- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Why the Fight Over the Equal Rights Amendment Has Lasted Nearly a Century

By: Erin Blakemore

Updated: March 21, 2022 | Original: November 26, 2018

Should men and women have equal rights under the law in the United States? It’s a simple question with a seemingly simple solution—a Constitutional amendment that guarantees that equal rights shall not be abridged on the basis of sex. But as the thorny history of the Equal Rights Amendment shows, getting the nation to agree on whether to adopt such an amendment has proven endlessly complex.

It has taken nearly a century of fighting to come close to passing and ratifying the amendment. And though its adoption seems tantalizingly close , it could still be prevented by a quagmire of legal issues. Here’s why the Equal Rights Amendment has never been adopted—and how it became a controversial issue during the height of the feminist revolution of the 1970s thanks to an enormously influential political activist named Phyllis Schlafly .

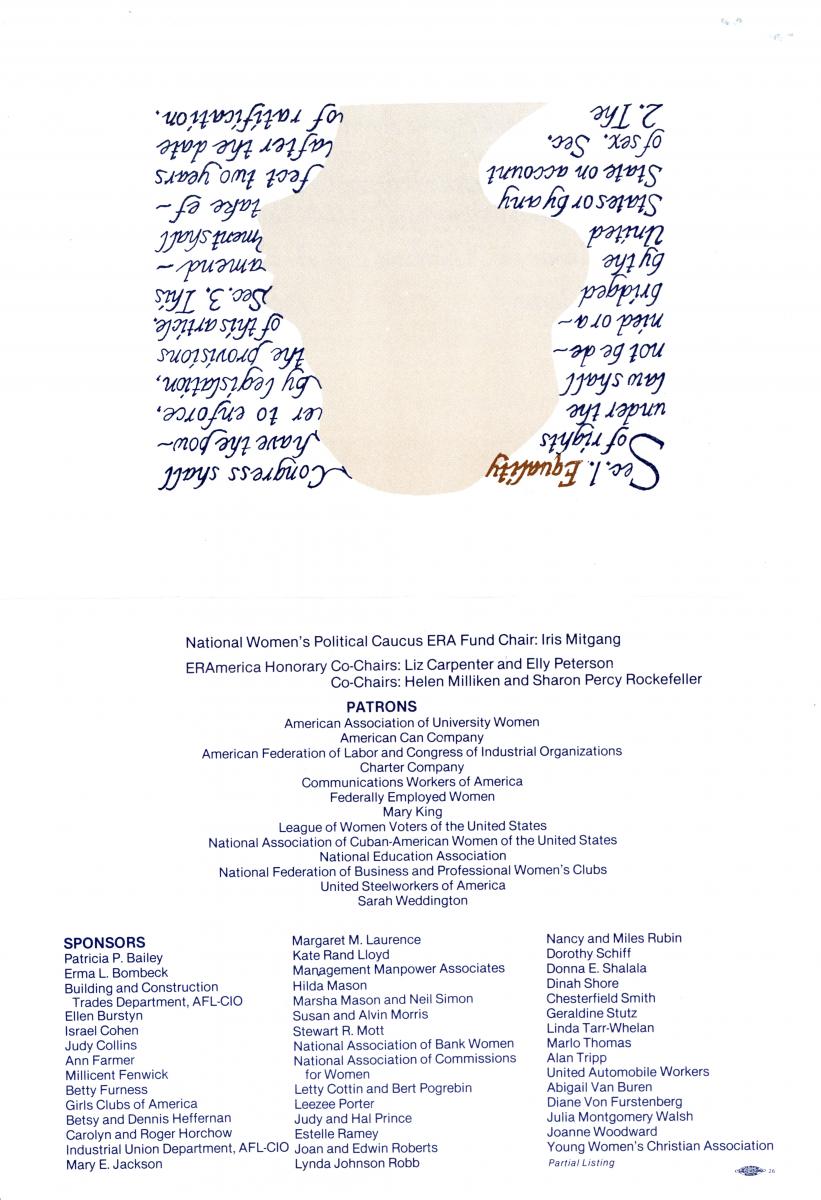

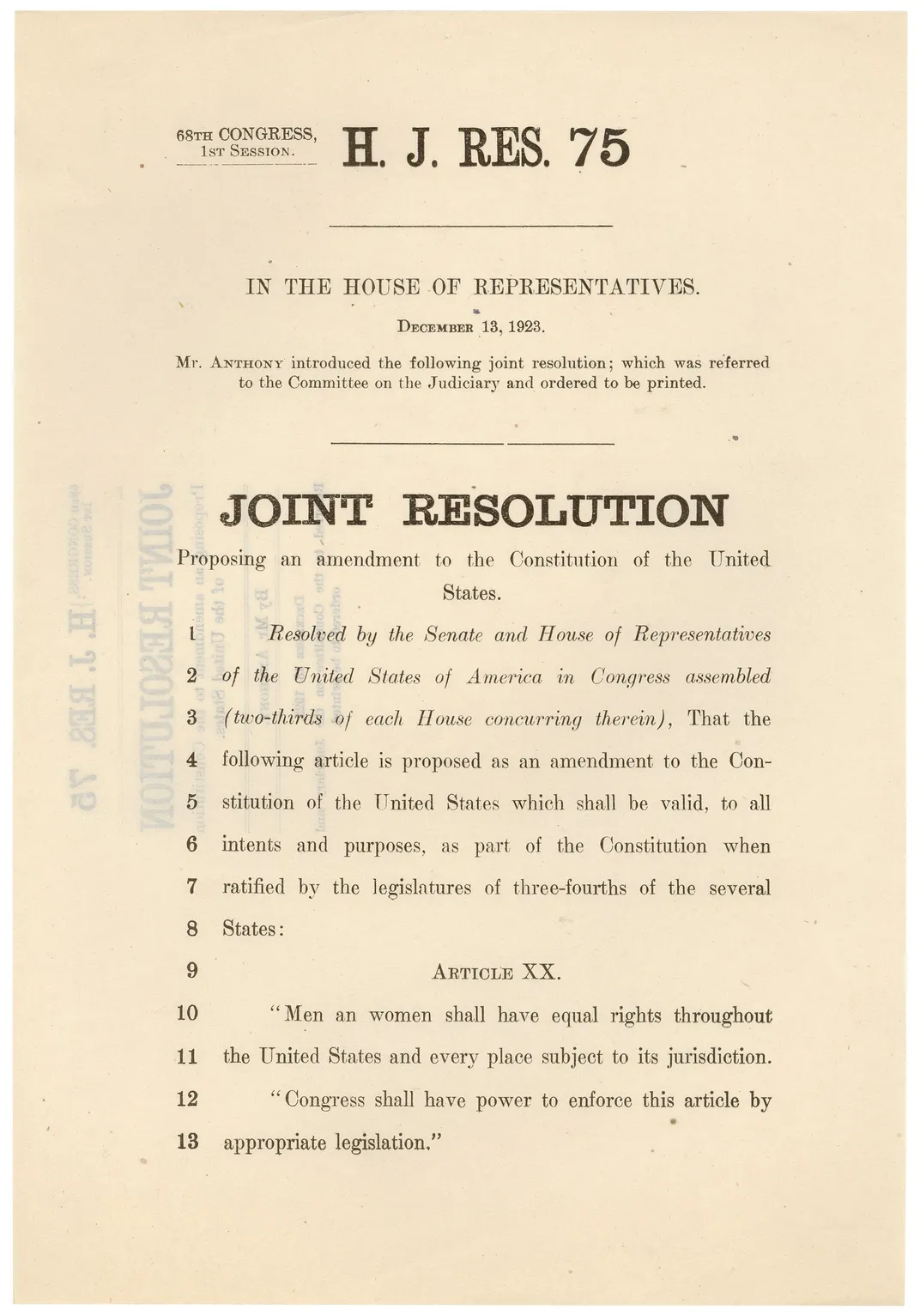

The Equal Rights Amendment originated with suffragist Alice Paul.

Though the amendment is a modern-day buzzword, its passage has been a goal of women’s rights advocates since even before the Nineteenth Amendment, which affirmed women’s right to vote, was passed in 1920. Suffragist Alice Paul proposed the first version of the amendment in 1923. She called it the Mott Amendment in honor of Lucretia Mott, one of the founding mothers of the American suffrage movement. Its wording was simple: “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

The wording may have been simple, but passing a constitutional amendment that guaranteed equal rights to women was anything but. Paul’s supporters proposed the amendment in every Congressional session between 1923 and the 1943, but it was never passed.

The proposed amendment underwent a change in wording in 1943.

Then, in 1943, she proposed a new amendment that used wording similar to the verbiage used in the Fourteenth Amendment. “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex,” it read. Now known as the Alice Paul Amendment, it was introduced in every session of congress between 1943 and 1972.

In an effort to appease working-class opponents who feared the amendment would undo their years of attempts to protect women from discrimination under labor law, advocates of the amendment tried to add additional language that ensured the new amendment wouldn’t remove any existing protections specifically for women. But the core of the proposed amendment remained the same through the 1970s.

Many presidents supported the ERA.

When second-wave feminism took hold in America, it ushered in a tidal wave of new support for the concept of constitutional equality between women and men. United States law increasingly called for equality of the sexes—the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , for example, banned sex-based employment discrimination. But advocates wanted to take equality a step further, and their goal looked to be within reach.

By 1970, notes the Congressional Research Service, “Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Nixon were all on record as having endorsed an equal rights amendment.”

Suddenly, it seemed, the ERA was having its moment. The National Organization of Women vigorously promoted the amendment. Women organized huge demonstrations in its favor. It worked: In 1972, both houses of Congress passed the amendment. It sailed through the House, picking up a 93.4 percent majority, and won a 91.3 percent majority in the Senate. Now it was up to the states to ratify it. It would need three fourths of the 50 states—38 in all—to become law. And it would need to be ratified within seven years thanks to an agreement by both parties.

Phyllis Schlafly led an energetic—and effective—opposition to the ERA.

But as the proposed amendment finally broke through, a potent anti-ERA movement was brewing. In the fall of 1972, Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative political activist, began to organize a resistance to the amendment. Schlafly had first heard of the amendment a year earlier when she was asked to participate in a debate held by a conservative group in Connecticut. But the founder of the Eagle Forum group sensed a much bigger movement in the making.

“Sensing a burgeoning conservative backlash to the social and cultural changes of the 1960s, Schlafly rightly recognized that the rumbling discontentment of religious conservatives could grow into a powerful political movement,” writes historian Neil J. Young. “Schlafly intended to lead the charge.”

Schlafly formed a group called STOP ERA, or “Stop Taking Our Privileges, Equal Rights Amendment.” She warned women that if equal rights were enshrined in the Constitution, the heterosexual world order would collapse. Morality would fall by the wayside and women would be at risk of losing their femininity and the opportunities presented by marriage, Schlafly said.

“Suddenly, everywhere we are afflicted with aggressive females on television talk shows yapping about how mistreated American women are, suggesting that marriage has put us in some kind of “slavery,” that housework is menial and degrading, and—perish the thought—that women are discriminated against,” she said in a 1972 speech that she published in her newsletter, The Phyllis Schlafly Report .

If the amendment passed, she wrote, women would be forced to go to war, would lose their right to child support and alimony, and society would fall apart. “The women’s libbers are radicals who are waging a total assault on the family, on marriage, and on children,” she said.

Schlafly had an uncanny knack for bringing together women of diverse religious and social backgrounds—and making them seem more numerous than they really were. She insisted on equal airtime to rebut the amendment and taught her followers to remind everyone they spoke to that they represented a “silent majority.” She also painted feminists and ERA advocates as foreign, unappealing and dangerous.

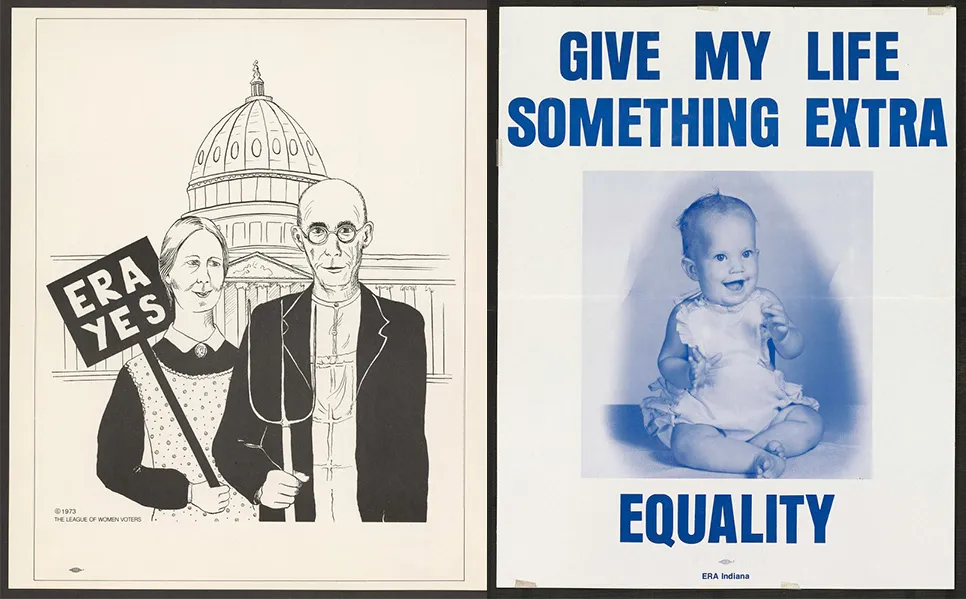

“Everywhere, ERA opponents took care to present themselves as feminine rather than feminist,” writes historian Marjorie J. Spruill. They adopted pink as their trademark color, aggressively distributed anti-ERA literature, and charmed legislators with baked goods and earnest pleas to the gender status quo.

Legislators began to turn their backs on the amendment.

Schlafly single handedly turned the ERA from a widely accepted concept into a culture war…and spooked legislators in the process. Though the amendment had been ratified by 22 states in its first year, the pace of ratification slowed. Then, states that had ratified the amendment began dropping out. Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, and Kentucky, and South Dakota all voted to rescind their prior support of the amendment.

After a court battle, a federal district court ruled that Idaho could rescind its support and that the lack of support in the state should be recognized, indicating that if other legal challenges were brought, they would likely fall in favor of the states that rescinded their adoptions of the amendment.

In 1978, recognizing that the adoption pace was slow, legislators extended the ratification period to 1982. But the amendment only had the support of 35 states. The amendment wasn’t dead, though.

50 years later: the amendment still has legs, but its future is unclear.

In 2017, Nevada ratified the ERA. In May 2018, Illinois followed. In 2020, Virginia became the final state to ratify the amendment . But it’s unclear what happens next. Since it expired decades ago, someone in Congress could give it a fresh start as a new bill, but it would then have to pass the House and the Senate and be re-ratified by all 38 states. If the additional states that ratified since 1982 are to be recognized, Congress would have to pass legislation that re-extends the deadline.

It’s unclear if the amendment could survive either attempt, or whether the ERA will eventually become law. Lawsuits would almost certainly accompany any concerted effort to make the ERA law by adopting the newer ratifications, and introducing the amendment anew risks having states that once supported the ERA fall off the “yes” list.

What is certain is that a simple sentence declaring equality of the sexes is, for now, a dream deferred. Its supporters have waited nearly a century for the amendment to pass, and even longer for equal rights. If the long afterlife of the Equal Rights Amendment is any indication, they’re willing to wait even longer.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Suggested Results

Antes de cambiar....

Esta página no está disponible en español

¿Le gustaría continuar en la página de inicio de Brennan Center en español?

al Brennan Center en inglés

al Brennan Center en español

Informed citizens are our democracy’s best defense.

We respect your privacy .

- Research & Reports

The Equal Rights Amendment Explained

Thirty-eight states have finally ratified the ERA, but whether its protections for women’s rights are actually added to the Constitution remains an open question.

- Equal Rights Amendment

On January 15, Virginia became the latest state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), a proposed amendment to the Constitution that guarantees equal rights for women. The measure emerged as a top legislative priority after Democrats took control of both houses of the Virginia General Assembly for the first time in two decades, leading to the election of the first female speaker of the state’s House of Delegates. It received bipartisan support in both chambers. This historic vote follows recent ratifications by Nevada in 2017 and Illinois in 2018 after four decades of inactivity.

The Constitution provides that amendments take effect when three-quarters of the states ratify them, putting the current threshold at 38 states. Virginia was the 38th state to ratify the ERA since Congress proposed it in 1972, technically pushing the ERA across that threshold. And yet, there are still hurdles in the ERA’s path. The ratification deadlines that Congress set after it approved the amendment have lapsed, and five states have acted to rescind their prior approval. These raise important questions, and now it is up to Congress, the courts, and the American people to resolve them.

What is the Equal Rights Amendment?

The Equal Rights Amendment was first drafted in 1923 by two leaders of the women’s suffrage movement, Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman. For women’s rights advocates, the ERA was the next logical step following the successful campaign to win access to the ballot through the adoption of the 19th Amendment. They believed that enshrining the principle of gender equality in our founding charter would help overcome many of the obstacles that kept women as second-class citizens.

While the text of the amendment has changed over the years, the gist of it has remained the same. The version approved by Congress in 1972 and sent to the states reads:

“Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex. The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.”

Beginning in 1923, lawmakers introduced the ERA in every session of Congress, but it made little progress until the 1970s. It didn’t help that for most of the twentieth century, Congress was comprised almost entirely of men. In the nearly five-decade span between 1922 and 1970, only 10 women served in the Senate, with no more than 2 serving at the same time. The picture was only slightly better in the House.

In 1970, a new class of women lawmakers — including Reps. Martha Griffiths (D-MO) and Shirley Chisholm (D-NY) — pressed to make the ERA a top legislative priority. They had to overcome the resistance of Rep. Emanuel Celler (D-NY), the powerful chairman of the House Judiciary Committee who had refused to hold a hearing on the ERA for over 30 years. Faced with increased pressure, Celler finally relented. In March 1972, the amendment passed both chambers of Congress with bipartisan support far exceeding the two-thirds majorities required by the Constitution. Congress promptly sent the proposed amendment to the states for ratification with a seven-year deadline.

Why wasn’t the ERA ratified by its original deadline?

Within a year, 30 of the necessary 38 states acted to ratify the ERA. But then momentum slowed as conservative activists allied with the emerging religious right launched a campaign to stop the amendment in its tracks. Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative lawyer and activist from Illinois who led the STOP ERA campaign, argued that the measure would lead to gender-neutral bathrooms, same-sex marriage, and women in military combat, among other things.

The opposition campaign was remarkably successful. Support for the ERA eroded, particularly among Republicans. Though the GOP was the first party to endorse the ERA back in 1940, GOP lawmakers cooled to the amendment, leading to a stalemate in the states.

By 1977, only 35 states had ratified the ERA. Though Congress voted to extend the ratification deadline by an additional three years, no new states signed on. Complicating matters further, lawmakers in five states — Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, Kentucky, and South Dakota — voted to rescind their earlier support.

In 1982, following the expiration of the extended deadline, most activists and lawmakers accepted the ERA’s defeat. But in the four decades since Congress first proposed the ERA, courts and legislatures have realized much of what the amendment was designed to accomplish. A significant portion of the credit goes to Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who as the founding director of the ACLU Women’s Rights Project found success in arguing for a jurisprudence of gender equality under the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

And yet, despite these dramatic and important gains for women’s rights, pervasive gender discrimination persists in the form of wage disparities, sexual harassment and violence, and unequal representation in the institutions of American democracy.

Why is there revived interest in the ERA today?

In recent years there has been a resurgence of women’s activism, from the Women’s March on Washington to the #MeToo Movement to the record number of women elected to Congress and state legislatures in 2018. Amid this renewed focus on issues of gender equality, lawmakers and advocacy organizations like the ERA Coalition have put the amendment back on the nation’s agenda.

The renewed push to adopt the ERA captured public attention in 2017, when Nevada became the first state to ratify the measure since 1977. A key ERA champion, State Sen. Pat Spearman, explained, “This is the right thing to do, it’s the right time to do it, and so we just ought to do it.”

In 2018, the Illinois legislature followed suit. “This is our generation’s chance to correct a long standing wrong,” argued Illinois State Rep. Steven Andersson, a Republican who helped shepherd the measure. With each new ratification, there has been increased GOP support for the ERA.

Proponents argue that adoption of the ERA can advance the cause of equality in the twenty-first century, but key questions remain. Julie Suk, a sociologist and legal scholar at the CUNY Graduate Center, has asked , “If ratified in the coming year, how should we construe the meaning of a constitutional amendment introduced almost a century ago and adopted half a century before full ratification?”

Over the last year, Brennan Center experts were among those to weigh in on the debate.

Jennifer Weiss-Wolf, the Brennan Center’s Women and Democracy Fellow, noted that the ERA would empower Congress “to enforce gender equity through legislation and, more generally, the creation of a social framework to formally acknowledge systemic biases that permeate and often limit women’s daily experiences.” And it would create consistency to address the patchwork ways gender and economic inequity are often addressed in our current laws. Among the “lingering legal and policy inequities the ERA would help rectify,” she identified the emerging issue of menstrual equity as a legal and policy issue “the ERA could further refine and bolster.”

Brennan Center Fellow Wilfred Codrington (also co-author of this piece) considered whether the ERA, framed as “an explicit, permanent constitutional provision outlawing gender discrimination,” is sufficient to meet the challenge of inequality today. “Lawmakers are justified in adopting the ERA,” Codrington argued, “even if it’s uncertain that the amendment would fully achieve its advocates’ desired ends.” But courts should also draw on their constitutional authority based in equity — defined as “recourse to principle of justice to correct or supplement the law” — which can reinforce their legal equality analysis and equip them to address “a broader spectrum of anti-discrimination cases … with greater nuance.”

John Kowal, the Brennan Center’s Vice President for Programs, explored the legal and procedural questions for Congress, the courts, and the American people arising out of the ERA’s surprising revival after a long period of dormancy. Should the push to ratify the 1972 version of the ERA fail on procedural grounds, Kowal also considered the advantages of starting the amendment process anew given the amendment’s strong base of public support. “When a powerful social movement with deep popular support takes up the goal of constitutional change,” he said, “history shows that this is a battle that can be won.”

What are the key legal challenges today?

Does Virginia’s vote to ratify the ERA mean it will be adopted as the 28th Amendment to the Constitution? The answer hinges on two procedural questions with no settled answer.

First, can Congress act now, nearly 48 years after first proposing the ERA, to waive the lapsed deadline? ERA supporters have long argued that just as Congress had the power to set a deadline, they have the power to lift one. Senate Joint Resolution 6 , a bipartisan measure sponsored by Sens. Ben Cardin (D-MD) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) which is currently pending in Congress, seeks to do just that. But while the ERA’s deadline was extended prior to the deadline, there is no precedent for waiving the deadline after its expiration.

Second, can states act to rescind their support of a constitutional amendment before it is finally ratified? Congress confronted this question twice, during the ratification of 14th and 15th Amendments in the years immediately following the Civil War. In each instance, Congress adopted resolutions declaring the amendments ratified, ignoring the purported state rescissions. But in 1980, a federal district court in Idaho ruled that the state’s rescission of the ERA was valid.

Who will decide these questions? Under a 1984 law, the Archivist of the United States is charged with issuing a formal certification after three-quarters of the states have ratified an amendment. When there has been doubt over the validity of an amendment, Congress has acted to declare it valid. This occurred most recently in 1992 when the states ratified the 27th Amendment , 203 years after Congress proposed it.

On January 8, the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) issued an opinion arguing that the deadline set by Congress is binding and that the ERA “is no longer pending before the States.” Notably, the opinion rejects the conclusion of the 1977 OLC opinion, which approved of the earlier extension of the ERA’s ratification deadline. In response, the National Archives and Records Administration has said that the archivist of the United States, Daniel Ferriero, will not certify Virginia’s ratification or add the ERA to the Constitution until a federal court issues an order. (Ferriero had previously accepted the ratifications from both Nevada and Illinois.)

But would the courts have a say in this controversy? In a 1939 case, the Supreme Court ruled that the question of whether an amendment has been ratified in a reasonable period of time is a “political question” best left in the hands of Congress, not the courts. If Congress acts to waive the deadline, would the courts continue to honor that precedent? How much weight would they give to the view of the American people, who strongly support the ERA according to recent polls ?

In sum, Virginia’s vote to ratify the ERA has spurred an important legal and policy debate. However the disputes over the amendment’s validity are resolved, it is clear is that the conversation around the ERA, an amendment that is already nearly a century in the making, is not likely to end in 2020.

Related Resources

The equal rights amendment's revival: questions for congress, the courts and the american people.

After a long period of dormancy, the campaign to ratify the ERA has sprung back to life. Are we just one state away from ratifying the Twenty-Eighth Amendment?

State-Level Equal Rights Amendments

Expert brief, the benefits of equity in the constitutional quest for equality, the era campaign and menstrual equity, equal rights amendment symposium 2018, informed citizens are democracy’s best defense.

The Surprising Political History of the Fight Against the Equal Rights Amendment

This post is in partnership with the History News Network , the website that puts the news into historical perspective. A version of the article below was originally published at HNN.

The fight over the Equal Rights Amendment is often framed as a classic fight between liberals and conservatives with liberals supporting the amendment to ensure gender equality and conservatives opposing the amendment to preserve traditional gender roles. But the history of the ERA before the state ratification battles of the 1970s shows that the fight over complete constitutional sexual equality did not always fall along strict political boundaries. As the dynamics of the early ERA conflict suggest, support for and opposition to the ERA are not positions that are fundamentally tied to either conservatism or liberalism. The ERA was first introduced into Congress in 1923, and Congress held several hearings on the amendment from the 1920s through the 1960s. Early ERA supporters as well as amendment opponents included liberals and conservatives alike. At its roots, the ERA conflict reflects a battle over the nature of American citizenship and not a typical political fight between liberals and conservatives.

The resurrection of the anti-ERA campaign effort in the mid-to-late 1940s is a prime example of how the original ERA conflict transcended typical political disputes of the early twentieth century. The social upheaval of World War II created a surge in support for the ERA , which alarmed several notable ERA critics, such as Mary Anderson, former head of the Women’s Bureau, Dorothy McAllister, former Director of the Women’s Division of the Democratic Party, Frieda Miller, the new head of the Women’s Bureau, Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor, and Lewis Hines, a leading member of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). In a September 1944 meeting, the distressed ERA opponents decided to create the National Committee to Defeat the Un-Equal Rights Amendment (NCDURA). This organization hoped to break the growing energy behind the ERA by centralizing the opposition forces and launching a coordinated counterattack on the amendment.

While founders of the NCDURA were predominantly prominent liberal ERA opponents, the organization actively worked with conservative amendment critics to squash the growing support for the ERA. When word reached the NCDURA’s leaders in April 1945 that the full House Judiciary Committee intended to report the ERA favorably, the organization reached out to “the all-powerful” conservative Representative Clarence J. Brown (R-OH), as one NCDURA official had put it, to help stall the amendment in the House. Once the full House Judiciary Committee reported the ERA favorably in July 1945, the leadership of the NCDURA used its budding connections with Representative Brown and the House Rules Committee to delay action on the amendment.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The NCDURA worked with conservatives once again when the ERA made progress in the Senate in the period following World War II. After the full Senate Judiciary Committee reported the ERA favorably in January 1946, the NCDURA began to coordinate efforts with conservative Republican Senator Robert Taft of Ohio. Senator Taft opposed the ERA because, he claimed, it would nullify various sex-based state laws that he believed protected women as mothers and potential mothers. In preparation for the July 1946 Senate floor debate on the ERA, the NCDURA worked with Senator Taft to make sure that every senator received a copy of the “Freund Statement,” an extensive essay by eminent legal scholar and longtime ERA opponent Paul Freund that outlined various arguments against the amendment. Before the debate, the NCDURA and its allies in the Senate also introduced into the Congressional Record an article denouncing the ERA written by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. The NCDURA’s work paid off. When the Senate voted on the ERA in July 1946, the amendment failed to receive the two-thirds majority of votes required for passage of a constitutional amendment.

In the final weeks of December 1946 and the early days of January 1947, it became clear to the NCDURA’s leaders that ERA supporters were not going to give up easily on their amendment. As a result, the NCDURA’s officials decided to continue to build relationships with prominent Republicans while creating a positive program that would provide an alternative measure for improving women’s status. In the months that followed, NCDURA leader Dorothy McAllister enlisted the help of influential Republican Party member Marion Martin, the founder of the National Federation of Women’s Republican Clubs, to encourage other important Republicans to oppose the amendment.

The NCDURA also began to work on a joint resolution that aimed to eliminate any possible harmful discrimination against women while reaffirming what ERA opponents believed to be equitable sex-based legal distinctions. The bill included two main objectives: declare a general national policy regarding sex discrimination and establish a presidential commission on the status of women. For the policy statement, the bill called for the elimination of distinctions on the basis of sex except for those that were “reasonably based on differences in physical structure, biological, or social function.” According to the bill’s backers, acceptable sex-based legal distinctions included maternity benefits for women only and placing the duty of combat service on men exclusively. The bill’s supporters also noted that the policy statement would only require immediate action by federal agencies; it would not necessitate immediate, compulsory action from the states. The purpose of the bill’s proposed presidential commission was to investigate sex-specific laws and make recommendations at the appropriate federal, state, and local levels.

In February 1947, the NCDURA had gained strong support for its bill from two influential conservative congressmembers: Senator Robert Taft of Ohio and Representative James Wadsworth of New York. While Senator Taft had started to help the anti-ERA effort in the mid-to-late 1940s, Representative Wadsworth had been a committed ERA opponent since the 1920s. Wadsworth supported the NCDURA’s bill because he believed that it would allow for the “orderly repeal” of unjust laws while preserving women’s right to special protection. Senator Taft and Representative Wadsworth introduced the Women’s Status Bill into Congress on Feb. 17, 1947. To bolster support for the bill, the NCDURA changed its name to the National Committee on the Status of Women (NCSW) in the spring months of 1947.

The Women’s Status Bill, which was commonly referred to as the Taft-Wadsworth Bill in the late 1940s, obtained a decent level of support from both Democrats and Republicans. Most importantly for ERA opponents, the bill successfully helped to subdue the pro-ERA impulse that had taken root during World War II because the bill provided an alternative measure for improving women’s status that promised a degree of equality while preserving the rationale for sex-specific legal treatment. The NCSW had versions of the Women’s Status Bill introduced into Congress every year until 1954. While the measure failed to pass Congress, it did provide the blueprint for what would become President John Kennedy’s Presidential Commission on the Status of Women, which was created in 1961.

Opposition to the ERA is not the only position that has appealed to both conservatives and liberals. The pro-ERA momentum that accelerated during World War II had helped the ERA gain an array of backers from across the political spectrum. That momentum slowed because of the ERA opposition work in the post-war years. Still, it is important to recognize the ways in which support for and opposition to the ERA have the potential to attract conservatives and liberals alike. By giving greater attention to how the struggle over the ERA has defied conventional categories of political ideology, we can gain a greater appreciation for the complexities embedded in the fight over the ERA and a better understanding for why the amendment has yet to be ratified. ERA opponents succeeded in stopping the amendment in the post-World War II era because they embraced an alternative approach for improving women’s status. That approach appealed to many conservatives and liberals because it allowed for a limited equality that upheld what they believed to be women’s natural right to special protection.

Rebecca de Wolf is the author of the forthcoming book Gendered Citizenship (University of Nebraska Press, October 2021), which examines the competing civic ideologies embedded in the original Equal Rights Amendment conflict. Her writing has also appeared in Frontiers , New America Weekly , and the Washington Post .

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

From Victory to Defeat: The Equal Rights Amendment

O n March 22, 1972, members of the increasingly vocal women’s movement celebrated the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) that, per Congress, had seven years to be ratified. The proposed amendment stated “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” Effectively lobbying by women’s right organizations led to large margins in both chambers of Congress in favor of the amendment to bar gender discrimination. As states quickly began to ratify the amendment, many American women looked forward to a future marked by greater equality. But their hopes were misplaced. After ten years, the ERA failed to receive backing by enough states to add it to the Constitution. How had an amendment that seemed to have wide support in public opinion polls gone down to defeat? The answer lay in part to a division among American women as to how the ERA would affect them—a division that predated the amendment’s passage through Congress.

The ERA had a long history. As far back as 1923, Alice Paul, the head of the National Women’s Party who had spearheaded an effort to secure passage of the Nineteenth Amendment giving women the right to vote, called on Congress and the American people to consider adding an equal rights amendment to the Constitution. Paul knew supporters of such an amendment faced a complicated fight, but she believed “there is nothing complicated about equality.” Congress, an almost exclusively male body, ignored the suggested addition for years. However, opposition to an equal rights amendment also came from working class women. Fearing an ERA would undermine protective legislation, such as a reduced workday for women (when the standard workday ran ten to twelve hours), working women gave limited support to the idea. Without a unified voice, even with greater political power stemming from the Nineteenth Amendment, women in favor of an ERA failed to attract significant backing for the legislation.

Things began to change after WWII. More women entered the workforce as men mobilized for World War II, and the demands of the postwar consumer culture made two salaries necessary for families. By the early 1960s, the pay gap between male and female workers took center stage. In 1963, at the urging of the Kennedy administration, Congress approved the Equal Pay Act, marking a significant step forward for women’s rights. Still, middle and working class women could not agree about whether or not an ERA was necessary. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 further underscored the shifting views about women in public life when the measure banned gender discrimination in the workplace. At the same time, the law undermined the validity of protective legislation for women.

In the 1960s, working-class women finally began to see the ERA as beneficial because, unlike laws passed by Congress, an amendment to the Constitution could not be undone. The founding of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966 provided a place for women from various backgrounds to fight for a common cause. The organization gave women a collective identity—an important step to achieving equality. NOW, along with the National Women’s Party and the Women’s Bureau of the Department of Labor, lobbied aggressively for the passage of the ERA when it went to the floor of Congress for a vote. When testifying in support of the ERA, women’s rights activist Gloria Steinem noted that women had “routinely suffer[ed] humiliation and injustice” and had been denied the right to “think of themselves as first-class citizens” for too long. The Senate voted 84 to 8 in favor of the amendment and the public polled strongly in favor of equal rights, suggesting that the amendment would get ratified quickly. So sure of approval were they that supporters of the amendment had not really prepared any steps to secure victory. They were shocked to find that within two years, the drive to ratification slowed down precipitously.

This drag happened because the Sixties, with their consciousness about civil rights, awakened conservative segments of the population to what seemed to be the dangers of an overly active government. In their view, traditional values no longer held sway, and the equality amendment along with the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973 foretold of a dire future for the nation. These concerns manifested themselves in the Stop-ERA Campaign, led by Phyllis Schlafly. As a long-time conservative, Schlafly spent her early public career warning of the dangers of liberalism and communism. Initially she was not particularly interested in the ERA. After further study, though, she concluded the ERA was another sign of the dangers of liberalism. Furthermore, it countered her faith-based view in women’s subordination to men.

Believing women had a place of “special privilege,” in American society, Schlafly questioned why women would “lower” themselves “to equal rights.” She spoke frequently about the “fraud” of the ERA. She also predicted women would be subject to the draft, alimony payments would no longer be standard in divorce settlements, and unisex toilets would become a reality. Her Stop-ERA campaign did not shift the public’s opinion about treating women more equitably, but it did cast doubt about the implications of the amendment. Uncertainty about its effects led to a significant decline in support for ratification. Supporters of the amendment increasingly found themselves trying to explain how the amendment would help women, not harm them.

After the allotted seven years, the ERA had passed in only thirty-five states. It needed three more to take effect. Congress then granted a three-year extension to secure ratification, and yet, no additional state approved the amendment. Still, the Equal Rights Amendment, and the debates surrounding its possible impact, did not disappear in 1982 when the extended window for ratification lapsed.

In the midst of the nation’s culture wars in the 1980s and 1990s, the role of women in America continued to be hotly contested. Members of Congress have repeatedly reintroduced the ERA since 1982. They even tried reframing the debate by calling it the Women’s Equality Amendment in 2007. As Carolyn Maloney (D-NY), a vocal supporter of the amendment, said in 2011, “We cannot ensure that women will be free of discrimination… as long as women are not universally defended under our Constitution…the equal rights of women are subject to interpretation of law.” Women today do have the protection of the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but questions of gender inequality remain as pervasive in American life today as they did on March 22, 1972.

Excellent article.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Policy

Women's Rights

Equal Rights Amendment

Three years after the ratification of the 19th amendment, the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was initially proposed in Congress in 1923 in an effort to secure full equality for women. It seeks to end the legal distinctions between men and women in terms of divorce, property, employment, and other matters. It failed to achieve ratification, but women gradually achieved greater equality through legal victories that continued the effort to expand rights, including the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which ultimately codified the right to vote for all women.

Explore photographs, textual, and other records related to the Equal Rights Amendment in the National Archives Catalog.

Research the Equal Rights Amendment

While many resources are available online for research, there are many more records to discover in National Archives’ research rooms across the country. The following records have been described at the Series and File Unit level, but have not yet been digitized. This list is not exhaustive; please consult our Catalog to browse more records, and contact the Reference Unit listed in each description for more information.

- Records Relating to the Equal Rights Amendment, 1970-1976

- Equal Rights Amendment Files, 1/1/1978 - 12/31/1980

From the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library

- View Women's Rights Digitized Materials

- Tumblr page on the ERA

From the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library

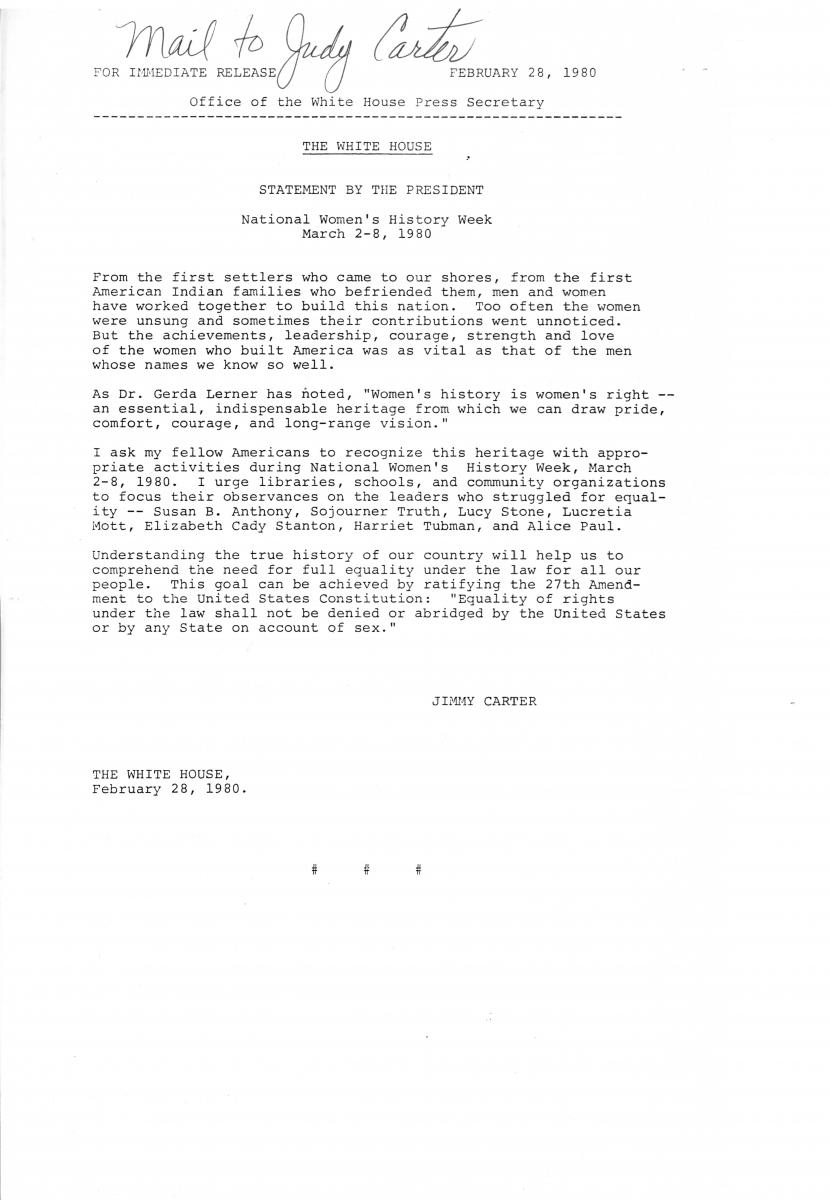

Carter administration as a pillar for era.

The Social Movement Era of the 1960s presented America with multiple opportunities for equality through legislation. One of these grassroots movements was that of the Women's Movement, which called for political (and social) reform on a number of women-related issues. The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), originally passed by Congress in 1972 with a deadline for ratification by March 1979, gained much support from women and men who felt social change could be garnered through legislation. 35 state legislatures approved the amendment for ratification, however 38 was the magic number needed. In 1978, Congress and President Carter extended the deadline to June 30, 1982.

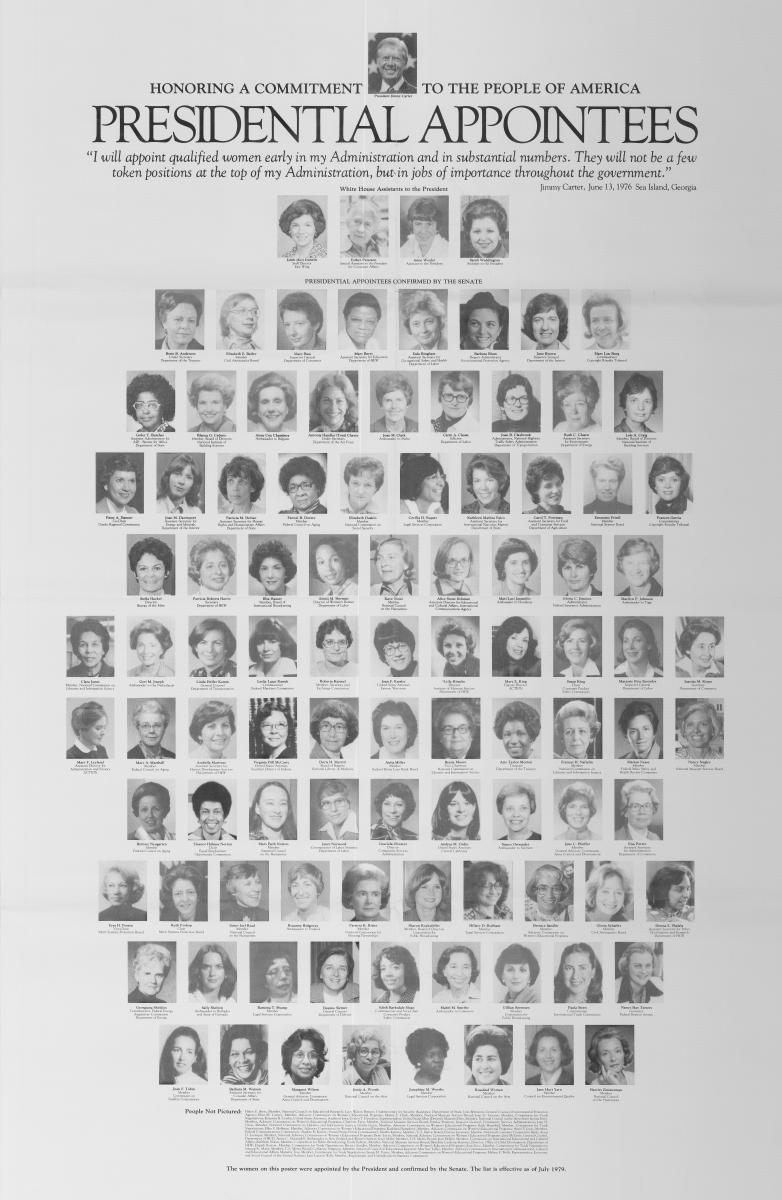

President Carter often urged the public to support and acknowledge the contributions of women to the nation’s heritage. He held monthly meeting with presidents of major women’s organizations, and reinforced his stance with signature on a message urging Americans to observe National Women’s History Week. Carter also demonstrated his support through his appointments of qualified women to advise him in a number of positions. Notable women that he felt would make major contributions towards the equality of women.

Some of these women included Sarah Weddington who represented "Jane Roe" in the landmark Roe v. Wade case, and served in the Office of the Assistant to the President for Women’s Affairs’/Office of the Assistant to the President for Public Liaison; Martha “Bunny” Mitchell who served as a link between President Carter and minority communities; Midge Costanza who was an advocate for gay and women's rights, and served in the Office of the Assistant to the President for Public Liaison; Judy Langford Carter who worked for the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, and served as Honorary Chair of the President’s Advisory Committee for Women.

Unfortunately, the Equal Rights Amendment did not meet the requirement to be made into law. However, work during the Carter Administration laid one of the many paved roads for the ratification of the ERA in the future.

-from the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum

Judy Langford Carter’s President’s Advisory Commission on Women Files, “Women’s Issues”. As the leader of the Interdepartmental Task Force on Women, Sarah Weddington, Special Assistant to President Jimmy Carter, produced a bimonthly newsletter called White House News on Women. It was mailed out to 14,000 recipients.

Sarah Weddington attached a memo to President Carter’s statement called, “The ERA: Full Partnership for Women,” letting Judy Langford Carter know, “ … this is essentially your version.”

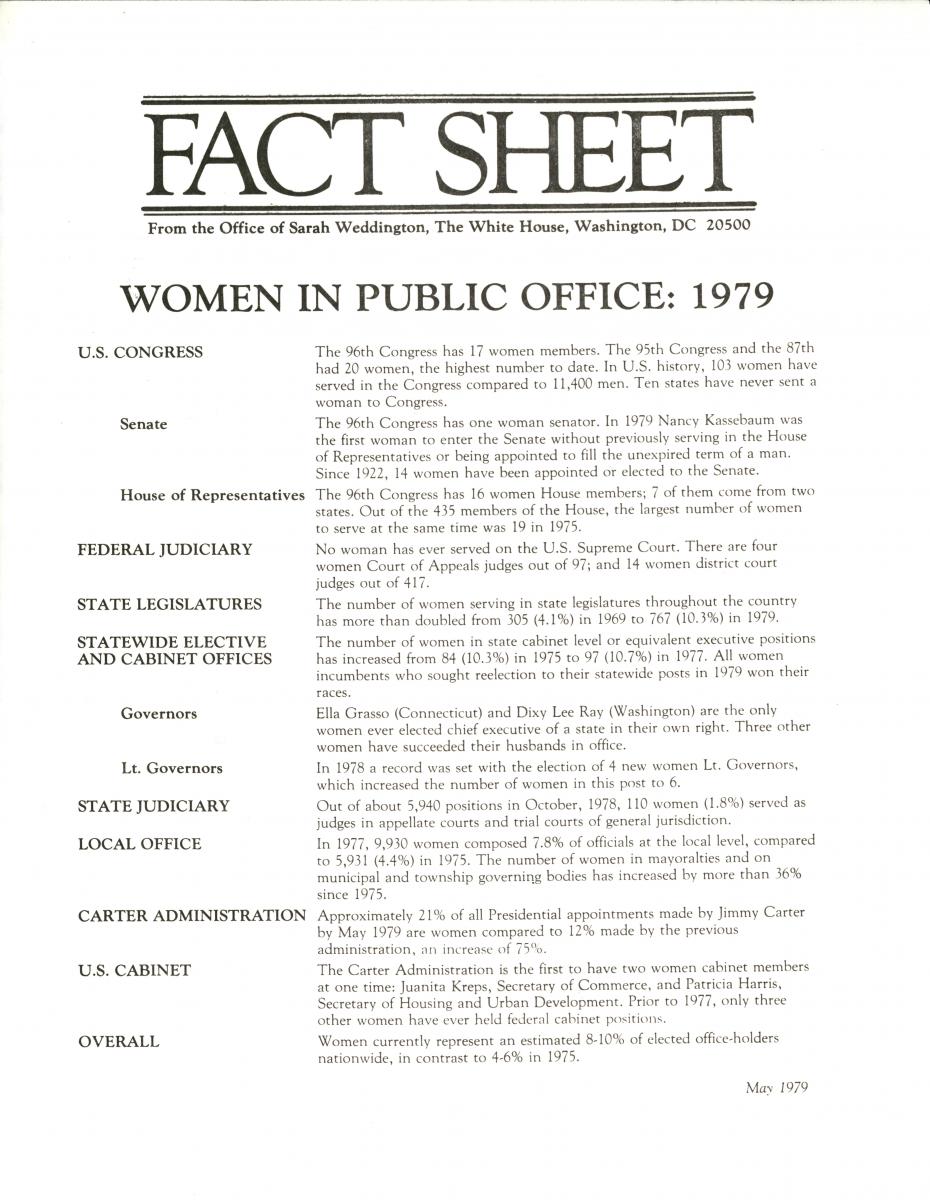

This fact sheet shows the number of women in public office in 1979. The U.S. House of Representatives had 16 women members, while the U.S. Senate had just one, Nancy Landon Kassebaum (R-Kansas).

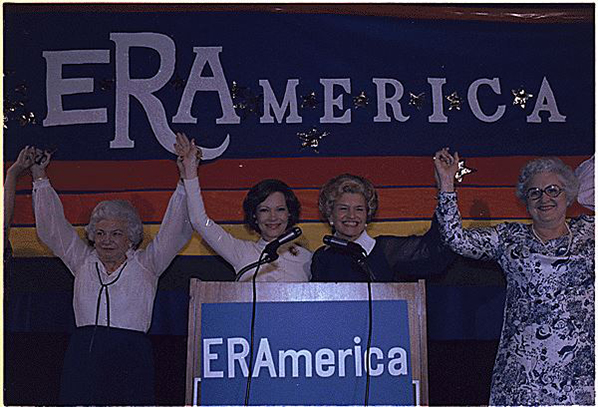

First Ladies Rosalynn Carter and Betty Ford served as co-chairs for “A National E.R.A. Evening,” to raise money for passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. The event, which took place on June 18, 1980, included a White House reception and dinner with President and Mrs. Carter.

President Carter issued a proclamation declaring August 26, 1978, Women’s Equality Day. The date marked the 58 th anniversary of the adoption of the 19 th Amendment. In it he stated, “I personally believe that ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment can be the single most important step in guaranteeing all Americans –both women and men—their rights under the United States Constitution. … In a society that is free, democratic, and humane, there can be no time limit on equality.”

On 2/28/80 President Carter met with a group of prominent women and signed a proclamation creating the first National Women’s History Week, which evolved into the present-day Women’s History Month. He also reiterated his support for ERA.

Did you know President Carter appointed more women to his administration than any of his predecessors? As of March 9, 1979, 268, or 18% of 1484 appointees, were women. This poster shows many of them.

- Carter Library Google Arts and Culture exhibit "Mrs. America: Rosalynn Carter and the ERA"

Educator Resources

- DocsTeach: Equal Rights Amendment

Articles, Blog posts, and Other Resources

Martha Griffiths and the Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment: The Most Popular Never-Ratified Amendment

“‘Equal Rights’ for Women: Wrong Then, Wrong Now”

- April 08, 2007

Introduction

Phyllis Schlafly (1924–2016) was one of the most renowned conservatives of the twentieth century. Married with children, Schlafly, who earned a law degree in 1978, was a candidate for office during the early Cold War and a grassroots organizer for conservative political candidate Barry Goldwater in 1964, at a time when few women worked outside the home. Schlafly’s greatest political accomplishment, however, was the defeat of the revitalized Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s. When the amendment was reintroduced in the early twenty-first century, Schlafly came out of retirement to comment.

Source: Phyllis Schlafly, “’Equal Rights” for Women: Wrong Then, Wrong Now,” Los Angeles Times , April 8, 2007.

Nearly twenty-five years after the defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment, feminists and their political supporters, who now control Congress, are back at it. Last month, the constitutional measure, now dubbed the Women’s Equality Amendment, was reintroduced in the Senate and House, and its prospects, according to one advocate, “are better now than they have been in a very, very long time.”

But ERA Retro is doomed.

The amendment, which was born around the time that women were given the right to vote, was first introduced in Congress in 1923. For nearly fifty years, all subsequent Congresses had the good judgment to leave it buried in committee.

In 1971, the women’s liberation movement burst on the scene and became the darling of the media. Its leaders demanded a gender-neutral society in which men and women would be treated exactly the same, no matter how reasonable it might be to respect differences between them. The amendment, which states that “equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex,” was the chosen vehicle to achieve this goal.

A radical feminist organization called the National Organization for Women stormed the halls of Congress and forced a vote on the Equal Rights Amendment. Only twenty-four members in the House, and eight in the Senate, voted against it. On March 22, 1972, Congress sent the amendment to the states, which had seven years to ratify it.

The Equal Rights Amendment had a righteous name and incredible momentum. Who would oppose equal rights for women and men? Support was bipartisan, with Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-MA) and then Alabama governor George Wallace among its endorsers. Three presidents—Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter—signed on. Within the first year, thirty of the thirty-eight states needed for ratification passed it, many without holding a hearing on the legislation. The Equal Rights Amendment was actively supported by most of the pushy women’s organizations, a consortium of thirty-three women’s magazines, numerous Hollywood celebrities, and virtually all the media.

The opposition was totally outmanned. We had no Rush Limbaughs, no Fox News, no “no-spin zone” to challenge the need for the amendment. We had no Internet, no e-mail, no fax machines to help rally an opposition.

But the Equal Rights Amendment was rejected. We kicked off our Stop ERA campaign, launched in February 1972, with an article I wrote: “What’s Wrong with Equal Rights for Women?” Over the next ten years, nearly one hundred issues of my Phyllis Schlafly Report were devoted to exposing the bad effects of the amendment. . . .

Throughout the 1970s, we presented legislators with our arguments. I testified at forty-one state hearings. Meanwhile, the pro-amendment crowd could not show how the ERA would confer any benefit on women, not even in employment, because employment laws were already gender-neutral.

In 1977, ERA advocates realized that they were approaching the seven-year time limit three states short of the thirty-eight needed for ratification, so they persuaded Congress to give them $5 million to stage a conference, called International Women’s Year, in Houston. The conference featured virtually every known feminist leader and received massive media coverage. But it backfired. When conference delegates voted for taxpayer funding of abortions and the entire gay rights agenda, Americans discovered the ERA’s hidden agenda.

A couple of months later, a reporter asked the governor of Missouri if he was for the ERA. “Do you mean the old ERA or the new ERA?” he replied. “I was for equal pay for equal work, but after those women went down to Houston and got tangled up with the abortionists and the lesbians, I can tell you ERA will never pass in the Show-Me State.”

With the expiration clock ticking—March 22, 1979—and ratification uncertain, feminists appealed to Carter and Congress for a time extension and won. The ratification deadline was extended to June 30, 1982.

The American people were so turned off by the extension that no additional state ever passed the ERA. In Idaho v. Freeman , a federal court ruled that the time extension was unconstitutional and that states could constitutionally withdraw their previous support. Five did.

The Supreme Court subsequently ruled that the lawsuit was “moot” because the ERA had not been ratified by either the original deadline or the extension.

ERA supporters repeatedly tried to revive the amendment, reintroducing it in Congress in 1983. But the House rejected it. They then tried to persuade individual states to pass the ERA as state constitutional amendments. They got nowhere.

The current plan to revive the amendment is so outrageously dishonest—for instance, backers say both previous time limits can be ignored, that prior court rulings are irrelevant, and that the previous state ratifications are still valid—that it’s a wonder anybody could argue it with a straight face. No matter its new name, the same text that has been voted down, again and again, will again be rejected by the American people.

Address to the Nation on Fifth Anniversary of September 11

Morse v. frederick, see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Check out our collection of primary source readers

Our Core Document Collection allows students to read history in the words of those who made it. Available in hard copy and for download.

History | Updated: January 15, 2020 | Originally Published: November 13, 2019

Why the Equal Rights Amendment Is Still Not Part of the Constitution

A brief history of the long battle to pass what would now be the 28th Amendment

:focal(677x338:678x339)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/0c/1d0c5e19-97f6-4bf1-930f-78d78ffcc00c/era-opener.jpg)

Lila Thulin

Former Associate Editor, Special Projects

Election Day in 2019 didn’t involve any high-profile House or Senate or Presidential seats up for the taking, but it had historic consequences nonetheless. In the Commonwealth of Virginia, voters handed Democrats control of both its statehouse chambers, and within a week of the 2020 legislative session, the new majority voted to make Virginia the 38th state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment (E.R.A.). Nearly a century after it was first suggested, the E.R.A. now stands a renewed chance of making it into the Constitution as the 28th Amendment.

What are the origins of the E.R.A.?

In 1921, the right for women to vote freshly obtained, suffragist Alice Paul asked her fellow women’s rights activists whether they wanted to rest on their laurels. The decision at hand, she said, was whether the National Woman’s Party would “furl its banner forever, or whether it shall fling it forth on a new battle front.”

Eventually, Paul and some fellow suffragists chose a new battle: a federal guarantee that the law would treat people equally regardless of their sex. Paul and pacifist lawyer Crystal Eastman, now considered the “founding mother of the ACLU,” drafted the “Lucretia Mott Amendment,” named after the 19th-century women’s rights activist. The original E.R.A. promised, “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/01/83014ede-5745-4656-8485-c7cf78b47082/gettyimages-615291916.jpg)

Paul’s insistence on a constitutional amendment proved to be controversial even in suffragist circles. Paul and other, like-minded activists believed an amendment would be the fastest path to social and economic parity for women, especially because their efforts to implement similar legislation on a state level hadn’t proved successful. But other prominent advocates objected, worried that the E.R.A. went too far and would eliminate hard-won labor protections for women workers. Florence Kelley , a suffragist and labor reformer, accused the N.W.P. of issuing “threats of a sex war.” And, as historian Allison Lange points out in the Washington Post , the N.W.P.’s new direction left behind women of color, who couldn’t exercise their newfound voting rights due to racially biased voter suppression laws.

Nevertheless, the N.W.P. persuaded Susan B. Anthony’s nephew, Republican Representative Daniel Anthony, Jr. of Kansas, and future vice president to Herbert Hoover Charles Curtis to introduce the earliest version of the E.R.A. to Congress in 1923. Despite repeated reintroduction, the E.R.A. got nowhere in the face of continued opposition from the labor and Progressive movements. The Republican Party added the E.R.A. to its platform in 1940, followed by the Democratic Party four years later. In 1943, as part of an effort to make the amendment more palatable to legislators, Paul rewrote the text to echo the “shall not be denied or abridged” wording of the 15th and 19th Amendments. Even rewritten, writes Harvard political scientist Jane Mansbridge in Why We Lost the ERA , the proposition made no headway until 1950, when it passed the Senate, saddled with a poison pill provision from Arizona Democrat Carl Hayden that E.R.A. advocates knew would nullify its impact.

Finally, amid the social upheaval, civil rights legislation and second-wave feminism of the 1960 and ’70s, the E.R.A. gained traction. In 1970, Democratic Rep. Martha Griffiths of Michigan brought the E.R.A. to the floor of the house by gathering signatures from her colleagues, bypassing a crucial pro-labor committee chair who’d blocked hearings for 20 years and earning her the nickname the “ Mother of the E.R.A.” The amendment won bipartisan support in both chambers; the House approved it in October 1971 and the Senate in March 1972. With Congress signed on, the next stage of the process to change the Constitution began: ratification by the states.

How does ratification work?

The Founding Fathers knew the Constitution wouldn’t age perfectly; in the Federalist Papers , James Madison forecasted, “Useful alterations will be suggested by experience.” The amendment process they devised was meant to provide a Goldilocks-like middle ground between “extreme facility, which would render the Constitution too mutable; and that extreme difficulty, which might perpetuate its discovered faults.” Article V of the Constitution lays out their solution: Amendments can be offered up for consideration by a two-thirds majority in the House and the Senate (or, although it’s never happened, a convention of two-thirds of the states). After passing that threshold, the would-be change has to be approved by three-fourths of the states to actually become part of the Constitution. States certify an amendment by passing it through their legislatures or a state convention, although that method has only been deployed once , for the amendment that repealed Prohibition. In Virginia, for instance, that means the Commonwealth’s Senate and House of Delegates must vote for it; unlike most legislation, amendment ratification does not require the governor’s signature.

Why didn’t the E.R.A. get ratified after Congress passed it?

In the first nine months after the E.R.A. was passed to the states, it racked up 22 ratifications in states from Hawaii to Kansas. That number swelled to 33 states by the end of 1974, and Gallup polls showed that almost three-fourths of Americans supported the E.R.A. But, says Mary Frances Berry, a University of Pennsylvania historian who wrote a book cataloguing the E.R.A.’s failure to launch, “The folks that were pushing it failed to notice that you needed states, not just popular opinion.”

The E.R.A. had the support of the majority of the public during the years it was up for ratification, according to Gallup polling . But that enthusiasm waned over time, and its political momentum stalled, thanks to the anti-E.R.A. organizing efforts of conservative, religious women like Illinois’ Phyllis Schlafly.

Schlafly’s organizations, STOP (an acronym for “Stop Taking Our Privileges”) ERA and the still-active conservative interest group Eagle Forum, warned that the E.R.A. was too broad, that it would eliminate any government distinctions between men and women. They circulated printouts of Senate Judiciary Chair Sam Ervin’s—popular for his handling of the Watergate investigation—invectives against it and trotted out socially conservative specters such as mandatory military service for women, unisex bathrooms, unrestricted abortions, women becoming Roman Catholic priests and same-sex marriage. STOP ERA members would lobby state governments, handing out homemade bread with the cutesy slogan, “Preserve Us From a Congressional Jam; Vote Against the E.R.A. Sham.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/f7/def7510a-183f-417e-99f7-a6afd3c1d357/gettyimages-514866234.jpg)

Feminism, Schlafly told the New York Times , was “an antifamily movement that is trying to make perversion acceptable as an alternate life-style,” and the E.R.A., she portended, would mean “coed everything—whether you like it or not.” Schlafly’s status-quo message stuck and swayed politicians in states that hadn’t yet ratified the E.R.A. like Florida, Illinois, Georgia and Virginia.

This anti-E.R.A. sentiment grew against the backdrop of a ticking clock: in keeping with custom, lawmakers gave the E.R.A. a seven-year deadline to obtain ratification. In the early 70s, the arbitrary time limit—a tradition that began with political maneuvering around the 18th amendment (Prohibition)—had unsettled some. “There is a group of women who are so nervous about this amendment that they feel there should be unlimited time,” said Griffiths, the E.R.A.’s sponsor in the House. “Personally, I have no fears but that this amendment will be ratified in my judgment as quickly as was the 18-year-old vote [the recently passed 26th Amendment]. I think it is perfectly proper to have the 7-year statute so that it should not be hanging over our heads forever. But I may say I think it will be ratified almost immediately.”

Many of Griffiths’ peers shared her optimism. “I don’t think that they projected that [ratification] would be a problem,” says University of Pennsylvania historian Berry. “I don’t think they realized how hard it was going to be.”

As 1979 approached and the E.R.A. remained three states short, the Democrat-controlled Congress extended that deadline to 1982, but to no avail—not a single additional state signed on to the amendment. At Schlafly’s victory party on July 1, thrown the day after the clock ran out for her legislative nemesis , the band played “Ding Dong, the Witch Is Dead.”

Hasn’t the window for ratification passed?

Yes, the 1982 deadline is long gone, but legal scholars have argued that that’s reversible. The William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law makes the case that Congress can re-open the ratification window, pointing out that not all amendments (like the 19th) include a time limit and that Congress extended the deadline once before. While the Supreme Court previously ruled that amendments must be ratified within a “sufficiently contemporaneous” time, it also batted the responsibility of defining that window to Congress, as a 2018 Congressional Research Service report outlines. The most recent amendment, the 27th, was adopted in 1992 with the Department of Justice’s seal of approval—it was written by James Madison in 1789 as part of the Bill of Rights and had spent 203 years in limbo. (The 27th Amendment prohibits members of Congress from giving themselves a pay raise right before an election.)

While this precedent seems favorable, it’s worth noting that five states—Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, Kentucky and South Dakota—rescinded their early ratification of the E.R.A. as socially conservative anti-E.R.A. arguments gained ground. Legal scholars debate the validity of that rescission, as there is historic precedent implying that ratification is binding: Ohio and New Jersey tried to take back their approval of the 14th Amendment in 1868, but despite this retraction, the official documents still include them on his list of ratifying states. Robinson Woodward-Burns, a political scientist at Howard University, points out for the Washington Post that a similar situation cropped up with the 15th and 19th Amendments, “suggesting that states cannot withdraw ratification.” In 1939, the Supreme Court declared that ratification reversal “should be regarded as a political question” and therefore, out of its purview.

Until January 2020, the E.R.A. remained in the company of other passed-but-never-fully-ratified “zombie amendments,” to curb a phrase from NPR’s Ron Elving . Among them are amendments granting the District of Columbia voting representation in Congress (passed by Congress in 1978 and ratified by 16 states before it expired ), an 1810 amendment prohibiting American citizens from receiving titles of nobility from a foreign government (sorry Duchess Meghan!) and the the Child Labor Amendment (passed by Congress in 1937 and ratified by 28 states). The Corwin Amendment, a compromise measure passed in the leadup to the Civil War and supported by Abraham Lincoln , is a more sinister, still-technically-lingering amendment. It would have permanently barred the federal government from abolishing slavery.

What happened in the years since the 1982 deadline passed?

The E.R.A. didn’t altogether fade from policymakers’ consciousness after its defeat. From the ‘90s until now, congresswomen and men routinely introduced bills to disregard the ratification window or resubmit the amendment (or an updated version that would add the word “woman” to the Constitution) to the states. No state had approved the E.R.A. in 40 years when, in 2017, Nevada’s newly Democratic legislature ratified the E.R.A. The next year, Schlafly’s home state of Illinois followed suit . On January 15, 2020, the Virginia General Assembly approved the E.R.A. , setting up a heated constitutional debate .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/d4/70d45305-4dba-40b4-9a2f-39d14b46c91b/screen_shot_2019-11-13_at_23341_pm.png)

Virginia has come tantalizingly close to ratification before. In 1982, the Commonwealth’s last chance to vote for the E.R.A. before the deadline, a state senator hopped on a plane out of town, conveniently missing the roll call and evading the 20-20 tie that would have secured a pro-E.R.A. tiebreak vote from the lieutenant governor. Earlier in 2019, the E.R.A. passed the Virginia Senate but was stymied in a House subcommittee .

What would come next? “We fully anticipate that there will be a Supreme Court decision involved,” Krista Niles, the outreach and civic engagement director at the Alice Paul Institute, told the New York Times . But the Supreme Court’s scope of authority over amendments is nebulous based on precedent, writes Robert Black for the National Constitution Center.

What would the adoption of the E.R.A. mean today?

Women’s rights have come a long way since Alice Paul first proposed the E.R.A. States have enacted their own laws broadly prohibiting sex-based discrimination, and thanks to a feminist legal campaign led by Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the ACLU , the Supreme Court recognized sex discrimination as violating the equal protection clauses of the 5th and 14th Amendments in cases liked Frontiero v. Richardson and United States v. Virginia . Due to this progress, the E.R.A.’s ramifications wouldn’t feel quite as revolutionary today, says Berry, but “it would still have some impact, because it is much better to have a basis for one’s rights in the Constitution.”

Current sex-discrimination law rests on judicial interpretations of equal protection, which can vary by ideology . If ratified, the E.R.A. would give policymakers a two-year buffer period to bring existing laws into compliance, and after that, policies that differentiated by sex would be “permitted only when they are absolutely necessary and there really is no sex-neutral alternative,” explains Martha Davis, a law professor at Northeastern School of Law. It would likely still be permissible, she says, to shape laws differently to address physical characteristics that are linked to sex assigned at birth, like breastfeeding or pregnancy, and privacy qualms like separate-sex bathrooms.

Other laws, like the mandated draft for only men or immigration policy that differs based on a parent’s gender, might change , and conservative opponents have argued that it could impact welfare programs aimed at women and children.

Now, one century after the 19th Amendment took effect, Virginia has approved the legislation Alice Paul saw as suffrage's successor, and the 97-year-old amendment's future is up to Congress and the courts.

Editor's Note, January 15, 2020: This story has been updated to include Virginia's 2020 vote to ratify the E.R.A.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Lila Thulin | | READ MORE

Lila Thulin is the former associate web editor, special projects, for Smithsonian magazine and covers a range of subjects from women's history to medicine.

Phyllis Schlafly and the Debate over the Equal Rights Amendment

Written by: Gregory L. Schneider, Emporia State University

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the causes and effects of continuing policy debates about the role of the federal government over time

- Explain how and why various groups responded to calls for the expansion of civil rights from 1960 to 1980

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative with The Birth Control Pill Narrative and the National Organization for Women (NOW), Bill of Rights, 1968 Primary Source while discussing the various civil rights movements occurring during the 1970s to specifically target the issues of women at the time.

In 1973, feminist Betty Friedan debated conservative Phyllis Schlafly at Illinois State University in 1973. Friedan, who disliked Schlafly’s opposition to an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the Constitution, said, “I consider you a traitor to your sex.” Schlafly countered by saying that Friedan and her allies were “intemperate, agitating proponents of ERA. . . so intolerant of the views of other people.” Schlafly antagonized liberal and feminist women in the audience with comments like: “I’d like to thank my husband for allowing me to speak here tonight.”

Friedan and Schlafly had much in common: they were both well educated, married with children, and passionate about their respective side in the fight over the ERA. The amendment simply stated: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any other State on account of sex.” But it was Schlafly whose opposition prevailed in the fight and who strengthened the position of traditional conservatism as a result.

Phyllis Schlafly protesting outside the White House against the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in 1977.

Phyllis Stewart was born in St. Louis and raised during the Great Depression when her mother had to support the family because of her father’s inability to find work. A bright and hardworking student, Stewart graduated from Washington University in St. Louis in 1944, working at a World War II ammunition factory to help defray college costs. She also received an M.A. in government from Radcliffe College, then the sister school of Harvard University. She later received a law degree from Washington University in 1978.

After the war, Stewart worked for a year at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative pro-business organization in Washington, DC. She left to become involved in a political campaign in St. Louis and eventually ran for Congress herself, and lost, as the Republican candidate in a heavily Democratic district. In 1949, she married Fred Schlafly, an attorney for the Olin Corporation, became active in Republican Party politics, and was a delegate to every GOP convention from 1952 until 2016. She had six children and attended Washington University Law School at night. A strong Roman Catholic and anti-communist, she founded the Cardinal Mindszenty Foundation (named after an imprisoned Hungarian prelate) to educate Americans about the communist threat to religion.

Schlafly gained national attention with the publication of her first book, A Choice, Not an Echo (1964), which attacked the moderate East Coast leaders in the Republican Party and supported the campaign of conservative Arizona senator Barry Goldwater when many party leaders did not. The slim volume of approximately 120 pages was distributed by her own publishing house and sold more than three million copies, catapulting Schlafly to fame within the emerging conservative movement (she used the royalties from the book to fund her children’s college educations). She now had a platform for her views and published a monthly four-page pamphlet known as The Phyllis Schlafly Report, distributing it to thousands of subscribers, many of them women she had cultivated in her role as a member (and later vice president) of the National Federation of Republican Women.

Schlafly’s main interests as a writer and analyst were defense policy and nuclear weapons, and she co-wrote several books about these with former Admiral Chester Ward. She was very critical of Richard Nixon’s policy of détente, the lessening of tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, as well as of Nixon’s opening relations with Mao Zedong’s China in 1972. She thought the communists could not be trusted to abide by agreements being reached on nuclear weapons and improved relations.

One of the issues that did not interest Schlafly much at all was the feminist movement, which had reemerged during the protest culture of the 1960s. Betty Friedan had helped shape feminism in the 1960s by the publication of her book, The Feminine Mystique (1963), which discussed how the domestic sphere of motherhood, for educated women like herself, was akin to a “cultural concentration camp.” In 1964, Friedan helped form the National Organization for Women (NOW) and fought for equity issues like equal pay for equal work and women’s opportunities to have careers in the professions, such as medicine, higher education, and law. But the cultural revolutions of the 1960s, from civil rights to the anti-Vietnam War protests, reshaped feminist responses and radicalized women, who now saw their concerns linked to political issues in a very personal way.

Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique helped galvanize the feminist movement in the 1960s.

Even as members of protest movements, women often found themselves treated as second-class citizens, with very few in leadership positions and most serving as secretaries and romantic partners to the male leaders of the movement. Women began to discuss their thoughts about these issues, and the resulting consciousness-raising sessions led to an explosion of feminist organizations in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Cultural and radical feminists bore no hostility toward the economic and political concerns of NOW, but they pushed the movement further, urging control over their own reproductive decisions and their sexuality. They also believed men and women were equally competent and should be treated as equals in the workplace and in their freedom to make personal decisions.

The feminist movement resurrected the ERA (initially proposed in the 1920s) and moved for its adoption. Congress passed it in 1971 and, by early 1973, 30 states had ratified it, leaving it only eight states short of adoption. Moreover, several states had also legalized abortion and, in 1973, the Supreme Court legalized abortion nationwide in a 7-2 vote in the case known as Roe v. Wade . Then Phyllis Schlafly entered the debate, publishing “What’s Wrong with Equal Rights for Women?” in the February 1972 issue of The Phyllis Schlafly Report.

Schlafly’s argument was that women’s rights were already protected under the Constitution and that the ERA would undermine the family, “the basic unit of society, which is ingrained in the laws and customs of our Judeo-Christian civilization”. The modern American woman would lose the protection of father and husband and the “Christian tradition of chivalry,” which supported the family and shielded women in the case of divorce or separation. Schlafly also attacked the ERA as undermining the protections that women already possessed and that the ERA would leave women vulnerable to the military draft. Although she supported equity for women in careers and pay, she also defended motherhood and the home in her essay. She also later claimed the ERA would lead to coed bathrooms and the promotion of homosexual marriage.

Buttons like this were worn by opponents of the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s.

Schlafly’s essay led directly to the formation of a movement of Christian evangelicals, Mormons, Catholics, and other traditional groups to fight against the ERA in an organization called STOP ERA (Stop Taking Our Privileges-ERA), led by Schlafly. ERA supporters were often white, middle-class, secular, and well educated; they tended to be single or, if married, in one of the professions. They were also divided among many feminist organizations, such as NOW and others dedicated to securing passage of the amendment. STOP ERA members were married women with children, religious, middle class, and older, and they saw links between attacks on religion in the courts and the feminist movement as threats to motherhood and the home. Democrats and Republicans, including Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, as well as celebrities and the media, supported the ERA, and making headway against it was an uphill climb, but Schlafly’s organization and dedication to the cause prevailed. Schlafly linked the ERA fight to the fight against abortion and drew support from the emergence of a religious right at the grassroots level in the 1970s.

Schlafly took the lead in challenging feminists in debates and in making appearances in the national media, while her grassroots supporters lobbied at the state level, often bringing cookies to appeal to the men who dominated state legislatures. Five states proved crucial battlegrounds: Florida, Missouri, Illinois, Oklahoma, and North Carolina. In each state, the STOP ERA forces prevailed. Even after a five-year extension for ratification was allowed by Congress, Illinois’s decision not to ratify the amendment in 1982 effectively killed the effort for passage. By that time, Ronald Reagan was in the White House and the conservative movement was at its peak, with the majority of STOP ERA members, including Schlafly, giving their full support to the White House and its policies.

After the defeat of the ERA, when Schlafly came under verbal and physical assault from supporters of the amendment, she converted STOP ERA into a pro-family, traditionalist organization named Eagle Forum. As one of the leaders of the rising conservative movement of the 1960s and 1970s, she remained an active Republican and conservative activist for the rest of her life. The STOP ERA fight was one of the main reasons conservatism as an ideology became crucial to Republican politics. The grassroots activists in the STOP ERA fight remained committed to the conservative cause and to traditionalism within American society.

Review Questions

1. Phyllis Schlafly began her grassroots activism in the 1950s with which of the following organizations?

- Young Americans for Freedom

- Cardinal Mindszenty Foundation

- Eagle Forum

2. In her early political career, Phyllis Schlafly was most interested in which issue, on which she co-wrote many books?

- National defense policy

- Separation of church and state

- America’s stance toward Red China

- Republican politics

3. Phyllis Schlafly’s activism helped lead to the emergence of which contributing force in Ronald Reagan’s 1980 electoral victory?

- Neo-conservatism

- Anti-communism

- The Religious Right

4. The failure of which state to ratify it guaranteed the rejection of the Equal Rights Amendment becoming part of the U.S. Constitution?

5. The origins of the Equal Rights Amendment trace back to the

- creation of the National Organization for Women

- publication of The Feminine Mystique

- work of women’s suffragists in the 1920s

- ideals espoused by the civil rights movement

6. The ideals of the women’s rights movement of the 1960s were similar to those of all the following groups except

- anti-Vietnam War protestors

- civil rights activists

- the Eagle Forum

- National Organization for Women

Free Response Questions

- Explain the motivations for the emergence of feminism in the 1960s.

- Describe the threat Phyllis Schlafly believed the Equal Rights Amendment posed to the lives and status of women.

AP Practice Questions