Literature Reviews

- General overview of Literature Reviews

- What should a Literature Review include?

- Examples of Literature Reviews

- Research - Getting Started

Online Resources

- CWU Learning Commons: Writing Resources

- Purdue OWL: Writing a Literature Review

Literature Reviews Examples

Social Sciences examples

- Psychology study In this example, the literature review can be found on pages 1086-1089, stopping at the section labeled "Aims and Hypotheses".

- Law and Justice study In this example, the literature review can be found on pages 431-449, stopping at the section labeled "Identifying and Evaluating the Impacts of the Prisoners' Rights Movement". This article uses a historical literature review approach.

- Anthropology study The literature review in this article runs from page 218 at the heading "Between Critique and Enchantment" and ends on page 221 before the heading "The Imagination as a Dimension of Reality".

Hard Science examples

- Physics article The literature review in this paper can be found in the Introduction section, ending at the section titled "Experimental procedure".

- Health Science article The literature review in this article is located at the beginning, before the Methods section.

Arts and Humanities examples

- Composition paper In this example, the literature review has its own dedicated section titled "Literature Review" on pages 2-3.

- Political geography paper The literature review in this paper is located in the introduction section.

Standalone Literature Review examples

- Project-based learning: A review of the literature

- Mental health and gender dysphoria: A review of the literature

- Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations

- << Previous: What should a Literature Review include?

- Next: Research - Getting Started >>

- Last Updated: Mar 29, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.lib.cwu.edu/LiteratureReviews

- UWF Libraries

Literature Review: Conducting & Writing

- Sample Literature Reviews

- Steps for Conducting a Lit Review

- Finding "The Literature"

- Organizing/Writing

- APA Style This link opens in a new window

- Chicago: Notes Bibliography This link opens in a new window

- MLA Style This link opens in a new window

Sample Lit Reviews from Communication Arts

Have an exemplary literature review.

- Literature Review Sample 1

- Literature Review Sample 2

- Literature Review Sample 3

Have you written a stellar literature review you care to share for teaching purposes?

Are you an instructor who has received an exemplary literature review and have permission from the student to post?

Please contact Britt McGowan at [email protected] for inclusion in this guide. All disciplines welcome and encouraged.

- << Previous: MLA Style

- Next: Get Help! >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 9:37 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uwf.edu/litreview

University Library

- Research Guides

Criminology & Criminal Justice

- Literature Reviews

- Getting Started

- News, Newspapers, and Current Events

- Books and Media

- Journals, Databases, and Collections

- Data and Statistics

- Careers and Career Resources for Criminology and Social Justice Majors

- Annotated Bibliographies

- APA 6th Edition

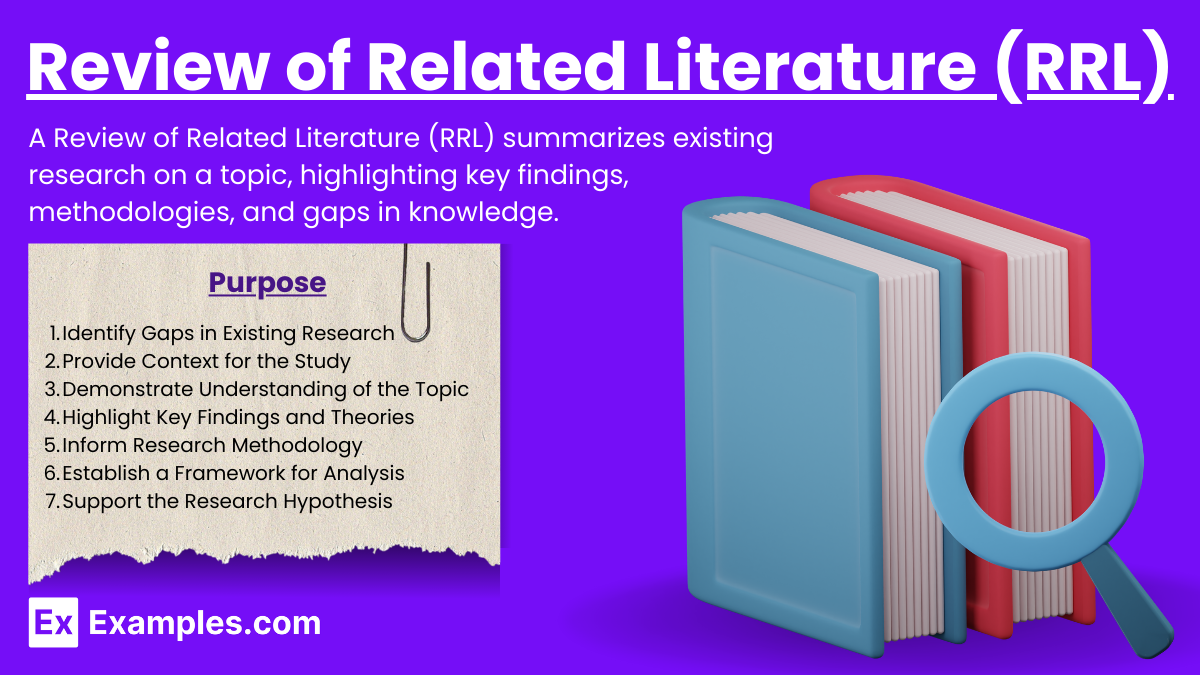

What is a Literature Review?

The scholarly conversation.

A literature review provides an overview of previous research on a topic that critically evaluates, classifies, and compares what has already been published on a particular topic. It allows the author to synthesize and place into context the research and scholarly literature relevant to the topic. It helps map the different approaches to a given question and reveals patterns. It forms the foundation for the author’s subsequent research and justifies the significance of the new investigation.

A literature review can be a short introductory section of a research article or a report or policy paper that focuses on recent research. Or, in the case of dissertations, theses, and review articles, it can be an extensive review of all relevant research.

- The format is usually a bibliographic essay; sources are briefly cited within the body of the essay, with full bibliographic citations at the end.

- The introduction should define the topic and set the context for the literature review. It will include the author's perspective or point of view on the topic, how they have defined the scope of the topic (including what's not included), and how the review will be organized. It can point out overall trends, conflicts in methodology or conclusions, and gaps in the research.

- In the body of the review, the author should organize the research into major topics and subtopics. These groupings may be by subject, (e.g., globalization of clothing manufacturing), type of research (e.g., case studies), methodology (e.g., qualitative), genre, chronology, or other common characteristics. Within these groups, the author can then discuss the merits of each article and analyze and compare the importance of each article to similar ones.

- The conclusion will summarize the main findings, make clear how this review of the literature supports (or not) the research to follow, and may point the direction for further research.

- The list of references will include full citations for all of the items mentioned in the literature review.

Key Questions for a Literature Review

A literature review should try to answer questions such as

- Who are the key researchers on this topic?

- What has been the focus of the research efforts so far and what is the current status?

- How have certain studies built on prior studies? Where are the connections? Are there new interpretations of the research?

- Have there been any controversies or debate about the research? Is there consensus? Are there any contradictions?

- Which areas have been identified as needing further research? Have any pathways been suggested?

- How will your topic uniquely contribute to this body of knowledge?

- Which methodologies have researchers used and which appear to be the most productive?

- What sources of information or data were identified that might be useful to you?

- How does your particular topic fit into the larger context of what has already been done?

- How has the research that has already been done help frame your current investigation ?

Examples of Literature Reviews

Example of a literature review at the beginning of an article: Forbes, C. C., Blanchard, C. M., Mummery, W. K., & Courneya, K. S. (2015, March). Prevalence and correlates of strength exercise among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors . Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(2), 118+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.sonoma.idm.oclc.org/ps/i.do?p=HRCA&sw=w&u=sonomacsu&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA422059606&asid=27e45873fddc413ac1bebbc129f7649c Example of a comprehensive review of the literature: Wilson, J. L. (2016). An exploration of bullying behaviours in nursing: a review of the literature. British Journal Of Nursing , 25 (6), 303-306. For additional examples, see:

Galvan, J., Galvan, M., & ProQuest. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (Seventh ed.). [Electronic book]

Pan, M., & Lopez, M. (2008). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Pub. [ Q180.55.E9 P36 2008]

Useful Links

- Write a Literature Review (UCSC)

- Literature Reviews (Purdue)

- Literature Reviews: overview (UNC)

- Review of Literature (UW-Madison)

Evidence Matrix for Literature Reviews

The Evidence Matrix can help you organize your research before writing your lit review. Use it to identify patterns and commonalities in the articles you have found--similar methodologies ? common theoretical frameworks ? It helps you make sure that all your major concepts covered. It also helps you see how your research fits into the context of the overall topic.

- Evidence Matrix Special thanks to Dr. Cindy Stearns, SSU Sociology Dept, for permission to use this Matrix as an example.

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliographies

- Next: ASA style >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 12:31 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sonoma.edu/CCJS

leiden lawmethods portal

Systematic literature review.

Last update: December 10, 2020

‘Literature review’ can refer to a portion of a research article in which the author(s) describe(s) or summarizes a body of literature which is relevant to their article. ‘Literature review’ can also refer to a methodological approach in which a selection of existing literature is collected and analyzed in order to answer a specific question. One approach to doing this type of literature review is called a ‘systematic literature review’ (SLR).

When conducting an SLR, the researcher creates a set of rules or guidelines prior to beginning the review. These rules determine the characteristics of the literature to be included and the steps to be followed during the research process. Creating these rules helps the researcher by narrowing down the focus of their project and the scope of the literature to be included, and they aid in making the research methodology transparent and replicable.

There are many different ways that an SLR can be used in socio-legal research. For example, an SLR can be used to show the impact of a certain law or policy (Loong e.a. 2019), uncover patterns across literature (e.g. perpetrator characteristics) (Alleyne & Parfitt 2017), outline crime prevention strategies that are currently in place (Gorden & Buchanan 2013), describe to what extent a problem is understood or researched (Krieger 2013), point out the gaps in the current research (Urinboyev e.a. 2016), or identify potential areas for future research. Various types of documents may be included in an SLR such as court transcripts, academic literature, news articles, NGO reports or government documents.

The first step for starting your SLR is creating a research journal in which you will write down your SLR rules and keep track of your daily activities. This will help you keep a timeline of your project, keep track of your decision making process, and maintain the transparency and replicability of your research. The next step is determining your research question. When you have your research question, you can create the inclusion and exclusion criteria or the characteristics that literature must or must not have to be included in your SLR. The key question is “what kind of information is needed to answer the research question?” It is necessary to explain why the criteria were selected. After this, you can begin searching for and collecting literature which meets your inclusion criteria. Different databases and sources of literature (e.g. academic journals or newspapers) will yield different search results, so it may be helpful to do trial searches to see which sources provide the most relevant literature for your project. Once you have collected all of your literature, you can begin reading and analyzing the literature.

There are various research tools that can aid you in conducting your SLR such as qualitative data analysis software (e.g. ATLAS.ti) or reference manager software (e.g. Mendeley). Determine which programs to use based on your personal preference and your research project.

Fink, A. (2014). Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Hagen-Zanker, J. & Mallet, R. (2013). How to do a Rigorous, Evidence Focused Literature Review in International Development: A Guidance Note. Working paper Overseas Direct Investment.

Oliver, S., & Sutcliffe, K. (2012). Describing and analysing studies. Gough, D. A. & Oliver, S. In An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. London, UK. SAGE.

Pittaway, L. (2008). Systematic Literature Reviews. Thorpe, R. & Holt, R. In T he Sage Dictionary of Qualitative Management Research . London, UK. SAGE.

Siddaway, A. (2014). What Is a Systematic Literature Review and How Do I Do One?

Snel, M. & de Moraes, J. (2018). Doing a Systematic Literature Review in Legal Scholarship. The Hague, NL. Eleven International Publishing.

Interactive Learning Module 1: Introduction to Conducting Systematic Reviews

Alleyne, E. & Parfitt, C. (2017). Adult-Perpetrated Animal Abuse: A Systematic Literature Review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. Vol. 20. No. 3. Pp. 344-357.

Example of a systematic literature review.

Brown, R. T. (2010). Systematic Review of the Impact of Adult Drug-Treatment Courts. Translational Research . Vol. 155. No 6. Pp. 263-274.

Gorden, C., & Buchanan, J. (2013). A Systematic Literature Review of Doorstep Crime: Are the Crime-Prevention Strategies More Harmful than the Crime? The Howard Journal . Vol. 52. No. 5. Pp. 498-515.

Krieger, M. A. (2016). Unpacking “Sexting”: A Systematic Review of Nonconensual Sexting in Legal, Educational, and Psychological Literatures. Trauma, Violence & Abuse . Vol. 18. No. 5. Pp. 593-601.

Loong, D., Bonato, S., Barnsley, J., & Dewa, C. S. (2019). The Effectiveness of Mental Health Courts in Reducing Recidivism and Police Contact: A Systematic Review. Community Mental Health Journal. Vol. 55. No. 7 Pp. 1073-1098.

Urinboyev, R., Wickenberg, P., & Leo, U. (2016). Child Rights, Classroom, and Social Management: A Systematic Literature Review. The International Journal of Children’s Rights. Vol. 24. No. 3. Pp. 522-547.

- A-Z Databases

- Training Calendar

- Research Portal

Law: Introduction to Research

- Finding a Research Topic

- Getting Started

- Generate Research Ideas

- Brainstorming

- Scanning Material

- Suitability Analysis

- The difference between a topic and a research question

Literature Review

- Referencing

When thinking about any risks associated with your research you may realise that it is difficult to predict your research needs and the accompanying risks as you were not sure what information would be required; this is why a literature review is necessary. A thorough literature review will help identify gaps in existing knowledge where research is needed; filling those gaps is one of the prime functions of research. The literature review will indicate what is known about your chosen area of research and show where further contributions from further research can be made.

Undertaking a literature review is probably one of the most difficult stages of the research process but it can be both exciting and fulfilling. This section aims to put the literature review into context and to explain what it does and how to do it.

The literature on a particular legal topic is of fundamental importance to the international community of researchers and scholars working within particular academic disciplines. Academic publishing supports research by enabling researchers to tell the world what they have discovered and allows others researching in the same area to peer review their work; in this way, a combined body of knowledge is established.

During your research, you will use the literature to:

- develop your knowledge of your chosen topic and the research process in general terms

- ensure that you have an understanding of the current state of academic knowledge within your chosen topic

- identify the gaps in knowledge that your research will address

- ensure that your research question will not become too broad or narrow.

The Purpose of Literature Review

Understanding existing research is at the core of your study. A good literature review is important because it enables you to understand the existing work in your chosen topic as well as explaining concepts, approaches and ideas relevant to that topic.

The literature review is also essential as it will enable you to identify an appropriate research method. Your research method, and needs, can only be established in the light of a review of existing knowledge.

Your literature review is regarded as secondary research. The research process is an ongoing one, so your literature review is never really finished or entirely up to date as reading and understanding the existing literature is a constant part of being a researcher; professionally it is an obligation.

Different Types of Research

- Different types of research

- Different sources

- Understand research in your chosen area

- Explaining relevant concepts and ideas

- Contextualizing your results

- What to read?

- Peer review

- Searching the literature

- Critically evaluating documents

Your research will draw upon both primary and secondary research. The difference between primary and secondary research is that primary research is new research on a topic that adds to the existing body of knowledge. Secondary research is research into what others have written or said on the topic.

You will also draw upon primary and secondary sources to undertake your research. Primary sources are evidence recorded at the time, such as a photograph, an artifact, a diary, or the text of a statute or court ruling. Primary legal sources are the products of those bodies with the authority to make, interpret and apply the law. Secondary sources are what others have written or said about the primary source, their interpretation, support, or critique of the primary source. Similarly, secondary legal sources are what academics, lawyers, politicians, journalists, and others have said or written about a primary legal source.

Part of the aim of your studies is to make a contribution to the existing body of academic knowledge. Without a literature review there would be a risk that what you are producing is not actually newly researched knowledge; instead it may only be a replication of what is already known. The only way to ensure that your research is new is to find out what others have already done. However, this is not to say that you should never attempt to research some things that have been done before if you feel that you can provide valuable new insights.

You also need to use the literature review to build a body of useful ideas to help you conceptualise your research question and understand the current thinking on the topic. By studying the literature you will become familiar with research methods appropriate to your chosen topic and this will show you how to apply them. Careful consideration should be given to the research methods deployed by existing researchers in the topic, but this should not stifle innovative approaches. Your literature study should also demonstrate the context of your own work, and how it relates, and builds, on the work of others; ‘to make proper acknowledgment of the work of previous authors and to delineate [your] own contributions to the field’ (Sharp et al., 2002, p. 28).

When you have completed your primary research, you will still have the task of demonstrating how your research contributes to the topic in which you have been working. Comparing your results to similar work within the topic will demonstrate how you have moved the discipline forward.

Comparing your results with the gaps that you identified in the early stages of your literature review will allow you to evaluate how well you have addressed them.

A successful literature review will have references from a number of different types of sources; it is not simply a book review. What is much more important than the number of references is that you have a selection of literature that is appropriate for your research; what is appropriate will depend on the type of research you are undertaking. For example, if your topic is in an area of recent legal debate, you will probably find most of the relevant material in journal articles or conference papers. If you are studying policy issues in law-making, you would expect to cite more government reports. In either case, you will need some core references that are recent and relevant. A research project could also contain a number of older citations to provide a historical context or describe established methods. Perhaps a recent newspaper, journal or magazine article could illustrate the contemporary relevance or importance of your research.

You will have to use your own judgment (and the advice of your tutor) to ascertain what the suitable range of literature and references is for your review. This will differ for each topic of research, but you will be able to get a feel for what is appropriate by looking at relevant publications; most publications fall into the following broad categories:

Online legal databases

Online legal research services such as Westlaw , LexisNexis , JSTOR , EBSCOhost , or HeinOnline are a good source of journal articles and as a repository of legislation, case law, law reports, newspaper and magazine articles, public records, and treatises.

Journal articles

These provide more recent discussions than textbooks. Peer-reviewed journals are the gold standard for academic quality. Having at least some journal articles in your literature review is almost always required. Note that the lead time on journal articles is often up to two years, so they may not be sufficiently up to date for fast-moving areas. Look for special issues of journals, as these usually focus on a particular topic and you may find that they are more relevant to your area of research.

Many law schools host journals that contain articles by academics and students; these may also be of interest. Other sources could include online newspapers such as The Conversation which are sourced from academia and designed to highlight current academic research or respond to current events.

Conference literature

Academic conferences are meetings in which groups of academics working in a particular area meet to discuss their work. Delegates usually write one or more papers that are then collected into a volume or special edition of a journal. Conference proceedings can be quite good in providing a snapshot of a topic, as they tend to be quite focused. Looking at the authors of the papers can also give you an idea of who the key names in that area are. The quality varies widely, both in terms of the material published and how it is presented. Most conferences include some professional researchers, some of whom can be contacted, and lots of students. Conference papers are often refereed but usually not to the same level as journal articles.

Having conference papers in your literature review does lend academic credibility, especially in rapidly developing areas, and conference papers generally contain the preliminary work that eventually forms journal articles.

Textbooks are good for identifying established, well-understood concepts and techniques, but are unlikely to have enough up-to-date research to be the main source of literature. Most disciplines, however, have a collection of canonical reference works that you should use to ensure you are implementing standard terms or techniques correctly. Textbooks can also be useful as a starting point for your literature search as you can investigate journal articles or conference papers that have been cited. Footnotes are a rich source of preliminary leads.

Law magazines

These can be useful, particularly for projects related to the role of lawyers. Be aware of the possibility of law firm bias (for example in labour law towards employers, employee rights, or trade unions) or articles that are little more than advertisements. Examples of professional journals include the SA ePublications (Sabinet), De Rebus - SA Attorneys' Journal , etc . Most jurisdictions have some form of a professional journal.

Government and other official reports

There is a wide range of publications, including ‘white papers', official reports, census, and other government-produced statistical data that are potentially useful to the researcher. Be aware of the possibility of political or economic bias or the reflection of a situation that has since changed.

Internal company or organisation reports/Institutional repository

These may be useful in a few situations but should be used sparingly, particularly if they are not readily available to the wider community of researchers. They will also not have been through a process of academic review. Such unpublished or semi-published reports are collectively called ‘grey literature.

Manuals and handbooks

These are of limited relevance, but may be useful to establish current techniques, approaches, and procedures.

Specialist supplements from quality newspapers can provide useful up-to-date information, as can the online versions of the same papers. Some newspapers provide a searchable archive that can provide a more general interest context for your work.

The worldwide web

This is widely used by lawyers today. According to the 2011 American Bar Association Report, 84.4% of attorneys turn to online sources as their first step in legal research (Lenhart, 2012, p. 27). It is an extremely useful source of references, particularly whilst carrying out an initial investigation. Although sites such as Wikipedia can be very helpful for providing a quick overview of particular topics and highlighting other areas of research that may be connected to your own, they should not usually be included in your review as they are of variable quality and are open to very rapid change. Treat the information you find on the internet with appropriate care. Be very careful about the source of information and look carefully at who operates the website.

Personal communications

Personal communications such as (unpublished) letters and conversations are not references. If you use such comments (and of course, you should respect the confidence of anyone you have discussed your work with), you should draw attention to the fact that you are quoting someone and mark it as ‘personal communication’ in the body of the text. Responses you might obtain from, for example, interviews and questionnaires as part of your research should be reported as data obtained through primary research.

It is crucial that most of your literature should come from peer-reviewed materials, such as journal articles. The point of peer reviewing is to increase quality by ensuring that the ideas presented seem well-founded to other experts in the topic. Conference papers are generally peer-reviewed, although the review process is usually less stringent, and so the standing of conference papers is not the same as for journals. Books, magazines, newspapers, and websites (including blogs, wikis, corporate sites, etc.) are not subject to peer review, and you should treat them with appropriate caution. Also, treat each publication on its merits; it is more helpful to use a good conference paper than a poor journal paper. Similarly, it is acceptable to refer to a well-written blog by a knowledgeable and well-known author provided that you supply appropriate context. In all these cases, the important thing is that you interpret the work correctly.

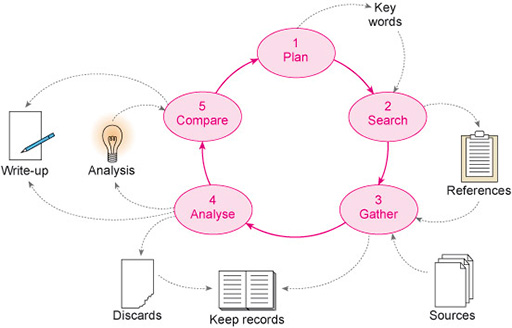

You will have undertaken legal research and developed your research skills as you prepared for earlier assignments. A literature review builds on this. You may, however, be wondering where to start. One technique is to use an iteration of five stages to help you with your early research.

The five stages are: planning, searching, gathering, analysing and comparing.

Following these stages will provide you with a systematic approach to gathering and analysing literature in your chosen topic of study; this will ensure that you take a critical approach to the literature.

To undertake an effective review of the literature on your chosen topic you will need to plan your review carefully. This includes setting aside enough time in which to undertake your review. In planning there are several aspects you need to think about:

- What sources of information are most relevant to your chosen research question?

- What gaps in knowledge have you identified in your chosen topic and used as a basis for your research question?

- What search terms will you use and how will you refine these?

- How will you record your sources?

- How will you interrogate those sources?

- How will you continue to review the literature as you progress with your research in order to keep as up-to-date as possible?

- Are you able to easily access all the sources you need?

- What arrangements may you need to make to access any hard copy materials?

- Will you join one of the legal alert services to keep you abreast of changes in your chosen topic (such as new court judgments)?

- What notes of progress will you record in your research diary?

Spending time thinking about all aspects of the literature review, planning your time, and setting yourself targets will help to keep your research on track and will enable you to record your progress and any adjustments you make, along with the reasons for those adjustments.

This section is designed to provide you with some reminders in relation to searching, choosing search terms and some ideas about where to start in undertaking a literature review.

Where to start

The best places to start are likely to be a legal database (or law library) and Google Scholar. Many students and academics now use Google Scholar as one of their ‘go to’ tools for scholarly research. It can be helpful to gain an overview of a topic or to gain a sense of direction, but it is not a substitute for your own research of primary and secondary sources.

Having gained an overview from your initial search through browsing general collections of documents, you will then need to undertake a more detailed search to find specific documents. Identifying relevant scholarly articles and following links in footnotes and bibliographies can be helpful as you continue your search for relevant information.

One of the decisions you will have to make is when to stop working on your literature review and your research, and when to start writing up your dissertation. This will be determined by the material you gather and the time constraints you are working on.

Selecting resources

One starting point may be to locate a small number of key journal papers or articles; for a draft outline proposal for your research, you might have around four to six of these, accumulating more as you develop the research subsequently. Aim for quality, not quantity. Look for relevant and recent publications. Most of your references will typically not be more than four years old, although this does depend on your field of study. You will need quite a few more in due course to cover other aspects of your research such as methods and evaluation, but at this stage, you need only a few recent items.

While reading these documents, aim to identify the key issues that are essential to your research question, ideally around four to six.

Compare and contrast the literature, looking for commonalities, agreements, and disagreements and for problem identification and possible answers. Then write up your analysis of the comparison and any conclusions you might reach. The required outcome will be that you can make an informed decision about how to proceed with your primary research, based on the work carried out by other researchers.

Note that ultimately there are no infallible means of assessing the value of a given reference. Its source may be a useful indication, but you have to use your judgment about its value for your research.

Reviewing your sources

Skim read each document to decide whether a book or paper is worth reading in more depth. To do this you need to make use of the various signposts that are available from the:

- notes on a book’s cover can help situate the content

- abstract (for a paper), or the preface (for a book)

- contents page

- introduction

- conclusions

- references section (sometimes called the ‘bibliography’)

In your record, make a brief note (one or two sentences) of the main points.

Next, skim through the opening page of each chapter, or the first paragraph of each section. This should give you enough information to assess whether you need to read the book or paper in more depth, again make a suitable note against that record.

Reading in more detail: SQ3R

If you have decided to look in more detail at a source document that you have to skim read, you can use the well-known ‘SQ3R’ approach (Skimming, Questioning, Reading, Recalling, and Reviewing).

1. Skimming – skim reading the chapter or part of the paper that relates to your topic, or otherwise interests you.

2. Questioning – develop a few questions that you consider the text might answer for you. You can often use journal, chapter, or section titles to help you formulate relevant questions. For example, when studying a journal article with the title, ‘Me and my body: the relevance of the distinction for the difference between withdrawing life support and euthanasia’, you might ask, ‘How is the distinction between withdrawing life support and euthanasia drawn?’

3. Reading – read through the chapter, section, or paper with your questions in mind. Do not make notes at this stage.

4. Recalling – make notes on what you have read. You should normally develop your own summary or answers to your questions. There will also be short passages that you may want to note fully, perhaps to use as a quotation for when you write up your literature review. Be sure to note carefully the page(s) on which the quotation appears.

5. Reviewing – check through the process, perhaps flicking through the section or article again. It is also worth emphasising that if you maintain your reference list as you go along, not only will you save yourself a lot of work in later stages of the research, but you will also have all the necessary details to hand for writing up with fewer mistakes.

(adapted from Blaxter et al., 1996, p. 114)

There is no doubt that this approach takes considerably more effort than sitting back and studying a text passively. The benefit from the extra work involved in the development of a critical approach, which you must adopt for your research.

Following citations in a paper

When you have found (and read) your first couple of papers, you can then use them to seed your search for other useful literature. In this case, we will use this example:

When we looked at the references list in Suppon, J. F. (2010) ‘Life after death: the need to address the legal status of posthumously conceived children', Family Court Review , vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 228–45, a couple of items, going only by the titles, looked promising:

- Doucettperry, Major M. (2008) ‘To Be Continued: A Look at Posthumous Reproduction As It Relates to Today’s Military’, The Army Lawyer , no. 420, pp. 1–22.

- Karlin, J. H. (2006) ‘“Daddy, Can you Spare a Dime?”: Intestate Heir Rights of Posthumously Conceived Children’, Temple Law Review , vol. 79, no. 4, pp. 1317–54.

These are simply the papers that we felt looked most appropriate from the references. There is no formula for determining the best paper; you simply need to read a few and try to develop a feel for which seem the most appropriate for your own research project. You should only be citing papers that contribute to your research in a significant way, or that you have included material from; not everything that you read (and discarded) along the way.

Recording your references

We strongly suggest that you establish a recording system at the outset when you begin your research and keep maintaining records in an organised and complete manner as you progress. You need to choose a consistent method of recording your references; this is a personal choice and can be paper-based or electronic. Do not be tempted to have more than one method or repository as this can lead to confusion and unnecessary extra work. There are software tools available that can help you to both organise your references and incorporate them into your written work. Always keep a backup copy of your records.

The following is a suggestion as to how you might record any document that you think you may use.

Open a new record, and record the basic details:

- author(s), including initials

- date of publication

- title of work or article.

Additionally, for books:

- place of publication

- page numbers of relevant material.

Additionally, for journal papers:

- journal name

- volume and issue number

- page range of the whole article.

‘How many references are needed to make a good literature review?’ There is no straightforward answer to this. In general, an appropriate number of references would be in the range of 15 to 25, with around 20 being typical. However, this is not hard and fast and will depend on the topic and research question chosen.

The crucial thing is to aim for quality and relevance ; there is no credit to be gained from amassing a lengthy list of material, even if it all appears to be relevant. Part of your task is to select a range of references that is appropriate for the length and scope of your research project. It is easier, and more conducive to good research, to handle a smaller number of references specifically chosen to support your argument. Remember also that in general, a student whose research project contained a smaller number of references would generally be expected to demonstrate a deeper and more critical understanding of those references.

A colleague once commented on a student’s work in the following vein: ‘I don’t really need you to tell me what the author thinks since I can read her thoughts myself, but I do want to know what you think about what the author thinks’. Literature reviews are not a description of what has been written by other people in a particular field, they should be a discussion of what you think of what they have written, and how it helps clarify your own thinking.

This is why critical judgement is so important for your literature review. You must exercise critical judgement when determining which sources to read in-depth, and when evaluating the argument they put forward. Finally, critical judgement is important in communicating how those arguments might frame your research. It should not be a narrative of what you have read and the stories those sources tell. It should be sparing in its description of others’ arguments, and expansive in how those arguments have shaped your own thinking.

You need to exercise critical judgement as to which resources are the most useful and worthy of discussion. Having done this, you also need to ensure that your review is analytical rather than descriptive. A critical review extracts elements from the resource that directly relate to the chosen research interest; it debates them, or compares and contrasts them with how other resources have analysed them. A critical examination of the literature should allow you to develop your understanding of your research question. It should guide you to what knowledge you will need to answer your research question, and begin to develop some subsidiary questions. This will break the content down into more manageable and achievable segments of knowledge that you require.

Some elements of a good critical literature review are:

- relating different writings to each other, indicating their differences and contradictions, and highlighting what they lack

- understanding the values and theories that inform, and colour, reading and writing

- viewing research writing as an environment of contested views and positions

- placing the material in the context of your own research.

An excellent way to critically analyse a document is to use the PROMPT system. The PROMPT system indicates what factors you should consider when evaluating a document. PROMPT stands for:

- Presentation – is the publication easy to read?

- Relevance – how will the publication help address your research aim?

- Objectivity – what is the balance between evidence and opinion? Does the evidence seem balanced? How was the research funded?

- Method – was the research in the publication carried out appropriately?

- Provenance – who is the author and how was the document published?

- Timeliness – is the publication still relevant, or has it been superseded?

By thinking about each of these factors when you read a publication in-depth, you will be able to provide a deeper, more critical analysis of each publication. A final tip for critical reading is to note down your overall impressions and any questions you still have at the end. Keeping a list of such open questions can help you identify the gaps in the literature by noticing which questions were raised, but not answered, by the publication; this, in turn, will guide your research.

In the planning stage, you thought about the gaps in existing knowledge you had identified, and which you then used as a basis to develop your research question. Through the work, you undertook in the earlier stages of your literature review you have a clear understanding of the existing work within the topic. At this point, a comparison of the results of your literature review, with the gaps you had previously identified, will enable you to reflect, and consider, whether you now have enough knowledge to address those gaps. You can then evaluate whether you need to further refine your literature review.

- << Previous: The difference between a topic and a research question

- Next: Referencing >>

- Last Updated: Sep 10, 2023 9:54 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uwc.ac.za/c.php?g=1159497

UWC LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICES

Law Literature Review Example

Discover high-quality law literature review examples to enhance your understanding and research in legal studies.

2M+ Professionals choose us

Maximize Your Legal Research

Efficient research.

Access comprehensive law literature reviews to expedite your research process and make informed decisions.

Accurate Analysis

Ensure precision in your legal analysis with meticulously crafted literature review examples from Justdone.ai.

Expert Knowledge

Gain access to expert insights and perspectives through our curated law literature review examples.

Law Literature Review Example Benefits

Comprehensive analysis.

Our law literature review example provides a comprehensive analysis of relevant legal materials, offering in-depth insights into various legal topics. Whether you need to review case laws, statutes, or legal theories, our examples cover a wide range of legal literature, ensuring a thorough understanding.

The comprehensive nature of the examples allows readers to gain a deep understanding of the legal concepts, enabling them to apply critical analysis and evaluation techniques effectively. By using our literature review examples, legal professionals and scholars can delve into complex legal issues with confidence and expertise.

Quality References

Our law literature review examples are crafted with quality references from authoritative legal sources, ensuring the reliability and credibility of the content. These examples feature references from leading legal journals, court opinions, and legislative documents, providing readers with access to reputable and current legal literature.

Having access to examples with quality references allows readers to bolster their own research with credible sources, strengthening the validity and scholarly merit of their work. By utilizing our examples, individuals can enhance the academic rigor and reliability of their legal literature reviews.

Time-Saving Resource

Our law literature review examples serve as a time-saving resource for legal professionals, students, and researchers, offering readily available templates for structuring and organizing their literature reviews. With our examples, individuals can streamline their research process and focus on analyzing the legal content, saving valuable time and effort.

The convenience of using our examples as a guide enables users to efficiently navigate the intricacies of legal literature review, optimizing their productivity and allowing them to dedicate more time to critical analysis and interpretation of legal materials.

Essential Tips for Law Literature Review Examples

Thorough analysis.

When utilizing law literature review examples, it's essential to conduct a thorough analysis of the referenced legal materials to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. By critically evaluating the content, individuals can extract valuable insights and strengthen the scholarly depth of their literature reviews.

Engaging in a meticulous analysis of the examples enhances the overall quality and academic rigor of the literature review, enabling readers to showcase a nuanced comprehension of the legal concepts and principles.

Integration of Perspectives

Incorporating diverse legal perspectives within the literature review examples is crucial for presenting a well-rounded analysis of the subject matter. By integrating multiple viewpoints and legal theories, individuals can enrich the depth and breadth of their literature reviews, offering a comprehensive exploration of the legal topic.

The inclusion of various perspectives fosters a more holistic understanding of the legal issues, allowing readers to present a comprehensive and balanced assessment within their literature reviews.

Effective Citation Practices

Adhering to effective citation practices within the literature review examples is paramount for maintaining academic integrity and acknowledging the sources of legal information. Implementing proper citation formats and referencing techniques ensures the ethical use of legal materials, enhancing the credibility and authenticity of the literature review.

By demonstrating meticulous citation practices, individuals can uphold the scholarly standards of their work, while also providing readers with clear pathways to access the cited legal literature.

Critical Engagement

Engaging in critical analysis and interpretation of the law literature review examples is fundamental for constructing informed and insightful scholarly evaluations. By critically examining the content, individuals can develop astute observations and construct compelling arguments within their literature reviews, elevating the intellectual rigor of their work.

The process of critically engaging with the examples cultivates a deeper level of scholarly inquiry, empowering individuals to contribute meaningful insights and original perspectives within their literature reviews.

Strategic Organization

Strategically organizing the structure and presentation of the literature review examples is vital for facilitating a coherent and logical flow of legal analysis. By carefully arranging the content, individuals can enhance the readability and comprehension of their literature reviews, guiding readers through a well-structured exploration of the legal materials.

Implementing a strategic organizational approach ensures that the literature review examples effectively convey the complexities of the legal subject matter, providing readers with a clear and cohesive narrative of the analyzed legal literature.

Exploring Law Literature Review Examples

Discover the power of law literature review examples in gaining comprehensive insights and crafting scholarly evaluations within legal literature.

Present a detailed analysis of a landmark legal case and its implications on constitutional law.

In this law literature review example, we delve into the landmark case of Marbury v. Madison, exploring its profound impact on constitutional law and the establishment of judicial review. Through a meticulous examination of the case's historical context and judicial proceedings, we elucidate the pivotal role of Chief Justice John Marshall in shaping the foundations of constitutional interpretation.

By critically analyzing the case's implications and legal implications, we offer a comprehensive assessment of its enduring significance within the realm of constitutional law. This example provides readers with a scholarly exposition of the case's doctrinal implications and its enduring influence on the judicial landscape, showcasing the intricate interplay of legal principles and constitutional precedents.

Furthermore, our exploration delves into the scholarly discourse surrounding Marbury v. Madison, presenting a synthesis of diverse legal perspectives and scholarly analyses that enrich the understanding of this seminal case. Through a nuanced examination of the case's implications, readers gain valuable insights into the complexities of constitutional law and the enduring legacy of judicial review.

By engaging with this law literature review example, individuals can gain a comprehensive understanding of the case's historical significance, doctrinal implications, and scholarly interpretations, empowering them to construct informed and insightful evaluations within the realm of constitutional law.

Examine the evolution of legal positivism and its impact on modern legal philosophy.

In this law literature review example, we undertake a comprehensive exploration of the evolution of legal positivism and its profound impact on modern legal philosophy. By tracing the historical development of legal positivism and its theoretical underpinnings, we elucidate the pivotal contributions of influential legal scholars and their enduring influence on contemporary legal thought.

Through a critical examination of the key tenets and criticisms of legal positivism, this example offers a nuanced analysis of its implications for modern legal philosophy, fostering a deeper understanding of the complexities inherent in legal theory. By integrating diverse scholarly perspectives and engaging with the intellectual discourse surrounding legal positivism, readers gain valuable insights into the multifaceted nature of legal philosophy and its enduring relevance in contemporary legal scholarship.

Furthermore, our exploration delves into the intersections of legal positivism with other prominent legal theories, providing readers with a comprehensive overview of the intellectual landscape within legal philosophy. By engaging with this law literature review example, individuals can construct informed and insightful evaluations of legal positivism's impact on modern legal thought, contributing to the scholarly discourse on the evolution of legal philosophy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can justdone.ai help me create a literature review on law, will the content created by justdone.ai be suitable for academic purposes, how does justdone.ai ensure the credibility of the literature review content, can justdone.ai assist in conducting a literature review on specific legal topics, does justdone.ai offer assistance in formatting and structuring the literature review, how can justdone.ai enhance the quality and depth of my literature review, join 1,000,000+ creators and professionals from trusted companies by choosing us, .css-1d7fhal{margin:0;font-family:"roboto","helvetica","arial",sans-serif;font-weight:400;font-size:1rem;line-height:1.5;letter-spacing:0.00938em;max-width:700px;}@media (min-width:0px){.css-1d7fhal{font-size:24px;font-weight:600;line-height:32px;font-family:'__inter_6eddd9','__inter_fallback_6eddd9';}}@media (min-width:744px){.css-1d7fhal{font-size:45px;font-weight:600;line-height:52px;font-family:'__inter_6eddd9','__inter_fallback_6eddd9';}} have a task that has no tool our chat knows how to do it.

It is unlikely that law researchers will be conducting systematic reviews, however you may need to conduct a literature review.

Applying systematic searching skills and techniques can also help shape and improve your research.

Below are some resources that can inform and guide law researchers with literature reviews and systematic research.

Key resources

- << Previous: Health sciences and medicine

- Next: Psychology >>

- Built environment

- Criminology

- Education (TESOL)

- Health sciences and medicine

- Social work

Contact your librarian

Faculty Librarian Law +61 7 5595 1550 [email protected]

Faculty of Law Manager, Law Library +61 7 5595 1520 [email protected]

- SCU Library

- Library guides

- Subject Guides

Legal Research Skills

- Databases and search operators

Key Australian legal databases

Keyword searching using search operators.

- Starting your research

- Journal articles

- Case citators

- Cases considering legislation

- Cases on a topic

- Cases defining words & phrases

- Legislation on a topic

- Finding commencement, amendment & reprint information

- Bills & extrinsic material

- International legal materials

- News & current awareness

- Referencing This link opens in a new window

- Need help? This link opens in a new window

Subscription databases

To be used exclusively for academic research only. Provides Australian case law (including the CaseBase case citator), legislation, journals, commentary (including a comprehensive legal dictionary & the Halsbury's legal encyclopaedia), and practical guidance modules. Some international content (NZ, UK, US, Canada & Hong Kong) is also included. View the Lexis+ Introductory Guide or Help pages to get started.

Free databases

All legal databases.

- Law databases A-Z list of all databases relevant to law at SCU. Includes multidisciplinary databases which may be useful for literature reviews.

When starting your research it's a good idea to get an overview of your topic or area of law by doing a keyword search.

Use Boolean and other advanced search operators to improve keyword search results. Below are the most common operators.

Tip: If you get the search operators wrong, the database probably won't alert you to the error; instead your search will find no results. If you are not sure, check the help section of individual databases to find the specific operators used.

- Next: Starting your research >>

- Last Updated: May 21, 2024 10:14 AM

- URL: https://libguides.scu.edu.au/legalresearchskills

Southern Cross University acknowledges and pays respect to the ancestors, Elders and descendants of the Lands upon which we meet and study. We are mindful that within and without the buildings, these Lands always were and always will be Aboriginal Land.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 26 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Writing a law school research paper or law review note

- Books and articles

Basics of Format & Content

Research papers are not as strictly structured as legal memos, briefs, and other documents that you've learned about in legal writing and drafting courses. For example, there is no prescribed content/format similar to to the Questions Presented, Brief Answers, etc. that you learned for a legal memo.

A general approach to thinking about the content of a research paper is:

- Introduction in which you give some background and a clear statement of your thesis

- Status quo -- what is the existing law and why is it a problem

- Proposals for change

See this blog post by Jonathan Burns , an IU McKinney alum, for more on basic content.

If you're writing for a law review or seminar, you should get formatting instructions regarding things like margins, font size, line spacing. If you don't, or if you're doing an independent study, here are some basic guidelines to follow:

- Times New Roman or similar, 12 pt font.

- Double spaced lines.

- One inch margins all around.

- Footnotes in academic Bluebook style (use the rules on the main white pages instead of the light blue pages at the front of the Bluebook).

- Footnotes in same font as text, 10 pt font.

- Use Roman numerals and/or letters on headings and subheadings or style the fonts so that the difference between headings and subheadings is clear.

- Page numbers in the footer, preferably centered, especially on first page. You could do bottom center on first page and then upper right in the header thereafter. Use the header and footer functions for this. If you don't know how to use headers and footers in Word, here is help: https://edu.gcfglobal.org/en/word2016/headers-and-footers/1/ .

Headings and subheadings

Research papers should have headings and subheadings. These help your reader follow your logic--and a logical structure is very important. Headings and subheadings can also help you keep your thoughts organized. Just don't overuse them--you don't want every paragaph to have a subheading.

Road map paragraph

Often, research papers will also include a paragraph at the end of the introduction that narrates the road map the paper will follow. Here is an example of this kind of paragraph:

"The section that follows [this introduction] sets the stage by recounting two scenarios from the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law, with discussion of the knowledge and implementation of accessibility features in online instructional materials. The next section provides an overview of various impairments and their effects on a user's experience of the online environment. Next is a review of the laws relevant to accessibility with attention to their potential application to online instruction, along with standards used to guide accessibility compliance. The article then explores the concept of universal design and its guiding principles, followed by a discussion of how to use the universal design principles to organize and better understand accessibility standards and practices. The final section briefly summarizes the discussion and encourages law librarians and professors to become knowledgeable and skilled in universal design for online materials to benefit all their students."

Table of Contents

A table of contents can also be helpful, though it's not necessary. If you add a table of contents to your papers, put it right at the beginning, before the introduction. Here's part of the table of contents for the same paper the paragraph above was taken from--it really just lays out the heading and subheadings with page numbers:

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Books and articles >>

- Last Updated: Jul 29, 2022 11:08 AM

- URL: https://law.indiana.libguides.com/c.php?g=1071346

Literature Reviews

- Types of reviews

- Getting started

Types of reviews and examples

Choosing a review type.

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

- Meta-analysis

- Systematized

Definition:

"A term used to describe a conventional overview of the literature, particularly when contrasted with a systematic review (Booth et al., 2012, p. 265).

Characteristics:

- Provides examination of recent or current literature on a wide range of subjects

- Varying levels of completeness / comprehensiveness, non-standardized methodology

- May or may not include comprehensive searching, quality assessment or critical appraisal

Mitchell, L. E., & Zajchowski, C. A. (2022). The history of air quality in Utah: A narrative review. Sustainability , 14 (15), 9653. doi.org/10.3390/su14159653

Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

"An assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue...using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 100).

- Assessment of what is already known about an issue

- Similar to a systematic review but within a time-constrained setting

- Typically employs methodological shortcuts, increasing risk of introducing bias, includes basic level of quality assessment

- Best suited for issues needing quick decisions and solutions (i.e., policy recommendations)

Learn more about the method:

Khangura, S., Konnyu, K., Cushman, R., Grimshaw, J., & Moher, D. (2012). Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic reviews, 1 (1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-10

Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries. (2021). Rapid Review Protocol .

Quarmby, S., Santos, G., & Mathias, M. (2019). Air quality strategies and technologies: A rapid review of the international evidence. Sustainability, 11 (10), 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102757

Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of the 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal , 26(2), 91-108. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Developed and refined by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), this review "map[s] out and categorize[s] existing literature on a particular topic, identifying gaps in research literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 97).

Although mapping reviews are sometimes called scoping reviews, the key difference is that mapping reviews focus on a review question, rather than a topic

Mapping reviews are "best used where a clear target for a more focused evidence product has not yet been identified" (Booth, 2016, p. 14)

Mapping review searches are often quick and are intended to provide a broad overview

Mapping reviews can take different approaches in what types of literature is focused on in the search

Cooper I. D. (2016). What is a "mapping study?". Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA , 104 (1), 76–78. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.1.013

Miake-Lye, I. M., Hempel, S., Shanman, R., & Shekelle, P. G. (2016). What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Systematic reviews, 5 (1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0204-x

Tainio, M., Andersen, Z. J., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Hu, L., De Nazelle, A., An, R., ... & de Sá, T. H. (2021). Air pollution, physical activity and health: A mapping review of the evidence. Environment international , 147 , 105954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105954

Booth, A. (2016). EVIDENT Guidance for Reviewing the Evidence: a compendium of methodological literature and websites . ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1562.9842 .

Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of the 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal , 26(2), 91-108. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

"A type of review that has as its primary objective the identification of the size and quality of research in a topic area in order to inform subsequent review" (Booth et al., 2012, p. 269).

- Main purpose is to map out and categorize existing literature, identify gaps in literature—great for informing policy-making