Freshman requirements

- Subject requirement (A-G)

- GPA requirement

- Admission by exception

- English language proficiency

- UC graduation requirements

Additional information for

- California residents

- Out-of-state students

- Home-schooled students

Transfer requirements

- Understanding UC transfer

- Preparing to transfer

- UC transfer programs

- Transfer planning tools

International applicants

- Applying for admission

- English language proficiency (TOEFL/IELTS)

- Passports & visas

- Living accommodations

- Health care & insurance

AP & Exam credits

Applying as a freshman

- Filling out the application

- Dates & deadlines

Personal insight questions

- How applications are reviewed

- After you apply

Applying as a transfer

Types of aid

- Grants & scholarships

- Jobs & work-study

- California DREAM Loan Program

- Middle Class Scholarship Program

- Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan

- Native American Opportunity Plan

- Who can get financial aid

- How aid works

- Estimate your aid

Apply for financial aid

- Cal Dream Act application tips

- Tuition & cost of attendance

- Glossary & resources

- Santa Barbara

- Campus program & support services

- Check majors

- Freshman admit data

- Transfer admit data

- Native American Opportunity Plan

- You will have 8 questions to choose from. You must respond to only 4 of the 8 questions.

- Each response is limited to a maximum of 350 words.

- Which questions you choose to answer is entirely up to you. However, you should select questions that are most relevant to your experience and that best reflect your individual circumstances.

Keep in mind

- All questions are equal. All are given equal consideration in the application review process, which means there is no advantage or disadvantage to choosing certain questions over others.

- There is no right or wrong way to answer these questions. It’s about getting to know your personality, background, interests and achievements in your own unique voice.

- Use the additional comments field if there are issues you'd like to address that you didn't have the opportunity to discuss elsewhere on the application. This shouldn't be an essay, but rather a place to note unusual circumstances or anything that might be unclear in other parts of the application. You may use the additional comments field to note extraordinary circumstances related to COVID-19, if necessary.

Questions & guidance

Remember, the personal insight questions are just that—personal. Which means you should use our guidance for each question just as a suggestion in case you need help. The important thing is expressing who you are, what matters to you and what you want to share with UC.

1. Describe an example of your leadership experience in which you have positively influenced others, helped resolve disputes or contributed to group efforts over time. Things to consider: A leadership role can mean more than just a title. It can mean being a mentor to others, acting as the person in charge of a specific task, or taking the lead role in organizing an event or project. Think about what you accomplished and what you learned from the experience. What were your responsibilities?

Did you lead a team? How did your experience change your perspective on leading others? Did you help to resolve an important dispute at your school, church, in your community or an organization? And your leadership role doesn't necessarily have to be limited to school activities. For example, do you help out or take care of your family? 2. Every person has a creative side, and it can be expressed in many ways: problem solving, original and innovative thinking, and artistically, to name a few. Describe how you express your creative side. Things to consider: What does creativity mean to you? Do you have a creative skill that is important to you? What have you been able to do with that skill? If you used creativity to solve a problem, what was your solution? What are the steps you took to solve the problem?

How does your creativity influence your decisions inside or outside the classroom? Does your creativity relate to your major or a future career? 3. What would you say is your greatest talent or skill? How have you developed and demonstrated that talent over time? Things to consider: If there is a talent or skill that you're proud of, this is the time to share it.You don't necessarily have to be recognized or have received awards for your talent (although if you did and you want to talk about it, feel free to do so). Why is this talent or skill meaningful to you?

Does the talent come naturally or have you worked hard to develop this skill or talent? Does your talent or skill allow you opportunities in or outside the classroom? If so, what are they and how do they fit into your schedule? 4. Describe how you have taken advantage of a significant educational opportunity or worked to overcome an educational barrier you have faced. Things to consider: An educational opportunity can be anything that has added value to your educational experience and better prepared you for college. For example, participation in an honors or academic enrichment program, or enrollment in an academy that's geared toward an occupation or a major, or taking advanced courses that interest you; just to name a few.

If you choose to write about educational barriers you've faced, how did you overcome or strive to overcome them? What personal characteristics or skills did you call on to overcome this challenge? How did overcoming this barrier help shape who you are today? 5. Describe the most significant challenge you have faced and the steps you have taken to overcome this challenge. How has this challenge affected your academic achievement? Things to consider: A challenge could be personal, or something you have faced in your community or school. Why was the challenge significant to you? This is a good opportunity to talk about any obstacles you've faced and what you've learned from the experience. Did you have support from someone else or did you handle it alone?

If you're currently working your way through a challenge, what are you doing now, and does that affect different aspects of your life? For example, ask yourself, How has my life changed at home, at my school, with my friends or with my family? 6. Think about an academic subject that inspires you. Describe how you have furthered this interest inside and/or outside of the classroom. Things to consider: Many students have a passion for one specific academic subject area, something that they just can't get enough of. If that applies to you, what have you done to further that interest? Discuss how your interest in the subject developed and describe any experience you have had inside and outside the classroom such as volunteer work, internships, employment, summer programs, participation in student organizations and/or clubs and what you have gained from your involvement.

Has your interest in the subject influenced you in choosing a major and/or future career? Have you been able to pursue coursework at a higher level in this subject (honors, AP, IB, college or university work)? Are you inspired to pursue this subject further at UC, and how might you do that?

7. What have you done to make your school or your community a better place? Things to consider: Think of community as a term that can encompass a group, team or a place like your high school, hometown or home. You can define community as you see fit, just make sure you talk about your role in that community. Was there a problem that you wanted to fix in your community?

Why were you inspired to act? What did you learn from your effort? How did your actions benefit others, the wider community or both? Did you work alone or with others to initiate change in your community? 8. Beyond what has already been shared in your application, what do you believe makes you a strong candidate for admissions to the University of California? Things to consider: If there's anything you want us to know about you but didn't find a question or place in the application to tell us, now's your chance. What have you not shared with us that will highlight a skill, talent, challenge or opportunity that you think will help us know you better?

From your point of view, what do you feel makes you an excellent choice for UC? Don't be afraid to brag a little.

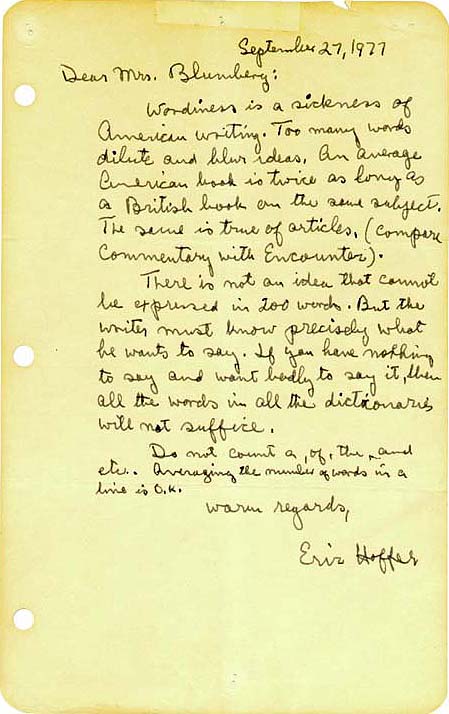

Writing tips

Start early..

Give yourself plenty of time for preparation, careful composition and revisions.

Write persuasively.

Making a list of accomplishments, activities, awards or work will lessen the impact of your words. Expand on a topic by using specific, concrete examples to support the points you want to make.

Use “I” statements.

Talk about yourself so that we can get to know your personality, talents, accomplishments and potential for success on a UC campus. Use “I” and “my” statements in your responses.

Proofread and edit.

Although you will not be evaluated on grammar, spelling or sentence structure, you should proofread your work and make sure your writing is clear. Grammatical and spelling errors can be distracting to the reader and get in the way of what you’re trying to communicate.

Solicit feedback.

Your answers should reflect your own ideas and be written by you alone, but others — family, teachers and friends can offer valuable suggestions. Ask advice of whomever you like, but do not plagiarize from sources in print or online and do not use anyone's words, published or unpublished, but your own.

Copy and paste.

Once you are satisfied with your answers, save them in plain text (ASCII) and paste them into the space provided in the application. Proofread once more to make sure no odd characters or line breaks have appeared.

This is one of many pieces of information we consider in reviewing your application. Your responses can only add value to the application. An admission decision will not be based on this section alone.

Need more help?

Download our worksheets:

- English [PDF]

- Spanish [PDF]

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the University of California Essays 2023-2024

The University of California (UC) school system is the most prestigious state university system in the United States and includes nine undergraduate universities: UC Berkeley, UC San Diego, UCLA, UC Santa Barbara, UC Santa Cruz, UC Davis, UC Riverside, UC Merced, and UC Irvine.

The University of California system has its own application portal, as well as its own deadline of November 30th—a full month before the Common Application is due. All nine universities use one application, so it is easy to apply to multiple UCs at the same time.

The application requires you to answer four of eight personal insight questions, with a 350-word limit on each prompt. This may seem daunting at first, but we provide this guide to make the prompts more approachable and to help you effectively tackle them!

University of California Application Essay Prompts

Note: There is only one application for all the UC schools, so your responses will be sent to every University of California school that you apply to. You should avoid making essays school-specific (unless you are applying to only one school).

You might want to start by deciding which four of the eight prompts you plan on answering. The eight prompts are:

1. Describe an example of your leadership experience in which you have positively influenced others, helped resolve disputes, or contributed to group efforts over time.

2. every person has a creative side, and it can be expressed in many ways: problem-solving, original and innovative thinking, and artistically, to name a few. describe how you express your creative side., 3. what would you say is your greatest talent or skill how have you developed and demonstrated that talent over time, 4. describe how you have taken advantage of a significant educational opportunity or worked to overcome an educational barrier you have faced., 5. describe the most significant challenge you have faced and the steps you have taken to overcome this challenge. how has this challenge affected your academic achievement, 6. think about an academic subject that inspires you. describe how you have furthered this interest inside and/or outside of the classroom., 7. what have you done to make your school or your community a better place, 8. beyond what has already been shared in your application, what do you believe makes you stand out as a strong candidate for admissions to the university of california.

As you begin selecting prompts, keep the purpose of college essays at the forefront of your mind. College essays are the place to humanize yourself and transform your test scores, GPA, and extracurriculars into a living, breathing human with values, ambitions, and a backstory. If a specific prompt will allow you to show a part of who you are that is not showcased in the rest of your application, start there.

If nothing immediately jumps out at you, try dividing the prompts into three categories: “definites,” “possibilities,” and “avoids at all costs.” “Definites” will be prompts that quickly spark up a specific idea in you. “Possibilities” might elicit a few loose concepts, anecdotes, or structures. And “avoids” are prompts where you honestly cannot see yourself writing a convincing essay. Next, take your “definites” and “possibilities” and jot down your initial thoughts about them. Finally, look at all of your ideas together and decide which combination would produce the most well-rounded essay profile that shows who you are as an individual.

Of course, this is just one way to approach choosing prompts if you are stuck. Some students might prefer writing out a list of their values, identifying the most important ones in their life, then figuring out how to showcase those through the prompts. Other students select prompts based on what they are excited by or through freewriting on every prompt first. Do not feel constrained by any one method. Just remember:

- Do not rush into prompts at first glance (though trial writing can be very valuable!).

- Make sure that you consider potential ideas for many prompts before making final decisions, and ultimately write about the one with the most substance.

- The prompts you select should allow you to highlight what is most important to you.

Check out our video to learn more about how to write the UC essays!

The 8 UC Personal Insight Questions

“Leadership Experience” is often a subheading on student resumes, but that is not what admissions officers are asking about here. They are asking for you to tell them a specific story of a time when your leadership truly mattered. This could include discussing the policies you enacted as president of a school club or the social ties you helped establish as captain of a sports team, but this prompt also gives you the freedom to go past that.

Leaders are individuals with strong values, who mentor, inspire, correct, and assist those around them. If you don’t feel like you’ve ever been a leader, consider the following questions:

- Have you ever mentored anyone? Is there anyone younger than you who would not be the person they are today without you?

- Have you ever taken the initiative? When and why did it matter?

- Have you ever been fundamental to positive change in the world—whether it be on the small scale of positively impacting a family member’s life or on the large scale of trying to change the status of specific communities/identities in this world?

- Have you ever stood up for what’s right or what you believe in?

Leadership is a concept that can be stretched, bent, and played with, but at the end of the day, the central theme of your essay must be leadership. Keeping this in mind, after your first draft, it can be helpful to identify the definition of leadership that you are working with, to keep your essay cohesive. This definition doesn’t need to appear within the essay (though, if you take on a more reflective structure, it might). Some examples of this include “being a positive role model as leadership,” “encouraging others to take risks as leadership,” and “embracing my identities as leadership.”

Here are some examples of how a leadership essay might look:

- You’ve always loved learning and challenging yourself, but when you got to high school it was clear that only a certain type of student was recommended to take AP classes and you didn’t fit into that type. You presented a strong case to the school counselors that you were just as prepared for AP classes as anyone else, enrolled in your desired classes, and excelled. Since then, AP classes have become more diversified at your school and there has even been a new inclusion training introduced for your district’s school counselors.

- When you were working as a camp counselor, the art teacher brought you two of your campers who were refusing to get along. To mediate the conflict, you spent long hours before bed talking to them individually, learning about their personal lives and family situation. By understanding where each camper came from, you were better equipped to help them reach a compromise and became a role model for both campers.

- As a member of your school’s Chinese organization, you were driven by your ethnic heritage to devote your lunch breaks to ensuring the smooth presentation of the Chinese culture show. You coordinated the performers, prepared refreshments, and collected tickets. You got through a great performance, even though a performer didn’t show and some of the food was delivered late. You weren’t on the leadership board or anything, but exhibited serious leadership, as both nights of the culture show sold out and hundreds of both Chinese and non-Chinese people were able to come together and celebrate your culture.

Like the last prompt, this prompt asks about a specific topic—creativity—but gives you wiggle room to expand your definition of that topic. By defining creativity as problem-solving, novel thinking, and artistic expression, this prompt basically says “get creative in how you define creativity!”

Additionally, this broad conception of creativity lets you choose if you want to write about your personal life or your academic life. A robotics student could write about their love of baking on the weekends or their quick thinking during a technical interview. A dance student could write about their love of adapting choreography from famous ballets or their innovative solution to their dance team’s lack of funds for their showcase. You have space to do what you want!

That said, because this prompt is so open, it is important to establish a focus early on. Try thinking about what is missing from your application. If you are worried that your application makes you seem hyper-academic, use this prompt to show how you have fun. If you are worried that you might be appearing like one of those students who just gets good grades because they have a good memory, use this prompt to show off your problem-solving skills.

Also, keep in mind that you don’t have to describe any skill in creative pursuits as you answer this prompt. The prompt asks you how you express your “creative side,” alluding to creative instinct, not creative talent. You could write about how you use painting to let out your emotions—but your paintings aren’t very good. You could write about dancing in the shower to get excited for your day—but one time you slipped and fell and hurt your elbow. Experiences like these could make for a great reflective essay, where you explore the human drive towards creative expression and your acceptance that you personally don’t have to be creatively inclined to let out creative energy.

Some examples:

- A math student writing about a time they devised a non-textbook method to proving theorems

- A creative writer describing how they close-read the ups-and-downs of classical music as an attempt to combat writers’ block and think of emotional trajectories for new stories

- An engineering student writing about cooking as a creative release where numbers don’t matter and intuition supersedes reason

- A psychology student writing about the limitations of quantitative data and describing a future approach to psychology that merges humanism and empiricism.

This is the kind of prompt where an answer either pops into your head or it doesn’t. The good news is that you can write a convincing essay either way. We all have great talents and skills—you just might have to dig a bit to identify the name of the talent/skill and figure out how to best describe it.

Some students have more obvious talents and skills than others. For example, if you are intending to be a college athlete, it makes sense to see your skill at your sport as your greatest talent or skill. Similarly, if you are being accepted into a highly-selective fine arts program, painting might feel like your greatest talent. These are completely reasonable to write about because, while obvious, they are also authentic!

The key to writing a convincing essay about an obvious skill is to use that skill to explore your personality, values, motivations, and ambitions. Start by considering what first drew you to your specialization. Was there a specific person? Something your life was missing that painting, hockey, or film satisfied? Were you brought up playing your sport or doing your craft because your parents wanted you to and you had to learn to love it? Or choose to love it? What was that process like? What do these experiences say about you? Next, consider how your relationship with your talent has evolved. Have you doubted your devotion at times? Have you wondered if you are good enough? Why do you keep going? On the other hand, is your talent your solace? The stable element in your life? Why do you need that?

The key is to elucidate why this activity is worth putting all your time into, and how your personality strengths are exhibited through your relationship to the activity.

Do not be put off by this prompt if you have not won any big awards or shown immense talent in something specific. All the prompt asks for is what you think is your greatest talent or skill. Some avenues of consideration for other students include:

- Think about aspects of your personality that might be considered a talent or skill. This might include being a peacemaker, being able to make people laugh during hard times, or having organization skills.

- Think about unique skills that you have developed through unique situations. These would be things like being really good at reading out loud because you spend summers with your grandfather who can no longer read, knowing traffic patterns because you volunteer as a crossing guard at the elementary school across the street that starts 45 minutes before the high school, or making really good pierogi because your babysitter as a child was Polish.

- Think about lessons you have learned through life experiences. A military baby might have a great skill for making new friends at new schools, a child of divorce might reflect on their ability to establish boundaries in what they are willing to communicate about with different people, and a student who has had to have multiple jobs in high school might be talented at multitasking and scheduling.

Make sure to also address how you have developed and demonstrated your selected talent. Do you put in small amounts of practice every day, or strenuous hours for a couple of short periods each year? Did a specific period of your life lead to the development of your talent or are you still developing it daily?

The purpose of college essays is to show your values and personality to admissions officers, which often includes exploring your past and how it informs your present and future. With a bit of creativity in how you define a “talent or skill,” this prompt can provide a great avenue for that exploration.

This prompt offers you two potential paths—discussing an educational opportunity or barrier. It is important that you limit yourself to one of these paths of exploration to keep your essay focused and cohesive.

Starting with the first option, you should think of an educational opportunity as anything that has added value to your educational experience and better prepared you for life and your career. Some examples could include:

- participation in an honors program

- enrollment in an academy geared toward your future profession

- a particularly enlightening conversation with a professional or teacher

- joining a cultural- or interest-based student coalition

- plenty of other opportunities

The phrasing “taken advantage of” implies the admissions committee’s desire for students who take the initiative. Admissions officers are more interested in students who sought out opportunities and who fought to engage with opportunities than students who were handed things. For example, a student who joined a career-advancement afterschool program in middle school could write about why they were initially interested in the program—perhaps they were struggling in a specific subject and didn’t want to fall behind because they had their sights set on getting into National Junior Honor Society, or their friend mentioned that the program facilitated internship opportunities and they thought they wanted to explore therapy as a potential career path.

On the other hand, if an opportunity was handed to you through family connections or a fortuitous introduction, explore what you did with that opportunity. For example, if a family member introduced you to an important producer because they knew you were interested in film, you could write about the notes you took during that meeting and how you have revisited the producer’s advice and used it since the meeting to find cheap equipment rentals and practice your craft.

If you choose to write about educational barriers you have faced, consider the personal characteristics and skills you called upon to overcome the challenge. How did the process of overcoming your educational barrier shape you as a person? What did you learn about yourself or the world? An added plus would be talking about passing it forward and helping those in your purview obtain the knowledge you did from your experiences.

Some examples of educational barriers could include:

- limited access to resources, materials, technology, or classes

- lacking educational role models

- struggles with deciding on a passion or career path

- financial struggles

One example of an interesting essay about educational barriers:

As a student at a school that did not offer any honors classes, you enrolled in online lectures to learn the subject you were passionate about — Human Geography. Afterward, you spoke to your school administrators about high-achieving students needing higher-level courses, and they agreed to talk to the local community college to start a pipeline for students like you.

Either way that you take this prompt, it can be used to position yourself as motivated and driven—exactly the type of student admissions officers are looking for!

This prompt is three-pronged. You must 1) identify a challenge 2) describe the steps you have taken to overcome the challenge and 3) connect the challenge to your academic achievement.

When approaching this prompt, it is best to consider these first and third aspects together so that you identify a challenge that connects to your academic life. If you simply pick any challenge you have experienced, when you get to the third part of the prompt, you may have to stretch your essay in ways that are unconvincing or feel inauthentic.

That said, remember that “academic achievement” reaches far beyond grades and exams. It can include things like:

- Deciding your career goals

- Balancing homework, jobs, and social/familial relationships

- Having enough time to devote to self-care

- Figuring out how you study/learn best

- Feeling comfortable asking for help when you need it

You should begin brainstorming challenges and hardships that you have experienced and overcome. These could include financial hardships, familial circumstances, personal illness, or learning disabilities. Challenges could also be less structural—things like feeling like you are living in a sibling’s shadow, struggles with body image, or insecurity. While it is important that your challenge was significant, it matters much more that you discuss your challenge with thoughtful reflection and maturity.

Some ways to take this prompt include:

- Writing about how overcoming a challenge taught you a skill that led to academic success — for example, a high-achieving student who struggles with anxiety was forced to take time off from school after an anxiety attack and learned the importance of giving oneself a break

- Writing about a challenge that temporarily hindered your academic success and reflecting on it — for example, a student who experienced a death in the family could have had a semester where they almost failed English because reading led to negative thought spirals instead of plot retention

- Writing about how a challenge humbled you and gave you a new perspective on your academics — for example, a student with a part-time job who helps support her family missed a shift because she was studying for a test and realized that she needed to ask her teachers for help and explain her home situation

As you describe the steps you have taken to overcome your selected challenge, you will want to include both tangible and intangible steps. This means that you will need to discuss your emotions, growth, and development, as well as what you learned through overcoming the challenge. Was your challenge easy to overcome or did it take a few tries? Do you feel you have fully overcome your challenge or is it a work in progress? If you have fully overcome the challenge, what do you do differently now? Or do you just see things differently now? If you were to experience the same challenge again, what would you have learned from before?

Here are some detailed examples:

- Your parents underwent a bitter, drawn-out divorce that deeply scarred you and your siblings, especially your little brother who was attending elementary school at the time. He was constantly distraught and melancholy and seemed to be falling further and further behind in his schoolwork. You took care of him, but at the cost of your grades plummeting. However, through this trial, you committed yourself to protecting your family at all costs. You focused on computer science in high school, hoping to major in it and save up enough money for his college tuition by the time he applies. Through this mission, your resolve strengthened and reflected in your more efficient and excellent performance in class later on.

- Your race was the most significant challenge you faced growing up. In school, teachers did not value your opinion nor did they believe in you, as evidenced by their preferential treatment of students of other races. To fight back against this discrimination, you talked to other students of the same race and established an association, pooling together resources and providing a supportive network of people to others in need of counseling regarding this issue.

The first step for approaching this prompt is fun and easy—think about an academic subject that inspires you. This part of the essay is about emotional resonance, so go with your gut and don’t overthink it. What is your favorite subject? What subject do you engage with in the media in your free time? What subject seeps into your conversations with friends and family on the weekends?

Keep in mind that high school subjects are often rather limited. The span of “academic subjects” at the university level is much less limited. Some examples of academic subjects include eighteenth-century literature, political diplomacy, astronomy, Italian film and television, botany, Jewish culture and history, mobile robotics, musical theater, race and class in urban environments, gender and sexuality, and much more.

Once you’ve decided what subject you are most interested in and inspired by, think about a tangible example of how you have furthered your interest in the subject. Some common ways students further their interests include:

- Reading about your interest

- Engaging with media (television, film, social media) about your interest

- Volunteering with organizations related to your interest

- Founding organizations related to your interest

- Reaching out to professionals with your academic interest

- Using your interest in interdisciplinary ways

- Research in your field of interest

- Internships in your field of interest

While you should include these kinds of tangible examples, do not forget to explain how your love for the subject drives the work you do, because, with an essay like this, the why can easily get lost in describing the what . Admissions officers need both.

A few examples:

- You found your US government class fascinatingly complex, so you decided to campaign for a Congressional candidate who was challenging the incumbent in your district. You canvassed in your local community, worked at the campaign headquarters, and gathered voter data whilst performing various administrative duties. Though the work was difficult, you enjoyed a sense of fulfillment that came from being part of history.

- Last year you fell in love with the play Suddenly Last Summer and decided to see what career paths were available for dramatic writing. You reached out to the contact on your local theater’s website, were invited to start attending their guest lecturer series, and introduced yourself to a lecturer one week who ended up helping you score a spot in a Young Dramatic Writers group downtown.

- The regenerative power of cells amazed you, so you decided to take AP Biology to learn more. Eventually, you mustered up the courage to email a cohort of biology professors at your local university. One professor responded, and agreed to let you assist his research for the next few months on the microorganism C. Elegans.

- You continued to develop apps and games even after AP Computer Science concluded for the year. Eventually, you became good enough to land an internship at a local startup due to your self-taught knowledge of various programming languages.

With regards to structure, you might try thinking about this essay in a past/present/future manner where you consider your past engagement with your interest and how it will affect your future at a UC school or as an adult in society. This essay could also become an anecdotal/narrative essay that centers around the story of you discovering your academic interest, or a reflective essay that dives deep into the details of why you are drawn to your particular academic subject.

Whatever way you take it, try to make your essay unique—either through your subject matter, your structure, or your writing style!

College essay prompts often engage with the word “community.” As an essay writer, it is important to recognize that your community can be as large, small, formal, or informal as you want it to be. Your school is obviously a community you belong to, but your local grocery store, the nearby pet adoption center you volunteer at, your apartment building, or an internet group can also be communities. Even larger social groups that you are a part of, like your country or your ethnicity, can be a community.

The important part of your response here is not the community you identify with but rather the way you describe your role in that community. What do you bring to your community that is special? What would be missing without you?

Some responses could include describing how you serve as a role model in your community, how you advocate for change in your community, how you are a support system for other community members, or how you correct the community when it is veering away from its values and principles.

Here are some fleshed-out examples of how this essay could take shape, using the earlier referenced communities:

- A student writes about the local grocery store in his neighborhood. Each Sunday, he picks up his family’s groceries and then goes to the pharmacy in the back to get his grandmother’s medication. The pharmacist was a close friend of his grandmother’s when she was young, so the student routinely gives the pharmacist a detailed update about his grandmother’s life. The student recognizes the value in his serving as a link to connect these two individuals who, due to aging, cannot be together physically.

- An animal-loving student volunteers one Saturday each month at the pet adoption center in their city’s downtown district. They have always been an extremely compassionate person and view the young kittens as a community that deserves to be cared for. This caring instinct also contributes to their interactions with their peers and their desire to make large-scale positive social change in the world.

Your response to this prompt will be convincing if you discuss your underlying motives for the service you have done, and in turn, demonstrate the positive influence you have made. That said, do not be afraid to talk about your actions even if they did not produce a sweeping change; as long as the effort was genuine, change is change, no matter the scale. This essay is more about values and reflection than it is about the effects of your efforts.

Lastly, if you are discussing a specific service you did for your community, you might want to touch on what you learned through your service action or initiative, and how you will continue to learn in the future. Here are a few examples:

- Passionate about classical music, you created a club that taught classical and instrumental music at local elementary schools. You knew that the kids did not have access to such resources, so you wanted to broaden their exposure as a high school senior had done for you when you were in middle school. You encouraged these elementary schoolers to fiddle with the instruments and lobbied for a music program to be implemented at the school. Whether the proposal gets approved or not, the kids have now known something they might never have known otherwise.

- Working at your local library was mundane at times, but in the long run, you realized that you were facilitating the exchange of knowledge and protecting the intellectual property of eminent scholars. Over time, you found ways to liven up the spirit of the library by leading arts and crafts time and booking puppet shows for little kids whose parents were still at work. The deep relationships you forged with the kids eventually blossomed into a bond of mentorship and mutual respect.

Be authentic and humble in your response to this essay! Make sure it feels like you made your community a better place because community is a value of yours, not just so that you could write about it in a college essay.

This is the most open-ended any question can get. You have the freedom to write about anything you want! That said, make sure that, no matter what you do with this prompt, your focus can be summarized into two sentences that describe the uniqueness of your candidacy.

The process we recommend for responding to open-ended prompts with clarity involves the following steps:

1. On a blank piece of paper, jot down any and every idea — feelings, phrases, and keywords — that pop into your head after reading this prompt. Why are you unique?

2. Narrow your ideas down to one topic. The two examples we will use are a student writing about how her habit of pausing at least five seconds before she responds to someone else’s opinion is emblematic of her thoughtfulness and a student whose interest in researching the history of colonialism in the Caribbean is emblematic of their commitment to justice.

3. Outline the structure of your essay, and plan out content for an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

4. Before you start writing your essay, write one or two sentences that summarize how you would like the admissions officers to perceive you based on this essay. These sentences will not be in your final product, but will help you to maintain a focus. For our examples, this would be something like “Natalie’s habit of gathering her thoughts before responding to other people’s opinions allows her to avoid undesired complications and miscommunications in her social interactions. This has not only helped her maintain strong relationships with all the staff members of the clubs she leads, but will also help her navigate the social environments that she will face in the professional world.” A summary for the student writing about their interest in the history of colonialism could be “Jonathan has always been highly compassionate and sympathetic by nature. When they found out about the historical injustices of colonialism in the Caribbean through the book The Black Jacobins , they realized that compassion is what is missing from politics. Now, they are inspired to pursue a political science degree to ultimately have a political career guided by compassion.”

5. Finally, write an essay dedicated to constructing the image you devised in step 4. This can be achieved through a number of different structures! For example, Natalie could use an anecdote of a time when she spoke too soon and caused someone else pain, then could reflect on how she learned the lesson to take at least five seconds before responding and how that decision has affected her life. Jonathan could create an image of the future where they are enacting local policies based on compassion. It is important to keep in mind that you do not want to be repetitive, but you must stay on topic so that admissions officers do not get distracted and forget the image that you are attempting to convey.

As exemplified by the examples we provided, a good way to approach this prompt is to think of a quality, value, or personality trait of yours that is fundamental to who you are and appealing to admissions officers, then connect it to a specific activity, habit, pet peeve, anecdote, or another tangible example that you can use to ground your essay in reality. Use the tangible to describe the abstract, and convince admissions officers that you would be a valuable asset to their UC school!

Where to Get Your UC Essays Edited

With hundreds of thousands of applicants each year, many receiving top scores and grades, getting into top UC schools is no small feat. This is why excelling in the personal-insight questions is key to presenting yourself as a worthwhile candidate. Answering these prompts can be difficult, but ultimately very rewarding, and CollegeVine is committed to helping you along that journey. Check out these UC essay examples for more writing inspiration.

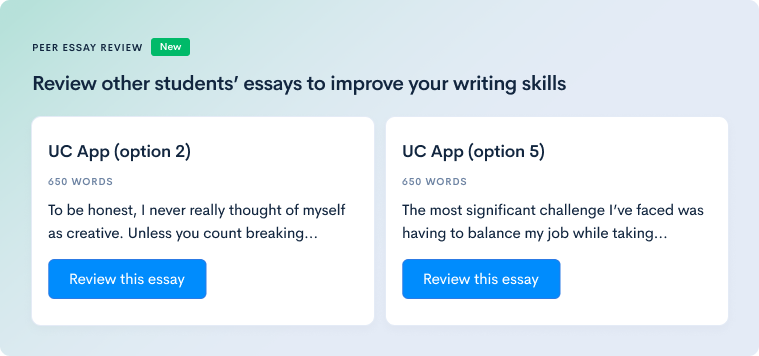

If you want to get your essays edited, we also have free peer essay review , where you can get feedback from another student. You can also improve your own writing skills by editing other students’ essays.

You can also receive expert essay review by advisors who have helped students get into their dream schools. You can book a review with an expert to receive notes on your topic, grammar, and essay structure to make your essay stand out to admissions officers. Haven’t started writing your essay yet? Advisors on CollegeVine also offer expert college counseling packages . You can purchase a package to get one-on-one guidance on any aspect of the college application process, including brainstorming and writing essays.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

- Our Culture

- Our Location

- Developing Leaders

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Sustainability

- Academic Approach

- Career Development

- Learn from Business Leaders

- Corporate Recruiters

- Dean's Speaker Series

- Dean’s Hosted Speaker Events

- Our History

- Acclaimed Alumni

- Commencement Speakers

- Dean Ann Harrison

- Haas School Board

- Full-time MBA

- Evening & Weekend MBA

- MBA for Executives

- Compare the MBA Programs

- Master of Financial Engineering

- Bachelor of Science in Business

- Berkeley M.E.T. (Management, Entrepreneurship, & Technology)

- Global Management Program

- Robinson Life Sciences Business and Entrepreneurship Program

- BASE Summer Program for Non-business Majors

- BCPA Accounting Summer Program

- Berkeley Haas Global Access Program

- Michaels Graduate Certificate in Sustainable Business

- Boost@Berkeley Haas

- Berkeley Business Academy for Youth

- Executive Education

- Research & Insights

- Media Contacts

- Faculty Experts

- Faculty Directory

- Academic Groups

- Research Institutes & Centers

- Faculty Initiatives

- Case Studies

- Research Labs

- California Management Review

- Nobel Laureates

- Teaching Awards

- Visiting Executives & Scholars

- Faculty in Public Policy

- Faculty Recruitment

- Alumni Network

- Chapters, Groups, & Networks

- Slack Alumni Workspace

- Alumni Directory

- Email (Alumni Email Services)

- Student-Alumni Connections

- Professional Resources

- For BS, MA, MFE, & PhD Alumni

- For MBA Alumni

- Lifelong Learning

- Worldwide Alumni Events Calendar

- Give to Berkeley Haas

- Impact & Recognition

- Haas Leadership Society

- How to Give

Give to Haas

Your investments drive excellence

Full-time MBA Program

Essays help us learn about who you are as a person and how you will add to our community. We seek candidates from a broad range of industries, backgrounds, cultures, and lived experiences.

Our distinctive culture is defined by four key principles - Question the Status Quo, Confidence Without Attitude, Students Always, and Beyond Yourself. We encourage you to reflect on your experiences, values, and passions so that you may craft thoughtful and authentic responses that demonstrate your alignment with our principles.

Below are the required essays, supplemental essays, and optional essays for the Fall 2023-2024 application cycle.

Required Essay #1

What makes you feel alive when you are doing it, and why? (300 words maximum)

Required Essay #2

How will an MBA help you achieve your short-term and long-term career goals? (300 words max)

Required Essay #3 - Video

Required Essay #4 - Short Answer

Optional Essays

The admissions team takes a holistic approach to application review and seeks to understand all aspects of a candidate’s character, qualifications, and experiences. We will consider achievements in the context of the opportunities available to a candidate. Some applicants may have faced hardships or unusual life circumstances, and we will consider the maturity, perseverance, and thoughtfulness with which they have responded to and/or overcome them.

Optional Information #1

We invite you to help us better understand the context of your opportunities and achievements.

Optional Information #2

Supplemental Information

- If you have not provided a letter of recommendation from your current supervisor, please explain. If not applicable, enter N/A.

- Name of organization or activity

- Nature of organization or activity

- Size of organization

- Dates of involvement

- Offices held

- Average number of hours spent per month

- List full-time and part-time jobs held during undergraduate or graduate studies indicating the employer, job title, employment dates, location, and the number of hours worked per week for each position held prior to the completion of your degree.

- If you have ever been subject to academic discipline, placed on probation, suspended, or required to withdraw from any college or university, please explain. If not, please enter N/A. (An affirmative response to this question does not automatically disqualify you from admission.)

Video: Extracurricular Supplement Tips

Senior Associate Director of Full-time Admissions, Cindy Jennings Millette, shares how we look at, and evaluate, extracurricular and community involvement.

- REQUEST INFO

- EVENTS NEAR YOU

Admissions overview

The University of California, Berkeley, is the No. 1 public university in the world. Over 40,000 students attend classes in 15 colleges and schools, offering over 300 degree programs. Set the pace with your colleagues and community, and set the bar for giving back.

Undergraduate

Find out about application deadlines, student profiles, the academic setting and what it takes to “Be Berkeley.”

Explore graduate programs, research and professional development opportunities and funding options for your graduate education.

Financial aid

Get step-by-step guidance through the application process, discover scholarships and grants, and walk through the Cal-culator to estimate your financial aid eligibility.

Itemized breakdown of costs for undergraduate, graduate and professional programs.

UC Berkeley Extension

Browse courses, online learning opportunities, certificate programs for continuing education, and personal and professional development.

Summer Sessions

Choose from over 600 courses, take a class online and find out about session dates and deadlines. International students welcome.

Study Abroad

Discover programs abroad, find out how to fund your study, review application deadlines and more.

What does it mean to Be Berkeley?

“I love Berkeley. Our students give me hope for the future.” Robert Reich, professor of public policy and former U.S. secretary of labor

18 UC Berkeley Essay Examples that Worked (2023)

If you want to get into the University of California, Berkeley in 2022, you need to write strong Personal Insight Question essays.

In this article I've gathered 18 of the best University of California essays that worked in recent years for you to learn from and get inspired.

What is UC Berkeley's Acceptance Rate?

UC Berkeley is one of the top public universities and therefore highly competitive to get admitted into.

This past year 112,854 students applied to Berkeley and only 16,412 got accepted. Which gives UC Berkeley an overall admit rate of 14.5%.

And as of 2022, the University of California no longer uses your SAT and ACT when deciding which students to admit.

UC Berkeley Acceptance Scattergram

This means that your Personal Insight Questions are even more important to stand out in the admissions process. That is, your essays are more heavily weighed.

If you're trying to get accepted to UC Berkeley, here are 18 of the best examples of Personal Insight Questions that got into Berkeley.

What are the UC Personal Insight Question Prompts for 2022-23?

The Personal Insight Questions (PIQs) are a set of eight questions asked by the UC application, of which students must answer four of those questions in 350 words or less.

Here are the Personal Insight Question prompts for this year:

- Describe an example of your leadership experience in which you have positively influenced others, helped resolve disputes or contributed to group efforts over time.

- Every person has a creative side, and it can be expressed in many ways: problem solving, original and innovative thinking, and artistically, to name a few. Describe how you express your creative side.

- What would you say is your greatest talent or skill? How have you developed and demonstrated that talent over time?

- Describe how you have taken advantage of a significant educational opportunity or worked to overcome an educational barrier you have faced.

- Describe the most significant challenge you have faced and the steps you have taken to overcome this challenge. How has this challenge affected your academic achievement?

- Think about an academic subject that inspires you. Describe how you have furthered this interest inside and/or outside of the classroom.

- What have you done to make your school or your community a better place?

- Beyond what has already been shared in your application, what do you believe makes you stand out as a strong candidate for admissions to the University of California?

18 UC Berkeley Personal Insight Question Examples

Here are the 18 best Berkeley essays that worked for each Personal Insight Question prompt #1-8.

If you're also applying to UCLA, check out more unique UCLA essays from admitted students.

UC Berkeley Example Essay #1

Uc berkeley example essay #2, uc berkeley example essay #3: clammy hands, uc berkeley example essay #4: memory, uc berkeley example essay #5: chemistry class, uc berkeley example essay #6, uc berkeley example essay #7: debate, uc berkeley example essay #8, uc berkeley example essay #9, uc berkeley example essay #10, uc berkeley example essay #11, uc berkeley example essay #12, uc berkeley example essay #13, uc berkeley example essay #14, uc berkeley example essay #15, uc berkeley example essay #16, uc berkeley example essay #17, uc berkeley example essay #18.

UC PIQ #1: Describe an example of your leadership experience in which you have positively influenced others, helped resolve disputes or contributed to group efforts over time. (350 words max)

From an early age I became a translator for my mother anytime we went out in public. This experience forced me to have conversations with adults from a young age. It made me become a great communicator, while helping my parents overcome their language barrier.

Being a communicator has allowed me to lead. When I joined my school’s National Honor Society I was given the opportunity to lead. Applying the skills I used from being my mother’s translator I was able to do what no one else could, make the calls and start the club’s most successful event to date an annual Food Drive at a local Albertson’s, which collects over one ton of food every November. Also developing events like an egg hunt at the local elementary school, a goods drive for the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, and stabilizing a volunteer partnership with a local park. I have been able to grow as a leader, who actively communicates and brings parties together, planning events and having them run smoothly with minor issues. For instance, last year there was an issue with the homeless shelter not picking up the food for the food drive. In a spur of the moment solution I managed for club member’s parents to collectively deliver the food. My ability to communicate benefited me allowing me to find a solution to an unanticipated problem.

Throughout the four years I have been in journalism I have led; mentoring younger writers and improving the way the paper operates. Staying after hours, skyping with writers about their articles all helped establish my role as a leader, who is always supporting his team. I have done this while writing over 100 articles, editing tons of pages, and managing deadlines. I learned that while being a leader requires effort, it is the passion like I have for journalism that motivates me to lead in my community.

Being a leader so far in my life has taught me that I need to communicate, be passionate, and pass on my knowledge helping cultivate future leaders, who can expand and supersede my work.

UC PIQ #2: Every person has a creative side, and it can be expressed in many ways: problem solving, original and innovative thinking, and artistically, to name a few. Describe how you express your creative side. (350 words max)

Video games have cultivated my creative thought process. When I was a toddler I invented a game I would play with my brothers. It was nothing along the lines of Hide-and-Seek or Tag, but rather, it was meant to mimic a role-playing video game. It was called "Guy" and came with its own story, leveling system, and narrative story. While seemingly impossible to translate the mechanics of a video game into real life, the "Guy" trilogy provided hundreds of hours of fun to pass hot summer days and escape the harsh reality of our parents arguing and eventual divorce.

This thought process translated into my educational career. have always thought of a tough class or test as a video game. This mostly due to my excessive amounts of video games I played as a child through middle school (especially 7th grade). Each year comes bigger and "stronger" challenges, bigger and stronger bosses to defeat. My senior year will have me face the most powerful boss yet; full AP course load on top of heavy club involvement and community college classes.

Many thought of this "secret boss" as an impossible challenge; something that could never be beaten. No one from my school has ever attempted to take on such a challenge, let alone defeat it. That is probably what excites me about it. In a game, messing around with lower level enemies is fun for a while, but gets boring when it is too easy. The thought of a challenge so great and difficult makes the victory even more rewarding. Stormy skies, heavy rain, and epic boss battle music; I'll take that over a peaceful village any day. In the future, I seek to use this thinking to drive research. I think of abstract physics concepts like secret door and levels that need to be proven true or just a myth in the game. One day, I can make my own discovery of a secret "cheat code' that can help everyone who plays a little game called life.

UC PIQ #3: What would you say is your greatest talent or skill? How have you developed and demonstrated that talent over time? (350 words max)

I’ve always hated the feeling of clammy hands, the needless overflow of adrenaline rushing through my veins, and the piercing eyes that can see through my façade—the eyes that judge me. I felt like this debilitating anxiety that I suffered through was something I could not avoid when doing the thing I was most afraid of—public speaking. I still felt every sweat droplet run down my skin before each speech, and this anguish never completely dissipated. Fortunately, I learned to moderate my fear in high school when I decided to join the speech and debate program. My anxiety has slowly faded in intensity as I’ve gained certitude and poise with every tournament, and every chance I’m given to speak on behalf of others; this talent has allowed me to be a voice for the voiceless.

Out of all the national tournaments that I’ve competed in, the MLK invitational holds a distinct place in my heart. It was my first invitational tournament in which I competed exclusively in Lincoln Douglas debate. I only had two weeks to prepare myself since it was finals week, while my competitors had upwards of two months to prepare. I was fortunate to break into the final round, as my years of experience helped me to articulate and explain my few arguments more effectively, while also refuting my opponent’s.

I realized that the extent of one’s knowledge is useless if it cannot be made known in a way that is clear to others. I learned that preparation is necessary, but one can be so focused on what they are going to say that they don’t hear the arguments presented. I kept an open and ready mind for various claims and strategies which left me free to adapt to the opponent’s argumentative style each round. This ability to think on my feet has served me well in countless debates, speeches, and presentations. I continuously use these skills to become a better and more active listener in my daily interactions as well.

Learn the secrets of successful top-20 college essays

Join 4,000+ students and parents that already receive our 5-minute free newsletter , packed with top-20 essay examples, writing tips & tricks, and step-by-step guides.

My greatest skill is my ability to remember things really well, whether they be minute details or important information that should not be forgotten. Over time, I’ve had a knack for remembering details most people would not even bother to remember, such as old test scores, atomic masses, and other details involving numbers. My friends have always marveled at my ability to remember all these numbers. When I was in chemistry class, we used the periodic table so much that I soon began to remember the atomic mass of the more common elements, and even the molecular mass of common compounds like glucose or water. One of my best friends, who is undoubtedly the smartest person in our class, even finds it crazy that I can remember all these numbers and always tells me that my memory of numbers is amazing. I also used my memory to learn and remember how to solve the Rubik's cube, which amazes my friends, as they find it to be complex with many different, possible combinations.

This skill that I have developed, however, isn’t completely under my control, as sometimes I just remember random and irrelevant facts without really trying to do so. I recall one weekend when my eight-year-old cousin was attempting to memorize the digits of pi: I remembered them along with him, learning up to forty digits in just one day. The skill is seemingly natural and not something I have worked hard to develop, as I may be able to use my memory to my advantage, or it can be a disadvantage. It helps when I have multiple tests in one day, or a test with many questions where I have to remember a lot of information, such as finals. Sometimes, however, it is a disadvantage when I remember information during a test that is not relevant to the topic, such as random dates, names, or song lyrics, to name a few. This skill is very important to nonetheless, as it has assisted me all throughout my life in many tests and challenges involving memory.

UC PIQ #4: Describe how you have taken advantage of a significant educational opportunity or worked to overcome an educational barrier you have faced. (350 words max)

At 10:30 pm on a hot, summer, Wednesday night, you would expect my friends and me to be having the time of our lives and going out on crazy high school adventures— but instead, we were actually stuck in a chemistry laboratory trying to map out the Lewis structure of sulfuric acid.

Over the summer of my sophomore year, my friends and I enrolled into ‘Introduction to Chemistry’, an evening course at our local community college. As a six-week summer course, I spent two hours in lecture, two hours in the laboratory, and another two hours studying on my own for four days a week for six weeks. It was evident that I struggled with adjusting to the pace of college when I received 19% on a quiz. I felt left behind, exhausted, and overall pathetic. No matter how many hours I spent studying, I couldn’t keep up. But instead of giving up, I picked up certain strategies like reading the material the night before, rewriting my notes, and joining a study group; eventually working my way up to a B.

At the end of that summer, I learned so much more than just chemistry. On top of having the raw experience of what college is like, my chemistry experience taught me that it is okay to fail. I discovered that failure is an essential part of learning. Coming to this realization inspired me to take more college courses and rigorous courses in high school. I transformed into a hungry learner, eager to fail, learn, and improve. By seizing the opportunity to take this course, I pushed myself beyond my limits. This experience and realization changed how I wanted to pursue the rest of high school, college, and life in general.

I walked into my first day of the chemistry class expecting to walk out with an A; but thankfully, I didn’t. Instead, I walked out of that class with a taste of the college experience and a principle that I now live by-- that it is okay to fail, as long as you get back up.

The relationship I cultivated with my school's college center, by simply being inquisitive, has been most significant. Over my years in high school the college center became my 2nd home, where I learned about extra opportunities and triumphed with help from counselors.

For instance, with help from my school’s college center I applied and was accepted as an LAUSD Superintendent Summer Scholar this past summer. The program selected 15 juniors out of over 450 applicants to work in one of 15 departments, and I was chosen to work for the communications department, which received over 70 applications – making me 1 of 70. Interning for LAUSD at their 29 floor high rise was very eye-opening and exposed me to working in communications alongside seasoned professionals. The opportunity gave me the chance to meet the Superintendent and school board members, who are politically in charge of my education. As part of the communications department I learned how the district operates a network of over 1,300 schools and saw how the 2nd largest school district shares info with stakeholders through universal press releases, phone calls, and the district homepage.

I wrote several articles for the district publication and worked with public information officers who taught me the principles of professionalism and how to communicate to over 1 million people. Recently, I was called from the district to become a part of their Media Advisory Council working alongside district heads, representing the students of LAUSD.

Working for LAUSD furthered my passion to pursue careers in both communication and education. I have always had a desire to be a journalist and the internship assured me of that. I want to write stories bringing student issues from areas like mine to light. Being exposed to the movers and shakers that control education in Los Angeles has heavily motivated me to become an educator and at some point become a school board member influencing the education students like me receive.

Support from the college center has spawned opportunities like a life-changing internship and set me on course for a future full of opportunity.

“Give me liberty, or give me death!”, I proudly exclaimed, finishing up a speech during my first Individual Event competition for Speech and Debate, also known as Forensics Workshop. Public speaking was always one of my shortcomings. During countless in-class presentations, I suffered from stage-fright and anxiety, and my voice always turned nervous and silent. I saw Speech and Debate as a solution to this barrier that hindered my ability to teach and learn. With excessive practice, I passed the tryout and found myself in the zero-period class. All of my teammates, however, joined because they loved chattering and arguing. I had the opposite reason: I despised public speaking.

I was definitely one of the least competitive members of the team, probably because I didn’t take the tournaments very seriously and mainly worried about being a better speaker for the future. Throughout the daily class, I engaged in impromptu competitions, speech interpretations, spontaneous arguments, etc... Throughout my two years on the team, my communication, reciting, writing, and arguing skills overall improved through participation in events such as Impromptu, Original Oratory, Oratorical Interpretation, Lincoln Douglas Debate, and Congress. I even achieved a Certificate of Excellence in my first competition for Oratorical Interpretation -- where we had to recite a historical or current speech -- for Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty, or Give Me Death.”

I decided to quit Speech and Debate because I felt as if it has completed its purpose. After this educational experience, my communications skilled soared, so I could perform better in school, especially on essays and presentations. Leaving this activity after two years gave me more time to focus on other activities, and apply communications skills to them. In fact, I even did better in interviews (which is how I got into the Torrance Youth Development Program) and even obtained leadership positions in clubs such as Math Club and Science Olympiad Through my two years in Speech and Debate, I believe I became a much better thinker, speaker, and leader. Taking advantage of this opportunity boosted my self-esteem and overall made high school a better experience.

UC PIQ #5: Describe the most significant challenge you have faced and the steps you have taken to overcome this challenge. How has this challenge affected your academic achievement? (350 words max)

Although many would say that hardships are the greatest hindrance on a person, my hardships are my greatest assets. The hardships I have overcome are what push and drive me forward. If I had not gone through the failures of my 7th grade year I may have been satisfied as a B or C student. It is easy for us to use our hardships as excuses for not doing work, however, this is a mistake that many people make.

Through my struggles and failure, I have realized an important truth: I am not special. The world will continue to go on and expect me to contribute no matter what I have gone through. Everyone endures some type of obstacle in their life; what makes people different is how they handle them. Some sit around and cry "boo-hoo" waiting for people to feel sorry for them. Others actually take action to improve their situation.

Through hard work, I have been able to outperform my peers, yet I know there is still room for improvement. The thought of actual geniuses in top universities excited me; I long to learn from them and eventually surpass them, or perhaps enter a never ending race for knowledge with them. I used to live an hour away from school. I would have to wake up and be dropped off at a donut shop at 4 in the morning and then walk to school at 6:30 am. After school, I would have to walk to the public library and stay for as long as it was open then wait outside and get picked up around 9:30 pm. I am reluctant to retell this story; not because I am ashamed, but because it is not important. It doesn't matter what hardships I have endured, they do not determine who I am. What matters is what I have done.

At the start of high school, I saw nothing but success. From grades to extracurricular activities, everything seemed to be going smoothly. However, as my sophomore year progressed, this wave of success was soon swamped by a wave of disillusionment. I struggled to perform in Calculus and as a Vice-President, but instead of looking for a solution, I looked for excuses. Ultimately, when I was forced to face my two F’s and my lost elections, the world came crashing down. The vision I had meticulously planned out for the future seemed to shatter before my eyes. My self-confidence plummeted to an all-time low. I thought my life was over.

However, my response to this failure was what would ultimately determine the direction my life would take. In the end, I made the right choice: instead of continuing to blind myself with a false narrative that cast all the blame off my own shoulders, I admitted to my own shortcomings and used this experience as a lesson to grow from.

In doing so, I learned to focus on the aspects of my life that I was truly passionate about instead of spreading myself too thin. I learned to face challenges head-on instead cowering at the first sign of difficulty, even if it meant asking others for help. I learned to accept and utilize my own differences to create my own unique leadership style. Most importantly, rather than letting this mistake define me, I ignited a sense of determination that would guide me back on the right path no matter how many obstacles I encounter.

Looking back, this tragic mistake was a double-edged sword. While it definitely leaves a stain on my record, it is also likely that I wouldn’t have been able to find the same success a year later without the lessons I gained from this experience. At the end of the day, while I still grimace every time I contemplate my sophomore year, I understand now that this mistake is what has allowed me to develop into the person I am today.

Throughout my childhood, I grew up in a nine-person household where the channels of our TV never left the Filipino drama station and the air always smelled of Filipino food. But the moment I left home, I would go to a typical suburban elementary school as an average American kid at the playground. I grew up in a unique position which I both love and hate: being a second-generation Filipino American.

I love being a second-generation immigrant. I have the best of both worlds. But I also hate it. It chains me to this ongoing struggle of living under the high expectations of immigrant parents. How could I hate the part of me that I loved the most?

Growing up, I lived under the constant academic stress that my parents placed on me. Their expectations were through the roof, demanding that I only bring home A’s on my report card. My entire academic career was based on my parent’s expectations. Their eyes beat down on every test score I received. I loved them so much, but I could only handle so much. The stress ate me alive, but I silently continued to work hard.

Living under this stress is the biggest ongoing challenge of my life thus far. Until last year, I never understood why my parents expected so much from me. Finally being old enough to understand my parent’s point of view, I realize that they set these high expectations in the hopes that one day, all of the pain and struggles it took to get to America will pay off. Since then, I’ve overcome the high expectations of my parents by converting their pressure into a fireball of ambition and motivation, deeply ingrained in my mentality.

This intense desire to succeed in America as a second-generation immigrant is something that has and always will fuel my academic drive. As the first person in my family to go to college in America, I’ve made it my life aspiration to succeed in academics in the honor of my family-- a decision made by me.

UC PIQ #6: Think about an academic subject that inspires you. Describe how you have furthered this interest inside and/or outside of the classroom. (350 words max)

Understanding the past helps us make better choices in today’s society. History provides us with the views of people and politics, the ethnic origin of people, and much more. At the base of all history, there is an intensive culmination of research which hopes to address or bring light to a story.

My passion for history began while digging deep into own family’s story, researching the history of Latin America, and the origins of the city I was raised in.

For example, when I first saw my favorite show Avatar The Last Airbender, I spent hours researching the mythology of the show which in the process made me learn about the philosophy of China: daoism, Confucius, and the mandate of heaven. Anything can be put within a historical framework to understand the context; every decision, tv show, and law has a history and that is exactly what I love. History forces us to take into account the voices of the past before we can attempt to plan for the future.

History has helped me become a more effective writer for the school paper. It has made me think like a attorney, revisiting old cases, and writing up a winning argument in a mock trial. Thinking like a historian has helped me make sense of the current political climate and motivated me to help start Students For Liberty, at my school’s campus where political ideologies are shared respectfully.

Learning, about history drives my inquisitive nature — I demonstrated this desire by volunteering at a local museum to learn more about the origins of my community in Carson. Ultimately, learning about the Dominguez family who established the Harbor Area of LA.

In terms of academics and performance, I have passed both of my history AP exams in World and U.S. history — being the 2nd person in my school’s history to do so. Studying history in highschool has nurtured my love for social science, which I hope to continue in college and throughout my life.

Ever since I was little, I have possessed a unique fascination for nature and the way it interacts with itself. As I sat in the prickly seats of old tour buses and the bilingual tour guide has silenced himself for the dozens of passengers that have closed their curtains and fallen into deep slumber, I would keep my eyes glued to the window, waiting to catch a glimpse of wild animals and admiring the beautiful scenery that mother nature had pieced together. At Outdoor Science Camp, while most of my friends were fixated on socializing and games, I was obsessed with finding every organism in the book. Nothing else caught my attention quite like ecology.

As high school dragged on and the relentless responsibilities, assignments, and tests washed away the thrill of learning, ecology was one interest that withstood the turmoil. At the end of a draining day, I would always enjoy relaxing to articles detailing newly discovered species or relationships between species.

This past summer, I was able to further this interest when a unique opportunity to volunteer abroad caught my eye. Flying over to the beautiful tropical shorelines of the Dominican Republic, I was able to dive into the frontlines of the battle against climate change, dwindling populations, and habitat destruction brought about by mankind, and I enjoyed every moment of it.

While everyone was obviously ecstatic about snorkeling in the crystal blue waters, only I was able to retain that same excitement about trekking through knee thick mud and mosquito infested forests to replant mangrove trees. While tracking animal populations, my heart leaped at the sight of every new species that swam right in front of my eyes. Even when it came to the dirty work of building structures to rebuild coral and picking up trash along the beach, I always found myself leading the pack, eager to start and do the most.

From this experience, I realized that pursuing the field of ecology was what I could picture myself doing far into the future, and this was how I was going to impact the world.

UC PIQ #7: What have you done to make your school or your community a better place? (350 words max)