- Try for free

Think-Alouds

Effective teachers think out loud on a regular basis

Download for free, what are think-alouds.

Think-alouds are a strategy in which students verbalize their thoughts while reading or answering questions. By saying what they're thinking, students can externalize and process their thoughts.

Effective teachers think out loud regularly to model this process for students. In this way, they demonstrate practical ways of approaching difficult problems while bringing to the surface the complex thinking processes that underlie reading comprehension, problem solving, and other cognitively demanding tasks.

Why Use Think-Alouds?

Key takeaways:

- The think-aloud strategy is used to model comprehension processes such as making predictions, creating images, and linking information to prior knowledge.

- Teachers model expert problem-solving by verbalizing their thought processes, aiding students in developing their own problem-solving skills, and fostering independent learning.

- Teachers can assess students' strengths and weaknesses by listening to their verbalized thoughts.

- Getting students into the habit of thinking out loud enriches classroom discourse and gives teachers an important assessment and diagnostic tool.

- Research has demonstrated that the think-aloud strategy is effective for fostering comprehension skills from an early age.

Summary of the research

Think-alouds, where teachers vocalize their problem-solving process, serve as a model for students to develop their inner dialogue, a critical tool in problem-solving (Tinzmann et al. 1990). This interactive approach fosters reflective, metacognitive, independent learning. It helps students understand that learning requires effort and often involves difficulty, assuring them they are not alone in navigating problem-solving processes (Tinzmann et al. 1990).

Think-alouds are used to model comprehension processes such as making predictions, creating images, linking information in text with prior knowledge , monitoring comprehension, and overcoming problems with word recognition or comprehension (Gunning 1996).

By listening in as students think aloud, teachers can diagnose students' strengths and weaknesses. "When teachers use assessment techniques such as observations, conversations and interviews with students, or interactive journals, students are likely to learn through the process of articulating their ideas and answering the teacher's questions" (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics 2000).

Research into the impact of using the think-aloud strategy to enhance reading comprehension of science concepts found that implementing think-alouds as a during-reading activity significantly improved the comprehension of science concepts in Kindergarten students (Ortleib & Norris, 2012). This finding underscores the effectiveness of the think-aloud strategy in fostering comprehension skills from an early age.

How To Use Think-Alouds

Think-alouds are versatile teaching tools that can be applied in various ways. For instance, in math, teachers can model the strategy by vocalizing their problem-solving process as they work through a problem. In reading, the think-aloud strategy enhances comprehension by allowing students to actively engage with the text, verbalizing their thought processes, questions, and connections.

Another approach is the use of reciprocal think-alouds, which fosters collaboration and helps students understand different ways of thinking. Think-alouds can also be used as an assessment tool to pinpoint individual student needs, shaping instruction to better suit each learner.

Think-alouds can be used in a number of ways across different subject areas, including:

- Reading/English: The think-aloud process can be used during all stages of reading, from accessing prior knowledge and making predictions to understanding text structure and supporting opinions.

- Writing: Think-alouds can be used to model the writing process, including pre-writing strategies, drafting, revision, and editing.

- Math: Use think-alouds to model the use of new math processes or strategies, and assess student understanding.

- Social Studies: During discussions on complex topics, have students use think-alouds to explain their reasoning and opinions.

- Science: Think-alouds can be used to model the scientific inquiry process, and students can reflect on this process in their journals or learning logs.

Modeling Thinking-Alouds

Modeling think-alouds is a method where a teacher vocalizes their problem-solving process, serving as a guide for students. This strategy allows learners to see the internal mechanisms of problem-solving, demonstrating that learning is an active process. It helps students develop their metacognitive skills, promoting independent learning.

What does this look like in the classroom?

Before proceeding with the actual think-aloud, first, explain the concept and its significance. For instance, "Today, we're going to use the think-aloud strategy as we work through this problem. The think-aloud strategy helps us to vocalize our inner thoughts and reasoning as we solve a problem. It's a useful tool because it allows us to better understand our own thought processes and identify areas where we might be struggling."

Modeling the Think-Aloud Strategy for Math

The think-aloud strategy is instrumental in developing problem-solving skills as it promotes metacognition, enabling students to understand and evaluate their thought processes while tackling a problem.

For example, suppose during math class you'd like students to estimate the number of pencils in a school. Introduce the strategy by saying, "The strategy I am going to use today is estimation. We use it to . . . It is useful because . . . When we estimate, we . . ."

Next say, "I am going to think aloud as I estimate the number of pencils in our school. I want you to listen and jot down my ideas and actions." Then, think aloud as you perform the task.

Your think-aloud might go something like this:

"Hmmmmmm. So, let me start by estimating the number of students in the building. Let's see. There are 5 grades; first grade, second grade, third grade, fourth grade, fifth grade, plus kindergarten. So, that makes 6 grades because 5 plus 1 equals 6. And there are 2 classes at each grade level, right? So, that makes 12 classes in all because 6 times 2 is 12. Okay, now I have to figure out how many students in all. Well, how many in this class? [Counts.] Fifteen, right? Okay, I'm going to assume that 15 is average. So, if there are 12 classes with 15 students in each class, that makes, let's see, if it were 10 classes it would be 150 because 10 times 15 is 150. Then 2 more classes would be 2 times 15, and 2 times 15 is 30, so I add 30 to 150 and get 180. So, there are about 180 students in the school. I also have to add 12 to 180 because the school has 12 teachers, and teachers use pencils, too. So that is 192 people with pencils."

Continue in this way.

Modeling the Think-Aloud Strategy for Reading

The think-aloud strategy enhances reading comprehension by promoting metacognitive understanding of the reading process. It allows students to actively engage with the text, verbalizing their thought processes, questions, and connections, which leads to deeper understanding and retention of material.

When reading aloud, you can stop from time to time and orally complete sentences like these:

- So far, I've learned...

- This made me think of...

- That didn't make sense.

- I think ___ will happen next.

- I reread that part because...

- I was confused by...

- I think the most important part was...

- That is interesting because...

- I wonder why...

- I just thought of...

More Ways to Model Think-Alouds

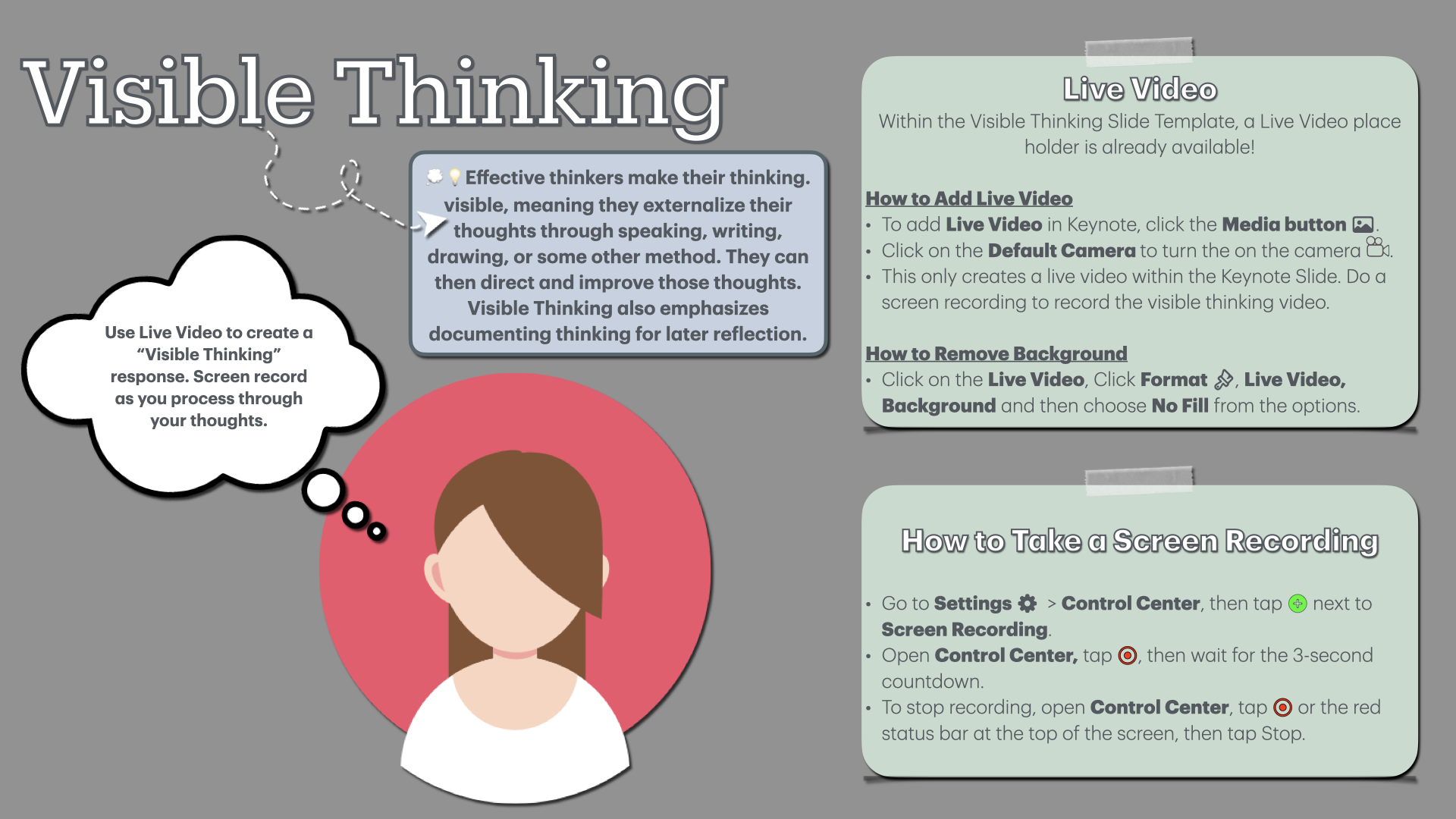

Another option is to video the part of a lesson that models thinking aloud. Students can watch the video and figure out what the teacher did and why. Stop the video periodically to discuss what they notice, what strategies were tried, and why, and whether they worked. As students discuss the process, jot down any important observations.

Once students are familiar with the strategy, include them in a think-aloud process. For example:

Teacher: "For science class, we need to figure out how much snow is going to fall this year. How can we do that?"

Student: "We could estimate."

Teacher: "That sounds like it might work. How do we start? What do we do next? How do we know if our estimate is close? How do we check it?"

In schools where teachers work collaboratively in grade-level teams or learning communities, teachers can plan and rehearse using the think-aloud strategy with a partner before introducing it to students. It is often more effective when the whole school focuses on the same strategy and approaches to integrate it into learning.

Reciprocal Think-Alouds

In reciprocal think-alouds, students are paired with a partner. Students take turns thinking aloud as they read a difficult text, form a hypothesis in science , or compare opposing points of view in social studies . While the first student thinks aloud, the second student listens and records what the first student says. Then students change roles so each partner can think aloud and observe the process. Next, students reflect on the process together, sharing what they tried and discussing what worked well for them and what didn't. As they write about their findings, they can start a mutual learning log that they refer back to.

Think-Alouds as an Assessment Tool

After students are comfortable with the think-aloud process you can use it as an assessment tool. As students think out loud through a problem-solving process, such as reflecting on the steps used to solve a problem in math, write what they say. This allows you to observe the strategies students use. Analyzing the results will allow to pinpoint the individual student's needs and provide appropriate instruction.

Assign a task, such as solving a specific problem or reading a passage of text. Introduce the task to students by saying, "I want you to think aloud as you complete the task: say everything that is going on in your mind." As students complete the task, listen carefully and write down what students say. It may be helpful to use a tape recorder. If students forget to think aloud, ask open-ended questions: "What are you thinking now?" and "Why do you think that?"

After the think-alouds, informally interview students to clarify any confusion that might have arisen during the think-aloud. For example, "When you were thinking aloud, you said . . . Can you explain what you meant?"

Lastly, use a rubric as an aid to analyze each student's think-aloud, and use the results to shape instruction.

For state-mandated tests, determine if students need to think aloud during the actual testing situation. When people are asked to solve difficult problems or to perform difficult tasks, inner speech goes external (Tinzmann et al. 1990). When faced with a problem-solving situation, some students need to think aloud. For these students, if the state testing protocol permits it, arrange for testing situations that allow students to use think-alouds. This will give a more complete picture of what these students can do as independent learners.

See the research that supports this strategy

Tinzmann, M B. et. al. (1996) What Is the Collaborative Classroom? Journal: NCREL. Oak Brook.

Gunning, Thomas G. (1996). Creating Reading Instruction for All Children. Chapter 6, 192-236.

The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2000). Principles and Standards for School Mathematics. Reston, VA: The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Inc .

Wilhelm, J. D. (2001). Improving Comprehension with Think-Aloud Strategies. New York: Scholastic Inc.

Ortlieb, E., & Norris, M. (2012). Using the Think-Aloud Strategy to Bolster Reading Comprehension of Science Concepts. Current Issues in Education , 15 (1)

Featured High School Resources

Related Resources

About the author

TeacherVision Editorial Staff

The TeacherVision editorial team is comprised of teachers, experts, and content professionals dedicated to bringing you the most accurate and relevant information in the teaching space.

Modelling through think alouds

The think aloud strategy involves the articulation of thinking, and has been identified as an effective instructional tool.

Think aloud protocols involve the teacher vocalising the internal thinking that they employ when engaged in literacy practices or other areas of learning. The intention is that think alouds make transparent or overt the cognitive processes that literate people deploy. The effective use of think alouds can positively influence student achievement (Fisher, Frey and Lapp, 2011; Ness, 2016).

It is common for teachers to use think alouds when modelling writing, reading, working out mathematical calculations and for speaking and listening strategies. For maximum impact, it is recommended that think alouds are considered in the planning phase (Ness, 2016).

Students can also use think alouds to monitor their comprehension, which can act as a form of assessment. Student think alouds can benefit the speaker, as links between oral language, reading and writing are made, while acting as a model for other students.

Read more information on think alouds and see an in practice lesson containing think alouds .

Fisher, D., Frey, N., and Lapp, D. (2011). Coaching middle-level teachers to think aloud improves comprehension instruction and student reading achievement. Teacher Educator, 46(3), 231-243.

Ness, M. (2016). Learning from K – 5 teachers who think aloud. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. 30, (3), 282 – 292.

Our website uses a free tool to translate into other languages. This tool is a guide and may not be accurate. For more, see: Information in your language

- Our Mission

The Think-Aloud Strategy: An Oldie But Goodie

Sometimes you need to be really far away to get perspective and be reminded of what you already know. As I write this, the eight thousand miles between myself and the schools I work in are illuminating the inside out, backward, and upside down nature of our education system. I'm am talking about the spliced into 55-minute periods, standardized testing, and the disconnection from authentic application and what makes life meaningful. I know, not all schools in the US are like this, but too many are.

I'm in Bali and for the last two weeks have been observing how Balinese children learn music, dance, and other arts. I've never been to a place where the arts were more integrated into daily life. In Ubud, the "cultural center of Bali," it's hard to walk down a street or spend a day without hearing or seeing some kind of artistic expression.

Much of this is connected to religious practices and takes place at the many temples on the island. This I expected. What surprises me is how children throw themselves onto every stage, into the laps of musicians, into the workshops of the carvers and painters and weavers. But perhaps "throws" is the wrong word -- I start to notice that they are pulled onto stages and laps and workshops.

Real-World Application

Early in our trip we wanted to learn something about Balinese gamelan and signed up for a day-long course. Our instructors spoke very little English. They taught by demonstrating, and motioning to us to copy them, and then by holding our hands and moving the hammer-like gavels over the xylophone. We didn't need much language and without it, I paid closer attention to the rhythms, the beats, and the sequences of notes.

Throughout our class other Balinese played along, helping to create the beautiful sounds of a Gamelan ensemble. Amongst these players was a boy of three or four who wandered up and plunked himself down first at an instrument that was full of symbols and then at a small, gong. He played, and then danced, and then pulled out a flute, played that, and then sat next to my son and tried to teach him percussive rhythms.

I wondered whose child he was as he moved from lap to lap, each Balinese adult laughing with him, encouraging him, clapping for him after he danced, and giving him instruction on his music as well.

I was captivated watching this little boy and my own son who was learning by doing -- and for a purpose and authentic application. I want this kind of learning to be a daily reality for the students in the schools where I work.

In the Classroom

Let me take a big leap now into what this reflection might mean for those who are still working within the 55-minute period. While this is far from what I envision schools to be, I know we can start taking steps towards integrating this concept, starting with a strategy as simple as the "think-aloud."

When I first started teaching English Language Arts to middle school students, a wise mentor encouraged me to share my writing practice with my students. "ELA teachers must be readers and writers themselves," she said, "so that they can make their process transparent to their students." She explained how to use the strategy think-aloud as students wrote first drafts.

I began to do them regularly in class as a way to determine a focus for my writing, how I revised it, and how I organized my thoughts. I did the same for reading, narrating the metacognitive processes I used to make sense of texts. I was surprised by how captivated my students were with these mini-lessons; those of us who teach middle-schoolers know that it's hard to captivate this audience! Then I saw the evidence show up in their writing; when we had a conference about a piece they were working on, they'd narrate their thoughts and use phrases I'd used, such as, "here, I want my audience to feel... ."

Why It Works

Now I recognize this strategy as one that parallels what I have been seeing in Bali. It's the old apprentice model, of course, but it can be adapted to our educational context today. This strategy can be applied to any content. It's about making our thinking transparent for kids, the steps we take to figure something out, and the ways in which our actions flow from this thinking. In this way, we are modeling what children need to do, not just telling them what to do.

Using a think-aloud strategy in all content areas, for all ages, is one step towards recovering an apprenticeship style of learning, something that has a legacy of great success and efficacy. Have you used a think-aloud lately? Please share with us in the comment section below.

Mind by Design

How the thinking aloud strategy works | Guide to Implementation

The thinking aloud strategy is a form of self-directed metacognition. It is a technique that encourages learners to monitor and evaluate their own thinking as they complete an activity or solve a problem. The thinking aloud strategy can produce benefits such as improved metacognitive skills; enhanced understanding of the task at hand; better recall and organisation of information; enhanced motivation to undertake tasks that learners may otherwise find difficult, tedious, or boring. It is also known as Metacognition in Practice (MPIP) and Process Metacognition (PM).

For the thinking aloud strategy to be effective, learners need to be aware of their own thinking so that they can analyse their own performance. This includes recognising the elements of a problem, selecting how best to approach it, taking time to consider alternative options, and evaluating how well they have achieved their goal.

Why the thinking aloud strategy is important

This strategy is important because it can provide learners with a powerful tool for improving their self-directed learning and self-regulation.

Self-directed learning is the process by which learners plan, prepare, and practise to learn new knowledge relevant to their course of study. It involves planning and organising lessons, preparing goals to work towards, practising strategies to support learning, and monitoring progress through monitoring one’s own performance. It is about having the internal motivation to acquire knowledge in a way that is most suitable for students’ needs.

Self-regulation is the process of managing cognitive demand. It is important to be able to regulate one’s own thinking and behaviour so that it is effective and appropriate in terms of goals and tasks . Self-regulation includes activating relevant knowledge, monitoring one’s own performance, and regulating one’s emotions, motivations, attention, and strategies when working towards goals. The thinking aloud strategy is an effective way to encourage learners to monitor and evaluate their own performance in the process of self-directed learning.

The thinking aloud strategy also encourages learners to gain a better understanding of their own cognitive processes and how they work. By monitoring what they are doing they can identify why they may have problems when completing a task, and what needs to be changed if improvements are required.

How the thinking aloud strategy works

The thinking aloud strategy is a form of self-directed metacognition. This means that learners monitor and evaluate their own performance as they complete an activity or solve a problem. It does not mean being constantly reflective, but rather reflecting on what was done, how the activity fits into one’s learning goals, how well learners are progressing in applying new knowledge to tasks, and what they need to do to improve.

The thinking aloud strategy is a tool that allows learners to engage in self-directed learning and cultivate their own motivation and interest in the activity they are completing or the problem they are trying to solve. It does this by encouraging them to think about what they are doing as they do it so that if any problems come up, they can recognise them and deal with them proactively rather than having to work backwards from the end product. This way, learners can identify problems and correct them before they have much effect on their performance.

Learning is a process of the mind in which existing knowledge is adapted, extended, and challenged. While learning involves a significant amount of internal mental processing, much of it goes on without the learner’s awareness. Learners tend to concentrate so intently on the task at hand that they are unable to attend to what is happening inside their minds. This can result in major misconceptions developing around what they know, which can have serious impacts on their learning and their ability to apply this knowledge in later situations.

A common example of this is the tendency for people to develop incorrect beliefs about mental processes in their own minds. By reflecting on how they work, learners can identify and remove these misconceptions, increasing their self-confidence and increasing their ability to find solutions to problems.

This strategy encourages learners to use information that they have available at that time (i.e., what they know), as well as new information that they need to know so that they can complete the task successfully. This process develops the learner’s own metacognitive skills, making them more aware of their own thinking as it is happening, and therefore more capable of monitoring and evaluating what they are doing.

The thinking aloud strategy will automatically improve a learner’s level of self-regulation if they continue to utilise it in their day-to-day learning. This is because it encourages learners to reflect on what they are doing, think about how well they are doing it, and identify any areas that could be improved.

Where is the thinking aloud strategy most effective?

This strategy is particularly useful when learners take more than one course that involves problem-solving or an area of expertise. For example, many students take science, maths, English as a Second Language (ESL), and French as Second Language (FSL) at the same time simultaneously. In this situation, the thinking aloud strategy can be used in all three courses and can be effective in all areas of study by allowing learners to identify problems associated with each activity and how to resolve them before they become serious impediments.

Students can use this strategy in any situation where they have a task to complete or a problem to solve. It can be very effective in any form of self-directed learning, especially if it is used to monitor the process while one is doing it, rather than when one looks back over what has been done.

This strategy is particularly useful in those situations which require learners to analyse something that they are currently doing (e.g., driving, cooking, reading a book, doing an experiment). It can also be useful in situations where a learner is learning from materials available to them at that time (e.g., studying for an exam, completing homework), as well as when there is no specific material to work from.

The thinking aloud strategy can be used in combination with other strategies, such as the meta-cognitive strategies of monitoring one’s own performance and monitoring one’s own progress. This increases the effectiveness of the thinking aloud strategy, making it more effective in many situations and enabling learners to monitor and evaluate their own thinking process as it occurs.

The thinking aloud strategy can also be used by learners who find that they do not enjoy or are unable to deal with a task or problem they are faced with, but still need to master the task. They might also use this strategy if they have a particular character trait that makes them think too much about things that are beyond their control rather than concentrating on what they can do. It can enable them to break these negative patterns of thought that might otherwise be hard to overcome.

Getting started – How to implement

In order to use this strategy, a learner has to come up with a plan for the task they are trying to complete. They have to imagine what problems might arise along the way and how they will deal with them. They then need to set explicit goals and have a clear idea of what needs to be done in order for them to reach those goals. Finally, they need to bring their plan into play while they are doing the task.

A lot of learners find this strategy difficult to start because they are not used to planning their activities in advance. Some of them know what is supposed to happen but have difficulty figuring out how it is supposed to happen, or how they are supposed to control the process so that it reaches the goals.

If a learner is used to planning their goals in line with the time it will take to complete the task, they can still use this strategy effectively. This is because people who plan early on what they are trying to achieve will not end up with undesirable or illogical plans that work against the goals of that task.

There are different ways in which learners can plan their tasks, but the most common way is by using a plan-do-review cycle (see diagram below). Learners start by setting clear goals for themselves. They have to plan exactly how they are going to achieve these goals, by defining the necessary steps and tasks that will be involved. They need to do this so that the process can be carried out properly and in an orderly fashion.

After setting these goals, learners evaluate their plans, checking for errors in them and also evaluating any uncomfortable feelings they have when thinking about them. This evaluation can take place at any time during the planning process as long as it occurs before learners act on their plans. There are three main reasons for this:

- The feelings of discomfort that a learner has while they are planning their plan may suggest that there is something wrong with the plan. For example, if a learner feels very anxious or stressed about what they have just done, then it may be an indication that their plan is not thought through properly and will not work as well as they expect.

- The uncomfortable feelings can help learners identify possible problems before they become too serious. Once these problems are identified, the learner can think about how they can be solved before they become serious roadblocks.

- If the uncomfortable feelings are not checked, they could cause learners to give up on whatever plan they have just come up with and end up doing nothing about it. If this happens, then it is possible that these feelings may cause learners to give up altogether on their tasks and never achieve their goals.

As a result of evaluating their plans, learners will be better able to identify what was wrong with their plan and how they can avoid making similar mistakes in the future. This will enable them to put the appropriate effort into planning a better course of action for reaching their goal. It is important that they do this on the basis that it is not possible for all plans to always work as intended.

Some learners find it hard to work out why there are feelings of discomfort when they are planning. They wonder why it is wrong to have thoughts of discomfort when planning a task. It is important for these learners to realise that it is not possible to plan an activity without having some kind of feelings about it. In other words, there is no such thing as a “neutral” feeling when planning something and the feeling of discomfort can come in three forms:

- Being anxious or stressed can mean that someone has a problem with their plan and needs to work harder at it until they manage to solve the problem.

- Feeling uncertain about the plan can also mean a problem with the plan. For example, a learner who is unsure about how to start doing something because they do not know if they are supposed to do it first or second may need to add information telling them exactly what needs to be done.

- Having an uncomfortable feeling while thinking about their plan can be an indication of problems with the plan. For example, if a learner is not sure how to break down a problem into steps that would be easy for them, then they should make the breaks more obvious by outlining these and using arrows or other signs to illustrate the steps.

Learners who are used to planning their tasks in line with the time it will take to complete them can still use this strategy effectively. This is because people who plan early on what they are trying to achieve will not end up with undesirable or illogical plans that work against the goals of that task. They will also be able to identify problems with their plans before they become serious and therefore will not have to give up on them.

For example, if a learner is planning on doing their homework for one hour then it might take them longer than expected because they just do not know what to say. They could go back and make a plan using more detailed steps so that they do not end up getting distracted while doing it. They could also make time limits at a certain point in their plan so that they can check if the process is going well or if they need to change some of their planning.

When learners are used to planning in line with the goal, it is not necessary for them to take detailed notes on how things will be accomplished. In fact, it may be better if they do not make notes or go into too much detail because if they describe to other people how they will complete the task, it can become hard for them to remember enough steps involved in the process.

If a learner finds it difficult to plan in line with their goals then it might be best for them to plan for specific tasks rather than continue with their overall plans. This will make them feel less pressure to accomplish the goals. A task is a smaller goal that can be more easily done than attempting a larger goal.

Learners should also try using the plan-do-review cycle for other types of tasks but not as their only means of planning. They can use the plan-do-review cycle as a guideline for planning but they should not use it as their only planning strategy. If they do this then their plans will not be followed because there will be too much emphasis on doing things in a certain way.

Therefore, instead of following a plan as closely as possible, learners should try to have some freedom in how they perform tasks. This will enable them to meet the goals that they have set themselves easier and therefore increase the likelihood that they will complete them more successfully.

Planning a task is not something people should avoid like it was avoiding the plague. In fact, it is a vital skill that everyone who works in an office should master. It is important for them to spend enough time planning their tasks so that they do not end up wasting valuable time doing things they will later regret. Planning can also help them in doing things in a more efficient way as well as identifying problems and solutions to these before they become big issues during the process of completing the tasks.

The plan-do-review cycle is one planning strategy that people can use when they want to accomplish tasks. It is not a strategy that should be used on its own but it can be combined with other techniques to help people become more skilled at planning their tasks. It is important for learners to understand the process of the cycle and how they can evaluate other plans using it. This will help them in planning their activities more efficiently so that they are better able to complete them successfully without wasting time or discomforting themselves.

The main thing is for learners to understand that planning is not something they can avoid but it should be a necessity. If they plan, they would not have to work so hard or get tired when planning and might end up more satisfied with the results of their activity than if they had not planned at all. This in turn will help them to realise that there are many benefits in doing so and therefore make it easier for them to continue doing this.

Similar Posts

What is positive living and how you can do it

In order to live a life that is richer and more fulfilling one needs to have wise strategies in place for consistently developing an attitude of gratitude and positivity. Yes, there are many things in our lives that can be challenging. Yet, if we focus on what’s good, then those things will also become good….

Doing the Right Thing when no one is looking: The Power of Integrity, Even When No One is Watching

In a world that often seems driven by self-interest and instant gratification, the concept of doing the right thing might appear to be overshadowed by personal gain. However, the truth remains that integrity is an indispensable virtue that defines our character and influences our choices, even when no one is looking. As C.S. Lewis once…

Thinking Like A Millionaire (17 Ways to develop the mindset to succeed)

Thinking like a millionaire is the ultimate form of acceptance. It means you know that, if you get certain steps in place, the sky’s the limit for what could be yours. Whether you want to break into acting or start your own business venture, this article has infinite amounts of empowering nuggets of wisdom and…

What productivity tools does Elon Musk use?

Many in the entrepreneurial world have heard of Elon Musk, and know him as a genius. From Tesla to SpaceX, he has had an amazing career in the tech industry. In fact, it is no coincidence that this article is all about him and his productivity tools. This article will explore all of Elon Musk’s…

What is quantum creation? Why it’s important to your mindset.

Quantum creation is the idea that an observer creates reality. Quantum creation can be seen as a process of observation and interaction created by the observer. The subject is hotly debated concerning what actually happens, but what it implies is unlimited potential for growth, creativity, and imagination. Joe Dispenza, one of the leading experts on…

How to raise your vibration: 15 ways to lift your vibration.

In the world of spirituality, there are complex, lofty concepts that can seem overwhelming and almost entirely intimidating. However, raising your vibration doesn’t have to be complicated or unattainable. The following post will help you get started on your path to increasing your spiritual power. The concept of spiritual vibrations is used to explain that…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Terms and Conditions - Privacy Policy

Responding to Student Understanding Guide: Secondary Math

- Decision Tree

- Diagnosing Misconceptions

- Think Aloud

What is it?

How to do it, considerations, recommended resources.

- Select, Sequence & Connect

- Select & Connect (i.e., Show Call)

- Multiple Methods & Representations

- Model the Process

- Push Students to Justify and Summarize & Continue Instruction

- Modeling with Self-Monitoring and Cues

A Think Aloud is an oft-cited method for use in a wide variety of teaching scenarios, and, when executed well, is a great go-to for adjusting instruction (as well as addressing unfinished teaching in future lessons). Think Aloud's are effective only if they make transparent the cognition required to effectively address misconceptions. This means voicing what you are thinking aloud, to yourself, for students to observe. Students also must have a specific question in mind when observing to focus what they see and hear on the error and false beliefs.

There are infinite ways to execute a Think Aloud for any given scenario, yet they are all structured to set students to focus on teachers’ modeled cognition. In an effective think aloud teachers:

Model the thinking process orally and in writing

Ask questions at strategic moments to leverage students’ prior knowledge in the process

Use economy of language to present the ideas with as few words as possible

Ask a question(s) to check for understanding and stamp key ideas before moving on

Below is that structure and an example script a teacher may use that incorporates the characteristics above. Note, this Think Aloud happens in-the-moment and, to isolate a misconception, the teacher sets a focus on one question that will be discussed after the thinking is fully modeled.

Implementing a Think Aloud in the moment, as opposed to pre-planned, requires you to determine:

If students must observe cognition of a concept, a process or an application to clarify the misconception;

Which Standard(s) of Mathematical Practice to model;

The length of the thought process, which should be short enough for students to apply right away as you release responsibility once again;

The Depth of Understanding students require to clarify the misconception and to attain the learning goal.

- Get Better Faster: A 90-day plan for developing new teachers By: P. Bambrick-Santoyo, (2016)

- << Previous: Adjusting Instruction

- Next: Select, Sequence & Connect >>

- Last Updated: Feb 8, 2024 4:08 PM

- URL: https://relay.libguides.com/responding-to-student-understanding

Think Aloud

- Select a central text .

- Project the text in a visible location.

- Asking questions

- Connecting to other texts

- Making predictions

- Narrating thoughts while reading

- Reviewing for information

- Summarizing

- Surveying for text features

- Using evidence from the text to respond

- Visualizing

- Highlight part of the text conducive to demonstrating the skills you selected for the mini-lessons. Model the skills aloud.

- Have students record the skills you demonstrate on the Think Aloud checklist.

- After modeling Think Aloud, have students practice with a partner or in a small group, using the Think Aloud checklist as a talking guide.

- Observe and scaffold students during partner or small group Think Aloud. These observations can function as formative assessments.

English language learners

Connection to anti-bias education.

- Student sensitivity.

- The Power of Advertising and Girls' Self-Image

Print this Strategy

Please note that some Strategies may contain linked PDF handouts that will need to be printed individually. These are listed in the sidebar of this page.

- Google Classroom

Sign in to save these resources.

Login or create an account to save resources to your bookmark collection.

Learning for Justice in the South

When it comes to investing in racial justice in education, we believe that the South is the best place to start. If you’re an educator, parent or caregiver, or community member living and working in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana or Mississippi, we’ll mail you a free introductory package of our resources when you join our community and subscribe to our magazine.

Get the Learning for Justice Newsletter

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

What is going through your mind thinking aloud as a method in cross-cultural psychology.

- Department of Psychology, University of North Florida, Jacksonville, FL, United States

Thinking aloud is the concurrent verbalization of thoughts while performing a task. The study of thinking-aloud protocols has a long tradition in cognitive psychology, the field of education, and the industrial-organizational context. It has been used rarely in cultural and cross-cultural psychology. This paper will describe thinking aloud as a useful method in cultural and cross-cultural psychology referring to a few studies in general and one study in particular to show the wide applications of this method. Thinking-aloud protocols can be applied for (a) improving the validity of cross-cultural surveys, (b) process analysis of thoughts and the analysis of changes over time, (c) theory development across cultures, (d) the study of cultural meaning systems, and (e) individual as well as group level analyses allowing hypothesis testing cross-culturally. Limitations of the thinking-aloud method are also discussed.

Introduction

Thinking aloud is the concurrent verbalization of thoughts while performing a task ( Ericsson and Simon, 1993 ). When this method is applied, participants are asked to spontaneously report everything that goes through their minds while doing a task, and they are instructed not to interpret or analyze their thinking. Verbal protocol is another term often used as a synonym for thinking aloud. Verbal protocols can be concurrent (thinking aloud) or retrospective, referring to short reports after the completion of a task.

The study of thinking aloud and of verbal protocols has a long tradition in psychology. It can be traced back to Wilhelm Wundt’s technique “Selbstbeobachtung” (self-observation, also often called introspection; Wundt, 1888 ). Wundt asked participants in his experiments to look inward, pay attention to their inner thought processes, and describe them in detail. Wundt perceived the inner experience, the flow of consciousness, as the core topic of psychology. He saw self-observation as an appropriate method for studying this flow of consciousness when it occurred under controlled conditions in the laboratory. Some researchers criticized the method, believing that self-observation would interfere with the thought process and, thus, would not show the real thought process itself, but rather an interpretation of the thought process ( Ericsson and Crutcher, 1991 ).

The thinking-aloud method was heavily criticized by behaviorists, as they assumed cognitive processes, such as memory, could not be studied scientifically. As Watson (1925) expressed, “The behaviorist never uses the term memory . He believes that it has no place in an objective psychology” (p. 177). The thinking-aloud method became popular again after the influence of behaviorism diminished in mainstream psychology and cognitive psychology became the dominant paradigm. Newell and Simon (1972) , for example, asked participants to think aloud while solving particular problems. Rather than investigating whether a person solved a problem or not, their focus was on the process of human reasoning while solving problems. From these thinking-aloud protocols, they derived the computer-simulated model “General Problem Solver.”

A study conducted by Ericsson and Chase (1982) on exceptional memory showed that a student could increase his digit span from 7 (e.g., 3-5-1-3-7-8-2), the average number of digits a person is able to remember, to 80 digits by training 1 h per day, three to five times a week for 20 months. Retrospective verbal protocols showed that the participant used specific mnemonics to help him remember. One mnemonic was to group the digits together in meaningful units, which is called chunking. For example, the three digits 3 5 1 could be grouped together as one chunk of “3 min 51 s – close to world record mile time,” which, if the participant was a long-distance runner, as this participant was, would make sense and, thus, would be easier to remember. Since the publication of Ericsson and Chase’s work, thinking aloud has been recognized as an acceptable and even essential method in the study of human cognition.

The Wide Application of the Thinking-Aloud Method

Thinking aloud as a scientific method has been used in many other disciplines, showing the relevance and applicability of this method. Not only researchers studying cognition (e.g., Fleck and Weisberg, 2004 ; Hölscher et al., 2006 ; Malek et al., 2017 ), but also researchers studying education (e.g., Cummings et al., 1989 ; van den Bergh and Rijlaarsdam, 2001 ; Bannert, 2003 ; Kesler et al., 2016 ), text comprehension using computer based tools ( Muñoz et al., 2006 ; Van Hooijdonk et al., 2006 ; Wang, 2016 ), discourse processing ( Long and Bourg, 1996 ), software engineering ( Hughes and Parkes, 2003 ), psychology and law ( Santtila et al., 2004 ), sport psychology (e.g., Samson et al., 2017 ), and business management ( Isenberg, 1986 ; Premkumar, 1989 ; Hoc, 1991 ) have applied the thinking-aloud method. In a similar form, thinking aloud has also influenced the fields of counseling and clinical psychology, for example, in the assessment of automatic thoughts as part of cognitive therapy in depression (e.g., Meichenbaum, 1980 ; DeRubeis et al., 1990 ).

Reliability and Validity of Thinking-Aloud Protocols

Following positivism, reliability and validity are central to research. Reliability of thinking-aloud data refers to consistency, the ability to collect the same data at a different time. In order to get reliable data, a clearly understandable, tape or digitally recorded thinking-aloud protocol is necessary, which requires control of the experimental situation. Problems related to transcribing and especially to coding have to be minimized, and, ideally, transcription should be done by native speakers of the participants’ language. The first step of coding is the segmentation of the whole protocol, i.e., the creation of separate meaningful units, depending on the research questions of interest. Usually those statements are in the form of clauses or sentences; these sentences do not need to be complete, necessarily, as participants use colloquial language. The second step refers to the coding of the segments. A detailed coding system and thorough training of coders can increase reliability, resulting in higher inter-coder reliability. This reliability is sometimes described in percent of agreement, but preferably should be described in Cohen’s Kappa or intraclass correlation coefficients. According to Fleiss (1981) , a Kappa value over 0.75 is excellent, between 0.60 and 0.75 is good, and a Kappa between 0.40 and 0.60 is fair. One problem that may be encountered during coding is coder biases or expectations, as can occur when the coders are aware of the hypotheses to be tested, for example. Ideally, then, the coders should not know about the research hypotheses. Also, probable biases or expectations can be acknowledged early to increase trustworthiness of the coding process and, consequently, of the data.

Also at issue is the internal validity of a study. In the context of thinking aloud, the validity question is often framed as the reactivity question. Does the act of thinking aloud interfere with and change a person’ cognitive processes while performing the task? Ericsson and Simon (1993) argued that it did not, citing many studies and stating that as long as the instruction was clear, i.e., that participants should say out loud everything that went through their minds, thinking aloud did not alter the sequence of thoughts. However, prior consideration should be given to the way instructions are to be conveyed to participants. An instruction from a facilitator to “keep talking” while the participant performed a task probably would not disrupt the thought process, though an instruction requiring explanation from the participant, like “Tell me why you did this,” would intervene in the cognitive process by triggering a specific answer to explain an action. If verbal protocols are asked from participants after completion of tasks, it is preferable if verbalization almost immediately follows the task. Generally, a concurrent thinking-aloud protocol has higher validity than a retrospective report, particularly when the task takes a long time to complete.

One way to ensure reliability and validity and to determine whether thinking aloud influences a cognitive process is to create two groups: an experimental group that receives instruction to think aloud, and a control group that does not receive such instruction.

Qualitative Evaluation Criteria: Trustworthiness of Thinking-Aloud Protocols

Researchers conducting qualitative studies use different criteria to evaluate the quality of their research. Whereas quantitative psychologists try to discover general universal laws, qualitative researchers try to understand participants’ “lived experience” ( Hesse-Biber and Leavy, 2006 , p. 62), assuming a socially constructed reality. Lincoln and Guba (1999) described four criteria guaranteeing the trustworthiness of the research: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility refers to how confident one can be regarding the truth of a study’s findings. One way to support credibility is to be open to the possibility of falsification and to conduct a “negative case analysis” ( Hesse-Biber and Leavy, 2006 , p. 63), i.e., to include cases that contradict or are not in line with the conclusions drawn so far. It speaks for the researcher if he or she is willing to include those cases in the analysis and, as a result, is able to revise the previously drawn conclusions. A second method to support credibility is triangulation. Triangulation can refer to the use of several methods or several sources of information to investigate the same research question. Thinking aloud, for example, could be combined with post-experiment interview or survey data. Triangulation can also refer to different investigators working on the same data set. This is especially relevant for cross-cultural studies and analyses of thinking-aloud protocols. The underlying assumption of triangulation is that it provides a fuller and more credible picture of the phenomenon. Extended experience in the environment can also increase credibility, and it is especially important for cross-cultural psychologists to learn about the other culture and learn the language in order to get a deeper understanding of the utterances made by the participants in the thinking-aloud protocols.

Transferability refers to the application of the findings to other contexts or other people. Quantitative researchers pursue random sampling. Qualitative studies often include small sample sizes and pursue purposive sampling with the goal of getting a wide variety and range of information that can increase the transferability.

Dependability is the third criterion and refers to a study’s reliability. Confirmability, the fourth criterion, refers to the accuracy of findings, and to what extent they were influenced by the researcher’s biases. Researchers can increase both dependability and confirmability by journaling their experiences and biases and by engaging in dialog with other researchers early on in the research process. Participatory research and peer review ( Willis, 2007 ) can also increase dependability and confirmability. In participatory research, the researcher presents initial conclusions of the study to the participants and actively involves them in the research process. For example, thinking-aloud protocols could be shown to and discussed with the participants and ambiguities in the protocol could be clarified. Peer review is similar to triangulation involving other researchers. In cross-cultural research, the ideal, as mentioned before, would be collaboration with a researcher from the target culture. It is recommended to involve other researchers early in the research process and to stay in continuous dialog with them about the research progress.

Cross-Cultural Psychological Research Using Thinking-Aloud and Verbal Protocols

One goal of cross-cultural psychology is “the study of similarities and differences in individual psychological functioning in various cultural and ethnocultural groups” ( Berry et al., 2002 , p. 3). The thinking-aloud method, however, is rarely used in cross-cultural research. A search in PsychInfo, January 2018, with no time limitation showed 503 hits for the term “thinking aloud” used anywhere and 464 hits for the term “verbal protocols” used anywhere. Only six peer-reviewed journal articles were found for the combination of the word “thinking aloud” or “verbal protocol” anywhere with either one of the two keywords “culture” or “cross-cultural.”

Luria (1976) studied reasoning, among other cognitive processes, in Central Asia, comparing illiterate peasants (the term used by Luria), barely literate kolkhoz farm workers, and young people with a few years of schooling. He used an interview technique to investigate the thought processes of the participants. He presented participants with syllogisms such as the following: “Cotton grows well where it is hot and dry. England is cold and damp. Can cotton grow there or not?” (p. 107).

Results showed that illiterate participants who had no formal education had difficulties solving the syllogisms. Luria was not only interested in the outcome, how many of the participants of each group could solve the syllogism correctly, but even more so in their reasoning, how they interpreted the syllogism. The illiterate participants interpreted the syllogisms on the basis of their experiences in a concrete way and did not show abstract thinking. Only the analysis of participants’ thought processes allowed Luria to answer the question of why illiterate participants had difficulties interpreting the syllogisms.

The following is part of a short conversation the interviewer had with a 37-year-old illiterate villager who was presented with the cotton syllogism. It is, however, more an interview than a mere thinking-aloud protocol.

Interviewer: “Cotton can grow only where it is hot and dry. In England, it is cold and damp. Can cotton grow there?”

Participant: “I don’t know.”

Interviewer: “Think about it.”

Participant: “I’ve only been in the Kashgar country. I don’t know beyond that.”

Interviewer: “But on the basis of what I said to you, can cotton grow there?”

Participant: “If the land is good, cotton will grow there, but if it is damp and poor, it won’t grow. If it’s like the Kashgar country, it will grow there too. If the soil is loose, it can grow there too, of course” ( Luria, 1976 , p. 108).

Luria also used grouping tasks where participants were presented with several objects and had to find, which ones belong together and which ones did not. This task assesses categorical classification. The following is the response of a 60-year-old illiterate peasant who was shown pictures of a hammer, a saw, a log, and a hatchet.

They all fit together! The saw has to saw the log, the hammer has to hammer it, and the hatchet has to chop it. And if you want to chop the log up really good, you need the hammer. You can’t take any of these things away. There isn’t any you don’t need ( Luria, 1976 , p. 58).

This thinking-aloud statement related to the classification task shows the participant’s situational thinking. The participant does not classify the objects into a more abstract category, but refers to their “practical utility” (p. 59). Similar studies on formal and informal education and its influence on problem solving, reasoning, or intelligence were reported by Scribner (1979) and Scribner and Cole (1981) , who also instructed participants to verbalize their thoughts when solving certain cognitive tasks. These studies show that thinking aloud can tap into information that cannot be analyzed by other methods alone, explaining the differences or accessing the nuances usually not revealed through other forms of data gathering.

Cultural Meanings 1: Improving the Validity of Cross-Cultural Surveys Using Thinking Aloud

Raitasalo et al. (2005) used the thinking-aloud method in a cross-cultural study in Finland, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands to investigate cultural differences in answering survey items. The survey focused on alcohol use: frequency of drinking, quantity of drinking, frequency of drunkenness, and the context of drinking in the last 12 months. For our purposes, the major finding of interest is cross-cultural differences related to the understanding of the survey questions. We can conclude from this study that allowing participants in cross-cultural studies to verbalize or write down their thoughts when answering Likert-scale survey questions could show the researcher(s) how the participants understand the questions and which cultural meanings participants attribute to these questions. Thinking aloud can also point out the interpretations participants give to the survey questions.

To illustrate this point, I would like to quote two survey questions used in studies published in the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology . The first one refers to Keller et al. (2006) , who used the Family Allocentrism Scale ( Lay et al., 1998 ) as one of their measurements. Lay et al. tested for response bias and conducted item analyses with western and eastern samples when they developed their survey. One item of this scale is “My family’s opinion is important to me.” Thinking aloud of participants from different cultural groups regarding this question could be especially beneficial in the first stages of scale development and could reveal (a) if participants think of specific family opinions, (b) if so, which ones they are referring to when answering this question, and (c) who and what defines family: a nuclear family; an extended family with grandparents, uncles, aunts; only one caregiver; or if family is interpreted as only the participant, the individual. One western participant could express, for example: “No, their opinion is not important to me when they want to tell me which clothes I should wear.” Another participant could say, “Sure, I listen to their advice regarding my future major at the university. After all, they will support me.” Another participant might say, “I listen to my mom, because she understands me, but not to my dad, and certainly not to my brothers.” These different answers show that participants understand the question in different ways and participants’ answer choices depend on what they are thinking of at the time. One could specify the question, for example: “My mother’s opinion regarding my professional future is important to me.”

A second example is an item Hershey et al. (2007) used studying retirement planning in the Netherlands and in the United States, a single-item indicator for perceived savings adequacy: “I am saving enough for retiring comfortably.” A participant in Germany might choose, “1-strongly disagree,” thinking aloud, “I do not need to save and I did not save, because I always paid into the social retirement system and I am guaranteed a retirement from the government.” An Indian participant might also choose, “1-strongly disagree,” thinking aloud, “I do not need to save, because I have four children and they will take care of me; one of them is even a computer programmer in Hyderabad.” Additionally, a Filipino might also choose, “1-strongly disagree,” but say, “No matter how hard I try, I will never be saving enough for retirement, there is no well-functioning system of retirement here. We grow old, we stay with our family, we are loved.” Even if the German, Indian, and Filipino have the same survey answer, all indicating that they are not saving for retirement, their thinking-aloud statements show that the underlying reasons for their responses are quite different. The researcher could use those thinking-aloud data to specify the question and perhaps to develop further questions to lessen misinterpretation, garner more accurate responses, or even to be more sensitive to participants’ culture. Possible modified items could be “The government is supporting retired people adequately.” And “I can rely on my family to support me financially when I retire.”

The use of thinking aloud and verbal protocols can be especially helpful when surveys try to assess sensitive topics, meaning topics subject to bias and social desirability, and to those that attempt to be respectful to the context and the larger dimensions of the culture. Edwards et al. (2005) , for example, conducted a study on condom use as a preventive measure for HIV/AIDS. They collected thinking-aloud protocols of sex workers problem solving a simulated task. The goal was to improve a sexual behavior survey instrument. The thinking-aloud data helped the authors to improve comprehension of the instrument and to reduce social desirability, providing appropriate terms and cues for aiding recall, improving the establishment of trust with participants, and creating a sense of cultural competence and credibility from the researchers. Vreeman et al. (2014) transcribed and coded cognitive interviews regarding HIV with pediatric caregivers in Kenya in order to further develop and adapt survey items to this cultural context.

Cross-cultural psychologists have a multitude of quantitative methods to increase reliability and validity of survey instruments used in cross-cultural research (for an overview, see van de Vijver and Leung, 1997 ; van de Vijver and He, 2017 ). The thinking-aloud method is an additional method that can be used to improve the reliability and validity of self-report instruments ( Sudman et al., 1996 ).

Cultural Meanings 2: Thinking Aloud Allows for the Study of Cultural Meaning Systems Beyond the Sentence Level

The previous paragraphs referred to cultural meanings attributed to specific survey items on the sentence and phrase level. Thinking-aloud data can be also analyzed more broadly regarding the meanings expressed by participants going beyond the sentence level. A multitude of other qualitative methods, such as consensual qualitative research methodology ( Hill et al., 1997 ; Güss et al., 2018 ) or grounded theory ( Glaser and Strauss, 1980 ) can be applied to analyze thinking-aloud protocols for meanings expressed by participants of various cultural and ethnic groups. As Smagorinsky (2001) pointed out, “from a cultural perspective a verbal protocol represents the speaker’s cultural conception of the word” (p. 235) and gives insight into his or her cultural world. Needless to say, analysis of such protocols necessarily requires coders from the participants’ respective cultures or coders who are multiculturally competent – not only knowledgeable about other cultures, but deeply aware of their own biases and prejudices.

Concrete Examples of Thinking-Aloud Data Analysis From One Cross-Cultural Study

A study by Güss et al. (2010) illustrates the different options for data analysis using thinking-aloud protocols. The study was conducted in Brazil, Germany, India, Philippines, and the United States with over 500 participants. They were instructed to think aloud while working on two computer-simulated problem -solving tasks. One of the tasks was a computer simulation in which participants took the role of a fire-fighting commander who had to protect three cities and forest from approaching fires. Participants always spoke in their native languages when they thought aloud. However, Indian and Filipino participants often spoke in English. We encouraged participants to use the language they were most comfortable using to minimize potential influences of thinking aloud on the problem-solving process. All the thinking-aloud protocols were tape-recorded, transcribed, and coded. Student volunteers in every country were trained how to transcribe and code the protocols. During the training, the coding system was explained and defined, examples were given, coding was practiced, and the differences between the subcategories were discussed.

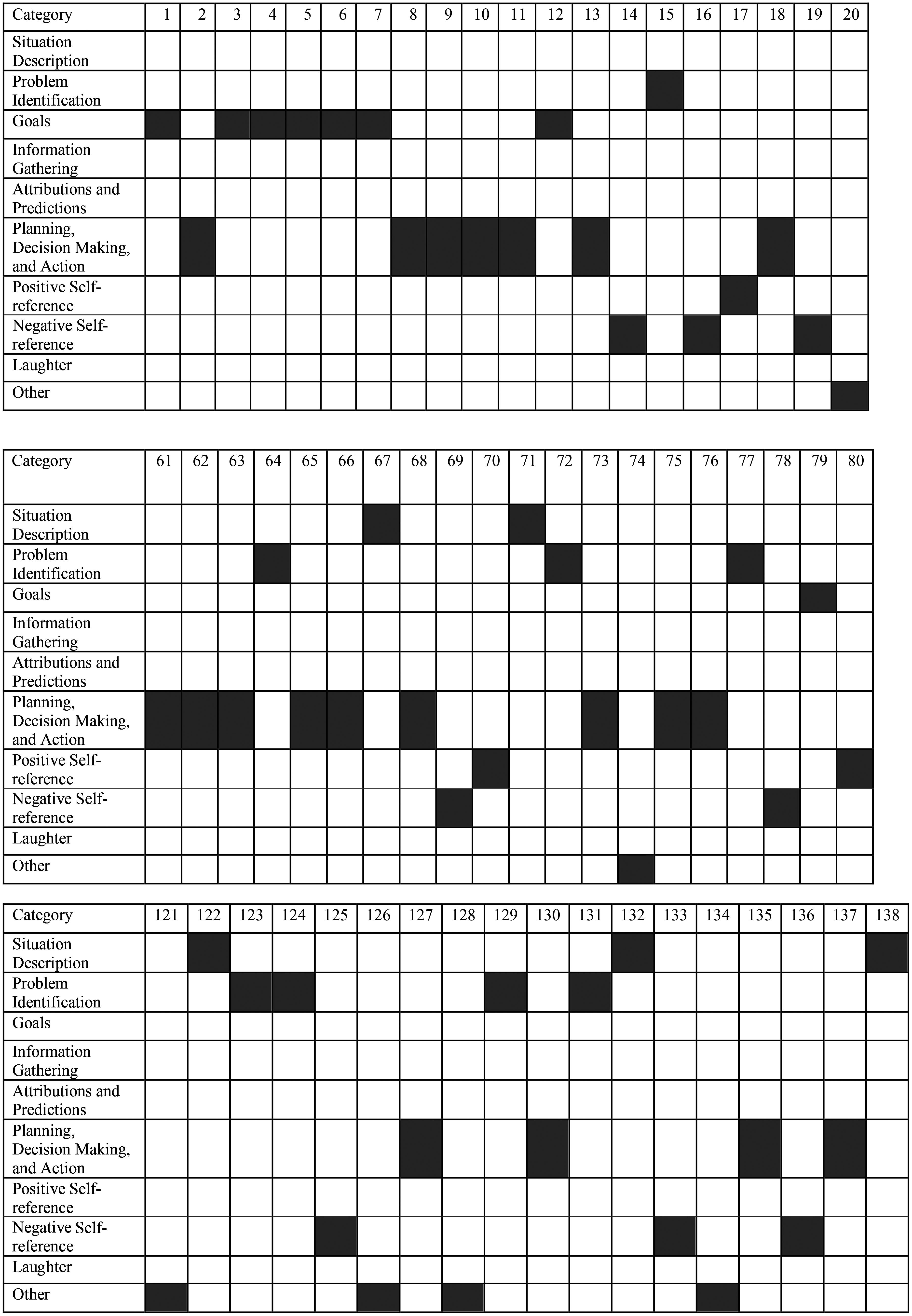

Each thinking-aloud protocol was transcribed into Microsoft Excel, so that every statement expressing an idea unit filled one cell. The following example has two different idea units and was therefore transcribed into two cells: “I send truck 5 to city 1 // and then I will clear the forest.” Statements were then coded according to the problem-solving stages. The coding system was initially created following the western stage model of problem solving: problem identification, goal definition, information gathering, mental model building, planning of solutions, prediction of further developments, decision-making, action, evaluation of outcome, and modification of strategic approach (e.g., Bransford and Stein, 1993 ; Dörner, 1996 ). The system was then modified to account for other statements made by participants. These statements referred to emotions and self-descriptions. The final coding system consisted of 21 categories that were summarized in 8 main categories ( Güss et al., 2010 ).

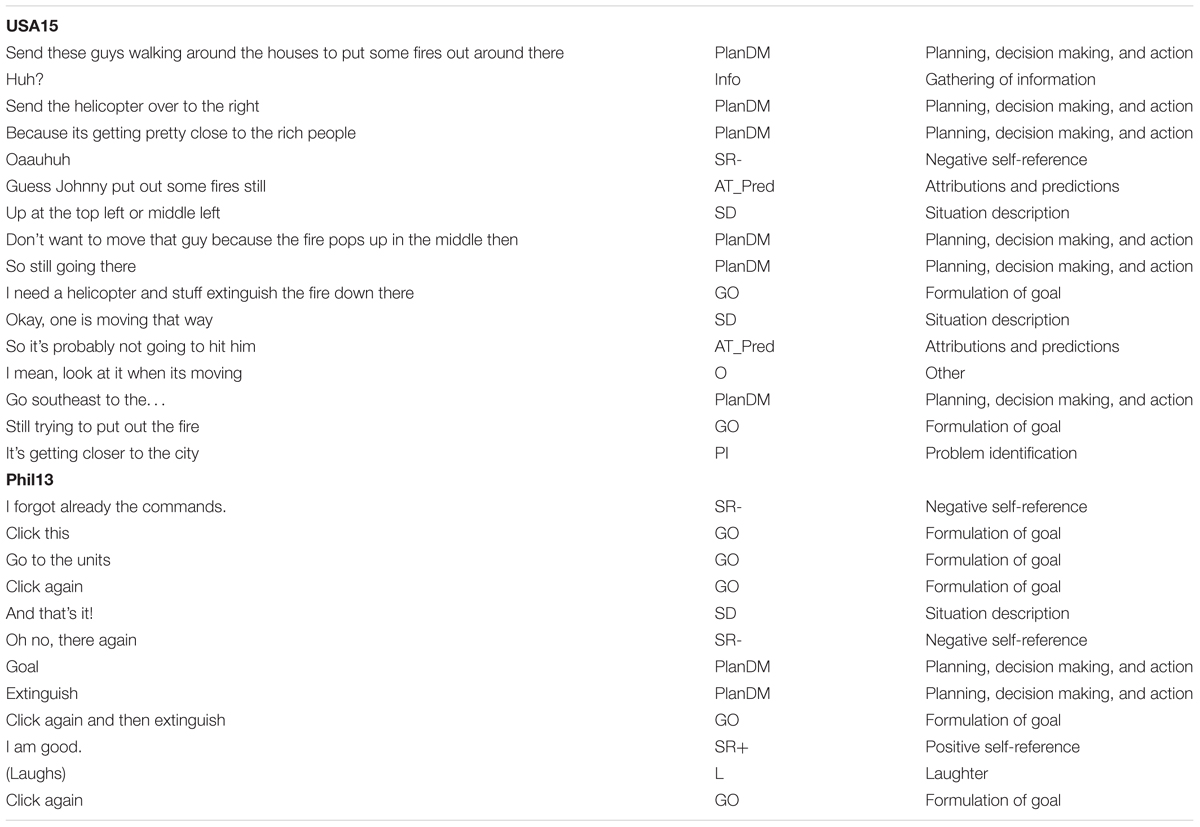

Testing Theories Across Cultures Using Thinking Aloud

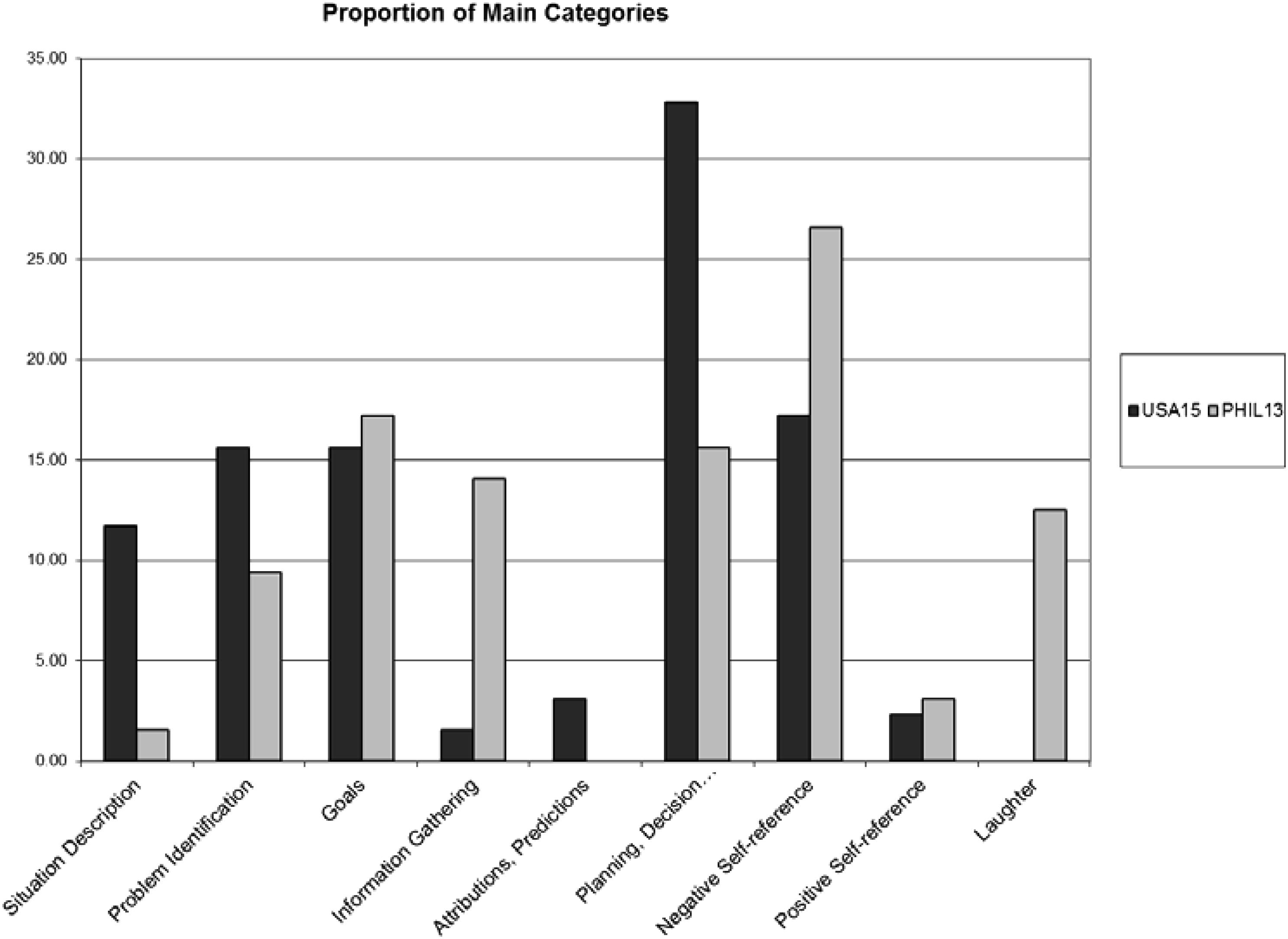

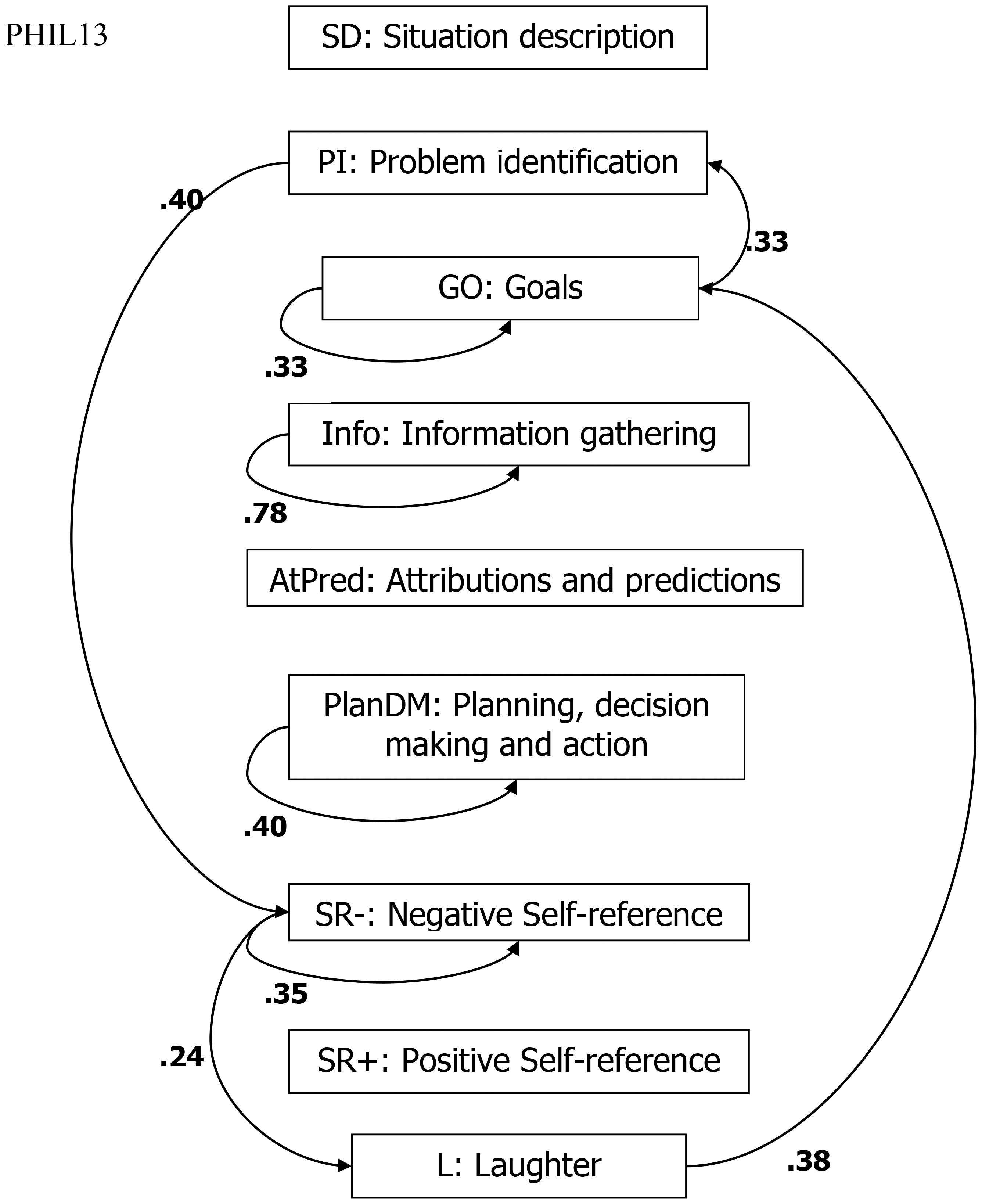

Table 1 contains verbatim parts of participants’ thinking-aloud protocols and includes statements from one U.S. participant (USA15) and one Filipino participant (Phil13). The coding is also indicated (the full coding system is available upon request). These data can be used to test specific hypotheses. Based on a literature review (e.g., Nisbett, 2003 ), one hypothesis could refer to a more problem-centered and solution/action-oriented focus on problem solving for U.S. participants and a more context-centered focus for Filipino participants. The frequency of categories can be counted and either absolute or relative frequencies can be shown. Figure 1 shows relative frequencies as the time required to complete the thinking-aloud protocols and the number of statements for the U.S. and Philippine participants differed.

TABLE 1. Coding and idea unit examples transcribed from a study using the thinking-aloud method.

FIGURE 1. Proportions of categories expressed in thinking aloud for U.S. and Filipino participant (excluding other statements).

The distribution of the problem-solving categories of the complete thinking-aloud protocols shows which categories were used frequently and which ones were not. The most frequent category expressed by the U.S. participant (USA15) was planning, decision-making, and action – roughly one-third of all statements. For the Filipino participant (Phil13), the most frequent category, expressed in more than a quarter of all statements, was negative self-reference (SI). The distribution of the categories differed significantly between the U.S. and Filipino participant, χ 2 (169) = 200.27, p = 0.05. The U.S. participant showed relatively more situation description, PI, attributions and predictions, and planning, decision-making, and action. The Filipino participant expressed relatively more information gathering, negative SIs, and laughter. The two participants’ data support the hypotheses. Indeed, results indicated a dominance of categories related to problem identification and problem solution for the U.S. participant and a dominance of information gathering to understand the problem context and less solution-focus for the Filipino participant.

The analysis here refers only to thinking-aloud protocols of two individuals. The same analysis could be conducted for averages of thinking-aloud protocol categories among different cultural groups. Especially when referring to cross-cultural differences and when claiming reliable cross-cultural differences, then the data should be compared at the group level rather than individual level. In fact, a comparison of over 400 Brazilian, German, Filipino, Indian, and U.S. participants’ thinking-aloud protocols shows significant cross-cultural differences among exactly these problem-solving categories with medium to large effect sizes ( Güss et al., 2010 ).

Testing Cross-Cultural Generalizability of Psychological Theories Developed in Western Societies Using Thinking Aloud

The analysis of the thinking-aloud protocols can also be used to test theories that were developed in western industrialized countries for their cross-cultural validity. The dominant theory on problem solving developed in the United States (e.g., Bransford and Stein, 1993 ) and Europe (e.g., Dörner, 1996 ) suggests that problem solvers go through certain stages while solving problems. These stages are clarification of goals, gathering information, prediction of further developments, planning, decision-making, action, and evaluation of effects. In the Güss et al.’s (2010) study, many of these stages were indeed found in the thinking-aloud protocols of participants in all five countries. What the western stage model did not consider, however, were statements referring to negative and positive emotions and statements referring to negative and positive self-evaluations (e.g., “I will never be a good fire fighter”). Our data from the five countries showed that problem solving is not solely a cognitive process, but interacts with emotional and self-evaluative processes. The thinking-aloud data from the five countries support the existing stage model. On the other hand, they provide the basis to further develop the model and include emotional and self-evaluative processes.

Testing Predictions and Differences in Performance Using Thinking Aloud

The thinking-aloud data can also be used as independent variables to test the influence on a dependent variable. One question relevant to the data of the U.S. and Filipino participant refers to which stages can predict performance in the fire simulation. Is it always the same stage or do these stages vary cross-culturally? Analyzing the demands of the simulation, i.e., the development of many fires and the requirement to extinguish them fast to avoid their spreading, indicates that the most crucial of the stages is planning, decision-making, and action. Although cross-cultural differences are expected in the frequency of the categories, it is likely that across cultures the same stages predict performance due to the specific task demands. USA15 protected 68.1% of the forest at the end of the simulations, Phil13 protected 53.1%. Correlations and regression analyses would allow testing those predictions referring to groups of participants. The correlation of performance in the simulation with the frequency of planning, decision-making, and action controlling for the overall number of statements made was r = 0.11, p = 0.04 ( N = 349). This relationship, however, was not significant for the U.S. sample, r = 0.13, ns ( n = 64), and only marginally significant for the Filipino sample, r = 0.22, p = 0.08 ( n = 62).

The effect size (i.e., r ) is smaller in the overall analysis across the United States and Filipino cultures than those within individual cultural samples. However, because of the difference in sample size, the correlation was only significant for the overall analysis. Thus, in this specific case, the result does neither support cultural universality nor cultural differences.

Analysis of Transitions in the Process Using Thinking Aloud

The thinking-aloud data can be analyzed in more detail. One might ask, for example, if the Filipino participant’s laughter is a positive expression related to happiness and other positive emotions or if it is nervous laughter, a coping mechanism relieving negative emotions and tensions. Another question of interest could be related to cultural strategies in problem solving. What do participants do when they identify a problem – for example, a new fire spreading close to one of the cities?

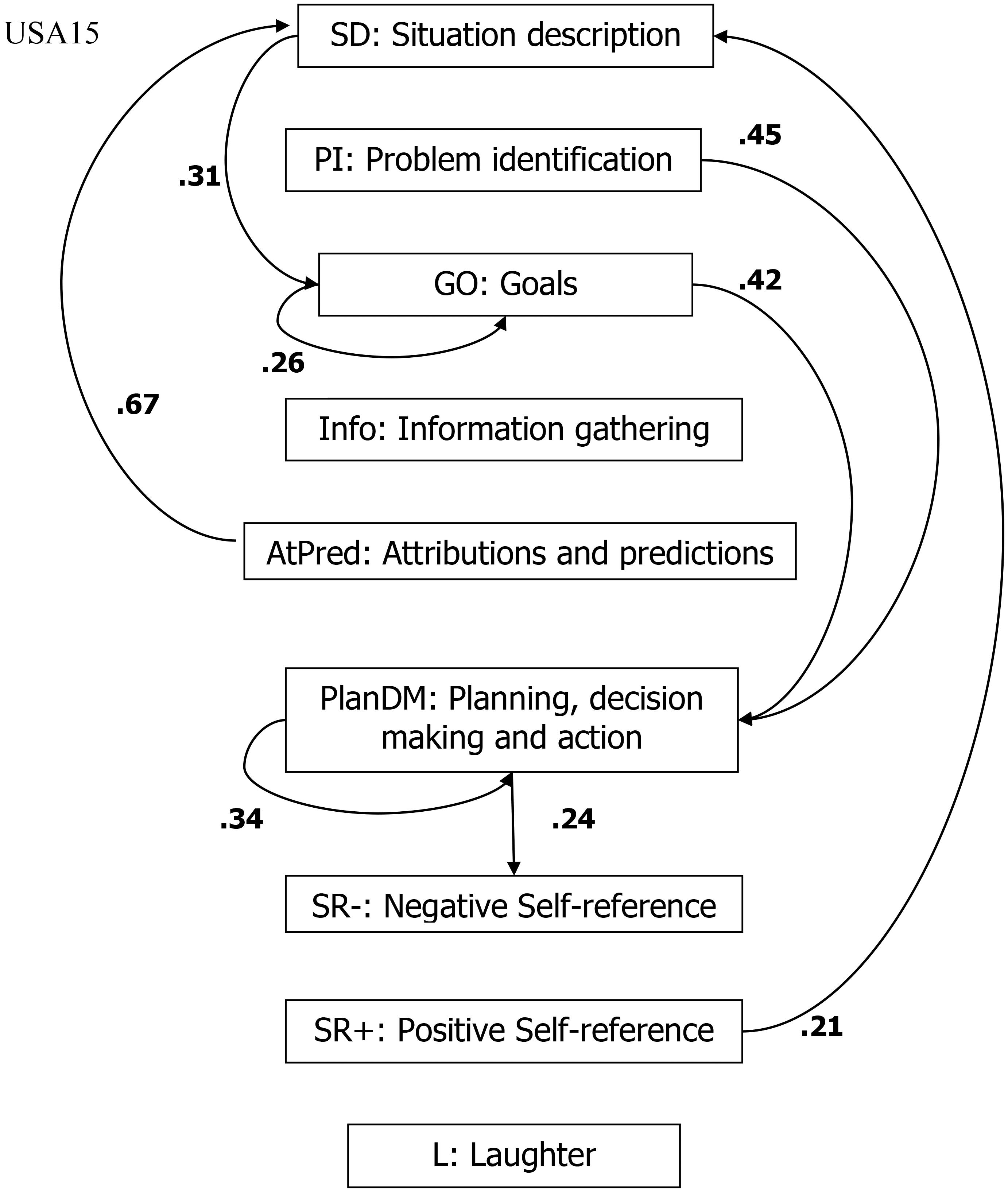

These questions can be answered analyzing the transition probabilities between the stages, also called lag analysis ( Bakeman and Gottman, 1986 ) or latent transition analysis ( Lanza et al., 2005 ). The transitional probability (TP) from any category x to another category y is given by TP ( x → y) = frequency ( xy )/frequency ( x ).

We could examine the thinking-aloud protocols to discover what statements the Filipino participant made before laughing (L). What is the probability that laughing ( y ) follows negative self-reference statements ( x )? Or, what statements were made by both participants after they identified a problem (PI)? This analysis can be quite tedious when done manually in long or multiple protocols, so we developed a computer program ( Parise and Güss, 2006 ) that can read the coded files and give an output file with all the possible transitions. The most frequent transitions in the thinking-aloud protocols of USA15 and Phil13 are shown in Figures 2 , 3 . The figure for PHIL13 shows that laughter was preceded in 24% of all transitions by negative self-reference statements. This might indicate that laughter was used to cope with negative emotions and negative self-evaluations.

FIGURE 2. Lag analysis: most frequent transitions (excluding other statements) for USA15.

FIGURE 3. Lag analysis: most frequent transitions (excluding other statements) for Phil13.

The question above about statements made after PI had to do with culture-specific ways of dealing with problems. The Filipino transitions showed that after PI, the most frequent reaction was a negative self-reference statement (40%). The U.S. participant reacted differently. In the figure showing the U.S. participant’s transitions, the most frequent transition from PI was to planning, decision-making, and action (45%). Whereas the Filipino reacted to PIs with negative emotions and self-evaluations, the U.S. participant proceeded right to the solution process.

The previous analyses referred to one Filipino and one U.S. participant. We also created a program ( Edwards, 2018 ) that compiles all the transition frequencies of the 74 Filipino and the 67 U.S. participants. Although laughter happened almost six times more often in the Filipino sample, it was preceded by negative self-references in 24.6% in the U.S. sample and in 23.2% in the Filipino sample. The differences we discussed before regarding laughter were not found in the two overall cultural samples.

We also analyzed the thinking-aloud protocol transitions for all Filipino and all U.S. participants regarding the stages following PI. Overall, U.S. participants mentioned problem statements twice as often as Filipino participants. Whereas negative self-references followed PI in 14.3% in the U.S. sample, planning, decision-making, and action followed in 53.4% of all transitions. In the Filipino sample, negative self-references followed slightly more often, namely in 16.1% and planning, decision-making, and actions only in 14.4% of all transitions after PI. The tendency we discussed before to proceed with planning and decision-making after a problem is identified was also found in the U.S. sample overall.

The statistical significance of transition probabilities can be tested using chi-square tests and comparing the probabilities with the probabilities expected by chance. If several chi-square tests are run, alpha levels can be adjusted using Bonferroni to reduce Type I error. The example given refers to two-way timetables, i.e., only one stage following another stage was analyzed. The sequences are also called a Markov chain. Depending on the theoretical question, it is also possible to investigate patterns larger than a combination of two, for example, a sequence of PI – negative SR- – planning, decision-making, and action (PlanDM). Statistical methods can help to determine the order of the Markov chain and to test the homogeneity of the transition frequencies ( Gottman and Roy, 1990 ; Bakeman and Quera, 1995 ; Muthén and Muthén, 2017 ).

Studying Changes Over Time Using Thinking Aloud

Thinking-aloud data allow another analysis of the process as well. A researcher might be especially interested in changes that happen over time. Special hypotheses regarding changes in the problem-solving process can be formulated. During the 12 min of the fire simulations, participants might adapt to specific demands of the simulation. Initially, for example, there are no fires, and the participant has time to get familiar with the situation. During that stage, definition of goals might be important: “What do I want to do and achieve?” Toward the middle of the simulation, when several fires are burning, decision-making, and action might be the necessary and dominant stage. Toward the end, a participant might reflect on what he or she has accomplished.

Figure 4 shows the first 20 coded statements at the beginning of the fire simulation, 20 coded statements made in the middle of the simulation, and the last 20 coded statements made at the end of the simulation. Due to space limitations, only the process of the U.S. participant (USA15) is shown. As expected in the hypotheses, initially (codes 1–20) the participant verbalized many goal statements and then moved into planning, decision-making, and action followed by some self-reference statements. In the middle of the simulation (codes 61–80), planning, decision-making, and action was the dominant stage. Some statements referred to problem identification, situation description, and self-references. Toward the end (codes 121–138), however, there is no dominant stage. Every category expressed had a frequency of three or four.

FIGURE 4. Coded thinking-aloud statements from the beginning, middle, and end of the simulation.