- Share on twitter (New window)

- Share on facebook (New window)

- Share on email (New window)

- Share on linkedin (New window)

- Olympic Studies Center

- Other sites

- Olympic World Library Network

- Go to the menu

- Go to the content

- Go to the search

- OSC Catalogue

- INDERSCIENCE

- Search in all sources

Doping in sport : a behavioural economics perspective / Matthew Leadbetter

Leadbetter, Matthew

Edited by University of Kent - 2020

This thesis primarily aims to provide a solid theoretical understanding behind the incentive structures, decision making and rationality of athletes who decide to utilize doping decisions within a competitive sporting contest. This thesis analyzes the rationality behind eliciting a doping decision, outline a two-stage model of doping in sport in which athletes choose how much to dope and then how much effort to exert, with payoffs determined by an all-pay auction. The author also shows that a winner-takes-all prize structure leads to maximum effort (when effort can be monitored) but also maximum cheating when it cannot and explore the complimentary idea that people behave more dishonestly in a sporting environment than they do in other environments through theoretical and experimental analysis.

- Description

- A doctoral thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of philosophy in the School of Economics, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Kent, 2020.

- Academic dissertations

- Export HTML

- Export RIS (Zotero)

Consult online

Issus de la même oeuvre, what do you think of this resource give us your opinion.

Fields marked with the symbol * are mandatory.

Export in progress

Change your review, memorise the search.

The search will be preserved in your account and can be re-run at any time.

Your alert is registered

You can manage your alerts directly in your account

Subscribe me to events in the same category

Subscribe to events in the category and receive new items by email.

Frame sharing

Copy this code and paste it on your site to display the frame

Or you can share it on social networks

- Share on twitter(New window)

- Share on facebook(New window)

- Share on email(New window)

- Share on print(New window)

- Share on linkedin(New window)

Confirm your action

Are you sure you want to delete all the documents in the current selection?

Choose the library

You wish to reserve a copy.

Register for an event

Registration cancellation.

Warning! Do you really want to cancel your registration?

Add this event to your calendar

Exhibition reservation.

Doping in Sport: A Behavioural Economics Perspective

Leadbetter, Matthew (2020) Doping in Sport: A Behavioural Economics Perspective. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. ( KAR id:79890 )

This thesis primarily aims to provide a solid theoretical understanding behind the incentive structures, decision making and rationality of athletes who decide to utilize doping decisions within a competitive sporting contest. This thesis analyzes the rationality behind eliciting a doping decision, outline a two-stage model of doping in sport in which athletes choose how much to dope and then how much effort to exert, with payoffs determined by an all-pay auction. We also show that a winner-takes-all prize structure leads to maximum effort (when effort can be monitored) but also maximum cheating when it cannot and explore the complimentary idea that people behave more dishonestly in a sporting environment than they do in other environments through theoretical and experimental analysis.

University of Kent Author Information

Leadbetter, matthew..

- Link to SensusAccess

- EPrints3 XML

- Depositors only (login required):

Total unique views for this document in KAR since July 2020. For more details click on the image.

Doping Prevalence in Competitive Sport: Evidence Synthesis with "Best Practice" Recommendations and Reporting Guidelines from the WADA Working Group on Doping Prevalence

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Kinesiology, California State University Fullerton, 800 N State College Blvd, Fullerton, CA, 92834, USA. [email protected].

- 2 Kingston University London, Kingston upon Thames, UK.

- 3 University of Münster, Münster, Germany.

- 4 Doping Authority Netherlands, Capelle aan den IJssel, The Netherlands.

- 5 Penn State University, State College, USA.

- 6 University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland.

- 7 University of Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands.

- PMID: 33900578

- DOI: 10.1007/s40279-021-01477-y

Background: The prevalence of doping in competitive sport, and the methods for assessing prevalence, remain poorly understood. This reduces the ability of researchers, governments, and sporting organizations to determine the extent of doping behavior and the impacts of anti-doping strategies.

Objectives: The primary aim of this subject-wide systematic review was to collate and synthesize evidence on doping prevalence from published scientific papers. Secondary aims involved reviewing the reporting accuracy and data quality as evidence for doping behavior to (1) develop quality and bias assessment criteria to facilitate future systematic reviews; and (2) establish recommendations for reporting future research on doping behavior in competitive sports to facilitate better meta-analyses of doping behavior.

Methods: The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used to identify relevant studies. Articles were included if they contained information on doping prevalence of any kind in competitive sport, regardless of the methodology and without time limit. Through an iterative process, we simultaneously developed a set of assessment criteria; and used these to assess the studies for data quality on doping prevalence, potential bias and reporting.

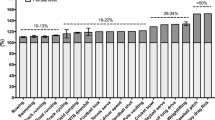

Results: One-hundred and five studies, published between 1975 and 2019,were included. Doping prevalence rates in competitive sport ranged from 0 to 73% for doping behavior with most falling under 5%. To determine prevalence, 89 studies used self-reported survey data (SRP) and 17 used sample analysis data (SAP) to produce evidence for doping prevalence (one study used both SRP and SAP). In total, studies reporting athletes totaled 102,515 participants, (72.8% men and 27.2% women). Studies surveyed athletes in 35 countries with 26 involving athletes in the United States, while 12 studies examined an international population. Studies also surveyed athletes from most international sport federations and major professional sports and examined international, national, and sub-elite level athletes, including youth, masters, amateur, club, and university level athletes. However, inconsistencies in data reporting prevented meta-analysis for sport, gender, region, or competition level. Qualitative syntheses were possible and provided for study type, gender, and geographical region. The quality assessment of prevalence evidence in the studies identified 20 as "High", 60 as "Moderate", and 25 as "Low." Of the 89 studies using SRP, 17 rated as "High", 52 rated as "Moderate", and 20 rated as "Low." Of the 17 studies using SAP, 3 rated as "High", 9 rated as "Moderate", and 5 rated as "Low." Examining ratings by year suggests that both the quality and quantity of the evidence for doping prevalence in published studies are increasing.

Conclusions: Current knowledge about doping prevalence in competitive sport relies upon weak and disparate evidence. To address this, we offer a comprehensive set of assessment criteria for studies examining doping behavior data as evidence for doping prevalence. To facilitate future evidence syntheses and meta-analyses, we also put forward "best practice" recommendations and reporting guidelines that will improve evidence quality.

© 2021. The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

Publication types

- Meta-Analysis

- Systematic Review

- Doping in Sports*

- Surveys and Questionnaires

Doping in Sport: A Review of Elite Athletes’ Attitudes, Beliefs, and Knowledge

- Review Article

- Published: 27 March 2013

- Volume 43 , pages 395–411, ( 2013 )

Cite this article

- Jaime Morente-Sánchez 1 , 2 &

- Mikel Zabala 1 , 2

21k Accesses

126 Citations

70 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Doping in sport is a well-known phenomenon that has been studied mainly from a biomedical point of view, even though psychosocial approaches are also key factors in the fight against doping. This phenomenon has evolved greatly in recent years, and greater understanding of it is essential for developing efficient prevention programmes. In the psychosocial approach, attitudes are considered an index of doping behaviour, relating the use of banned substances to greater leniency towards doping. The aim of this review is to gather and critically analyse the most recent publications describing elite athletes’ attitudes, beliefs and knowledge of doping in sport, to better understand the foundations provided by the previous work, and to help develop practical strategies to efficiently combat doping. For this purpose, we performed a literature search using combinations of the terms “doping”, “sport”, “elite athletes”, “attitudes”, “beliefs”, “knowledge”, “drugs”, and “performance-enhancing substances” (PES). A total of 33 studies were subjected to comprehensive assessment using articles published between 2000 and 2011. All of the reports focused on elite athletes and described their attitudes, beliefs and knowledge of doping in sport. The initial reasons given for using banned substances included achievement of athletic success by improving performance, financial gain, improving recovery and prevention of nutritional deficiencies, as well as the idea that others use them, or the “false consensus effect”. Although most athletes acknowledge that doping is cheating, unhealthy and risky because of sanctions, its effectiveness is also widely recognized. There is a general belief about the inefficacy of anti-doping programmes, and athletes criticise the way tests are carried out. Most athletes consider the severity of punishment is appropriate or not severe enough. There are some differences between sports, as team-based sports and sports requiring motor skills could be less influenced by doping practices than individual self-paced sports. However, anti-doping controls are less exhaustive in team sports. The use of banned substance also differs according to the demand of the specific sport. Coaches appear to be the main influence and source of information for athletes, whereas doctors and other specialists do not seem to act as principal advisors. Athletes are becoming increasingly familiar with anti-doping rules, but there is still a lack of knowledge that should be remedied using appropriate educational programmes. There is also a lack of information on dietary supplements and the side effects of PES. Therefore, information and prevention are necessary, and should cater to the athletes and associated stakeholders. This will allow us to establish and maintain correct attitudes towards doping. Psychosocial programmes must be carefully planned and developed, and should include middle- to long-term objectives (e.g. changing attitudes towards doping and the doping culture). Some institutions have developed or started prevention or educational programmes without the necessary resources, while the majority of the budget is spent on anti-doping testing. Controls are obviously needed, as well as more efficient educational strategies. Therefore, we encourage sporting institutions to invest in educational programmes aimed at discouraging the use of banned substances. Event organizers and sport federations should work together to adapt the rules of each competition to disincentivize dopers. Current research methods are weak, especially questionnaires. A combination of qualitative and quantitative measurements are recommended, using interviews, questionnaires and, ideally, biomedical tests. Studies should also examine possible geographical and cultural differences in attitudes towards doping.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Transgender Women in the Female Category of Sport: Perspectives on Testosterone Suppression and Performance Advantage

The importance of muscular strength in athletic performance, the mental health of elite athletes: a narrative systematic review.

Bloodworth AJ, McNamee M. Clean Olympians? Doping and anti-doping: the views of talented young British athletes. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(4):276–82.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

WADA (2009a). World anti-doping code [online]. http://www.wada-ama.org/en/World-Anti-Doping-Program/Sports-and-Anti-Doping-Organizations/The-Code . Accessed 29 Nov 2011.

Mottram DR. Banned drugs in sport: does the International Olympic Committee (IOC) list need updating? Sports Med. 1999;27(1):1–10.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

World Anti-Doping Agency. The World anti-doping code. Montreal: WADA; 2003.

Google Scholar

Gucciardi DF, Jalleh G, Donovan RJ. An examination of the Sport Drug Control Model with elite Australian athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(6):469–76.

Bahrke MS, Yesalis CE, editors. Performance enhancing substances in sport and exercise. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2002.

Backhouse S, McKenna J, Robinson S, et al. Attitudes, behaviours, knowledge and education—drugs in sport: past present and future [online]. Canada: World Anti-Doping Agency; 2007. http://www.wada-ama.org/rtecontent/document/Backhouse_et_al_Full_Report.pdf . Accessed 29 Nov 2011.

Petroczi A, Aidman E. Measuring explicit attitude toward doping: review of the psychometric properties of the Performance Enhancement Attitude Scale. Psychol Sport Exer. 2009;10:390–6.

Article Google Scholar

Dodge T, Jaccard JJ. Is abstinence an alternative? Predicting adolescent athletes’ intentions to use performance enhancing substances. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(5):703–11.

Donovan RJ, Egger G, Kapernick V, et al. A conceptual framework for achieving performance enhancing drug compliance in sport. Sports Med. 2002;32(4):269–84.

Lucidi F, Zelli A, Mallia L, et al. The social-cognitive mechanisms regulating adolescents’ use of doping substances. J Sports Sci. 2008;26(5):447–56.

Strelan P, Boeckmann RJ. A new model for understanding performance enhancing drug use by elite athletes. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2003;15:176–83.

WADA (2009b). World anti-doping agency: Education [online]. http://www.wada-ama.org/en/Education-Awareness/ . Accessed 29 Nov 2011.

Vangrunderbeek H, Tolleneer J. Student attitudes towards doping in sport: Shifting from repression to tolerance? Int Rev Sociol Sport. 2010;46(3):346–57.

Alaranta A, Alaranta H, Holmila J, et al. Self-reported attitudes of elite athletes towards doping: differences between type of sport. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27(10):842–6.

Dunn M, Thomas JO, Swift W, et al. Drug testing in sport: the attitudes and experiences of elite athletes. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(4):330–2.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage Publications; 1997.

Dolan P, Hallsworth M, Halpern D, et al. Influencing behavior: the mindspace way. J Econ Psychol. 2012;33:264–77.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: some unresolved issues. Organ Behav Hum. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Lucidi F, Grano C, Leone L, et al. Determinants of the intention to use doping substances: an empirical contribution in a sample of Italian adolescents. Int J Sport Psychol. 2004;35(2):133–48.

Striegel H, Vollkommer G, Dickhuth HH. Combating drug use in competitive sports: an analysis from the athletes’ perspective. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2002;42(3):354–9.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Pitsch W, Emrich E, Kleinm M. Doping in elite sports in Germany: results of a www survey. Eur J Sport Soc. 2007;4(2):89–102.

Nieper A. Nutritional supplement practices in UK junior national track and field athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(9):645–9.

Kim J, Kang SK, Jung HS, et al. Dietary supplementation patterns of Korean Olympic athletes participating in the Beijing 2008 Summer Olympic Games. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2011;21(2):166–74.

PubMed Google Scholar

Erdman KA, Fung TS, Doyle-Baker PK, et al. Dietary supplementation of high-performance Canadian athletes by age and gender. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(6):458–64.

Bloodworth AJ, Petróczi A, Bailey R, et al. Doping and supplementation: the attitudes of talented young athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22(2):293–301.

Lentillon-Kaestner V, Carstairs C. Doping use among young elite cyclists: a qualitative psychosociological approach. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(2):336–45.

Lentillon-Kaestner V, Hagger MS, Hardcastle S. Health and doping in elite-level cycling. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22(5):596–606.

Dunn M, Thomas JO, Swift W, et al. Elite athletes’ estimates of the prevalence of illicit drug use: evidence for the false consensus effect. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012;31(1):27–32.

Petróczi A, Mazanov J, Nepusz T, et al. Comfort in big numbers: does over-estimation of doping prevalence in others indicate self-involvement? J Occup Med Toxicol. 2008;5:3–19.

Uvacsek M, Nepusz T, Naughton DP, et al. Self-admitted behavior and perceived use of performance-enhancing vs psychoactive drugs among competitive athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(2):224–34.

Tangen JO, Breivik G. Doping games and drug abuse. Sportwissenschaft. 2001;31:188–98.

Peretti-Watel P, Guagliardo V, Verger P, et al. Attitudes toward doping and recreational drug use among French elite student athletes. Sociol Sport J. 2004;21:1–17.

De Hon O, Eijs I, Havenga A. Dutch elite athletes and anti-doping policies. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(4):341–2.

Mottram D, Chester N, Atkinson G, et al. Athletes’ knowledge and views on OTC medication. Int J Sports Med. 2008;29(10):851–5.

Dascombe BJ, Karunaratna M, Cartoon J, et al. Nutritional supplementation habits and perceptions of elite athletes within a state-based sporting institute. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(2):274–80.

Breivik G, Hanstad DV, Loland S. Attitudes towards use of performance-enhancing substances and body modification techniques: a comparison between elite athletes and the general population. Sport Soc. 2009;12(6):737–54.

Connor JM, Mazanov J. Would you dope? A general population test of the Goldman dilemma. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(11):871–2.

Sas-Nowosielski K, Swiatkowska L. Goal orientations and attitudes toward doping. Int J Sports Med. 2008;29(7):607–12.

Waddington I, Malcolm D, Roderick M, et al. Drug use in English professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(4):e18.

Barkoukis V, Lazuras L, Tsorbatzoudisa H, et al. Motivational and sportspersonship profiles of elite athletes in relation to doping behavior. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2011;12(3):205–12.

Peretti-Watel P, Pruvost J, Guagliardo V, et al. Attitudes toward doping among young athletes in Provence. Sci Sports. 2005;20(1):33–40.

Lazuras L, Barkoukis V, Rodafinos A, et al. Predictors of doping intentions in elite-level athletes: a social cognition approach. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2010;32(5):694–710.

Chester N, Reilly T, Mottram DR. Over-the-counter drug use amongst athletes and non-athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2003;43(1):111–8.

Striegel H, Ulrich R, Simon P. Randomized response estimates for doping and illicit drug use in elite athletes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;106(2–3):230–2.

Pitsch W. The science of doping’’ revisited: Fallacies of the current anti-doping regime. Eur J Sport Sci. 2009;9(2):87–95.

Berry DA. The science of doping. Nature. 2008;454(7205):692–3.

Callaway E. Sports doping: racing just to keep up. Nature. 2011;475(7356):283–5.

Hanstad DV, Loland S. Elite athletes’ duty to provide information on their whereabouts: justifiable anti-doping work or an indefensible surveillance regime? Eur J Sport Sci. 2009;9(1):3–10.

D’Angelo C, Tamburrini C. Addict to win? A different approach to doping. J Med Ethics. 2010;36(11):700–7.

Alaranta A, Alaranta H, Heliövaara M, et al. Ample use of physician-prescribed medications in Finnish elite athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27(11):919–25.

Somerville SJ, Lewis M, Kuipers H. Accidental breaches of the doping regulations in sport: is there a need to improve the education of sportspeople? Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(8):512–6.

Peters C, Schulz T, Oberhoffer R, et al. Doping and doping prevention: knowledge, attitudes and expectations of athletes and coaches. Deutsche zeitschrift fur sportmedizin. 2009;60(3):73–8.

Thomas JO, Dunn M, Swift W, et al. Illicit drug knowledge and information-seeking behaviours among elite athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(4):278–82.

Backhouse S, McKenna J. Doping in sport: a review of medical practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs. Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22:198–202.

Huang SH, Johnson K, Pipe AL. The use of dietary supplements and medications by Canadian athletes at the Atlanta and Sydney Olympic Games. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16(1):27–33.

Lamont-Mills A, Christensen S. “I have never taken performance enhancing drugs and I never will”: drug discourse in the Shane Warne case. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18(2):250–8.

WADA. Social science research 2008 call for proposal [online]. http://www.wada-ama.org/rtecontent/document/Call_for_Proposals_2009_En.pdf . Accessed 26 Dec 2011.

Maughan RJ, Depiesse F, Geyer H. International Association of Athletics Federations: the use of dietary supplements by athletes. J Sports Sci 2007; 25 Suppl. 1:S103–13. Review. Erratum in: J Sports Sci 2009; 27 (6): 667.

Thomas JO, Dunn M, Swift W, et al. Elite athletes’ perceptions of the effects of illicit drug use on athletic performance. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20(3):189–92.

Perneger TV. Speed trends of major cycling races: does slower mean cleaner? Int J Sports Med. 2010;31(4):261–4.

Dunn M, Thomas JO. A risk profile of elite Australian athletes who use illicit drugs. Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):144–7.

Zabala M, Sanz L, Durán J, et al. Doping and professional road cycling: perspective of cyclists versus team managers. J Sports Sci Med. 2009;8(11):102–3.

Corrigan B, Kazlauskas R. Medication use in athletes selected for doping control at the Sydney Olympics (2000). Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(1):33–40.

Zabala M, Atkinson G. Looking for the “athlete 2.0”: a collaborative challenge [online]. J Sci Cycling 2012; 1 (1): 1–2. http://www.jsc-journal.com/ojs/index.php?journal=JSC&page=article&op=view&path[]=17&path[]=35. Accessed 03 Aug 2012.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. This study was supported by a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education (AP2009-0529).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Physical Education and Sport, Faculty of Sport Sciences, University of Granada, c/ Carretera Alfacar s/n, 18011, Granada, Spain

Jaime Morente-Sánchez & Mikel Zabala

Doping Prevention Area, Spanish Cycling Federation, Madrid, Spain

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mikel Zabala .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Morente-Sánchez, J., Zabala, M. Doping in Sport: A Review of Elite Athletes’ Attitudes, Beliefs, and Knowledge. Sports Med 43 , 395–411 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0037-x

Download citation

Published : 27 March 2013

Issue Date : June 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0037-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Elite Athlete

- Perceive Behavioural Control

- Elite Sport

- Randomize Response Technique

- Doping Behaviour

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Perspective article, the purpose and effectiveness of doping testing in sport.

- 1 Science and Medicine, Anti-Doping Norway, Oslo, Norway

- 2 Anti-Doping Norway, Oslo, Norway

Maintaining an effective testing program is critical to the success and credibility of the anti-doping movement. However, a low detection ratio compared to the assumed real prevalence of sport doping has led some to question and criticize the effectiveness of the current testing system. In this perspective article, we review the results of the global testing program, discuss the purpose of testing, and compare benefits and limitations of performance indicators commonly used to evaluate testing efforts. We suggest that an effective testing program should distinguish between preventive testing and testing aimed at detecting the use of prohibited substances and prohibited methods. In case of preventive testing, the volume of the test program in terms of number of samples, tests and analyses is likely to be positively related to the extent of the deterrent effect achieved. However, there is a lack of literature on how the deterrent effect works in the practical context of doping testing. If the primary goal is to detect doping, the testing must be risk- and intelligence-based, and quality in test planning is more important than quantity in sample collection. The detection ratio can be a useful tool for evaluating the effectiveness of doping testing, but for the calculation one should take into account the number of athletes tested and not just the number of collected samples, as the former would provide a more precise measure of the tests’ ability to detect doping among athletes.

Introduction

For decades, athletes have used performance-enhancing substances and methods to improve athletic performance and gain a competitive edge. Mainly to protect the health of athletes from potentially harmful doping practices, the first significant anti-doping initiatives were introduced in the 1970s ( 1 ). In response to growing concerns, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) was established in 1999 by the Sport Movement and Governments of the world to co-ordinate the global fight against doping and to protect athletes’ fundamental right to participate in doping-free sport, taking over the responsibility for anti-doping from the International Olympic Committee Medical Commission. A few years later, WADA released the first edition of the World Anti-Doping Code (WADC). The WADC was quickly adopted and enforced by international sport organisations and National Anti-Doping Organisations (NADOs) worldwide, and acknowledged by governments through the UNESCO convention ( 2 ). Today, the WADC together with eight mandatory International Standards and Technical Documents and 12 non-mandatory Guidelines constitutes the World Anti-Doping Program, which seeks to harmonize anti-doping policies, rules and regulations across sports and public authorities ( 3 ).

Since the establishment of WADA, anti-doping has become increasingly multi-disciplinary. To prevent and detect doping, modern anti-doping programs include disciplines such as analytical chemistry, education, forensic science, pharmacology, physiology, psychology, and law. However, despite the increasing complexity of the World Anti-Doping Program, the collection and analysis of biological samples from athletes accounts for more than half of the global anti-doping budget ( 4 ) making it the main activity for most anti-doping organisations (ADOs). Providing effective and cost-efficient testing programs is therefore essential for the success and credibility of the anti-doping movement.

The word e ffective is used several times in the WADC. For example, the first part of the Code, which describes the purpose, scope and organisation of the World Anti-Doping Program and the WADC, states in relation to detection that “an effective testing and investigations system not only enhances a deterrent effect , but also is effective in protecting clean athletes and the spirit of sport by catching those committing anti-doping rule violations, while also helping to disrupt anyone engaged in doping behaviour” [p. 9, ( 3 )]. The current International Standard for Testing and Investigations provide several recommendations for conducting effective testing ( 5 ), however, it is still somewhat unclear how it can be measured and evaluated.

Doping testing practices have not been immune to criticism. Most notably, a significantly lower detection ratio of positive samples compared to the assumed true prevalence of athletes doping has led some to question and criticise the effectiveness of the doping efforts ( 6 , 7 ), suggested that current practices are unfit to detect doping ( 8 ), and that anti-doping authorities are more concerned with the number of samples collected than on exposing doping ( 9 ).

In this article, we critically discuss the concept of effectiveness in the context of doping testing in sport, the purposes of testing, as well as the validity of the figures and performance indicators that are often used to measure and evaluate its success. We argue that there is a need for more precise and harmonized indicators to better measure the doping test regimes’ ability to detect and deter doping, and that implementation of more intelligent and data-driven testing by ADOs may increase the quality and effectiveness of the global testing program.

Determining the success of doping testing—does testing numbers count?

The unofficial parameter used by anti-doping practitioners to measure whether adequate measures are taken to combat doping has traditionally been the number of samples or tests carried out by a given ADO or within a specific sport or country. In general, the notion has been that the more you test, the better program you have. However, global test statistics from the last two decades suggest that increased testing has not translated into a corresponding increase in the proportion of positive tests ( 6 , 10 ). According to the WADA Anti-doping Testing Figures report, which was first presented in its current form in 2012, there was a 35% increase in the total number of annual samples reported into WADA's Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) from 2012 (206 391 samples) to 2019 (278 047 samples) ( 11 ), after which the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in a widespread suspension or reduction in most anti-doping activities in 2020 ( 12 ). Interestingly, the number of samples with a positive finding for a prohibited substance or method, what is referred to as an Adverse Analytical Finding (AAF), only increased 6% in the same period (2,549 to 2,702 AAFs).

Adverse Analytical Findings, however, should not be confused with doping violations, as some AAFs are dismissed for medical or other reasons. More appropriate figures for assessing the success of the global testing efforts in detecting doping can instead be found in the WADA ADRV reports, first released in 2013. An ADRV is defined as a doping case for which a final decision has been rendered and a sanction was imposed against the athlete or athlete support personnel ( 3 ). The ADRVs are separated into analytical ADRVs, which are based on AAFs, and non-analytical ADRVs, which are based on other types of rule violations. Statistics on ADRVs may offer several advantages when evaluating testing efforts, however, not all ADRVs are related to intentional doping as some AAFs are caused by inadvertent ingestion of prohibited substance ( 13 ), for example through food or dietary supplements ( 14 , 15 ).

Calculating the detection ratio

A starting point for evaluating the effectiveness of testing programs is to calculate and assess the detection ratio, which can be done in several ways. Using analytical ADRVs and all samples collected by ADOs worldwide (except samples for the Athlete Biological Passport as these are not for direct detection of prohibited substances or methods) gives a detection ratio of 0.66% for the period 2013–2019 (10 759 analytical ADRVs from 1 640 999 collected samples) ( 16 ). In contrast to analytical ADRVs, most types of non-analytical ADRVs are not related to testing and should rightfully not be included when evaluating effects of doping testing. There are certain exceptions, such as (a) Use or attempted use of a prohibited substance or method, (b) Evading, refusing, or failing to submit to sample collection, and (c) Tampering with any part of a doping control, all of which are potentially related to testing ( 3 ). Adding these non-analytical ADRVs to the analytical ADRVs result in a slightly higher ADRV-to-sample ratio for the period 2013–2019, which would still be well under 1%.

The prevalence of athletes doping

Does an ADRV-to-sample ratio of less than one percent reflect that the current testing strategy is successful, or rather that it has severe limitations in exposing cheaters? For any meaningful evaluation of the detection ratio to take place it should be compared with the relative number of athletes doping. Unfortunately, the true prevalence of sport doping has been challenging to estimate with any degree of certainty ( 17 ). A recent evidence synthesis report a doping prevalence in competitive sport between 0% and 73% ( 13 ). The high variation between studies is not surprising considering the different methodological approaches used to measure prevalence ( 13 ), and given the varying benefits of doping across sports, differences in sporting cultures, athletes’ knowledge of anti-doping rules etc. ( 18 , 19 ). The importance of reliable methods for adequate assessment of doping prevalence has been acknowledged by WADA, which has established a Prevalence Working Group to provide more accurate numbers.

The purpose of doping testing—detection vs. deterrence

Doping testing is not exclusively undertaken to obtain analytical evidence of the use of prohibited substances or methods in the form of positive samples. Although the analytical methods used to analyse biological samples from athletes are continuously improving [e.g., ( 20 , 21 )], testing in itself continue to have several limitations in exposing doping, including but not limited to a short window of detection and low test sensitivity for certain substances, and high predictability of testing ( 8 ). In view of these shortcomings, it has been suggested that it is necessary to carry out 16–50 tests per athlete per year to uncover all doping cases ( 8 ). In addition to being ethically questionable, the cost of such a hypothetical program would not be economically viable. Considering the difficulties of the detection-based approach, it has thus been argued that the global testing program is mainly dependent on deterring athletes from making the decision to dope by risk of detection and severe sanctions ( 22 ).

According to the theory of deterrence, if athletes perceive that there is a high probability of detection and they consider the consequences to be severe, they are less likely to break the rules ( 23 , 24 ). For sanctions following positive doping tests to provide credible threats and act as a deterrent to doping practices, it is estimated that the perceived certainty of punishment must be 30% or higher ( 25 ). According to the deterrence theory, the more frequent athletes are tested, and the more samples that are collected, the greater certainty of punishment and thus deterrence is achieved. This effect is likely to apply up to a certain point, where more testing will not result in further increases in deterrence. In line with this, it has been shown that athletes with personal experience with testing and who are tested regularly are more likely to experience a deterrent effect ( 26 ). Conversely, athletes who lack confidence in the system and perceive that doping controls are unable to detect doping do not believe that the current testing program is a strong deterrent ( 27 ). Another key component of deterrence is celerity, i.e., that the sanction are imposed swiftly after the offense for the transgressor to connect the violation with the punishment ( 25 ). How long the Result management process in a doping case lasts before a sanction is imposed will thus affect the athlete's perception of the deterrent effect of testing.

A possible explanation for the reduction in the detection ratio in the global testing program from 2013 to 2019 is that the annual increases in sample collection have resulted in an enhanced deterrent effect among athletes, resulting in fewer relative ADRVs. Such a scenario is in line with how the theory of deterrence can be expected to work in practice. It is not surprising that athletes who are subjected to regular random doping testing experience the risk of being caught so high that they refrain from using prohibited substances.

More research should be carried out to gain a better understanding of how the deterrent effect takes place in the practical context of doping control. Establishing the threshold for when a satisfactory level of deterrence is reached will be of great interest to ADOs and could contribute to more efficient use of testing resources. There is no reason to continue testing an athlete 15 times a year unless there is specific confidential source information indicating doping use, if future research suggests that a satisfactory level of deterrence is achieved with, say, seven randomly assigned annual tests.

Discussion and recommendations for improving testing effectiveness

Several requirements and recommendations has been made in the last decade with the goal to make testing more targeted and effective [e.g., ( 28 )]. Nevertheless, ten years after that the lack of effectiveness in the testing program in sport was discussed by WADA ( 6 ), ADOs are still struggling to detect doping among athletes. In view of the admittedly low detection rate and to meet the criticism that anti-doping has become a “numbers game”, ADOs should consider taking several measures to increase the quality and effectiveness of their testing programs.

Prioritize quality vs. quantity in testing when the goal is to detect doping

Insufficient funding has been used to explain the lack of effectiveness of doping testing ( 6 ). Indeed, doping controls are expensive and all ADOs operate with limited budgets. However, as we have previously discussed, there is no automaticity that administering more doping testing will result in a higher number of positive samples either in absolute or relative terms ( 6 , 9 , 29 , 30 ). Instead of increasing the budget to accommodate increased sample collection and analysis, ADOs should improve the risk assessment process for better target testing. To put it simply, when aiming to detect doping, test smarter, not more.

To gain more knowledge about high-risk athletes and sports in a respective country or region, ADOs should examine their own historic test and ADRV statistics. Sharing of practices on how ADOs use intelligence in the test planning process, and how it affects the detection rates should be encouraged and will contribute to a more data-driven approach to test planning in the anti-doping community.

Invest in building intelligence capabilities

The importance of information-based testing and the use of forensic methods and intelligence ( 28 , 29 , 31 ), as well as cross sectional cooperation ( 32 ) to uncover both analytical and non-analytical rule violations has been increasingly promoted in the last decade. ADOs should therefore invest in human resources which may increase their capability and capacity to gather and use intelligence in test planning and set up a system that allows for the collection and processing of information on possible rule violations. Whistle blowing/tip offs, sport performance data, social media activity, athlete biological profiles, previous testing records, whereabouts information and information from law enforcement are all potential sources of relevant information which could be used to increase the quality of the test planning process. To free up resources to increase investments in intelligence capacity, ADOs can consider reducing some testing in low-risk sports and of athletes with a long and clean record and where there are not indications of rule violations.

Distinguish between tests for deterrence and for detection

In theory, doping controls have both a deterrent effect and the potential to detect doping ( 22 ). In practice, many tests are mainly preventive in the sense that there exist no suspicion or specific information about potential doping use by the tested athlete. The main purpose of these test is to deter the athlete from future use of a prohibited substance or method. Separating the samples collected for preventive purposes from those collected with the aim of detecting doping when calculating the detection ratio would give a more precise picture of the actual ability of doping tests to detect doping.

Improved reporting of test statistics

The annual WADA reports which present global testing numbers and analytical findings represent the best available source of statistics for evaluating global testing efforts. As previously explained, the reports provide various figures that could potentially be used for this purpose, but their current format does not make the content easily accessible to outside observers. It has therefore been suggested to reform WADAs reporting system in order to make it easier to evaluate the impact, efficiency and proportionality of the policies and programmes in place ( 33 ). Improved reporting practices can also in itself contribute to countering doping, in addition to strengthen individual and public trust in the anti-doping system ( 33 ). Gleaves et al. ( 13 ) have recently proposed several recommendations for reporting guidelines relating to measurements of doping behaviour which are also relevant for evaluation of testing efforts. Among these the most significant is the importance of also presenting the number of athletes tested in a given period, sport, or country and not only the number of samples collected. Most athletes are tested several times per year. For example, it is not unusual for high-profile athletes participating in sports that are considered to have a high risk for doping, such as disciplines that require high levels and degrees of specialisation in endurance, strength, or power, to provide ten or more doping samples annually. If twenty athletes together provide two hundred samples over the course of a year, of which one sample comes back positive for a prohibited substance, this would, with normal calculations give a detection ratio of 0.5%. However, it is equally true that five percent of the athletes who were tested returned a positive sample, which gives a completely different conclusion on whether the testing of these twenty athletes was successful in detecting doping or not. By calculating the proportion of ADRVs per number of athletes rather the per number of samples, the detection ratio will probably be closer to the real doping prevalence.

Lastly, the ADRVs are currently grouped as analytical or non-analytical, but neither category fully encompasses the ADRVs related to doping testing. To evaluate the outcome of testing, a new category that includes all test-related ADRVs would be useful.

Conclusions

Consistent and adequate funding is necessary to run a high-quality anti-doping program. However, more funding will not automatically improve the output of testing programs if the resources are not used wisely. Anti-doping organizations’ intelligence and investigation capability and capacity should be strengthened and considered as an integral part of testing operations. If necessary, collecting fewer samples can free up financial resources to enable improved target testing of at-risk athletes and sport environments. Performing high quality risk assessments on both the individual, team and sport discipline level should be considered as pivotal. More studies should be done to examine the relationship between the volume of samples and the deterrent effect. Reducing the number of samples should, however, not come at the expense of the preventive and deterrent effect of doping testing.

Most athletes want to compete clean and support the various measures imposed on them by sport and ADOs ( 34 ). However, there is no automaticity in the fact that this will persist, and some athletes already question the lack of efficiency and equality across sports and countries ( 34 ). To maintain the trust of athletes, governments, and other stakeholders in the world of sports, ADOs should take measures to improve testing effectiveness and facilitate the evaluation of their practices through transparent reporting of testing figures and results ( 33 ).

Finally, anti-doping is more than sample collection and detection ratios. In this article we have limited the discussion to testing. However, a similar exercise should be done for other areas within anti-doping, such as education, which is now considered a cornerstone of global anti-doping efforts, and an important prevention strategy for a successful fight against doping ( 35 ), but where the effect of the majority of the various programs is not well known ( 36 ).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

FL: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Ljungqvist A. Brief history of anti-doping. In: Rabin O, Pitsiladis Y, editors. Acute Topics in Anti-Doping . Basel: Karger (2017). p. 1–10.

Google Scholar

2. Houlihan B, Hanstad DV, Loland S, Waddington I. The world anti-doping agency at 20: progress and challenges. Int J Sport Policy Politics . (2019) 11(2):193–201. doi: 10.1080/19406940.2019.1617765

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. WADA. World Anti-Doping Code 2021 . Montreal, Quebec: World Anti-Doping Agency. (2021).

4. iNADO. Report Capability Register Member NADOs and RADOs . Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia: Bonn (2021).

5. WADA. International Standard Testing and Investigations 2023. Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/isti_2023_w_annex_k_final_clean.pdf (Accessed February 15, 2024).

6. Ayotte C, Parkinson A, Pengilly A, Andrew R, Pound RW. Report to WADA Executive Committe on Lack of Effectiveness of Testing Programs . Montreal: WADA (2013).

7. Pitsch W. Tacit premises and assumptions in anti-doping research. Perform Enhanc Health . (2013) 2(4):144–52. doi: 10.1016/j.peh.2014.07.001

8. Hermann A, Henneberg M. Anti-doping systems in sports are doomed to fail: a probability and cost analysis. J Sports Med Dop . (2014) 4(5):1–12. doi: 10.4172/2161-0673.1000148

9. Martensen CK, Møller V. More money - better anti-doping? Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy . (2017) 24(3):286–94. doi: 10.1080/09687637.2016.1266300

10. Aguilar-Navarro M, Munoz-Guerra J, Del Mar Plara M, Del Coso J. Analysis of doping control test results in individual and team sports from 2003 to 2015. J Sport Health Sci . (2020) 9(2):160–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2019.07.005

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. WADA. Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report . Montreal: WADA (2023). Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/resources/anti-doping-stats/anti-doping-testing-figures-report#resource-download.14.03.2023

12. Lima G, Muniz-Pardos B, Kolliari-Turner A, Hamilton B, Guppy FM, Grivas G, et al. Anti-doping and other sport integrity challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Sports Med Phys Fitness . (2021) 61(8):1173–83. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.21.12777-X

13. Gleaves J, Petroczi A, Folkerts D, de Hon O, Macedo E, Saugy M, et al. Doping prevalence in competitive sport: evidence synthesis with “best practice” recommendations and reporting guidelines from the WADA working group on doping prevalence. Sports Med . (2021) 51(9):1909–34. doi: 10.1007/s40279-021-01477-y

14. Lauritzen F. Dietary supplements as a major cause of anti-doping rule violations. Front Sports Act Living . (2022) 4:868228. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2022.868228

15. Walpurgis K, Thomas A, Geyer H, Mareck U, Thevis M. Dietary supplement and food contaminations and their implications for doping controls. Foods . (2020) 9(8):1012. doi: 10.3390/foods9081012

16. WADA. Anti-Doping Rule Violations (ADRVs) Report - archives. Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/resources/anti-doping-stats/anti-doping-rule-violations-adrvs-report.09.02.23 (Accessed February 15, 2024).

17. Petroczi A, Gleaves J, de Hon O, Sagoe D, Saugy M. Prevalence of doping in sport. In: Mottram D, Chester N, editors. Drugs in Sport . 8 ed. New York: Routledge (2022). p. 37–71.

18. Overbye M, Knudsen ML, Pfister G. To dope or not to dope: elite athletes’ perceptions of doping deterrents and incentives. Perform Enhanc Health . (2013) 2(3):119–34. doi: 10.1016/j.peh.2013.07.001

19. Ring C, Kavussanu M, Simms M, Mazanov J. Effects of situational costs and benefits on projected doping likelihood. Psychol Sport Exerc . (2018) 34:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.09.012

20. Thevis M, Piper T, Thomas A. Recent advances in identifying and utilizing metabolites of selected doping agents in human sports drug testing. J Pharm Biomed Anal . (2021) 205:114312. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2021.114312

21. Thevis M, Kuuranne T, Geyer H. Annual banned-substance review-analytical approaches in human sports drug testing 2021/2022. Drug Test Anal . (2023) 15(1):5–26. doi: 10.1002/dta.3408

22. Bowers LD. Counterpoint: the quest for clean competition in sports: deterrence and the role of detection. Clin Chem . (2014) 60(10):1279–81. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.226175

23. Moston S, Engelberg T, Skinner J. Athletes’ and coaches’ perceptions of deterrents to performance-enhancing drug use. Int J Sport Policy Politics . (2015) 7(4):623–36. doi: 10.1080/19406940.2014.936960

24. Dunn M, Thomas JO, Swift W, Burns L, Mattick RP. Drug testing in sport: the attitudes and experiences of elite athletes. Int J Drug Policy . (2010) 21(4):330–2. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.12.005

25. Bowers LD, Paternoster R. Inhibiting doping in sports: deterrence is necessary, but not sufficient. Sport, Ethics Philos . (2017) 11(1):1–20. doi: 10.1080/17511321.2016.1261930

26. Overbye M. Deterrence by risk of detection? An inquiry into how elite athletes perceive the deterrent effect of the doping testing regime in their sport. Drugs: Educ Prev Policy . (2017) 24(2):206–19. doi: 10.1080/09687637.2016.1182119

27. Overbye M. Doping control in sport: an investigation of how elite athleets perceive and trust the functioning of the doping testing system in their sport. Sport Manag Rev . (2016) 19:6–22. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2015.10.002

28. Dvorak J, Baume N, Botre F, Broseus J, Budgett R, Frey WO, et al. Time for change: a roadmap to guide the implementation of the world anti-doping code 2015. Br J Sports Med . (2014) 48(10):801–6. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093561

29. Lauritzen F, Holden G. Intelligence-based doping control planning improves testing effectiveness - perspectives from a national anti-doping organisation. Drug Test Anal . (2022) 15(5):506–15. doi: 10.1002/dta.3435

30. Aguilar M, Munoz-Guerra J, Plata MDM, Del Coso J. Thirteen years of the fight against doping in figures. Drug Test Anal . (2017) 9(6):866–9. doi: 10.1002/dta.2168

31. WADA. World Anti-Doping Code 2015 . Quebec, Montreal: World-Anti Doping Agency (2015). Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada-2015-world-anti-doping-code.pdf

32. WADA’s 18th Annual Symposium Kicks off by Announcing Exceptional Results from European Intelligence and Investigations Project [Press Release] . Montreal, Quebec: WADA (2024).

33. Kornbeck J. Anti-doping governance and transparency: a European perspective. Int Sports Law J . (2016) 16(1):118–22. doi: 10.1007/s40318-016-0098-8

34. Woolway T, Lazuras L, Barkoukis V, Petróczi A. “Doing what is right and doing it right”: a mapping review of athletes’ perception of anti-doping legitimacy. Int J Drug Policy . (2020) 84:102865. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102865

35. WADA. International Standard for Education . Montreal, Quebec: World-Anti Doping Agency (2021). Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/international_standard_ise_2021.pdf

36. Woolf JR. An examination of anti-doping education initiatives from an educational perspective: insights and recommendations for improved educational design. Perform Enhanc Health . (2020) 8(2–3). doi: 10.1016/j.peh.2020.100178

Keywords: anti-doping, doping control, athlete, clean sport, AAF, ADRV, World Anti-Doping Agency, WADA

Citation: Lauritzen F and Solheim A (2024) The purpose and effectiveness of doping testing in sport. Front. Sports Act. Living 6:1386539. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2024.1386539

Received: 15 February 2024; Accepted: 23 April 2024; Published: 13 May 2024.

Reviewed by:

© 2024 Lauritzen and Solheim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fredrik Lauritzen, [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Subst Abuse Rehabil

Drug abuse in athletes

Claudia l reardon.

Department of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, USA

Shane Creado

Drug abuse occurs in all sports and at most levels of competition. Athletic life may lead to drug abuse for a number of reasons, including for performance enhancement, to self-treat otherwise untreated mental illness, and to deal with stressors, such as pressure to perform, injuries, physical pain, and retirement from sport. This review examines the history of doping in athletes, the effects of different classes of substances used for doping, side effects of doping, the role of anti-doping organizations, and treatment of affected athletes. Doping goes back to ancient times, prior to the development of organized sports. Performance-enhancing drugs have continued to evolve, with “advances” in doping strategies driven by improved drug testing detection methods and advances in scientific research that can lead to the discovery and use of substances that may later be banned. Many sports organizations have come to ban the use of performance-enhancing drugs and have very strict consequences for people caught using them. There is variable evidence for the performance-enhancing effects and side effects of the various substances that are used for doping. Drug abuse in athletes should be addressed with preventive measures, education, motivational interviewing, and, when indicated, pharmacologic interventions.

Introduction

Doping, defined as use of drugs or other substances for performance enhancement, has become an important topic in virtually every sport 1 and has been discovered in athletes of all ages and at every level of competition. 2 – 4 See Table 1 for rates of use of a variety of substances, whether doping agents or recreational substances, among different populations of athletes as reported in various recent research studies. 5 – 10 Of note, self-reports are generally felt likely to yield under-reported figures. 5 Importantly, performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) are not restricted to illegal drugs or prescription medications, such as anabolic steroids. 11 They include dietary supplements and a variety of compounds that are available at grocery and health food stores and online. 12

Substance use rates among different populations of athletes as reported in various recent research studies

Abbreviation: WADA, World Anti-Doping Agency.

Drug abuse in the athlete population may involve doping in an effort to gain a competitive advantage. Alternatively, it may involve use of substances such as alcohol or marijuana without the intent of performance enhancement, since athletes may develop substance use disorders just as any nonathlete may.

Athletes may turn to substances to cope with numerous stressors, including pressure to perform, injuries, physical pain, and retirement from a life of sport (which happens much earlier than retirement from most other careers). 13 Additionally, athletes may be significantly less likely to receive treatment for underlying mental illnesses such as depression. 14 Athletes receive comprehensive treatment and rehabilitation for physical injuries, but this may be less often the case for mental illness, because of their sometimes viewing mental illness as a sign of weakness. 14 Untreated mental illness is often associated with substance use, perhaps in an effort to self-treat. Alternatively, substances of abuse may cause mental illness. 15

We will especially focus on doping in this review, which specifically aims to serve as a single paper that provides a broad overview of the history of doping in athletes, the effects of different classes of drugs used for doping, side effects of doping, the role of anti-doping organizations, and the treatment of affected athletes.

Materials and methods

For this review, we identified studies through a MEDLINE search. Search terms included the following, individually and in combination: “doping”, “athletes”, “steroids”, “drug abuse”, “mental illness”, “drug testing”, “anti-doping”, “psychiatry”, “sports”, “depression”, “substance abuse”, “substance dependence”, “addiction”, “history”, “side effects”, “drug testing”, “treatment”, “androgens”, “testosterone”, “growth hormone”, “growth factors”, “stimulants”, “supplements”, “erythropoietin”, “alcohol”, “marijuana”, “narcotics”, “nicotine”, “Beta agonists”, “Beta blockers”, “diuretics”, “masking agents”, “gene doping”, “National Collegiate Athletic Association”, and “World Anti-Doping Agency”. We restricted results to the English language and used no date restrictions. We retrieved all papers discussing drug abuse in athletes. We reviewed the findings of each article, and reviewed the references of each paper for additional papers that had been missed in the initial search and that might include findings relevant to the scope of our review. Ultimately, 67 manuscripts or chapters were felt relevant and representative for inclusion among those referenced in this paper.

History of doping in athletes

The belief that doping is only a recent phenomenon that has arisen solely from increasing financial rewards offered to modern day elite athletes is incorrect. 16 In fact, doping is older than organized sports. Ancient Greek Olympic athletes dating back to the third century BC used various brandy and wine concoctions and ate hallucinogenic mushrooms and sesame seeds to enhance performance. Various plants were used to improve speed and endurance, while others were taken to mask pain, allowing injured athletes to continue competing. 17 – 19 Yet, even in ancient times, doping was considered unethical. In ancient Greece, for example, identified cheaters were sold into slavery. 1

The modern era of doping dates to the early 1900s, with the illegal drugging of racehorses. Its use in the Olympics was first reported in 1904. Up until the 1920s, mixtures of strychnine, heroin, cocaine, and caffeine were not uncommonly used by higher level athletes. 16

By 1930, use of PEDs in the Tour de France was an accepted practice, and when the race changed to national teams that were to be paid by the organizers, the rule book distributed to riders by the organizer reminded them that drugs were not among items with which they would be provided. 20

In the 1950s, the Soviet Olympic team began experimenting with testosterone supplementation to increase strength and power. 16 This was part of a government-sponsored program of performance enhancement by national team trainers and sports medicine doctors without knowledge of the short-term or long-term negative consequences. Additionally, when the Berlin Wall fell, the East German government’s program of giving PEDs to young elite athletes was made public. 1 Many in the sporting world had long questioned the remarkable success of the East German athletes, particularly the females, and their rapid rise to dominance in the Olympics. Young female athletes experienced more performance enhancement than did male athletes. Unfortunately, they also suffered significant and delayed side effects, including reports of early death in three athletes. 19

The specific substances used to illegally enhance performance have continued to evolve. 21 The “advances” in doping strategies have been driven, in part, by improved drug testing detection methods. 21 To avoid detection, various parties have developed ever more complicated doping techniques. 21 Further, new doping strategies may result from advances in scientific research that can lead to the discovery and use of substances that may later be banned. Over the past 150 years, no sport has had more high-profile doping allegations than cycling. 16 However, few sports have been without athletes found to be doping.

Many sports organizations have come to ban the use of PEDs and have very strict rules and consequences for people who are caught using them. The International Association of Athletics Federations was the first international governing body of sport to take the situation seriously. 22 In 1928, they banned participants from doping, 22 but with little in the way of testing available, they had to rely on the word of athletes that they were not doping. It was not until 1966 that the Federation Internationale de Football Association and Union Cycliste Internationale joined the International Association of Athletics Federations in the fight against drugs, closely followed by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) the following year. 23

The first actual drug testing of athletes occurred at the 1966 European Championships, and 2 years later the IOC implemented their first drug tests at both the Summer and Winter Olympics. 24 Anabolic steroids became even more prevalent during the 1970s, and after a method of detection was found, they were added to the IOC’s prohibited substances list in 1976. This resulted in a marked increase in the number of doping-related disqualifications in the late 1970s, 24 notably in strength-related sports, such as throwing events and weightlifting.

While the fight against stimulants and steroids was producing results, 24 the main front in the anti-doping war was rapidly shifting to blood doping. 25 This removal and subsequent reinfusion of an athlete’s blood in order to increase the level of oxygen-carrying hemoglobin has been practiced since the 1970s. 25 The IOC banned blood doping in 1986. 25 Other ways of increasing the level of hemoglobin were being tried, however. One of these was erythropoietin. 25 Erythropoietin was included in the IOC’s list of prohibited substances in 1990, but the fight against erythropoietin was long hampered by the lack of a reliable testing method. An erythropoietin detection test was first implemented at the 2000 Olympic Games. 25

In the 1970s and 1980s, there were suspicions of state-sponsored doping practices in some countries. The former German Democratic Republic substantiated these suspicions. 25 The most prominent doping case of the 1980s concerned Ben Johnson, the 100 meter dash champion who tested positive for the anabolic steroid stanozolol at the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul. 25 In the 1990s, there was a noticeable correlation between more effective test methods and a drop in top results in some sports. 25

In 1998, police found a large number of prohibited substances, including ampoules of erythropoietin, in a raid during the Tour de France. 25 , 26 The scandal led to a major reappraisal of the role of public authorities in anti-doping affairs. As early as 1963, France had been the first country to enact anti-doping legislation. Other countries followed suit, but international cooperation in anti-doping affairs was long restricted to the Council of Europe. In the 1980s, there was a marked increase in cooperation between international sports authorities and various governmental agencies. Before 1998, debate was still taking place in several discrete forums (IOC, sports federations, individual governments), resulting in differing definitions, policies, and sanctions. Athletes who had received doping sanctions were sometimes taking these sanctions, with their lawyers, to civil courts and sometimes were successful in having the sanctions overturned. The Tour de France scandal highlighted the need for an independent, nonjudicial international agency that would set unified standards for anti-doping work and coordinate the efforts of sports organizations and public authorities. The IOC took the initiative and convened the First World Conference on Doping in Sport in Lausanne in February 1999. Following the proposal of the Conference, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) was established later in 1999.

Performance-enhancing effects of substances used by athletes

There is a research base demonstrating that many doping agents are in fact performance-enhancing. However, some substances (eg, selective androgen receptor modulators, antiestrogens, and aromatase inhibitors), used in an effort to enhance performance, have little data to back up their effectiveness for such a purpose. Note that the studies cited in this paper are chosen as being historically important or representative of the bulk of the research on the topic, and the broad overview provided in this paper does not aim to cite all evidence on the effects of these substances. Additionally, research on this topic is limited by the difficulty in performing ethical studies due to the high doses of doping agents used, potential side effects, and lack of information on actual practice.

Androgens include exogenous testosterone, synthetic androgens (eg, danazol, nandrolone, stanozolol), androgen precursors (eg, androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone), selective androgen receptor modulators, and other forms of androgen stimulation. The latter categories of substances have been used by athletes in an attempt to increase endogenous testosterone in a way that may circumvent the ban enforced on natural or synthetic androgens by WADA.

Amounts of testosterone above those normally found in the human body have been shown to increase muscle strength and mass. For example, a representative randomized, double-blind study involved 43 men being randomized to four different groups: testosterone enanthate 600 mg once per week with strength training exercise; placebo with strength training exercise; testosterone enanthate 600 mg once per week with no exercise; and placebo with no exercise. This was a critical study in demonstrating that administration of testosterone increased muscle strength and fat-free mass in all recipients, and even moreso in those who exercised. 27 A second study from the same investigators 5 years later further demonstrated a dose–response relationship between testosterone and strength. 28 Another double-blind trial of exogenous testosterone involved 61 males randomized to five different doses of testosterone enanthate, ranging from 25 mg to 600 mg, along with treatment with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist to suppress endogenous testosterone secretion. That study demonstrated findings similar to the previous one, in showing a dose-dependent increase in leg power and leg press strength, which correlated with serum total testosterone concentrations. 29

Androgen precursors include androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). We found no evidence that androstenedione increases muscle strength. 30 DHEA is available as a nutritional supplement that is widely advertised in body building magazines as a substance that will improve strength. However, results from placebo-controlled studies of DHEA in males have been mixed. 30 , 31 One study involved 40 trained males being given DHEA 100 mg per day, androstenedione, or placebo, with no resulting differences in muscle mass or fat-free mass between groups. 30 A second study involved nine males and ten females randomized to receive DHEA 100 mg daily or placebo for 6 months, who were then crossed over to the other group for a further 6 months. The males but not females showed increased knee and lumbar back strength during DHEA treatment. 31

Selective androgen receptor modulators are not approved for use in humans in any country, but athletes are able to obtain these substances on the Internet. 32 No studies were found looking at the effects of selective androgen receptor modulators on muscle strength or mass in humans.

Other forms of androgen stimulation include exogenous human chorionic gonadotropin, antiestrogens such as tamoxifen, clomiphene, and raloxifene, and aromatase inhibitors such as testolactone, letrozole, and anastrozole. These substances may result in increased serum testosterone. 33 However, we found minimal research demonstrating an effect on muscle strength. 34 While androgens of different forms have been shown to improve muscle strength and mass, they have not been shown to improve whole body endurance per se. 35

Growth hormone and growth factors

Growth hormone and growth factors are also banned by WADA. Research shows recombinant human growth hormone to increase muscle mass and decrease adipose tissue. One representative study randomized male recreational athletes to growth hormone 2 mg/day subcutaneously, testosterone 250 mg weekly intramuscularly, a combination of the two treatments, or placebo. 36 Female recreational athletes were randomized to growth hormone 2 mg daily or placebo. In both males and females, growth hormone was associated with significantly decreased fat mass, increased lean body mass, and improved sprint capacity (although with no change in strength, power, or endurance). Sprint capacity improvement was even greater when growth hormone and testosterone were coadministered to males.

Growth factors include insulin-like growth factor and insulin. They are presumed to have similar effects to growth hormone, but have not been studied in athletes. 37 Athletes use these substances because of their apparent anabolic effect on muscle. 37

Stimulants include amphetamine, D-methamphetamine, methylphenidate, ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, caffeine, dimethylamylamine, cocaine, fenfluramine, pemoline, selegiline, sibutramine, strychnine, and modafinil. Research has shown stimulants to improve endurance, increase anaerobic performance, decrease feelings of fatigue, improve reaction time, increase alertness, and cause weight loss. 38 Of note, while WADA bans stimulants as a class, it does allow use of caffeine. Energy beverages now often include a variety of stimulants and other additives including not only caffeine, but also the amino acids taurine and L-carnitine, glucuronolactone, ginkgo biloba, ginseng, and others. 39 Caffeine content can be up to 500 mg per can or bottle. The potential performance benefits of the other ingredients in energy beverages are unclear. For example, taurine may improve exercise capacity by attenuating exercise-induced DNA damage, but the amounts found in popular beverages are probably far below the amounts needed to be of performance-enhancing benefit. 39

Of note, the number of athletes, especially at top levels of competition, reported to be using stimulant medications has markedly increased in recent years. In the USA, the National Collegiate Athletic Association acknowledged that the number of student athletes testing positive for stimulant medications has increased three-fold in recent years. 40 There has also been concern about inappropriate use of stimulants in major league baseball in the USA. According to a report released in January 2009, 106 players representing 8% of major league baseline players obtained therapeutic use exemptions for stimulants in 2008, which was a large increase from 28 players in 2006. 41 Therapeutic use exemptions allow athletes to take otherwise banned and performance-enhancing substances if their physician attests that they should for medical reasons.

Nutritional supplements

Nutritional supplements include vitamins, minerals, herbs, extracts, and metabolites. 39 Importantly, the purity of these substances cannot be guaranteed, such that they may contain banned substances without the athlete or manufacturer being aware. Studies have shown that many nutritional supplements purchased online and in retail stores are contaminated with banned steroids and stimulants. 42 Thus, athletes could end up failing doping tests without intentionally having ingested banned substances. 42 Creatine is not currently on the WADA banned list and is the most popular nutritional supplement for performance enhancement. 3 Studies demonstrate increased maximum power output and lean body mass from creatine. 43 , 44 As such, some allowable nutritional supplements may have ergogenic effects, but may have insufficient evidence supporting their ergogenic properties to rise to the level of being banned.

Methods to increase oxygen transport

Substances athletes use to increase oxygen transport include blood transfusions, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents such as recombinant human erythropoietin and darbepoetin alfa, hypoxia mimetics that stimulate endogenous erythropoietin production such as desferrioxamine and cobalt, and artificial oxygen carriers. Transfusions and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents have been shown to increase aerobic power and physical exercise tolerance. 45 However, the ergogenic effects of the other agents are debatable. 45

Other recreational drugs

Other recreational drugs that may be used in an attempt to enhance performance include alcohol, cannabinoids, narcotics, and nicotine. 13 WADA does not currently ban nicotine but bans cannabinoids and narcotics. Alcohol is banned in six sports during competition only. All of these substances may be used by athletes to reduce anxiety, which may be a form of performance enhancement, but we found little research looking at actual performance enhancement from these agents. Narcotics are used to decrease pain while practicing or playing. Nicotine may enhance weight loss and improve attention. 46

Beta agonists

There is debate as to whether beta-2 adrenergic agonists, for example, albuterol, formoterol, and salmeterol, are ergogenic. 47 There is anecdotal evidence of improvements in swimmers who use these substances prior to racing. 48 Additionally, oral beta agonists may increase skeletal muscle, inhibit breakdown of protein, and decrease body fat. 48 However, there is some evidence suggesting that swimmers may have a relatively high prevalence of airway hyperresponsiveness due to hours spent breathing byproducts of chlorine, such that beta agonists may be needed to restore normal, not enhanced, lung function. 49

Beta blockers

Beta blockers such as propranolol result in a decreased heart rate, reduction in hand tremor, and anxiolysis. These effects may be performance-enhancing in sports in which it is beneficial to have increased steadiness, such as archery, shooting, and billiards. 48

Other prescription drugs

Diuretics and other masking agents may be used as doping agents. 12 Diuretics can result in rapid weight loss such that they may be used for a performance advantage in sports with weight classes, such as wrestling and boxing. 12 Diuretics may also be used to hasten urinary excretion of other PEDs, thereby decreasing the chances that athletes will test positive for other banned substances that they may be using. 12 Masking agents in general conceal prohibited substances in urine or other body samples, and include diuretics, epitestosterone (to normalize urine testosterone to epitestosterone ratios), probenecid, 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, and plasma expanders (eg, glycerol, intravenous administration of albumin, dextra, and mannitol). 50

Glucocorticoids are sometimes used by athletes in an attempt to enhance performance because of their anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. 12 However, there is minimal research to show any performance benefits of this class of drugs.