Self-Esteem

8 steps to improving your self-esteem, what is the story you tell yourself.

Posted March 27, 2017 | Reviewed by Lybi Ma

- What Is Self-Esteem?

- Find a therapist near me

- Healthy self-esteem can be defined as a realistic, appreciative opinion of oneself.

- Some navigate the world—and relationships—searching for any evidence to validate their self-limiting beliefs.

- Ways to increase feelings of self-worth include the use of affirmations and avoiding comparison with others.

When it comes to your self-worth, only one opinion truly matters—your own. And even that one should be carefully evaluated; we tend to be our own harshest critics.

Glenn R. Schiraldi, Ph.D. , author of The Self-Esteem Workbook , describes healthy self-esteem as a realistic, appreciative opinion of oneself. He writes, “Unconditional human worth assumes that each of us is born with all the capacities needed to live fruitfully, although everyone has a different mix of skills, which are at different levels of development.” He emphasizes that core worth is independent of externals that the marketplace values, such as wealth, education , health, status—or the way one has been treated.

Some navigate the world—and relationships—searching for any bit of evidence to validate their self-limiting beliefs. Much like judge and jury, they constantly put themselves on trial and sometimes sentence themselves to a lifetime of self-criticism.

Following are eight steps you can take to increase your feelings of self-worth.

1. Be mindful .

We can’t change something if we don’t recognize that there is something to change. By simply becoming aware of our negative self-talk , we begin to distance ourselves from the feelings it brings up. This enables us to identify with them less. Without this awareness, we can easily fall into the trap of believing our self-limiting talk, and as meditation teacher Allan Lokos says, “Don’t believe everything you think. Thoughts are just that—thoughts.”

As soon as you find yourself going down the path of self-criticism, gently note what is happening, be curious about it, and remind yourself, “These are thoughts, not facts.”

2. Change the story.

We all have a narrative or a story we’ve created about ourselves that shapes our self-perceptions, upon which our core self-image is based. If we want to change that story, we have to understand where it came from and where we received the messages we tell ourselves. Whose voices are we internalizing?

“Sometimes automatic negative thoughts like ‘you’re fat’ or ‘you’re lazy’ can be repeated in your mind so often that you start to believe they are true,” says Jessica Koblenz, Psy.D . “These thoughts are learned, which means they can be unlearned . You can start with affirmations . What do you wish you believed about yourself? Repeat these phrases to yourself every day."

Thomas Boyce, Ph.D ., supports the use of affirmations. Research conducted by Boyce and his colleagues has demonstrated that “fluency training” in positive affirmations (for example, writing down as many different positive things you can about yourself in a minute) can lessen symptoms of depression as measured by self-report using the Beck Depression Inventory . Larger numbers of written positive statements are correlated with greater improvement. “While they have a bad reputation because of late-night TV,” Boyce says, “positive affirmations can help.”

3. Avoid falling into the compare-and-despair rabbit hole.

“Two key things I emphasize are to practice acceptance and stop comparing yourself to others,” says psychotherapist Kimberly Hershenson, LMSW . “I emphasize that just because someone else appears happy on social media or even in person doesn’t mean they are happy. Comparisons only lead to negative self-talk, which leads to anxiety and stress .” Feelings of low self-worth can negatively affect your mental health as well as other areas in your life, such as work, relationships, and physical health.

4. Channel your inner rock star.

Albert Einstein said, “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” We all have our strengths and weaknesses. Someone may be a brilliant musician, but a dreadful cook. Neither quality defines their core worth. Recognize what your strengths are and the feelings of confidence they engender, especially in times of doubt. It’s easy to make generalizations when you “mess up” or “fail” at something, but reminding yourself of the ways you rock offers a more realistic perspective of yourself.

Psychotherapist and certified sex therapist Kristie Overstreet, LPCC, CST, CAP , suggests asking yourself, “Was there a time in your life where you had better self-esteem? What were you doing at that stage of your life?” If it’s difficult for you to identify your unique gifts, ask a friend to point them out to you. Sometimes it’s easier for others to see the best in us than it is for us to see it in ourselves.

5. Exercise.

Many studies have shown a correlation between exercise and higher self-esteem, as well as improved mental health. “Exercising creates empowerment both physical and mental,” says Debbie Mandel, author of Addicted to Stress , “especially weight lifting where you can calibrate the accomplishments. Exercise organizes your day around self-care.” She suggests dropping a task daily from your endless to-do list for the sole purpose of relaxation or doing something fun, and seeing how that feels. Other forms of self-care, such as proper nutrition and sufficient sleep , have also been shown to have positive effects on one’s self-perception.

6. Do unto others.

Hershenson suggests volunteering to help those who may be less fortunate. “Being of service to others helps take you out of your head. When you are able to help someone else, it makes you less focused on your own issues.”

David Simonsen, Ph.D., LMFT , agrees:

“What I find is that the more someone does something in their life that they can be proud of, the easier it is for them to recognize their worth. Doing things that one can respect about themselves is the one key that I have found that works to raise one’s worth. It is something tangible. Helping at a homeless shelter, animal shelter, giving of time at a big brother or sister organization. These are things that mean something and give value to not only oneself, but to someone else as well.”

There is much truth to the fact that what we put out there into the world tends to boomerang back to us. To test this out, spend a day intentionally putting out positive thoughts and behaviors toward those with whom you come into contact. As you go about your day, be mindful of what comes back to you, and also notice if your mood improves.

7. Forgive.

Is there someone in your life you haven’t forgiven? An ex-partner? A family member? Yourself? By holding on to feelings of bitterness or resentment, we keep ourselves stuck in a cycle of negativity. If we haven’t forgiven ourselves, shame will keep us in this same loop.

“Forgiving self and others has been found to improve self-esteem,” says Schiraldi, “perhaps because it connects us with our innately loving nature and promotes an acceptance of people, despite our flaws.” He refers to the Buddhist meditation on forgiveness , which can be practiced at any time: " If I have hurt or harmed anyone, knowingly or unknowingly, I ask forgiveness. If anyone has hurt or harmed me, knowingly or unknowingly, I forgive them. For the ways I have hurt myself, knowingly or unknowingly, I offer forgiveness."

8. Remember that you are not your circumstances.

Finally, learning to differentiate between your circumstances and who you are is key to self-worth. “Recognizing inner worth, and loving one’s imperfect self, provide the secure foundation for growth,” says Schiraldi. “With that security, one is free to grow with enjoyment, not fear of failure—because failure doesn’t change core worth.”

We are all born with infinite potential and equal worth as human beings. That we are anything less is a false belief that we have learned over time. Therefore, with hard work and self-compassion, self-destructive thoughts and beliefs can be unlearned. Taking the steps outlined above is a start in the effort to increase self-worth, or as Schiraldi says, to “ recognize self-worth. It already exists in each person.”

LinkedIn image: BearFotos/Shutterstock

Allison Abrams, LCSW-R , is a licensed psychotherapist in NYC, as well as a writer and advocate for mental health awareness and destigmatization.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

5 ways to build lasting self-esteem

Share this idea.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Everyone is in favor of high self-esteem — but cultivating it can be surprisingly tough. Psychologist Guy Winch explains why — and describes smart ways we can help build ourselves up.

Many of us recognize the value of improving our feelings of self-worth. When our self-esteem is higher, we not only feel better about ourselves, we are more resilient as well. Brain scan studies demonstrate that when our self-esteem is higher, we are likely to experience common emotional wounds such as rejection and failure as less painful, and bounce back from them more quickly. When our self-esteem is higher, we are also less vulnerable to anxiety ; we release less cortisol into our bloodstream when under stress, and it is less likely to linger in our system.

But as wonderful as it is to have higher self-esteem, it turns out that improving it is no easy task. Despite the endless array of articles, programs and products promising to enhance our self-esteem, the reality is that many of them do not work and some are even likely to make us feel worse .

Part of the problem is that our self-esteem is rather unstable to begin with, as it can fluctuate daily, if not hourly. Further complicating matters, our self-esteem comprises both our global feelings about ourselves as well as how we feel about ourselves in the specific domains of our lives (e.g., as a father, a nurse, an athlete, etc.). The more meaningful a specific domain of self-esteem, the greater the impact it has on our global self-esteem. Having someone wince when they taste the not-so-delicious dinner you prepared will hurt a chef’s self-esteem much more than someone for whom cooking is not a significant aspect of their identity.

Lastly, having high self-esteem is indeed a good thing, but only in moderation. Very high self-esteem — like that of narcissists — is often quite brittle. Such people might feel great about themselves much of the time but they also tend to be extremely vulnerable to criticism and negative feedback and respond to it in ways that stunts their psychological self-growth .

That said, it is certainly possible to improve our self-esteem if we go about it the right way. Here are five ways to nourish your self-esteem when it is low:

1. Use positive affirmations correctly

Positive affirmations such as “I am going to be a great success!” are extremely popular, but they have one critical problem — they tend to make people with low self-worth feel worse about themselves. Why? Because when our self-esteem is low, such declarations are simply too contrary to our existing beliefs . Ironically, positive affirmations do work for one subset of people — those whose self-esteem is already high. For affirmations to work when your self-esteem is lagging, tweak them to make them more believable. For example, change “I’m going to be a great success!” to “I’m going to persevere until I succeed!”

2. Identify your competencies and develop them

Self-esteem is built by demonstrating real ability and achievement in areas of our lives that matter to us. If you pride yourself on being a good cook, throw more dinner parties. If you’re a good runner, sign up for races and train for them. In short, figure out your core competencies and find opportunities and careers that accentuate them.

3. Learn to accept compliments

One of the trickiest aspects of improving self-esteem is that when we feel bad about ourselves we tend to be more resistant to compliments — even though that is when we most need them. So, set yourself the goal to tolerate compliments when you receive them, even if they make you uncomfortable (and they will). The best way to avoid the reflexive reactions of batting away compliments is to prepare simple set responses and train yourself to use them automatically whenever you get good feedback (e.g., “Thank you” or “How kind of you to say”). In time, the impulse to deny or rebuff compliments will fade — which will also be a nice indication your self-esteem is getting stronger.

4. Eliminate self-criticism and introduce self-compassion

Unfortunately, when our self-esteem is low, we are likely to damage it even further by being self-critical. Since our goal is to enhance our self-esteem, we need to substitute self-criticism (which is almost always entirely useless, even if it feels compelling) with self-compassion . Specifically, whenever your self-critical inner monologue kicks in, ask yourself what you would say to a dear friend if they were in your situation (we tend to be much more compassionate to friends than we are to ourselves) and direct those comments to yourself. Doing so will avoid damaging your self-esteem further with critical thoughts, and help build it up instead.

5. Affirm your real worth

The following exercise has been demonstrated to help revive your self-esteem after it sustained a blow: Make a list of qualities you have that are meaningful in the specific context. For example, if you got rejected by your date, list qualities that make you a good relationship prospect (for example, being loyal or emotionally available); if you failed to get a work promotion, list qualities that make you a valuable employee (you have a strong work ethic or are responsible). Then choose one of the items on your list and write a brief essay (one to two paragraphs) about why the quality is valuable and likely to be appreciated by other people in the future. Do the exercise every day for a week or whenever you need a self-esteem boost.

The bottom line is improving self-esteem requires a bit of work, as it involves developing and maintaining healthier emotional habits but doing so, and especially doing so correctly, will provide a great emotional and psychological return on your investment.

About the author

Guy Winch is a licensed psychologist who is a leading advocate for integrating the science of emotional health into our daily lives. His three TED Talks have been viewed over 20 million times, and his science-based self-help books have been translated into 26 languages. He also writes the Squeaky Wheel blog for PsychologyToday.com and has a private practice in New York City.

- mental health

- self-esteem

TED Talk of the Day

How to make radical climate action the new normal

6 ways to give that aren't about money

A smart way to handle anxiety -- courtesy of soccer great Lionel Messi

How do top athletes get into the zone? By getting uncomfortable

6 things people do around the world to slow down

Creating a contract -- yes, a contract! -- could help you get what you want from your relationship

Could your life story use an update? Here’s how to do it

6 tips to help you be a better human now

How to have better conversations on social media (really!)

Let’s stop calling them “soft skills” -- and call them “real skills” instead

3 strategies for effective leadership, from a former astronaut

There’s a know-it-all at every job — here’s how to deal

Why rejection hurts so much -- and what to do about it

We all know people who just can't apologize -- well, here's why

7 ways to practice emotional first aid

How to cultivate a sense of unconditional self-worth

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Adult health

Self-esteem: Take steps to feel better about yourself

Harness the power of your thoughts and beliefs to raise your self-esteem. Start with these steps.

Low self-esteem can affect nearly every aspect of life. It can impact your relationships, job and health. But you can boost your self-esteem by taking cues from mental health counseling.

Consider these steps, based on cognitive behavioral therapy.

1. Recognize situations that affect self-esteem

Think about the situations that seem to deflate your self-esteem. Common triggers might include:

- A work or school presentation

- A crisis at work or home

- A challenge with a spouse, loved one, co-worker or other close contact

- A change in roles or life events, such as a job loss or a child leaving home

2. Become aware of thoughts and beliefs

Once you've learned which situations affect your self-esteem, notice your thoughts about them. This includes what you tell yourself (self-talk) and how you view the situations.

Your thoughts and beliefs might be positive, negative or neutral. They might be rational, based on reason or facts. Or they may be irrational, based on false ideas.

Ask yourself if these beliefs are true. Would you say them to a friend? If you wouldn't say them to someone else, don't say them to yourself.

3. Challenge negative thinking

Your initial thoughts might not be the only way to view a situation. Ask yourself whether your view is in line with facts and logic. Or is there another explanation?

Be aware that it can be hard to see flaws in your logic. Long-held thoughts and beliefs can feel factual even if they're opinions.

Also notice if you're having these thought patterns that erode self-esteem:

- All-or-nothing thinking. This involves seeing things as either all good or all bad. For example, you may think, "If I don't succeed in this task, I'm a total failure."

- Mental filtering. This means you focus and dwell on the negatives. It can distort your view of a person or situation. For example, "I made a mistake on that report and now everyone will realize I'm not up to the job."

- Converting positives into negatives. This may involve rejecting your achievements and other positive experiences by insisting that they don't count. For example, "I only did well on that test because it was so easy."

- Jumping to negative conclusions. You may tend to reach a negative conclusion with little or no evidence. For example, "My friend hasn't replied to my text, so I must have done something to make her angry."

- Mistaking feelings for facts. You may confuse feelings or beliefs with facts. For example, "I feel like a failure, so I must be a failure."

- Negative self-talk. You undervalue yourself. You may put yourself down or joke about your faults. For example, you may say, "I don't deserve anything better."

4. Adjust your thoughts and beliefs

Now replace negative or untrue thoughts with positive, accurate thoughts. Try these strategies:

- Use hopeful statements. Be kind and encouraging to yourself. Instead of thinking a situation won't go well, focus on the positive. Tell yourself, "Even though it's tough, I can handle this."

- Forgive yourself. Everyone makes mistakes. But mistakes aren't permanent reflections on you as a person. They're moments in time. Tell yourself, "I made a mistake, but that doesn't make me a bad person."

- Avoid 'should' and 'must' statements. If you find that your thoughts are full of these words, you might be putting too many demands on yourself. Try to remove these words from your thoughts. It may lead to a healthier view of what to expect from yourself.

- Focus on the positive. Think about the parts of your life that work well. Remember the skills you've used to cope with challenges.

- Consider what you've learned. If it was a negative experience, what changes can you make next time to create a more positive outcome?

- Relabel upsetting thoughts. Think of negative thoughts as signals to try new, healthy patterns. Ask yourself, "What can I think and do to make this less stressful?"

- Encourage yourself. Give yourself credit for making positive changes. For example, "My presentation might not have been perfect, but my colleagues asked questions and remained engaged. That means I met my goal."

You might also try these steps, based on acceptance and commitment therapy.

1. Spot troubling conditions or situations

Again, think about the conditions or situations that seem to deflate your self-esteem. Then pay attention to your thoughts about them.

2. Step back from your thoughts

Repeat your negative thoughts many times. The goal is to take a step back from automatic thoughts and beliefs and observe them. Instead of trying to change your thoughts, distance yourself from them. Realize that they are nothing more than words.

3. Accept your thoughts

Instead of resisting or being overwhelmed by negative thoughts or feelings, accept them. You don't have to like them. Just allow yourself to feel them.

Negative thoughts don't need to be controlled, changed or acted upon. Aim to lessen their power on your behavior.

These steps might seem awkward at first. But they'll get easier with practice. Recognizing the thoughts and beliefs that affect low self-esteem allows you to change the way you think about them. This will help you accept your value as a person. As your self-esteem increases, your confidence and sense of well-being are likely to soar.

In addition to these suggestions, remember that you're worth special care. Be sure to:

- Take care of yourself. Follow good health guidelines. Try to exercise at least 30 minutes a day most days of the week. Eat lots of fruits and vegetables. Limit sweets, junk food and saturated fats.

- Do things you enjoy. Start by making a list of things you like to do. Try to do something from that list every day.

- Spend time with people who make you happy. Don't waste time on people who don't treat you well.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Orth U, et al. Is high self-esteem beneficial? Revisiting a classic question. American Psychologist. 2022; doi:10.1037/amp0000922.

- Levenson JL, ed. Psychotherapy. In: The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine and Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019. https://psychiatryonline.org. Accessed April 27, 2022.

- Kliegman RM, et al. Psychotherapy and psychiatric hospitalization. In: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 27, 2022.

- Fusar-Poli P, et al. What is good mental health? A scoping review. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 202; doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2019.12.105.

- Van de Graaf DL, et al. Online acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) interventions for chronic pain: A systematic literature review. Internet Interventions. 2021; doi:10.1016/j.invent.2021.100465.

- Bourne EJ. The Anxiety and Phobia Workbook. 7th ed. New Harbinger Publications; 2020.

- Ebert MH, et al., eds. Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral interventions. In: Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Psychiatry. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2019. https://www.accessmedicine.mhmedical.com. Accessed May 4, 2022.

- Self-esteem self-help guide. NHS inform. https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/mental-health/mental-health-self-help-guides/self-esteem-self-help-guide. Accessed May 4, 2022.

- A very happy brain

- Anger management: 10 tips to tame your temper

- Are you thinking about suicide? How to stay safe and find treatment

- COVID-19 and your mental health

- Friendships

- Mental health

- Passive-aggressive behavior

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Self esteem - Take steps to feel better about yourself

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Essay on Self Esteem

Students are often asked to write an essay on Self Esteem in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Self Esteem

Understanding self-esteem.

Self-esteem is the opinion we have about ourselves. It’s about how much we value and respect ourselves. High self-esteem means you think highly of yourself, while low self-esteem means you don’t.

Importance of Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is important because it heavily influences our choices and decisions. It allows us to live life to our potential. High self-esteem leads to confidence, happiness, fulfillment, and achievement.

Building Self-Esteem

Building self-esteem requires positive self-talk, self-acceptance, and self-love. It’s about focusing on your strengths, forgiving your mistakes, and celebrating your achievements.

250 Words Essay on Self Esteem

Introduction.

Self-esteem, a fundamental concept in psychology, refers to an individual’s overall subjective emotional evaluation of their own worth. It encompasses beliefs about oneself and emotional states, such as triumph, despair, pride, and shame. It is a critical aspect of personal identity, shaping our perception of the world and our place within it.

The Dual Facet of Self-Esteem

Self-esteem can be divided into two types: high and low. High self-esteem is characterized by a positive self-image and confidence, while low self-esteem is marked by self-doubt and criticism. Both types significantly influence our mental health, relationships, and life outcomes.

Impact of Self-Esteem

High self-esteem can lead to positive outcomes. It encourages risk-taking, resilience, and optimism, fostering success in various life domains. Conversely, low self-esteem can result in fear of failure, social anxiety, and susceptibility to mental health issues like depression. Thus, it’s crucial to nurture self-esteem for psychological well-being.

Building self-esteem involves recognizing one’s strengths and weaknesses and accepting them. It requires self-compassion and challenging negative self-perceptions. Positive affirmations, setting and achieving goals, and maintaining healthy relationships can all contribute to enhancing self-esteem.

In conclusion, self-esteem is a complex, multifaceted construct that significantly influences our lives. It is not static and can be improved with conscious effort. Understanding and nurturing our self-esteem is vital for achieving personal growth and leading a fulfilling life.

500 Words Essay on Self Esteem

Self-esteem, a fundamental aspect of psychological health, is the overall subjective emotional evaluation of one’s self-worth. It is a judgment of oneself as well as an attitude toward the self. The importance of self-esteem lies in the fact that it concerns our perceptions and beliefs about ourselves, which can shape our experiences and actions.

The Two Types of Self-esteem

Self-esteem can be classified into two types: high and low. High self-esteem indicates a highly favorable impression of oneself, whereas low self-esteem reflects a negative view. People with high self-esteem generally feel good about themselves and value their worth, while those with low self-esteem usually harbor negative feelings about themselves, often leading to feelings of inadequacy, incompetence, and unlovability.

Factors Influencing Self-esteem

Self-esteem is shaped by various factors throughout our lives, such as the environment, experiences, relationships, and achievements. Positive reinforcement, success, and supportive relationships often help to foster high self-esteem, while negative feedback, failure, and toxic relationships can contribute to low self-esteem. However, it’s important to note that self-esteem is not a fixed attribute; it can change over time and can be improved through cognitive and behavioral interventions.

Impact of Self-esteem on Life

Self-esteem significantly impacts individuals’ mental health, relationships, and overall well-being. High self-esteem can lead to positive outcomes, such as better stress management, resilience, and life satisfaction. On the other hand, low self-esteem is associated with mental health issues like depression and anxiety. It can also lead to poor academic and job performance, problematic relationships, and increased vulnerability to drug and alcohol abuse.

Improving Self-esteem

Improving self-esteem requires a multifaceted approach. Cognitive-behavioral therapies can help individuals challenge their negative beliefs about themselves and develop healthier thought patterns. Regular physical activity, healthy eating, and adequate sleep can also boost self-esteem by improving physical health. Furthermore, positive social interactions and relationships can enhance self-esteem by providing emotional support and validation. Lastly, self-compassion and self-care practices can foster a more positive self-image and promote higher self-esteem.

In conclusion, self-esteem is a critical component of our psychological well-being, influencing our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It is shaped by various factors and can significantly impact our lives. However, it’s not a fixed attribute, and with the right strategies and support, individuals can improve their self-esteem, leading to better mental health, relationships, and overall quality of life. Therefore, understanding and fostering self-esteem is essential for personal growth and development.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Self Defence

- Essay on Self Control

- Essay on Secret of Happiness

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

What is Self-Worth & How Do We Build it? (Incl. Worksheets)

There’s self-esteem, self-compassion, self-acceptance, self-respect, self-confidence, self-love, self-care, and so on.

There are so many words to describe how we feel about ourselves, how we think about ourselves, and how we act toward ourselves. It’s understandable if they all start to blend together for you; however, they are indeed different concepts with unique meanings, findings, and purposes.

Read on to learn more about what may be the most vital “self-” concept of them all: self-worth.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Self-Compassion Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will not only help you show more compassion and kindness to yourself but will also give you the tools to help your clients, students or employees improve their self-compassion and realize their worth.

This Article Contains:

What is the meaning of self-worth and self-value, the psychology of self-worth.

- What Is Self-Worth Theory?

What Determines Self-Worth?

3 examples of healthy self-worth, how to find self-worth and value yourself more, the importance of self-worth in relationships, the risks of tying your self-worth to your job, the self-worth scale, 5 activities and exercises for developing self-worth, 2 worksheets that help increase self-worth, meditations to boost self-worth, recommended books on self-worth, must-watch ted talks and youtube videos, 12 quotes on self-worth, a take-home message.

Self-worth and self-value are two related terms that are often used interchangeably. Having a sense of self-worth means that you value yourself, and having a sense of self-value means that you are worthy. The differences between the two are minimal enough that both terms can be used to describe the same general concept.

However, we’ll provide both definitions so you can see where they differ.

Self-worth is defined by Merriam-Webster as:

“a feeling that you are a good person who deserves to be treated with respect”.

On the other hand, self-value is “more behavioral than emotional, more about how you act toward what you value, including yourself, than how you feel about yourself compared to others” (Stosny, 2014).

Self-Worth versus Self-Esteem

Similarly, there is not a huge difference between self-worth and self-esteem , especially for those who are not professionals in the field of psychology. In fact, the first definition of self-worth on the Merriam-Webster dictionary website is simply “self-esteem.”

Similarly, the World Book Dictionary definition of self-esteem is “thinking well of oneself; self-respect,” while self-worth is defined as “a favorable estimate or opinion of oneself; self-esteem” (Bogee, Jr., 1998).

Clearly, many of these terms are used to talk about the same ideas, but for those deeply immersed in these concepts, there is a slight difference. Dr. Christina Hibbert explains this:

“Self-esteem is what we think and feel and believe about ourselves. Self-worth is recognizing ‘I am greater than all of those things.’ It is a deep knowing that I am of value, that I am loveable, necessary to this life, and of incomprehensible worth.” (2013).

Self-Worth versus Self-Confidence

In the same vein, there are subtle but significant differences between self-worth and self-confidence.

Self-confidence is not an overall evaluation of yourself, but a feeling of confidence and competence in more specific areas. For example, you could have a high amount of self-worth but low self-confidence when it comes to extreme sports, certain subjects in school, or your ability to speak a new language (Roberts, 2012).

It’s not necessary to have a high sense of self-confidence in every area of your life; there are naturally some things that you will simply not be very good at, and other areas in which you will excel. The important thing is to have self-confidence in the activities in your life that matter to you and a high sense of self-worth overall.

We explore this further in The Science of Self-Acceptance Masterclass© .

Download 3 Free Self-Compassion Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you to help others create a kinder and more nurturing relationship with themselves.

Download 3 Free Self-Compassion Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

What Is the Self-Worth Theory?

The self-worth theory posits that an individual’s main priority in life is to find self-acceptance and that self-acceptance is often found through achievement (Covington & Beery, 1976). In turn, achievement is often found through competition with others.

Thus, the logical conclusion is that competing with others can help us feel like we have impressive achievements under our belt, which then makes us feel proud of ourselves and enhances our acceptance of ourselves.

The theory holds that there are four main elements of the self-worth model:

- Performance;

- Self-worth.

The first three interact with each other to determine one’s level of self-worth. One’s ability and effort predictably have a big impact on performance, and all three contribute to one’s feeling of worth and value.

While this theory represents a good understanding of self-worth as we tend to experience it, it is unfortunate that we place so much emphasis on our achievements. Aside from competing and “winning” against others, there are many factors that can contribute to our sense of self-worth.

However, people commonly use other yardsticks to measure their self-worth. Here are five of the top factors that people use to measure and compare their own self-worth to the worth of others:

- Appearance—whether measured by the number on the scale, the size of clothing worn, or the kind of attention received by others;

- Net worth—this can mean income, material possessions, financial assets, or all of the above;

- Who you know/your social circle—some people judge their own value and the value of others by their status and what important and influential people they know;

- What you do/your career—we often judge others by what they do; for example, a stockbroker is often considered more successful and valuable than a janitor or a teacher;

- What you achieve—as noted earlier, we frequently use achievements to determine someone’s worth (whether it’s our own worth or someone else’s), such as success in business, scores on the SATs, or placement in a marathon or other athletic challenge (Morin, 2017).

Author Stephanie Jade Wong (n.d.) is on a mission to correct misunderstandings and misperceptions about self-worth. Instead of listing all the factors that go into self-worth, she outlines what does not determine your self-worth (or, what should not determine your self-worth):

- Your to-do list: Achieving goals is great and it feels wonderful to cross off things on your to-do list, but it doesn’t have a direct relationship with your worth as a human;

- Your job: It doesn’t matter what you do. What matters is that you do it well and that it fulfills you;

- Your social media following: It also doesn’t matter how many people think you are worthy of a follow or a retweet. It can be enlightening and healthy to consider the perspectives of others, but their opinions have no impact on our innate value;

- Your age: You aren’t too young or too old for anything. Your age is simply a number and does not factor into your value as a human being;

- Other people: As noted above, it doesn’t matter what other people think or what other people have done or accomplished. Your personal satisfaction and fulfillment are much more important than what others are thinking, saying, or doing;

- How far you can run: Your mile run time is one of the least important factors for your self-worth (or for anything else, for that matter). If you enjoy running and feel fulfilled by improving your time, good for you! If not, good for you! Your ability to run does not determine your self-worth;

- Your grades: We all have different strengths and weaknesses, and some of us are simply not cut out for class. This has no bearing on our value as people, and a straight-A student is just as valuable and worthy as a straight-F student or a dropout;

- The number of friends you have: Your value as a human has absolutely nothing to do with how many friends or connections you have. The quality of your relationships is what’s really important;

- Your relationship status: Whether flying solo, casually dating, or in a committed relationship, your value is exactly the same—your relationship status doesn’t alter your worth;

- The money (or lack thereof) in the bank: If you have enough money to physically survive (which can, in fact, be $0), then you have already achieved the maximal amount of “worth” you can get from money (hint: it’s 0!);

- Your likes: It doesn’t matter if you have “good taste” or not, if your friends and acquaintances think you’re sophisticated, or if you have an eye for the finer things. Your worth is the same either way.

- Anything or anyone but yourself: Here we get to the heart of the matter—you are the only one who determines your self-worth. If you believe you are worthy and valuable, you are worthy and valuable. Even if you don’t believe you are worthy and valuable, guess what—you still are worthy and valuable!

“ If I succeed at this, I will feel more valuable as a person. ”

Have you ever had a similar thought? You are certainly not alone. While objectively, your worth is not conditional on anything, most of us constantly evaluate our worth as human beings.

Blascovich and Tomaka (1991) describe self-esteem as the extent to which an individual evaluates themselves favorably. Consequently, the core process underlying self-esteem is self-evaluation, and people use many standards and domains to determine their worthiness (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001).

Domains represent the areas where people believe success means that they are wonderful or worthwhile, and failure means that they are worthless (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001).

For example, the self-worth of person A may be greatly determined by academic performance, while the self-worth of person B may be determined mainly by appearance.

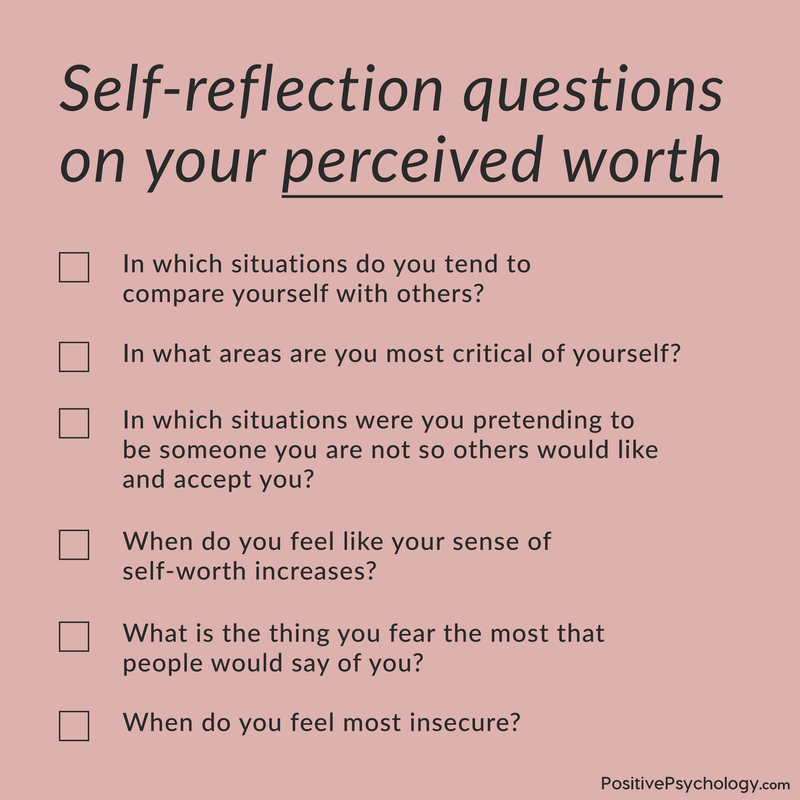

Noticing the domains your use as a frame of reference to determine your self-worth is the first step toward developing more unconditional self-acceptance. The self-reflection questions shared below explore created conditions used to determine ‘worthiness’ and later lead beyond these conditions.

Note that there is a difference between evaluating actions and evaluating personal worth. We can learn from our mistakes and grow as individuals by assessing our efforts. However, by evaluating our personal worth, we can threaten our wellbeing.

You might be thinking, “Okay, I know what does and doesn’t (and shouldn’t) determine self-worth, but what does healthy self-worth really look like?”

Given what we know about the determinants of self-worth, let’s read through a few examples.

Bill is not a great student. He gets mostly Bs and Cs, even when he spends a great deal of time studying. He didn’t get a great score on his SATs, and he’s an average reader, a struggling writer, and nobody’s idea of a mathematician.

Even though Bill wishes he had better grades, he still feels pretty good about himself. He knows that grades aren’t everything and that he’s just as valuable a person as his straight-A friends. Bill has a high sense of self-worth and a realistic view of himself and his abilities.

Next, let’s consider Amy. Amy has a wide variety of interests, including marathons, attending book club, playing weekly trivia with her friends, and meeting new people.

Amy’s not particularly good at running and has never placed in a marathon. She’s a slow reader and frequently misses the symbolism and themes that her fellow book club members pick up on. She only answers about 10% of the trivia questions correctly and leans on her friends’ knowledge quite often. Finally, she loves to talk to new people but sometimes she gets blown off and ignored.

Despite all of this, she still believes that she is worthy and valuable. She knows that her worth as a human is not dependent on her ability to run, read, play trivia, or make new friends. Whether she is great, terrible, or somewhere in between at each of her vast range of chosen activities, she knows she is still worthy of happiness, fulfillment, and love.

Finally, consider the case of Marcus. Marcus is an excellent salesman and frequently outsells most of the other people at his company, but one coworker seems to always be just a bit ahead of him. He is also an avid squash player and frequently competes in tournaments. Sometimes he gets first or second place, but usually he does not place at all.

Even though he is not the best at his job or at his favorite hobby, Marcus still feels that he is valuable. He thinks he is smart, talented, and successful, even though he’s not the smartest, most talented, or most successful, and he’s okay with that.

Bill, Amy, and Marcus all have healthy levels of self-worth. They have varying levels of abilities and talents, and they get a wide range of results from their efforts, but they all understand that what they do is not who they are. No matter whether they win awards or garner accolades for their performance or not, they still have the same high opinion of their value as a person.

There are things you can do to boost your sense of self-worth and ensure that you value yourself like you ought to be valued—as a full, complete, and wonderful human being that is deserving of love and respect, no matter what.

How to build self-worth in adolescents

As with most lifelong traits, it’s best to start early. If you know any adolescents, be sure to encourage them to understand and accept their own self-worth. Reinforce their value as a being rather than a “doing,” as some say—in other words, make sure they know that they are valuable for who they are, not what they do.

If you need some more specific ideas on how to boost an adolescent’s self-worth, check out the suggestions below.

Researchers at Michigan State University recommend two main strategies:

- Provide unconditional love, respect, and positive regard;

- Give adolescents opportunities to experience success (Clark-Jones, 2012).

Showing a teen unconditional love (if you’re a parent, family member, or very close friend) or unconditional respect and positive regard (if you’re a teacher, mentor, etc.) is the best way to teach him self-worth.

If you show a teenager that you love and appreciate her for exactly who and what she is, she will learn that it’s okay to love herself for exactly who and what she is. If you demonstrate that she doesn’t need to achieve anything to earn your love and respect, she’ll be much less likely to put unnecessary parameters on her own self-love and self-respect.

Further, one way in which we gain a healthy sense of self-worth is through early and frequent experiences of success. Successful experiences boost our sense of competency and mastery and make us feel just plain good about ourselves.

Successful experiences also open the door for taking healthy risks and the success that often follows. Don’t just tell a teen that she is worthy and valuable, help her believe it by giving her every opportunity to succeed.

Just be sure that these opportunities are truly opportunities for her to succeed on her own—a helping hand is fine, but we need to figure out how to do some things on our own to build a healthy sense of self-worth (Clark-Jones, 2012).

How to increase self-worth and self-value in adults

It’s a bit trickier to increase self-worth and self-value in adults, but it’s certainly not a lost cause. Check out the two tips below to learn how to go about it.

First, take a look back at the list of what does not determine self-worth. Remind yourself that your bank account, job title, attractiveness, and social media following have nothing to do with how valuable or worthy a person you are.

It’s easy to get caught up in chasing money, status, and popularity—especially when these things are highly valued by those around us and by society in general—but make an effort to take a step back and think about what truly matters when determining people’s worth: their kindness, compassion, empathy, respect for others, and how well they treat those around them.

Second, work on identifying, challenging, and externalizing your critical inner voice. We all have an inner critic that loves to nitpick and point out our flaws (Firestone, 2014). It’s natural to let this inner critic get the best of us sometimes, but if we let her win too often she starts to think that she’s right!

Whenever you notice your inner critic start to fire up with the criticisms, make her pause for a moment. Ask yourself whether she has any basis in fact, whether she’s being kind or not, and whether what she’s telling you is something you need to know. If none of those things are true, feel free to tell her to see herself out!

Challenge her on the things she whispers in your ear and remind her that no matter what you do or don’t do, you are worthy and valuable all the same.

For more specific activities and ideas, see the exercises, activities, and worksheets we cover later in this piece.

It’s an understandable tendency to let someone else’s love for you encourage you to feel better about yourself. However, you should work on feeling good about yourself whether you are in a relationship or not.

The love of another person does not define you, nor does it define your value as a person. Whether you are single, casually seeing people, building a solid relationship with someone, or celebrating your 30th wedding anniversary with your spouse, you are worthy of love and respect, and you should make time to practice self-acceptance and self-compassion.

This is true for people of any relationship status, but it may be especially important for those in long-term relationships.

Don’t make the mistake of thinking that your partner’s love is what makes you worthy of love. If anything ever happens to your partner or to your relationship, you don’t want to be forced to build up your sense of worth from scratch. It can make breakups and grief much harder than they need to be.

Although this facet of the issue might be enough to encourage you to work on your self-worth, there’s another reason it’s important: Having a healthy sense of self-worth will actually make your current relationship better too.

When you learn to love yourself, you become better able to love someone else. People with high self-respect tend to have more satisfying, loving, and stable relationships than those who do not, precisely because they know that they need to first find their worth, esteem, and happiness within themselves.

Two people who are lit with self-worth and happiness from within make are much brighter than two people who are trying to absorb light from each other (Grande, 2018).

Similar to the dangers of anchoring your self-worth to someone else, there are big risks in tying your self-worth to your job. Like a significant other, jobs can come and go—sometimes without warning.

You can be let go, laid off, transitioned, dehired, dismissed, downsized, redirected, released, selectively separated, terminated, replaced, asked to resign, or just plain fired. You could also be transferred, promoted, demoted, or given new duties and responsibilities that no longer mesh with the sense of self-worth your previous duties and responsibilities gave you.

You could also quit, take a new job, take some time off, or retire—all things that can be wonderful life transitions, but that can be unnecessarily difficult if you base too much of your self-worth on your job.

As noted earlier, your job is one of the things that don’t define you or your worth. There’s nothing wrong with being proud of what you do, finding joy or fulfillment in it, or letting it shape who you are; the danger is in letting it define your entire sense of self.

We are all so much more than a job. Believing that we are nothing more than a job is detrimental to our wellbeing and can be disastrous in times of crisis.

If so, you’re in luck. There is a scale that is perfectly suited for this curiosity.

Also known as the Contingencies of Self-Worth Scale, this scale was developed by researchers Crocker, Luhtanen, Cooper, and Bouvrette in 2003. It consists of 35 items that measure self-worth in seven different domains. These seven domains, with an example item from each domain, are:

- Approval from others (i.e., I don’t care if other people have a negative opinion of me);

- Physical appearance (i.e., my self-esteem is influenced by how attractive I think my face or facial features are);

- Outdoing others in competition (i.e., my self-worth is affected by how well I do when I am competing with others);

- Academic competence (i.e., I feel bad about myself whenever my academic performance is lacking);

- Family love and support (i.e., my self-worth is not influenced by the quality of my relationships with my family members);

- Being a virtuous or moral person (i.e., my self-esteem depends on whether or not I follow my moral/ethical principles);

- God’s love (i.e., my self-esteem would suffer if I didn’t have God’s love).

Each item is rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Once you have rated each item, sum the answers to the five items for each domain and divide the total by 5 for the sub-scale score.

To learn more about this scale or use it to determine your own self-worth, click here .

According to author and self-growth guru Adam Sicinski, there are five vital exercises for developing and maintaining self-worth. He lays them out in five stages, but there’s no need to keep them in strict order; it’s fine to move back and forth or revisit stages.

1. Increase your self-understanding

An important activity on the road to self-worth is to build self-understanding. You need to learn who you are and what you want before you can decide you are a worthy human being.

Sicinski recommends this simple thought experiment to work on increasing your understanding of yourself:

- Imagine that everything you have is suddenly taken away from you (i.e., possessions, relationships, friendships, status, job/career, accomplishments and achievements, etc.);

- Ask yourself the following questions: a. What if everything I have was suddenly taken away from me? b. What if all I had left was just myself? c. How would that make me feel? d. What would I actually have that would be of value?

- Think about your answers to these questions and see if you can come to this conclusion: “No matter what happens externally and no matter what’s taken away from me, I’m not affected internally”;

- Next, get to know yourself on a deeper level with these questions: a. Who I am? I am . . . I am not . . . b. How am I? c. How am I in the world? d. How do others see me? e. How do others speak about me? f. What key life moments define who I am today? g. What brings me the most passion, fulfillment, and joy?

- Once you have a good understanding of who you are and what fulfills and satisfies you, it’s time to look at what isn’t so great or easy about being you. Ask yourself these questions: a. Where do I struggle most? b. Where do I need to improve? c. What fears often hold me back? d. What habitual emotions hurt me? e. What mistakes do I tend to make? f. Where do I tend to consistently let myself down?

- Finally, take a moment to look at the flipside; ask yourself: a. What abilities do I have? b. What am I really good at?

Spend some time on each step, but especially on the steps that remind you of your worth and your value as a person (e.g., the strengths step).

2. Boost your self-acceptance

Once you have a better idea of who you are, the next step is to enhance your acceptance of yourself.

Start by forgiving yourself for anything you noted in item 5 above. Think of any struggles, needs for improvement, mistakes, and bad habits you have, and commit to forgiving yourself and accepting yourself without judgment or excuses.

Think about everything you learned about yourself in the first exercise and repeat these statements:

- I accept the good, the bad and the ugly;

- I fully accept every part of myself including my flaws, fears, behaviors, and qualities I might not be too proud of;

- This is how I am, and I am at peace with that

3. Enhance your self-love

Now that you have worked on accepting yourself for who you are, you can begin to build love and care for yourself. Make it a goal to extend yourself kindness, tolerance, generosity, and compassion .

To boost self-love, start paying attention to the tone you use with yourself. Commit to being more positive and uplifting when talking to yourself.

If you’re not sure how to get started, think (or say aloud) these simple statements:

- I feel valued and special;

- I love myself wholeheartedly;

- I am a worthy and capable person (Sicinski, n.d.).

4. Recognize your self-worth

Once you understand, accept, and love yourself, you will reach a point where you no longer depend on people, accomplishments, or other external factors for your self-worth.

At this point, the best thing you can do is recognize your worth and appreciate yourself for the work you’ve done to get here, as well as continuing to maintain your self-understanding, self-acceptance, self-love, and self-worth.

To recognize your self-worth, remind yourself that:

- You no longer need to please other people;

- No matter what people do or say, and regardless of what happens outside of you, you alone control how you feel about yourself;

- You have the power to respond to events and circumstances based on your internal sources, resources, and resourcefulness, which are the reflection of your true value;

- Your value comes from inside, from an internal measure that you’ve set for yourself.

5. Take responsibility for yourself

In this stage, you will practice being responsible for yourself, your circumstances, and your problems.

Follow these guidelines to ensure you are working on this exercise in a healthy way:

- Take full responsibility for everything that happens to you without giving your personal power and your agency away;

- Acknowledge that you have the personal power to change and influence the events and circumstances of your life.

Remind yourself of what you have learned through all of these exercises, and know that you hold the power in your own life. Revel in your well-earned sense of self-worth and make sure to maintain it.

Check out the four worksheets below that can help you build your self-worth.

About Me Sentence Completion Worksheet

This worksheet outlines a simple way to build self-worth. It only requires a pen or pencil and a few minutes to complete. Feel free to use it for yourself or for your adult clients, but it was designed for kids and can be especially effective for them.

This worksheet is simply titled “About Me: Sentence Completion” and is exactly what you might expect: it gives kids a chance to write about themselves. If your youngster is too young to write down his own answers, sit with him and help him record his responses.

The sentence stems (or prompts) to complete include:

- I was really happy when . . .

- Something that my friends like about me is . . .

- I’m proud of . . .

- My family was happy when I . . .

- In school, I’m good at . . .

- Something that makes me unique is . . .

By completing these six prompts, your child will take some time to think about who he really is, what he likes, what he’s good at, and what makes him feel happy.

Self-Esteem Sentence Stems worksheet.

Self-Esteem Checkup

This worksheet is good for a wide audience, including children, adolescents, young adults, and older adults. The opening text indicates that it’s a self-esteem worksheet, but in this case, the terms self-esteem and self-worth are used interchangeably.

Completing this worksheet will help you get a handle on your personal sense of understanding, acceptance, respect, and love for yourself.

The worksheet lists 15 statements and instructs you to rate your belief in each one on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (totally or completely). These statements are:

- I believe in myself;

- I am just as valuable as other people;

- I would rather be me than someone else;

- I am proud of my accomplishments;

- I feel good when I get compliments;

- I can handle criticism;

- I am good at solving problems;

- I love trying new things;

- I respect myself;

- I like the way I look;

- I love myself even when others reject me;

- I know my positive qualities;

- I focus on my successes and not my failures;

- I’m not afraid to make mistakes;

- I am happy to be me.

Add up all of the ratings for these 15 statements to get your total score, then rate your overall sense of self-esteem on a scale from 0 (I completely dislike who I am) to 10 (I completely like who I am).

Finally, respond to the prompt “What would need to change in order for you to move up one point on the rating scale? (i.e., for example, if you rated yourself a 6 what would need to happen for you to be at a 7?)”

Click here to preview this worksheet for yourself or click here to view it in a collection of self-esteem-building, small-group counseling lesson plans.

If you’re a fan of meditations , check out the four options below. They’re all aimed at boosting self-worth:

- A Guided Meditation to Help Quiet Self-Doubt and Boost Confidence from Health.com;

- Guided Meditation for Inner Peace and Self-Worth from Linda Hall;

- Guided Meditation: Self-Esteem from The Honest Guys Meditations & Relaxations;

If you’re not fond of any of these four meditations, try searching for other guided meditations intended to improve your self-worth. There are many out there to choose from.

To learn more about self-worth and how to improve it, check out some of the most popular books about this subject on Amazon:

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are by Dr. Brené Brown ( Amazon );

- What to Say When You Talk to Your Self by Dr. Shad Helmstetter ( Amazon );

- The 21-Day Self-Love Challenge: Learn How to Love Yourself Unconditionally, Cultivate Confidence, Self-Compassion & Self-Worth by Sophia Taylor ( Amazon );

- Love Yourself: 31 Ways to Truly Find Your Self Worth & Love Yourself by Randy Young ( Amazon );

- Self-Worth Essentials: A Workbook to Understand Yourself, Accept Yourself, Like Yourself, Respect Yourself, Be Confident, Enjoy Yourself, and Love Yourself by Dr. Liisa Kyle ( Amazon );

- Learning to Love Yourself: Finding Your Self-Worth by Sharon Wegscheider-Cruse ( Amazon ).

If you’re more of a watcher than a reader, there are some great TED Talks and YouTube videos you can check out, including:

TED Talk: Meet Yourself: A User’s Guide to Building Self-Esteem by Niko Everett

In her talk, Niko Everett, the founder of the organization Girls for Change, discusses inspiring ways to build up your self-esteem.

TED Talk: Claiming Your Identity by Understanding Your Self-Worth by Helen Whitener

Judge Helen Whitener discusses self-worth through the lens of social justice and equality in this talk.

A Clever Lesson in Self Worth from Meir Kay

Sometimes all we need to kickstart or motivate us to work on our self-love and self-worth is a good, insightful quote. If that’s what you’re looking for, read on.

You yourself, as much as anybody in the entire universe, deserve your love and affection.

A man cannot be comfortable without his own approval.

Remember always that you not only have the right to be an individual, you have an obligation to be one.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Loving ourselves works miracles in our lives.

Louise L. Hay

The fact that someone else loves you doesn’t rescue you from the project of loving yourself.

Sahaj Kohli

Why should we worry about what others think of us, do we have more confidence in their opinions than we do our own?

Brigham Young

Don’t rely on someone else for your happiness and self-worth. Only you can be responsible for that. If you can’t love and respect yourself—no on else will be able to make that happen. Accept who you are—completely; the good and the bad—and make changes as YOU see fit—not because you think someone else want you to be different.

Stacey Charter

Your problem is you’re afraid to acknowledge your own beauty. You’re too busy holding onto your unworthiness.

It’s surprising how many persons go through life without ever recognizing that their feelings toward other people are largely determined by their feelings toward themselves, and if you’re not comfortable within yourself, you can’t be comfortable with others.

Sidney J. Harris

Most of the shadows of this life are caused by standing in one’s own sunshine.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

It is never too late to be what you might have been.

George Eliot

Stay true to yourself. An original is worth more than a copy.

Suzy Kassem

17 Exercises To Foster Self-Acceptance and Compassion

Help your clients develop a kinder, more accepting relationship with themselves using these 17 Self-Compassion Exercises [PDF] that promote self-care and self-compassion.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Self-worth is an important concept for both researchers and laymen to understand, and it’s especially important for us to be able to identify, build, and maintain a normal, healthy sense of self-worth.

Learning about self-worth can teach you how to be more happy and fulfilled in your authentic, loveable self.

What do you think is the most important takeaway from research on this topic? Do you think a lack of self-worth is a problem? Or perhaps you think an excess of self-worth is the bigger problem today? Let us know in the comments section.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Self Compassion Exercises for free .

- Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1991). Measures of self-esteem. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes, 1, 115-160.

- Bogee, Jr., L. (1998). Leadership through personal awareness. University of Hawaii. Retrieved from http://www.hawaii.edu/intlrel/LTPA/selfwort.htm

- Clark-Jones, T. (2012). The importance of helping teens discover self-worth. Michigan State University – MSU Extension. Retrieved from http://www.canr.msu.edu/news/the_importance_of_helping_teens_discover_self-worth

- Covington, M. V., & Beery, R. G. (1976). Self-worth and school learning. Oxford, UK: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Crocker, J., Luhtanen, R. K., Cooper, M. L., & Bouvrette, A. (2003). Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85 , 894–908.

- Crocker, J., & Wolfe, C. T. (2001). Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review, 108(3), 593.

- Firestone, L. (2014). Essential tips for building true self-worth. Psych Alive. Retrieved from https://www.psychalive.org/self-worth/

- Grande, D. (2018). Building self-esteem and improving relationships. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/in-it-together/201801/building-self-esteem-and-improving-relationships

- Hibbert, C. (2013). Self-esteem vs. self-worth. Dr. Christina Hibbert. Retrieved from https://www.drchristinahibbert.com/self-esteem-vs-self-worth/

- Morin, A. (2017). How do you measure your self-worth? Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/what-mentally-strong-people-dont-do/201707/how-do-you-measure-your-self-worth

- Roberts, E. (2012). The difference between self-esteem and self-confidence. Healthy Place. Retrieved from https://www.healthyplace.com/blogs/buildingselfesteem/2012/05/the-difference-between-self-esteem-and-self-confidence

- Sicinski, A. (n.d.). How to build self-worth and start believing in yourself again. IQ Matrix. Retrieved from https://blog.iqmatrix.com/self-worth

- Stosny, S. (2014). How much do you value yourself? Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/anger-in-the-age-entitlement/201406/how-much-do-you-value-yourself

- Wong, S. J. (n.d.). 13 things that don’t determine your self-worth. Shine. Retrieved from https://advice.shinetext.com/articles/12-things-that-dont-determine-your-self-worth/

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

So, you check the appropriate boxes in a worksheet you somehow develop self worth?

This was very helpful, thank you. It encapsulated a lot of topics I wanted to touch on during therapy. Well-researched and written 🙂 Especially love how you linked how most people who struggle with self-worth, struggle with relationships.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Social Identity Theory: I, You, Us & We. Why Groups Matter

As humans, we spend most of our life working to understand our personal identities. The question of “who am I?” is an age-old philosophical thought [...]

Discovering Self-Empowerment: 13 Methods to Foster It

In a world where external circumstances often dictate our sense of control and agency, the concept of self-empowerment emerges as a beacon of hope and [...]

How to Improve Your Client’s Self-Esteem in Therapy: 7 Tips

When children first master the expectations set by their parents, the experience provides them with a source of pride and self-esteem. As children get older, [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Self-Compassion Tools (PDF)

Excellent essay writing blog for students seeking help with paper writing. We provide exclusive tips and ideas that can help create the best essay possible.

Brilliant Self Esteem Essay: Writing Guide & Topics

Self-esteem is a personal trait that has proven to withstand both high and low tides. It is a state which carries within itself a wide range of beliefs about oneself. Also referred to as self-respect, self-esteem is the confidence in one’s worth or abilities.

It is a subject of great interest to many people. Having a spiced up and captivating essay about self-esteem can guarantee a considerable readership or high grades for students. Many people, especially college students, have a problem with this, and hence we are here to help.

To start us off, let us look at a self-esteem essay example on the effect of social media on self-esteem:

Effect of Social Media on Self-Esteem Essay

“In the last decade, social media has tremendously gained popularity. Its impact and power have left permanent effects on many people and different facets of life. Many people have, therefore, developed high or low self-esteem concerning social media. More research shows that there exists a strong relationship between self-esteem and social media. Facebook has caused a decrease in self-esteem in many people.

Many teenagers are using social media, especially Facebook, to build relationships. There are a lot of people on Facebook of all ages, races, gender, and ethnicity. It is, therefore, natural for teens to mingle and socialize on this platform. Most of the people on social media purport to live “flashy lifestyles,” while in reality, that is not the case. It, therefore, creates a decreased self-esteem on those who cannot live up to those standards.

Social media, through social networking sites, enables people to make social comparisons. For instance, people may try to copy the lifestyles of celebrities. However, those who cannot meet their celebrity status tend to have low self-esteem. The psychological distress of such individuals is higher, resulting in low levels of self-esteem. Many people have, therefore, become victims of lower self-esteem and, consequently, low self-growth.

In conclusion, social media has a very high impact on the self-esteem of individuals. Usage of social media for social networking, communication, and building and maintaining of relationships has diverse effects. There should be sufficient information to help people not fall victims of these adverse effects.”

From the self-esteem essay conclusion above, it is evident that we have not introduced any new idea. You only need to restate the thesis statement and provide a solution to the problem.

We are now going to explore some exciting self-esteem topics with explanations on what to cover in such essays.

“What is Self-Esteem Essay” Topics

- Self-esteem essay, Low Self-Esteem: An expository essay

Here, you will have clearly and concisely investigate low self-esteem, evaluate pieces of evidence, expound on it, and provide an argument concerning it.

- What is Self-esteem? A critical analysis of theories on the function of self-esteem.

Such an essay requires you to explore the various approaches that show the role of self-esteem in individuals or society at large.

- Understanding the concept of self-esteem

It is a topic that digs deep into the breadth and depth of self-worth and makes readers get a clear picture.

- A descriptive study of self-esteem

It is about describing or summarizing self-esteem using words instead of pictures.

- State self-esteem

Topics on Social Media and Self-Esteem Essay

- The Paradox Effect of social media on self-esteem

Describe how social media is giving off the illusion of different choices while making it harder to find viable options.

- Self-esteem and ‘vanity validation’ effect of social media

Show how the interaction of people with social media for an extended period, inevitably feels compelled to continue to check for updates.

- The Dark Side of Social Media: How It Affects Self-Esteem

- Social Media and Confidence

How is one’s self-worth in terms of confidence boosted by social media?

- Social media and depression

Let readers see how depression can result from the use of social media with real-life experiences.

- Importance of Self-Esteem

Self-Concept and Self-Esteem Essay Topic Ideas

Explain how self-concept underpins self-esteem. Evaluate the different approaches to self-esteem. You can also discuss the application of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs of self-actualization. Giving the usefulness of the motivational theory for boosting self-esteem will add weight to your essay.

Topic Ideas on How to Improve Self-Esteem

- Tips to Improve Self-Esteem

Give detailed and well-researched advice on how people can boost their self-esteem

- Steps to Improving Self Esteem

Here are more topic ideas on how to improve self-esteem: 1. Top 5 tactics to change how to improve how you see yourself 2. Things you can do to boost your self-esteem 3. Understanding and building low self-esteem

Take a break from writing.

Top academic experts are here for you.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents