- Our Contributors

- For Submissions

- Creative Commons

- | Kashmir 2019 Siege |

C onversation is a basic element in the medium of comics, where much of the narrative appeal is derived from the interplay between dialogue and action. The speech balloon, a favoured visual symbol for voice and utterance in the medium since the mid-twentieth century, has become a symbol for comics. In Italian, famously, the word fumetto —the word for a speech or thought balloon—also refers to the art form itself, whether in the form of a comic strip or a comic book. In fact, dialogue is such a central feature in the medium that it may sometimes be difficult to think of it as a distinct element. A character who speaks his thoughts aloud when apparently nobody is listening is a much-used convention, and many comics, for instance, ‘talking heads’ or humoristic comic strips that deliver a verbal gag, focus on speaking. Perhaps paradoxically, dialogue scenes may be more distinguishable when their use is more restricted, for instance, in comics when action is predominant and only occasionally interrupted by a scene of talk or when first-person verbal narration is predominant, as in autobiographical comics that occasionally lapse into dialogue.

The reason for the popularity of the dialogue form in comics is at least partly related to medium-specific constraints and affordances that encourage its use and, concomitantly, restrict the employment of more indirect forms of speech and thought representation. In contrast with dialogue, forms of indirect discourse, such as free indirect discourse or the narratorial reporting of a character’s speech, tend to demand more space for words. Conventional strategies for distinguishing between these modes of verbal narration have included their visual form and placement in relation to the images. The dichotomy between narratorial voice in caption boxes and dialogue or other forms of direct speech in text balloons is not always clear-cut, let alone all-inclusive. Speech in comics can also occur in captions, verbal narration can take place in text balloons, the narrator’s and the character’s voices may intermingle, 1 and neither verbal narration nor direct speech or thought must be placed in boxes or balloons. Moreover, text in comics can occur outside these two categories in the image background or as part of the image. However, the continued assertion of the difference between direct speech and other modes of verbal narration in comics also needs to be taken into consideration as an important convention in the medium.

This chapter focusses on the dialogue form as a key narrative device and technique, and it examines the main compositional principles and narrative functions that characterize conversational scenes in comics. The starting point in this investigation is the multimodal character of speech and conversational exchange in comics. This requires us to focus on the interaction between the utterance and the elements of the image. Thus, on the one hand, I will discuss the ways in which dialogue, in the form of written speech, interacts with what is shown in the image, such as the interlocutors’ facial expressions, gestures, body language, and other visual cues of mental states and participant involvement. Furthermore, this necessitates an investigation of the visual possibilities and expressive functions of typography, the graphic style of writing, onomatopoeia or imitatives, 2 visual symbols, and standalone nonletter marks in the written rendering of conversation. On the other hand, I will discuss the function of speech balloons as metaphors for an utterance—‘utterance’ meaning here a specific piece of dialogue—voice, and turn-taking, and their narrative role in organising the time of the speech event and the order of its reading. Utterances in comics are characterised by their dual role as both instances of imagined speech in the world of the story and written language to be read. As to their latter function, it must be taken into account that readers of comics need to process the relations between the various utterances both in a single panel, when it includes several utterances, and between the panels in order to create a sense of a continuous conversation. Finally, I will briefly discuss some strategic uses of contrast and emphasis between visual and verbal narration in speech representation in comics.

The ultimate goal of this chapter is to develop a medium-specific understanding of the dialogue form in comics and outline the basic narrative functions of scenes of talk in comics. In this investigation, different examples will be drawn from innovative uses of dialogue in this medium. The subject is admittedly very broad. Within the bounds of this chapter, I can merely hope to highlight the main features of interest in this crucial and often central form in comics.

The Embodied Speech Situation in Comics

Given the multimodal nature of the medium and the importance of visual showing in comics, the question of dialogue in comics requires us to think of the areas of interaction between the image content, such as the portrayal of the participants in the conversational scene, the utterance that is placed in the image, and the main formal aspects of the composition, such as panel relations and the page layout. First, let us consider the ways in which the participants in such scenes are visually shown to be engaged in the speech situation by means of nonverbal communication. Such means include, especially, facial expression, posture, hand gesture, eye contact (or gaze), and the expressive distortion of the interlocutors’ bodies.

Existing research on the gesture-utterance connection in comics suggests that the use of gestures as signs of emotion largely follows real-life models in everyday speech situations (Fein and Kasher 1996; Forceville 2005). Both in everyday real-life conversation and comics, body language and posture are elemental communicative resources. At the same time, however, research has also suggested that in comics, since they commonly simplify and exaggerate bodily forms through caricature, the speaker’s and the recipient’s gestures often have a more prominent role than in real life (see Forceville 2005, 85; Fein and Kasher 1996, 795). In particular, facial expressions that are based on elemental features, such as eyebrows, eyes, gaze, mouth, furrows, and wrinkles, or the head position, are conventionally exploited as signs of emotion, thought, attitude, and stance. Similarly, speech in comics, while it may seek to be verisimilar and can provide the linguist with useful examples of spoken language, can take on wilfully distorted forms, such as simplification or exaggeration, that are different from uses of spoken language in real-life speech situations. 3 As dialogue in comics also necessarily has a written form and often an ostentatiously graphic and handwritten quality, the study of speech in comics needs to be sensitive to graphic features and the visual effects of written language.

Rodolphe Töpffer, who many see as the inventor of modern comics, claimed in his essay “Essai de physiognomonie” (1845) that a graphic trace has unique expressive potential, especially in relation to the drawing of a human face. For Töpffer, all faces in drawings, however, naively or poorly completed, even in the form of simple scribbling, possess a fixed expression. He further surmised that the viewer can recognize such expressions without education, knowledge of art, or any experience in drawing a face. 4 Similarly, one of the basic tenets in today’s psychological research in face recognition is that people identify faces from very little information. In such identification, as in recognizing an emotional expression, the eyes and eyebrows are among the most salient regions to pay attention to, followed by the mouth and the nose (Sadrô et al. 2003; Sinha et al. 2005). Töpffer saw, similarly, that in order for the drawing of a face to be effective, one needs to focus only on a limited number of key aspects, such as the eyes, eyebrows, nose, nostril(s), chin, forehead, wrinkles or folds of skin, and the shape of the head. 5 Töpffer also thought that the relation between these facial features and the person’s posture—the form of his or her upper body, gestures, and attitudes— mattered, even though he did not see them as important as the internal features of a face (the eyes, nose, and mouth).

As recent psychological and sociological conversation analysis has shown, facial expressions can enhance or disambiguate the speaker’s and the recipient’s stances towards what is being said in real-life speech situations (Ruusuvuori and Peräkylä 2009). In comics, likewise, a basic element of speech representation is the relation between verbal utterances, facial expressions, and other features of body language such as eye contact, typically accompanied by the sense of perspective and field of vision that are inscribed in the image. For instance, a way of speaking and listening can be revealed by an exchange of looks in subsequent gaze images, images portraying someone looking at something or someone, or reaction images, that is, images showing someone’s reaction to something that is said. A recipient’s look can, for instance, indicate pensiveness, concentration, or confusion, affiliation with the topic or the speaker, the sharing of an understanding, or the rejection of an idea, or it can reveal what is important and salient in the conversation situation as a whole. 6

Notice, for instance, the significance of facial expression, gaze, body language, and hand gestures in this scene from Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain’s Quai D’Orsay. Chroniques diplomatiques II ( Weapons of Mass Diplomacy 2012), which depicts a meeting between the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, Alexandre Taillard de Vorms (inspired by Dominique de Villepin), his speech writer Arthur Vlaminck, and a representative of the logistics department, Gilles Mande (Figure 9.1). In this scene, the furious minister protests to Mande about not being able to have a bigger aeroplane (Airbus) for himself and his advisors on a diplomatic visit to Russia. The intensity of the minister’s gaze and his facial expression, emphasised in the closeup image framed to show only his piercing eyes and part of his gigantic nose, convey the persistence of his stance, as well as his manipulative attitude towards the others. The minister pours forth a tirade of complaints, evidently fuelled by a sense of self-importance, about the tightness of space in the smaller Falcon aircraft that has been offered to him and his staff. All this is accompanied by expressive and manipulative hand gestures.

Besides facial expressions and gaze, hands, hand gestures, and arm positions can also have a significant function in speech situations in comics, communicating meaning themselves or specifying the words’ meaning. Two likely reasons for the significance of hands in comics are that we can gesture meaningfully and simulate shapes and things much more accurately with our hands than with other body parts, and that they can relatively easily be drawn to demonstrate this. 7 Hand gestures may be used as forms of illustration, specifying a type of action, a spatial relation, or a physical shape of something, or as a form of emphasis, while a hand can also point to an object, place, or the interlocutor. Waving, pointing, and beckoning can have a conversational function, for instance, as an expression of the participant’s emotion, attitude, and personality, and also as a conversational signal. The salience of hand gestures in the image, or facial expressions, for that matter, can be further emphasised by means of layout, perspective, foregrounding, or visual means of emphasis.

Figure 9.1 Abel Lanzac and Christophe Blain Weapons of Mass Diplomac y (2012/2014). Trans. Edward Gauvin © 2014 SelfMadeHero.

The meaning of the participants’ positions in an interaction, and what psychology calls (inter)personal space behaviour or proxemics—how people use the personal space around them as they interact with others— can be effectively portrayed in comics by showing how participants in a scene of talk take their space or relate to each other and the surrounding environment. Focus on a particular person in a closeup image or framing the image close to a participant or his or her field of vision may also suggest a (narratorial) sense of proximity to that participant. 8 This is also common in film narratives. A more medium-specific aspect of significant body language in comics is the nonrealistic manipulation and distortion of body shapes through caricature, that is, the relative malleability of the drawn body. We can observe this, for instance, in the above example from Weapons of Mass Diplomacy where Alexandre Taillard de Vorms’s shoulders and nose change their proportional size from panel to panel. The speaker’s body is thus modified to reflect his speech, attitude, and personality; the body has an expressive function in itself.

Conversational scenes in comics, as in film narration, have an advantage over dialogue scenes in literature in that they may show various nonverbal communication cues, which cooccur with verbal communication and can combine the effect of such cues. All visually observable aspects of nonverbal communication that may be integrated in a face-to-face dialogue in real life can also be portrayed in comics: facial expression, posture, gesture, eye contact, touch, adornment, physiological responses, position and spatial relations, personal space, locomotion, and setting. 9 While comics, at least in the traditional forms of printed strips or books, cannot usually represent sounds, they have developed various ways of suggesting auditory signals and vocal behaviour, such as onomatopoeia, sound effects, and symbols. All these cues are potentially relevant in conversational scenes in comics, where they cooccur with the verbal utterance. As they interact with each other and the utterance, these devices help the reader to create a sense of a continuing speech event, or what is meant by what is said; better perceive the participant’s mental state, attitude, and intention; and grasp the nature of the relation between the speakers. Yet, the ways in which cartoonists may take advantage of the rich possibilities of nonverbal communication in the medium vary greatly. For instance, while facial expressions are generally important, from children’s comic strips to adult-oriented graphic novels, or from superhero comics to nonfiction reportage, some cartoonists also simplify facial expression cues or minimise their use. 10 Thus, the varying aspects of nonverbal communication, and in some cases even facial expressions, can be conceived of as optional tools of visual showing and narration in conversational scenes.

Symbols of the Speaker’s Mental State and Engagement

In much comics storytelling, the use of visual symbols and verbal-visual signs that emanate from the characters may also contribute significantly to speech representation and dialogue scenes. In the passage of Weapons of Mass Diplomacy above, Mande’s heavy sweating, shown with drops of sweat, his changing facial skin colour, and later also his gradually shrinking head and body clearly point out his submission to the minister’s authority. The visual symbols around his head, which the cartoonist Mort Walker has called ‘emanata’ and John M. Kennedy identified as ‘pictorial runes’ (1982, 600), 11 portray emotions (agony), mental states, and an internal condition (submission). These and similar graphic devices, such as drops of sweat or more symbolic signs such as wiggly lines, starbursts, circles, halos, and clouds, often have little or no relation to the outer signs of emotion and attitude in real-life speech situations. As conventions that are used in modern narrative drawings from cartoons to comics, emanata are metonymically motivated signs that result from a character’s emotion and thought or some immediate sensory stimuli and effect. Typically, they specify the force of the speech act, a speaker’s enthusiasm or uncertainty, the recipient’s understanding or lack of understanding of what is said, acceptance and disappointment, or, as here, gradual submission to the speaker. Emanata and altered body shapes can also portray types of perception and reactions, including the sense of cold and warmth, smell, newness, light, and brightness or perceptions of speed, reflection, sudden or fast movement (speed lines), the direction of movement, or surprise and suspense. Not all comics employ them, but when they are used, they can contribute significantly to our understanding of the other elements in a scene of talk such as facial expression, gestures, and gaze.

Beyond the emanata, or pictorial runes, conversational scenes in comics can also comprise various other signs, including standalone punctuation marks, 12 pictograms, 13 sound effects, imitatives, and onomatopoeia 14 that have similar or related functions. Placed in the space in the image around the characters, or possibly continuing from panel to panel, these signs can equally specify the characters’ emotions, thoughts, and attitudes or a way of acting, behaving, and speaking; clarify what is said; or express movement, sounds, and other sensory stimuli that are relevant in the scene.

Comics imitatives, which are widely used for humorous purposes, approximate nonlinguistic sounds and action or contact between the characters, as well as attitude, emotion, sensations, and movement by adapting them to the phonemic system of the language. Onomatopoeia and sound words (or descriptive sound effects), which can be regarded as a specific case of imitatives, represent sound and voice in verbal form and, at the same time, often aim for a visual effect, which in itself can mime some quality of the sound or reflect its source, such as an event causing the sound. Onomatopoeia may also indicate variation in sound effects such as volume, pitch, timbre, and duration. Typically, onomatopoeia fit the phonology of the language in which they are used (‘boom!’, ‘wham!’, and ‘whoosh!’ in English or ‘baoum!’, ‘pff!’, and ‘vlan!’ in French). In comics storytelling, however, it is also common that an onomatopoeic adaptation of a sound does not necessarily have to constitute a word or even be pronounceable. Onomatopoeic expressions in comics are not usually reducible to the sound that they imitate—one reason being that they are given a visual, graphic form that contributes to their meaning and effect. The use of standalone descriptive words (or descriptive imitatives) for sensations and emotions is also common (‘snort’, ‘gasp’, ‘tickle’, ‘sigh’, etc.).

Stylistic elements of writing, such as lettering, typography, and fonts, as well as what has been called para or quasi-balloonic phenomena, 15 can be incorporated in a dialogue scene for similar purposes. The graphic style in which speech is written is often meaningful in such scenes in two senses. First, the graphic style of writing can create an effect of continuity between the world of the story, or the speech situation, and the written speech. For instance, written speech can be placed and shaped in the image field so that it reflects the visual contents of the image. 16 The graphic line that depicts the speaking figures can also give the impression of continuity in the writing (or vice versa). Second, the style of writing can in itself express certain aspects of the utterance, such as emphasise the meaning of a word, a phrase, or an utterance through bold lettering, convey humour, add a metaphorical or ironic layer through a stylistic change, imply a way of speaking or type of voice (whispering, singing, a broadcast voice, and so on), the intensity of speaking (by changing the letter size, for instance), and the speaker’s attitude or emotional state. It can also portray differences between the speakers’ register, style, or voice. Not all comics use the rich graphic potential of writing in this regard, but the style of writing and the choice of typography are important features of conversational scenes in many comics. Think, for instance, of Walt Kelly’s Pogo , or Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman , where typographical choices may reflect the characters’ personality or attitude, or René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s Asterix , where changes in lettering can indicate important vocal and linguistic differences in the characters’ speech (accent, dialect, stylistic register, language). By these means, written dialogue in comics can overcome some of the limitations that affect the representation of spoken language in conventional literary fiction. 17

All in all, the various visual and verbalvisual signs that have become conventionalised in comics can be metaphorically motivated as indexes of a speaker’s emotions, thoughts, attitudes, and perceptions. All these features may also contribute to the meaning of what is said, and potentially influence the reader’s attribution of mental states to characters. Frequently, such signs work together to identify the speaker’s attitude, complementing the meanings of facial expression and body language, and thus specify or enhance the speaker’s relation to the propositional content of the utterance and the other participants in the scene. 18

Let us take as an example the main components of a scene of talk in Finnish cartoonist Aapo Rapi’s (auto)biographical narrative Meti (2008). This story is based on the cartoonist’s interviews with his 80yearold grandmother Meeri Rapi, known as Meti, but it also has a strong autobiographical dimension: the cartoonist pictures himself in the story, meeting and conversing with his grandmother, taking notes during the conversation, and relates some other events in his life at the time of the interviews and the storytelling. The narrative perspective of Meti is often ambiguous in that there are clues in the story that let the reader think that it is told and illustrated in the way that Aapo imagines the events have happened—Meti’s story would thus be within the frame of Aapo’s imagination—but there are also passages in the narrative where Aapo’s story and Meti’s memories appear to be in competition. At times, the frame narrative and Meti’s narrative also coalesce, resulting in a kind of intersection of stories.

Figure 9.2 Aapo Rapi. Meti (2008) © Aapo Rapi.

Here, in this scene of five panels, the speaker’s and the recipient’s facial expressions, posture, gaze, exchange of looks, perspective, and emanata play a vital role together (Figure 9.2). We first see the cartoonist meeting with his grandmother. When Meti attempts to formally introduce herself with ‘My name is M–’, the cartoonist, visibly frustrated by this introduction—indicated by drops of sweat springing from his face, accompanied by a few drops of coffee spilled from his cup—interrupts her and insists that she should speak as she ‘normally’ does, that is, not in formal discourse. Consider also the importance of gazes and perspective in this scene. Both speakers are present in all images, but seen from different angles and distances. The alternating perspective of the images allows us to see the scene from behind both characters’ shoulders and thus share their viewpoints to some extent. Notice also that the cartoonist’s face is much more expressive of emotion and mental state—changing from signs of haste and frustration to calm—than that of the stony-faced main character. Moreover, Meti’s large nonreflective glasses are in stark contrast with the youthful expressiveness of her face in the narrated memories that follow this scene.

The Bond between the Speaker and the Utterance

Speech and thought balloons were successfully incorporated into American newspaper comic strips in the 1890s. In earlier European comics and cartoons, the same device had already been widely used, including British satirical broadsheet prints (1770–1820), but in Töpffer’s and in many other mid-nineteenth-century European cartoonists’ works, speech was usually represented in captions that were placed underneath the images. Only by the 1940s and the early 1950s did the representation of speech in speech balloons become a dominant convention in the medium in most Western countries. 19 Since then, other options for representing direct speech, such as speech quoted or summarised in captions, have remained in relatively limited use. Many contemporary cartoonists, however, represent utterances without resorting to speech balloons. For instance, in Brecht Evens’s graphic novels and in much of Claire Bretécher’s work, the utterances are simply placed physically close to the speaker in the space of the image, possibly but not necessarily accompanied by a tail that connects the utterance to the vocalizing source.

Regardless of whether comics use the speech balloon format or not, the general principle that an utterance is tied to a source that is shown in the image or to a source that is situated close to what is shown appears to be a default expectation in comics. The tail emanating from the balloon, or in some cases from the text without a frame, makes this association even more evident as it directly points to the source of the utterance. If the speaker is not shown in the image field, the default expectation is that the balloon and the tail indicate that someone is just outside the visible space or is not yet or no longer in the field of vision, or that the source of the utterance is too small or hidden to be seen (see also Forceville et al . 2010, 69).

Thus, the speech balloon and its tail, which can take a variety of different visual forms, express the contents of the utterance and, at the same time, are visual symbols of a speech act. In the latter function, we need to underscore their metaphorical function, which has something in common with metonymy: the balloon and its tail stand for a speaking voice (or a sound), the place, time, and duration of speaking, and the act of speaking itself. The relationship between the balloon and the speech act can thus be conceptualised as a structure of contiguity where, with the written utterance representing spoken language, the visual form of the speech balloon stands in a metaphorical relation to the source of the voice and, possibly also, to particular aspects of that voice or sound (intonation, for instance). In contrast, thought balloons represent the speaker’s thoughts and inner state. The distinction between speech and thought balloons is not always unambiguous in comics, or their difference may be irrelevant—does it always matter, for instance, whether a person speaks or thinks aloud to himself?—but in general they are distinguished by various visual markers such as the shape of the balloon and the tail or the background colour.

Being a visual metaphor (or metonymy) for a speech act, the balloon and its tail also perform the function of speech tags. In fact, they can realise the speech tag function much more efficiently and economically than any verbs of saying that traditionally introduce an utterance in literary narratives. The function of the tail, specifically, is to identify the speaker in the image. 20 The balloon and its tail not only point out the turn-taking, the source of the utterance, and the place of the speaker, but often also tell us how someone is speaking—the intonation, intensity, and volume of speech may be reflected in the shape, size, place, or colour of the balloon and its tail—or reveal the speaker’s attitude towards what is being said (linguistic modality). Balloon frame styles, background colour, and tail shapes regularly depict emotional states and sensory experiences (uncertainty, (dis)approval, ‘warm’, ‘icy’), a type of voice (electronically relayed, distant, shrill, high, low, harsh, broken, and so on), or volume (loud, quiet, shout, whisper). Lettering, typography, and visual signs inside the balloon can have similar functions or can amplify them. If in the Asterix albums typography can be a sign of a different language and dialect; in Brecht Evens’ graphic narratives, the colour of the text identifies the speaker ( The Wrong Place , 2009; The Making Of , 2011; Panthère , 2014).

The expressive uses of the speech balloon are well known to comics readers and scholars, but perhaps less to academics who study the dialogue form across media. Charles Forceville has shown how different visual variables of comics balloons—contour form, colour, fonts, nonverbal contents, and tail use—contribute narratively salient information, for instance, with regard to the manner and topic of speaking or the identity of the speaker (2013, 258, 268). In other words, the visual variables of the balloon, especially in more nonstandard cases, make salient something in what is said, how something is said, or who the speaker is. This, again, requires that we evaluate the relation of the balloonic narrative information to the speaker and the speech situation as a whole. The place of the balloon in the scene or the breakdown may also be significant. Thierry Groensteen, who has made a theoretically grounded description of speech balloon functions in comics, has suggested that the place of the balloon is always relative to three different elements in the space of the page: the character who is speaking (the speaker), the frame of the panel, and the neighbouring balloons (situated in the same panel or a contiguous one) (2007, 75). Groensteen emphasises, in particular, the interdependence between the characters and the balloons (2007, 75, 83), claiming that their relationship is so strong that they form a sort of functional binomial, a bipolar structure that is a necessary organising device in comics. Moreover, Groensteen presumes that the characters in the panels are the most salient piece of information and, subsequently, echoing Töpffer, that the character’s face and physiognomic expression are the principal focal points of the reader’s attention (2007, 75–76). In reading comics, then, the reader would supposedly first view the character’s face and expression, and then adjust this information, reciprocally, with what is said, that is, the character’s represented speech. 21

The claim about the bipolar structure between an utterance and an utterer seems highly relevant with regard to most comics. The psychological study of face recognition has also proven that the human (biological) visual system starts with a rudimentary preference for face-like patterns, and that our visual system has unique cognitive and neural mechanisms for face processing (see Sinha et al . 2005). Yet, it seems worth asking whether the functional binomial between the speaker and the utterance is always dominant in guiding the cartoonist’s or the reader’s understanding of conversational scenes, or the order of their reading. For one thing, we still cannot say much that is not controversial about the reader’s order of attention in reading comics. Do we always start reading comics by viewing the characters’ faces? 22 Comics can vary greatly with regard to the relative amount of words they use, as well as for what purpose they use them (what kind of information is given verbally), let alone that the image-word ratio typically alternates within any given story. A dialogue scene can portray the participants’ positions, gestures, and relations in great detail, but in a ‘talking heads’ story or a verbal gag strip, words can also be the primary focus of the reader’s attention, whereas sometimes faces can tell next to nothing.

In addition, comics can successfully sever the relation between the speaker, words, and space of the speech situation by various means. This may be done, for instance, by excluding the speaker from the space of the image or the narrative level, by multiplying the number of speakers or utterances, and by making the connection between an utterance and a speaker ambivalent in the space of the image. 23 The relation between the utterance and the vocalising source may remain deliberately ambivalent, for instance, in panels where there is only speech and the characters are not seen, or not clearly seen, such as in panoramic images where the speaking figures may be shown far in the distance or are not visible at all, or in images where the vocalising agent is visually blocked. François Ayroles’s strip “Feinte Trinité”, which includes only speech balloons and no figures, pertaining to a conversation between a son, a father, a mother, and God, or the online comic strip Bande pas dessinée , challenges the basic bipolar structure further by never letting us see who is speaking.

Another challenge to the bipolar structure arises from the speaker’s ambivalent positioning between the picture space and outside it. In some rare cases, the speaker can also remain systematically absent from the images. Consider, for instance, the continuous commentator track in Altan’s Ada (1979) where a speaker, who is never seen, is emotionally involved in the narrative as its commentator and viewer. Much more common is that a voice may, once connected with a particular speaker, become disconnected from that speaker on the visual level of narration. This may occur, for instance, when utterances are superimposed on what is seen in the images, thus suggesting that what is seen is the character’s subjective vision. Towards the end of the frame narrative of World’s End , the Chaucerian story arc in The Sandman series, the voices of a group of characters at an inn called World’s End are superimposed in speech balloons on a double spread with images of an enlarging window pane through which they apparently look at a spectral funeral procession in the sky. The reader, thus, is invited to share their field of vision through the dialogue.

Still other challenges to the rule of the bipolar structure of speech in comics include the multiplication of speakers for one utterance and the use of one speaker as a representative of a group of speakers. For instance, Martin Cendreda’s one-page story, “I want you to like me”, experiments with this principle by letting a conversation continue from panel to panel while the speakers and their spaces keep changing (Chapter 3). This creates the effect of a communal mind that apparently thinks the same thought, and says the same thing, irrespective of the individual sources of utterance seen in the images (speakers, billboard, dogs). Similarly, ideas apparently voiced by one person can be attributed to a group of people. 24 A character’s voice may also occur in many parts of one panel. This can emphasise, for instance, the speaker’s quick movement, the effects of an echo, or the complexities of space, as happens in Asterix and the Banquet when the Gaul Jellibabix, who is not seen in the panel, says ‘Here!’ in six different corners of the mazelike alleyways of Lugdunum (modern-day Lyon) seemingly at the same time.

All these cases experiment with the basic expectations of speech representation in comics: an utterance is visually tied to a particular speaker, and both the utterance and the speaker belong to the space that is seen in the panel. Yet as the exceptions above show, the bipolar structure between the speaker and the utterance can always be modified, challenged, and even discarded. The exceptions make the rule more visible, but the flexibility of the structure also points out that, to better understand speech representation and dialogue in comics, it is crucial to think beyond the speaker-utterance relation to a number of other seminal elements of dialogue in the medium.

Still another important feature of conversational scenes in comics is the interaction between the utterance, the contents of the image and narrative captions. Narrative captions, which are typically distinguished from speech balloons by their frames, background colour, or typography, can also complement, evaluate, or interpret the speech acts presented in the images. In Daniel Clowes’s first-person narrative Mister Wonderful (2011), the contrasted and sometimes competing thought captions and speech balloons of the story make clearly visible the expected interrelations between the captions and the balloons. Here, the narrator’s thoughts, placed in square-shaped captions with a yellow background, are frequently superimposed on speech balloons that contain the narrator’s own speech or other people’s utterances, thus indicating, among other things, the narrator’s lack of attention to what is being said. On a few occasions, the speech balloons are also superimposed on the captions, thus suggesting that what is said interrupts the flow and momentum of the narrator’s thoughts. Thus, also, the connection between the speaker and the utterance in the balloon is momentarily broken.

The Temporal and Rhythmic Functions of Speech Balloons

Having investigated some basic formal elements of speech representation and scenes of talk in comics, we should be able to focus more specifically on how some of these elements realise narrative functions in comics.

Character-to-character dialogue, or combined action and dialogue scenes, are central forms of narrative organisation and development in comics, as in literary fiction and film. 25 Dialogue scenes move the story forward, for instance, by giving important information about the characters, their relationships, the milieu, and the evolving events; they can also build suspense and reorientate the narrative. In comics, dialogue also regularly accompanies action. In Asterix , much of the talking between Asterix and Obelix, which is a constant feature of the series, takes place when the two characters are on the move or doing something. Action and dialogue are constantly bound together: while moving or acting out a scene, the characters discuss their intentions, thoughts, and emotions or voice comments about an event or someone they have met.

What Sarah Kozloff has outlined as the main narrative functions of dialogue in film largely apply to comics. Dialogue in films, as Kozloff points out, can contribute to many if not all key elements of a narrative: world construction and identification, characterisation, communication of narrative causality (such as the relation between events or the significance of an event), enactment of a narrative event (the disclosure of important information such as the speaker’s emotional state), adherence to realism (plausibility), and control of the viewer’s evaluation and emotions (the sense of narrative rhythm, the effects of surprise and suspense) (2000, 33–51). Inevitably, a given instance of dialogue can fulfil several of these functions simultaneously.

What is different in comics in this respect may to some extent be self-evident. Comics lack the sound element, the means and possibilities of the moving image, and the actor’s work and personality is not an issue. With regard to narrative pacing and rhythm in comics, speech balloons play a vital role. Their arrangement in the panel, a sequence, or on the page, modifies both the sense of the time of the narrative and the order and time of reading. On the one hand, the utterances punctuate the story and the dialogue scene and, thus, create a sense of the duration of the event. Sometimes, the speech balloons can in themselves express duration through elongated forms of tails that surpass the frame borders. On the other hand, the speech balloons are part and parcel of the spatial organisation of the comic’s page. While the speech balloon constitutes a space where the utterance can be read, the placement and interrelation of the speech balloons in the space of the page also point out to the reader an order of looking and reading, functioning as one means of connectivity between the panels. From the reader’s perspective, thus, the utterances in a given narrative comic mark stages in the story that need to be attended to. 26 Speech balloons placed on the picture frames, for instance, or close to each other in neighbouring panels, can strengthen the link between the pictures and thus affirm the order of reading. Sometimes also, the space of the utterance can approximate the function of a picture frame or the space between the panels. The placement of speech balloons in a scene of talk may also emphasise, together with other features of the scene, particular aspects of the utterance and the speech situation.

The opening scene of Book One in Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s Preacher (1996) features a conversational scene between three characters, Jesse Custer, Tulip O’Hare, and Cassidy, who are conversing at a table in a diner in Texas. In this example, I would like to emphasise the significance of three factors in the depiction of the scene: the place of the utterance, the effect of the moving perspective, and the means of layout. The first time we see the protagonist Reverend Jesse Custer’s face and his clerical collar, his utterance—‘’cause lemme tell you: it sure as hell ain’t the church’—is placed over the frame border. Both the placement of the utterance, the particularity of which is emphasised by the fact that speech balloons very rarely cross the panel frames in this series, and the contrast between what Custer says and who he is stress the importance of the utterance (Figure 9.3). Further noteworthy elements in this panel are the angle of vision, which is placed squarely amidst the interlocutors and very close to Cassidy’s position in the scene, and the fact that two sides of the panel bleed off the corner of the page. The latter feature may compel the reader to turn the page to learn more about the contrast between the speaker and what he has said. In the following pages that depict the conversation, the perspective remains close to the characters, stressing the meaning of gazes and the exchange of looks. Moreover, and typically of dialogue scenes in many contemporary graphic novels, the perspective keeps steadily shifting around the conversing characters, moving to one more or less subjective angle of vision in each panel. Finally, page layout also contributes to this scene through the partial superimposition of some of the panels, such as a closeup image of Tulip O’Hare, on the surrounding panels, thus further aligning the interlocutors to each other and emphasising the importance of a particular gaze, expression, and utterance.

Concerning the sense of rhythm in such scenes, one default expectation is the correspondence between the utterance or an exchange of dialogue and the speaker’s (or listener’s) posture shown in the image. We could call this the realistic formula of time in a scene of talk. In other words, perhaps the most basic rhythm of speech representation in comics is one utterance per speaker, or one utterance and response per panel. Will Eisner, for instance, has stressed the importance of preserving such a bond between dialogue and action on the grounds of realism, claiming that a protracted exchange of dialogue cannot be realistically supported by unmoving static images. Furthermore, for Eisner, a verisimilar exchange of dialogue is one in which the utterances terminate the endurance of the image, that is, the dialogue corresponds with the speaker’s (or speakers’) posture in the image (1996, 60).

Figure 9.3 Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon. PREACHER . Book One (1995) © Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon. All characters, the distinctive likenesses thereof, and all related elements are trademarks of Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon.

However, Eisner’s presumption, while it illustrates a basic convention for representing duration in conversational scenes in much comics storytelling, can be contested as an all-encompassing general rule of realistic speech. Clearly, instead of undermining the sense of veracity in a conversational exchange, a long string or multitude of balloons in one panel can also enhance realism in narration. On the first page of Preacher , Cassidy’s and Tulip O’Hare’s utterances have two parts—their difference is marked, respectively, by the conventions of one balloon opening onto another and by a connecting tail between the balloons. This is a common way to indicate a short pause in speech. Elsewhere, the placement of many speech balloons in one panel can create the effect of a speeded-up and intensified exchange of words. Strings of balloons or a mass of balloons in one panel may, for instance, suggest the effect of an improvised discourse, conversational intensity (as in the streets of Lutetia in Les lauriers de César ), interruption and talking over others, the volume of speech, a cacophony of voices, and so on. Many superimposed balloons can also indicate a disconnection between speech and thought, as happens in Mister Wonderful , where the narrative captions that are placed on the speech balloons and sometimes even on the speakers’ faces emphasise the effect of an inner voice overriding speech. Moreover, a protracted exchange of dialogue in one panel may suggest a notable speeding or slowing of time in a scene of talk, instead of undermining conversational veracity.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the relation between speech and posture does not alone create the sense of rhythm in dialogue scenes. The panel-to-panel transitions and other spatial relations on the page, including the sense of time in a single panel, also affect our understanding of the time and duration of a scene of talk. In our previous example of Meti , the sequence suggests a slowing of time during the dialogue scene: the cartoonist’s hurry to start the interview—he is visibly out of breath when he enters the room in the first panel—is contrasted with Meti’s relaxed attitude. Meti’s calmness has become evident to the reader already in the previous wordless pages of the story, which portray her leisurely picking berries, preparing a pie, and baking it in the kitchen. The fourth and the only wordless panel in this sequence, in which the perspective is more distant and impersonal, powerfully suggests the passing and slowing of time. In these five panels, the cartoonist figure thus apparently adjusts to Meti’s sense of time by eating lingonberry pie and drinking coffee. Only then can the actual storytelling start.

Conversational scenes, when perceived as distinct scenes, may alter the temporal rhythm in relation to the surrounding narrative action. This dimension of dialogue scenes in comics corresponds with what Kozloff refers to as the control of viewer evaluation and emotional response through dialogue. In comics, as in film, such scenes can distract, create suspense and surprise, or control emotional response by elongating a moment and stretching out a suspenseful climax or pause. The conversation at the beginning of Preacher , which turns out to be a frame narrative for much of the ensuing story in Book One of the series, introduces us to the main characters and opens up several questions about their situation that will be dealt with in the subsequent instalments of the story. Scenes of talk can also slow down the tempo in the narrative, as in the example from Meti above, to the extent that they give us an impression of simultaneity between the time of the events and the time of their telling and showing. In comics that include extensive dialogue during the action, such as Asterix or other European adventure series, such as Spirou and Fantasio , such temporal changes may not be apparent, however, since the action and dialogue establish such a steady rhythm throughout the narrative.

Figure 9.4 Jérôme Mulot & Florent Ruppert. Barrel of Monkeys © 2008, Ruppert, Mulot & L’Association, Rebus Books for the english translation.

Jérôme Mulot and Florent Ruppert’s comic books, including Safari monseigneur (2005), Panier de singe ( Barrel of Monkeys , 2006), and Le Tricheur (2008), make visible a number of underlying principles in speech representation in comics. For instance, they extend the traditional realistic duration of speech in a panel: Ruppert and Mulot sometimes place up to twenty balloons per panel for one speaker and thus obfuscate the expectation of synchrony between the speaker’s posture in the image and the utterance (Figure 9.4). Furthermore, their work investigates the rules of readable information, that is, that speech balloons should contain informative utterances that are attributed to some agent in the story. Generally speaking, certain constraints guarantee the readability of speech balloons in comics. This means that one is to avoid (a) superimposed speech balloons that block the reading of other balloons, unless the superimposed balloons serve a clear narrative function such as indicating the simultaneity of many voices; (b) balloons placed in a semantically important part of the image (such as the speaker’s face); (c) balloons that are ‘cut’ by the image frame so that they become unreadable (this may also happen in Mister Wonderful to point out the narrator’s lack of attention or interest); and (d) continuous nonsensical expressions or empty balloons. However, single ‘blahblahs’ or empty balloons can be very revelatory of attitude or a lack of response.

Still other experiments with speech and thought balloons in Ruppert and Mulot’s comic books involve the breaking of the flat symbolic space of the speech and thought balloon. For instance, letters and signs regularly overlap the balloon contours and extend to the space of the image in their works, thus undermining the expectation that the balloon is an enclosed space in itself, or speech and thought balloons are treated as literal containers that convey the illusion of three-dimensionality. Some of Ruppert and Mulot’s speech and thought balloons, or their contents, can be seen, touched, and entered, whereas others may indicate the speaker’s movement in space as a kind of visual trace of the movement.

The Narrative Function of Visual and Verbal Contrast in Dialogue Scenes

Still another medium-specific aspect in conversational scenes in comics is the narrative effect (rather than function) of contrast, or narratively motivated transition, in the balance between visual and verbal narration. For instance, a scene of character-to-character dialogue in comics can always turn into a predominantly visual narrative that fleshes out the topic of the conversation in narrative drawings, or vice versa. This is a typical element in Aapo Rapi’s Meti and complicates in this story the question of the identity of the narrative agent responsible for what is shown in the images. Lilli Carré’s The Lagoon (2008), in turn, depicts a scene where someone is telling a tale, and the oral story is then transformed into a visual narrative that the reader can see evolving from panel to panel. The shift from verbal to graphic narration thus dramatises the temporal distance between the present of the storytelling and the past of the story events, but it also has the narrative effect of accentuating the storyteller’s skill of inviting the listener into her world and experiencing it from within. Such transferences between verbal and visual narration may in some cases be compared to shifts between different diegetic levels in a literary narrative, for instance when an interlocutor in a conversation becomes a narrator of his or her own story. Yet, the multimodal nature of comics allows the invention of forms of complexity in this regard, pertaining to the relation between the time of the events and the time of their telling, or the source and perspective of narration, that are not available in the monomodal context of literary narratives.

Cartoonists can set up tensions between verbal and visual narration in conversational scenes for various other effects as well. Another device for contrasting verbal and visual narration is to juxtapose the time and place of an ongoing conversation and the time and place of the events that are the topic of the conversation. For instance, at the beginning of JeanClaude Mézières and Pierre Christin’s Brooklyn Station Terminus Cosmos (1981), where the main characters Valerian and Laureline are engaged in a long telepathic intergalactic conversation, their dialogue provides the story with a narrative frame. This global frame embeds images from the speakers’ memories as short flashbacks as well as illustrations of things and events that the speakers have heard. The extended present moment of the dialogue thus creates a kind of intersubjective consciousness frame that incorporates different temporalities and changes of space, which are shown in the narrative drawings. The dialogue may specify that the things seen in the panels have a varying relation to reality—first or secondhand information, mnemonic images, or things seen in the speakers’ present whereabouts—or different meanings for each speaker. The overall effect, however, is not one of simple framing and embedding, but the time and space in which speakers are situated occasionally also appear to coalesce with those of their stories and memories as the speakers share the imagery through the telepathic link.

The ultimate goal of this chapter has been an attempt to develop a more general understanding of the basic elements, main compositional principles, and narrative functions of speech and dialogue in comics. One crucial area for future research that is indicated by this discussion is the way in which the image content, especially the embodiment of the participants, contributes to the conversational scene and the interpretative effects that the scene generates. Typically, the images in comics show involvement in scenes of talk through shared or contrasted perspectives, an exchange of looks, or through gesture, posture, and other physical signs of reaction to others. A key aspect of dialogue in comics in this respect is the depiction of the participants’ face and facial expressions. Visual symbols and verbal-visual signs, such as emanata, which are added to or around the participants’ face and head in some comics, can specify an expression, show mental states, and emphasise a reaction to someone or something that is said. Furthermore, comics may manipulate the characters’ body shape and size to underline certain aspects of a speaker’s experience, attitude, or personality, or their reaction and engagement in the speech situation. Together and in interaction with the verbal content of the dialogue, these elements produce an integrated, but often quite complex, whole.

Finally, all compositional and spatial elements in comics can have an expressive function that contributes to the reader’s understanding of conversational scenes in this medium. Changing picture frames, panel forms, panel and balloon shapes and sizes, page setup, lettering and letter size, nonrealistic backgrounds, 27 and other components of graphic style can convey relevant information, for instance, by emphasising or modifying the meaning of the utterances or pointing out the salient features in the situation. Moreover, the relations between the panels may imply relevant narrative information about the scene; the gaps in what is visually shown in the panel images need to be related to what is said but also to the gaps in the dialogue. The precise meaning of the potentially meaningful formal elements in a scene of talk depends again on the cooccurrence and combination of these elements and on their tension and interaction with what is said and shown in the images.

Comics share various functions of narrative communication through dialogue with other narrative media, but also employ many medium-specific strategies that render impossible any direct comparison with dialogue scenes in literature or film. Speech in comics is not only given in a written form but also (usually) in a drawn form, a kind of graphic writing. In this respect, comics vary greatly in the extent that they can maximize the graphic and typographical effects of written speech. The speech balloons function as a visual metaphor for a speech act, voice, and source. At the same time, the speech balloon, the tail, and paraballoonic utterances contribute to the organisation of the time of the narrative and the order and time of reading. Above I have also investigated the common convention in comics that an utterance is physically tied to its source, the speaker, and that this relation suggests a certain (imaginary) duration of time. By developing Thierry Groensteen’s (1999, 2007) insights about the elemental association between the speaker and the utterance, I have sought to contextualise this compositional principle in relation to other key elements of conversational scenes in comics.

1 See also Saraceni (2003, 66–67) on how this may happen in thought balloons and monologue.

2 Oswalt defines an ‘imitative’ as “a word based on an approximation of some nonlinguistic sound but adapted to the phonemic system of the language” (1994, 293).

3 See also Frank Bramlett, who stresses that a linguistic investigation of language in comics needs to consider the balance of realism in the characters’ language and the amount of linguistic exaggeration and simplification that is typical of the medium (2012, 183). See also Hatfield (2005, 34), Groensteen (2007, 129), and Miodrag (2013, 32–36).

4 The art historian Ernst Gombrich famously named this rule Töpffer’s law: “For any drawing of a human face, however inept, however childish, possesses, by the very fact that it has been drawn, a character and an expression” (Gombrich 1960, 339–340).

5 Bremond points out how the ‘teratological’ anatomies of certain characters in comics allow us to pose the question of which bodily organs are absolutely indispensable for the realisation of gestural messages (1968, 99).

6 One type of gazing that may be equally well-portrayed in dialogue scenes is the characters’ joint visual attention to something. For a reference in film studies, see, for instance, Persson (2003, 68–91).

7 See Baetens (2004) on the depiction of hands in Yves Chaland’s and Jacques Tardi’s works. 8 See, for instance, Persson on visual media and personal space (2003, 109–110). 9 Speakers in reallife speech situations can coopt almost any physical action conversationally, that is, demonstrate by timing an action with the verbal communication that the nonverbal act has a communicative function (Bavelas and Chovil 2006, 100).

10 E.S. Tan argues that some graphic novels avoid using the schema of facial expressions altogether, “either because it is too explicit, or because the emotions that characters have are too complex to be ‘told’ through the face” (2001, 45). I would argue that narration “through the face” is a matter of stylistic choice rather than a reflection of the story’s simplicity.

11 Kennedy distinguishes actual pictorial runes that are metaphorical, such as the state of anxiety shown by eye spirals, from graphic lines that have some literal intent as they attempt to convey perceptual impressions, such as lines radiating from bright light (1982, 600). Forceville has adopted Kennedy’s term (2005, 2011). In his tongueincheek lexicon, Mort Walker defines emanata as emanating outwards “from things as well as people to show what’s going on”, such as a character’s “internal conditions” (2000).

12 See also Dürrenmatt’s (2013, 115–127) discussion of how exclamation points, question marks, and ellipses have become autonomous means of description in the medium, especially for expressing characters’ emotions, mental states, and/or silence.

13 Forceville, El Rafaie, and Meesters distinguish a pictogram from a pictorial rune on the basis that an isolated pictogram, such as $ or ♥, has “some basic meaning of its own when encountered outside of comics”, unlike a pictorial rune such as motion lines, droplets, spikes, or spirals (2014, 492–493). They admit, however, that the borderline between the two categories may be fuzzy (2014, 494).

14 Suzanne Covey distinguishes between ‘descriptive’ sound effects, by which she means “words, usually verbs, that don’t attempt to reproduce the sounds they depict” and onomatopoeic words that try to approximate sounds at least to some degree (2006).

15 Forceville, Veale, and Feyaerts include in para and quasiballoonic phenomena the various nonbordered zones of the picture that display onomatopoeia and sound effects (2010, 65). On onomatopoeia in Frenchlanguage comics, see FresnaultDeruelle (1977, 185–199).

16 Some examples are discussed, for instance, in Dürrenmatt (2013, 165–167). 17 Compare with Chapman (1984, 18–24) on the difficulties of reproducing speech in written dialogue.

18 Forceville emphasises, importantly, the combined effect of nonverbal signs in comics in the representation of emotions such as anger (2005, 84–85). 19 See Smolderen (2002, 2009, 119–127) on why the speech balloon was rarely utilised as a citation of a character’s speech before Richard F. Outcault’s “The Yellow Kid”. There are important exceptions, however (see the last chapter of this book). Lefèvre discusses the gradual spread of the balloon device in European comics since its final breakthrough in the 1930s (2006).

20 Saraceni argues succinctly that the “function of the tail is equivalent to that of clauses like ‘he said’ or ‘Ann thought’ in reported speech or thought” (2003, 9).

21 Lawrence Abbott’s educated guess about eye movements and the order of reading comics is similar to Groensteen’s suggestions, but Abbott puts the main stress on words and verbal narration (1986, 159–162).

22 Will Eisner’s caution in this matter seems justified, even if eye-tracking research has made important advances recently: “In comics, no one really knows for certain whether the words are read before or after viewing the picture. We have no real evidence that they are read simultaneously. There is a different cognitive process between reading words and pictures. But in any event, the image and the dialogue give meaning to each other—a vital element in graphic storytelling” (1996, 59).

23 See also Forceville (2013), who discusses some effects of tailless balloons and tails that do not point toward an identified or identifiable speaker.

24 Carrier (2000, 42–43) associates this effect with a page from Joe Sacco’s Palestine , but does not explicate how the effect is created. See also Forceville (2013, 265–266) on a panel in Régis Franc’s Nouvelles Histoires: Un dimanche d’été , where a substantial number of tails do not point toward any identifiable speaker, thus creating the effect of a palaver where “it does not matter very much who is saying what”.

25 See also Phelan and Rabinowitz (2012, 37–38). 26 In Groensteen’s formulation, the positioning of the balloons in the space of the page creates a rhythm in reading as “each text fragment retains some moment of our attention, introducing a brief pause in the movement that sweeps across the page” (2007, 83).

27 On how pictorial metaphors in the image background may express a person’s emotional state in manga, see Shinohara and Matsunaka (2009, 283–290).

The Hooded Utilitarian

A pundit in every panopticon, how do comics artists use speech balloons.

This post is the first in a series on how comics artists represent talk in comics. I’ll be writing about speech balloons and how the discipline of conversation analysis (CA) helps us understand how creative these artists can be when they try to show the intricacies of everyday talk.

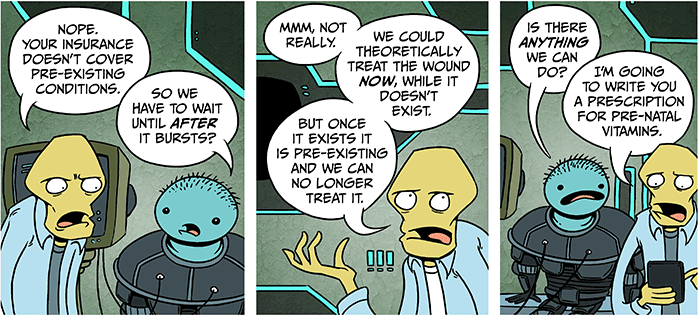

Consider the following two panels. These are from the webcomic Scenes from a Multiverse by Jon Rosenberg. (Click on each of the titles to see the full comic.)

Both of these are the final panel in the comic. Specifically, each one is panel 5 of a 5 panel comic. Understanding the speech and the speech balloons in these two panels will depend on the sequencing of balloons in previous panels and, to some extent, the social context of the conversation.

In most kinds of comics, speech balloons show conversations in relatively uncontroversial ways. In smaller panels, there may be one, two, or three characters producing speech, while larger panels and full-page panels may contain a dozen or more characters talking at the same time. In conversation analysis (CA), the approach to studying talk is to keep track of the number of turns, how long the turns are, how many speakers there are, and how much silence there is, among others. This post is the first in a series about speech balloons and conversation sequence. In particular, I will focus on how comics artists draw two or more characters talking at the same time.

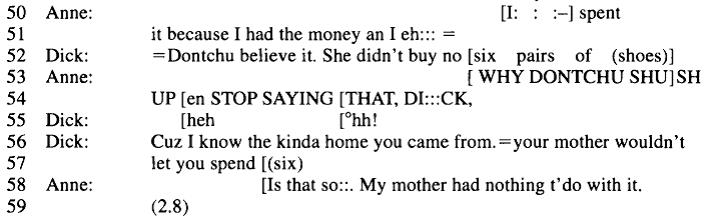

When two or more speakers produce speech at exactly the same time, then this is called simultaneous talk. (Sometimes it is called interruption, and sometimes it is overlap, but this depends on interpretation.) When listening to conversations, it is relatively easy to identify moments when participants are talking ‘on top of each other.’ And in transcribing the speech, there is a small set of typographical symbols that scholars typically use to do this. Consider the following excerpt, taken from an article by Emanuel Schegloff (2000) on simultaneous talk (p. 26). The two speakers, Anne and Dick, are an elderly couple who have been married for a long time. In this short excerpt, we see a good bit of simultaneous talk. Anne and Dick are having a conversation with their daughter, and it takes a funny turn in that Dick gives Anne a hard time about spending money on shoes and her claim about how many pairs of shoes she owned.

SOURCE: Schegloff, E. (2000). Overlapping talk and the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language in Society , 29 (1): 1–63.

Lines 52 and 53 are clear examples. According to this transcription, at exactly the same time that Dick begins the word ‘six,’ Anne begins her utterance with ‘WHY’. The effect is that while Dick already has the conversational floor, Anne joins in, and the listeners have to keep track of what both of them are saying. At the end of Dick’s word ‘shoes’, he stops speaking but Anne continues her turn through line 54. The use of all capital letters indicates that Anne is using a LOUD volume.

It’s one thing to listen to speech and write it down in a transcription. But in comics, it seems to me that it’s a creative challenge to represent simultaneous speech using speech balloons. In other words, how does an artist use visual cues (putting one balloon on top of another) to signal a certain kind of verbal cue (two or more speakers talking at the same time)?

The question I have is whether the visual difference in the balloons has a material impact on the way readers ‘hear’ the speech. Does the doctor’s turn ‘sound the same’ as the dad’s turn? If there is a difference, is it a difference of kind or a difference of degree? To answer the questions, we should examine each of the comics in terms of conversation and speech balloons.

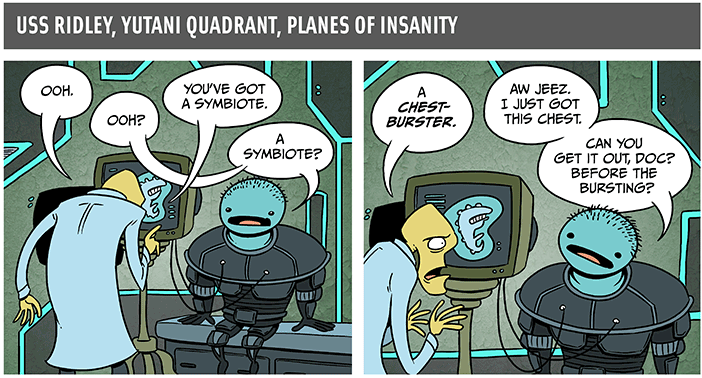

The Symbiote

The first two panels of ‘The Symbiote’ show very traditional strategies for representing turns and turn-taking. The doctor in panel 1 begins the sequence, with the patient taking the second turn, and the two trading off in panel 2 as well. Even though the tails cross in panel 1, I think readers would perceive these turns as more or less separate, perhaps with no simultaneous speech at all. In panel 2, the visual separation of the balloons is even clearer, indicating that the two speakers are being careful to take turns without ‘stepping on each other’s toes.’

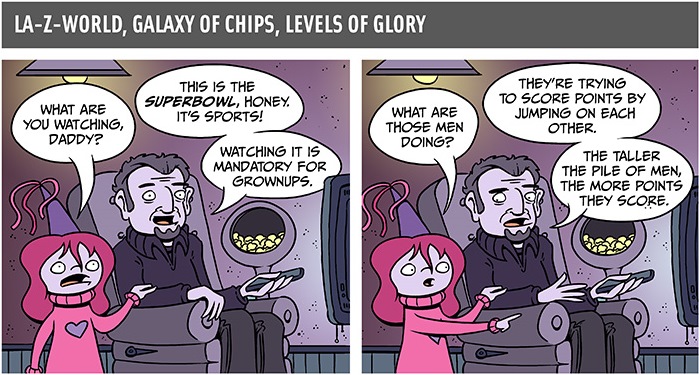

The Superbowl (sic)

In panels 1 and 2 of ‘The Superbowl,’ the speech turns proceed much like those in ‘The Symbiote.’ I think the visual separation of speech turns here is crisp, with the tails of the balloons never crossing. The content of the balloons indicates that the daughter takes the first turn by asking a question and the dad takes the second turn by answering the question. This is true for both panels.

If we consider the sequence of panels 3-4-5 in both comics, we may be able to discern more readily whether the speech in the final panels are indeed different kinds of simultaneous speech.

In both comics, panel three is composed very similarly. The speech balloons of speakers 1 and 2 are touching, and in fact the balloon of speaker 2 is ever so slightly overlaid onto the balloon of speaker 1. Panel 4 in ‘The Symbiote’ has just one speaker, the doctor, but Panel 4 in ‘The Superbowl’ shows the two speakers producing some measure of simultaneous talk.

As we saw at the beginning of this post, panel 5 for both comics shows that one balloon is overlaid on top of the other. It is more than likely that readers are supposed to ‘hear’ simultaneous talk. In other words, the doctor talks at the same time as the patient, and the dad talks at the same time as the daughter.

What interests me about them is that in both panels, one speech balloon overlaps the other. There are some slight differences, however. In ‘The Symbiote,’ the doctor’s speech balloon overlaps the patient’s speech balloon, but all the words are visible. On the other hand, in ‘The Superbowl,’ the dad’s balloon overlaps the daughter’s but also partially obscures two words ( on and grass ). What is not clear is whether the balloon obscures additional words or other symbols in the balloon, symbols like ellipses (…). But is the amount of simultaneous talk the same? If we hear the panels differently, what elements of each comic are we meant to consider when we decide how they sound?

When you read these two comics, how do you ‘hear’ the turns playing out? What might Rosenberg be trying to accomplish by drawing one speech balloon on top of another? How much does the turn-taking sequence affect our perception of the balloons? And how much of an impact does the social context or the identity of the speakers have?

In part 2 of this series, I’ll talk about simultaneous discourse in Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles .

12 thoughts on “ How do comics artists use speech balloons? ”

Nice job! I’d like to see you take on the elaborate, intertwined speech balloons in most Brian Michael Bendis comics: I’m not sure it’s simultaneous speech often, but it’s still a way to visualize rapid interchange.

I love overlapping speech bubbles, because they suggest a reading rhythm.

When I read comics, the extent of the overlap to me suggests to what extent one person is talking over another. In the first case above, I’d read that as the doctor ‘jumping in,’ but not talking over. Maybe the last word was spoken over, if at all.

In the second case, the father talks over a substantial part of the daughter’s speech.

I’d be interested in how this plays out in terms of the writer, artist and letterer collaborating to present the conversation.

Oh, and a couple of years ago a wrote a piece for Sounding Out! about sound in comics and argued (in part) that our familiarity with the rhythms of conversation help provide the inter-panel closure that make comics work.

“This is Not a Sound”: The Treachery of Sound in Comic Books

Hi, Corey! Thanks! I’m not familiar with Bendis, but I will put those comics on my reading list.

Kailyn, I think you’re right. It seems that the dad more actively ‘cuts off’ what the daughter is saying.

Thanks for the link, Osvaldo. I will check it out!

If you haven’t already, I recommend that you take a look at Howard Chaykin’s American Flagg!

I find the final panel of the Super Bowl sequence particularly fascinating (and by the way Frank – I suspect that you are one of a minority of academics who would have caught the mistake in “Superbowl”!)

I like to think about the content of comics panels on roughly Waltonian terms, as some of you know (see Kendall Walton: Mimesis as Make Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts, Harvard 1993). So the question I like to ask is: What are we meant to imagine when ‘decoding’ the panel and its contents?

Now, consider the partially obscured word “grass” in the last panel, and the undepicted but somewhat strongly implied final word “for” in the same panel. There are at least six questions we can ask:

(i) Are we meant to imagine that the daughter utters “grass”? (ii) Are we meant to imagine that the father hears the utterance of “grass”? (iii) Are we meant to imagine that we hear the utterance of “grass”? (iv) Are we meant to imagine that the daughter utters “for”? (v) Are we meant to imagine that the father hears the utterance of “for”? (vi) Are we meant to imagine that we hear the utterance of “for”?

The best answers I have to these questions are (i) Yes – definitely (ii) Maybe? (iii) Yes – I think, (iv) Maybe – It might be another word (although that seems unlikely) (v) No – I think, and (vi) I have no freaking idea.

I would love to hear what others think about this.

Conversation analysis seems like a very fruitful way of looking at speech balloons and turn-taking in comics, Frank. This post is quite helpful. Though I, too, am given pause by the obscured aspects of the daughter’s speech in Panel 5 of The Superbowl, I am even more intrigued by the difference between the overlaps between father and daughter’s speech in panels 4 and 5. I tend to be most interested in issues of power when I look at transcribed conversations (who interrupts whom? who speaks longer, who asks more questions, who adds tag questions like “right?”, “isn’t it?,” etc., how do the speech patterns displayed echo or refute relative degrees of speaker status, how is silence used….). Therefore, I’m struck by the fact that the daughter’s balloon overlaps her father’s in panel 4 (as it logically should since her question came first in time), but the father’s balloon overlaps the daughter’s in panel 5 despite the fact that her question must have emerged prior to his admonishment. In the case of panel 5, the performative act of the father– hushing his daughter–trumps strict narrative time, and we get to see that his desire to watch the commercials blots out/cancels his previous patience with his daughter’s questions and thus, covers over/blots out her linguistic agency. I’d definitely say this proves your point that speech balloons can be used creatively to make the reader imagine speakers conversing in a natural way, but also to indicate the perlocutionary aspects of these speech acts.

Roy! I knew I needed to acknowledge the spelling of Superbowl, if for no other reason than the comic is a satiric comment on the way that Americans engage with that particular pastime.

As I was writing the post, I was imagining how you might bring Walton to bear on it. Your questions i-vi are great, and it’s fun to think about them. I’ll respond a little more to them below.

Adrielle: thanks for a great comment…I find CA to be an important and useful tool in understanding language in comics. In my own research, I also try to ask questions about social identity and power as they are found in conversation, and I’m glad you mention them. I chose these two comics because there is a kind of parallel here: we might call both of them examples of asymmetrical discourse because one speaker (the doctor, the father) has more social power than the other speaker (patient, daughter). The relationships aren’t the same, of course, but they offer a productive opportunity for comparison.

I think that Roy’s questions ii & v relate very specifically to Adrielle’s questions about power and agency. Perhaps the father hears the daughter’s turn in its entirety but simply chooses to ignore it. In this case, though, the content of the dad’s turn (Quiet sweetie…) suggests that even if he does hear the whole turn, he is actively squashing it. (This is also a weird example of language socialization, when caregivers use linguistic strategies to teach children how to behave.)

I think panel 4 in The Superbowl is a problematic moment of speech balloons and simultaneous talk gone awry, and I am thinking about coming back to that one in a future post.

Hi, Tony. I will add Chaykin’s American Flagg to my list, too. Thanks for the note.

Love this post, Frank! I also want to echo Adrielle’s comments (and your response) about how the overlapping speech balloons visualize the dynamics of power and agency in the conversation really well. What struck me at the end of “Symbiote” is more than just the fact that the two are talking over one another, but that they are no longer even engaged in a genuine conversation. Once the doctor shifts into the jargon of health insurance protocols, he is basically just talking to himself. As a result, the overlapping balloons convey a greater distance between the two speakers, and although the doctor is in the position of authority, his unwillingness to listen makes him look foolish. The same is true for the second strip, where the father’s ignorance about the sport prompts him to leave the conversation by shifting into condescending “parent-speak.” Is there are term/concept in linguistics for when speakers have mentally left a conversation and their speech goes on a kind of autopilot of trite phrases and meaningless responses?

Thanks, Qiana! (I had fun writing it!)

When describing that moment when a speaker goes on ‘autopilot,’ the term that comes to mind immediately is ‘conversation routine.’ When we say things because we’re supposed to say them, we’re frequently using a routine.

Robert Hopper wrote about routines, and one example that always struck me was the telephone conversation. We start out by saying ‘hello’ or some equivalent. But really that isn’t even the first turn. The first thing that happens is that the phone rings, so it’s a signal that we need to enter into a routine to begin the conversation successfully.

Routines are only a small part of our repertoire, though. We use those formulaic utterances to greet people, to say goodbye, to open or close committee meetings, etc. So I wouldn’t say that the dad is using a widely used routine. On the other hand, you termed it “condescending ‘parent-speak,'” and my best guess is that there are formulaic utterances that parents use with their children quite regularly.

I’m afraid that I don’t have a good answer for the other part of your question, when speakers have mentally left a conversation. I think that’s a much harder question!

Comments are closed.

When Did Word Balloons and Thought Balloons Debut in Comics?

In their latest spotlight on notable comic firsts, CSBG delves into the history of speech balloons and thought balloons in comics.

In "When We First Met," we spotlight the various characters, phrases, objects or events that eventually became notable parts of comic lore, like the first time someone said, "Avengers Assemble!" or the first appearance of Batman's giant penny or the first appearance of Alfred Pennyworth or the first time Spider-Man's face was shown half-Spidey/half-Peter. Stuff like that.

Reader Steven H. wanted to know about specifically the history of the thought balloon, when that balloon was designed as a sort of cloud rather than a word balloon, but you know what? While I'm answering that, I should really just detail the history of the speech balloon in comics period.

What we now think of as word balloons probably owe their origins to 15th Century paintings and drawings that had I guess what you would call a "speech band," these sort of tapestries with words on them.