An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.7(2); 2020 Mar

Barriers to practicing patient advocacy in healthcare setting

Comfort nsiah.

1 School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast Ghana

Mate Siakwa

Jerry p. k. ninnoni.

To explore barriers to practicing patient advocacy in healthcare setting.

This study used a qualitative research approach to arrive at the study result.

Twenty‐five Registered Nurses were purposively selected. Semi‐structured interviews were used to collect data and analysed using qualitative content analysis.

The main theme identified was lack of cooperation between healthcare team, care recipients and the health institution which included the health institution and work environment, ineffective communication and interpersonal relationship, patients' family, religious and cultural beliefs. Unsuccessful advocacy resulted in increased complications, death, negative consequence on the health institution and nursing as a profession. This study has significantly created awareness of the need for an improved patient advocacy to enhance the quality and safety in the care of patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

Evidence has shown that health facility's goal of providing quality care of patients cannot succeed in the absence of nursing advocacy (Black, 2011 ; Nsiah, 2016 ).

Nsiah, Siakwa, and Ninnoni ( 2019 ) described patient advocacy being the patient's voice, acting on behalf of a patient to ensure that his or her needs are met. Many nurses advocate for patients across the globe due to its advantages and ability to increase recovery rate (Abbaszadeh, Borhani, & Motamed‐Jahromi, 2013 ; Black, 2011 ; Thacker, 2008 ).

For instance, Attree ( 2007 ) was of the view that professional nursing is about advocating for patients to reduce possible complications that impede speedy recovery. Evidence suggests limited practice of advocacy by nurses, leading to unnecessary health complications and death in some Ghanaian healthcare facilities (Abekah‐Nkrumah, 2010 ; Ghana News Agency, 2015 ; Norman, Aikins, Binka, & Nyarko, 2012 ).

Yet, the specific reasons that hinder Registered Nurses from advocating for patients in the Ghanaian context are not clear in the literature. This study outcome will provide empirical evidence with respect to specific barriers to successful patient advocacy in the healthcare setting. It will further contribute significantly to creating the awareness and understanding the need to enhance successful patient advocacy for improved safety and quality care of patients.

2. BACKGROUND

Patient advocacy enhances quality of patient care, yet most nurses are limited in their ability to carry out this role. Research has revealed powerlessness, lack of knowledge in law and nursing ethics, limited support for nurses and physicians leading in hospitals as hindrances to nursing advocacy in the Iranian context (Negarandeh, Oskouie, Ahmadi, Nikravesh, & Hallberg, 2006 ). Negarandeh and co‐workers as cite in Nsiah ( 2016 ) further noted the healthcare setting as the greatest source of hindrance to patient advocacy due to the fact that advocating for patients basically contradicted the cultural systems in the hospital. The nurses also lacked autonomy in the hospital environment.

In addition, the absence of guidelines, fear of making mistakes and its unknown consequences prohibited some nurses from advocating for patients (Vaartio, Leino‐Kilpi, Salanterä, & Suominen, 2006 ). A study conducted by Black ( 2011 ) in southern Nevada indicated wrong labelling and vindications by employer, coupled with possibility of losing one's job served as barrier during patient advocacy.

On the contrary, as cited by Nsiah ( 2016 ), Abbaszadeh et al. ( 2013 ) stated that fear of job loss was not a hindrance to nursing advocacy in Iran. Rather, these authors noted limited educational programmes and less work experience as the main challenge. Thacker ( 2008 ), however, argued that it is rather the working environment that greatly determined whether or not a nurse will advocate for his or her patient.

Furthermore, Hanks ( 2010 ) was of the view that individual characteristics of nurses such as self‐esteem, assertiveness and personal values hindered their ability and desire to advocate. Similar to this study finding, Davis and Konishi ( 2007 ) as revealed by Nsiah ( 2016 ), found that cultural beliefs hindered nurses from embarking on advocacy for patients in Japan. Meanwhile, Bu and Jezewski ( 2007 ) considered limited legal support for nurses as key blockade to advocacy. This finding implies that barriers confronting nurses who advocate for patients differ from one country and health facility to another. Nurses' context of practice greatly influenced their ability to advocate for patients.

Currently, there exist knowledge gap with respect to the exact cause of nurses' inability to advocate for patients in most Ghanaian hospitals (Nsiah et al., 2019 ). However, the negative consequences that result from lack of patient advocacy are said to include prolonged patient recovery and death which contradicts health institution's goal of saving lives (Black, 2011 ; Nsiah, 2016 ; Nsiah et al., 2019 ). Hence, the need to research into barriers hinders nurses from advocating for patients in the healthcare setting in the Ghanaian context. This study aimed at answering the following research question: What barriers do Registered Nurses encounter when advocating for patients in the healthcare setting?

2.1. Design

The study used a qualitative approach to arrive at the study result. The method was chosen to enhance collection of data based on participants' personal experiences with regard to barriers they faced when advocating for patients in the healthcare facility (Creswell, 2014 ; Neuman, 2011 ).

2.2. Setting and participants

The research occurred in a metropolitan hospital in Ghana. All nurses employed in the various wards in the hospital formed the population for this study. These wards and units were chosen to enable the researchers to obtain required information for achievement of the set objectives (Creswell, 2014 ). Sampling procedure was purposive because only nurses who were interested and had the ability to provide the needed information were interviewed (Burns & Grove, 2011 ; Creswell, 2014 ). A total of 25 Registered Nurses participated in the study on achievement of saturation. Detailed information on the study setting and participants can be obtained from Nsiah et al. ( 2019 ).

2.3. Data collection

Data collection began in February 2016 and ended in May 2016 by using a semi‐structured interview and an interview guide (Creswell, 2014 ). The audio‐taped interviews which lasted between 35 to 45 min excluded the participants' demographic information and made use of pseudonyms for confidentiality purpose. Twenty interviews took place in a designated room in the health facility, with the remaining five occurring in the offices of the participants involved. These participants were asked to tell the barriers they faced when advocating for patients and instances where they could not advocate as a result of some barriers (Nsiah, 2016 ).

2.4. Ethical considerations

This study was permitted by a University's ethics committee and that of the hospital. An informed consent was also signed by each participant on voluntary basis. In addition, proper data management, as well as pseudonyms, was used to ensure confidentiality and anonymity of respondents.

2.5. Data analysis

The study data were analysed inductively, using a qualitative content analysis (Creswell, 2014 ; Miles & Huberman, 1994 ). The data analysis occurred alongside with collection of data until saturation was achieved. Themes were directly attained from the content of the participants' responses and not from the personal views of the authors. For detailed data analysis, refer to Nsiah et al. ( 2019 ).

2.6. Rigour

Rigour in qualitative study deals with trustworthiness or measures put in place to ensure the quality of a research (Creswell, 2014 ). The authors employed necessary measures to assure credibility through the purposeful selection of study participants, member check and peer review (Creswell, 2014 ; Polit & Beck, 2014 ). Confirmability and transferability were also assured. The identified themes significantly agree with nursing literature. Finally, excerpts from participants' responses were directly quoted to ensure authenticity. Detailed description of rigour can be found in Nsiah et al. ( 2019 ).

3.1. Study participants

Twenty‐five nurses took part in the study without any coercion. These nurses had practiced in the clinical setting for about 5–21 years and above. Refer to Nsiah et al. ( 2019 ) for details on participants.

3.2. Main theme: lack of cooperation between healthcare team, care recipients and the health institution

This study aimed at exploring barriers confronting Registered Nurses who advocate for patients in the healthcare setting. Themes that identified have been provided in Table Table1 1 .

Analysis of study result

Lack of cooperation between healthcare team, care recipients and the health institution.

3.3. The health institution and work environment

Sub‐themes under this section ranged from working environment, limited medical equipment, colleague nurses and physicians. Direct quotes from participants as cited in Nsiah ( 2016 ) are presented below:

…We face a lot of challenges when sometimes you try to help or speak for a patient. You speaking for the patient may bring awkward relationship between you and the other staff. When you come to the facility itself, I will say they don't give you the chance to advocate for the patients in terms of the rules and regulations given by the facility… (Mrs. OP1, 1‐5 yr of experience) …It is the doctors that don't support us at times. Sometimes patients will come and you call the doctor, he refuse to come and say, continue to monitor, but you know something bad will happen if they don't come and do something…This hospital lacks many things. Even a bag for patients to donate blood there is none available… (Mrs. T2, 11‐15 yr of experience) …At times to some of the doctors are not cooperative at all because they think that they are ahead of us, so at times when you suggest to them, some take it, but others will not take it and refuse your offer… (Mrs. M2, 6‐10 yr of experience)

3.4. The patients

Individual patients were noted by the respondents as hindrances to the advocacy process due to limited understanding of their conditions, superstitions and ideologies as indicated below:

We have a lot of illiteracy among our patients, so sometimes they don't understand what is going on. So when you try to tell them their attitude pushes you away… (Mrs. OP1, 1‐5 yr of experience) …I think some of the patients have certain perceptions and ideologies before they come to the hospital. So it doesn't matter how you educate them when they come they still stick to what they know from the house, they are not ready to change… (Mrs. O2, 1‐5 yr of experience)

3.5. Legal support

The nurses disclosed that in some instances, they could not advocate for patients because of the absence of legal backing in the case of lawsuit. Some of respondents cited the following example:

Hmm, because of patients' rights, you can't force the patient…So if a patient says this is what I want you can't say I would not do it for you. At times this is what the patient wants but you know that this is not good for the patient…. Sometimes you would want to do it by force but because of the legal backing, you can't defend yourself… (Mrs. O4, 1‐5 yr of experience)

3.6. Anticipated negative outcome of advocacy

According to participants, their failure in previous attempt to advocate for patients hindered them from advocating further because they believed the outcome would surely be negative. Participants gave the following examples:

…There are several cases where you attempt to advocate, but whatever you write, your superior comes and cancels it. So the next day, you wouldn't want to do anything again because nothing good will come out of it… (Mr. P3, 6‐10 yr of experience)

Fear of loss of job was another anticipated negative outcome revealed by the nurses. Participants disclosed how hospital authorities threatened to transfer them if they kept speaking on behalf of patients as noted below:

…Because I do it once and am told if I don't take care I am going to be transferred, then I will not do it again. In fact when I come to work and do my duties, if I leave the work that is all, nothing about work again. Because if am transferred to a place where my family is not there, I will not go… (Mrs. C1, 1‐5 yr of experience)

3.7. Ineffective communication and interpersonal relationship

Ineffective communication and interpersonal relationship constituted barriers to advocating for patient as revealed in the excerpt below:

…They already have their preconceptions before coming to the hospital. So they don't see the nurse as a friend to establish that relationship with you for you to be able to get to know their need to be able to help them. (Mrs. C2, 6‐10 yr of experience) …Another challenge is about communication skills. There are people who really don't know how to communicate. You might be saying a good thing, but you can get the other person angered by the way you bring out your point… (Mrs. T1, 6‐10 yr of experience)

3.8. Patient's family members

The result pointed out patients' family members as a hindrance to nurses' ability to advocate for patients as quoted below:

…Sometimes families are not supportive…There have been cases whereby families just come and dump patient in the hospital and vanish. The nurse has to do everything like the parents. You expect the family, father and mother to even pick calls when you call, but they will not… (Mr. P3, 6‐10 yr of experience) …Another challenge is Lack of education on health issues, especially concerning women. Also, superstitions, because they have a lot of ideas before they come so if you want to change everything at once you normally face a challenge… (Mrs. O7, 1‐5 yr of experience)

3.9. Lack of support for nurses

Insufficient backing from nursing authorities coupled with absent policies on the kind of assistance for nurses who faulted during the advocacy process emerged as barrier confronting nurses who advocate for patients (Nsiah, 2016 ).

If you are advocating definitely you will need the help of a physician, a nutritionist, or maybe a physiotherapist, the lab people might have to come in. and if they are not ready …It will kind of make your job more difficult. Because when you get to one level and the other person refuses to take it up, there is a gap and advocacy becomes difficult. (Mrs. C 1, 1‐5 yr of experience) Sometimes a patient come at midnight and there is no doctor …Even though you know what to do but because of the legalities you just can't help. If I try to prescribe and something goes wrong and they call I will not get support… (Mrs. OP1, 1‐5 yr of experience) …should the advocacy fail the fear of being in trouble make you think twice… (Mrs. O6, 1‐5 yr of experience)

3.10. The nurses

According to the result, some nurses do not believe in advocacy as part of nursing, while others are not committed nor assertive enough. Hence, they did not advocate for the patients as expected as disclosed below:

…sometimes we as nurses are not assertive enough… (Mrs. M4, 1‐5 yr of experience) Sometimes the staff ourselves are bit a reluctant to help the patients but myself when I see certain things I can't stay… (Mrs. O2, 1‐5 yr of experience) …some nurses don't care about whatever happens to the patient… (Mrs. C1, 1‐5 yr of experience)

3.11. The advocacy process

The processes nurses went through to accomplish the advocacy action were noted as being too difficult. Hence, most nurses could not intervene for hospitalized patients.

Oh, the challenges are many, you have to know, move from here, go there, do this, the bureaucracies, the channels you need to pass through are many and it is just difficult pushing it … (Mr. P1, 1‐5 yr of experience) …when I first tried to advocate for a patient…, I got fed up and I said why don't I stop? … (Mrs. T2, 11‐15 yr of experience)

3.12. Religious and cultural beliefs

It is evident from participants' responses that patients and family's religion and culture hindered the advocacy process. As indicated in Nsiah ( 2016 ), some patients opted going to pray in camps than to be referred for proper care in another health facility, whereas some refused referral without husband's consent:

…The husband is also saying that the conditions that we want to refer he is not ready to take the woman to the place. Rather he wants to take the woman to a prayer camp… The BP was very high. We gave her a drug and needed her to sleep but she told me she will not sleep and that she is praying with a pastor….We admitted her but she went to the house because the man was not available to accept her admission per the tradition… (Mrs. O5, 1‐5yr of experience)

3.13. Financial difficulties

The research showed that most patients could not afford the money required to accomplish the needed advocacy. Excerpts from participants' responses have been provided below :

…I also think poverty is a barrier. Because let's say if there is referral, at the end of the day you advocate for the patient but there is no money for the patient to go. (Mrs. O7, 1‐5 yr of experience) …At times too we don't have the drugs in the hospital and the patient does not have the money to buy. We have a case here, we want to refer the case. We gave her the drugs we have here in the emergency kit. She is supposed to replace it and she doesn't have the money… (Mrs. O6, 21 yr of experience)

3.14. Inadequate knowledge

This theme is about the nurses' own limited knowledge of patients' conditions and how to approach the advocacy process. Also, some patients rejected the advocacy process initiated by nurses as a result of poor knowledge. Below are direct quotes from participants:

When I first tried to advocate for a patient, I got fed up due to limited education…Some patients do not agree with you, other nurses also lack understanding. Then I realized that this is someone's life we are talking about. So whether the person at the superior end likes it or not, you have to find a way around it. So I think is about lack of knowledge… (Mrs. T1, 6‐10 yr of experience) …Knowledge and education is a hindrance. …So knowledge is very important. It has really helped some of us in advocating for the patients… (Mrs. M2, 6‐10 yr of experience)

4. DISCUSSION

This study explored barriers to practicing patient advocacy in healthcare setting. The main theme was noted as a lack of cooperation between the healthcare team, care recipients and the health institution itself. The overall theme was identified from 10 themes which included the health institution and work environment, ineffective communication and interpersonal relationship, patients' family, religious and cultural beliefs. This result agrees with several study findings in nursing literature. For instance, Negarandeh et al. ( 2006 ) revealed poor motivation coupled with powerlessness as a barrier to advocating for patients in the Iranian context, while complexity of the advocacy process was what Negarandeh, Oskouie, Ahmadi, and Nikravesh ( 2008 ) found as a great obstacle to patient advocacy.

Also, Kohnke ( 1982 ) similarly pointed the healthcare institution and the environment where nursing occurs as a key obstacle during nursing advocacy. Furthermore, a report by Black ( 2011 ) showed that fear of labelling and retaliation in the workplace restricted nurses from advocating for their patients. Contrary to fear of losing one's job as noted in this study, Abbaszadeh et al. ( 2013 ) found limited educational programmes for nurses as the main problem that prevented nurses from advocating in an Iranian hospital. Meanwhile, the finding is consistent with Negarandeh et al. ( 2006 ) in a different hospital in Iran. Hence, it can be concluded from this study finding that success in patient advocacy differs based on prevailing conditions in the individual healthcare settings.

Moreover, as cited in Nsiah ( 2016 ), lack of legal support as a theme in this study seems to provide evident to support the work of Vaartio et al. ( 2006 ) and Bu and Jezewski ( 2007 ) who noted that nurses allowed patients' preferences to prevail even though they knew it was wrong due to fear of being left alone without support in the event of lawsuit. Another barrier found was ineffective communication and interpersonal relationship. Yet, researchers have revealed that effective patient advocacy required good interpersonal and therapeutic communication skills MacDonald ( 2007 ) and Peplau ( 1992 ). It is therefore evident from the study that a gap exists in nursing theory and practice. Hospital authorities should enhance availability of adequate information and cordial relationship between nurses, members of healthcare team and care recipients to promote quality advocacy, job satisfaction and patient safety.

Hanks ( 2010 ) showed that nurses' own personalities could either promote or hinder them from advocating for their patients which is exactly what was found in this study suggesting that advocacy is subjective. Hence, regardless of patients' conditions and peculiar needs, advocating for patients will depend basically on the individual nurse attending to the patient. Nursing leaders should therefore discharge their supervisory role efficiently in health facilities to promote safety and speedy recovery.

Finally, respondents pointed patients' family, financial difficulty and inadequate knowledge, culture and religion as limitations to advocating for patients. According to the participants, as pointed out in Nsiah ( 2016 ) several attempts made to advocate for a change in patients' drug and transfer for better care failed as a result of monetary constraints. Thacker arrived as similar findings ( 2008 ) and Davis and Konishi ( 2007 ) in Japan. It therefore behoves on the government to put measures in place to assist care recipients while on admission. Interpersonal dialogue between patients, their families and religious leaders is very vital to effective advocacy to promote safety and quality care.

5. LIMITATIONS

The scope of this study was restricted to a single hospital. Also, participants could have been extended to include physicians and patients as well for broader perspectives of existing hindrances to the patient advocacy activities in the healthcare setting.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The goal of this study was to explore barriers confronting Registered Nurses who advocate for patients in the healthcare setting. Lack of cooperation between the healthcare team, care recipients and the health institution was the overall theme that identified from analysis of the data. Themes identified included but not limited to patients, the health institution, inadequate knowledge, ineffective communication and interpersonal relationship, financial constraints, and religious and cultural beliefs. It was found in the study that negative consequences including health complication and death resulted from unsuccessful advocacy initiated by the nurse in the healthcare setting. Notwithstanding, therapeutic communication and good interpersonal relationship were noted as facilitators in the advocacy process during clinical practice. This study concluded that patients and families' cultural believes, available finance, determined whether or not their attending nurse could advocate for them. The result suggests that physicians had higher autonomy in relation to patient care in the hospital. Therefore, success in advocating for patients requires cooperation between physicians, nurses and the entire healthcare team. This study significantly created the awareness and understanding of the challenges faced by Registered Nurses when advocating for their patients, its corresponding consequences and the need to promote successful patient advocacy for an improved quality and safety in caring for patients. More importantly, it has also contributed to the overall body of nursing knowledge which could be beneficial to other countries with similar context.

7. IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH, EDUCATION AND PRACTICE

The existing physicians' autonomy in the Ghanaian healthcare facility necessitates research into physician's viewpoints on nurses having to advocate for patients in hospitals. Secondly, the Ministry of Health should ensure inclusion of therapeutic communications and interpersonal skills in the curriculum of all nursing educational programmes. It also behoves on hospital managers to support Registered Nurses to participate in continuous education programmes that will boost their competency in advocating for hospitalized patients. Finally, this study showed that advocating for patients is a teamwork. Hence, it requires involvement of the entire healthcare team, patients, family member and their religious leaders to promote its success in the care setting.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interest to be declared in this study by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria [recommended by the ICMJE ( http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/ )]:

- Significant contributions to conception and design, data collection, or analysis and interpretation of data.

- Drafting the manuscripts or critical revision of the content.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our sincere gratitude goes to the study participants for their time and voluntary contribution to the success of the study. We also thank professor Janet Gross, Ms Dzigbodi Kpikpitse, Dr. Joseph Agyenim Boateng and Dr. Francis Nsiah for their valuable suggestions and support.

Nsiah C, Siakwa M, Ninnoni JPK. Barriers to practicing patient advocacy in healthcare setting . Nursing Open . 2020; 7 :650–659. 10.1002/nop2.436 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

No specific funding from the public, commercial or non‐profit organizations was received by the authors in support of this study.

- Abbaszadeh, A. , Borhani, F. , & Motamed‐Jahromi, M. (2013). Nurses' attitudes towards nursing advocacy in the southeast part of Iran . Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences , 3 ( 9 ), 88–93. [ Google Scholar ]

- Abekah‐Nkrumah, G. , Manu, A. , & Ayimbillah Atinga, R. (2010). Assessing the implementation of Ghana's Patient Charter . Health Education , 110 ( 3 ), 169–185. 10.1108/09654281011038840 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Attree, M. (2007). Factors influencing nurses' decisions to raise concerns about care quality . Journal of Nursing Management , 15 ( 4 ), 392–402. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00679.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Black, L. M. (2011). Tragedy into policy: A quantitative study of nurses' attitudes towards patient advocacy activities . American Journal of Nursing , 111 ( 6 ), 26–35. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bu, X. , & Jezewski, M. A. (2007). Developing a mid‐range theory of patient advocacy through concept analysis . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 57 ( 1 ), 101–110. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04096.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burns, N. , & Grove, S. K. (2011). Understanding Nursing Research: Building Evidence Based Practiced (6th ed), Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications Ltd. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis, A. J. , & Konishi, E. (2007). Whistleblowing in Japan . Nursing Ethics , 14 ( 2 ), 194–202. 10.1177/0969733007073703 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghana News Agency (GNA) (2015). Cape Coast Metropolitan Hospital in a bad condition . Retrieved from https://www.newsghana.com.gh/cape-coast-metro-hospital-bad-condition/#respond . [ Google Scholar ]

- Hanks, R. G. (2010). The medical‐surgical nurse perspective of advocate role . Nursing Forum , 45 ( 2 ), 97–107. 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2010.00170.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohnke, M. F. (1982). Advocacy, risk and reality . St. Louis, MO: The C. V. Mosby Co. [ Google Scholar ]

- MacDonald, H. (2007). Relational ethics and advocacy in nursing: Literature review . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 57 ( 2 ), 119–126. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04063.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miles, M. B. , & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded source book (2nd ed.). Newberg Park, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Negarandeh, R. , Oskouie, F. , Ahmadi, F. , & Nikravesh, M. (2008). The meaning of patient advocacy for Iranian nurses . Nursing Ethics , 15 ( 4 ), 457–467. 10.1177/0969733008090517 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Negarandeh, R. , Oskouie, F. , Ahmadi, F. , Nikravesh, M. , & Hallberg, I. R. (2006). Patient advocacy: Barriers and facilitators . BMC Nursing . 10.1186/1472-6955-5-3 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Neuman, W. L. (2011). Social Research methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (7th ed). Boston: Pearson (Allyn & Bacon). [ Google Scholar ]

- Norman, I. D. , Aikins, M. , Binka, F. N. , & Nyarko, K. M. (2012). Hospital all‐risk emergency preparedness in Ghana . Ghana Medical Journal , 46 ( 1 ), 34–42. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nsiah, C. (2016). Experiences of registered nurses in carrying out their role as patients' advocates . Retrieved from https://erl.ucc.edu.gh/ [ Google Scholar ]

- Nsiah, C. , Siakwa, M. , & Ninnoni, J. P. K. (2019). Registered nurses' description of patient advocacy in the clinical setting . Nursing Open , 6 , 1124–1132. 10.1002/nop2.307 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peplau, H. E. (1992). The art and science of nursing: Similarities, differences and relations . Nursing Science Quarterly , 1 , 8–15. 10.1177/089431848800100105 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Polit, F. D. , & Beck, T. (2014). Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters, Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thacker, K. S. (2008). Nurses' advocacy behaviors in end‐of‐life nursing care . Nursing Ethics , 15 ( 2 ), 174–185. 10.1177/0969733007086015 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaartio, H. , Leino‐Kilpi, H. , Salanterä, S. , & Suominen, T. (2006). Nursing advocacy: How is it defined by patients and nurses, what does it involve and how is it experienced? Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences , 1 ( 20 ), 282–292. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00406.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 20 March 2021

Putting patients first: development of a patient advocate and general practitioner-informed model of patient-centred care

- Bryce Brickley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7093-7793 1 ,

- Lauren T. Williams 1 ,

- Mark Morgan 2 ,

- Alyson Ross 3 ,

- Kellie Trigger 3 &

- Lauren Ball 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 21 , Article number: 261 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

10 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Patients, providers and health care organisations benefit from an increased understanding and implementation of patient-centred care (PCC) by general practitioners (GPs). This study aimed to evaluate and advance a theoretical model of PCC developed in consultation with practising GPs and patient advocates.

Qualitative description in a social constructivist/interpretivist paradigm. Participants were purposively sampled from six primary care organisations in south east Queensland/northern New South Wales, Australia. Participants engaged in focus group discussions where they expressed their perceptions, views and feelings of an existing PCC model. Data was analysed thematically using a constant-comparison approach.

Three focus groups with 15 patient advocates and three focus groups with 12 GPs were conducted before thematic saturation was obtained. Three themes emerged: i) the model represents the ideal, ii) considering the system and collaborating in care and iii) optimising the general practice environment. The themes related to participants’ impression of the model and new components of PCC perceived to be experienced in the ‘real world’. The data was synthesised to produce an advanced model of PCC named, “ Putting Patients First: A Map for PCC ”.

Conclusions

Our revised PCC model represents an enhanced understanding of PCC in the ‘real world’ and can be used to inform patients, providers and health organisations striving for PCC. Qualitative testing advanced and supported the credibility of the model and expanded its application beyond the doctor-patient encounter. Future work could incorporate our map for PCC in tool/tool kits designed to support GPs and general practice with PCC.

Peer Review reports

Patient-centred care (PCC) is care that is respectful and responsive to the wishes of patients [ 1 ]. In 2001, the U.S. based National Academy of Medicine (formerly, Institute of Medicine) nominated PCC a key objective for improving health care in the twenty-first century [ 2 ]. High levels of PCC have been associated with improved health outcomes [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ], enhanced relationships between providers and patients [ 5 ], enhanced patient satisfaction [ 3 , 7 ] and greater adherence to treatment [ 4 ]. Clearly, PCC is valuable to patients, providers and health care organizations.

Family physicians, also called general practitioners (GPs), are well-positioned to provide PCC because they are usually the first contact for patients entering health systems [ 8 , 9 ]. Practising GPs need to be up-to-date consumers of research including PCC, to deliver high-quality and low-risk care [ 9 ]. Research on PCC has previously been synthesised through reviews and concept analyses, resulting in conceptual models that can be utilised by health care providers [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Existing models of PCC vary in their relevance to a specific health setting or provider [ 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

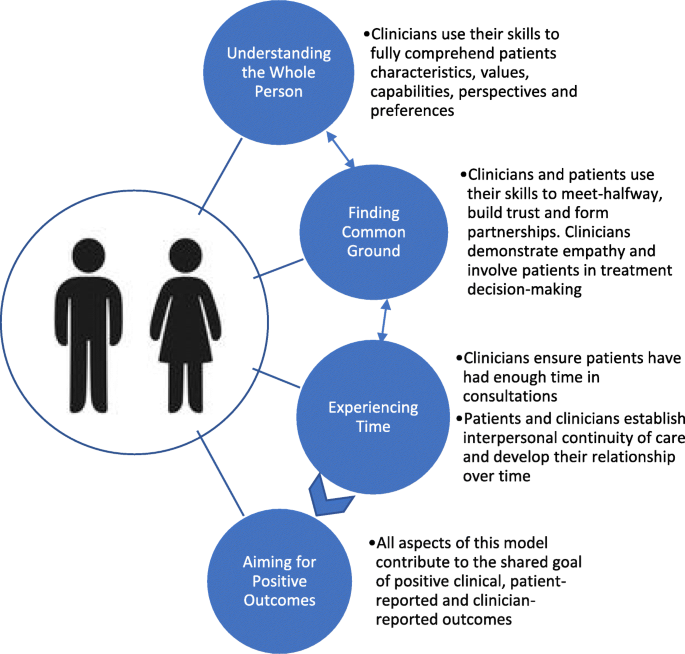

Models of PCC are essential to supporting the understanding of PCC and the extent to which it is achieved in practice. One of the most commonly applied PCC models was published in 2014 by Scholl and colleagues, who reviewed 417 articles situated in primary, tertiary and acute care. This PCC model consists of 15 distinct dimensions, but its applicability to GPs and general practices is limited due to limited included studies being situated in primary care (< 5%) [ 10 ]. The most recently published model of PCC for GPs was published in 2019 by Brickley and colleagues [ 14 ]. This model is highly theoretical because it arose from an integrative review of predominantly quantitative articles but also, systematic review, mixed methods and only three qualitative articles [ 14 ]. Furthermore, included studies needed to refer to both a GP and patient and consequently, most studies took place in the micro-level of health care (doctor-patient encounter) [ 14 ]. The Brickley and colleagues’ model [ 14 ] places greater emphasis on the micro-level of health care compared to the practice-level. The model is yet to be evaluated and its ability to inform the development of an implementation tool kit is unknown.

In the ‘real world’, PCC is derived from the context to which it is implemented, social experience and individual perspectives [ 16 ]. These factors can only be captured by qualitative study design [ 14 , 17 , 18 ]. Patient advocates offer unique perspectives because they are typically trained and experienced in research, and they consider the significance for patients throughout the research process [ 19 ]. Furthermore, they tend to offer an ‘expert’ perspective on PCC because of their likely deeper understanding of the health system compared with typical patients. Consultation with patient advocates and GPs can inform new ideas for supporting PCC.

This study aimed to evaluate the recent model of PCC for GPs developed by Brickley and colleagues [ 14 ], in collaboration with GPs and patient advocates, to advance a model of PCC. A PCC model-informed implementation tool kit has the potential to be valuable to policy makers, patients, health professionals, health systems and researchers to inform PCC research.

Study design

This study was conducted from a social constructivist/interpretive philosophical position [ 20 ]. The research question was “How do patients and GPs perceive the model of PCC for GPs, published by Brickley and colleagues in 2019 [ 14 ]?” This model is comprised of four inter-related components and is displayed in Fig. 1 . To address the research question, this study employed a qualitative descriptive approach, utilising focus groups with patient advocates and focus groups with GPs. Focus groups commenced with a broad exploration of GP-delivered PCC, which has been published elsewhere [ 21 ]. Ethics approval was obtained from the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (No. 2019/634).

Model of Patient-Centred Care for General Practitioners [ 14 ]

Selection and recruitment of study population

Patient advocate and GP participants were recruited from six primary care organisations in south east Queensland and northern New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Three patient advocacy group managers and three general practice managers who were known to researchers were purposely engaged via email to assist in the recruitment of participants. Study information sheets were provided to managers and recruitment snowballed through their respective organisations. Patient advocates are those who participate in health consumer engagement, advisory or consultant groups and ‘advocate’ on the behalf of others [ 22 ]. The involvement of patient advocates in research has been shown to produce health information that meets the needs of consumers, assist with bridging the gap between research and practice [ 23 ], and increase the quality of services [ 24 ]. Eligible patient advocates were English speaking adults, who had participated in at least one recent GP consultation (< 3 months) and were currently participating in patient engagement activities. We considered engagement activities to be any formal role where an individual is advocating in health care on behalf of other patients. Eligible GP participants were English speaking adults who were currently practising.

Interview protocol

Focus groups contained structured questions outlined in an interview guide developed by the research team (Table 1 ). The interview guide was informed by Kvale’s (1996) stages of conducting in-depth interviews [ 25 ], then tailored for use in a focus group. The interview guide was piloted with four purposely sampled patients, and then modified prior to data collection. The facilitator (BB) initially provided participants with a hard copy of Brickley and colleagues’ PCC model [ 14 ]. Participants were given time to read the model, provided with an opportunity to ask questions and clarify their understanding, and were encouraged to reflect on their ‘real world’ experiences of PCC in consideration of the model. The facilitator then posed questions to the group in accordance with the structured guide. To advance conceptual thinking, probing questions were added to encourage participants to elaborate on initial ideas. All focus groups were ~ 30 min in duration. After the first focus group and initial analysis, a theoretical sampling technique was used to revise and adapt the interview process as the research progressed [ 26 ]. Interviews were redirected to focus on new concepts as some components of PCC became saturated with explanatory data. This was an iterative process and researchers explored emerging codes and themes in subsequent focus groups.

Data collection

Participants’ postcodes of residence were recorded. All other data collection and analysis were completed simultaneously and the sample size were determined when thematic saturation was reached [ 27 ]. An iterative approach of purposive sampling was undertaken to ensure data saturation [ 27 ]. Focus groups were audio-recorded using a dictaphone and subsequently transcribed for analysis. One of the three patient advocate focus groups was moderated by a researcher (KT) who is a patient advocacy group manager. One of the three GP focus groups was moderated by a researcher (MM) who is a GP. The primary researcher (BB), who is a PhD Candidate, served as both facilitator and moderator in the remaining four focus groups. Moderators used their background and skills to maintain a controlled, open dialogue in the focus group; to add scrutiny to concepts that arose and to make detailed notes, which assisted with analysis. Participants were invited to verify the accuracy of the transcript with their contribution to the focus group.

Data analysis

Participants’ geographic information was interpreted using scores from the accessibility/remoteness index of Australia (ARIA) [ 28 ]. Qualitative data was analysed using a constant comparison method and the six phases of thematic analysis [ 29 ]. Data analysis commenced simultaneously with data collection, where researchers generated initial ideas of themes to explore in subsequent interviews. Field notes supported the analytical process. No further focus groups were required when thematic saturation was obtained; which was identified by research team consensus as analysis failed to yield any new codes or themes [ 27 ]. The analytical process was highly reflective, and the entire research team took part in reviewing, defining and naming themes [ 17 ].

Model development

The primary researcher (BB) reflected on the present study’s interview data and its relationship to Brickley and colleagues’ existing PCC model [ 14 ]. The entire research team then revised the conceptual model, to be inclusive of as much data as possible. New elements of PCC were synthesised with the existing model to form an advanced, integrated summation of PCC for GPs and general practices. The components and design of the advanced model were continually discussed by the research team until a consensus was reached. The primary researcher (BB) collaborated with a local graphic design company to produce a visually appealing map for PCC that was purposely designed for use by patients, GPs and general practices.

Model verification

Once the model was developed, one practice manager and one advocacy group manager were approached to refer participants for an additional verification step. The newly developed model of PCC was presented to a group of patient advocates during a local consumer advisory council meeting, some, but not all the 15 patient advocate attendees had participated in focus group one of this study. The model of PCC was also presented to three GPs, one of whom had participated in focus group four, whilst the other two were colleagues of the previous participant. Participants were invited to verify the accuracy of the advanced model with an emphasis on its applicability to the ‘real world’. This stage informed further development on the model to ensure it closely reflected participants ideas and was inclusive as much data as possible.

Participants

Twenty-seven participants were involved in focus groups between September 2019 and November 2019. Participants’ individual characteristics are displayed in Table 2 . There were 15 patient advocates (5 male, mean age (SD) 57 [ 19 ] years) and 12 GPs (6 male, mean age (SD) 53 [ 12 ] years). Nearly all participants (93%) resided in major cities with relatively unrestricted access to goods and services [ 28 ].

Thematic analysis

Three themes emerged from our analysis that related to participants’ overall impression on the model and gaps that were identified: i) model represents the ideal of PCC, ii) considering the system and collaborating in care and iii) optimising the general practice environment. We also noted general suggestions from participants to improve the model’s application to the ‘real world’ (Supplementary Table 1 ). These did not emerge as main themes as they were mentioned in brief but were important to the advancement of the PCC model. Interpretive findings are described below and supported with narrative quotes. Patient advocate data is indicated by PA1–15 and GP data by GP1–12.

Model represents the ideal of patient-centred care

Participants’ ideals of PCC aligned with the components displayed in the model. Providers’ said, “it’s all ideal” (GP2); “I agree with all of it, it’s got everything to it. It’s what I thought it [PCC] was” (GP9). Patient advocates said, “this is a perfect model” (PA3); “In a perfect world, every GP would follow this model” (PA1). However, there was uncertainty to whether it is possible to achieve all components of this model universally in practice. One patient advocate said they had never experienced PCC consistent with the model; “If you showed me a doctor that does this I would go to that doctor” (PA3). Some providers aimed to implement all aspects of the model but indicated that it is not always achievable, “I’m sure this is what most of us would be aiming for” (GP2). One GP suggested that the wording of the model was particularly idealistic, and that it should be changed to be more realistic, “clinicians try to ensure patients have had enough time in consultations” (GP3).

Considering the system and collaborating in care

The complexity of the local health system was reported by both GPs and patient advocates to be a common barrier to PCC. One GP felt a barrier to PCC to be “trying to understand the public system” (GP2). A patient advocate expressed “I’ve had to find [services] myself because doctors didn’t have that knowledge, and because it wasn’t easy to find” (PA7). One GP reflected on an experience regarding care coordination, which was made difficult due to a complex health system, “it could be a year’s wait before he gets reviewed … you’ve got to get him seen faster than that” (GP3).

Cost and remuneration were key considerations of GPs when striving for PCC. One GP felt that the current health system’s funding arrangements caused personal financial pressures for GPs, which led them to compromise PCC. Similarly, one other GP reported to act against the wishes of a patient if the cost to the health system is too high:

I may refuse to do an MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] if they [patients] insist on it, if I don’t think it’s appropriate, and I think cost is important, we are the gatekeepers (GP6).

Time poor general practice business models, such as “turnstile type medical practices” (GP3); and policy “Medicare is underfunded without doubt for general practice” (GP6) exacerbated time and financial pressure placed on GPs. One solution for patients and GPs to mitigate the complexity of the health system while striving for PCC was to collaborate with other health professionals, peers, and organisations. One GP stated,

It’s very important that we can connect [patients] to helpful resources and allied health professionals. We cannot do everything in one sitting, we are just one person (GP12).

Optimising the general practice environment

Patient advocates viewed the entire general practice environment as an important influence on the extent to which PCC is achieved; “person-centred care starts as you walk in the door!” (PA11). Patient advocates associated the environment with outcomes; “the environment will facilitate the opportunity to have a successful outcome” (PA14). In this context, general practice reception staff were regarded as having a role in PCC because they can “help someone feel at ease … communication, respect and safety start with reception” (PA12). Patient advocates noted that environmental design (e.g. purposeful equipment placement, colours and sounds), general practice culture and reception staff had the potential to promote PCC. One patient advocate (PA14) recounted the experience of a service ‘walk through’. The participant described how valuable his feedback was to the patient-centredness of the service:

… someone painted it, changed the seats, changed the whole format, gave them a little bit of [further] advice, and the next time I went it I was like wow! You could feel the [patient-centred] culture from the moment you got there (PA14).

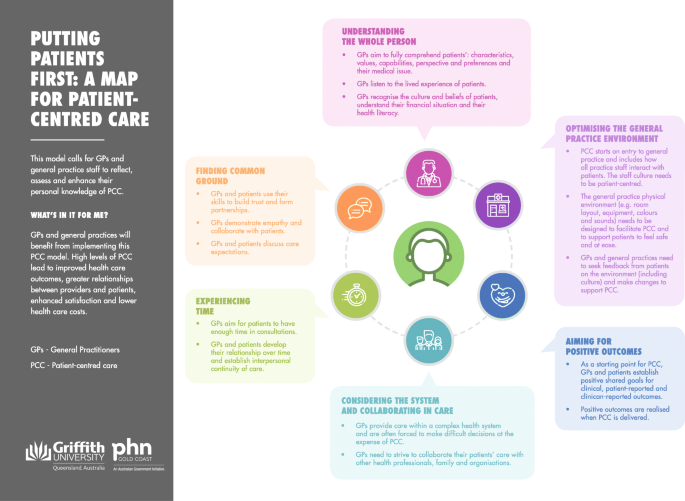

Conceptualisation and verification of putting patients first: a map for PCC

Putting patients first: A Map for PCC was conceptualised from the data and is displayed in Fig. 2 . The map illustrates the integration of new PCC components: considering the system and collaborating in care; and optimising the general practice environment. The verification groups called for the text in the map to make explicit the incentive to deliver PCC, and to be orientated to engage general practice managers, all general practice staff and patients. A purpose statement and ‘what’s in it for me’ statement were added and the six components of PCC were supported with text descriptors as a guide for key stakeholders of PCC in general practice.

Putting Patients First: A Map for Patient-Centred Care (developed by our research team)

Putting patients first: A Map for PCC was synthesised from the evaluation of an existing model of PCC for GPs [ 14 ] in consultation with GPs and patient advocates. This study supported the Map for PCCs readiness for practice, as qualitative testing has contextualised the model to the ‘real world’ and extended its application to beyond the micro-level of health care. Our model provides an enhanced conceptual understanding of PCC that can be used to support the development of tools/tool kits and future research promoting the adoption and implementation of PCC.

An evaluation of the U.K. based MAGIC programme found that a lack of support tools and the day-to-day demands and priorities for GPs inhibited shared decision-making, which is a fundamental component of PCC [ 30 ]. These findings are reflected in our study as both patient advocates and GPs identified that GPs need support for PCC. Providers in our study expressed that at times their practice’s business model placed greater pressure on their time with patients and personal remuneration, and consequently compromised their ability to practise PCC. Providers in the U. K system have experienced the same issue. A lack of time with patients, and reduced ability to deliver PCC has been reported to result in a loss of professional autonomy and diminished job satisfaction for GPs [ 31 ]. Responsibility to deliver PCC lies with providers but also the wider general practice team [ 9 ]. Continuing the education of PCC among all practice staff, with the use of the Map for PCC in a collaborative quality improvement activity has the potential to promote PCC and alleviate the pressure on individual GPs striving for PCC. The development of tools/tool kits that include our new Map for PCC, can prompt GPs with new ideas to deliver PCC and support GPs to re-hone their skills and knowledge regarding PCC.

A lack of time, financial pressure and the gatekeeper role were noted by GPs in our study as health system factors that contributed to compromising PCC. Participants’ proposed collaboration with other health professionals as a valuable strategy to alleviate GP time pressure and support PCC. This supports a recently published systematic review and qualitative investigation that reported collaborative care initiatives helped to alleviate individual GP workload, prevent GP burnout and support PCC [ 32 ]. Our findings add to the literature valuing the collaboration of care with other health professionals and a patient’s social support network as supportive of PCC.

Patient advocates in our focus groups highlighted the opportunity for environmental design, general practice culture and reception staff to facilitate PCC. In wider research, effective health care space design has been reported to reduce stress, anxiety, and increase patient satisfaction [ 33 ]. In hospitals, environmental characteristics (e.g. cleanliness of the space) have been reported to positively influence patient perceptions of patient-centeredness [ 34 ]. Of note, providers in our study did not raise consideration of the patient-centredness of their practice environment as an issue. This concept was emphasised in the map for PCC as a practical consideration for GPs to implement PCC and ensure patients feel safe and at ease when they engage with general practice. A patient-centred environment was outlined as supportive of all other aspects of the model, such as forming relationships with providers and involvement in care. Future research should explore novel interventions to assess and optimise the general practice environment to be conducive to and support PCC in practice.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that it was based on consultation with the users and beneficiaries of PCC. However, nearly all participants were based in an Australian, urban general practice setting. The applicability of the new Map for PCC outside this context is unknown. Qualitative description presented data in a language used by participants, which supported the new Map for PCC to be credibly contextualised to the ‘real world’ [ 35 ]. This study made explicit that change in practice is required to support the effective, universal delivery of PCC in accordance to our advanced model. This is important because innovation theory indicates that providers are more likely to implement practice change if there is evidence that change is required [ 36 ].

The synthesis of patient advocate voices with GP voices was essential to informing a model that captures the ‘real world’ understanding of PCC. Patient advocate voices are informed by their training, prior experiences with their GP and own health care, and their knowledge of the health care system. While we did not collect detailed information on the characteristics of patient advocates, their views are likely to be unrepresentative of their patient peers and this may introduce bias to our model. However, patient advocates have demonstrated that their understanding of PCC is highly individual and is grounded in their personal experience [ 21 ]. Patient advocates were essential to the development of our PCC model because of their likely deeper understanding of the health system and informed perspectives of health care compared with typical patients.

This study has advanced our conceptual understanding of PCC in the ‘real world’. Putting Patients First: A Map for PCC is a valuable tool for patients, providers and health systems that needs to be embedded into tools or support kits for PCC . A novel finding of this study is the importance of the general practice environment, and all staff within the environment for PCC delivery. The physical environment and the role of all general practice staff needs to be a focal point in any analyses or initiatives in the pursuit of PCC.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Accessibility/remoteness index of Australia

- Patient-centred care

General practitioner

Patient advocate

World Health Organization. People-centred and integrated health services: an overview of the evidence: interim report: World Health Organization; 2015.

Wolfe A. Institute of medicine report: crossing the quality chasm: a new health care system for the 21st century. Policy Polit Nurs Practice. 2001;2(3):233–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/152715440100200312 .

Article Google Scholar

Altin SV, Stock S. The impact of health literacy, patient-centered communication and shared decision-making on patients' satisfaction with care received in German primary care practices. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:450.

Saha S, Beach MC. The impact of patient-centered communication on patients’ decision making and evaluations of physicians: a randomized study using video vignettes. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(3):386–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.04.023 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kinmonth AL, Woodcock A, Griffin S, Spiegal N, Campbell MJ. Randomised controlled trial of patient centred care of diabetes in general practice: impact on current wellbeing and future disease risk. BMJ. 1998;317(7167):1202–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1202 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Egan M, Kessler D, Laporte L, Metcalfe V, Carter M. A pilot randomized controlled trial of community-based occupational therapy in late stroke rehabilitation. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2007;14(5):37–45. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1405-37 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bauman AE, Fardy HJ, Harris PG. Getting it right: why bother with patient-centred care? Med J Aust. 2003;179(5):253–6. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05532.x .

Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home 2013 [Available from: http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMHJoint.pdf .

Google Scholar

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Vision for general practice and a sustainable healthcare system: White paper, February 2019. East Melbourne, Victoria; 2019.

Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, Dirmaier J. An integrative model of patient-centeredness–a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107828. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107828 .

Lawrence M, Kinn S. Defining and measuring patient-centred care: an example from a mixed-methods systematic review of the stroke literature. Health Expect. 2012;15(3):295–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00683.x .

Sharma T, Bamford M, Dodman D. Person-centred care: an overview of reviews. Contemp Nurse. 2015;51(2–3):107–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2016.1150192 .

Sladdin I, Ball L, Bull C, Chaboyer W. Patient-centred care to improve dietetic practice: an integrative review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30(4):453–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12444 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Brickley B, Sladdin I, Williams LT, Morgan M, Ross A, Trigger K, Ball L. A new model of patient-centred care for general practitioners: results of an integrative review. Fam Pract. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmz063 .

Santana MJ, Manalili K, Jolley RJ, Zelinsky S, Quan H, Lu M. How to practice person-centred care: a conceptual framework. Health Expect. 2017;21(2):429–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12640 .

McCormack B, Dewing J, McCance T. Developing person-centred care: addressing contextual challenges through practice development; 2011.

Liamputtong P. Qualitative research methods. 4th ed. Victoria: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. The patient should be the judge of patient centred care. 2001;322(7284):444–5.

Ciccarella A, Staley AC, Franco AT. Transforming research: engaging patient advocates at all stages of cancer research. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(9):167. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2018.04.46 .

Creswell JW. A concise introduction to mixed methods research: sage publications; 2014.

Brickley B, Williams LT, Morgan M, Ross A, Trigger K, Ball L. Patient-centred care delivered by general practitioners: a qualitative investigation of the experiences and perceptions of patients and providers. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020:bmjqs-2020-011236. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011236 .

Health Consumers Queensland. Consumer and Community Engagement Framework For Health Organisations and Consumers. Brisbane; 2017.

Collyar D. How have patient advocates in the United States benefited cancer research? Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(1):73–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1530 .

Sarrami-Foroushani P, Travaglia J, Debono D, Braithwaite J. Key concepts in consumer and community engagement: a scoping meta-review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):250. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-250 .

Kvale S. Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1996.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Theoretical sampling. Sociological methods: Routledge; 2017. p. 105–114, Theoretical Sampling, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315129945-10 .

Tufford L, Newman P. Bracketing in qualitative research. Qual Soc Work. 2012;11(1):80–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325010368316 .

Queensland Treasury. Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia Brisbane, Queensland 2019 [Available from: https://www.qgso.qld.gov.au/about-statistics/statistical-standards-classifications/accessibility-remoteness-index-australia .

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa .

Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Edwards A, Stobbart L, Tomson D, Macphail S, et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ. 2017;357:1744.

Doran N, Fox F, Rodham K, Taylor G, Harris M. Lost to the NHS: a mixed methods study of why GPs leave practice early in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(643):e128–e35. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X683425 .

Norful AA, de Jacq K, Carlino R, Poghosyan L. Nurse practitioner–physician comanagement: a theoretical model to alleviate primary care strain. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):250–6. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2230 .

Schweitzer M, Gilpin L, Frampton S. Healing Spaces: Elements of Environmental Design That Make an Impact on Health. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(supplement 1):S-71–83.

Sofaer S, Firminger K. Patient perceptions of the quality of health services. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26(1):513–59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153958 .

Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G .

Hader JM, White R, Lewis S, Foreman JL, McDonald PW, Thompson LG. Doctors’ views of clinical practice guidelines: a qualitative exploration using innovation theory. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(4):601–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00856.x .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patient advocates and practising GPs who participated in this study. We also thank those who assisted with the coordination and organisation of the focus groups.

BB is supported by a PhD Scholarship co-funded by Menzies Health Institute Queensland, Griffith University and Gold Coast Primary Health Network, Australia. LB’s salary was supported by a National Health and Medical Council Research Fellowship. Menzies Health Institute Queensland, Griffith University, funds were used to provide food and beverages for participants during data collection. All funding bodies did not directly support any the design of the study, data analysis, interpretation or the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Menzies Health Institute Queensland, Griffith University, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia

Bryce Brickley, Lauren T. Williams & Lauren Ball

Bond University, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia

Mark Morgan

Gold Coast Primary Health Network, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia

Alyson Ross & Kellie Trigger

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BB, LB and LW conceived and designed the study. BB performed the data collection in collaboration with MM and KT. BB, LB, LW and AR conducted data analysis and interpretation. All authors made substantial contributions to the writing of the manuscript and have approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bryce Brickley .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (No. 2019/634). All study participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Professor Mark Morgan is a practising general practitioner and is Chair of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners Expert Committee for Quality Care. Ms. Kellie Trigger manages Gold Coast Primary Health Network Consumer Advisory Committee. All remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: supplementary table 1.

. Participant Suggestions to Improve the Model.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Brickley, B., Williams, L.T., Morgan, M. et al. Putting patients first: development of a patient advocate and general practitioner-informed model of patient-centred care. BMC Health Serv Res 21 , 261 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06273-y

Download citation

Received : 25 June 2020

Accepted : 12 March 2021

Published : 20 March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06273-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- General practitioners

- Primary health care

- General practice

- Qualitative description

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

How Nurses Can Advocate for Patients

- Nurse advocacy is crucial to safeguarding patient outcomes, protecting against social injustice, and mediating obstacles to quality patient care.

- Although the concept of nurse advocacy is still poorly conceptualized, the actions are often easily recognized and may be one of the most important responsibilities of an RN.

- Patient advocacy is crucial to patient care to help them navigate the healthcare system, including billing, medical care, insurance, and assisting with legal issues.

Patients within a clinical facility or hospital often find the situation bewildering. It can make them feel nervous and anxious, which is often driven by a lack of knowledge about how things work. When patients are overwhelmed, they’re unable to advocate for themselves and must rely on nurses to be their voice and keep them informed about treatment and procedures.

In a study , 25 registered nurses described patient advocacy as educating patients, being the patient’s voice, and providing quality care. Yet the scope of patient advocacy is much greater. Explore what it means to be a patient advocate and how nurses can advocate for their patients.

Are you ready to earn your online nursing degree?

What It Means To Be an Advocate for Patients

Patient advocacy is so crucial to patient care that many hospitals have these positions to help patients through the healthcare system. Patient advocates communicate with providers and help ensure patients have the information they need to make independent decisions about their care.

Enabling patients to make independent decisions values and safeguards their rights, protects them from incompetency, and safeguards their health and wellness. Although the concept of patient advocacy is still poorly conceptualized, the actions are often easily recognized.

Some believe patient advocacy is one of the most important responsibilities of an RN. Nurses are the patient’s first point of contact with the healthcare system and often the last one as well.

Nurse advocacy includes helping patients navigate the healthcare system through medical care, billing, and insurance. It also involves assisting patients with legal concerns and issues. Patients have come to rely on nurses to support their autonomy, keep them safe, and educate them about their condition and the healthcare system.

Popular Online RN-to-BSN Programs

Learn about start dates, transferring credits, availability of financial aid, and more by contacting the universities below.

How to Advocate for Patients

Nurse advocacy centers on respecting patients’ dignity, treating all patients equally, protecting their rights, and preventing undue suffering. While specific steps nurses help advocate for patients with medical trauma , mental health conditions , and during labor and delivery , all nurses can advocate for patients using several simple strategies.

Communicate with the Healthcare Team

Ensuring proper patient care requires more than making the right diagnosis and performing procedures. Communication is a crucial component to ensuring good patient outcomes and high patient satisfaction. Yet, collaboration and communication do not occur without effort.

Patients must communicate symptoms, concerns, and goals with their healthcare team. Unfortunately, many people are overwhelmed or intimidated by healthcare providers. Nurses play a vital role in ensuring their patient’s information is communicated, which significantly influences patient outcomes.

Educate Patients and their Families

Patient outcomes and the risk of rehospitalization also depend on a patient’s compliance with recommendations. Nurses are in a unique position to advocate for their patients through education and support.

While a physician may strongly recommend a patient stop smoking, nurses can advocate for patients by providing them with outpatient programs to help them accomplish that goal. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , 6 out of 10 adults in the U.S. have at least one chronic disease.

Lifestyle changes can significantly impact chronic diseases, such as nutrition, physical activity, and excessive alcohol use. Nurses can educate patients and families, which may have a meaningful impact on patients’ motivation to change their habits.

Protect Patient Rights

According to the National Institutes of Health , patients have rights while volunteering in clinical research. These rights are often incorporated into a healthcare facility’s “Patient Bill of Rights,” and include the right to be safe and receive respectful care, complete information about their diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, and enough information to give informed consent.

Ensure Patient Safety

Ensuring a patient’s safety is a basic right of every patient within a healthcare facility. Nurses are on the front line of providing patient care while communicating with the healthcare team. One way that nurses ensure patient safety is to confirm the five rights of medication administration (the right patient, the right drug, the right time, the right dose, and the right route) before giving any medication to a patient.

The FDA receives nearly 100,000 reports each year of medication errors, some of which occur in hospitals. These are among the most common medical errors and are estimated to harm at least 1.5 million people each year and result in 7,000-9,000 deaths .

Nurses can advocate for patient safety by lobbying their hospitals for safe nurse-to-patient staffing ratios, appropriate in-house education, and safe working conditions. Advocacy to ensure patient safety also extends to nurses remaining vigilant during their shift, consistently monitoring patient conditions, and increasing patient engagement in treatment.

Advocate for Resources/Better Working Conditions

Nurses have a responsibility to advocate for better working conditions and adequate resources to care for their patients. Rising stress levels in patients, families, and medical staff have consequences.

One survey of healthcare workers published in The Lancet reported 82% of respondents said they had received threats and physical aggression, 21% reported severe wounding of a healthcare worker or patients, and 27% reported the staff was threatened by weapons.

Nurses have a responsibility to themselves and their patients to help create a safe environment. While they cannot do it on their own, together with administration and management, nurses can lead the way in developing processes that protect those concerned.

Address Barriers to Care

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted many of the barriers to care that exist for low-income families and vulnerable populations. Nurses can advocate within their institution and local community to reduce or eliminate barriers to healthcare in the patient populations they serve.

The particular strategies may be specific to the population. Providing equitable healthcare may begin with educating other healthcare providers or legislators about the inequities in the system and suggesting processes that can contribute to a solution.

Support Patient Autonomy

Patients must make autonomous and independent decisions about their healthcare if providers expect them to follow through with recommendations after discharge. However, in some cases, patients may feel railroaded into the decisions within the hospital system.

Once they return home, they may revert to their old habits, which increases the risk of rehospitalization. Nurses can help support patient autonomy by protecting patients’ right to make their own decisions and encouraging them to request all the necessary information.

For some patients, that may mean deciding to forgo chemotherapy after a diagnosis of cancer, and for others it might mean deciding to enroll in a community cardiac rehabilitation program to regain their strength and function after a heart attack. Ultimately, patients must make those decisions because they are the ones expected to follow through on those choices.

Nurses are frontline workers — a role where patient advocacy is required to fulfill their job responsibilities. Nurses must continue to provide quality care, compassion, and advocacy for patient safety and outcomes.

About Chronic Diseases . (2023). CDC

Medication Errors . (2019). AMCP

Mishra, V et al. Health Inequalities During COVID-19 and Their Effects on Morbidity and Mortality . (2021). NIH

Nsiah, C et al. Registered Nurses’ description of patient advocacy in the clinical setting . (2019). National Library of Medicine

Patient Bill of Rights . (2021). NIH

Tariq, R et al. Medication Dispensing Errors and Prevention . (2023). NIH

Thornton, J et al. Violence against health workers rises during COVID-19 . (2022). NIH

Working to Reduce Medication Errors . (2019). FDA

You might be interested in

The Benefits of Nurse-to-Patient Staffing Ratio Laws and Regulations

Mandated staffing ratios are a proven way to ensure patients get the care they need. Find out how nurse-to-patient ratios can improve healthcare.

How to Advocate for Yourself as a New Nurse

As a new nurse you might be thinking how do I advocate for myself? These five ways to advocate for yourself will have you feeling confident and in control of your work/life balance.

Nurse Activism: 15 Ways Nurses Can Affect Real Change

Nurse activism is an important factor in healthcare reform. These are 15 ways nurses can make a real difference in the healthcare system.

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

- LinkedIn Icon

“Advocacy Case Studies” Debuts with Story of How to Advance and Expand Newborn Screening through State Legislation :

Last week, we are introducing a new feature to our journal entitled “Advocacy Case Studies.”

This new section is based on your suggestions. The format for writing an “Advocacy Case Study” is described in our Author Guidelines . With advocacy being such a key part of what we need to be doing as pediatric health care professionals, what better way to share our successes than by publishing them in our journal? Please consider writing a case study of something you have successfully (or even unsuccessfully) advocated for so this section becomes a regular feature of our journal each and every month.

Advertising Disclaimer »

Affiliations

- Pediatrics On Call

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.