Defining and measuring oligopoly

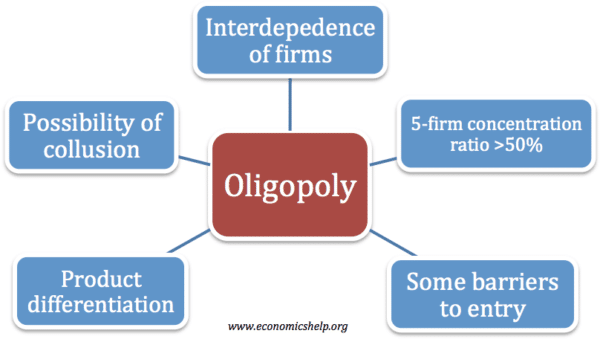

Concentration ratios

Example of a hypothetical concentration ratio, fixed broadband services, fuel retailing, further examples, the herfindahl – hirschman index (h-h index), key characteristics, interdependence.

- Whether to compete with rivals, or collude with them.

- Whether to raise or lower price, or keep price constant.

- Whether to be the first firm to implement a new strategy, or whether to wait and see what rivals do. The advantages of ‘going first’ or ‘going second’ are respectively called 1st and 2nd-mover advantage. Sometimes it pays to go first because a firm can generate head-start profits. 2nd mover advantage occurs when it pays to wait and see what new strategies are launched by rivals, and then try to improve on them or find ways to undermine them.

Barriers to entry

Natural entry barriers include:, economies of large scale production., ownership or control of a key scarce resource, high set-up costs, high r&d costs, artificial barriers include:, predatory pricing, limit pricing, superior knowledge, predatory acquisition, advertising, a strong brand, loyalty schemes, exclusive contracts, patents and licences, vertical integration, collusive oligopolies, types of collusion, competitive oligopolies, pricing strategies of oligopolies.

- Oligopolists may use predatory pricing to force rivals out of the market. This means keeping price artificially low, and often below the full cost of production.

- They may also operate a limit-pricing strategy to deter entrants, which is also called entry forestalling price .

- Oligopolists may collude with rivals and raise price together, but this may attract new entrants.

- Cost-plus pricing is a straightforward pricing method, where a firm sets a price by calculating average production costs and then adding a fixed mark-up to achieve a desired profit level. Cost-plus pricing is also called rule of thumb pricing.There are different versions of cost-pus pricing, including full cost pricing , where all costs - that is, fixed and variable costs - are calculated, plus a mark up for profits, and contribution pricing , where only variable costs are calculated with precision and the mark-up is a contribution to both fixed costs and profits.

Non-price strategies

- Trying to improve quality and after sales servicing, such as offering extended guarantees.

- Spending on advertising, sponsorship and product placement - also called hidden advertising – is very significant to many oligopolists. The UK's football Premiership has long been sponsored by firms in oligopolies, including Barclays Bank and Carling.

- Sales promotion, such as buy-one-get-one-free (BOGOF), is associated with the large supermarkets, which is a highly oligopolistic market, dominated by three or four large chains.

- Loyalty schemes, which are common in the supermarket sector, such as Sainsbury’s Nectar Card and Tesco’s Club Card .

- How successful is it likely to be?

- Will rivals be able to copy the strategy?

- Will the firms get a 1st - mover advantage?

- How expensive is it to introduce the strategy? If the cost of implementation is greater than the pay-off, clearly it will be rejected.

- How long will it take to work? A strategy that takes five years to generate a pay-off may be rejected in favour of a strategy with a quicker pay-off.

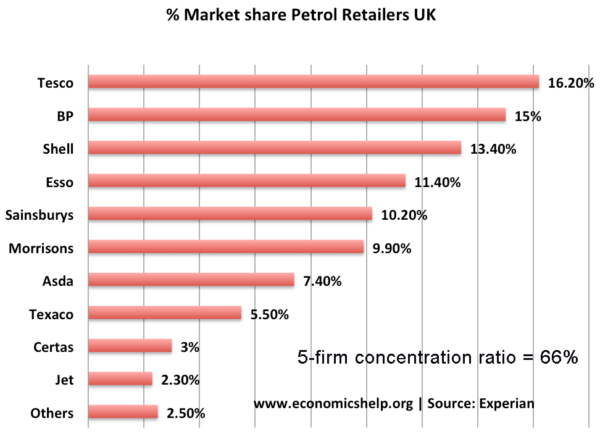

Price stickiness

Kinked demand curve.

Maximising profits

A game theory approach to price stickiness.

- Raise price

- Lower price

- Keep price constant

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

- Higher prices or hidden prices, such as the hidden charges in credit card transactions

- Lower output

- Restricted choice or other limiting conditions associated with the transaction

Examples of Oligopoly

Evaluation of oligopolies, the disadvantages of oligopolies.

- High concentration reduces consumer choice.

- Cartel-like behaviour reduces competition and can lead to higher prices and reduced output.

- Given the lack of competition, oligopolists may be free to engage in the manipulation of consumer decision making. By making decisions more complex - such as financial decisions about mortgages - individual consumers fall back on heuristics and rule of thumb processes, which can lead to decision making bias and irrational behaviour, including making purchases which add no utility or even harm the individual consumer.

- Firms can be prevented from entering a market because of deliberate barriers to entry .

- There is a potential loss of economic welfare.

- Oligopolists may be allocatively and productively inefficient .

The advantages of oligopolies

- Oligopolies may adopt a highly competitive strategy, in which case they can generate similar benefits to more competitive market structures , such as lower prices. Even though there are a few firms, making the market uncompetitive, their behaviour may be highly competitive.

- Oligopolists may be dynamically efficient in terms of innovation and new product and process development. The super-normal profits they generate may be used to innovate, in which case the consumer may gain.

- Price stability may bring advantages to consumers and the macro-economy because it helps consumers plan ahead and stabilises their expenditure, which may help stabilise the trade cycle.

Test your knowledge with a quiz

Press next to launch the quiz, you are allowed two attempts - feedback is provided after each question is attempted..

Game Theory

Monopolistic competition

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 10. Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly

10.2 Oligopoly

Learning objectives.

- Explain why and how oligopolies exist

- Contrast collusion and competition

- Interpret and analyze the prisoner’s dilemma diagram

- Evaluate the tradeoffs of imperfect competition

Many purchases that individuals make at the retail level are produced in markets that are neither perfectly competitive, monopolies, nor monopolistically competitive. Rather, they are oligopolies. Oligopoly arises when a small number of large firms have all or most of the sales in an industry. Examples of oligopoly abound and include the auto industry, cable television, and commercial air travel. Oligopolistic firms are like cats in a bag. They can either scratch each other to pieces or cuddle up and get comfortable with one another. If oligopolists compete hard, they may end up acting very much like perfect competitors, driving down costs and leading to zero profits for all. If oligopolists collude with each other, they may effectively act like a monopoly and succeed in pushing up prices and earning consistently high levels of profit. Oligopolies are typically characterized by mutual interdependence where various decisions such as output, price, advertising, and so on, depend on the decisions of the other firm(s). Analyzing the choices of oligopolistic firms about pricing and quantity produced involves considering the pros and cons of competition versus collusion at a given point in time.

Why Do Oligopolies Exist?

A combination of the barriers to entry that create monopolies and the product differentiation that characterizes monopolistic competition can create the setting for an oligopoly. For example, when a government grants a patent for an invention to one firm, it may create a monopoly. When the government grants patents to, for example, three different pharmaceutical companies that each has its own drug for reducing high blood pressure, those three firms may become an oligopoly.

Similarly, a natural monopoly will arise when the quantity demanded in a market is only large enough for a single firm to operate at the minimum of the long-run average cost curve. In such a setting, the market has room for only one firm, because no smaller firm can operate at a low enough average cost to compete, and no larger firm could sell what it produced given the quantity demanded in the market.

Quantity demanded in the market may also be two or three times the quantity needed to produce at the minimum of the average cost curve—which means that the market would have room for only two or three oligopoly firms (and they need not produce differentiated products). Again, smaller firms would have higher average costs and be unable to compete, while additional large firms would produce such a high quantity that they would not be able to sell it at a profitable price. This combination of economies of scale and market demand creates the barrier to entry, which led to the Boeing-Airbus oligopoly for large passenger aircraft.

The product differentiation at the heart of monopolistic competition can also play a role in creating oligopoly. For example, firms may need to reach a certain minimum size before they are able to spend enough on advertising and marketing to create a recognizable brand name. The problem in competing with, say, Coca-Cola or Pepsi is not that producing fizzy drinks is technologically difficult, but rather that creating a brand name and marketing effort to equal Coke or Pepsi is an enormous task.

Collusion or Competition?

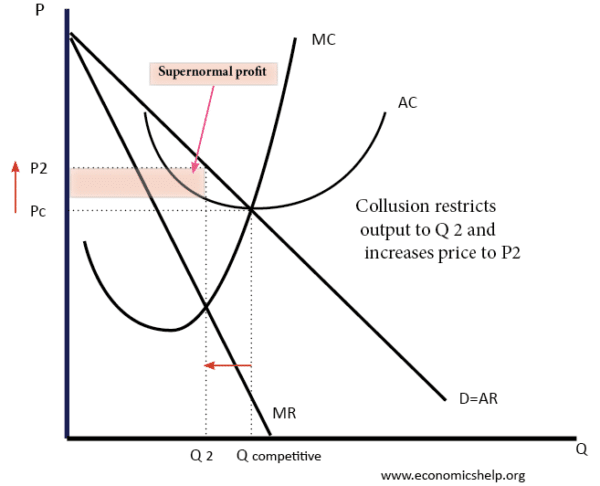

When oligopoly firms in a certain market decide what quantity to produce and what price to charge, they face a temptation to act as if they were a monopoly. By acting together, oligopolistic firms can hold down industry output, charge a higher price, and divide up the profit among themselves. When firms act together in this way to reduce output and keep prices high, it is called collusion . A group of firms that have a formal agreement to collude to produce the monopoly output and sell at the monopoly price is called a cartel . See the following Clear It Up feature for a more in-depth analysis of the difference between the two.

Collusion versus cartels: How can I tell which is which?

In the United States, as well as many other countries, it is illegal for firms to collude since collusion is anti-competitive behavior, which is a violation of antitrust law. Both the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission have responsibilities for preventing collusion in the United States.

The problem of enforcement is finding hard evidence of collusion. Cartels are formal agreements to collude. Because cartel agreements provide evidence of collusion, they are rare in the United States. Instead, most collusion is tacit, where firms implicitly reach an understanding that competition is bad for profits.

The desire of businesses to avoid competing so that they can instead raise the prices that they charge and earn higher profits has been well understood by economists. Adam Smith wrote in Wealth of Nations in 1776: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

Even when oligopolists recognize that they would benefit as a group by acting like a monopoly, each individual oligopoly faces a private temptation to produce just a slightly higher quantity and earn slightly higher profit—while still counting on the other oligopolists to hold down their production and keep prices high. If at least some oligopolists give in to this temptation and start producing more, then the market price will fall. Indeed, a small handful of oligopoly firms may end up competing so fiercely that they all end up earning zero economic profits—as if they were perfect competitors.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Because of the complexity of oligopoly, which is the result of mutual interdependence among firms, there is no single, generally-accepted theory of how oligopolies behave, in the same way that we have theories for all the other market structures. Instead, economists use game theory , a branch of mathematics that analyzes situations in which players must make decisions and then receive payoffs based on what other players decide to do. Game theory has found widespread applications in the social sciences, as well as in business, law, and military strategy.

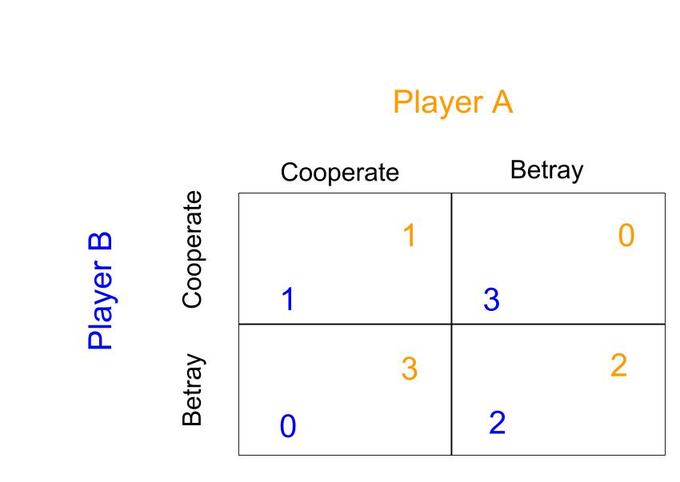

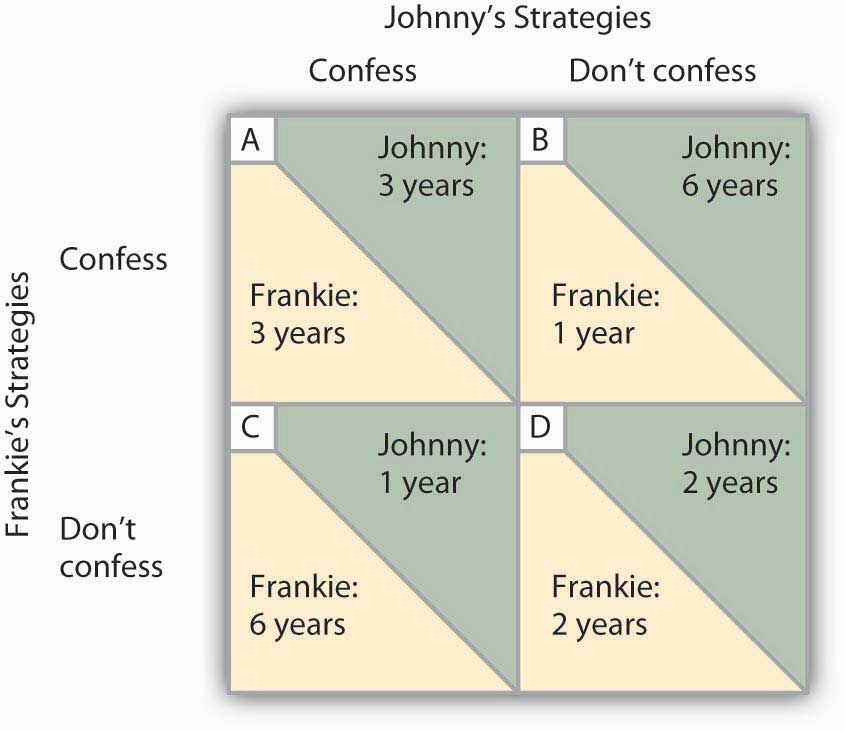

The prisoner’s dilemma is a scenario in which the gains from cooperation are larger than the rewards from pursuing self-interest. It applies well to oligopoly. The story behind the prisoner’s dilemma goes like this:

Two co-conspiratorial criminals are arrested. When they are taken to the police station, they refuse to say anything and are put in separate interrogation rooms. Eventually, a police officer enters the room where Prisoner A is being held and says: “You know what? Your partner in the other room is confessing. So your partner is going to get a light prison sentence of just one year, and because you’re remaining silent, the judge is going to stick you with eight years in prison. Why don’t you get smart? If you confess, too, we’ll cut your jail time down to five years, and your partner will get five years, also.” Over in the next room, another police officer is giving exactly the same speech to Prisoner B. What the police officers do not say is that if both prisoners remain silent, the evidence against them is not especially strong, and the prisoners will end up with only two years in jail each.

The game theory situation facing the two prisoners is shown in Table 3 . To understand the dilemma, first consider the choices from Prisoner A’s point of view. If A believes that B will confess, then A ought to confess, too, so as to not get stuck with the eight years in prison. But if A believes that B will not confess, then A will be tempted to act selfishly and confess, so as to serve only one year. The key point is that A has an incentive to confess regardless of what choice B makes! B faces the same set of choices, and thus will have an incentive to confess regardless of what choice A makes. Confess is considered the dominant strategy or the strategy an individual (or firm) will pursue regardless of the other individual’s (or firm’s) decision. The result is that if prisoners pursue their own self-interest, both are likely to confess, and end up doing a total of 10 years of jail time between them.

The game is called a dilemma because if the two prisoners had cooperated by both remaining silent, they would only have had to serve a total of four years of jail time between them. If the two prisoners can work out some way of cooperating so that neither one will confess, they will both be better off than if they each follow their own individual self-interest, which in this case leads straight into longer jail terms.

The Oligopoly Version of the Prisoner’s Dilemma

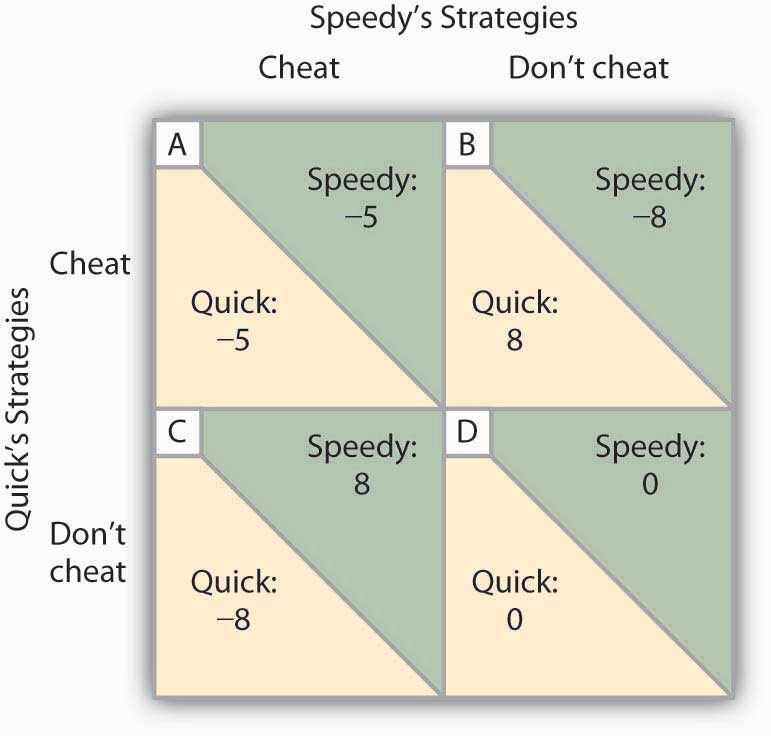

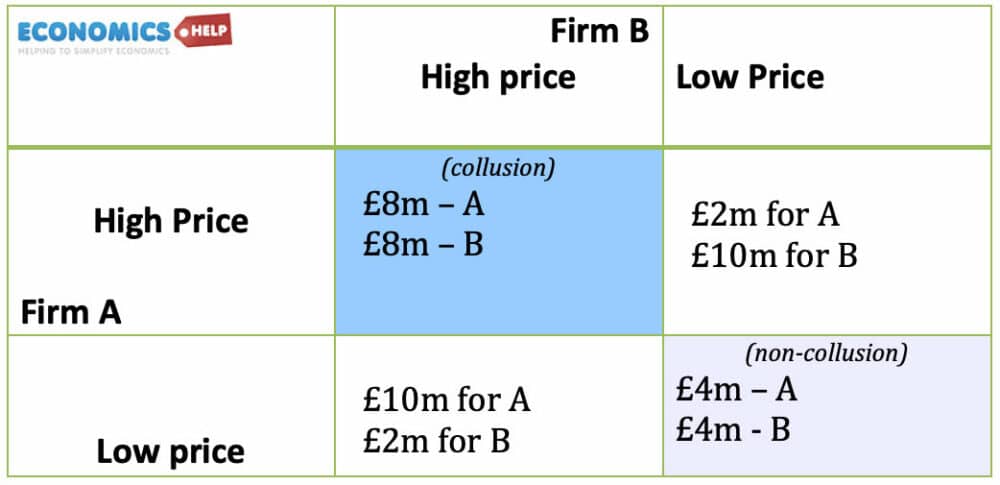

The members of an oligopoly can face a prisoner’s dilemma, also. If each of the oligopolists cooperates in holding down output, then high monopoly profits are possible. Each oligopolist, however, must worry that while it is holding down output, other firms are taking advantage of the high price by raising output and earning higher profits. Table 4 shows the prisoner’s dilemma for a two-firm oligopoly—known as a duopoly . If Firms A and B both agree to hold down output, they are acting together as a monopoly and will each earn $1,000 in profits. However, both firms’ dominant strategy is to increase output, in which case each will earn $400 in profits.

Can the two firms trust each other? Consider the situation of Firm A:

- If A thinks that B will cheat on their agreement and increase output, then A will increase output, too, because for A the profit of $400 when both firms increase output (the bottom right-hand choice in Table 4 ) is better than a profit of only $200 if A keeps output low and B raises output (the upper right-hand choice in the table).

- If A thinks that B will cooperate by holding down output, then A may seize the opportunity to earn higher profits by raising output. After all, if B is going to hold down output, then A can earn $1,500 in profits by expanding output (the bottom left-hand choice in the table) compared with only $1,000 by holding down output as well (the upper left-hand choice in the table).

Thus, firm A will reason that it makes sense to expand output if B holds down output and that it also makes sense to expand output if B raises output. Again, B faces a parallel set of decisions.

The result of this prisoner’s dilemma is often that even though A and B could make the highest combined profits by cooperating in producing a lower level of output and acting like a monopolist, the two firms may well end up in a situation where they each increase output and earn only $400 each in profits . The following Clear It Up feature discusses one cartel scandal in particular.

What is the Lysine cartel?

Lysine, a $600 million-a-year industry, is an amino acid used by farmers as a feed additive to ensure the proper growth of swine and poultry. The primary U.S. producer of lysine is Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), but several other large European and Japanese firms are also in this market. For a time in the first half of the 1990s, the world’s major lysine producers met together in hotel conference rooms and decided exactly how much each firm would sell and what it would charge. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), however, had learned of the cartel and placed wire taps on a number of their phone calls and meetings.

From FBI surveillance tapes, following is a comment that Terry Wilson, president of the corn processing division at ADM, made to the other lysine producers at a 1994 meeting in Mona, Hawaii:

I wanna go back and I wanna say something very simple. If we’re going to trust each other, okay, and if I’m assured that I’m gonna get 67,000 tons by the year’s end, we’re gonna sell it at the prices we agreed to . . . The only thing we need to talk about there because we are gonna get manipulated by these [expletive] buyers—they can be smarter than us if we let them be smarter. . . . They [the customers] are not your friend. They are not my friend. And we gotta have ‘em, but they are not my friends. You are my friend. I wanna be closer to you than I am to any customer. Cause you can make us … money. … And all I wanna tell you again is let’s—let’s put the prices on the board. Let’s all agree that’s what we’re gonna do and then walk out of here and do it.

The price of lysine doubled while the cartel was in effect. Confronted by the FBI tapes, Archer Daniels Midland pled guilty in 1996 and paid a fine of $100 million. A number of top executives, both at ADM and other firms, later paid fines of up to $350,000 and were sentenced to 24–30 months in prison.

In another one of the FBI recordings, the president of Archer Daniels Midland told an executive from another competing firm that ADM had a slogan that, in his words, had “penetrated the whole company.” The company president stated the slogan this way: “Our competitors are our friends. Our customers are the enemy.” That slogan could stand as the motto of cartels everywhere.

How to Enforce Cooperation

How can parties who find themselves in a prisoner’s dilemma situation avoid the undesired outcome and cooperate with each other? The way out of a prisoner’s dilemma is to find a way to penalize those who do not cooperate.

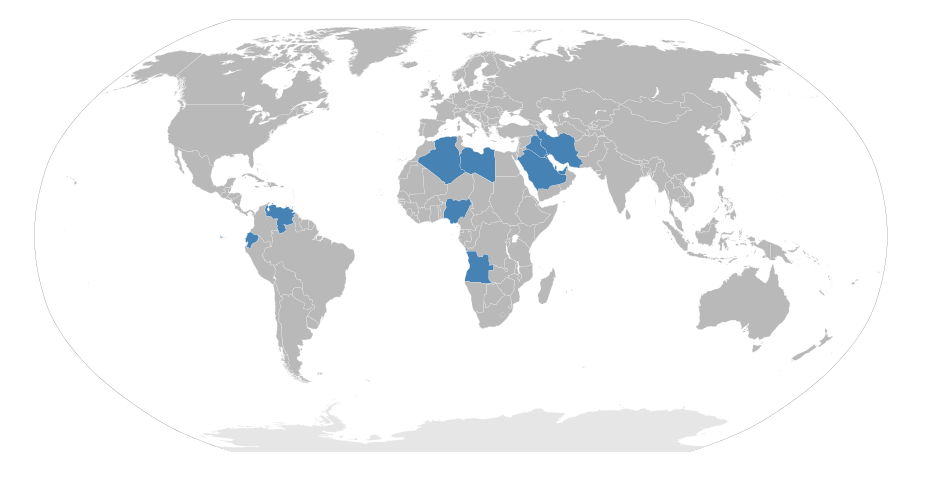

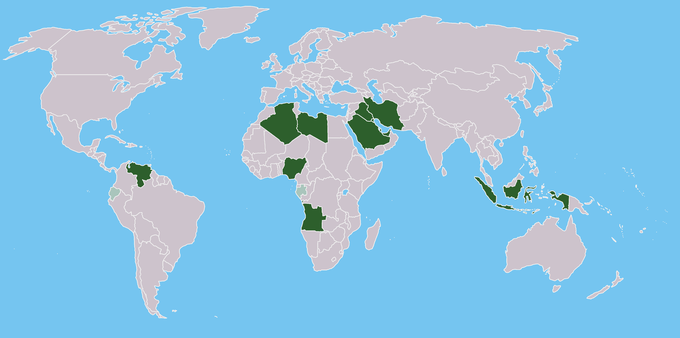

Perhaps the easiest approach for colluding oligopolists, as you might imagine, would be to sign a contract with each other that they will hold output low and keep prices high. If a group of U.S. companies signed such a contract, however, it would be illegal. Certain international organizations, like the nations that are members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) , have signed international agreements to act like a monopoly, hold down output, and keep prices high so that all of the countries can make high profits from oil exports. Such agreements, however, because they fall in a gray area of international law, are not legally enforceable. If Nigeria, for example, decides to start cutting prices and selling more oil, Saudi Arabia cannot sue Nigeria in court and force it to stop.

Visit the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries website and learn more about its history and how it defines itself.

Because oligopolists cannot sign a legally enforceable contract to act like a monopoly, the firms may instead keep close tabs on what other firms are producing and charging. Alternatively, oligopolists may choose to act in a way that generates pressure on each firm to stick to its agreed quantity of output.

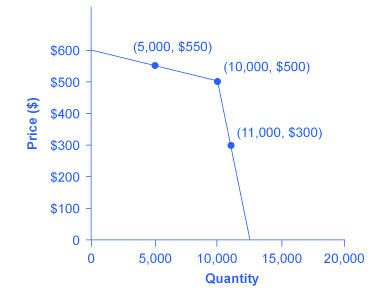

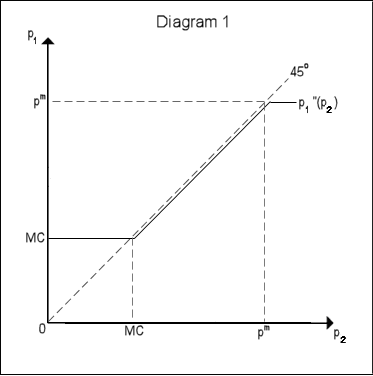

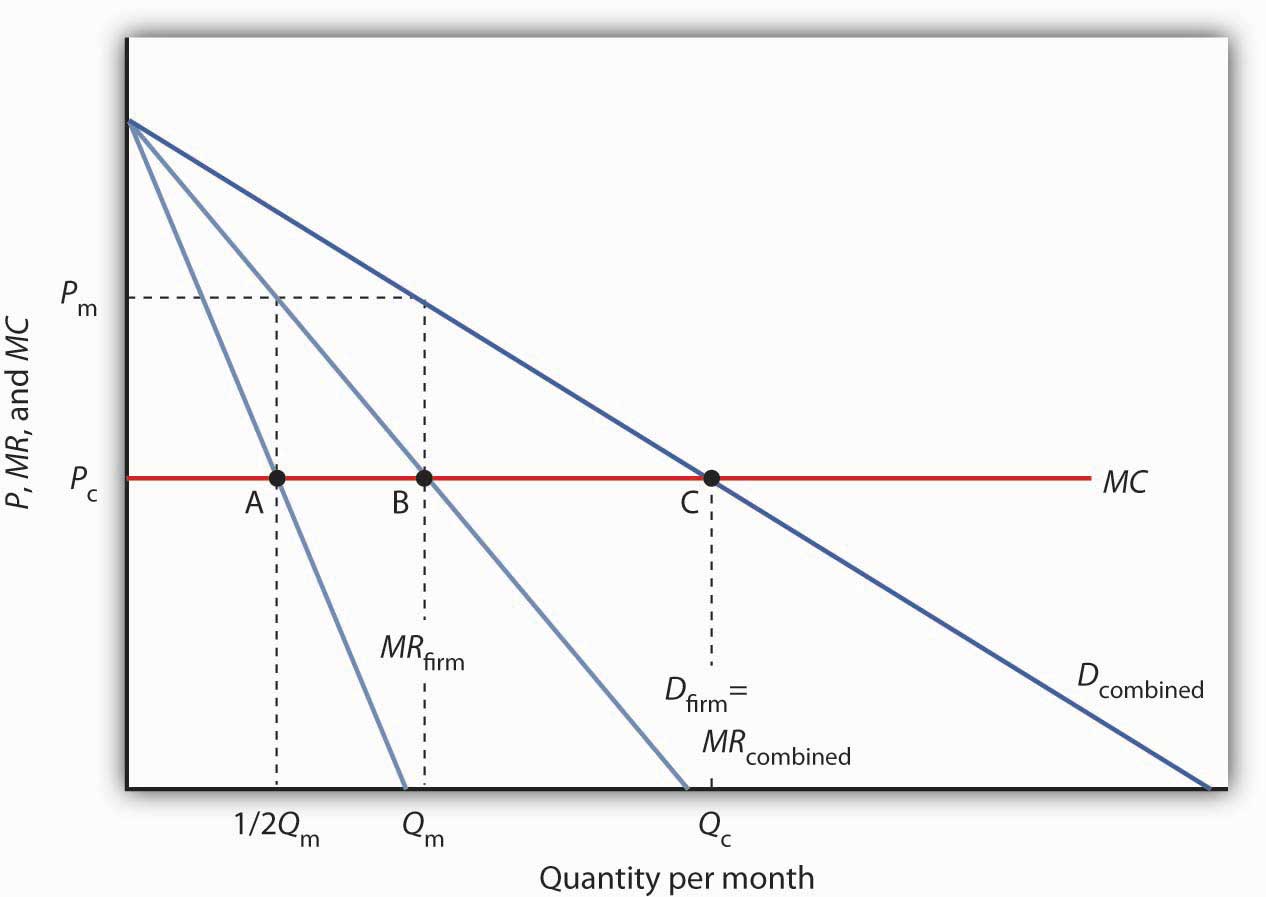

One example of the pressure these firms can exert on one another is the kinked demand curve , in which competing oligopoly firms commit to match price cuts, but not price increases. This situation is shown in Figure 1 . Say that an oligopoly airline has agreed with the rest of a cartel to provide a quantity of 10,000 seats on the New York to Los Angeles route, at a price of $500. This choice defines the kink in the firm’s perceived demand curve. The reason that the firm faces a kink in its demand curve is because of how the other oligopolists react to changes in the firm’s price. If the oligopoly decides to produce more and cut its price, the other members of the cartel will immediately match any price cuts—and therefore, a lower price brings very little increase in quantity sold.

If one firm cuts its price to $300, it will be able to sell only 11,000 seats. However, if the airline seeks to raise prices, the other oligopolists will not raise their prices, and so the firm that raised prices will lose a considerable share of sales. For example, if the firm raises its price to $550, its sales drop to 5,000 seats sold. Thus, if oligopolists always match price cuts by other firms in the cartel, but do not match price increases, then none of the oligopolists will have a strong incentive to change prices, since the potential gains are minimal. This strategy can work like a silent form of cooperation, in which the cartel successfully manages to hold down output, increase price , and share a monopoly level of profits even without any legally enforceable agreement.

Many real-world oligopolies, prodded by economic changes, legal and political pressures, and the egos of their top executives, go through episodes of cooperation and competition. If oligopolies could sustain cooperation with each other on output and pricing, they could earn profits as if they were a single monopoly. However, each firm in an oligopoly has an incentive to produce more and grab a bigger share of the overall market; when firms start behaving in this way, the market outcome in terms of prices and quantity can be similar to that of a highly competitive market.

Tradeoffs of Imperfect Competition

Monopolistic competition is probably the single most common market structure in the U.S. economy. It provides powerful incentives for innovation, as firms seek to earn profits in the short run, while entry assures that firms do not earn economic profits in the long run. However, monopolistically competitive firms do not produce at the lowest point on their average cost curves. In addition, the endless search to impress consumers through product differentiation may lead to excessive social expenses on advertising and marketing.

Oligopoly is probably the second most common market structure. When oligopolies result from patented innovations or from taking advantage of economies of scale to produce at low average cost, they may provide considerable benefit to consumers. Oligopolies are often buffeted by significant barriers to entry, which enable the oligopolists to earn sustained profits over long periods of time. Oligopolists also do not typically produce at the minimum of their average cost curves. When they lack vibrant competition, they may lack incentives to provide innovative products and high-quality service.

The task of public policy with regard to competition is to sort through these multiple realities, attempting to encourage behavior that is beneficial to the broader society and to discourage behavior that only adds to the profits of a few large companies, with no corresponding benefit to consumers. Monopoly and Antitrust Policy discusses the delicate judgments that go into this task.

The Temptation to Defy the Law

Oligopolistic firms have been called “cats in a bag,” as this chapter mentioned. The French detergent makers chose to “cozy up” with each other. The result? An uneasy and tenuous relationship. When the Wall Street Journal reported on the matter, it wrote: “According to a statement a Henkel manager made to the [French anti-trust] commission, the detergent makers wanted ‘to limit the intensity of the competition between them and clean up the market.’ Nevertheless, by the early 1990s, a price war had broken out among them.” During the soap executives’ meetings, which sometimes lasted more than four hours, complex pricing structures were established. “One [soap] executive recalled ‘chaotic’ meetings as each side tried to work out how the other had bent the rules.” Like many cartels, the soap cartel disintegrated due to the very strong temptation for each member to maximize its own individual profits.

How did this soap opera end? After an investigation, French antitrust authorities fined Colgate-Palmolive, Henkel, and Proctor & Gamble a total of €361 million ($484 million). A similar fate befell the icemakers. Bagged ice is a commodity, a perfect substitute, generally sold in 7- or 22-pound bags. No one cares what label is on the bag. By agreeing to carve up the ice market, control broad geographic swaths of territory, and set prices, the icemakers moved from perfect competition to a monopoly model. After the agreements, each firm was the sole supplier of bagged ice to a region; there were profits in both the long run and the short run. According to the courts: “These companies illegally conspired to manipulate the marketplace.” Fines totaled about $600,000—a steep fine considering a bag of ice sells for under $3 in most parts of the United States.

Even though it is illegal in many parts of the world for firms to set prices and carve up a market, the temptation to earn higher profits makes it extremely tempting to defy the law.

Key Concepts and Summary

An oligopoly is a situation where a few firms sell most or all of the goods in a market. Oligopolists earn their highest profits if they can band together as a cartel and act like a monopolist by reducing output and raising price. Since each member of the oligopoly can benefit individually from expanding output, such collusion often breaks down—especially since explicit collusion is illegal.

The prisoner’s dilemma is an example of game theory. It shows how, in certain situations, all sides can benefit from cooperative behavior rather than self-interested behavior. However, the challenge for the parties is to find ways to encourage cooperative behavior.

Self-Check Questions

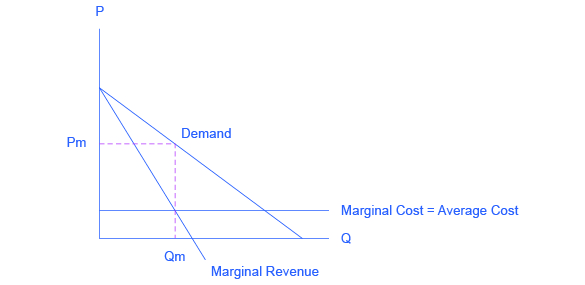

- Suppose the firms collude to form a cartel. What price will the cartel charge? What quantity will the cartel supply? How much profit will the cartel earn?

- Suppose now that the cartel breaks up and the oligopolistic firms compete as vigorously as possible by cutting the price and increasing sales. What will the industry quantity and price be? What will the collective profits be of all firms in the industry?

- Compare the equilibrium price, quantity, and profit for the cartel and cutthroat competition outcomes.

Review Questions

- Will the firms in an oligopoly act more like a monopoly or more like competitors? Briefly explain.

- Does each individual in a prisoner’s dilemma benefit more from cooperation or from pursuing self-interest? Explain briefly.

- What stops oligopolists from acting together as a monopolist and earning the highest possible level of profits?

Critical Thinking Questions

- Would you expect the kinked demand curve to be more extreme (like a right angle) or less extreme (like a normal demand curve) if each firm in the cartel produces a near-identical product like OPEC and petroleum? What if each firm produces a somewhat different product? Explain your reasoning.

- When OPEC raised the price of oil dramatically in the mid-1970s, experts said it was unlikely that the cartel could stay together over the long term—that the incentives for individual members to cheat would become too strong. More than forty years later, OPEC still exists. Why do you think OPEC has been able to beat the odds and continue to collude? Hint: You may wish to consider non-economic reasons.

- Mary and Raj are the only two growers who provide organically grown corn to a local grocery store. They know that if they cooperated and produced less corn, they could raise the price of the corn. If they work independently, they will each earn $100. If they decide to work together and both lower their output, they can each earn $150. If one person lowers output and the other does not, the person who lowers output will earn $0 and the other person will capture the entire market and will earn $200. Table 6 represents the choices available to Mary and Raj. What is the best choice for Raj if he is sure that Mary will cooperate? If Mary thinks Raj will cheat, what should Mary do and why? What is the prisoner’s dilemma result? What is the preferred choice if they could ensure cooperation? A = Work independently; B = Cooperate and Lower Output. (Each results entry lists Raj’s earnings first, and Mary’s earnings second.)

The United States Department of Justice. “Antitrust Division.” Accessed October 17, 2013. http://www.justice.gov/atr/.

eMarketer.com. 2014. “Total US Ad Spending to See Largest Increase Since 2004: Mobile advertising leads growth; will surpass radio, magazines and newspapers this year. Accessed March 12, 2015. http://www.emarketer.com/Article/Total-US-Ad-Spending-See-Largest-Increase-Since-2004/1010982.

Federal Trade Commission. “About the Federal Trade Commission.” Accessed October 17, 2013. http://www.ftc.gov/ftc/about.shtm.

Answers to Self-Check Questions

- Pc > Pcc. Qc < Qcc. Profit for the cartel is positive and large. Profit for cutthroat competition is zero.

- Firm B reasons that if it cheats and Firm A does not notice, it will double its money. Since Firm A’s profits will decline substantially, however, it is likely that Firm A will notice and if so, Firm A will cheat also, with the result that Firm B will lose 90% of what it gained by cheating. Firm A will reason that Firm B is unlikely to risk cheating. If neither firm cheats, Firm A earns $1000. If Firm A cheats, assuming Firm B does not cheat, A can boost its profits only a little, since Firm B is so small. If both firms cheat, then Firm A loses at least 50% of what it could have earned. The possibility of a small gain ($50) is probably not enough to induce Firm A to cheat, so in this case it is likely that both firms will collude.

Principles of Economics Copyright © 2016 by Rice University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

18 Models of Oligopoly: Cournot, Bertrand, and Stackelberg

Cournot, Bertrand, and Stackelberg

The Policy Question How Should the Government Have Responded to Big Oil Company Mergers?

Exploring the policy question.

- How do oil companies compete—on quantities or prices?

- What policy solutions present themselves from this analysis?

Learning Objectives

18.1 cournot model of oligopoly: quantity setters.

Learning Objective 18.1 : Describe how oligopolist firms that choose quantities can be modeled using game theory.

18.2 Bertrand Model of Oligopoly: Price Setters

Learning Objective 18.2 : Describe how oligopolist firms that choose prices can be modeled using game theory.

18.3 Stackelberg Model of Oligopoly: First-Mover Advantage

Learning Objective 18.3 : Describe the different outcomes when oligopolist firms choose quantities sequentially.

18.4 Policy Example How Should the Government Have Responded to Big Oil Company Mergers?

Learning Objective 18.4 : Explain how models of oligopoly can help us understand how to respond to proposed mergers of oil companies that sell retail gas.

Oligopoly markets are markets in which only a few firms compete, where firms produce homogeneous or differentiated products, and where barriers to entry exist that may be natural or constructed. There are three main models of oligopoly markets, and each is considered a slightly different competitive environment. The Cournot model considers firms that make an identical product and make output decisions simultaneously. The Bertrand model considers firms that make an identical product but compete on price and make their pricing decisions simultaneously. The Stackelberg model considers quantity-setting firms with an identical product that make output decisions simultaneously. This chapter considers all three in order, beginning with the Cournot model.

Oligopolists face downward-sloping demand curves, which means that price is a function of the total quantity produced, which, in turn, implies that one firm’s output affects not only the price it receives for its output but the price its competitors receive as well. This creates a strategic environment where one firm’s profit maximizing output level is a function of its competitors’ output levels. The model we use to analyze this is one first introduced by French economist and mathematician Antoine Augustin Cournot in 1838. Interestingly, the solution to the Cournot model is the same as the more general Nash equilibrium concept introduced by John Nash in 1949 and the one used to solve for equilibrium in non-cooperative games in chapter 17 .

We will start by considering the simplest situation: two companies that make an identical product and that have the same cost function. Later we will explore what happens when we relax those assumptions and allow more firms, differentiated products, and different cost functions.

Let’s begin by considering a situation where there are two oil refineries located in the Denver, Colorado, area that are the only two providers of gasoline for the Rocky Mountain regional wholesale market. We’ll call them Federal Gas and National Gas. The gas they produce is identical, and they each decide independently—and without knowing the other’s choice—the quantity of gas to produce for the week at the beginning of each week. We will call Federal’s output choice [latex]q_F[/latex] and National’s output choice [latex]q_N[/latex], where [latex]q[/latex] represents liters of gasoline. The weekly demand for wholesale gas in the Rocky Mountain region is [latex]P=A—BQ[/latex], where [latex]Q[/latex] is the total quantity of gas supplied by the two firms, or [latex]Q=q_F+q_N[/latex]. Immediately, you can see the strategic component: the price they both receive for their gas is a function of each company’s output. We will assume that each liter of gas produced costs the company c, or that c is the marginal cost of producing a liter of gas for both companies and that there are no fixed costs.

If the profit function is [latex]\pi_F[/latex][latex]=[/latex] [latex]q_F(A-B(q_F+q_N)-c)[/latex] , then we can find the optimal output level by solving for the stationary point, or solving

[latex]\frac{\partial \pi_F}{\partial q_F}[/latex] [latex]=[/latex] [latex]_0[/latex]

If [latex]\pi_F=[/latex] [latex]q_F(A-B(q_F+q_N)-c)[/latex] , then we can expand to find

[latex]\pi_F[/latex] [latex]=[/latex][latex]Aq_F-Bq[/latex] [latex]\frac{F}{2}[/latex] [latex]-Bq_Fq_N-cq_F[/latex]

Taking the partial derivative of this expression with respect to [latex]q_F[/latex] ,

[latex]\frac{\partial \pi_F}{\partial q_F}[/latex] [latex]=[/latex][latex]A-2Bq_F-Bq_N-c[/latex] [latex]=[/latex] [latex]_0[/latex]

If we rearrange this, we can see that this is simply an expression of [latex]MR=MC[/latex] .

[latex]A-2Bq_F-Bq_N[/latex][latex]=[/latex][latex]c[/latex]

The marginal revenue looks the same as a monopolist’s [latex]MR[/latex] function but with one additional term, [latex]-[/latex] [latex]Bq_N[/latex] .

Solving for [latex]q_F[/latex] yields

[latex]q_F=[/latex] [latex]\frac{A-Bq_N-c}{2B}[/latex] ,

[latex]q^*_F=[/latex] [latex]\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{1}{2}[/latex] [latex]qN[/latex]

This is Federal Gas’s best response function, their profit maximizing output level given the output choice of their rivals. It is the same best response function as the ones in chapter 17 . By symmetry, National Gas has an identical best response function:

[latex]q^*_N=[/latex] [latex]\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{1}{2}[/latex] [latex]qF[/latex]

With these assumptions in place, we can express Federal’s profit function:

[latex]\pi_F=P \times q_F—c \times q_F = q_F (P-c)[/latex]

Substituting the inverse demand curve, we arrive at the expression

[latex]\pi_F=q_F(A-BQ-c)[/latex].

Substituting [latex]Q=q_A+q_B[/latex] yields

[latex]\pi_F=q_F(A-B(q_F+q_N)-c)[/latex].

The expression for National is symmetric:

[latex]\pi_N=q_N(A-B(q_N+q_F)-c)[/latex]

Note that we have now described a game complete with players, Federal and National; strategies, [latex]q_F[/latex] and [latex]q_N[/latex]; and payoffs, [latex]\pi_F[/latex] and [latex]\pi_N[/latex]. Now the task is to search for the equilibrium of the game. To do so, we have to begin with a best response function. In this case, the best response is the firm’s profit maximizing output. This will depend on both the firm’s own output and the competing firm’s output.

We know from chapter 15 that the monopolists’ marginal revenue curve when facing an inverse demand curve [latex]P=A-BQ[/latex] is [latex]MR(q)=A-2Bq[/latex]. This duopolistic example shows that the firms’ marginal revenue curves include one extra term:

[latex]MR_F(q_F)=A-2Bq_F-Bq_N[/latex] and [latex]MR_N(q_N)=A-2Bq_N-Bq_F[/latex]

The profit maximizing rule tells us that to find the profit maximizing output, we must set the marginal revenue to the marginal cost and solve. Doing so yields

[latex]q^*_F=\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{1}{2}qN[/latex]

for Federal Gas and

[latex]q^*_N=\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{1}{2}qF[/latex]

for National Gas. These are the firms’ best response functions, their profit maximizing output levels given the output choice of their rivals.

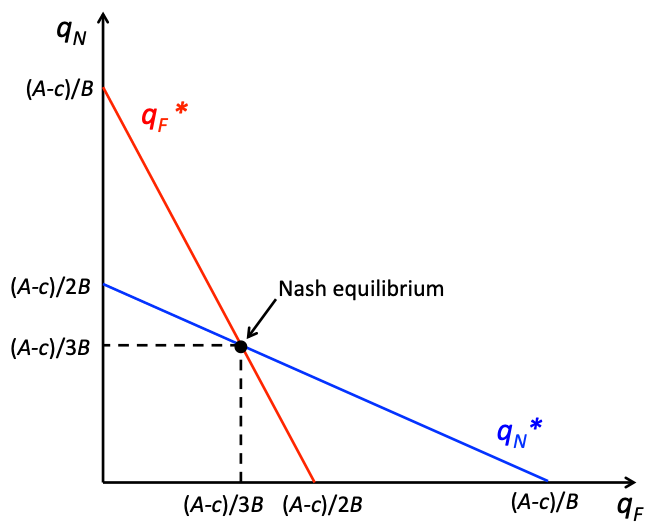

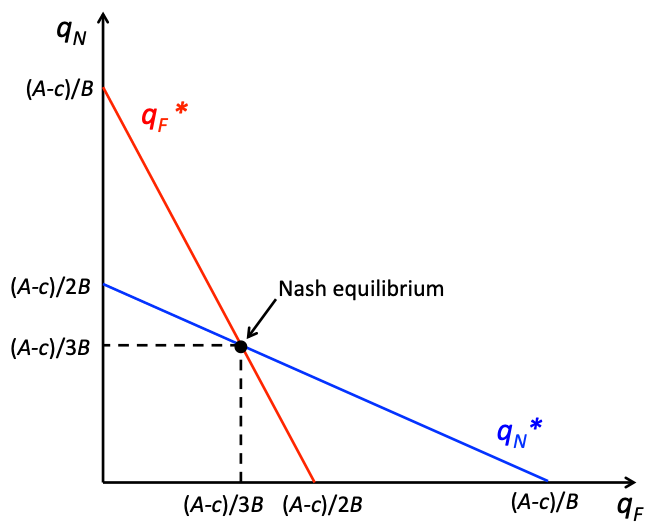

Now that we know the best response functions, solving for equilibrium in the model is relatively straightforward. We can begin by graphing the best response functions. These graphical illustrations of the best response functions are called reaction curves. A Nash equilibrium is a correspondence of best response functions, which is the same as a crossing of the reaction curves.

In figure 18.1 , we can see the Nash equilibrium of the Cournot duopoly model as the intersection of the reaction curves. Mathematically, this intersection is found by simultaneously solving

[latex]q^*_F=\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{1}{2}q_N[/latex] and [latex]q^*_F=\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{1}{2}q_F[/latex]

This is a system of two equations and two unknowns and therefore has a unique solution as long as the slopes are not equal. We can solve these by substituting one equation into the other, which yields a single equation with a single unknown:

[latex]q^*_F=\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{1}{2}[\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{1}{2}q_F][/latex]

Solving this by steps results in the following:

[latex]q^*_F=\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{A-c}{4B}+\frac{1}{4}q_F[/latex][latex]\frac{3}{4}q^*_F=\frac{A-c}{4B}[/latex] [latex]q^*_F=\frac{A-c}{3B}[/latex]

And by symmetry, we know that the two optimal quantities are the same:

[latex]q^*_N=\frac{A-c}{3B}[/latex]

The Nash equilibrium is

[latex](q^*_F,q^*_N)[/latex]

[latex](\frac{A-c}{3B}, \frac{A-c}{3B})[/latex].

Let’s consider a specific example. Suppose in the above example, the weekly demand curve for wholesale gas in the Rocky Mountain region is

[latex]p = 1,000 − 2Q[/latex], in thousands of gallons

Both firms have constant marginal costs of 400. In this case,

[latex]A = 1,000[/latex], [latex]B = 2[/latex] and [latex]C = 400[/latex].

[latex]q^*_F=\frac{A-c}{3B}=\frac{1,000 − 400}{(3)(2)}=\frac{600}{6}=100[/latex]

By symmetry, we know

[latex]q^*_N=100[/latex]

as well. So both Federal Gas and National Gas produce 100,000 gallons of gasoline a week. Total output is the sum of the two and is 200,000 gallons. The price is [latex]p= 1,000 − 2(200) = $600[/latex] for 1,000 gallons of gas, or $0.60 a gallon.

To analyze this from the beginning, we can set up the total revenue function for Federal Gas:

[latex]TR(q_F)=p×q_F[/latex] [latex]=(1,000 − 2Q)q_F[/latex] [latex]=(1,000 − 2q_F-2q_N)q_F[/latex] [latex]= 1,000 − 2q \frac{2}{F}-2q_Fq_N[/latex]

The marginal revenue function that is associated with this is

[latex]MR(q_F)=1,000 − 4q_F-2q_N[/latex].

We know marginal cost is 400, so setting marginal revenue equal to marginal cost results in the following expression:

[latex]1,000 − 4q_F-2q_N=400[/latex]

Solving for [latex]q_F[/latex] results in the following:

[latex]q_F=\frac{600 − 2q_N}{4}[/latex] [latex]q^*_F=150-\frac{q_F}{2}[/latex]

This is the best response function for Federal Gas. By symmetry, we know that National Gas has the same best response function:

[latex]q^*_N=150-\frac{q_F}{2}[/latex]

Solving for the Nash equilibrium, we get the following:

[latex]q^*_N=150-\frac{q_F}{2}[/latex] [latex]q^*_F=150 − 75+\frac{q_F}{4}[/latex] [latex]/frac{3}{4}q^*_F=25[/latex] [latex]q^*_F=100[/latex]

We can insert the solution for [latex]q_F[/latex] into [latex]q^*_N[/latex]:

[latex]q^*_N=150-\frac{(100)}{2}=100[/latex]

In the previous section, we studied oligopolists that make an identical good and who compete by setting quantities. The example we used in that section was wholesale gasoline, where the market sets a price that equates supply and demand and the strategic decision of the refiners was how much oil to refine into gasoline. In this section, we turn our attention to a different situation in which the oligopolists compete on price. The example here is the retail gas stations that bought the wholesale gas from the refiners and are now ready to sell it to consumers. We still have identical goods; for consumers, the gas that goes into their cars is all the same, and we will assume away any other differences like cleaner stations or the presence of a mini-mart.

Let’s imagine a simple situation where there are two gas stations, Fast Gas and Speedy Gas, on either side of a busy main street. Both stations have large signs that display the gas prices that each station is offering for the day. Consumers are assumed to be indifferent about the gas or the stations, so they will go to the station that is offering the lower price. So an individual gas station’s demand is conditional on its relative price with the other station.

Formally, we can express this with the following demand function for Fast Gas:

[latex]Q_F \left\{\begin{matrix} & & & \\ a-bP_F \text{ if }P_F P_F \end{matrix}\right.[/latex]

Speedy Gas has an equivalent demand curve:

[latex]Q_S \left\{\begin{matrix} & & & \\ a-bP_S \text{ if }P_S P_F \end{matrix}\right.[/latex]

In other words, these demand curves say that if a station has a lower price than the other, they will get all the demand at that price, and the other station will get no demand. If they have the same price, then each will get one-half of the demand at that price.

Let’s assume that Fast Gas and Speedy Gas both have the same constant marginal cost of [latex]c[/latex] and no fixed costs to keep the analysis simple. The question we now have to answer is, What are the best response functions for the two stations? Remember that best response functions are one player’s optimal strategy choice given the strategy choice of the other player. So what is Fast Gas’s best response to Speedy Gas’s price?

If Speedy Gas charges

[latex]P_S \gt c[/latex]

Fast Gas can set [latex]P_F \gt P_S[/latex] and they will get no customers at all and make a profit of zero. Fast Gas could instead set

[latex]P_F=P_S[/latex]

and get [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] the demand at that price and make a positive profit. Or they could set

[latex]P_F=P_S −$0.01[/latex]

or set their price one cent below Speedy Gas’s price and get all the customers at a price that is one cent below the price, at which they would get [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] the demand.

Clearly, this third option is the one that yields the most profit. Now we just have to consider the case where [latex]P_S=c[/latex]. In this case, undercutting the price by one cent is not optimal because Fast Gas would get all the demand but would lose money on every gallon of gas sold, yielding negative profits. Setting

[latex]P_F=P_S=c[/latex]

would give them half the demand at a break-even price and would yield exactly zero profits.

The best response function we just described for Fast Gas is the same best response function for Speedy Gas. So where are the correspondences of best response functions? As long as the prices are above [latex]c[/latex], there is always an incentive for both stations to undercut each other’s price, so there is no equilibrium. But at [latex]P_F=P_S=c[/latex], both stations are playing their best response to each other simultaneously. So the unique Nash equilibrium to this game is

[latex]P_F=P_S=c[/latex].

What is particularly interesting about this is the fact that this is the same outcome that would have occurred if they were in a perfectly competitive market because competition would have driven prices down to marginal cost. So in a situation where competition is based on price and the good is relatively homogeneous, as few as two firms can drive the market to an efficient outcome.

Both the Cournot model and the Bertrand model assume simultaneous move games. This makes sense when one firm has to make a strategic decision before knowing about the strategy choice of the other firm. But not all situations are like this. What happens when one firm makes its strategic decision first and the other firm chooses second? This is the situation described by the Stackelberg model, where the firms are quantity setters selling homogenous goods.

Let’s return to the example of two oil companies: Federal Gas and National Gas. The gas they produce is identical, but now they decide their output levels sequentially. We will assume that Federal Gas sets its output first, and then after observing Federal’s choice, National Gas decides on the quantity of gas they are going to produce for the week. We will again call Federal’s output choice [latex]q_F[/latex] and National’s output choice [latex]q_N[/latex], where [latex]q[/latex] represents liters of gasoline. The weekly demand for wholesale gas is still [latex]P = A—BQ[/latex], where [latex]Q[/latex] is the total quantity of gas supplied by the two firms, or

[latex]Q=q_F+q_N[/latex].

We have now turned the previous Cournot game into a sequential game, and the [latex]SPNE[/latex] solution to a sequential game is found through backward induction. So we have to start at the second move of the game: National’s output choice. When National makes this decision, Federal’s output choices are already made and known to National, so it is taken as given. Therefore, we can express Federal’s profit function as

[latex]\Pi _N=q_N(A-B(q_N+q_F)-c)[/latex].

This is the same as in the Cournot example, and for National, the best response function is also the same. This is because in the Cournot case, both firms took the other’s output as given.

[latex]q^*_N=\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{1}{2}q_F[/latex]

When it comes to Federal’s decision, we diverge from the Cournot model because instead of taking [latex]q_N[/latex] as a given, Federal knows exactly how National will respond because they know the best response function. Federal’s profit function,

[latex]\Pi _F=q_F(A-Bq_F-Bq_N-c)[/latex],

can be re-written, replacing [latex]q_N[/latex] with the best response function:

[latex]\Pi _F=q_F(A-Bq_F-B(\frac{A-C}{2B}-\frac{1}{2})-c)[/latex]

If the profit function is [latex]\Pi_F[/latex] [latex]=[/latex] [latex]q_F([/latex] [latex]\frac{A-C}{2}-[/latex] [latex]B[/latex] [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] [latex]q_F)[/latex] , then we can find the optimal output level by solving for the stationary point, or solving

[latex]\frac{\partial \Pi _F}{\partial q_F}[/latex] [latex]=[/latex] [latex]_0[/latex]

If [latex]\Pi_F[/latex] [latex]=[/latex] [latex]q_F([/latex] [latex]\frac{A-c}{2}-[/latex] [latex]B[/latex] [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] [latex]q_F)[/latex] , then we can expand to find

[latex]\Pi_F[/latex] [latex]=[/latex] [latex]q_F([/latex] [latex]\frac{A-c}{2}[/latex] [latex])q_F[/latex] [latex]-B[/latex] [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] [latex]q_{F}^{2}[/latex]

Taking the partial derivative of this expression with respect to [latex]q_F[/latex], we get

[latex]\frac{\partial \Pi _F}{\partial q_F}[/latex] [latex]=([/latex] [latex]\frac{A-c}{2}[/latex] [latex])[/latex][latex]-[/latex] [latex]Bq_F=[/latex] [latex]_0[/latex]

[latex]q_F=[/latex] [latex]\frac{A-c}{2B}[/latex]

This is Federal Gas’s profit maximizing output level, given that they choose first and can anticipate National’s response.

We can see that Federal’s profits are determined only by their own output once we explicitly consider National’s response. Simplifying yields

[latex]\Pi _F=q_F(\frac{A-c}{2}-B\frac{1}{2}q_F)[/latex].

We know that the second mover’s best response is the same as in section 18.1 , and the solution to the profit optimization problem above yields the following best response function for Federal Gas:

[latex]q^*_F=\frac{A-c}{2B}[/latex],

substituting this into National’s best response function and solving the following:

[latex]q^*_N=\frac{A-c}{2B}-\frac{1}{2}\left [ \frac{A-c}{2B} \right ][/latex]

[latex]q^*_N=\frac{A-c}{2B}-\left [\frac{A-c}{4B} \right][/latex]

[latex]q^*_N=\frac{A-c}{4B}[/latex]

The subgame perfect Nash equilibrium is

([latex]q^*_F[/latex], [latex]q^*_F[/latex])

A few things are worth noting when comparing this outcome to the Nash equilibrium outcome of the Cournot game in section 18.1 . First, the individual output level for Federal, the first mover in the Stackelberg game, the Stackelberg leader , is higher than it is in the Cournot game. Second, the individual output level for National, the second mover in the Stackelberg game, the Stackelberg follower , is lower than it is in the Cournot game. Third, the total output is larger in the Stackelberg outcome than in the Cournot outcome. This means the price is lower because the demand curve is downward sloping. Since the Cournot outcome is one of the options for the Stackelberg leader—if it chooses the same output as in the Cournot case, the follower will as well—it must be true that profits are higher for the Stackelberg leader. And since both the quantity produced and the price received are lower for the Stackelberg follower compared to the Cournot outcome, the profits must be lower as well.

So from this we see the major differences in the Stackelberg model compared to the Cournot model. There is a considerable first-mover advantage . By being able to set its quantity first, Federal Gas is able to gain a larger share of the market for itself, and even though it leads to a lower price, it makes up for that lower price with the increase in quantity to achieve higher profits. The opposite is true for the second mover: by being forced to choose after the leader has set its output, the follower is forced to accept a lower price and lower output. From the consumer’s perspective, the Stackelberg outcome is preferable because overall, there is more quantity at a lower price.

The end of the twentieth century saw a number of mergers of massive oil companies. In 1999, BP Amoco acquired ARCO, followed soon thereafter by Exxon’s acquisition of Mobil. Then, in 2001, Chevron acquired Texaco for $38.7 billion. The newly combined company became the world’s fourth-largest producer of oil and natural gas. Whenever any such mergers and acquisitions are proposed, the US government has to approve the deal, and sometimes this approval comes with conditions designed to protect US consumers from undue harm that the consolidation might cause due to market concentration. In this case, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) was the agency that provided oversight, and in the end, they approved the merger with the following condition: they had to sell their stake in two massive oil refineries. However, they were largely allowed to retain their retail gas operations, even though both companies had significant market presence and their merger would cause a drop in the competitiveness of the retail gas market, particularly in some areas where both companies had a significant market share.

On their face, these decisions seem to make little sense. How is it that the US government is worried about the impact of the merger on refining and the wholesale gas market but not on the retail gas market? The answer lies in the way these two markets fit into the economic models of oligopoly. Refining and wholesale gas operations are more akin to the Cournot model, where a few firms produce a homogenous product and compete on quantity and the sum total of all gas refined sets the wholesale market price. The insight of the Cournot model is that every merger produces fewer firms, and this constrains supply and increases price. Remember that this is a function not of capacity—that has not changed—but of the strategic environment, which makes it easier for all firms to constrict supply, which, in turn, raises prices and profits. The lower supply and higher prices do material harm to consumers, however, and it is for this reason that the FTC stepped in and demanded that the merged company sell off its interest in two big refining operations.

On the other hand, retail gas is more akin to the Bertrand model, where a bunch of retailers are selling a homogenous good but are competing mostly on price. A cursory examination of the retail gas industry confirms this: prices are posted prominently, and consumers show very strong responses to lower prices. The Bertrand model shows us that it takes very little competition to result in highly competitive pricing, so a merger that might reduce the number of competing gas station brands by one is unlikely to have much of a material effect on prices and therefore will be unlikely to harm consumers.

Viewed through the lens of the models of oligopoly studied in this chapter, the FTC’s decision to demand a divestment in oil refining and wholesale gas operations but mostly allow the retail side to consolidate makes sense. It is no surprise that these are the very same models the government uses to analyze such situations and devise a response.

- Do you think it is correct that wholesale gas looks more like the Cournot model and retail gas looks more like the Bertrand model?

- Do you think the government did the right thing in the case of the Chevron-Texaco merger?

Review: Topics and Related Learning Outcomes

Learn: key topics.

Oligopoly markets are markets in which only a few firms compete, where firms produce homogeneous or differentiated products, and where barriers to entry exist that may be natural or constructed.

The Cournot model considers firms that make an identical product and make output decisions simultaneously.

The Bertrand model considers firms that make an identical product but compete on price and make their pricing decisions simultaneously.

The Stackelberg model considers quantity-setting firms with an identical product that make output decisions simultaneously.

Tables and Graphs

Media Attributions

- 18.1.1 © Patrick M. Emerson is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

Intermediate Microeconomics Copyright © 2019 by Patrick M. Emerson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

13.2: Oligopoly in Practice

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 3513

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Collusion and Competition

Firms in an oligopoly can increase their profits through collusion, but collusive arrangements are inherently unstable.

learning objectives

- Assess the considerations involved in the oligopolist’s decision about whether to compete or cooperate

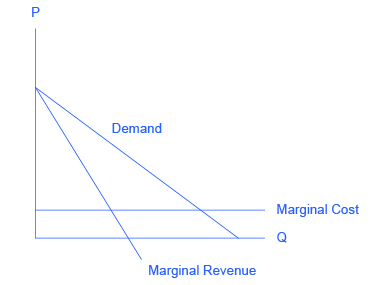

Oligopoly is a market structure in which there are a few firms producing a product. When there are few firms in the market, they may collude to set a price or output level for the market in order to maximize industry profits. As a result, price will be higher than the market-clearing price, and output is likely to be lower. At the extreme, the colluding firms may act as a monopoly, reducing their individual output so that their collective output would equal that of a monopolist, allowing them to earn higher profits.

OPEC : The oil-producing countries of OPEC have at times cooperated to raise world oil prices in order to secure a steady income for themselves.

If oligopolists individually pursued their own self-interest, then they would produce a total quantity greater than the monopoly quantity, and charge a lower price than the monopoly price, thus earning a smaller profit. The promise of bigger profits gives oligopolists an incentive to cooperate. However, collusive oligopoly is inherently unstable, because the most efficient firms will be tempted to break ranks by cutting prices in order to increase market share.

Several factors deter collusion. First, price-fixing is illegal in the United States, and antitrust laws exist to prevent collusion between firms. Second, coordination among firms is difficult, and becomes more so the greater the number of firms involved. Third, there is a threat of defection. A firm may agree to collude and then break the agreement, undercutting the profits of the firms still holding to the agreement. Finally, a firm may be discouraged from collusion if it does not perceive itself to be able to effectively punish firms that may break the agreement.

In contrast to price-fixing, price leadership is a type of informal collusion which is generally legal. Price leadership, which is also sometimes called parallel pricing, occurs when the dominant competitor publishes its price ahead of other firms in the market, and the other firms then match the announced price. The leader will typically set the price to maximize its profits, which may not be the price that maximized other firms’ profits.

Game Theory Applications to Oligopoly

Game theory provides a framework for understanding how firms behave in an oligopoly.

- Explain how game theory applies to oligopolies

In an oligopoly, firms are interdependent; they are affected not only by their own decisions regarding how much to produce, but by the decisions of other firms in the market as well. Game theory offers a useful framework for thinking about how firms may act in the context of this interdependence. More specifically, game theory can be used to model situations in which each actor, when deciding on a course of action, must also consider how others might respond to that action.

For example, game theory can explain why oligopolies have trouble maintaining collusive arrangements to generate monopoly profits. While firms would be better off collectively if they cooperate, each individual firm has a strong incentive to cheat and undercut their competitors in order to increase market share. Because the incentive to defect is strong, firms may not even enter into a collusive agreement if they don’t perceive there to be a way to effectively punish defectors.

The prisoner’s dilemma is a specific type of game in game theory that illustrates why cooperation may be difficult to maintain for oligopolists even when it is mutually beneficial. In the game, two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. The prisoners are separated and left to contemplate their options. If both prisoners confess, each will serve a two-year prison term. If one confesses, but the other denies the crime, the one that confessed will walk free, while the one that denied the crime would get a three-year sentence. If both deny the crime, they will both serve only a one year sentence. Betraying the partner by confessing is the dominant strategy; it is the better strategy for each player regardless of how the other plays. This is known as a Nash equilibrium. The result of the game is that both prisoners pursue individual logic and betray, when they would have collectively gotten a better outcome if they had both cooperated.

Prisoner’s Dilemma : In a prisoner’s dilemma game, the dominant strategy for each player is to betray the other, even though cooperation would have led to a better collective outcome.

The Nash equilibrium is an important concept in game theory. It is the set of strategies such that no player can do better by unilaterally changing his or her strategy. If a player knew the strategies of the other players (and those strategies could not change), and could not benefit by changing his or her strategy, then that set of strategies represents a Nash equilibrium. If any player would benefit by changing his or her strategy, then that set of strategies is not a Nash equilibrium.

While game theory is important to understanding firm behavior in oligopolies, it is generally not needed to understand competitive or monopolized markets. In competitive markets, firms have such a small individual effect on the market, that taking other firms into account is simply not necessary. A monopolized market has only one firm, and thus strategic interactions do not occur.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma and Oligopoly

The prisoner’s dilemma shows why two individuals might not cooperate, even if it is collectively in their best interest to do so.

- Analyze the prisoner’s dilemma using the concepts of strategic dominance, Pareto optimality, and Nash equilibria

Sometimes firms fail to cooperate with each other, even when cooperation would bring about a better collective outcome. The prisoner’s dilemma is a canonical example of a game analyzed in game theory that shows why two individuals might not cooperate, even if it appears that it is in their best interest to do so.

In the game, two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of speaking to or exchanging messages with the other. The police offer each prisoner a bargain:

Prisoner’s Dilemma : Betrayal in the dominant strategy for both players, as it provides for a better individual outcome regardless of what the other player does. However, the resulting outcome is not Pareto-optimal. Both players would clearly have been better off if they had cooperated.

- If Prisoner A and Prisoner B both confess to the crime, each of them will serve two years in prison.

- If A confesses but B denies the crime, A will be set free, while B will serve three years in prison (and vice versa).

- If both A and B deny the crime, both of them will only serve one year in prison.

For both players, the choice to betray the partner by confessing has strategic dominance in this situation; it is the better strategy for each player regardless of what the other player does. This set of strategies is thus a Nash equilibrium in the game–no player would be better off by changing his or her strategy. As a result, all purely self-interested prisoners would betray each other, resulting in a two year prison sentence for both. This outcome is not Pareto optimal; it is clearly possible to improve the outcomes for both players through cooperation. If both players had denied the crime, they would each be serving only one year in prison.

Similarly to the prisoner’s dilemma scenario, cooperation is difficult to maintain in an oligopoly because cooperation is not in the best interest of the individual players. However, the collective outcome would be improved if firms cooperated, and were thus able to maintain low production, high prices, and monopoly profits.

One traditional example of game theory and the prisoner’s dilemma in practice involves soft drinks. Coca-Cola and Pepsi compete in an oligopoly, and thus are highly competitive against one another (as they have limited other competitive threats). Considering the similarity of their products in the soft drink industry (i.e. varying types of soda), any price deviation on part of one competitor is seen as an act of non-conformity or betrayal of an established status quo.

In such a scenario, there are a number of plausible reactions and outcomes. If Coca-Cola reduces their prices, Pepsi may follow to ensure they do not lose market share. In this situation, defection results in a lose-lose. Which is to say that, due to the initial price reduction by Coca-Cola (betrayal of status quo), both companies likely see reduced profit margins. On the other hand, Pepsi could uphold the price point despite Coca-Cola’s deviation, sacrificing market share to Coca-Cola but maintaining the established price point. Prisoner dilemma scenarios are difficult strategic choices, as any deviation from established competitive practice may result in less profits and/or market share.

Duopoly Example

The Cournot model, in which firms compete on output, and the Bertrand model, in which firms compete on price, describe duopoly dynamics.

- Discuss the characteristics of a duopoly

A true duopoly is a specific type of oligopoly where only two producers exist in a market. There are two principle duopoly models: Cournot duopoly and Bertrand duopoly.

Cournot Duopoly

Cournot duopoly is an economic model that describes an industry structure in which firms compete on output levels. The model makes the following assumptions:

- There are two firms, which produce a homogeneous product;

- The number of firms is fixed;

- Firms do not cooperate (there is no collusion);

- Firms have market power, and each firm’s output decision affects the good’s price;

- Firms are economically rational and act strategically, seeking to maximize profit given their competitor’s decisions; and

- Firms compete on quantity, and choose quantity simultaneously.

The Cournot model focuses on the production output decision of a single firm. The firm determines its rival’s output level, evaluates the residual market demand, and then changes its own output level to maximize profits. It is assumed that the firm’s output decision will not affect the output decision of its competitor.

For example, suppose that there are two firms in the market for toasters with a given demand function. Firm A will determine the output of Firm B, hold it constant, and then determine the remainder of the market demand for toasters. Firm A will then determine its profit-maximizing output for that residual demand as if it were the entire market, and produce accordingly. Firm B will be conducting similar calculations with respect to Firm A at the same time.

Bertrand Duopoly

The Bertrand model describes interactions among firms that compete on price. Firms set profit-maximizing prices in response to what they expect a competitor to charge. The model rests on the following assumptions:

- There are two firms producing homogeneous products;

- Firms do not cooperate;

- Firms compete by setting prices simultaneously; and

- Consumers buy everything from a firm with a lower price. If all firms charge the same price, consumers randomly select among them.

In the Bertrand model, Firm A’s optimum price depends on where it believes Firm B will set its price. Pricing just below the other firm will obtain full market demand, though this choice is not optimal if the other firm is pricing below marginal cost, as this would result in negative profits. If Firm B is setting the price below marginal cost, Firm A will set the price at marginal cost. If Firm B is setting the price above marginal cost but below monopoly price, then Firm A will set the price just below that of Firm B. If Firm B sets the price above monopoly price, Firm A will set the price at monopoly level.

Bertrand Duopoly : The diagram shows the reaction function of a firm competing on price. When P2 (the price set by Firm 2) is less than marginal cost, Firm 1 prices at marginal cost (P1=MC). When Firm 2 prices above MC but below monopoly prices, Firm 1 prices just below Firm 2. When Firm 2 prices above monopoly price (PM), Firm 1 prices at monopoly level (P1=PM).

Imagine if both firms set equal prices above marginal cost. Each firm would get half the market at a higher than marginal cost price. However, by lowering prices just slightly, a firm could gain the whole market. As a result, both firms are tempted to lower prices as much as they can. However, it would be irrational to price below marginal cost, because the firm would make a loss. Therefore, both firms will lower prices until they reach the marginal cost limit. According to this model, a duopoly will result in an outcome exactly equivalent to what prevails under perfect competition. The result of the firms’ strategies is a Nash equilibrium –a pair or strategies where neither firm can increase profits by unilaterally changing the price.

Colluding to charge the monopoly price and supplying one half of the market each is the best that the firms could do in this scenario. However, not colluding and charging the marginal cost, which is the non-cooperative outcome, is the only Nash equilibrium of this model.

The accuracy of the Cournot or Bertrand model will vary from industry to industry. If capacity and output can be easily changed, Bertrand is generally a better model of duopoly competition. If output and capacity are difficult to adjust, then Cournot is generally a better model.

Cartel Example

A cartel is a formal collusive arrangement among firms with the goal of increasing profits.

- Assess the role of competition and collusion in the formation of cartels

A cartel is an agreement among competing firms to collude in order to attain higher profits. Cartels usually occur in an oligopolistic industry, where the number of sellers is small and the products being traded are homogeneous. Cartel members may agree on such matters are price fixing, total industry output, market share, allocation of customers, allocation of territories, bid rigging, establishment of common sales agencies, and the division of profits.

Game theory suggests that cartels are inherently unstable, because the behavior of cartel members represents a prisoner’s dilemma. Each member of a cartel would be able to make a higher profit, at least in the short-run, by breaking the agreement (producing a greater quantity or selling at a lower price) than it would make by abiding by it. However, if the cartel collapses because of defections, the firms would revert to competing, profits would drop, and all would be worse off.

Whether members of a cartel choose to cheat on the agreement depends on whether the short-term returns to cheating outweigh the long-term losses from the possible breakdown of the cartel. It also partly depends on how difficult it is for firms to monitor whether the agreement is being adhered to by other firms. If monitoring is difficult, a member is likely to get away with cheating for longer; members would then be more likely to cheat, and the cartel will be more unstable.

Perhaps the most globally recognizable and effective cartel is OPEC, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. In 1973 members of OPEC reduced their production of oil. Because crude oil from the Middle East was known to have few substitutes, OPEC member’s profits skyrocketed. From 1973 to 1979, the price of oil increased by $70 per barrel, an unprecedented number at the time. In the mid 1980s, however, OPEC started to weaken. Discovery of new oil fields in Alaska and Canada introduced new alternatives to Middle Eastern oil, causing OPEC’s prices and profits to fall. Around the same time OPEC members also started cheating to try to increase individual profits.

OPEC : In the 1970s, OPEC members successfully colluded to reduce the global production of oil, leading to higher profits for member countries.

- Firms in an oligopoly may collude to set a price or output level for a market in order to maximize industry profits. At an extreme, the colluding firms can act as a monopoly.

- Oligopolists pursuing their individual self-interest would produce a greater quantity than a monopolist, and charge a lower price.

- Collusive arrangements are generally illegal. Moreover, it is difficult for firms to coordinate actions, and there is a threat that firms may defect and undermine the others in the arrangement.

- Price leadership, which occurs when a dominant competitor sets the industry price and others follow suit, is an informal type of collusion which is generally legal.

- In an oligopoly, firms are affected not only by their own production decisions, but by the production decisions of other firms in the market as well. Game theory models situations in which each actor, when deciding on a course of action, must also consider how others might respond to that action.

- The prisoner’s dilemma is a type of game that illustrates why cooperation is difficult to maintain for oligopolists even when it is mutually beneficial. In this game, the dominant strategy of each actor is to defect. However, acting in self-interest leads to a sub-optimal collective outcome.

- The Nash equilibrium is an important concept in game theory. It is the set of strategies such that no player can do better by unilaterally changing his or her strategy.

- Game theory is generally not needed to understand competitive or monopolized markets.

- In the game, two criminals are arrested and imprisoned. Each criminal must decide whether he will cooperate with or betray his partner. The criminals cannot communicate to coordinate their actions.

- Betrayal is the dominant strategy for both players in the game. Betrayal leads to best individual outcome regardless of what the other person does.

- Both players choosing betrayal is the Nash equilibrium of the game. However, this outcome is not Pareto-optimal. Both players would have clearly been better off if they had cooperated.

- Cooperation by firms in oligopolies is difficult to achieve because defection is in the best interest of each individual firm.

- The Cournot model focuses on the production output decision of a single firm. A firm determines its competitor’s output level and the residual market demand. It then determines its profit -maximizing output for that residual demand as if it were the entire market, and produces accordingly.

- In the Bertrand model, firms set profit-maximizing prices in response to what they expect the competitor to charge. The model predicts that both firms will lower prices until they reach the marginal cost limit, arriving at an outcome equivalent to what prevails under perfect competition.

- The accuracy of the Cournot or Bertrand model will vary from industry to industry, depending on how easy it is to adjust output levels in the industry.

- Cartel members cooperate to set industry price and output.

- Game theory indicates that cartels are inherently unstable. Each individual member has an incentive to cheat in order to make higher profits in the short run.

- Cheating may lead to the collapse of a cartel. With the collapse, firms would revert to competing, which would lead to decreased profits.

- OPEC, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, provides an example of a historically effective cartel.

- Price leadership : Occurs when one company, usually the dominant competitor among several, leads the way in determining prices, the others soon following.

- collusion : A secret agreement for an illegal purpose; conspiracy.

- price fixing : An agreement between sellers to sell a product only at a fixed price, or maintain the market conditions such that the price is maintained at a given level by controlling supply.

- Prisoner’s dilemma : A game that shows why two individuals might not cooperate, even if it appears that it is in their best interests to do so.