party, which is a community in a sense. I went to Dartmouth , so I belong to a community of alumni, both locally and globally. Same with my grad school: my friends and I still talk about belonging to the “ Fletcher Community .”

When I lived in Hong Kong, I was a member of the American community, which was part of the large expatriate community. I speak French and live in Denver. Therefore, I’m part of the community of Denverites who speak French as a second language. I live in a specific neighborhood in the city of Denver in the State of Colorado in the United States. All of those communities define me in one way or another. Finally, at a more intimate level, I also belong to a family community that is very important to me.

Really, when you stop to think about it, we all belong to a large number of overlapping communities. Think of a Venn diagram with lots of overlapping circles—and we are at that tiny dot in the center where each of those circles overlaps.

Why write the community essay for the Common App?

Why do colleges ask you to write this community essay? In writing about community as it relates to you, you reveal important details at the core of who you are. Colleges are hoping to bring students to their campuses who will contribute in a positive way to campus culture, whether intellectually, socially, or through their extracurricular activities.

They want students who will be successful in their new community and enrich the college through their varied backgrounds, experiences, accomplishments, activities and behavior. Thus, the way you answer this prompt will help them imagine if you would be a good addition to their campus community.

Here are some examples of the community essay prompt:

- Please complete the following, and have a little fun doing so: “I appreciate my community because …” (up to 300 characters)

- At MIT , we bring people together to better the lives of others. MIT students work to improve their communities in different ways, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to being good friends. Describe one way in which you have contributed to your community, whether in your family, the classroom, your neighborhood, etc. (200-250 words)

- What have you done to make your school or your community a better place? (up to 350 words)

- Everyone belongs to many different communities and/or groups defined by (among other things) shared geography, religion, ethnicity, income, cuisine, interest, race, ideology, or intellectual heritage. Choose one of the communities to which you belong, and describe that community and your place within it. (up to 300 words)

- Macalester is a community that includes people from many different backgrounds, some who have lived around the world and others who have lived in one place their entire lives. Please write an essay about how your background, experiences, or outlook might add to the Mac community, academically and personally. (up to 500 words)*

* Note: this last prompt doesn’t ask about a community to which you currently belong, but rather asks you to reflect on what you will bring to the community. This essay is a mix of activities and community essays. However, this essay should emphasize what the applicant would add to the campus community.

The community essay vs. the community service essay

Notice that this essay is not narrowly focused on any service you might provide to your community. Of course, it is entirely possible that your involvement in a community may include some sort of involvement that helps to promote the community and the interests of its members in some way.

However, the community essay prompts do not specifically ask you to talk about this service. The prompts want you to think about what it means to “belong,” and how you conceive of yourself in the larger world. A sense of community may, indeed, lead you to act in certain ways to advance a cause, donate your time, or exert your energies to meet the needs of your community. Your actions certainly may become part of this community essay as a way to demonstrate the ways in which you identify with—and contribute to—this community. But the focus of this essay is on that sense of belonging.

Service to your community—or to someone else’s?

To put a finer point to it, it is possible to provide “community service” to communities to which we do not belong. We might donate time to the homeless community—but that does not make us homeless. We might spend time working with refugees, even if we, ourselves, are not refugees. Or while we might enjoy good health, we still might donate time to make meals for the critically ill.

So make sure that when you write the community essay you zero in on a community that defines you, and not on the service you devote to a community that is not your own.

When preparing for the community essay for the Common App, DO THESE THINGS:

Think carefully about your choice of community.

The community you choose says a lot about you. Think carefully about what message even just the choice of community might convey to your reader. In fact, you may even want to start by asking yourself “What aspects of who I am do I want the reader to know?” and then pick the community that will do that in the best possible way. Think, too, how your choice can help you differentiate yourself and share important insight into who you are.

Factors for you to consider as you brainstorm the community essay for the Common App:

- Which communities are most important to you and why?

- What do these communities say about you that you haven’t shared with your reader elsewhere in your application?

- What roles have you played in these communities?

- How would you measure the impact of your participation in these communities?

- What does your participation in these communities say about your character, qualities, and how you interact with the world around you?

- What does the overall message say about you as a future college student?

Use this as an opportunity to reveal more about yourself

This prompt isn’t just to elaborate on your community; this is another opportunity to reveal important qualities about yourself. Explain why this community is so important to you. Write about what you learned about yourself and how it has shaped who you are. Reveal how you have made contributions to this community.

Show, don’t tell

Like every essay, the details show your reader what you want them to know about you. Be specific, but selective, with the details you include. Every word should contribute to the message you want to share with your reader. If you have space, share an anecdote to help the reader visualize the qualities that you are trying to share.

Ensure you answer the prompt fully and directly

Some of these prompts are simple and short, but other schools have long prompts. Don’t get lost in answering the first part of the prompt and forget about the remainder. Re-read the prompt after you have drafted your ideas to make sure you’ve addressed everything.

In addition, sometimes, if you have multiple applications that ask a “community” question, you may be tempted to simply repurpose the same exact essay from one application to the other. Beware! Each prompt will have different nuances to it, and you will need to ensure that you are actually answering the prompt that is being asked. You can certainly re-use the content from one application to the next, but you should tailor how you express those ideas so that they match the prompt.

When drafting the community essay for the Common App, DON’T DO these things

Don’t be afraid to “think outside of the box”.

Some communities to which we belong are obvious because we participate in them on a daily basis. These would include our families and our friend groups. Others are obvious because they are clearly defined: the football team or student government. But what about those informal communities, occasional communities, or hard-to-define communities to which you might belong? Are you a crafty person who blogs about your creations with an online community?

Do you belong to a book group in your neighborhood? Are you a classic car connoisseur? Even writing about things that might not seem like natural “communities” can work quite well as long as they reveal important aspects of who you are. For example, we’ve read a successful “community” essay about a student who belonged to a community of anonymous subway riders. We read another about a community of students who wear crazy socks to school.

Don’t share obvious details

The detail about the community is not the most important part of your response, even if the prompt does say to “describe a community to which you belong.” Consider only sharing those details about the community that ties into what you are trying to share about yourself. For example, most drama groups put on performances for the public.

But not all drama groups are community-based and have participants ranging in age from 9 to 99. If part of your story is about this multi-generational community, then this detail plays a part in your story. Include those details that play a role in why the community is important or impactful for you.

Remember these things about the community essay for the Common App

No matter which community you choose to write about, you want to be sure that you reflect deeply about why this community is important to you. If you have a longer word count, you can consider using an anecdote to share with the reader, but for the shorter prompts, keep your writing personal, but just more to the point.

And don’t lose sight of the reason that you are writing this essay. You are applying to be a part of a new community. You want to show that you have a deep appreciation for the sense of satisfaction, dedication, and attachment that comes with being a member of a community. The purpose is to demonstrate that you know how to nurture the community and how you nourish others’ sense of belonging in that circle.

Colleges want to know that you will keep the flame of that college community alive, even as you graduate and move on with your life. The admissions office wants to know that you will cherish and contribute to the community that they already call their own. Convince them that you deserve to belong.

Archive by Date

Recent posts.

- Choose a College After Being Accepted

- Navigating the U.S. College Application Process as an International Student in 2024

- Class Size & Student to Faculty Ratios: What Research Says?

- How Long Should a College Admissions Essay Be?

- The Perfect College Essay: Focus On You

Join our Facebook Group ›› Stay informed about college admissions trends and ask questions of experts who can give you Great College Advice.

Private Prep

Test Prep, Tutoring, College Admissions

How to Write the “Community” Essay

A step-by-step guide to this popular supplemental prompt.

When college admissions officers admit a new group of freshmen, they aren’t just filling up classrooms — they’re also crafting (you guessed it) a campus community. College students don’t just sit quietly in class, retreat to their rooms to crank out homework, go to sleep, rinse, and repeat. They socialize! They join clubs! They organize student protests! They hold cultural events! They become RAs and audition for a cappella groups and get on-campus jobs! Colleges want to cultivate a thriving, vibrant, uplifting campus community that enriches students’ learning — and for that reason, they’re understandably curious about what kind of community member they’ll be getting when they invite you to campus as part of their incoming class.

Enter the “community” essay — an increasingly popular supplemental essay prompt that asks students to talk about a community to which they belong and how they have contributed to or benefited from that community. Community essays often sound something like this:

University of Michigan: Everyone belongs to many different communities and/or groups defined by (among other things) shared geography, religion, ethnicity, income, cuisine, interest, race, ideology, or intellectual heritage. Choose one of the communities to which you belong, and describe that community and your place within it. (250 words)

Pomona College: Reflecting on a community that you are part of, what values or perspectives from that community would you bring to Pomona? (250 words)

University of Rochester: Spiders are essential to the ecosystem. How are you essential to your community or will you be essential in your university community? (350-650 words)

Swarthmore: Swarthmore students’ worldviews are often forged by their prior experiences and exposure to ideas and values. Our students are often mentored, supported, and developed by their immediate context—in their neighborhoods, communities of faith, families, and classrooms. Reflect on what elements of your home, school, or community have shaped you or positively impacted you. How have you grown or changed because of the influence of your community? (250 words)

Yale: Reflect on a time when you have worked to enhance a community to which you feel connected. Why have these efforts been meaningful to you? You may define community however you like. (400 words)

Step 1: Pick a community to write about

Breathe. You belong to LOTS of communities. And if none immediately come to mind, it’s only because you need to bust open your idea of what constitutes a “community”!

Among other things, communities can be joined by…

- West Coasters

- NYC’s Koreatown

- Everyone in my cabin at summer camp

- ACLU volunteers

- Cast of a school musical

- Puzzle-lovers

- Powerlifters

- Army brats who live together on a military base

- Iranian-American

- Queer-identifying

- Children of pastors

Take 15 minutes to write down a list of ALL the communities you belong to that you can think of. While you’re writing, don’t worry about judging which ones will be useful for an essay. Just write down every community that comes to mind — even if some of them feel like a stretch.

When you’re done, survey your list of communities. Do one, two, or three communities jump out as options that could enable you to write about yourself and your community engagement? Carry your top choices of community into Step 2.

Step 2: Generate content.

For each of your top communities, answer any of the following questions that apply:

- Is there a memorable story I can tell about my engagement with this community?

- What concrete impacts have I had on this community?

- What problems have I solved (or attempted to solve) in this community?

- What have I learned from this community?

- How has this community supported me or enriched my life up to this point?

- How have I applied the lessons or values I gleaned from this community more broadly?

Different questions will be relevant for different community prompts. For example, if you’re working on answering Yale’s prompt, you’ll want to focus on a community on which you’ve had a concrete impact. But if you’re trying to crack Swarthmore’s community essay, you can prioritize communities that have impacted YOU. Keep in mind though — even for a prompt like Yale’s, which focuses on tangible impact, it’s important that your community essay doesn’t read like a rattled-off list of achievements in your community. Your goal here is to show that you are a generous, thoughtful, grateful, and active community member who uplifts the people around you — not to detail a list of the competitions that Math club has won under your leadership.

BONUS: Connect your past community life to your future on-campus community life.

Some community essay prompts ask you — or give you the option — to talk about how you plan on engaging with community on a particular college campus. If you’re tackling one of those prompts (like Pomona’s), then you guessed it: it’s research time!

Often, for these kinds of community prompts, it will serve you to first write about a community that you’ve engaged with in the past and then write about how you plan to continue engaging with that same kind of community at college. For example, if you wrote about throwing a Lunar New Year party with international students at your high school, you might write about how excited you are to join the International Students Alliance at your new college or contribute to the cross-cultural student magazine. Or, if you wrote about playing in your high school band, you might write about how you can’t wait to audition for your new college’s chamber orchestra or accompany the improv team for their improvised musicals. The point is to give your admissions officer an idea of what on-campus communities you might be interested in joining if you were to attend their particular school.

Check out our full College Essay Hub for tons of resources and guidance on writing your college essays. Need more personalized guidance on brainstorming or crafting your supplemental essays? Contact our college admissions team.

Caroline Hertz

The Community Essay

“Duke University seeks a talented, engaged student body that embodies the wide range of human experience; we believe that the diversity of our students makes our community stronger. If you’d like to share a perspective you bring or experiences you’ve had to help us understand you better—perhaps related to a community you belong to, your sexual orientation or gender identity, or your family or cultural background—we encourage you to do so. Real people are reading your application, and we want to do our best to understand and appreciate the real people applying to Duke.”

As with every essay you ship off to admissions – think about something you want admissions to know that hasn’t been represented. What can you expand upon to show your versatility, passion and ability to connect with the world around you?

About CEA HQ

View all posts by CEA HQ »

Written by CEA HQ

Category: Admissions , College Admissions , Essay Tips , Essay Writing , Supplemental Essays

Tags: admissions essay , admissions help , application , application supplement , applications , brainstorming , college admissions , college admissions essay , college application , college application help , college applications , college essay , common application , supplemental essays

Want free stuff?

We thought so. Sign up for free instructional videos, guides, worksheets and more!

One-On-One Advising

Common App Essay Prompt Guide

Supplemental Essay Prompt Guide

- YouTube Tutorials

- Our Approach & Team

- Undergraduate Testimonials

- Postgraduate Testimonials

- Where Our Students Get In

- CEA Gives Back

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Private School Admissions

- International Student Admissions

- Common App Essay Guide

- Supplemental Essay Guides

- Coalition App Guide

- The CEA Podcast

- Admissions Stats

- Notification Trackers

- Deadline Databases

- College Essay Examples

- Academy and Worksheets

- Waitlist Guides

- Get Started

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to write a great community service essay.

College Admissions , Extracurriculars

Are you applying to a college or a scholarship that requires a community service essay? Do you know how to write an essay that will impress readers and clearly show the impact your work had on yourself and others?

Read on to learn step-by-step instructions for writing a great community service essay that will help you stand out and be memorable.

What Is a Community Service Essay? Why Do You Need One?

A community service essay is an essay that describes the volunteer work you did and the impact it had on you and your community. Community service essays can vary widely depending on specific requirements listed in the application, but, in general, they describe the work you did, why you found the work important, and how it benefited people around you.

Community service essays are typically needed for two reasons:

#1: To Apply to College

- Some colleges require students to write community service essays as part of their application or to be eligible for certain scholarships.

- You may also choose to highlight your community service work in your personal statement.

#2: To Apply for Scholarships

- Some scholarships are specifically awarded to students with exceptional community service experiences, and many use community service essays to help choose scholarship recipients.

- Green Mountain College offers one of the most famous of these scholarships. Their "Make a Difference Scholarship" offers full tuition, room, and board to students who have demonstrated a significant, positive impact through their community service

Getting Started With Your Essay

In the following sections, I'll go over each step of how to plan and write your essay. I'll also include sample excerpts for you to look through so you can get a better idea of what readers are looking for when they review your essay.

Step 1: Know the Essay Requirements

Before your start writing a single word, you should be familiar with the essay prompt. Each college or scholarship will have different requirements for their essay, so make sure you read these carefully and understand them.

Specific things to pay attention to include:

- Length requirement

- Application deadline

- The main purpose or focus of the essay

- If the essay should follow a specific structure

Below are three real community service essay prompts. Read through them and notice how much they vary in terms of length, detail, and what information the writer should include.

From the Equitable Excellence Scholarship:

"Describe your outstanding achievement in depth and provide the specific planning, training, goals, and steps taken to make the accomplishment successful. Include details about your role and highlight leadership you provided. Your essay must be a minimum of 350 words but not more than 600 words."

From the Laura W. Bush Traveling Scholarship:

"Essay (up to 500 words, double spaced) explaining your interest in being considered for the award and how your proposed project reflects or is related to both UNESCO's mandate and U.S. interests in promoting peace by sharing advances in education, science, culture, and communications."

From the LULAC National Scholarship Fund:

"Please type or print an essay of 300 words (maximum) on how your academic studies will contribute to your personal & professional goals. In addition, please discuss any community service or extracurricular activities you have been involved in that relate to your goals."

Step 2: Brainstorm Ideas

Even after you understand what the essay should be about, it can still be difficult to begin writing. Answer the following questions to help brainstorm essay ideas. You may be able to incorporate your answers into your essay.

- What community service activity that you've participated in has meant the most to you?

- What is your favorite memory from performing community service?

- Why did you decide to begin community service?

- What made you decide to volunteer where you did?

- How has your community service changed you?

- How has your community service helped others?

- How has your community service affected your plans for the future?

You don't need to answer all the questions, but if you find you have a lot of ideas for one of two of them, those may be things you want to include in your essay.

Writing Your Essay

How you structure your essay will depend on the requirements of the scholarship or school you are applying to. You may give an overview of all the work you did as a volunteer, or highlight a particularly memorable experience. You may focus on your personal growth or how your community benefited.

Regardless of the specific structure requested, follow the guidelines below to make sure your community service essay is memorable and clearly shows the impact of your work.

Samples of mediocre and excellent essays are included below to give you a better idea of how you should draft your own essay.

Step 1: Hook Your Reader In

You want the person reading your essay to be interested, so your first sentence should hook them in and entice them to read more. A good way to do this is to start in the middle of the action. Your first sentence could describe you helping build a house, releasing a rescued animal back to the wild, watching a student you tutored read a book on their own, or something else that quickly gets the reader interested. This will help set your essay apart and make it more memorable.

Compare these two opening sentences:

"I have volunteered at the Wishbone Pet Shelter for three years."

"The moment I saw the starving, mud-splattered puppy brought into the shelter with its tail between its legs, I knew I'd do whatever I could to save it."

The first sentence is a very general, bland statement. The majority of community service essays probably begin a lot like it, but it gives the reader little information and does nothing to draw them in. On the other hand, the second sentence begins immediately with action and helps persuade the reader to keep reading so they can learn what happened to the dog.

Step 2: Discuss the Work You Did

Once you've hooked your reader in with your first sentence, tell them about your community service experiences. State where you work, when you began working, how much time you've spent there, and what your main duties include. This will help the reader quickly put the rest of the essay in context and understand the basics of your community service work.

Not including basic details about your community service could leave your reader confused.

Step 3: Include Specific Details

It's the details of your community service that make your experience unique and memorable, so go into the specifics of what you did.

For example, don't just say you volunteered at a nursing home; talk about reading Mrs. Johnson her favorite book, watching Mr. Scott win at bingo, and seeing the residents play games with their grandchildren at the family day you organized. Try to include specific activities, moments, and people in your essay. Having details like these let the readers really understand what work you did and how it differs from other volunteer experiences.

Compare these two passages:

"For my volunteer work, I tutored children at a local elementary school. I helped them improve their math skills and become more confident students."

"As a volunteer at York Elementary School, I worked one-on-one with second and third graders who struggled with their math skills, particularly addition, subtraction, and fractions. As part of my work, I would create practice problems and quizzes and try to connect math to the students' interests. One of my favorite memories was when Sara, a student I had been working with for several weeks, told me that she enjoyed the math problems I had created about a girl buying and selling horses so much that she asked to help me create math problems for other students."

The first passage only gives basic information about the work done by the volunteer; there is very little detail included, and no evidence is given to support her claims. How did she help students improve their math skills? How did she know they were becoming more confident?

The second passage is much more detailed. It recounts a specific story and explains more fully what kind of work the volunteer did, as well as a specific instance of a student becoming more confident with her math skills. Providing more detail in your essay helps support your claims as well as make your essay more memorable and unique.

Step 4: Show Your Personality

It would be very hard to get a scholarship or place at a school if none of your readers felt like they knew much about you after finishing your essay, so make sure that your essay shows your personality. The way to do this is to state your personal strengths, then provide examples to support your claims. Take some time to think about which parts of your personality you would like your essay to highlight, then write about specific examples to show this.

- If you want to show that you're a motivated leader, describe a time when you organized an event or supervised other volunteers.

- If you want to show your teamwork skills, write about a time you helped a group of people work together better.

- If you want to show that you're a compassionate animal lover, write about taking care of neglected shelter animals and helping each of them find homes.

Step 5: State What You Accomplished

After you have described your community service and given specific examples of your work, you want to begin to wrap your essay up by stating your accomplishments. What was the impact of your community service? Did you build a house for a family to move into? Help students improve their reading skills? Clean up a local park? Make sure the impact of your work is clear; don't be worried about bragging here.

If you can include specific numbers, that will also strengthen your essay. Saying "I delivered meals to 24 home-bound senior citizens" is a stronger example than just saying "I delivered meals to lots of senior citizens."

Also be sure to explain why your work matters. Why is what you did important? Did it provide more parks for kids to play in? Help students get better grades? Give people medical care who would otherwise not have gotten it? This is an important part of your essay, so make sure to go into enough detail that your readers will know exactly what you accomplished and how it helped your community.

"My biggest accomplishment during my community service was helping to organize a family event at the retirement home. The children and grandchildren of many residents attended, and they all enjoyed playing games and watching movies together."

"The community service accomplishment that I'm most proud of is the work I did to help organize the First Annual Family Fun Day at the retirement home. My job was to design and organize fun activities that senior citizens and their younger relatives could enjoy. The event lasted eight hours and included ten different games, two performances, and a movie screening with popcorn. Almost 200 residents and family members attended throughout the day. This event was important because it provided an opportunity for senior citizens to connect with their family members in a way they aren't often able to. It also made the retirement home seem more fun and enjoyable to children, and we have seen an increase in the number of kids coming to visit their grandparents since the event."

The second passage is stronger for a variety of reasons. First, it goes into much more detail about the work the volunteer did. The first passage only states that she helped "organize a family event." That really doesn't tell readers much about her work or what her responsibilities were. The second passage is much clearer; her job was to "design and organize fun activities."

The second passage also explains the event in more depth. A family day can be many things; remember that your readers are likely not familiar with what you're talking about, so details help them get a clearer picture.

Lastly, the second passage makes the importance of the event clear: it helped residents connect with younger family members, and it helped retirement homes seem less intimidating to children, so now some residents see their grand kids more often.

Step 6: Discuss What You Learned

One of the final things to include in your essay should be the impact that your community service had on you. You can discuss skills you learned, such as carpentry, public speaking, animal care, or another skill.

You can also talk about how you changed personally. Are you more patient now? More understanding of others? Do you have a better idea of the type of career you want? Go into depth about this, but be honest. Don't say your community service changed your life if it didn't because trite statements won't impress readers.

In order to support your statements, provide more examples. If you say you're more patient now, how do you know this? Do you get less frustrated while playing with your younger siblings? Are you more willing to help group partners who are struggling with their part of the work? You've probably noticed by now that including specific examples and details is one of the best ways to create a strong and believable essay .

"As a result of my community service, I learned a lot about building houses and became a more mature person."

"As a result of my community service, I gained hands-on experience in construction. I learned how to read blueprints, use a hammer and nails, and begin constructing the foundation of a two-bedroom house. Working on the house could be challenging at times, but it taught me to appreciate the value of hard work and be more willing to pitch in when I see someone needs help. My dad has just started building a shed in our backyard, and I offered to help him with it because I know from my community service how much work it is. I also appreciate my own house more, and I know how lucky I am to have a roof over my head."

The second passage is more impressive and memorable because it describes the skills the writer learned in more detail and recounts a specific story that supports her claim that her community service changed her and made her more helpful.

Step 7: Finish Strong

Just as you started your essay in a way that would grab readers' attention, you want to finish your essay on a strong note as well. A good way to end your essay is to state again the impact your work had on you, your community, or both. Reiterate how you changed as a result of your community service, why you found the work important, or how it helped others.

Compare these two concluding statements:

"In conclusion, I learned a lot from my community service at my local museum, and I hope to keep volunteering and learning more about history."