Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Got milk? Does it give you problems?

Cancer risk, wine preference, and your genes

Excited about new diet drug? This procedure seems better choice.

Illustration by Tang Yau Hoong

How death shapes life

As global COVID toll hits 5 million, Harvard philosopher ponders the intimate, universal experience of knowing the end will come but not knowing when

Colleen Walsh

Harvard Staff Writer

Does the understanding that our final breath could come tomorrow affect the way we choose to live? And how do we make sense of a life cut short by a random accident, or a collective existence in which the loss of 5 million lives to a pandemic often seems eclipsed by other headlines? For answers, the Gazette turned to Susanna Siegel, Harvard’s Edgar Pierce Professor of Philosophy. Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Susanna Siegel

GAZETTE: How do we get through the day with death all around us?

SIEGEL: This question arises because we can be made to feel uneasy, distracted, or derailed by death in any form: mass death, or the prospect of our own; deaths of people unknown to us that we only hear or read about; or deaths of people who tear the fabric of our lives when they go. Both in politics and in everyday life, one of the worst things we could do is get used to death, treat it as unremarkable or as anything other than a loss. This fact has profound consequences for every facet of life: politics and governance, interpersonal relationships, and all forms of human consciousness.

When things go well, death stays in the background, and from there, covertly, it shapes our awareness of everything else. Even when we get through the day with ease, the prospect of death is still in some way all around us.

GAZETTE: Can philosophy help illuminate how death impacts consciousness?

SIEGEL: The philosophers Soren Kierkegaard and Martin Heidegger each discuss death, in their own ways, as a horizon that implicitly shapes our consciousness. It’s what gives future times the pressure they exert on us. A horizon is the kind of thing that is normally in the background — something that limits, partly defines, and sets the stage for what you focus on. These two philosophers help us see the ways that death occupies the background of consciousness — and that the background is where it belongs.

“Both in politics and in everyday life, one of the worst things we could do is get used to death, treat it as unremarkable or as anything other than a loss,” says Susanna Siegel, Harvard’s Edgar Pierce Professor of Philosophy.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

These philosophical insights are vivid in Rainer Marie Rilke’s short and stunning poem “Der Tod” (“Death”). As Burton Pike translates it from German, the poem begins: “There stands death, a bluish concoction/in a cup without a saucer.” This opening gets me every time. Death is standing. It’s standing in the way liquid stands still in a container. Sometimes cooking instructions tell you to boil a mixture and then let it stand, while you complete another part of the recipe. That’s the way death is in the poem: standing, waiting for you to get farther along with whatever you are doing. It will be there while you’re working, it will be there when you’re done, and in some way, it is a background part of those other tasks.

A few lines later, it’s suggested in the poem that someone long ago, “at a distant breakfast,” saw a dusty, cracked cup — that cup with the bluish concoction standing in it — and this person read the word “hope” written in faded letters on the side of mug. Hope is a future-directed feeling, and in the poem, the word is written on a surface that contains death underneath. As it stands, death shapes the horizon of life.

GAZETTE: What are the ethical consequences of these philosophical views?

SIEGEL: We’re familiar with the ways that making the prospect of death salient can unnerve, paralyze, or derail a person. An extreme example is shown by people with Cotard syndrome , who report feeling that they have already died. It is considered a “monothematic” delusion, because this odd reaction is circumscribed by the sufferers’ other beliefs. They freely acknowledge how strange it is to be both dead and yet still there to report on it. They are typically deeply depressed, burdened with a feeling that all possibilities of action have simply been shut down, closed off, made unavailable. Robbed of a feeling of futurity, seemingly without affordances for action, it feels natural to people in this state to describe it as the state of being already dead.

Cotard syndrome is an extreme case that illustrates how bringing death into the foreground of consciousness can feel utterly disempowering. This observation has political consequences, which are evident in a culture that treats any kind of lethal violence as something we have to expect and plan for. A glaring example would be gun violence, with its lockdown drills for children, its steady stream of the same types of events, over and over — as if these deaths could only be met with a shrug and a sigh, because they are simply part of the cost of other people exercising their freedom.

It isn’t just depressing to bring death into the foreground of consciousness by creating an atmosphere of violence — it’s also dangerous. Any political arrangement that lets masses of people die thematizes death, by making lethal violence perceptible, frequent, salient, talked-about, and tolerated. Raising death to salience in this way can create and then leverage feelings of existential precarity, which in turn emotionally equip people on a mass, nationwide scale to tolerate violence as a tool to gain political power. It’s now a regular occurrence to ram into protestors with vehicles, intimidate voters and poll workers, and prepare to attack government buildings and the people inside. This atmosphere disparages life, and then promises violence as defense against such cheapening, and a means of control.

GAZETTE: When we read about an accidental death in the newspaper, it can be truly unnerving, even though the victim is a stranger. And we’ve been hearing about a steady stream of deaths from COVID-19 for almost two years, to the point where the death count is just part of the daily news. Why is the process of thinking about these losses important?

SIEGEL: It might not seem directly related to politics, but when you react to a life cut short by thinking, “If this terrible thing could happen to them, then it could happen to me,” that reaction is a basic form of civic regard. It’s fragile, and highly sensitive to how deaths are reported and rendered in public. The passing moment of concern may seem insignificant, but it gets supplanted by something much worse when deaths are rendered in ways likely to prompt such questions as “What did they do to get in trouble?” or such suspicions as “They probably had it coming,” or such callous resignations as “They were going to die anyway.” We have seen some of those reactions during the pandemic. They are refusals to recognize the terribleness of death.

Deaths can seem even more haunting when they’re not recognized as a real loss, which is why it’s so important how deaths are depicted by governments and in mass communication. The genre of the obituary is there to present deaths as a loss to the public. The movement for Black lives brought into focus for everyone what many people knew and felt all along, which was that when deaths are not rendered as losses to the public, then they are depicted in a way that erodes civic regard.

When anyone dies from COVID, our political representatives should acknowledge it in a way that does justice to the gravity of that death. Recognizing COVID deaths as a public emergency belongs to the kind of governance that aims to keep the blue concoction where it belongs.

Share this article

You might like.

Biomolecular archaeologist looks at why most of world’s population has trouble digesting beverage that helped shape civilization

Biologist separates reality of science from the claims of profiling firms

Study finds minimally invasive treatment more cost-effective over time, brings greater weight loss

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

How far has COVID set back students?

An economist, a policy expert, and a teacher explain why learning losses are worse than many parents realize

Open Yale Courses

You are here.

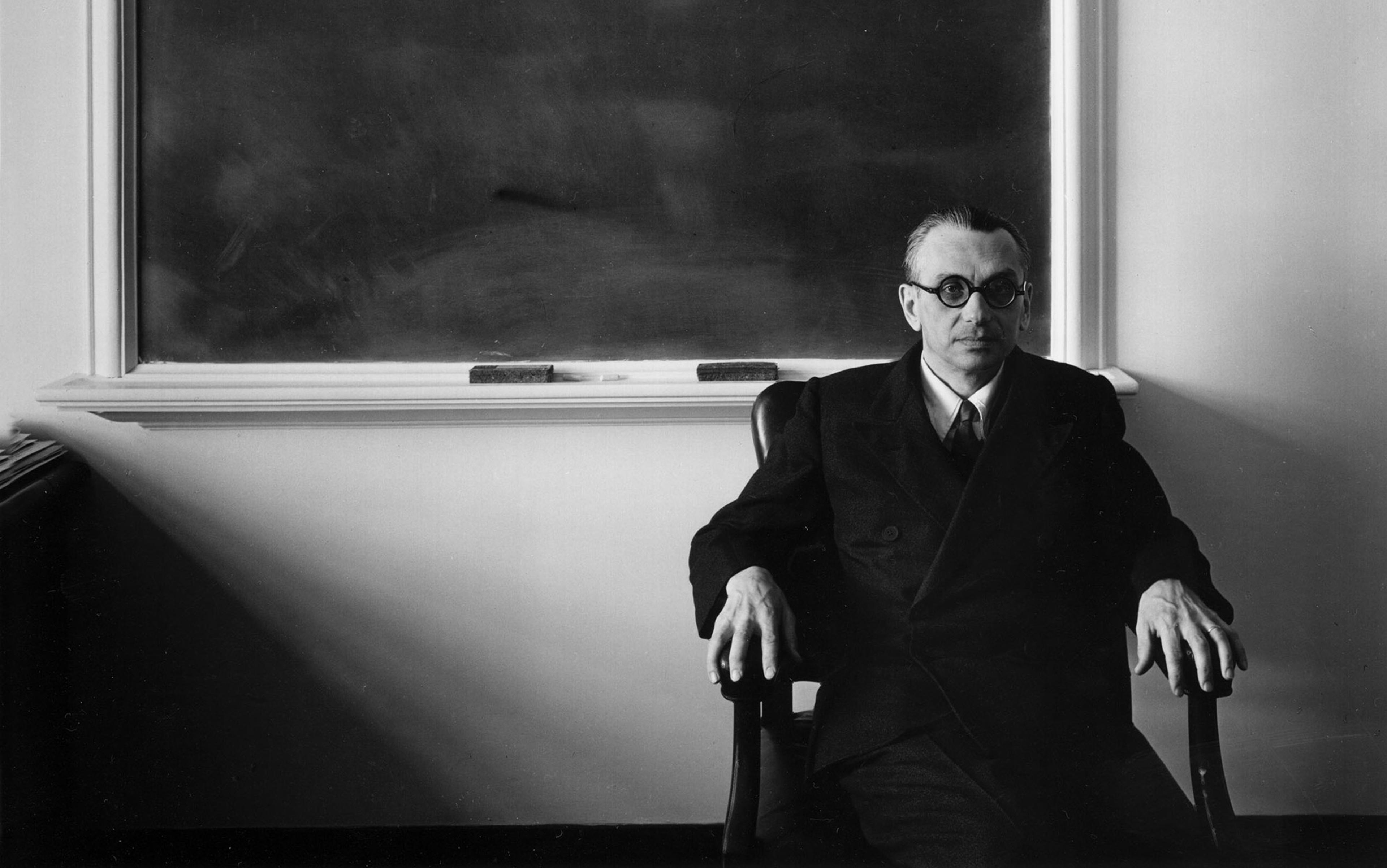

There is one thing I can be sure of: I am going to die. But what am I to make of that fact? This course will examine a number of issues that arise once we begin to reflect on our mortality. The possibility that death may not actually be the end is considered. Are we, in some sense, immortal? Would immortality be desirable? Also a clearer notion of what it is to die is examined. What does it mean to say that a person has died? What kind of fact is that? And, finally, different attitudes to death are evaluated. Is death an evil? How? Why? Is suicide morally permissible? Is it rational? How should the knowledge that I am going to die affect the way I live my life?

This Yale College course, taught on campus twice per week for 50 minutes, was recorded for Open Yale Courses in Spring 2007.

The Open Yale Courses Series

For more information about Professor Kagan’s book Death , click here .

Plato, Phaedo John Perry, A Dialogue on Personal Identity and Immortality Leo Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilych

Course Packet: Barnes, Julian. “The Dream.” In History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters .

Brandt, Richard. “The Morality and Rationality of Suicide.” In Moral Problems . Edited by James Rachels. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Edwards, Paul. “Existentialism and Death: A Survey of Some Confusions and Absurdities.” In Philosophy, Science and Method: Essays in Honor of Ernest Nagel . Edited by Sidney Morgenbesser, Patrick Suppes and Morton White. New York: St. Matrin’s Press, 1969. pp. 473-505

Feldman, Fred. “The Enigma of Death.” In Confrontations with the Reaper: A Philosophical Study of Nature and Value of Death . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 56-71

Hume, David. “On Suicide.” In Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary .

Kaufmann, Walter. “Death.” In The Faith of a Heretic . New York: New American Library, 1959. pp. 353-376

Kaufmann, Walter. “Death Without Dread.” In Existentialism, Religion, and Death: Thirteen Essays . New York: New American Library, 1976. pp. 224-248

Martin, Robert. “The Identity of Animal and People.” In There are Two Errors in the the Title of This Book: A Sourcebook of Philosophical Puzzles, Problems, and Paradoxes . Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2002. pp. 223-226

Montaigne, Michel de. “That to Philosophize is to Learn to Die.” In The Complete Essays .

Nagel, Thomas. “Death.” In Mortal Questions . New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979. pp. 1-10

Rosenberg, Jay. “Life After Death: In Search of the Question.” In Thinking Clearly About Death . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1983. pp. 18-22

Schick, Theodore and Lewis Vaughn. “Near-Death Experiences.” In How to Think About Weird Things . New York: McGraw Hill, 2005. pp 307-323

Swift, Jonathan. Gulliver’s Travels , Part III, chapter 10.

Williams, Bernard. “The Makropulos Case: Reflections on the Tedium of Immortality.” In Language, Metaphysics, and Death . Edited by John Donnelly. New York: Fordham University Press, 1978. pp. 229-242

All students must attend discussion sections. Participation can help raise one’s grade, but can never hurt. However, poor attendance or non-participation will lower one’s grade.

There will be three short papers. Each should be 5 pages, double-spaced. All papers are worth equally. If papers show improvements over the term, however, the later work will be counted even more heavily.

There will be no final exam.

Discussion section attendance and participation: 25% Three short papers: 25% each (total: 75%)

This Open Yale Course is accompanied by a book published by Yale University Press.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

What the Stoics Understood About Death (And Can Teach Us)

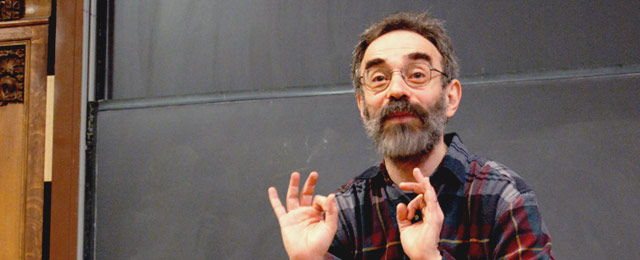

David fideler on what awareness of mortality does to a life.

“Wherever I turn, I see signs of my old age,” Seneca wrote to Lucilius. Seneca had just arrived at his villa outside of Rome, where he was having a conversation with his property manager about the high cost of maintaining the disintegrating old building. But Seneca then explained, “My estate manager told me it was not his fault: he was doing everything possible, but the country home was old. And this villa was built under my supervision! What will my future look like if stonework of my own age is already crumbling?”

At that time, Seneca was in his late sixties, and he was starting to feel the aches and pains of old age. But he also found old age to be pleasurable. However, the older you get, the more challenging things become. Extreme old age, he said, is like a lasting illness you never recover from; and when the body really declines, it’s like a ship that starts springing leaks, one after another.

Where I currently live, in Sarajevo, I see extremely old people, who are quite close to death, on an almost daily basis. It seems that some of my neighbors—thin, frail, and bent over, often walking with a cane at a snail’s pace over the old stone streets—could drop over and expire at any moment. That said, seeing extremely elderly people out and about is an inspiring and heartfelt experience for me. First of all, it’s lovely to see people who have lived for so long, often against challenging odds, and it’s impossible to see them without feeling a great sense of tenderness for them. Second, they are a timely reminder of my own mortality. It’s also very different from what I remember seeing in the United States.

Unlike many other countries, the United States has accomplished a world-class disappearing act when it comes to keeping older adults (and any other reminders of death) out of sight and out of mind. With its shiny glass and steel buildings, shopping malls, and spread-out suburbs, the American landscape has been sterilized and artificially “cleaned up” in such a way that extremely old people are rarely seen on public display. But here in a historic European city with ancient stone buildings that go back centuries, and well-established neighborhoods with cobblestone streets, extremely old people, hobbling along, are a happy part of daily life. They remind me that life is not without extreme struggle. And when people die, which can happen at any age, the local religious communities post death notices, with photos of the deceased, in local neighborhoods all over town. It’s another nice custom that reminds us of being mortal.

A Stoic wants to live well—and living well means dying well, too. A Stoic lives well through having a good character, and death is the final test of it. While every death will be a bit different, the Roman Stoics believed that a good death would be characterized by mental tranquility, a lack of complaining, and gratitude for the life we’ve been given. In other words, as the final act of living, a good death is characterized by acceptance and gratitude. Also, having a real philosophy of life, and having worked on developing a sound character, allows a person to die without any feelings of regret.

Seneca frequently thought and wrote about death. Some of this must have been due to his poor health. Because he suffered from tuberculosis and asthma from a young age, he must have sensed the certainty and nearness of his own death throughout his entire life. In Letter 54 he describes, in graphic detail, a recent asthma attack that nearly killed him. But much earlier, probably in his twenties, he was so sick, and so near death, that he thought about ending his own life, to finally stop the suffering. He didn’t follow through on that, fortunately, out of love for his father. As he writes,

I often felt the urge to end my life, but the old age of my dear father held me back. For while I thought that I could die bravely, I knew he could not bear the loss bravely. And so I commanded myself to live. Sometimes it’s an act of courage just to keep living.

For a Stoic (and for other ancient philosophers, too), memento mori —contemplating our inevitable death—was an essential philosophical exercise, and one that comes with unexpected benefits. As an anticipation of future adversity, memento mori allows us to prepare for death, and helps remove our fears of death. It also encourages us to take our current lives more seriously, because we realize they’re limited. As I’ve discovered in a practical sense, reflecting on my own death—and the inevitable death of those dear to me—has had a totally unexpected and powerful benefit: feeling a more profound sense of gratitude for the time we still have together.

The Latin phrase memento mori literally means “remember that you have to die.” Over the centuries, scholars often would keep a symbolic memento mori image in their study, like a skull, as a reminder of their own mortality.

In the world of philosophy, the model of someone dying well, without an ounce of fear, was Socrates. Imprisoned on trumped-up charges for corrupting the youth of Athens, Socrates was detained for thirty days before facing his death sentence of drinking hemlock poison. At the time of his death in 399 BC, Socrates was around seventy years old. If he had wished, he could have very easily escaped prison, with his friends’ help, and then set up life elsewhere in Greece. But it would have gone against everything he believed in. Also, escaping would have permanently damaged his reputation. Since one of Socrates’s main goals was to improve society, that implied he should follow society’s laws, even if he had been treated unjustly.

This allowed Socrates thirty final days to meet with his friends and his students to continue their philosophical discussions. He had challenged the morality of those who called for his death with a very memorable line: “If you kill me,” he said, “you will not harm me so much as yourselves.” This thought was much appreciated by the later Stoics, since, in their view, nothing can harm the character of a wise person. During his last meeting with his students, right before his death, Socrates discussed and questioned the possibility of an afterlife. He also said, memorably, that “philosophy is a preparation for death,” which was probably the real beginning of the memento mori tradition (at least for philosophers). When his final conversation was complete, Socrates drank the hemlock, and he peacefully passed away, surrounded by his students.

According to Seneca, the philosopher Epicurus said, “Rehearse for death,” which is a practice Seneca himself greatly encouraged. For Seneca and the other Roman Stoics, death was “the master fear,” and once someone learns how to overcome it, little else remains fearful either.

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus told his students that when you kiss your child goodnight, you should remind yourself that your child could die tomorrow. While it is literally true that your child could die tomorrow, many modern readers recoil at the idea of even contemplating such a thought. However, that might be a measure of their reluctance to accept the inevitability of death, or a way of repressing the fact that death can arrive unexpectedly, at any moment. As someone who personally uses this practice, I can tell you that it’s perfectly harmless, once you get past any initial discomfort. The huge benefit it brings is the greater sense of gratitude you experience with your loved ones. When you perform this practice, you consciously realize that someday, which nobody can predict, will be your last time together—so you experience much greater gratitude for the time you spend together now. As Seneca wisely recommended, let us greedily enjoy our friends and our loved ones now, while we still have them.

What is it like emotionally to contemplate your own death or the death of a close family member? I’ve been experimenting with this for some time now and can report only positive results. That’s because, when I think of the mortality of a loved one and the fact that all of our time together is by definition limited, it improves the quality of my life. It makes me feel a much deeper sense of appreciation for all the time we are together. If you don’t remember that your time is limited and finite, you are much more likely to take things for granted.

I most often remember death when I’m with my son, Benjamin, seven and a half as I write. That’s a delightful age because he’s very playful and now capable of having fun conversations. We’re also starting to talk about philosophical things.

Of course, it’s impossible for most children of his age to grasp the gravity or finality of death, because most of them have never had any firsthand experience of losing a loved one. Children live in a kind of psychological Golden Age, in which all their needs seem magically provided for. Since they live in a protected sphere, most haven’t yet been exposed to the more challenging aspects of life.

Because of that, I’ve been trying to teach Benjamin a little bit about death and the fact that daddy, mommy, and he will someday die. This effort is a bit of basic Stoic training for a kid, and I’m curious if it might be possible to increase his appreciation for the limited time we have together, even at such a young age? At the very least, I hope it will greatly reduce the level of shock he experiences when someone close to him does die, because he’ll be expecting it.

The other day, we were driving home after feasting on some fast food, and Benjamin spoke to me about God for the first time in his life. With a boyish sense of delight, he explained to me, “God has some amazing powers, like being able to see and hear everything. But his greatest superpower is that he’s invisible!”

I chuckled at his use of the word “superpower,” which made God sound like a superhero, just like Spider-Man! But laughter aside, he had opened up the doorway to speak about some profound issues, so I brought up the topic of death.

“Benjamin,” I asked, “do you know that, someday, mommy, daddy, and you are going to die?”

“Yes,” he replied.

“I’m almost sixty,” I explained, “so I could live another twenty years.”

“I don’t think you’ll live quite that long,” he said. “But maybe something like that.” (Thank you, Benjamin! We’ll just have to see how things go.)

Then I asked, “Did you know that you could die at any time?”

He said, “I don’t think I’ll die anytime soon.”

“But,” I replied, “you could. This is not something in our control. You are young, so you could live for a very long time. But since we’re driving in a car, we could be in a car crash five minutes from now, and we could both be killed instantly. So even if you’re very, very young, you can die at any time. If you stay healthy, the chances that you’ll live a long life go up. But in the end, when we die is not under our control.”

Benjamin nodded and seemed to understand. And fortunately, we arrived home safely a few minutes later.

__________________________________

From Breakfast with Seneca: A Stoic Guide to the Art of Living by David Fideler, published by W. W. Norton.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

David Fideler

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

“Phone Book”

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

A hunter’s lyrical reflection on the humbling business of being mortal

Thinkers and theories

We’ll meet again

The intrepid logician Kurt Gödel believed in the afterlife. In four heartfelt letters to his mother he explained why

Alexander T Englert

The haunting of modern China

In Nanjing, Hong Kong and other Chinese cities, rapid urbanisation is multiplying a fear of death and belief in ghosts

Andrew Kipnis

Even in modern secular societies, belief in an afterlife persists. Why?

Meaning and the good life

The world turns vivid, strange and philosophical for one plane crash survivor

Toby ponders the inner lives of the sheep that roam atop his parents’ graves

Animals and humans

Goodbye Pixel

Although it felt more like bereavement for a person than the loss of a thing, the death of a pet isn’t exactly like either

Julian Baggini

Ageing and death

When his elderly parents make a suicide pact, Doron struggles to accept their choice

Rituals and celebrations

In a Mongolian wind burial, a body falls on land before getting swept up to the heavens

Values and beliefs

A funeral director takes in bodies that social stigma leaves unclaimed

How an end-of-life doula found her vocation as a companion for the dying

Is grandad on the moon?

We no longer have a clear sense of how to introduce our children to death. But their questions can help us face up to it

Pragya Agarwal

Final thoughts

Do deathbed regrets give us a special insight into what really matters in life? There are good reasons to be sceptical

Mood and emotion

Grieving Kobe Bryant, Conor wonders: why do untimely celebrity deaths hit so hard?

Sooner or later we all face death. Will a sense of meaning help us?

Warren Ward

Marcus Aurelius helped me survive grief and rebuild my life

Jamie Lombardi

This mortal coil

The fear of death drives many evils, from addiction to prejudice and war. Can it also be harnessed as a force for good?

Jeff Greenberg

Psychiatry and psychotherapy

It’s complicated – why some grief takes much longer to heal

Marie Lundorff

Death by design

We can choose how we live – why not how we leave? A free society should allow dying to be more deliberate and imaginative

Daniel Callcut

Thinking about one’s birth is as uncanny as thinking of death

Alison Stone

‘When it comes to the end, we all want the same things.’ Why animals need a good death

‘Where is it that we are?’ A poet conjures a journey along the waters of the afterlife

War and peace

What motivated three young Britons to join the deadly fight against ISIS in Syria?

The need for an ending

When a person goes missing, in war or in ordinary life, their story is cut off mid-sentence. A death can be easier to bear

Introduction: Death and Dying in Comparative Philosophical Perspective

- First Online: 03 September 2019

Cite this chapter

- Timothy D Knepper 18

Part of the book series: Comparative Philosophy of Religion ((COPR,volume 2))

723 Accesses

This introductory chapter previews the content and conclusions of The Comparison Project’s 2015–2017 programming cycle on death and dying. First, it explicates each of the 12 content essays on death and dying, especially with respect to the focus of the series—how traditional theologies of death and rituals of dying are affected by and respond to the medicalization of death. Then, it highlights the four, brief comparative conclusions to the series.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

For obvious reasons, we did not include here the four interfaith dialogues involving representatives of local religious communities, the performance of Tibetan Buddhist rituals related to death and dying, and the reading of non-fiction essays by cancer survivors. The supplemental essay by M. Allison Prude on “Death in Tibetan Buddhism” replaces the Tibetan Buddhist ritual performance with an academic analysis of theologies of death and rituals of dying in Tibetan Buddhism, while the supplemental essay by Mark Berkson on “Death in Ancient Chinese Thought” provides coverage of a lacuna in our series.

Our secular perspective, as reflected in the essay of Amy Hollywood, is in no way an attempt to develop a secular bioethics. Instead, it is an imaginative exploration of the role that “difficult literature” might play in the preparation for death of those who are no longer religious. For the attempt to develop formal, secular bioethics, see especially Engelhardt ( 1991 ).

Our understanding of the medicalization of death refers to the substitution of doctors, hospitals, and technology for family, home, and comfort during the process of dying. More fundamentally, it views death as a purely biological phenomenon rather than a cultural, emotional, and religious experience that is a natural part of human existence.

As Keown indicates, this view constitutes a reversal of the position that he espoused over 20 years ago in Buddhism and Bioethics , wherein he asserted that the concept of brain death would be acceptable to Buddhism.

Engelhardt, H. Tristram, Jr. 1991. Bioethics and secular humanism: The search for a common morality . Eugene: Wipf & Stock.

Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Philosophy and Religion, Drake University, Des Moines, IA, USA

Timothy D Knepper

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Timothy D Knepper .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Timothy D Knepper & Mary Gottschalk &

Religion Department, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Lucy Bregman

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Knepper, T.D. (2019). Introduction: Death and Dying in Comparative Philosophical Perspective. In: Knepper, T.D., Bregman, L., Gottschalk, M. (eds) Death and Dying. Comparative Philosophy of Religion, vol 2. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19300-3_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19300-3_1

Published : 03 September 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-19299-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-19300-3

eBook Packages : Religion and Philosophy Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Concept of Death in Philosophy and Experience

This essay examines three approaches to the concept of death: an existential approach by Heidegger, a pragmatic evaluation by Nagel, and an experiential account by Philip Gould, who was not a professional philosopher but who wrote a detailed description of the time before his death from cancer. I compare and contrast the different approaches, and use Gould's account as real-life check on the two philosophical analyses.

Related Papers

Steven Bindeman

The gist of this paper will be my exploration of the kinds of issues that emerge when existentially-grounded phenomenologists confront the issue of death. After briefly examining the materialist perspective on consciousness, we will concentrate our attention on how the recognition of different levels of consciousness can show us how we can relate to death in different ways. We will proceed from examining the impossibility of the death of the self, to the possibility of transcendence through experiencing the death of the other. We will turn to Merleau-Ponty’s concept of bodily knowledge for help with the matter of how consciousness constitutes the world around itself and enables the possibility of transcendence. We will also examine passages from Nietzsche’s philosophy (with guidance from Heidegger and Blanchot) that cover the transition from viewing time as linear to viewing time as circular, and the transition from understanding our place in the universe in a passive, accepting way...

Tomas Kačerauskas

Berkant Gültekin

Darius Samadian

An analysis of Heidegger's and Sartre's view of death. An argument that a serious acknowledgement of one's own death can lead to an ethics towards other people, and a sense of togetherness

Eduardo M Lape

This is a rough reflection to Heidegger's essay.

Heidegger, Authenticity and the Self

Taylor Carman

Maxine Sheets-Johnstone

This article considers the relationship of Heidegger’s metaphysics of Being-toward-death to what Heidegger describes as “the enigma of motion,” that is, to Dasein’s “historicality.” In doing so, the article confronts a series of questions concerning fundamental realities of animate life, realities centering on angst in the face of death, but including curiosity and fear, for example, all such realities being what Heidegger terms “states-of-mind” or “moods.” Thus, the article basically questions Heidegger’s elision of a Leibkörper, not only in terms of feelings but in terms of an exaltation of language, an insular notion of Dasein’s historicality, and a narrow and deficient depiction of animals in his “philosophical biology.” Through a critical examination of the phenomenological disclosure that Heidegger seeks in his metaphysics of Being-toward-death, the article shows that death and the very concept of death hinges on being a body, a temporally finite animate body. Thus, however metaphysical its exposition, Being-toward-death is existentially anchored in being a body. keywords: “enigma of motion,” concept of death, poetry, being “poor in world,” being poor in body, states-of-mind, feelings

Lennart Belfrage

THE EXPERIENCE OF DEATH and the Moral Problem of Suicide

Edouard d'Araille

Ground-breaking analysis of Death by the key Existentialist philosopher Paul-Louis Landsberg who died in a German concentration camp during the Second World War. A part of the group of philosophers embracing Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and Simone de Beauvoir, Paul-Louis Landsberg was published in the journal 'Les Temps Modernes' and released several works before his premature death at the hands of the Nazis. The present work 'The Experience of Death' is coupled with an equally forceful study of the 'Moral Problem of Suicide'. The portion of the work on death is perhaps the most perceptive and searching existentialist analysis of death apart from that of Martin Heidegger which features in his magnum opus 'Being and Time'. Landsberg was a Christian yet although he expresses some Christian views in his work he does not force any of his beliefs on his readers. In fact, as a Christian philosopher he is a controversial figure because of his liberal and forward-thinking views on suicide. This is a book that makes a deep impact upon anyone who dares to accompany the author on his honest explorations of Death and Suicide. - Brief biographical details and a bibliography are provided as well as full textual annotations and an Editor's Note as introduction. The volume is edited by the Historian of Thought Edouard d'Araille and has been provided as a complete text on Academia.edu for the last twelve months, courtesy of Living Time Global, the publishers. In place of the complete text, a key extract from the work is now provided at this web location.

Actual Problems of Mind. Philosophy Journal, (22), 108-136. https://doi.org/10.31812/apd.v0i22.4445

Andrii Leonov

In this paper, I am dealing with the phenomena of "life" and "death". The questions that I attempt to answer are "What is life, and what is death?" "Is it bad to die?" and Is there life after death?. The method that I am using in this paper is that of phenomenology. The latter I understand as an inquiry into meaning, that is, what makes this or that phenomenon as such. Thus, I am approaching the phenomena in question from the point of view of their meaning in the first place. I claim that ordinarily we constitute phenomena of "life" and "death" in a twofold way. When it comes to "life", one can specify "life-as-biological", and "life-as-a-possibility" senses. The former I understand as a cluster of biological processes that unfold in physical time. By "life-as-a-possibility", I understand a cluster of projects, potentials that depend on our subjectivity. I claim that we essentially perceive life-as-biological through life-as-a-possibility. When it comes to "death", I argue that we essentially constitute this phenomenon in a similar manner. On the one hand, we perceive "death" in the "death-as-biological/physical" sense which signifies the end of the organism's biological processes. On the other hand, we constitute "death" as the "existential/practical death"/"death-of-possibility." By that I mean an annihilation of all possibilities, and projects. In short, it is a situation when one's life suddenly loses all its meaning and value: death of meaning. I argue that what constitutes the significance of "death-as-biological" for us is what I call the "existential/practical death" or "death-of-possibility". I use the phenomena of mourning and suicide to illustrate my point better. Reflecting on whether it is bad to die, I claim that if we accept the hypotheses I am defending in the paper, it appears that death is bad because it entails the loss of all possibilities. I also want to show that people’s desire for immortality is in fact reasonable, because the more one lives, the more possibilities one is able to realize. In other words, people’s desire for immortality is grounded in the essential understanding of the phenomenon of life" as a possibility. Reflecting on whether there is life after death, my answer is twofold. Since there is no scientific evidence of life after physical/biological death, I think there is no reason to believe in such as well. But when it comes to the question whether there is life after the existential/practical death, my answer is positive: "Yes, there is!" I try to show that it is always possible to find the meaning of life even in the light of the most terrible events. In this sense, there is always a light at the end of the tunnel.

RELATED PAPERS

Orsolya Szekeresné Varga

Masculinities Social Change

Maria Padros

AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ ELMLƏR AKADEMİYASI MƏHƏMMƏD FÜZULİ adına ƏLYAZMALAR İNSTİTUTU: Elmi əsərlər

Aysel Hasanova

Jila Naeini

Corina Scutari

Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training

Karin Heinrichs

Jurnal Biota

Dina Chamidah

Nonlinearity

Joydev Chattopadhyay

Gender and Education

Marcia G. Synnott

Journal of Hematology & Oncology

Michal Abraham

International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences

Sikha Dutta

Proceedings of the 2014 conference on Innovation & technology in computer science education - ITiCSE '14

Shuchi Grover

Gulsumxanim Hasilova

Anaesthesia

Alexis P Arnaud

Acta Alimentaria

Rita Farkas

Asta Dambrauskaite

Sarimbit Keluarga Kekinian Terbaru Rumah Jahit Azka

rumahjahitazka kebumen

Journal of Vaccines & Vaccination

Rupsa Banerjee

Michael H Koplitz

Revue internationale de pédagogie de l’enseignement supérieur

Denis Bedard

Ignacio Viglizzo , Fernando Tohme

Eduardo Garzanti

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

This article considers several questions concerning death and its ramifications.

First , what constitutes death? It is clear enough that people die when their lives end, but less clear what constitutes the ending of a person's life.

Second , in what sense might death or posthumous events harm us? To answer this question, we will need to know what it is for something to be in our interests.

Third , what is the case for and the case against the harm thesis , the claim that death can harm the individual who dies, and the posthumous harm thesis , according to which events that occur after an individual dies can still harm that individual?

Fourth , how might we solve the timing puzzle? This puzzle is the problem of locating the time during which we incur harm for which death and posthumous events are responsible.

A fifth controversy concerns whether all deaths are misfortunes or only some. Of particular interest here is a dispute between Thomas Nagel, who says that death is always an evil, since continued life always makes good things accessible, and Bernard Williams, who argues that, while premature death is a misfortune, it is a good thing that we are not immortal, since we cannot continue to be who we are now and remain meaningfully attached to life forever.

A final controversy concerns whether or not the harmfulness of death can be reduced. It may be that, by adjusting our conception of our well-being, and by altering our attitudes, we can reduce or eliminate the threat death poses us. But there is a case to be made that such efforts backfire if taken to extremes.

2. Misfortune

3. the harm theses, 4. the timing puzzle, 5. is death always a misfortune.

- 6. Can Death's Harmfulness be Reduced?

Bibliography

Other internet resources, related entries.

Death is life's ending. Let us say that vital processes are those by which organisms develop or maintain themselves. These processes include chemosynthesis, photosynthesis, cellular respiration, cell generation, and maintenance of homeostasis. Then death is the ending of the vital processes by which an organism sustains itself. However, life's ending is one thing, and the condition of having life over is another. ‘Death’ can refer to either.

Let us add that ‘the ending of life’ is itself potentially ambiguous. On one hand it might be a process wherein our lives are progressively extinguished, until finally they are gone. On the other it might be a momentary event. This event might be understood in three ways. First, it might be the ending of the dying process—the loss of the very last trace of life. Call this ‘denouement death’. Second, it might be the point in the dying process when extinction is assured, no matter what is done to stop it. Call this moment ‘threshold death’. A third possibility is that life ends when the physiological systems of the body irreversibly cease to function as an integrated whole (defended, for example, by Belshaw 2009). Call this ‘integration death’.

Thus death can be a state (being dead), the process of extinction (dying), or one of three events that occur during the dying process. Death in all of these senses can be further distinguished from events—such as being shot with an arrow—that cause death.

1.1 The Permanence of Death

‘Death’ is also unclear in at least two ways. First, the concept of life is not entirely clear. For example, suppose we could construct a machine, the HAL 1.01, with (nearly) all of the psychological attributes of persons: would HAL 1.01 be alive? To the extent that we are puzzled about what life entails, we will be puzzled about what is entailed by the ending of life, that is, death. (For accounts of life, see Van Inwagen 1990 or Luper 2009.) Second, it seems somewhat indeterminate whether a temporary ending of life suffices for death, or whether death entails a permanent loss of life. Usually, whenever a creature's life stops, the condition is permanent; so ‘death’, as commonly used, need not be sensitive to the distinction between the temporary and permanent ending of life. Yet life may stop temporarily: a life might be suspended then revived . Or it might be restored . Life in the case of seeds and spores is suspended indefinitely. Freezing frogs and human embryos suspends their lives, too. Suppose that I were frozen and later revived: it is tempting to say that my life stops while I am frozen —I am in a state of suspended animation. But I am not dead. Now imagine a futuristic device, the Disassembler-Reassembler , that reduces me to small cubes, or individual cells, or disconnected atoms, which it stores and later reassembles just as they were before. Many of us will say that I would survive—my life would continue—after Reassembly, but it is quite clear that I would not live during intervals when my atoms are stacked in storage. I would not even exist during such intervals; Disassembly kills me. After I cease to exist, presumably I cannot be revived; nor can my vital processes be revived. If I can be Reassembled, my life would be restored, not revived. Restoration, not revival, is a way of bringing a creature back from the dead.

Assuming that creatures whose lives are suspended are not dead, but creatures who are Disassembled are dead even if later Reassembled, it might be best to say that a creature has died just when its vital processes are irreversibly discontinued, that is, when its vital processes can no longer be revived.

1.2 Death and What We Are

Death for you and me is constituted by the irreversible discontinuation of the vital processes by which we are sustained. This characterization of death could be sharpened if we had a clearer idea of what we are , and the conditions under which we persist. However, the latter is a matter of controversy.

There are three main views: animalism , which says that we are human beings (Snowdon 1990, Olson 1997, 2007); personism , which says that we are creatures with the capacity for self-awareness; and mindism , which says that we are minds (which may or may not have the capacity for self-awareness) (McMahan 2002). Animalism suggests that we persist over time just in case we remain the same animal; mindism suggests that we persist just when we remain the same mind. Personism is usually paired with the view that our persistence is determined by our psychological features and the relations among them (Locke 1689, Parfit 1984).

If we are animals, with the persistence conditions of animals, our deaths are constituted by the irreversible cessation of the vital processes that sustain our existence as human beings. If we are minds, our deaths are constituted by the irreversible extinction of the vital processes that sustain our existence as minds. And if persistence is determined by our retaining certain psychological features, then the loss of those features will constitute death.

These three ways of understanding death have very different implications. Severe dementia can destroy a great many psychological features without destroying the mind, which suggests that death as understood by personists can occur even though death as understood by mindists has not. Moreover, human beings sometimes survive the destruction of the mind, as when the cerebrum dies, leaving an individual in a persistent vegetative state. It is also conceivable that the mind can survive the extinction of the human being: this might occur if the brain is removed from the body, kept alive artificially, and the remainder of the body is destroyed (assuming that a bare brain is not a human being). These possibilities suggest that death as understood by mindists can occur even though death as understood by animalists has not (and also that the latter sort of death need not be accompanied by the former.)

1.3 Death and Existence

What is the relationship between existence and death? May people and other creatures continue to exist after dying, or cease to exist without dying?

Take the first question: may you and I and other creatures continue to exist for some time after our lives end? The view that death entails our annihilation has been called the termination thesis (Feldman 2000). The position that we can indeed survive death we might call the dead survivors view . The dead survivors view might be defended on the grounds that we commonly refer to ‘dead animals’ (and ‘dead plants’) which may suggest that we believe that animals continue to exist, as animals, while no longer alive. The idea might be that an animal continues to count as the same animal if enough of its original components remain in much the same order, and animals continue to meet this condition for a time following death (Mackie 1997). On this view, if you and I are animals (as animalists say) then we could survive for a time after we are dead, albeit as corpses. In fact, we could survive indefinitely, by arranging to have our corpses preserved.

However, this way of defending the dead survivors view may not be decisive. The terms ‘dead animal’ and ‘dead person’ seem ambiguous. Normally, when we use ‘dead people’ or ‘dead animal’ we mean to speak of persons or animals who lived in the past. One dead person I can name is Socrates; he is now a ‘dead person’ even though his corpse surely has ceased to exist. However, in certain contexts, such as in morgues, we seem to use the terms ‘dead animal’ and ‘dead person’ to mean “remains of something that was an animal” or “remains of something that was a person.” On this interpretation, even in morgues calling something a dead person does not imply that it is a person.

What about the second question: can creatures cease to exist without dying? Certainly things that never were alive, such as bubbles and statues, can be deathlessly annihilated. Arguably, there are also ways that living creatures can be deathlessly annihilated. It is plausible to say that an amoeba's existence ends when it splits, replacing itself with two amoebas. Yet when amoebas split, the vital processes that sustain them do not cease. If people could divide like amoebas, perhaps they, too could cease to exist without dying. (For a famous discussion of division and its implications, see Parfit 1981.)

1.4 Criteria for Death

Defining death is one thing; providing criteria by which it can be readily detected or verified is another. A definition is an account of what death is ; when, and only when its definition is met, death has necessarily occurred. The definition offered above was that a creature is dead just when the vital processes by which it is sustained have irreversibly ceased. A criterion for death, by contrast, lays out conditions by which all and only actual deaths may be readily identified. Such a criterion falls short of a definition, but plays a practical role. For example, it would help physicians and jurists determine when death has occurred.

In the United States, the states have adopted criteria for death modeled on the Uniform Determination of Death Act (developed by the President's Commission, 1981), which says that “an individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead. A determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.” In the United Kingdom, the accepted criterion is brain stem death, or the “permanent functional death of the brain stem” (Pallis 1982).

These current criteria are subject to criticism. Animalists might resist the criteria since the vital processes of human beings whose entire brains have ceased irreversibly to function can be sustained artificially using cardiopulmonary assistance. Mindists and personists might also resist the criteria, on the grounds that minds and all psychological features can be irretrievably destroyed in human beings whose brain stems are intact. For example, cerebral death can leave its victim with an intact brain stem, yet mindless and devoid of self-awareness.

May death or posthumous events harm us? Might they benefit us? Perhaps; in order to decide, we will need an analysis of welfare , which tells us what well-being is and how well off we are. We will also need an account of personal interests , which tells us what it is for something to be in our interests or against our interests.

2.1 Comparativism

The most widely accepted account of our interests is comparativism . In order to clarify comparativism, it is best to distinguish different senses in which an event can have value.

Some events are intrinsically good (or bad) for a subject; such events are good (bad) for their own sakes, rather than in virtue of their contingent effects. By contrast, some events are extrinsically good (bad) for a subject; they are good (bad) because of their contingent effects. For example, many people count their pleasure as intrinsically good and their pain as intrinsically bad; aspirin would be extrinsically good, since it eliminates pain, and really bad puns would be extrinsically bad in that they are painful.

Events can have value in a different way: they can be overall good (bad) for a subject; that is, they can be good (bad) all things considered. Events are overall good (bad) for me when (and to the extent that) they make my life better (worse) than it would be if those events had not occurred. Contrast events that are partially good (bad) for me: these make my life better (worse) only in some respects. Partial goods may be overall bad for me. For example, playing video games every day gives me pleasure, and is hence partially good for me, but if it also causes me to neglect my job, health and family, it might well be overall bad for me.

According to comparativism, the value an event E has for me is roughly E 's overall value for me. But let us attempt to formulate the comparativist account a bit more precisely.

To assess the value for me of an event E , we begin by distinguishing two possible situations, or possible worlds. One of these is the actual world, which is the world as it actually is, past present and future. The other is the possible world that is the way things would be if E had not occurred. We can assume that this is the world that is as similar to the actual world as possible, and in that way ‘closest’ to the actual world, except that E does not occur, and various other things are different because of E 's nonoccurrence. We can call the actual world W E , in this way reminding ourselves that E actually occurred. And by W ~ E we can indicate the closest world to the actual world in which E does not occur. Here the tilde, ‘~’, stands for ‘not’.

The next step is to assess my welfare level in W E and my welfare level in W ~ E . My welfare level in W E is the intrinsic value for me of my life in W E ; it is the value my life actually has for me, measured in terms of intrinsic goods and intrinsic evils. To calculate my welfare level in W E , we start by assigning a value to my intrinsic goods in W E . This will be a positive value representing the sum of these goods. Next we assign a value to my intrinsic evils in W E ; this will be a negative value. Next we sum these values; the goods will raise this sum, while the evils will lower it. Some symbolism might help fix ideas (although it may give the false impression that our subject matter admits of more precision that is actually possible). Let G ( S , W ) stand for the sum of the values of S 's intrinsic goods in world W, and let B ( S , W ) stand for the sum of the values of S 's intrinsic evils in W . So far we have said that S 's welfare level in W E equals G ( S , W E ) + B ( S , W E ). If we let IV ( S , W ) stand for the intrinsic value of world W for subject S , the claim is that

IV ( S , W E ) = G ( S , W E ) + B ( S , W E ).

My welfare level in W ~ E is assessed similarly; it is the sum of my intrinsic goods and evils in W ~ E .

Finally, we subtract the value for me of my life in W ~ E from the value for me of my life in W E . According to comparativism, this is the value E has for me. Letting V ( S , E ) stand for the value of E for subject S, comparativism says that

V ( S , E ) = IV ( S , W E ) − IV ( S , W ~ E ).

This value determines whether an event is overall bad (good) for a subject S . If E 's value for S is negative, that is, if V ( S , E ) < 0, then E is overall bad for S . If E 's value is positive, then E is overall good for S . The more negative (positive) E 's value is, the worse (better) E is for S .

Consider an example. Suppose that we are looking to identify the value for me of drinking this cup of coffee. Call this event Drink . Then the first step is to distinguish the actual world, W Drink , in which I drank the coffee, from the closest world in which I did not, W ~ Drink . Then we calculate my welfare level in W Drink , IV ( Luper , W Drink ) and in W ~ Drink , IV ( Luper , W ~ Drink ). The former, IV ( Luper , W Drink ), equals the value of the intrinsic goods I will enjoy in my life plus the value of the intrinsic evils I will endure. For simplicity, let us pull a number out of the hat to indicate the value of the goods I will enjoy in my life before I drink the coffee, say 100, and another number to indicate the value of the evils I will endure in my life before I drink the coffee, say −50. Let us also assume that drinking the coffee will give me some pleasure for one hour, which has a value of 10, and drinking the coffee will not cause me to endure any evils. Finally, let us assume that after that hour of savoring my coffee, I will go on to enjoy goods with a value of 50, and evils with a value of −10. Then IV ( Luper , W Drink ) = 100 + 10 + 50 + −50 + 0 + −10 = 100. Assuming that my life one hour after drinking my coffee would be just like my life would have been were I not to drink my coffee, more or less, so that drinking my coffee benefits me only during the hour I savor it, we can say that IV ( Luper , W ~ Drink ) = 100 + 0 + 50 + −50 + 0 + −10 = 90. Given these assumptions, V ( Luper , W Drink ) = IV ( Luper , W Drink ) − IV ( Luper , W ~ Drink ) = 100 − 90 = 10. Drinking the coffee, then, was good for me, as 10 is a positive value.

We can now offer a rough statement of the comparativist account of interests.

An event E is in S 's interests just in case E overall benefits (is good for) S , making S 's life better than it would have been if E had not occurred, which E does just when its value for S is positive. An event E is against S 's interests just in case E overall harms (is bad for) S , making S 's life worse than it would have been if E had not occurred, which E does just when its value for S is negative. How much E benefits (harms) S depends on how much better (worse) S 's life is in the actual world than it would have been if E had not occurred: the better (worse) S 's life is, the more beneficial (harmful) E is.

In order to refine the comparativist account, we will need to distinguish between event tokens and event types . Event tokens are concrete events, such as the bombing of the World Trade Center. Event types are abstract entities such as bombings, leapings and burials. One token of the type bombing is the bombing of the World Trade Center. Earlier we used the letter ‘ E ’ to refer to event tokens rather than event types. What is more, we assumed that the event tokens to which ‘ E ’ referred were actual events, not merely possible events. But perhaps we can also offer a comparativist account of the value of the occurrence of an E -type event; that is, a comparativist account of how valuable it would be for a subject S if an event of type E were to occur.

To this end, we might assess the value for S of the occurrence of an E -type event by working out S 's welfare level in the actual world (where presumably an E -type event did not occur) then S 's welfare level in the closest world in which an E -type event does occur, and subtracting the first from the second. When the result is a positive value, the occurrence of an E -type event would be good for S ; when negative, the occurrence would be bad for S .

In sum, the comparativist view may be stated as follows:

Comparativist Account of Interests : An event E is in S 's interests just in case E overall benefits (is good for) S , making S 's life better than it would have been if E did not occur, which E does just when its value for S is positive. An event E is against S 's interests just in case E overall harms (is bad for) S , making S 's life worse than it would have been if E did not occur, which E does just when its value for S is negative. The occurrence of an E -type event is in S 's interests just in case it would overall benefit (be good for) S . The occurrence of an E -type event would benefit S if and only if its value for S is positive. The occurrence of an E -type event is against S 's interests just in case it would overall harm (be bad for) S . The occurrence of an E -type event would harm S if and only if its value for S is negative. How much E benefits (harms) S depends on how much better (worse) S 's life is in the actual world than it would have been if E had not occurred: the better (worse) S 's life is, the more beneficial (harmful) E is. Similarly, how much the occurrence of an E-type event would benefit (harm) S depends on how much worse (better) S 's life is in the actual world than it would have been if an E -type event had occurred: the worse (better) S 's life is, the more beneficial (harmful) the occurrence of an E -type event would have been.

We sometimes say things that suggest that we can have interests at particular times which we lack at others. For example, we might say that having a tooth drilled by a dentist is not in our interests while we are undergoing the procedure, even though it is in our long-term interests. The idea seems to be that what makes a subject S better off at time t is in S 's interests-at-time- t . But it is important to distinguish interests-at-t from interests . What is in our interests-at-time- t 1 need not be in our interests-at-time- t 2 . This is not true of our interests. Whatever interests we have we have at all times. If something is in our interests, it is timelessly in our interests.

2.2 Welfare

Comparativism analyses our interests in terms of our welfare, and is compatible with any number of views of welfare. There are three main ways of understanding welfare itself: positive hedonism, preferentialism, and pluralism. Let us briefly consider each of these three views.

Positive hedonism is the following position:

Positive Hedonism : for any subject S , experiencing pleasure at t is the one and only thing that is intrinsically good for S at t , while experiencing pain at t is the one and only thing that is intrinsically bad for S at t . The more pleasure (pain) S experiences at t , the greater the intrinsic good (evil) for S at t .

Positive hedonism has been defended (by J.S.Mill 1863) on the grounds that it resolves the problem of commensurability. The difficulty arises when we attempt to equate units of different sorts of goods. For example, how do we decide when one unit of love is worth one unit of achievements, assuming that both love and achievements are intrinsically good? The problem does not arise for hedonists, who evaluate all things in terms of the pleasure and pain that they give us.

However, most theorists consider positive hedonism to be implausible. Nagel argues that I would harm you if I were to cause you to revert to a pleasant infantile state for the rest of your life, yet by hedonist standards I have not harmed you at all. Similarly, it would be a grave misfortune for you if your spouse came to despise you, but for some reason pretended to love you, so that you underwent no loss of pleasure. And Nozick notes that we would refuse to attach ourselves to an Experience Machine that would give us extremely pleasant experiences for the rest of our lives. By hypothesis, the Machine would give us far more pleasure (and less pain) than is otherwise possible. Our reluctance to use the Machine suggests that things other than pleasure are intrinsically good: it is because we do not wish to miss out on these other goods that we refuse to use the Machine.

Preferentialism assesses welfare in terms of desire fulfillment. To desire is to desire that some proposition P hold; when we desire P , P is the object of our desire. According to preferentialism, our welfare turns on whether the objects of our desires hold:

Preferentialism : for any subject S , it is intrinsically good for S at t that, at t , S desires P and P holds; it is intrinsically bad for S at t that, at t , S desires P and ~ P holds. The stronger S 's desire for P is, the better (worse) it is for S that P holds (~ P holds).

In this, its unrefined form, preferentialism is implausible. Many of the things we desire do not appear to contribute to our welfare. Consider, for example, Rawls' famous example of the man whose main desire is to count blades of grass. In response to the grass counter case, Rawls (1971) adopts critical preferentialism , which says that welfare is advanced by the fulfillment of rational aims. Assuming that counting grass blades is irrational because it is pointless, fulfilling the desire to count grass blades is not intrinsically good. However, even critical preferentialism seems vulnerable to attack, since the fulfillment even of rational desires need not advance one's welfare. Parfit (1984) illustrates the point by supposing that you have the (rational) desire that a stranger's disease be overcome: the fulfilment of this desire advances the stranger's welfare, not yours. This example can be handled by egocentric preferentialism, which says that only desires that make essential reference to the self can advance our welfare when fulfilled (Overvold 1980). Thus the fulfilment of my desire that I be happy is intrinsically good for me, but the fulfilment of my desire that somebody or other be happy is not. A further variant of preferentialism might be called achievement preferentialism . This view says that subject S 's accomplishing one of S 's goals (or ends) is intrinsically good for S , and that being thwarted from accomplishing such a goal is intrinsically bad for S (Scanlon 1998; Keller 2004; Portmore 2007).

Pluralism is the third main account of welfare. Pluralists can agree with the hedonist position that a person's pleasure is intrinsically good for that person, and with the preferentialist's view that the fulfilment of a person's desire is intrinsically good for that person. However, pluralism says that various other sorts of things are intrinsically good, too. Some traditional examples are wisdom, friendship and love, and honor. Another example might be engaging in self-determination (Luper 2009).

Typically, those who value life accept the harm thesis: death is, at least sometimes, bad for those who die, and in this sense something that ‘harms’ them. It is important to know what to make of this thesis, since our response itself can be harmful. This might happen as follows: suppose that we love life, and reason that since it is good, more would be better. Our thoughts then turn to death, and we decide it is bad: the better life is, we think, the better more life would be, and the worse death is. At this point, we are in danger of condemning the human condition, which embraces life and death, on the grounds that it has a tragic side, namely death. It will help some if we remind ourselves that our situation also has a good side. Indeed, our condemnation of death is here based on the assumption that more life would be good. But such consolations are not for everyone. (They are unavailable if we crave immortality on the basis of demanding standards by which the only worthwhile projects are endless in duration, for then we will condemn the condition of mere mortals as tragic through and through, and may, as Unamuno (1913) points out, end up suicidal, fearing that the only life available is not worth having.) And a favorable assessment of life may be a limited consolation, since it leaves open the possibility that, viewing the human condition as a whole, the bad cancels much of the good. In any case it is grim enough to conclude that, given the harm thesis, the human condition has a tragic side. It is no wonder that theorists over the millennia have sought to defeat the harm thesis. We will examine their efforts, as well as the challenges to the posthumous harm thesis, according to which events occurring after we die can harm us. First, however, let us see how the harm theses might be defended.

3.1 The Main Defense

Those theorists who defend the harm theses typically draw upon some version of comparativism (e.g., Nagel 1970, Quinn 1984, Feldman 1991). According to comparativism, a person's death may well harm that person. Death may also be harmless. To decide whether a person's death is bad for that person, we must compare her actual welfare level to the welfare level she would have had if she had not died. Suppose, for example, that Hilda died on December 1, 2008 at age 25 and that, had she not died, she would have prospered for 25 years and suffered during her final five years. To apply comparativism, we must first select an account of welfare with which to assess Hilda's well-being. For simplicity, let us adopt positive hedonism. The next step is to sum the pleasure and pain she had over her lifetime. Suppose that she had considerably more pleasure than pain. We can stipulate that her lifetime welfare level came to a value of 250. Next we sum the pleasure and pain she would have had if she had not died on December 1, 2008. The first 25 years of her life would be just as they actually were, so the value of these would be 250. We can suppose that her next 25 years would also receive the value of 250. And let us stipulate that her final 5 years, spent mostly suffering, carry a value of −50. Then, had she not died, her lifetime welfare level would have been 250 + 250 − 50 = 450. Subtracting this value from her actual lifetime welfare level of 250 gives us −200. This is the value for her of dying on December 1, 2008. According to comparativism, then, her death was quite bad for her. Things would have been different if the last 30 years of her life would have been spent in unrelenting agony. On that assumption, her death would have been good for her.

Our example concerned a particular death at a specific time. Comparativism also has implications concerning whether dying young is bad for the one who dies, and whether it is bad for us that we die at all. In both cases the answer depends on how our lives would have gone had we not died. Usually dying young deprives us of many years of good life, so usually dying young is bad for us. As for whether or not it is bad to be mortal, that depends on whether the life we would lead as an immortal being would be a good one or not.

According to comparativism, when death is bad for us, it is bad for us because it precludes our coming to have various intrinsic goods which we would have had if we had not died. We might say that death is bad for us because of the goods it deprives us of, and not, or at least not always, because of any intrinsic evils for which it is responsible.

So much for the harm thesis. Now let us ask how the posthumous harm thesis might be defended.

Note first that we must reject the posthumous harm thesis if we adopt positive hedonism and combine it with comparativism, for nothing that happens after we die can boost or reduce the amounts of pleasure or pain in our lives.

However, posthumous events might well be bad for us on other accounts of welfare. Suppose that I want to be remembered after I die. Given preferentialism, something could happen after I die that might be bad for me, namely my being forgotten, because it thwarts my desire.

These ways of defending the harm theses seem quite plausible. Nevertheless, there are several strategies for criticizing the harm theses. Let us turn to these criticisms now, starting with some strategies developed in the ancient world by Epicurus and his follower Lucretius.

3.2 The Symmetry Argument

One challenge to the harm thesis is an attempt to show that the state death puts us in, nonexistence, is not bad. According to the symmetry argument , posed by Lucretius, a follower of Epicurus, we can prove this to ourselves by thinking about our state before we were born:

Look back at time … before our birth. In this way Nature holds before our eyes the mirror of our future after death. Is this so grim, so gloomy? (Lucretius 1951)

The idea is clear to a point: it is irrational to object to death, since we do not object to pre-vital nonexistence (the state of nonexistence that preceded our lives), and the two are alike in all relevant respects, so that any objection to the one would apply to the other. However, Lucretius' argument admits of more than one interpretation, depending on whether it is supposed to address death understood as the ending of life or death understood as the state we are in after life is ended (or both).

On the first interpretation, the ending of life is not bad, since the only thing we could hold against it is the fact that it is followed by our nonexistence, yet the latter is not objectionable, as is shown by the fact that we do not object to our nonexistence before birth. So understood, the symmetry argument is weak. Our complaint about death need not be that the state of nonexistence is ghastly. Instead, our complaint might be that death brings life, which is a good thing, to an end, and, all things being equal, what ends good things is bad. Notice that the mirror image of death is birth (or, more precisely, becoming alive), and the two affect us in very different ways: birth makes life possible; it starts a good thing going. Death makes life impossible; it brings a good thing to a close. As Frances Kamm (1998) emphasizes, we do not want our lives to be all over with.

Perhaps Lucretius only meant to argue that the death state is not bad, since the only thing we could hold against the death state is that it is nonexistence, which is not really objectionable, as witness our attitude about pre-vital nonexistence. So interpreted, there is a kernel of truth in Lucretius' argument. Truly, our pre-vital nonexistence does not concern us much. But that is because pre-vital nonexistence is followed by existence. Nor would we worry overly about post-vital nonexistence if it, too, were followed by existence. If we could move in and out of existence, say with the help of futuristic machines that could dismantle us, then rebuild us, molecule by molecule, after a period of nonexistence, we would not be overly upset about the intervening gaps, and, rather like hibernating bears, we might enjoy taking occasional breaks from life while the world gets more interesting. But undergoing temporary nonexistence is not the same as undergoing permanent nonexistence. Unlike the former, the latter entails death in the fullest sense. What is upsetting is the death that precedes post-vital nonexistence — or, what comes to the same thing, the permanence of post-vital nonexistence — not nonexistence per se.

There is another way to use considerations of symmetry to argue against the harm thesis: we want to die later, or not at all, because it is a way of extending life, but this attitude is irrational, Lucretius might say, since we do not want to be born earlier (we do not want to have always existed), which is also a way to extend life. As this argument suggests, we are more concerned about the indefinite continuation of our lives than about their indefinite extension . (Be careful when you rub the magic lamp: if you wish that your life be extended, the genie might make you older!) A life can be extended by adding to its future or to its past. Some of us might welcome the prospect of having lived a life stretching indefinitely into the past, given fortuitous circumstances. But we would prefer a life stretching indefinitely into the future.